A head of state (or chief of state) is the public

persona

A persona (plural personae or personas), depending on the context, is the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional Character (arts), character. The word derives from Latin, where it originally ref ...

who officially embodies a

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

[ Foakes, pp. 110–11 "]he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and legitimacy. Depending on the country's form of

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

and

separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

, the head of state may be a ceremonial

figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a person who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet ''de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that they ...

or concurrently the

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

and more (such as the

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, who is also

commander-in-chief of the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

).

In a

parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

, such as the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

or

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the head of state usually has mostly ceremonial powers, with a separate head of government. However, in some parliamentary systems, like

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, there is an executive president that is both head of state and head of government. Likewise, in some parliamentary systems the head of state is not the head of government, but still has significant powers, for example

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

. In contrast, a

semi-presidential system

A semi-presidential republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a ...

, such as

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, has both heads of state and government as the ''de facto'' leaders of the nation (in practice they divide the leadership of the nation between themselves). Meanwhile, in

presidential systems

A presidential system, or single executive system, is a form of government in which a head of government, typically with the title of president, leads an executive branch that is separate from the legislative branch in systems that use separation ...

, the head of state is also the head of government.

In

one-party

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

ruling

communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

s, the position of president has no tangible powers by itself, however, since such a head of state, as a matter of custom, simultaneously holds the post of

General Secretary of the Communist Party General Secretary or First Secretary is the official title of leaders of most communist parties. When a communist party is the ruling party in a Communist-led one-party state, the General Secretary is typically the country's ''de facto'' leader—th ...

, they are the executive leader with their powers deriving from their status of being the

party leader

In a governmental system, a party leader acts as the official representative of their political party, either to a legislature or to the electorate. Depending on the country, the individual colloquially referred to as the "leader" of a political ...

, rather than the office of president.

Former French president

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, while developing the current

Constitution of France

The current Constitution of France was adopted on 4 October 1958. It is typically called the Constitution of the Fifth Republic , and it replaced the Constitution of the Fourth Republic of 1946 with the exception of the preamble per a Constitu ...

(1958), said that the head of state should embody ' ("the spirit of the nation").

Constitutional models

Some academic writers discuss

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

s and

governments

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

in terms of "models".

An independent

nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

normally has a head of state, and determines the extent of its head's executive powers of government or formal representational functions.

Watts

Watts is plural for ''watt'', the unit of power.

Watts may also refer to:

People

*Watts (surname), list of people with the surname Watts Fictional characters

*Watts, main character in the film '' Some Kind of Wonderful''

*Watts family, six chara ...

. In terms of

protocol

Protocol may refer to:

Sociology and politics

* Protocol (politics), a formal agreement between nation states

* Protocol (diplomacy), the etiquette of diplomacy and affairs of state

* Etiquette, a code of personal behavior

Science and technology

...

: the head of a

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

, independent state is usually identified as the person who, according to that state's constitution, is the reigning

monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

, in the case of a

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

; or the president, in the case of a

republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

.

Among the state

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

s (fundamental laws) that establish different political systems, four major types of heads of state can be distinguished:

# The

parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

, with two subset models;

## The ''standard model'', in which the head of state, in theory, possesses key executive powers, but such power is exercised on the binding advice of a

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

(e.g.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

).

## The ''non-executive model'', in which the head of state has either none or very limited executive powers, and mainly has a ceremonial and symbolic role (e.g.

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

,

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

,

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

).

# The

semi-presidential system

A semi-presidential republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a ...

, in which the head of state shares key executive powers with a head of government or cabinet (e.g.

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

); and

# The

presidential system

A presidential system, or single executive system, is a form of government in which a head of government, typically with the title of president, leads an executive branch that is separate from the legislative branch in systems that use separati ...

, in which the head of state is also the head of government and has all executive powers (e.g.

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

,

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

,

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

).

In a federal constituent or a dependent territory, the same role is fulfilled by the holder of an office corresponding to that of a head of state. For example, in each

Canadian province

Within the geographical areas of Canada, the ten provinces and three territories are sub-national administrative divisions under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Constitution. In the 1867 Canadian Confederation, three provinces of British North ...

the role is fulfilled by the

lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, whereas in most

British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remna ...

the powers and duties are performed by the

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. The same applies to

Australian states

The states and territories are federated administrative divisions in Australia, ruled by regional governments that constitute the second level of governance between the federal government and local governments. States are self-governing pol ...

,

Indian states

India is a federal union comprising 28 states and 8 union territories, with a total of 36 entities. The states and union territories are further subdivided into districts and smaller administrative divisions.

History

Pre-indepen ...

, etc.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

's constitutional document, the

Basic Law, for example, specifies the

chief executive

A chief executive officer (CEO), also known as a central executive officer (CEO), chief administrator officer (CAO) or just chief executive (CE), is one of a number of corporate executives charged with the management of an organization especially ...

as the head of the special administrative region, in addition to their role as the head of government. These non-sovereign-state heads, nevertheless, have limited or no role in diplomatic affairs, depending on the status and the norms and practices of the territories concerned.

Parliamentary system

Standard model

In

parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

s the head of state may be merely the nominal

chief executive officer

A chief executive officer (CEO), also known as a central executive officer (CEO), chief administrator officer (CAO) or just chief executive (CE), is one of a number of corporate executives charged with the management of an organization especially ...

, heading the

executive branch

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a State (polity), state.

In poli ...

of the state, and possessing limited executive power. In reality, however, following a process of constitutional evolution, powers are usually only exercised by direction of a

cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, presided over by a

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

who is answerable to the legislature. This accountability and legitimacy requires that someone be chosen who has a majority support in the

legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its p ...

(or, at least, not a majority opposition – a subtle but important difference). It also gives the legislature the right to vote down the head of

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

and their cabinet, forcing it either to resign or seek a parliamentary dissolution. The

executive branch is thus said to be responsible (or answerable) to the legislature, with the head of government and cabinet in turn accepting constitutional responsibility for offering constitutional

advice

Advice (noun) or advise (verb) may refer to:

* Advice (opinion), an opinion or recommendation offered as a guide to action, conduct

* Advice (constitutional law) a frequently binding instruction issued to a constitutional office-holder

* Advice (p ...

to the head of state.

In parliamentary

constitutional monarchies

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, the legitimacy of the unelected head of state typically derives from the tacit approval of the people via the elected representatives. Accordingly, at the time of the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

, the

English parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

acted of its own authority to name a new king and queen (the joint monarchs

Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife ...

and

William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

); likewise,

Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

's abdication required the approval of each of the six independent realms of which he was monarch. In monarchies with a written constitution, the position of monarch is a creature of the constitution and could quite properly be abolished through a democratic procedure of constitutional amendment, although there are often significant procedural hurdles imposed on such a procedure (as in the

Constitution of Spain

The Spanish Constitution (Spanish, Asturleonese, and gl, Constitución Española; eu, Espainiako Konstituzioa; ca, Constitució Espanyola; oc, Constitucion espanhòla) is the democratic law that is supreme in the Kingdom of Spain. It was e ...

).

In republics with a parliamentary system (such as India, Germany, Austria, Italy and Israel), the head of state is usually titled ''

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

'' and the principal functions of such presidents are mainly ceremonial and symbolic, as opposed to the presidents in a presidential or semi-presidential system.

In reality, numerous variants exist to the position of a head of state within a parliamentary system. The older the constitution, the more constitutional leeway tends to exist for a head of state to exercise greater powers over government, as many older parliamentary system constitutions in fact give heads of state powers and functions akin to presidential or semi-presidential systems, in some cases without containing reference to modern democratic principles of accountability to parliament or even to modern governmental offices. Usually, the king had the power of declaring war without previous consent of the parliament.

For example, under the 1848 constitution of the

Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

, and then the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, the ''

Statuto Albertino

The Statuto Albertino (English language, English: ''Albertine Statute'') was the constitution granted by King Charles Albert of Sardinia to the Kingdom of Sardinia on 4 March 1848 and written in Italian and French. The Statute later became the ...

''—the parliamentary approval to the government appointed by the king—was customary, but not required by law. So, Italy had a parliamentary system, but a "presidential" system.

Examples of heads of state in parliamentary systems using greater powers than usual, either because of ambiguous constitutions or unprecedented national emergencies, include the decision by King

Leopold III of the Belgians

Leopold III (3 November 1901 – 25 September 1983) was King of the Belgians from 23 February 1934 until his abdication on 16 July 1951. At the outbreak of World War II, Leopold tried to maintain Belgian neutrality, but after the German invas ...

to surrender on behalf of his state to the invading German army in 1940, against the will of his government. Judging that his responsibility to the nation by virtue of his coronation oath required him to act, he believed that his government's decision to fight rather than surrender was mistaken and would damage Belgium. (Leopold's decision proved highly controversial. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Belgium voted in a referendum to allow him to resume his monarchical powers and duties, but because of the ongoing controversy he ultimately abdicated.) The Belgian constitutional crisis in 1990, when the

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

refused to sign into law a bill permitting abortion, was resolved by the cabinet assuming the power to promulgate the law while he was treated as "unable to reign" for twenty-four hours.

Non-executive model

These officials are excluded completely from the executive: they do not possess even theoretical executive powers or any role, even formal, within the government. Hence their states' governments are not referred to by the traditional parliamentary model head of state

styles of ''His/Her Majesty's Government'' or ''His/Her Excellency's Government''. Within this general category, variants in terms of powers and functions may exist.

The was drawn up under the

Allied occupation that followed

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and was intended to replace the previous

militaristic

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

and quasi-

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

system with a form of liberal democracy

parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

. The constitution explicitly vests all executive power in the

Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, who is chaired by the

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

(articles 65 and 66) and responsible to the

Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

(articles 67 and 69). The

emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

is defined in the constitution as "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people" (article 1), and is generally recognised throughout the world as the Japanese head of state. Although the emperor formally

appoints the prime minister to office, article 6 of the constitution requires him to appoint the candidate "as designated by the Diet", without any right to decline appointment. He is a ceremonial

figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a person who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet ''de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that they ...

with no independent discretionary powers related to the governance of Japan.

[HEADS OF STATE, HEADS OF GOVERNMENT, MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS]

, Protocol and Liaison Service, United Nations (8 April 2016). Retrieved on 15 April 2016.[

Since the passage in ]Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

of the 1974 Instrument of Government

The Basic Laws of Sweden ( sv, Sveriges grundlagar) are the four constitutional laws of the Kingdom of Sweden that regulate the Swedish political system, acting in a similar manner to the constitutions of most countries.

These four laws are: th ...

, the Swedish monarch

The monarchy of Sweden is the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the #IOG, Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. which is a constitutional monarchy, constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parliamentary ...

no longer has many of the standard parliamentary system head of state functions that had previously belonged to him or her, as was the case in the preceding 1809 Instrument of Government. Today, the speaker of the Riksdag

The speaker of the Riksdag ( sv, Riksdagens talman) is the speaker (politics), presiding officer of the national unicameral legislature in Sweden.

The Riksdag underwent profound changes in 1867, when the medieval Riksdag of the Estates was abolis ...

appoints (following a vote in the Riksdag

The Riksdag (, ; also sv, riksdagen or ''Sveriges riksdag'' ) is the legislature and the supreme decision-making body of Sweden. Since 1971, the Riksdag has been a unicameral legislature with 349 members (), elected proportionally and se ...

) the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

and terminates their commission following a vote of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

or voluntary resignation. Cabinet members are appointed and dismissed at the sole discretion of the prime minister. Laws and ordinances are promulgated by two Cabinet members in unison signing "On Behalf of the Government" and the government—not the monarch—is the high contracting party

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

with respect to international treaties. The remaining official functions of the sovereign, by constitutional mandate or by unwritten convention, are to open the annual session of the Riksdag, receive foreign ambassadors and sign the letters of credence

A letter of credence (french: Lettre de créance) is a formal diplomatic letter that designates a diplomat as ambassador to another sovereign state. Commonly known as diplomatic credentials, the letter is addressed from one head of state to anot ...

for Swedish ambassadors, chair the foreign advisory committee, preside at the special Cabinet council when a new prime minister takes office, and to be kept informed by the prime minister on matters of state.president of Ireland

The president of Ireland ( ga, Uachtarán na hÉireann) is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces.

The president holds office for seven years, and can ...

has with the Irish government is through a formal briefing session given by the taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

(head of government) to the president. However, the president has no access to documentation and all access to ministers goes through the Department of the Taoiseach

The Department of the Taoiseach ( ga, Roinn an Taoisigh) is the government department of the Taoiseach, the title in Ireland for the head of government.Article 13.1.1° and Article 28.5.1° of the Constitution of Ireland. The latter provision re ...

. The president does, however, hold limited reserve powers

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US v ...

, such as referring a bill to the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

to test its constitutionality, which are used under the president's discretion.[

The most extreme non-executive republican head of state is the ]president of Israel

The president of the State of Israel ( he, נְשִׂיא מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, Nesi Medinat Yisra'el, or he, נְשִׂיא הַמְדִינָה, Nesi HaMedina, President of the State) is the head of state of Israel. The posi ...

, which holds no reserve powers whatsoever. The least ceremonial powers held by the president are to provide a mandate to attempt to form a government, to approve the dissolution of the Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

made by the prime minister, and to pardon criminals or to commute their sentence.

Executive model

Some parliamentary republics (like South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, Botswana

Botswana (, ), officially the Republic of Botswana ( tn, Lefatshe la Botswana, label=Setswana, ), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory being the Kalahar ...

and Kiribati

Kiribati (), officially the Republic of Kiribati ( gil, ibaberikiKiribati),[Kiribati]

''The Wor ...

) have fused the roles of the head of state with the head of government (like in a presidential system), while having the sole executive officer, often called a president, being dependent on the Parliament's confidence to rule (like in a parliamentary system). While also being the leading symbol of the nation, the president in this system acts mostly as a prime minister since the incumbent must be a member of the legislature at the time of the election, answer question sessions in Parliament, avoid motions of no confidence, etc.

Semi-presidential systems

Semi-presidential systems combine features of presidential and parliamentary systems, notably (in the president-parliamentary subtype) a requirement that the government be answerable to both the president and the legislature. The

Semi-presidential systems combine features of presidential and parliamentary systems, notably (in the president-parliamentary subtype) a requirement that the government be answerable to both the president and the legislature. The constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

of the Fifth French Republic

The Fifth Republic (french: Cinquième République) is France's current republican system of government. It was established on 4 October 1958 by Charles de Gaulle under the Constitution of the Fifth Republic.. The Fifth Republic emerged from t ...

provides for a prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

who is chosen by the president, but who nevertheless must be able to gain support in the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

. Should a president be of one side of the political spectrum and the opposition be in control of the legislature, the president is usually obliged to select someone from the opposition to become prime minister, a process known as Cohabitation

Cohabitation is an arrangement where people who are not married, usually couples, live together. They are often involved in a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increas ...

. President François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

, a Socialist, for example, was forced to cohabit with the neo-Gaullist (right wing) Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as Ma ...

, who became his prime minister from 1986 to 1988. In the French system, in the event of cohabitation, the president is often allowed to set the policy agenda in security and foreign affairs and the prime minister runs the domestic and economic agenda.

Other countries evolve into something akin to a semi-presidential system or indeed a full presidential system. Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, for example, in its constitution provided for a popularly elected president with theoretically dominant executive powers that were intended to be exercised only in emergencies, and a cabinet appointed by him from the Reichstag, which was expected, in normal circumstances, to be answerable to the Reichstag. Initially, the president was merely a symbolic figure with the Reichstag dominant; however, persistent political instability, in which governments often lasted only a few months, led to a change in the power structure of the republic, with the president's emergency powers called increasingly into use to prop up governments challenged by critical or even hostile Reichstag votes. By 1932, power had shifted to such an extent that the German president, Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

, was able to dismiss a chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

and select his own person for the job, even though the outgoing chancellor possessed the confidence of the Reichstag while the new chancellor did not. Subsequently, President von Hindenburg used his power to appoint Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

as Chancellor without consulting the Reichstag.

Presidential system

''Note: The head of state in a "presidential" system may not actually hold the title of "president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

" - the name of the system refers to any head of state who actually governs and is not directly dependent on the legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its p ...

to remain in office.''

Some constitutions or fundamental laws provide for a head of state who is not only in theory but in practice chief executive, operating separately from, and independent from, the legislature. This system is known as a "presidential system" and sometimes called the "imperial model", because the executive officials of the government are answerable solely and exclusively to a presiding, acting head of state, and is selected by and on occasion dismissed by the head of state without reference to the legislature. It is notable that some presidential systems, while not providing for collective executive accountability to the legislature, may require legislative approval for individuals prior to their assumption of cabinet office and empower the legislature to remove a president from office (for example, in the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

). In this case the debate centers on confirming them into office, not removing them from office, and does not involve the power to reject or approve proposed cabinet members ''en bloc'', so accountability does not operate in the same sense understood as a parliamentary system.

Presidential system

A presidential system, or single executive system, is a form of government in which a head of government, typically with the title of president, leads an executive branch that is separate from the legislative branch in systems that use separati ...

s are a notable feature of constitutions in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, including those of Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

, El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

; this is generally attributed to the strong influence of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in the region, and as the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

served as an inspiration and model for the Latin American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

of the early 19th century. Most presidents in such countries are selected by democratic means (popular direct or indirect election); however, like all other systems, the presidential model also encompasses people who become head of state by other means, notably through military dictatorship or ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'', as often seen in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

n, Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

ern and other presidential regimes. Some of the characteristics of a presidential system, such as a strong dominant political figure with an executive answerable to them, not the legislature can also be found among absolute monarchies

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

, parliamentary monarchies and single party

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

(e.g., Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

) regimes, but in most cases of dictatorship, their stated constitutional models are applied in name only and not in political theory or practice.

In the 1870s in the United States, in the aftermath of the impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

of President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

and his near-removal from office, it was speculated that the United States, too, would move from a presidential system to a semi-presidential or even parliamentary one, with the speaker of the House of Representatives becoming the real

Real may refer to:

Currencies

* Brazilian real (R$)

* Central American Republic real

* Mexican real

* Portuguese real

* Spanish real

* Spanish colonial real

Music Albums

* ''Real'' (L'Arc-en-Ciel album) (2000)

* ''Real'' (Bright album) (2010)

...

center of government as a quasi-prime minister. This did not happen and the presidency, having been damaged by three late nineteenth and early twentieth century assassinations (Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

, Garfield

''Garfield'' is an American comic strip created by Jim Davis. Originally published locally as ''Jon'' in 1976, then in nationwide syndication from 1978 as ''Garfield'', it chronicles the life of the title character Garfield the cat, his human ...

and McKinley) and one impeachment (Johnson), reasserted its political dominance by the early twentieth century through such figures as Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

.

Single-party states

In certain states under Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

constitutions of the constitutionally socialist state type inspired by the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR) and its constitutive Soviet republics

The Republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or the Union Republics ( rus, Сою́зные Респу́блики, r=Soyúznye Respúbliki) were national-based administrative units of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( ...

, real political power belonged to the sole legal party. In these states, there was no formal office of head of state, but rather the leader of the legislative branch was considered to be the closest common equivalent of a head of state as a natural person

In jurisprudence, a natural person (also physical person in some Commonwealth countries, or natural entity) is a person (in legal meaning, i.e., one who has its own legal personality) that is an individual human being, distinguished from the bro ...

. In the Soviet Union this position carried such titles as ''Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR''; ''Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet''; and in the case of the Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

''Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets'' (pre-1922), and ''Chairman of the Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian SFSR'' (1956–1966). This position may or may not have been held by the de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

Soviet leader at the moment. For example, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

never headed the Supreme Soviet but was First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (party leader) and Chairman of the Council of Ministers

The President of the Council of Ministers (sometimes titled Chairman of the Council of Ministers) is the most senior member of the cabinet in the executive branch of government in some countries. Some Presidents of the Council of Ministers are t ...

(head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

).

This may even lead to an institutional variability, as in North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

, where, after the presidency of party leader Kim Il-sung

Kim Il-sung (; , ; born Kim Song-ju, ; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he ruled from the country's establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994. He held the posts of ...

, the office was vacant for years. The late president was granted the posthumous title (akin to some ancient Far Eastern traditions to give posthumous names and titles to royalty) of ''" Eternal President"''. All substantive power, as party leader, itself not formally created for four years, was inherited by his son Kim Jong-il

Kim Jong-il (; ; ; born Yuri Irsenovich Kim;, 16 February 1941 – 17 December 2011) was a North Korean politician who was the second supreme leader of North Korea from 1994 to 2011. He led North Korea from the 1994 death of his father Kim ...

. The post of president was formally replaced on 5 September 1998, for ceremonial purposes, by the office of President of the Presidium of the Supreme People's Assembly

The chairman of the Standing Committee of the Supreme People's Assembly of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (), formerly known as the president of the Presidium of the Supreme People's Assembly of the Democratic People's Republic of Ko ...

, while the party leader's post as chairman of the National Defense Commission was simultaneously declared "the highest post of the state", not unlike Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. After CC ...

earlier in the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

In China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, under the current country's constitution, the Chinese President is a largely ceremonial office with limited power. However, since 1993, as a matter of convention, the presidency has been held simultaneously by the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party

The general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party () is the head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Since 1989, the CCP general secretary has been the paramount leader o ...

, the top leader in the one party system

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

. The presidency is officially regarded as an institution of the state rather than an administrative post; theoretically, the President serves at the pleasure of the National People's Congress

The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPC; ), or simply the National People's Congress, is constitutionally the supreme state authority and the national legislature of the People's Republic of China.

With 2, ...

, the legislature, and is not legally vested to take executive action on its own prerogative.

Complications with categorisation

While clear categories do exist, it is sometimes difficult to choose which category some individual heads of state belong to. In reality, the category to which each head of state belongs is assessed not by theory but by practice.

Constitutional change in

While clear categories do exist, it is sometimes difficult to choose which category some individual heads of state belong to. In reality, the category to which each head of state belongs is assessed not by theory but by practice.

Constitutional change in Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constitutional monarchy ...

in 2003 gave its head of state, the Reigning Prince, constitutional powers that included a veto over legislation and power to dismiss the head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

and cabinet.[Constitution of the Principality of Liechtenstein (LR 101)]

(2009). Retrieved on 3 August 2014. It could be argued that the strengthening of the Prince's powers, vis-a-vis the Landtag

A Landtag (State Diet) is generally the legislative assembly or parliament of a federated state or other subnational self-governing entity in German-speaking nations. It is usually a unicameral assembly exercising legislative competence in non- ...

(legislature), has moved Liechtenstein into the semi-presidential category. Similarly the original powers given to the Greek President

The president of Greece, officially the President of the Hellenic Republic ( el, Πρόεδρος της Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας, Próedros tis Ellinikís Dimokratías), commonly referred to in Greek as the President of the Rep ...

under the 1974 Hellenic Republic constitution moved Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

closer to the French semi-presidential model.

Another complication exists with South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, in which the president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

is in fact elected by the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

(legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its p ...

) and is thus similar, in principle, to a head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

in a parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

but is also, in addition, recognised as the head of state.[Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996](_blank)

, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development is the justice department of the South African government. The department provides administrative and financial support to the court system and the judiciary (which are constitutionally indep ...

(2009). Retrieved on 3 August 2014. The offices of president of Nauru

The president of Nauru is elected by Parliament from among its members, and is both the head of state and the head of government of Nauru. Nauru's unicameral Parliament has 19 members, with an electoral term of 3 years. Political parties only p ...

and president of Botswana

The president of the Republic of Botswana is the head of state and the head of government of Botswana, as well as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, according to the Constitution of Botswana.

The president is elected to a five-year t ...

are similar in this respect to the South African presidency.[Constitution of Botswana]

, Embassy of the Republic of Botswana in Washington DC. Retrieved on 11 November 2012.[THE CONSTITUTION OF NAURU]

, Parliament of Nauru

The Parliament of Nauru has 19 members, elected for a three-year term in multi-seat constituencies. The President of Nauru is elected by the members of the Parliament. . Retrieved on 11 November 2012.

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

, during the military dictatorships of Omar Torrijos

Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera (February 13, 1929 – July 31, 1981) was the Commander of the Panamanian National Guard and military leader of Panama from 1968 to his death in 1981. Torrijos was never officially the president of Panama, ...

and Manuel Noriega

Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno (; February 11, 1934 – May 29, 2017) was a Panamanian dictator, politician and military officer who was the ''de facto'' List of heads of state of Panama, ruler of Panama from 1983 to 1989. An authoritaria ...

, was nominally a presidential republic. However, the elected civilian presidents were effectively figureheads with real political power being exercised by the chief of the Panamanian Defense Forces

The Panamanian Public Forces ( es, Fuerza Pública de la República de Panamá) are the national security forces of Panama. Panama is the second country in Latin America (the other being Costa Rica) to permanently abolish standing armies, with Pa ...

.

Historically, at the time of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

(1920–1946) and the founding of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(1945), India's head of state was the monarch of the United Kingdom, ruling directly or indirectly as Emperor of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state. Royal Proclamation of 22 ...

through the Viceroy and Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

.

Roles

Head of state is the highest-ranking constitutional position in a sovereign state. A head of state has some or all of the roles listed below, often depending on the constitutional category (above), and does not necessarily regularly exercise the most power or influence of governance. There is usually a formal public ceremony when a person becomes head of state, or some time after. This may be the swearing in at the inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugu ...

of a president of a republic, or the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

of a monarch.

Symbolic role

One of the most important roles of the modern head of state is being a living national symbol

A national symbol is a symbol of any entity considering and manifesting itself to the world as a national community: the sovereign states but also nations and countries in a state of colonial or other dependence, federal integration, or even an ...

of the state; in hereditary monarchies this extends to the monarch being a symbol of the unbroken continuity of the state. For instance, the Canadian monarch

The monarchy of Canada is Canada's form of government embodied by the Canadian sovereign and head of state. It is at the core of Canada's constitutional federal structure and Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. The monarchy is the found ...

is described by the government as being the personification of the Canadian state and is described by the Department of Canadian Heritage

The Department of Canadian Heritage, or simply Canadian Heritage (french: Patrimoine canadien), is the department of the Government of Canada that has roles and responsibilities related to initiatives that promote and support "Canadian identity ...

as the "personal symbol of allegiance, unity and authority for all Canadians".portrait

A portrait is a portrait painting, painting, portrait photography, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expressions are predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, Personality type ...

s of the head of state can be found in government offices, courts of law, or other public buildings. The idea, sometimes regulated by law, is to use these portraits to make the public aware of the symbolic connection to the government, a practice that dates back to medieval times. Sometimes this practice is taken to excess, and the head of state becomes the principal symbol of the nation, resulting in the emergence of a personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

where the image of the head of state is the only visual representation of the country, surpassing other symbols such as the flag

A flag is a piece of fabric (most often rectangular or quadrilateral) with a distinctive design and colours. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design empl ...

.

Other common representations are on coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order t ...

s, postage and other stamps and banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

s, sometimes by no more than a mention or signature; and public places, streets, monuments and institutions such as schools are named for current or previous heads of state. In monarchies (e.g., Belgium) there can even be a practice to attribute the adjective "royal" on demand based on existence for a given number of years. However, such political techniques can also be used by leaders without the formal rank of head of state, even party - and other revolutionary leaders without formal state mandate.

Heads of state often greet important foreign visitors, particularly visiting heads of state. They assume a host role during a state visit

A state visit is a formal visit by a head of state to a foreign country, at the invitation of the head of state of that foreign country, with the latter also acting as the official host for the duration of the state visit. Speaking for the host ...

, and the programme may feature playing of the national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European n ...

s by a military band

A military band is a group of personnel that performs musical duties for military functions, usually for the armed forces. A typical military band consists mostly of wind and percussion instruments. The conductor of a band commonly bears the tit ...

, inspection of military troops, official exchange of gifts, and attending a state dinner

A state banquet is an official banquet hosted by the head of state in his or her official residence for another head of state, or sometimes head of government, and other guests. Usually as part of a state visit or diplomatic conference, it is ...

at the official residence

An official residence is the House, residence of a head of state, head of government, governor, Clergy, religious leader, leaders of international organizations, or other senior figure. It may be the same place where they conduct their work-relate ...

of the host.

At home, heads of state are expected to render lustre to various occasions by their presence, such as by attending artistic or sports performances or competitions (often in a theatrical honour box, on a platform, on the front row, at the honours table), expositions, national day celebrations, dedication events, military parades and war remembrances, prominent funerals, visiting different parts of the country and people from different walks of life, and at times performing symbolic acts such as cutting a ribbon, groundbreaking

Groundbreaking, also known as cutting, sod-cutting, turning the first sod, or a sod-turning ceremony, is a traditional ceremony in many cultures that celebrates the first day of construction for a building or other project. Such ceremonies are o ...

, ship christening

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

, laying the first stone. Some parts of national life receive their regular attention, often on an annual basis, or even in the form of official patronage.

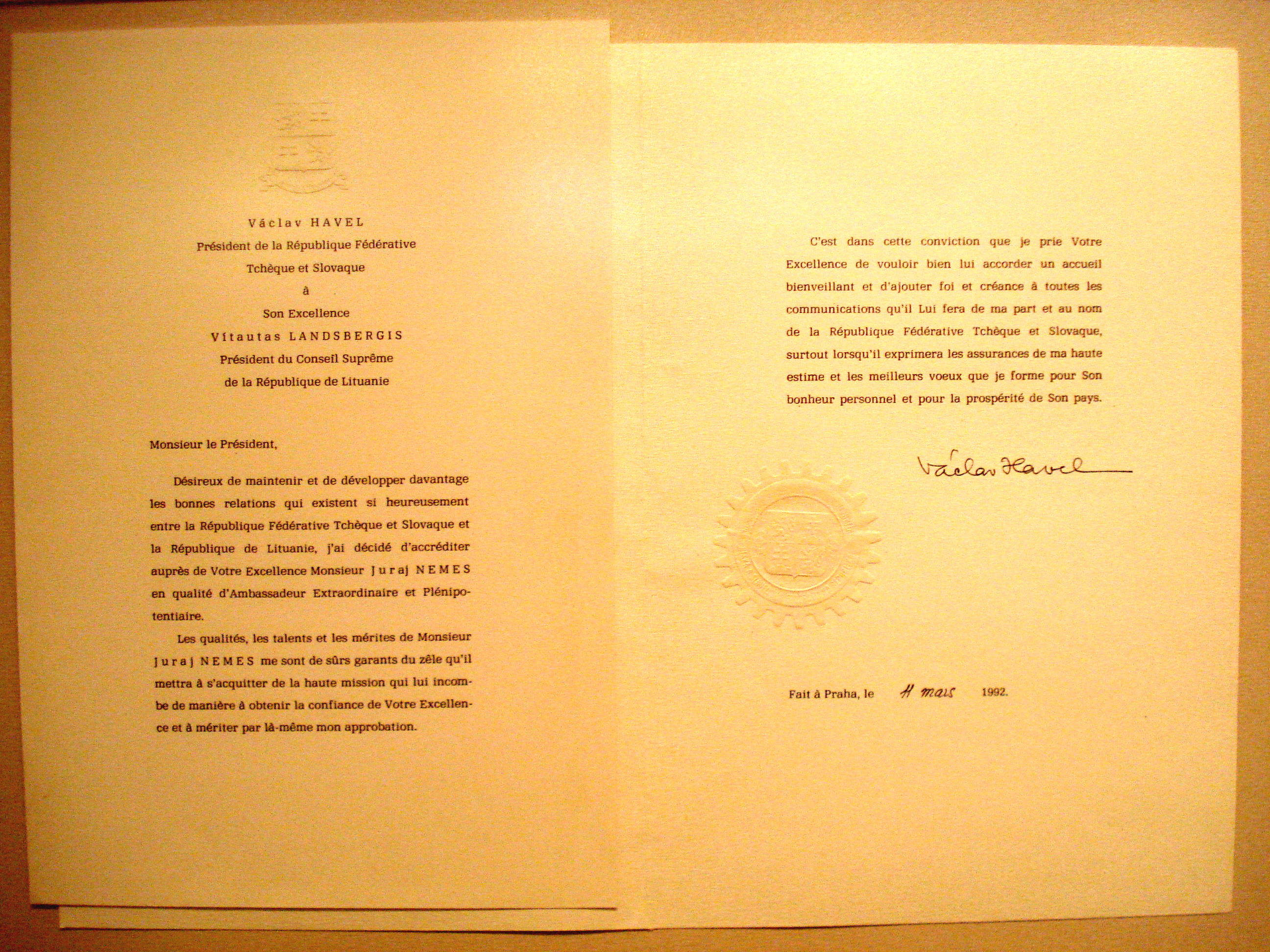

The Olympic Charter