Catholic dogmatic theology can be defined as "a special branch of theology, the object of which is to present a scientific and connected view of the accepted doctrines of the Christian faith."

/ref>

Definition

According to Joseph Pohle, writing in the ''Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'' (also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedia'') i ...

'', "theology comprehends all those and only those doctrines which are to be found in the sources of faith, namely Scripture and Tradition...For, just as the Bible,...was written under the immediate inspiration of the Holy pirit so Tradition was, and is, guided in a special manner by God, Who preserves it from being curtailed, mutilated, or falsified."[Pohle, Joseph. "Dogmatic Theology." The Catholic Encyclopedia]

Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 8 May 2022 The scientific character of dogmatic theology does not rest so much on the exactness of its exegetical and historical proofs as on the philosophical grasp of the content of dogma.[

The functions of dogmatic theology are twofold: first, to establish what constitutes a doctrine of the Christian faith, and to elucidate it in both its religious and its philosophical aspects; secondly, to connect the individual doctrines into a system.][ “In current Catholic usage, the term ‘dogma’ means a divinely revealed truth, proclaimed as such by the infallible teaching authority of the Church, and hence binding on all the faithful without exception, now and forever."

]

Subjects

Dogmatic theology begins with the doctrine of God, whose existence, essence, and attributes are to be investigated. A philosophical understanding of the dogma of the Trinity was attempted by the Fathers. The theologian investigates the activity of creation. As the beginning of the world supposes creation out of nothing, so its continuation supposes Divine conservation, which is nothing less than a continued creation. However, God's creative activity is not thereby exhausted.[ The topics of Original Sin and ]Angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles inclu ...

ology come under Creation.

The subject of Redemption includes Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

, Soteriology, Mariology

Mariology is the theological study of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Mariology seeks to relate doctrine or dogma about Mary to other doctrines of the faith, such as those concerning Jesus and notions about redemption, intercession and grace. Chri ...

. The Redeemer's activity as Mediator stands out most prominently in His triple office of high priest, prophet, and king. For the most part, dogmatic theologians prefer to treat Mariology and the veneration paid to relics and images under Eschatology

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that negati ...

, together with the Communion of Saints.[

]

History

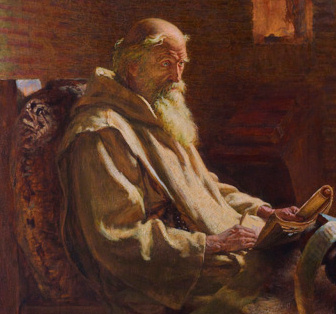

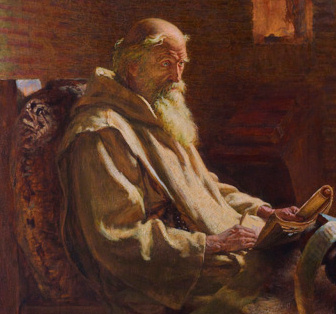

Patristic period (about A.D. 100–800)

At first, Dogmatic theology comprised apologetics, dogmatic and moral theology, and canon law.[ The Fathers of the Church are honoured by the Church as her principal theologians. It was not so much in the ]catechetical

Catechesis (; from Greek language, Greek: , "instruction by word of mouth", generally "instruction") is basic Christian religious education of children and adults, often from a catechism book. It started as education of Conversion to Christian ...

schools of Alexandria, Antioch, and Edessa as in the struggle with the great heresies of the age that patristic theology developed. This serves to explain the character of the patristic literature, which is apologetical and polemical, parenetical and ascetic. It was not the intention of the Fathers to give a systematic treatment of theology. It may be said in general that the apologetic style predominated up to the time of Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

.[

Christian writers had to explain the truths of ]natural religion

Natural religion most frequently means the "religion of nature", in which God, the soul, spirits, and all objects of the supernatural are considered as part of nature and not separate from it. Conversely, it is also used in philosophy to describe s ...

, such as God, the soul, creation, immortality, and freedom of the will; at the same time they had to defend the chief mysteries of the Christian faith. The efforts of the Fathers to define and combat heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

brought writings against Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people ...

, Manichæism, and Priscillianism

Priscillianism was a Christian sect developed in the Iberian Peninsula under the Roman Empire in the 4th century by Priscillian. It is derived from the Gnostic doctrines taught by Marcus, an Egyptian from Memphis. Priscillianism was later cons ...

. Those who wrote against pagan polytheism include: Justin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

, Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Cr ...

, and Eusebius of Cæsarea. Prominent writers against the practices of Judaizing Christians were: Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome (, ; c. 170 – c. 235 AD) was one of the most important second-third century Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communities include Rome, Palestin ...

, Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis ( grc-gre, Ἐπιφάνιος; c. 310–320 – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He g ...

, and Chrysostom. At the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

, the Church took steps to define revealed doctrine more precisely in response to a challenge from a heretical theology."

Eastern Christians in this dispute on the Trinity and Christology included: the Alexandrines, and Didymus the Blind

Didymus the Blind (alternatively spelled Dedimus or Didymous) (c. 313398) was a Christian theologian in the Church of Alexandria, where he taught for about half a century. He was a student of Origen, and, after the Second Council of Constantinop ...

; Athanasius and the three Cappadocians; Cyril of Alexandria and Leontius of Byzantium Leontius of Byzantium (485–543) was a Byzantine Empire, Byzantine Christianity, Christian monk and the author of an influential series of theological writings on sixth-century Christology, Christological controversies. Though the details of his li ...

; and Maximus the Confessor

Maximus the Confessor ( el, Μάξιμος ὁ Ὁμολογητής), also spelt Maximos, otherwise known as Maximus the Theologian and Maximus of Constantinople ( – 13 August 662), was a Christian monk, theologian, and scholar.

In his earl ...

. In the West the leaders were: Cyprian, Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

, Fulgentius of Ruspe

Fabius Claudius Gordianus Fulgentius, also known as Fulgentius of Ruspe (462 or 467 – 1 January 527 or 533) was North African Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Ruspe, in modern-day Tunisia, during the 5th and 6th century. He has been ca ...

, Pope Leo I

Pope Leo I ( 400 – 10 November 461), also known as Leo the Great, was bishop of Rome from 29 September 440 until his death. Pope Benedict XVI said that Leo's papacy "was undoubtedly one of the most important in the Church's history."

Leo was ...

and Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

. As the contest with Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius ( – AD), an ascetic and philosopher from t ...

and Semi-pelagianism

Semi-Pelagianism (or Semipelagianism) is a Christian theological and soteriological school of thought on salvation. Semipelagian thought stands in contrast to the earlier Pelagian teaching about salvation, Pelagianism (in which people are born unt ...

clarified the dogmas of grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninco ...

and liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

, providence

Providence often refers to:

* Providentia, the divine personification of foresight in ancient Roman religion

* Divine providence, divinely ordained events and outcomes in Christianity

* Providence, Rhode Island, the capital of Rhode Island in the ...

and predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

, original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

and the condition of our first parents in Paradise, so also the contests with the Donatists brought codification to the doctrine of the sacraments (baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

), the hierarchical constitution of the Church her ''magisterium

The magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church is the church's authority or office to give authentic interpretation of the Word of God, "whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition." According to the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Chur ...

'' or teaching authority, and her infallibility

Infallibility refers to an inability to be wrong. It can be applied within a specific domain, or it can be used as a more general adjective. The term has significance in both epistemology and theology, and its meaning and significance in both fi ...

. A culminating contest was decided by the Second Council of Nicæa

The Second Council of Nicaea is recognized as the last of the first seven ecumenical councils by the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church. In addition, it is also recognized as such by the Old Catholics, the Anglican Communion, and ...

(787).[

These developments left the dogmatic teachings of the Fathers as a collection of monographs rather than a systematic exposition. Irenæus shows attempts at synthesis; the trilogy of ]Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and ...

(d. 217) marks an advance in the same direction. Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( grc-gre, Γρηγόριος Νύσσης; c. 335 – c. 395), was Bishop of Nyssa in Cappadocia from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 395. He is venerated as a saint in Catholici ...

(d. 394) then endeavoured in his "Large Catechetical Treatise" (''logos katechetikos ho megas'') to correlate in a broad synthetic view the fundamental dogmas of the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Sacraments. In the same manner, though somewhat fragmentarily, Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary of Poitiers ( la, Hilarius Pictaviensis; ) was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" () and the "Athanasius of the West". His name comes from the Latin word for happy or ...

(d. 366) developed in his work "De Trinitate" the principal truths of Christianity.[

The catechetical instructions of ]Cyril of Jerusalem

Cyril of Jerusalem ( el, Κύριλλος Α΄ Ἱεροσολύμων, ''Kýrillos A Ierosolýmon''; la, Cyrillus Hierosolymitanus; 313 386 AD) was a theologian of the early Church. About the end of 350 AD he succeeded Maximus as Bishop of ...

(d. 386) especially his five mystagogical treatises, on the Apostles' Creed

The Apostles' Creed (Latin: ''Symbolum Apostolorum'' or ''Symbolum Apostolicum''), sometimes titled the Apostolic Creed or the Symbol of the Apostles, is a Christian creed or "symbol of faith".

The creed most likely originated in 5th-century Ga ...

and the three sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

, and the Holy Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

, contain an almost complete dogmatic treatise. Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promo ...

(d. 397) in his chief works: "De fide", "De Spiritu S.", "De incarnatione", "De mysteriis", "De poenitentia", treated the main points of dogma in classic Latin, though without any attempt at a unifying synthesis. Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

(d. 430) wrote one or two works, as the "De fide et symbolo" and the "Enchiridium", which are compendia of dogmatic and moral theology, as well as his speculative work ''De Trinitate

''On the Trinity'' ( la, De Trinitate) is a Latin book written by Augustine of Hippo to discuss the Trinity in context of the logos. Although not as well known as some of his other works, some scholars have seen it as his masterpiece, of more do ...

''.[

In regard to the Trinity and Christology, ]Cyril of Alexandria

Cyril of Alexandria ( grc, Κύριλλος Ἀλεξανδρείας; cop, Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ Ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲗⲗⲟⲩ ⲁ̅ also ⲡⲓ̀ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲕⲓⲣⲓⲗⲗⲟⲥ; 376 – 444) was the Patriarch of Alexandria from 412 to 444 ...

(d. 444) was a model for later dogmatic theologians. Towards the end of the Patristic Age Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville ( la, Isidorus Hispalensis; c. 560 – 4 April 636) was a Spanish scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of ...

(d. 636) in the West and John Damascene (b. ab. 700) in the East paved the way for a systematic treatment of dogmatic theology. Following closely the teachings of Augustine and Gregory the Great, Isidore proposed to collect all the writings of the earlier Fathers and to hand them down as a precious inheritance to posterity. The results of this undertaking were the "Libri III sententiarum seu de summo bono". The work of John Damascene (d. after 754) not only gathered the teachings and views of the Greek Fathers, but reduced them to a systematic whole; he deserves to be called the first and the only scholastic among the Greeks. His main work, which is divided into three parts, is entitled: "Fons scientiæ" (''pege gnoseos''), because it was intended to be the source, not merely of theology, but of philosophy and Church history as well. Under his leadership, the communion of saints

The communion of saints (), when referred to persons, is the spiritual union of the members of the Christian Church, living and the dead, but excluding the damned. They are all part of a single " mystical body", with Christ as the head, in which ...

, the veneration of relics

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

and holy images were placed on a basis of orthodoxy. The only Greek prior to him who had produced a complete system of theology was Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite) was a Greek author, Christian theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century, who wrote a set of works known as the ''Corpus Areopagiticum'' or ...

, in the fifth century.[

]

Other notable theologians of the period

Middle Ages (800–1500)

Beginning of Scholasticism (800–1200)

The scope of the scholastic method is to analyze the content of dogma by means of dialectics.

The scope of the scholastic method is to analyze the content of dogma by means of dialectics.[ Scholasticism did not take its guidance from John Damascene or Pseudo-Dionysius, but from Augustine. Augustinian thought runs through the whole progress of Western Catholic philosophy and theology.][ The ]Venerable Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

(d. 735), is the link which joins the patristic with the medieval history of theology.[

Up to the time of ]Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury, OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also called ( it, Anselmo d'Aosta, link=no) after his birthplace and (french: Anselme du Bec, link=no) after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of th ...

, the theologians were more concerned with preserving than with developing the writings of the Fathers. The beginnings of Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

may be traced back to the days of Charlemagne (d. 814). Theology was cultivated nowhere with greater industry than in the cathedral and monastic schools, founded and fostered by Charlemagne. The earliest signs of a new approach appeared in the ninth century in the work of Paschasius Radbertus

Paschasius Radbertus (785–865) was a Carolingian theologian and the abbot of Corbie, a monastery in Picardy founded in 657 or 660 by the queen regent Bathilde with a founding community of monks from Luxeuil Abbey. His most well-known and influe ...

, and Rabanus Maurus

Rabanus Maurus Magnentius ( 780 – 4 February 856), also known as Hrabanus or Rhabanus, was a Frankish Benedictine monk, theologian, poet, encyclopedist and military writer who became archbishop of Mainz in East Francia. He was the author of the ...

. These speculations were carried to a greater depth by (Lanfranc

Lanfranc, OSB (1005 1010 – 24 May 1089) was a celebrated Italian jurist who renounced his career to become a Benedictine monk at Bec in Normandy. He served successively as prior of Bec Abbey and abbot of St Stephen in Normandy and then ...

, Hugh of Langres :''This article is not about Hugh-Rainard of Tonnerre, bishop of Langres from 1065 to 1084''

Hugh of Langres (died 1050) was bishop of Langres.

As a theologian, he wrote a work, ''De corpore et sanguine Christi'', against Berengar of Tours. He ha ...

, etc.).[

Anselm of Canterbury (d. 1109) was the first to bring a sharp logic to bear upon the principal dogmas of Christianity, and to draw up a plan for dogmatic theology. Taking the substance of his doctrine from Augustine, Anselm, as a philosopher, was not so much a disciple of ]Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

as of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, in whose dialogues he had been schooled.[

The great mystics, ]Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Bernardus Claraevallensis; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templars, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order through ...

, and Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; it, Bonaventura ; la, Bonaventura de Balneoregio; 1221 – 15 July 1274), born Giovanni di Fidanza, was an Italian Catholic Franciscan, bishop, cardinal, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister G ...

, were at the same time distinguished Scholastics.[ It is upon the doctrine of Anselm and Bernard that the Scholastics of succeeding generations took their stand, and it was their spirit which lived in the theological efforts of the University of Paris.][

The first attempts at a theological system may be seen in the so-called '']Books of Sentences

''The Four Books of Sentences'' (''Libri Quattuor Sententiarum'') is a book of theology written by Peter Lombard in the 12th century. It is a systematic compilation of theology, written around 1150; it derives its name from the '' sententiae'' ...

'', collections and interpretations of quotations from the Fathers, more especially of Augustine. One of the earliest of these books is the ''Summa sententiarum'', an anonymous compilation created at the School of Loan some time after 1125. Another is ''The Sacraments of the Christian Faith'' written by Hugh of St. Victor

Hugh of Saint Victor ( 1096 – 11 February 1141), was a Saxon canon regular and a leading theologian and writer on mystical theology.

Life

As with many medieval figures, little is known about Hugh's early life. He was probably born in the 1090s ...

around 1135. His works are characterized throughout by a close adherence to Augustine and may serve as guides for beginners in the theology of Augustine. Peter Lombard

Peter Lombard (also Peter the Lombard, Pierre Lombard or Petrus Lombardus; 1096, Novara – 21/22 July 1160, Paris), was a scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, and author of '' Four Books of Sentences'' which became the standard textbook of ...

, called the "Magister Sententiarum" (d. 1164), stands above them all. What Gratian

Gratian (; la, Gratianus; 18 April 359 – 25 August 383) was emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 367 to 383. The eldest son of Valentinian I, Gratian accompanied his father on several campaigns along the Rhine and Danube frontiers and wa ...

had done for canon law Lombard did for dogmatic and moral theology. He sifted and explained and paraphrased the patristic lore in his "Libri IV sententiarum", and the arrangement which he adopted was, in spite of the lacunæ, so excellent that up to the sixteenth century his work was the standard text-book of theology. The work of interpreting this text began in the thirteenth century, and there was no theologian of note in the Middle Ages who did not write a commentary on the ''Sentences

''The Four Books of Sentences'' (''Libri Quattuor Sententiarum'') is a book of theology written by Peter Lombard in the 12th century. It is a systematic compilation of theology, written around 1150; it derives its name from the '' sententiae'' ...

'' of Lombard. No other work exerted such a powerful influence on the development of scholastic theology.[

William of Auvergne (d. 1248), who died as ]bishop of Paris

The Archdiocese of Paris (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Parisiensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Paris'') is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. It is one of twenty-three archdioceses in France ...

, deserves special mention. Though preferring the free, unscholastic method of an earlier age, he yet shows himself at once an original philosopher and a profound theologian. Inasmuch as in his numerous monographs on the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Sacraments, etc., he took into account the anti-Christian attacks of the Arabic writers on Aristoteleanism, he is the connecting link between this age and the thirteenth century.[

]

=Other notable theologians of the period

=

Scholasticism at its zenith (1200–1300)

The most brilliant period of Scholasticism embraces about 100 years, and with it are connected the names of Alexander of Hales

Alexander of Hales (also Halensis, Alensis, Halesius, Alesius ; 21 August 1245), also called ''Doctor Irrefragibilis'' (by Pope Alexander IV in the ''Bull De Fontibus Paradisi'') and ''Theologorum Monarcha'', was a Franciscan friar, theologian a ...

, Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop. Later canonised as a Catholic saint, he was known during his life ...

, Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; it, Bonaventura ; la, Bonaventura de Balneoregio; 1221 – 15 July 1274), born Giovanni di Fidanza, was an Italian Catholic Franciscan, bishop, cardinal, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister G ...

, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, and Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

. This period of Scholasticism was marked by the appearance of the theological '' Summae'', as well as the mendicant orders. In the thirteenth century the champions of Scholasticism were to be found in the Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

and Dominicans, beside whom worked also the Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

, Carmelites

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Car ...

, and Servites

The Servite Order, officially known as the Order of Servants of Mary ( la, Ordo Servorum Beatae Mariae Virginis; abbreviation: OSM), is one of the five original Catholic mendicant orders. It includes several branches of friars (priests and brothe ...

.[

]Alexander of Hales

Alexander of Hales (also Halensis, Alensis, Halesius, Alesius ; 21 August 1245), also called ''Doctor Irrefragibilis'' (by Pope Alexander IV in the ''Bull De Fontibus Paradisi'') and ''Theologorum Monarcha'', was a Franciscan friar, theologian a ...

(d. about 1245) was a Franciscan, while Albert the Great (d. 1280) was a Dominican. The ''Summa theologiæ'' of Alexander of Hales is the largest and most comprehensive work of its kind, flavoured with Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at le ...

. Albert was an intellectual working not only in matters philosophical and theological but in the natural sciences as well. He made a first attempt to present the entire philosophy of Aristotle and to place it at the service of Catholic theology. The logic of Aristotle had been rendered into Latin by Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

and had been used in the schools since the end of the sixth century; but his physics and metaphysics were made known to Western Christendom only through the Arabic philosophers of the thirteenth century. His works were prohibited by the Synod of Paris, in 1210, and again by a Bull of Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

in 1231. Later Scholastics, led by Albert the Great, went over the faulty Latin translation once more, and reconstructed the doctrine of Aristotle and its principles.[

]Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; it, Bonaventura ; la, Bonaventura de Balneoregio; 1221 – 15 July 1274), born Giovanni di Fidanza, was an Italian Catholic Franciscan, bishop, cardinal, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister G ...

(d. 1274) and Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

(d. 1274), mark the highest development of Scholastic theology. St. Bonaventure follows Alexander of Hales, his fellow-religious and predecessor, but surpasses him in mysticism and clearness of diction. Unlike the other Scholastics of this period, he did not write a theological ''Summa'', but a '' Commentary on the Sentences'', as well as his ''Breviloquium'', a condensed ''Summa''. Alexander of Hales and Bonaventure represent the old Franciscan Schools, from which the later School of Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

essentially differed.[

]Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

holds the same rank among the theologians as does Augustine among the Fathers of the Church. He is distinguished by wealth of ideas, systematic exposition of them, and versatility. For dogmatic theology his most important work is the ''Summa theologica

The ''Summa Theologiae'' or ''Summa Theologica'' (), often referred to simply as the ''Summa'', is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholasticism, scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all ...

''.

Duns Scotus (1266—1308), by bold and virulent criticism of the Thomistic system, was to a great extent responsible for its decline. Scotus is the founder a new Scotistic School, in the speculative treatment of dogma. Later Franciscans, among them Costanzo de Sarnano

Costanzo de Sarnano, O.F.M. Conv. or Gasparo Torri (1531–1595) was a Roman Catholic cardinal.

Biography

On 12 Jul 1587, he was consecrated bishop by Girolamo Bernerio, Bishop of Ascoli Piceno, with Giovanni Battista Albani

Giovanni Battis ...

, set about minimizing or even reconciling the doctrinal differences of the two.[

]

=Other notable theologians of the period

=

Gradual decline of Scholasticism (1300–1500)

The following period showed both consolidation, and disruption: the Fraticelli, nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings t ...

, conflict between Church and State ( Philip the Fair, Louis of Bavaria, the Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon – at the time within the Kingdom of Burgundy-Arles, Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire; now part of France – rather than i ...

). The spread of Nominalism owed much to two pupils of Duns Scotus: the Frenchman Peter Aureolus (d. 1321) and the Englishman William Occam

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vil ...

(d. 1347).[

Nominalism had less effect on the Dominican theologians, who were as a rule loyal Thomists.

][ It was in the early part of the sixteenth century that commentaries on the "Summa Theologica" of Aquinas began to appear. The Franciscans partly favoured Nominalism, partly adhered to pure Scotism. The Augustinian ]James of Viterbo

James of Viterbo ( it, Giacomo da Viterbo; – ), born Giacomo Capocci (nicknamed ''Doctor speculativus''), was an Italian Roman Catholic Augustinian friar and Scholastic theologian, who later became Archbishop of Naples.

Life

James ...

(d. 1308) attached himself to Ægidius of Rome; Gregory of Rimini

Gregory of Rimini (c. 1300 – November 1358), also called Gregorius de Arimino or Ariminensis, was one of the great scholastic philosophers and theologians of the Middle Ages. He was the first scholastic writer to unite the Oxonian and Parisia ...

(d. 1359), championed an undisguised nominalism. Among the Carmelites, Gerard of Bologna

Gerard of Bologna (died 1317) was an Italian Carmelite theologian and scholastic philosopher.

A convinced Thomist, he took a doctorate in theology in 1295 at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

...

(d. 1317) was a staunch Thomist. Generally speaking, the later Carmelites were followers of Aquinas. The Order of the Carthusians

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has its ...

produced in the fifteenth century a prominent theologian in the person of Dionysius Ryckel (d. 1471), surnamed "the Carthusian", who set up his chair in Roermond

Roermond (; li, Remunj or ) is a city, municipality, and diocese in the Limburg province of the Netherlands. Roermond is a historically important town on the lower Roer on the east bank of the river Meuse. It received town rights in 1231. Roer ...

, (the Netherlands).[

Outside the religious orders were many other. The Englishman Thomas Bradwardine (d. 1340), was the foremost mathematician of his day and a celebrated scholastic philosopher and doctor of theology. He is often called Doctor Profundus. (The Carmelite ]Thomas Netter Thomas Netter (c. 1375 – 2 November 1430) was an English Scholastic theologian and controversialist. From his birthplace he is commonly called Thomas of Walden, or Thomas Waldensis.

Life

Born at Saffron Walden, Essex, as a young adult he ent ...

(d. 1430), surnamed Waldensis, was an English Scholastic theologian and controversialist. Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 11 August 1464), also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus (), was a German Catholic cardinal, philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician, and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Renai ...

(d. 1404) was an early proponent of Renaissance humanism, and inaugurated a new and speculative system in dogmatic theology. A thorough treatise on the Church was written by John Torquemada (d. 1468), and a similar work by St. John Capistran (d. 1456). Alphonsus Tostatus (d. 1454) interspersed his Biblical commentaries on the Scriptures with dogmatic treatises. His work "Quinque paradoxa" is a treatise on Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

and Mariology

Mariology is the theological study of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Mariology seeks to relate doctrine or dogma about Mary to other doctrines of the faith, such as those concerning Jesus and notions about redemption, intercession and grace. Chri ...

.[

]

=Other notable theologians of the period

=

Modern era (1500–1900)

The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

brought about a more accurate definition of important Catholic articles of faith. From the period of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

the revival of classical studies gave new vigour to exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (logic), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern usage, ...

and patrology

Patristics or patrology is the study of the early Christian writers who are designated Church Fathers. The names derive from the combined forms of Latin ''pater'' and Greek ''patḗr'' (father). The period is generally considered to run from ...

, while the Reformation stimulated the universities which had remained Catholic, especially in Spain (Salamanca, Alcalá, Coimbra) and in the Netherlands (Louvain), to intellectual research. The Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

of Paris regained its lost prestige only towards the end of the sixteenth century. Among the religious orders the newly founded Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

probably contributed most to the revival and growth of theology. Matthias Joseph Scheeben

Matthias Joseph Scheeben (Meckenheim, Rhine Province, 1 March 1835 – Cologne, 21 July 1888) was a German Catholic theological writer and mystic. "The generations that followed Scheeben regarded him as one of the greatest minds of modern Ca ...

distinguishes five phases in this period.[

]

First phase: to the Council of Trent (1500–1570)

The whole literature of this period bears an apologetical and controversial character and deals with those subjects which had been attacked most bitterly: the rule and sources of faith, the Church, grace, the sacraments, especially the holy Eucharist. Peter Canisius

Peter Canisius ( nl, Pieter Kanis; 8 May 1521 – 21 December 1597) was a Dutch Jesuit Catholic priest. He became known for his strong support for the Catholic faith during the Protestant Reformation in Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Swit ...

(d. 1597) gave to the Catholics not only his world-renowned catechism, but also a most valuable Mariology.[

In England ]John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic bishop, cardinal, and theologian. Fisher was also an academic and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He was canonized by Pope Pius XI.

Fisher was executed by o ...

, Bishop of Rochester (d. 1535), and Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

(d. 1535) championed the cause of the Catholic faith. The Jesuit Nicholas Sanders

Nicholas Sanders (also spelled Sander; c. 1530 – 1581) was an English Catholic priest and polemicist.

Early life

Sanders was born at Sander Place near Charlwood, Surrey, one of twelve children of William Sanders, once sheriff of Surrey, who ...

wrote one of the best treatises on the Church. In Belgium the professors of the University of Louvain opened new paths for the study of theology, foremost among them were: Jodocus Ravesteyn (d. 1570), and John Hessels

Jan Hessels, Jean Leonardi Hasselius or Jean Hessels ( Hasselt, 1522 – 1566) was a Flemish theologian and controversialist at the University of Louvain. He was a defender of Baianism.

Life

Hessels was born at Mechlin in 1522, and obtained his ...

(d. 1566).[

In France Jacques Merlin, and ]Gilbert Génebrard Gilbert may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Gilbert (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Gilbert (surname), including a list of people

Places Australia

* Gilbert River (Queensland)

* Gilbert River (South ...

(d. 1597) rendered great services to dogmatic theology. Sylvester Prierias (d. 1523), Ambrose Catharinus

Lancelotto Politi ( religious name Ambrosius Catharinus, 1483–1553) was an Italian Dominican canon lawyer, theologian and bishop.

Historians and theologians generally have regarded Catharinus as a brilliant eccentric. He was frequently acc ...

(d; 1553), and Cardinal Seripandus are the boast of Italy. But, above all other countries, Spain is distinguished: Alphonsus of Castro (d. 1558), Michael de Medina

Miguel de Medina (born at Belalcázar, Spain, Belalcazar, Spain, 1489; died at Toledo, Spain, Toledo, May, 1578) was a Spanish Franciscan theologian.

Life

He entered the Franciscan order in the convent of S. Maria de Angelis at Hornachuelos, in ...

(d. 1578), Peter de Soto (d. 1563). Some of their works have remained classics, such as "De natura et gratia" (Venice 1547) of Dominic Soto; "De justificatione libri XV" (Venice, 1546) of Andrew Vega; "De locis theologicis" (Salamanca, 1563) of Melchior Cano

Melchor Cano (1509? – 30 September 1560) was a Spanish Scholastic theologian.

Clerical life

He was born in Tarancón, New Castile, and joined the Dominican Order in Salamanca, where by 1546 he had succeeded Francisco de Vitoria to the theo ...

.[

]

Other notable theologians of the period

Second phase: late Scholasticism at its height (1570–1660)

It was not until the seventeenth century, and then only for practical reasons, that moral theology was separated from the main body of Catholic dogma. The necessity of a further division of labour led to the independent development of other disciplines: apologetics, exegesis, church history. While apologetics uses historical and philosophical arguments, dogmatic theology makes use of Scripture and Tradition to prove the Divine character of the different dogmas.[

]Robert Bellarmine

Robert Bellarmine, SJ ( it, Roberto Francesco Romolo Bellarmino; 4 October 1542 – 17 September 1621) was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only 37. ...

(d. 1621), was a controversialist theologian who defended almost the whole of Catholic theology against the attacks of the Reformers. Jacques Davy Duperron

Jacques Davy Duperron (15 November 1556 – 6 December 1618) was a French politician and Roman Catholic cardinal.

Family and Education

Jacques Davy du Perron was born in Saint-Lô in Normandy, into the Davy family, of the Norman minor nobility ...

(d. 1618) of France wrote a treatise on the holy Eucharist. The pulpit orator Bossuet Bossuet is a French surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704), French bishop and theologian, uncle of Louis

* Louis Bossuet Louis Bossuet (22 February 1663 – 15 January 1742) was a French parle ...

(d. 1627) preached from the standpoint of history. The ''Præscriptiones Catholicae'' was a voluminous work of the Italian Gravina (7 vols., Naples, 1619–39). Adrian

Adrian is a form of the Latin language, Latin given name Adrianus (given name), Adrianus or Hadrianus (disambiguation), Hadrianus. Its ultimate origin is most likely via the former river Adria (river), Adria from the Venetic language, Venetic and ...

(d. 1669) and Peter de Walemburg (d. 1675), easily ranked among the best controversialists.[

The development of positive theology went hand in hand with the progress of research into the Patristic Era and into the history of dogma. These studies were especially cultivated in France and Belgium. A number of scholars, thoroughly versed in history, published in monographs the results of their investigations into the history of particular dogmas. Joannes Morinus (d. 1659) made the Sacrament of Penance the subject of special study; Hallier (d. 1659), the Sacrament of Holy orders, ]Jean Garnier

Jean Garnier (11 November 1612 – 26 November 1681) was a French Jesuit church historian, patristic scholar, and moral theologian.

Life

He was born at Paris, entered the Society of Jesus at the age of sixteen, and, after a distinguished course ...

(d. 1681), Pelagianism; Étienne Agard de Champs (d. 1701), Jansenism; Tricassinus (d. 1681), Augustine's doctrine on grace. The Jesuit Petavius (d. 1647) and the Oratorian Louis Thomassin

Louis Thomassin ( la, Ludovicus Thomassinus; 28 August 1619, Aix-en-Provence – 24 December 1695, Paris) was a French theologian and Oratorian.

Life

At the age of thirteen he entered the Oratory and for some years was professor of literature ...

(d. 1695), wrote "Dogmata theologica". They placed positive theology on a new basis without disregarding the speculative element.[

]

Neo-scholasticism

Religious orders fostered scholastic theology. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure were proclaimed Doctors of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribu ...

, respectively by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

and Pope Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V ( it, Sisto V; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order ...

.[

At the head of the Thomists was Domingo Bañez (d. 1604), who wrote a commentary on the theological ''Summa'' of Aquinas, which, combined with a similar work by ]Bartholomew Medina

Bartholomew (Aramaic: ; grc, Βαρθολομαῖος, translit=Bartholomaîos; la, Bartholomaeus; arm, Բարթողիմէոս; cop, ⲃⲁⲣⲑⲟⲗⲟⲙⲉⲟⲥ; he, בר-תולמי, translit=bar-Tôlmay; ar, بَرثُولَماو� ...

(d. 1581), forms a harmonious whole. The Carmelites of Salamanca produced the ''Cursus Salmanticensis'' (Salamanca, 1631–1712) in 15 folios, as commentary on the ''Summa''. At Louvain William Estius (d. 1613) wrote a Thomist commentary on the "Liber Sententiarum" of Peter the Lombard, while his colleague Francis Sylvius

Francis Sylvius (1581, in Braine-le-Comte, County of Hainaut, Hainault, now in Belgium – 22 February 1649, at Douai) was a County of Flanders, Flemish Roman Catholic theologian.

Life

After completing his course of humanities at Mons, he st ...

(d. 1649) explained the theological ''Summa'' of the master himself. In the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

Thomism was represented by Nicholas Ysambert (d. 1624). The University of Salzburg

The University of Salzburg (german: Universität Salzburg), also known as the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg (''Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg'', PLUS), is an Austrian public university

A public university or public college is a univ ...

also furnished the ''Theologia scholastica'' of Augustine Reding, who held the chair of theology in that university from 1645 to 1658.[

The Franciscans maintained doctrinal opposition to the Thomists, with steadily continued Scotist commentaries on Peter the Lombard. Scotistic manuals for use in schools were published about 1580 William Herincx. The ]Capuchins

Capuchin can refer to:

*Order of Friars Minor Capuchin

The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (; postnominal abbr. O.F.M. Cap.) is a religious order of Franciscan friars within the Catholic Church, one of Three " First Orders" that reformed from t ...

, on the other hand, adhered to Bonaventure, as, e.g., Gaudentius of Brescia

Saint Gaudentius ( it, San Gaudenzio di Brescia; died 410) was Bishop of Brescia from 387 until 410, and was a theologian and author of many letters and sermons. He was the successor of Saint Philastrius. Biography

Gaudentius had studied under P ...

, (d. 1672).[

]

Jesuit theologians

The Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

substantially adhered to the ''Summa'' of Thomas Aquinas, yet at the same time it made use of an eclectic freedom. Luis Molina (d. 1600) was the first Jesuit to write a commentary on the ''Summa'' of St. Thomas. Leading Jesuits were the Spaniards Francisco Suárez (d. 1617), and Gabriel Vasquez (d. 1604). Suárez was named "Doctor eximius" by Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758.Antipope ...

. Caspar Hurtado (d. 1646) wrote a commentary on Aquinas. A Theological manual was written by Sylvester Maurus (d. 1687). Francesco Sforza Pallavicino

Francesco Maria Sforza Pallavicino (or ''Pallavicini'') (28 November 1607, Rome – 4 June 1667, Rome), was an Italian cardinal, philosopher, theologian, literary theorist, and church historian.

A professor of philosophy and theology at the Rom ...

, (d. 1667), known as the historiographer of the Council of Trent, won repute as a dogmatic theologian by several of his writings.[

]

Other notable theologians of the period

Third phase: decline of Scholasticism (1660–1760)

Other counter-currents of thought set in: Cartesianism

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza. Descartes is of ...

in philosophy, Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarch's or the state's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope. Gallicanism is a rejection of ultramontanism; it has som ...

, and Jansenism

Jansenism was an early modern theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It was declared a heresy by t ...

. Bernard de Rubeis (d. 1775) produced a monograph on original sin. José Saenz d'Aguirre (d. 1699) wrote the three volume work "Theology of St. Anselm". Among the Franciscans Claudius Frassen (d. 1680) issued his elegant ''Scotus academicus''. Eusebius Amort

Eusebius Amort (November 15, 1692February 5, 1775) was a German Roman Catholic theology, theologian.

Life

Amort was born at Bibermuhle, near Tolz, in Upper Bavaria. He studied at Munich, and at an early age joined the Canons Regular at Polling A ...

(d. 1775), the foremost theologian in Germany, combined conservatism with due regard for modern demands.[

The "Theologia Wirceburgensis" was published in 1766–71 by the Jesuits of Würzburg. The new school of Augustinians based their theology on the system of Gregory of Rimini rather than on that of Ægidius of Rome. To this school belonged ]Henry Noris

Henry Noris (29 August 1631 – 23 February 1704), or Enrico Noris, was an Italian church historian, theologian and Cardinal.

Biography

Noris was born at Verona, and was baptized with the name Hieronymus (Girolamo). His ancestors were Irish. ...

(d. 1704). Its best work on dogmatic theology came from the pen of Giovanni Lorenzo Berti

Giovanni Lorenzo Berti (1696–1766), also known by his Latinized name Johannes Laurentius Berti, was an Italian Augustinian theologian. The General of the Order of Hermits of St. Augustine, Schiaffinati, instructed him to write a book, to be u ...

(d. 1766).[

The ]French Oratory

The Congregation of the Oratory of Jesus and Mary Immaculate (french: Société de l'Oratoire de Jésus et de Marie Immaculée, la, Congregatio Oratorii Iesu et Mariæ), best known as the French Oratory, is a society of apostolic life of Cathol ...

took up Jansenism, with Pasquier Quesnel

Pasquier Quesnel, CO (14 July 1634 – 2 December 1719) was a French Jansenist theologian.

Life

Quesnel was born in Paris, and, after graduating from the Sorbonne with distinction in 1653, he joined the French Oratory in 1657. There he soon ...

and Lebrun. The Sorbonne of Paris also adopted aspects of Jansenism and Gallicanism. Exceptions were Louis Abelly

Louis Abelly (1603–1691) was Vicar-General of Bayonne, a parish priest in Paris, and subsequently Bishop of Rodez in 1664.

Biography

In 1666 Abelly abdicated and attached himself to St. Vincent de Paul in the House of St. Lazare, Paris (Laza ...

(d. 1691) and Honoratus Tournély (d. 1729), whose "Prælectiones dogmaticæ" are numbered among the best theological text-books.[

Against Jansenism stood the Jesuits ]Dominic Viva

Domenico Viva (19 October 1648 – 5 July 1726) was an Italian Jesuit theologian.

Life

Viva was born at Lecce, and entered the Society of Jesus 12 May 1663. He taught the humanities and Greek, nine years' philosophy, eight years moral theolog ...

(d. 1726), and La Fontaine

Jean de La Fontaine (, , ; 8 July 162113 April 1695) was a French fabulist and one of the most widely read French poets of the 17th century. He is known above all for his '' Fables'', which provided a model for subsequent fabulists across Eu ...

(d. 1728). Gallicanism and Josephinism

Josephinism was the collective domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms ...

were also pressed by the Jesuit theologians, especially by Francesco Antonio Zaccaria

Francesco Antonio Zaccaria (March 27, 1714 - October 10, 1795) was an Italian theologian, historian, and prolific writer.

Biography

Francesco Antonio Zaccaria was born in Venice. His father, Tancredi, was a noted jurist. He joined the Austria ...

(d. 1795), Alfonso Muzzarelli (d. 1813), Bolgeni (d. 1811), Roncaglia, and others. The Jesuits were seconded by the Dominicans Giuseppe Agostino Orsi

Giuseppe Agostino Orsi (1692, Florence - 1761) was a cardinal, theologian, and ecclesiastical historian.

Biography

Born as Agostino Francesco Orsi at Florence on 9 May 1692, of the aristocratic Florentine family Orsi, he studied grammar and rheto ...

(d. 1761) and Thomas Maria Mamachi (d. 1792). Barnabite

, image = Barnabites.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = One version of the Barnabite logo. "P.A." refers to Paul the Apostle and the three hills symbolize the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

, a ...

Hyacinthe Sigismond Gerdil

Hyacinthe Sigismond Gerdil, CRSP (23 June 1718 – 12 August 1802) was an Italian theologian, bishop and cardinal, who was a significant figure in the response of the papacy to the assault on the Catholic Church by the upheavals caused by the ...

(d. 1802) was a significant figure in the response of the papacy to the upheavals caused by the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. Alphonsus Liguori

Alphonsus Liguori, CSsR (27 September 1696 – 1 August 1787), sometimes called Alphonsus Maria de Liguori or Saint Alphonsus Liguori, was an Italian Catholic bishop, spiritual writer, composer, musician, artist, poet, lawyer, scholastic philosop ...

(d. 1787) wrote popular works.

Other notable theologians of the period

Fourth phase: at a low ebb (1760–1840)

In France the influences of Jansenism and Gallicanism were still powerful; in the German Empire Josephinism

Josephinism was the collective domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms ...

and Febronianism

Febronianism was a powerful movement within the Roman Catholic Church in Germany, in the latter part of the 18th century, directed towards the nationalizing of Catholicism, the restriction of the power of the papacy in favor of that of the episcopa ...

spread. The suppression of the Society of Jesus

The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the Society of Jesus from most of the countries of Western Europe and their colonies beginning in 1759, and the abolishment of the order by the Holy See in 1773. The Jesuits were ...

by Pope Clement XIV

Pope Clement XIV ( la, Clemens XIV; it, Clemente XIV; 31 October 1705 – 22 September 1774), born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 May 1769 to his death in Sep ...

occurred in 1773. The period was dominated by the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, and German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

.

Marian Dobmayer

Marian Dobmayer (24 October 1753 at Schwandorf, Bavaria – 21 December 1805 at Amberg, Bavaria) was a German Benedictine theologian.

Life

He first entered the Society of Jesus, and after its suppression in 1773 joined the Benedictines in the mo ...

(d. 1805) wrote a standard manual. Benedict Stattler

Benedict Stattler (30 January 1728 – 21 August 1797) was a German Jesuit theologian, and an opponent of Immanuel Kant. He was a member of the German Catholic Enlightenment.

Life

Benedict Stattler was born at Kötzting, Bavaria. He was edu ...

(d. 1797) was a member of the German Catholic Enlightenment and wrote against Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

's '' Critique of Pure Reason'', as did Patrick Benedict Zimmer Patrick Benedict Zimmer (born at Abtsgmund, Württemberg, 22 February 1752; died at Stenheim near Dillingen, 16 October., 1820) was a Catholic philosopher and theologian.

Life

Zimmer studied the Humanities and philosophy at Ellwangen, theology a ...

(d. 1820).

Fifth phase: restoration of dogmatic theology (1840–1900)

Harold Acton

Sir Harold Mario Mitchell Acton (5 July 1904 – 27 February 1994) was a British writer, scholar, and aesthete who was a prominent member of the Bright Young Things. He wrote fiction, biography, history and autobiography. During his stay in Ch ...

remarked on the large number of histories of dogma published in Germany published in the years 1838 to 1841. Joseph Görres

Johann Joseph Görres, since 1839 von Görres (25 January 1776 – 29 January 1848), was a German writer, philosopher, theologian, historian and journalist.

Early life

Görres was born in Koblenz. His father was moderately well off, and sent hi ...

(d. 1848) and Ignaz von Döllinger

Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger (; 28 February 179914 January 1890), also Doellinger in English, was a German theologian, Catholic priest and church historian who rejected the dogma of papal infallibility. Among his writings which proved con ...

(d. 1890) intended that Catholic theology should influence the development of German states.

Johann Adam Möhler

Johann Adam Möhler (6 May 1796 – 12 April 1838) was a German Roman Catholic theologian.

He was born at Igersheim in the Bailiwick of Franconia of the Teutonic Order (from 1809 on part of Württemberg), and after studying philosophy and theolo ...

advanced patrology

Patristics or patrology is the study of the early Christian writers who are designated Church Fathers. The names derive from the combined forms of Latin ''pater'' and Greek ''patḗr'' (father). The period is generally considered to run from ...

and symbolism. Both positive and speculative theology received a new lease of life, the former through Heinrich Klee

Heinrich Klee (20 April 1800 in Münstermaifeld, Rhine province – 28 July 1840 in Munich) was a German theologian and Biblical exegete who argued against liberal and Rationalist currents in Catholic thought.

Biography

At the age of sevent ...

(d. 1840), the latter through Franz Anton Staudenmaier

Franz Anton Staudenmaier (11 September 1800 - 19 January 1856) was a Catholic theologian. He was a major figure in the Catholic theology of Germany in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Life

Born at Donzdorf, Württemberg, he was a pupil at ...

(d. 1856). At the same time men like Joseph Kleutgen

Joseph (or Josef) Wilhelm Karl Kleutgen (9 April 1811 – 13 January 1883) was a German Jesuit theologian and philosopher. He was a member of the Society of Jesus, and contributed significantly to the establishment of Neo-scholasticism. (d. 1883), Karl Werner (d. 1888), and Albert Stöckl (d. 1895) supported Scholasticism by thorough historical and systematic writings.[

In France and Belgium the dogmatic theology of ]Thomas-Marie-Joseph Gousset

Thomas-Marie-Joseph Gousset (born at Montigny-lès-Cherlieu, a village of Franche-Comté, in 1792; died at Reims in 1866) was a French cardinal and theologian.

The son of a vine-grower, he at first laboured in the fields, and did not begin h ...

(d. 1866) of Reims and the writings of Jean-Baptiste Malou

Joannes Baptista or Jean-Baptiste Malou (1809–1864) was a Belgian theologian who became bishop of Bruges.

Life

Malou was born in Ypres on 30 June 1809, the son of Senator Jean-Baptiste Malou and Marie-Thérèse Vanden Peereboom. His older broth ...

, Bishop of Bruges

The Diocese of Bruges (in Dutch Bisdom Brugge) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Belgium. It is a suffragan in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolis (religious jurisdiction), metropolitan Arch ...

(d. 1865) exerted great influence. In North America there were the works of Francis Kenrick

Francis Patrick Kenrick (December 3, 1796 or 1797 – July 8, 1863) was an Irish-born prelate of the Roman Catholic Church who served as the third Bishop of the Diocese of Philadelphia (1842–1851) and the sixth Archbishop of the Archdiocese o ...

(d. 1863); Cardinal Camillo Mazzella

Camillo Mazzella (10 February 1833 – 26 March 1900) was an Italian Jesuit theologian and cardinal.

Biography

Mazzella was born at Vitulano, near Benevento. He and his siblings were first tutored at home. Three of his brothers entered r ...

(d. 1900) wrote his dogmatic works while occupying the chair of theology at Woodstock College

Woodstock College was a Jesuit seminary that existed from 1869 to 1974. It was the oldest Jesuit seminary in the United States. The school was located in Woodstock, Maryland, west of Baltimore, from its establishment until 1969, when it moved to ...

, Maryland. In England Nicholas Wiseman

Nicholas Patrick Stephen Wiseman (3 August 1802 – 15 February 1865) was a Cardinal of the Catholic Church who became the first Archbishop of Westminster upon the re-establishment of the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850.

Born ...

(d. 1865), and Cardinal Manning (d. 1892) advanced Catholic theology.[

In Italy, ]Gaetano Sanseverino

Gaetano Sanseverino (7 August 1811 – 16 November 1865) was an Italian philosopher and theologian. He made a comparative study including the scholastics, particularly Thomas Aquinas, and of the connection between their doctrine and that of ...

(d. 1865), Matteo Liberatore

Matteo Liberatore (born at Salerno, Italy, 14 August 1810; died at Rome, 18 October 1892) was an Italian Jesuit philosopher, theologian, and writer. He helped popularize the Jesuit periodical '' Civiltà Cattolica'' in close collaboration with th ...

(d. 1892), and Salvator Tongiorgi Salvator Tongiorgi (25 December 1820 – 12 November 1865) was an Italian Jesuit philosopher and theologian.

Life

Born in Rome, Tongiorgi entered the Society of Jesus at the age of seventeen. After the usual noviceship, literary and philosophical ...

(d. 1865) worked to restore Scholastic philosophy, against tradition

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays or ...

alism and ontologism Ontologism is a philosophical system most associated with Nicholas Malebranche (1638–1715) which maintains that God and divine ideas are the first object of our intelligence and the intuition of God the first act of our intellectual knowledge.

...

, which had a numerous following among Catholic scholars in Italy, France, and Belgium. The pioneer work in positive theology fell to the Jesuit Giovanni Perrone Giovanni Perrone (11 March 1794 – 26 August 1876) was an Italian Jesuit and renowned theologian.

Life

Perrone was born in Chieri, Piedmont. After studying theology and obtaining a doctorate at Turin, he entered the Society of Jesus in Rome at age ...

(d. 1876) in Rome. Other theologians, as Carlo Passaglia

Carlo Passaglia (2 May 1812 – 12 March 1887) was an Italian Jesuit.

Life

He was born at Lucca.

Passaglia was soon destined for the priesthood, and was placed under the care of the Jesuits at the age of fifteen. He became successively doct ...

(d. 1887), Clement Schrader Clement Schrader (November 1820 at Itzum, in Hanover, Germany – 23 February 1875 at Poitiers, France) was a German Jesuit theologian.

Life

Schrader studied at the German College at Rome (1840–48) and entered the Society of Jesus on 17 Ma ...

(d. 1875), Cardinal Franzelin (d. 1886), Domenico Palmieri Domenico Palmieri (Piacenza, Italy, 4 July 1829 – Rome, 29 May 1909) was an Italian Jesuit scholastic theologian.

Life

He studied in his native city, where he was ordained priest in 1852. On 6 June 1852, he entered the Society of Jesus, wher ...

(d. 1909), and others, continued his work.[

Among the Dominicans was Cardinal Zigliara, an inspiring teacher and fertile author. Germany produced a number of prominent theologians, as ]Johannes von Kuhn

Johannes Evangelist von Kuhn (19 February 1806 – 8 May 1887) was a German Catholic theologian. With Franz Anton Staudenmaier he occupied the foremost rank among the speculative dogmatists of the Catholic school at the University of Tübingen.

...

(d. 1887), Anton Berlage

Anton Berlage (born 21 December 1805, Münster, Westphalia, now North Rhine-Westphalia - 6 December 1881, Münster) was a German Catholic dogmatic theologian.

Life

He studied philosophy and theology in the same city, after completing his course a ...

(d. 1881), Franz Xaver Dieringer

Franz Xaver Dieringer was a Catholic theologian (22 August 1811, at Rangendingen (Hohenzollern-Hechingen) – 8 September 1876, at Veringendorf (today a district of Veringenstadt)). He was a professor of dogma and homiletics at the University of Bo ...

(d. 1876), Albert Knoll (d. 1863), Heinrich Joseph Dominicus Denzinger

Heinrich Joseph Dominicus Denzinger (10 October 1819 – 19 June 1883) was a leading German Catholic theologian and author of the '' Enchiridion Symbolorum et Definitionum'' (Handbook of Creeds and Definitions) commonly referred to simply as " ...

(d. 1883), Constantine von Schäzler

Constantine von Schäzler (b. at Ratisbon, 7 May 1827; d. at Interlaken, 9 September 1880) was a German Jesuit theologian.

Life

By birth and training a Protestant, he was a pupil at the Protestant gymnasium St. Anna of Ratisbon; took the philosoph ...

(d. 1880), Bernard Jungmann

Bernard Jungmann was a German Catholic dogmatic theologian and ecclesiastical historian.

Biography

He was born at Münster in Westphalia on 1 March 1833; died at Leuven (Louvain), 12 January 1895. He belonged to an intensely Catholic family of ...

(d. 1895), and others. Germany's leading orthodox theologian at this time was Joseph Scheeben (d. 1888).

First Vatican Council

The First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

was held (1870) and sought a middle ground between the competing approaches of traditionalism and rational liberalism. The Council issued the dogmatic constitution ''Dei Filius

''Dei Filius'' is the incipit of the dogmatic constitution of the First Vatican Council on the Catholic faith, which was adopted unanimously, and issued by Pope Pius IX on 24 April 1870.

The constitution set forth the teaching of "the holy Catho ...

'', which stated in part that there is no real discrepancy between faith and reason, since the same God who reveals mysteries and infuses faith has bestowed the light of reason on the human mind; and that any apparent contradiction is mainly due, either to the dogmas of faith not having been understood and interpreted fully, or unproven scientific or critical theory assumed to be certain.

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

in his Encyclical '' Æterni Patris'' (1879) restored the study of the Scholastics, especially of St. Thomas, in all higher Catholic schools, a measure which was again emphasized by Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of C ...

.

Ludwig Ott

Ludwig Ott (24 October 1906 in Neumarkt-St. Helena – 25 October 1985 in Eichstätt) was a Roman Catholic theologian and medievalist from Bavaria, Germany.

After training at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, Ott was ordained a ...

's 1952 ''Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma'' is considered a standard reference work on dogmatics. An updated and revised edition was issued by Baronius Press

Baronius Press is a traditional Catholic book publisher. It was founded in London, in 2002 by former St Austin Press editor Ashley Paver and other young Catholics who had previously worked in publishing and printing. The press takes its name from ...

in 2018.

Development of Dogma

Around 434, Vincent of Lérins

Vincent of Lérins ( la, Vincentius; died ) was a Gallic monk and author of early Christian writings. One example was the ''Commonitorium'', c.434, which offers guidance in the orthodox teaching of Christianity. Suspected of semipelagianism, ...

wrote ''Commonitorium

The ' or ''Commonitory'' is a 5th-century Christian treatise written after the council of Ephesus under the pseudonym "" and attributed to Vincent of Lérins. Has good notes. It is known for Vincent's famous maxim: "Moreover, in the Catholic Churc ...

'', in which he recognized that doctrine can develop over time. New doctrines could not be declared, but older ones better understood. In John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

's 1845 "Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine", Newman listed seven criteria which "...can be applied in proper proportions to that further interpretation of dogmas aimed at giving them contemporary relevance." After its publication, Newman developed a lengthy correspondence with Giovanni Perrone Giovanni Perrone (11 March 1794 – 26 August 1876) was an Italian Jesuit and renowned theologian.

Life