History Of Norfolk, Virginia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Norfolk, Virginia as a modern settlement begins in 1636. The city was named after the English county of Norfolk and was formally incorporated in 1736. The city was burned by orders of the outgoing

Norfolk had been a strong base of

Norfolk had been a strong base of

By 1870, the end of

By 1870, the end of  In 1883, the first car of

In 1883, the first car of

Norfolk continued to grow in the first half of the 20th century as it expanded its borders through annexation. In 1906, the

Norfolk continued to grow in the first half of the 20th century as it expanded its borders through annexation. In 1906, the

With the dawn of the

With the dawn of the

Another focus was the waterfront and its decaying piers and warehouses. Norfolk, using Federal urban renewal funds, began large-scale demolitions downtown. This included slum housing that, in the mid-20th century, did not have indoor plumbing or access to running water. The former City Market,

Another focus was the waterfront and its decaying piers and warehouses. Norfolk, using Federal urban renewal funds, began large-scale demolitions downtown. This included slum housing that, in the mid-20th century, did not have indoor plumbing or access to running water. The former City Market,

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

The title Earl of Dunmore was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. The title passed down through generations, with various earls serving ...

in 1776 during the second year of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

(1775–1783), although it was soon rebuilt.

The 19th century proved to be a time of numerous travails for both the city of Norfolk, and the region as whole. War, epidemics, fires, and economic depression reduced the development of the city. The city grew into the region's economic hub. By the late 19th century, the Norfolk and Western Railway

The Norfolk and Western Railway , commonly called the N&W, was a US class I railroad, formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It was headquartered in Roanoke, Virginia, for most of its existence. Its motto was "Precisio ...

with its line to the west established the community as a major coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

ore exporting port and built a large trans-loading facility at Lambert's Point

Lambert's Point is a point of land on the east shore of the Elizabeth River near the downtown area of the independent city of Norfolk in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia, United States. It includes a large coal exporting faci ...

. It became the terminus for numerous other railroads, linking its ports to inland regions of Virginia and North Carolina, and at the turn of the 20th century, the coal mining regions of Appalachia

Appalachia ( ) is a geographic region located in the Appalachian Mountains#Regions, central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains in the east of North America. In the north, its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountai ...

were well connected to the port on the East Coast. Princess Anne

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950) is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of King ...

and Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

counties would become leaders in truck farming, producing over half of all greens and potatoes consumed on the East Coast. Lynnhaven oysters also became a major export.

The region's African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

achieved full emancipation following the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

(1861–1865), after the initial Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

by 16th President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

in 1862–1863, supplemented later by the three post-war constitutional amendments

A constitutional amendment (or constitutional alteration) is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly alt ...

during the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

(1865–1877), only to be faced with severe discrimination through white legislators' later imposition by the 1890s of Jim Crow Laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

. After Virginia passed a new post-war state constitution, African Americans were essentially disfranchised for more than 60 years until their leadership and activism won passage of federal civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s.

In 1907, it was host to the Jamestown Exposition commemorating the tercennary (300th anniversary) of the first English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

settlement at Jamestown on the James River

The James River is a river in Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows from the confluence of the Cowpasture and Jackson Rivers in Botetourt County U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowli ...

, the only world's fair to ever be held in Virginia. As a result of its publicity and visits by high-ranking officials during the exposition (in which the Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the group of United States Navy battleships that completed a journey around the globe from 16 December 1907, to 22 February 1909, by order of President Foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt ...

, of 26th President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

with the rebuilt United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

after the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

of 1898 was launched from Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond, and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point near whe ...

harbor), it became the later location of the Norfolk Naval Station

Naval Station Norfolk is a United States Navy base in Norfolk, Virginia, that is the headquarters and home port of the U.S. Navy's Fleet Forces Command. The installation occupies about of waterfront space and of pier and wharf space of the Ha ...

.

Today, the city of Norfolk is a major American naval and world shipping hub, as well as the center of the Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond, and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point near whe ...

region, both on the southside and the peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

to the north of the extensive harbor between the James

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

and York Rivers, with the railroad terminus and ship construction port of Newport News

Newport News () is an independent city in southeastern Virginia, United States. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the fifth-most populous city in Virginia and 140th-most populous city i ...

from the 19th century on the west shore and Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

* Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

* Hampton, Victoria

** Hampton railway station, Melbour ...

on the south and east sides, dating back to its founding in the colonial era as Virginia's original port.

Pre-colonial

The first evidence of humans inhabiting Virginia is from 9,500 BC. In 1584, SirWalter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

led an expedition in search of a suitable place to establish a permanent English settlement in North America. By mid-July of that year, two of his ships had landed on Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of English colonizat ...

(now a part of Dare County

Dare County is the easternmost County (United States), county in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 36,915. Its county seat is Manteo, North Carolina, Manteo.

Dare County is i ...

). Arthur Barlowe

Arthur Barlowe (1550–1620) was one of two English captains (the other was Philip Amadas) who, under the direction of Sir Walter Raleigh, left England in 1584 to find land in North America to claim for Queen Elizabeth I of England. His account ...

, one of Raleigh's commanders, kept a journal which states the area was inhabited by a tribe of Native Americans called the Chesepian

The Chesepian (Chesapeake) were a Native American tribe who lived near present-day South Hampton Roads in the U.S. state of Virginia. They occupied an area which is now in the independent cities of Norfolk and Virginia Beach (formerly Norfolk Cou ...

. According to Barlowe, the local Chesepians claimed that a nearby city called Skicoak was the Chesepians' greatest city. However, the exact location of ''Skicoak'' has remained undetermined.

When Jamestown settlers arrived at Cape Henry

Cape Henry is a cape on the Atlantic shore of Virginia located in the northeast corner of Virginia Beach. It is the southern boundary of the entrance to the long estuary of the Chesapeake Bay.

Across the mouth of the bay to the north is Cape Ch ...

(in present-day Virginia Beach) almost 23 years later in April 1607, they found no traces of ''Skicoak''. According to William Strachey

William Strachey (4 April 1572 – buried 16 August 1621) was an English writer whose works are among the primary sources for the early history of the English colonisation of North America. He is best remembered today as the eye-witness reporter ...

's ''The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britanica'' (1612), the Chesepians had been wiped out by Chief Wahunsunacock

Powhatan (), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh (alternately spelled Wahunsenacah, Wahunsunacock, or Wahunsonacock), was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommacah, in the Tidewater ...

(better known as Chief Powhatan

Powhatan (), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh (alternately spelled Wahunsenacah, Wahunsunacock, or Wahunsonacock), was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommacah, in the Tidewat ...

), the head of the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is the natural landform located in southeast Virginia outlined by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other penins ...

-based Powhatan Confederacy

Powhatan people () are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Their Powha ...

in the intervening years.

Colonial period (1607–1775)

In 1607, the Governor for the Virginia Colony, Sir George Yeardley established four incorporations, termed "citties" for the developed portion of the colony. These citties were to form the basis for the government of the colony in the newly createdHouse of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses () was the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly from 1619 to 1776. It existed during the colonial history of the United States in the Colony of Virginia in what was then British America. From 1642 to 1776, the Hou ...

, with the southeastern portion of the Hampton Roads region falling under the Elizabeth Cittie Elizabeth City (or Elizabeth Cittie as it was then called) was one of four incorporations established in the Virginia Colony in 1619 by the proprietor, the Virginia Company of London, acting in accordance with instructions issued by Sir George Year ...

incorporation. In 1622, Adam Thoroughgood

Adam Thoroughgood horowgood'' (1604–1640) was a colonist and community leader in the Virginia Colony who helped settle the Virginia counties of Elizabeth City, Lower Norfolk and Princess Anne, the latter, known today as the independent city of ...

(1604–1640) of King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is north-east of Peterborough, north-north-east of Cambridg ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

, England, became one of the earliest Englishmen to settle in the area that was to become South Hampton Roads

South Hampton Roads is a region located in the extreme southeastern portion of Virginia's Tidewater region in the United States with a total population of 1,177,742 as of 2020. It is part of the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA ( M ...

, when at the age of 18 he became an indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of Work (human activity), labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as paymen ...

to pay for passage to the Virginia Colony. After his period of contracted servitude was finished, he earned his freedom and soon became a leading citizen of the fledgling colony.

Meanwhile, after years of continuing struggles at Jamestown, the now bankrupt Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the objective of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day ...

had its royal charter revoked by King James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

in 1624 and Virginia became a crown colony. Also at this time, the King granted of land to Thomas Willoughby, in what is now the Ocean View section of the city. The entire population of the Virginia colony was estimated to be 5,000 people at this time.

In 1629, Thoroughgood was elected to the House of Burgesses for Elizabeth Cittie. Five years later, in 1634, the King had the colony reorganized under a system of 8 shires

Shire () is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries. It is generally synonymous with county (such as Cheshire and Worcestershire). British counties are among the oldes ...

, with much of the Hampton Roads region becoming part of Elizabeth City Shire

Elizabeth City Shire was one of eight Shires of Virginia, shires created in Colony of Virginia, colonial Virginia in 1634. The shire and the Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth River were named for Elizabeth of Bohemia, daughter of King James I ...

. In 1636, Thoroughgood was granted a large land holding along the Lynnhaven River for having persuaded 105 people to settle in the colony. Thoroughgood is also credited with suggesting the name of Norfolk, in honor of his birthplace. New Norfolk County

New Norfolk County is a long-extinct county which was located in colonial Virginia from 1636 until 1637.

It was formed in 1636 from Elizabeth City Shire, one of the eight original shires (or counties) formed in 1634 in the colony of Virginia by d ...

was created when the South Hampton Roads portion of Elizabeth City Shire was partitioned off in that same year. Also during this reorganization, King James granted a further to Willoughby. This land would become the city of Norfolk in future. Shortly thereafter, in 1637, New Norfolk County was itself split into two counties, Upper Norfolk County and Lower Norfolk County

Lower Norfolk County is a long-extinct county which was organized in colonial Virginia, operating from 1637 until 1691.

New Norfolk County was formed in 1636 from Elizabeth City Shire, one of the eight original shires (or counties) formed in 1634 ...

. The modern city of Norfolk is located in Lower Norfolk.

In 1649 the English couple William and Susannah Moseley migrated with their family to Lower Norfolk County. On the Eastern Branch Elizabeth River

The Eastern Branch Elizabeth River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 tidal river in the Hampton Roads area of the U.S. state of Virginia. The river fl ...

from Norfolk, they built a manor house with Dutch-style gambrel roof

A gambrel or gambrel roof is a usually symmetrical two-sided roof with two slopes on each side. The upper slope is positioned at a shallow angle, while the lower slope is steep. This design provides the advantages of a sloped roof while maxim ...

which later became known as Rolleston Hall. Rolleston Hall stood more than 200 years, until it burned down in the late 19th century.

In 1670, a royal decree directed the "building of storehouses to receive imported merchandise ... and tobacco for export" for each of the colony's 20 counties. This marked the beginning of Norfolk's importance as a port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

city, due to its natural deepwater channels. Soon after 1673, the "Half Moone" fort at the site of what is now Town Pointe Park. This fort was constructed due to feared attack by the Dutch, but this threat did not materialize. Norfolk quickly grew in size, and by 1682 a charter for the establishment of the "Towne of Lower Norfolk County" had been issued by Parliament. Norfolk was one of only three cities in the Virginia Colony to receive a royal charter, the other two being Jamestown and Williamsburg

Williamsburg may refer to:

Places

*Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia

*Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood in New York City

*Williamsburg, former name of Kernville (former town), California

*Williams ...

. The town initially encompassed a land area northeast of the point of the confluence of the Eastern and Southern Branches of the Elizabeth River (today the point is in downtown). In 1691, a final county subdivision took place when Lower Norfolk County was split to form Norfolk County (present day Norfolk, Chesapeake, and parts of Portsmouth) and Princess Anne County

County of Princess Anne is a former county in the British Colony of Virginia and the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, first incorporated in 1691. The county was merged into the city of Virginia Beach

on January 1, 1963, ceasing to ...

(present day Virginia Beach). Norfolk was incorporated in 1705 and re-chartered as a borough in 1736.

In 1753, Lt. Governor Robert Dinwiddie

Robert Dinwiddie (1692 – 27 July 1770) was a Scottish colonial administrator who served as the lieutenant governor of Virginia from 1751 to 1758. Since the governors of Virginia remained in Great Britain, he served as the ''de facto'' head o ...

presented the growing city of 4,000 with a long, 104 ounce silver mace. The mace was a symbol of royal authority and is currently displayed in the Chrysler Museum of Art

The Chrysler Museum of Art is an art museum on the border between downtown and the Ghent district of Norfolk, Virginia. The museum was founded in 1933 as the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences. In 1971, automotive heir, Walter P. Chrysler Jr ...

.

By 1775, Norfolk had developed into one of the most prosperous cities in Virginia. It was a major shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other Watercraft, floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation th ...

center and an important trans-shipment point for the export of goods such as tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, corn

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout Poaceae, grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago ...

, cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

, and timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into uniform and useful sizes (dimensional lumber), including beams and planks or boards. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, window frames). ...

from Virginia and North Carolina, to Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and beyond. In turn, goods from the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

such as rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is often aged in barrels of oak. Rum originated in the Caribbean in the 17th century, but today it is produced i ...

and sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

, and finished manufactured products from Europe, were imported back through Norfolk and shipped to the rest of the lower colonies. Much of the West Indies and American colonial products that flowed through the harbor were by this time produced with the use of slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

labor.

Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

Norfolk had been a strong base of

Norfolk had been a strong base of Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

support throughout the start of the American Revolution. In the early summer of 1775, Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

The title Earl of Dunmore was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. The title passed down through generations, with various earls serving ...

, the last Royal Governor of the Colony of Virginia, tried to reestablish control of the colony from Norfolk. In November, a battle took place at Kemp's Landing which provided Dunmore and the loyalists a clear victory, but it was nonetheless clear by then that the war was escalating. The governor immediately issued Dunmore's Proclamation

Dunmore's Proclamation is a historical document signed on November 7, 1775, by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies, royal governor of the British colony of Virginia. The proclamation declared martial law ...

, which promised freedom to any rebel-owned slave who joined His Majesty's forces. At the end of November, Dunmore set up a stronghold in Norfolk, demolishing some 30 houses in the course of its construction. A few days later, based on false intelligence received, Dunmore's 600 soldiers were defeated in the Battle of Great Bridge

The Battle of Great Bridge was fought December 9, 1775, in the area of Great Bridge, Virginia, early in the American Revolutionary War. The refusal by colonial Virginia militia forces led to the departure of Royal Governor Lord Dunmore and any ...

, where 102 of Dunmore's soldiers were killed or injured, compared with just one injured soldier for the patriots. Dunmore and their loyalists fled Norfolk and boarded their ship, thus ending 168 years of British rule in Virginia.

Dunmore remained in the river off Norfolk with a small squadron of armed ships and on New Year's Day 1776, Lord Dunmore's ships began a bombardment that escalated into the Burning of Norfolk

The Burning of Norfolk was an incident that occurred on January 1, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. British Royal Navy ships in the harbor of Norfolk, Virginia, began shelling the town, and landing parties came ashore to burn specif ...

. British troops also went ashore to burn the waterfront buildings, and thus played right into the hands of their enemies. The rebels were quite happy to see a largely Loyalist city destroyed, happier still to be able to blame it on the British, and over the next two days they encouraged the spread of fires, while looting unburned houses. The Virginia Assembly found that of the 882 houses burned during those two days, only 19 had been set alight by the British. A further 416—in effect, all that remained standing—were destroyed in February 1776 to prevent the British from using them as cover if they returned. Only Saint Paul's Episcopal Church survived the bombardment

A bombardment is an attack by artillery fire or by dropping bombs from aircraft on fortifications, combatants, or cities and buildings.

Prior to World War I, the term was only applied to the bombardment of defenseless or undefended obje ...

and subsequent fires, however the church was dented by a cannonball

A round shot (also called solid shot or simply ball) is a solid spherical projectile without explosive charge, launched from a gun. Its diameter is slightly less than the bore of the barrel from which it is shot. A round shot fired from a lar ...

fired by the HMS ''Liverpool''.

Antebellum: rebirth, fire, and disease (1783–1861)

Four years after the Revolutionary War, a fire along the city's waterfront destroyed some 300 buildings and the city experienced a serious economic setback as a result. At the turn of the 19th century, Fort Norfolk was constructed by the Federal government to guard the harbor. During the 1820s the agricultural communities of South Hampton Roads experienced a prolonged recession, resulting in the emigration of families from the region to other areas of the South, especially the frontier areas being opened for settlement. From 1820 to 1830, there was a drop in overall population of about 15,000 in Norfolk County, despite the fact that other urban areas experienced significant population growth. Like other Southern states, Virginia struggled withslavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, especially as it became less important in the mixed agricultural economy that was replacing that of tobacco. Virginia considered ideas to either phase out slavery through law (see Thomas Jefferson Randolph

Thomas Jefferson Randolph (September 12, 1792 – October 7, 1875) of Albemarle County was a Virginia enslaver, soldier and politician who served multiple terms in the Virginia House of Delegates, as rector of the University of Virginia, ...

's 1832 resolution) or to "repatriate" blacks by sending them to Africa to establish a colony at Liberia. The American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

(ACS), established in 1816, was the largest of groups founded for that purpose. Many emigrants from Virginia and North Carolina embarked for Africa from Norfolk. One such emigrant was Joseph Jenkins Roberts

Joseph Jenkins Roberts (March 15, 1809 – February 24, 1876) was an African-American merchant who emigrated to Liberia in 1829, where he became a politician. Elected as the first (1848–1856) and seventh (1872–1876) president of Liberi ...

, a native of Norfolk who would go on to become the first president of Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

. Active emigration through the ACS came to an end following the Civil War.

By 1840, Norfolk's population was 10,920 for the borough proper (not including the rest of the county). With the concentration of population came more interest in education and culture. In 1841 an ambitious new school building was completed for Norfolk Academy, designed by Thomas U. Walter as a replica of the temple of Theseus in Athens. In 1845, Norfolk was incorporated as a city. By 1850 the city's population was 14,326 persons, including 4,295 enslaved African Americans and 956 free African Americans.

Transportation improvements contributed to growth. In 1832 the steam ferry ''Gosport'' began service, linking Norfolk and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

. In 1851, the Commonwealth authorized the charter of an railroad connecting busy port of Norfolk and the growing industrial city of Petersburg. Completed in 1858, this important line was the predecessor of today's Norfolk Southern Railway

The Norfolk Southern Railway is a Class I freight railroad operating in the Eastern United States. Headquartered in Atlanta, the company was formed in 1982 with the merger of the Norfolk and Western Railway and Southern Railway. The comp ...

.

On June 7, 1855, the ship ''Benjamin Franklin'' detoured into Portsmouth for urgent repairs. The city's health officer inspected the ship, as was standard practice at the time, and suspected something was awry, despite assurances from the captain that ship was free of disease. The officer ordered that the ship be held at anchor in the harbor for 11 days. Afterwards, he returned to the ship and allowed it dock under the condition that the ship's hold not be broken. Within several days of the ship's docking, however, the first cases of yellow fever appeared in people whose homes were near the wharf. By July, the epidemic was in full outbreak and would eventually result in the deaths of over 2,000 in Norfolk. At its peak, the epidemic was claiming more than 100 lives a day, and Norfolk did not recover its population fully until after the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. In 1856 the Sisters of Charity founded St. Vincent's Hospital, in part as a reaction to the previous year's epidemic.

American Civil War

In early 1861, Norfolk voters instructed their delegate to vote for ratification of the ordinance of secession. Soon thereafter, Virginia voted to secede from the Union.Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

became the capital of the Confederacy, and the American Civil War began.

When Virginia joined the Confederate States of America they demanded the surrender of all Federal property in their state, including the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a United States Navy, U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest ...

(then called the Gosport Shipyard). Falling for an elaborate Confederate ruse orchestrated by civilian railroad builder, and future Confederate general, William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was a Confederate States Army general, civil engineer, railroad executive, prominent Virginia Readjuster Party, Readjuster and ardent supporter of former slaves. He later represented Virginia in th ...

, the Union shipyard commander Charles Stewart McCauley

Charles Stewart McCauley (February 3, 1793 – May 21, 1869) was an American naval officer in the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

Biography

McCauley was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the decade after the American Revolution and educate ...

ordered the burning of the shipyard and the evacuation of its personnel to Fort Monroe across Hampton Roads. The capture of the shipyard allowed a tremendous amount of war material to fall into Confederate hands including the remains of the burned and scuttled naval frigate USS ''Merrimac''.

In the spring of 1862, the remains of the USS ''Merrimac'' were rebuilt at Norfolk Navy Yard as an ironclad and renamed as the CSS ''Virginia''. The Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

The battle was fought over two days, March 8 and 9, 1862, in Hampton ...

began on March 8. The battle would ultimately ended in a stalemate however, as neither navy was able to do significant damage to the other due to the heavy armor plating. Over the next several months, CSS ''Virginia'' tried in vain to engage the ''Monitor'', but the USS Monitor was under strict orders not to fight unless absolutely necessary.

On May 6, while the Union Army under General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

was fighting the Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The oper ...

, President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

visited Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth o ...

across Hampton Roads. Recognizing the value of Norfolk, he decided on a plan to capture the city and thus eliminate the base for the CSS ''Virginia''. On May 8, Union ships, including the USS Monitor and batteries on Fort Wool opened fire on the Confederate batteries on Sewell's Point. Only the approach of the CSS ''Virginia'' drove the Union ships back to the protection of Fort Monroe. At this point, Lincoln directed the invasion to be on Willoughby Spit, away from the Confederate batteries, the next day. On the morning of May 10, General John Wool landed 6,000 Union soldiers on Willoughby Spit. Within hours, the Union troops arrived at Norfolk. Mayor William Lamb surrendered the city without firing a shot.

For the duration of the Civil War, the city was held under Martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

. Many private and public buildings were confiscated for federal use, including nearby plantations. Mayor Lamb did manage to successfully hide the city's colonial era silver mace underneath a fireplace hearth to avoid having it confiscated or melted down by union troops.

Enslaved African Americans did not wait until the end of the war to be emancipated. With the arrival of Union troops, thousands of slaves escaped to Norfolk and Fort Monroe to claim their freedom. Even before the arrival of northern missionaries, African Americans began to set up schools for children and adults both.

Reconstruction to the Jamestown Exposition (1865–1907)

By 1870, the end of

By 1870, the end of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

was at hand in Norfolk. Union occupation troops withdrew and Virginia was readmitted to the Union. During this time, African-Americans throughout Hampton Roads were elected to state and local offices. Gradually they were restricted from office and voting by the whites' paramilitary violence and intimidation, and increasingly discriminatory legislation, including Jim Crow Laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

to control work, segregated public facilities and transportation, and other aspects of life.

Most significantly, in 1902 Virginia joined other Southern states in creating a new constitution that effectively disenfranchised all African Americans through creating new blocks to voter registration that were selectively and subjectively applied against them. White supremacists achieved their goal: from 1900 to 1904, estimated black voter turnout in the Presidential elections in Virginia dropped to zero.

African Americans would not regain the ability to exercise suffrage and full civil rights until their activism in the Civil Rights Movement secured passage of federal legislation in the mid-1960s. Despite this severe restriction, many African Americans created families, churches, schools, community organizations and stable lives for themselves. Many became landowners and farmed small plots in the Norfolk area. The area's turn to mixed agriculture before the Civil War created a more favorable environment for small plots and mixed produce.

In 1883, the first car of

In 1883, the first car of bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the coal seam, ...

arrived from the Pocahontas fields over the Norfolk & Western Railway

The Norfolk and Western Railway , commonly called the N&W, was a US class I railroad, formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It was headquartered in Roanoke, Virginia, for most of its existence. Its motto was "Precisio ...

and by 1886 the tracks were extended right up to the coal piers at Lambert's Point

Lambert's Point is a point of land on the east shore of the Elizabeth River near the downtown area of the independent city of Norfolk in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia, United States. It includes a large coal exporting faci ...

to handle the increasing volume, creating one of the largest coal transshipment ports in the world. In 1894, classes began in the city's first public high school. That same year the new technology of the electric street railway was introduced to Norfolk and would, within ten years, link Norfolk with Sewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to t ...

, Ocean View, South Norfolk

South Norfolk is a local government district in Norfolk, England. The largest town is Wymondham, and the district also includes the towns of Costessey, Diss, Harleston, Hingham, Loddon and Long Stratton. The council was based in Long S ...

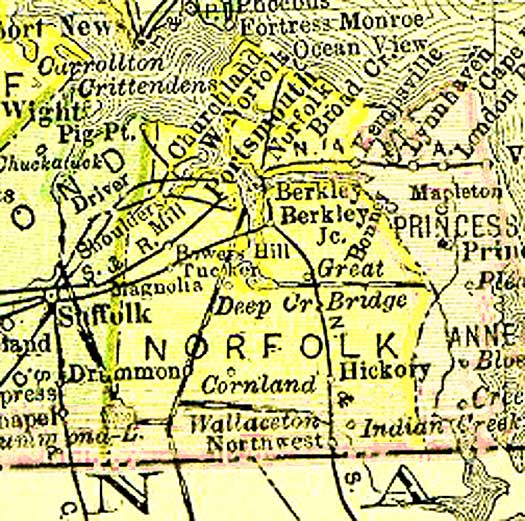

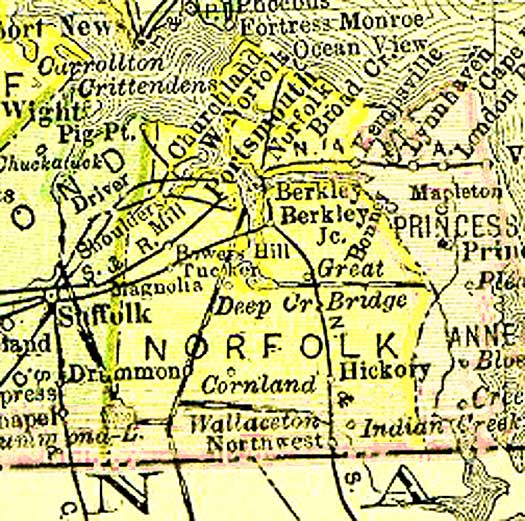

, Berkley, Pinner's Point (all of which were independent communities within Norfolk County at that time), and the neighboring City of Portsmouth.

1907 brought both the Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads.

History

...

and the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition, also known as the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition of 1907, was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anni ...

to Sewell's Point

Sewells Point is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay to t ...

. The large Naval Review

A Naval Review is an event where select vessels and assets of the United States Navy are paraded to be reviewed by the President of the United States or the Secretary of the Navy. Due to the geographic distance separating the modern U.S. Na ...

at the Exposition demonstrated the peninsula's favorable location, laying the groundwork for the world's largest naval base. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, the exposition brought many prominent people including President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, congressmen, senators, and diplomats from 21 countries. Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was an American industrialist and financier. He made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil. He also played a major role in numerous corporations a ...

and Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

also attended the expo. Many naval ships from different countries were present for the celebration. The area where the exposition took would become Naval Air Station Hampton Roads, later Naval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk is a United States Navy base in Norfolk, Virginia, that is the headquarters and home port of the U.S. Navy's Fleet Forces Command. The installation occupies about of waterfront space and of pier and wharf space of the Ham ...

, ten years later in 1917, during the height of World War I.

Resort areas and transportation development

Resort areas in remote areas along the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean grew in the period after the civil war as Norfolk residents embraced the concept of the day trips to the beaches. Ocean View on the bay in Norfolk County was originally surveyed for lots before the war, but establishment of a long narrow gauge steam passenger railroad service between downtown Norfolk and Ocean View crossing what was then known as Tanner's Creek (later renamedLafayette River

The Lafayette River, earlier known as Tanner's Creek, is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 tidal estuary which empties into the Elizabeth River just south ...

) brought the masses. Originally named the Ocean View Railroad, it was later known as the Norfolk and Ocean View Railroad. A small steam locomotive named the ''General William B. Mahone'' hauled ever increasing volumes of passengers, primarily on the weekends. Similarly, the Norfolk & Virginia Beach Railway inaugurated rail service in 1883 to the rural community of Seatack located on the Atlantic Ocean in Princess Anne County

County of Princess Anne is a former county in the British Colony of Virginia and the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, first incorporated in 1691. The county was merged into the city of Virginia Beach

on January 1, 1963, ceasing to ...

. The oceanfront area at Seatack became the site of the area's first resort hotel.

As attendance boomed, in both instances, the steam-powered services between downtown Norfolk and the beaches at Ocean View and Seatack were later replaced by electric-powered trolley cars. These in turn, were later replaced by highways and the automobile. Cottage Toll Road, later largely superseded by Tidewater Drive

State Route 168 is a primary state highway in the South Hampton Roads region of the U.S. state of Virginia. It runs from the border with North Carolina (where it continues as North Carolina Highway 168 towards the Outer Banks) through the in ...

led to Ocean View. Leading from Norfolk to Seatack, where the resort strip became known as Virginia Beach, in 1922, the new hard-surfaced Virginia Beach Boulevard

Virginia Beach Boulevard is a major connector highway which carries U.S. Route 58 most of its length and extends from the downtown area of Norfolk, Virginia, Norfolk to the Oceanfront area of Virginia Beach, Virginia, Virginia Beach, passing throu ...

was a major factor in the growth of the Oceanfront town and adjacent portions of Princess Anne County.

Ocean View gradually evolved into a streetcar suburb

A streetcar suburb is a residential community whose growth and development was strongly shaped by the use of streetcar lines as a primary means of transportation. Such suburbs developed in the United States in the years before the automobile, when ...

, and was annexed by Norfolk in 1923. Virginia Beach became an incorporated town in 1906, and an independent city of the second class in 1952, sharing courts and some constitutional officers with Princess Anne County. 11 years later, the city was politically consolidated with county (which was 100 times larger in land area)to form the modern City of Virginia Beach, now the City of Norfolk's neighbor to the east, part of a wave of political consolidations in the Hampton Roads region which took place between 1952 and 1976.

Modern Era

Expansion through annexation (1906–1959)

Norfolk continued to grow in the first half of the 20th century as it expanded its borders through annexation. In 1906, the

Norfolk continued to grow in the first half of the 20th century as it expanded its borders through annexation. In 1906, the incorporated town

An incorporated town is a town that is a municipal corporation.

Canada

Incorporated towns are a form of local government in Canada, which is a responsibility of provincial rather than federal government.

United States

An incorporated town o ...

of Berkley was annexed, stretching the city limits across the Elizabeth River. The town became a borough along with the neighborhoods of Beacon Light and Hardy Field. Lambert's Point, home of a railroad pier, and Huntersville were annexed into Norfolk five years later in 1911.

In 1923, the city limits were expanded to include Sewell's Point, Willoughby Spit

Willoughby Spit is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States. It is bordered by water on three sides: the Chesapeake Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and Willoughby Bay to the south.

H ...

, the town of Campostella, and Ocean View, adding the naval base and miles of beach property fronting on Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. The Norfolk Naval Base grew rapidly as a result of World War I and this created a housing shortage in the area. These newly incorporated areas grew rapidly along with the 1906-created Larchmont

Larchmont is a village located within the Town of Mamaroneck in Westchester County, New York. Larchmont is a suburb of New York City, located approximately northeast of Midtown Manhattan. The population of the village is 6,453 as of the W ...

neighborhood, five miles (8 km) from downtown. Wards Corner

Wards Corner is a historical suburban shopping center and residential neighborhood in Norfolk, Virginia, located approximately five miles north of downtown and less than four miles southeast of Naval Station Norfolk. The shopping center originat ...

, then just outside Norfolk, became the first non-downtown shopping district in the country. In 1930, Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University (ODU) is a Public university, public research university in Norfolk, Virginia, United States. Established in 1930 as the two-year Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary, it began by educating people with fewer ...

was established as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public university, public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III of England, William III and Queen ...

. ODU awarded its first bachelor's degrees in 1956 and became an independent institution in 1962. Five years later, Norfolk State University

Norfolk State University (NSU) is a Public university, public Historically black colleges and universities, historically black university in Norfolk, Virginia. It is a member of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund and Virginia High-Tech Partnersh ...

was founded as the Norfolk Unit of Virginia State University

Virginia State University (VSU or Virginia State) is a Public university, public Historically black colleges and universities, historically Black land-grant university, land-grant university in Ettrick, Virginia, United States. Founded on , Vi ...

and became an independent institution in 1969.

By 1950, Norfolk was the fifth fastest growing metropolitan area in the United States. As a result of the end of World War II, another housing shortage was created. In 1955, Tanners Creek was annexed and ownership of Broad Creek Village transferred to Housing Authority. Norfolk had officially become the largest city in state, with a population of 297,253. After a smaller annexation in 1959, and a 1988 land swap with Virginia Beach

Virginia Beach (colloquially VB) is the List of cities in Virginia, most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. The city is located on the Atlantic Ocean at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in southeaster ...

, the city assumed its current boundaries.

Highway developments

With the dawn of the

With the dawn of the Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Hi ...

, new highways opened and a series of bridges and tunnels opening over fifteen years would link Norfolk with the Peninsula, Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, and Virginia Beach

Virginia Beach (colloquially VB) is the List of cities in Virginia, most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. The city is located on the Atlantic Ocean at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in southeaster ...

.

On November 1, 1957, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

* Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

* Hampton, New South Wales

* Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

* Hampton, Victoria

** Hampton railway station, Melbo ...

opened to traffic, connecting the Virginia Peninsula with the city, signed as State Route 168. The new two-lane toll bridge-tunnel connection became a portion of Interstate 64

Interstate 64 (I-64) is an east–west Interstate Highway in the Eastern United States. Its western terminus is at Interstate 70, I-70, U.S. Route 40 (US 40), and U.S. Route 61, US 61 in Wentzville, Missouri. Its eastern ter ...

by the end of 1957, connecting Norfolk westward with a limited access freeway. A second parallel tube was built in 1976, expanding the road to four lanes. The two-lane Midtown Tunnel was completed September 6, 1962. On December 1, 1967, the Virginia Beach-Norfolk Expressway

Interstate 264 (I-264) is an Interstate Highway in the US state of Virginia. It serves as the primary east–west highway through the South Hampton Roads region in southeastern Virginia. The route connects the central business districts of ...

( Interstate 264 and State Route 44), a long toll road

A toll road, also known as a turnpike or tollway, is a public or private road for which a fee (or ''Toll (fee), toll'') is assessed for passage. It is a form of road pricing typically implemented to help recoup the costs of road construction and ...

leading from Baltic Avenue in Virginia Beach to Brambleton Avenue in Norfolk, opened to traffic at a cost of $34 million.

In 1991, the new Downtown Tunnel

The Downtown Tunnel on Interstate 264 (Virginia), Interstate 264 (I-264) and U.S. Route 460 Alternate (Chesapeake–Norfolk, Virginia), U.S. Route 460 Alternate (US 460 Alt.) crosses the Southern Branch Elizabeth River, Southern B ...

/ Berkley Bridge complex was completed, with a new system of multiple lanes of highway and interchanges connecting Downtown Norfolk and Interstate 464

Interstate 464 (I-464) is an Interstate Highway in the US state of Virginia. The highway runs from U.S. Route 17 (US 17) and State Route 168 (SR 168) in Chesapeake north to I-264 in Norfolk. I-464 connects two major ...

with the Downtown Tunnel tubes.

Racial segregation in schools (1958–1960)

In 1954, the ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' Supreme Court decision determined that racial segregation in public schools (and public accommodations) was unconstitutional. However, Virginia pursued a policy to avoid desegregation that came to be called Massive Resistance. Among the actions were new state laws, called the Stanley Plan

The Stanley Plan was a package of 13 statutes adopted in September 1956 by the U.S. state of Virginia. The statutes were designed to ensure racial segregation would continue in that state's public schools despite the unanimous ruling of the U.S. ...

, that prohibited state funding for integrated public schools, even as some school districts began to contemplate them. It was a few years after ''Brown'' until the policy was tested.

Norfolk's private schools had been integrated four years before as the city chose to voluntarily comply with the ''Brown'' decision. However, a number of public school division

{{Use mdy dates, date=July 2023

A school division is a geographic division over which a school board has jurisdiction.

Canada

In Canada the term is used for the area controlled by a school board and is used interchangeably with school district, i ...

s (school districts) around the state had been reluctant to do so for fear of losing state funds. In 1958, Federal District Courts in Virginia ordered schools in Arlington County

Arlington County, or simply Arlington, is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of Virginia. The county is located in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from Washington, D.C., the nati ...

, Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in Virginia, United States. It is the seat of government of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Quee ...

, Norfolk, and Warren County, to desegregate. In the fall of 1958, a handful of public schools in three of these widespread areas opened for the first time on a racially integrated basis. In response, Virginia Governor

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor is head of the executive branch of the government of Virginia and is the commander-in-chief of the Virginia National Guard an ...

J. Lindsay Almond ordered the schools to be closed, including six of the Norfolk Public Schools

The Norfolk Public Schools, also known as Norfolk City Public Schools, are the school division responsible for public education in the United States city of Norfolk, Virginia.

History

In 2019 Sharon Byrdsong became the interim superintendent, ...

: Granby High School, Maury High School, Norview High School, Blair Junior High School, Northside Junior High School, and Norview Junior High School.

In Norfolk, the state action had the impact of locking ten thousand children out of school, which raised outcry by the public to a high level. As some children attended makeshift schools in churches, etc., the citizens voted whether to reopen the public schools. The ballot made clear that the Commonwealth of Virginia would stop funding integrated schools.

On January 19, 1959, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals

The Supreme Court of Virginia is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It primarily hears direct appeals in civil cases from the trial-level city and county circuit courts, as well as the criminal law, family law and administrative ...

declared the state law to be in conflict with Virginia's state constitution. The Court of Appeals ordered all public schools to be funded, whether integrated or not. Governor Almond capitulated about ten days later and asked the sitting General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

to rescind several "Massive Resistance" laws. On February 2, 1959, Norfolk's public schools were desegregated

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

when 17 black children entered six previously all-white schools in Norfolk. ''Virginian-Pilot

''The Virginian-Pilot'' is the daily newspaper for Hampton Roads, Virginia. Commonly known as ''The Pilot'', it is Virginia's largest daily. It serves the five cities of South Hampton Roads as well as several smaller towns across southeast Virgi ...

'' editor Lenoir Chambers

Joseph Lenoir Chambers (December 26, 1891January 10, 1970) was an American writer, biographer, historian, and Pulitzer prize-winning newspaper editor. He served in the American Expeditionary Forces, and briefly commanded a combat company, during ...

editorialized against massive resistance, earning the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

.

Decline and revitalization (1960 onward)

As the traditional center ofshipping

Freight transport, also referred to as freight forwarding, is the physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo. The term shipping originally referred to transport by sea but in American English, it has been ...

and port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

activities in the Hampton Roads region, Norfolk's downtown waterfront historically played host to numerous port and shipping-related uses. With the advent of containerized shipping in the mid-20th century, the shipping uses located on Norfolk's downtown waterfront became obsolete as larger and more modern port facilities opened elsewhere in the region. In the second half of the century, Norfolk had a vibrant retail community in its suburbs. Norfolk was also the birthplace of Econo-Travel, now Econo Lodge

Econo Lodge is a budget motel chain based in the United States and Canada and one of the larger subsidiaries of Choice Hotels. The properties contain a minimum of 40 guest rooms and are often located near highways or highway access. All hotels p ...

, one of the nation's first discount motel chains.

Similarly, the advent of newer suburban

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area. They are oftentimes where most of a metropolitan areas jobs are located with some being predominantly residential. They can either be denser or less densely populated ...

shopping destinations spelled demise for the fortunes of downtown's Granby Street

U.S. Route 460 (US 460) in Virginia runs east-west through the southern part of the Commonwealth. The road has two separate pieces in Virginia, joined by a relatively short section in West Virginia. Most of US 460 is a four-lane divided h ...

commercial corridor, located just a few blocks inland from the waterfront. Granby Street traditionally played the role as the premiere shopping and gathering spot in the Hampton Roads region and numerous department stores such as Smith & Welton (1898–1988), Rice's (1918–1985) and Ames and Brownley (1898–1973), hotels and theaters once lined its sidewalks. However, new suburban shopping developments promised more convenience and comfort to the population that had moved to the suburbs. Pembroke Mall

Pembroke Mall was an enclosed shopping mall located in Virginia Beach, Virginia, United States. It was opened in March 1966 as the first shopping mall in the Hampton Roads metro area. It comprised more than 48 stores, including anchor stores Targ ...

in Virginia Beach, the region's first climate-controlled shopping mall

A shopping mall (or simply mall) is a large indoor shopping center, usually Anchor tenant, anchored by department stores. The term ''mall'' originally meant pedestrian zone, a pedestrian promenade with shops along it, but in the late 1960s, i ...

, and JANAF Shopping Center in Norfolk's Military Circle area, were built in this era.

Beginning in the 1970s, Norfolk worked towards reviving its urban core:

Granby Street

To compete with suburban shopping destinations, Norfolk city leaders tried to create a similar mall experience on Granby Street. The city rebranded its commercial core the "Granby Street Mall", closed Granby Street to through-traffic and created a pedestrian mall. The Granby Street Mall did not succeed and the mall endured hardship through the late 1970s and early 1980s.Waterfront developments

Another focus was the waterfront and its decaying piers and warehouses. Norfolk, using Federal urban renewal funds, began large-scale demolitions downtown. This included slum housing that, in the mid-20th century, did not have indoor plumbing or access to running water. The former City Market,

Another focus was the waterfront and its decaying piers and warehouses. Norfolk, using Federal urban renewal funds, began large-scale demolitions downtown. This included slum housing that, in the mid-20th century, did not have indoor plumbing or access to running water. The former City Market, Norfolk Terminal Station

Norfolk Terminal Station was a railroad union station located in Norfolk, Virginia, which served passenger trains and provided offices for the Norfolk and Western Railway, the original Norfolk Southern Railway (1942–1982), Norfolk Southern Ra ...

(the Union railroad station) and The Monticello Hotel were also demolished.

At the water's edge, nearly all of the obsolete shipping and warehousing facilities were demolished and replaced with a new boulevard, Waterside Drive. Among the buildings erected were the

* Waterside Festival Marketplace, an indoor mall similar to Baltimore's Inner Harbor

The Inner Harbor is a historic seaport, tourist attraction, and landmark in Baltimore, Maryland. It was described by the Urban Land Institute in 2009 as "the model for post-industrial waterfront redevelopment around the world". The Inner Harbo ...

Pavilions

* Waterfront Town Point Park

Town Point Park is a waterfront city park on the Elizabeth River in Norfolk, Virginia, USA. The park hosts major outdoor concerts, award-winning festivals and special events each year to include Norfolk Harborfest, Bayou Boogaloo, and 4 July Cel ...

, an esplanade park with wide open riverfront views

* Norfolk Omni Hotel

Omni Hotels & Resorts is an American privately held, international hotel company based in Dallas, Texas. The company was founded in 1958 as Dunfey Hotels, and operates 51 properties in the United States and Canada, totaling over 20,010 rooms and ...

.

On the inland side of Waterside Drive, the demolition of the warehouses and wharves made way for high rise buildings.

MacArthur Center

In the mid 1990s, Norfolk again attempted to rejuvenate Granby Street, which continued to lag behind the waterfront in terms of revitalization. In late 1996, it was announced that a new downtown shopping mall would be built, in whichNordstrom

Nordstrom, Inc. () is an American Luxury goods, luxury department store chain headquartered in Seattle, Washington, and founded by John W. Nordstrom and Carl F. Wallin in 1901. The original store operated exclusively as a shoe store, and a seco ...

would to open a store. The mall was named the MacArthur Center, in honor of the five-star World War II General whose tomb was located across the street from the proposed site. Nearly $100 million dollars in public funds was committed to infrastructure improvements and construction of parking garages to support the shopping mall. The MacArthur Center opened in March 1999 as a three-story enclosed shopping mall with an 18-screen stadium seating movie theater

A movie theater (American English) or cinema (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English), also known as a movie house, cinema hall, picture house, picture theater, the movies, the pictures, or simply theater, is a business ...

.

Other developments

The residential population of downtown continues to grow as commercial buildings are converted into residences and new residential developments are built.See also

* Timeline of Norfolk, Virginia * List of newspapers in Virginia in the 18th-century: Norfolk *List of mayors of Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. It had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia and 100th-most populous city in the United States. The city holds a strate ...

References

Bibliography

{{Norfolk, Virginia