H.M.S. Beagle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Beagle'' was a 10-gun

/ref> Faced with the more difficult part of the survey in the desolate waters of Tierra del Fuego, Captain Stokes fell into a deep depression. At Port Famine on the

FitzRoy had been given reason to hope that the South American Survey would be continued under his command, but when the Lords of the Admiralty appeared to abandon the plan, he made alternative arrangements to return the Fuegians. A kind uncle heard of this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon afterwards FitzRoy heard that he was to be appointed commander of to go to Tierra del Fuego, but due to her poor condition ''Beagle'' was substituted for the voyage. FitzRoy was re-appointed as commander on 27 June 1831 and ''Beagle'' was commissioned on 4 July 1831 under his command, with Lieutenants

FitzRoy had been given reason to hope that the South American Survey would be continued under his command, but when the Lords of the Admiralty appeared to abandon the plan, he made alternative arrangements to return the Fuegians. A kind uncle heard of this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon afterwards FitzRoy heard that he was to be appointed commander of to go to Tierra del Fuego, but due to her poor condition ''Beagle'' was substituted for the voyage. FitzRoy was re-appointed as commander on 27 June 1831 and ''Beagle'' was commissioned on 4 July 1831 under his command, with Lieutenants  ''Beagle'' was immediately taken into dock at Devonport for extensive rebuilding and refitting. As she required a new deck, FitzRoy had the upper-deck raised considerably, by aft and forward. The ''Cherokee''-class ships had the reputation of being "

''Beagle'' was immediately taken into dock at Devonport for extensive rebuilding and refitting. As she required a new deck, FitzRoy had the upper-deck raised considerably, by aft and forward. The ''Cherokee''-class ships had the reputation of being "

''Beagle'' was originally scheduled to leave on 24 October 1831, but because of delays in her preparations the departure was delayed until December. Setting forth on what was to become a ground-breaking scientific expedition, she departed from Devonport on 10 December. Due to bad weather her first stop was just a few miles ahead, at Barn Pool, on the west side of

''Beagle'' was originally scheduled to leave on 24 October 1831, but because of delays in her preparations the departure was delayed until December. Setting forth on what was to become a ground-breaking scientific expedition, she departed from Devonport on 10 December. Due to bad weather her first stop was just a few miles ahead, at Barn Pool, on the west side of

In the six months after returning from the second voyage, some light repairs were made and ''Beagle'' was commissioned to survey large parts of the coast of Australia under the command of Commander

In the six months after returning from the second voyage, some light repairs were made and ''Beagle'' was commissioned to survey large parts of the coast of Australia under the command of Commander

Surveys in November 2003 showed that there are the remains of substantial material within the dock that could be parts of the ship itself. An old

Surveys in November 2003 showed that there are the remains of substantial material within the dock that could be parts of the ship itself. An old

Darwin Online – bibliography

''Proceedings'' of the first and second expeditions, and Darwin's ''Journal'' (''The Voyage of the ''Beagle). * list includes ''The Voyage of the ''Beagle *

''Discoveries in Australia'', Volume 1Volume 2

British Atmospheric Data Centre

''Sketch of the Surveying Voyages of his Majesty's Ships ''Adventure'' and ''Beagle'', 1825–1836. Commanded by Captains P. P. King, P. Stokes, and R. Fitz-Roy, Royal Navy''

''Journal of the Geological Society of London'' 6: 311–343

The sympiesometer of Alexander Adie

The replica HMS ''Beagle'' project

BBC News – Darwin's ''Beagle'' ship 'found'

* ttp://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/south_west/5190734.stm BBC News – Plans to build HMS ''Beagle'' replica for 2009 Darwin bicentenary.

Former official blog of the building process for the full size HMS ''Beagle'' replica.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Beagle, Hms Charles Darwin Cherokee-class brig-sloops Exploration of Western Australia Exploration ships of the United Kingdom Individual sailing vessels Brig-sloops of the Royal Navy Ships built in Woolwich 1820 ships Maritime exploration of Australia

brig-sloop

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, one of more than 100 ships of this class. The vessel, constructed at a cost of £7,803 (roughly equivalent to £ in 2018), was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English Royal Navy Dockyard, naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 1 ...

on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

. Later reports say the ship took part in celebrations of the coronation of King George IV of the United Kingdom, passing through the old London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It r ...

, and was the first rigged man-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed wi ...

afloat upriver of the bridge. There was no immediate need for ''Beagle'' so she " lay in ordinary", moored afloat but without masts or rigging. She was then adapted as a survey barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel with three or more mast (sailing), masts having the fore- and mainmasts Square rig, rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) Fore-and-aft rig, rigged fore and aft. Som ...

and took part in three survey expeditions.

The second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' is notable for carrying the recently graduated naturalist Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

around the world. While the survey work was carried out, Darwin travelled and researched geology, natural history and ethnology onshore. He gained fame by publishing his diary journal, best known as ''The Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

'', and his findings played a pivotal role in the formation of his scientific theories on evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

and natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

.

Design and construction

The of 10-gun brig-sloops was designed by Sir Henry Peake in 1807, and eventually over 100 were constructed. The working drawings for HMS ''Beagle'' and HMS ''Barracouta'' were issued to theWoolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English Royal Navy Dockyard, naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 1 ...

on 16 February 1817, and amended in coloured ink on 16 July 1817 with modifications to increase the height of the bulwarks (the sides of the ship extended above the upper deck) by an amount varying from at the stem to at the stern. ''Beagle''s keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid in June 1818, construction cost £7,803, and the ship was launched on 11 May 1820.

The first reported task of the ship was a part in celebrations of the coronation of King George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

; in his 1846 ''Journal'', John Lort Stokes

Admiral John Lort Stokes, RN (1 August 1811 – 11 June 1885)Although 1812 is frequently given as Stokes's year of birth, it has been argued by author Marsden Hordern that Stokes was born in 1811, citing a letter by fellow naval officer Crawford ...

said that the ship was taken up the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

to salute the coronation, passing through the old London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It r ...

, and was the first rigged man-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed wi ...

afloat upriver of the bridge.

First voyage (1826–1830)

CaptainPringle Stokes

Pringle Stokes (23 April 1793 – 12 August 1828) was a British naval officer who served in HMS '' Owen Glendower'' on a voyage around Cape Horn to the Pacific coast of South America, and on the West African coast fighting the slave trade.

He th ...

was appointed captain of ''Beagle'' on 7 September 1825, and the ship was allocated to the surveying section of the Hydrographic Office

A hydrographic office is an organization which is devoted to acquiring and publishing hydrographic information.

Historically, the main tasks of hydrographic offices were the conduction of hydrographic surveys and the publication of nautical cha ...

. On 27 September 1825 ''The Beagle'' docked at Woolwich to be repaired and fitted out for her new duties. Her guns were reduced from ten cannon to six and a mizzen

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation ligh ...

mast was added to improve her handling, thereby changing her from a brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

to a bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, ...

(or barque).

'' The Beagle'' set sail from Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

on 22 May 1826 on her first voyage, under the command of Captain Stokes. The mission was to accompany the larger ship HMS ''Adventure'' (380 tons) on a hydrographic survey of Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

and Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla G ...

, under the overall command of the Australian Captain Phillip Parker King

Rear Admiral Phillip Parker King, FRS, RN (13 December 1791 – 26 February 1856) was an early explorer of the Australian and Patagonian coasts.

Early life and education

King was born on Norfolk Island, to Philip Gidley King and Anna Jo ...

, commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

and surveyor.

On 3 March 1827 in the Barbara Channel, the ''Beagle'' encountered a boat with survivors of the sealer , which had wrecked in Cockburn Channel

The Cockburn Channel () is a channel that separates the Brecknock Peninsula, which is the westernmost projection of the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, from Clarence Island, Capitán Aracena Island and other minor islands in Chile. It is located ...

on 16 December 1826. Stokes sent two launches to rescue the other survivors who were encamped there.Dictionary of Falklands Biography – Brisbane, Matthew (1797–1833). Retrieved 1 September 2021./ref> Faced with the more difficult part of the survey in the desolate waters of Tierra del Fuego, Captain Stokes fell into a deep depression. At Port Famine on the

Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

he locked himself in his cabin for 14 days, then after getting over-excited and talking of preparing for the next cruise, shot himself on 2 August 1828. Following four days of delirium Stokes recovered slightly, but then his condition deteriorated and he died on 12 August 1828. Captain Parker King then replaced Stokes with the First Lieutenant of ''Beagle'', Lieutenant William George Skyring as commander, and both ships sailed to Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

. On 13 October King sailed ''Adventure'' to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

for refitting and provisions. During this work Rear Admiral Sir Robert Otway

Admiral Sir Robert Waller Otway, 1st Baronet, GCB (26 April 1770 – 12 May 1846) was a senior Royal Navy officer of the early nineteenth century who served extensively as a sea captain during the Napoleonic War and later supported the Brazilia ...

, commander in chief of the South American station, arrived aboard and announced his decision that ''Beagle'' was also to be brought to Montevideo for repairs, and that he intended to supersede Skyring. When ''Beagle'' arrived, Otway put the ship under the command of his aide, Flag Lieutenant Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

.

The 23-year-old aristocrat FitzRoy proved an able commander and meticulous surveyor. In one incident a group of Fuegians

Fuegians are the indigenous inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. In English, the term originally referred to the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego. In Spanish, the term ''fueguino'' can refer to any person from ...

stole a ship's boat, and FitzRoy took their families on board as hostages. Eventually he held two men, a girl and a boy, who was given the name of Jemmy Button

Orundellico, known as "Jeremy Button" or "Jemmy Button" (c. 1815–1864), was a member of the Yaghan (or Yámana) people from islands around Tierra del Fuego, in modern Chile and Argentina. He was taken to England by Captain FitzRoy in HMS ''B ...

, and these four native Fuegians were taken back with them when ''Beagle'' returned to England on 14 October 1830. During their brief sojourn in England, Boat Memory, the most promising of the four, died of smallpox.

During this survey, the Beagle Channel

Beagle Channel (; Yahgan: ''Onašaga'') is a strait in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago, on the extreme southern tip of South America between Chile and Argentina. The channel separates the larger main island of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego fr ...

was identified and named after the ship.

The log book from the first voyage, in Captain FitzRoy's handwriting, was acquired at auction at Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, and ...

by the ''Museo Naval de la Nación'' (under the administration of the Argentine Navy

The Argentine Navy (ARA; es, Armada de la República Argentina). This forms the basis for the navy's ship prefix "ARA". is the navy of Argentina. It is one of the three branches of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic, together with the ...

) located in Tigre, Buenos Aires Province

Tigre (, ''Tiger'') is a city in the Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, situated in the north of Greater Buenos Aires, north of Buenos Aires city. Tigre lies on the Paraná Delta and is a tourist and weekend destination, reachable by bus and tr ...

, Argentina, where it is now preserved.

Second voyage (1831–1836)

FitzRoy had been given reason to hope that the South American Survey would be continued under his command, but when the Lords of the Admiralty appeared to abandon the plan, he made alternative arrangements to return the Fuegians. A kind uncle heard of this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon afterwards FitzRoy heard that he was to be appointed commander of to go to Tierra del Fuego, but due to her poor condition ''Beagle'' was substituted for the voyage. FitzRoy was re-appointed as commander on 27 June 1831 and ''Beagle'' was commissioned on 4 July 1831 under his command, with Lieutenants

FitzRoy had been given reason to hope that the South American Survey would be continued under his command, but when the Lords of the Admiralty appeared to abandon the plan, he made alternative arrangements to return the Fuegians. A kind uncle heard of this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon afterwards FitzRoy heard that he was to be appointed commander of to go to Tierra del Fuego, but due to her poor condition ''Beagle'' was substituted for the voyage. FitzRoy was re-appointed as commander on 27 June 1831 and ''Beagle'' was commissioned on 4 July 1831 under his command, with Lieutenants John Clements Wickham

John Clements Wickham (21 November 17986 January 1864) was a Scottish explorer, naval officer, magistrate and administrator. He was first lieutenant on during its second survey mission, 1831–1836, under captain Robert FitzRoy. The young ...

and Bartholomew James Sulivan

Admiral Sir Bartholomew James Sulivan, (18 November 1810 – 1 January 1890) was a British naval officer and hydrographer. He was a leading advocate of the value of nautical surveying in relation to naval operations.

Sulivan was born at Mylor ...

.

''Beagle'' was immediately taken into dock at Devonport for extensive rebuilding and refitting. As she required a new deck, FitzRoy had the upper-deck raised considerably, by aft and forward. The ''Cherokee''-class ships had the reputation of being "

''Beagle'' was immediately taken into dock at Devonport for extensive rebuilding and refitting. As she required a new deck, FitzRoy had the upper-deck raised considerably, by aft and forward. The ''Cherokee''-class ships had the reputation of being "coffin

A coffin is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, either for burial or cremation.

Sometimes referred to as a casket, any box in which the dead are buried is a coffin, and while a casket was originally regarded as a box for jewel ...

" brigs, which handled badly and were prone to sinking. Apart from increasing headroom below, the raised deck made ''Beagle'' less liable to top-heaviness and possible capsize in heavy weather by reducing the volume of water that could collect on top of the upper deck, trapped aboard by the gunwale

The gunwale () is the top edge of the hull of a ship or boat.

Originally the structure was the "gun wale" on a sailing warship, a horizontal reinforcing band added at and above the level of a gun deck to offset the stresses created by firing ...

s. Additional sheathing added to the hull added about seven tons to her burthen

Burden or burthen may refer to:

People

* Burden (surname), people with the surname Burden

Places

* Burden, Kansas, United States

* Burden, Luxembourg

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Burden'' (2018 film), an American drama film

* ''T ...

and perhaps fifteen to her displacement.

The ship was one of the first to be fitted with the lightning conductor

A lightning rod or lightning conductor (British English) is a metal rod mounted on a structure and intended to protect the structure from a lightning strike. If lightning hits the structure, it will preferentially strike the rod and be conducte ...

invented by William Snow Harris

Sir William Snow Harris (1 April 1791 – 22 January 1867) was a British physician and electrical researcher, nicknamed Thunder-and-Lightning Harris, and noted for his invention of a successful system of lightning conductors for ships. It took ...

. FitzRoy spared no expense in her fitting out, which included 22 chronometers, and five examples of the ''Sympiesometer

A sympiesometer is a compact and lightweight type of barometer that was widely used on ships in the 19th century. The sensitivity of this barometer was also used to measure altitude.

The sympiesometer consists of two parts. One is a traditional m ...

'', a kind of mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

-free barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

patented by Alexander Adie

Alexander James Adie FRSE MWS (1775, Edinburgh – 4 December 1858, Edinburgh) was a Scottish maker of medical instruments, optician and meteorologist. He was the inventor of the sympiesometer, patented in 1818.

Life

He was born the son of Jo ...

which was favoured by FitzRoy as giving the accurate readings required by the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

. To reduce magnetic interference with the navigational instruments, FitzRoy proposed replacing the iron guns with brass guns, but the Admiralty turned this request down. (When the ship reached Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

in April 1832, he used his own funds for replacements: the ship now had a "six-pound boat-carronade" on a turntable on the forecastle, two brass six-pound guns before the main-mast, and aft of it another four brass guns; two of these were nine-pound, and the other two six-pound.)

FitzRoy had found a need for expert advice on geology during the first voyage, and had resolved that if on a similar expedition, he would "endeavour to carry out a person qualified to examine the land; while the officers, and myself, would attend to hydrography." Command in that era could involve stress and loneliness, as shown by the suicide of Captain Stokes, and FitzRoy's own uncle Viscount Castlereagh

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judici ...

had committed suicide under stress of overwork. His attempts to get a friend to accompany him fell through, and he asked his friend and superior Captain Francis Beaufort

Rear-Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort (; 27 May 1774 – 17 December 1857) was an Irish hydrographer, rear admiral of the Royal Navy, and creator of the Beaufort cipher and the Beaufort scale.

Early life

Francis Beaufort was descended f ...

to seek a gentleman naturalist as a self-financing passenger who would give him company during the voyage. A sequence of inquiries led to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

, a young gentleman on his way to becoming a rural clergyman, joining the voyage. FitzRoy was influenced by the physiognomy

Physiognomy (from the Greek , , meaning "nature", and , meaning "judge" or "interpreter") is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the general ...

of Lavater

Johann Kaspar (or Caspar) Lavater (; 15 November 1741 – 2 January 1801) was a Swiss poet, writer, philosopher, physiognomist and theologian.

Early life

Lavater was born in Zürich, and was educated at the '' Gymnasium'' there, where J. J. ...

, and Darwin recounted in his autobiography that he was nearly "rejected, on account of the shape of my nose! He was an ardent disciple of Lavater, & was convinced that he could judge a man's character by the outline of his features; & he doubted whether anyone with my nose could possess sufficient energy & determination for the voyage."

''Beagle'' was originally scheduled to leave on 24 October 1831, but because of delays in her preparations the departure was delayed until December. Setting forth on what was to become a ground-breaking scientific expedition, she departed from Devonport on 10 December. Due to bad weather her first stop was just a few miles ahead, at Barn Pool, on the west side of

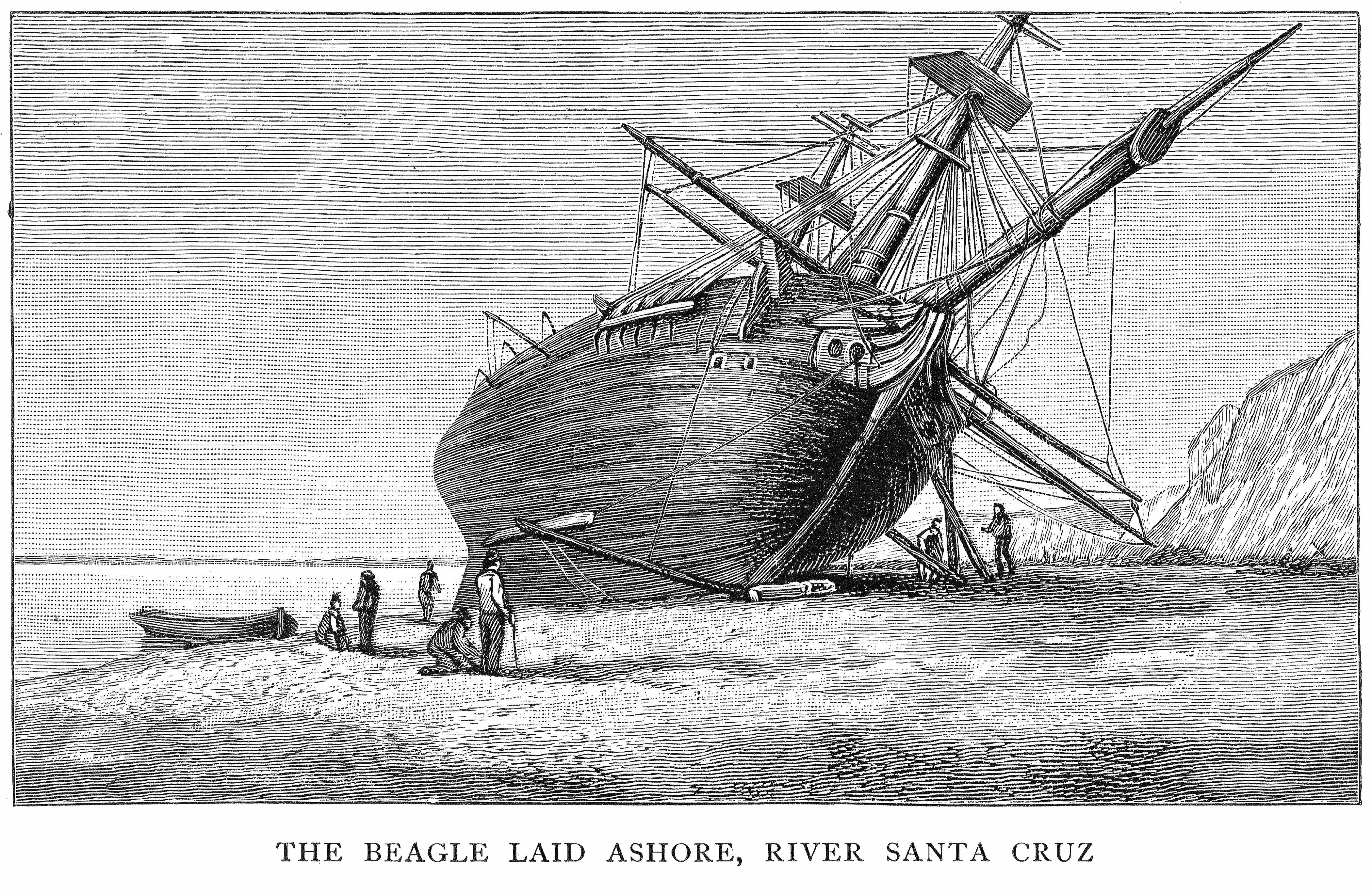

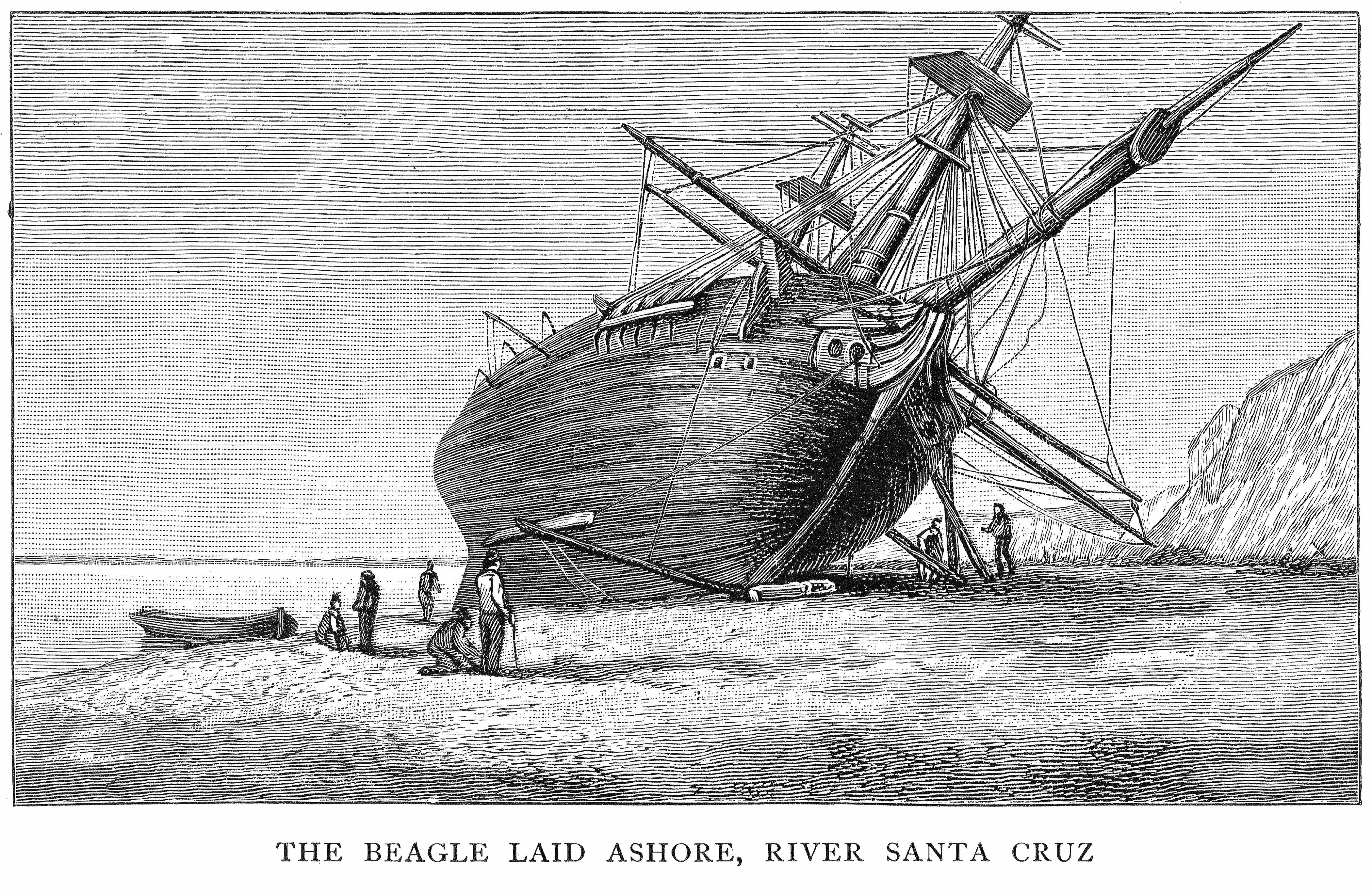

''Beagle'' was originally scheduled to leave on 24 October 1831, but because of delays in her preparations the departure was delayed until December. Setting forth on what was to become a ground-breaking scientific expedition, she departed from Devonport on 10 December. Due to bad weather her first stop was just a few miles ahead, at Barn Pool, on the west side of Plymouth Sound

Plymouth Sound, or locally just The Sound, is a deep inlet or sound in the English Channel near Plymouth in England.

Description

Its southwest and southeast corners are Penlee Point in Cornwall and Wembury Point in Devon, a distance of abo ...

. ''Beagle'' left anchorage from Barn Pool on 27 December, passing the nearby town of Plymouth. After completing extensive surveys in South America she returned via New Zealand, Sydney, Hobart Town (6 February 1836), to Falmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth ( ; kw, Aberfala) is a town, civil parish and port on the River Fal on the south coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a total resident population of 21,797 (2011 census).

Etymology

The name Falmouth is of English or ...

, England, on 2 October 1836.

Darwin had kept a diary of his experiences, and combined this with details from his scientific notes as the book titled ''Journal and Remarks'', published in 1839 as the third volume of the official account of the expedition. This travelogue and scientific journal was widely popular, and was reprinted many times with various titles and a revised second edition, becoming known as ''The Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

''.

Third voyage (1837–1843)

In the six months after returning from the second voyage, some light repairs were made and ''Beagle'' was commissioned to survey large parts of the coast of Australia under the command of Commander

In the six months after returning from the second voyage, some light repairs were made and ''Beagle'' was commissioned to survey large parts of the coast of Australia under the command of Commander John Clements Wickham

John Clements Wickham (21 November 17986 January 1864) was a Scottish explorer, naval officer, magistrate and administrator. He was first lieutenant on during its second survey mission, 1831–1836, under captain Robert FitzRoy. The young ...

, who had been a lieutenant on the second voyage, with assistant surveyor Lieutenant John Lort Stokes

Admiral John Lort Stokes, RN (1 August 1811 – 11 June 1885)Although 1812 is frequently given as Stokes's year of birth, it has been argued by author Marsden Hordern that Stokes was born in 1811, citing a letter by fellow naval officer Crawford ...

who had been a midshipman on the first voyage of ''Beagle'', then mate and assistant surveyor on the second voyage (no relation to Pringle Stokes). They left Woolwich on 9 June 1837, towed by HM Steamer ''Boxer'', and after reaching Plymouth spent the remainder of the month adjusting their instruments. They set off from Plymouth Sound on the morning of 5 July 1837, and sailed south with stops for observations at Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitants as of Janu ...

, Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

and Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

.

They reached the Swan River (modern Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, Australia) on 15 November 1837. Their survey started with the western coast between there and the Fitzroy River, Western Australia

The Fitzroy River is located in the Kimberley (Western Australia), West Kimberley region of Western Australia. It has 20 tributary, tributaries and its catchment occupies an area of , within the Canning Basin and the Timor Sea drainage divisio ...

, then surveyed both shores of the Bass Strait

Bass Strait () is a strait separating the island state of Tasmania from the Australian mainland (more specifically the coast of Victoria, with the exception of the land border across Boundary Islet). The strait provides the most direct waterwa ...

at the southeast corner of the continent. To aid ''Beagle'' in her surveying operations in Bass Strait, the Colonial cutter ''Vansittart'', of Van Diemen's Land, was most liberally lent by His Excellency Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

, and placed under the command of Mr Charles Codrington Forsyth, the senior mate, assisted by Mr Pasco, another of her mates. In May 1839, they sailed north to survey the shores of the Arafura Sea

The Arafura Sea (or Arafuru Sea) lies west of the Pacific Ocean, overlying the continental shelf between Australia and Western New Guinea (also called Papua), which is the Indonesian part of the Island of New Guinea.

Geography

The Arafura Sea is ...

opposite Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East Timor–Indonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

. When Wickham fell ill and resigned, the command was taken over in March 1841 by Lieutenant John Lort Stokes who continued the survey. The third voyage was completed in 1843.

Numerous places around the coast were named by Wickham, and subsequently by Stokes when he became captain, often honouring eminent people or the members of the crew. On 9 October 1839 Wickham named Port Darwin

Port Darwin is the port in Darwin, Northern Territory, in northern Australia. The port has operated in a number of locations, including Stokes Hill Wharf, Cullen Bay and East Arm Wharf. In 2015, a 99-year lease was granted to the Chinese-owned ...

, which was first sighted by Stokes, in honour of their former shipmate Charles Darwin. They were reminded of him (and his "geologising") by the discovery there of a new fine-grained sandstone. A settlement there became the town of Palmerston in 1869, and was renamed Darwin in 1911 (not to be confused with the present day city of Palmerston Palmerston may refer to:

People

* Christie Palmerston (c. 1851–1897), Australian explorer

* Several prominent people have borne the title of Viscount Palmerston

** Henry Temple, 1st Viscount Palmerston (c. 1673–1757), Irish nobleman and ...

near Darwin).

During this survey, the Beagle Gulf

Beagle Gulf is a gulf in the Northern Territory of Australia which opens on its west side to the Timor Sea. The gulf is bounded to the south by the mainland and to the north by Bathurst and Melville Islands. It is connected to Van Diemen Gulf ...

was named after the ship.

''Nicotiana benthamiana

''Nicotiana benthamiana'', colloquially known as benth or benthi, is a species of ''Nicotiana'' indigenous to Australia. It is a close relative of tobacco.

A synonym for this species is ''Nicotiana suaveolens'' var. ''cordifolia'', a descrip ...

'', a species of tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

being used as a platform for the production of recombinant pharmaceutical proteins, was first collected for scientific study on the north coast of Australia by Benjamin Bynoe during this voyage.

Final years

In 1845, ''Beagle'' was refitted as a staticcoastguard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

watch vessel like many similar watch ships stationed in rivers and harbours throughout the nation. She was transferred to HM Customs and Excise

HM Customs and Excise (properly known as Her Majesty's Customs and Excise at the time of its dissolution) was a department of the British Government formed in 1909 by the merger of HM Customs and HM Excise; its primary responsibility was the ...

to control smuggling on the Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

coast in the navigable waterways beyond the north bank of the Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salini ...

. She was moored mid-river in the River Roach

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wate ...

which forms part of an extensive maze of waterways and marshes known as The River Crouch and River Roach Tidal River System, located around and to the south and west of Burnham-on-Crouch

Burnham-on-Crouch is a town and civil parish in the Maldon District of Essex in the East of England. It lies on the north bank of the River Crouch. It is one of Britain's leading places for yachting.

The civil parish extends east of the town t ...

. This large maritime area has a tidal coastline of , part of Essex's of coastline – the largest coastline in the United Kingdom. In 1851, oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but not al ...

companies and traders who cultivated and harvested the "Walflete" or "Walfleet" oyster ''Ostrea edulis

''Ostrea edulis'', commonly known as the European flat oyster, is a species of oyster native to Europe. In Britain and Ireland, regional names include Colchester native oyster, mud oyster, or edible oyster. In France, ''Ostrea edulis'' are known ...

'', petitioned for the Customs and Excise watch vessel ''WV-7'' (ex HMS ''Beagle'') to be removed as she was obstructing the river and its oyster-beds. In the 1851 Navy List

A Navy Directory, formerly the Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval author ...

dated 25 May, it showed her renamed ''Southend "W.V. No. 7" at Paglesham''. In 1870, she was sold to "Messrs Murray and Trainer" to be broken up.

Possible resting place

Investigations started in 2000 by a team led by Dr Robert Prescott of theUniversity of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

found documents confirming that ''"W.V. 7"'' was ''Beagle'', and noted a vessel matching her size shown midstream on the River Roach

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wate ...

(in Paglesham

Paglesham is a village and civil parish in the north east of the Rochford Rural District, Essex. The parish includes two hamlets of Eastend and Churchend, which are situated near the River Crouch and ''Paglesham Creek''. It is part of the ''Roa ...

Reach) on the 1847 hydrographic survey chart. A later chart showed a nearby indentation to the north bank of Paglesham Reach near the Eastend Wharf and near Waterside Farm. This could have been a dock for ''W.V. 7'' – ''Beagle''. Site investigations found an area of marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

y ground some deep on the tidal river-bank, about west of the boat-house. This discovery matched the chart position and many fragments of pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

of the correct period were found in the same area.  Surveys in November 2003 showed that there are the remains of substantial material within the dock that could be parts of the ship itself. An old

Surveys in November 2003 showed that there are the remains of substantial material within the dock that could be parts of the ship itself. An old anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek ἄγ ...

of 1841 pattern was excavated. It was also found that the 1871 census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

recorded a new farmhouse

FarmHouse (FH) is a social Fraternities and sororities in North America, fraternity founded at the University of Missouri on April 15, 1905. It became a national organization in 1921. Today FarmHouse has 33 active chapters and four associate ch ...

in the name of William Murray and Thomas Rainer, leading to speculation that the merchant's name was a misprint for T. Rainer. The farmhouse was demolished in the 1940s, but a nearby boathouse incorporated timbers matching knee timbers used in ''Beagle''. Two more large anchors similar to the one excavated from the ship's present location are known to have been found in neighbouring villages. It is believed that there were four anchors in the ship.

Their investigations featured in a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

programme which showed how each watch ship would have accommodated seven coastguard officers, drawn from other areas to minimise collusion with the locals. Each officer had about three rooms to house his family, forming a small community. They would use small boats to intercept smugglers, and the investigators found a causeway

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet Tra ...

giving access at low tide across the soft mud of the river bank. Apparently the next coastguard station along was ''Kangaroo'', a sister ship of ''Beagle''.

See also

* Museo Nao Victoria § HMS ''Beagle'', a full-scale replica of the vessel completed in 2016 *Beagle 2

The ''Beagle 2'' is an inoperative British Mars lander that was transported by the European Space Agency's 2003 ''Mars Express'' mission. It was intended to conduct an astrobiology mission that would have looked for evidence of past life on Mar ...

– Mars space probe, lost on 25 December 2003, named after HMS ''Beagle''

* Ship's chronometer from HMS ''Beagle''

* ''The Voyage of the Space Beagle

''The Voyage of the Space Beagle'' (1950) is a science fiction novel by Canadian-American writer A. E. van Vogt. An example of space opera subgenre, the novel is a "fix-up" compilation of four previously published stories:

*"Black Destroyer" ...

'', a science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

adventure by A. E. van Vogt

Alfred Elton van Vogt ( ; April 26, 1912 – January 26, 2000) was a Canadian-born American science fiction author. His fragmented, bizarre narrative style influenced later science fiction writers, notably Philip K. Dick. He was one of the ...

loosely inspired by Darwin's voyage aboard HMS ''Beagle''

* European and American voyages of scientific exploration

The era of European and American voyages of scientific exploration followed the Age of Discovery and were inspired by a new confidence in science and reason that arose in the Age of Enlightenment. Maritime expeditions in the Age of Discovery were ...

Notes

Sources and references

* * *. Abridged version of Darwin's ''Journal and Remarks''. * * * * * * Marquardt, Karl, ''HMS Beagle: Survey Ship Extraordinary''Conway Maritime Press

Conway Publishing, formerly Conway Maritime Press, is an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing. It is best known for its publications dealing with nautical subjects.

History

Conway Maritime Press was founded in 1972 as an independent publisher. Its o ...

, 2010.

* , Volume 1 Volume One, Volume 1, Volume I or Vol. 1 may refer to:

Albums

* ''Volume One'' (The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band album), 1966

* ''Volume One'' (Sleep album)

* ''Volume One'' (Fluff album)

* ''Volume One'' (She & Him album), 2008

* ''Volum ...

, Volume 2 Volume Two, Volume 2, Volume II or Vol. II may refer to:

* '' Vol. 2... Hard Knock Life'', a 1998 album by rapper Jay-Z

* ''Volume 2'' (Herb Alpert's Tijuana Brass album), 1963

* '' Vol. 2 (Breaking Through)'', by The West Coast Pop Art Experimenta ...

*

External links

Darwin Online – bibliography

''Proceedings'' of the first and second expeditions, and Darwin's ''Journal'' (''The Voyage of the ''Beagle). * list includes ''The Voyage of the ''Beagle *

John Lort Stokes

Admiral John Lort Stokes, RN (1 August 1811 – 11 June 1885)Although 1812 is frequently given as Stokes's year of birth, it has been argued by author Marsden Hordern that Stokes was born in 1811, citing a letter by fellow naval officer Crawford ...

''Discoveries in Australia'', Volume 1

The National Archives

National archives are central archives maintained by countries. This article contains a list of national archives.

Among its more important tasks are to ensure the accessibility and preservation of the information produced by governments, both ...

as part of the CORRAL project

* Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

, 1836''Sketch of the Surveying Voyages of his Majesty's Ships ''Adventure'' and ''Beagle'', 1825–1836. Commanded by Captains P. P. King, P. Stokes, and R. Fitz-Roy, Royal Navy''

''Journal of the Geological Society of London'' 6: 311–343

The sympiesometer of Alexander Adie

The replica HMS ''Beagle'' project

BBC News – Darwin's ''Beagle'' ship 'found'

* ttp://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/south_west/5190734.stm BBC News – Plans to build HMS ''Beagle'' replica for 2009 Darwin bicentenary.

Former official blog of the building process for the full size HMS ''Beagle'' replica.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Beagle, Hms Charles Darwin Cherokee-class brig-sloops Exploration of Western Australia Exploration ships of the United Kingdom Individual sailing vessels Brig-sloops of the Royal Navy Ships built in Woolwich 1820 ships Maritime exploration of Australia