History Of Foreign Relations Of China on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

History of foreign relations of China covers diplomatic, military, political and economic relations in

Japan after 1860 modernized its military after Western models and was far stronger than China. The war, fought in 1894 and 1895, was fought to resolve the issue of control over Korea, which was yet another suzerain claimed by China and under the rule of the

Japan after 1860 modernized its military after Western models and was far stronger than China. The war, fought in 1894 and 1895, was fought to resolve the issue of control over Korea, which was yet another suzerain claimed by China and under the rule of the

Even the

Even the

online

* Clyde, Paul H., and Burton F. Beers. ''The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975'' (Prentice Hall, 1975), university textbook

online

*Cohen, Warren I. '' America's Response to China: A History of Sino-American Relations'' (2010

excerpt and text search

* Dudden, Arthur Power. ''The American Pacific: From the Old China Trade to the Present'' (1992) * Elleman, Bruce A. ''Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989'' (2001) 363 pp. * Fenby, Jonathan. ''The Penguin History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power 1850 to the Present'' (3rd ed. 2019) popular history. * Fogel, Joshua. ''Articulating the Sino-sphere: Sino-Japanese relations in space and time'' (2009) * Grasso, June Grasso, Jay P. Corrin, Michael Kort. ''Modernization and Revolution in China: From the Opium Wars to the Olympics'' (4th ed. 2009

excerpt

* Gregory, John S. ''The West and China since 1500'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003). * Hsü, Immanuel C.Y. ''the rise of modern China'' (6th ed 1999) University textbook with emphasis on foreign policy * Jansen, Marius B. ''Japan and China: From War to Peace, 1894-1972'' (1975). * Kurtz-Phelan, Daniel. ''The China Mission: George Marshall's Unfinished War, 1945-1947'' (WW Norton. 2018). * Li, Xiaobing. ''A history of the modern Chinese army'' (UP of Kentucky, 2007). * Liu, Ta-jen, and Daren Liu. ''US-China relations, 1784-1992'' (Univ Pr of Amer, 1997). * Liu, Lydia H. ''The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making '' (2006) theoretical study of UK & Chin

excerpt

* Macnair, Harley F. and Donald F. Lach. ''Modern Far Eastern International Relations'' (1955

online free

* Mancall, Mark. ''China at the center: 300 years of foreign policy'' (1984), Scholarly survey; 540pp * Perkins, Dorothy. ''Encyclopedia of China'' (1999

online

* Quested, Rosemary K.I. ''Sino-Russian relations: a short history'' (Routledge, 2014

online

* Song, Yuwu, ed. ''Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations'' (McFarland, 2006

excerpt

* Sutter, Robert G. ''Historical Dictionary of Chinese Foreign Policy'' (2011

excerpt

* Vogel, Ezra F. ''China and Japan: Facing History'' (2019

excerpt

* Wang, Dong. ''The United States and China: A History from the Eighteenth Century to the Present'' (2013) * Westad, Odd Arne. ''Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750'' (Basic Books; 2012) 515 pages; comprehensive scholarly history * Wills, John E. ed. ''Past and Present in China's Foreign Policy: From "Tribute System" to "Peaceful Rise".'' (Portland, ME: MerwinAsia, 2010). .

online

* Chi, Madeleine. ''China Diplomacy, 1914-1918'' (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1970) * Chien, Frederick Foo. ''The opening of Korea: a study of Chinese diplomacy, 1876-1885'' (Shoe String Press, 1967). * Dallin, David J. ''The rise of Russia in Asia'' (Yale UP, 1949

online free to borrow

* Dean, Britten. "British informal empire: The case of China." ''Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics'' 14.1 (1976): 64–81. * Fairbank, John King, E.O. Reischauer, and Albert M. Craig. ''East Asia: the modern transformation'' (Houghton Mifflin, 1965

online

* Fairbank, John K. ed.''The Chinese World Order: Traditional China's Foreign Relations'' (1968

online

* Fairbank, John King. "Chinese diplomacy and the treaty of Nanking, 1842." ''Journal of Modern History'' 12.1 (1940): 1-30

Online

* Feis, Herbert. ''China Tangle: American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission'' (1960

Online free to borrow

* Garver, John W. ''Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937-1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism'' (Oxford UP, 1988). * Hara, Takemichi. "Korea, China, and Western Barbarians: Diplomacy in Early Nineteenth-Century Korea." ''Modern Asian Studies'' 32.2 (1998): 389–430. * Hibbert, Christopher. ''The dragon wakes: China and the West, 1793-1911'' (1970

online free to borrow

popular history * Hsü, Immanuel C.Y. ''China's Entrance into the Family of Nations: The Diplomatic Phase, 1858–1880'' (1960), * Lasek, Elizabeth. "Imperialism in China: A methodological critique." ''Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars'' 15.1 (1983): 50–64

online

* Luo, Zhitian. "National humiliation and national assertion: The Chinese response to the twenty-one demands." ''Modern Asian Studies'' 27.2 (1993): 297-31

online

* Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''The international relations of the Chinese empire Vol. 1'' (1910) to 1859

online

** Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''The international relations of the Chinese empire'' vol 2 1861-1893 (1918

online

** Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''The international relations of the Chinese empire'' vol 3 1894–1916. (1918

online

* Nathan, Andrew J. "Imperialism’s effects on China." ''Bulletin of concerned Asian scholars'' 4.4 (1972): 3–8

Online

* Nish, Ian. (1990) "An Overview of Relations between China and Japan, 1895–1945." ''China Quarterly'' (1990) 124 (1990): 601–623

online

* Perdue, Peter. ''China marches West: The Qing conquest of Central Eurasia'' (2005) * Pollard, Robert T. ''China's Foreign Relations, 1917-1931'' (1933; reprint 1970). * Rowe, William T. ''China's last Empire: The great Qing'' (2009) * Standaert, Nicolas. "New trends in the historiography of Christianity in China." ''Catholic Historical Review'' 83.4 (1997): 573–613

online

* Sun, Youli, and You-Li Sun. ''China and the Origins of the Pacific War, 1931-1941'' (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993) * Suzuki, Shogo''. Civilization and empire: China and Japan's encounter with European international society'' (2009). * Taylor, Jay. ''The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the struggle for modern China'' (2nd ed. 2011) * Thorne, Christopher G. ''The limits of foreign policy; the West, the League, and the Far Eastern crisis of 1931-1933'' (1972

online

* Wade, Geoff. "Engaging the south: Ming China and Southeast Asia in the fifteenth century." ''Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient'' 51.4 (2008): 578–638. * Wright, Mary C. "The Adaptability of Ch'ing Diplomacy." ''Journal of Asian Studies'' 17.3 (1958): 363–381. * Zhang, Yongjin. ''China in the International System, 1918-20: the Middle Kingdom at the periphery'' (Macmillan, 1991) * Zhang, Feng. "How hierarchic was the historical East Asian system?." ''International Politics'' 51.1 (2014): 1-22

Online

excerpt

* Foot, Rosemary. ''The practice of power: US relations with China since 1949'' (Oxford UP, 1995). * Fravel, M. Taylor. ''Active Defense: China's Military Strategy since 1949'' (Princeton Studies in International History and Politics) (2019)

online reviews

* Garson, Robert A. ''The United States and China since 1949: a troubled affair'' (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994). * Garver, John W. ''China's Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People's Republic'' (2nd ed. 2018) comprehensive scholarly history

excerpt

* Goh, Evelyn. ''Constructing the US Rapprochement with China, 1961–1974: From'Red Menace' to 'Tacit Ally'.'' (Cambridge UP, 2004)

online

*Gosset, David. ''China's subtle diplomacy,'' (2011

* Gurtov, Melvin, and Byong-Moo Hwang. ''China under threat: The politics of strategy and diplomacy'' (Johns Hopkins UP, 1980) an explicitly Maoist interpretation. *Hunt, Michael H. ''The Genesis of Chinese Communist foreign-policy'' (1996) *Jian, Chen. ''China's road to the Korean War'' (1994) * Keith, Ronald C. ''Diplomacy of Zhou Enlai'' (Springer, 1989). * Li, Mingjiang. ''Mao's China and the Sino-Soviet Split: Ideological Dilemma'' (Routledge, 2013). * Luthi, Lorenz. ''The Sino-Soviet split: Cold War and the Communist world'' (2008) * MacMillan, Margaret. Nixon and Mao: The week that changed the world. Random House Incorporated, 2008. * Poole, Peter Andrews. "Communist China's aid diplomacy." Asian Survey (1966): 622–629. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2642285 * Qiang, Zhai. "China and the Geneva Conference of 1954." ''China Quarterly'' 129 (1992): 103–122. *Sutter, Robert G. ''Foreign Relations of the PRC: The Legacies and Constraints of China's International Politics Since 1949'' (Rowman & Littlefield; 2013) 355 page

excerpt and text search

* Tudda, Chris. A Cold War Turning Point: Nixon and China, 1969–1972. LSU Press, 2012. *Yahuda, Michael. ''End of Isolationism: China's Foreign Policy After Mao'' (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2016) * Zhai, Qiang. ''The dragon, the lion & the eagle: Chinese-British-American relations, 1949-1958'' (Kent State UP, 1994). * Zhang, Shu Guang. Economic Cold War: America's Embargo against China and the Sino-Soviet Alliance, 1949–1963. Stanford University Press, 2001.

"Foundations of Chinese Foreign Policy

online documents in English from the Wilson Center in Washington *

"Reform and opening in China, 1978-

online documents in English from the Wilson Center in Washington {{DEFAULTSORT:Foreign Relations Of The People's Republic Of China

History of China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

from 1800 to the modern era. For the earlier period see Foreign relations of imperial China : ''For the later history after 1800 see History of foreign relations of China.''

The foreign relations of Imperial China from the Qin dynasty until the Qing dynasty encompassed many situations as the fortunes of dynasties rose and fell. Chinese c ...

, and for the current foreign relations of China see Foreign relations of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), has full diplomatic relations with 178 out of the other 193 United Nations member states, Cook Islands, Niue and the State of Palestine. Since 2019, China has had the most diplomatic miss ...

.

Qing Dynasty

By the mid 19th century, Chinese stability had come under increasing threat from both domestic and international sources. Social unrest and serious revolts became more common while the regular army had was too weak to deal with foreign military forces. Chinese leaders increasingly feared the impact of Western ideas. John Fairbank argues that in 1840 to 1895 China's response to the worsening relations with Western nations came in four phases. China's military weakness was interpreted in the 1840s and 1850s as a need for Western arms. Very little was achieved in this regard until much later. In the 1860s there was a focus on acquiring Western technology—as Japan was doing very successfully at the same time, but China lagged far behind. The 1870s to 1890s were characterized with efforts to reform and revitalize the Chinese political system more broadly. There was steady moderate progress, but efforts to leap forward such as theHundred Days' Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu E ...

in 1898 roused the conservatives who stamped out the effort and executed its leaders. There was a rise in Chinese nationalism

Chinese nationalism () is a form of nationalism in the People's Republic of China (Mainland China) and the Republic of China on Taiwan which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of all Chi ...

, as a sort of echo of Western nationalism, but that led to a quick defeat in war with Japan in 1895. An intense reaction against modernization set in at the grassroots level in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

Opium Wars

European commercial interests sought to end the trading barriers, but China fended off repeated efforts by Britain to reform the trading system. Increasing sales of Indianopium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

to China by British traders led to the First Opium War

The First Opium War (), also known as the Opium War or the Anglo-Sino War was a series of military engagements fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of the ...

(1839–1842). The superiority of Western militaries and military technology

Military technology is the application of technology for use in warfare. It comprises the kinds of technology that are distinctly military in nature and not civilian in application, usually because they lack useful or legal civilian application ...

like steamboats

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

and Congreve rockets

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor William Congreve (inventor), Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon Mysorean rockets, the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the E ...

forced China to open trade with the West on Western terms.

The Second Opium War also known as the Arrow War, in 1856-60 saw a joint Anglo-French military mission including Great Britain and the French Empire win an easy victory. The agreements of the Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860. In China, they are regarded as amon ...

led to the ceding of Kowloon Peninsula

The Kowloon Peninsula is a peninsula that forms the southern part of the main landmass in the territory of Hong Kong, alongside Victoria Harbour and facing toward Hong Kong Island. The Kowloon Peninsula and the area of New Kowloon are collect ...

as part of Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

.

Unequal treaties

A series of "unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

", including the Treaty of Nanking

The Treaty of Nanjing was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the Unequal Treaties.

In the ...

(1842), the treaties of Tianjin

The Treaty of Tientsin, also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several documents signed at Tianjin (then romanized as Tientsin) in June 1858. The Qing dynasty, Russian Empire, Second French Empire, United Kingdom, and t ...

(1858), and the Beijing Conventions (1860), forced China to open new treaty ports

Treaty ports (; ja, 条約港) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Japanese Empire.

...

, including Canton (Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

), Amoy (Xiamen

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong'an, ...

), and Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

. The treaties also allowed the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

to set up Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

as a Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

and established international settlements in the treaty ports under the control of foreign diplomats. China was required to accept diplomats at the capital in Peking, provided for the free movement for foreign ships in Chinese rivers, kept its tariffs low, and opened the interior to Christian missionaries

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such as ...

. Manchu leaders of the Qing government found the treaties useful, because they forced the foreigners into a few limited areas, so that the vast majority of Chinese had no contact whatsoever with them or their dangerous ideas. The missionaries, however, ventured more widely but they were widely distrusted and made very few converts. Their main impact was setting up schools and hospitals. Since the 1920s, the "unequal treaties" have been a centerpiece of angry Chinese grievances against the West in general.

Suzerain and tributaries

For centuries China had claimedsuzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is calle ...

authority over numerous adjacent areas. The areas had internal autonomy but were forced to give tribute to China while being theoretically under the protection of China in terms of foreign affairs. By the 19th century the relationships were nominal, and China exerted little or no actual control. The great powers did not recognize China's fiefdom and one by one seized the supposed suzerain areas. Japan moved to dominate the Korean Empire

The Korean Empire () was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by Emperor Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire stood until Japan's annexation of Korea in August 1910.

During the Korean Empire, Emperor Gojong oversaw the Gwa ...

(and annexed it in 1910) and seized the Ryukyus

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

; France took Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

; Britain took Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

; Russia took parts of Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. Only Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

was left, and that was highly problematic since the Tibetans, as most of the supposed suzerainty, had never accepted Chinese claims of lordship and tribute. The losses humiliated China and marked it as a repeated failure.

Christian missionaries

Catholic missions began with theJesuit China missions

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a si ...

from France and Italy in the 16th century. For a while were highly successful in placing intellectuals and scientists in the royal court. The Pope, however, prohibited the priests from making accommodations to Confucianism or paganism. The Jesuits left, but returned in 1842. Converts were from the lower social strata, and numbered about 240,000 in 1840 and 720,000 in 1901. The Jesuits opened Aurora University

Aurora University (AU) is a private university in Aurora, Illinois. In addition to its main campus and the Orchard Center in Aurora, AU offers programs online, at its George Williams College campus in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, and at the Woods ...

in Shanghai in 1903 to reach an elite audience. German missionaries arrived in the late 19th century, and Americans arrived in force in the 1920s, largely to replace the French.

Beginning in Protestant missionaries started to come, to include thousands of men, their wives and children, and unmarried female missionaries. These were not individual operations, they were sponsored and financed by organized churches in their home country. The 19th century is one of steady geographical expansion, which was reluctantly allowed by the Chinese government every time it lost a war. At first they were limited to the Canton area. In the 1842 treaty ending the First Opium War missionaries were granted the right to live and work in five coastal cities. In 1860, the treaties ending the Second Opium War opened up the entire country to missionary activity. Protestant missionary activity exploded during the next few decades. From 50 missionaries in China in 1860, the number grew to 2,500 (counting wives and children) in 1900. 1,400 of the missionaries were British, 1,000 were Americans, and 100 were from Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

, mostly Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

. Protestant missionary activity peaked in the 1920s and thereafter declined due to war and unrest in China, As well as a sense of frustration among the missionaries themselves. By 1953, all Protestant missionaries had been expelled by the communist government of China.

In long-term perspective, the major impact of the missions was not the thousands of converts out of million of people, but introducing modern medical standards, and especially building schools for the few families eager to learn about the outside world. The hospitals not only cured sick people, they taught hygiene and care of children. They lessened the hostility of Chinese officials. The key leader of the 1911 Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

, Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

spent four-year in exile in Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, where he studied in Christian schools

A Christian school is a school run on Christian principles or by a Christian organization.

The nature of Christian schools varies enormously from country to country, according to the religious, educational, and political cultures. In some count ...

and eventually converted.

When missionaries returned home they typically preached a highly favorable view toward China, and a negative view toward Japan, helping promote public opinion in the West that increasingly supported China. At the local level across China, for the vast majority of the population, missionaries were the only foreigners they ever saw. Outside the protected international centers, they came under frequent verbal attack, and sometimes violent episodes. This led the international community to threaten military action to protect missionaries, as their diplomats demanded the government provide more and more protection. Attacks reached a crescendo during the Boxer Rebellion, which had a major anti-missionary component. The Boxers killed over 200 foreign missionaries and thousands of Chinese Christians. Dr. Eleanor Chesnut was killed by a mob in 1905. Likewise nationalist movements in the 1920s and 1930s also had an anti-missionary component.

First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

A weakened China lost wars with Japan and gave up nominal control over the Ryukyu Islands in 1870 to Japan. After theFirst Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

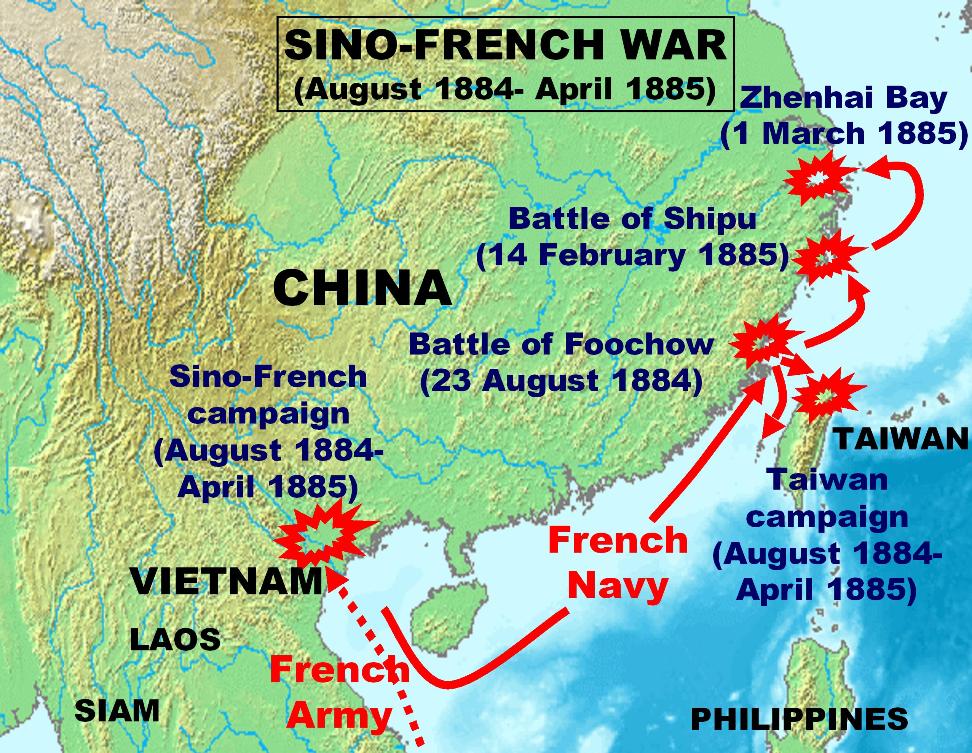

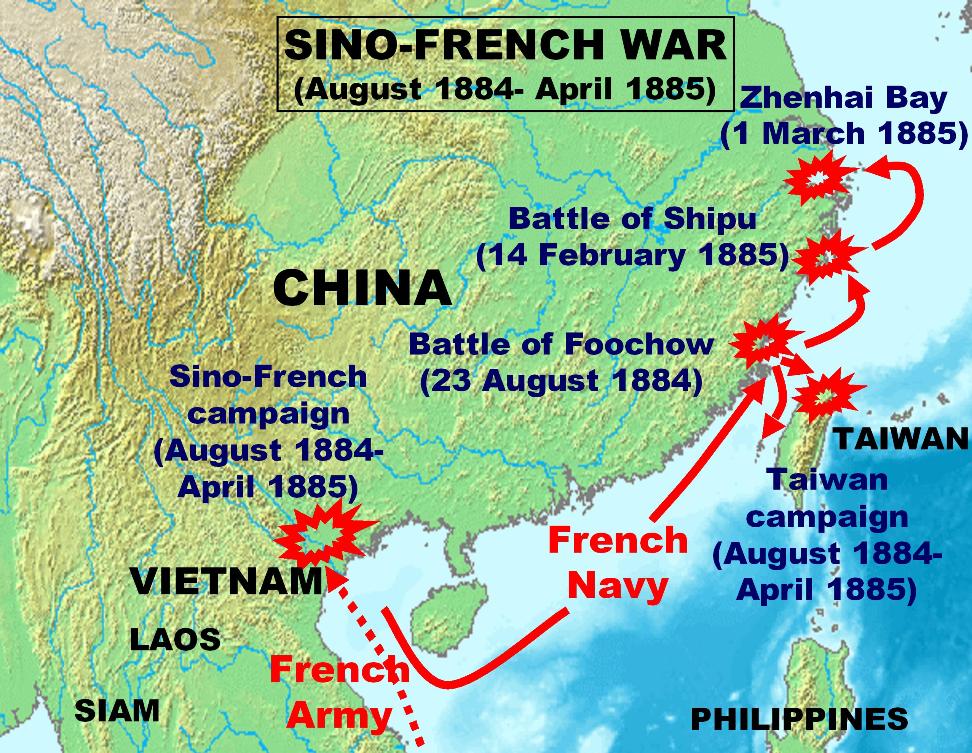

of 1894 it lost Formosa to Japan. After the Sino-French War

The Sino-French War (, french: Guerre franco-chinoise, vi, Chiến tranh Pháp-Thanh), also known as the Tonkin War and Tonquin War, was a limited conflict fought from August 1884 to April 1885. There was no declaration of war. The Chinese arm ...

of 1884–1885, France took control of Vietnam, another supposed "tributary state." After Britain took over Burma, as a show of good faith they maintained the sending of tribute to China, putting themselves in a lower status than in their previous relations. To affirm this, Britain agreed in the Burma convention in 1886 to continue the Burmese payments to China every 10 years, in return for which China would recognise Britain's occupation of Upper Burma

Upper Myanmar ( my, အထက်မြန်မာပြည်, also called Upper Burma) is a geographic region of Myanmar, traditionally encompassing Mandalay and its periphery (modern Mandalay, Sagaing, Magway Regions), or more broadly speak ...

.

Japan after 1860 modernized its military after Western models and was far stronger than China. The war, fought in 1894 and 1895, was fought to resolve the issue of control over Korea, which was yet another suzerain claimed by China and under the rule of the

Japan after 1860 modernized its military after Western models and was far stronger than China. The war, fought in 1894 and 1895, was fought to resolve the issue of control over Korea, which was yet another suzerain claimed by China and under the rule of the Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and re ...

. A peasant rebellion led to a request by the Korean government for China to send in troops to stabilize the country. The Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

responded by sending its own force to Korea and installing a puppet government in Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 ...

. China objected and war ensued. It was a brief affair, with Japanese ground troops routing Chinese forces on the Liaodong Peninsula

The Liaodong Peninsula (also Liaotung Peninsula, ) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located between the mouths of the Daliao River (the ...

and nearly destroying the Chinese navy in the Battle of the Yalu River.

Treaty of Shimonoseki

China, badly defeated, sued for peace and was forced to accept the harshTreaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

Signed on April 17, 1895. China became responsible for a financial indemnity of £30 million. It had to surrender To Japan the island of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

and the Pescatore Islands. Japan received most favored nation status, like all the other powers/ Korea became nominally independent, although the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

were vying for control. The most controversial provision ceded the Liaodong Peninsula

The Liaodong Peninsula (also Liaotung Peninsula, ) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located between the mouths of the Daliao River (the ...

to Japan. However this was not acceptable. Russia, taking the self-appointed mantle of protector of China, worked with Germany and France to intervene and forced Japan to withdraw from Liaodong Peninsula. To pay the indemnities, British French and Russian banks loaned China the money, but they also gained other advantages. Russia in 1896 was given permission to extend its Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

across Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

to reach Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

, a 350-mile shortcut. The new Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

, was controlled by the Russians, and became a major military factor for them In controlling key parts of Manchuria. Later in 1896 Russia and China made a secret alliance, whereby Russia would work to prevent further Japanese expansion at China's expense. In 1898 Russia obtained a 25-year lease over the Liadong Peninsula in southern Manchuria, including the ice free harbor of Port Arthur, their only such facility in the East. An extension of the Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

to Port Arthur greatly expanded Russian military capabilities in the Far East.

Reforms in 1890s

One of the government's main source of income was a five percent tariff on imports. The government hired Robert Hart (1835-1911), a British diplomat to run it from 1863. He set up an efficient system based in Canton that was largely free of corruption, and expanded it to other ports. The top echelon of the service was recruited from all the nations trading with China. Hart promoted numerous modernising programs. His agency established a modern postal service and supervision of internal taxes on trade. Hart helped establish its own embassies in foreign countries. He helped set up theTongwen Guan

The School of Combined Learning, or the Tongwen Guan () was a government school for teaching Languages of Europe, Western languages (and later scientific subjects), founded at Peking (Beijing), China in 1862 during the late-Qing dynasty, right af ...

(School of Combined Learning) in Peking, with a branch in Canton, to teach foreign languages, culture and science. In 1902 the Tongwen Guan was absorbed into the Imperial University, now Peking University

Peking University (PKU; ) is a public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Peking University was established as the Imperial University of Peking in 1898 when it received its royal charter ...

.

Hundred Days Reform fails in 1898

The ''Hundred Days Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu E ...

'' was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement from 11 June to 22 September 1898. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emperor

The Guangxu Emperor (14 August 1871 – 14 November 1908), personal name Zaitian, was the tenth Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the ninth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign lasted from 1875 to 1908, but in practice he ruled, wi ...

and his reform-minded supporters. Following the issuing of over 100 reformative edicts, a coup d'état ("The Coup of 1898", Wuxu Coup

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu E ...

) was perpetrated by powerful conservative opponents led by Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; mnc, Tsysi taiheo; formerly Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Empress Dowager T'zu-hsi; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908), of the Manchu people, Manchu Nara (clan)#Yehe Nara, Yehe Nara clan, was a Chinese nob ...

. The Emperor was locked up until his death and key reformers were exiled or fled.

Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) was in control of imperial policy after 1861; she had remarkable political skills but historians blame her for major policy failures and the growing weakness of China. Her reversal of reforms in 1898 and especially support for the Boxers caused all the powers to join against her. Late Qing China remains a symbol of national humiliation and weakness in Chinese and international historiography. Scholars attribute Cixi's "rule behind the curtains" responsible for the ultimate decline of the Qing dynasty and its capitulatory peace with foreign powers. Her failures hastened the revolution to overthrow the dynasty.

Boxer rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion (1897–1901) was an anti-foreigner movement by theRighteous Harmony Society

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, b ...

in China between 1897 and 1901. They attacked and often killed missionaries, Christian converts, and foreigners. They held the international diplomats in Peking under siege. The ruler of China, the Dowager Empress Cixi, supported the Boxers and the Chinese government paid the penalty. The uprising was crushed by the ad hoc Eight Nation Alliance

The Eight-Nation Alliance was a multinational military coalition that invaded northern China in 1900 with the stated aim of relieving the foreign legations in Beijing, then besieged by the popular Boxer militia, who were determined to remove f ...

of major powers. On top of all the damage and pillage, China was forced to pay annual installments of an indemnity of $333 million American dollars to all the victors—actual total payments amounted to about $250 million. Robert Hart, the inspector general of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service

The Chinese Maritime Customs Service was a Chinese governmental tax collection agency and information service from its founding in 1854 until it split in 1949 into services operating in the Republic of China on Taiwan, and in the People's Republ ...

, was the chief negotiator for the peace terms. The indemnity, despite some beneficial programs, was "nothing but bad" for China, as Hart had predicted at the beginning of the negotiations.

Manchuria

Manchuria was a contested zone with Russia and Japan taking control away from China and in the process going to war themselves in 1904–1905.Republican China

The Republican Revolution of 1911 overthrew the imperial court and brought an era of confused politics.Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

became president in 1912 and, with support from regional war lords, tried to be a dictator. He showed little interest in foreign affairs apart from obtaining loans from Europe. When he suddenly died in 1916 the national government was left in chaos.

When World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

broke out in 1914, China officially entered the war and played a small role. Japan seized the German possessions in China. In January 1915 Japan issued the Twenty-One Demands

The Twenty-One Demands ( ja, 対華21ヶ条要求, Taika Nijūikkajō Yōkyū; ) was a set of demands made during the First World War by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu to the government of the Republic of China on 18 ...

. The goal was to greatly extend Japanese control of Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

and of the Chinese economy

The China, People's Republic of China has an upper middle income Developing country, developing Mixed economy, mixed socialist market economy that incorporates economic planning through Industrial policy, industrial policies and strategic Five- ...

. The Chinese public responded with a spontaneous nationwide boycott of Japanese goods; Japan's exports to China fell by 40%. Britain was officially a military ally of Japan but was affronted and no longer trusted Japan. With the British tied down on the Western Front against Germany, Japan's position was strong. Nevertheless, Britain and the United States forced Japan to drop the fifth set of demands that would have given Japan a large measure of control over the entire Chinese economy and ended the Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

. Japan and China reached a series of agreements which ratified the first four sets of goals on 25 May 1915. Japan gained a little at the expense of China, but Britain refused to renew the alliance and American opinion turned hostile. The Paris Peace Conference in 1919 resulted in the Versailles Treaty that allowed Japan to retain territories in Shandong that had been surrendered by Germany in 1914. Chinese students launched the May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chinese ...

in 1919, inspiring a nationwide nationalistic hostility against Japan and the other foreign powers.

After 1916 almost all of China was in the hands of regional warlords. Until 1929 the Nationalist government was a small rump establishment based in Beijing, with little or no control over most of China. However it did control foreign affairs, and was recognized by foreign countries. It receive the customs revenue; the money was largely used to pay off old debts, such as the indemnities for the Boxer Rebellion. It managed to negotiate an increase in the customs revenue, and represented China in international affairs such as the Paris peace conference. It tried with limited success to renegotiate the unequal treaties. Britain and the other powers continue to control Shanghai and the other port cities until the late 1920s.

In 1931, Japan seized control of Manchuria over the objections of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. Japan quit the League, which was helpless. The most active Chinese diplomat was Wellington Koo

Koo Vi Kyuin (; January 29, 1888 – November 14, 1985), better known as V. K. Wellington Koo, was a statesman of the Republic of China. He was one of Republic of China's representatives at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

Wellington Koo ...

.

German role

The German military had a major role in Republican China. TheImperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

was in charge of Germany's Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory

The Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory was a German colonial empire, German leased territory in Qing dynasty, Imperial and Republic of China (1912–1949), Early Republican China from 1898 to 1914. Covering an area of , it centered on Jiaozhou Ba ...

, and spent heavily to set up modern facilities that would be a showcase for Asia. Japan seized the German operations in 1914 after sharp battles. After World War I, the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

provided extensive advisory services to the Republic of China, especially training for the Chinese army. Colonel General Hans von Seeckt

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (22 April 1866 – 27 December 1936) was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany ...

, the former commander the German army, organized the training of China's elite National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

units and the fight against communists in 1933–1835. All military academies had German officers, as did most army units. In addition, German engineers provided expertise and bankers provided loans for China's railroad system. Traded with Germany flourished in the 1920s, with Germany as China's largest supplier of government credit. The last major advisor left in 1938, after Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

had only allied itself with Japan, the great enemy of the Republic of China. Nevertheless Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

continued to hope for using Germany as a model for his nation, as his mentor Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

had recommended.

War with Japan: 1937–1945

Japan invaded in 1937, launching theSecond Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

. By 1938, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

was a strong supporter of China. Michael Schaller says that during 1938:

:China emerged as something of a symbol of American-sponsored resistance to Japanese aggression.... A new policy appeared, one predicated on the maintenance of a pro-American China which might be a bulwark against Japan. The United States hoped to use China as the weapon with which to contain Tokyo's larger imperialism. Economic assistance, Washington hoped, could achieve this result.

Even the

Even the isolationists

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

who opposed war in Europe supported a hard-line against Japan. American public sympathy for the Chinese, and hatred of Japan, was aroused by reports from missionaries, novelists such as Pearl Buck

Pearl Sydenstricker Buck (June 26, 1892 – March 6, 1973) was an American writer and novelist. She is best known for ''The Good Earth'' a bestselling novel in the United States in 1931 and 1932 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. In 1938, Buc ...

, and ''Time Magazine

''Time'' (stylized in all caps) is an American news magazine based in New York City. For nearly a century, it was published weekly, but starting in March 2020 it transitioned to every other week. It was first published in New York City on Mar ...

'' of Japanese brutality in China, including reports surrounding the Nanjing Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

, called the 'Rape of Nanking'. By early 1941, the U.S. was preparing to send American planes flown by American pilots under American command, but wearing Chinese uniforms, to fight the Japanese invaders and even to bomb Japanese cities. There were delays and the "Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States Ar ...

" under Claire Lee Chennault

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the "Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force in World War II.

Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fighte ...

finally became operational days after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

(December 7, 1941) brought the U.S. into the war officially. The Flying Tigers were soon incorporated into the United States Army Air Force

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, which made operations in China a high priority, and generated enormous favorable publicity for the China in the U.S.

After Japan took Southeast Asia, American aid had to be routed through British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

and over the Himalayan Mountains

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

at enormous expense and frustrating delay. Chiang's beleaguered government was now headquartered in remote Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Romanization, alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a Direct-administered municipalities of China, municipality in Southwes ...

. Roosevelt sent Joseph Stilwell

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. An early American popular hero of the war for leading a column walking ...

to train Chinese troops and coordinate military strategy. He became the Chief of Staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, served as U.S. commander in the China Burma India Theater, was responsible for all Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

supplies going to China, and was later Deputy Commander of South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allies of World War II, Allied operations in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II, South-East Asian Theatre during the World War II, Second World War.

Histo ...

. Despite his status and position in China, he became involved in conflicts with other senior Allied officers, over the distribution of Lend-Lease materiel, Chinese political sectarianism and proposals to incorporate Chinese and U.S. forces in the 11th Army Group (which was under British command). Madame Chiang Kaishek, who had been educated in the U.S., addressed the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

and toured the country to rally support for China. Congress amended the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

and Roosevelt moved to end the unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

. Chiang and Mme. Chiang met with Roosevelt and Churchill at the Cairo Conference

The Cairo Conference (codenamed Sextant) also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of the 14 summit meetings during World War II that occurred on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held in Cairo, Egypt, between the United Kingdo ...

of late 1943, but promises of major increases in aid did not materialize.

The perception grew that Chiang's government, with poorly equipped and ill-fed troops was unable to effectively fight the Japanese or that he preferred to focus more on defeating the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victoriou ...

. China Hands

The term ''China Hand'' originally referred to 19th-century merchants in the treaty ports of China, but came to be used for anyone with expert knowledge of the language, culture, and people of China. In 1940s America, the term ''China Hands'' came ...

advising Stilwell argued that it was in American interest to establish communication with the Communists to prepare for a land-based counteroffensive invasion of Japan. The Dixie Mission

The United States Army Observation Group, commonly known as the Dixie Mission, was the first US effort to gather intelligence and establish relations with the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Liberation Army, then headquartered in the mo ...

, which began in 1943, was the first official American contact with the Communists. Other Americans, led by Chennault, argued for air power. In 1944, Generalissimo Chiang acceded to Roosevelt's request that an American general take charge of all forces in the area, but demanded that Stilwell be recalled. General Albert Coady Wedemeyer

General Albert Coady Wedemeyer (July 9, 1896 – December 17, 1989) was a United States Army commander who served in Asia during World War II from October 1943 to the end of the war. Previously, he was an important member of the War Planning Board ...

replaced Stilwell, Patrick J. Hurley became ambassador, and Chinese-American relations became much smoother. The U.S. had included China in top-level diplomacy in the hope that large masses of Chinese troops would defeat Japan with minimal American casualties. When that hope was seen as illusory, and it was clear that B-29 bombers could not operate effectively from China, China became much less important to Washington, but it was promised a seat in the new UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

, with a veto.

Civil War

When civil war threatened, PresidentHarry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

sent General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

to China at the end of 1945 to broker a compromise between the Nationalist government and the Communists, who had established control in much of northern China. Marshall hoped for a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

, and brought the two distrustful sides together. At home, many Americans saw China as a bulwark against the spread of communism, but some Americans hoped that the Communists would remain on friendly terms with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. Mao had long admired the U.S.—George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

was a hero to him—and saw it as an ally in the Second World War. He was bitterly disappointed when the U.S. would not abandon the Nationalists, writing that "the imperialists who had always been hostile to the Chinese people will not change overnight to treat us on an equal level." His official policy was "wiping out the control of the imperialists in China completely." Truman and Marshall, while supplying military aid and advice, determined that American intervention could not save the Nationalist cause. One recent scholar argues that the Communists won the Civil War because Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

made fewer military mistakes and Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

antagonized key interest groups. Furthermore, his armies had been weakened in the war against Japanese. Meanwhile, the Communists promised to improve the ways of life for groups such as farmers.

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's policy was opportunistic and utilitarian. He offered official Soviet support only when the People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, ...

had virtually won the Civil War. Sergey Radchenko Sergey S. Radchenko () is a Soviet-born British historian. He is the Wilson E. Schmidt Distinguished Professor at the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and visiting professor at Ca ...

argues that "all the talk of proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all communist revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory that ...

in the Sino-Soviet alliance was but a cloak for Soviet expansionist ambitions in East Asia".

People's Republic of China

International recognition

Since its establishment in 1949, the People's Republic of China has worked vigorously to win international recognition and support for its position that it is the sole legitimate government of all China, includingTibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

, Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

, Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

, (Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

), the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and islands in the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phil ...

.

Upon its establishment in 1949, the People's Republic of China was recognized by Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

countries. Among the first Western countries to recognize China were the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

(on 6 January 1950), Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

(on 17 January 1950) and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

(on 14 February 1950). The first Western country to establish diplomatic ties with China was Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

(on 9 May 1950). Until the early 1970s, the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

government in Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the n ...

was recognized diplomatically by most world powers and held China's permanent seat in the UN Security Council, including its associated veto power

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto pow ...

. After the Beijing government assumed the China seat in 1971 (and the ROC government was expelled), the great majority of nations have switched diplomatic relations from the Republic of China to the People's Republic of China. Japan established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1972, following the Joint Communiqué of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People's Republic of China, and the U.S. did so in 1979. In 2011, the number of countries that had established diplomatic relations with Beijing had risen to 171, while 23 maintained diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (or Taiwan). (See also: Political status of Taiwan

The controversy surrounding the political status of Taiwan or the Taiwan issue is a result of World War II, the second phase of the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949), and the Cold War.

The basic issue hinges on who the islands of Taiwan, Peng ...

)

Mao's foreign policies

In the 1947-1962 era, Mao emphasized the desire for international partnerships, on the one hand to more rapidly develop the economy, and on the other to protect against attacks, especially by the U.S. His numerous alliances, however, all fell apart, including theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

, and Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

. He was unable to organize an anti-American coalition. Mao was only interested in what alliances could do for China, and ignored the needs of the partners. From their point of view China appeared unreliable because of its unstable internal situation, typified by the Great Leap Forward. Furthermore, Mao was insensitive to the fears of alliance partners that China was so big, and so inwardly directed, that their needs would be ignored.

With Mao in overall control and making final decisions, Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 J ...

handled foreign-policy and developed a strong reputation for his diplomatic and negotiating skills. Regardless of those skills, Zhou's bargaining position was undercut by the domestic turmoil initiated by Mao. The Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstruc ...

of 1958-60 was a failed effort to industrialize overnight; it devastated food production

The food industry is a complex, global network of diverse businesses that supplies most of the food consumed by the world's population. The food industry today has become highly diversified, with manufacturing ranging from small, traditiona ...

and led to millions of deaths from famine. Even more disruptive was the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal ...

of 1966–76, which decimated a generation of leadership. When China broke with Russia around 1960, the main cause was Mao's insistence that Moscow had deviated from the true principles of communism. The result was that both Moscow and Beijing sponsored rival Communist parties around the world, which expended much of their energy fighting each other. China's focus especially was on the Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

as China portrayed itself as the legitimate leader of the global battle against imperialism and capitalism.

Soviet Union and Korean War

After its founding, the PRC's foreign policy initially focused on its solidarity with theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

nations, and other communist countries, sealed with, among other agreements, the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance

The Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance ( Russian: Советско-китайский договор о дружбе, союзе и взаимной помощи, ), or Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance fo ...

signed in 1950 to oppose China's chief antagonists, the West and in particular the U.S. The 1950–53 Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

waged by China and its North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

ally against the U.S., South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

, and United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN) forces has long been a reason for bitter feelings. After the conclusion of the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, China sought to balance its identification as a member of the Soviet bloc by establishing friendly relations with Pakistan and other Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

countries, particularly in Southeast Asia.

China's entry into the Korean War was the first of many "preemptive counterattacks". Chinese leaders decided to intervene when they saw their North Korean ally being overwhelmed and no guarantee American forces would stop at the Yalu River

The Yalu River, known by Koreans as the Amrok River or Amnok River, is a river on the border between North Korea and China. Together with the Tumen River to its east, and a small portion of Paektu Mountain, the Yalu forms the border between ...

.

Break with Moscow

By the late 1950s, relations between China and the Soviet Union had become so divisive that in 1960, the Soviets unilaterally withdrew their advisers from China. The two then began to vie for allegiances among thedeveloping world

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

, for China saw itself as a natural champion through its role in the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

and its numerous bilateral and bi-party ties.

In the 1960s, Beijing competed with Moscow for political influence among communist parties and in the developing world generally. In 1962, China had a brief war with India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

over a border dispute. By 1969, relations with Moscow were so tense that fighting erupted along their common border. Following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

and clashes in 1969 on the Sino-Soviet border, Chinese competition with the Soviet Union increasingly reflected concern over China's own strategic position. China then lessened its anti-Western rhetoric and began developing formal diplomatic relations with West European nations.

1980s

Chinese anxiety about Soviet strategic advances was heightened following the Soviet Union's December 1979 invasion ofAfghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

. Sharp differences between China and the Soviet Union persisted over Soviet support for Vietnam's continued occupation of Cambodia, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and Soviet troops along the Sino-Soviet border and in Mongolia