Hiberno-Norman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From the 12th century onwards, a group of

From the 12th century onwards, a group of

Traditionally, London-based Anglo-Norman governments expected the Normans in the Lordship of Ireland to promote the interests of the

Traditionally, London-based Anglo-Norman governments expected the Normans in the Lordship of Ireland to promote the interests of the

Beyond the Pale, the term 'English', if and when it was applied, referred to a thin layer of landowners and nobility, who ruled over Gaelic Irish freeholders and tenants. The division between the Pale and the rest of Ireland was therefore in reality not rigid or impermeable, but rather one of gradual cultural and economic differences across wide areas. Consequently, the English identity expressed by representatives of the Pale when writing in English to the English Crown often contrasted radically with their cultural affinities and kinship ties to the Gaelic world around them, and this difference between their cultural reality and their expressed identity is a central reason for later Old English support of Roman Catholicism.

There was no religious division in medieval Ireland, beyond the requirement that English-born prelates should run the Irish church. After the

Beyond the Pale, the term 'English', if and when it was applied, referred to a thin layer of landowners and nobility, who ruled over Gaelic Irish freeholders and tenants. The division between the Pale and the rest of Ireland was therefore in reality not rigid or impermeable, but rather one of gradual cultural and economic differences across wide areas. Consequently, the English identity expressed by representatives of the Pale when writing in English to the English Crown often contrasted radically with their cultural affinities and kinship ties to the Gaelic world around them, and this difference between their cultural reality and their expressed identity is a central reason for later Old English support of Roman Catholicism.

There was no religious division in medieval Ireland, beyond the requirement that English-born prelates should run the Irish church. After the

In contrast to previous English settlers, the ''New English'', that wave of settlers who came to Ireland from England during the

In contrast to previous English settlers, the ''New English'', that wave of settlers who came to Ireland from England during the

The following is a list of Hiberno-Norman surnames, many of them unique to Ireland. For example, the prefix " Fitz" meaning "son of", in surnames like FitzGerald appears most frequently in Hiberno-Norman surnames. (cf. modern French "fils de" with the same meaning). However, a few names with the prefix "Fitz-" sound Norman but are actually of native Gaelic origin; Fitzpatrick was the surname Brian Mac Giolla Phadraig had to take as part of his submission to Henry VIII in 1537 and FitzDermot (Mac Gilla Mo-Cholmóc, of the Uí Dúnchada sept of the Uí Dúnlainge based at Lyons Hill, Co. Dublin).

* Barrett

*

The following is a list of Hiberno-Norman surnames, many of them unique to Ireland. For example, the prefix " Fitz" meaning "son of", in surnames like FitzGerald appears most frequently in Hiberno-Norman surnames. (cf. modern French "fils de" with the same meaning). However, a few names with the prefix "Fitz-" sound Norman but are actually of native Gaelic origin; Fitzpatrick was the surname Brian Mac Giolla Phadraig had to take as part of his submission to Henry VIII in 1537 and FitzDermot (Mac Gilla Mo-Cholmóc, of the Uí Dúnchada sept of the Uí Dúnlainge based at Lyons Hill, Co. Dublin).

* Barrett

*

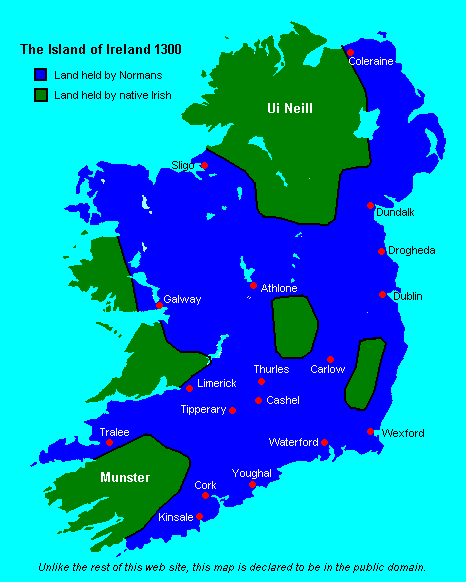

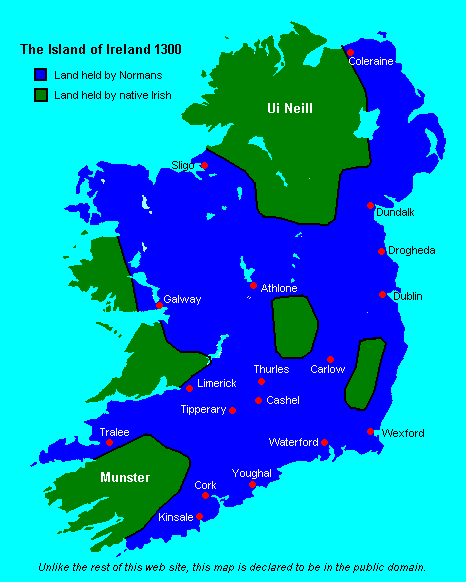

From the 12th century onwards, a group of

From the 12th century onwards, a group of Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. T ...

invaded and settled in Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans ...

. These settlers later became known as Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans. They originated mainly among Cambro-Norman families in Wales and Anglo-Normans

The Anglo-Normans ( nrf, Anglo-Normaunds, ang, Engel-Norðmandisca) were the medieval ruling class in England, composed mainly of a combination of ethnic Normans, French, Anglo-Saxons, Flemings and Bretons, following the Norman conquest. A ...

from England, who were loyal to the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

, and the English state supported their claims to territory in the various realms then comprising Ireland. During the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD ...

and Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

the Hiberno-Normans constituted a feudal aristocracy and merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, ...

, known as the Lordship of Ireland. In Ireland, the Normans were also closely associated with the Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–80, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be na ...

of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in Ireland. Over time the descendants of the 12th-century Norman settlers spread throughout Ireland and around the world, as part of the Irish diaspora

The Irish diaspora ( ga, Diaspóra na nGael) refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner and Meeder, The ...

; they ceased, in most cases, to identify as Norman, Cambro-Norman or Anglo-Norman.

The dominance of the Norman Irish declined during the 16th century, after a new English Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

elite settled in Ireland during the Tudor period

The Tudor period occurred between 1485 and 1603 in England and Wales and includes the Elizabethan period during the reign of Elizabeth I until 1603. The Tudor period coincides with the dynasty of the House of Tudor in England that began with t ...

. Some of the Norman Irishoften known as The Old Englishhad become Gaelicised by merging culturally and intermarrying with the Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic lan ...

, under the denominator of " Irish Catholic". Conversely, some Hiberno-Normans assimilated into the new English Protestant elite, as the Anglo-Irish.

Some of the most prominent Norman families were the FitzMaurices, FitzGeralds, Burkes (de Burghs), Butlers, Fitzsimmons and Wall family. One of the most common Irish surnames, Walsh, derives from the Normans based in Wales who arrived in Ireland as part of this group.

Etymology

Historians disagree about what to call the Normans in Ireland at different times in its existence, and in how to define this community's sense of collective identity. In his book ''Surnames of Ireland'', Irish historian Edward MacLysaght makes a distinction between Hiberno-Norman and Anglo-Norman surnames. This sums up the fundamental difference between "Queen's English Rebels" and the Loyal Lieges. The Geraldines ofDesmond Desmond or Desmond's may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Desmond'' (novel), 1792 novel by Charlotte Turner Smith

* '' Desmond's'', 1990s British television sitcom

Ireland

* Kingdom of Desmond, medieval Irish kingdom

* Earl of Desmond, Iris ...

or the Burkes of Connacht, for instance, could not accurately be described as Old English, for that was not their political and cultural world. The Butlers of Ormond, on the other hand, could not accurately be described as Hiberno-Norman in their political outlook and alliances, especially after they married into the Royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term p ...

.

Some historians now refer to them as Cambro-Normans – Seán Duffy of Trinity College Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

, invariably uses that term. After many centuries in Ireland and just a century in Wales or England it appears odd that their entire history since 1169 is known by the description ''Old English'', which only came into use in the late 16th century. Some contend it is ahistorical to trace a single Old English community back to 1169, for the real Old English community was a product of the late sixteenth century in the Pale. Up to that time the identity of such people had been much more fluid; it was the administration's policies which created an oppositional and clearly defined Old English community.

Brendan Bradshaw, in his study of the poetry of late-16th century , points out that the Normans were not referred to there as ("Old Foreigners") but rather as '' and ''. He argued in a lecture to the Mícheál Ó Cléirigh Institute in University College, Dublin

University College Dublin (commonly referred to as UCD) ( ga, Coláiste na hOllscoile, Baile Átha Cliath) is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 33,284 students ...

that the poets referred in that way to hibernicised people of Norman stock in order to grant them a longer vintage in Ireland than the ( meaning 'fair-haired Foreigners', i.e. Norwegian Vikings; meaning 'black-haired Foreigners', i.e. Danish Vikings). This follows on from his earlier arguments that the term (Irish people) as we currently know it also emerged during this period in the poetry books of the of Wicklow, as a sign of unity between Gaeil and Gaill; he viewed it as a sign of an emerging Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

. essentially agreed with him, Tom Dunne and Tom Bartlett were less sure.

It was noted in 2011 that Irish nationalist politicians elected between 1918 and 2011 could often be distinguished by surname. parliamentarians were more likely to bear surnames of Norman origin than those from , who had a higher concentration of Gaelic surnames.

"Old English" vs. New English

The term Old English ( ga, Seanghaill, meaning 'old foreigners') began to be applied by scholars for Norman-descended residents ofThe Pale

The Pale ( Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast s ...

and Irish towns after the mid-16th century, who became increasingly opposed to the Protestant " New English" who arrived in Ireland after the Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, ...

in the 16th and 17th centuries. Many of the Old English were dispossessed in the political and religious conflicts of the 16th and 17th centuries, largely due to their continued adherence to the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

religion. As a result, those loyal to Catholicism attempted to replace the distinction between "Norman" and "Gaelic Irish" under the new denominator of Irish Catholic by 1700, as they were both barred from positions of wealth and power by the so-called New English settlers, who became known as the Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

.

The earliest known reference to the term "Old English" is in the 1580s. The community of Norman descent prior to then used numerous epithets to describe themselves (such as "Englishmen born in Ireland" or "English-Irish"), but it was only as a result of the political cess crisis of the 1580s that a group identifying itself as the Old English community actually emerged.

History

Normans in medieval Ireland

Traditionally, London-based Anglo-Norman governments expected the Normans in the Lordship of Ireland to promote the interests of the

Traditionally, London-based Anglo-Norman governments expected the Normans in the Lordship of Ireland to promote the interests of the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

, through the use of the English language (despite the fact that they spoke Norman-French rather than English), law, trade, currency, social customs, and farming methods. The Norman community in Ireland was, however, never monolithic. In some areas, especially in the Pale around Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, and in relatively urbanised communities in Kilkenny, Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

, Cork and south Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N1 ...

, people spoke the English language (though sometimes in arcane local dialects such as Yola), used English law, and in some respects lived in a manner similar to that found in England.

However, in the provinces, the Normans in Ireland ( meaning "foreigners") were at times indistinguishable from the surrounding Gaelic lords and chieftains. Dynasties such as the Fitzgeralds, Butlers, Burkes, and Walls adopted the native language, legal system

The contemporary national legal systems are generally based on one of four basic systems: civil law, common law, statutory law, religious law or combinations of these. However, the legal system of each country is shaped by its unique history an ...

, and other customs such as fostering and intermarriage with the Gaelic Irish and the patronage of Irish poetry

Irish poetry is poetry written by poets from Ireland. It is mainly written in Irish and English, though some is in Scottish Gaelic and some in Hiberno-Latin. The complex interplay between the two main traditions, and between both of them and ...

and music. Such people became regarded as " more Irish than the Irish themselves" as a result of this process (see also History of Ireland (1169–1536)

The history of Ireland from 1169– 1536 covers the period from the arrival of the Cambro-Normans to the reign of Henry VIII of England, who made himself King of Ireland. After the Norman invasions of 1169 and 1171, Ireland was under an a ...

). The most accurate name for the community throughout the late medieval period was Hiberno-Norman, a name which captures the distinctive blended culture which this community created and within which it operated. In an effort to halt the ongoing Gaelicisation of the Anglo-Norman community, the Irish Parliament passed the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1367, which among other things banned the use of the Irish language, the wearing of Irish clothes, as well as prohibiting the Gaelic Irish from living within walled towns.

The Pale

Despite these efforts, by 1515, one official lamented, that "all the common people of the said half counties" f The Pale"that obeyeth the King's laws, for the most part be of Irish birth, of Irish habit, and of Irish language." English administrators such asFynes Moryson

Fynes Moryson (or Morison) (1566 – 12 February 1630) spent most of the decade of the 1590s travelling on the European continent and the eastern Mediterranean lands. He wrote about it later in his multi-volume ''Itinerary'', a work of value to ...

, writing in the last years of the sixteenth century, shared the latter view of what he termed the ''English-Irish'': "the English Irish and the very citizens (excepting those of Dublin where the lord deputy resides) though they could speak English as well as we, yet commonly speak Irish among themselves, and were hardly induced by our familiar conversation to speak English with us". Moryson's views on the cultural fluidity of the so-called ''English Pale'' were echoed by other commentators such as Richard Stanihurst who, while protesting the Englishness of the Palesmen in 1577, opined that ''Irish was universally gaggled in the English Pale''.

Beyond the Pale, the term 'English', if and when it was applied, referred to a thin layer of landowners and nobility, who ruled over Gaelic Irish freeholders and tenants. The division between the Pale and the rest of Ireland was therefore in reality not rigid or impermeable, but rather one of gradual cultural and economic differences across wide areas. Consequently, the English identity expressed by representatives of the Pale when writing in English to the English Crown often contrasted radically with their cultural affinities and kinship ties to the Gaelic world around them, and this difference between their cultural reality and their expressed identity is a central reason for later Old English support of Roman Catholicism.

There was no religious division in medieval Ireland, beyond the requirement that English-born prelates should run the Irish church. After the

Beyond the Pale, the term 'English', if and when it was applied, referred to a thin layer of landowners and nobility, who ruled over Gaelic Irish freeholders and tenants. The division between the Pale and the rest of Ireland was therefore in reality not rigid or impermeable, but rather one of gradual cultural and economic differences across wide areas. Consequently, the English identity expressed by representatives of the Pale when writing in English to the English Crown often contrasted radically with their cultural affinities and kinship ties to the Gaelic world around them, and this difference between their cultural reality and their expressed identity is a central reason for later Old English support of Roman Catholicism.

There was no religious division in medieval Ireland, beyond the requirement that English-born prelates should run the Irish church. After the Henrician Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and pol ...

of the 1530s, however, most of the pre-16th century inhabitants of Ireland continued their allegiance to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, even after the establishment of the Protestant Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, and its Irish counterpart, the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second l ...

.

Tudor conquest and arrival of New English

In contrast to previous English settlers, the ''New English'', that wave of settlers who came to Ireland from England during the

In contrast to previous English settlers, the ''New English'', that wave of settlers who came to Ireland from England during the Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personif ...

era onwards as a result of the Tudor conquest of Ireland, were more self-consciously English, and were largely (though not entirely) Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. To the New English, many of the Old English were "degenerate", having adopted Irish customs as well as choosing to adhere to Roman Catholicism after the Crown's official split with Rome. The poet Edmund Spenser was one of the chief advocates of this view. He argued in ''A View on the Present State of Ireland'' (1595) that a failure to conquer Ireland fully in the past had led previous generations of English settlers to become corrupted by the native Irish culture. In the course of the 16th century, the religious division had the effect of alienating the Old English from the state, and eventually propelled them into making common cause with the Gaelic Irish as Irish Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

s.

Cess crisis

The first confrontation between the Old English and the English government in Ireland came with the cess crisis of 1556–1583. During that period, the Pale community resisted paying for the English army sent to Ireland to put down a string of revolts which culminated in the Desmond Rebellions (1569–73 and 1579–83). The term "Old English" was coined at this time, as the Pale community emphasised their English identity and loyalty to the Crown, while, at the same time, contradictorily they refused to co-operate with the wishes of the English Crown as represented in Ireland by theLord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland. The plural form is ...

.

Originally, the conflict was a civil issue, as the Palesmen objected to paying new taxes that had not first been approved by them in the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two cham ...

. The dispute, however, also soon took on a religious dimension, especially after 1570, when Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

's papal bull '' Regnans in Excelsis''. In response, Elizabeth banned the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

from her realms as they were seen as being among the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

's most radical agents of the Counter Reformation which, among other aims, sought to topple her from her thrones. Rebels such as James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald portrayed their rebellion as a "Holy War", and indeed received money and troops from the papal coffers. In the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–83), a prominent Pale lord, James Eustace, Viscount of Baltinglass, joined the rebels from religious motivation. Before the rebellion was over, several hundred Old English Palesmen had been arrested and sentenced to death, either for outright rebellion, or because they were suspected rebels because of their religious views. Most were eventually pardoned after paying fines of up to 100 pounds, a very large sum for the time. However, twenty landed gentlemen from some of the Pale's leading, Old English families were executed – some of them, "died in the manner of" oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

"Catholic martyrs, proclaiming they were suffering for their religious beliefs".

This episode marked an important break between the Pale and the English regime in Ireland, and between the Old English and the New English.

In the subsequent Nine Years' War (1594–1603), the Pale and the Old English towns remained loyal in favour of outward loyalty to the English Crown during another rebellion.

Establishment of Protestantism

In the end, however, it was the re-organisation of the English government's administration in Ireland along Protestant lines in the early 17th century that eventually severed the main political ties between the Old English and England itself, particularly following the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. First, in 1609, Roman Catholics were banned from holding public office in Ireland. Then, in 1613, the constituencies of the Irish Parliament were changed so that the New English Anglicans would have a slight majority in theIrish House of Commons

The Irish House of Commons was the lower house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from 1297 until 1800. The upper house was the House of Lords. The membership of the House of Commons was directly elected, but on a highly restrictive fr ...

. Thirdly, in the 1630s, many members of the Old English landowning class were forced to confirm the ancient title to their land-holdings often in the absence of title deeds, which resulted in some having to pay substantial fines to retain their property, while others ended up losing some or all of their land in this complex legal process (see Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, an ...

).

The political response of the Old English community was to appeal directly to the King of Ireland in England, over the heads of his representatives in Dublin, effectively meaning that they had to appeal to their sovereign in his role as King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Baili ...

, a necessity which further disgruntled them.

First from James I, and then from his son and successor, Charles I, they sought a package of reforms, known as The Graces, which included provisions for religious toleration and civil equality for Roman Catholics in return for their payment of increased taxes. On several occasions in the 1620s and 1630s, however, after they had agreed to pay the higher taxes to the Crown, they found that the Monarch or his Irish viceroy chose instead to defer some of the agreed concessions. This was to prove culturally counterproductive for the cause of the English administration in Ireland, as it led to Old English writers, such as Geoffrey Keating to argue (as Keating did in ''Foras Feasa ar Éirinn'' (1634)), that the true identity of the Old English was now Roman Catholic and Irish, rather than English. English policy thus hastened the assimilation of the Old English with the native Irish.

Dispossession and defeat

In 1641, many of the Old English community made a decisive break with their past as loyal subjects by joining theIrish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantat ...

. Many factors influenced the decision of the Old English to join in the rebellion; among these were fear of the rebels and fear of government reprisals against all Roman Catholics. The main long-term reason was, however, a desire to reverse the anti-Roman Catholic policies that had been pursued by the English authorities over the previous 40 years in carrying out their administration of Ireland. Nevertheless, despite their formation of an Irish government in Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristocrats, landed gentry, clergy and military ...

, the Old English identity was still an important division within the Irish Roman Catholic community. During the Irish Confederate Wars

The Irish Confederate Wars, also called the Eleven Years' War (from ga, Cogadh na hAon-déag mBliana), took place in Ireland between 1641 and 1653. It was the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of civil wars in the kin ...

(1641–53), the Old English were often accused by the Gaelic Irish of being too ready to sign a treaty with Charles I of England at the expense of the interests of Irish landowners and the Roman Catholic religion. The ensuing Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland w ...

(1649–53), saw the ultimate defeat of the Roman Catholic cause and the almost wholesale dispossession of the Old English nobility. While this cause was briefly revived before the Williamite war in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691; ga, Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"), was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called the ...

(1689–91), by 1700, the Anglican descendants of the New English had become the dominant class in the country, along with the Old English families (and men of Gaelic origin such as William Conolly) who chose to comply with the new realities by conforming to the Established Church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a ...

.

Protestant Ascendancy

In the course of the eighteenth century under the Protestant Ascendancy, social divisions were defined almost solely in sectarian terms of Roman Catholic, Anglican and Protestant Nonconformist, rather than ethnic ones. Against the backdrop of the Penal Laws (Ireland) which discriminated against them both, and a country becoming increasinglyAnglicized

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

, the old distinction between Old English and Gaelic Irish Roman Catholics gradually faded away,

Changing religion, or rather conforming to the State Church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a ...

, was always an option for any of the King of Ireland's subjects, and an open avenue to inclusion in the officially recognised "body politic", and, indeed, many Old English such as Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January New Style">NS/nowiki> 1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish people">Anglo-Irish Politician">statesman, economist, and philosopher. Born in Dublin, Burke served as a member of Parliament (MP) between 1766 and 1794 ...

were newly-conforming Anglicans who retained a certain sympathy and understanding for the difficult position of Roman Catholics, as Burke did in his parliamentary career. Others in the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

such as the Viscounts Dillon and the Lords Dunsany belonged to Old English families who had originally undergone a religious conversion from Rome to Canterbury to save their lands and titles. Some members of the ''Old English'' who had thus gained membership in the Irish Ascendancy even became adherents of the cause of Irish independence. Whereas the Old English FitzGerald Dukes of Leinster held the premier title in the Irish House of Lords

The Irish House of Lords was the upper house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from medieval times until 1800. It was also the final court of appeal of the Kingdom of Ireland.

It was modelled on the House of Lords of England, with mem ...

when it was abolished in 1800, a scion of that Ascendancy family, the Irish nationalist Lord Edward Fitzgerald, was a brother of the second duke.

Norman surnames in Ireland

The following is a list of Hiberno-Norman surnames, many of them unique to Ireland. For example, the prefix " Fitz" meaning "son of", in surnames like FitzGerald appears most frequently in Hiberno-Norman surnames. (cf. modern French "fils de" with the same meaning). However, a few names with the prefix "Fitz-" sound Norman but are actually of native Gaelic origin; Fitzpatrick was the surname Brian Mac Giolla Phadraig had to take as part of his submission to Henry VIII in 1537 and FitzDermot (Mac Gilla Mo-Cholmóc, of the Uí Dúnchada sept of the Uí Dúnlainge based at Lyons Hill, Co. Dublin).

* Barrett

*

The following is a list of Hiberno-Norman surnames, many of them unique to Ireland. For example, the prefix " Fitz" meaning "son of", in surnames like FitzGerald appears most frequently in Hiberno-Norman surnames. (cf. modern French "fils de" with the same meaning). However, a few names with the prefix "Fitz-" sound Norman but are actually of native Gaelic origin; Fitzpatrick was the surname Brian Mac Giolla Phadraig had to take as part of his submission to Henry VIII in 1537 and FitzDermot (Mac Gilla Mo-Cholmóc, of the Uí Dúnchada sept of the Uí Dúnlainge based at Lyons Hill, Co. Dublin).

* Barrett

* Barry Barry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Barry (name), including lists of people with the given name, nickname or surname, as well as fictional characters with the given name

* Dancing Barry, stage name of Barry Richards (born c. 195 ...

* Bennett

* Blake

* Blanchfield

* Bodkin

* Browne

* Bruce

* Burke and Bourke (deriving from de Burgh/de Búrca/ de Burgo)

* Butler

* Curtis

* D'Alton

* D'Arcy

* Cogan

* Clare Clare may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Clare Range, a mountain range in Victoria Land

Australia

* Clare, South Australia, a town in the Clare Valley

* Clare Valley, South Australia

Canada

* Clare (electoral district), an electoral district

* Cl ...

* Candon

* Cantillon

* Colbert

* Costello

* Cusack

Cusack is an Irish family name of Norman origin, originally from Cussac in Guienne ( Aquitaine), France. The surname died out in England, but is still common in Ireland, where it was imported at the time of the Norman invasion of Ireland in ...

* Lacy

Lacy may refer to any of the following:

People Surname

* Alan J. Lacy (born 1953), American businessman

* Antonio Lacy (born 1957), Spanish doctor and surgeon

* Arthur J. Lacy (1876–1975), American politician and lawyer

* Benjamin W. Lacy (1 ...

* Delaney

* Dillon

* Devereux

Devereux is a Norman surname found frequently in Ireland, Wales, England and around the English-speaking world. The name may derive as a Norman French rendering of the Welsh name "''Dyfrig''" or "''Dubricius''". This name would have been famil ...

* Deane

* English

* Fagan

* Fanning

* Fay

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, English, and French folklore), a form of spirit, o ...

* Finglas

Finglas (; ) is a northwestern outer suburb of Dublin, Ireland. It lies close to Junction 5 of the M50 motorway, and the N2 road. Nearby suburbs include Glasnevin and Ballymun; Dublin Airport is to the north. Finglas lies mainly in the p ...

* FitzGerald

The FitzGerald/FitzMaurice Dynasty is a noble and aristocratic dynasty of Cambro-Norman, Anglo-Norman and later Hiberno-Norman origin. They have been peers of Ireland since at least the 13th century, and are described in the Annals of the ...

* FitzGibbons

* FitzHenry

* FitzMaurice

* FitzRalph

* Fitzrichard

* FitzRoy

* FitzSimons

Fitzsimons (also spelled FitzSimons, Fitzsimmons or FitzSimmons) is a surname of Norman origin common in both Ireland and England. The name is a variant of "Sigmundsson", meaning son of Sigmund. The Gaelicisation of this surname is Mac Shíom� ...

* FitzStephen

* FitzWilliam

* French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

* Gault

* Goggin

* Grace

* Hussey

*Hand

*Harris

*Harpur

* Hore

Hore is an English surname, a variant of Hoare, and is derived from the Middle English '' hor(e)'' meaning grey- or white-haired. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew Hore (born 1978), New Zealand rugby player, brother of Charlie

* ...

*Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

* Joyce

* Lawless

* Lambart

* Lambert

Lambert may refer to

People

*Lambert (name), a given name and surname

* Lambert, Bishop of Ostia (c. 1036–1130), became Pope Honorius II

*Lambert, Margrave of Tuscany ( fl. 929–931), also count and duke of Lucca

*Lambert (pianist), stage-name ...

* Grace

* Lovett

* Mansell Mansell is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Clint Mansell (born 1963), British musician and composer

* Chris Mansell (born 1953), Australian poet

* Francis Mansell (1579–1665), Principal of Jesus College, Oxford

* Gerard M ...

* Marmion

* Marren

Marren is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Adrian Marren, Irish Gaelic footballer

* Amy Marren (born 1998), British Paralympic swimmer

* Enda Marren (1934–2013), Irish solicitor and member of the Irish Council of State

S ...

* Martin

* Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market t ...

* Bissett

* Mee

* Mohan

* Nagle

* Nangle

* Neville

* Nicolas

* Nugent

* Payne

* Peppard

* Perrin

* Petitt

* Plunkett

* Power

* Prendergast

* Preston

* Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer.

Purcell's style of Baroque music was uniquely English, although it incorporated Italian and French elements. Generally considered among the greatest E ...

* Redmond

* Tuite

* Roach

* Rochford

* Rossiter

* Russell

Russell may refer to:

People

* Russell (given name)

* Russell (surname)

* Lady Russell (disambiguation)

* Lord Russell (disambiguation)

Places Australia

*Russell, Australian Capital Territory

*Russell Island, Queensland (disambiguation)

**Ru ...

* St. Leger

* Savage

* Seagrave

* Shortall

* Sinnott

* Stack

* Taaffe

* Talbot

* Testard

* Tyrrell

* Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Çan ...

* Tobin

* Wall

* Walsh

* Warren

* Wolfe

* White

Hiberno-Norman texts

The annals of Ireland make a distinction between ''Gaill'' and ''Sasanaigh''. The former were split into ''Fionnghaill'' or ''Dubhghaill'', depending upon how much the poet wished to flatter his patron. There are a number of texts in Hiberno-Norman French, most of them administrative (including commercial) or legal, although there are a few literary works as well. There is a large amount of parliamentary legislation, including the famous Statute of Kilkenny and municipal documents. The major literary text is '' The Song of Dermot and the Earl'', achanson de geste

The ''chanson de geste'' (, from Latin 'deeds, actions accomplished') is a medieval narrative, a type of epic poem that appears at the dawn of French literature. The earliest known poems of this genre date from the late 11th and early 12th ce ...

of 3,458 lines of verse concerning Dermot McMurrough and Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (known as "Strongbow"). Other texts include the ''Walling of New Ross'' composed about 1275, and early 14th century poems about the customs of Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

.

See also

* ''The Deeds of the Normans in Ireland

''The Song of Dermot and the Earl'' (french: Chanson de Dermot et du comte) is an anonymous Anglo-Norman verse chronicle written in the early 13th century in England. It tells of the arrival of Richard de Clare (Strongbow) in Ireland in 1170 (the ...

''

* Later Medieval Ireland (1185 to 1284)

* Tribes of Galway

* Irish nobility

* Norman Ireland

Normans elsewhere

* Italo-Norman

* Scoto-Norman

References

Further reading

* {{Nobility by nation Normans in Ireland * Normans Hiberno-Norman Ethnic groups in Ireland