The history of aviation extends for more than two thousand years, from the earliest forms of

aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot a ...

such as

kite

A kite is a tethered heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create lift and drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have a bridle and tail to guide the fac ...

s and attempts at tower jumping to

supersonic and

hypersonic flight by powered,

heavier-than-air

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or by using the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in ...

jets.

Kite flying in

China dates back to several hundred years BC and slowly spread around the world. It is thought to be the earliest example of man-made flight.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

's 15th-century dream of flight found expression in several rational designs, but which relied on poor science.

The discovery of

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

gas in the 18th century led to the invention of the

hydrogen balloon

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

, at almost exactly the same time that the

Montgolfier brothers

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

rediscovered the

hot-air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries p ...

and began manned flights.

Various theories in

mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to object ...

by physicists during the same period of time, notably

fluid dynamics and

Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

, led to the foundation of modern

aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

, most notably by

Sir George Cayley

Sir George Cayley, 6th Baronet (27 December 1773 – 15 December 1857) was an English engineer, inventor, and aviator. He is one of the most important people in the history of aeronautics. Many consider him to be the first true scientific aeri ...

. Balloons, both free-flying and tethered, began to be used for military purposes from the end of the 18th century, with the French government establishing Balloon Companies during the

Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

.

[Hallion (2003)]

Experiments with gliders provided the groundwork for heavier-than-air craft, most notably by

Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making ...

, and by the early 20th century, advances in engine technology and aerodynamics made controlled, powered flight possible for the first time, thanks to the successful efforts of the

Wright brothers. The modern

aeroplane with its characteristic tail was established by 1909 and from then on the history of the aeroplane became tied to the development of more and more powerful engines.

The first great ships of the air were the rigid dirigible balloons pioneered by

Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

, which soon became synonymous with

airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

s and dominated long-distance flight until the 1930s, when large

flying boats became popular. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the flying boats were in their turn replaced by land planes, and the new and immensely powerful

jet engine revolutionised both air travel and

military aviation.

In the latter part of the 20th century, the advent of digital electronics produced great advances in flight instrumentation and "fly-by-wire" systems. The 21st century saw the large-scale use of pilotless drones for military, civilian and leisure use. With digital controls, inherently unstable aircraft such as flying wings became possible.

Etymology

The term aviation, noun of action from stem of Latin avis "bird" with suffix -ation meaning action or progress, was coined in 1863 by French pioneer Guillaume Joseph Gabriel de La Landelle (1812–1886) in "Aviation ou Navigation aérienne sans ballons".

Primitive beginnings

Tower jumping

Since antiquity, there have been stories of men strapping birdlike wings, stiffened cloaks or other devices to themselves and attempting to fly, typically by jumping off a tower. The Greek legend of

Daedalus

In Greek mythology, Daedalus (, ; Greek: Δαίδαλος; Latin: ''Daedalus''; Etruscan: ''Taitale'') was a skillful architect and craftsman, seen as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge and power. He is the father of Icarus, the uncle of Perdix, a ...

and

Icarus is one of the earliest known; others originated from ancient Asia and the European Middle Age. During this early period, the issues of lift, stability and control were not understood, and most attempts ended in serious injury or death.

The

Andalusian scientist

Abbas ibn Firnas

Abu al-Qasim Abbas ibn Firnas ibn Wirdas al-Takurini ( ar, أبو القاسم عباس بن فرناس بن ورداس التاكرني; c. 809/810 – 887 A.D.), also known as Abbas ibn Firnas ( ar, عباس ابن فرناس), Latinized Armen ...

(810–887 AD) is claimed to have made a jump in

Córdoba, Spain

Córdoba (; ),, Arabic: قُرطبة DIN: . or Cordova () in English, is a city in Andalusia, Spain, and the capital of the province of Córdoba. It is the third most populated municipality in Andalusia and the 11th overall in the country.

The ...

, covering his body with

vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

feathers and attaching two wings to his arms.

The 17th-century

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n historian

Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari

Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Maqqarī al-Tilmisānī (or al-Maḳḳarī) (), (1577-1632) was an Algerian scholar, biographer and historian who is best known for his , a compendium of the history of Al-Andalus which provided a basis for the scholar ...

, quoting a poem by

Muhammad I of Córdoba

Muhammad I (822–886) () was the ''Umayyad'' emir of Córdoba from 852 to 886 in the Al-Andalus ( Moorish Iberia).

Biography

Muhammad was born in Córdoba. His reign was marked by several revolts and separatist movements of the Muwallad (Mus ...

's 9th-century court poet Mu'min ibn Said, recounts that Firnas flew some distance before landing with some injuries, attributed to his lacking a tail (as birds use to land).

[ Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", ''Technology and Culture'' 2 (2), pp. 97–111 01/ref> Writing in the 12th century, ]William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as " ...

stated that the 11th-century Benedictine monk Eilmer of Malmesbury

Eilmer of Malmesbury (also known as Oliver due to a scribe's miscopying, or Elmer, or Æthelmær) was an 11th-century English Benedictine monk best known for his early attempt at a gliding flight using wings.

Life

Eilmer was a monk of Malme ...

attached wings to his hands and feet and flew a short distance,Albrecht Berblinger

Albrecht Ludwig Berblinger (24 June 1770 – 28 January 1829), also known as the Tailor of Ulm, is famous for having constructed a working flying machine, presumably a hang glider.

Early life

Berblinger was the seventh child of a poor fa ...

constructed an ornithopter

An ornithopter (from Greek ''ornis, ornith-'' "bird" and ''pteron'' "wing") is an aircraft that flies by flapping its wings. Designers sought to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Though machines may differ in form, ...

and jumped into the Danube at Ulm.

Kites

The

The kite

A kite is a tethered heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create lift and drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have a bridle and tail to guide the fac ...

may have been the first form of man-made aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engine ...

.India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the kite further evolved into the fighter kite

Fighter kites are kites used for the sport of kite fighting. Traditionally most are small, unstable single-line flat kites where line tension alone is used for control, at least part of which is manja, typically glass-coated cotton strands, ...

, which has an abrasive line used to cut down other kites.

Man-carrying kites

Man-carrying kites are believed to have been used extensively in ancient China, for both civil and military purposes and sometimes enforced as a punishment. An early recorded flight was that of the prisoner Yuan Huangtou

Yuan Huangtou (; died in 559) was the son of emperor Yuan Lang of Northern Wei dynasty of China. At that time, paramount general Gao Yang took control of the court of Northern Wei's branch successor state Eastern Wei and set the emperor as a pupp ...

, a Chinese prince, in the 6th century AD. Stories of man-carrying kites also occur in Japan, following the introduction of the kite from China around the seventh century AD. It is said that at one time there was a Japanese law against man-carrying kites.[Pelham, D.; ''The Penguin book of kites'', Penguin (1976)]

Rotor wings

The use of a rotor

Rotor may refer to:

Science and technology

Engineering

* Rotor (electric), the non-stationary part of an alternator or electric motor, operating with a stationary element so called the stator

*Helicopter rotor, the rotary wing(s) of a rotorcraft ...

for vertical flight has existed since 400 BC in the form of the bamboo-copter

The bamboo-copter, also known as the bamboo dragonfly or Chinese top (Chinese ''zhuqingting'' (竹蜻蜓), Japanese ''taketonbo'' ), is a toy helicopter rotor that flies up when its shaft is rapidly spun. This helicopter-like top originated in ...

, an ancient Chinese toy.

Hot air balloons

From ancient times the Chinese have understood that hot air rises and have applied the principle to a type of small hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

called a sky lantern

A sky lantern (), also known as Kǒngmíng lantern (), or Chinese lantern, is a small hot air balloon made of paper, with an opening at the bottom where a small fire is suspended.

In Asia and elsewhere around the world, sky lanterns have bee ...

. A sky lantern consists of a paper balloon under or just inside which a small lamp is placed. Sky lanterns are traditionally launched for pleasure and during festivals. According to Joseph Needham, such lanterns were known in China from the 3rd century BC. Their military use is attributed to the general Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang ( zh, t=諸葛亮 / 诸葛亮) (181 – September 234), courtesy name Kongming, was a Chinese statesman and military strategist. He was chancellor and later regent of the state of Shu Han during the Three Kingdoms period. He is ...

(180–234 AD, honorific title ''Kongming''), who is said to have used them to scare the enemy troops.

There is evidence that the Chinese also "solved the problem of aerial navigation" using balloons, hundreds of years before the 18th century.

Renaissance

Eventually, after Ibn Firnas's construction, some investigators began to discover and define some of the basics of rational aircraft design. Most notable of these was

Eventually, after Ibn Firnas's construction, some investigators began to discover and define some of the basics of rational aircraft design. Most notable of these was Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

, although his work remained unknown until 1797, and so had no influence on developments over the next three hundred years. While his designs are rational, they are not scientific. He particularly underestimated the amount of power that would be needed to propel a flying object,[ basing his designs on the flapping wings of a bird rather than an engine-powered propeller.][ claiming the superiority of the latter owing to its unperforated wing. He analyzed these and anticipating many principles of aerodynamics. He understood that "An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object." ]Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

would not publish his third law of motion until 1687.

From the last years of the 15th century until 1505,[ His early designs were man-powered and included ornithopters and rotorcraft; however he came to realise the impracticality of this and later turned to controlled gliding flight, also sketching some designs powered by a spring.]Codex Atlanticus

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) is a 12-volume, bound set of drawings and writings (in Italian) by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest single set. Its name indicates the large paper used to preserve original Leonardo notebook pages, which was us ...

'', he wrote, "Tomorrow morning, on the second day of January, 1496, I will make the thong and the attempt."[

]

Lighter than air

Beginnings of modern theories

In 1670, Francesco Lana de Terzi

Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631 in Brescia, Lombardy – 22 February 1687, in Brescia, Lombardy) was an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician, naturalist and aeronautics pioneer. Having been professor of physics and mathematics at Brescia, he first ...

published a work that suggested lighter than air flight would be possible by using copper foil spheres that, containing a vacuum, would be lighter than the displaced air to lift an airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

. While theoretically sound, his design was not feasible: the pressure of the surrounding air would crush the spheres. The idea of using a vacuum to produce lift is now known as vacuum airship

A vacuum airship, also known as a vacuum balloon, is a hypothetical airship that is evacuated rather than filled with a lighter-than-air gas such as hydrogen or helium. First proposed by Italian Jesuit priest Francesco Lana de Terzi in 1670, the ...

but remains unfeasible with any current materials

Material is a substance or mixture of substances that constitutes an object. Materials can be pure or impure, living or non-living matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical and chemical properties, or on their geolog ...

.

In 1709, Bartolomeu de Gusmão

Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão (December 1685 – 18 November 1724) was a Brazilian-born Portuguese priest and naturalist, who was a pioneer of lighter-than-air airship design.

Early life

Gusmão was born at Santos, then part of the Portugue ...

presented a petition to King John V of Portugal

Dom John V ( pt, João Francisco António José Bento Bernardo; 22 October 1689 – 31 July 1750), known as the Magnanimous (''o Magnânimo'') and the Portuguese Sun King (''o Rei-Sol Português''), was King of Portugal from 9 December 17 ...

, begging for support for his invention of an airship, in which he expressed the greatest confidence. The public test of the machine, which was set for 24 June 1709, did not take place. According to contemporary reports, however, Gusmão appears to have made several less ambitious experiments with this machine, descending from eminences. It is certain that Gusmão was working on this principle at the public exhibition he gave before the Court on 8 August 1709, in the hall of the Casa da Índia

The Casa da Índia (, English: ''India House'' or ''House of India'') was a Portuguese state-run commercial organization during the Age of Discovery. It regulated international trade and the Portuguese Empire's territories, colonies, and factor ...

in Lisbon, when he propelled a ball to the roof by combustion.

Balloons

1783 was a watershed year for ballooning and aviation. Between 4 June and 1 December, five aviation firsts were achieved in France:

* On 4 June, the Montgolfier brothers

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

demonstrated their unmanned hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

at Annonay, France.

* On 27 August, Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles (November 12, 1746 – April 7, 1823) was a French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.

Charles wrote almost nothing about mathematics, and most of what has been credited to him was due to mistaking ...

and the Robert brothers

Les Frères Robert were two French brothers. Anne-Jean Robert (1758–1820) and Nicolas-Louis Robert (1760–1820) were the engineers who built the world's first hydrogen balloon for professor Jacques Charles, which flew from central Paris o ...

('' Les Freres Robert'') launched the world's first unmanned hydrogen-filled balloon, from the Champ de Mars

The Champ de Mars (; en, Field of Mars) is a large public greenspace in Paris, France, located in the seventh ''arrondissement'', between the Eiffel Tower to the northwest and the École Militaire to the southeast. The park is named after t ...

, Paris.

* On 19 October, the Montgolfiers launched the first manned flight, a tethered balloon with humans on board, at the ''Folie Titon __NOTOC__

Folie or Folies may refer to:

Places

* Condé-Folie, commune in the Picardie region of France

* Fains-la-Folie, commune in the Eure-et-Loir department in north-central France

* Folies, commune in the Somme département in the Picardie reg ...

'' in Paris. The aviators were the scientist Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier () was a French chemistry and physics teacher, and one of the first pioneers of aviation. He made the first manned free balloon flight with François Laurent d'Arlandes on 21 November 1783, in a Montgolfier bal ...

, the manufacture manager Jean-Baptiste Réveillon Jean-Baptiste Réveillon (1725–1811) was a French wallpaper manufacturer. In 1789 Réveillon made a statement on the price of bread that was misinterpreted by the Parisian populace as advocating lower wages. He fled France after his home and his w ...

, and Giroud de Villette.

* On 21 November, the Montgolfiers launched the first free flight with human passengers. King Louis XVI had originally decreed that condemned criminals would be the first pilots, but Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, along with the Marquis François d'Arlandes, successfully petitioned for the honor. They drifted in a balloon-powered by a wood fire.

* On 1 December, Jacques Charles and the Nicolas-Louis Robert launched their manned hydrogen balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace in ...

in Paris, as a crowd of 400,000 witnessed. They ascended to a height of about 5and landed at sunset in Nesles-la-Vallée

Nesles-la-Vallée () is a commune in the Val-d'Oise department in Île-de-France in northern France.

See also

*Communes of the Val-d'Oise department

The following is a list of the 184 communes of the Val-d'Oise department of France.

The co ...

after a flight of 2 hours and 5 minutes, covering 36 km. After Robert alighted Charles decided to ascend alone. This time he ascended rapidly to an altitude of about , where he saw the sun again, suffered extreme pain in his ears, and never flew again.

Ballooning became a major "rage" in Europe in the late 18th century, providing the first detailed understanding of the relationship between altitude and the atmosphere.

Non-steerable balloons were employed during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

by the Union Army Balloon Corps

The Union Army Balloon Corps was a branch of the Union Army during the American Civil War, established by presidential appointee Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. It was organized as a civilian operation, which employed a group of prominent American aeronaut ...

. The young Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

first flew as a balloon passenger with the Union Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

in 1863.

In the early 1900s, ballooning was a popular sport in Britain. These privately owned balloons usually used coal gas as the lifting gas. This has half the lifting power of hydrogen so the balloons had to be larger, however, coal gas was far more readily available and the local gas works sometimes provided a special lightweight formula for ballooning events.

Airships

Airships were originally called "dirigible balloons" and are still sometimes called dirigibles today.

Work on developing a steerable (or dirigible) balloon continued sporadically throughout the 19th century. The first powered, controlled, sustained lighter-than-air flight is believed to have taken place in 1852 when Henri Giffard

Baptiste Jules Henri Jacques Giffard (8 February 182514 April 1882) was a French engineer. In 1852 he invented the steam injector and the powered Giffard dirigible airship.

Career

Giffard was born in Paris in 1825. He invented the injector a ...

flew in France, with a steam engine driven craft.

Another advance was made in 1884, when the first fully controllable free-flight was made in a French Army electric-powered airship, '' La France'', by Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs

Arthur Constantin Krebs (16 November 1850 in Vesoul, France – 22 March 1935 in Quimperlé, France) was a French officer and pioneer in automotive engineering.

Life

Collaborating with Charles Renard, he piloted the first fully controll ...

. The long, airship covered in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8½ horsepower electric motor.

However, these aircraft were generally short-lived and extremely frail. Routine, controlled flights would not occur until the advent of the internal combustion engine (see below.)

The first aircraft to make routine controlled flights were non-rigid airship

A blimp, or non-rigid airship, is an airship (dirigible) without an internal structural framework or a keel. Unlike semi-rigid and rigid airships (e.g. Zeppelins), blimps rely on the pressure of the lifting gas (usually helium, rather than hydr ...

s (sometimes called "blimps".) The most successful early pioneering pilot of this type of aircraft was the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont ( Palmira, 20 July 1873 — Guarujá, 23 July 1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman, inventor, and one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavie ...

who effectively combined a balloon with an internal combustion engine. On 19 October 1901, he flew his airship ''Number 6'' over Paris from the Parc de Saint Cloud around the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "' ...

and back in under 30 minutes to win the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize. Santos-Dumont went on to design and build several aircraft. The subsequent controversy surrounding his and others' competing claims with regard to aircraft overshadowed his great contribution to the development of airships.

At the same time that non-rigid airships were starting to have some success, the first successful rigid airships were also being developed. These would be far more capable than fixed-wing aircraft in terms of pure cargo carrying capacity for decades. Rigid airship design and advancement was pioneered by the German count Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

.

Construction of the first Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

airship began in 1899 in a floating assembly hall on Lake Constance in the Bay of Manzell, Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''K ...

. This was intended to ease the starting procedure, as the hall could easily be aligned with the wind. The prototype airship '' LZ 1'' (LZ for "Luftschiff Zeppelin") had a length of was driven by two Daimler engines and balanced by moving a weight between its two nacelles.

Its first flight, on 2 July 1900, lasted for only 18 minutes, as LZ 1 was forced to land on the lake after the winding mechanism for the balancing weight had broken. Upon repair, the technology proved its potential in subsequent flights, bettering the 6 m/s speed attained by the French airship ''La France'' by 3 m/s, but could not yet convince possible investors. It would be several years before the Count was able to raise enough funds for another try.

German airship passenger service known as DELAG

DELAG, acronym for ''Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft'' (German for "German Airship Travel Corporation"), was the world's first airline to use an aircraft in revenue service. It operated a fleet of zeppelin rigid airships manufacture ...

(Deutsche-Luftschiffahrts AG) was established in 1910.

Although airships were used in both World War I and II, and continue on a limited basis to this day, their development has been largely overshadowed by heavier-than-air craft.

Heavier than air

17th and 18th centuries

Italian inventor Tito Livio Burattini

Tito Livio Burattini ( pl, Tytus Liwiusz Burattini, 8 March 1617 – 17 November 1681) was an inventor, architect, Egyptologist, scientist, instrument-maker, traveller, engineer, and nobleman, who spent his working life in Poland and Lithuania. ...

, invited by the Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

King Władysław IV Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

* ...

to his court in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, built a model aircraft with four fixed glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of glidin ...

wings in 1647. Described as "four pairs of wings attached to an elaborate 'dragon'", it was said to have successfully lifted a cat in 1648 but not Burattini himself.[Qtd. in ] His "Dragon Volant" is considered "the most elaborate and sophisticated aeroplane to be built before the 19th Century".

The first published paper on aviation was "Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air" by Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had a ...

published in 1716. This flying machine consisted of a light frame covered with strong canvas and provided with two large oars or wings moving on a horizontal axis, arranged so that the upstroke met with no resistance while the downstroke provided lifting power. Swedenborg knew that the machine would not fly, but suggested it as a start and was confident that the problem would be solved. He wrote: "It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come someone might know how better to utilize our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest. Yet there are sufficient proofs and examples from nature that such flights can take place without danger, although when the first trials are made you may have to pay for the experience, and not mind an arm or leg". Swedenborg would prove prescient in his observation that a method of powering of an aircraft was one of the critical problems to be overcome.

On 16 May 1793, the Spanish inventor Diego Marín Aguilera

Diego Marín Aguilera (1757–1799) was a Spanish inventor who was an early aviation pioneer.

Early life

Born in Coruña del Conde, Marín became the head of his household after his father died and had to take care of his seven siblings. He wo ...

managed to cross the river Arandilla in Coruña del Conde, Castile, flying 300 – 400 m, with a flying machine.

19th century

Balloon jumping replaced tower jumping, also demonstrating with typically fatal results that man-power and flapping wings were useless in achieving flight. At the same time scientific study of heavier-than-air flight began in earnest. In 1801, the French officer André Guillaume Resnier de Goué managed a 300-metre glide by starting from the top of the city walls of Angoulême and broke only one leg on arrival. In 1837 French mathematician and brigadier general Isidore Didion stated, "Aviation will be successful only if one finds an engine whose ratio with the weight of the device to be supported will be larger than current steam machines or the strength developed by humans or most of the animals".

Sir George Cayley and the first modern aircraft

Sir George Cayley

Sir George Cayley, 6th Baronet (27 December 1773 – 15 December 1857) was an English engineer, inventor, and aviator. He is one of the most important people in the history of aeronautics. Many consider him to be the first true scientific aeri ...

was first called the "father of the aeroplane" in 1846. During the last years of the previous century he had begun the first rigorous study of the physics of flight and would later design the first modern heavier-than-air craft. Among his many achievements, his most important contributions to aeronautics include:

* Clarifying our ideas and laying down the principles of heavier-than-air flight.

* Reaching a scientific understanding of the principles of bird flight.

* Conducting scientific aerodynamic experiments demonstrating drag and streamlining, movement of the centre of pressure, and the increase in lift from curving the wing surface.

* Defining the modern aeroplane configuration comprising a fixed-wing, fuselage and tail assembly.

* Demonstrations of manned, gliding flight.

* Setting out the principles of power-to-weight ratio in sustaining flight.

Cayley's first innovation was to study the basic science of lift by adopting the whirling arm test rig for use in aircraft research and using simple aerodynamic models on the arm, rather than attempting to fly a model of a complete design.

In 1799, he set down the concept of the modern aeroplane as a fixed-wing

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying machine, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using wings that generate lift caused by the aircraft's forward airspeed and the shape of the wings. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinct ...

flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control.

In 1804, Cayley constructed a model glider which was the first modern heavier-than-air flying machine, having the layout of a conventional modern aircraft with an inclined wing towards the front and adjustable tail at the back with both tailplane and fin. A movable weight allowed adjustment of the model's centre of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

.

In 1809, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).

In 1809, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).[''Cayley, George''. "On Aerial Navigation]

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

''Nicholson's Journal of Natural Philosophy'', 1809–1810. (Via NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

)

Raw text

. Retrieved: 30 May 2010. In it he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem, "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air". He identified the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: ''thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that sys ...

'', ''lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

'', '' drag'' and ''weight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force acting on the object due to gravity.

Some standard textbooks define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others define weight as a scalar qua ...

'' and distinguished stability and control in his designs. He also identified and described the importance of the cambered aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine. ...

, dihedral, diagonal bracing and drag reduction, and contributed to the understanding and design of ornithopter

An ornithopter (from Greek ''ornis, ornith-'' "bird" and ''pteron'' "wing") is an aircraft that flies by flapping its wings. Designers sought to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Though machines may differ in form, ...

s and parachutes.

In 1848, he had progressed far enough to construct a glider in the form of a triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The triplane arrangement m ...

large and safe enough to carry a child. A local boy was chosen but his name is not known.

He went on to publish in 1852 the design for a full-size manned glider or "governable parachute" to be launched from a balloon and then to construct a version capable of launching from the top of a hill, which carried the first adult aviator across Brompton Dale in 1853.

Minor inventions included the rubber-powered motor, which provided a reliable power source for research models. By 1808, he had even re-invented the wheel, devising the tension-spoked wheel

Wire wheels, wire-spoked wheels, tension-spoked wheels, or "suspension" wheels are wheels whose rims connect to their hubs by wire spokes. Although these wires are generally stiffer than a typical wire rope, they function mechanically the same ...

in which all compression loads are carried by the rim, allowing a lightweight undercarriage.[Pritchard, J. Laurence]

Summary of First Cayley Memorial Lecture at the Brough Branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society

''Flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

'' number 2390 volume 66 page 702, 12 November 1954. Retrieved: 29 May 2010. "In thinking of how to construct the lightest possible wheel for aerial navigation cars, an entirely new mode of manufacturing this most useful part of locomotive machines occurred to me: vide, to do away with wooden spokes altogether, and refer the whole firmness of the wheel to the strength of the rim only, by the intervention of tight cording."

Age of steam

Drawing directly from Cayley's work, Henson's 1842 design for an aerial steam carriage broke new ground. Although only a design, it was the first in history for a propeller-driven fixed-wing aircraft.

1866 saw the founding of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain and two years later the world's first aeronautical exhibition was held at the

1866 saw the founding of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain and two years later the world's first aeronautical exhibition was held at the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

, London, where John Stringfellow was awarded a £100 prize for the steam engine with the best power-to-weight ratio.[Jarrett 2002, p. 53.][Stokes 2002, pp. 163–166, 167–168.] In 1848, Stringfellow achieved the first powered flight using an unmanned wingspan steam-powered monoplane built in a disused lace factory in Chard, Somerset. Employing two contra-rotating propellers on the first attempt, made indoors, the machine flew ten feet before becoming destabilised, damaging the craft. The second attempt was more successful, the machine leaving a guidewire to fly freely, achieving thirty yards of straight and level powered flight. Francis Herbert Wenham __NOTOC__

Francis Herbert Wenham (1824, Kensington – 1908) was a British marine engineer who studied the problem of human flight and wrote a perceptive and influential academic paper, which he presented to the first meeting of the Royal Aeronaut ...

presented the first paper to the newly formed Aeronautical Society (later the Royal Aeronautical Society

The Royal Aeronautical Society, also known as the RAeS, is a British multi-disciplinary professional institution dedicated to the global aerospace community. Founded in 1866, it is the oldest aeronautical society in the world. Members, Fellows, ...

), ''On Aerial Locomotion''. He advanced Cayley's work on cambered wings, making important findings. To test his ideas, from 1858 he had constructed several gliders, both manned and unmanned, and with up to five stacked wings. He realised that long, thin wings are better than bat-like ones because they have more leading edge for their area. Today this relationship is known as the aspect ratio of a wing.

The latter part of the 19th century became a period of intense study, characterized by the "gentleman scientist

An independent scientist (historically also known as gentleman scientist) is a financially independent scientist who pursues scientific study without direct affiliation to a public institution such as a university or government-run research and ...

s" who represented most research efforts until the 20th century. Among them was the British scientist-philosopher and inventor Matthew Piers Watt Boulton

Matthew Piers Watt Boulton (22 September 1820 – 30 June 1894), also published under the pseudonym M. P. W. Bolton, was a British classicist, elected member of the UK's Metaphysical Society, an amateur scientist and an inventor, bes ...

, who studied lateral flight control and was the first to patent an aileron control system in 1868.wind tunnel

Wind tunnels are large tubes with air blowing through them which are used to replicate the interaction between air and an object flying through the air or moving along the ground. Researchers use wind tunnels to learn more about how an aircraft ...

using a fan, driven by a steam engine, to propel air down a tube to the model.

Meanwhile, the British advances had galvanised French researchers. In 1857,

Meanwhile, the British advances had galvanised French researchers. In 1857, Félix du Temple

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places

* Arabia Felix is the ancient Latin name of Yemen

* Felix, Spain, a municipality of the province Almería, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, ...

proposed a monoplane with a tailplane and retractable undercarriage. Developing his ideas with a model powered first by clockwork and later by steam, he eventually achieved a short hop with a full-size manned craft in 1874. It achieved lift-off under its own power after launching from a ramp, glided for a short time and returned safely to the ground, making it the first successful powered glide in history.

In 1865, Louis Pierre Mouillard

Louis Pierre Mouillard (September 30, 1834 – September 20, 1897) was a French artist and innovator who worked on human mechanical flight in the second half of the 19th century. He based much of his work on the investigation of birds in Algeri ...

published an influential book The Empire Of The Air (''l'Empire de l'Air'').

In 1856, Frenchman

In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris

Jean Marie Le Bris (March 25, 1817, Concarneau – February 17, 1872, Douarnenez) was a French aviator, born in Concarneau, Brittany who built two glider aircraft and performed at least one flight on board of his first machine in late 1856. His ...

made the first flight higher than his point of departure, by having his glider "''L'Albatros artificiel'' pulled by a horse on a beach. He reportedly achieved a height of 100 meters, over a distance of 200 meters.

Alphonse Pénaud

Alphonse Pénaud (31 May 1850 – 22 October 1880), was a 19th-century French pioneer of aviation design and engineering. He was the originator of the use of twisted rubber to power model aircraft, and his 1871 model airplane, which he called ...

, a Frenchman, advanced the theory of wing contours and aerodynamics and constructed successful models of aeroplanes, helicopters and ornithopters. In 1871 he flew the first aerodynamically stable fixed-wing aeroplane, a model monoplane he called the "Planophore", a distance of . Pénaud's model incorporated several of Cayley's discoveries, including the use of a tail, wing dihedral for inherent stability, and rubber power. The planophore also had longitudinal stability, being trimmed such that the tailplane was set at a smaller angle of incidence than the wings, an original and important contribution to the theory of aeronautics. Pénaud's later project for an amphibian aeroplane, although never built, incorporated other modern features. A tailless monoplane with a single vertical fin and twin tractor propellers, it also featured hinged rear elevator and rudder surfaces, retractable undercarriage and a fully enclosed, instrumented cockpit.

Equally authoritative as a theorist was Pénaud's fellow countryman Victor Tatin. In 1879, he flew a model which, like Pénaud's project, was a monoplane with twin tractor propellers but also had a separate horizontal tail. It was powered by compressed air. Flown tethered to a pole, this was the first model to take off under its own power.

In 1884, Alexandre Goupil published his work ''La Locomotion Aérienne'' (''Aerial Locomotion''), although the flying machine he later constructed failed to fly.

Equally authoritative as a theorist was Pénaud's fellow countryman Victor Tatin. In 1879, he flew a model which, like Pénaud's project, was a monoplane with twin tractor propellers but also had a separate horizontal tail. It was powered by compressed air. Flown tethered to a pole, this was the first model to take off under its own power.

In 1884, Alexandre Goupil published his work ''La Locomotion Aérienne'' (''Aerial Locomotion''), although the flying machine he later constructed failed to fly.

In 1890, the French engineer

In 1890, the French engineer Clément Ader

Clément Ader (2 April 1841 – 3 May 1925) was a French inventor and engineer who was born near Toulouse in Muret, Haute-Garonne, and died in Toulouse. He is remembered primarily for his pioneering work in aviation. In 1870 he was also one ...

completed the first of three steam-driven flying machines, the Éole. On 9 October 1890, Ader made an uncontrolled hop of around ; this was the first manned airplane to take off under its own power. His Avion III

The ''Avion III'' (sometimes referred to as the ''Aquilon'' or the ''Éole III'') was a steam-powered aircraft built by Clément Ader between 1892 and 1897, financed by the French War Office.

Retaining the same bat-like configuration of the ...

of 1897, notable only for having twin steam engines, failed to fly:[Jarrett 2002, p. 87.] Ader would later claim success and was not debunked until 1910 when the French Army published its report on his attempt.

Sir

Sir Hiram Maxim

Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim (5 February 1840 – 24 November 1916) was an American- British inventor best known as the creator of the first automatic machine gun, the Maxim gun. Maxim held patents on numerous mechanical devices such as hair-curl ...

was an American engineer who had moved to England. He built his own whirling arm rig and wind tunnel and constructed a large machine with a wingspan of , a length of , fore and aft horizontal surfaces and a crew of three. Twin propellers were powered by two lightweight compound steam engines each delivering . The overall weight was . It was intended as a test rig to investigate aerodynamic lift: lacking flight controls it ran on rails, with a second set of rails above the wheels to restrain it. Completed in 1894, on its third run it broke from the rail, became airborne for about 200 yards at two to three feet of altitude and was badly damaged upon falling back to the ground. It was subsequently repaired, but Maxim abandoned his experiments shortly afterwards.

Learning to glide; Otto Lilienthal and the first human flights

Around the last decade of the 19th century, a number of key figures were refining and defining the modern aeroplane. Lacking a suitable engine, aircraft work focused on stability and control in gliding flight. In 1879, Biot constructed a bird-like glider with the help of Massia and flew in it briefly. It is preserved in the Musee de l'Air, France, and is claimed to be the earliest man-carrying flying machine still in existence.

The Englishman

Around the last decade of the 19th century, a number of key figures were refining and defining the modern aeroplane. Lacking a suitable engine, aircraft work focused on stability and control in gliding flight. In 1879, Biot constructed a bird-like glider with the help of Massia and flew in it briefly. It is preserved in the Musee de l'Air, France, and is claimed to be the earliest man-carrying flying machine still in existence.

The Englishman Horatio Phillips

Horatio Frederick Phillips (1845 – 1924) was an English aviation pioneer, born in Streatham, Surrey. He was famous for building multiplane flying machines with many more sets of lifting surfaces than are normal on modern aircraft. However he ...

made key contributions to aerodynamics. He conducted extensive wind tunnel research on aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine. ...

sections, proving the principles of aerodynamic lift foreseen by Cayley and Wenham. His findings underpin all modern aerofoil design. Between 1883 and 1886, the American John Joseph Montgomery

John Joseph Montgomery (February 15, 1858 – October 31, 1911) was an American inventor, physicist, engineer, and professor at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, California, who is best known for his invention of controlled heavier-than-a ...

developed a series of three manned gliders, before conducting his own independent investigations into aerodynamics and circulation of lift.

Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making ...

became known as the "Glider King" or "Flying Man" of Germany. He duplicated Wenham's work and greatly expanded on it in 1884, publishing his research in 1889 as ''Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation'' (''Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst''), which is seen as one of the most important works in aviation history. He also produced a series of hang glider

Hang gliding is an air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised foot-launched heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium alloy or composite frame cover ...

s, including bat-wing, monoplane and biplane forms, such as the Derwitzer Glider

The Derwitzer Glider was a glider that was developed by Otto Lilienthal, so named because it was tested near Derwitz in Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the s ...

and Normal soaring apparatus, which is considered to be the first air plane in series production, making the ''Maschinenfabrik Otto Lilienthal'' the first air plane production company in the world.

Starting in 1891, he became the first person to make controlled untethered glides routinely, and the first to be photographed flying a heavier-than-air machine, stimulating interest around the world. Lilienthal's work led to him developing the concept of the modern wing. His flight attempts in the year 1891 are seen as the beginning of human flight and because of that he is often referred to as either the "father of aviation" or "father of flight".

He rigorously documented his work, including photographs, and for this reason is one of the best known of the early pioneers. Lilienthal made over 2,000 glides until his death in 1896 from injuries sustained in a glider crash.

Picking up where Lilienthal left off, Octave Chanute

Octave Chanute (February 18, 1832 – November 23, 1910) was a French-American civil engineer and aviation pioneer. He provided many budding enthusiasts, including the Wright brothers, with help and advice, and helped to publicize their flying ...

took up aircraft design after an early retirement, and funded the development of several gliders. In the summer of 1896, his team flew several of their designs eventually deciding that the best was a biplane design. Like Lilienthal, he documented and photographed his work.

In Britain Percy Pilcher

Percy Sinclair Pilcher (16 January 1867 – 2 October 1899) was a British inventor and pioneer aviator who was his country's foremost experimenter in unpowered flight near the end of the nineteenth century.

After corresponding with Otto Lilien ...

, who had worked for Maxim, built and successfully flew several gliders during the mid to late 1890s.

The invention of the box kite

A box kite is a high performance kite, noted for developing relatively high lift; it is a type within the family of cellular kites. The typical design has four parallel struts. The box is made rigid with diagonal crossed struts. There are two s ...

during this period by the Australian Lawrence Hargrave

Lawrence Hargrave, MRAeS, (29 January 18506 July 1915) was a British-born Australian engineer, explorer, astronomer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer.

Biography

Lawrence Hargrave was born in Greenwich, England, the second son of John Fletc ...

would lead to the development of the practical biplane. In 1894, Hargrave linked four of his kites together, added a sling seat, and was the first to obtain lift with a heavier than air aircraft, when he flew up . Later pioneers of manned kite flying included Samuel Franklin Cody

Samuel Franklin Cowdery (later known as Samuel Franklin Cody; 6 March 1867 – 7 August 1913, born Davenport, Iowa, USA)) was a Wild West showman and early pioneer of manned flight. He is most famous for his work on the large kites known a ...

in England and Captain Génie Saconney in France.

Frost

William Frost from Pembrokeshire, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

started his project in 1880 and after 16 years, he designed a flying machine and in 1894 won a patent for a "Frost Aircraft Glider".

Spectators witnessed the craft fly at Saundersfoot in 1896, traveling 500 yards before colliding with a tree and falling in a field.

Langley

After a distinguished career in

After a distinguished career in astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

and shortly before becoming Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

, Samuel Pierpont Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley (August 22, 1834 – February 27, 1906) was an American aviation pioneer, astronomer and physicist who invented the bolometer. He was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a professor of astronomy a ...

started a serious investigation into aerodynamics at what is today the University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a public state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The university is composed of 17 undergraduate and graduate schools and colleges at its urban Pittsburgh campus, home to the univers ...

. In 1891, he published ''Experiments in Aerodynamics'' detailing his research, and then turned to building his designs. He hoped to achieve automatic aerodynamic stability, so he gave little consideration to in-flight control.Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, the U.S. government granted him $50,000 to develop a man-carrying flying machine for aerial reconnaissance. Langley planned on building a scaled-up version known as the Aerodrome A, and started with the smaller Quarter-scale Aerodrome, which flew twice on 18 June 1901, and then again with a newer and more powerful engine in 1903.

With the basic design apparently successfully tested, he then turned to the problem of a suitable engine. He contracted Stephen Balzer to build one, but was disappointed when it delivered only instead of the he expected. Langley's assistant, Charles M. Manly

Charles Matthews Manly (1876–1927) was an American engineer.

Manly helped Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Pierpont Langley build The Great Aerodrome, which was intended to be a manned, powered, winged flying machine. Manly made major ...

, then reworked the design into a five-cylinder water-cooled radial that delivered at 950 rpm, a feat that took years to duplicate. Now with both power and a design, Langley put the two together with great hopes.

To his dismay, the resulting aircraft proved to be too fragile. Simply scaling up the original small models resulted in a design that was too weak to hold itself together. Two launches in late 1903 both ended with the ''Aerodrome'' immediately crashing into the water. The pilot, Manly, was rescued each time. Also, the aircraft's control system was inadequate to allow quick pilot responses, and it had no method of lateral control, and the ''Aerodrome''s aerial stability was marginal.Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

made 93 modifications to the ''Aerodrome'' and flew this very different aircraft in 1914.

Whitehead

Gustave Weißkopf was a German who emigrated to the U.S., where he soon changed his name to Whitehead. From 1897 to 1915, he designed and built early flying machines and engines. On 14 August 1901, two and a half years before the Wright Brothers' flight, he claimed to have carried out a controlled, powered flight in his Number 21 monoplane at Fairfield, Connecticut. The flight was reported in the ''Bridgeport Sunday Herald'' local newspaper. About 30 years later, several people questioned by a researcher claimed to have seen that or other Whitehead flights.

In March 2013, ''Jane's All the World's Aircraft

''Jane's All the World's Aircraft'' (now stylized Janes) is an aviation annual publication founded by John Frederick Thomas Jane in 1909. Long issued by Sampson Low, Marston in Britain (with various publishers in the U.S.), it has been published b ...

'', an authoritative source for contemporary aviation, published an editorial which accepted Whitehead's flight as the first manned, powered, controlled flight of a heavier-than-air craft. The Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

(custodians of the original ''Wright Flyer

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown b ...

'') and many aviation historians continue to maintain that Whitehead did not fly as suggested.

Pearse

Richard Pearse was a New Zealand farmer and inventor who performed pioneering aviation experiments. Witnesses interviewed many years afterward claimed that Pearse flew and landed a powered heavier-than-air machine on 31 March 1903, nine months before the Wright brothers flew.

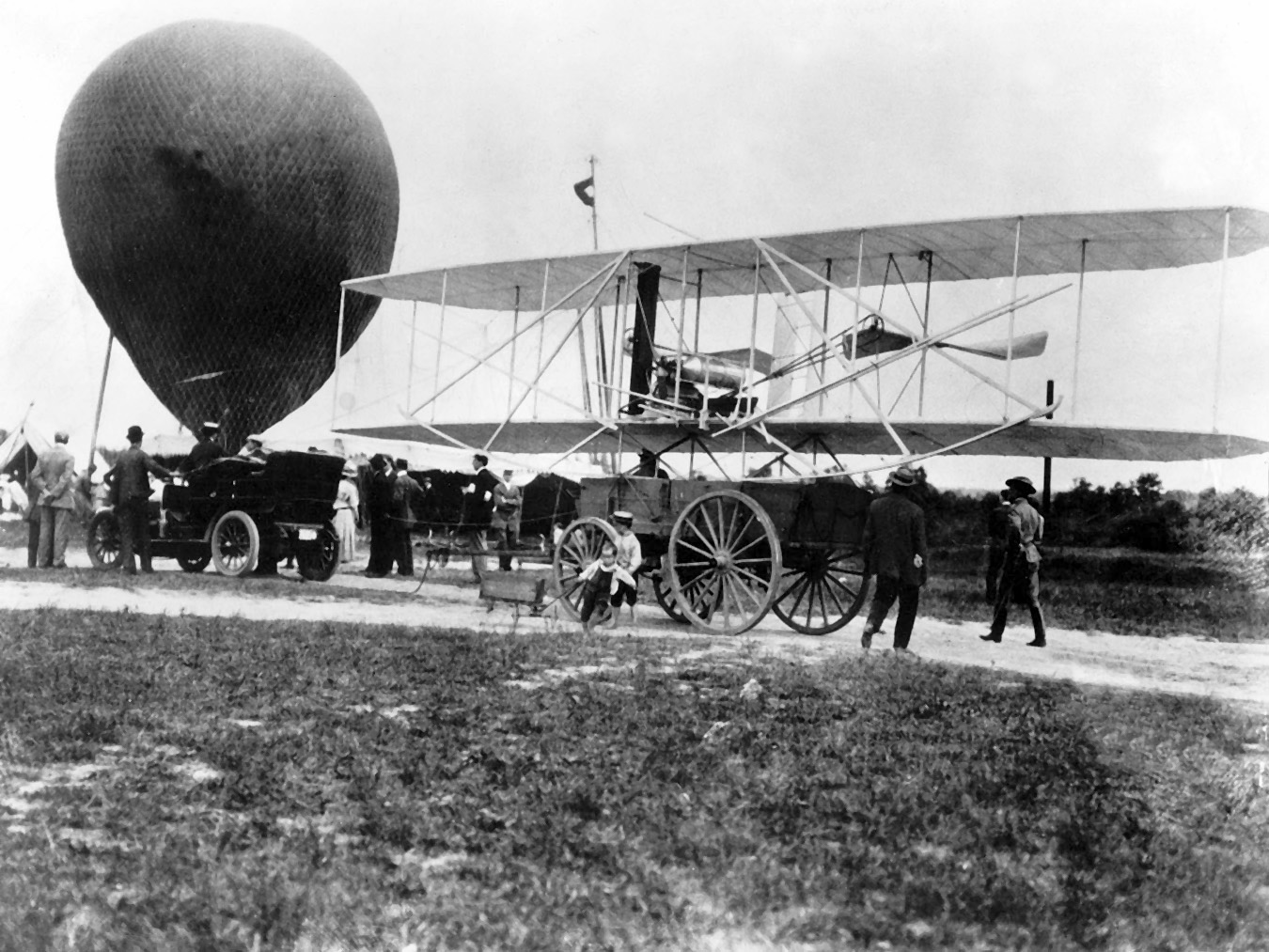

Wright brothers

Using a methodical approach and concentrating on the controllability of the aircraft, the brothers built and tested a series of kite and glider designs from 1898 to 1902 before attempting to build a powered design. The gliders worked, but not as well as the Wrights had expected based on the experiments and writings of their predecessors. Their first full-size glider, launched in 1900, had only about half the lift they anticipated. Their second glider, built the following year, performed even more poorly. Rather than giving up, the Wrights constructed their own

Using a methodical approach and concentrating on the controllability of the aircraft, the brothers built and tested a series of kite and glider designs from 1898 to 1902 before attempting to build a powered design. The gliders worked, but not as well as the Wrights had expected based on the experiments and writings of their predecessors. Their first full-size glider, launched in 1900, had only about half the lift they anticipated. Their second glider, built the following year, performed even more poorly. Rather than giving up, the Wrights constructed their own wind tunnel

Wind tunnels are large tubes with air blowing through them which are used to replicate the interaction between air and an object flying through the air or moving along the ground. Researchers use wind tunnels to learn more about how an aircraft ...

and created a number of sophisticated devices to measure lift and drag on the 200 wing designs they tested.Wright Flyer

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown b ...

'', but also helped advance the science of aeronautical engineering.

The Wrights appear to be the first to make serious studied attempts to simultaneously solve the power and control problems. Both problems proved difficult, but they never lost interest. They solved the control problem by inventing wing warping

Wing warping was an early system for lateral (roll) control of a fixed-wing aircraft. The technique, used and patented by the Wright brothers, consisted of a system of pulleys and cables to twist the trailing edges of the wings in opposite direc ...

for roll

Roll or Rolls may refer to:

Movement about the longitudinal axis

* Roll angle (or roll rotation), one of the 3 angular degrees of freedom of any stiff body (for example a vehicle), describing motion about the longitudinal axis

** Roll (aviation) ...

control, combined with simultaneous yaw control with a steerable rear rudder. Almost as an afterthought, they designed and built a low-powered internal combustion engine. They also designed and carved wooden propellers that were more efficient than any before, enabling them to gain adequate performance from their low engine power. Although wing-warping as a means of lateral control was used only briefly during the early history of aviation, the principle of combining lateral control in combination with a rudder was a key advance in aircraft control. While many aviation pioneers appeared to leave safety largely to chance, the Wrights' design was greatly influenced by the need to teach themselves to fly without unreasonable risk to life and limb, by surviving crashes. This emphasis, as well as low engine power, was the reason for low flying speed and for taking off in a headwind. Performance, rather than safety, was the reason for the rear-heavy design because the canard could not be highly loaded; anhedral wings were less affected by crosswinds and were consistent with the low yaw stability.

According to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

and Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the Wrights made the first sustained, controlled, powered heavier-than-air manned flight at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina

Kill Devil Hills is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 7,633 at the 2020 census, up from 6,683 in 2010. It is the most populous settlement in both Dare County and on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The ...

, four miles (8 km) south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina

Kitty Hawk is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, United States, and is a part of what is known as North Carolina's Outer Banks. The population was 3,708 at the 2020 Census. It was established in the early 18th century as Chickahawk.

History ...

on 17 December 1903.Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater D ...

in 1904–05. In May 1904 they introduced the Flyer II, a heavier and improved version of the original Flyer. On 23 June 1905, they first flew a third machine, the Flyer III. After a severe crash on 14 July 1905, they rebuilt the Flyer III and made important design changes. They almost doubled the size of the elevator

An elevator or lift is a cable-assisted, hydraulic cylinder-assisted, or roller-track assisted machine that vertically transports people or freight between floors, levels, or decks of a building, vessel, or other structure. They a ...

and rudder and moved them about twice the distance from the wings. They added two fixed vertical vanes (called "blinkers") between the elevators and gave the wings a very slight dihedral. They disconnected the rudder from the wing-warping control, and as in all future aircraft, placed it on a separate control handle. When flights resumed the results were immediate. The serious pitch instability that hampered Flyers I and II was significantly reduced, so repeated minor crashes were eliminated. Flights with the redesigned Flyer III started lasting over 10 minutes, then 20, then 30. Flyer III became the first practical aircraft (though without wheels and needing a launching device), flying consistently under full control and bringing its pilot back to the starting point safely and landing without damage. On 5 October 1905, Wilbur flew in 39 minutes 23 seconds."

According to the April 1907 issue of the ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

'' magazine, the Wright brothers seemed to have the most advanced knowledge of heavier-than-air navigation at the time. However, the same magazine issue also claimed that no public flight had been made in the United States before its April 1907 issue. Hence, they devised the Scientific American Aeronautic Trophy in order to encourage the development of a heavier-than-air flying machine.

Pioneer Era (1903–1914)

This period saw the development of practical aeroplanes and airships and their early application, alongside balloons and kites, for private, sport and military use.

Pioneers in Europe

Although full details of the Wright Brothers' system of flight control had been published in l'Aerophile in January 1906, the importance of this advance was not recognised, and European experimenters generally concentrated on attempting to produce inherently stable machines.

Short powered flights were performed in France by Romanian engineer

Although full details of the Wright Brothers' system of flight control had been published in l'Aerophile in January 1906, the importance of this advance was not recognised, and European experimenters generally concentrated on attempting to produce inherently stable machines.

Short powered flights were performed in France by Romanian engineer Traian Vuia

Traian Vuia or Trajan Vuia (; August 17, 1872 – September 3, 1950) was a Romanian inventor and aviation pioneer who designed, built and tested the first tractor monoplane. He was the first to demonstrate that a flying machine could rise into the ...

on 18 March and 19 August 1906 when he flew 12 and 24 meters, respectively, in a self-designed, fully self-propelled, fixed-wing aircraft, that possessed a fully wheeled undercarriage.Jacob Ellehammer

Jacob Christian Hansen-Ellehammer (14 June 1871 – 20 May 1946) was a Danish watchmaker and inventor born in Bakkebølle, Denmark. He is remembered chiefly for his contributions to powered flight.

Following the end of his apprenticeship as a ...

who built a monoplane which he tested with a tether in Denmark on 12 September 1906, flying 42 meters.

On 13 September 1906, a day after Ellehammer's tethered flight and three years after the Wright Brothers' flight, the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont ( Palmira, 20 July 1873 — Guarujá, 23 July 1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman, inventor, and one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavie ...

made a public flight in Paris with the 14-bis

The ''14-bis'' (french: Quatorze-bis), (), also known as ("bird of prey" in French), was a pioneer era, canard-style biplane designed and built by Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont. In 1906, near Paris, the ''14-bis'' made a m ...

, also known as ''Oiseau de proie'' (French for "bird of prey"). This was of canard configuration with pronounced wing dihedral, and covered a distance of on the grounds of the Chateau de Bagatelle in Paris' Bois de Boulogne

The Bois de Boulogne (, "Boulogne woodland") is a large public park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine. The land was ceded to the city of Paris by t ...

before a large crowd of witnesses. This well-documented event was the first flight verified by the Aéro-Club de France

The Aéro-Club de France () was founded as the Aéro-Club on 20 October 1898 as a society 'to encourage aerial locomotion' by Ernest Archdeacon, Léon Serpollet, Henri de la Valette, Jules Verne and his wife, André Michelin, Albert de Dion, ...

of a powered heavier-than-air machine in Europe and won the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first officially observed flight greater than . On 12 November 1906, Santos-Dumont set the first world record recognized by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale by flying in 21.5 seconds. Only one more brief flight was made by the 14-bis in March 1907, after which it was abandoned.

In March 1907, Gabriel Voisin

Gabriel Voisin (5 February 1880 – 25 December 1973) was a French aviation pioneer and the creator of Europe's first manned, engine-powered, heavier-than-air aircraft capable of a sustained (1 km), circular, controlled flight, which was made ...

flew the first example of his Voisin biplane. On 13 January 1908, a second example of the type was flown by Henri Farman

Henri Farman (26 May 1874– 17 July 1958) was a British-French aviator and aircraft designer and manufacturer with his brother Maurice Farman. Before dedicating himself to aviation he gained fame as a sportsman, specifically in cycling and moto ...

to win the Deutsch-Archdeacon ''Grand Prix d'Aviation'' prize for a flight in which the aircraft flew a distance of more than a kilometer and landed at the point where it had taken off. The flight lasted 1 minute and 28 seconds.

Flight as an established technology

Santos-Dumont later added ailerons between the wings in an effort to gain more lateral stability. His final design, first flown in 1907, was the series of Demoiselle monoplanes (Nos. 19 to 22). The ''Demoiselle No 19'' could be constructed in only 15 days and became the world's first series production aircraft. The Demoiselle achieved 120 km/h.

Santos-Dumont later added ailerons between the wings in an effort to gain more lateral stability. His final design, first flown in 1907, was the series of Demoiselle monoplanes (Nos. 19 to 22). The ''Demoiselle No 19'' could be constructed in only 15 days and became the world's first series production aircraft. The Demoiselle achieved 120 km/h.[Hartmann, Gérard]

"Clément-Bayard, sans peur et sans reproche" (French).