The persecution of Christians can be

historically

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

traced from the

first century

The 1st century was the century spanning AD 1 ( I) through AD 100 ( C) according to the Julian calendar. It is often written as the or to distinguish it from the 1st century BC (or BCE) which preceded it. The 1st century is considered part of t ...

of the

Christian era

The terms (AD) and before Christ (BC) are used to label or number years in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. The term is Medieval Latin and means 'in the year of the Lord', but is often presented using "our Lord" instead of "the Lord", ...

to the

present day.

Christian missionaries

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such as ...

and

converts to Christianity have both been targeted for persecution, sometimes to the point of being

martyred for their faith, ever since the emergence of Christianity.

Early Christians

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

were persecuted at the hands of both

Jews, from

whose religion Christianity arose, and the

Romans who controlled many of the

early centers of Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

in the

Roman Empire. Since the emergence of

Christian states in

Late Antiquity, Christians have also been

persecuted by other Christians due to differences in

doctrine which have been declared

heretical.

Early in the fourth century, the empire's official persecutions were ended by the

Edict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

in 311 and the practice of Christianity legalized by the

Edict of Milan in 312. By the year 380, Christians began to persecute each other. The

schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

s of

late antiquity and the

Middle Ages – including the

Rome–Constantinople schisms and the many

Christological controversies – together with the later

Protestant Reformation provoked

severe conflicts between

Christian denominations

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

. During these conflicts, members of the various denominations frequently

persecuted each other and engaged in

sectarian violence. In the 20th century,

Christian populations were persecuted, sometimes, they were persecuted to the point of

genocide, by various states, including the

Ottoman Empire and

its successor state, which committed the

Hamidian massacres

The Hamidian massacres also called the Armenian massacres, were massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1890s. Estimated casualties ranged from 100,000 to 300,000, Akçam, Taner (2006) '' A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide an ...

, the

Armenian genocide, the

Assyrian genocide, and the

Greek genocide, and officially

atheist states

State atheism is the incorporation of positive atheism or non-theism into political regimes. It may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments. It is a form of religion-state relationship that is usually ideologically li ...

such as the former

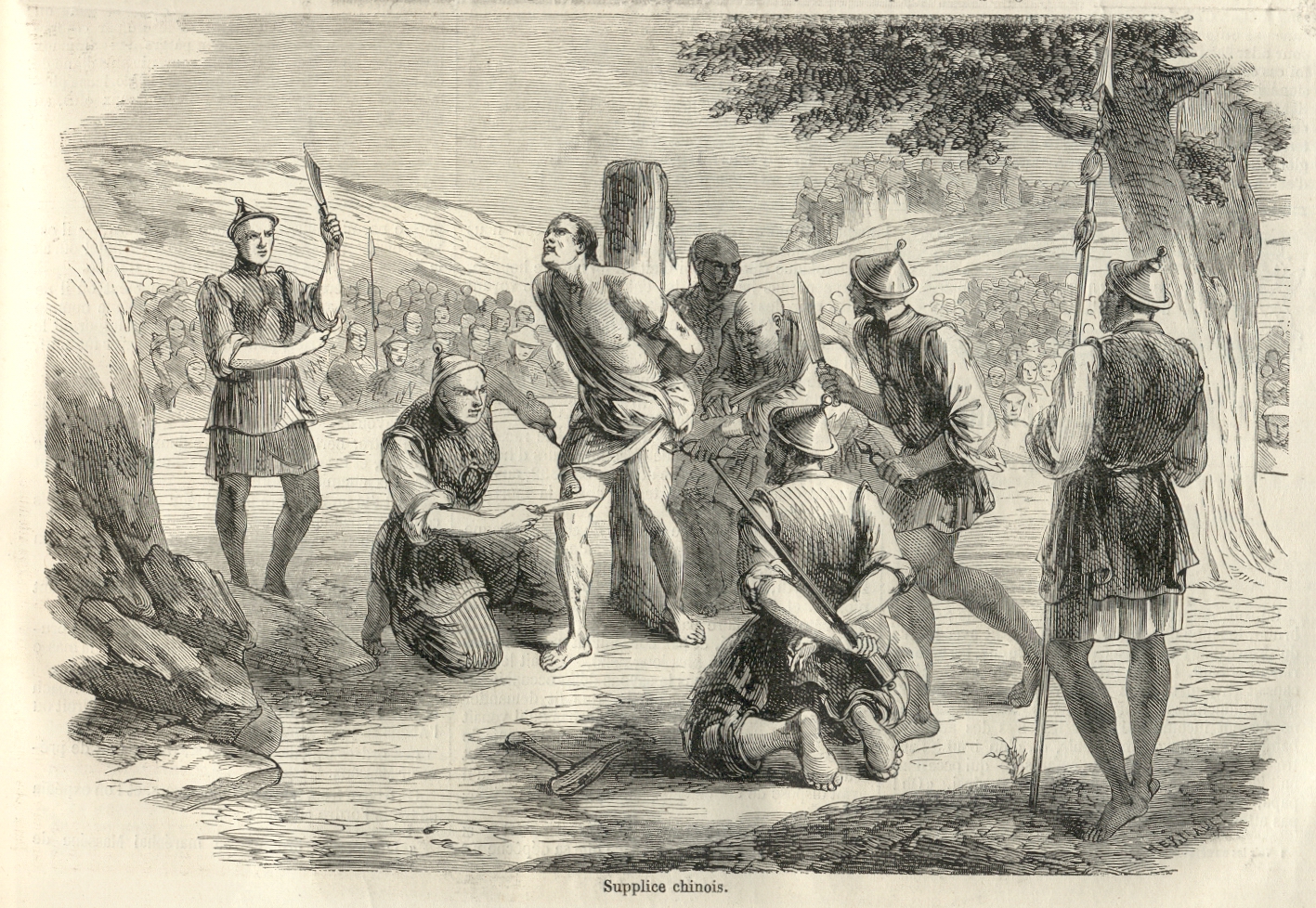

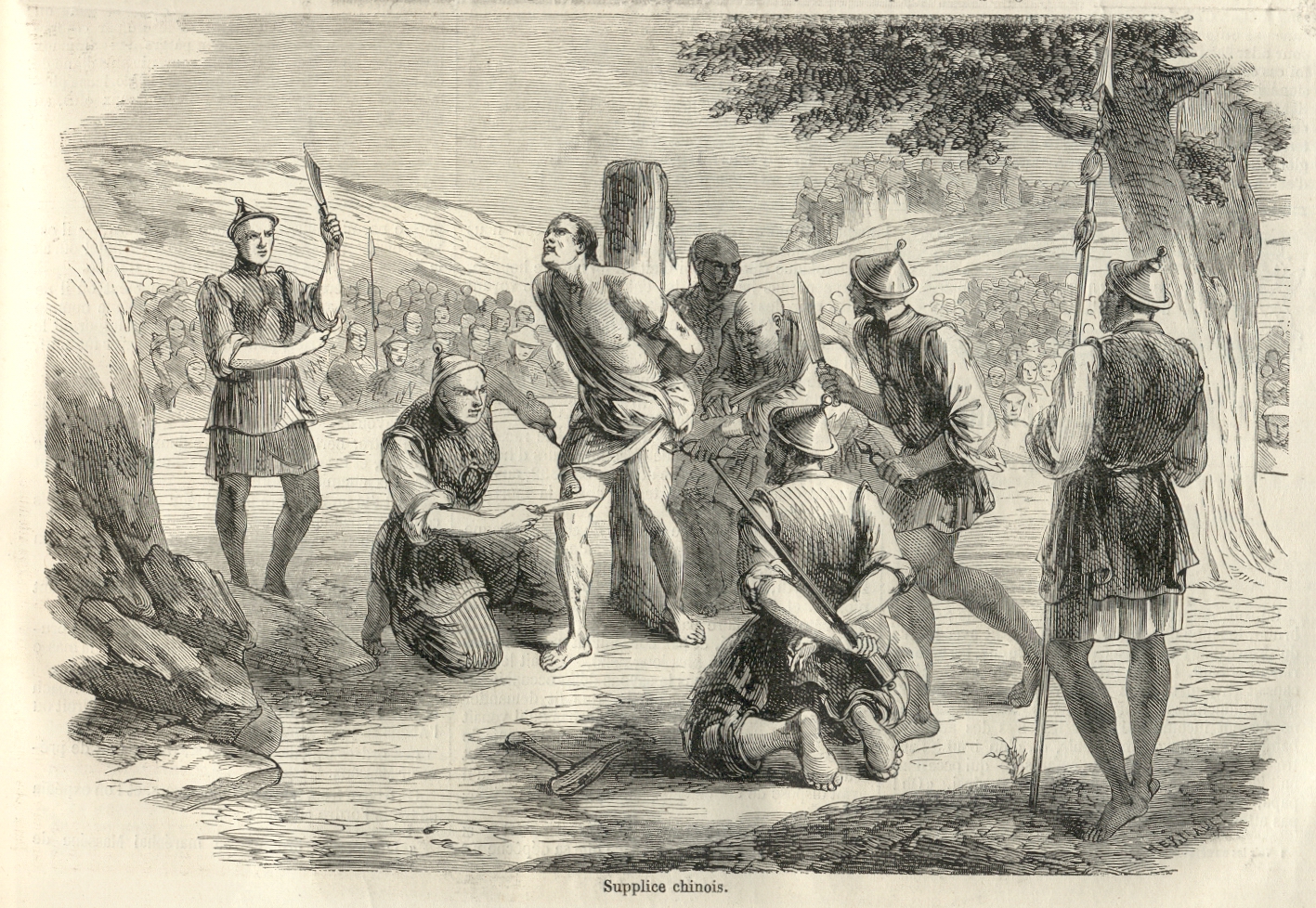

Soviet Union,

Communist Albania, China, and North Korea.

The persecution of Christians has

continued to occur during the 21st century. Christianity is the largest

world religion and its adherents live across the globe. Approximately 10% of the world's Christians are members of minority groups which live in non-Christian-majority states. The contemporary persecution of Christians includes the

genocide of Christians by the Islamic State and persecution by other terrorist groups, with official state persecution mostly occurring in countries which are located in Africa and Asia because they have

state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

s or because their governments and societies practice religious favoritism. Such favoritism is frequently accompanied by

religious discrimination and

religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within soc ...

, as is also the case in currently and formerly

communist countries.

According to the

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom's 2020 report, Christians in

Burma,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

,

Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

,

India,

Iran,

Nigeria,

North Korea,

Pakistan,

Russia,

Saudi Arabia,

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and

Vietnam are persecuted; these countries are labelled "countries of particular concern" by the

United States Department of State, because of their governments' engagement in, or toleration of, "severe violations of religious freedom".

The same report recommends that Afghanistan,

Algeria, Azerbaijan,

Bahrain, the Central African Republic,

Cuba,

Egypt,

Indonesia,

Iraq,

Kazakhstan,

Malaysia,

Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

, and

Turkey constitute the US State Department's "special watchlist" of countries in which the government allows or engages in "severe violations of

religious freedom".

Much of the persecution of Christians in recent times is perpetrated by

non-state actors which are labelled "entities of particular concern" by the US State Department, including the

Islamist groups

Boko Haram

Boko Haram, officially known as ''Jamā'at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād'' ( ar, جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد, lit=Group of the People of Sunnah for Dawah and Jihad), is an Islamic terrorist organization ...

in Nigeria, the

Houthi movement in Yemen, the

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant – Khorasan Province in Pakistan,

al-Shabaab in Somalia, the

Taliban in Afghanistan, the

Islamic State and

Tahrir al-Sham in Syria, as well as the

United Wa State Army and participants in the

Kachin conflict

The Kachin conflict or the Kachin War is one of the multiple conflicts which are collectively referred to as the internal conflict in Myanmar. Kachin insurgents have been fighting against the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) since 1961, with o ...

in Myanmar.

Antiquity

New Testament

Early Christianity began as a sect among

Second Temple Jews. Inter-communal dissension began almost immediately.

According to the

New Testament account, Saul of Tarsus prior to

his conversion to Christianity persecuted early

Judeo-Christian

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, or ...

s.

According to the ''

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its messag ...

'', a year after the Roman

Crucifixion of Jesus,

Stephen was

stoned for his transgressions of the

Jewish law

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws which is derived from the Torah, written and Oral Tora ...

.

[Burke, John J.]

Characteristics Of The Early Church

p.101, Read Country Books 2008 And

Saul (who later converted and was renamed ''Paul'') acquiesced, looking on and witnessing Steven's death. Later, Paul begins a listing of his own sufferings after conversion in 2 Corinthians 11: "Five times I received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods, once I was stoned ..."

Early Judeo-Christian

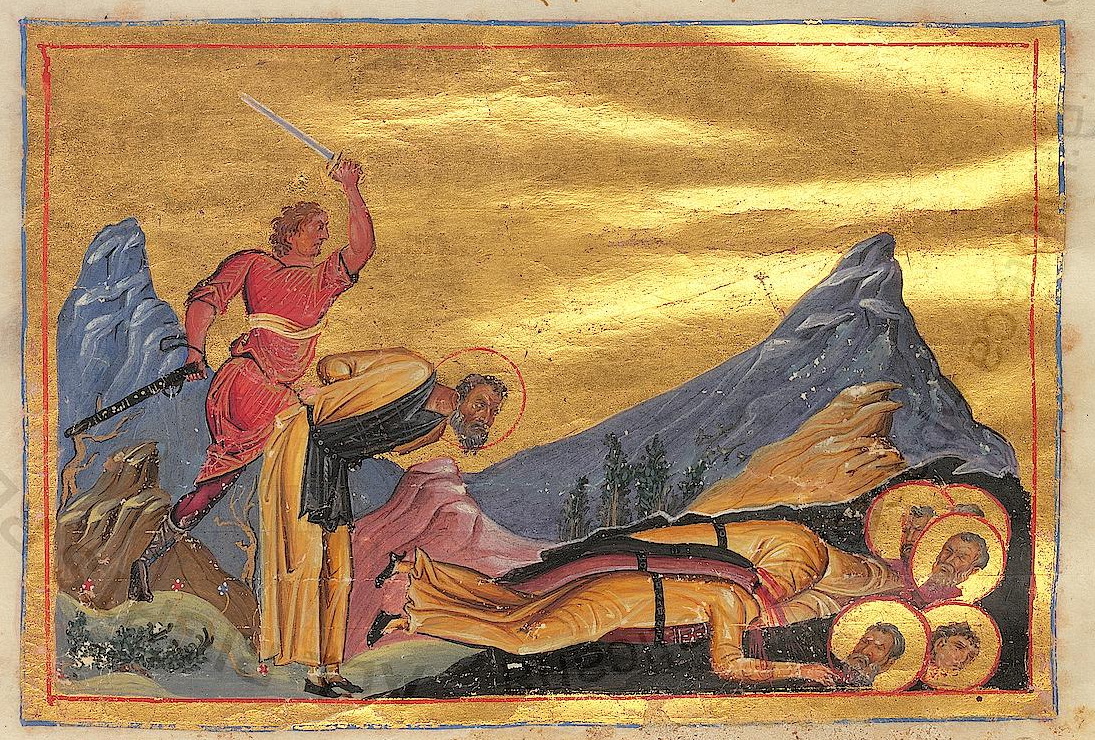

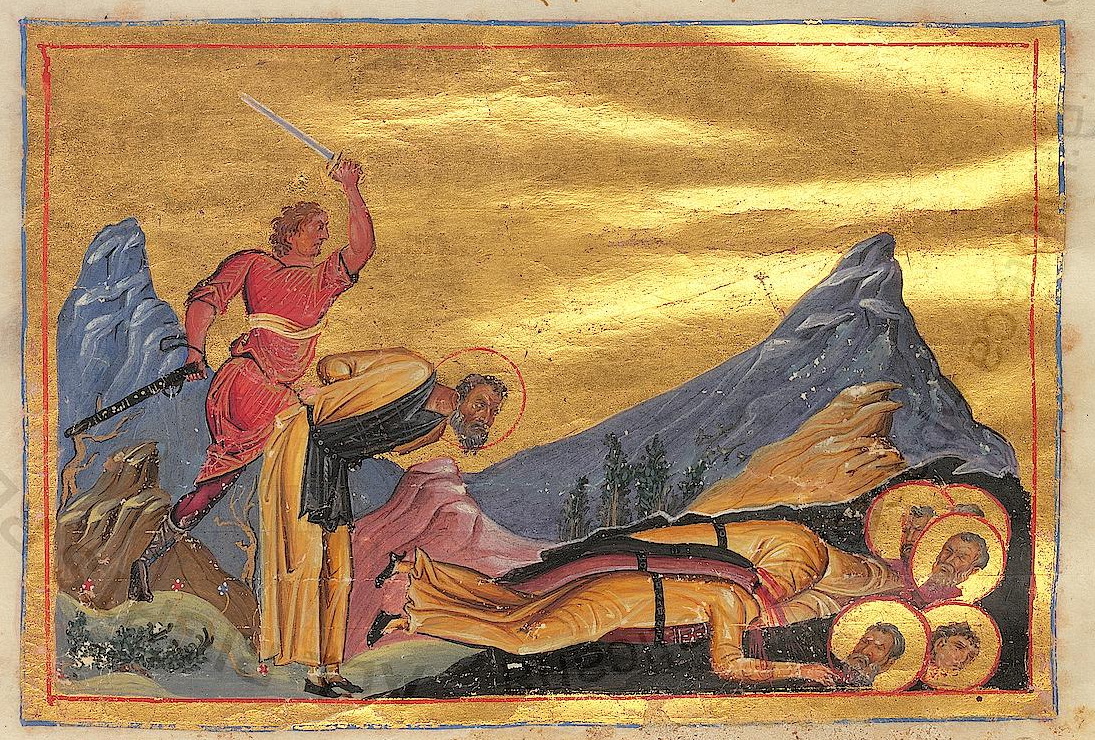

In 41 AD,

Herod Agrippa, who already possessed the territory of

Herod Antipas

Herod Antipas ( el, Ἡρῴδης Ἀντίπας, ''Hērǭdēs Antipas''; born before 20 BC – died after 39 AD), was a 1st-century ruler of Galilee and Perea, who bore the title of tetrarch ("ruler of a quarter") and is referred to as both "H ...

and

Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

(his former colleagues in the

Herodian Tetrarchy

The Herodian Tetrarchy was formed following the death of Herod the Great in 4 BCE, when his kingdom was divided between his sons Herod Archelaus as ethnarch, Herod Antipas and Philip as tetrarchs in inheritance, while Herod's sister Salome I brief ...

), obtained the title of ''King of the Jews'', and in a sense, re-formed the

Kingdom of Judea of

Herod the Great (). Herod Agrippa was reportedly eager to endear himself to his Jewish subjects and continued the persecution in which

James the Great lost his life,

Saint Peter narrowly escaped and the rest of the

apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

took flight. After Agrippa's death in 44, the Roman procuratorship began (before 41 they were

Prefects in Iudaea Province) and those leaders maintained a neutral peace, until the procurator

Porcius Festus died in 62 and the high priest

Ananus ben Ananus took advantage of the power vacuum to attack the Church and execute

James the Just

James the Just, or a variation of James, brother of the Lord ( la, Iacobus from he, יעקב, and grc-gre, Ἰάκωβος, , can also be Anglicized as "Jacob"), was "a brother of Jesus", according to the New Testament. He was an early lead ...

, then leader of

Jerusalem's Christians.

The New Testament states that Paul was himself imprisoned on several occasions by the Roman authorities, stoned by the Pharisees and left for dead on one occasion, and was eventually taken to Rome as a prisoner. Peter and other early Christians were also imprisoned, beaten and harassed. The

First Jewish Rebellion

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number 1 (number), one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, D ...

, spurred by the Roman killing of 3,000 Jews, led to the

destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, the end of

Second Temple Judaism (and the subsequent slow rise of

Rabbinic Judaism).

Claudia Setzer asserts that, "Jews did not see Christians as clearly separate from their own community until at least the middle of the second century" but most scholars place the "parting of the ways" much earlier, with theological separation occurring immediately. Second Temple Judaism had allowed more than one way to be Jewish. After the fall of the Temple, one way led to rabbinic Judaism, while another way became Christianity; but Christianity was "molded around the conviction that the Jew, Jesus of Nazareth, was not only the Messiah promised to the Jews, but God's son, offering access to God, and God's blessing to non-Jew as much as, and perhaps eventually more than, to Jews".

While Messianic eschatology had deep roots in Judaism, and the idea of the suffering servant, known as Messiah Ephraim, had been an aspect since the time of Isaiah (7th century BCE), in the first century, this idea was seen as being usurped by the Christians. It was then suppressed, and did not make its way back into rabbinic teaching till the seventh century writings of Pesiqta Rabati.

The traditional view of the separation of Judaism and Christianity has Jewish-Christians fleeing, ''en masse'', to Pella (shortly before the fall of the Temple in 70 AD) as a result of Jewish persecution and hatred.

Steven D. Katz says "there can be no doubt that the post-70 situation witnessed a change in the relations of Jews and Christians".

Judaism sought to reconstitute itself after the disaster which included determining the proper response to Jewish Christianity. The exact shape of this is not directly known but is traditionally alleged to have taken four forms: the circulation of official anti-Christian pronouncements, the issuing of an official ban against Christians attending synagogue, a prohibition against reading Christian writings, and the spreading of the curse against Christian heretics: the

Birkat haMinim.

Roman Empire

Neronian persecution

The first documented case of imperially supervised persecution of Christians in the

Roman Empire begins with

Nero (54–68). In 64 AD, a

great fire broke out in Rome, destroying portions of the city and impoverishing the Roman population. Some people suspected that Nero himself was the arsonist, as

Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

reported, claiming that he played the lyre and sang the 'Sack of

Ilium

Ilium or Ileum may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

* Ilion (Asia Minor), former name of Troy

* Ilium (Epirus), an ancient city in Epirus, Greece

* Ilium, ancient name of Cestria (Epirus), an ancient city in Epirus, Greece

* Ilium Building, a ...

' during the fires. In the ''Annals'',

Tacitus wrote:

This passage in Tacitus constitutes the only independent attestation that Nero blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome, and while it is generally believed to be authentic and reliable, some modern scholars have cast doubt on this view, largely because there is no further reference to Nero's blaming of Christians for the fire until the late 4th century.

Suetonius, later to the period, does not mention any persecution after the fire, but in a previous paragraph unrelated to the fire, mentions punishments inflicted on Christians, defined as men following a new and malefic superstition. Suetonius, however, does not specify the reasons for the punishment; he simply lists the fact together with other abuses put down by Nero.

From Nero to Decius

In the first two centuries Christianity was a relatively small sect which was not a significant concern of the Emperor.

Rodney Stark estimates there were fewer than 10,000 Christians in the year 100. Christianity grew to about 200,000 by the year 200, which works out to about .36% of the population of the empire, and then to almost 2 million by 250, still making up less than 2% of the empire's overall population. According to

Guy Laurie

Guy or GUY may refer to:

Personal names

* Guy (given name)

* Guy (surname)

* That Guy (...), the New Zealand street performer Leigh Hart

Places

* Guy, Alberta, a Canadian hamlet

* Guy, Arkansas, US, a city

* Guy, Indiana, US, an uninco ...

, the Church was not in a struggle for its existence during its first centuries.

However,

Bernard Green

Edward Bernard Green OSB (1953–22 March 2013) was an English Catholic priest, Benedictine monk of Ampleforth Abbey, and historian.

Biography

Green was educated at Oriel College, Oxford, where he received his BA in Modern History and later ...

says that, although early persecutions of Christians were generally sporadic, local, and under the direction of regional governors, not emperors, Christians "were always subject to oppression and at risk of open persecution."

James L. Papandrea

James L. Papandrea (born May 9, 1963) is an author, Catholic Church, Catholic theologian, historian, speaker, and singer/songwriter. He is currently Professor of Church History and Historical Theology at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in ...

says there are ten emperors generally accepted to have sponsored state sanctioned persecution of Christians,

though the first empire-wide government sponsored persecution was not until Decius in 249.

[

According to two different Christian traditions, ]Simon bar Kokhba

Simon ben Koseba or Cosiba ( he, שִׁמְעוֹן בַּר כֹסֵבָא, translit= Šīmʾōn bar Ḵōsēḇaʾ ; died 135 CE), commonly known as Bar Kokhba ( he, שִׁמְעוֹן בַּר כּוֹכְבָא, translit=Šīmʾōn bar ...

, the leader of the second Jewish revolt against Rome (132–136 AD), who was proclaimed Messiah, persecuted the Christians: Justin Martyr claims that Christians were punished if they did not deny and blaspheme Jesus Christ, while Eusebius asserts that Bar Kokhba harassed them because they refused to join his revolt against the Romans. The latter is likely true, and Christians' refusal to take part in the revolt against the Roman Empire was a key event in the schism of Early Christianity and Judaism.

One traditional account of killing is the persecution in Lyon

The persecution in Lyon in AD 177 was a legendary persecution of Christians in Lugdunum, Roman Gaul (present-day Lyon, France), during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180). As there is no coeval account of this persecution the earliest sourc ...

in which Christians were purportedly mass-slaughtered by being thrown to wild beasts under the decree of Roman officials for reportedly refusing to renounce their faith according to Irenaeus. The sole source for this event is early Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christia ...

's '' Church History'', an account written in Egypt in the 4th century. Tertullian's '' Apologeticus'' of 197 was ostensibly written in defense of persecuted Christians and was addressed to Roman governors.

Trajan's policy towards Christians was no different from the treatment of other sects, that is, they would only be punished if they refused to worship the emperor and the gods, but they were not to be sought out. The ''Historia Augusta

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the sim ...

'' mentions an edict of Emperor Septimius Severus against Christians; however, since the ''Historia Augusta'' is an unreliable mix of fact and fiction, historians consider the existence of such edict dubious.

According to Eusebius, the Imperial household of Maximinus Thrax's predecessor, Severus Alexander, had contained many Christians. Eusebius states that, hating his predecessor's household, Maximinus ordered that the leaders of the churches should be put to death.Pope Pontian

Pope Pontian ( la, Pontianus; died October 235) was the bishop of Rome from 21 July 230 to 28 September 235.Kirsch, Johann Peter (1911). "Pope St. Pontian" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company. In 235, duri ...

into exile but other evidence suggests that the persecutions of 235 were local to the provinces where they occurred rather than happening under the direction of the Emperor.

=Voluntary martyrdom

=

Some early Christians sought out and welcomed martyrdom. According to Droge and Tabor, "in 185 the proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus, was approached by a group of Christians demanding to be executed. The proconsul obliged some of them and then sent the rest away, saying that if they wanted to kill themselves there was plenty of rope available or cliffs they could jump off." Such enthusiasm for death is found in the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch who was arrested and condemned as a criminal before writing his letters while on the way to execution. Ignatius casts his own martyrdom as a voluntary eucharistic sacrifice to be embraced.Montanists

Montanism (), known by its adherents as the New Prophecy, was an History of Christianity#Early Christianity (c. 31/33–324), early Christian movement of the Christianity in the 2nd century, late 2nd century, later referred to by the name of it ...

and Donatists

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and th ...

), those who occupied a neutral, moderate position (the orthodox), and those who were anti-martyrdom (the Gnostics

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

).[Moss, Candida R. "The Discourse of Voluntary Martyrdom: Ancient and Modern.” Church History, vol. 81, no. 3, 2012, pp. 531–551., www.jstor.org/stable/23252340. Retrieved 23 January 2021] The condemnation of voluntary martyrdom is used to justify Clement fleeing the Severan persecution in Alexandria in 202 AD, and the ''Martyrdom of Polycarp'' justifies Polycarp's flight on the same grounds. "Voluntary martyrdom is parsed as passionate foolishness" whereas "flight from persecution is patience" and the end result a true martyrdom.G. E. M. de Ste. Croix

Geoffrey Ernest Maurice de Ste. Croix, (; 8 February 1910 – 5 February 2000), known informally as Croicks, was a British historian who specialised in examining Ancient Greece from a Marxism, Marxist perspective. He was Fellow and Tutor in Anci ...

adds a category of "quasi-voluntary martyrdom": "martyrs who were not directly responsible for their own arrest but who, after being arrested, behaved with" a stubborn refusal to obey or comply with authority.

Decian persecution

In the reign of the emperor Decius (), a decree was issued requiring that all residents of the empire should perform sacrifices, to be enforced by the issuing of each person with a ''libellus

A ''libellus'' (plural ''libelli'') in the Roman Empire was any brief document written on individual pages (as opposed to scrolls or tablets), particularly official documents issued by governmental authorities.

The term ''libellus'' has particular ...

'' certifying that they had performed the necessary ritual.Carpi

Carpi may refer to:

Places

* Carpi, Emilia-Romagna, a large town in the province of Modena, central Italy

* Carpi (Africa), a city and former diocese of Roman Africa, now a Latin Catholic titular bishopric

People

* Carpi (people), an ancie ...

and the Goths.Babylas of Antioch

Babylas ( el, Βαβύλας) (died 253) was a patriarch of Antioch (237–253), who died in prison during the Decian persecution. In the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches of the Byzantine rite his feast day is September 4, in ...

, and Fabian of Rome were all imprisoned and killed.Cyprian of Carthage

Cyprian (; la, Thaschus Caecilius Cyprianus; 210 – 14 September 258 AD''The Liturgy of the Hours according to the Roman Rite: Vol. IV.'' New York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1975. p. 1406.) was a bishop of Carthage and an early Christ ...

fled his episcopal see

An episcopal see is, in a practical use of the phrase, the area of a bishop's ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Phrases concerning actions occurring within or outside an episcopal see are indicative of the geographical significance of the term, mak ...

to the countryside.[Scarre 1995, p. 170] After Decius died, Trebonianus Gallus () succeeded him and continued the Decian persecution for the duration of his reign.

Valerianic persecution

The accession of Trebonianus Gallus's successor Valerian () ended the Decian persecution.

Late Antiquity

Roman Empire

The Great Persecution

The Great Persecution, or Diocletianic Persecution, was begun by the senior '' augustus'' and Roman emperor Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

() on 23 February 303.Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Cr ...

's ''De mortibus persecutorum'' ("on the deaths of the persecutors"), Diocletian's junior emperor, the ''caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

'' Galerius () pressured the ''augustus'' to begin persecuting Christians.Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christia ...

's '' Church History'' reports that imperial edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Proc ...

s were promulgated to destroy churches and confiscate scriptures, and to remove Christian occupants of government positions, while Christian priests were to be imprisoned and required to perform sacrifice in ancient Roman religion

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

.praetorian prefecture of Africa

The praetorian prefecture of Africa ( la, praefectura praetorio Africae) was an administrative division of the Eastern Roman Empire in the Maghreb. With its seat at Carthage, it was established after the reconquest of northwestern Africa from the ...

involving the confiscation of written materials which led to the Donatist schism

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and th ...

.Phileas of Thmuis

Saints Phileas and Philoromus (died ) were two Egyptian martyrs under the Emperor Diocletian. Phileas was Bishop of Thmuis and Philoromus was a senior imperial officer.

Monks of Ramsgate account

The monks of St Augustine's Abbey, Ramsgate wrote ...

, bishop of Thmuis in Egypt's Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Po ...

, which survive on Greek papyri

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a d ...

from the 4th century among the Bodmer Papyri

The Bodmer Papyri are a group of twenty-two papyri discovered in Egypt in 1952. They are named after Martin Bodmer, who purchased them. The papyri contain segments from the Old and New Testaments, early Christian literature, Homer, and Menander ...

and the Chester Beatty Papyri of the Bodmer and Chester Beatty

Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (7 February 1875 – 19 January 1968)Seanad 1985: "Chester Beatty died at the Princess Grace Clinic, Monte Carlo, on 19 January 1968, .. (some sources give this as 20 January). was an American-British mining magnate, p ...

libraries and in manuscripts in Latin, Ethiopic, and Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

languages from later centuries, a body of hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

known as the ''Acts of Phileas

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

''.Clodius Culcianus

Clodius is an alternate form of the Roman '' nomen'' Claudius, a patrician ''gens'' that was traditionally regarded as Sabine in origin. The alternation of ''o'' and ''au'' is characteristic of the Sabine dialect. The feminine form is Clodia.

Rep ...

, the ''praefectus Aegypti

During the Roman Empire, the governor of Roman Egypt ''(praefectus Aegypti)'' was a prefect who administered the Roman province of Egypt with the delegated authority ''(imperium)'' of the emperor.

Egypt was established as a Roman province in cons ...

'' on 4 February 305 (the 10th day of ''Mecheir'').

In the western empire, the Diocletianic Persecution ceased with the usurpation by two emperors' sons in 306: that of Constantine, who was acclaimed ''augustus'' by the army after his father Constantius I () died, and that of Maxentius

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius (c. 283 – 28 October 312) was a Roman emperor, who reigned from 306 until his death in 312. Despite ruling in Italy and North Africa, and having the recognition of the Senate in Rome, he was not recognized ...

() who was elevated to ''augustus'' by the Roman Senate after the grudging retirement of his father Maximian

Maximian ( la, Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus; c. 250 – c. July 310), nicknamed ''Herculius'', was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was ''Caesar'' from 285 to 286, then ''Augustus'' from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his ...

() and his co-''augustus'' Diocletian in May 305. When Galerius died in May 311, he is reported by Lactantius and Eusebius to have composed a deathbed edict – the

When Galerius died in May 311, he is reported by Lactantius and Eusebius to have composed a deathbed edict – the Edict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

– allowing the assembly of Christians in conventicles and explaining the motives for the prior persecution.oracular

An oracle is a person or agency considered to provide wise and insightful counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. As such, it is a form of divination.

Description

The word ''or ...

pronouncement made by a statue of Zeus ''Philios'' set up in Antioch by Theotecnus of Antioch

Theotecnus was bishop of Caesarea Maritima in the late 3rd century.

References

*

{{end box

3rd-century bishops in the Roman Empire

Bishops of Caesarea

4th-century bishops in the Roman Empire ...

, who also organized an anti-Christian petition to be sent from the Antiochenes to Maximinus, requesting that the Christians there be expelled.Methodius Methodius or Methodios may refer to:

* Methodius of Olympus (d. 311), Christian bishop, church father, and martyr

*Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius, a seventh-century text purporting to be written by Methodius of Olympus

* Methodios I of Constantinop ...

of Olympus in Lycia, and Peter, the patriarch of Alexandria

The Patriarch of Alexandria is the archbishop of Alexandria, Egypt. Historically, this office has included the designation "pope" (etymologically "Father", like "Abbot").

The Alexandrian episcopate was revered as one of the three major episco ...

. Defeated in a civil war by the ''augustus'' Licinius (), Maximinus died in 313, ending the systematic persecution of Christianity as a whole in the Roman Empire.New Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''New Catholic Encyclopedia'' (NCE) is a multi-volume reference work on Roman Catholic history and belief edited by the faculty of The Catholic University of America. The NCE was originally published by McGraw-Hill in 1967. A second edition, ...

'' states that "Ancient, medieval and early modern hagiographers were inclined to exaggerate the number of martyrs. Since the title of martyr is the highest title to which a Christian can aspire, this tendency is natural". Attempts at estimating the numbers involved are inevitably based on inadequate sources.

Constantinian period

The Christian church marked the conversion of Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

as the final fulfillment of its heavenly victory over the "false gods".[Brown, Peter. "Christianization and religious conflict". The Cambridge Ancient History 13 (1998): 337–425.] The Roman state had always seen itself as divinely directed, now it saw the first great age of persecution, in which the Devil was considered to have used open violence to dissuade the growth of Christianity, at an end.[MacMullen, Ramsay (1997) ''Christianity & Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries'', Yale University Press, p.4 quote: "non Christian writings came in for this same treatment, that is destruction in great bonfires at the center of the town square. Copyists were discouraged from replacing them by the threat of having their hands cut off]

Peter Leithart says that, " onstantinedid not punish pagans for being pagans, or Jews for being Jews, and did not adopt a policy of forced conversion".schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

were persecuted during the reign of Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor, and they would be persecuted again later in the 4th century.Donatists

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and th ...

appealed to Constantine to solve a dispute. He convened a synod of bishops to hear the case, but the synod sided against them. The Donatists refused to accept the ruling, so a second gathering of 200 at Arles, in 314, was called, but they also ruled against them. The Donatists again refused to accept the ruling, and proceeded to act accordingly by establishing their own bishop, building their own churches, and refusing cooperation.[Cairns, Earle E. (1996). "Chapter 7:Christ or Caesar". Christianity Through the Centuries: A History of the Christian Church (Third ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. .] Constantine used the army in an effort to compel Donatist' obedience, burning churches and martyring some from 317 – 321.Pope Liberius

Pope Liberius (310 – 24 September 366) was the bishop of Rome from 17 May 352 until his death. According to the '' Catalogus Liberianus'', he was consecrated on 22 May as the successor to Pope Julius I. He is not mentioned as a saint in t ...

from Rome, and exiled bishops who refused to assent to Athanasius's exile.Dionysius

The name Dionysius (; el, Διονύσιος ''Dionysios'', "of Dionysus"; la, Dionysius) was common in classical and post-classical times. Etymologically it is a nominalized adjective formed with a -ios suffix from the stem Dionys- of the name ...

, bishop of Mediolanum ( Milan) was expelled from his episcopal see and replaced by the Arian Christian Auxentius of Milan. When Constantius returned to Rome in 357, he consented to allow the return of Liberius to the papacy; the Arian Pope Felix II

Antipope Felix (died 22 November 365) was a Roman archdeacon in the 4th century who was installed irregularly in 355 as an antipope and reigned until 365 after Emperor Constantius II banished the then current pope, Liberius. Constantius, foll ...

, who had replaced him, was then driven out along with his followers.Julian

Julian may refer to:

People

* Julian (emperor) (331–363), Roman emperor from 361 to 363

* Julian (Rome), referring to the Roman gens Julia, with imperial dynasty offshoots

* Saint Julian (disambiguation), several Christian saints

* Julian (give ...

() opposed Christianity and sought to restore traditional religion, though he did not arrange a general or official persecution.

Valentinianic–Theodosian period

According to the '' Collectio Avellana'', on the death of Pope Liberius in 366, Damasus, assisted by hired gangs of "charioteers" and men "from the arena", broke into the Basilica Julia to violently prevent the election of Pope Ursicinus

Ursicinus, also known as Ursinus, was elected pope in a violently contested election in 366 as a rival to Pope Damasus I. He ruled in Rome for several months in 366–367, was afterwards declared antipope, and died after 381.

Background

In 355, ...

.Viventius

Viventius ('' fl.'' 364 - 371) was a Roman official and administrator during the reign of Valentinian I.

A native of Siscia, in Pannonia, Viventius is first attested as holding the position of Quaestor sacri palatii in 364, one of a number of Pa ...

and the ''praefectus annonae

The ("prefect of the provisions"), also called the ("prefect of the grain supply") was a Roman official charged with the supervision of the grain supply to the city of Rome. Under the Republic, the job was usually done by an aedile. However, in ...

'' to exile Ursicinus.Valentinian the Great

Valentinian I ( la, Valentinianus; 32117 November 375), sometimes called Valentinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 364 to 375. Upon becoming emperor, he made his brother Valens his co-emperor, giving him rule of the eastern provinces. Vale ...

to remove Damasus from the throne of Saint Peter, calling him a murderer for having waged a "filthy war" against the Christians.state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

and as the state church of the Roman Empire

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion. ...

on 27 February 380. After this began state persecution of non-Nicene Christians, including Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

and Nontrinitarian devotees.[R. A. Markus, Saeculum: History and Society in the Theology of St.Augustine (Cambridge, 1970), pp. 149–153] By 408, Augustine supported the state's use of force against them.Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited t ...

as well as by Diocletian and Maximian.[Marcos, Mar. "The Debate on Religious Coercion in Ancient Christianity." Chaos e Kosmos 14 (2013): 1–16.] Augustine wrote that "coercion cannot transmit the truth to the heretic, but it can prepare them to hear and receive the truth".

Heraclian period

Callinicus I, initially a priest and ''skeuophylax'' in the Church of the Theotokos of Blachernae, became patriarch of Constantinople in 693 or 694.Great Palace

The Great Palace of Constantinople ( el, Μέγα Παλάτιον, ''Méga Palátion''; Latin: ''Palatium Magnum''), also known as the Sacred Palace ( el, Ἱερὸν Παλάτιον, ''Hieròn Palátion''; Latin: ''Sacrum Palatium''), was th ...

, the ''Theotokos ton Metropolitou'', and having possibly been involved in the deposition and exile of Justinian II (), an allegation denied by the ''Synaxarion of Constantinople'', he was himself exiled to Rome on the return of Justinian to power in 705.immured

Immurement (from the Latin , "in" and , "wall"; literally "walling in"), also called immuration or live entombment, is a form of imprisonment, usually until death, in which a person is sealed within an enclosed space without exits. This includes i ...

.

Sassanian Empire

Violent persecutions of Christians began in earnest in the long reign of Shapur II ().Kirkuk

Kirkuk ( ar, كركوك, ku, کەرکووک, translit=Kerkûk, , tr, Kerkük) is a city in Iraq, serving as the capital of the Kirkuk Governorate, located north of Baghdad. The city is home to a diverse population of Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds, ...

is recorded in Shapur's first decade, though most persecution happened after 341.Shemon Bar Sabbae

Mar Shimun Bar Sabbae ( syc, ܡܪܝ ܫܡܥܘܢ ܒܪܨܒܥܐ, died Good Friday, 345) was Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, from Persia, the ''de facto'' head of the Church of the East, until his death. He was bishop during the persecutions of King S ...

, the Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon

The Patriarch of the Church of the East (also known as Patriarch of the East, Patriarch of Babylon, the Catholicose of the East or the Grand Metropolitan of the East) is the patriarch, or leader and head bishop (sometimes referred to as Catholic ...

, refused to collect it.fire temple

A fire temple, Agiary, Atashkadeh ( fa, آتشکده), Atashgah () or Dar-e Mehr () is the place of worship for the followers of Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Iran (Persia).

In the Zoroastrian religion, fire (see ''atar''), together wi ...

by a Christian priest, and further persecutions occurred in the reign of Bahram V ().Yazdegerd II

Yazdegerd II (also spelled Yazdgerd and Yazdgird; pal, 𐭩𐭦𐭣𐭪𐭥𐭲𐭩), was the Sasanian King of Kings () of Iran from 438 to 457. He was the successor and son of Bahram V ().

His reign was marked by wars against the Eastern Roman ...

() an instance of persecution in 446 is recorded in the Syriac martyrology '' Acts of Ādur-hormizd and of Anāhīd''.Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

(), but there were likely no mass persecutions.Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

and its head, the Catholicose of the East

The Patriarch of the Church of the East (also known as Patriarch of the East, Patriarch of Babylon, the Catholicose of the East or the Grand Metropolitan of the East) is the patriarch, or leader and head bishop (sometimes referred to as Catholic ...

, were integrated into the administration of the empire and mass persecution was rare.Bahram I

Bahram I (also spelled Wahram I or Warahran I; pal, 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭) was the fourth Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 271 to 274. He was the eldest son of Shapur I () and succeeded his brother Hormizd I (), who had reigned for a year ...

and apparently a return to the policy of Shapur until the reign of Shapur II. The persecution at that time was initiated by Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given na ...

's conversion to Christianity which followed that of Armenian king Tiridates in about 301. The Christians were thus viewed with suspicions of secretly being partisans of the Roman Empire. This did not change until the fifth century when the Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

broke off from the Church of the West. Zoroastrian elites continued viewing the Christians with enmity and distrust throughout the fifth century with threat of persecution remaining significant, especially during war against the Romans.Kartir

Kartir (also spelled Karder, Karter and Kerdir; Middle Persian: 𐭪𐭫𐭲𐭩𐭫 ''Kardīr'') was a powerful and influential Zoroastrian priest during the reigns of four Sasanian kings in the 3rd-century. His name is cited in the inscriptions ...

, refers in his inscription dated about 280 on the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht monument in the Naqsh-e Rostam

Naqsh-e Rostam ( lit. mural of Rostam, fa, نقش رستم ) is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 12 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the ...

necropolis near Zangiabad, Fars

Zangiabad ( fa, زنگي اباد, also Romanized as Zangīābād) is a village in Naqsh-e Rostam Rural District, in the Central District of Marvdasht County, Fars Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, a ...

, to persecution (''zatan'' – "to beat, kill") of Christians ("Nazareans ''n'zl'y'' and Christians ''klstyd'n''"). Kartir took Christianity as a serious opponent. The use of the double expression may be indicative of the Greek-speaking Christians deported by Shapur I from Antioch and other cities during his war against the Romans. Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given na ...

's efforts to protect the Persian Christians made them a target of accusations of disloyalty to Sasanians. With the resumption of Roman-Sasanian conflict under Constantius II, the Christian position became untenable. Zoroastrian priests targeted clergy and ascetics of local Christians to eliminate the leaders of the church. A Syriac manuscript in Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

in 411 documents dozens executed in various parts of western Sasanian Empire.Shemon Bar Sabbae

Mar Shimun Bar Sabbae ( syc, ܡܪܝ ܫܡܥܘܢ ܒܪܨܒܥܐ, died Good Friday, 345) was Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, from Persia, the ''de facto'' head of the Church of the East, until his death. He was bishop during the persecutions of King S ...

informed him that he could not pay the taxes demanded from him and his community. He was martyred and a forty-year-long period of persecution of Christians began. The Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon gave up choosing bishops since it would result in death. The local '' mobads'' – Zoroastrian clerics – with the help of satraps organized slaughters of Christians in Adiabene, Beth Garmae, Khuzistan and many other provinces.

Yazdegerd I showed tolerance towards Jews and Christians for much of his rule. He allowed Christians to practice their religion freely, demolished monasteries and churches were rebuilt and missionaries were allowed to operate freely. He reversed his policies during the later part of his reign however, suppressing missionary activities. Bahram V continued and intensified their persecution, resulting in many of them fleeing to the eastern Roman empire. Bahram demanded their return, beginning the Roman–Sasanian War of 421–422

The Roman–Sasanian war of 421–422 was a conflict between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanians. The ''casus belli'' was the persecution of Christians by the Sassanid king Bahram V, which had come as a response to attacks by Christians ag ...

. The war ended with an agreement of freedom of religion for Christians in Iran with that of Mazdaism in Rome. Meanwhile, Christians suffered destruction of churches, renounced the faith, had their private property confiscated and many were expelled.

Yazdegerd II

Yazdegerd II (also spelled Yazdgerd and Yazdgird; pal, 𐭩𐭦𐭣𐭪𐭥𐭲𐭩), was the Sasanian King of Kings () of Iran from 438 to 457. He was the successor and son of Bahram V ().

His reign was marked by wars against the Eastern Roman ...

had ordered all his subjects to embrace Mazdeism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic ont ...

in an attempt to unite his empire ideologically. The Caucasus rebelled to defend Christianity which had become integrated in their local culture, with Armenian aristocrats turning to the Romans for help. The rebels were however defeated in a battle on the Avarayr Plain. Yeghishe

Yeghishe (, , AD 410 – 475; also spelled Eghishe or Ełišē, latinized Eliseus) was an Armenian historian from the time of late antiquity, best known as the author of ''History of Vardan and the Armenian War'', a history of a fifth-centu ...

in his ''The History of Vardan and the Armenian War'', pays a tribute to the battles waged to defend Christianity. Another revolt was waged from 481–483 which was suppressed. However, the Armenians succeeded in gaining freedom of religion among other improvements.

Accounts of executions for apostasy of Zoroastrians who converted to Christianity during Sasanian rule proliferated from the fifth to early seventh century, and continued to be produced even after collapse of Sasanians. The punishment of apostates increased under Yazdegerd I and continued under successive kings. It was normative for apostates who were brought to the notice of authorities to be executed, although the prosecution of apostasy depended on political circumstances and Zoroastrian jurisprudence. Per Richard E. Payne, the executions were meant to create a mutually recognised boundary between interactions of the people of the two religions and preventing one religion challenging another's viability. Although the violence on Christians was selective and especially carried out on elites, it served to keep Christian communities in a subordinate and yet viable position in relation to Zoroastrianism. Christians were allowed to build religious buildings and serve in the government as long as they did not expand their institutions and population at the expense of Zoroastrianism.

Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

was generally regarded as tolerant of Christians and interested in the philosophical and theological disputes during his reign. Sebeos

Sebeos () was a 7th-century Armenian bishop and historian.

Little is known about the author, though a signature on the resolution of the Ecclesiastical Council of Dvin in 645 reads 'Bishop Sebeos of Bagratunis.' His writings are valuable as one o ...

claimed he had converted to Christianity on his deathbed. John of Ephesus describes an Armenian revolt where he claims that Khusrow had attempted to impose Zoroastrianism in Armenia. The account, however, is very similar to the one of Armenian revolt of 451. In addition, Sebeos does not mention any religious persecution in his account of the revolt of 571. A story about Hormizd IV's tolerance is preserved by the historian al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

. Upon being asked why he tolerated Christians, he replied, "Just as our royal throne cannot stand upon its front legs without its two back ones, our kingdom cannot stand or endure firmly if we cause the Christians and adherents of other faiths, who differ in belief from ourselves, to become hostile to us."

During the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628

Several months after the Persian conquest in AD 614, a riot occurred in Jerusalem, and the Jewish governor of Jerusalem Nehemiah was killed by a band of young Christians along with his "council of the righteous" while he was making plans for the building of the Third Temple. At this time the Christians had allied themselves with the Eastern Roman Empire. Shortly afterward, the events escalated into a full-scale Christian rebellion, resulting in a battle against the Jews and Christians who were living in Jerusalem. In the battle's aftermath, many Jews were killed and the survivors fled to Caesarea, which was still being held by the Persian army.

The Judeo-Persian reaction was ruthless – Persian Sasanian general Xorheam assembled Judeo-Persian troops and went and encamped around Jerusalem and besieged it for 19 days.Sebeos

Sebeos () was a 7th-century Armenian bishop and historian.

Little is known about the author, though a signature on the resolution of the Ecclesiastical Council of Dvin in 645 reads 'Bishop Sebeos of Bagratunis.' His writings are valuable as one o ...

, the siege resulted in a total Christian death toll of 17,000, the earliest and thus most commonly accepted figure.Strategius

Strategius was a 7th-century monk of Mar Saba. He wrote a sermon on the siege and sack of Jerusalem in 614 and its aftermath, the forcible relocation of some of its inhabitants to Ctesiphon and the efforts of the Patriarch Zacharias to stiffen t ...

, 4,518 prisoners alone were massacred near Mamilla reservoir.[The Persian Conquest of Jerusalem (614 CE) – an archeological assessment](_blank)

by Gideon Avni, Director of the Excavations and Surveys Department of the Israel Antiquities Authority. A cave containing hundreds of skeletons near the Jaffa Gate

Jaffa Gate ( he, שער יפו, Sha'ar Yafo; ar, باب الخليل, Bāb al-Khalīl, "Hebron Gate") is one of the seven main open Gates of the Old City of Jerusalem.

The name Jaffa Gate is currently used for both the historical Ottoman gate ...

, 200 metres east of the large Roman-era pool in Mamilla, correlates with the massacre of Christians at hands of the Persians mentioned in the writings of Strategius. While reinforcing the evidence of massacre of Christians, the archaeological evidence seem less conclusive on the destruction of Christian churches and monasteries in Jerusalem.Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

, it is clear that all churches had been destroyed during the period between the Persian invasion and the Arab conquest in 637. The church at Shave Ziyyon was destroyed and burnt in 614. Similar fate befell churches at Evron, Nahariya

Nahariya ( he, נַהֲרִיָּה, ar, نهاريا) is the northernmost coastal city in Israel. In it had a population of .

Etymology

Nahariya takes its name from the stream of Ga'aton (river is ''nahar'' in Hebrew), which bisects it.

Hist ...

, 'Arabe and monastery of Shelomi. The monastery at Kursi

Kursi may refer to:

* Throne ( ar, links=no, كرسي, kursi)

* ''Kursi'', local name for the Curonians, a Baltic tribe

* Kursi, Harju County, village in Kuusalu Parish, Harju County, Estonia

* Kursi, Jõgeva County, village in Põltsamaa Parish, ...

was damaged in the invasion.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

In AD 516, tribal unrest broke out in Yemen and several tribal elites fought for power. One of those elites was Joseph Dhu Nuwas or "Yousef Asa'ar", a Jewish king of the Himyarite Kingdom who is mentioned in ancient south Arabian inscriptions. Syriac and Byzantine Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the Ottoman co ...

sources claim that he fought his war because Christians in Yemen refused to renounce Christianity. In 2009, a documentary that aired on the BBC defended the claim that the villagers had been offered the choice between conversion to Judaism or death and 20,000 Christians were then massacred by stating that "The production team spoke to many historians over a period of 18 months, among them Nigel Groom, who was our consultant, and Professor Abdul Rahman Al-Ansary, a former professor of archaeology at the King Saud University in Riyadh." Inscriptions documented by Yousef himself show the great pride that he expressed after killing more than 22,000 Christians in Zafar and Najran

Najran ( ar, نجران '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia near the border with Yemen. It is the capital of Najran Province. Designated as a new town, Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom; its population has risen fr ...

. Historian Glen Bowersock

Glen Warren Bowersock (born January 12, 1936 in Providence, Rhode Island) is a historian of ancient Greece, Rome and the Near East, and former Chairman of Harvard’s classics department.

Early life

Bowersock was born in Providence, Rhode Island a ...

described this massacre as a "savage pogrom that the Jewish king of the Arabs launched against the Christians in the city of Najran. The king himself reported in excruciating detail to his Arab and Persian allies about the massacres that he had inflicted on all Christians who refused to convert to Judaism."

Early Middle Ages

Muhammad

Ancient Arabian Christianity has largely vanished from the region. The main reason for is Prophet Muhammad's direct orders to eliminate Jews and Christians from Arabia.

Sahih Muslim 1767 a

Musnad Ahmad 201

Musnad Ahmad 215

Rashidun Caliphate

Since they are considered "People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

" in the Islamic religion

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or ''Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main ...

, Christians under Muslim rule were subjected to the status of ''dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

'' (along with Jews, Samaritans

Samaritans (; ; he, שומרונים, translit=Šōmrōnīm, lit=; ar, السامريون, translit=as-Sāmiriyyūn) are an ethnoreligious group who originate from the ancient Israelites. They are native to the Levant and adhere to Samarit ...

, Gnostics

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

, Mandeans, and Zoroastrians), which was inferior to the status of Muslims.persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in that they were banned from proselytising

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

(for Christians, it was forbidden to evangelize or spread Christianity) in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslims on pain of death, they were banned from bearing arms, undertaking certain professions, and were obligated to dress differently in order to distinguish themselves from Arabs.jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent Kafir, non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The jizya tax has been unde ...

'' and ''kharaj

Kharāj ( ar, خراج) is a type of individual Islamic tax on agricultural land and its produce, developed under Islamic law.

With the first Muslim conquests in the 7th century, the ''kharaj'' initially denoted a lump-sum duty levied upon the ...

'' taxes,ransom

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or the sum of money involved in such a practice.

When ransom means "payment", the word comes via Old French ''rançon'' from Latin ''red ...

levied upon Christian communities by Muslim rulers in order to fund military campaigns, all of which contributed a significant proportion of income to the Islamic states while conversely reducing many Christians to poverty, and these financial and social hardships forced many Christians to convert to Islam.Syriac Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = St_George_Syriac_orthodox_church_in_Damascus.jpg

, imagewidth = 250

, alt = Cathedral of Saint George

, caption = Cathedral of Saint George, Damascus ...

, the Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant ( ar, فَتْحُ الشَّام, translit=Feth eş-Şâm), also known as the Rashidun conquest of Syria, occurred in the first half of the 7th century, shortly after the rise of Islam."Syria." Encyclopædia Br ...

was a relief for Christians oppressed by the Western Roman Empire.Michael the Syrian

Michael the Syrian ( ar, ميخائيل السرياني, Mīkhaʾēl el Sūryani:),( syc, ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܣܽܘܪܝܳܝܳܐ, Mīkhoʾēl Sūryoyo), died 1199 AD, also known as Michael the Great ( syr, ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܪܰܒ݁ܳܐ, ...

, patriarch of Antioch, wrote later that the Christian God had "raised from the south the children of Ishmael

The Ishmaelites ( he, ''Yīšməʿēʾlīm,'' ar, بَنِي إِسْمَاعِيل ''Bani Isma'il''; "sons of Ishmael") were a collection of various Arabian tribes, confederations and small Realm, kingdoms described in Islamic tradition as bei ...

to deliver us by them from the hands of the Romans".Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Lebanon, and Armenia resented either the governance of the Western Roman Empire or that of the Byzantine Empire, and therefore preferred to live under more favourable economic and political conditions as ''dhimmi'' under the Muslim rulers.religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within soc ...

, religious violence, and martyrdom multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers;

Umayyad Caliphate

According to the

According to the Ḥanafī

The Hanafi school ( ar, حَنَفِية, translit=Ḥanafiyah; also called Hanafite in English), Hanafism, or the Hanafi fiqh, is the oldest and one of the four traditional major Sunni schools (maddhab) of Islamic Law (Fiqh). It is named afte ...

school of Islamic law (''sharīʿa''), the testimony of a Non-Muslim (such as a Christian or a Jew) was not considered valid against the testimony of a Muslim in legal or civil matters. Historically, in Islamic culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predomi ...

and traditional Islamic law Muslim women have been forbidden from marrying Christian or Jewish men, whereas Muslim men have been permitted to marry Christian or Jewish women (''see'': Interfaith marriage in Islam). Christians under Islamic rule had the right to convert to Islam or any other religion, while conversely a '' murtad'', or an apostate from Islam, faced severe penalties or even '' hadd'', which could include the Islamic death penalty.Mālikī

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Fiqh, Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as pri ...

school of Islamic law was the most prevalent.Eulogius of Córdoba

Saint Eulogius of Córdoba ( es, San Eulogio de Córdoba (died 11 March 857) was one of the Martyrs of Córdoba. He flourished during the reigns of the Cordovan emirs Abd-er-Rahman II and Muhammad I (mid-9th century).

Background

In the ninth ...

.blasphemy

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religiou ...

.

Byzantine Empire

George Limnaiotes, a monk on Mount Olympus known only from the '' Synaxarion of Constantinople'' and other synaxaria

Synaxarion or Synexarion (plurals Synaxaria, Synexaria; el, Συναξάριον, from συνάγειν, ''synagein'', "to bring together"; cf. etymology of ''synaxis'' and ''synagogue''; Latin: ''Synaxarium'', ''Synexarium''; cop, ⲥⲩⲛⲁ ...

, was supposed to have been 95 years old when he was tortured for his iconodulism

Iconodulism (also iconoduly or iconodulia) designates the religious service to icons (kissing and honourable veneration, incense, and candlelight). The term comes from Neoclassical Greek εἰκονόδουλος (''eikonodoulos'') (from el, ε ...

.Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was List of Byzantine emperors, Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exa ...

(), having been castrated and enrolled in the cathedral clergy of Hagia Sophia when his father was executed in 669, was later bishop of Cyzicus and then patriarch of Constantinople from 715.Nikephoros I

Nikephoros I or Nicephorus I ( gr, Νικηφόρος; 750 – 26 July 811) was Byzantine emperor from 802 to 811. Having served Empress Irene as '' genikos logothetēs'', he subsequently ousted her from power and took the throne himself. In r ...

() at the Battle of Pliska

The Battle of Pliska or Battle of Vărbitsa Pass was a series of battles between troops, gathered from all parts of the Byzantine Empire, led by the Emperor Nicephorus I, and the First Bulgarian Empire, governed by Khan Krum. The Byzantines plu ...

in 811, the First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire ( cu, блъгарьско цѣсарьствиѥ, blagarysko tsesarystviye; bg, Първо българско царство) was a medieval Bulgar- Slavic and later Bulgarian state that existed in Southeastern Europ ...

's ''khan

Khan may refer to:

*Khan (inn), from Persian, a caravanserai or resting-place for a travelling caravan

*Khan (surname), including a list of people with the name

*Khan (title), a royal title for a ruler in Mongol and Turkic languages and used by ...

'', Krum, also put to death a number of Roman soldiers who refused to renounce Christianity, though these martyrdoms, known only from the ''Synaxarion of Constantinople'', may be entierely legendary.Leo IV the Khazar

Leo IV the Khazar (Greek: Λέων ὁ Χάζαρος, ''Leōn IV ho Khazaros''; 25 January 750 – 8 September 780) was Byzantine emperor from 775 to 780 AD. He was born to Emperor Constantine V and Empress Tzitzak in 750. He was elevated to c ...

() in return for the repudiation of his iconodulism, was expelled from the monastery by Leo V the Armenian

Leo V the Armenian ( gr, Λέων ὁ ἐξ Ἀρμενίας, ''Leōn ho ex Armenias''; 775 – 25 December 820) was the Byzantine emperor from 813 to 820. A senior general, he forced his predecessor, Michael I Rangabe, to abdicate and assumed ...

(), who also imprisoned and exiled him.Athanasios of Paulopetrion

Athanasios ( el, Αθανάσιος), also transliterated as Athnasious, Athanase or Atanacio, is a Greek male name which means "immortal". In modern Greek everyday use, it is commonly shortened to Thanasis (Θανάσης), Thanos (Θάνος), ...

was tortured and exiled for his iconophilism by the emperor Leo V.Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

, and then in the fortress of Kriotauros in the Bucellarian ''thema''.Avşa

Avşa Island ( tr, Avşa Adası) or Türkeli is a Turkish island in the southern Sea of Marmara with an area of about . It was the classical and Byzantine Aphousia ( el, Ἀφουσία or Ἀφησιά) and was a place of exile during the Byzant ...

) where he died, probably in 835.Eustratios of Agauros

Eustratius or Eustratios, in modern transliteration Efstratios (Greek: Εὐστράτιος/Greek: Ευστράτιος) is a Greek given name. Its diminutive form is Stratos (Greek: Στράτος) or Stratis (Greek: Στρατής or Greek: Στ ...

, a monk and '' hegumenos'' of the Agauros Monastery at the foot of Mount Trichalikos, near Prusa's Mount Olympus in Bithynia, was forced into exile by the persecutions of Leo V and Theophilos ().Hilarion of Dalmatos

Hilarion the Great (291–371) was an anchorite who spent most of his life in the desert according to the example of Anthony the Great (c. 251–356). While St Anthony is considered to have established Christian monasticism in the Egyptian de ...

, the son of Peter the Cappadocian

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a ...

, who had been made ''hegumenos'' of the Dalmatos Monastery by the patriarch Nikephoros I.Michael Synkellos Michael Synkellos ( gr, Μιχαήλ o σύγκελλος), also spelled Syncellus (c. 760 – 4 January 846), was a Greek Orthodox Arab Christian priest, monk and saint. He held the administrative office of ''synkellos'' of the Greek Orthodo ...

, an Arab monk of the Mar Saba

The Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas, known in Arabic and Syriac as Mar Saba ( syr, ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܣܒܐ, ar, دير مار سابا; he, מנזר מר סבא; el, Ἱερὰ Λαύρα τοῦ Ὁσίου Σάββα τοῦ Ἡγιασμέ� ...

monastery in Palestine who, as the '' syncellus'' of the patriarch of Jerusalem, had travelled to Constantinople on behalf of the patriarch Thomas I.Chora Monastery

'' '' tr, Kariye Mosque''

, image = Chora Church Constantinople 2007 panorama 002.jpg

, caption = Exterior rear view

, map_type = Istanbul Fatih

, map_size = 220px

, map_caption ...

.George of Mytilene

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

, who may have been Symeon's brother, was exiled from Constantinople in 815 on account of his iconophilia. He spent the last six years of his life in exile on an island, probably one of the Princes' Islands, dying in 820 or 821. The bishop

The bishop Euthymius of Sardis

Euthymius of Sardis ( el, Εὐθύμιος Σάρδεων; 751 or 754 – 26 December 831) was metropolitan bishop of Sardis between ca. 785 and ca. 804, and a leading iconophile during the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm. Martyred in 831, he is a ...

was the victim of several iconoclast Christian persecutions. Euthymius had previously been exiled to Pantelleria by the emperor Nikephoros I

Nikephoros I or Nicephorus I ( gr, Νικηφόρος; 750 – 26 July 811) was Byzantine emperor from 802 to 811. Having served Empress Irene as '' genikos logothetēs'', he subsequently ousted her from power and took the throne himself. In r ...

(), recalled in 806, led the iconodule resistance against Leo V (), and exiled again to Thasos in 814.Michael II

Michael II ( gr, Μιχαὴλ, , translit=Michaēl; 770–829), called the Amorian ( gr, ὁ ἐξ Ἀμορίου, ho ex Amoríou) and the Stammerer (, ''ho Travlós'' or , ''ho Psellós''), reigned as Byzantine Emperor from 25 December 820 to ...

(), he was again imprisoned and exiled to Saint Andrew's Island, off Cape Akritas ( Tuzla, Istanbul).iconodulism

Iconodulism (also iconoduly or iconodulia) designates the religious service to icons (kissing and honourable veneration, incense, and candlelight). The term comes from Neoclassical Greek εἰκονόδουλος (''eikonodoulos'') (from el, ε ...

; Theoktistos was active in the persecution of iconodules under the iconoclast emperors, but later championed the iconodule cause.Byzantine pound

The pound or pound-mass is a unit of mass used in British imperial and United States customary systems of measurement. Various definitions have been used; the most common today is the international avoirdupois pound, which is legally define ...