History Of Aspirin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aspirin (

Ancient medical uses for willow were more varied. The Roman author

Ancient medical uses for willow were more varied. The Roman author

The first evidence that salicylates might have medical uses came in 1876, when the Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan experimented with salicin as a treatment for acute rheumatism, with considerable success, as he reported in

The first evidence that salicylates might have medical uses came in 1876, when the Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan experimented with salicin as a treatment for acute rheumatism, with considerable success, as he reported in

The name Aspirin was derived from the name of the chemical ASA—''Acetylspirsäure'' in German. ''Spirsäure'' (salicylic acid) was named for the meadowsweet plant, ''Spirea ulmaria'', from which it could be derived. ''Aspirin'' took a- for the acetylation, -spir- from Spirsäure, and added -in as a typical drug name ending to make it easy to say. In the final round of naming proposals that circulated through Bayer, it came down to ''Aspirin'' and ''Euspirin''; ''Aspirin'', they feared, might remind customers of aspiration, but Arthur Eichengrün argued that ''Eu''- (meaning "good") was inappropriate because it usually indicated an improvement over an earlier version of a similar drug. Since the substance itself was already known, Bayer intended to use the new name to establish their drug as something new; in January 1899 they settled on ''Aspirin''.

The name Aspirin was derived from the name of the chemical ASA—''Acetylspirsäure'' in German. ''Spirsäure'' (salicylic acid) was named for the meadowsweet plant, ''Spirea ulmaria'', from which it could be derived. ''Aspirin'' took a- for the acetylation, -spir- from Spirsäure, and added -in as a typical drug name ending to make it easy to say. In the final round of naming proposals that circulated through Bayer, it came down to ''Aspirin'' and ''Euspirin''; ''Aspirin'', they feared, might remind customers of aspiration, but Arthur Eichengrün argued that ''Eu''- (meaning "good") was inappropriate because it usually indicated an improvement over an earlier version of a similar drug. Since the substance itself was already known, Bayer intended to use the new name to establish their drug as something new; in January 1899 they settled on ''Aspirin''.

To secure phenol for aspirin production, and at the same time indirectly aid the German war effort, German agents in the United States orchestrated what became known as the Great Phenol Plot. By 1915, the price of phenol rose to the point that Bayer's aspirin plant was forced to drastically cut production. This was especially problematic because Bayer was instituting a new branding strategy in preparation of the expiry of the aspirin patent in the United States.

To secure phenol for aspirin production, and at the same time indirectly aid the German war effort, German agents in the United States orchestrated what became known as the Great Phenol Plot. By 1915, the price of phenol rose to the point that Bayer's aspirin plant was forced to drastically cut production. This was especially problematic because Bayer was instituting a new branding strategy in preparation of the expiry of the aspirin patent in the United States.

With the coming of the deadly

With the coming of the deadly  The U.S. ASA patent expired in 1917, but Sterling owned the ''aspirin'' trademark, which was the only commonly used term for the drug. In 1920,

The U.S. ASA patent expired in 1917, but Sterling owned the ''aspirin'' trademark, which was the only commonly used term for the drug. In 1920,

Between World War I and

Between World War I and

"Widespread aspirin use despite few benefits, high risks."

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. ScienceDaily, 22 July 2019.

– Bayer-funded website with historical content

{{Webarchive, url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081014081124/http://www.bayeraspirin.com/pain/asp_history.htm , date=14 October 2008 – Bayer timeline of aspirin history

– Multimedia presentation on the history of Bayer Aspirin

The Recent History of Platelets in Thrombosis and other Disorders

– transcript of a "witness seminar" with historians and key figures in the development of aspirin therapy for thrombosis *

acetylsalicylic acid

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat ...

) is a novel organic compound that does not occur in nature, and was first successfully synthesised in 1899. In 1897, scientists at the drug and dye firm Bayer began investigating acetylated organic compounds as possible new medicines, following the success of acetanilide

Acetanilide is an odourless solid chemical of leaf or flake-like appearance. It is also known as ''N''-phenylacetamide, acetanil, or acetanilid, and was formerly known by the trade name Antifebrin.

Preparation and properties

Acetanilide can be ...

ten years earlier. By 1899, Bayer created acetylsalicylic acid and named the drug 'Aspirin', going on to sell it around the world. The word ''Aspirin'' was Bayer's brand name, rather than the generic name of the drug; however, Bayer's rights to the trademark were lost or sold in many countries. Aspirin's popularity grew over the first half of the twentieth century, leading to fierce competition with the proliferation of aspirin brands and products.

Aspirin's popularity declined after the development of acetaminophen/paracetamol in 1956 and ibuprofen in 1962. In the 1960s and 1970s, John Vane

Sir John Robert Vane (29 March 1927 – 19 November 2004) was a British pharmacologist who was instrumental in the understanding of how aspirin produces pain-relief and anti-inflammatory effects and his work led to new treatments for heart and ...

and others discovered the basic mechanism of aspirin's effects, while clinical trials and other studies from the 1960s to the 1980s established aspirin's efficacy as an anti-clotting agent that reduces the risk of clotting diseases. Aspirin sales revived considerably in the last decades of the twentieth century, and remain strong in the twenty-first with widespread use as a preventive treatment for heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

s and strokes.

History of willow in medicine

Numerous authors have claimed thatwillow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist so ...

was used by the ancients as a painkiller, but there is no evidence that this is true. All such accounts date from ''after'' the discovery of aspirin, and are possibly based on a misunderstanding of the chemistry. Bartram's 1998 Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine is perhaps typical when it states, 'in 1838 chemists identified salicylic acid in the bark of White Willow. After many years, it was synthesised as acetylsalicylic acid, now known as aspirin.' It goes on to claim that willow extract has the same medical properties as aspirin, which is incorrect.

Ancient medical uses for willow were more varied. The Roman author

Ancient medical uses for willow were more varied. The Roman author Aulus Cornelius Celsus

Aulus Cornelius Celsus ( 25 BC 50 AD) was a Roman encyclopaedist, known for his extant medical work, ''De Medicina'', which is believed to be the only surviving section of a much larger encyclopedia. The ''De Medicina'' is a primary source on ...

recommended using the leaves, pounded and boiled in vinegar, as treatment for uterine prolapse

Uterine prolapse is when the uterus descends towards or through the opening of the vagina. Symptoms may include vaginal fullness, pain with sex, trouble urinating, urinary incontinence, and constipation. Often it gets worse over time. Low back ...

, but it is unclear what he considered the therapeutic action to be; it is unlikely to have been pain relief, as he recommended cauterization

Cauterization (or cauterisation, or cautery) is a medical practice or technique of burning a part of a body to remove or close off a part of it. It destroys some tissue in an attempt to mitigate bleeding and damage, remove an undesired growth, o ...

in the following paragraph (De Medicina, book VI, p. 287, chapter 18, section 10). Gerard quotes Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

, 'that he barkbeing burnt to ashes, and steeped in vinegar, takes away corns and other like risings in the feet and toes,' which is similar to modern uses of salicylic acid. Translations of Hippocrates make no mention of willow at all.

Nicholas Culpeper

Nicholas Culpeper (18 October 1616 – 10 January 1654) was an English botanist, herbalist, physician and astrologer.Patrick Curry: "Culpeper, Nicholas (1616–1654)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford, UK: OUP, 2004) His bo ...

, in The Complete Herbal, gave many uses for willow, including to staunch wounds, to 'stay the heat of lust' in man or woman, and to provoke urine ('if stopped') but, like Celsus, made no mention of any analgesic properties. He also used the burnt ashes of willow bark, mixed with vinegar, to 'take away warts, corns, and superfluous flesh.'

Although Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for turni ...

(1551) thought that fevers could be cured by 'cooling the air' with boughs and leaves of willow, the earliest known mention of willow bark extract for treating fever came in 1763, when a letter from English chaplain Edward Stone to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

described the dramatic power of powdered white willow

''Salix alba'', the white willow, is a species of willow native to Europe and western and central Asia.Meikle, R. D. (1984). ''Willows and Poplars of Great Britain and Ireland''. BSBI Handbook No. 4. .Rushforth, K. (1999). ''Trees of Britain an ...

bark to cure intermittent fevers, or 'ague'. Stone had 'accidentally' tasted the bark of a willow tree in 1758 and noticed an astringency reminiscent of Peruvian bark

Jesuit's bark, also known as cinchona bark, Peruvian bark or China bark, is a former remedy for malaria, as the bark contains quinine used to treat the disease. The bark of several species of the genus ''Cinchona'', family Rubiaceae indigenous t ...

, which he knew was used to treat malaria. Over the next five years he treated some 50 ague sufferers, with universal success, except in a few severe cases, where it merely reduced their symptoms. Stone's remedy was trialled by a few pharmacists, but was never widely adopted. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Confederate forces experimented with willow as a cure for malaria, without success.

Synthesis of acetylsalicylic acid

In the 19th century, as the young discipline oforganic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, ...

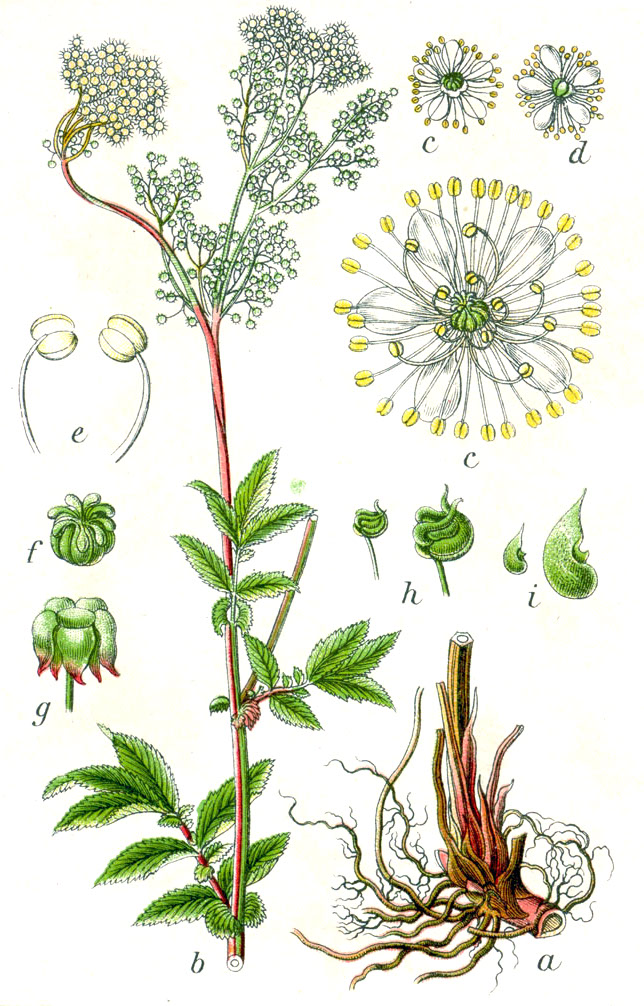

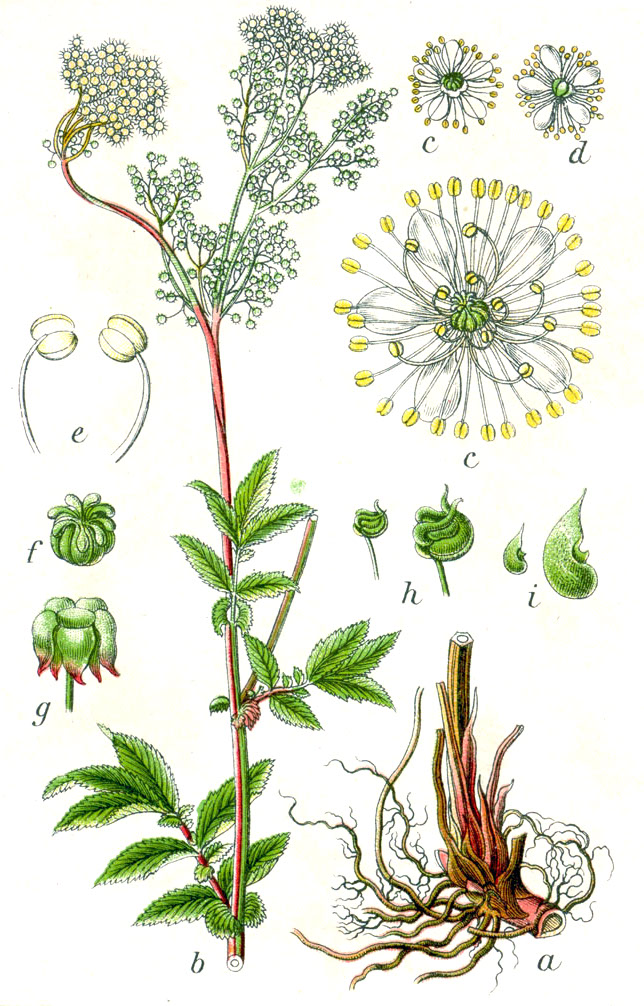

began to grow in Europe, scientists attempted to isolate and purify alkaloids and other novel organic chemicals. After unsuccessful attempts by Italian chemists Brugnatelli and Fontana in 1826, Johann Buchner obtained relatively pure salicin crystals from willow bark in 1828; the following year, Pierre-Joseph Leroux developed another procedure for extracting modest yields of salicin. In 1834, Swiss pharmacist Johann Pagenstecher extracted a substance from meadowsweet which, he suggested, might reveal an "excellent therapeutic aspect", although he was uninterested in increasing the number of chemicals available to pharmaceutical science. By 1838, Italian chemist Raffaele Piria found a method of obtaining a more potent acid form of willow extract, which he named salicylic acid. The German chemist who had been working to identify the ''Spiraea'' extract, Karl Jacob Löwig, soon realized that it was in fact the same salicylic acid that Piria had found.

The first evidence that salicylates might have medical uses came in 1876, when the Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan experimented with salicin as a treatment for acute rheumatism, with considerable success, as he reported in

The first evidence that salicylates might have medical uses came in 1876, when the Scottish physician Thomas MacLagan experimented with salicin as a treatment for acute rheumatism, with considerable success, as he reported in The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles, ...

. Meanwhile, German scientists tried salicylic acid in the form of sodium salicylate with less success and more severe side effects. The treatment of rheumatic fever with salicin gradually gained some acceptance in medical circles.

By the 1880s, the German chemical industry, jump-started by the lucrative development of dyes from coal tar

Coal tar is a thick dark liquid which is a by-product of the production of coke and coal gas from coal. It is a type of creosote. It has both medical and industrial uses. Medicinally it is a topical medication applied to skin to treat psorias ...

, was branching out to investigate the potential of new tar-derived medicines. The turning point was the advent of Kalle & Company's Antifebrine, the branded version of acetanilide

Acetanilide is an odourless solid chemical of leaf or flake-like appearance. It is also known as ''N''-phenylacetamide, acetanil, or acetanilid, and was formerly known by the trade name Antifebrin.

Preparation and properties

Acetanilide can be ...

—the fever-reducing properties of which were discovered by accident in 1886. Antifebrine's success inspired Carl Duisberg

Friedrich Carl Duisberg (29 September 1861 – 19 March 1935) was a German chemist and industrialist.

Life

Duisberg was born in Barmen, Germany. From 1879 to 1882, he studied at the Georg August University of Göttingen and Friedrich Schiller Un ...

, the head of research at the small dye firm Friedrich Bayer & Company, to start a systematic search for other useful drugs by acetylation of various alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

s and aromatic compound

Aromatic compounds, also known as "mono- and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons", are organic compounds containing one or more aromatic rings. The parent member of aromatic compounds is benzene. The word "aromatic" originates from the past grouping ...

s. Bayer chemists soon developed Phenacetin, followed by the sedatives Sulfonal and Trional

Trional (Methylsulfonal) is a sedative-hypnotic and anesthetic drug with GABAergic actions. It has similar effects to sulfonal, except it is faster acting.

History

Trional was prepared and introduced by Eugen Baumann and Alfred Kast in 1888. ...

.

Upon taking control of Bayer's overall management in 1890, Duisberg began to expand the company's drug research program. He created a pharmaceutical group for creating new drugs, headed by former university chemist Arthur Eichengrün

Arthur Eichengrün (13 August 1867 – 23 December 1949) was a German Jewish chemist, materials scientist, and inventor. He is known for developing the highly successful anti-gonorrhea drug Protargol, the standard treatment for 50 years until th ...

, and a pharmacology group for testing the drugs, headed by Heinrich Dreser (beginning in 1897, after periods under Wilhelm Siebel and Hermann Hildebrandt). In 1894, the young chemist Felix Hoffmann joined the pharmaceutical group. Dreser, Eichengrün and Hoffmann would be the key figures in the development of acetylsalicylic acid as the drug Aspirin (though their respective roles have been the subject of some contention).

In 1897, Hoffmann used salicylic acid refluxed with acetic anhydride to synthesise acetylsalicylic acid. Eichengrün sent the ASA to Dreser's pharmacology group for testing, and the initial results were very positive. The next step would normally have been clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, diet ...

s, but Dreser opposed further investigation of ASA because of salicylic acid's reputation for weakening the heart—possibly a side effect of the high doses often used to treat rheumatism. Dreser's group was soon busy testing Felix Hoffmann's next chemical success: diacetylmorphine

Heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine and diamorphine among other names, is a potent opioid mainly used as a recreational drug for its euphoric effects. Medical grade diamorphine is used as a pure hydrochloride salt. Various white and brow ...

(which the Bayer team soon branded as ''heroin'' because of the heroic feeling it gave them). Eichengrün, frustrated by Dreser's rejection of ASA, went directly to Bayer's Berlin representative Felix Goldmann to arrange low-profile trials with doctors. Though the results of those trials were also very positive, with no reports of the typical salicylic acid complications, Dreser still demurred. However, Carl Duisberg intervened and scheduled full testing. Soon, Dreser admitted ASA's potential and Bayer decided to proceed with production. Dreser wrote a report of the findings to publicize the new drug; in it, he omitted any mention of Hoffmann or Eichengrün. He would also be the only one of the three to receive royalties for the drug (for testing it), since it was ineligible for any patent the chemists might have taken out for creating it. For many years, however, he attributed Aspirin's discovery solely to Hoffmann.

The controversy over who was primarily responsible for aspirin's development spread through much of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. As of 2016 Bayer still described Hoffman as having "discovered a pain-relieving, fever-lowering and anti-inflammatory substance." Historians and others have also challenged Bayer's early accounts of Bayer's synthesis, in which Hoffmann was primarily responsible for the Bayer breakthrough. In 1949, shortly before his death, Eichengrün wrote an article, "Fifty Years of Aspirin", claiming that he had not told Hoffmann the purpose of his research, meaning that Hoffmann merely carried out Eichengrün's research plan, and that the drug would never have gone to the market without his direction. This claim was later supported by research conducted by historian Walter Sneader. Axel Helmstaedter, General Secretary of the International Society for the History of Pharmacy, subsequently questioned the novelty of Sneader's research, noting that several earlier articles discussed the Hoffmann–Eichengrün controversy in detail. Bayer countered Sneader in a press release stating that according to the records, Hoffmann and Eichengrün held equal positions, and Eichengrün was not Hoffmann's supervisor. Hoffmann was named on the US Patent as the inventor, which Sneader did not mention. Eichengrün, who left Bayer in 1908, had multiple opportunities to claim the priority and had never before 1949 done it; he neither claimed nor received any percentage of the profit from aspirin sales.

Naming the drug

The name Aspirin was derived from the name of the chemical ASA—''Acetylspirsäure'' in German. ''Spirsäure'' (salicylic acid) was named for the meadowsweet plant, ''Spirea ulmaria'', from which it could be derived. ''Aspirin'' took a- for the acetylation, -spir- from Spirsäure, and added -in as a typical drug name ending to make it easy to say. In the final round of naming proposals that circulated through Bayer, it came down to ''Aspirin'' and ''Euspirin''; ''Aspirin'', they feared, might remind customers of aspiration, but Arthur Eichengrün argued that ''Eu''- (meaning "good") was inappropriate because it usually indicated an improvement over an earlier version of a similar drug. Since the substance itself was already known, Bayer intended to use the new name to establish their drug as something new; in January 1899 they settled on ''Aspirin''.

The name Aspirin was derived from the name of the chemical ASA—''Acetylspirsäure'' in German. ''Spirsäure'' (salicylic acid) was named for the meadowsweet plant, ''Spirea ulmaria'', from which it could be derived. ''Aspirin'' took a- for the acetylation, -spir- from Spirsäure, and added -in as a typical drug name ending to make it easy to say. In the final round of naming proposals that circulated through Bayer, it came down to ''Aspirin'' and ''Euspirin''; ''Aspirin'', they feared, might remind customers of aspiration, but Arthur Eichengrün argued that ''Eu''- (meaning "good") was inappropriate because it usually indicated an improvement over an earlier version of a similar drug. Since the substance itself was already known, Bayer intended to use the new name to establish their drug as something new; in January 1899 they settled on ''Aspirin''.

Rights and sale

Under Carl Duisberg's leadership, Bayer was firmly committed to the standards of ethical drugs, as opposed topatent medicine

A patent medicine, sometimes called a proprietary medicine, is an over-the-counter (nonprescription) medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name (and sometimes a patent) and claimed ...

s. ''Ethical drugs'' were drugs that could be obtained only through a pharmacist, usually with a doctor's prescription. Advertising drugs directly to consumers was considered unethical and strongly opposed by many medical organizations; that was the domain of patent medicines. Therefore, Bayer was limited to marketing Aspirin directly to doctors.

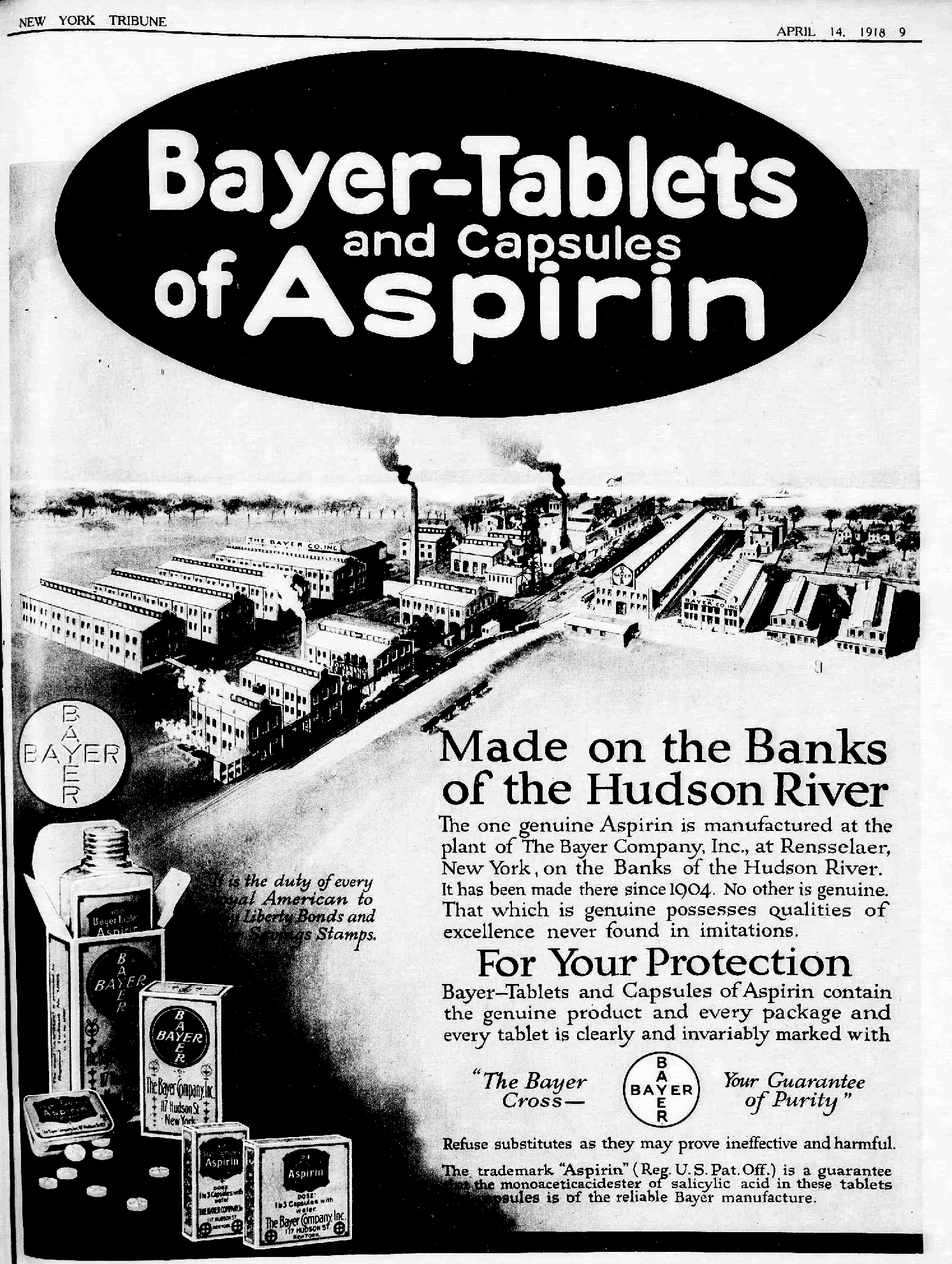

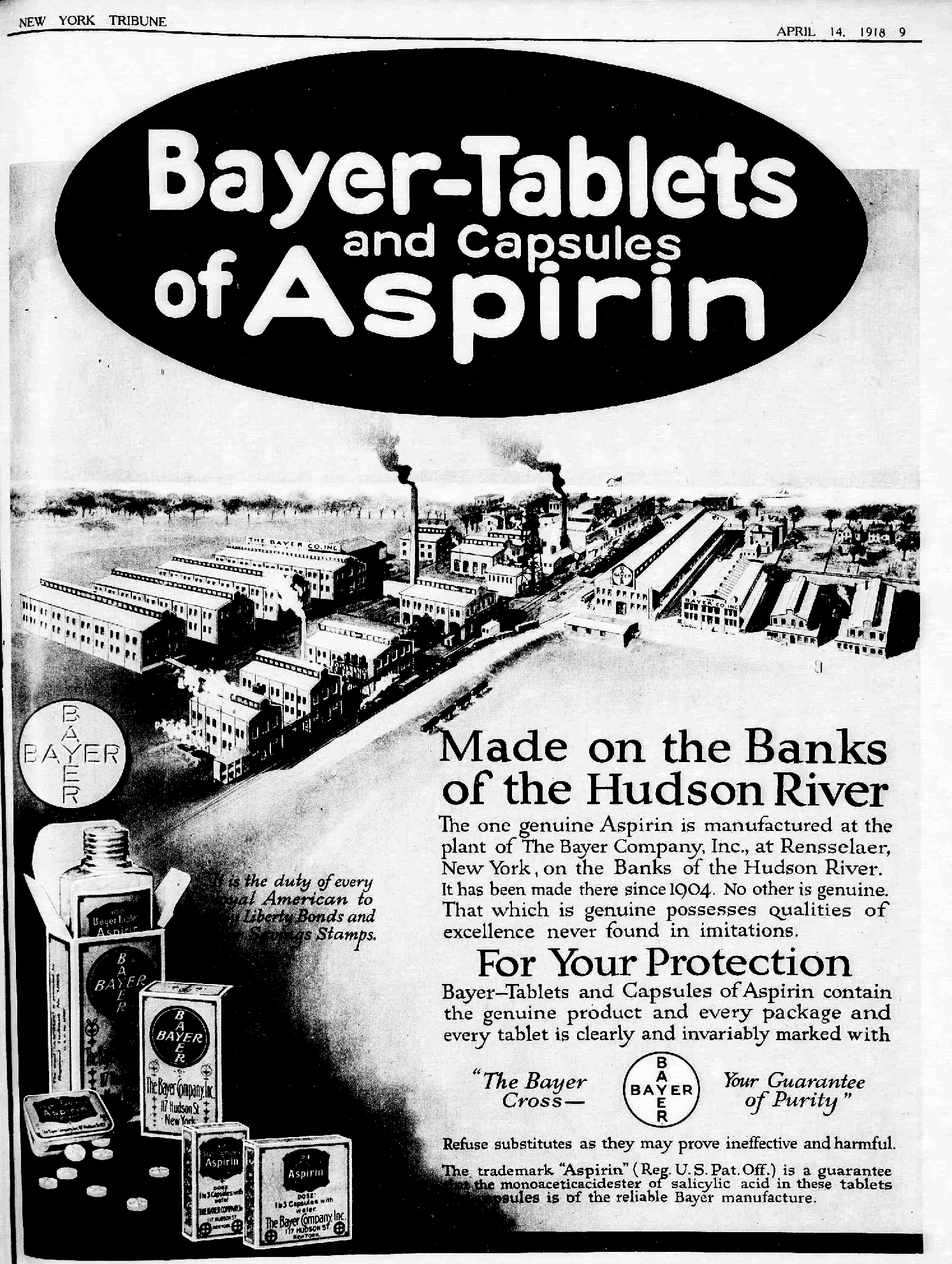

When production of Aspirin began in 1899, Bayer sent out small packets of the drug to doctors, pharmacists and hospitals, advising them of Aspirin's uses and encouraging them to publish about the drug's effects and effectiveness. As positive results came in and enthusiasm grew, Bayer sought to secure patent and trademark wherever possible. It was ineligible for patent in Germany (despite being accepted briefly before the decision was overturned), but Aspirin was patented in Britain (filed 22 December 1898) and the United States (US Patent 644,077 issued 27 February 1900). The British patent was overturned in 1905, the American patent was also besieged but was ultimately upheld.

Faced with growing legal and illegal competition for the globally marketed ASA, Bayer worked to cement the connection between Bayer and Aspirin. One strategy it developed was to switch from distributing Aspirin powder for pharmacists to press into pill form to distributing standardized tablets—complete with the distinctive ''Bayer cross'' logo. In 1903 the company set up an American subsidiary, with a converted factory in Rensselaer, New York, to produce Aspirin for the American market without paying import duties

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

. Bayer also sued the most egregious patent violators and smugglers. The company's attempts to hold onto its Aspirin sales incited criticism from muckraking journalists and the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's sta ...

, especially after the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws which was enacted by Congress in the 20th century and led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administratio ...

that prevented trademarked drugs from being listed in the United States Pharmacopeia

The ''United States Pharmacopeia'' (''USP'') is a pharmacopeia (compendium of drug information) for the United States published annually by the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (usually also called the USP), a nonprofit organization that ...

; Bayer listed ASA with an intentionally convoluted generic name (monoacetic acid ester of salicylic acid) to discourage doctors referring to anything but Aspirin.

World War I and Bayer

By the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914, Bayer was facing competition in all its major markets from local ASA producers as well as other German drug firms (particularly Heyden and Hoechst Hoechst, Hochst, or Höchst may refer to:

* Hoechst AG, a former German life-sciences company

* Hoechst stain, one of a family of fluorescent DNA-binding compounds

* Höchst (Frankfurt am Main), a city district of Frankfurt am Main, Germany

** Fra ...

). The British market was immediately closed to the German companies, but British manufacturing could not meet the demand—especially with phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it ...

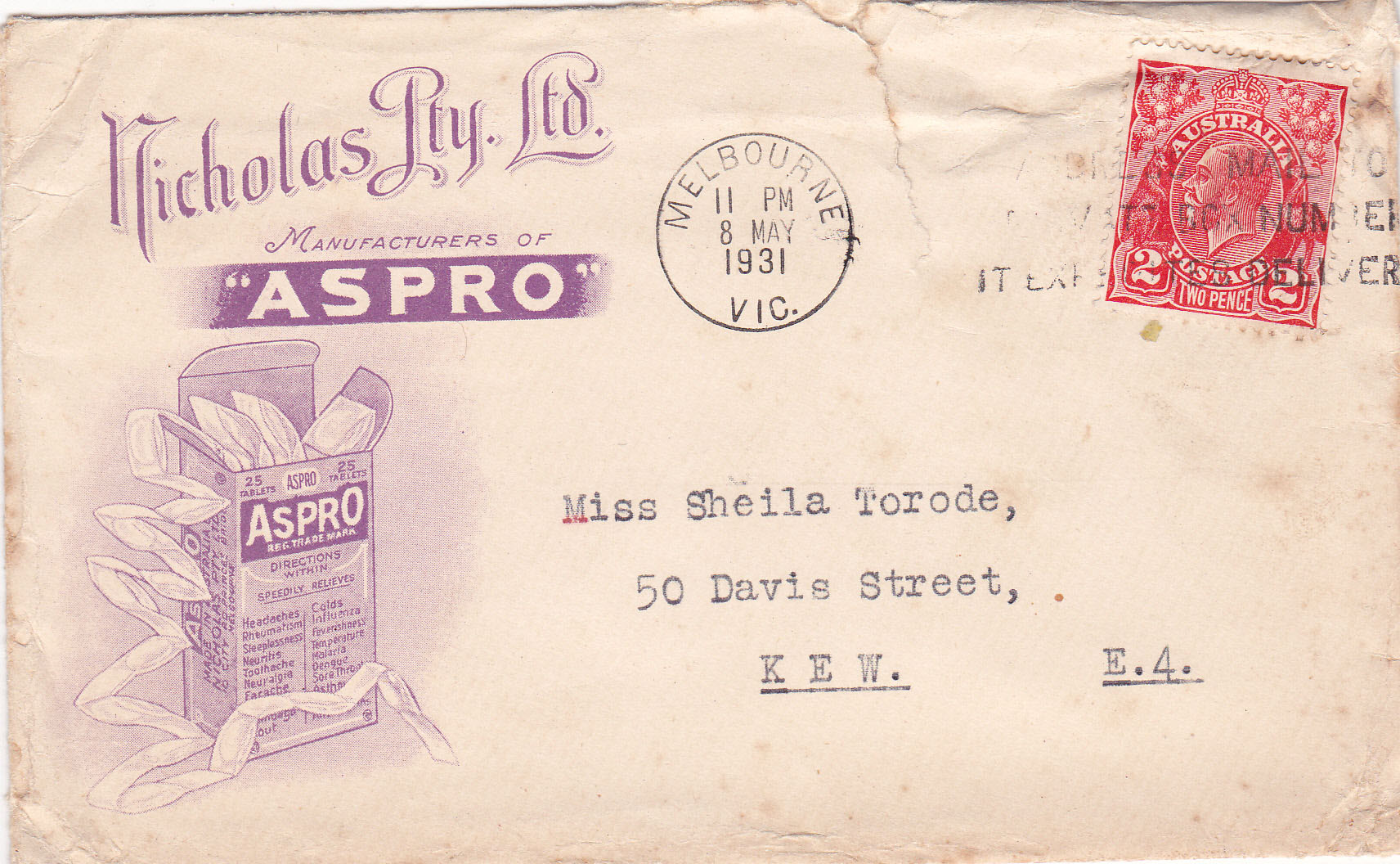

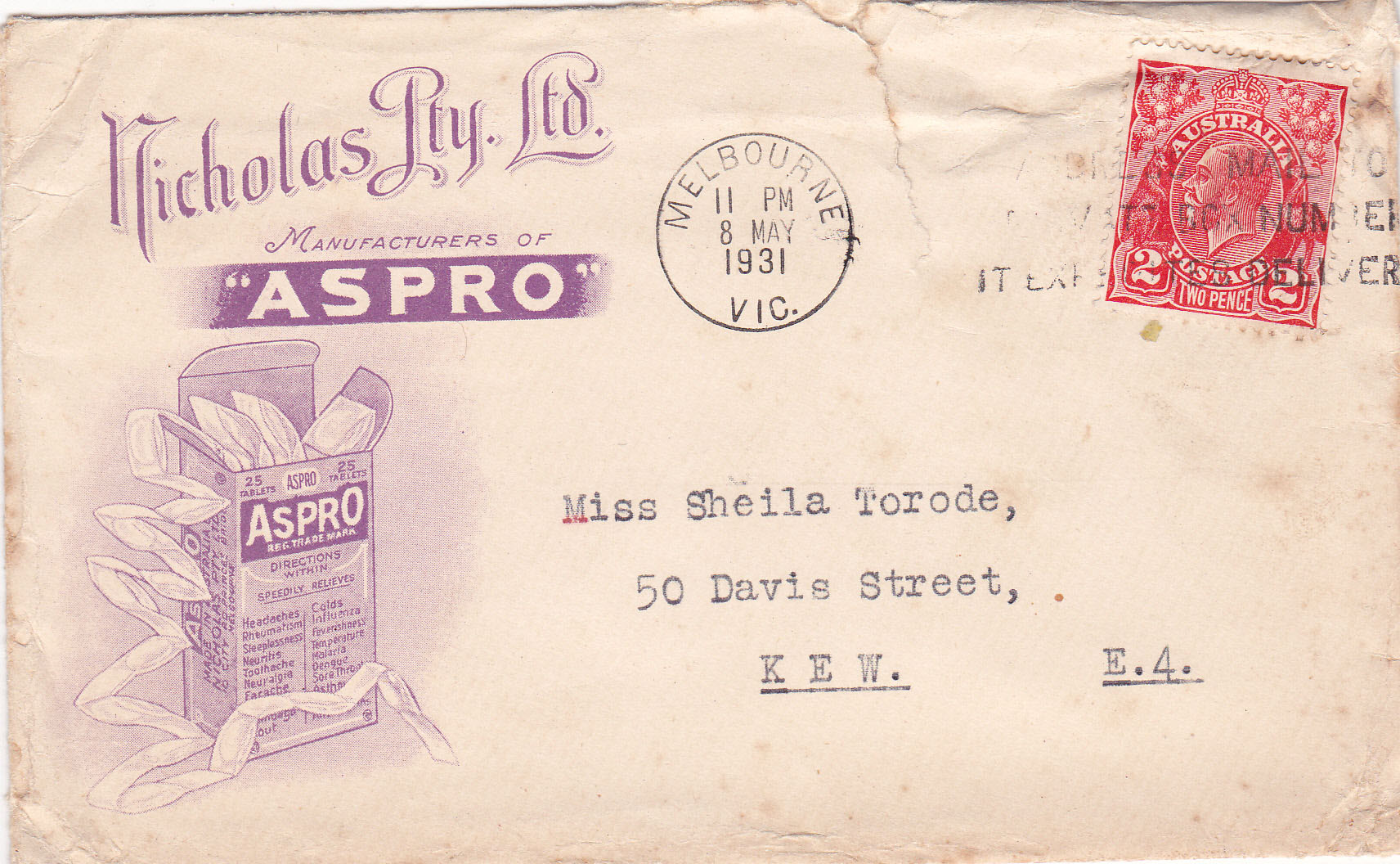

supplies, necessary for ASA synthesis, largely being used for explosives manufacture. On 5 February 1915, Bayer's UK trademarks were voided, so that any company could use the term ''aspirin''. The Australian market was taken over by ''Aspro'', after the makers of Nicholas-Aspirin lost a short-lived exclusive right

In Anglo-Saxon law, an exclusive right, or exclusivity, is a de facto, non-tangible prerogative existing in law (that is, the power or, in a wider sense, right) to perform an action or acquire a benefit and to permit or deny others the right t ...

to the ''aspirin'' name there. In the United States, Bayer was still under German control—though the war disrupted the links between the American Bayer plant and the German Bayer headquarters—but phenol shortage threatened to reduce aspirin production to a trickle, and imports across the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

were blocked by the Royal Navy.

Great Phenol Plot

To secure phenol for aspirin production, and at the same time indirectly aid the German war effort, German agents in the United States orchestrated what became known as the Great Phenol Plot. By 1915, the price of phenol rose to the point that Bayer's aspirin plant was forced to drastically cut production. This was especially problematic because Bayer was instituting a new branding strategy in preparation of the expiry of the aspirin patent in the United States.

To secure phenol for aspirin production, and at the same time indirectly aid the German war effort, German agents in the United States orchestrated what became known as the Great Phenol Plot. By 1915, the price of phenol rose to the point that Bayer's aspirin plant was forced to drastically cut production. This was especially problematic because Bayer was instituting a new branding strategy in preparation of the expiry of the aspirin patent in the United States. Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

, who needed phenol to manufacture phonograph records, was also facing supply problems; in response, he created a phenol factory capable of pumping out twelve tons per day. Edison's excess phenol seemed destined for trinitrophenol

Picric acid is an organic compound with the formula (O2N)3C6H2OH. Its IUPAC name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). The name "picric" comes from el, πικρός (''pikros''), meaning "bitter", due to its bitter taste. It is one of the most acidic ...

production.

Although the United States remained officially neutral until April 1917, it was increasingly throwing its support to the Allies through trade. To counter this, German ambassador Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff

Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff (14 November 1862 – 6 October 1939) was a German politician and ambassador to the United States from 1908 to 1917.

Early life

Born in 1862 in London, he was the son of one of the most powerful politicians ...

and Interior Ministry official Heinrich Albert

Heinrich Friedrich Albert (12 February 1874 to 1 November 1960) was a German civil servant, diplomat, politician, businessman and lawyer who served as minister for reconstruction and the Treasury in the government of Wilhelm Cuno in 1922/1923. ...

were tasked with undermining American industry and maintaining public support for Germany. One of their agents was a former Bayer employee, Hugo Schweitzer. Schweitzer set up a contract for a front company called the Chemical Exchange Association to buy all of Edison's excess phenol. Much of the phenol would go to the German-owned Chemische Fabrik von Heyden's American subsidiary; Heyden was the supplier of Bayer's salicylic acid for aspirin manufacture. By July 1915, Edison's plants were selling about three tons of phenol per day to Schweitzer; Heyden's salicylic acid production was soon back on line, and in turn Bayer's aspirin plant was running as well.

The plot only lasted a few months. On 24 July 1915, Heinrich Albert's briefcase, containing details about the phenol plot, was recovered by a Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For ...

agent. Although the activities were not illegal—since the United States was still officially neutral and still trading with Germany—the documents were soon leaked to the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'', an anti-German newspaper. The ''World'' published an exposé on 15 August 1915. The public pressure soon forced Schweitzer and Edison to end the phenol deal—with the embarrassed Edison subsequently sending his excess phenol to the U.S. military—but by that time the deal had netted the plotters over two million dollars and there was already enough phenol to keep Bayer's Aspirin plant running. Bayer's reputation took a large hit, however, just as the company was preparing to launch an advertising campaign to secure the connection between aspirin and the Bayer brand.

Bayer loses foreign holdings

Beginning in 1915, Bayer set up a number ofshell corporation

A shell corporation is a company or corporation that exists only on paper and has no office and no employees, but may have a bank account or may hold passive investments or be the registered owner of assets, such as intellectual property, or s ...

s and subsidiaries in the United States, to hedge against the possibility of losing control of its American assets if the U.S. should enter the war and to allow Bayer to enter other markets (e.g., army uniforms). After the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917, alien property custodian

The Office of Alien Property Custodian was an office within the government of the United States during World War I and again during World War II, serving as a custodian to property that belonged to US enemies. The office was created in 1917 by E ...

A. Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer (May 4, 1872 – May 11, 1936), was an American attorney and politician who served as the 50th United States attorney general from 1919 to 1921. He is best known for overseeing the Palmer Raids during the Red Scare ...

began investigating German-owned businesses, and soon turned his attention to Bayer. To avoid having to surrender all profits and assets to the government, Bayer's management shifted the stock to a new company, nominally owned by Americans but controlled by the German-American Bayer leaders. Palmer, however, soon uncovered this scheme and seized all of Bayer's American holdings. After the Trading with the Enemy Act

Trading with the Enemy Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States relating to trading with the enemy.

''Trading with the Enemy Acts'' is also a generic name for a class of legislation generally pas ...

was amended to allow sale of these holdings, the government auctioned off the Rensselaer plant and all Bayer's American patents and trademarks, including even the Bayer brand name and the Bayer cross logo. It was bought by a patent medicine company, Sterling Products, Inc. The rights to Bayer Aspirin and the U.S. rights to the Bayer name and trademarks were sold back to Bayer AG in 1994 for US$1 billion.

Interwar years

With the coming of the deadly

With the coming of the deadly Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case wa ...

pandemic in 1918, aspirin—by whatever name—secured a reputation as one of the most powerful and effective drugs in the pharmacopeia of the time. Its fever-reducing properties gave many sick patients enough strength to fight through the infection, and aspirin companies large and small earned the loyalty of doctors and the public—when they could manufacture or purchase enough aspirin to meet demand. Despite this, some people believed that Germans put the Spanish flu bug in Bayer aspirin, causing the pandemic as a war tactic.

The U.S. ASA patent expired in 1917, but Sterling owned the ''aspirin'' trademark, which was the only commonly used term for the drug. In 1920,

The U.S. ASA patent expired in 1917, but Sterling owned the ''aspirin'' trademark, which was the only commonly used term for the drug. In 1920, United Drug Company

Rexall was a chain of American Pharmacy (shop), drugstores, and the name of their store-branded products. The stores, having roots in the federation of United Drug Stores starting in 1903, licensed the Rexall brand name to as many as 12,000 drug ...

challenged the ''Aspirin'' trademark, which became officially generic for public sale in the U.S. (although it remained trademarked when sold to wholesalers and pharmacists). With demand growing rapidly in the wake of the Spanish flu, there were soon hundreds of "aspirin" brands on sale in the United States.

Sterling Products, equipped with all of Bayer's U.S. intellectual property, tried to take advantage of its new brand as quickly as possible, before generic ASAs took over. However, without German expertise to run the Rensselaer plant to make aspirin and the other Bayer pharmaceuticals, they had only a finite aspirin supply and were facing competition from other companies. Sterling president William E. Weiss had ambitions to sell Bayer aspirin not only in the U.S., but to compete with the German Bayer abroad as well. Taking advantage of the losses Farbenfabriken Bayer (the German Bayer company) suffered through the reparation provisions of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, Weiss worked out a deal with Carl Duisberg to share profits in the Americas, Australia, South Africa and Great Britain for most Bayer drugs, in return for technical assistance in manufacturing the drugs.

Sterling also took over Bayer's Canadian assets as well as ownership of the Aspirin trademark which is still valid in Canada and most of the world. Bayer bought Sterling Winthrop in 1994 restoring ownership of the Bayer name and Bayer cross trademark in the US and Canada as well as ownership of the Aspirin trademark in Canada.

Diversification of market

Between World War I and

Between World War I and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, many new aspirin brands and aspirin-based products entered the market. The Australian company Nicholas Proprietary Limited, through the aggressive marketing strategies

Marketing strategy allows organizations to focus limited resources on best opportunities to increase sales and achieve a competitive advantage in the market.

Strategic marketing emerged in the 1970s/80s as a distinct field of study, further buil ...

of George Davies, built '' Aspro'' into a global brand, with particular strength in Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K. American brands such as ''Burton's Aspirin'', ''Molloy's Aspirin'', ''Cal-Aspirin'' and ''St. Joseph Aspirin'' tried to compete with the American Bayer, while new products such ''Cafaspirin'' (aspirin with caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the methylxanthine class. It is mainly used recreationally as a cognitive enhancer, increasing alertness and attentional performance. Caffeine acts by blocking binding of adenosine to ...

) and ''Alka-Seltzer

Alka-Seltzer is an effervescent antacid and pain reliever first marketed by the Dr. Miles Medicine Company of Elkhart, Indiana, United States. Alka-Seltzer contains three active ingredients: aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) (ASA), sodium bicarbona ...

'' (a soluble mix of aspirin and bicarbonate of soda) put aspirin to new uses. In 1925, the German Bayer became part of IG Farben, a conglomerate of former dye companies; IG Farben's brands of ''Aspirin'' and, in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

, the caffeinated ''Cafiaspirina'' (co-managed with Sterling Products) competed with less expensive aspirins such as ''Geniol''.

Competition from new drugs

After World War II, with the IG Farben conglomerate dismantled because of its central role in theNazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

regime, Sterling Products bought half of Bayer Ltd, the British Bayer subsidiary—the other half of which it already owned. However, ''Bayer Aspirin'' made up only a small fraction of the British aspirin market because of competition from ''Aspro'', ''Disprin'' (a soluble aspirin drug) and other brands. Bayer Ltd began searching for new pain relievers to compete more effectively. After several moderately successful compound drugs that mainly utilized aspirin ('' Anadin'' and ''Excedrin''), Bayer Ltd's manager Laurie Spalton ordered an investigation of a substance that scientists at Yale had, in 1946, found to be the metabolically active derivative of acetanilide: acetaminophen. After clinical trials, Bayer Ltd brought acetaminophen to market as ''Panadol'' in 1956.

However, Sterling Products did not market ''Panadol'' in the United States or other countries where ''Bayer Aspirin'' still dominated the aspirin market. Other firms began selling acetaminophen drugs, most significantly, McNeil Laboratories

McNeil Consumer Healthcare is an American medicals products company belonging to the Johnson & Johnson healthcare products group. It primarily sells fast-moving consumer goods such as over-the-counter drugs.

History

The company was founded on M ...

with liquid ''Tylenol Tylenol may refer to:

* Paracetamol

Paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen, is a medication used to treat fever and mild to moderate pain. Common brand names include Tylenol and Panadol.

At a standard dose, paracetamol only slightly decr ...

'' in 1955, and ''Tylenol'' pills in 1958. By 1967, ''Tylenol'' was available without a prescription. Because it did not cause gastric irritation, acetaminophen rapidly displaced much of aspirin's sales. Another analgesic, anti-inflammatory drug was introduced in 1962: ibuprofen (sold as ''Brufen'' in the U.K. and ''Motrin'' in the U.S.). By the 1970s, aspirin had a relatively small portion of the pain reliever market, and in the 1980s sales decreased even more when ibuprofen became available without prescription.

Also in the early 1980s, several studies suggested a link between children's consumption of aspirin and Reye's syndrome

Reye syndrome is a rapidly worsening encephalopathy, brain disease. Symptoms of Reye syndrome may include vomiting, personality changes, confusion, seizures, and loss of consciousness. While hepatotoxicity, liver toxicity typically occurs in the ...

, a potentially fatal disease. By 1986, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

required warning label

A warning label is a label attached to a Product (business), product, or contained in a product's Owner's manual, instruction manual, warning the user about risks associated with its use, and may include restrictions by the Manufacturing, man ...

s on all aspirin, further suppressing sales. The makers of ''Tylenol'' also filed a lawsuit against ''Anacin'' aspirin maker American Home Products

Wyeth, LLC was an American pharmaceutical company. The company was founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1860 as ''John Wyeth and Brother''. It was later known, in the early 1930s, as American Home Products, before being renamed to Wyeth i ...

, claiming that the failure to add warning labels before 1986 had unfairly held back ''Tylenol'' sales, though this suit was eventually dismissed.

Investigating how aspirin works

The mechanism of aspirin's analgesic, anti-inflammatory andantipyretic

An antipyretic (, from ''anti-'' 'against' and ' 'feverish') is a substance that reduces fever. Antipyretics cause the hypothalamus to override a prostaglandin-induced increase in temperature. The body then works to lower the temperature, which r ...

properties was unknown through the drug's heyday in the early- to mid-twentieth century; Heinrich Dreser's explanation, widely accepted since the drug was first brought to market, was that aspirin relieved pain by acting on the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all p ...

. In 1958 Harry Collier, a biochemist in the London laboratory of pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis

Parke-Davis is a subsidiary of the pharmaceutical company Pfizer. Although Parke, Davis & Co. is no longer an independent corporation, it was once America's oldest and largest drug maker, and played an important role in medical history. In 1970 ...

, began investigating the relationship between kinins and the effects of aspirin. In tests on guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus '' Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ...

s, Collier found that aspirin, if given beforehand, inhibited the bronchoconstriction

Bronchoconstriction is the constriction of the airways in the lungs due to the tightening of surrounding smooth muscle, with consequent coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath.

Causes

The condition has a number of causes, the most common be ...

effects of bradykinin

Bradykinin (BK) (Greek brady-, slow; -kinin, kīn(eîn) to move) is a peptide that promotes inflammation. It causes arterioles to dilate (enlarge) via the release of prostacyclin, nitric oxide, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor and ...

. He found that cutting the guinea pigs' vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve, cranial nerve X, or simply CN X, is a cranial nerve that interfaces with the parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. It comprises two nerves—the left and righ ...

did not affect the action of bradykinin ''or'' the inhibitory effect of aspirin—evidence that aspirin worked locally to combat pain and inflammation, rather than on the central nervous system. In 1963, Collier began working with University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

pharmacology graduate student Priscilla Piper to determine the precise mechanism of aspirin's effects. However, it was difficult to pin down the precise biochemical goings-on in live research animals, and ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called " test-tube experiments", these studies in biology ...

'' tests on removed animal tissues did not behave like ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and ...

'' tests.

After five years of collaboration, Collier arranged for Piper to work with pharmacologist John Vane

Sir John Robert Vane (29 March 1927 – 19 November 2004) was a British pharmacologist who was instrumental in the understanding of how aspirin produces pain-relief and anti-inflammatory effects and his work led to new treatments for heart and ...

at the Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wales. T ...

, in order to learn Vane's new bioassay

A bioassay is an analytical method to determine the concentration or potency of a substance by its effect on living animals or plants (''in vivo''), or on living cells or tissues(''in vitro''). A bioassay can be either quantal or quantitative, dir ...

methods, which seemed like a possible solution to the ''in vitro'' testing failures. Vane and Piper tested the biochemical cascade

A biochemical cascade, also known as a signaling cascade or signaling pathway, is a series of chemical reactions that occur within a biological cell when initiated by a stimulus. This stimulus, known as a first messenger, acts on a receptor that ...

associated with anaphylactic shock (in extracts from guinea pig lungs, applied to tissue from rabbit aorta

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes o ...

s). They found that aspirin inhibited the release of an unidentified chemical generated by guinea pig lungs, a chemical that caused rabbit tissue to contract. By 1971, Vane identified the chemical (which they called "rabbit-aorta contracting substance," or RCS) as a prostaglandin. In a 23 June 1971 paper in the journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'', Vane and Piper suggested that aspirin and similar drugs (the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs) worked by blocking the production of prostaglandins. Later research showed that NSAIDs such as aspirin worked by inhibiting cyclooxygenase

Cyclooxygenase (COX), officially known as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGS), is an enzyme (specifically, a family of isozymes, ) that is responsible for formation of prostanoids, including thromboxane and prostaglandins such as pr ...

, the enzyme responsible for converting arachidonic acid into a prostaglandin.

Revival as heart drug

Aspirin's effects onblood clotting

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanis ...

(as an antiplatelet agent

An antiplatelet drug (antiaggregant), also known as a platelet agglutination inhibitor or platelet aggregation inhibitor, is a member of a class of pharmaceuticals that decrease platelet aggregation and inhibit thrombus formation. They are effecti ...

) were first noticed in 1950 by Lawrence Craven. Craven, a family doctor

Family medicine is a medical specialty within primary care that provides continuing and comprehensive health care for the individual and family across all ages, genders, diseases, and parts of the body. The specialist, who is usually a primary ...

in California, had been directing tonsillectomy

Tonsillectomy is a list of surgical procedures, surgical procedure in which both palatine tonsils are fully removed from the back of the throat. The procedure is mainly performed for recurrent tonsillitis, throat infections and obstructive sleep ...

patients to chew Aspergum

Aspergum is the United States trademark name for an analgesic chewing gum, whose active ingredient is aspirin. Aspergum is owned by Retrobrands USA LLC.

Aspergum contained 227 mg (3½ grains) of aspirin, and was available in cherry and orang ...

, an aspirin-laced chewing gum

Chewing gum is a soft, cohesive substance designed to be chewed without being swallowed. Modern chewing gum is composed of gum base, sweeteners, softeners/ plasticizers, flavors, colors, and, typically, a hard or powdered polyol coating. Its t ...

. He found that an unusual number of patients had to be hospitalized for severe bleeding, and that those patients had been using very high amounts of Aspergum. Craven began recommending daily aspirin to all his patients, and claimed that the patients who followed the aspirin regimen (about 8,000 people) had no signs of thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (t ...

. However, Craven's studies were not taken seriously by the medical community, because he had not done a placebo

A placebo ( ) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

In general, placebos can af ...

- controlled study and had published only in obscure journals.

The idea of using aspirin to prevent clotting diseases (such as heart attacks and strokes) was revived in the 1960s, when medical researcher Harvey Weiss found that aspirin had an anti-adhesive effect on blood platelets

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek language, Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the Coagulation#Coagulation factors, coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding ...

(and unlike other potential antiplatelet drugs, aspirin had low toxicity). Medical Research Council haematologist John O'Brien picked up on Weiss's finding and, in 1963, began working with epidemiologist Peter Elwood on aspirin's anti-thrombosis drug potential. Elwood began a large-scale trial of aspirin as a preventive drug for heart attacks. Nicholas Laboratories agreed to provide aspirin tablets, and Elwood enlisted heart attack survivors in a double-blind

In a blind or blinded experiment, information which may influence the participants of the experiment is withheld until after the experiment is complete. Good blinding can reduce or eliminate experimental biases that arise from a participants' expec ...

controlled study—heart attack survivors were statistically more likely to suffer a second attack, greatly reducing the number of patients necessary to reliably detect whether aspirin had an effect on heart attacks. The study began in February 1971, though the researchers soon had to break the double-blinding when a study by American epidemiologist Hershel Jick

Hershel M. Jick (born December 1, 1931) is an American medical researcher and associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, where he was formerly the director of the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program.

Edu ...

suggested that aspirin prevented heart attacks but suggested that the heart attacks were more deadly. Jick had found that fewer aspirin-takers were admitted to his hospital for heart attacks than non-aspirin-takers, and one possible explanation was that aspirin caused heart attack sufferers to die before reaching the hospital; Elwood's initial results ruled out that explanation. When the Elwood trial ended in 1973, it showed a modest but not statistically significant reduction in heart attacks among the group taking aspirin.

Several subsequent studies put aspirin's effectiveness as a heart drug on firmer ground, but the evidence was not incontrovertible. However, in the mid-1980s, with the relatively new technique of meta-analysis

A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis that combines the results of multiple scientific studies. Meta-analyses can be performed when there are multiple scientific studies addressing the same question, with each individual study reporting me ...

, statistician Richard Peto

Sir Richard Peto (born 14 May 1943) is an English statistician and epidemiologist who is Professor of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology at the University of Oxford, England.

Education

He attended Taunton's School in Southampton and subsequ ...

convinced the U.S. FDA and much of the medical community that the aspirin studies, in aggregate, showed aspirin's effectiveness with relative certainty. By the end of the 1980s, aspirin was widely used as a preventive drug for heart attacks and had regained its former position as the top-selling analgesic in the U.S.

In 2018, three major clinical trials cast doubt on that conventional wisdom, finding few benefits and consistent bleeding risks associated with daily aspirin use. Taken together, the findings led the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology

The American College of Cardiology (ACC), based in Washington, D.C., is a nonprofit medical association established in 1949. It bestows credentials upon cardiovascular specialists who meet its qualifications. Education is a core component of the ...

to change clinical practice guidelines in early 2019, recommending against the routine use of aspirin in people older than 70 years or people with increased bleeding risk who do not have existing cardiovascular disease.Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. ScienceDaily, 22 July 2019.

References

Further reading

*External links

– Bayer-funded website with historical content

{{Webarchive, url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081014081124/http://www.bayeraspirin.com/pain/asp_history.htm , date=14 October 2008 – Bayer timeline of aspirin history

– Multimedia presentation on the history of Bayer Aspirin

The Recent History of Platelets in Thrombosis and other Disorders

– transcript of a "witness seminar" with historians and key figures in the development of aspirin therapy for thrombosis *

Aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

Bayer