HIV virus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''

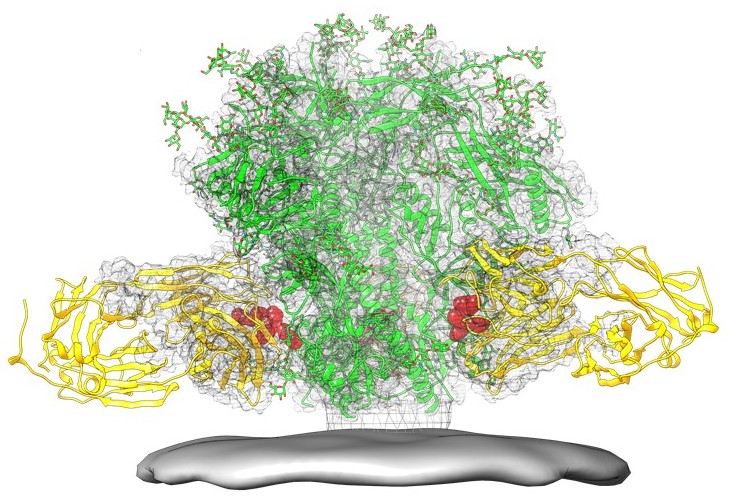

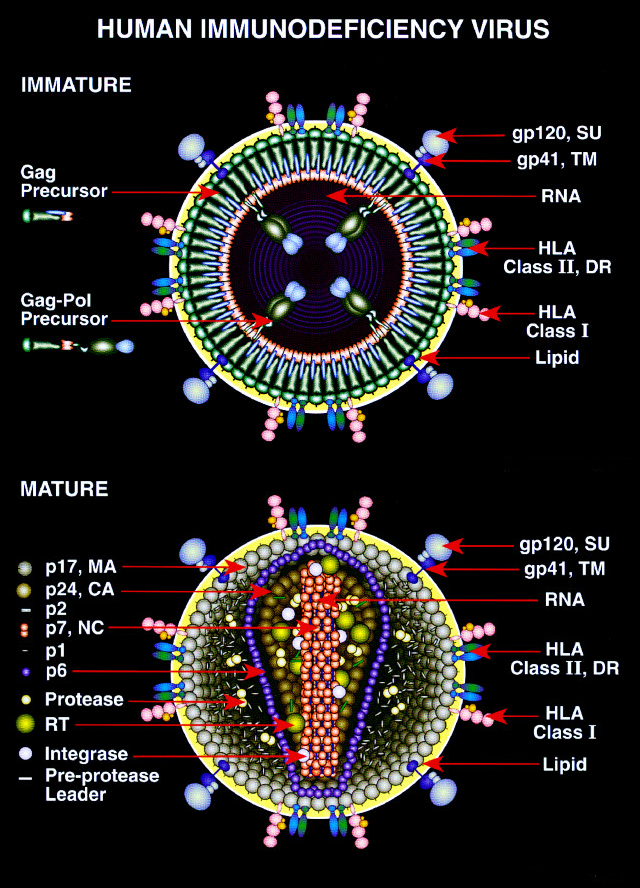

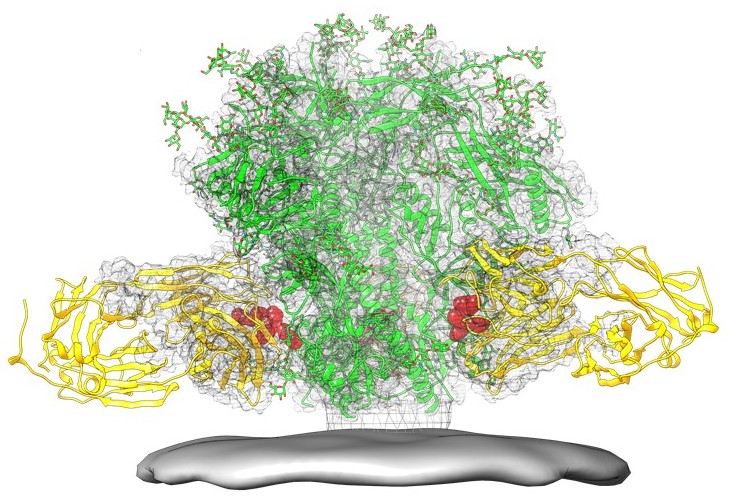

HIV is similar in structure to other retroviruses. It is roughly spherical with a diameter of about 120 nm, around 100,000 times smaller in volume than a

HIV is similar in structure to other retroviruses. It is roughly spherical with a diameter of about 120 nm, around 100,000 times smaller in volume than a  As the sole viral protein on the surface of the virus, the envelope protein is a major target for

As the sole viral protein on the surface of the virus, the envelope protein is a major target for  The RNA genome consists of at least seven structural landmarks ( LTR,

The RNA genome consists of at least seven structural landmarks ( LTR,

The term viral tropism refers to the cell types a virus infects. HIV can infect a variety of immune cells such as CD4+ T cells,

The term viral tropism refers to the cell types a virus infects. HIV can infect a variety of immune cells such as CD4+ T cells,

The HIV virion enters

The HIV virion enters  HIV-1 entry, as well as entry of many other retroviruses, has long been believed to occur exclusively at the plasma membrane. More recently, however, productive infection by pH-independent,

HIV-1 entry, as well as entry of many other retroviruses, has long been believed to occur exclusively at the plasma membrane. More recently, however, productive infection by pH-independent,

Shortly after the viral capsid enters the cell, an

Shortly after the viral capsid enters the cell, an

The final step of the viral cycle, assembly of new HIV-1 virions, begins at the

The final step of the viral cycle, assembly of new HIV-1 virions, begins at the

The classical process of infection of a cell by a virion can be called "cell-free spread" to distinguish it from a more recently recognized process called "cell-to-cell spread". In cell-free spread (see figure), virus particles bud from an infected T cell, enter the blood or

The classical process of infection of a cell by a virion can be called "cell-free spread" to distinguish it from a more recently recognized process called "cell-to-cell spread". In cell-free spread (see figure), virus particles bud from an infected T cell, enter the blood or

HIV differs from many viruses in that it has very high genetic variability. This diversity is a result of its fast replication cycle, with the generation of about 1010 virions every day, coupled with a high

HIV differs from many viruses in that it has very high genetic variability. This diversity is a result of its fast replication cycle, with the generation of about 1010 virions every day, coupled with a high

Many HIV-positive people are unaware that they are infected with the virus.

For example, in 2001 less than 1% of the sexually active urban population in Africa had been tested, and this proportion is even lower in rural populations. Furthermore, in 2001 only 0.5% of

Many HIV-positive people are unaware that they are infected with the virus.

For example, in 2001 less than 1% of the sexually active urban population in Africa had been tested, and this proportion is even lower in rural populations. Furthermore, in 2001 only 0.5% of

There is evidence that humans who participate in bushmeat activities, either as hunters or as bushmeat vendors, commonly acquire SIV. However, SIV is a weak virus, and it is typically suppressed by the human immune system within weeks of infection. It is thought that several transmissions of the virus from individual to individual in quick succession are necessary to allow it enough time to mutate into HIV. Furthermore, due to its relatively low person-to-person transmission rate, it can only spread throughout the population in the presence of one or more high-risk transmission channels, which are thought to have been absent in Africa prior to the 20th century.

Specific proposed high-risk transmission channels, allowing the virus to adapt to humans and spread throughout the society, depend on the proposed timing of the animal-to-human crossing. Genetic studies of the virus suggest that the most recent common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group dates back to circa 1910. Proponents of this dating link the HIV epidemic with the emergence of

There is evidence that humans who participate in bushmeat activities, either as hunters or as bushmeat vendors, commonly acquire SIV. However, SIV is a weak virus, and it is typically suppressed by the human immune system within weeks of infection. It is thought that several transmissions of the virus from individual to individual in quick succession are necessary to allow it enough time to mutate into HIV. Furthermore, due to its relatively low person-to-person transmission rate, it can only spread throughout the population in the presence of one or more high-risk transmission channels, which are thought to have been absent in Africa prior to the 20th century.

Specific proposed high-risk transmission channels, allowing the virus to adapt to humans and spread throughout the society, depend on the proposed timing of the animal-to-human crossing. Genetic studies of the virus suggest that the most recent common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group dates back to circa 1910. Proponents of this dating link the HIV epidemic with the emergence of

Lentivirus

''Lentivirus'' is a genus of retroviruses that cause chronic and deadly diseases characterized by long incubation periods, in humans and other mammalian species. The genus includes the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS. L ...

'' (a subgroup of retrovirus

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. Once inside the host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptas ...

) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ma ...

(AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

allows life-threatening opportunistic infection

An opportunistic infection is an infection caused by pathogens (bacteria, fungi, parasites or viruses) that take advantage of an opportunity not normally available. These opportunities can stem from a variety of sources, such as a weakened immun ...

s and cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

s to thrive. Without treatment, average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.

In most cases, HIV is a sexually transmitted infection

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and ora ...

and occurs by contact with or transfer of blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the cir ...

, pre-ejaculate, semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Sem ...

, and vaginal fluids. Non-sexual transmission can occur from an infected mother to her infant during pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops ( gestates) inside a woman's uterus (womb). A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Pregnancy usually occurs by sexual intercourse, but ...

, during childbirth

Childbirth, also known as labour and delivery, is the ending of pregnancy where one or more babies exits the internal environment of the mother via vaginal delivery or caesarean section. In 2019, there were about 140.11 million births glob ...

by exposure to her blood or vaginal fluid, and through breast milk

Breast milk (sometimes spelled as breastmilk) or mother's milk is milk produced by mammary glands located in the breast of a human female. Breast milk is the primary source of nutrition for newborns, containing fat, protein, carbohydrates ( la ...

. Within these bodily fluids, HIV is present as both free virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsk ...

particles and virus within infected immune cells

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mul ...

.

Research has shown (for both same-sex and opposite-sex couples) that HIV is untransmittable through condomless sexual intercourse if the HIV-positive partner has a consistently undetectable viral load

Viral load, also known as viral burden, is a numerical expression of the quantity of virus in a given volume of fluid, including biological and environmental specimens. It is not to be confused with viral titre or viral titer, which depends on the ...

.

HIV infects vital cells in the human immune system, such as helper T cells

The T helper cells (Th cells), also known as CD4+ cells or CD4-positive cells, are a type of T cell that play an important role in the adaptive immune system. They aid the activity of other immune cells by releasing cytokines. They are considere ...

(specifically CD4

In molecular biology, CD4 (cluster of differentiation 4) is a glycoprotein that serves as a co-receptor for the T-cell receptor (TCR). CD4 is found on the surface of immune cells such as T helper cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic ce ...

+ T cells), macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

s, and dendritic cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. Th ...

s. HIV infection leads to low levels of CD4+ T cells through a number of mechanisms, including pyroptosis Pyroptosis is a highly inflammatory form of lytic programmed cell death that occurs most frequently upon infection with intracellular pathogens and is likely to form part of the antimicrobial response. This process promotes the rapid clearance of va ...

of abortively infected T cells, apoptosis

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes ( morphology) and death. These changes in ...

of uninfected bystander cells, direct viral killing of infected cells, and killing of infected CD4+ T cells by CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes that recognize infected cells. When CD4+ T cell numbers decline below a critical level, cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity or cellular immunity is an immune response that does not involve antibodies. Rather, cell-mediated immunity is the activation of phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines ...

is lost, and the body becomes progressively more susceptible to opportunistic infections, leading to the development of AIDS.

Virology

Classification

HIV is a member of thegenus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Lentivirus

''Lentivirus'' is a genus of retroviruses that cause chronic and deadly diseases characterized by long incubation periods, in humans and other mammalian species. The genus includes the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS. L ...

'', part of the family ''Retroviridae

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. Once inside the host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase ...

''. Lentiviruses have many morphologies and biological

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary in ...

properties in common. Many species are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses with a long incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the in ...

. Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded

When referring to DNA transcription, the coding strand (or informational strand) is the DNA strand whose base sequence is identical to the base sequence of the RNA transcript produced (although with thymine replaced by uracil). It is this stra ...

, positive-sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system re ...

, enveloped RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid ( RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA virus ...

es. Upon entry into the target cell, the viral RNA genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

is converted (reverse transcribed) into double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded enzyme, reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genom ...

, that is transported along with the viral genome in the virus particle. The resulting viral DNA is then imported into the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

and integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded enzyme, integrase

Retroviral integrase (IN) is an enzyme produced by a retrovirus (such as HIV) that integrates—forms covalent links between—its genetic information into that of the host cell it infects. Retroviral INs are not to be confused with phage in ...

, and host co-factors. Once integrated, the virus may become latent

Latency or latent may refer to:

Science and technology

* Latent heat, energy released or absorbed, by a body or a thermodynamic system, during a constant-temperature process

* Latent variable, a variable that is not directly observed but inferred ...

, allowing the virus and its host cell to avoid detection by the immune system, for an indeterminate amount of time. The HIV virus can remain dormant in the human body for up to ten years after primary infection; during this period the virus does not cause symptoms. Alternatively, the integrated viral DNA may be transcribed, producing new RNA genomes and viral proteins, using host cell resources, that are packaged and released from the cell as new virus particles that will begin the replication cycle anew.

Two types of HIV have been characterized: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that was initially discovered and termed both lymphadenopathy associated virus (LAV) and human T-lymphotropic virus 3 (HTLV-III). HIV-1 is more virulent and more infective than HIV-2, and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. The lower infectivity of HIV-2, compared to HIV-1, implies that fewer of those exposed to HIV-2 will be infected per exposure. Due to its relatively poor capacity for transmission, HIV-2 is largely confined to West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

.

Structure and genome

red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "hol ...

.Compared with overview in: It is composed of two copies of positive-sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system re ...

single-stranded

When referring to DNA transcription, the coding strand (or informational strand) is the DNA strand whose base sequence is identical to the base sequence of the RNA transcript produced (although with thymine replaced by uracil). It is this stra ...

RNA that codes for the virus's nine gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s enclosed by a conical capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or ma ...

composed of 2,000 copies of the viral protein p24. The single-stranded RNA is tightly bound to nucleocapsid proteins, p7, and enzymes needed for the development of the virion such as reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genom ...

, protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s, ribonuclease

Ribonuclease (commonly abbreviated RNase) is a type of nuclease that catalyzes the degradation of RNA into smaller components. Ribonucleases can be divided into endoribonucleases and exoribonucleases, and comprise several sub-classes within the ...

and integrase

Retroviral integrase (IN) is an enzyme produced by a retrovirus (such as HIV) that integrates—forms covalent links between—its genetic information into that of the host cell it infects. Retroviral INs are not to be confused with phage in ...

. A matrix composed of the viral protein p17 surrounds the capsid ensuring the integrity of the virion particle.

This is, in turn, surrounded by the viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

, that is composed of the lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

taken from the membrane of a human host cell when the newly formed virus particle buds from the cell. The viral envelope contains proteins from the host cell and relatively few copies of the HIV envelope protein, which consists of a cap made of three molecules known as glycoprotein (gp) 120, and a stem consisting of three gp41 molecules that anchor the structure into the viral envelope. The envelope protein, encoded by the HIV ''env'' gene, allows the virus to attach to target cells and fuse the viral envelope with the target cell's membrane releasing the viral contents into the cell and initiating the infectious cycle.

As the sole viral protein on the surface of the virus, the envelope protein is a major target for

As the sole viral protein on the surface of the virus, the envelope protein is a major target for HIV vaccine

An HIV vaccine is a potential vaccine that could be either a preventive vaccine or a therapeutic vaccine, which means it would either protect individuals from being infected with HIV or treat HIV-infected individuals.

It is thought that an HIV ...

efforts. Over half of the mass of the trimeric envelope spike is N-linked glycan

The terms glycans and polysaccharides are defined by IUPAC as synonyms meaning "compounds consisting of a large number of monosaccharides linked glycosidically". However, in practice the term glycan may also be used to refer to the carbohydrate ...

s. The density is high as the glycans shield the underlying viral protein from neutralisation by antibodies. This is one of the most densely glycosylated molecules known and the density is sufficiently high to prevent the normal maturation process of glycans during biogenesis in the endoplasmic and Golgi apparatus. The majority of the glycans are therefore stalled as immature 'high-mannose' glycans not normally present on human glycoproteins that are secreted or present on a cell surface. The unusual processing and high density means that almost all broadly neutralising antibodies that have so far been identified (from a subset of patients that have been infected for many months to years) bind to, or are adapted to cope with, these envelope glycans.

The molecular structure of the viral spike has now been determined by X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

and cryogenic electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a cryomicroscopy technique applied on samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An aqueous sample so ...

. These advances in structural biology were made possible due to the development of stable recombinant forms of the viral spike by the introduction of an intersubunit disulphide bond

In biochemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) refers to a functional group with the structure . The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and is usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. I ...

and an isoleucine

Isoleucine (symbol Ile or I) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the depr ...

to proline

Proline (symbol Pro or P) is an organic acid classed as a proteinogenic amino acid (used in the biosynthesis of proteins), although it does not contain the amino group but is rather a secondary amine. The secondary amine nitrogen is in the p ...

mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, m ...

(radical replacement

A conservative replacement (also called a conservative mutation or a conservative substitution) is an amino acid replacement in a protein that changes a given amino acid to a different amino acid with similar biochemical properties (e.g. charge ...

of an amino acid) in gp41. The so-called SOSIP trimers not only reproduce the antigenic properties of the native viral spike, but also display the same degree of immature glycans as presented on the native virus. Recombinant trimeric viral spikes are promising vaccine candidates as they display less non-neutralising epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The epitope is the specific piece of the antigen to which an antibody binds. The p ...

s than recombinant monomeric gp120, which act to suppress the immune response to target epitopes.

The RNA genome consists of at least seven structural landmarks ( LTR,

The RNA genome consists of at least seven structural landmarks ( LTR, TAR

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bi ...

, RRE

The Royal Radar Establishment was a research centre in Malvern, Worcestershire in the United Kingdom. It was formed in 1953 as the Radar Research Establishment by the merger of the Air Ministry's Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) ...

, PE, SLIP, CRS, and INS), and nine genes (''gag'', ''pol'', and ''env'', ''tat'', ''rev'', ''nef'', ''vif'', ''vpr'', ''vpu'', and sometimes a tenth ''tev'', which is a fusion of ''tat'', ''env'' and ''rev''), encoding 19 proteins. Three of these genes, ''gag'', ''pol'', and ''env'', contain information needed to make the structural proteins for new virus particles. For example, ''env'' codes for a protein called gp160 that is cut in two by a cellular protease to form gp120 and gp41. The six remaining genes, ''tat'', ''rev'', ''nef'', ''vif'', ''vpr'', and ''vpu'' (or ''vpx'' in the case of HIV-2), are regulatory genes for proteins that control the ability of HIV to infect cells, produce new copies of virus (replicate), or cause disease.

The two '' tat'' proteins (p16 and p14) are transcriptional transactivators for the LTR promoter acting by binding the TAR RNA element. The TAR may also be processed into microRNA

MicroRNA (miRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21 to 23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals and some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. mi ...

s that regulate the apoptosis

Apoptosis (from grc, ἀπόπτωσις, apóptōsis, 'falling off') is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes ( morphology) and death. These changes in ...

genes ''ERCC1

DNA excision repair protein ERCC-1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''ERCC1'' gene. Together with ERCC4, ERCC1 forms the ERCC1-XPF enzyme complex that participates in DNA repair and DNA recombination.

Many aspects of these two gene ...

'' and '' IER3''. The ''rev'' protein (p19) is involved in shuttling RNAs from the nucleus and the cytoplasm by binding to the RRE

The Royal Radar Establishment was a research centre in Malvern, Worcestershire in the United Kingdom. It was formed in 1953 as the Radar Research Establishment by the merger of the Air Ministry's Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) ...

RNA element. The ''vif'' protein (p23) prevents the action of APOBEC3G

APOBEC3G (apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic subunit 3G) is a human enzyme encoded by the ''APOBEC3G'' gene that belongs to the APOBEC superfamily of proteins. This family of proteins has been suggested to play an important role in ...

(a cellular protein that deaminates cytidine

Cytidine (symbol C or Cyd) is a nucleoside molecule that is formed when cytosine is attached to a ribose ring (also known as a ribofuranose) via a β-N1- glycosidic bond. Cytidine is a component of RNA. It is a white water-soluble solid. which ...

to uridine

Uridine (symbol U or Urd) is a glycosylated pyrimidine analog containing uracil attached to a ribose ring (or more specifically, a ribofuranose) via a β-N1-glycosidic bond. The analog is one of the five standard nucleosides which make up nucle ...

in the single-stranded viral DNA and/or interferes with reverse transcription). The ''vpr

Vpr is a Human immunodeficiency virus gene and protein product.

Vpr stands for "Viral Protein R". Vpr, a 96 amino acid 14-kDa protein, plays an important role in regulating nuclear import of the HIV-1 pre-integration complex, and is required for ...

'' protein (p14) arrests cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there ...

at G2/M. The ''nef'' protein (p27) down-regulates CD4

In molecular biology, CD4 (cluster of differentiation 4) is a glycoprotein that serves as a co-receptor for the T-cell receptor (TCR). CD4 is found on the surface of immune cells such as T helper cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic ce ...

(the major viral receptor), as well as the MHC class I

MHC class I molecules are one of two primary classes of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (the other being MHC class II) and are found on the cell surface of all nucleated cells in the bodies of vertebrates. They also occur on p ...

and class II molecules.

''Nef'' also interacts with SH3 domain

The SRC Homology 3 Domain (or SH3 domain) is a small protein domain of about 60 amino acid residues. Initially, SH3 was described as a conserved sequence in the viral adaptor protein v-Crk. This domain is also present in the molecules of phos ...

s. The ''vpu'' protein (p16) influences the release of new virus particles from infected cells. The ends of each strand of HIV RNA contain an RNA sequence called a long terminal repeat

A long terminal repeat (LTR) is a pair of identical sequences of DNA, several hundred base pairs long, which occur in eukaryotic genomes on either end of a series of genes or pseudogenes that form a retrotransposon or an endogenous retrovirus or ...

(LTR). Regions in the LTR act as switches to control production of new viruses and can be triggered by proteins from either HIV or the host cell. The Psi element is involved in viral genome packaging and recognized by ''gag'' and ''rev'' proteins. The SLIP element () is involved in the frameshift in the ''gag''-''pol'' reading frame

In molecular biology, a reading frame is a way of dividing the sequence of nucleotides in a nucleic acid ( DNA or RNA) molecule into a set of consecutive, non-overlapping triplets. Where these triplets equate to amino acids or stop signals during ...

required to make functional ''pol''.

Tropism

macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

s, and microglial cell

Microglia are a type of neuroglia (glial cell) located throughout the brain and spinal cord. Microglia account for about 7% of cells found within the brain. As the resident macrophage cells, they act as the first and main form of active immune d ...

s. HIV-1 entry to macrophages and CD4+ T cells is mediated through interaction of the virion envelope glycoproteins (gp120) with the CD4 molecule on the target cells' membrane and also with chemokine

Chemokines (), or chemotactic cytokines, are a family of small cytokines or signaling proteins secreted by cells that induce directional movement of leukocytes, as well as other cell types, including endothelial and epithelial cells. In additi ...

co-receptor

A co-receptor is a cell surface receptor that binds a signalling molecule in addition to a primary receptor in order to facilitate ligand recognition and initiate biological processes, such as entry of a pathogen into a host cell.

Properties

The ...

s.

Macrophage-tropic (M-tropic) strains of HIV-1, or non-syncytia

A syncytium (; plural syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus) ...

-inducing strains (NSI; now called R5 viruses) use the ''β''-chemokine receptor, CCR5

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines.

In humans, the ''CCR5'' gene that encodes the CCR5 p ...

, for entry and are thus able to replicate in both macrophages and CD4+ T cells. This CCR5 co-receptor is used by almost all primary HIV-1 isolates regardless of viral genetic subtype. Indeed, macrophages play a key role in several critical aspects of HIV infection. They appear to be the first cells infected by HIV and perhaps the source of HIV production when CD4+ cells become depleted in the patient. Macrophages and microglial cells are the cells infected by HIV in the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all p ...

. In the tonsil

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil, two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play ...

s and adenoids

In anatomy, the adenoid, also known as the pharyngeal tonsil or nasopharyngeal tonsil, is the superior-most of the tonsils. It is a mass of lymphatic tissue located behind the nasal cavity, in the roof of the nasopharynx, where the nose blend ...

of HIV-infected patients, macrophages fuse into multinucleated giant cell

A giant cell (also known as multinucleated giant cell, or multinucleate giant cell) is a mass formed by the union of several distinct cells (usually histiocytes), often forming a granuloma. Although there is typically a focus on the pathologica ...

s that produce huge amounts of virus.

T-tropic strains of HIV-1, or syncytia

A syncytium (; plural syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell which can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus) ...

-inducing strains (SI; now called X4 viruses) replicate in primary CD4+ T cells as well as in macrophages and use the ''α''-chemokine receptor, CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR-4) also known as fusin or CD184 (cluster of differentiation 184) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''CXCR4'' gene. The protein is a CXC chemokine receptor.

Function

CXCR-4 is an alpha-chemokin ...

, for entry.

Dual-tropic HIV-1 strains are thought to be transitional strains of HIV-1 and thus are able to use both CCR5 and CXCR4 as co-receptors for viral entry.

The ''α''-chemokine SDF-1, a ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule (functional group) that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's elect ...

for CXCR4, suppresses replication of T-tropic HIV-1 isolates. It does this by down-regulating the expression of CXCR4 on the surface of HIV target cells. M-tropic HIV-1 isolates that use only the CCR5 receptor are termed R5; those that use only CXCR4 are termed X4, and those that use both, X4R5. However, the use of co-receptors alone does not explain viral tropism, as not all R5 viruses are able to use CCR5 on macrophages for a productive infection and HIV can also infect a subtype of myeloid dendritic cells, which probably constitute a reservoir

A reservoir (; from French ''réservoir'' ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam. Such a dam may be either artificial, built to store fresh water or it may be a natural formation.

Reservoirs can be created in a number of ways, including contr ...

that maintains infection when CD4+ T cell numbers have declined to extremely low levels.

Some people are resistant to certain strains of HIV. For example, people with the CCR5-Δ32

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines.

In humans, the ''CCR5'' gene that encodes the CCR5 pr ...

mutation are resistant to infection by the R5 virus, as the mutation leaves HIV unable to bind to this co-receptor, reducing its ability to infect target cells.

Sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal pene ...

is the major mode of HIV transmission. Both X4 and R5 HIV are present in the seminal fluid

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Semen is ...

, which enables the virus to be transmitted from a male to his sexual partner

Sexual partners are people who engage in sexual activity together. The sexual partners may be in a committed relationship, either on an exclusive basis or not, or engage in the sexual activity on a casual basis. They may be on intimate terms ...

. The virions can then infect numerous cellular targets and disseminate into the whole organism. However, a selection process leads to a predominant transmission of the R5 virus through this pathway. In patients infected with subtype B HIV-1, there is often a co-receptor switch in late-stage disease and T-tropic variants that can infect a variety of T cells through CXCR4. These variants then replicate more aggressively with heightened virulence that causes rapid T cell depletion, immune system collapse, and opportunistic infections that mark the advent of AIDS. HIV-positive patients acquire an enormously broad spectrum of opportunistic infections, which was particularly problematic prior to the onset of HAART therapies; however, the same infections are reported among HIV-infected patients examined post-mortem following the onset of antiretroviral therapies. Thus, during the course of infection, viral adaptation to the use of CXCR4 instead of CCR5 may be a key step in the progression to AIDS. A number of studies with subtype B-infected individuals have determined that between 40 and 50 percent of AIDS patients can harbour viruses of the SI and, it is presumed, the X4 phenotypes.

HIV-2 is much less pathogenic than HIV-1 and is restricted in its worldwide distribution to West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

. The adoption of "accessory genes" by HIV-2 and its more promiscuous

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by ma ...

pattern of co-receptor usage (including CD4-independence) may assist the virus in its adaptation to avoid innate restriction factors present in host cells. Adaptation to use normal cellular machinery to enable transmission and productive infection has also aided the establishment of HIV-2 replication in humans. A survival strategy for any infectious agent is not to kill its host, but ultimately become a commensal

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit fro ...

organism. Having achieved a low pathogenicity, over time, variants that are more successful at transmission will be selected.

Replication cycle

Entry to the cell

macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

s and CD4+ T cells

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte. T cells are one of the important white blood cells of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell re ...

by the adsorption

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the ''adsorbate'' on the surface of the ''adsorbent''. This process differs from absorption, in which a ...

of glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glyco ...

s on its surface to receptors on the target cell followed by fusion of the viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

with the target cell membrane and the release of the HIV capsid into the cell.

Entry to the cell begins through interaction of the trimeric envelope complex (gp160

''Env'' is a viral gene that encodes the protein forming the viral envelope. The expression of the ''env'' gene enables retroviruses to target and attach to specific cell types, and to infiltrate the target cell membrane.

Analysis of the struct ...

spike) on the HIV viral envelope and both CD4

In molecular biology, CD4 (cluster of differentiation 4) is a glycoprotein that serves as a co-receptor for the T-cell receptor (TCR). CD4 is found on the surface of immune cells such as T helper cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic ce ...

and a chemokine co-receptor (generally either CCR5

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines.

In humans, the ''CCR5'' gene that encodes the CCR5 p ...

or CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR-4) also known as fusin or CD184 (cluster of differentiation 184) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''CXCR4'' gene. The protein is a CXC chemokine receptor.

Function

CXCR-4 is an alpha-chemokin ...

, but others are known to interact) on the target cell surface. Gp120 binds to integrin

Integrins are transmembrane receptors that facilitate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion. Upon ligand binding, integrins activate signal transduction pathways that mediate cellular signals such as regulation of the cell cycle ...

α4β7 activating LFA-1, the central integrin involved in the establishment of virological synapse Viral synapse (or virological synapse) is a molecularly organized cellular junction that is similar in some aspects to immunological synapses. Many viruses including herpes simplex virus (HSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-lymphot ...

s, which facilitate efficient cell-to-cell spreading of HIV-1. The gp160 spike contains binding domains for both CD4 and chemokine receptors.

The first step in fusion involves the high-affinity attachment of the CD4 binding domains of gp120

Envelope glycoprotein GP120 (or gp120) is a glycoprotein exposed on the surface of the HIV envelope. It was discovered by Professors Tun-Hou Lee and Myron "Max" Essex of the Harvard School of Public Health in 1988. The 120 in its name comes from ...

to CD4. Once gp120 is bound with the CD4 protein, the envelope complex undergoes a structural change, exposing the chemokine receptor binding domains of gp120 and allowing them to interact with the target chemokine receptor. This allows for a more stable two-pronged attachment, which allows the N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

fusion peptide gp41 to penetrate the cell membrane. Repeat sequences in gp41, HR1, and HR2 then interact, causing the collapse of the extracellular portion of gp41 into a hairpin shape. This loop structure brings the virus and cell membranes close together, allowing fusion of the membranes and subsequent entry of the viral capsid.

After HIV has bound to the target cell, the HIV RNA and various enzymes, including reverse transcriptase, integrase, ribonuclease, and protease, are injected into the cell. During the microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 1 ...

-based transport to the nucleus, the viral single-strand RNA genome is transcribed into double-strand DNA, which is then integrated into a host chromosome.

HIV can infect dendritic cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. Th ...

s (DCs) by this CD4-CCR5 route, but another route using mannose-specific C-type lectin receptors such as DC-SIGN can also be used. DCs are one of the first cells encountered by the virus during sexual transmission. They are currently thought to play an important role by transmitting HIV to T cells when the virus is captured in the mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It i ...

by DCs. The presence of FEZ-1

Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''FEZ1'' gene.

This gene is an ortholog of the C. elegans unc-76 gene, which is necessary for normal axonal bundling and elongation within axon bundles. E ...

, which occurs naturally in neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa ...

s, is believed to prevent the infection of cells by HIV.

HIV-1 entry, as well as entry of many other retroviruses, has long been believed to occur exclusively at the plasma membrane. More recently, however, productive infection by pH-independent,

HIV-1 entry, as well as entry of many other retroviruses, has long been believed to occur exclusively at the plasma membrane. More recently, however, productive infection by pH-independent, clathrin-mediated endocytosis

Receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME), also called clathrin-mediated endocytosis, is a process by which cells absorb metabolites, hormones, proteins – and in some cases viruses – by the inward budding of the plasma membrane (invagination). This ...

of HIV-1 has also been reported and was recently suggested to constitute the only route of productive entry.

Replication and transcription

Shortly after the viral capsid enters the cell, an

Shortly after the viral capsid enters the cell, an enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

called reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genom ...

liberates the positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome from the attached viral proteins and copies it into a complementary DNA

In genetics, complementary DNA (cDNA) is DNA synthesized from a single-stranded RNA (e.g., messenger RNA (mRNA) or microRNA (miRNA)) template in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. cDNA is often used to express a spec ...

(cDNA) molecule. The process of reverse transcription is extremely error-prone, and the resulting mutations may cause drug resistance

Drug resistance is the reduction in effectiveness of a medication such as an antimicrobial or an antineoplastic in treating a disease or condition. The term is used in the context of resistance that pathogens or cancers have "acquired", that is ...

or allow the virus to evade the body's immune system. The reverse transcriptase also has ribonuclease activity that degrades the viral RNA during the synthesis of cDNA, as well as DNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity that creates a sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system re ...

DNA from the ''antisense'' cDNA. Together, the cDNA and its complement form a double-stranded viral DNA that is then transported into the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

. The integration of the viral DNA into the host cell's genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

is carried out by another viral enzyme called integrase

Retroviral integrase (IN) is an enzyme produced by a retrovirus (such as HIV) that integrates—forms covalent links between—its genetic information into that of the host cell it infects. Retroviral INs are not to be confused with phage in ...

.

The integrated viral DNA may then lie dormant, in the latent stage of HIV infection. To actively produce the virus, certain cellular transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The f ...

s need to be present, the most important of which is NF-''κ''B (nuclear factor kappa B), which is upregulated when T cells become activated. This means that those cells most likely to be targeted, entered and subsequently killed by HIV are those actively fighting infection.

During viral replication, the integrated DNA provirus A provirus is a virus genome that is integrated into the DNA of a host cell. In the case of bacterial viruses (bacteriophages), proviruses are often referred to as prophages. However, proviruses are distinctly different from prophages and these te ...

is transcribed into RNA. The full-length genomic RNAs (gRNA) can be packaged into new viral particles in a pseudodiploid form. The selectivity in the packaging is explained by the structural properties of the dimeric conformer of the gRNA. The gRNA dimer is characterized by a tandem three-way junction within the gRNA monomer, in which the SD and AUG hairpins, responsible for splicing and translation respectively, are sequestered and the DIS (dimerization initiation signal) hairpin is exposed.The formation of the gRNA dimer is mediated by a 'kissing' interaction between the DIS hairpin loops of the gRNA monomers. At the same time, certain guanosine residues in the gRNA are made available for binding of the nucleocapsid (NC) protein leading to the subsequent virion assembly. The labile gRNA dimer has been also reported to achieve a more stable conformation following the NC binding, in which both the DIS and the U5:AUG regions of the gRNA participate in extensive base pairing.

RNA can also be processed to produce mature messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

s (mRNAs). In most cases, this processing involves RNA splicing

RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcription (biology), transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (Messenger RNA, mRNA). It works by removing all the introns (non-cod ...

to produce mRNAs that are shorter than the full-length genome. Which part of the RNA is removed during RNA splicing determines which of the HIV protein-coding sequences is translated.

Mature HIV mRNAs are exported from the nucleus into the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

, where they are translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

to produce HIV proteins, including Rev. As the newly produced Rev protein is produced it moves to the nucleus, where it binds to full-length, unspliced copies of virus RNAs and allows them to leave the nucleus. Some of these full-length RNAs function as mRNAs that are translated to produce the structural proteins Gag and Env. Gag proteins bind to copies of the virus RNA genome to package them into new virus particles.

HIV-1 and HIV-2 appear to package their RNA differently. HIV-1 will bind to any appropriate RNA. HIV-2 will preferentially bind to the mRNA that was used to create the Gag protein itself.

Recombination

Two RNA genomes are encapsidated in each HIV-1 particle (see Structure and genome of HIV). Upon infection and replication catalyzed by reverse transcriptase, recombination between the two genomes can occur. Recombination occurs as the single-strand, positive-sense RNA genomes are reverse transcribed to form DNA. During reverse transcription, the nascent DNA can switch multiple times between the two copies of the viral RNA. This form of recombination is known as copy-choice. Recombination events may occur throughout the genome. Anywhere from two to 20 recombination events per genome may occur at each replication cycle, and these events can rapidly shuffle the genetic information that is transmitted from parental to progeny genomes. Viral recombination produces genetic variation that likely contributes to theevolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of resistance to anti-retroviral therapy

The management of HIV/AIDS normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs as a strategy to control HIV infection. There are several classes of antiretroviral agents that act on different stages of the HIV life-cycle. The use of multiple ...

. Recombination may also contribute, in principle, to overcoming the immune defenses of the host. Yet, for the adaptive advantages of genetic variation to be realized, the two viral genomes packaged in individual infecting virus particles need to have arisen from separate progenitor parental viruses of differing genetic constitution. It is unknown how often such mixed packaging occurs under natural conditions.

Bonhoeffer ''et al.'' suggested that template switching by reverse transcriptase acts as a repair process to deal with breaks in the single-stranded RNA genome. In addition, Hu and Temin suggested that recombination is an adaptation for repair of damage in the RNA genomes. Strand switching (copy-choice recombination) by reverse transcriptase could generate an undamaged copy of genomic DNA from two damaged single-stranded RNA genome copies. This view of the adaptive benefit of recombination in HIV could explain why each HIV particle contains two complete genomes, rather than one. Furthermore, the view that recombination is a repair process implies that the benefit of repair can occur at each replication cycle, and that this benefit can be realized whether or not the two genomes differ genetically. On the view that recombination in HIV is a repair process, the generation of recombinational variation would be a consequence, but not the cause of, the evolution of template switching.

HIV-1 infection causes chronic inflammation and production of reactive oxygen species

In chemistry, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (). Examples of ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen, and alpha-oxygen.

The reduction of molecular oxygen () p ...

. Thus, the HIV genome may be vulnerable to oxidative damage

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal r ...

, including breaks in the single-stranded RNA. For HIV, as well as for viruses in general, successful infection depends on overcoming host defense strategies that often include production of genome-damaging reactive oxygen species. Thus, Michod ''et al.'' suggested that recombination by viruses is an adaptation for repair of genome damage, and that recombinational variation is a byproduct that may provide a separate benefit.

Assembly and release

The final step of the viral cycle, assembly of new HIV-1 virions, begins at the

The final step of the viral cycle, assembly of new HIV-1 virions, begins at the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

of the host cell. The Env polyprotein (gp160) goes through the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ...

and is transported to the Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles i ...

where it is cleaved by furin

Furin is a protease, a proteolytic enzyme that in humans and other animals is encoded by the ''FURIN'' gene. Some proteins are inactive when they are first synthesized, and must have sections removed in order to become active. Furin cleaves these s ...

resulting in the two HIV envelope glycoproteins, gp41 and gp120

Envelope glycoprotein GP120 (or gp120) is a glycoprotein exposed on the surface of the HIV envelope. It was discovered by Professors Tun-Hou Lee and Myron "Max" Essex of the Harvard School of Public Health in 1988. The 120 in its name comes from ...

. These are transported to the plasma membrane of the host cell where gp41 anchors gp120 to the membrane of the infected cell. The Gag (p55) and Gag-Pol (p160) polyproteins also associate with the inner surface of the plasma membrane along with the HIV genomic RNA as the forming virion begins to bud from the host cell. The budded virion is still immature as the gag polyproteins still need to be cleaved into the actual matrix, capsid and nucleocapsid proteins. This cleavage is mediated by the packaged viral protease and can be inhibited by antiretroviral drugs of the protease inhibitor class. The various structural components then assemble to produce a mature HIV virion. Only mature virions are then able to infect another cell.

Spread within the body

The classical process of infection of a cell by a virion can be called "cell-free spread" to distinguish it from a more recently recognized process called "cell-to-cell spread". In cell-free spread (see figure), virus particles bud from an infected T cell, enter the blood or

The classical process of infection of a cell by a virion can be called "cell-free spread" to distinguish it from a more recently recognized process called "cell-to-cell spread". In cell-free spread (see figure), virus particles bud from an infected T cell, enter the blood or extracellular fluid

In cell biology, extracellular fluid (ECF) denotes all body fluid outside the cells of any multicellular organism. Total body water in healthy adults is about 60% (range 45 to 75%) of total body weight; women and the obese typically have a low ...

and then infect another T cell following a chance encounter. HIV can also disseminate by direct transmission from one cell to another by a process of cell-to-cell spread, for which two pathways have been described. Firstly, an infected T cell can transmit virus directly to a target T cell via a virological synapse Viral synapse (or virological synapse) is a molecularly organized cellular junction that is similar in some aspects to immunological synapses. Many viruses including herpes simplex virus (HSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-lymphot ...

. Secondly, an antigen-presenting cell

An antigen-presenting cell (APC) or accessory cell is a cell that displays antigen bound by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on its surface; this process is known as antigen presentation. T cells may recognize these complexes usi ...

(APC), such as a macrophage or dendritic cell, can transmit HIV to T cells by a process that either involves productive infection (in the case of macrophages) or capture and transfer of virions ''in trans'' (in the case of dendritic cells). Whichever pathway is used, infection by cell-to-cell transfer is reported to be much more efficient than cell-free virus spread. A number of factors contribute to this increased efficiency, including polarised virus budding towards the site of cell-to-cell contact, close apposition of cells, which minimizes fluid-phase diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical ...

of virions, and clustering of HIV entry receptors on the target cell towards the contact zone. Cell-to-cell spread is thought to be particularly important in lymphoid tissue

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic or lymphoid o ...

s, where CD4+ T cells are densely packed and likely to interact frequently. Intravital imaging studies have supported the concept of the HIV virological synapse ''in vivo''. The many dissemination mechanisms available to HIV contribute to the virus's ongoing replication in spite of anti-retroviral therapies.

Genetic variability

mutation rate

In genetics, the mutation rate is the frequency of new mutations in a single gene or organism over time. Mutation rates are not constant and are not limited to a single type of mutation; there are many different types of mutations. Mutation rates ...

of approximately 3 x 10−5 per nucleotide base per cycle of replication and recombinogenic properties of reverse transcriptase.

This complex scenario leads to the generation of many variants of HIV in a single infected patient in the course of one day. This variability is compounded when a single cell is simultaneously infected by two or more different strains of HIV. When simultaneous infection occurs, the genome of progeny virions may be composed of RNA strands from two different strains. This hybrid virion then infects a new cell where it undergoes replication. As this happens, the reverse transcriptase, by jumping back and forth between the two different RNA templates, will generate a newly synthesized retroviral DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. T ...

that is a recombinant between the two parental genomes. This recombination is most obvious when it occurs between subtypes.

The closely related simian immunodeficiency virus

''Simian immunodeficiency virus'' (''SIV'') is a species of retrovirus that cause persistent infections in at least 45 species of non-human primates. Based on analysis of strains found in four species of monkeys from Bioko Island, which was iso ...

(SIV) has evolved into many strains, classified by the natural host species. SIV strains of the African green monkey

''Chlorocebus'' is a genus of medium-sized primates from the family of Old World monkeys. Six species are currently recognized, although some people classify them all as a single species with numerous subspecies. Either way, they make up the ...

(SIVagm) and sooty mangabey

The sooty mangabey (''Cercocebus atys'') is an Old World monkey found in forests from Senegal in a margin along the coast down to the Ivory Coast.

Habitat and ecology

The sooty mangabey is native to tropical West Africa, being found in Guinea, ...

(SIVsmm) are thought to have a long evolutionary history with their hosts. These hosts have adapted to the presence of the virus, which is present at high levels in the host's blood, but evokes only a mild immune response, does not cause the development of simian AIDS, and does not undergo the extensive mutation and recombination typical of HIV infection in humans.

In contrast, when these strains infect species that have not adapted to SIV ("heterologous" or similar hosts such as rhesus or cynomologus macaques), the animals develop AIDS and the virus generates genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

similar to what is seen in human HIV infection. Chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative t ...

SIV (SIVcpz), the closest genetic relative of HIV-1, is associated with increased mortality and AIDS-like symptoms in its natural host. SIVcpz appears to have been transmitted relatively recently to chimpanzee and human populations, so their hosts have not yet adapted to the virus. This virus has also lost a function of the '' nef'' gene that is present in most SIVs. For non-pathogenic SIV variants, ''nef'' suppresses T cell activation through the CD3 marker. ''Nef'' function in non-pathogenic forms of SIV is to downregulate

In the biological context of organisms' production of gene products, downregulation is the process by which a cell decreases the quantity of a cellular component, such as RNA or protein, in response to an external stimulus. The complementary pr ...

expression of inflammatory cytokines, MHC-1, and signals that affect T cell trafficking. In HIV-1 and SIVcpz, ''nef'' does not inhibit T-cell activation and it has lost this function. Without this function, T cell depletion is more likely, leading to immunodeficiency.

Three groups of HIV-1 have been identified on the basis of differences in the envelope (''env'') region: M, N, and O. Group M is the most prevalent and is subdivided into eight subtypes (or clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

s), based on the whole genome, which are geographically distinct. The most prevalent are subtypes B (found mainly in North America and Europe), A and D (found mainly in Africa), and C (found mainly in Africa and Asia); these subtypes form branches in the phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

representing the lineage of the M group of HIV-1. Co-infection

Coinfection is the simultaneous infection of a host by multiple pathogen species. In virology, coinfection includes simultaneous infection of a single cell by two or more virus particles. An example is the coinfection of liver cells with hepatiti ...

with distinct subtypes gives rise to circulating recombinant forms (CRFs). In 2000, the last year in which an analysis of global subtype prevalence was made, 47.2% of infections worldwide were of subtype C, 26.7% were of subtype A/CRF02_AG, 12.3% were of subtype B, 5.3% were of subtype D, 3.2% were of CRF_AE, and the remaining 5.3% were composed of other subtypes and CRFs. Most HIV-1 research is focused on subtype B; few laboratories focus on the other subtypes. The existence of a fourth group, "P", has been hypothesised based on a virus isolated in 2009. The strain is apparently derived from gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

SIV (SIVgor), first isolated from western lowland gorilla

The western lowland gorilla (''Gorilla gorilla gorilla'') is one of two Critically Endangered subspecies of the western gorilla (''Gorilla gorilla'') that lives in montane, primary and secondary forest and lowland swampland in central Af ...

s in 2006.

HIV-2's closest relative is SIVsm, a strain of SIV found in sooty mangabees. Since HIV-1 is derived from SIVcpz, and HIV-2 from SIVsm, the genetic sequence of HIV-2 is only partially homologous to HIV-1 and more closely resembles that of SIVsm.

Diagnosis

pregnant women

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops ( gestates) inside a woman's uterus (womb). A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Pregnancy usually occurs by sexual intercourse, but ca ...

attending urban health facilities were counselled, tested or received their test results. Again, this proportion is even lower in rural health facilities. Since donors may therefore be unaware of their infection, donor blood and blood products used in medicine and medical research

Medical research (or biomedical research), also known as experimental medicine, encompasses a wide array of research, extending from " basic research" (also called ''bench science'' or ''bench research''), – involving fundamental scienti ...

are routinely screened for HIV.

HIV-1 testing is initially done using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence ...

(ELISA) to detect antibodies to HIV-1. Specimens with a non-reactive result from the initial ELISA are considered HIV-negative, unless new exposure to an infected partner or partner of unknown HIV status has occurred. Specimens with a reactive ELISA result are retested in duplicate. If the result of either duplicate test is reactive, the specimen is reported as repeatedly reactive and undergoes confirmatory testing with a more specific supplemental test (e.g., a polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) ...

(PCR), western blot

The western blot (sometimes called the protein immunoblot), or western blotting, is a widely used analytical technique in molecular biology and immunogenetics to detect specific proteins in a sample of tissue homogenate or extract. Besides detect ...

or, less commonly, an immunofluorescence assay

Immunofluorescence is a technique used for light microscopy with a fluorescence microscope and is used primarily on microbiological samples. This technique uses the specificity of antibodies to their antigen to target fluorescent dyes to specifi ...

(IFA)). Only specimens that are repeatedly reactive by ELISA and positive by IFA or PCR or reactive by western blot are considered HIV-positive and indicative of HIV infection. Specimens that are repeatedly ELISA-reactive occasionally provide an indeterminate western blot result, which may be either an incomplete antibody response to HIV in an infected person or nonspecific reactions in an uninfected person.

Although IFA can be used to confirm infection in these ambiguous cases, this assay is not widely used. In general, a second specimen should be collected more than a month later and retested for persons with indeterminate western blot results. Although much less commonly available, nucleic acid test

A nucleic acid test (NAT) is a technique used to detect a particular nucleic acid sequence and thus usually to detect and identify a particular species or subspecies of organism, often a virus or bacterium that acts as a pathogen in blood, tissu ...

ing (e.g., viral RNA or proviral DNA amplification method) can also help diagnosis in certain situations. In addition, a few tested specimens might provide inconclusive results because of a low quantity specimen. In these situations, a second specimen is collected and tested for HIV infection.

Modern HIV testing is extremely accurate, when the window period

In medicine, the window period for a test designed to detect a specific disease (particularly infectious disease) is the time between first infection and when the test can reliably detect that infection. In antibody-based testing, the window peri ...

is taken into consideration. A single screening test is correct more than 99% of the time. The chance of a false-positive result in a standard two-step testing protocol is estimated to be about 1 in 250,000 in a low risk population. Testing post-exposure is recommended immediately and then at six weeks, three months, and six months.

The latest recommendations of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention