Haakon IV of Norway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Haakon IV Haakonsson ( – 16 December 1263;

Haakon's councillors had sought to reconcile Haakon and Skule by proposing marriage between Haakon and Skule's daughter

Haakon's councillors had sought to reconcile Haakon and Skule by proposing marriage between Haakon and Skule's daughter

After consolidating his position in 1240, Haakon focused on displaying the supremacy of the kingship, influenced by the increasingly closer contact with European culture. He started constructing several monumental royal buildings, primarily in the royal estate in Bergen where he built a European-style stone palace. He used a grand fleet with stately royal ships when meeting with other Scandinavian rulers, and actively sent letters and gifts to other European rulers; his most far-reaching contact was achieved when he sent

After consolidating his position in 1240, Haakon focused on displaying the supremacy of the kingship, influenced by the increasingly closer contact with European culture. He started constructing several monumental royal buildings, primarily in the royal estate in Bergen where he built a European-style stone palace. He used a grand fleet with stately royal ships when meeting with other Scandinavian rulers, and actively sent letters and gifts to other European rulers; his most far-reaching contact was achieved when he sent

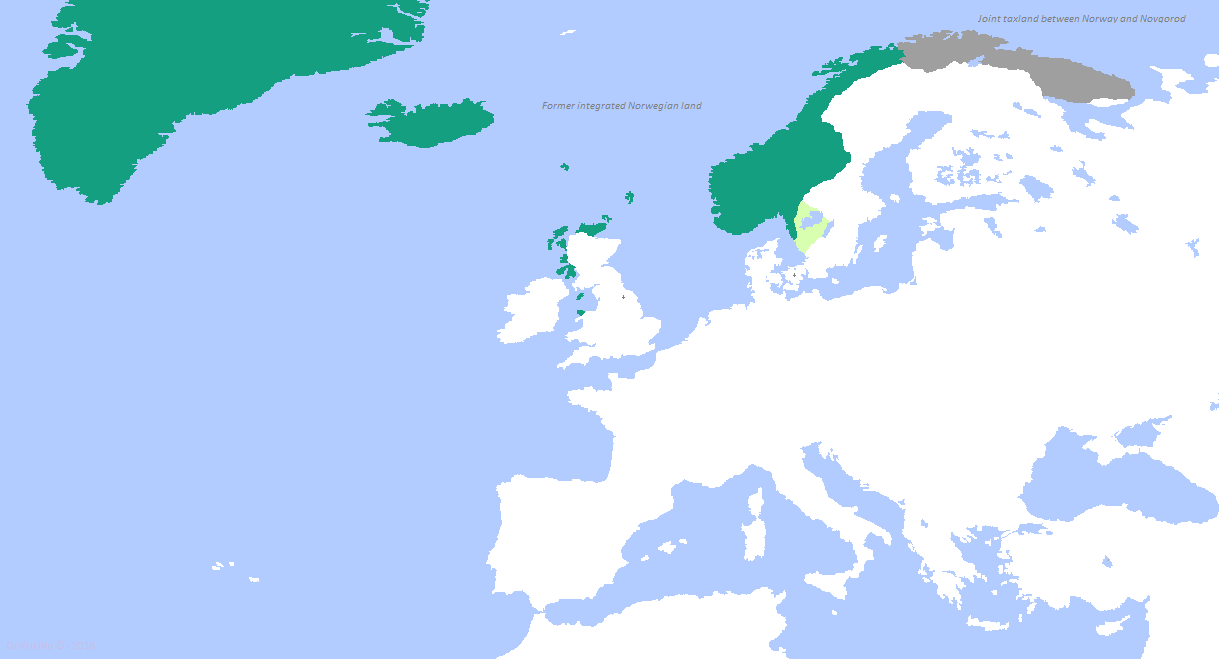

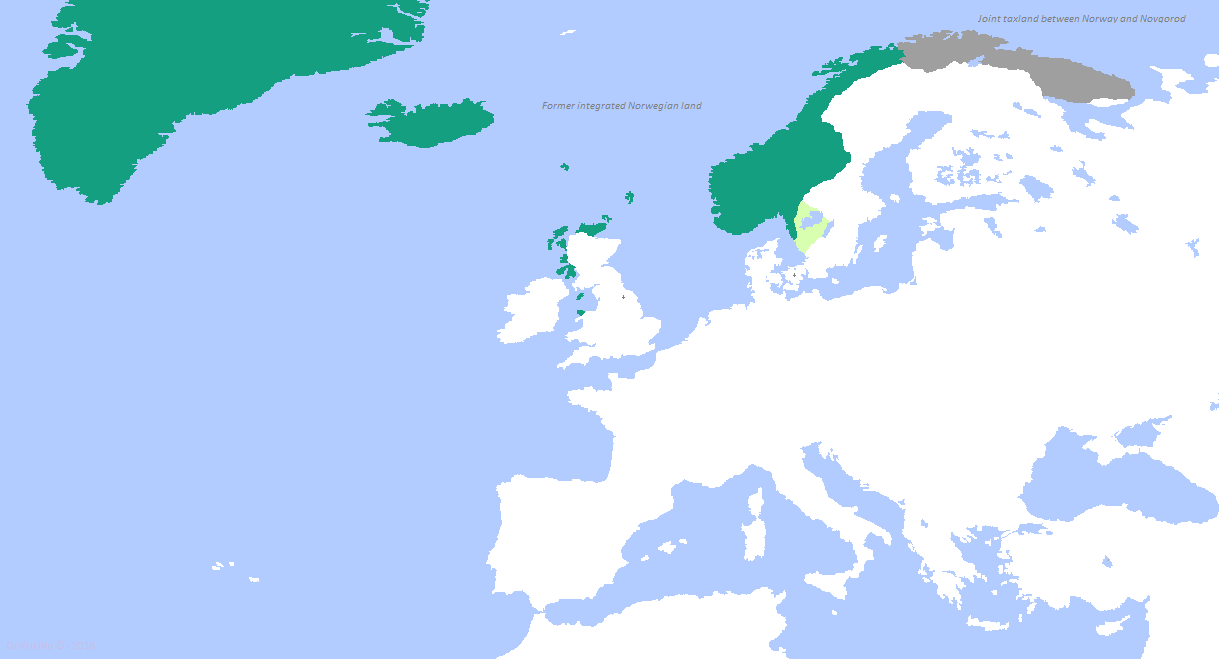

Haakon employed an active and aggressive foreign policy towards strengthening Norwegian ties in the west.Helle, 1995, p. 194. His policy relied on friendship and trade with the English king; the first known Norwegian trade agreements were made with England in the years 1217–23 (England's first commercial treaties were also made with Norway), and the friendship with

Haakon employed an active and aggressive foreign policy towards strengthening Norwegian ties in the west.Helle, 1995, p. 194. His policy relied on friendship and trade with the English king; the first known Norwegian trade agreements were made with England in the years 1217–23 (England's first commercial treaties were also made with Norway), and the friendship with

Haakon had three illegitimate children with his mistress Kanga the Younger av Folkindberg (who is only known by name) (1198–1225), before 1225. They were:Keyser, 1870, p. 230.

* Sigurd (died 1252).

* Cecilia (died 1248). Married ''

Haakon had three illegitimate children with his mistress Kanga the Younger av Folkindberg (who is only known by name) (1198–1225), before 1225. They were:Keyser, 1870, p. 230.

* Sigurd (died 1252).

* Cecilia (died 1248). Married ''

Olympic.org In ''

Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

: ''Hákon Hákonarson'' ; Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

: ''Håkon Håkonsson''), sometimes called Haakon the Old in contrast to his namesake son, was King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingdoms ...

from 1217 to 1263. His reign lasted for 46 years, longer than any Norwegian king since Harald Fairhair

Harald Fairhair no, Harald hårfagre Modern Icelandic: ( – ) was a Norwegian king. According to traditions current in Norway and Iceland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, he reigned from 872 to 930 and was the first King of Nor ...

. Haakon was born into the troubled civil war era in Norway

The civil war era in Norway ( no, borgerkrigstida or ''borgerkrigstiden'') began in 1130 and ended in 1240. During this time in history of Norway, Norwegian history, some two dozen rival kings and pretenders War of succession, waged wars to clai ...

, but his reign eventually managed to put an end to the internal conflicts. At the start of his reign, during his minority, Earl Skule Bårdsson

Skule Bårdsson or Duke Skule ( Norwegian: Hertug Skule) (Old Norse: Skúli Bárðarson) ( – 24 May 1240) was a Norwegian nobleman and claimant to the royal throne against his son-in-law, King Haakon Haakonsson. Henrik Ibsen's play '' Kongs ...

served as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

. As a king of the birkebeiner

The Birkebein Party or Birkebeinar (; no, Birkebeinarane (nynorsk) or (bokmål)) was the name for a rebellious party in Norway, formed in 1174 around the pretender to the Norwegian throne, Eystein Meyla. The name has its origins in propagand ...

faction, Haakon defeated the uprising of the final bagler

The Bagli Party or Bagler (Old Norse: ''Baglarr'', Norwegian Bokmål: ''Bagler'', Norwegian Nynorsk: ''Baglar'') was a faction or party during the Norwegian Civil Wars. The Bagler faction was made up principally of the Norwegian aristocracy, clerg ...

royal pretender, Sigurd Ribbung

Sigurd Erlingsson Ribbung (old Norse language, Old Norse: ''Sigurðr ribbungr'') (died 1226) was a Norwegian nobleman and pretender to the throne of Norway during the civil war era in Norway.

Biography

Sigurd Erlingsson's father was Erling Steinve ...

, in 1227. He put a definitive end to the civil war era when he had Skule Bårdsson killed in 1240, a year after he had himself proclaimed king in opposition to Haakon. Haakon thereafter formally appointed his own son as his co-regent

A coregency is the situation where a monarchical position (such as prince, princess, king, queen, emperor or empress), normally held by only a single person, is held by two or more. It is to be distinguished from diarchies or duumvirates such ...

.

Under Haakon's rule, medieval Norway is considered to have reached its zenith or golden age. His reputation and formidable naval fleet allowed him to maintain friendships with both the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

, despite their conflict. He was at different points offered the imperial crown by the pope, the Irish high kingship by a delegation of Irish kings, and the command of the French crusader fleet by the French king. He amplified the influence of European culture in Norway by importing and translating contemporary European literature into Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

, and by constructing monumental European-style stone buildings. In conjunction with this he employed an active and aggressive foreign policy, and at the end of his rule added Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

and the Norse Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

community to his kingdom, leaving the Norwegian realm

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

at its territorial height. Although he for the moment managed to secure Norwegian control of the islands off the northern and western shores of Scotland, plus the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, he fell ill and died when wintering in Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

following some military engagements with the expanding Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a la ...

.

Historical sources

The main source of information concerning Haakon is the '' Saga of Haakon Haakonsson'', which was written in the immediate years following his death. Commissioned by his sonMagnus

Magnus, meaning "Great" in Latin, was used as cognomen of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus in the first century BC. The best-known use of the name during the Roman Empire is for the fourth-century Western Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus. The name gained wid ...

, it was written by the Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

ic writer and politician Sturla Þórðarson

Sturla Þórðarson ( ; ; 29 July 1214–30 July 1284) was an Icelandic chieftain and writer of sagas and contemporary history during the 13th century.

Biography

The life of Sturla Þórðarson was chronicled in the Sturlunga saga.

Sturla was th ...

(nephew of the famous historian Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of the ...

). Having come into conflict with the royal representative in Iceland, Sturla came to Norway in 1263 in an attempt to reconcile with Haakon. When he arrived, he learned that Haakon was in Scotland, and that Magnus ruled Norway in his place. While Magnus initially took an unfriendly attitude towards Sturla, his talents as a story-teller and skald

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditionally ...

eventually won him the favour of Magnus and his men. The saga is considered the most detailed and reliable of all sagas concerning Norwegian kings, building on both written archive material and oral information from individuals who had been close to Haakon. It is nonetheless written openly in support of the political program of the House of Sverre

The House of Sverre ( no, Sverreætten) was a royal house or dynasty which ruled, at various times in history, the Kingdom of Norway, hereunder the kingdom's realms, and the Kingdom of Scotland. The house was founded with King Sverre Sigurdsson ...

, and the legitimacy of Haakon's kingship.

Background and childhood

Haakon was born in Folkenborg (now inEidsberg

Eidsberg was a municipality in Østfold county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality was the town of Mysen. In 2020, Eidsberg was absorbed into the Indre Østfold municipality.

Eidsberg was established as a municipality on 1 Jan ...

) to Inga of Varteig

Inga Olafsdatter of Varteig (''Inga Olafsdatter fra Varteig'') ( Varteig, Østfold, 1183 or 1185 – 1234 or 1235) was the mistress of King Haakon III of Norway and the mother of King Haakon IV of Norway.

Biography

Inga, from Varteig in � ...

in the summer of 1204, probably in March or April. The father was widely regarded to have been King Haakon Sverresson, the leader of the birkebeiner

The Birkebein Party or Birkebeinar (; no, Birkebeinarane (nynorsk) or (bokmål)) was the name for a rebellious party in Norway, formed in 1174 around the pretender to the Norwegian throne, Eystein Meyla. The name has its origins in propagand ...

faction in the ongoing civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

against the bagler

The Bagli Party or Bagler (Old Norse: ''Baglarr'', Norwegian Bokmål: ''Bagler'', Norwegian Nynorsk: ''Baglar'') was a faction or party during the Norwegian Civil Wars. The Bagler faction was made up principally of the Norwegian aristocracy, clerg ...

, as Inga had been with Haakon in his hostel in Borg (now Sarpsborg

Sarpsborg ( or ), historically Borg, is a city and municipality in Viken county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Sarpsborg.

Sarpsborg is part of the fifth largest urban area in Norway when paired with neigh ...

) in late 1203. Haakon Sverresson was dead by the time his son Haakon was born (many believed to have been poisoned by his Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

stepmother Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

), but Inga's claim was supported by several of Haakon Sverresson's followers. Haakon was born in bagler-controlled territory, and his mother's claim placed them in a dangerous position. While the bagler started hunting Haakon, a group of birkebeiner warriors fled with the child in the winter of 1205/06, heading for King Inge Bårdson, the new birkebeiner king in Nidaros

Nidaros, Niðarós or Niðaróss () was the medieval name of Trondheim when it was the capital of Norway's first Christian kings. It was named for its position at the mouth (Old Norse: ''óss'') of the River Nid (the present-day Nidelva).

Althou ...

(now Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

). As the party was struck by a blizzard, two of the best birkebeiner skiers

Skiing is the use of skis to glide on snow. Variations of purpose include basic transport, a recreational activity, or a competitive winter sport. Many types of competitive skiing events are recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IO ...

, Torstein Skevla and Skjervald Skrukka, carried on with the child over the mountain from Lillehammer

Lillehammer () is a municipality in Innlandet county, Norway. It is located in the traditional district of Gudbrandsdal. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Lillehammer. Some of the more notable villages in the municip ...

to Østerdalen

Østerdalen () is a valley and traditional district in Innlandet county, in Eastern Norway. This area typically is described as the large Glåma river valley as well as all its tributary valleys. It includes the municipalities Rendalen, Alvdal, F ...

. They eventually managed to bring Haakon to safety with King Inge; this particular event is commemorated in modern-day Norway by the popular annual skiing event ''Birkebeinerrennet

Birkebeinerrennet (lit. The Birkebeiner race) is a long-distance cross-country ski marathon held annually in Norway. It debuted in 1932 and has been a part of Worldloppet since Worldloppet's inception in 1979.

The Birkebeinerrennet is one of th ...

''. Haakon's dramatic childhood was often parallelled with that of former king Olaf Tryggvasson

Olaf Tryggvason (960s – 9 September 1000) was King of Norway from 995 to 1000. He was the son of Tryggvi Olafsson, king of Viken (Vingulmark, and Rånrike), and, according to later sagas, the great-grandson of Harald Fairhair, first King of N ...

(who introduced Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

to Norway),Bagge, 1996, p. 95. as well as with the gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

s and Child Jesus

The Christ Child, also known as Divine Infant, Baby Jesus, Infant Jesus, the Divine Child, Child Jesus, the Holy Child, Santo Niño, and to some as Señor Noemi refers to Jesus Christ from his nativity to age 12.

The four canonical gospels, ...

, which served as an important ideological function for his kingship.

In the saga, Haakon is described as bright and witty, and as being small for his age. When he was three years old, Haakon was captured by the bagler but refused to call the bagler king Philip Simonsson Philip Simonsson (Old Norse: ''Filippus Símonsson'') (ca. 1185-1217) was a Norwegian aristocrat and from 1207 to 1217 was the Bagler party pretender to the throne of Norway during the civil war era in Norway.

Background

Philip was the son of Simon ...

his lord (he nonetheless came from the capture unharmed). When he learned at the age of eight that King Inge and his brother Earl Haakon the Crazy

Haakon the Crazy (Old Norse: ''Hákon galinn'', Norwegian: ''Håkon Galen'') was a Norwegian ''jarl'' and Birkebeiner chieftain during the civil war era in Norway. Håkon Galen was born no later than the 1170s and died in 1214. His epithet "the cr ...

had made an agreement of the succession to the throne that excluded himself, he pointed out that the agreement was invalid due to his attorney not having been present. He subsequently identified his attorney as "God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

and Saint Olaf

Olaf II Haraldsson ( – 29 July 1030), later known as Saint Olaf (and traditionally as St. Olave), was King of Norway from 1015 to 1028. Son of Harald Grenske, a petty king in Vestfold, Norway, he was posthumously given the title ''Rex Perpet ...

." Haakon was notably the first Norwegian king to receive formal education at a school. From the late civil war era, the government administration relied increasingly on written communication, which in turn demanded literate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

leaders. When Haakon was in Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

under the care of Haakon the Crazy, he started receiving education from the age of seven, likely at the Bergen Cathedral School

Bergen Cathedral School (Norwegian: ''Bergen Katedralskole'', Latin: ''Schola Cathedralis Bergensis'', formerly known as Bergens lærdeskole and Bergen latinskole and colloquially known as Katten) is an upper secondary school in Bergen, Norway. Loc ...

. He continued his education under King Inge at the Trondheim Cathedral School

Trondheim Cathedral School ( no, Trondheim katedralskole, Latin: ''Schola Cathedralis Nidrosiensis'') is an upper secondary school located next to the Nidaros Cathedral in the center of Trondheim, Norway.

History

There is great dispute regarding ...

after the Earl's death in 1214. Haakon was brought up alongside Inge's son Guttorm, and they were treated as the same. When he was eleven, some of Haakon's friends provoked the king by asking him to give Haakon a region to govern. When Haakon was approached by the men and was urged to take up arms against Inge, he rejected it in part because of his young age and its bad prospects, as well as because he believed it would be morally wrong to fight Inge and thus split the birkebeiner. He instead said that he prayed that God would give him his share of his father's inheritance when the time was right.

Reign

Succession struggle

After King Inge's death in 1217, a dispute erupted over who was to become his successor. In addition to Haakon who gained the support of the majority of the birkebeiners including the veterans who had served under his father and grandfather, candidates included Inge's illegitimate son Guttorm (who dropped out very soon), Inge's half-brother EarlSkule Bårdsson

Skule Bårdsson or Duke Skule ( Norwegian: Hertug Skule) (Old Norse: Skúli Bárðarson) ( – 24 May 1240) was a Norwegian nobleman and claimant to the royal throne against his son-in-law, King Haakon Haakonsson. Henrik Ibsen's play '' Kongs ...

who had been appointed leader of the king's ''hird

The hird (also named "Håndgangne Menn" in Norwegian), in Scandinavian history, was originally an informal retinue of personal armed companions, hirdmen or housecarls, but came to mean not only the nucleus ('Guards') of the royal army, but also d ...

'' at Inge's deathbed and was supported by the Archbishop of Nidaros

The Archdiocese of Nidaros (or Niðaróss) was the metropolitan see covering Norway in the later Middle Ages. The see was the Nidaros Cathedral, in the city of Nidaros (now Trondheim). The archdiocese existed from the middle of the twelfth centu ...

as well as part of the birkebeiners, and Haakon the Crazy's son Knut Haakonsson Knut Haakonsson (''Knut Håkonsson'', Old Norse ''Knútr Hákonarson'') (c. 1208–1261) was a Norwegian nobleman and claimant to the throne during the Civil war era in Norway.

Biography

Haakonsson was born the son of jarl Haakon the Crazy ('' ...

.Helle, 1995, p. 75.Keyser, 1870, p. 184. With his widespread popular support in Trøndelag

Trøndelag (; sma, Trööndelage) is a county in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County ( no, Trondhjems Amt); in 1804 the county was split into Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag by the King of Denmar ...

and in Western Norway

Western Norway ( nb, Vestlandet, Vest-Norge; nn, Vest-Noreg) is the region along the Atlantic coast of southern Norway. It consists of the counties Rogaland, Vestland, and Møre og Romsdal. The region has no official or political-administrativ ...

, Haakon was proclaimed king at Øyrating in June 1217. He was later the same year hailed as king at Gulating

Gulating ( non, Gulaþing) was one of the first Norwegian legislative assemblies, or '' things,'' and also the name of a present-day law court of western Norway. The practice of periodic regional assemblies predates recorded history, and was fi ...

in Bergen, and at Haugating

Haugating was a Thing in medieval Norway. Haugating served as an assembly for the regions around Vestfold and the area west of Oslofjord. It was located at Tønsberg in Vestfold, Norway.

Background

Although it was not as recognized national ...

, Borgarting

The Borgarting was one of the major popular assemblies or things (''lagting'') of medieval Norway. Historically, it was the site of the court and assembly for the southern coastal region of Norway from the south-eastern border with Sweden, westwar ...

and local things east of Elven (Göta Älv). While Skule's supporters initially had attempted to cast doubt about Haakon's royal ancestry, they eventually suspended open resistance to his candidacy. As the dispute could have threatened to split the birkebeiners in two, Skule settled on becoming regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

for Haakon during his minority.

In connection with the dispute over the royal election, Haakon's mother Inga had to prove his parentage through a trial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal was an ancient judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused was determined by subjecting them to a painful, or at least an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience.

In medieval Europe, like trial by combat, tri ...

in Bergen in 1218. The result of the trial strengthened the legal basis for his kingship, and improved his relationship with the church.Helle, 1995, p. 76. The saga's claim that Haakon already had been generally accepted as king in 1217/18 has however been contested by modern historians such as Sverre Bagge

Sverre Håkon Bagge (born 7 August 1942 in Bergen) is a Norwegian historian.

He took his doctorate with the thesis ''Den politiske ideologi i Kongespeilet'', published in 1979. From 1974 to 1991 he worked as an associate professor (''førsteamanue ...

. Skule and Haakon increasingly drifted apart in their administration, and Skule focused mainly on governing Eastern Norway after 1220, which he had gained the right to rule in 1218 as his third of the Norwegian kingdom. From 1221 to 1223, Haakon and Skule separately issued letters as rulers of Norway, and maintained official contacts abroad. In 1223 a great meeting of bishops, clergy, secular nobles and other high-ranking figures from all across the country was held in Bergen to finally decide on Haakon's right to the throne. Other candidates to the throne were present either personally or through attorneys, but Haakon was in the end unanimously confirmed as King of Norway by the court.

The last bagler king Philip Simonsson died in 1217. Speedy political and military manoeuvering by Skule led to a reconciliation between the birkebeiner and bagler, and thus the reunification of the kingdom. However, some discontented elements among the bagler found a new royal pretender, Sigurd Ribbung

Sigurd Erlingsson Ribbung (old Norse language, Old Norse: ''Sigurðr ribbungr'') (died 1226) was a Norwegian nobleman and pretender to the throne of Norway during the civil war era in Norway.

Biography

Sigurd Erlingsson's father was Erling Steinve ...

, and launched a new rising from 1219. The rising only gained support in parts of Eastern Norway, and were unable to gain control of Viken

Viken may refer to:

*Viken, Scandinavia, a historical region

*Viken (county), a Norwegian county established in 2020

*Viken, Sweden, a bimunicipal locality in Skåne County, Sweden

*Viken (lake), a lake in Sweden, part of the part of the Göta cana ...

and Oppland

Oppland is a former county in Norway which existed from 1781 until its dissolution on 1 January 2020. The old Oppland county bordered the counties of Trøndelag, Møre og Romsdal, Sogn og Fjordane, Buskerud, Akershus, Oslo and Hedmark. The co ...

ene as the bagler formerly had done. In the summer of 1223 Skule eventually managed to force the Ribbungar to surrender. The great meeting in Bergen soon after however renewed the division of the Norwegian kingdom with Skule, who thereafter gained control of the northern third of the country instead of the east, in what marked a setback despite his military victory. In 1224, Ribbung who had been in Skule's custody escaped, and Haakon was left to fight him alone as the new ruler of Eastern Norway. Skule remained passive throughout the rest of the war, and his support for Haakon was lukewarm at best.Bagge, 1996, pp. 108–109. Assuming the military lead in the fight, Haakon nevertheless defeated Ribbung through comprehensive and organisationally demanding warfare over the next years. As part of the campaign, Haakon additionally led a large army into Värmland

Värmland () also known as Wermeland, is a '' landskap'' (historical province) in west-central Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland, and Närke, and is bounded by Norway in the west. Latin name versions are ''Va ...

, Sweden in 1225 in order to punish the inhabitants for their support of Ribbung. While Ribbung died in 1226, the revolt was finally quashed in 1227 after the surrender of the last leader of the uprising, Haakon the Crazy's son Knut Haakonsson. This left Haakon more or less uncontested monarch.Helle, 1995, p. 77.

Haakon's councillors had sought to reconcile Haakon and Skule by proposing marriage between Haakon and Skule's daughter

Haakon's councillors had sought to reconcile Haakon and Skule by proposing marriage between Haakon and Skule's daughter Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

in 1219. Haakon accepted the proposal (although he did not think it would change much politically), but the marriage between Haakon and Margrete did not take place before 1225, partly due to the conflict with Ribbung. The relationship between Haakon and Skule nevertheless deteriorated further during the 1230s, and attempts of settlements at meetings in 1233 and 1236 only distanced them more from each other. Periodically, the two nonetheless reconciled and spent a great amount of time together, only to have their friendship destroyed, according to the saga by intrigues derived from rumours and slander by men who played the two against each other. Skule was the first person ever in Norway to be titled duke (''hertug'') in 1237, but instead of control over a region gained the rights to the incomes from a third of the '' syssels'' scattered across the whole of Norway. This was part of an attempt by Haakon to limit Skule's power. In 1239 the conflict between the two erupted into open warfare when Skule had himself proclaimed king. Although he had some support in Trøndelag, Opplandene and in eastern Viken, he could not stand up to Haakon's forces.Helle, 1995, p. 180. The rebellion ended when Skule was killed in 1240, leaving Haakon the undisputed king of Norway. This revolt is generally taken to mark the final end of Norway's civil war era.

Recognition by the Pope

While the church in Norway initially had refused to recognise Haakon as King of Norway, it had largely turned to support his claim to the throne by the 1223 meeting, although later disagreements occurred. Despite additionally having become the undisputed ruler of Norway after 1240, Haakon had still not been approved as king by thepope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

due to his illegitimate birth. He nonetheless had a strong personal desire to be approved fully as a European king. Several papal commissions were appointed to investigate the matter, and Haakon declared his legitimate son Haakon the Young his successor instead of an older living illegitimate son. Although Haakon had children with his mistress Kanga the Young prior to his marriage with Margrete, it was his children with Margrete who were designated as his successors in accordance with a papal recognition. The Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

principle of legitimacy

Legitimacy, from the Latin ''legitimare'' meaning "to make lawful", may refer to:

* Legitimacy (criminal law)

* Legitimacy (family law)

* Legitimacy (political)

See also

* Bastard (law of England and Wales)

* Illegitimacy in fiction

* Legit (d ...

was thus established in the Norwegian order of succession, although Haakon's new law still maintained that illegitimate children could be designated as successor in the absence of any legitimate children or grandchildren—contrary to Catholic principles. While his strong position allowed him to set boundaries to the church's political influence, he was on the other hand prepared to give the church much autonomy in internal affairs and relations with the rural society.

Haakon also attempted to strengthen his ties with the papacy by taking a vow to go on crusade. In 1241 he converted this into a vow of waging war against pagan peoples in the north in light of the Mongol invasion of Europe

From the 1220s into the 1240s, the Mongols conquered the Turkic states of Volga Bulgaria, Cumania, Alania, and the Kievan Rus' federation. Following this, they began their invasion into heartland Europe by launching a two-pronged invasion of ...

. When a group of Karelians

Karelians ( krl, karjalaižet, karjalazet, karjalaiset, Finnish: , sv, kareler, karelare, russian: Карелы) are a Finnic ethnic group who are indigenous to the historical region of Karelia, which is today split between Finland and Russi ...

("Bjarmians") had been forced westwards by the Mongols, Haakon allowed them to stay in Malangen

Malangen ( sme, Málatvuotna or fkv, Malankivuono) is a former municipality in Troms county in Norway. The municipality existed from 1871 until its dissolution in 1964. The old municipality surrounded the Malangen fjord and today that area ...

and had them Christianized—something that would please the papacy. Later, in 1248, Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

proposed (by Matthew Paris as messenger) to Haakon to join him for a crusade, with Haakon as commander of the fleet, but Haakon declined.Helle, 1995, p. 199. While Haakon had been unsuccessful in gaining the recognition of Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

, he quickly gained the support from Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

who sought alliances in his struggle with Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Frederick II. Haakon finally achieved royal recognition by Pope Innocent in 1246, and Cardinal William of Sabina

William of Modena ( – 31 March 1251), also known as ''William of Sabina'', ''Guglielmo de Chartreaux'', ''Guglielmo de Savoy'', ''Guillelmus'', was an Italian clergyman and papal diplomat.

was sent to Bergen and crowned Haakon in 1247.

Cultural influence and legal reforms

gyrfalcon

The gyrfalcon ( or ) (), the largest of the falcon species, is a bird of prey. The abbreviation gyr is also used. It breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, and the islands of northern North America and the Eurosiberian region. It is mainly a reside ...

s with an embassy to the sultan of Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

.

The royal court in Bergen also started importing and translating the first true European literature that became available to a wider Norwegian audience. The literature which was popular then was heroic-romantic literature derived from the French and in turn English courts, notably ''chansons de geste

The ''chanson de geste'' (, from Latin 'deeds, actions accomplished') is a medieval narrative, a type of epic poem that appears at the dawn of French literature. The earliest known poems of this genre date from the late 11th and early 12th cen ...

'' around Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

(the Matter of France

The Matter of France, also known as the Carolingian cycle, is a body of literature and legendary material associated with the history of France, in particular involving Charlemagne and his associates. The cycle springs from the Old French '' chan ...

) and tales of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

(the Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the list of legendary kings of Britain, legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It ...

). The first work that was translated into Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

was reportedly the Arthurian romantic story ''Tristan and Iseult

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval chivalric romance told in numerous variations since the 12th century. Based on a Celtic legend and possibly other sources, the tale is a tragedy about the illic ...

'', which was finished in 1226 after orders from the young and newly-wed Haakon. Hákon's programme seems to have been the spark for the emergence of a new Norse genre of chivalric sagas

The ''riddarasögur'' (literally 'sagas of knights', also known in English as 'chivalric sagas', 'romance-sagas', 'knights' sagas', 'sagas of chivalry') are Norse prose sagas of the romance genre. Starting in the thirteenth century with Norse tr ...

.Helle, 1995, pp. 171–172.

Haakon also had the popular religious text ''Visio Tnugdali

The ''Visio Tnugdali'' ("Vision of Tnugdalus") is a 12th-century religious text reporting the otherworldly vision of the Irish knight Tnugdalus (later also called "Tundalus", "Tondolus" or in English translations, "Tundale", all deriving from the ...

'' translated into Old Norse as ''Duggals leiðsla''. The literature also appealed to women, and both Haakon's wife Margrete and his daughter Kristina owned richly illustrated psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the emergence of the book of hours in the Late Middle Ages, psalters we ...

s.

Haakon also initiated legal reforms which were crucial for the development of justice in Norway. Haakon's "New Law" written around 1260 was a breakthrough for both the idea and practice of public justice, as opposed to the traditional Norwegian customs for feuds and revenge. The influence of the reforms is also apparent in Haakon's '' King's Mirror'' (''Konungs skuggsjá''), an educational text intended for his son Magnus, which was probably written in cooperation with the royal court in the mid-1250s.

Involvements abroad

Relations were hostile with both Sweden and Denmark from the start. During his rivalry with Earl Skule, Skule attempted to gain the support ofValdemar II of Denmark

Valdemar (28 June 1170 – 28 March 1241), later remembered as Valdemar the Victorious (), was the King of Denmark (being Valdemar II) from 1202 until his death in 1241.

Background

He was the second son of King Valdemar I of Denmark and Sophi ...

, but any aid was made impossible after Valdemar's capture by one of his vassals. Since the Danes wanted overlordship of Norway and supported the Guelphs

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalr ...

(those supporting the Pope over the Holy Roman Emperor), Haakon in turn sought closer ties with the Ghibelline Emperor Frederick II, who sent ambassadors to Norway. As Haakon had gained a powerful reputation due to the strength of his fleet, other European rulers wanted to benefit from his friendship. Despite the struggle between the Pope and the Emperor, Haakon was able to maintain friendships with both. According to an English chronicler, the Pope wanted Haakon to become Holy Roman Emperor. It has been suggested that Haakon hesitated to leave Norway due to the Mongol threat.

Haakon pursued a foreign policy that was active in all directions (although foremost to the west and south-east). In the north-east, the relationship with Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ol ...

had been tense due to a dispute over the right to tax the Sami people

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise net ...

, as well as raiding from both Norwegian and Karelian sides. Eventually, the Mongol invasion of Rus'

The Mongol Empire invaded and conquered Kievan Rus' in the 13th century, destroying numerous southern cities, including the largest cities, Kiev (50,000 inhabitants) and Chernihiv (30,000 inhabitants), with the only major cities escaping destr ...

drove Prince Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Yaroslavich Nevsky (russian: Александр Ярославич Невский; ; 13 May 1221 – 14 November 1263) served as Prince of Novgorod (1236–40, 1241–56 and 1258–1259), Grand Prince of Kiev (1236–52) and Grand P ...

to negotiations with Haakon that likely strengthened Norwegian control of Troms

Troms (; se, Romsa; fkv, Tromssa; fi, Tromssa) is a former county in northern Norway. On 1 January 2020 it was merged with the neighboring Finnmark county to create the new Troms og Finnmark county. This merger is expected to be reversed by t ...

and Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbouri ...

.Helle, 1995, p. 198. An embassy from Novgorod one time asked for the hand of Haakon's daughter Christina, but Haakon refused due to the Mongol threat. Due to the Elven-based Norwegian presence in the seas around the south of Sweden and into the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, Norway increasingly relied on Baltic grain from Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

. The import was however halted in the late 1240s due to the plundering of Norwegian ships in Danish seas by ships from Lübeck. In 1250, Haakon made a peace and trade agreement with Lübeck, which eventually also opened the city of Bergen to the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

.Helle, 1995, p. 197. During the conflict, Haakon had reportedly been offered control over the city by Emperor Frederick II.Helle, 1995, p. 198. In any case, Haakon's policy regarding Northern German ports largely derived from his strategy of attempting to exploit the internal turmoil that had erupted in Denmark following the death of King Valdemar II in 1241.

In Scandinavia, Haakon regularly met with neighbouring rulers in the border-area around Elven from the late 1240s through the 1250s. Using grand fleets as envoys, Haakon's fleet at most reportedly counted over 300 ships. Haakon had also reconciled with the Swedes when he had his son Haakon the Young marry Rikissa, a daughter of Earl Birger. Haakon sought to expand his kingdom southwards of Elven into the Danish province of Halland

Halland () is one of the traditional provinces of Sweden (''landskap''), on the western coast of Götaland, southern Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Småland, Scania and the sea of Kattegat. Until 1645 and the Second Treaty of Brömsebro ...

. He thus looked for alliance with the Swedes, as well as ties with opponents of the ruling line of monarchs of Denmark. Haakon made a deal with Swedish leader Earl Birger in 1249 about a joint Swedish-Norwegian invasion into Halland and Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conte ...

, but the agreement was eventually abandoned by the Swedes (''see'' Treaty of Lödöse). Haakon claimed Halland in 1253, and finally invaded the province on his own in 1256, demanding it as compensation for the looting of Norwegian ships in Danish seas. He was however forced to renounce his claims in 1257 after a peace agreement was made with Christopher I of Denmark

Christopher I ( da, Christoffer I) (1219 – 29 May 1259) was King of Denmark between 1252 and 1259. He was the son of Valdemar II of Denmark by his second wife, Berengaria of Portugal. He succeeded his brothers Eric IV Plovpenning and Abel of D ...

. Haakon thereafter negotiated a marriage between his only remaining son, Magnus, and Christopher's niece Ingeborg

Ingeborg is a Germanic feminine given name, mostly used in Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, derived from Old Norse ''Ingiborg, Ingibjǫrg'', combining the theonym ''Ing'' with the element ''borg'' "stronghold, protection". Ingebjørg is the No ...

. Haakon's Nordic policies initiated the build-up to the later personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

s (called the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish language, Danish, Norwegian language, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under ...

), that in the end had dire consequences for Norway as it did not have the economic and military resources to persevere and maintain Haakon's aggressive policies.

More distantly, Haakon sought an alliance with Alfonso X of Castile

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Germ ...

, a potential next Holy Roman emperor—chiefly as it would guarantee new supplies of grain in light of rising prices in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, and possibly giving access to Baltic grain through Norwegian control of Lübeck. Alfonso in turn sought to expand his influence in Northern Europe, as well as to gain Norwegian naval assistance for the campaign or crusade he had proposed in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

(seeing that the Iberian Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

received backing overseas from North Africa). Haakon could thus potentially also fulfill his papal vow of crusade, although he likely did not intend to.O'Callaghan, 2011, p. 17. He sent an embassy to Castile in 1255, and the accompanying Castilian ambassador on the return to Norway proposed to establish the "strongest ties of friendship" with Haakon. At the request of Alfonso, Haakon sent his daughter Christina to Castile to marry one of Alfonso's brothers. Christina's death four years after the childless marriage, however, marked an effective end of the short-lived alliance,O'Callaghan, 1993, p. 203. and the proposed crusade fell into the blue.

The Scottish expedition and death

Haakon employed an active and aggressive foreign policy towards strengthening Norwegian ties in the west.Helle, 1995, p. 194. His policy relied on friendship and trade with the English king; the first known Norwegian trade agreements were made with England in the years 1217–23 (England's first commercial treaties were also made with Norway), and the friendship with

Haakon employed an active and aggressive foreign policy towards strengthening Norwegian ties in the west.Helle, 1995, p. 194. His policy relied on friendship and trade with the English king; the first known Norwegian trade agreements were made with England in the years 1217–23 (England's first commercial treaties were also made with Norway), and the friendship with Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

was a cornerstone in Haakon's foreign policy.Orfield & Boyer, 2002, p. 137. As they had become kings around the same time, Haakon wrote to Henry in 1224 that he wished they could maintain the friendship that had existed between their fathers. Haakon sought to defend the Norwegian sovereignty over the islands in the west, namely the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

and Man

A man is an adult male human. Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent). Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromo ...

(under the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles consisted of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Firth of Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the , or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the or Nort ...

), Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

and Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

(under the Earldom of Orkney

The Earldom of Orkney is the official status of the Orkney, Orkney Islands. It was originally a Norsemen, Norse Feudalism, feudal dignity in Scotland which had its origins from the Viking period. In the ninth and tenth centuries it covered mor ...

), and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

. Further, the Norse community in Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

agreed to submit to the Norwegian king in 1261, and in 1262 Haakon achieved one of his long-standing ambitions when he managed to incorporate Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

into his kingdom by utilising the island's internal conflicts in his favour. The dependency on Norwegian maritime trade and their subordination to the Nidaros ecclesiastical province were some of the key reasons which allowed Haakon to assert sovereignty over the islands. The Norwegian kingdom was at the largest it has ever been by the end of Haakon's reign.

Norwegian control over the Faroe Islands and Shetland was strong due to the importance of Bergen as a trading centre, while Orkney, the Hebrides and Man had more natural ties with the Scottish mainland. Although traditionally having had ties with the community of Norse settlers in northern Scotland, Scottish rulers had increasingly asserted their sovereignty over the entire mainland. Haakon had at the same time gained stronger control of the Hebrides and Man than any Norwegian ruler since Magnus Barefoot

Magnus Olafsson (Old Norse: ''Magnús Óláfsson'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Olavsson''; 1073 – 24 August 1103), better known as Magnus Barefoot (Old Norse: ''Magnús berfœttr'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Berrføtt''), was King of Norway (being Ma ...

.Helle, 1995, p. 196. As part of a new development the Scottish king Alexander II claimed the Hebrides and requested to buy the islands from Norway, but Haakon staunchly rejected the proposals. Following Alexander II's death, his son Alexander III continued and stepped up his father's policy by sending an embassy to Norway in 1261, and thereafter attacking the Hebrides.

In 1263 the dispute with the Scottish king over the Hebrides induced Haakon to undertake an expedition to the islands. Having learned in 1262 that Scottish nobles had raided the Hebrides and that Alexander III planned to conquer the islands, Haakon went on an expedition with his formidable ''leidang The institution known as ''leiðangr'' (Old Norse), ''leidang'' (Norwegian), ''leding'' (Danish), ''ledung'' (Swedish), ''expeditio'' (Latin) or sometimes lething (English), was a form of conscription ( mass levy) to organize coastal fleets for seas ...

'' fleet of at least 120 ships in 1263, having become accustomed to negotiating backed by an intimidating fleet. The fleet left Bergen in July, and reached Shetland and Orkney in August where they were joined by chieftains from the Hebrides and Man. Negotiations were started by Alexander following Norwegian landings on the Scottish mainland, but were purposely prolonged by the Scots. Having waited until September/October for weather that caused trouble for Haakon's fleet, a clash occurred between a smaller Norwegian force and a Scottish division at the Battle of Largs

The Battle of Largs (2 October 1263) was a battle between the kingdoms of Norway and Scotland, on the Firth of Clyde near Largs, Scotland. Through it, Scotland achieved the end of 500 years of Norse Viking depredations and invasions despite bei ...

. Although inconclusive and of a limited impact, Haakon withdrew to Orkney for the winter. A delegation of Irish kings invited Haakon to become the High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ga, Ardrí na hÉireann ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and later sometimes assigned ana ...

and expel the Anglo-Norman settlers in Ireland, but this was apparently rejected against Haakon's wish.

Haakon over-wintered at the Bishop's Palace in Kirkwall

Kirkwall ( sco, Kirkwaa, gd, Bàgh na h-Eaglaise, nrn, Kirkavå) is the largest town in Orkney, an archipelago to the north of mainland Scotland.

The name Kirkwall comes from the Norse name (''Church Bay''), which later changed to ''Kirkv ...

, Orkney, with plans to resume his campaign the next year.Forte, Oram & Pedersen, 2005, p. 262. During his stay in Kirkwall he however fell ill, and died in the early hours of 16 December 1263. Haakon was buried in the St Magnus Cathedral

St Magnus Cathedral dominates the skyline of Kirkwall, the main town of Orkney, a group of islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. It is the most northerly cathedral in the United Kingdom, a fine example of Romanesque architecture built ...

in Kirkwall for the winter, and when spring came he was exhumed and his body taken back to Norway, where he was buried in the Old Cathedral in his capital Bergen. Centuries later, in 1531, the cathedral was demolished by the commander of Bergenhus

Bergenhus is a borough of the city of Bergen in Vestland county, Norway. This borough encompasses the city centre and is the most urbanized area of the whole city. The borough has a population (2014) of 40,606. This gives Bergenhus a popula ...

, Eske Bille

Eske Bille (born ca. 1480, died 9 February 1552) was a Danish diplomat and statesman Biography

In 1510, he was made governor and commander at Copenhagen Castle. In 1514 he was transferred to Hagenskov on Funen.

He served as Commander of Bergenhu ...

, for military purposes in connection with the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, and the graves of Haakon and other Norwegian kings buried there might have been destroyed in the process or moved to another location.

Evaluation

Norwegian historians have held differing views on Haakon's reign. In the 19th century,P. A. Munch

Peter Andreas Munch (15 December 1810 – 25 May 1863), usually known as P. A. Munch, was a Norwegian historian, known for his work on the medieval history of Norway. Munch's scholarship included Norwegian archaeology, geography, ethnograph ...

portrayed Haakon as a mighty, almost flawless ruler, which in turn influenced Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

in his 1863 play ''The Pretenders

Pretenders are an English–American rock band formed in March 1978. The original band consisted of founder and main songwriter Chrissie Hynde (lead vocals, rhythm guitar), James Honeyman-Scott (lead guitar, backing vocals, keyboards), Pete Fa ...

''. In the early 20th century, poet Hans E. Kinck

Hans Ernst Kinck (; 11 October 1865 – 13 October 1926) was a Norwegian author and philologist who wrote novels, short stories, dramas, and essays. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature seven times.

Life

Kinck was born in Øksfjo ...

countered and viewed Haakon as an insignificant king subordinated to forces outside of his control, a view which influenced historians such as Halvdan Koht

Halvdan Koht (7 July 1873 – 12 December 1965) was a Norwegian historian and politician representing the Labour Party.

Born in the north of Norway to a fairly distinguished family, he soon became interested in politics and history. Star ...

and Edvard Bull, Sr.

Edvard Bull (4 December 1881 – 26 August 1932) was a Norwegian historian and politician for the Labour Party. He took the doctorate in 1912 and became a professor at the University of Kristiania in 1917, and is known for writings on a broad r ...

Haakon has often been compared with Skule Bårdsson, and historians have taken sides in the old conflict. While Munch saw Skule as a traitor to the rightful Norwegian king, Koht viewed Skule as a heroic figure. On more sketchy grounds, Kinck praised Skule as representing the original and dying Norse culture, and Haakon as a superficial emulator of foreign culture. Since the 1960s, historians including Narve Bjørgo

Narve Bjørgo (born 3 May 1936 in Meland, Nordhordland) is a Norwegian historian.

He was born in Meland. He graduated from the University of Bergen in 1964, and worked as a research assistant until 1970. Then, for two years, he was a research fel ...

, Per Sveaas Andersen, Knut Helle

Knut Helle (19 December 1930 – 27 June 2015) was a Norwegian historian. A professor at the University of Bergen from 1973 to 2000, he specialized in the late medieval history of Norway. He has contributed to several large works.

Early life, ed ...

, Svein Haga and Kåre Lunden

Kåre Lunden (8 April 1930 – 18 July 2013) was a Norwegian historian, and Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Oslo.

Lunden was born in Naustdal. He originally studied agronomy at the Norwegian College of Agriculture, graduating i ...

have in turn professed a reaction against Koht's view. According to Sverre Bagge, modern historians tend to follow Koht when it comes to see Skule's rebellion as a last desperate attempt to stop Haakon from encroaching his power, but lean closer to Munch's overall evaluation of the two men.

Knut Helle interprets the saga to leave an impression of Skule as a skilled warrior and politician, while noting that the author of the saga purposely created a diffuse image of his role in the conflict with Haakon. On the other hand, Helle notes that Skule was outmaneuvered with relative ease by Haakon's supporters in the years immediately after 1217, and that this may suggest some limited abilities. While neither giving a clear picture of Haakon, Helle maintains that Haakon "obviously" learned to master the political game in his early years. He interprets Haakon as an independent and willstrong ruler whom he assigns a "significant personal responsibility" for the policies pursued during his reign—notably regarding the internal consolidation of the kingship, the orientation towards European culture and the aggressive foreign policy.Helle, 1995, p. 181. In his article in ''Norsk biografisk leksikon

is the largest Norwegian biographical encyclopedia.

The first edition (NBL1) was issued between 1921 and 1983, including 19 volumes and 5,100 articles. It was published by Aschehoug with economic support from the state.

bought the rights to ...

'', Knut Helle acknowledges that Haakon was empowered by the strong institutional position of the kingship at the end of his reign (which he had developed himself), and that his policies were not always successful. It nonetheless recognises the substantial political abilities and powerful determination Haakon must have had in order to progress from the difficult position in which he started his reign.

Children and marriage

Haakon had three illegitimate children with his mistress Kanga the Younger av Folkindberg (who is only known by name) (1198–1225), before 1225. They were:Keyser, 1870, p. 230.

* Sigurd (died 1252).

* Cecilia (died 1248). Married ''

Haakon had three illegitimate children with his mistress Kanga the Younger av Folkindberg (who is only known by name) (1198–1225), before 1225. They were:Keyser, 1870, p. 230.

* Sigurd (died 1252).

* Cecilia (died 1248). Married ''lendmann

Lendmann (plural lendmenn; non, lendr maðr) was a title in medieval Norway. Lendmann was the highest rank attainable in the hird of the Norwegian king, and a lendmann stood beneath only earls and kings. In the 13th century there were between 1 ...

'' Gregorius Andresson, a nephew of the last bagler king Philip Simonsson in 1241. Widowed in 1246, she married Harald Olafsson

Harald or Haraldr is the Old Norse form of the given name Harold. It may refer to:

Medieval Kings of Denmark

* Harald Bluetooth (935–985/986)

Kings of Norway

* Harald Fairhair (c. 850–c. 933)

* Harald Greycloak (died 970)

* Harald Hardrad ...

, King of Mann and the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles consisted of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Firth of Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries AD. The islands were known to the Norse as the , or "Southern Isles" as distinct from the or Nort ...

in 1248. They both drowned the same year on the return voyage to Great Britain.Orfield & Boyer, 2002, p. 138.

* Kone (c. 1225 -), married Toralde Gunnarsson Hvite, until Gulsvik (Buskerud, c. 1220 – Gulsvik, Flå, Buskerud, d. 1260), mentioned on a 1258 document, and had issue

Haakon married Margrete Skulesdatter on 25 May 1225, daughter of his rival Earl Skule Bårdsson

Skule Bårdsson or Duke Skule ( Norwegian: Hertug Skule) (Old Norse: Skúli Bárðarson) ( – 24 May 1240) was a Norwegian nobleman and claimant to the royal throne against his son-in-law, King Haakon Haakonsson. Henrik Ibsen's play '' Kongs ...

. Their children were:

# Olav (born 1226). Died in infancy.

# Haakon the Young

Haakon Haakonsson the Young (Norwegian: ''Håkon Håkonsson Unge'', Old Norse: ''Hákon Hákonarson hinn ungi'') (10 November 1232 – 5 May 1257) was the son of king Haakon Haakonsson of Norway, and held the title of king, subordinate to his fa ...

(1232–1257). Married Rikissa Birgersdotter

Rikissa Birgersdotter, also known as ''Rixa'', ''Richeza'', ''Richilda'' and ''Regitze'', ( 1237 – after 1288) was Queen of Norway as the wife of the co-king Haakon Haakonson, and later Princess of Werle as wife of Henry I, Prince of Mecklenbu ...

, daughter of the Swedish statesman Earl Birger in 1251. He was appointed king and co-ruler by his father in 1240, but predeceased his father.

# Christina (1234–1262). Married Infante Philip of Castile

Philip of Castile ( es, Felipe de Castilla y Suabia; 1231 – 28 November 1274) was an Infante of Castile and son of Ferdinand III, King of Castile and León, and his first queen, Beatrice of Swabia. He was Lord of Valdecorneja, and, according ...

, brother of Alfonso X of Castile in 1258. She died childless.

# Magnus VI of Norway

Magnus Haakonsson ( non, Magnús Hákonarson, no, Magnus Håkonsson, label=Modern Norwegian; 1 (or 3) May 1238 – 9 May 1280) was King of Norway (as Magnus VI) from 1263 to 1280 (junior king from 1257). One of his greatest achievements was the m ...

(1238–1280). Married Ingeborg, daughter of Eric IV of Denmark in 1261. Was appointed king and co-ruler following the death of Haakon the Young. Succeeded his father as King of Norway following his father's death.

Popular culture

Håkon and Kristin

Haakon, also spelled Håkon (in Norway), Hakon (in Denmark), Håkan (in Sweden),Oxford Dictionary of First Names Patrick Hanks, Kate Hardcastle, Flavia Hodges - 2006 "Håkon Norwegian: from the Old Norse personal name Hákon or Háukon, from hā ...

were the mascots of the 1994 Winter Olympics

The 1994 Winter Olympics, officially known as the XVII Olympic Winter Games ( no, De 17. olympiske vinterleker; nn, Dei 17. olympiske vinterleikane) and commonly known as Lillehammer '94, was an international winter multi-sport event held fro ...

. Håkon is named after Haakon IV of Norway and Kristin after Christina of Norway

Christina Sverresdatter (Norwegian: ''Kristin Sverresdatter''; died 1213) was a medieval Norwegian princess and titular queen consort, spouse of co-regent Philip Simonsson, the Bagler party pretender to the throne of Norway.

Biography

Christi ...

.Les mascottes des Jeux Olympiques d’hiver d’Innsbruck 1976 à Sotchi 2014Olympic.org In ''

The Last King

''The Last King'' ( no, Birkebeinerne) is a 2016 Norwegian historical drama, directed by Nils Gaup. The story, inspired by true events, centers on the efforts of the Birkebeiner loyalists to protect the infant, Haakon Haakonsson, the heir to t ...

'' (2016), the infant Håkon IV is portrayed by Jonathan Oskar Dahlgren.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Haakon 04 Of Norway 1204 births 1263 deaths 13th-century Norwegian monarchs Norwegian Roman Catholics Roman Catholic monarchs Fairhair dynasty Norwegian civil wars Medieval child rulers Burials at St Magnus Cathedral Burials at Christ Church, Bergen People from Østfold People from Eidsberg House of Sverre People educated at the Bergen Cathedral School People educated at the Trondheim Cathedral School