The history of the

Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

is intertwined with the history of the broader

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

and the surrounding regions, comprising the areas of

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

and

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

; and the modern nation consisting of 26 natural

atolls

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon partially or completely. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical oceans and seas where corals can grow ...

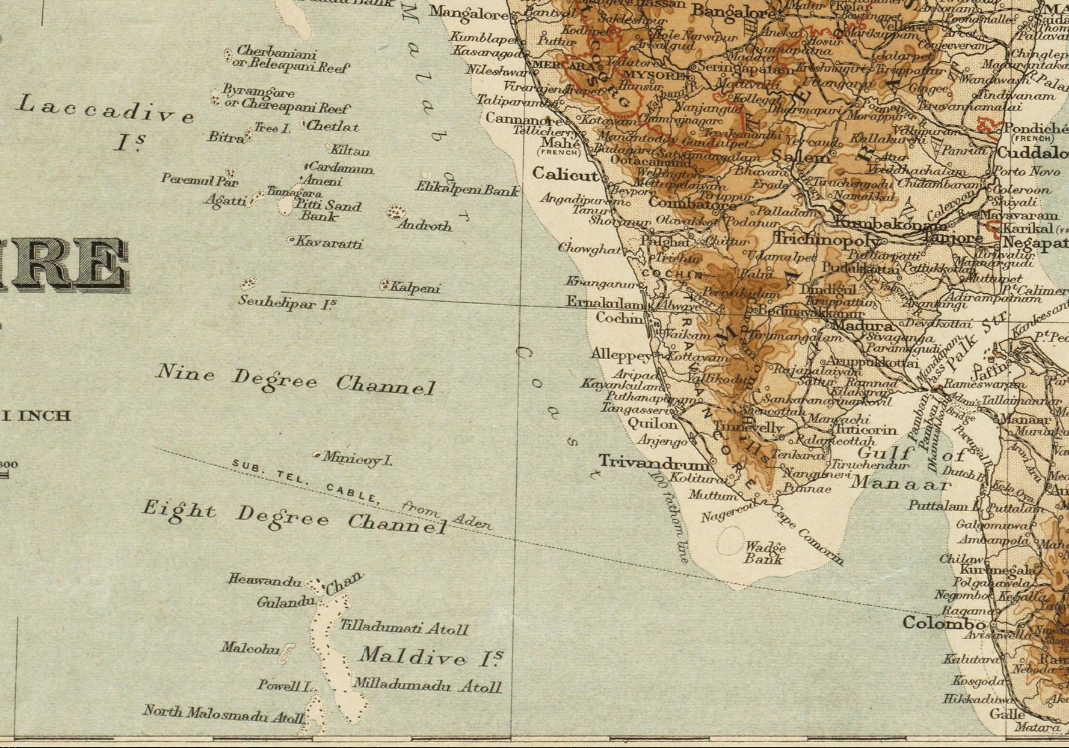

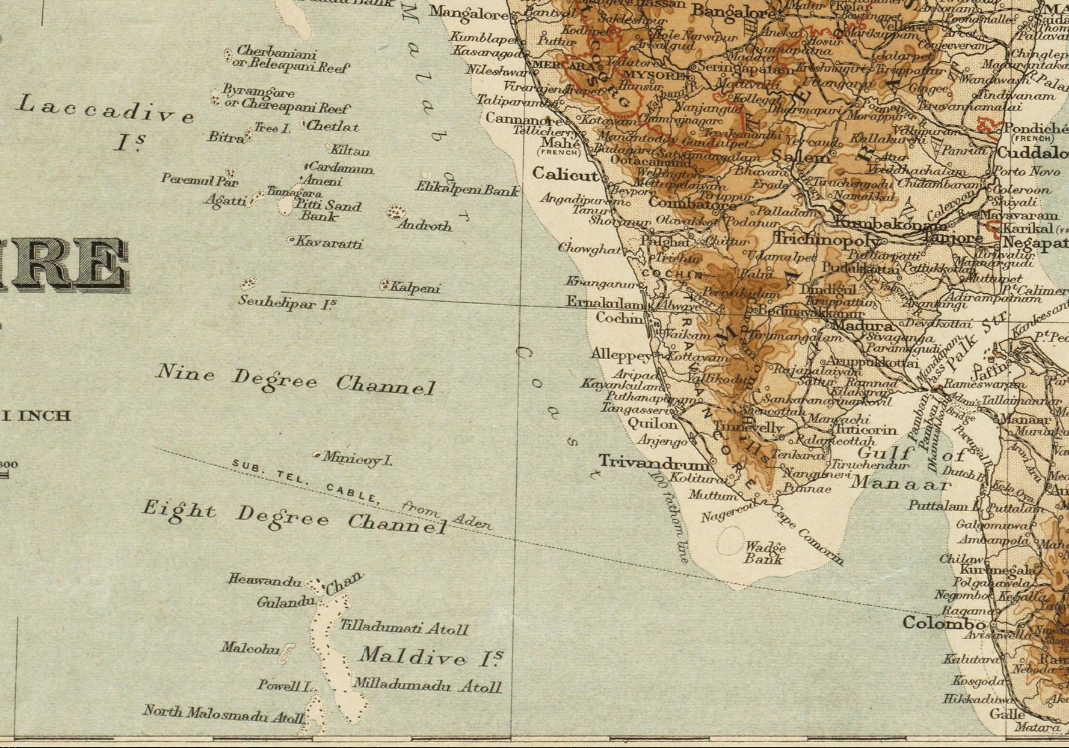

, comprising 1194 islands. Historically, the Maldives had a strategic importance because of its location on the major marine routes of the Indian Ocean.

[.] The Maldives' nearest neighbours are the

British Indian Ocean Territory

The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) is an Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom situated in the Indian Ocean, halfway between Tanzania and Indonesia. The territory comprises the seven atolls of the Chagos Archipelago with over 1,000 ...

,

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. The

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, Sri Lanka and some Indian kingdoms have had cultural and economic ties with the Maldives for centuries.

In addition to these countries, Maldivians also traded with

Aceh

Aceh ( ), officially the Aceh Province ( ace, Nanggroë Acèh; id, Provinsi Aceh) is the westernmost province of Indonesia. It is located on the northernmost of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capital and largest city. Granted a s ...

and many other kingdoms in, what is today,

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

and

Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

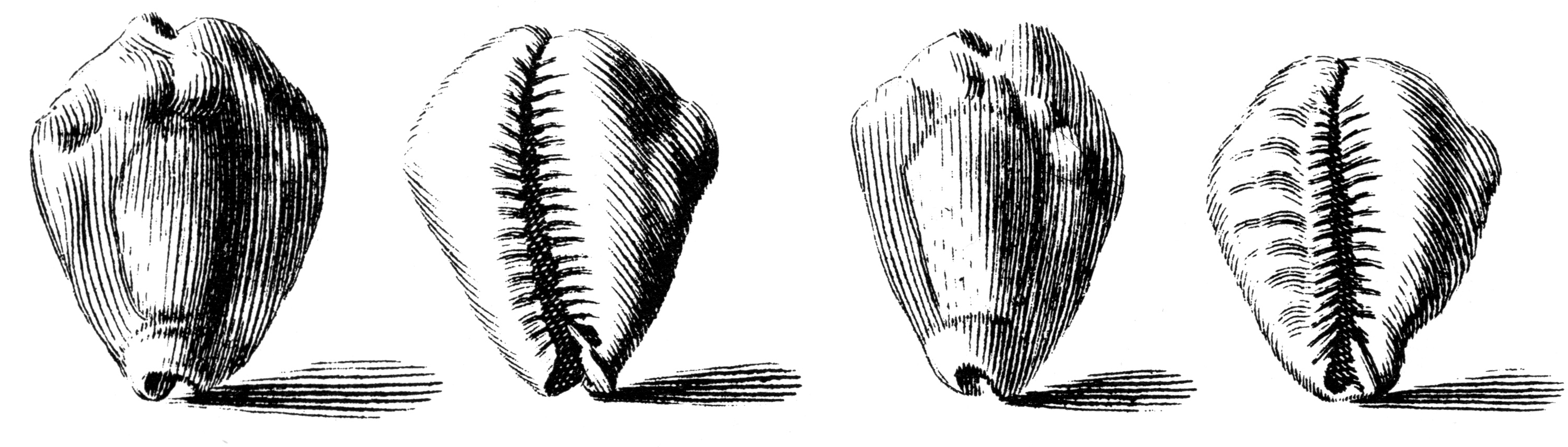

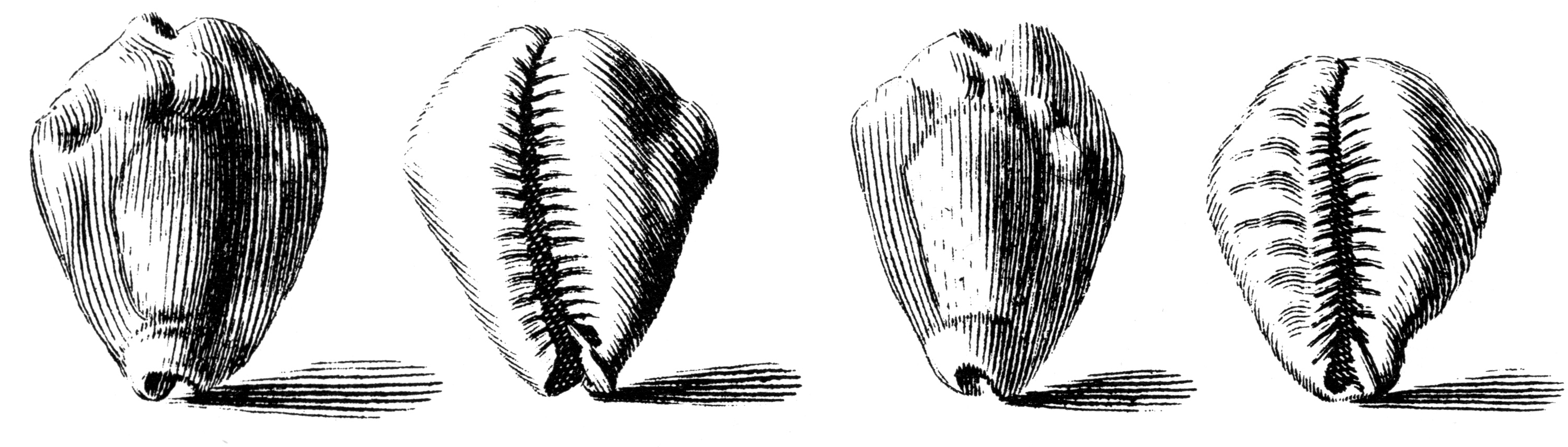

. The Maldives provided the main source of

cowrie shells

Cowrie or cowry () is the common name for a group of small to large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Cypraeidae, the cowries.

The term ''porcelain'' derives from the old Italian term for the cowrie shell (''porcellana'') du ...

, then used as a currency throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast.

Most probably Maldives were influenced by

Kalinga Kalinga may refer to:

Geography, linguistics and/or ethnology

* Kalinga (historical region), a historical region of India

** Kalinga (Mahabharata), an apocryphal kingdom mentioned in classical Indian literature

** Kalinga script, an ancient writ ...

s of ancient India who were earliest sea traders to Sri Lanka and the Maldives from India and were responsible for the spread of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

. Stashes of Chinese crockery found buried in various locations in the Maldives also show that there was direct or indirect trade contact between

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and the Maldives. In 1411 and 1430, the Chinese admiral

Zheng He

Zheng He (; 1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty. He was originally born as Ma He in a Muslim family and later adopted the surname Zheng conferred ...

鄭和 visited the Maldives. The Chinese also became the first country to establish a diplomatic office in the Maldives, when the Chinese nationalist government based in Taipei opened an embassy in Malé in 1966. This office has since been replaced by the embassy of the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

After the 16th century, when

colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

powers took over much of the trade in the Indian Ocean, first the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and the French occasionally meddled in local politics. However, this interference ended when the Maldives became a British Protectorate in the 19th century and the Maldivian monarchs were granted a good measure of self-governance.

The Maldives gained total independence from the British on 26 July 1965. However, the British continued to maintain an air base on the island of

Gan

The word Gan or the initials GAN may refer to:

Places

*Gan, a component of Hebrew placenames literally meaning "garden"

China

* Gan River (Jiangxi)

* Gan River (Inner Mongolia),

* Gan County, in Jiangxi province

* Gansu, abbreviated ''Gā ...

in the southernmost atoll until 1976.

The British departure in 1976 at the height of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

almost immediately triggered foreign speculation about the future of the air base.

The Soviet Union requested the use of the base, but the Maldives refused.

The greatest challenge facing the republic in the early 1990s was the need for rapid economic development and modernisation, given the country's limited resource base in fishing and tourism.

Concern was also evident over a projected long-term

sea level rise

Globally, sea levels are rising due to human-caused climate change. Between 1901 and 2018, the globally averaged sea level rose by , or 1–2 mm per year on average.IPCC, 2019Summary for Policymakers InIPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cry ...

, which would prove disastrous to the low-lying coral islands.

Early Age

Much of the history of the Maldives is unknown, however based on tales and actual data, we can deduce that the islands have been inhabited for over 2500 years, according to an old folklore from the Maldives' southern atoll. Allama Ahmed Shihabuddine (Allama Shihab al-Din) of Meedhoo on Addu Atoll wrote down this account in Arabic during Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar I's rule in the 17th century. Kitab Fi al-Athari Midu al-Qadimiyyah was the title of Allama Shihabuddine's book ("On the Ancient Ruins of Meedhoo"). The account is strikingly consistent with known South Asian history, including referencing Emperor Asoka, the legendary Indian emperor.

It also backs up parts of the facts found in old Maldivian records and the loamaafaanu copperplates. Legends from the past, facts written on old copperplates, ancient writings engraved on coral items, and repeated in the language, traditions, and ethnicity of the people tell the tale of the Maldives' legacy.

In comparison to the southern islands, which are up to 800 km away, the northern islands may have had a different migratory and colonization history.

The first settlers to the southern Maldives

A delegation from the Divi people sent gifts to the Roman Emperor Julian, according to a 4th-century note published by Ammianus Marcellinus in 362 AD. (1937, Rolfe). Divi is remarkably similar to Dheyvi, and it is possible that they are the same person. The Redi and the Kunibee, both from India's Mahrast area, were among the later settlers. The Aryas (Aryans) arrived in the Maldives about the 6th-5th century BC, roughly three centuries before Emperor Asoka built his state in India. According to folklore, they were not native to India and had arrived from another country. Hinduism was also brought to the Maldives at this period (Shihabuddine c. 1650–1687).

Dheeva Maari

The Dheyvis found

Suvadinmathi (Huvadhu Atoll) after their first settlement in Isdhuva in Isduvammathi (

Haddhunmathi

Haddhunmathi or Laamu Atoll (Dhivehi: ހައްދުންމަތި އަތޮޅު) is an administrative division of the Maldives. The administrative capital is Fonadhoo Island. It corresponds to the natural atoll of the same name.

It is mostly rimmed ...

) according to Shihabuddine.

These people gave the term "duva" to each island where they first lived and discovered.

They established the Dheeva Maari

= The first known monarch of the Dheevis

=

The kingdom of Adeetta Vansa was formed in Dheeva Maari by Sri Soorudasaruna Adeettiya which was his formal name. This was the first known monarch of the Dheevis of Dheeva Maari. He founded the kingdom of Adeetta Vansa just before the kingdom of "

Malik Aashooq" was created.

= Dheeva Mahal

=

A group of individuals from Bairat came to Dheeva Maari to preach Buddha's beliefs and works. Dheeva Mahal was the name given to Dheeva Maari during the time.

The first settlers to the northern Maldives

According to mythology, the northern atolls of Maldives were populated by other tribes from southern India with deeper skin colors. The islands they populated were given names like Nolhivaram, Kuruhinnavaram, and Giravaram, according to legend (Shihabuddine c. 1650–1687). These islands are now known as Nolhivaramu, Hinnavaru, and Giravaru. It's probable that the names have evolved over many centuries to their current form.

Comparative studies of Maldivian oral, linguistic and cultural traditions and customs indicate that one of the earliest settlers to the northern Maldives were descendants of fishermen from the

southwest coasts of present

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and the northwestern shores of

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. One such community are the

Giraavaru people

The Giraavaru people are indigenous people of the Giravaaru islands that is part of Maldives. They are considered to be of Dravidian origin, and the earliest island community of the Maldives, predating Buddhism and the arrival of a Northern ki ...

. They are mentioned in ancient legends and local folklore about the establishment of the capital and kingly rule in

Malé

Malé (, ; dv, މާލެ) is the capital and most populous city of the Maldives. With a population of 252,768 and an area of , it is also one of the most densely populated cities in the world. The city is geographically located at the southern ...

.

Some argue (from the presence of Jat, Gujjar Titles and Gotra names) that

Sindhis

Sindhis ( sd, سنڌي Perso-Arabic: सिन्धी Devanagari; ) are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group who speak the Sindhi language and are native to the province of Sindh in Pakistan. After the partition of British Indian empire in 1947, man ...

also accounted for an early layer of migration. Seafaring from

Debal

Debal (Urdu, Arabic, sd, ) was an ancient port located near modern Karachi, Pakistan. It is adjacent to the nearby Manora Island and was administered by Mansura, and later Thatta.

Etymology

In Arabic history books, most notably in the early ...

began during the

Indus valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

. The

Jataka

The Jātakas (meaning "Birth Story", "related to a birth") are a voluminous body of literature native to India which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. According to Peter Skilling, this genre is ...

s and

Puranas

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

show abundant evidence of this maritime trade; the use of similar traditional boat building techniques in Northwestern South Asia and the Maldives, and the presence of silver punch mark coins from both regions, gives additional weight to this. There are minor signs of Southeast Asian settlers, probably some adrift from the main group of

Austronesian reed boat migrants that settled

Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

.

Kingdom of Adeetta Vansa

The Kingdom of Adeetta Vansa (Solar Dynasty) formed in Dheeva maari ruled until the establishment of the Kingdom of Soma Vansa (Lunar Dynasty). Soma Vansa was born in Kalinja, and Adeetta Vansa was born in Kalinja as well. This kingdom was founded by the son of a Soma Vansa monarch who ruled in Kalinja at the time. Dheeva Mahal turned to Islam over a century and a half later. Sri Balaadeettiya was the first king of Soma Vansa. Queen Damahaar, his wife, was the final queen of Adeetta Vansa. So, while the dynasty's name was altered to Soma Vansa, the monarchs were still related to both Soma Vansa and Adeetta Vansa.

Kingdom of Soma Vansa

At the start of the Soma Vansa dynasty, the Indian ruler Raja Dada invaded Dheeva Mahal's northern two atolls, Malikatholhu and Thiladunmathi, and took control of them. Sri Loakaabarana, (his son) Sri Maha Sandura, and his brother Sri Bovana Aananda were the most recent five monarchs of Soma Vansa before to the advent of Islam. After his brother, Sri Maha Sandura, passed away, he ascended to the crown.

Mahapansa

Sri Maha Sandura's daughter, Kamanhaar (sometimes spelled Kamanaar), and Rehendihaar were exiled to the island of "Is Midu." She took Maapanansa, a book that contained the history of Adeetta Vansa's kings. In his work, Al Muhaddith Hasan claims to have read the entire Maapanansa, which was written in Copper. He also claims to have buried all of Maapanansa's parts. Sri Mahaabarana Adeettiya, Sri Bovana Aananda's son, ascended to the throne after him. The Indians who controlled Malikatholhu and Thiladunmathi, the two most northern atolls, were defeated by this King. The Indians belonged to the same tribe as Raja Dada, who was the first to conquer these two atolls. He was then given the title of monarch of 14 atolls and 2,000 islands. Malikaddu dhemedhu

etween Minicoy and Adduwas his "Dheeva Mahal."

Ancient names of atolls of Maldives according to Mahapansa

# Malikatholhu

# Thiladunmathi

# Miladunmaduva

# Maalhosmaduva

# Faadu Bur

# Mahal Atholhu

# Ari adhe Atholhu

# Felide Atholhu

# Mulakatholhu

# Nilande Atholhu

# Kolhumaduva

# Isaddunmathi

# Suvadinmathi

# Addu Fuvah Mulakatholhu

Archaeological remains of the first settlers

These first Maldivians did not leave any archaeological remains. Their buildings were probably built of wood, palm fronds and other perishable materials, which would have quickly decayed in the salt and wind of the tropical climate. Moreover, chiefs or headmen did not reside in elaborate stone palaces, nor did their religion require the construction of large temples or compounds.

Earliest written history

The earliest written history of the Maldives is marked by the arrival of

Sinhalese people

Sinhalese people ( si, සිංහල ජනතාව, Sinhala Janathāva) are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group native to the island of Sri Lanka. They were historically known as Hela people ( si, හෙළ). They constitute about 75% of t ...

, who were descended from the exiled

Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

Prince

Vijaya

Vijaya may refer to:

Places

* Vijaya (Champa), a city-state and former capital of the historic Champa in what is now Vietnam

* Vijayawada, a city in Andhra Pradesh, India

People

* Prince Vijaya of Sri Lanka (fl. 543–505 BC), earliest recorde ...

from the ancient city known as

Sinhapura

Sinhapura ("Lion City" for Sanskrit; IAST: Siṃhapura) was the capital of the legendary Indian king Sinhabahu. It has been mentioned in the Buddhist legends about Prince Vijaya. The name is also transliterated as ''Sihapura'' or ''Singhapura' ...

in North East India. He and his party of several hundred landed in Sri Lanka, and some in the Maldives circa 543 to 483 BC. According to the ''

Mahavansa'', one of the ships that sailed with Prince Vijaya, who went to Sri Lanka around 500 BC, went adrift and arrived at an island called ''Mahiladvipika'', which is being identified with the Maldives. It is also said that at that time, the people from Mahiladvipika used to travel to Sri Lanka. Their settlement in Sri Lanka and the Maldives marks a significant change in demographics and the development of the

Indo-Aryan language

The Indo-Aryan languages (or sometimes Indic languages) are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family. As of the early 21st century, they have more than 800 million speakers, primarily concentrated in India, Pa ...

Dhivehi

Dhivehi, also spelled Divehi, may refer to:

*Dhivehi people, an ethnic group native to the historic region of the Maldive Islands.

*Dhivehi language, an Indo-Aryan language predominantly spoken by about 350,000 people in the Republic of Maldives

...

, which is most similar in grammar, phonology, and structure to

Sinhala, and especially to the more ancient

Elu Prakrit, which has less

Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

.

Alternatively, it is believed that ''Vijaya'' and his clan came from western India – a claim supported by linguistic and cultural features, and specific descriptions in the epics themselves, e.g. that ''Vijaya'' visited ''Bharukaccha'' (

Bharuch

Bharuch (), formerly known as Broach, is a city at the mouth of the river Narmada in Gujarat in western India. Bharuch is the administrative headquarters of Bharuch District.

The city of Bharuch and surroundings have been settled since tim ...

in Gujarat) in his ship on the voyage down south.

Philostorgius

Philostorgius ( grc-gre, Φιλοστόργιος; 368 – c. 439 AD) was an Anomoean Church historian of the 4th and 5th centuries.

Very little information about his life is available. He was born in Borissus, Cappadocia to Eulampia and Cart ...

, a Greek historian of Late Antiquity, wrote of a hostage among the Romans, from the island called ''Diva'', which is presumed to be the Maldives, who was baptised Theophilus.

Theophilus

Theophilus is a male given name with a range of alternative spellings. Its origin is the Greek word Θεόφιλος from θεός (God) and φιλία (love or affection) can be translated as "Love of God" or "Friend of God", i.e., it is a theoph ...

was sent in the 350s to convert the

Himyarites

The Himyarite Kingdom ( ar, مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, he, ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar ( ar, حِمْيَر, ''Ḥimyar'', / 𐩹𐩧𐩺𐩵𐩬) (floruit, fl. 110 BCE–520s Common Era, CE), historically referre ...

to Christianity, and went to his homeland from

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

; he returned to Arabia, visited

Axum, and settled in

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

.

Caste system in Maldives

Maldivian society serves as an example of a social structure that has lately shed a lot of stratification related characteristics while still perhaps holding onto certain remnants of the former caste society.

Buddhist period

Despite being just mentioned briefly in most history books, the 1,400-year-long Buddhist period has a foundational importance in the history of the Maldives. It was during this period that the culture of the Maldives as we now know it both developed and flourished. The Maldivian

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

, the first Maldive

scripts

Script may refer to:

Writing systems

* Script, a distinctive writing system, based on a repertoire of specific elements or symbols, or that repertoire

* Script (styles of handwriting)

** Script typeface, a typeface with characteristics of handw ...

, the architecture, the ruling institutions, the customs and manners of the Maldivians originated at the time when the Maldives were a Buddhist kingdom.

Before embracing Buddhism as their way of life, Maldivians had practised an ancient form of

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

,

ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

istic traditions known as ''Śrauta'', in the form of venerating the ''

Surya

Surya (; sa, सूर्य, ) is the sun as well as the solar deity in Hinduism. He is traditionally one of the major five deities in the Smarta tradition, all of whom are considered as equivalent deities in the Panchayatana puja and a m ...

'' (the ancient ruling caste were of ''Aadheetta'' or ''Suryavanshi'' origins).

Buddhism probably spread to the Maldives in the 3rd century BC, at the time of

Aśoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

. Nearly all archaeological remains in the Maldives are from Buddhist

stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

s and monasteries, and all artifacts found to date display characteristic Buddhist iconography.

Buddhist (and Hindu) temples were

Mandala

A mandala ( sa, मण्डल, maṇḍala, circle, ) is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for e ...

shaped, they are oriented according to the four cardinal points, the main gate being towards the east. The ancient Buddhist stupas are called "havitta", "hatteli" or "ustubu" by the Maldivians according to the different atolls. These stupas and other archaeological remains, like foundations of Buddhist buildings

Vihara, compound walls and stone baths, are found on many islands of the Maldives. They usually lie buried under mounds of sand and covered by vegetation. Local historian Hassan Ahmed Maniku counted as many as 59 islands with Buddhist archaeological sites in a provisional list he published in 1990. The largest monuments of the Buddhist era are in the islands fringing the eastern side of

Haddhunmathi Atoll.

In the early 11th century, the

Minicoy

Minicoy, locally known as Maliku (), is an island in Lakshadweep, India. Along with Viringili, it is on ''Maliku atoll'', the southernmost atoll of Lakshadweep archipelago. Administratively, it is a census town in the Indian union territory ...

and Thiladhunmathi, and possibly other northern Atolls, were conquered by the

medieval Chola

Medieval Cholas rose to prominence during the middle of the 9th century CE and established one of the greatest empires of South India. They successfully united South India under their rule and through their naval strength extended their influen ...

Tamil emperor

Raja Raja Chola I

Rajaraja I (947 CE – 1014 CE), born Arunmozhi Varman or Arulmozhi Varman and often described as Raja Raja the Great or Raja Raja Chozhan was a Chola emperor who reigned from 985 CE to 1014 CE. He was the most powerful Tamil king in South ...

, thus becoming a part of the

Chola Empire

The Chola dynasty was a Tamil thalassocratic empire of southern India and one of the longest-ruling dynasties in the history of the world. The earliest datable references to the Chola are from inscriptions dated to the 3rd century BC ...

.

Unification of the archipelago is traditionally attributed to King

Koimala.

According to a legend from

Maldivian folklore, in the early 12th century AD, a medieval prince named

Koimala, a nobleman of the Lion Race from Sri Lanka, sailed to Rasgetheemu island (literally "Town of the Royal House", or figuratively "King's Town") in the North Maalhosmadulu Atoll, and from there to Malé, and established a kingdom, named

Dheeva Mari Kingdom. By then, the ''Aadeetta'' (Sun) Dynasty (the

Suryavanshi ruling cast) had for some time ceased to rule in Malé, possibly because of invasions by the Cholas of Southern India in the 10th century. Koimala Kalou (Lord Koimala), who reigned as King Maanaabarana, was a king of the ''Homa'' (Lunar) Dynasty (the

Chandravanshi

The Lunar dynasty ( IAST: Candravaṃśa) is a legendary principal house of the Kshatriyas varna, or warrior–ruling caste mentioned in the ancient Indian texts. This legendary dynasty was said to be descended from moon-related deities ('' ...

ruling cast), which some historians call the

House of Theemuge.

The ''Homa'' (Lunar) dynasty sovereigns intermarried with the ''Aaditta'' (Sun) Dynasty. This is why the formal titles of Maldive kings until 1968 contained references to "''kula sudha ira''", which means "descended from the Moon and the Sun". No official record exists of the Aadeetta dynasty's reign. Since Koimala's reign, the Maldive throne was also known as the ''Singaasana'' (Lion Throne).

Before then, and in some situations since, it was also known as the ''Saridhaaleys'' (Ivory Throne).

Some historians credit Koimala with freeing the Maldives from

Chola

The Chola dynasty was a Tamils, Tamil thalassocratic Tamil Dynasties, empire of southern India and one of the longest-ruling dynasties in the history of the world. The earliest datable references to the Chola are from inscriptions dated ...

rule.

Western interest in the archaeological remains of early cultures on the Maldives began with the work of

H.C.P. Bell

Harry Charles Purvis Bell, CCS (21 September 1851 – 6 September 1937), more often known as HCP Bell, was a British civil servant and the first Commissioner of Archaeology in Ceylon.

Early life

Born in British India in 1851, he was sent to En ...

, a

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

commissioner of the

Ceylon Civil Service

The Ceylon Civil Service, popularly known by its acronym CCS, was the premier civil service of the Government of Ceylon under British colonial rule and in the immediate post-independence period. Established in 1833, it functioned as part of the ...

.

Bell was first ordered to the islands in late 1879 and returned several times to the Maldives to investigate ancient ruins.

He studied the ancient mounds, called ''havitta'' or ''ustubu'' (these names are derived from

chaitiya and

stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circumamb ...

) ( dv, ހަވިއްތަ) by the Maldivians, which are found on many of the atolls.

Early scholars like H.C.P. Bell, who resided in Sri Lanka most of his life, claim that Buddhism came to the Maldives from

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and that the ancient Maldivians had followed

Theravada Buddhism

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

. Since then, new archaeological discoveries point to

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

and

Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

Buddhist influences, which are likely to have come to the islands straight from the Subcontinent. An urn discovered in

Maalhos (Ari Atoll) in the 1980s has a

Vishvavajra inscribed with

Protobengali script. This text was in the same script used in the ancient Buddhist centres of learning in

Nalanda

Nalanda (, ) was a renowned ''mahavihara'' (Buddhist monastic university) in ancient Magadha (modern-day Bihar), India.[Vikramashila

Vikramashila (Sanskrit: विक्रमशिला, IAST: , Bengali:- বিক্রমশিলা, Romanisation:- Bikrômôśilā ) was one of the three most important Buddhist monasteries in India during the Pala Empire, along with N ...]

. There is also a small Porites stupa in the Museum where the directional

Dhyani Buddhas (Jinas) are etched in its four cardinal points as in the

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

tradition. Some coral blocks with fearsome heads of guardians are also displaying

Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

Iconography. Buddhist remains have been also found in

Minicoy Island

Minicoy, locally known as Maliku (), is an island in Lakshadweep, India. Along with Viringili, it is on ''Maliku atoll'', the southernmost atoll of Lakshadweep archipelago. Administratively, it is a census town in the Indian union territory o ...

, then part of the Maldive Kingdom, by the

Archaeological Survey of India

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexande ...

(ASI), in the latter half of the 20th century. Among these remains a Buddha head and stone foundations of a Vihara deserve special mention.

In the mid-1980s, the Maldivian government allowed Norwegian explorer

Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl KStJ (; 6 October 1914 – 18 April 2002) was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in zoology, botany and geography.

Heyerdahl is notable for his ''Kon-Tiki'' expedition in 1947, in which he sailed 8,000&nb ...

to excavate ancient sites.

[.] Heyerdahl studied the ancient mounds, called havitta by the Maldivians, found on many of the atolls.

Some of his archaeological discoveries of stone figures and carvings from pre-Islamic civilizations are today exhibited in a side room of the small National Museum on Male.

Heyerdahl's research indicates that as early as 2,000 B.C. Maldives lay on the maritime trading routes of early Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Indus Valley civilizations.

Islamic period

Introduction of Islam

The importance of the Arabs as traders in the Indian Ocean by the 12th century may partly explain why the last Buddhist king of Maldives

Dhovemi converted to

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

in the year 1153

(or 1193, as certain copper plate grants give a later date). The king thereupon adopted the Muslim title and name of Sultan Muhammad al Adil, initiating a series of six dynasties consisting of eighty-four sultans and sultanas that lasted until 1932 when the sultanate became elective.

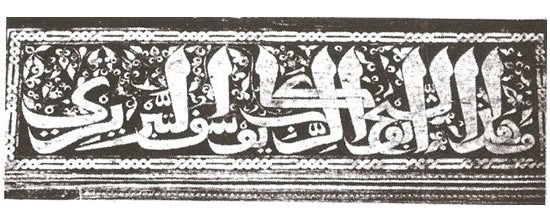

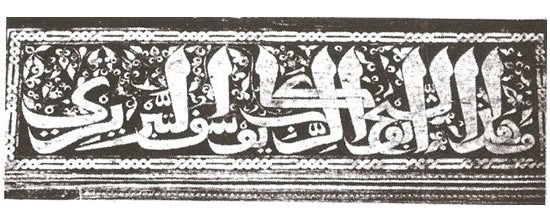

The formal title of the Sultan up to 1965 was, ''Sultan of Land and Sea, Lord of the twelve-thousand islands and Sultan of the Maldives'' which came with the style ''

Highness

Highness (abbreviation HH, oral address Your Highness) is a formal style used to address (in second person) or refer to (in third person) certain members of a reigning or formerly reigning dynasty. It is typically used with a possessive adjecti ...

''.

The person traditionally deemed responsible for this conversion was a

Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Muslim visitor named Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.

His venerated tomb now stands on the grounds of Medhu Ziyaaraiy across the street from the

Hukuru Mosque in the capital

Malé

Malé (, ; dv, މާލެ) is the capital and most populous city of the Maldives. With a population of 252,768 and an area of , it is also one of the most densely populated cities in the world. The city is geographically located at the southern ...

. Built in 1656, this is the oldest mosque in Malé.

Following the Islamic concept that before Islam there was the time of

Jahiliya

The Age of Ignorance ( ar, / , "ignorance") is an Islamic concept referring to the period of time and state of affairs in Arabia before the advent of Islam in 610 CE. It is often translated as the "Age of Ignorance". The term ''jahiliyyah'' ...

(ignorance), in the history books used by Maldivians the

introduction of Islam at the end of the 12th century is considered the cornerstone of the country's history.

Compared to the other areas of South Asia, the conversion of the Maldives to Islam happened relatively late. Arab Traders had converted populations in the

Malabar Coast

The Malabar Coast is the southwestern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Geographically, it comprises the wettest regions of southern India, as the Western Ghats intercept the moisture-laden monsoon rains, especially on their westward-facing m ...

since the 7th century, and the Arab conqueror

Muhammad Bin Qāsim had converted large swathes of

Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

to Islam at about the same time. The Maldives remained a Buddhist kingdom for another five hundred years (perhaps the south-westernmost Buddhist country) until the conversion to Islam.

The document known as Dhanbidhū

Lōmāfānu gives information about the suppression of Buddhism in the southern

Haddhunmathi Atoll, which had been a major center of that religion. Monks were taken to Male and beheaded, The Satihirutalu (the chattravali or chattrayashti crowning a stupa) were broken to disfigure the numerous stupasm and the statues of

Vairocana

Vairocana (also Mahāvairocana, sa, वैरोचन) is a cosmic buddha from Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Vairocana is often interpreted, in texts like the ''Avatamsaka Sutra'', as the dharmakāya of the historical Gautama Buddha. In East ...

, the transcendent

Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

of the middle world region, were destroyed.

Arab interest in Maldives also was reflected in the residence there in the 1340s of

Ibn Battutah

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim wor ...

. The well-known North African traveler wrote how a Moroccan, one ''Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari'', was believed to have been responsible for spreading Islam in the islands, reportedly convincing the local king after having subdued

Ranna Maari, a demon coming from the sea. Even though this report has been contested in later sources, it does explain some crucial aspects of Maldivian culture. For instance, historically Arabic has been the prime language of administration there, instead of the Persian and Urdu languages used in the nearby Muslim states. Another link to North Africa was the

Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

school of jurisprudence, used throughout most of North Africa, which was the official one in the Maldives until the 17th century.

The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveller of the Fourteenth Century

'' Muslim Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari, is traditionally credited for this conversion. According to the story told to

Ibn Battutah

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim wor ...

, a mosque was built with the inscription: 'The Sultan Ahmad Shanurazah accepted Islam at the hand of Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.'

Some scholars have suggested the possibility of Ibn Battuta misreading Maldive texts, and having a bias towards the North African, Maghrebi narrative of this Shaykh, instead of the East African origins account that was known as well at the time. Even when Ibn Battuta visited the islands, the governor of the island at that time was

Abd Aziz Al Mogadishawi, a

Somali.

Scholars have posited another scenario where Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari might have been a native of

Barbera

Barbera is a red Italian wine grape variety that, as of 2000, was the third most-planted red grape variety in Italy (after Sangiovese and Montepulciano). It produces good yields and is known for deep color, full body, low tannins and high levels ...

, a significant trading port on the northwestern coast of

Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

. ''Barbara'' or ''Barbaroi'' (Berbers), as the ancestors of the

Somalis

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The Lowland East Cushitic Somali language is the shared ...

were referred to by medieval

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and ancient

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

geographers, respectively.

[F.R.C. Bagley et al., ''The Last Great Muslim Empires'' (Brill: 1997), p. 174.][Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, ''Culture and Customs of Somalia'', (Greenwood Press: 2001), p. 13.] This is also seen when Ibn Batuta visited

Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port ...

, he mentions that the Sultan at that time, "Abu Bakr ibn Shaikh Omar", was a Berber.

Ibn Batuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim wo ...

states the Maldivian king was converted by Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari (Meaning Abdul Barakat the Berber).

Another interpretation, held by the more reliable local historical chronicles, ''Raadavalhi'' and ''Taarikh'',

is that Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari was Abdul Barakat Yusuf Shams ud-Dīn

at-Tabrīzī, also locally known as Tabrīzugefānu. In the Arabic script the words al-Barbari and al-Tabrizi are very much alike, owing to the fact that at the time, Arabic had several consonants that looked identical and could only be differentiated by overall context (this has since changed by addition of dots above or below letters to clarify pronunciation – For example, the letter "B" in modern Arabic has a dot below, whereas the letter "T" looks identical except there are two dots above it). "ٮوسڡ الٮٮرٮرى" could be read as "Yusuf at-Tabrizi" or "Yusuf al-Barbari".

Cowrie shells and coir trade

Inhabitants of the Middle East became interested in Maldives due to its strategic location. Middle Eastern seafarers had just begun to take over the Indian Ocean trade routes in the 10th century and found Maldives to be an important link in those routes.

The Maldives was the first landfall for traders from

Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

, sailing to

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

or Southeast Asia.

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

was one of the principal trading partners of the Maldives. Trade involved mainly cowrie shells and coir fiber.

The Maldives had and abundant supply of

cowrie shells

Cowrie or cowry () is the common name for a group of small to large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Cypraeidae, the cowries.

The term ''porcelain'' derives from the old Italian term for the cowrie shell (''porcellana'') du ...

, a form of currency that was widely used throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast since ancient times.

Shell currency

Shell money is a medium of trade, exchange similar to coin money and other forms of commodity money, and was once commonly used in many parts of the world. Shell money usually consisted of whole or partial sea shells, often worked into beads or o ...

imported from the Maldives was used as legal tender in the

Bengal Sultanate

The Sultanate of Bengal ( Middle Bengali: শাহী বাঙ্গালা ''Shahī Baṅgala'', Classical Persian: ''Saltanat-e-Bangālah'') was an empire based in Bengal for much of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. It was the dominan ...

and

Mughal Bengal

The Bengal Subah ( bn, সুবাহ বাংলা; fa, ), also referred to as Mughal Bengal ( bn, মোগল বাংলা), was the largest subdivision of the Mughal Empire (and later an independent state under the Nawabs of Beng ...

, alongside gold and silver. The Maldives received rice in exchange for cowry shells. The Bengal-Maldives cowry shell trade was the largest shell currency trade network in history. In the Maldives, ships could take on fresh water, fruit and the delicious, basket-smoked red flesh of the black ''

bonito

Bonitos are a tribe of medium-sized, ray-finned predatory fish in the family Scombridae – a family it shares with the mackerel, tuna, and Spanish mackerel tribes, and also the butterfly kingfish. Also called the tribe Sardini, it consists of ...

'', a delicacy exported to

Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, China and

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

. The people of the archipelago were described as gentle, civilised and hospitable. They produced

brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

utensils as well as fine cotton textiles, exported in the form of sarongs and turban lengths. These local industries must have depended on imported raw materials.

The other essential product of the Maldives was ''

coir

Coir (), also called coconut fibre, is a natural fibre extracted from the outer husk of coconut and used in products such as floor mats, doormats, brushes, and mattresses. Coir is the fibrous material found between the hard, internal shell ...

'', the fibre of the dried

coconut

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family ( Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the ...

husk

Husk (or hull) in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. In the United States, the term husk often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize (corn) as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protective ...

. Cured in pits, beaten, spun and then twisted into

cordage and

rope

A rope is a group of yarns, plies, fibres, or strands that are twisted or braided together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have tensile strength and so can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger than similarly ...

s, coir's salient quality is its resistance to saltwater. It stitched together and rigged the

dhow

Dhow ( ar, داو, translit=dāwa; mr, script=Latn, dāw) is the generic name of a number of traditional sailing vessels with one or more masts with settee or sometimes lateen sails, used in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean region. Typically spor ...

s that plied the Indian Ocean. Maldivian coir was exported to Sindh, China,

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, and the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

.

"It is stronger than

hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

", wrote

Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

, "and is used to sew together the planks of Sindhi and Yemeni dhows, for this sea abounds in reefs, and if the planks were fastened with iron nails, they would break into pieces when the vessel hit a rock. The coir gives the boat greater elasticity, so that it doesn't break up."

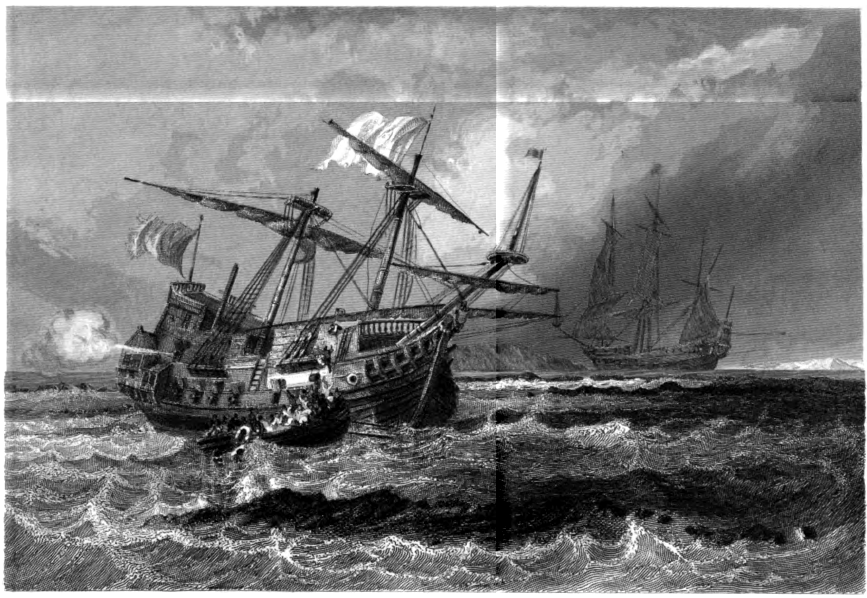

Colonial Period

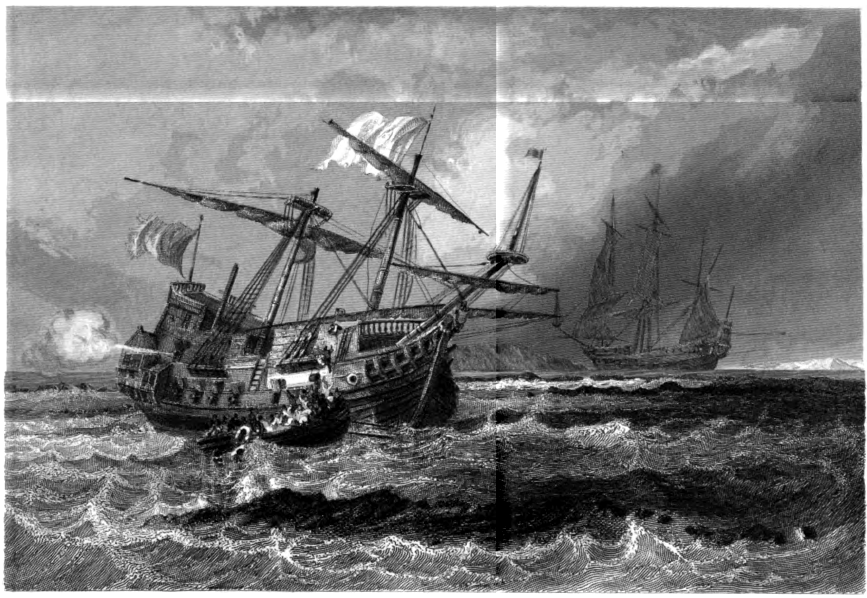

Portuguese and Dutch hegemony

In 1558 the Portuguese established themselves in the Maldives, which they administered from their main colony in

Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

.

[.] They tried to impose Christianity on the locals. Fifteen years later, a local leader named

Muhammad Thakurufaanu al-A'uẓam organized a popular revolt and drove the Portuguese out of Maldives.

This event is now commemorated as National Day, and

a small museum and memorial center honor the hero on his home island of Utheemu on North Thiladhummathi Atoll.

In the mid-17th century, the Dutch, who had replaced the Portuguese as the dominant power in

Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, established hegemony over Maldivian affairs without involving themselves directly in local matters, which were governed according to centuries-old Islamic customs.

Frederik de Wit

Frederik de Wit (born Frederik Hendriksz; – July 1706) was a Dutch Cartography, cartographer and artist.

Early years

Frederik de Wit was born Frederik Hendriksz. He was born to a Protestantism, Protestant family in about 1629, i ...

File:18th-century Maldives map by Pierre Mortier.jpg, 18th-century map by Pierre Mortier of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

depicting with detail the islands of the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

.

File:AriAtoll 1753.jpg, 1753 Van Keulen Map of Ari Atoll

Ari Atoll (also called Alif or Alifu Atoll) is one of the natural atolls of the Maldives. It is one of the biggest atolls and is located in the west of the archipelago. The almost rectangular alignment spreads the islands over an area of about ...

File:Huvadu 1753.jpg, 1753 Van Keulen Map of Huvadu Atoll

Huvadhu, Suvadive, Suvaidu or Suvadiva is the atoll with most islands in the world. The atoll is located in the Indian Ocean. It is south of the Suvadiva Channel in the Republic of Maldives with a total area of 3152 km2, of which 38.5 ...

(inaccurate)

British protectorate

The British expelled the Dutch from Ceylon in 1796 and included Maldives as a British protected area.

Britain got entangled with the Maldives as a result of domestic disturbances which targeted the settler community of

Bora merchants who were British subjects in the 1860s. Rivalry between two dominant families, the Athireege clan and the Kakaage clan was resolved with former winning the favour of the British authorities in Ceylon. The status of Maldives as a

British protectorate was officially recorded in an 1887 agreement.

On 16 December 1887, the Sultan of the Maldives signed a contract with the British

Governor of Ceylon {{Use dmy dates, date=November 2019

The Governor of Ceylon can refer to historical vice-regal representatives of three colonialism, colonial powers:

Portuguese Ceylon

* List of Captains of Portuguese Ceylon (1518–1551)

* List of Captain-majors of ...

turning the Maldives into a

British protected state, thus giving up the islands'

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

in matters of

foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

, but retaining internal self-government. The British government promised military protection and non-interference in local administration, which continued to be regulated by

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

traditional institutions, in exchange for an annual

tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conqu ...

. The status of the islands was akin to other British protectorates in the Indian Ocean region, including

Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

and the

Trucial States

The Trucial States ( '), also known as the Trucial Coast ( '), the Trucial Sheikhdoms ( '), Trucial Arabia or Trucial Oman, was the name the British government gave to a group of tribal confederations in southeastern Arabia whose leaders had s ...

.

During the British era, which lasted until 1965, Maldives continued to be ruled under a succession of

sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

s.

It was a period during which the Sultan's authority and powers were increasingly and decisively taken over by the Chief Minister, much to the chagrin of the British Governor-General who continued to deal with the ineffectual Sultan. Consequently, Britain encouraged the development of a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, and the first Constitution was proclaimed in 1932. However, the new arrangements favoured neither the aging Sultan nor the wily Chief Minister, but rather a young crop of British-educated reformists. As a result, angry mobs were instigated against the Constitution, which was publicly torn up.

The Maldives were only marginally touched by the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The

Italian auxiliary cruiser Ramb I was sunk off

Addu Atoll

Addu Atoll, also known as Seenu Atoll, is the southernmost atoll of the Maldives. Addu Atoll, together with Fuvahmulah, located 40 km north of Addu Atoll, extend the Maldives into the Southern Hemisphere. Addu Atoll is located 540 k ...

in 1941.

After the death of Sultan

Majeed Didi and his son, the members of the parliament elected

Muhammad Amin Didi

Sumuvvul Ameer Mohamed Amin Dhoshimeynaa Kilegefaanu ( Dhivehi: ސުމުއްވުލް އަމީރު މުހައްމަދު އަމީން ދޮށިމޭނާ ކިލެގެފާނު) (July 20, 1910 – January 19, 1954), popularly known as Mohamed Amin Did ...

as the next person in line to succeed the sultan. But Didi refused to take up the throne. So, a

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

was held and Maldives became a republic, with Amin Didi as

first elected President, having abolished the 812-year-old sultanate. While serving as prime minister during the 1940s, Didi nationalized the fish export industry.

As president he is remembered as a reformer of the education system and a promoter of

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

.

Yet, while he was in Ceylon for medical treatment, a revolution was brought by the people of

Malé

Malé (, ; dv, މާލެ) is the capital and most populous city of the Maldives. With a population of 252,768 and an area of , it is also one of the most densely populated cities in the world. The city is geographically located at the southern ...

, headed by his deputy

Velaanaagey Ibraahim Didi. When Amin Did returned he was confined to

Dhoonidhoo Island. He escaped to Malé and tried to take control of Bandeyrige, but was beaten by an angry mob and died soon after.

After the fall of President

Mohamed Amin Didi

Sumuvvul Ameer Mohamed Amin Dhoshimeynaa Kilegefaanu (Dhivehi: ސުމުއްވުލް އަމީރު މުހައްމަދު އަމީން ދޮށިމޭނާ ކިލެގެފާނު) (July 20, 1910 – January 19, 1954), popularly known as Mohamed Amin Didi ...

,

a referendum was held and 98% of the people voted in favour of restoration of the monarchy, so the country was again declared a Sultanate. A new People's Majilis was elected, as the former had been dissolved after the end of the revolution. The members of the special majilis decided to take a secret vote to elect a sultan, and Prince

Muhammad Fareed Didi was elected as the 84th Sultan in 1954. His first Prime minister was Ehgamugey Ibraahim Ali Didi (later Ibraahim Faamuladheyri Kilegefaan). On 11 December 1957, the prime minister was forced to resign and Velaanagey Ibrahim Nasir was elected as the new prime minister the following day.

Part of the reception-room of the High Priest, showing the bed and shields used by the fencers, 1885 - The Graphic 1886.gif, Illustration by CW Rosett in ''The Graphic'', depicting veranda sing (Fendaamathi Undholi) of royal palace (1885).

Thottiyan hut.jpg, A hut of Tottiyan from Male island. Illustration b Edgar Thurston, 1909.

Mohamed Amin.jpg, Muhammad Amin Didi

Sumuvvul Ameer Mohamed Amin Dhoshimeynaa Kilegefaanu ( Dhivehi: ސުމުއްވުލް އަމީރު މުހައްމަދު އަމީން ދޮށިމޭނާ ކިލެގެފާނު) (July 20, 1910 – January 19, 1954), popularly known as Mohamed Amin Did ...

, President of the First Maldivian Republic (1953)

British military presence and Suvadive secession

Beginning in the 1950s, political history in Maldives was largely influenced by the British military presence in the islands.

In 1954 the restoration of the sultanate perpetuated the rule of the past.

[.] Two years later, the United Kingdom obtained permission to reestablish its wartime

RAF Gan

Royal Air Force Station Gan, commonly known as RAF Gan, is a former Royal Air Force station on Gan island, the southern-most island of Addu Atoll, which is part of the larger groups of islands which form the Maldives, in the middle of the Ind ...

airfield in the southernmost

Addu Atoll

Addu Atoll, also known as Seenu Atoll, is the southernmost atoll of the Maldives. Addu Atoll, together with Fuvahmulah, located 40 km north of Addu Atoll, extend the Maldives into the Southern Hemisphere. Addu Atoll is located 540 k ...

.

Maldives granted the British a 100-year lease on Gan that required them to pay £2,000 a year, as well as some 440,000 square metres on Hitaddu for radio installations.

This served as a staging post for British military flights to the Far East and Australia, replacing

RAF Mauripur

RAF Mauripur was a Royal Air Force station in British India 4 miles north west of the centre of Karachi. It is now known as Masroor Airbase.

History

RAF Mauripur opened in 1942 as a transit airfield allowing RAF Drigh Road to concentrate on ...

in Pakistan which had been relinquished in 1956.

In 1957, however, the new prime minister,

Ibrahim Nasir, called for a review of the agreement in the interest of shortening the lease and increasing the annual payment,

and announced a new tax on boats. But Nasir was challenged in 1959 by a local secessionist movement in the southern atolls that benefited economically from the British presence on

Gan

The word Gan or the initials GAN may refer to:

Places

*Gan, a component of Hebrew placenames literally meaning "garden"

China

* Gan River (Jiangxi)

* Gan River (Inner Mongolia),

* Gan County, in Jiangxi province

* Gansu, abbreviated ''Gā ...

.

This group cut ties with the Maldives government and formed an independent state, the

United Suvadive Republic

The United Suvadive Republic (Dhivehi: އެކުވެރި ސުވާދީބު ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ) was a short-lived breakaway state from the Kingdom of Maldives between 1958 and 1963 consisting of the three southern atolls of the Maldive archip ...

, with

Abdullah Afif as president.

The short-lived state (1959–63) had a combined population of 20,000 inhabitants scattered over

Huvadu,

Addu and

Fua Mulaku.

Afeef pleaded for support and recognition from Britain in the edition of 25 May 1959 of ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' of London.

Instead the initial British measure of lukewarm support for the small breakaway nation was withdrawn in 1961, when the British signed a treaty with the Maldive Islands without involving Afeef. Following that treaty the Suvadives had to endure an economic embargo. In 1962 Nasir sent gunboats from Malé with government police on board to eliminate elements opposed to his rule.

One year later the Suvadive republic was scrapped and Abdullah Afif went into exile to the

Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, V ...

,

where he died in 1993.

Meanwhile, in 1960 the Maldives had allowed the United Kingdom to continue to use both the

Gan

The word Gan or the initials GAN may refer to:

Places

*Gan, a component of Hebrew placenames literally meaning "garden"

China

* Gan River (Jiangxi)

* Gan River (Inner Mongolia),

* Gan County, in Jiangxi province

* Gansu, abbreviated ''Gā ...

and the Hitaddu facilities for a thirty-year period, with the payment of £750,000 over the period of 1960 to 1965 for the purpose of Maldives' economic development.

The base was closed in 1976 as part of the larger British withdrawal of permanently stationed forces '

East of Suez

East of Suez is used in British military and political discussions in reference to interests beyond the European theatre, and east of the Suez Canal, and may or may not include the Middle East. ' initiated by Labour government of

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

.

RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

camp on Addu Atoll established in 1944 as a base for flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

s operating in the Indian Ocean

Royal Air Force Operations in the Far East, 1941-1945 CF620.jpg, RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of Sunderland in North East ...

moored in the lagoon at Addu Atoll, during WWII

File:Royal Air Force Operations in the Far East, 1941-1945 CF632.jpg, A wind break constructed from ration boxes protects the small RAF camp at Kelai, Maldive Islands, which serves as a refuelling base for flying boats operating in the Indian Ocean.

Abdullah Afeef.png, Abdullah Afif, leader of the secessionist United Suvadive Republic

The United Suvadive Republic (Dhivehi: އެކުވެރި ސުވާދީބު ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ) was a short-lived breakaway state from the Kingdom of Maldives between 1958 and 1963 consisting of the three southern atolls of the Maldive archip ...

(1959-1963)

SuvadiveCOA.png, Coat of arms of the secessionist United Suvadive Republic

The United Suvadive Republic (Dhivehi: އެކުވެރި ސުވާދީބު ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ) was a short-lived breakaway state from the Kingdom of Maldives between 1958 and 1963 consisting of the three southern atolls of the Maldive archip ...

Independence

On 26 July 1965, Maldives gained independence under an agreement signed with United Kingdom.

The British government retained the use of the

Gan

The word Gan or the initials GAN may refer to:

Places

*Gan, a component of Hebrew placenames literally meaning "garden"

China

* Gan River (Jiangxi)

* Gan River (Inner Mongolia),

* Gan County, in Jiangxi province

* Gansu, abbreviated ''Gā ...

and Hithadhoo facilities.

In a national

referendum in March 1968, Maldivians abolished the sultanate and established a republic.

In line with the broader British policy of

decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

on 26 July 1965 an agreement was signed on behalf of His Majesty the Sultan by

Ibrahim Nasir Rannabandeyri Kilegefan, Prime Minister, and on behalf of

Her Majesty The Queen by Sir

Michael Walker, British Ambassador designate to the Maldive Islands, which ended the British responsibility for the defence and external affairs of the Maldives. The islands thus achieved full political independence, with the ceremony taking place at the British High Commissioner's Residence in

Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

. After this, the sultanate continued for another three years under

Muhammad Fareed Didi, who declared himself King rather than Sultan.

On 15 November 1967, a vote was taken in parliament to decide whether the Maldives should continue as a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

or become a republic. Of the 44 members of parliament, forty voted in favour of a republic.

On 15 March 1968, a national referendum was held on the question, and 81.23% of those taking part voted in favour of establishing a republic. The republic was declared on 11 November 1968, thus ending the 853-year-old monarchy, which was replaced by a republic under the presidency of

Ibrahim Nasir, the former prime minister. As the King had held little real power, this was seen as a cosmetic change and required few alterations in the structures of government.

Nasir Presidency

The Second Republic was proclaimed in November 1968 under the presidency of

Ibrahim Nasir, who had increasingly dominated the political scene.

Under the new constitution, Nasir was elected indirectly to a four-year presidential term by the

Majlis

( ar, المجلس, pl. ') is an Arabic term meaning "sitting room", used to describe various types of special gatherings among common interest groups of administrative, social or religious nature in countries with linguistic or cultural conne ...

(legislature)

and his candidacy later ratified by

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

. He appointed Ahmed Zaki as the new prime minister.

In 1973 Nasir was elected to a second term under the constitution as amended in 1972, which extended the presidential term to five years and which also provided for the election of the prime minister by the

Majlis

( ar, المجلس, pl. ') is an Arabic term meaning "sitting room", used to describe various types of special gatherings among common interest groups of administrative, social or religious nature in countries with linguistic or cultural conne ...

.

In March 1975, newly elected prime minister Zaki was arrested in a bloodless coup and was banished to a remote atoll.

Observers suggested that Zaki was becoming too popular and hence posed a threat to the Nasir faction.

During the 1970s, the economic situation in Maldives suffered a setback when the Sri Lankan market for Maldives' main export of dried fish collapsed.

[.] Adding to the problems was the British decision in 1975 to close its airfield on

Gan

The word Gan or the initials GAN may refer to:

Places

*Gan, a component of Hebrew placenames literally meaning "garden"

China

* Gan River (Jiangxi)

* Gan River (Inner Mongolia),

* Gan County, in Jiangxi province

* Gansu, abbreviated ''Gā ...

.

A steep commercial decline followed the evacuation of Gan in March 1976.

As a result, the popularity of Nasir's government suffered.

Maldives's 20-year period of authoritarian rule under Nasir abruptly ended in 1978 when he fled to Singapore.

A subsequent investigation revealed that he had absconded with millions of dollars from the state treasury.

Nasir is widely credited with modernising the long-isolated and nearly unknown Maldives and opening them up to the rest of the world, including by building the first international airport (

Malé International Airport, 1966) and bringing the Maldives to United Nations membership. He laid the foundations of the nation by modernising the fisheries industry with mechanized vessels and starting the

tourism industry

Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also the theory and practice of touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tours. The World Tourism Organization defines tourism ...

– the two prime drivers of today's Maldivian economy.

He was credited with many other improvements such as introducing an English-based modern curriculum to government-run schools and granting vote to Maldivian women in 1964. He brought television and radio to the country with formation of ''

Television Maldives

Television Maldives is the public service broadcasting TV channel of the Maldives. It was formed on March 29, 1978.

In 2009, the management of Television Maldives (TVM) and national radio, Dhivehiraajjeyge Adu Voice_of_Maldives">nowiki/>Voice_o ...

'' and ''

Radio Maldives'' for broadcasting radio signals nationwide. He abolished ''Vaaru'', a tax on the people living on islands outside

Malé

Malé (, ; dv, މާލެ) is the capital and most populous city of the Maldives. With a population of 252,768 and an area of , it is also one of the most densely populated cities in the world. The city is geographically located at the southern ...

.

Tourism in the Maldives