History Of Phoenix, Arizona on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The history of

At some point in the centuries before the Common Era, a group of archaic Indians migrated north from Mexico, bringing with them an agrarian society, different from the hunter-gatherer cultures of most of the archaic Indian tribes. Evidence of this culture has been uncovered in the Tucson area, consisting of slab-lined storage pits, and "sleeping circles". This archaic Indian culture would give rise to the Hohokam peoples, who, right around the beginning of the Common Era, moved further north and settled in the Salt River basin.

At some point in the centuries before the Common Era, a group of archaic Indians migrated north from Mexico, bringing with them an agrarian society, different from the hunter-gatherer cultures of most of the archaic Indian tribes. Evidence of this culture has been uncovered in the Tucson area, consisting of slab-lined storage pits, and "sleeping circles". This archaic Indian culture would give rise to the Hohokam peoples, who, right around the beginning of the Common Era, moved further north and settled in the Salt River basin.

For more than 2,000 years, the Hohokam peoples occupied the land that would become Phoenix. Hohokam is a present-day name given to the occupants of central and southern Arizona who lived here between about the year 1 and 1450 CE (current era). It is derived from the Pima Indian (Akimel O'odham) word for "those who have gone" or "all used up".

The Hohokam inhabitation of the valley is broken up by paleontologists into five periods. The earliest period is known as the Pioneer Period, which lasted roughly from 1–700 AD, and was categorized by groups of shallow pit houses, and by its end the first canals were being used for irrigation, and the first decorated ceramics were appearing. This was followed by the Colonial Period (c. 700 – 900 AD), during which time the irrigation system was expanded and the community sizes grew, as did the size of the dwellings. Rock art and ballcourts began to appear, and cremations became the usual form of burial. 900 to 1150 AD, referred to as the Sedentary Period, again saw the expansion of the settlements and the canal system. Platform mounds began to be built, and plazas and the ballcourts which began to appear in the last period, became more prevalent in the larger settlements. The final period, the Classic Period, lasted approximately from 1150 AD until 1450 AD. The number of villages declined during this period, but the size of the remaining settlements increased.

During their inhabitation of the valley, the Hohokam created roughly 135 miles (217 km) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable. Paths of these canals would later become used for the modern

For more than 2,000 years, the Hohokam peoples occupied the land that would become Phoenix. Hohokam is a present-day name given to the occupants of central and southern Arizona who lived here between about the year 1 and 1450 CE (current era). It is derived from the Pima Indian (Akimel O'odham) word for "those who have gone" or "all used up".

The Hohokam inhabitation of the valley is broken up by paleontologists into five periods. The earliest period is known as the Pioneer Period, which lasted roughly from 1–700 AD, and was categorized by groups of shallow pit houses, and by its end the first canals were being used for irrigation, and the first decorated ceramics were appearing. This was followed by the Colonial Period (c. 700 – 900 AD), during which time the irrigation system was expanded and the community sizes grew, as did the size of the dwellings. Rock art and ballcourts began to appear, and cremations became the usual form of burial. 900 to 1150 AD, referred to as the Sedentary Period, again saw the expansion of the settlements and the canal system. Platform mounds began to be built, and plazas and the ballcourts which began to appear in the last period, became more prevalent in the larger settlements. The final period, the Classic Period, lasted approximately from 1150 AD until 1450 AD. The number of villages declined during this period, but the size of the remaining settlements increased.

During their inhabitation of the valley, the Hohokam created roughly 135 miles (217 km) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable. Paths of these canals would later become used for the modern

As the Civil War came to a close, settlers from the north and east began to encroach on the Valley of the Sun. The US Army set up Fort McDowell on the

As the Civil War came to a close, settlers from the north and east began to encroach on the Valley of the Sun. The US Army set up Fort McDowell on the  The Board of Supervisors in Yavapai County, which at the time encompassed Phoenix, officially recognized the new town on May 4, 1868, and formed an election precinct. The first post office was established on June 15, 1868, located in Swilling's homestead, with Swilling serving as the postmaster. With the number of residents growing (the 1870 U.S. census reported a total Salt River Valley population of 240), a town site needed to be selected. On October 20, 1870, the residents held a meeting to decide where to locate it. The decision was hotly contested between two sites: the original settlement around Swilling's farm, and a site about a mile to the west, which was supported by the newly founded "Salt River Valley Town Association" (SRVTA). Due to economic considerations benefitting the members of SRVTA, the more westerly townsite was selected, and a plot of land was purchased in what is now the downtown business section.

The Board of Supervisors in Yavapai County, which at the time encompassed Phoenix, officially recognized the new town on May 4, 1868, and formed an election precinct. The first post office was established on June 15, 1868, located in Swilling's homestead, with Swilling serving as the postmaster. With the number of residents growing (the 1870 U.S. census reported a total Salt River Valley population of 240), a town site needed to be selected. On October 20, 1870, the residents held a meeting to decide where to locate it. The decision was hotly contested between two sites: the original settlement around Swilling's farm, and a site about a mile to the west, which was supported by the newly founded "Salt River Valley Town Association" (SRVTA). Due to economic considerations benefitting the members of SRVTA, the more westerly townsite was selected, and a plot of land was purchased in what is now the downtown business section.

On February 14, 1871, following a vote by the territorial legislature, Governor Anson P.K. Safford issued a proclamation creating Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County. In that same proclamation, he named Phoenix the county seat, but that nomination was subject to the approval of the voters. An election was held in May, 1871, at which Phoenix' selection as the county seat was ratified. Quite a few members of SRVTA were also elected to county positions: among them were John Alsap (Probate Judge), William Hancock (Surveyor) and Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff. Barnum ran unopposed as the other two candidates had a shootout that left one dead and the other withdrawing from the race. The town's first government consisted of three commissioners.

Several lots of land were sold in 1870 at an average price of $48. The first church opened in 1871, as did the first store. The first public school class was held on September 5, 1872, in the courtroom of the county building. By October 1873, a small school was completed on Center Street (now Central Avenue). The total value of the Phoenix Townsite was $550, with downtown lots selling for between $7 and $11 each.

By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, sixteen saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government was no longer working well. At a mass meeting on Oct. 20, 1875, an election was held to select three village trustees and other officials. Those first three trustees were John Smith (Chairman), Charles W. Stearns (treasurer), and Capt. Hancock (secretary). 1878 saw the opening of the first bank, a branch of the Bank of Arizona, and by 1880, Phoenix's population stood at 2,453. Later in 1880 the first legal hanging in Maricopa County was held, performed in town.

On February 14, 1871, following a vote by the territorial legislature, Governor Anson P.K. Safford issued a proclamation creating Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County. In that same proclamation, he named Phoenix the county seat, but that nomination was subject to the approval of the voters. An election was held in May, 1871, at which Phoenix' selection as the county seat was ratified. Quite a few members of SRVTA were also elected to county positions: among them were John Alsap (Probate Judge), William Hancock (Surveyor) and Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff. Barnum ran unopposed as the other two candidates had a shootout that left one dead and the other withdrawing from the race. The town's first government consisted of three commissioners.

Several lots of land were sold in 1870 at an average price of $48. The first church opened in 1871, as did the first store. The first public school class was held on September 5, 1872, in the courtroom of the county building. By October 1873, a small school was completed on Center Street (now Central Avenue). The total value of the Phoenix Townsite was $550, with downtown lots selling for between $7 and $11 each.

By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, sixteen saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government was no longer working well. At a mass meeting on Oct. 20, 1875, an election was held to select three village trustees and other officials. Those first three trustees were John Smith (Chairman), Charles W. Stearns (treasurer), and Capt. Hancock (secretary). 1878 saw the opening of the first bank, a branch of the Bank of Arizona, and by 1880, Phoenix's population stood at 2,453. Later in 1880 the first legal hanging in Maricopa County was held, performed in town.

By 1881, Phoenix' continued growth made the existing village structure with a board of trustees obsolete. The 11th Territorial Legislature passed "The Phoenix Charter Bill", incorporating Phoenix and providing for a mayor-council government. The bill was signed by Governor John C. Fremont on February 25, 1881, officially incorporating Phoenix with a population of approximately 2,500. On May 3, 1881, Phoenix held its first city election. Judge John T. Alsap defeated

By 1881, Phoenix' continued growth made the existing village structure with a board of trustees obsolete. The 11th Territorial Legislature passed "The Phoenix Charter Bill", incorporating Phoenix and providing for a mayor-council government. The bill was signed by Governor John C. Fremont on February 25, 1881, officially incorporating Phoenix with a population of approximately 2,500. On May 3, 1881, Phoenix held its first city election. Judge John T. Alsap defeated  The coming of the railroad in the 1880s was the first of several important events that revolutionized the economy of Phoenix. A spur of the

The coming of the railroad in the 1880s was the first of several important events that revolutionized the economy of Phoenix. A spur of the

On February 14, 1912, under President

On February 14, 1912, under President  In 1913 Phoenix adopted a new form of government, changing from a mayor-council system to council-manager, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate, and by the end of its first eight years under statehood, Phoenix' population had grown to 29,053. Two thousand were attending Phoenix Union High School. In 1920 Phoenix built its first skyscraper, the Heard Building. In 1928

In 1913 Phoenix adopted a new form of government, changing from a mayor-council system to council-manager, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate, and by the end of its first eight years under statehood, Phoenix' population had grown to 29,053. Two thousand were attending Phoenix Union High School. In 1920 Phoenix built its first skyscraper, the Heard Building. In 1928

The new 20 story

The new 20 story

online review

excerpt and text search

* ; well illustrated popular history

excerpt and text search

in JSTOR

* Luckingham, Bradford. ''Minorities in Phoenix: A Profile of Mexican American, Chinese American, and African American Communities, 1860–1992'' (1994) * Melcher, Mary. "Blacks and Whites Together: Interracial Leadership in the Phoenix Civil Rights Movement." ''Journal of Arizona History'' (1991): 195–216. * * Whitaker, Matthew C. "The rise of Black Phoenix: African-American migration, settlement and community development in Maricopa County, Arizona 1868–1930." ''Journal of Negro History'' (2000) 85#3 pp. 197–209

online

online

* Fink, Jonathan. "Phoenix, the Role of the University, and the Politics of Green-Tech." ''Sustainability in America’s Cities. Island Press/Center for Resource Economics'' (2011) pp. 69–90. * Gober, Patricia, and Barbara Trapido-Lurie. ''Metropolitan Phoenix: Place making and community building in the desert'' (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). * Grineski, Sara E., Bob Bolin, and Victor Agadjanian. "Tuberculosis and urban growth: class, race and disease in early Phoenix, Arizona, USA." ''Health & place'' (2006) 12#4 pp: 603–616. * Judkins, Gabe. "Declining cotton cultivation in Maricopa County, Arizona: An examination of macro-and micro-scale driving forces," ''Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers'' (2008): 70#1 pp. 70–95. * Keys, Eric, Elizabeth A. Wentz, and Charles L. Redman. "The spatial structure of land use from 1970–2000 in the Phoenix, Arizona, metropolitan area." ''Professional Geographer'' (2007) 59#1 pp. 131–147. * Larsen, Larissa, and Sharon L. Harlan. "Desert dreamscapes: residential landscape preference and behavior." ''Landscape and urban planning'' 78.1–2 (2006): 85–100. * {{cite journal , last1 = Larson , first1 = Kelli L. , last2 = Gustafson , first2 = Annie , last3 = Hirt , first3 = Paul , date=April 2009 , title = Insatiable Thirst and a Finite Supply: An Assessment of Municipal Water-Conservation Policy in Greater Phoenix, Arizona, 1980–2007 , journal=Journal of Policy History , volume = 21 , issue = 2 , pages = 107–137 , doi = 10.1017/S0898030609090058 , doi-access= free * Larson, Kelli L., et al. "Vulnerability of water systems to the effects of climate change and urbanization: A comparison of Phoenix, Arizona and Portland, Oregon (USA)." ''Environmental management'' (2013) 52#1 pp. 179–195. * Ross, Andrew. ''Bird on fire: Lessons from the world's least sustainable city'' (Oxford UP, 2011). * Schweikart, Larry. "Collusion or Competition?: Another Look at Banking During Arizona's Boom Years, 1950–1965." ''Journal of Arizona History'' (1987): 189–200. * Zarbin, Earl A. ''All the Time a Newspaper: The First 100 Years of the Arizona Republic'' (1990)

emphasis pre-1914 History of the American West

The history of

The history of Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix ( ; nv, Hoozdo; es, Fénix or , yuf-x-wal, Banyà:nyuwá) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities and towns in Arizona#List of cities and towns, most populous city of the U.S. state of Arizona, with 1 ...

, goes back millennia, beginning with nomadic paleo-Indians who existed in the Americas in general, and the Salt River Valley

The Salt River Valley is an extensive valley on the Salt River in central Arizona, which contains the Phoenix Metropolitan Area.

Although this geographic term still identifies the area, the name "Valley of the Sun" popularly replaced the usage ...

in particular, about 7,000 BC until about 6,000 BC. Mammoths were the primary prey of hunters. As that prey moved eastward, they followed, vacating the area. Other nomadic tribes (archaic Indians) moved into the area, mostly from Mexico to the south and California to the west. Around approximately 1,000 BC, the nomadic began to be accompanied by two other types of cultures, commonly called the farmers and the villagers, prompted by the introduction of maize into their culture. Out of these archaic Indians, the Hohokam civilization arose. The Hohokam first settled the area around 1 AD, and in about 500 years, they had begun to establish the canal system which enabled agriculture to flourish in the area. They suddenly disappeared by 1450, for unknown reasons. By the time the first Europeans arrived at the beginning of the 16th century, the two main groups of native Indians who inhabited the area were the O'odham

The O'odham peoples, including the Tohono O'odham, the Pima or Akimel O'odham, and the Hia C-ed O'odham, are indigenous Uto-Aztecan peoples of the Sonoran desert in southern and central Arizona and northern Sonora, united by a common herita ...

and Sobaipuri

The Sobaipuri were one of many indigenous groups occupying Sonora and what is now Arizona at the time Europeans first entered the American Southwest. They were a Piman or O'odham group who occupied southern Arizona and northern Sonora (the Pimer� ...

tribes.

While the first explorers were Spanish, their attempts at settlement were confined to Tucson

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

and the south before 1800. Central Arizona was first settled during the early 19th century by American settlers. The city of Phoenix's story begins as people from those settlements expanded south, in conjunction with the establishment of a military outpost to the east of current day Phoenix.

The town of Phoenix was settled in 1867, and incorporated in 1881 as the City of Phoenix. Phoenix served as an agricultural area that depended on large-scale irrigation projects. Until World War II, the economy was based on the "Five C's": cotton, citrus, cattle, climate, and copper. The city provided retail, wholesale, banking, and governmental services for central Arizona, and was gaining a national reputation among winter tourists. The post World War Two years saw the city beginning to grow more rapidly, as many men who had trained in the military installations in the valley, returned, bringing their families. The population growth was further stimulated in the 1950s, in part because of the availability of air conditioning, which made the very hot dry summer heat tolerable, as well as an influx of industry, led by high tech companies. The population growth rate of the Phoenix metro area has been nearly 4% per year for the past 40 years. That growth rate slowed during the Great Recession

The Great Recession was a period of marked general decline, i.e. a recession, observed in national economies globally that occurred from late 2007 into 2009. The scale and timing of the recession varied from country to country (see map). At ...

but the U.S. Census Bureau predicted it would resume as the nation's economy recovered, and it already has begun to do so. It is currently the fifth largest city in the United States by population.

Native American period

Paleo and archaic Indian period

The first inhabitants of the desert southwest, including what would become Phoenix, called Paleo-Indians, were hunters and gatherers. The term "paleo", is derived from the Greek word “palaios,” meaning ancient. They hunted Pleistocene animals, such as mammoths, mastodons, giant bison, ancient horses, camels, and giant sloths, remains of which have been discovered in the Salt River Valley. Inhabiting the southwestern United States and northern Mexico for tens of thousands of years, when the prey they depended on left the area, they followed in approximately 9,000 BC. After the departure of the paleo-Indians, archaic Indians moved into the American Southwest. This period lasted from roughly about 7,000 BC until the onset of the Christian era. Consisting of small bands of hunters and gatherers, these nomads traveled throughout the area for millennia, until about 3,000 years ago when their culture began to become an agricultural lifestyle. At about this time, the introduction of the cultivation of maize further contributed to the agrarian culture. As time went on and farming became more established, groups began developing differences in their material culture. Through these differences, cultures of the Southwest became more visibly distinct from one another, which would be broken down into the farmers, the villagers, and the nomads. From the farmers culture would emerge a tribe known as the Hohokam.Hohokam period

For more than 2,000 years, the Hohokam peoples occupied the land that would become Phoenix. Hohokam is a present-day name given to the occupants of central and southern Arizona who lived here between about the year 1 and 1450 CE (current era). It is derived from the Pima Indian (Akimel O'odham) word for "those who have gone" or "all used up".

The Hohokam inhabitation of the valley is broken up by paleontologists into five periods. The earliest period is known as the Pioneer Period, which lasted roughly from 1–700 AD, and was categorized by groups of shallow pit houses, and by its end the first canals were being used for irrigation, and the first decorated ceramics were appearing. This was followed by the Colonial Period (c. 700 – 900 AD), during which time the irrigation system was expanded and the community sizes grew, as did the size of the dwellings. Rock art and ballcourts began to appear, and cremations became the usual form of burial. 900 to 1150 AD, referred to as the Sedentary Period, again saw the expansion of the settlements and the canal system. Platform mounds began to be built, and plazas and the ballcourts which began to appear in the last period, became more prevalent in the larger settlements. The final period, the Classic Period, lasted approximately from 1150 AD until 1450 AD. The number of villages declined during this period, but the size of the remaining settlements increased.

During their inhabitation of the valley, the Hohokam created roughly 135 miles (217 km) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable. Paths of these canals would later become used for the modern

For more than 2,000 years, the Hohokam peoples occupied the land that would become Phoenix. Hohokam is a present-day name given to the occupants of central and southern Arizona who lived here between about the year 1 and 1450 CE (current era). It is derived from the Pima Indian (Akimel O'odham) word for "those who have gone" or "all used up".

The Hohokam inhabitation of the valley is broken up by paleontologists into five periods. The earliest period is known as the Pioneer Period, which lasted roughly from 1–700 AD, and was categorized by groups of shallow pit houses, and by its end the first canals were being used for irrigation, and the first decorated ceramics were appearing. This was followed by the Colonial Period (c. 700 – 900 AD), during which time the irrigation system was expanded and the community sizes grew, as did the size of the dwellings. Rock art and ballcourts began to appear, and cremations became the usual form of burial. 900 to 1150 AD, referred to as the Sedentary Period, again saw the expansion of the settlements and the canal system. Platform mounds began to be built, and plazas and the ballcourts which began to appear in the last period, became more prevalent in the larger settlements. The final period, the Classic Period, lasted approximately from 1150 AD until 1450 AD. The number of villages declined during this period, but the size of the remaining settlements increased.

During their inhabitation of the valley, the Hohokam created roughly 135 miles (217 km) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable. Paths of these canals would later become used for the modern Arizona Canal

The Arizona Canal is a major canal in central Maricopa County that led to the founding of several communities, now among the wealthier neighborhoods of suburban Phoenix, constructed in the late 1880s. Flood irrigation of residential yards is s ...

, Central Arizona Project

The Central Arizona Project (CAP) is a 336 mi (541 km) diversion canal in Arizona in the southern United States.

The aqueduct diverts water from the Colorado River to the Bill Williams Wildlife Refuge south portion of Lake Havasu ne ...

Canal, and the Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct. The irrigation provided by these canals enabled the Hohokam culture to spread throughout the valley, and by 1300 AD, the Hohokam were the largest population in the prehistoric Southwest, and the largest native population north of Mexico City. This was the largest single body of land irrigated in prehistoric times in North or South America, perhaps in the world. The Hohokam also carried out extensive trade with the nearby Anasazi

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, a ...

, Mogollon and Sinagua

The Sinagua were a pre-Columbian culture that occupied a large area in central Arizona from the Little Colorado River, near Flagstaff, to the Verde River, near Sedona, including the Verde Valley, area around San Francisco Mountain, and signifi ...

, as well as with the more distant Mesoamerican

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Withi ...

civilizations like the Aztecs. It is believed that a Hohokam witness of the supernova that occurred in 1006 CE created a representation of the event in the form of a petroglyph that can be found in the White Tank Mountain Regional Park

The White Tank Mountain Regional Park is a large regional park located in west-central Maricopa County, Arizona. Encompassing of desert and mountain landscape, it is the largest regional park in the county. The bulk of the White Tank Mountain ...

west of Phoenix. If confirmed, this is the only known Native American representation of the supernova.

At some point in the mid-15th century, the Hohokam culture simply disappeared from the area, speculation as to why as focused on periods of drought and severe floods during this period.

Modern Indian period

After the departure of the Hohokam, groups ofAkimel O'odham

The Pima (or Akimel O'odham, also spelled Akimel Oʼotham, "River People," formerly known as ''Pima'') are a group of Native Americans living in an area consisting of what is now central and southern Arizona, as well as northwestern Mexico in ...

(commonly known as Pima), Tohono O’odham and Maricopa

Maricopa can refer to:

Places

* Maricopa, Arizona, United States, a city

** Maricopa Freeway, a piece of I-10 in Metropolitan Phoenix

** Maricopa station, an Amtrak station in Maricopa, Arizona

* Maricopa County, Arizona, United States

* Marico ...

tribes began to use the area, as well as segments of the Yavapai

The Yavapai are a Native American tribe in Arizona. Historically, the Yavapai – literally “people of the sun” (from ''Enyaava'' “sun” + ''Paay'' “people”) – were divided into four geographical bands who identified as separate, i ...

and Apache.

The O'odham were offshoots of the Sobaipuri

The Sobaipuri were one of many indigenous groups occupying Sonora and what is now Arizona at the time Europeans first entered the American Southwest. They were a Piman or O'odham group who occupied southern Arizona and northern Sonora (the Pimer� ...

tribe, who in turn were thought to be the descendants of the formerly urbanized Hohokam. The two O'odham peoples were split between the Akimel (river people) and Tohono (desert people). The Akimel O’odham were the major Indian group in the area, and lived in small villages, with well-defined irrigation systems, which spread over the entire Gila River Valley, from Florence in the east to the Estrellas in the west. Their crops included corn, beans and squash for food, while cotton and tobacco were also cultivated. Mostly a peaceful group, they did band together with the Maricopa for their mutual protection against incursions by both the Yuma and Apache tribes.

The Tohono O'odham lived in the region as well, but their main concentration was further to south of the Pima, and stretched all the way to the Mexican border. Originally known to the European settlers as the Papago (which literally means " tepary-bean eater"), in recent times the tribe has dropped usage of that name. Living in small settlements, the O'odham were seasonal farmers who took advantage of the rains, rather than the large-scale irrigation of the Akimel. They grew crops such as sweet Indian corn, tapery beans, squash, lentils sugar cane and melons, as well as taking advantage of native plants, such as saguaro fruits, cholla buds, mesquite tree beans, and mesquite candy (sap from the mesquite tree). They also hunted local game such as deer, rabbit and javalina for meat.

The Maricopa are part of the larger Yuma people, however they migrated east from the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers in the early 1800s, when they began to be enemies with their Yuma brethren, settling amongst the existing communities of the Akimel O'odham.

European arrival

Spanish explorers most likely traveled through the area in the 16th century. They left accounts of their travels, and also left behind European diseases that ravaged Indian tribes with no immunity, especially smallpox, measles and influenza. The Spanish opened a mission in the Tucson area, but made no settlements anywhere near Phoenix. When theMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

ended in 1848, most of Mexico's northern zone passed to United States control, and a portion of it was made the New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of ''Santa Fe de Nuevo México ...

(including what is now Phoenix) shortly afterward. Then In the Gadsden Purchase of 1853 the U.S. promised to honor all land rights of the area, including those of the O'odham. The O'odham gained full constitutional rights.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the Salt River and Gila River Valleys, which comprise much of the territory which makes up Phoenix today, were claimed by both sides in the conflict. Confederate Arizona

Arizona Territory, Colloquialism, colloquially referred to as Confederate Arizona, was an Constitution of the Confederate States, organized incorporated territory of the Confederate States that existed from August 1, 1861 to May 26, 1865, wh ...

was officially claimed by The South, and formally created by a proclamation by Jefferson Davis on February 14, 1862. Its capital was at Mesilla, in New Mexico. The North claimed the Salt River Valley as part of the Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of ...

, formed by Congress in 1863 with its capital at Fort Whipple, before it was moved the following year to Prescott. While laying claim to the area, the Confederates made no move to enforce that claim, while one of the reasons for the establishment of Fort McDowell was to support the North's possession of the territory. However, since the Phoenix area had no military value, it was not contested ground during the war.

The founding of Phoenix

In 1863 the mining community ofWickenburg

Wickenburg is a town in Maricopa and Yavapai counties, Arizona, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the town was 7,474, up from 6,363 in 2010.

History

The Wickenburg area, along with much of the Southwest, became part of ...

was the first to be established in what is now Maricopa County

Maricopa County is in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, the population was 4,420,568, making it the state's most populous county, and the fourth-most populous in the United States. It contains about ...

, to the north-west of modern Phoenix. At the time Maricopa County had not yet been incorporated: the land was within Yavapai County

Yavapai County is near the center of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, its population was 236,209, making it the fourth-most populous county in Arizona. The county seat is Prescott.

Yavapai County comprises the Prescott, AZ M ...

, which included the major town of Prescott to the north of Wickenburg.

Verde River

The Verde River (Yavapai: Haka'he:la) is a major tributary of the Salt River in the U.S. state of Arizona. It is about long and carries a mean flow of at its mouth. It is one of the largest perennial streams in Arizona.

Description

The ri ...

in 1865 to quell Native American uprisings. In order to create a supply of hay for their needs, the fort established a camp on the south side of the Salt River in 1866, which was the first non-native settlement in the valley. In later years, other nearby settlements would form and merge to become the city of Tempe, but this community was incorporated after Phoenix.

The history of the city begins with Jack Swilling

John W. "Jack" Swilling (April 1, 1830 – August 12, 1878) was an early pioneer in the Arizona Territory. He is commonly credited as one of the original founders of the city of Phoenix, Arizona. Swilling also played an important role in the ...

, a Confederate veteran who in November, 1867 on a visit to the Fort's camp was the first to appreciate the agricultural potential of the Salt River Valley. He promoted the first irrigation system, which was in part inspired by the ruins of Hohokam canals. Returning to Wickenburg, he raised funds from local gold miners and formed the Swilling Irrigating and Canal Company, whose intent was to build irrigation canals and develop the Salt River Valley for farming. The next month, December, Swilling led a group of 17 miners back to the valley, where they began the process of building the canals which would revitalize the area. There is no concrete evidence on who came up with the name for the new community, but anecdotal stories give credit to Darrell Duppa

Phillip Darrell Duppa (October 9, 1832 – January 30, 1892) was a pioneer in the settlement of Arizona prior to its statehood.

Life

Duppa, who called himself Lord Darrell Duppa, was born in Paris, France, in 1832. He attended Cambridge Universit ...

, who suggested they name it Phoenix. Swilling had suggested "Stonewall", after Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

, and another proposed name was Salina, which had been an early name for the Salt River. However, in light of the rebirth of a town after the collapse of the Hohokam civilization, the name Phoenix predominated. A letter to a newspaper in Prescott, shows that this name was already in use by January 1868.

On February 14, 1871, following a vote by the territorial legislature, Governor Anson P.K. Safford issued a proclamation creating Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County. In that same proclamation, he named Phoenix the county seat, but that nomination was subject to the approval of the voters. An election was held in May, 1871, at which Phoenix' selection as the county seat was ratified. Quite a few members of SRVTA were also elected to county positions: among them were John Alsap (Probate Judge), William Hancock (Surveyor) and Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff. Barnum ran unopposed as the other two candidates had a shootout that left one dead and the other withdrawing from the race. The town's first government consisted of three commissioners.

Several lots of land were sold in 1870 at an average price of $48. The first church opened in 1871, as did the first store. The first public school class was held on September 5, 1872, in the courtroom of the county building. By October 1873, a small school was completed on Center Street (now Central Avenue). The total value of the Phoenix Townsite was $550, with downtown lots selling for between $7 and $11 each.

By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, sixteen saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government was no longer working well. At a mass meeting on Oct. 20, 1875, an election was held to select three village trustees and other officials. Those first three trustees were John Smith (Chairman), Charles W. Stearns (treasurer), and Capt. Hancock (secretary). 1878 saw the opening of the first bank, a branch of the Bank of Arizona, and by 1880, Phoenix's population stood at 2,453. Later in 1880 the first legal hanging in Maricopa County was held, performed in town.

On February 14, 1871, following a vote by the territorial legislature, Governor Anson P.K. Safford issued a proclamation creating Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County. In that same proclamation, he named Phoenix the county seat, but that nomination was subject to the approval of the voters. An election was held in May, 1871, at which Phoenix' selection as the county seat was ratified. Quite a few members of SRVTA were also elected to county positions: among them were John Alsap (Probate Judge), William Hancock (Surveyor) and Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff. Barnum ran unopposed as the other two candidates had a shootout that left one dead and the other withdrawing from the race. The town's first government consisted of three commissioners.

Several lots of land were sold in 1870 at an average price of $48. The first church opened in 1871, as did the first store. The first public school class was held on September 5, 1872, in the courtroom of the county building. By October 1873, a small school was completed on Center Street (now Central Avenue). The total value of the Phoenix Townsite was $550, with downtown lots selling for between $7 and $11 each.

By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, sixteen saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government was no longer working well. At a mass meeting on Oct. 20, 1875, an election was held to select three village trustees and other officials. Those first three trustees were John Smith (Chairman), Charles W. Stearns (treasurer), and Capt. Hancock (secretary). 1878 saw the opening of the first bank, a branch of the Bank of Arizona, and by 1880, Phoenix's population stood at 2,453. Later in 1880 the first legal hanging in Maricopa County was held, performed in town.

Incorporation (1881)

By 1881, Phoenix' continued growth made the existing village structure with a board of trustees obsolete. The 11th Territorial Legislature passed "The Phoenix Charter Bill", incorporating Phoenix and providing for a mayor-council government. The bill was signed by Governor John C. Fremont on February 25, 1881, officially incorporating Phoenix with a population of approximately 2,500. On May 3, 1881, Phoenix held its first city election. Judge John T. Alsap defeated

By 1881, Phoenix' continued growth made the existing village structure with a board of trustees obsolete. The 11th Territorial Legislature passed "The Phoenix Charter Bill", incorporating Phoenix and providing for a mayor-council government. The bill was signed by Governor John C. Fremont on February 25, 1881, officially incorporating Phoenix with a population of approximately 2,500. On May 3, 1881, Phoenix held its first city election. Judge John T. Alsap defeated James D. Monihon

James D. Monihon (November 6, 1837September 2, 1904) was an American businessman and politician. He was a signatory to the formation of the Salt River Valley Town Association, the first government of the area that became Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix ...

, 127 to 107, to become the city's first mayor.

As the city developed, so did its infrastructure and services, usually in response to a recent crisis or event. The public health department was created in the early 1880s after several smallpox outbreaks. This was followed by the establishment of a volunteer fire department after two serious fires in the city, which in turn led to the development of a public water system, begun in 1887. Other services which would see their beginnings in this decade were a private gas lighting company (1886), telephone company (1886), a mule-drawn streetcar system (1887), and electric power (1888).

The coming of the railroad in the 1880s was the first of several important events that revolutionized the economy of Phoenix. A spur of the

The coming of the railroad in the 1880s was the first of several important events that revolutionized the economy of Phoenix. A spur of the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

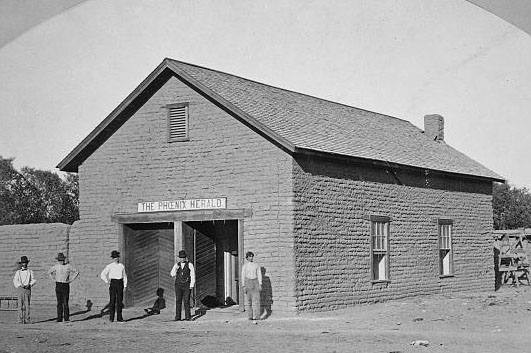

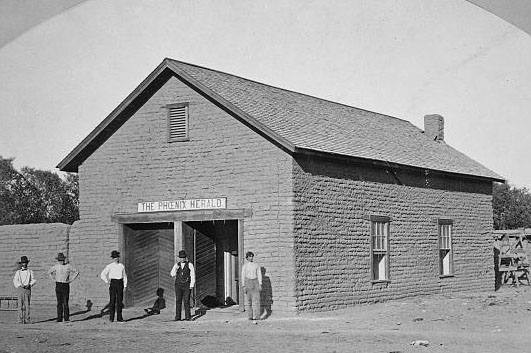

, the Phoenix and Maricopa, was extended from Maricopa into Tempe in 1887. Merchandise now flowed into the city by rail instead of wagon. Phoenix became a trade center, with its products reaching eastern and western markets. In response, the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce was organized on November 4, 1888. Earlier in 1888 the city offices were moved into the new City Hall, at Washington and Central (later the site of the city bus terminal, until Central Station was built in the 1990s). When the territorial capital was moved from Prescott to Phoenix in 1889 the temporary territorial offices were also located in City Hall.

The ''Arizona Republic

''The Arizona Republic'' is an American daily newspaper published in Phoenix. Circulated throughout Arizona, it is the state's largest newspaper. Since 2000, it has been owned by the Gannett newspaper chain. Copies are sold at $2 daily or at $3 ...

'' became a daily paper in 1890, with Ed Gill as its editor. 1891 was marked by the greatest flood in the Valley's history, and 1892 saw the creation of the Phoenix Sewer and Drainage Department. The Phoenix Street Railway

The Phoenix Street Railway provided streetcar service in Phoenix, Arizona, from 1888 to 1948. The motto was "Ride a Mile and Smile the While."

History

The line was founded in 1887 by Moses Hazeltine Sherman and used horse-drawn carts. The sy ...

electrified its mule-drawn streetcar lines in 1893, with streetcar service continuing until a 1947 fire. Another important event which occurred in 1893 was the passage of a territorial law which allowed Phoenix to annex land surrounding the city, as long as it obtained the permission of the inhabitants of that area. This would begin a process which lasts till today, as the city annexed some surrounding terrain, growing from its original 0.5 square miles of territory to slightly over 2 square miles of territory by the turn of the century. On March 12, 1895, the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway

The Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway (SFP&P) was a common carrier railroad that later became an operating subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in Arizona. At Ash Fork, Arizona, the SFP&P connected with Santa Fe's ope ...

ran its first train to Phoenix, connecting it to the northern part of Arizona. The additional railroad sped the capital city's economic rise. The year 1895 also saw the establishment of Phoenix Union High School

Phoenix Union High School (PUHS) was a high school that was part of the Phoenix Union High School District in downtown Phoenix, Arizona, one of five high school-only school districts in the Phoenix area. Founded in 1895 and closed in 1992, the ...

, with an enrollment of 90.

From 1900 to 1940

By the turn of the century, the population of Phoenix had reached 5,554, and the following year, on February 25, 1901, Governor Murphy dedicated the permanent state Capitol building. It was built on a 10-acre site on the west end of Washington Street, at a cost of $130,000. The Phoenix City Council levied a $5,000,000 tax for a public library after the state legislature, in 1901, passed a bill allowing such a tax to support free libraries. This action satisfied the conditions set byAndrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

in his proposal to donate a library building to the city. The Carnegie Free Library opened in 1908, dedicated by Benjamin Fowler.

The Phoenix weather was a major attraction for tuberculosis patients at a time when the only cure for the widespread, fatal lung disease was rest in a dry, warm climate. The Roman Catholic order of the Sisters of Mercy

The Sisters of Mercy is a religious institute of Catholic women founded in 1831 in Dublin, Ireland, by Catherine McAuley. As of 2019, the institute had about 6200 sisters worldwide, organized into a number of independent congregations. They a ...

opened St. Joseph's Hospital in 1895, with 24 private rooms for tuberculosis patients. Although the Catholic population was small and poor, the city's Protestants were generous and funding a new hospital. In 1910 the sisters opened Arizona's first school of nursing. Today St. Joseph's Hospital is part of a corporation called Dignity Health, and is still operated by the Sisters of Mercy. Until 1901, the sisters also ran Sacred Heart Academy, an elite school for young ladies. The Sisters of the Precious Blood opened St. Mary's Catholic High School in 1917. Brophy College Preparatory

Brophy College Preparatory is a Jesuit high school in Phoenix, Arizona, United States. The school has an all-male enrollment of approximately 1,400 students. It is operated independently of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Phoenix.

The school has ...

for boys was opened in 1928 by the Jesuits.

In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

signed the National Reclamation Act

The Reclamation Act (also known as the Lowlands Reclamation Act or National Reclamation Act) of 1902 () is a United States federal law that funded irrigation projects for the arid lands of 20 states in the American West.

The act at first covere ...

, allowing for dams to be built on western streams for reclamation purposes. Residents were quick to enhance this by organizing the Salt River Valley Water Users' Association (on February 7, 1903), to manage the water and power supply. The agency still exists as part of the Salt River Project

The Salt River Project (SRP) is the umbrella name for two separate entities: the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District, an agency of the state of Arizona that serves as an electrical utility for the Phoenix metropolitan a ...

. Theodore Roosevelt Dam

Theodore Roosevelt Dam is a dam on the Salt River located northeast of Phoenix, Arizona. The dam is high and forms Theodore Roosevelt Lake as it impounds the Salt River. Originally built between 1905 and 1911, the dam was renovated and expande ...

was started in 1906. It was the first multiple-purpose dam, supplying both water and electric power, to be constructed under the National Reclamation Act. On May 18, 1911, the former president himself dedicated the dam, which was the largest masonry dam in the world, forming several new lakes in the surrounding mountain ranges.

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, Phoenix became the capital of the newly formed state of Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

. This occurred just six months after Taft had vetoed, on August 11, 1911, a joint resolution giving Arizona statehood. Taft disapproved of the recall of judges in the state constitution. Compared to Tucson or Prescott, Phoenix was considered preferable as the capital because of its central location. It was smaller than Tucson, but outgrew that city within the next few decades, to become the state's largest city.

In 1913 Phoenix adopted a new form of government, changing from a mayor-council system to council-manager, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate, and by the end of its first eight years under statehood, Phoenix' population had grown to 29,053. Two thousand were attending Phoenix Union High School. In 1920 Phoenix built its first skyscraper, the Heard Building. In 1928

In 1913 Phoenix adopted a new form of government, changing from a mayor-council system to council-manager, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate, and by the end of its first eight years under statehood, Phoenix' population had grown to 29,053. Two thousand were attending Phoenix Union High School. In 1920 Phoenix built its first skyscraper, the Heard Building. In 1928 Scenic Airways

Grand Canyon Airlines is a 14 CFR Part 135 air carrier headquartered on the grounds of Boulder City Municipal Airport in Boulder City, Nevada, United States. It also has bases at Grand Canyon National Park Airport and Page Municipal Airport, bot ...

, Inc. saw profitability in flights in the Southwest. Scenic General Manager, J. Parker Van Zandt purchased land for Scenic in Phoenix, and named the new airport Sky Harbor, which was formally dedicated on Labor Day in 1929.

On March 4, 1930, Former President Calvin Coolidge dedicated a dam on the Gila River named in his honor. Because of a long drought the "lake" behind it held no water. Humorist Will Rogers, also a guest speaker, quipped, "If that was my lake I’d mow it." Phoenix's population had more than doubled during the 1920s, and now stood at 48,118.

After the stock market crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

, Sky Harbor was sold to another investor, and in 1930 American Airlines

American Airlines is a major airlines of the United States, major US-based airline headquartered in Fort Worth, Texas, within the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex. It is the Largest airlines in the world, largest airline in the world when measured ...

brought passenger and air mail service to Phoenix. In 1935 the city of Phoenix purchased the single runway airport, nicknamed "The Farm" due to its isolation, and it has been owned and operated by the city to this day. During the 1930s couples used to fly into Sky Harbor solely to get married at the chapel, for Arizona was one of the few states that did not have a waiting period for marriage. It was also during the 1930s that Phoenix and its surrounding area began to be called "The Valley of the Sun", which was an advertising slogan invented to boost tourism.

In 1940 as the Depression ended, Phoenix had a population of 65,000 (with 121,000 more in the remainder of Maricopa County

Maricopa County is in the south-central part of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, the population was 4,420,568, making it the state's most populous county, and the fourth-most populous in the United States. It contains about ...

). Its economy was still based on cotton, citrus and cattle, while it also provided retail, wholesale, banking, and governmental services for central Arizona, and was gaining a national reputation among winter tourists.

1940s

World War II

During World War II, Phoenix's economy shifted to that of a distribution center, rapidly turning into an embryonic industrial city with mass production of military supplies. There were 3 Air Force fields in the area: Luke Field,Williams Field

Williams Field or Willy Field is a United States Antarctic Program airfield in Antarctica. Williams Field consists of two snow runways located on approximately 8 meters (25 ft) of compacted snow, lying on top of 8–10 ft of ice, flo ...

, and Falcon Field, as well as two large pilot training camps, Thunderbird Field No. 1 in Glendale and Thunderbird Field No. 2 in Scottsdale. These facilities, coupled with the giant Desert Training Center

The Desert Training Center (DTC), also known as California–Arizona Maneuver Area (CAMA), was a World War II training facility established in the Mojave Desert and Sonoran Desert, largely in Southern California and Western Arizona in 1942.

It ...

created by General George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

west of Phoenix, brought thousands of new people into Phoenix.

Mexican-American local organizations enthusiastically supported the war effort, providing encouragement for the large number of men who enlisted, and assistance for their families. Many civilians were employed in the war effort, bringing the community more money than ever before. Some projects were organized in cooperation with the dominant Anglo community, but most were operated separately. Numerous postwar politicians got their start during the war on the home front, or from their experiences and contacts in the military. The postwar G.I. Bill of Rights provided mortgage funding for home ownership, allowing thousands to move out of small apartments.

On Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden and ...

night 1942, a brawl at a bar led to MP's arresting a black soldier, followed by a riot of black troops from segregated units. Three men died and eleven were wounded in the riot. Most of the 180 men arrested and jailed were released, but some were court-martialed and sent to military prison.

German prisoners of war built a secret tunnel at the prisoner-of-war camp which was located at the present site of Papago Park

Papago Park () is a municipal park of the cities of Phoenix and Tempe, Arizona, United States. It has been designated as a Phoenix Point of Pride.

It includes Hunt's Tomb, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Description

...

. In the Great Papago Escape

The Great Papago Escape was the largest Axis prisoner-of-war escape to occur from an American facility during World War II. On the night of December 23, 1944, twenty-five Germans tunneled out of Camp Papago Park, near Phoenix, Arizona, and fled ...

of 23 December 1944, 25 POW's escaped. Local and federal officials took a month to recapture them all.

During the war, public transportation was overwhelmed by the newcomers at a time when gasoline was rationed to 3 gallons a week and no new autos were built. In 1943, the transit systems operated seventeen streetcars and fifty-five buses. They carried 20,000,000 passengers a year. A fire in 1947 destroyed most of the streetcars, and the city switched to buses.

Postwar growth

A town that had just over sixty-five thousand residents in 1940 became America's sixth largest city by 2010, with a population of nearly 1.5 million, and millions more in nearby suburbs. The postwar boom was based on the arrival of young veterans who had seen enough of the city to realize its potential, and new industries. Large industry, learning of this labor pool, started to move branches here. In 1948 high-tech industry, which would become a staple of the state's economy, arrived in Phoenix whenMotorola

Motorola, Inc. () was an American multinational telecommunications company based in Schaumburg, Illinois, United States. After having lost $4.3 billion from 2007 to 2009, the company split into two independent public companies, Motorol ...

chose Phoenix for the site of its new research and development center for military electronics. Motorola was attracted by the city's business-friendly attitude, its location within reasonable distance of supply houses in New Mexico and southern California, the potential for engineering programs at Arizona State College (now Arizona State University

Arizona State University (Arizona State or ASU) is a public research university in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, ASU is one of the largest public universities by enrollment in the ...

), and the climate. In time, other high-tech companies such as Intel

Intel Corporation is an American multinational corporation and technology company headquartered in Santa Clara, California. It is the world's largest semiconductor chip manufacturer by revenue, and is one of the developers of the x86 seri ...

and McDonnell Douglas

McDonnell Douglas was a major American aerospace manufacturing corporation and defense contractor, formed by the merger of McDonnell Aircraft and the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1967. Between then and its own merger with Boeing in 1997, it pro ...

would follow Motorola's lead and set up manufacturing operations in the Valley.

Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater (1909–1998) was one of the city's most prominent local, statewide and national leaders. He is known for owning the city's largest department store, working to reform city government, building and leading the state Republican Party (GOP), gaining a national visibility as a powerful senator, becoming known as "Mr. Conservative" for his articulation of the once unpopularideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

, and running a dramatic presidential campaign in 1964 that lost in a landslide but shifted the GOP permanently to the right. He was born in Phoenix before Arizona became a state, the son of Baron M. Goldwater and his wife, Hattie Josephine ("JoJo") Williams. His father came from a Jewish family that had emigrated from England and founded Goldwater's

Goldwater's Department Store was a department store chain based in Phoenix, Arizona.

History

Michael Goldwater, the grandfather of U.S. Senator and 1964 presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, established a trading post in 1860 in Gila City, A ...

, the largest department store in Phoenix. Goldwater's mother, who was Episcopalian came from an old Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Its various senses depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, residents of the Northern United St ...

family that included the famous theologian, Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

. Goldwater's parents were married in the Episcopal church and Baron broke permanently from the Jewish community. For his entire life, Goldwater was an Episcopalian, but the national media identified him as the first Jewish candidate for president, He took over the family business in 1930. In a heavily Democratic state Goldwater became a conservative Republican and a friend of Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

. He was outspoken against New Deal liberalism

Modern liberalism in the United States, often simply referred to in the United States as liberalism, is a form of social liberalism found in American politics. It combines ideas of civil liberty and equality with support for social justice and ...

, especially its close ties to labor unions that he considered corrupt. Phoenix schools were segregated and the atmosphere was Southern; Goldwater quietly supported civil rights for blacks, but would not let his name be used. A pilot, outdoorsman and photographer, he developed a deep interest in both the natural history and the human history of Arizona. He entered Phoenix politics in 1949 when he was elected to the City Council as part of a nonpartisan team of candidates who promised to clean up widespread prostitution and gambling. The group won every mayoral and council election for two decades. Goldwater rebuilt the weak Republican party and won election to the U.S. Senate in 1952, defeating the Senate Majority Leader Ernest McFarland

Ernest William McFarland (October 9, 1894 – June 8, 1984) was an American politician, jurist and, with Warren Atherton, one of the "Fathers of the G.I. Bill." He is the only Arizonan to serve in the highest office in all three branches of Ari ...

by enough of a lead in the Phoenix area to narrowly overcome Democratic strength in rural Arizona.

Reform of city government

In 1947 a new organization, the Phoenix Charter Revision Committee, began to analyze the administrative instability, factionalism, mediocrity and low morale that had long paralyzed city government. The proposed a series of reforms and reorganized itself as the nonpartisan Charter Government Committee. Goldwater was a leader, and the committee, starting in 1949, swept nearly all the elections in the next two decades. The committee had a broad base that included many civic and business leaders, and made sure that all the city's religions were represented. It had one woman but no blacks or Hispanics.Eugene C. Pulliam

Eugene Collins Pulliam (May 3, 1889 – June 23, 1975) was an American newspaper publisher and businessman who was the founder and president of Central Newspapers Inc., a media holding company. During his sixty-three years as a newspaper publish ...

, owner of the city's major newspaper the ''Arizona Republic,'' provided extensive publicity. Much of the committee's funding secretly came from Gus Greenbaum

Gus Greenbaum (February 26, 1893 – December 3, 1958) was an American gangster in the casino industry, best known for taking over management of the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas after the murder of co-founder Bugsy Siegel.

Early life

Gustave ...

, an associate of organized crime figures, despite the committee's vehement public denunciation of crime and corruption. The newly invigorated city council introduced a more efficient, less corrupt system based on a professional city manager. While the committee could win all its elections, it was defeated on one major policy issue when a different grassroots group warned against urban renewal proposals, saying they were socialistic and threatened the rights of private property owners.

The 1950s

Population and industrial growth

The city grew explosively in the 1950s; the population expanded by a factor of three, and industry by a factor of fifteen. The growth brought serious problems of minority housing, traffic congestion, smog, and a fading of the traditional laid-back Phoenix lifestyle. By 1950, over 105,000 people lived within the city and thousands more in surrounding communities. There were 148 miles (238 km) of paved streets and 163 miles (262 km) of unpaved streets. The 1950s growth was spurred on by advances in mechanical air conditioning, which allowed both homes and businesses to offset the extreme heat known to Phoenix during its long summers. Affordable cooling in the decade contributed to a wild building boom. In 1959 alone, Phoenix saw more new construction than it had in the more than three decades from 1914 to 1946. In May 1953, Phoenix became the location of the very first franchise of the McDonald's restaurant chain. The restaurant was located near the southwest corner of Central Avenue and Indian School Road. In addition to being the first McDonald's franchise, the Phoenix location was also the first McDonald's restaurant to feature the "Golden Arches" which would become the emblematic architectural element of the global restaurant chain. The McDonald brothers, Richard and Maurice, desiring to expand the successful restaurant they had created in San Bernardino, California licensed the first McDonald's franchise to Phoenix businessman, Neil Fox and two other partners for a licensing fee of $1,000.00.Political transformation

Arizona moved from a Democratic stronghold in the 1930s to a Republican bastion by the 1960s, with Phoenix leading the way. The Democrats lost the 5 to 1 advantage in voter registration they held at war's end to one of equal balance by 1970. Pearce sees multiple reasons for the transition, especially the demographic change that brought in Midwesterners with a Republican heritage. The new industries were based on high technology, and attracted engineers and technicians who voted Republican and showed little interest in labor unions, as opposed to the heavily Democratic semiskilled workers in eastern factories. The retirees were mostly Republican as well. A second factor was a favorable media climate, especially from the ''Arizona Republic'' and ''Phoenix Gazette'' newspapers and their television stations, owned by Eugene Pulliam. After 1964 however the Pulliam media were politically better balanced. Finally, Pearce points to the quality of Republican candidates that Goldwater had systematically recruited from among the affluent, well-educated new arrivals from the East. They attracted votes across party lines, as did Goldwater himself, as well as GovernorHoward Pyle

Howard Pyle (March 5, 1853 – November 9, 1911) was an American illustrator and author, primarily of books for young people. He was a native of Wilmington, Delaware, and he spent the last year of his life in Florence, Italy.

In 1894, he began ...

, Congressman John Rhodes and numerous others. Pearce, however, also notes a growing right-wing element, based in Phoenix, that repeatedly challenged the business-oriented Republican establishment.

1960s to 1980s

Over the next several decades, the city and metropolitan area attracted more growth and became a favored tourist destination for its exotic desert setting and recreational opportunities. Nightlife and civic events concentrated along now skyscraper-flanked Central Avenue. In 1960 thePhoenix Corporate Center

The Phoenix Corporate Tower (formerly known as First Federal Savings Building) is a 26-story high-rise office building in Phoenix, Arizona. It was built in 1965 and designed in the International Style. The tower was built two miles north of Down ...

opened; at the time it was the tallest building in Arizona, topping off at 341 feet. 1964 saw the completion of the Rozenweig Center, today called Phoenix City Square

Phoenix City Square, formerly Kent Plaza and the Rosenzweig Center, is a mixed use high rise complex covering 15 acres at 3800-4000 N. Central Ave. in Phoenix, Arizona. The project was developed by the Del Webb Corporation in 1962. The complex fea ...

. Architect Wenceslaus Sarmiento's largest project, the landmark Phoenix Financial Center

The Phoenix Financial Center consists of a high-rise office building and two adjacent rotunda buildings located along Central Avenue in the Midtown district of Phoenix, Arizona, United States. They were built in 1963 by the Financial Corporati ...

(better known by locals as the "Punch-card Building" in recognition of its unique southeastern facade), was also finished in 1964. In addition to a number of other office towers, many of Phoenix's residential high-rises were built during this decade.

As in many emerging American cities at the time, Phoenix's spectacular growth did not occur evenly. It largely took place on the city's north side, a space that was nearly all white. In 1962, one local activist testified at a US Commission on Civil Rights hearing that of 31,000 homes that had recently sprung up in this neighborhood, not a single one had been sold to an African-American. Phoenix's African-American and Mexican-American communities remained largely sequestered on the town's south side. The color lines were so rigid that no one north of Van Buren Street would rent to the African-American baseball star Willie Mays, in town for spring training in the 1960s. In 1964, a reporter from the ''New Republic'' wrote of segregation in these terms: "Apartheid is complete. The two cities look at each other across a golf course."

In 1965, the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum

Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum is a 14,870-seat multi-purpose indoor arena in Phoenix, Arizona, located at the Arizona State Fairgrounds. It hosted the Phoenix Suns of the National Basketball Association from 1968 to 1992, as well as indoor s ...

opened on the grounds of the Arizona State Fair

The Arizona State Fair is an annual state fair, held at Arizona State Fairgrounds.

It was first held in 1884, but has had various interruptions due to cotton crop failure, the Great Depression era, World War I & World War II years & the COVID-1 ...

, west of downtown, and in 1968, the city was surprisingly awarded the Phoenix Suns NBA

The National Basketball Association (NBA) is a professional basketball league in North America. The league is composed of 30 teams (29 in the United States and 1 in Canada) and is one of the major professional sports leagues in the United St ...

franchise, which played its home games at the Coliseum until 1992. In 1968, the Central Arizona Project was approved by President Lyndon B. Johnson, assuring future water supplies for Phoenix, Tucson, and the agricultural corridor in between. In 1969 Catholic church created the Diocese of Phoenix on December 2, by splitting the Archdiocese of Tucson. The first bishop was the Most Reverend Edward A. McCarthy, who had become a Bishop in 1965.

In 1971, Phoenix adopted the Central Phoenix Plan, allowing unlimited building heights along Central Avenue, but the plan did not sustain long-term development of the " Central Corridor." While a few office towers were constructed along North Central during the 1970s, none approached the scope of construction during the previous decade. Instead, the downtown area experienced a resurgence, with a level of construction activity not seen again until the urban real estate boom of the 2000s, when several high rise buildings were erected, including the buildings currently named Wells Fargo Plaza, the Chase Tower (at 483 feet, the tallest building in both Phoenix and Arizona) and the U.S.Bank Center. By the end of the decade, Phoenix adopted the Phoenix Concept 2000 plan which split the city into urban villages, each with its own village core where greater height and density was permitted, further shaping the free-market development culture (see Cityscape

In the visual arts, a cityscape (urban landscape) is an artistic representation, such as a painting, drawing, Publishing, print or photograph, of the physical aspects of a city or urban area. It is the urban equivalent of a landscape. ''Town ...

, below). This officially turned Phoenix into a city of many nodes, which would later be connected by freeways. 1972 would see the opening of the Phoenix Symphony Hall

Symphony Hall is a multi-purpose performing arts venue, located at 75 North 2nd Street between North 3rd Street and East Washington Street in downtown Phoenix, Arizona. Part of Phoenix Civic Plaza, the hall is bounded to the north by the West B ...

,

After the Salt River flooded in 1980 and damaged many bridges, the Arizona Department of Transportation

The Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT, pronounced "A-Dot") is an Arizona state government agency charged with facilitating mobility within the state. In addition to managing the state's state highways, highway system, the agency is also i ...

and Amtrak

The National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Trade name, doing business as Amtrak () , is the national Passenger train, passenger railroad company of the United States. It operates inter-city rail service in 46 of the 48 contiguous United Stat ...

worked together and temporarily operated a train service, referred to by the Valley Metro Rail

Valley Metro Rail (styled as METRO) is a light rail line serving the cities of Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa in Arizona, USA. The network, which is part of the Valley Metro public transit system, began operations on December 27, 2008. In , the sys ...

as the "Hattie B." line, between central Phoenix and the southeast suburbs. It was discontinued because of high operating costs and a lack of interest from local authorities in maintaining funding. Nominated by President Reagan, on September 25, 1981, Sandra Day O'Connor

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26, 1930) is an American retired attorney and politician who served as the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. She was both the first woman nominated and th ...

broke the gender barrier on the U.S. Supreme Court, when she was sworn in as the first female justice. 1985 saw the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station

The Palo Verde Generating Station is a nuclear power plant located near Tonopah, Arizona, in western Arizona. It is located about due west of downtown Phoenix, Arizona, and it is located near the Gila River, which is dry save for the rainy seaso ...

, the nation's largest nuclear power plant, begin electrical production. Conceived in 1980, the Arizona Science Center, located in ''Heritage and Science Park'', opened in 1984. 1987 saw visits by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

and Mother Teresa

Mary Teresa Bojaxhiu, MC (; 26 August 1910 – 5 September 1997), better known as Mother Teresa ( sq, Nënë Tereza), was an Indian-Albanian Catholic nun who, in 1950, founded the Missionaries of Charity. Anjezë Gonxhe Bojaxhiu () was ...

.

1990-present

The new 20 story

The new 20 story City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

opened in 1992, The development of the Sunnyslope area with low-cost housing is noticed by local refugee resettlement centers, which promote the area among refugee communities. During the 1990s, refugees from Afghanistan, Bosnia, the Sudan, Somalia, Congo, Sierra Leone, Laos, Vietnam, and Central and South America would settle there. 43 different languages would be spoken in local schools by the year 2000. Valley National, with $11 billion in assets, was the biggest bank in Arizona, and one of the oldest, when it was bought out by Banc One Corp. of Columbus, Ohio, in 1992. The sale for $1.2 billion was part of the trend toward outside ownership of the state's banking assets. 1993 saw the creation of "Tent City

A tent city is a temporary housing facility made using tents or other temporary structures.

State governments or military organizations set up tent cities to house evacuees, refugees, or soldiers. UNICEF's Supply Division supplies expandable te ...

," by Sheriff Joe Arpaio

Joseph Michael Arpaio (; born June 14, 1932) is an American former law enforcement officer and politician. He served as the 36th Sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona for 24 years, from 1993 to 2017, losing reelection to Democrat Paul Penzone i ...

, using inmate labor, to alleviate overcrowding in the Maricopa County Jail system, the fourth-largest in the world. The famous "Phoenix Lights

The Phoenix Lights (sometimes called the "Lights Over Phoenix") were a series of widely sighted unidentified flying objects observed in the skies over the southwestern states of Arizona and Nevada on March 13, 1997.

Lights of varying descript ...

" UFO

An unidentified flying object (UFO), more recently renamed by US officials as a UAP (unidentified aerial phenomenon), is any perceived aerial phenomenon that cannot be immediately identified or explained. On investigation, most UFOs are id ...