Herbert Maryon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Herbert James Maryon (9 March 187414 July 1965) was an English sculptor, conservator, goldsmith, archaeologist and authority on ancient metalwork. Maryon practiced and taught sculpture until retiring in 1939, then worked as a conservator with the

From 1900 until 1939, Maryon held various positions teaching sculpture, design, and metalwork. During this time, and while still in school beforehand, he created and exhibited many of his own works. At the end of 1899 he displayed a silver cup and a shield of arms with silver

From 1900 until 1939, Maryon held various positions teaching sculpture, design, and metalwork. During this time, and while still in school beforehand, he created and exhibited many of his own works. At the end of 1899 he displayed a silver cup and a shield of arms with silver

Particularly in more utilitarian works, Maryon's designs at the Keswick School tended to emphasise form over design. As he would write a decade later, " er-insistence on technique, craftsmanship which proclaims 'How clever am I!' quite naturally elbows out artistic feeling. One idea must be the principal one; and if that happens to be technique, the other goes." Design should be determined by intention, he wrote: as an objet or as an object for use. Hot water jugs, tea pots, sugar bowls and other tableware that Maryon designed were frequently raised from a single sheet of metal, retaining the hammer marks and a dull lustre. Many of these were displayed at the 1902 Home Arts and Industries Exhibition, where the school won 65 awards, along with an altar cross designed by Maryon for

Particularly in more utilitarian works, Maryon's designs at the Keswick School tended to emphasise form over design. As he would write a decade later, " er-insistence on technique, craftsmanship which proclaims 'How clever am I!' quite naturally elbows out artistic feeling. One idea must be the principal one; and if that happens to be technique, the other goes." Design should be determined by intention, he wrote: as an objet or as an object for use. Hot water jugs, tea pots, sugar bowls and other tableware that Maryon designed were frequently raised from a single sheet of metal, retaining the hammer marks and a dull lustre. Many of these were displayed at the 1902 Home Arts and Industries Exhibition, where the school won 65 awards, along with an altar cross designed by Maryon for

From 1907 until 1927, Maryon taught sculpture, including metalwork, modelling, and casting, at the

From 1907 until 1927, Maryon taught sculpture, including metalwork, modelling, and casting, at the

In 1927 Maryon left the University of Reading and began teaching sculpture at Armstrong College, then part of Durham University, where he stayed until 1939. At Durham he was both master of sculpture, and lecturer in anatomy and the history of sculpture. In 1933 he published his second book, ''Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals''. Maryon wrote that his aim was to discuss modern sculpture "from the point of view of the sculptors themselves", rather than from an "archaeological or biographical" perspective. The book received mixed reviews. To '' The Art Digest'', Maryon "succeeded in trying to make sculpture intelligible to the layman". But his treatment of criticism as secondary to intent meant grouping together artworks of unequal quality. Some critics attacked his taste, with ''The New Statesman and Nation'' claiming that " can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow," ''The Bookman'' that "All the bad sculptors... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book... Most of the good sculptors are here as well (even

In 1927 Maryon left the University of Reading and began teaching sculpture at Armstrong College, then part of Durham University, where he stayed until 1939. At Durham he was both master of sculpture, and lecturer in anatomy and the history of sculpture. In 1933 he published his second book, ''Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals''. Maryon wrote that his aim was to discuss modern sculpture "from the point of view of the sculptors themselves", rather than from an "archaeological or biographical" perspective. The book received mixed reviews. To '' The Art Digest'', Maryon "succeeded in trying to make sculpture intelligible to the layman". But his treatment of criticism as secondary to intent meant grouping together artworks of unequal quality. Some critics attacked his taste, with ''The New Statesman and Nation'' claiming that " can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow," ''The Bookman'' that "All the bad sculptors... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book... Most of the good sculptors are here as well (even  Maryon expressed an interest in archaeology while at Armstrong. By the early 1930s he was conducting

Maryon expressed an interest in archaeology while at Armstrong. By the early 1930s he was conducting

From 1945 to 1946, Maryon spent six continuous months reconstructing the

From 1945 to 1946, Maryon spent six continuous months reconstructing the

Maryon finally left the British Museum in 1961, a year after his official retirement. He donated a number of items to the museum, including plaster maquettes by George Frampton of Comedy and Tragedy, used for the memorial to Sir

Maryon finally left the British Museum in 1961, a year after his official retirement. He donated a number of items to the museum, including plaster maquettes by George Frampton of Comedy and Tragedy, used for the memorial to Sir

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

from 1944 to 1961. He is best known for his work on the Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a ...

ship-burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as the tomb for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave. This style of burial was pr ...

, which led to his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

.

By the time of his mid-twenties Maryon attended three art schools, apprenticed in silversmithing with C. R. Ashbee

Charles Robert Ashbee (17 May 1863 – 23 May 1942) was an English architect and designer who was a prime mover of the Arts and Crafts movement, which took its craft ethic from the works of John Ruskin and its co-operative structure from the soci ...

and worked in Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

's workshop. From 1900 to 1904 he served as the director of the Keswick School of Industrial Art

Keswick School of Industrial Art (KSIA) was founded in 1884 by Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley and his wife Edith as an evening class in woodwork and Repoussé and chasing, repoussé metalwork at the Crosthwaite Parish Rooms, in Keswick, Cumbria.Bott, p ...

, where he designed numerous Arts and Crafts

A handicraft, sometimes more precisely expressed as artisanal handicraft or handmade, is any of a wide variety of types of work where useful and decorative objects are made completely by one’s hand or by using only simple, non-automated re ...

works. After moving to the University of Reading

The University of Reading is a public university in Reading, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1892 as University College, Reading, a University of Oxford extension college. The institution received the power to grant its own degrees in 192 ...

and then Durham University

, mottoeng = Her foundations are upon the holy hills (Psalm 87:1)

, established = (university status)

, type = Public

, academic_staff = 1,830 (2020)

, administrative_staff = 2,640 (2018/19)

, chancellor = Sir Thomas Allen

, vice_chan ...

, he taught sculpture, metalwork, modelling, casting, and anatomy until 1939. He also designed the University of Reading War Memorial

The University of Reading War Memorial is a clock tower, designed by Herbert Maryon and situated on the London Road Campus of the University of Reading. Initially designed as a First World War memorial and dedicated in June 1924, it was later e ...

, among other commissions. Maryon published two books while teaching, including ''Metalwork and Enamelling'', and many other articles. He frequently led archaeological digs, and in 1935 discovered one of the oldest gold ornaments known in Britain while excavating the Kirkhaugh cairns

The Kirkhaugh cairns are two, or possibly three, Bronze Age burials located in Kirkhaugh, Northumberland. The two confirmed graves were excavated in 1935 and re-excavated in 2014. The first grave, dubbed Cairn 1, contained grave goods consistent wi ...

.

In 1944 Maryon was brought out of retirement to work in the Sutton Hoo finds. His responsibilities included restoring the shield, the drinking horns, and the iconic Sutton Hoo helmet

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a decorated Anglo-Saxon helmet found during a 1939 excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. It was buried around 625 and is widely associated with King Rædwald of East Anglia; its elaborate decoration may have giv ...

, which proved academically and culturally influential. Maryon's work, much of which was revised in the 1970s, created credible renderings upon which subsequent research relied; likewise, one of his papers coined the term ''pattern welding

Pattern welding is the practice in sword and knife making of forming a blade of several metal pieces of differing composition that are forge welding, forge-welded together and twisted and manipulated to form a pattern. Often mistakenly called Dam ...

'' to describe a method employed on the Sutton Hoo sword to decorate and strengthen iron and steel. The initial work ended in 1950, and Maryon turned to other matters. He proposed a widely publicised theory in 1953 on the construction of the Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes ( grc, ὁ Κολοσσὸς Ῥόδιος, ho Kolossòs Rhódios gr, Κολοσσός της Ρόδου, Kolossós tes Rhódou) was a statue of the Greek sun-god Helios, erected in the city of Rhodes (city), Rhodes, on ...

, influencing Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarr ...

and others, and restored the Roman Emesa helmet in 1955. He left the museum in 1961, a year after his official retirement, and began an around-the-world trip lecturing and researching Chinese magic mirror

The Chinese magic mirror () traces back to at least the 5th century, although their existence during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 24 AD) has been claimed. The mirrors were made out of solid bronze. The front was polished and could be used as a mi ...

s.

Early life and education

Herbert James Maryon was born in London on 9March 1874. He was the third of six surviving children born to John Simeon Maryon, a tailor, and Louisa Maryon (née Church). He had an older brother, John Ernest, and an older sister, Louisa Edith, the latter of whom preceded him in his vocation as a sculptor. Another brother and three sisters were born after him—in order, George Christian, Flora Mabel, Mildred Jessie, and Violet Mary—although Flora Maryon, born in 1878, died in her second year. According to a pedigree compiled by John Ernest Maryon, the Maryons traced back to the de Marinis family, a branch of which left Normandy for England around the 12th century. After receiving his general education at The Lower School of John Lyon, Herbert Maryon studied from 1896 to 1900 at the Polytechnic (probablyRegent Street

Regent Street is a major shopping street in the West End of London. It is named after George, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and was laid out under the direction of the architect John Nash and James Burton. It runs from Waterloo Place ...

), The Slade

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

, Saint Martin's School of Art

Saint Martin's School of Art was an art college in London, England. It offered foundation and degree level courses. It was established in 1854, initially under the aegis of the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. Saint Martin's became part of t ...

, and, under the tutelage of Alexander Fisher and William Lethaby

William Richard Lethaby (18 January 1857 – 17 July 1931) was an English architect and architectural historian whose ideas were highly influential on the late Arts and Crafts and early Modern movements in architecture, and in the fields of con ...

, the Central School of Arts and Crafts

The Central School of Art and Design was a public school of fine and applied arts in London, England. It offered foundation and degree level courses. It was established in 1896 by the London County Council as the Central School of Arts and Cr ...

. Under Fisher in particular, Maryon learned enamelling

Vitreous enamel, also called porcelain enamel, is a material made by melting, fusing powdered glass to a substrate by firing, usually between . The powder melts, flows, and then hardens to a smooth, durable vitrification, vitreous coating. The wo ...

. Maryon further received a one-year silversmithing apprenticeship in 1898, at C. R. Ashbee

Charles Robert Ashbee (17 May 1863 – 23 May 1942) was an English architect and designer who was a prime mover of the Arts and Crafts movement, which took its craft ethic from the works of John Ruskin and its co-operative structure from the soci ...

's Essex House Guild of Handicrafts, and worked for a period of time in Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

's workshop. At some point, though perhaps later, Maryon also worked in the workshop of George Frampton

Sir George James Frampton, (18 June 1860 – 21 May 1928) was a British sculptor. He was a leading member of the New Sculpture movement in his early career when he created sculptures with elements of Art Nouveau and Symbolism, often combining ...

, and was taught by Robert Catterson Smith.

Sculpture

From 1900 until 1939, Maryon held various positions teaching sculpture, design, and metalwork. During this time, and while still in school beforehand, he created and exhibited many of his own works. At the end of 1899 he displayed a silver cup and a shield of arms with silver

From 1900 until 1939, Maryon held various positions teaching sculpture, design, and metalwork. During this time, and while still in school beforehand, he created and exhibited many of his own works. At the end of 1899 he displayed a silver cup and a shield of arms with silver cloisonné

Cloisonné () is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inlays of cut gemstones, ...

at the sixth exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was formed in London in 1887 to promote the exhibition of decorative arts alongside fine arts. The Society's exhibitions were held annually at the New Gallery (London), New Gallery from 1888 to 1890, and roug ...

, an event held at the New Gallery which also included a work by his sister Edith. The exhibition was reviewed by ''The International Studio'', with Maryon's work singled out as "agreeable".

Keswick School of Industrial Art, 1900–1904

In March 1900 Maryon became the first director of theKeswick School of Industrial Art

Keswick School of Industrial Art (KSIA) was founded in 1884 by Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley and his wife Edith as an evening class in woodwork and Repoussé and chasing, repoussé metalwork at the Crosthwaite Parish Rooms, in Keswick, Cumbria.Bott, p ...

. The school had been opened by Edith and Hardwicke Rawnsley

Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (29 September 1851 – 28 May 1920) was an Anglican priest, poet, local politician and conservationist. He became nationally and internationally known as one of the three founders of the National Trust for Places of H ...

in 1884, amid the emergence of the Arts and Crafts movement. It offered classes in drawing, design, woodcarving, and metalwork, and melded commercial with artistic purposes; the school sold items such as trays, frames, tables, and clock-cases, and developed a reputation for quality. Already by May a reviewer for ''The Studio'' of an exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

commented that a group of silver tableware by the school was "a welcome departure towards finer craftsmanship". Two of Maryon's designs, she wrote, "were singularly good—a knocker, executed by Jeremiah Richardson, and a copper casket made by Thomas Spark and ornamented by Thomas Clark and the designer". She described the casket's lock as "enamelled in pearly blue and white", and giving "a dainty touch of colour to a form almost bare of ornament, but beautiful in its proportions and lines". At the following year's exhibition three more works by the school were singled out for praise, including a loving cup

A loving cup is a shared drinking container traditionally used at weddings and banquets. It usually has two handles and is often made of silver. Loving cups are often given as trophies to winners of games or competitions. Background

Loving cups ...

by Maryon.

Under Maryon's leadership the Keswick School expanded the breadth and range of its designs, and he executed several significant commissions. His best works, wrote a historian of the school, "drew their inspiration from the nature of the material and his deep understanding of its technical limits". They also tended to be in metal. Items like ''Bryony'', a tray centre showing tangled growth concealed within a geometric framework, continued the school's tradition of repoussé work of naturalistic interpretations of flowers, while evoking the vine-like wallpapers of William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

. These themes were particularly expressed in a 1901 plaque memorialising Bernard Gilpin

Bernard Gilpin (1517 – 4 March 1583), was an Oxford theologian and then an influential clergyman in the emerging Church of England spanning the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Jane, Mary and Elizabeth I. He was known as the 'Apostle of the N ...

, unveiled in St Cuthbert's Church, Kentmere

Kentmere is a valley, village and civil parish in the Lake District National Park, a few miles from Kendal in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England. Historically in Westmorland, at the 2011 census Kentmere had a population of 159.

...

; described by the art historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

as "Arts and Crafts, almost Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (; ) is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. The style is known by different names in different languages: in German, in Italian, in Catalan, and also known as the Modern ...

", the bronze tablet on oak is framed by trees with entwined roots and influenced by a Norse and Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

aesthetic. Three other commissions in silver—a loving cup, a processional cross, and a challenge shield—were completed towards the end of Maryon's tenure and the school and featured in ''The Studio'' and its international counterpart. The cup was commissioned by the Cumberland County Council for presentation to , and was termed a "tour de force".

Particularly in more utilitarian works, Maryon's designs at the Keswick School tended to emphasise form over design. As he would write a decade later, " er-insistence on technique, craftsmanship which proclaims 'How clever am I!' quite naturally elbows out artistic feeling. One idea must be the principal one; and if that happens to be technique, the other goes." Design should be determined by intention, he wrote: as an objet or as an object for use. Hot water jugs, tea pots, sugar bowls and other tableware that Maryon designed were frequently raised from a single sheet of metal, retaining the hammer marks and a dull lustre. Many of these were displayed at the 1902 Home Arts and Industries Exhibition, where the school won 65 awards, along with an altar cross designed by Maryon for

Particularly in more utilitarian works, Maryon's designs at the Keswick School tended to emphasise form over design. As he would write a decade later, " er-insistence on technique, craftsmanship which proclaims 'How clever am I!' quite naturally elbows out artistic feeling. One idea must be the principal one; and if that happens to be technique, the other goes." Design should be determined by intention, he wrote: as an objet or as an object for use. Hot water jugs, tea pots, sugar bowls and other tableware that Maryon designed were frequently raised from a single sheet of metal, retaining the hammer marks and a dull lustre. Many of these were displayed at the 1902 Home Arts and Industries Exhibition, where the school won 65 awards, along with an altar cross designed by Maryon for Hexham Abbey

Hexham Abbey is a Grade I listed place of Christian worship dedicated to St Andrew, in the town of Hexham, Northumberland, in the North East of England. Originally built in AD 674, the Abbey was built up during the 12th century into its curre ...

, and were praised for showing "a remarkably good year's work in the finer kinds of craft and decoration". At the same event a year later more than £35 worth of goods were sold, including a copper jug Maryon designed which was acquired by the Manchester School of Art

Manchester School of Art in Manchester, England, was established in 1838 as the Manchester School of Design. It is the second oldest art school in the United Kingdom after the Royal College of Art which was founded the year before. It is now par ...

for its Arts and Crafts Museum. On the strength of these and other achievements, Maryon's salary, which in 1902 had amounted in his estimation to between £185 and £200, was raised to £225.

Maryon's four-year tenure at Keswick was assisted by four designers who also taught drawing: G. M. Collinson, Isobel McBean, Maude M. Ackery, and Dorothea Carpenter. Hired from leading art schools and serving for a year each, the four helped the school keep abreast of modern design. Eight full-time workers helped execute the designs when Maryon joined in 1900, rising to 15 by 1903. Maryon also had the help of his sisters: Edith Maryon designed at least one work for the school, a 1901 relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

plaque of Hardwicke Rawnsley, while Mildred Maryon, who the 1901 census listed as living with her sister, worked for a time as an enameller at the school. Both Herbert and Mildred Maryon worked on an oxidised silver and enamel casket that was presented to Princess Louise upon her 1902 visit to the Keswick School; Herbert Maryon was responsible for the design and his sister for the enamelling, with the resulting work being termed "of a character highly creditable to the School" in ''The Magazine of Art

''The Magazine of Art'' was an illustrated monthly British journal devoted to the visual arts, published from May 1878 to July 1904 in London and New York City by Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. It included reviews of exhibitions, articles about art ...

''. Strife with colleagues eventually led to Maryon's departure. In July 1901 Collinson had left due to a poor working relationship, and Maryon was often in conflict with the school's management committee, which was chaired by Edith Rawnsley and frequently made decisions without his knowledge. When in August 1904 Carpenter, in friction with Maryon, resigned, the committee decided to give Maryon three-months' notice.

Maryon left the school at the end of December 1904. He spent 1905 teaching metalwork at the Storey Institute

The Storey, formerly the Storey Institute, is a multi-purpose building located at the corner of Meeting House Lane and Castle Hill in Lancaster, Lancashire, England. Its main part is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a desi ...

in Lancaster. That October he published his first article, "Early Irish Metal Work" in ''The Art Workers' Quarterly''. In 1906 Maryon, still listed as living in Keswick, again displayed works—this time a silver cup and silver chalice—for the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, held at the Grafton Galleries

The Grafton Galleries, often referred to as the Grafton Gallery, was an art gallery in Mayfair, London. The French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel showed the first major exhibition in Britain of Impressionist paintings there in 1905. Roger Fry' ...

; one Mrs. Herbert J. Maryon was listed as exhibiting a Sicilian lace tablecloth.

University of Reading, 1907–1927

From 1907 until 1927, Maryon taught sculpture, including metalwork, modelling, and casting, at the

From 1907 until 1927, Maryon taught sculpture, including metalwork, modelling, and casting, at the University of Reading

The University of Reading is a public university in Reading, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1892 as University College, Reading, a University of Oxford extension college. The institution received the power to grant its own degrees in 192 ...

. He was also the warden of Wantage Hall

Wantage Hall, built 1908, is the oldest hall of residence at the University of Reading, in Reading, England. The hall is one of 13 belonging to the University and is close to Whiteknights Campus. It is designated a grade II listed building, a stat ...

from 1920 to 1922. Maryon's first book, ''Metalwork and Enamelling: A Practical Treatise on Gold and Silversmiths' Work and their Allied Crafts'', was published in 1912. Maryon described it as eschewing "the artistic or historical point of view", in favor of an "essentially practical and technical standpoint". The book focused on individual techniques such as soldering, enamelling, and stone-setting, rather than the methods of creating works such as cups and brooches. It was well received, as a ''vade mecum

A handbook is a type of reference work, or other collection of instructions, that is intended to provide ready reference. The term originally applied to a small or portable book containing information useful for its owner, but the ''Oxford Engl ...

'' for both students and practitioners of metalworking. ''The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs'' wrote that Maryon "succeeds in every page in not only maintaining his own enthusiasm, but what is better in communicating it", and ''The Athenæum'' declared that his "critical notes on design are excellent". One such note, republished in ''The Jewelers' Circular'' in 1922, was a critique of the celebrated sixteenth-century goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini (, ; 3 November 150013 February 1571) was an Italian goldsmith, sculptor, and author. His best-known extant works include the ''Cellini Salt Cellar'', the sculpture of ''Perseus with the Head of Medusa'', and his autobiography ...

; Maryon termed him "one of the very greatest craftsmen of the sixteenth century, but... a very poor artist", a "dispassionate appraisal" that led a one-time secretary of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

to label Maryon not only "the dean of ancient metalwork", but also "a discerning critic". ''Metalwork and Enamelling'' went through four further editions, in 1923, 1954, 1959, and posthumously in 1971, along with a 1998 Italian translation, and as of 2020 is still in print by Dover Publications

Dover Publications, also known as Dover Books, is an American book publisher founded in 1941 by Hayward and Blanche Cirker. It primarily reissues books that are out of print from their original publishers. These are often, but not always, books ...

. As late as 1993, a senior conservator at the Canadian Conservation Institute

The Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI; ) is a special operating agency of the federal Department of Canadian Heritage that provides research, information, and services regarding the conservation and preservation of cultural artifacts.

Materia ...

wrote that the book "has not been equalled".

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

Maryon worked at Reading with another instructor, Charles Albert Sadler, to create a centre to train munition workers in machine tool work. Maryon began this work in 1915, officially as organising secretary and instructor at the Ministry of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis of ...

Training Centre, with no engineering school to build from. By 1918 the centre had five staff members, could accommodate 25 workers at a time, and had trained more than 400. Based on this work, Maryon was elected to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 120,000 member ...

on 6March 1918.

Maryon displayed a child's bowl with signs of the zodiac at the ninth Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition in 1910. Following the war, he—like his colleague and friend William Collingwood,—designed several memorials, including the East Knoyle War Memorial

The East Knoyle War Memorial is a monument that commemorates the lives of soldiers from East Knoyle, Wiltshire, England, who were killed in war. Unveiled on 26 September 1920, it was originally intended to commemorate the 20 soldiers from the p ...

in 1920, the Mortimer

Mortimer () is an English surname, and occasionally a given name.

Norman origins

The surname Mortimer has a Norman origin, deriving from the village of Mortemer, Seine-Maritime, Normandy. A Norman castle existed at Mortemer from an early point; ...

War Memorial in 1921, and in 1924 the University of Reading War Memorial

The University of Reading War Memorial is a clock tower, designed by Herbert Maryon and situated on the London Road Campus of the University of Reading. Initially designed as a First World War memorial and dedicated in June 1924, it was later e ...

, a clock tower on the London Road Campus

London Road Campus of the University of Reading is the original campus of that university. It is on the London Road, immediately to the south of Reading town centre in the English county of Berkshire.

The site for the campus was given to the u ...

.

Armstrong College, 1927–1939

In 1927 Maryon left the University of Reading and began teaching sculpture at Armstrong College, then part of Durham University, where he stayed until 1939. At Durham he was both master of sculpture, and lecturer in anatomy and the history of sculpture. In 1933 he published his second book, ''Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals''. Maryon wrote that his aim was to discuss modern sculpture "from the point of view of the sculptors themselves", rather than from an "archaeological or biographical" perspective. The book received mixed reviews. To '' The Art Digest'', Maryon "succeeded in trying to make sculpture intelligible to the layman". But his treatment of criticism as secondary to intent meant grouping together artworks of unequal quality. Some critics attacked his taste, with ''The New Statesman and Nation'' claiming that " can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow," ''The Bookman'' that "All the bad sculptors... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book... Most of the good sculptors are here as well (even

In 1927 Maryon left the University of Reading and began teaching sculpture at Armstrong College, then part of Durham University, where he stayed until 1939. At Durham he was both master of sculpture, and lecturer in anatomy and the history of sculpture. In 1933 he published his second book, ''Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals''. Maryon wrote that his aim was to discuss modern sculpture "from the point of view of the sculptors themselves", rather than from an "archaeological or biographical" perspective. The book received mixed reviews. To '' The Art Digest'', Maryon "succeeded in trying to make sculpture intelligible to the layman". But his treatment of criticism as secondary to intent meant grouping together artworks of unequal quality. Some critics attacked his taste, with ''The New Statesman and Nation'' claiming that " can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow," ''The Bookman'' that "All the bad sculptors... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book... Most of the good sculptors are here as well (even Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

), but all are equal in Mr. Maryon's eye," and ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'' that " e few good works which have found their way into the 356 plates look lost and unhappy." Maryon responded with explanations of his purpose, saying that "I do not admire all the results, and I say so," and to one review in particular that "I believe that the sculptors of the world have a wider knowledge of what constitutes sculpture than your reviewer realizes." Other reviews praised Maryon's academic approach. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' stated that "his book is remarkable for its extraordinary catholicity, admitting works which we should find it hard to defend... with works of great merit," yet added that " a system of grouping, however, according to some primarily aesthetic aim... their inclusion is justified." ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' praised Maryon for "a degree of natural good sense in his observations that cannot always be said to characterise current art criticism", and stated that "his critical judgments are often penetrating."

At Durham, as at Reading, Maryon was commissioned to create works of art. These included at least two plaques

Plaque may refer to:

Commemorations or awards

* Commemorative plaque, a plate or tablet fixed to a wall to mark an event, person, etc.

* Memorial Plaque (medallion), issued to next-of-kin of dead British military personnel after World War I

* Pla ...

, memorialising George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians a great example of diligent application and thirst for ...

in 1929, and Sir Charles Parsons in 1932, as well as the ''Statue of Industry'' for the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition

The North East Coast Exhibition was a world's fair held in Newcastle, Tyne and Wear and ran from May to October 1929. Held five years after the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley Park, London, and at the start of the Great Depression the event w ...

, a world's fair held at Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

. Depicting a woman with cherubs at her feet, the statue was described by Maryon as "represent ngindustry as we know it in the North-east—one who has passed through hard times and is now ready to face the future, strong and undismayed". The statue was the subject of "adverse criticism", reported ''The Manchester Guardian''; on the night of 25 October "several hundred students of Armstrong College" tarred and feathered

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture and punishment used to enforce unofficial justice or revenge. It was used in feudal Europe and its colonies in the early modern period, as well as the early American frontier, mostly as a t ...

the statue, and were dispersed only with the arrival of eighty police officers.

Maryon expressed an interest in archaeology while at Armstrong. By the early 1930s he was conducting

Maryon expressed an interest in archaeology while at Armstrong. By the early 1930s he was conducting excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

, and frequently brought students to dig along Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall ( la, Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts' Wall, or ''Vallum Hadriani'' in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. R ...

. In 1935 he published two articles on Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

swords, and at the end of the year excavated the Kirkhaugh cairns

The Kirkhaugh cairns are two, or possibly three, Bronze Age burials located in Kirkhaugh, Northumberland. The two confirmed graves were excavated in 1935 and re-excavated in 2014. The first grave, dubbed Cairn 1, contained grave goods consistent wi ...

, two Bronze Age graves at Kirkhaugh

Kirkhaugh is a very small village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Knaresdale with Kirkhaugh, adjacent to the River South Tyne in Northumberland, England. The village lies close to the A689 road north of Alston, Cumbria. In 1 ...

, Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

. One of the cairns was the nearly 4500-year-old grave of a metalworker, like the grave of the Amesbury Archer

The Amesbury Archer is an early Bronze Age (Bell Beaker) man whose grave was discovered during excavations at the site of a new housing development () in Amesbury near Stonehenge. The grave was uncovered in May 2002. The man was middle aged ...

, and contained one of the oldest gold ornaments yet found in the United Kingdom; a matching ornament was found during a re-excavation in 2014. Maryon's account of the excavation was published in 1936, and papers on archaeology and prehistoric metalworking followed. In 1937 he published an article in ''Antiquity'' clarifying a passage by the ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

on how Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

carved sculptures

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

; in 1938 he wrote in both the ''Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy

The ''Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy'' (''PRIA'') is the journal of the Royal Irish Academy, founded in 1785 to promote the study of science, polite literature, and antiquities

Antiquities are objects from antiquity, especially the ...

'' and ''The Antiquaries Journal'' on metalworking during the Bronze and Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

s; and in 1939 he wrote articles about an ancient hand-anvil

An anvil is a metalworking tool consisting of a large block of metal (usually forged or cast steel), with a flattened top surface, upon which another object is struck (or "worked").

Anvils are as massive as practical, because the higher th ...

discovered in Thomastown

Thomastown (), historically known as Grennan, is a town in County Kilkenny in the province of Leinster in the south-east of Ireland. It is a market town along a stretch of the River Nore which is known for its salmon and trout, with a number of ...

, and gold ornaments found in Alnwick

Alnwick ( ) is a market town in Northumberland, England, of which it is the traditional county town. The population at the 2011 Census was 8,116.

The town is on the south bank of the River Aln, south of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Scottish bor ...

.

Maryon retired from Armstrong College—by then known as King's College—in 1939, when he was in his mid-60s. From 1939 to 1943, at the height of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he was involved in munition

Ammunition (informally ammo) is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. Ammunition is both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines) and the component parts of other weapo ...

work. In 1941 he published a two-part article in ''Man'' on archaeology and metallurgy, part I on welding and soldering, and part II on the metallurgy of gold and platinum in Pre-Columbian Ecuador

Pre-Columbian Ecuador included numerous indigenous cultures, who thrived for thousands of years before the ascent of the Incan Empire. Las Vegas culture of coastal Ecuador is one of the oldest cultures in the Americas. The Valdivia culture in t ...

.

British Museum, 1944–1961

On 11 November 1944 Maryon was recruited out of retirement by the trustees of the British Museum to serve as a Technical Attaché. Maryon, working underHarold Plenderleith

Harold James Plenderleith MC FRSE FCS (19 September 1898 – 2 November 1997) was a 20th century Scottish art conservator and archaeologist. He was a large and jovial character with a strong Dundonian accent.

Biography

Harold Plenderleith wa ...

's leadership, was tasked with the conservation and reconstruction of material from the Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a ...

ship-burial. Widely identified with King Rædwald of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, the burial had previously attracted Maryon's interest; as early as 1941, he wrote a prescient letter about the preservation of the ship impression to Thomas Downing Kendrick, the museum's Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities. Nearly four years after his letter, in the dying days of World War II and the finds removed (or about to be removed) from safekeeping in the tunnel connecting the Aldwych

Aldwych (pronounced ) is a street and the name of the List of areas of London, area immediately surrounding it in central London, England, within the City of Westminster. The street starts Points of the compass, east-northeast of Charing Cros ...

and Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part ( St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London.

The area has its roots ...

tube stations, he was assigned what Rupert Bruce-Mitford

Rupert Leo Scott Bruce-Mitford, FBA, FSA (14 June 1914 – 10 March 1994) was a British archaeologist and scholar, best known for his multi-volume publication on the Sutton Hoo ship burial. He was a noted academic as the Slade Professor of F ...

, who succeeded Kendrick's post in 1954, termed "the real headaches—notably the crushed shield, helmet and drinking horns". Composed in large part of iron, wood and horn, these items had decayed in the 1,300 years since their burial and left only fragments behind; the helmet, for one, had corroded and then smashed into more than 500 pieces. Painstaking work needing keen observation and patience, these efforts occupied several years of Maryon's career. Much of his work has seen revision, but as Bruce-Mitford wrote afterwards, "by carrying out the initial cleaning, sorting, and mounting of the mass of the fragmentary and fragile material he preserved it, and in working out his reconstructions he made explicit the problems posed and laid the foundations upon which fresh appraisals and progress could be based when fuller archaeological study became possible."

Maryon's restorations were aided by his deep practical understandings of the objects he was working on, causing a senior conservator at the Canadian Conservation Institute in 1993 to label Maryon " e of the finest exemplars" of a conservator whose "wide understanding of the structure and function of museum objects... exceeds that gained by the curator or historian in more classical studies of artefacts." Maryon was admitted as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1949, and in 1956 his Sutton Hoo work led to his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

. Asked by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

what he did as she awarded him the medal, Maryon responded "Well, Ma'am, I am a sort of back room boy at the British Museum." Maryon continued restoration work at the British Museum, including on Orient

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of ''Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the c ...

al antiquities and the Roman Emesa helmet, before retiring—for a second time—at the age of 87.

Sutton Hoo helmet

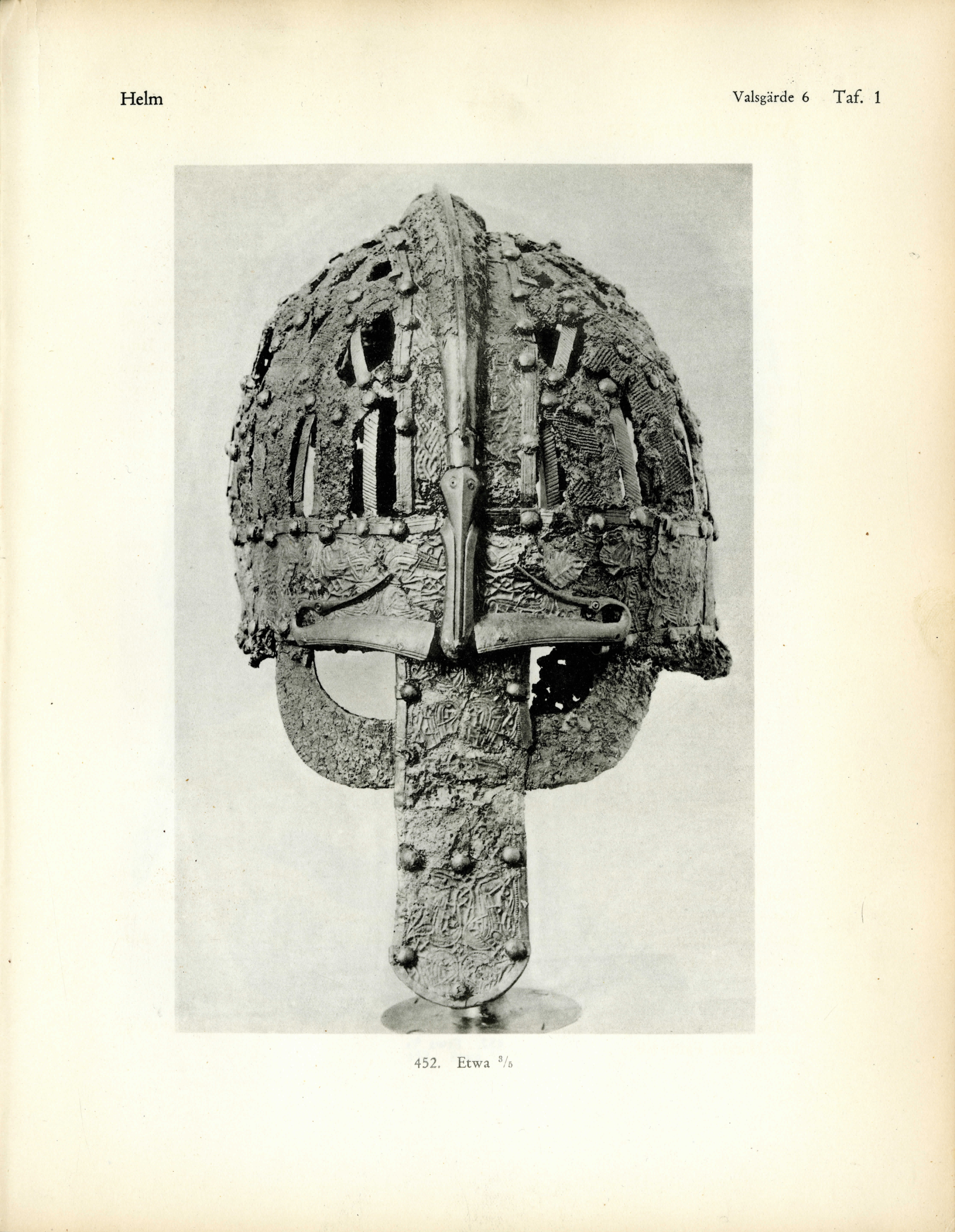

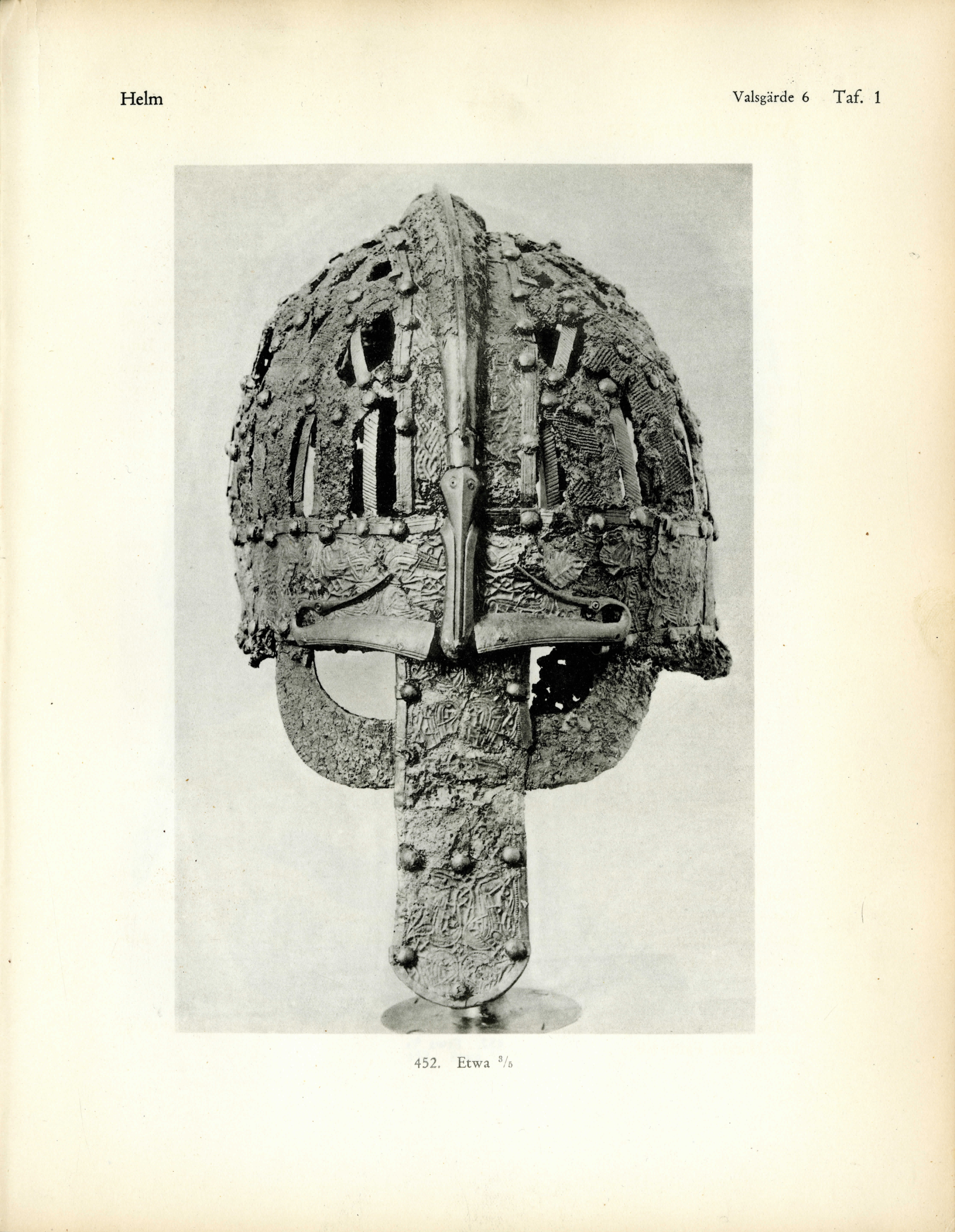

From 1945 to 1946, Maryon spent six continuous months reconstructing the

From 1945 to 1946, Maryon spent six continuous months reconstructing the Sutton Hoo helmet

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a decorated Anglo-Saxon helmet found during a 1939 excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. It was buried around 625 and is widely associated with King Rædwald of East Anglia; its elaborate decoration may have giv ...

. The helmet was only the second Anglo-Saxon example then known, the Benty Grange helmet

The Benty Grange helmet is an Anglo-Saxon boar-crested helmet from the 7th century AD. It was excavated by Thomas Bateman in 1848 from a tumulus at the Benty Grange farm in Monyash in western Derbyshire. The grave had probably been looted b ...

being the first, and was the most elaborate. Yet its importance had not been realized during excavation, and no photographs of it were taken ''in situ''. Bruce-Mitford likened Maryon's task to "a jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box", and, "as it proved, a great many of the pieces missing"; Maryon had to base his reconstruction "exclusively on the information provided by the surviving fragments, guided by archaeological knowledge of other helmets".

Maryon began the reconstruction by familiarising himself with the fragments, tracing and detailing each on a piece of card. After what he termed "a long while", he sculpted a head out of plaster and expanded it outwards to simulate the padded space between helmet and head. On this he initially affixed the fragments with plasticine

Plasticine is a putty-like modelling material made from calcium salts, petroleum jelly and aliphatic acids. Though originally a brand name for the British version of the product, it is now applied generically in English as a product categor ...

, placing thicker pieces into spaces cut into the head. Finally, the fragments were permanently affixed with white plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for Molding (decorative), moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of ...

mixed with brown umber

Umber is a natural brown earth pigment that contains iron oxide and manganese oxide. In its natural form, it is called raw umber. When Calcination, calcined, the color becomes warmer and it becomes known as burnt umber.

Its name derives from '' ...

; more plaster was used to fill the in-between areas. The fragments of the cheek guards, neck guard, and visor were placed onto shaped, plaster-covered wire mesh, then affixed with more plaster and joined to the cap. Maryon published the finished reconstruction in a 1947 issue of ''Antiquity''.

Maryon's work was celebrated, and both academically and culturally influential. The helmet stayed on display for over twenty years, with photographs making their way into television programmes, newspapers, and "every book on Anglo-Saxon art

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norma ...

and archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

"; in 1951 a young Larry Burrows

Henry Frank Leslie Burrows (29 May 1926 – 10 February 1971), known as Larry Burrows, was an English photojournalist. He spent 9 years covering the Vietnam War.

Early career

Burrows began his career in the art department of the Daily Express ...

was dispatched to the British Museum by ''Life'', which published a full page photograph of the helmet alongside a photo of Maryon. Over the succeeding quarter century conservation techniques advanced, knowledge of contemporaneous helmets grew, and more helmet fragments were discovered during the 1965–69 re-excavation of Sutton Hoo; accordingly, inaccuracies in Maryon's reconstruction—notably its diminished size, gaps in afforded protection, and lack of a moveable neck guard—became apparent. In 1971 a second reconstruction was completed, following eighteen months' work by Nigel Williams. Yet " ch of Maryon's work is valid," Bruce-Mitford wrote. "The general character of the helmet was made plain." "It was only because there was a first restoration that could be constructively criticized," noted the conservation scholar Chris Caple

Chris Caple, Society of Antiquaries of London, FSA, International Institute for Conservation#Membership, FIIC, is a senior lecturer at Durham University, who specialises in the conservation of artefacts. Involved in archaeological excavations from ...

, "that there was the impetus and improved ideas available for a second restoration;" similarly, minor errors in the second reconstruction were discovered while forging the 1973 Royal Armouries

The Royal Armouries is the United Kingdom's national collection of arms and armour. Originally an important part of England's military organization, it became the United Kingdom's oldest museum, originally housed in the Tower of London from ...

replica. In executing a first reconstruction that was reversible and retained evidence by being only lightly cleaned, Maryon's true contribution to the Sutton Hoo helmet was in creating a credible first rendering that allowed for the critical examination leading to the second, current, reconstruction.

After Sutton Hoo

Maryon finished reconstructions of significant objects from Sutton Hoo by 1946, although work on the remaining finds carried him to 1950; at this point Plenderleith decided the work had been finished to the extent possible, and that the space in the research laboratory was needed for other purposes. Maryon continued working at the museum until 1961, turning his attention to other matters. This included some travel: in April 1954 he visitedToronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, giving lectures at the Royal Ontario Museum

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) is a museum of art, world culture and natural history in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is one of the largest museums in North America and the largest in Canada. It attracts more than one million visitors every year ...

on Sutton Hoo before a large audience, and another on "Founders and Metal Workers of the Early World"; the same year he visited Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, where he was scheduled to appear on an episode of '' What in the World?'' before the artefacts were mistakenly carted away to the dump; and in 1957 or 1958, paid a visit to the Gennadeion at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

, native_name_lang = Greek

, image = American School of Classical Studies at Athens.jpg

, image_size =

, image_alt =

, caption = The ASCSA main building as seen from Mount Lykavittos

, latin_name =

, other_name =

, former_name =

, mo ...

.

In 1955 Maryon restored the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

Emesa helmet for the British Museum. It had been found in the Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

n city Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

in 1936, and underwent several failed restoration attempts before it was brought to the museum—"the last resort in these things", according to Maryon. The restoration was published the following year by Plenderleith. Around that time Maryon and Plenderleith also collaborated on several other works: in 1954 they wrote a chapter on metalwork for the ''History of Technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques and is one of the categories of world history. Technology can refer to methods ranging from as simple as stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and info ...

'' series, and in 1959 they co-authored a paper on the cleaning of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

's bronze royal effigies

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

.

Publications

In addition to ''Metalwork and Enamelling'' and ''Modern Sculpture'', Maryon authored chapters in volumes one and two ofCharles Singer

Charles Joseph Singer (2 November 1876 – 10 June 1960) was a British History of science, historian of science, technology, and medicine. He served as Royal Army Medical Corps, medical officer in the British Army.

Biography

Early years

Singe ...

's "A History of Technology" series, and wrote thirty or forty archaeological and technical papers. Several of Maryon's earlier papers, in 1946 and 1947, described his restorations of the shield and helmet from the Sutton Hoo burial. In 1948 another paper introduced the term ''pattern welding

Pattern welding is the practice in sword and knife making of forming a blade of several metal pieces of differing composition that are forge welding, forge-welded together and twisted and manipulated to form a pattern. Often mistakenly called Dam ...

'' to describe a method of strengthening and decorating iron and steel by welding into them twisted strips of metal; the method was employed on the Sutton Hoo sword among others, giving them a distinctive pattern.

During 1953 and 1954, his talk and paper on the Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes ( grc, ὁ Κολοσσὸς Ῥόδιος, ho Kolossòs Rhódios gr, Κολοσσός της Ρόδου, Kolossós tes Rhódou) was a statue of the Greek sun-god Helios, erected in the city of Rhodes (city), Rhodes, on ...

received international attention for suggesting the statue was hollow, and stood aside rather than astride the harbour. Made of hammered bronze plates less than a sixteenth of an inch thick, he suggested, it would have been supported by a tripod

A tripod is a portable three-legged frame or stand, used as a platform for supporting the weight and maintaining the stability of some other object. The three-legged (triangular stance) design provides good stability against gravitational loads ...

structure comprising the two legs and a hanging piece of drapery. Although "great ideas" according to the scholar Godefroid de Callataÿ, neither fully caught on; in 1957, Denys Haynes, then the Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum, suggested that Maryon's theory of hammered bronze plates relied on an errant translation of a primary source. Maryon's view was nevertheless influential, likely shaping Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarr ...

's 1954 surrealist imagining of the statue, ''The Colossus of Rhodes''. "Not only the pose," wrote de Callataÿ, "but even the hammered plates of Maryon's theory find n Dalí's paintinga clear and very powerful expression."

Later years

Maryon finally left the British Museum in 1961, a year after his official retirement. He donated a number of items to the museum, including plaster maquettes by George Frampton of Comedy and Tragedy, used for the memorial to Sir

Maryon finally left the British Museum in 1961, a year after his official retirement. He donated a number of items to the museum, including plaster maquettes by George Frampton of Comedy and Tragedy, used for the memorial to Sir W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most f ...

along the Victoria Embankment

Victoria Embankment is part of the Thames Embankment, a road and river-walk along the north bank of the River Thames in London. It runs from the Palace of Westminster to Blackfriars Bridge in the City of London, and acts as a major thoroughfare ...

. Before his departure Maryon had been planning a trip around the world, and at the end of 1961 he left for Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australian vernacular diminutive for ...

, Australia, arriving on 1 January 1962. In Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

he visited his brother George Maryon, whom he had not seen in 60 years. From Australia Maryon departed for San Francisco, arriving on 15 February. Much of his North American tour was done with buses and cheap hotels, for, as a colleague would recall, Maryon "liked to travel the hard way—like an undergraduate—which was to be expected since, at 89, he was a young man."

Maryon devoted much of his time during the American stage of his trip to visiting museums and the study of Chinese magic mirror

The Chinese magic mirror () traces back to at least the 5th century, although their existence during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 24 AD) has been claimed. The mirrors were made out of solid bronze. The front was polished and could be used as a mi ...

s, a subject he had turned to some two years before. By the time he reached Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the central ...

, where he was written up in ''The Kansas City Times'', he had listed 526 examples in his notebook. His trip included guest lectures, such as his talk "Metal Working in the Ancient World" at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

on 2May 1962, and when he came to New York City a colleague later said that "he wore out several much younger colleagues with an unusually long stint devoted to a meticulous examination of two large collections of pre-Columbian fine metalwork, a field that was new to him." Maryon scheduled the trip to end in Toronto, where his son John Maryon, a civil engineer, lived.

Personal life

In July 1903 Maryon married Annie Elizabeth Maryon (née Stones). They had a daughter, Kathleen Rotha Maryon. Annie Maryon died on 8February 1908. A second marriage, to Muriel Dore Wood in September 1920, produced two children, son John and daughter Margaret. Maryon lived the majority of his life in London, and died on 14 July 1965, at a nursing home in Edinburgh, in his 92nd year. Death notices were published in ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'', ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', the ''Brandon Sun

''The Brandon Sun'' is a Monday through Saturday newspaper printed in Brandon, Manitoba. It is the primary newspaper of record for western Manitoba and includes substantial political, crime, business and sports news. ''The Brandon Sun'' also pub ...

'', and the ''Ottawa Journal

The ''Ottawa Journal'' was a daily broadsheet newspaper published in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, from 1885 to 1980.

It was founded in 1885 by A. Woodburn as the ''Ottawa Evening Journal''. Its first editor was John Wesley Dafoe who came from the ...

''. Longer obituaries followed in ''Studies in Conservation'', and the ''American Journal of Archaeology

The ''American Journal of Archaeology'' (AJA), the peer-reviewed journal of the Archaeological Institute of America, has been published since 1897 (continuing the ''American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts'' founded by t ...

'',

Works by Maryon

Books

* * * * * * * * *Articles

* * ** Republication of passages from * ** Republication of * * * * * * ** Abstract published as * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Other

* * * *Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** Includes prefatory essays ''My Japanese Background'' and ''Forty Years with Sutton Hoo'' by Bruce-Mitford. The latter was republished in . * * * * * * * * ** Identical bio listed in * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Colossus articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Maryon, Herbert 1874 births 1965 deaths British metalsmiths British sculptors British male sculptors Conservator-restorers Employees of the British Museum English goldsmiths English silversmiths Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of London Officers of the Order of the British Empire Sutton Hoo