György Lukács on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

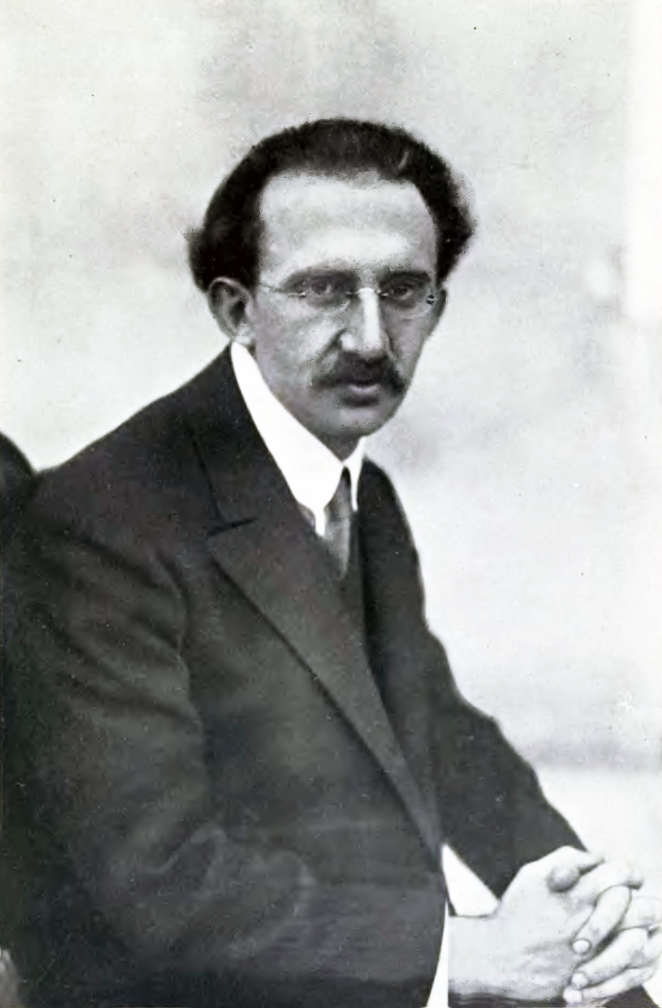

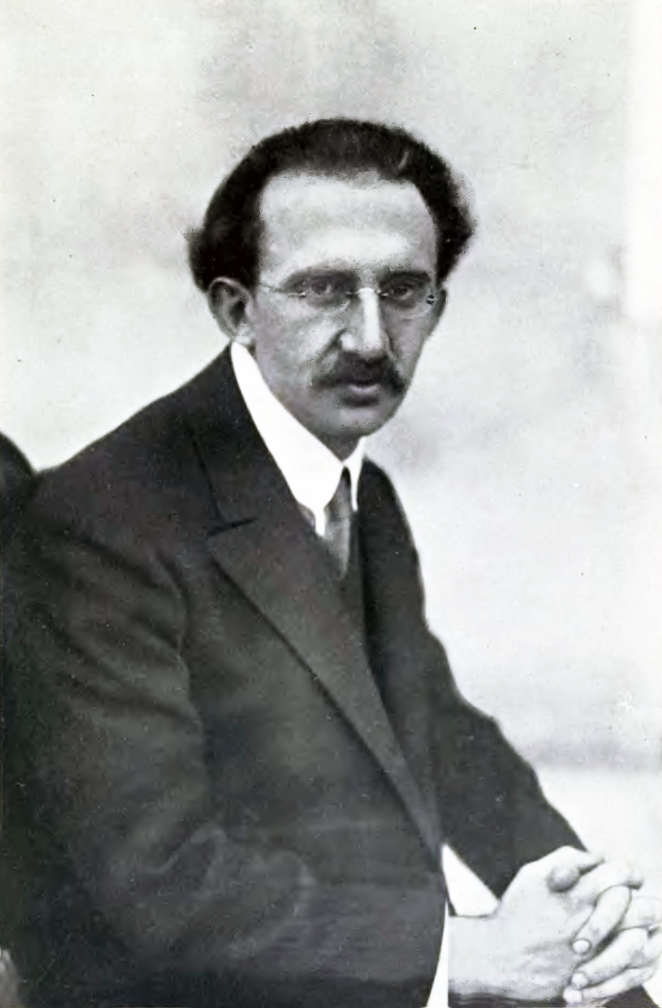

György Lukács (born György Bernát Löwinger; hu, szegedi Lukács György Bernát; german: Georg Bernard Baron Lukács von Szegedin; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, critic, and aesthetician.György Lukács – Britannica.com

/ref> He was one of the founders of

'' Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. He received his

As part of the government of the short-lived

As part of the government of the short-lived

/ref> During the

/ref> He was one of the founders of

Western Marxism

Western Marxism is a current of Marxist theory that arose from Western and Central Europe in the aftermath of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the ascent of Leninism. The term denotes a loose collection of theorists who advanced an i ...

, an interpretive tradition that departed from the Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

ideological orthodoxy of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. He developed the theory of reification, and contributed to Marxist theory with developments of Karl Marx's theory of class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

. He was also a philosopher of Leninism. He ideologically developed and organised Lenin's pragmatic revolutionary practices into the formal philosophy of vanguard-party revolution.

As a literary critic Lukács was especially influential due to his theoretical developments of realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

and of the novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

as a literary genre

A literary genre is a category of literature. Genres may be determined by literary technique, tone, content, or length (especially for fiction). They generally move from more abstract, encompassing classes, which are then further sub-divided in ...

. In 1919, he was appointed the Hungarian Minister of Culture of the government of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

(March–August 1919).

Lukács has been described as the preeminent Marxist intellectual of the Stalinist era, though assessing his legacy can be difficult as Lukács seemed both to support Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

as the embodiment of Marxist thought, and yet also to champion a return to pre-Stalinist Marxism.

Life and politics

Lukács was born Löwinger György Bernát inBudapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, to the investment banker József Löwinger (later Szegedi Lukács József; 1855–1928) and his wife Adele Wertheimer (Wertheimer Adél; 1860–1917), who were a wealthy Jewish family. He had a brother and sister. He and his family converted to Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

in 1907.

His father was knighted by the empire and received a baronial title, making Lukács a baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

as well through inheritance. As a writer, he published under the names Georg Lukács and György Lukács. Lukács participated in intellectual circles in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

and Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

.Georg Lukács'' Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. He received his

doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

in economic and political sciences ( Dr. rer. oec.) in 1906 from the Royal Hungarian University of Kolozsvár. In 1909, he completed his doctorate in philosophy at the University of Budapest

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

under the direction of Zsolt Beöthy

Zsolt Beöthy (4 September 1848 – 18 April 1922) was a Hungarian literary historian, critic, professor, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and the secretary then chairman of Kisfaludy Society. A conservative-minded literature critic, ...

.

Pre-Marxist period

Whilst at university in Budapest, Lukács was part of socialist intellectual circles through which he metErvin Szabó

Ervin Szabó (born as Samuel Armin Schlesinger; 23 August 1877 – 29 September 1918) was a Hungary, Hungarian social scientist, librarian and anarcho-syndicalist revolutionary.

Life

Born Samuel Armin Schlesinger, Szabó's parents were assimilat ...

, an anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

who introduced him to the works of Georges Sorel

Georges Eugène Sorel (; ; 2 November 1847 – 29 August 1922) was a French social thinker, political theorist, historian, and later journalist. He has inspired theories and movements grouped under the name of Sorelianism. His social and ...

(1847–1922), the French proponent of revolutionary syndicalism

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

. In that period, Lukács's intellectual perspectives were modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

and anti-positivist. From 1904 to 1908, he was part of a theatre troupe that produced modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

, psychologically realistic plays by Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

, August Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (, ; 22 January 184914 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist and painter.Lane (1998), 1040. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg wrote more than sixty p ...

, and Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Johann Robert Hauptmann (; 15 November 1862 – 6 June 1946) was a German dramatist and novelist. He is counted among the most important promoters of literary naturalism, though he integrated other styles into his work as well. He rece ...

.

He wrote the first version of this 1,000 page ''History of the Evolution of Modern Drama'' while in his early twenties, and despaired when it won a prize in 1908 because he did not think the jury was fit to judge it.

Lukács spent much time in Germany, and studied at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

from 1906 to 1907, during which time he made the acquaintance of the philosopher Georg Simmel. Later in 1913 whilst in Heidelberg, he befriended Max Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas profo ...

, Emil Lask

Emil Lask (25 September 1875 – 26 May 1915) was a German philosopher. A student of Heinrich Rickert at Freiburg University, he was a member of the Southwestern school of neo-Kantianism.

Biography

Lask was born in Austrian Galicia, as a son ...

, Ernst Bloch

Ernst Simon Bloch (; July 8, 1885 – August 4, 1977; pseudonyms: Karl Jahraus, Jakob Knerz) was a German Marxist philosopher. Bloch was influenced by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx, as well as by apocalyptic and religious thinkers ...

, and Stefan George

Stefan Anton George (; 12 July 18684 December 1933) was a German symbolist poet and a translator of Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Hesiod, and Charles Baudelaire. He is also known for his role as leader of the highly influential literary ...

. The idealist

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to id ...

system to which Lukács subscribed at this time was intellectually indebted to neo-Kantianism

In late modern continental philosophy, neo-Kantianism (german: Neukantianismus) was a revival of the 18th-century philosophy of Immanuel Kant. The Neo-Kantians sought to develop and clarify Kant's theories, particularly his concept of the "thin ...

(then the dominant philosophy in German universities) and to Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

, Søren Kierkegaard, Wilhelm Dilthey, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

. In that period, he published '' Soul and Form'' (, Berlin, 1911; tr. 1974) and ''The Theory of the Novel'' (1916/1920; tr. 1971).

After the beginning of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Lukács was exempted from military service. In 1914, he married the Russian political activist Jelena Grabenko.

In 1915, Lukács returned to Budapest, where he was the leader of the " Sunday Circle", an intellectual salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (P ...

. Its concerns were the cultural themes that arose from the existential

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

works of Dostoyevsky, which thematically aligned with Lukács's interests in his last years at Heidelberg. As a salon, the Sunday Circle sponsored cultural events whose participants included literary and musical avant-garde figures, such as Karl Mannheim

Karl Mannheim (born Károly Manheim, 27 March 1893 – 9 January 1947) was an influential Hungarian sociologist during the first half of the 20th century. He is a key figure in classical sociology, as well as one of the founders of the sociolo ...

, the composer Béla Bartók, Béla Balázs

Béla Balázs (; 4 August 1884 in Szeged – 17 May 1949 in Budapest), born Herbert Béla Bauer, was a Hungarian film critic, aesthetician, writer and poet of Jewish heritage. He was a proponent of formalist film theory.

Career

Balázs was th ...

, Arnold Hauser *Arnold Hauser (art historian)

Arnold Hauser (8 May 1892 in Timișoara – 28 January 1978 in Budapest) was a Hungarian-German art historian and sociologist who was perhaps the leading Marxist in the field. He wrote on the influence of change in ...

, Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály (; hu, Kodály Zoltán, ; 16 December 1882 – 6 March 1967) was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is well known internationally as the creator of the Kodály method of music edu ...

and Karl Polanyi

Karl Paul Polanyi (; hu, Polányi Károly ; 25 October 1886 – 23 April 1964),''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2003) vol 9. p. 554 was an Austro-Hungarian economic anthropologist and politician, best known ...

; some of them also attended the weekly salons. In 1918, the last year of the First World War (1914–1918), the Sunday Circle became divided. They dissolved the salon because of their divergent politics; several of the leading members accompanied Lukács into the Communist Party of Hungary

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

.

Pivot to communism

In the aftermath of the First World War and theRussian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, Lukács rethought his ideas. He became a committed Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

in this period and joined the fledgling Communist Party of Hungary

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

in 1918. Up until at least September 1918, he had intended to emigrate to Germany, but after being rejected from a habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in many European countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excellence in research, teaching and further education, usually including a ...

in Heidelberg, he wrote on December 16 that he had already decided to pursue a political career in Hungary instead. Lukács later wrote that he was persuaded to this course by Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napo ...

. The last publication of Lukács' pre-Marxist period was "Bolshevism as a Moral Problem", a rejection of Bolshevism on ethical grounds that he apparently reversed within days.

Communist leader

As part of the government of the short-lived

As part of the government of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

, Lukács was made People's Commissar for Education and Culture (he was deputy to the Commissar for Education Zsigmond Kunfi).

It is said by József Nádass that Lukács was giving a lecture entitled "Old Culture and New Culture" to a packed hall when the republic was proclaimed which was interrupted due to the revolution.The Conversion of Georg Lukács/ref> During the

Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

, Lukács was a theoretician of the Hungarian version of the red terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

. In an article in the Népszava

''Népszava'' (meaning "People's Word" in English) is a social-democratic Hungarian language newspaper published in Hungary.

History and profile

''Népszava'' is Hungary's eldest continuous print publication and as of October 2019 the last and ...

, 15 April 1919, he wrote that "The possession of the power of the state is also a moment for the destruction of the oppressing classes. A moment, we have to use". Lukács later became a commissar of the Fifth Division of the Hungarian Red Army

The Hungarian Ground Forces ( hu, Magyar Szárazföldi Haderő) is the land branch of the Hungarian Defence Forces, and is responsible for ground activities and troops including artillery, tanks, APCs, IFVs and ground support. Hungary's ground ...

, in which capacity he ordered the execution of eight of his own soldiers in Poroszlo, in May 1919, which he later admitted in an interview.

After the Hungarian Soviet Republic was defeated, Lukács was ordered by Kun to remain behind with Ottó Korvin

Ottó Korvin (Born Ottó Klein, 24 May 1894 in Nagybocskó – 28 December 1919 in Budapest) was a communist politician of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian B ...

, when the rest of the leadership evacuated. Lukács and Korvin's mission was to clandestinely reorganize the communist movement, but this proved to be impossible. Lukács went into hiding, with the help of photographer Olga Máté

Olga Máté (1 January 1878 – 5 April 1961) was one of the first women Hungarian photographers, most known for her portraits. She was known for her lighting techniques and used lighted backgrounds to enhance her portraits and still life compos ...

. After Korvin's capture in 1919, Lukács fled from Hungary to Vienna. He was arrested but was saved from extradition due to a group of writers including Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

and Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; 27 March 1871 – 11 March 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German author known for his socio-political novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

. Thomas Mann later based the character Naphta on Lukács in his novel ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (german: Der Zauberberg, links=no, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann, first published in German in November 1924. It is widely considered to be one of the most influential works of twentieth-century German literature.

Mann s ...

''.

He married his second wife, Gertrúd Bortstieber in 1919 in Vienna, a fellow member of the Hungarian Communist Party.

Around the 1920s, while Antonio Gramsci was also in Vienna, though they did not meet each other, Lukács met a fellow communist, Victor Serge

Victor Serge (; 1890–1947), born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich (russian: Ви́ктор Льво́вич Киба́льчич), was a Russian revolutionary Marxist, novelist, poet and historian. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks fi ...

, and began to develop Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishm ...

ideas in the field of philosophy. His major works in this period were the essays collected in his ''magnum opus'' '' History and Class Consciousness'' (, Berlin, 1923). Although these essays display signs of what Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

referred to as "left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they reg ...

" (with later Leninists calling it "ultra-leftism

The term ultra-leftism, when used among Marxist groups, is a pejorative for certain types of positions on the far-left that are extreme or uncompromising. Another definition historically refers to a particular current of Marxist communism, whe ...

"), they provided Leninism with a substantive philosophical basis. In July 1924, Grigory Zinoviev attacked this book along with the work of Karl Korsch at the Fifth Comintern Congress.

In 1925, shortly after Lenin's death, Lukács published in Vienna the short study ''Lenin: A Study in the Unity of His Thought'' (). In 1925, he published a critical review of Nikolai Bukharin's manual of historical materialism

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

.

As a Hungarian exile, he remained active on the left wing of Hungarian Communist Party, and was opposed to the Moscow-backed programme of Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napo ...

. His "Blum theses" of 1928 called for the overthrow of the counter-revolutionary regime of Admiral Horthy

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

in Hungary by a strategy similar to the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

s that arose in the 1930s. He advocated a "democratic dictatorship" of the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

and peasantry

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

as a transitional stage leading to the dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

. After Lukács's strategy was condemned by the Comintern, he retreated from active politics into theoretical work.

Lukács left Vienna in 1929 first for Berlin, then for Budapest.

Under Stalin and Rákosi

In 1930, while residing in Budapest, Lukács was summoned toMoscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. This coincided with the signing of a Viennese police order for his expulsion. Leaving their children to attend their studies, Lukács and his wife went to Moscow in March 1930. Soon after his arrival, Lukács was "prevented" from leaving and assigned to work alongside David Riazanov

David Riazanov (russian: Дави́д Ряза́нов), born David Borisovich Goldendakh (russian: Дави́д Бори́сович Гольдендах; 10 March 1870 – 21 January 1938), was a Russian revolutionary, historian, bibliographer ...

("in the basement") at the Marx–Engels Institute.

Lukács returned to Berlin in 1931 and in 1933 he once again left Berlin for Moscow to attend the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences. During this time, Lukács first came into contact with the unpublished works of the young Marx.

Lukács and his wife were not permitted to leave the Soviet Union until after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. During Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

, Lukács was sent to internal exile in Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of ...

for a time, where he and Johannes Becher

Johannes Robert Becher (, 22 May 1891 – 11 October 1958) was a German politician, novelist, and poet. He was affiliated with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) before World War II. At one time, he was part of the literary avant-garde, writi ...

became friends. Lukács survived the purges of the Great Terror

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

. There is much debate among historians concerning the extent to which Lukács accepted Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

at this period.

In 1945, Lukács and his wife returned to Hungary. As a member of the Hungarian Communist Party

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

, he took part in establishing the new Hungarian government. From 1945 Lukács was a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Between 1945 and 1946 he strongly criticised non-communist philosophers and writers. Lukács has been accused of playing an "administrative" (legal-bureaucratic) role in the removal of independent and non-communist intellectuals such as Béla Hamvas

Béla Hamvas (23 March 1897 – 7 November 1968) was a Hungarian writer, philosopher, and social critic. He was the first thinker to introduce the Traditionalist School of René Guénon to Hungary.

Biography

Béla Hamvas was born on 23 Mar ...

, István Bibó

István Bibó (7 August 1911, Budapest – 10 May 1979, Budapest) was a Hungarian lawyer, civil servant, politician and political theorist. Life

During the Hungarian Revolution he acted as the Minister of State for the Hungarian National G ...

, Lajos Prohászka

Lajos () is a Hungarian language, Hungarian masculine given name, cognate to the English Louis (given name), Louis. People named Lajos include:

Hungarian monarchs:

* Louis I of Hungary, Lajos I, 1326-1382 (ruled 1342-1382)

* Louis II of Hungary ...

, and Károly Kerényi

Károly (Carl, Karl) Kerényi ( hu, Kerényi Károly, ; 19 January 1897 – 14 April 1973) was a Hungarian scholar in classical philology and one of the founders of modern studies of Greek mythology.

Life Hungary, 1897–1943

Károly Ker ...

from Hungarian academic life. Between 1946 and 1953, many non-communist intellectuals, including Bibó, were imprisoned or forced into menial work or manual labour.

Lukács's personal aesthetic and political position on culture was always that socialist culture would eventually triumph in terms of quality. He thought it should play out in terms of competing cultures, not by "administrative" measures. In 1948–49, Lukács' position for cultural tolerance was smashed in a "Lukács purge," when Mátyás Rákosi

Mátyás Rákosi (; born Mátyás Rosenfeld; 9 March 1892

– 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian communis ...

turned his famous – 5 February 1971) was a Hungarian communis ...

salami tactics

Salami slicing tactics, also known as salami slicing, salami tactics, the salami-slice strategy, or salami attacks, is the practice of using a series of many small actions to produce a much larger action or result that would be difficult or unlawf ...

on the Hungarian Working People's Party

The Hungarian Working People's Party (, abbr. MDP) was the ruling communist party of Hungary from 1948 to 1956.

It was formed by a merger of the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) and the Social Democratic Party of Hungary (MSZDP).Neubauer, John, ...

.

In the mid-1950s, Lukács was reintegrated into party life. The party used him to help purge the Hungarian Writers' Union The Hungarian Writers Union (also known as The Free Union of Hungarian Writers) was founded in 1945 at the end of World War II. Initially the union was intended to be an organizational body through which the interests of writers in Hungary could be ...

in 1955–1956. Tamás Aczél

Tamás Aczél (; 16 December 1921 – 18 April 1994) was a Kossuth Prize-winning Hungarian poet, writer, journalist and university professor.

Career

Aczél was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1921. He graduated in his hometown in 1939, subsequentl ...

and Tibor Méray

Tibor Méray (6 April 1924 – 12 November 2020) was a Hungarian journalist and writer, worked for various newspapers (''Szabad Nép'', ''Csillag'') during the Communist regime. He was a war correspondent for ''Szabad Nép'' (official daily of th ...

(former Secretaries of the Hungarian Writers' Union) both believe that Lukács participated grudgingly, and cite Lukács leaving the presidium and the meeting at the first break as evidence of this reluctance.

De-Stalinisation

In 1956, Lukács became a minister of the brief communist revolutionary government led by Imre Nagy, which opposed the Soviet Union. At this time Lukács's daughter led a short-lived party of communist revolutionary youth. Lukács's position on the 1956 revolution was that the Hungarian Communist Party would need to retreat into a coalition government of socialists, and slowly rebuild its credibility with the Hungarian people. While a minister in Nagy's revolutionary government, Lukács also participated in trying to reform the Hungarian Communist Party on a new basis. This party, theHungarian Socialist Workers' Party

The Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party ( hu, Magyar Szocialista Munkáspárt, MSZMP) was the ruling Marxist–Leninist party of the Hungarian People's Republic between 1956 and 1989. It was organised from elements of the Hungarian Working Peo ...

, was rapidly co-opted by János Kádár

János József Kádár (; ; 26 May 1912 – 6 July 1989), born János József Czermanik, was a Hungarian communist leader and the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, a position he held for 32 years. Declining health l ...

after 4 November 1956.

During the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, Lukács was present at debates of the anti-party and revolutionary communist Petőfi Society Petőfi may refer to:

* Sándor Petőfi (1823–1849), a Hungarian poet and revolutionary

** Petőfi Bridge

** Petőfi Csarnok ("Petőfi Hall")

** ''Dem Andenken Petőfis'' ( hu, Petőfi szellemének, links=no, "In Petofi's Memory"), a piece for pia ...

while remaining part of the party apparatus. During the revolution, as mentioned in ''Budapest Diary,'' Lukács argued for a new Soviet-aligned communist party. In Lukács's view, the new party could win social leadership only by persuasion instead of force. Lukács envisioned an alliance between the dissident communist Hungarian Revolutionary Youth Party Hungarian may refer to:

* Hungary, a country in Central Europe

* Kingdom of Hungary, state of Hungary, existing between 1000 and 1946

* Hungarians, ethnic groups in Hungary

* Hungarian algorithm, a polynomial time algorithm for solving the assignme ...

, the revolutionary Hungarian Social Democratic Party and his own Soviet-aligned party as a very junior partner.

Following the defeat of the Revolution, Lukács was deported to the Socialist Republic of Romania

The Socialist Republic of Romania ( ro, Republica Socialistă România, RSR) was a Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state that existed officially in Romania from 1947 to 1989. From 1947 to 1965, the state was known as the Romanian Peop ...

with the rest of Nagy's government. Unlike Nagy, he avoided execution, albeit narrowly. Due to his role in Nagy's government, he was no longer trusted by the party apparatus. Lukács's followers were indicted for political crimes throughout the 1960s and '70s, and a number fled to the West. Lukács's books ''The Young Hegel

''The Young Hegel'' (german: Der junge Hegel: Über die Beziehungen von Dialektik und Ökonomie) is a book about the philosophical development of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel by the philosopher György Lukács. The work was completed in 1938 and p ...

'' (, Zurich, 1948) and ''The Destruction of Reason'' (, Berlin, 1954) have been used to argue that Lukács was covertly critical of Stalinism as a distortion of Marxism. In this reading, these two works are attempts to reconcile the idealism

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ide ...

of Hegelian- dialectics with the dialectical materialism of Marx and Engels, and position Stalinism as a philosophy of irrationalism

Irrationalism is a philosophical movement that emerged in the early 19th century, emphasizing the non-rational dimension of human life. As they reject logic, irrationalists argue that instinct and feelings are superior to the reason in the researc ...

.

He returned to Budapest in 1957. Lukács publicly abandoned his positions of 1956 and engaged in self-criticism. Having abandoned his earlier positions, Lukács remained loyal to the Communist Party until his death in 1971. In his last years, following the uprisings in France and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

in 1968, Lukács became more publicly critical of the Soviet Union and the Hungarian Communist Party.

In an interview just before his death, Lukács remarked:

Work

''History and Class Consciousness''

Written between 1919 and 1922 and published in 1923, Lukács's collection of essays ''History and Class Consciousness'' contributed to debates concerning Marxism and its relation tosociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of Empirical ...

, politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

and philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

. With this work, Lukács initiated the current of thought that came to be known as "Western Marxism

Western Marxism is a current of Marxist theory that arose from Western and Central Europe in the aftermath of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the ascent of Leninism. The term denotes a loose collection of theorists who advanced an i ...

". At Lukács' direction, there was no reprinting in his lifetime, making it rare and hard to acquire before 1968. Its return to prominence was aided by the social movements of the 1960s.

The most important essay in Lukács's book introduces the concept of " reification". In capitalist societies, human properties, relations and actions are transformed into properties, relations and actions of man-produced things, which become independent of man and govern his life. These man-created things are then imagined to be originally independent of man. Moreover, human beings are transformed into thing-like beings that do not behave in a human way but according to the laws of the thing-world. This essay is notable for reconstructing aspects of Marx's theory of alienation

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the estrangement (German: ''Entfremdung'') of people from aspects of their human nature (''Gattungswesen'', 'species-essence') as a consequence of the division of labor and living in a society of strati ...

before the publication of the ''Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

The ''Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844'' (german: Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte aus dem Jahre 1844), also referred to as the ''Paris Manuscripts'' (') or as the ''1844 Manuscripts'', are a series of notes written between Apri ...

'' — the work in which Marx most clearly expounds the theory.

Lukács also develops the Marxist theory of class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

- the distinction between the objective

Objective may refer to:

* Objective (optics), an element in a camera or microscope

* ''The Objective'', a 2008 science fiction horror film

* Objective pronoun, a personal pronoun that is used as a grammatical object

* Objective Productions, a Brit ...

situation of a class and that class's subjective awareness of this situation. Lukács proffers a view of a class as an "historical imputed subject". An empirically existing class can successfully act only when it becomes conscious of its historical situation, i.e. when it transforms from a "class in itself" to a "class for itself". Lukács's theory of class consciousness has been influential within the sociology of knowledge

The sociology of knowledge is the study of the relationship between human thought and the social context within which it arises, and the effects that prevailing ideas have on societies. It is not a specialized area of sociology. Instead, it dea ...

.

In his later career, Lukács repudiated the ideas of ''History and Class Consciousness'', in particular the belief in the proletariat as a " subject-object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an ...

of history" (1960 Postface to French translation). As late as 1925–1926, he still defended these ideas, in an unfinished manuscript, which he called ''Tailism and the Dialectic.'' It was not published until 1996 in Hungarian and English in 2000 under the title ''A Defence of History and Class Consciousness''.

''What is Orthodox Marxism?''

Lukács argues that methodology is the only thing that distinguishesMarxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

: even if all its substantive propositions were rejected, it would remain valid because of its distinctive method:

He criticises Marxist revisionism

Within the Marxist movement, revisionism represents various ideas, principles and theories that are based on a significant revision of fundamental Marxist premises that usually involve making an alliance with the bourgeois class.

The term ''r ...

by calling for the return to this Marxist method, which is fundamentally dialectical materialism. Lukács conceives "revisionism" as inherent to the Marxist theory, insofar as dialectical materialism is, according to him, the product of class struggle:

According to him, "The premise of dialectical materialism is, we recall: 'It is not men's consciousness that determines their existence, but on the contrary, their social existence that determines their consciousness.' ...Only when the core of existence stands revealed as a social process can existence be seen as the product, albeit the hitherto unconscious product, of human activity." (§5). In line with Marx's thought, he criticises the individualist

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relianc ...

bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

philosophy of the subject, which founds itself on the voluntary and conscious subject. Against this ideology, he asserts the primacy of social relations. Existence – and thus the world – is the product of human activity; but this can be seen only if the primacy of social process on individual consciousness is accepted. Lukács does not restrain human liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

for sociological determinism: to the contrary, this production of existence is the possibility of ''praxis

Praxis may refer to:

Philosophy and religion

* Praxis (process), the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, practised, embodied, or realised

* Praxis model, a way of doing theology

* Praxis (Byzantine Rite), the practice of fai ...

''.

He conceives the problem in the relationship between theory and practice. Lukács quotes Marx's words: "It is not enough that thought should seek to realise itself; reality must also strive towards thought." How does the thought of intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

s relate to class struggle, if theory is not simply to lag behind history, as it is in Hegel's philosophy of history ("Minerva always comes at the dusk of night...")? Lukács criticises Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Anti-Dühring'', saying that he "does not even mention the most vital interaction, namely the dialectical relation between subject and object in the historical process, let alone give it the prominence it deserves." This dialectical relation between subject and object is the basis of Lukács's critique of

'' Anti-Dühring'', saying that he "does not even mention the most vital interaction, namely the dialectical relation between subject and object in the historical process, let alone give it the prominence it deserves." This dialectical relation between subject and object is the basis of Lukács's critique of

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

's epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

, according to which the subject is the exterior, universal and contemplating subject, separated from the object.

For Lukács, "ideology" is a projection of the class consciousness of the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

, which functions to prevent the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

from attaining consciousness of its revolutionary position. Ideology determines the "form of objectivity", thus the very structure of knowledge. According to Lukács, real science must attain the "concrete totality" through which only it is possible to think the current form of objectivity as a historical period. Thus, the so-called eternal "laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vari ...

" of economics are dismissed as the ideological illusion projected by the current form of objectivity ("What is Orthodoxical Marxism?", §3). He also writes: "It is only when the core of being has showed itself as social becoming, that the being itself can appear as a product, so far unconscious, of human activity, and this activity, in turn, as the decisive element of the transformation of being." ("What is Orthodoxical Marxism?", §5) Finally, "orthodoxical Marxism" is not defined as interpretation of ''Capital'' as if it were the Bible or an embrace of "marxist thesis", but as fidelity to the "marxist method", dialectics.

''Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat''

Drawing from the insights ofMax Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas profo ...

and Georg Simmel and Marx's magnum opus '' Capital'', as well as Hegel's concept of appearance, Lukács argues that commodity fetishism

In Marxist philosophy, the term commodity fetishism describes the economic relationships of production and exchange as being social relationships that exist among things (money and merchandise) and not as relationships that exist among people ...

is the central structural problem of capitalist society. The essence of the commodity structure is that a relation between people takes on the character of a thing. Society subordinates production entirely to the increase of exchange-value

In political economy and especially Marxian economics, exchange value (German: ''Tauschwert'') refers to one of the four major attributes of a commodity, i.e., an item or service produced for, and sold on the market, the other three attributes be ...

and crystallises relations between human beings in to object-values. The commodity's fundamental nature is concealed: it appears to have autonomy and acquires a phantom objectivity.

There are two sides to commodity fetishism: "Objectively a world of objects and relations between things springs into being (the world of commodities and their movements on the market) Subjectively - where the market economy has been fully developed - a man's activity becomes estranged from himself, it turns into a commodity which, subject to the non-human objectivity of the natural laws of society, must go its own way independently of man just like any consumer article." A man is no longer a specific individual but part of a huge system of production and exchange. He is a mere unit of labour power

Labour power (in german: Arbeitskraft; in french: force de travail) is a key concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of capitalist political economy. Marx distinguished between the capacity to do work, labour power, from the physical act of w ...

, an article to be bought and sold according to the laws of the market. The rationalisation of the productive mechanism based on what is and can be calculated extends to all fields, including human consciousness. Legal systems disregard tradition and reduce individuals to juridical units. Division of labour becomes increasingly specialised and particularised, confining the individual's productive activity to a narrower and narrower range of skills.

As the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

plays the dominant role in this system, it is contrary to its own interests to understand the system's transient historical character. Bourgeois consciousness is mystified. Bourgeois philosophy understands only empirical reality or normative ethics; it lacks the cognitive ability to grasp reality as a whole. Bourgeois rationalism has no interest in phenomena beyond what is calculable and predictable. Only the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

, which has no interest in the maintenance of capitalism, can relate to reality in a practical revolutionary way. When the proletariat becomes aware of its situation as a mere commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a comm ...

in bourgeois society, it will be able to understand the social mechanism as a whole. The self-knowledge of the proletariat is more than just a perception of the world; it is a historical movement of emancipation, a liberation of humanity from the tyranny of reification.

Lukács saw the destruction of society as a proper solution to the "cultural contradiction of the epoch". In 1969 he cited:“Even though my ideas were confused from a theoretical point of view, I saw the revolutionary destruction of society as the one and only solution to the cultural contradictions of the epoch. Such a worldwide overturning of values cannot take place without the annihilation of the old values.

Literary and aesthetic work

In addition to his standing as a Marxist political thinker, Lukács was an influential literary critic of the twentieth century. His important work in literary criticism began early in his career, with ''The Theory of the Novel'', a seminal work inliterary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, mo ...

and the theory of genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

. The book is a history of the novel as a form, and an investigation into its distinct characteristics. In ''The Theory of the Novel'', he coins the term "transcendental homelessness Transcendental homelessness (german: transzendentale Obdachlosigkeit) is a philosophical term coined by George Lukács in his 1914–15 essay ''Theory of the Novel''. Lukács quotes Novalis at the top of the essay, "Philosophy is really homesickness ...

", which he defines as the "longing of all souls for the place in which they once belonged, and the 'nostalgia… for utopian perfection, a nostalgia that feels itself and its desires to be the only true reality'". Lukács maintains that "the novel is the necessary epic form of our time."

Lukács later repudiated ''The Theory of the Novel'', writing a lengthy introduction that described it as erroneous, but nonetheless containing a "romantic anti-capitalism" which would later develop into Marxism. (This introduction also contains his famous dismissal of Theodor Adorno

Theodor is a masculine given name. It is a German form of Theodore. It is also a variant of Teodor.

List of people with the given name Theodor

* Theodor Adorno, (1903–1969), German philosopher

* Theodor Aman, Romanian painter

* Theodor Blue ...

and others in Western Marxism as having taken up residence in the "Grand Hotel Abyss".)

Lukács's later literary criticism includes the well-known essay "Kafka or Thomas Mann?", in which Lukács argues for the work of Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

as a superior attempt to deal with the condition of modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the " ...

, and criticises Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It ...

's brand of modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

. Lukács steadfastly opposed the formal innovations of modernist writers like Kafka, James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

, and Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish novelist, dramatist, short story writer, theatre director, poet, and literary translator. His literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal and tragicomic expe ...

, preferring the traditional aesthetic of realism.

During his time in Moscow in the 1930s, Lukács worked on Marxist views of aesthetics while belonging to the group around an influential Moscow magazine "The Literary Critic" (). The editor of this magazine, Mikhail Lifshitz

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Lifshitz (russian: Михаи́л Алекса́ндрович Ли́фшиц; 23 July 1905 in Melitopol (Taurida Governorate, now Zaporizhzhia Oblast of Ukraine) – 20 September 1983 in Moscow) was a Soviet Marxian litera ...

, was an important Soviet author on aesthetics. Lifshitz' views were very similar to Lukács's insofar as both argued for the value of the traditional art; despite the drastic difference in age (Lifschitz was much younger) both Lifschitz and Lukács indicated that their working relationship at that time was a collaboration of equals. Lukács contributed frequently to this magazine, which was also followed by Marxist art theoreticians around the world through various translations published by the Soviet government.

The collaboration between Lifschitz and Lukács resulted in the formation of an informal circle of the like-minded Marxist intellectuals connected to the journal Literaturnyi KritikLukács famously argued for the revolutionary character of the novels ofhe Literary Critic He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...published monthly starting in the summer of 1933 by the Organisational Committee of the Writers' Union. ... A group of thinkers formed around Lifschitz, Lukács andAndrei Platonov Andrei Platonov (russian: Андре́й Плато́нов, ; – 5 January 1951) was the pen name of Andrei Platonovich Klimentov (russian: Андре́й Плато́нович Климе́нтов), a Soviet Russian writer, philosopher, pla ...; they were concerned with articulating the aesthetical views of Marx and creating a kind of Marxist aesthetics that had not yet been properly formulated.

Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy' ...

and Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honoré Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-François Balssa, père d'Honoré de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Comédie humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

. Lukács felt that both authors' nostalgic, pro-aristocratic politics allowed them accurate and critical stances because of their opposition (albeit reactionary) to the rising bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

. This view was expressed in his later book ''The Historical Novel'' (published in Russian in 1937, then in Hungarian in 1947), as well as in his essay " Realism in the Balance" (1938).

''The Historical Novel'' is probably Lukács's most influential work of literary history. In it he traces the development of the genre of historical fiction. While prior to 1789, he argues, people's consciousness of history was relatively underdeveloped, the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars that followed brought about a realisation of the constantly changing, evolving character of human existence. This new historical consciousness was reflected in the work of Sir Walter Scott, whose novels use 'representative' or 'typical' characters to dramatise major social conflicts and historical transformations, for example the dissolution of feudal society in the Scottish Highlands and the entrenchment of mercantile capitalism. Lukács argues that Scott's new brand of historical realism Historical realism is a writing style or subgenre of realistic fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary, or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals a ...

was taken up by Balzac and Tolstoy, and enabled novelists to depict contemporary social life not as a static drama of fixed, universal types, but rather as a moment of history, constantly changing, open to the potential of revolutionary transformation. For this reason he sees these authors as progressive and their work as potentially radical, despite their own personal conservative politics.

For Lukács, this historical realist tradition began to give way after the 1848 revolutions, when the bourgeoisie ceased to be a progressive force and their role as agents of history was usurped by the proletariat. After this time, historical realism begins to sicken and lose its concern with social life as inescapably historical. He illustrates this point by comparing Flaubert's historical novel ''Salammbô

''Salammbô'' (1862) is a historical novel by Gustave Flaubert. It is set in Carthage immediately before and during the Mercenary Revolt (241–237 BCE). Flaubert's principal source was Book I of the ''Histories'', written by the Greek hist ...

'' to that of the earlier realists. For him, Flaubert's work marks a turning away from relevant social issues and an elevation of style over substance. Why he does not discuss ''Sentimental Education

''Sentimental Education'' (French: ''L'Éducation sentimentale'', 1869) is a novel by Gustave Flaubert. Considered one of the most influential novels of the 19th century, it was praised by contemporaries such as George Sand and Émile Zola, but ...

'', a novel much more overtly concerned with recent historical developments, is not clear. For much of his life Lukács promoted a return to the realist tradition that he believed had reached its height with Balzac and Scott, and bemoaned the supposed neglect of history that characterised modernism.

''The Historical Novel'' has been hugely influential in subsequent critical studies of historical fiction, and no serious analyst of the genre fails to engage at some level with Lukács's arguments.

Critical and socialist realism

Lukács defined realistic literature as literature capable of relating human life to the totality. He distinguishes between two forms of realism,critical

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

*Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing in ...

and socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. Lukács argued that it was precisely the desire for a realistic depiction of life that enabled politically reactionary writers such as Balzac, Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

and Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

to produce great, timeless and socially progressive works. According to Lukács, there is a contradiction between worldview and talent among such writers. He greatly valued the comments made in that direction by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

on Tolstoy and especially by Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

''

''

Balzac boldly exposed the contradiction of nascent capitalist society and hence his observation of reality constantly clashed with his political prejudices. But as an honest artist he always depicted only what he himself saw, learned and underwent, concerning himself not at all whether his-true-to-life description of the things he saw contradicted his pet ideas.

Critical realists include writers who could not rise to the

"Imre Nagy aka 'Volodya' – A Dent in the Martyr's Halo?"

"Cold War International History Project Bulletin", no. 5 (Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, Washington, DC), Spring, 1995, pp. 28, and 34–37. * Granville, Johanna, "The First Domino: International Decision Making During the Hungarian Crisis of 1956", Texas A & M University Press, 2004. * Heller, Agnes, 1983. ''Lukacs Revalued''.

Lukács, György (2001) "Realism in the Balance." In, Vincent B. Leitch (ed.). ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism''. New York: Norton. pp. 1033-1058.

* * Meszaros, Istvan, 1972. ''Lukács' Concept of Dialectic''. London: The Merlin Press. * Muller, Jerry Z., 2002. ''The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought''.

''Georg Lukács Archive''

Marxists website

, Johns Hopkins University Press

Georg Lukács

'' Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' *

Bendl Júlia, "Lukács György élete a századfordulótól 1918-ig"

Lukács and Imre Lakatos

''Georg Lukács Archive''

Libertarian Communist Library * Múlt-kor Történelmi portál (''Past-Age Historic Portal'')

Lukács György was born 120 years ago

''Other Voices'', Vol.1 no.1, 1998.

''New Politics,'' 2001, Issue 30 * Realism in the Balance {{DEFAULTSORT:Lukacs, Gyoergy 1885 births 1971 deaths 20th-century essayists 20th-century Hungarian philosophers Burials at Kerepesi Cemetery Continental philosophers Cultural critics Culture ministers of Hungary Education ministers of Hungary Epistemologists Founders of philosophical traditions Government ministers of Hungary Hegelian philosophers Hungarian Communist Party politicians Hungarian essayists Hungarian Jews Hungarian literary critics Hungarian Marxists Hungarian nobility Hungarian philosophers Jewish philosophers Jewish socialists Literary theorists Marxist humanists Marxist theorists Hungarian Marxist writers Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin Members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Members of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party Members of the Hungarian Working People's Party Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1949–1953) Members of the National Assembly of Hungary (1953–1958) Metaphysicians Ontologists People of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 Philosophers of art Philosophers of culture Philosophers of education Philosophers of literature Philosophers of social science Political philosophers Philosophy writers Social critics Social philosophers Writers from Budapest

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

worldview, but despite this tried to truthfully reflect the conflicts of the era, not content with the direct description of single events. A great story speaks through individual human destinies in their work. Such writers are not naturalists, allegorists and metaphysicians. They do not flee from the world into the isolated human soul and do not seek to raise its experiences to the rank of timeless, eternal and irresistible properties of human nature. Balzac, Tolstoy, Anatole France

(; born , ; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters. He was a member of the Académie França ...

, Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland (; 29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 "as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production a ...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, Lion Feuchtwanger

Lion Feuchtwanger (; 7 July 1884 – 21 December 1958) was a German Jewish novelist and playwright. A prominent figure in the literary world of Weimar Germany, he influenced contemporaries including playwright Bertolt Brecht.

Feuchtwanger's J ...

and Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

are the brightest writers from the gallery of critical realists.

Lukács notes that realistic art is usually found either in highly developed countries or in countries undergoing a period of rapid socio-economic development, yet it is possible that backward countries often give rise to advanced literature precisely because of their backwardness, which they seek to overcome by artistic means. Lukács (together with Lifshitz Lifshitz (or Lifschitz) is a surname, which may be derived from the Polish city of Głubczyce (German: Leobschütz).

The surname has many variants, including: , , Lifshits, Lifshuts, Lefschetz; Lipschitz ( Lipshitz), Lipshits, Lipchitz, Lips ...

) polemicized against the "vulgar sociological" thesis then dominant in Soviet literary criticism. The "vulgar sociologists" (associated with the former RAPP) prioritized class origin as the most important determinant for an artist and his work, categorizing artists and artistic genres as "feudal", "bourgeois", "petty-bourgeois" etc. Lukács and Lifshitz sought to prove that such great artists as Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

, Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-emin ...

, Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

or Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

were able to rise above their class worldview by grasping the dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

of individual and society in its totality and depicting their relations truthfully.

All modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

art - avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

, naturalism, expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

, surrealism, etc. - is the opposite of realism. This is decadent

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members of ...

art, examples of which are the works of Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It typi ...

, Joyce, Musil

Musil (feminine Musilová) is a Czech surname, which means "he had to", from the past tense of the Czech word ''musit'' (must).''Dictionary of American Family Names''"Musil Family History" Oxford University Press, 2013. Retrieved on 9 January 2016. ...

, Beckett, etc. The main shortcoming of modernism, which predicts its inevitable defeat, is the inability to perceive the totality and carry out the act of mediation. One cannot blame the writer for describing loneliness, but one must show it in such a way that it is clear to everyone: human loneliness is an inevitable consequence of capitalist