The Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine (german: link=no, Großherzogtum Hessen und bei Rhein) was a

grand duchy

A grand duchy is a sovereign state, country or territory whose official head of state or ruler is a monarch bearing the title of grand duke or grand duchess.

Relatively rare until the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the term was oft ...

in western Germany that existed from 1806 to 1918. The Grand Duchy originally formed from the

Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Darmstadt) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse betwee ...

in 1806 as the Grand Duchy of Hesse (german: Großherzogtum Hessen, link=no). It assumed the name Hesse and bei Rhein in 1816 to distinguish itself from the

Electorate of Hesse

The Electorate of Hesse (german: Kurfürstentum Hessen), also known as Hesse-Kassel or Kurhessen, was a landgraviate whose prince was given the right to elect the Emperor by Napoleon. When the Holy Roman Empire was abolished in 1806, its prin ...

, which had formed from neighbouring

Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, was a state in the Holy Roman Empire that was directly subject to the Emperor. The state was created in 1567 when the Lan ...

. Colloquially, the grand duchy continued to be known by its former name of Hesse-Darmstadt.

In 1806, the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt seceded from the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

and joined

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's new

Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria an ...

. The country was promoted to the status of Grand Duchy and received considerable new territories, principally the

Duchy of Westphalia

The Duchy of Westphalia (german: Herzogtum Westfalen) was a historic territory in the Holy Roman Empire, which existed from 1102 to 1803. It was located in the greater region of Westphalia, originally one of the three main regions in the Germa ...

. After the French defeat in 1815, the Grand Duchy joined the new

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

. Westphalia was taken by Prussia, but Hesse received Rheine-Hesse in return. A constitution was proclaimed in 1820 and a long process of legal reforms were begun, with the aim of unifying the disparate territories under the Grand Duke's control. The political history of the Grand Duchy during this period was characterised by conflict between the conservative

mediatised houses

The mediatised houses (or mediatized houses, german: Standesherren) were ruling princely and comital-ranked houses that were mediatised in the Holy Roman Empire during the period 1803–1815 as part of German mediatisation, and were later recognise ...

(''Standesherren'') and forces supporting political and social

liberalisation

Liberalization or liberalisation (British English) is a broad term that refers to the practice of making laws, systems, or opinions less severe, usually in the sense of eliminating certain government regulations or restrictions. The term is used m ...

. During the

1848 revolutions

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europe ...

, the government was forced to grant wide-ranging reforms, including the full abolition of serfdom and universal manhood suffrage, but the reactionary government of

Reinhard von Dalwigick Reinhard is a German, Austrian, Danish, and to a lesser extent Norwegian surname (from Germanic ''ragin'', counsel, and ''hart'', strong), and a spelling variant of Reinhardt.

Persons with the given name

*Reinhard of Blankenburg (after 1107 – 11 ...

rolled most of these back over the following decade. In 1866, Hesse entered the

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

on the Austrian side, but received a relatively mild settlement from the Prussian victors. The Grand Duchy joined the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in 1871. As a small state within the Empire, the Grand Duchy had limits placed on its autonomy, but significant religious, social, and cultural reforms were carried out. During the

November Revolution after

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1918, the Grand Duchy was overthrown and replaced by the

People's State of Hesse

The People's State of Hesse (german: Volksstaat Hessen) was one of the constituent states of Weimar Republic, Germany from 1918 to 1945, as the successor to the Grand Duchy of Hesse (german: Großherzogtum Hessen) after the defeat of the German ...

.

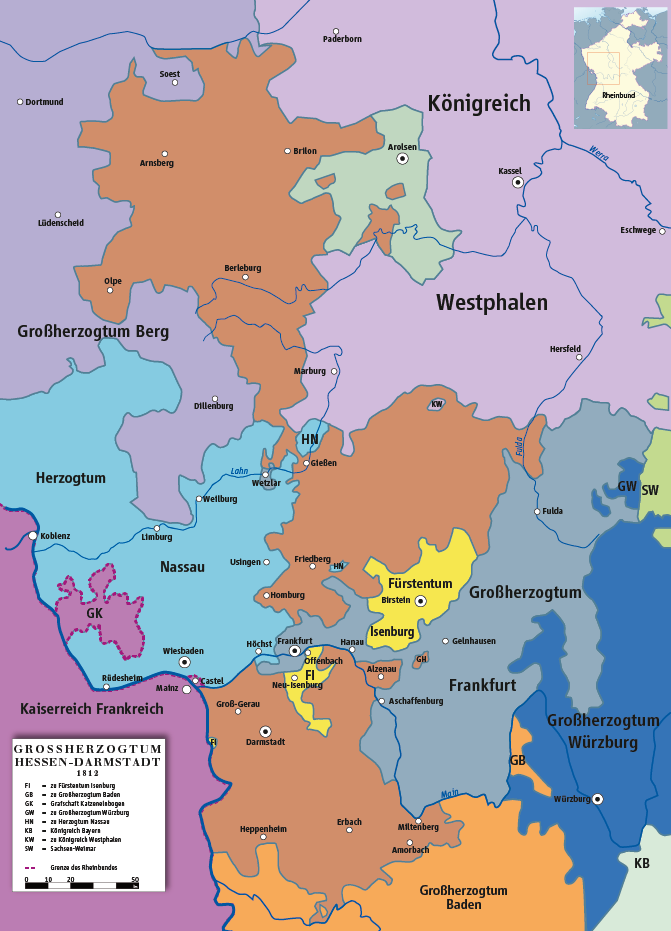

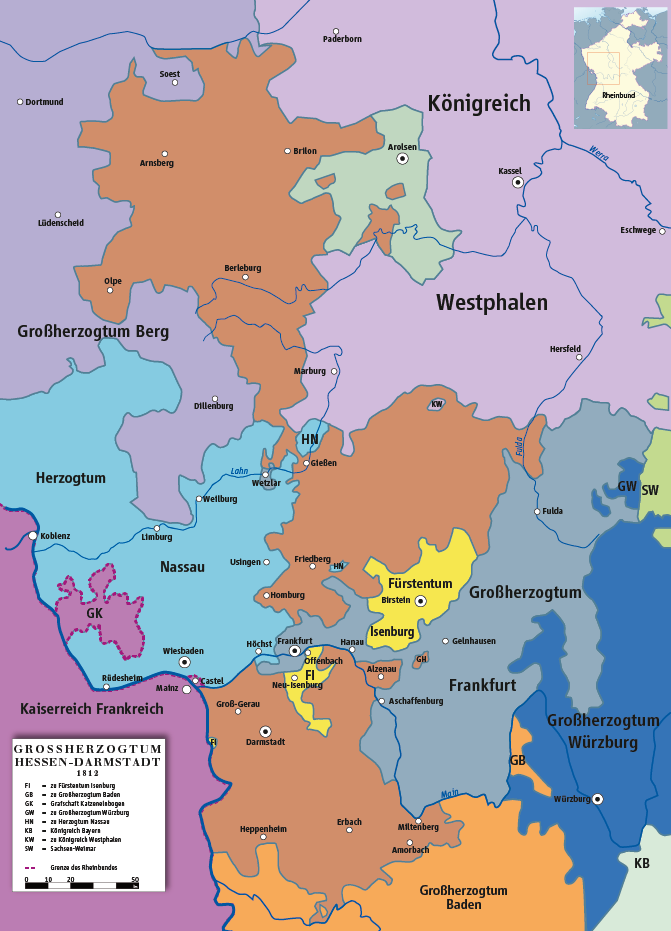

Geography

The portion of the Grand Duchy on the right bank of the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

stretched most of the way from the south of the modern state of

Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a States of Germany, state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major histor ...

to

Frankenberg. The portion on the left bank was located in the modern state of

Rhineland-Palatinate

Rhineland-Palatinate ( , ; german: link=no, Rheinland-Pfalz ; lb, Rheinland-Pfalz ; pfl, Rhoilond-Palz) is a western state of Germany. It covers and has about 4.05 million residents. It is the ninth largest and sixth most populous of the ...

. In addition to the great floodplains of the Rhine (

Hessian Ried

The Hessian Ried (german: Hessische Ried) is a low-lying, agricultural region that forms part of the northeastern area of the Upper Rhine Plain. It is situated in South Hesse in west central Germany.

Location and description

The Hessian Ried lie ...

),

Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

, and

Wetterau

The Wetterau is a fertile undulating tract, watered by the Wetter, a tributary of the Nidda River, in the western German state of Hesse, between the hilly province Oberhessen and the north-western Taunus mountains.

Bettina von Arnim writes of We ...

, the Grand Duchy also contained upland regions like the

Vogelsberg

The is a large volcanic mountain range in the German Central Uplands in the state of Hesse, separated from the Rhön Mountains by the Fulda river valley.

Emerging approximately 19 million years ago, the Vogelsberg is Central Europe's larges ...

, the

Hessian Hinterland

The land known as the Hessian Hinterland (german: Hessisches Hinterland) lies within the region of Middle Hesse and is concentrated around the old county of Biedenkopf, that is the western part of the present county of Marburg-Biedenkopf, as well ...

, and the

Odenwald

The Odenwald () is a low mountain range in the German states of Hesse, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg.

Location

The Odenwald is located between the Upper Rhine Plain with the Bergstraße and the ''Hessisches Ried'' (the northeastern section ...

. In the south, the

exclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

s of the extended into the

Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden (german: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in the southwest German Empire on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.

It came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subs ...

.

Physical geography and population

The territory consisted of two separate areas: the of

Upper Hesse

The term Upper Hesse (german: Provinz Oberhessen) originally referred to the southern possessions of the Landgraviate of Hesse, which were initially geographically separated from the more northerly Lower Hesse by the .

Later, it became the name of ...

in the north and the provinces of

Starkenburg

Starkenburg is an historical region in the State of Hesse, Germany, comprising the area south of the Main River and east of the Rhine, around the regional capital Darmstadt.

Geography

The region is named after Starkenburg Castle, above Heppen ...

and

Rhenish Hesse

Rhenish Hesse or Rhine HesseDickinson, Robert E (1964). ''Germany: A regional and economic geography'' (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p. 542. . (german: Rheinhessen) is a region and a former government district () in the German state of Rhineland- ...

in the south, as well as a number of much smaller exclaves. The northern and southern sections were separated by a narrow stretch of territory, which belonged to

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

after 1866 and before that to

Duchy of Nassau

The Duchy of Nassau (German: ''Herzogtum Nassau'') was an independent state between 1806 and 1866, located in what is now the German states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse. It was a member of the Confederation of the Rhine and later of the G ...

, the

Free City of Frankfurt

For almost five centuries, the German city of Frankfurt was a city-state within two major Germanic entities:

*The Holy Roman Empire as the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt () (until 1806)

*The German Confederation as the Free City of Frankfurt ...

, and the

Electorate of Hesse

The Electorate of Hesse (german: Kurfürstentum Hessen), also known as Hesse-Kassel or Kurhessen, was a landgraviate whose prince was given the right to elect the Emperor by Napoleon. When the Holy Roman Empire was abolished in 1806, its prin ...

. About 25% of the land area was forested. The two sections had very different characters:

;Upper Hesse

Upper Hesse was the largest of the three provinces by area. Most of this territory was forested uplands of the Vogelsberg and the Hessian Hinterland. Only a small portion was part of the fertile Wetterau, where there were also

brown coal

Lignite, often referred to as brown coal, is a soft, brown, combustible, sedimentary rock formed from naturally compressed peat. It has a carbon content around 25–35%, and is considered the lowest rank of coal due to its relatively low heat ...

deposits. There were many streams and waterways in the area, but none of them were big enough to serve as transport routes.

Agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

brought only low yields, while there was no industry at all. This led to increasing poverty over the course of the 19th century and massive

emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

to the established industrial centres in Germany and overseas. While Upper Hesse was also the largest province by population at the start of the 19th century, by the end of the Grand Duchy in 1918 it had become the smallest. The only significant institution which was based here was the

University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (german: Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is named after its most famous faculty member, Justus von L ...

.

;Starkenburg and Rhine-Hesse

Starkenburg and Rhine-Hesse were totally different. They lay almost entirely on the banks of the Rhine (except for the Odenwald, which faced similar structural problems to the Vogelsberg). Intensive agriculture was possible and profitable in many areas of these plains, such as

fruit growing on the

Bergstraße and

viticulture

Viticulture (from the Latin word for ''vine'') or winegrowing (wine growing) is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of ''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine, ran ...

in Rhine-Hesse. There were two large navigable rivers, the Rhine and the Main, which were the most important transportation routes until the development of the

railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

. Burgeoning industry developed in this region. The three major centres of the Grand Duchy were located here: the capital at

Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it th ...

, the largest industrial centre at

Offenbach am Main

Offenbach am Main () is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Hesse, Germany, on the left bank of the river Main (river), Main. It borders Frankfurt and is part of the Frankfurt urban area and the larger Frankfurt Rhein-Main Regional Aut ...

, and

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

which was the largest city and the most significant centre for trade.

Political geography

The Grand Duchy was divided into three provinces:

*

Starkenburg

Starkenburg is an historical region in the State of Hesse, Germany, comprising the area south of the Main River and east of the Rhine, around the regional capital Darmstadt.

Geography

The region is named after Starkenburg Castle, above Heppen ...

(capital at

Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it th ...

): Right bank of the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

, south of the

Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

.

*

Rhenish Hesse

Rhenish Hesse or Rhine HesseDickinson, Robert E (1964). ''Germany: A regional and economic geography'' (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p. 542. . (german: Rheinhessen) is a region and a former government district () in the German state of Rhineland- ...

(capital at

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

): Left bank of the Rhine, territory gained from the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

.

*

Upper Hesse

The term Upper Hesse (german: Provinz Oberhessen) originally referred to the southern possessions of the Landgraviate of Hesse, which were initially geographically separated from the more northerly Lower Hesse by the .

Later, it became the name of ...

(capital at

Giessen

Giessen, spelled Gießen in German (), is a town in the German state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of both the district of Giessen and the administrative region of Giessen. The population is approximately 90,000, with roughly 37,000 univers ...

): North of the Main, separated from Starkenburg by the

Free City of Frankfurt

For almost five centuries, the German city of Frankfurt was a city-state within two major Germanic entities:

*The Holy Roman Empire as the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt () (until 1806)

*The German Confederation as the Free City of Frankfurt ...

.

The neighbouring states were:

* The Prussian

Rhine Province

The Rhine Province (german: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia () or synonymous with the Rhineland (), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. It ...

, the Duchy of Nassau (part of Prussia after 1866), and the Prussian

Province of Westphalia

The Province of Westphalia () was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia from 1815 to 1946. In turn, Prussia was the largest component state of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918, of the Weimar Republic and from 1918 ...

to the west;

* The Electorate of Hesse (also part of Prussia from 1866) to the north and northeast;

* The

Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria (german: Königreich Bayern; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1805 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German E ...

to the east;

* The

Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden (german: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in the southwest German Empire on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.

It came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subs ...

to the south;

*

Kürnbach

Kürnbach is a municipality in the district of Karlsruhe in southwestern Baden-Württemberg. This historic wine village features half timbered houses and lies around 60 kilometers northwest of Stuttgart. The village was once owned by two states a ...

was governed as a

condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

with Baden until 1905;

* The Bavarian province of

Palatinate to the southwest;

* The two main regions of the Grand Duchy were separated by the Free City of Frankfurt and the Electorate of Hesse (parts of Prussia after 1866)

* The long northern region of and the Hessian Hinterland was linked to the rest of Upper Hesse by a corridor of land only 500 metres wide at

Heuchelheim

Heuchelheim (official name: ''Heuchelheim a. d. Lahn'') is a municipality in the district of Gießen, in Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. ...

, which was surrounded on both sides by , an exclave of the Prussian Rhine Province.

There were also a number of Hessian exclaves to the north and south:

* The exclave of was sandwiched between the Electorate of Hesse and the

Principality of Waldeck and Pyrmont

The County of Waldeck (later the Principality of Waldeck and Principality of Waldeck and Pyrmont) was a state of the Holy Roman Empire and its successors from the late 12th century until 1929. In 1349 the county gained Imperial immediacy and in 1 ...

, while

Eimelrod und

Höringhausen were inside Waldeck;

* The exclave of

Wimpfen

Bad Wimpfen () is a historic spa town in the district of Heilbronn in the Baden-Württemberg region of southern Germany. It lies north of the city of Heilbronn, on the river Neckar.

Geography

Bad Wimpfen is located on the west bank of the Riv ...

was sandwiched between Baden and the

Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg (german: Königreich Württemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which exist ...

;

* Another exclave, made up of half the town of

Helmhof, was located inside Baden;

, which belonged to the Electorate of Hesse, was an

enclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

within the Grand Duchy until 1866, when it was given to the Grand Duchy.

Hesse-Homburg

Hesse-Homburg was formed into a separate landgraviate in 1622 by the landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt; it was to be ruled by his son, although it did not become independent of Hesse-Darmstadt until 1668. It was briefly divided into Hesse-Homburg and ...

was inherited by the Grand Duke of Hesse in 1866, but had to be ceded to Prussia later that same year. The Biedenkopf district and the Hessian Hinterland were also annexed by Prussia in 1866. These territories were combined with Electoral Hesse, the Duchy of Nassau, and Frankfurt to create the new Prussian

Province of Hesse-Nassau

The Province of Hesse-Nassau () was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1868 to 1918, then a province of the Free State of Prussia until 1944.

Hesse-Nassau was created as a consequence of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 by combining the p ...

in 1868.

History

1806 establishment

During the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

,

Louis X Louis X may refer to:

* Louis X of France, "the Quarreller" (1289–1316).

* Louis X, Duke of Bavaria (1495–1545)

* Louis I, Grand Duke of Hesse (1753–1830).

* Louis Farrakhan (formerly Louis X), head of the Nation of Islam

{{hndis ...

, Landgrave of

Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Darmstadt) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse betwee ...

, initially sought

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n protection against

Napoleonic France

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eur ...

, but after the

Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in ...

, this policy became untenable. At the last minute, Louis X switched sides and supplied troops to

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. Along with fifteen other states, the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt left the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

and joined the

Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria an ...

. The

Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Darmstadt) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse betwee ...

was promoted to a

Grand Duchy

A grand duchy is a sovereign state, country or territory whose official head of state or ruler is a monarch bearing the title of grand duke or grand duchess.

Relatively rare until the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the term was oft ...

and Louis X thereafter styled himself Grand Duke Louis I (german: Großherzog Ludewig I., with an extra 'e') and announced not only the promotion, but also the territories he had received under the

Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria an ...

in an edict on 13 August 1806. Along with the promotion to the rank of Grand Duchy, Hesse was also rewarded with territorial gains, such as the

Electorate of Cologne

The Electorate of Cologne (german: Kurfürstentum Köln), sometimes referred to as Electoral Cologne (german: Kurköln, links=no), was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that existed from the 10th to the early 19th century. ...

. However, although all this territory lay under his

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

, the princes who had previously held these territories, the

mediatised houses

The mediatised houses (or mediatized houses, german: Standesherren) were ruling princely and comital-ranked houses that were mediatised in the Holy Roman Empire during the period 1803–1815 as part of German mediatisation, and were later recognise ...

, retained a significant portion of their former powers.

Before this territorial expansion, the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt had around 210,000 inhabitants in its territories on the right bank of the Rhine. After 1806, the population was around 546,000. At the same time, the Grand Duchy reached its greatest territorial extent, around 9,300 km². Almost simultaneously, there was a radical change in the state's internal politics. With two edicts on 1 October 1806, the Grand Duke revoked the financial privileges of the landed nobility on a large scale (the landed nobility became subject to taxation

[The mediatised houses were more fortunate, since they were granted a 1/3 tax deduction owing to the privileged status awarded to them in the Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine (Franz/Fleck/Kallenberg: ''Großherzogtum Hessen'', pp. 709 f.)]) and their

Landstände

The ''Landstände'' (singular ''Landstand'') or ''Landtage'' (singular ''Landtag'') were the various territorial estates or diets in the Holy Roman Empire in the Middle Ages and the early modern period, as opposed to their respective territorial ...

(feudal estates) were abolished, which transformed Hesse-Darmstadt "from a mosaic of patrimonial fragments into a centralized, absolute monarchy".

Developments after 1806

On 24 April 1809, Napoleon ordered the abolition of the

Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

, amalgamating

Kloppenheim and into the Grand Duchy.

Between 1808 and 1810, there were plans to introduce the

Napoleonic Code as only valid law for the whole Grand Duchy. However, these discussions were terminated by the conservative government of , which was opposed to social changes.

On 11 May 1810, the Grand Duchy and the French Empire concluded a treaty, which granted the Grand Duchy further areas under French control, which had been taken from Electoral Hesse in 1806. Although the treaty was agreed in May, it was only signed by Napoleon on 17 October 1810. The Hessian certificate of possession is dated 10 November 1810. The Babenhausen district was attached to Strakenburg province, the other territories to Upper Hesse.

In August 1810, there was a three-way agreement between France, Hesse, and the

Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden (german: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in the southwest German Empire on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.

It came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subs ...

. Baden placed its territories at French disposal and France gave them back to the Grand Duchy with a treaty signed on 11 November 1810. The Hessian certificate of possession is dated 13 November 1810.

The Congress of Vienna (1815)

At the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815, the Grand Duchy joined the

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

and received a portion of the former

Mont-Tonnerre

Mont-Tonnerre was a department of the First French Republic and later the First French Empire in present-day Germany. It was named after the highest point in the Palatinate, the ''Donnersberg'' ("Thunder Mountain", possibly referring to Donar, ...

department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

, which had a population of 140,000 people and included the important federal

fortress at Mainz, as compensation for the

Duchy of Westphalia

The Duchy of Westphalia (german: Herzogtum Westfalen) was a historic territory in the Holy Roman Empire, which existed from 1102 to 1803. It was located in the greater region of Westphalia, originally one of the three main regions in the Germa ...

, which Hesse had received in 1803 and which was now transferred to Prussia. During the turbulence of

Hundred Days

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration ...

, when Napoleon returned from exile,

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Prussia, and the Grand Duchy of Hesse concluded a treaty on 30 June 1816, which regulated the region and went into more detail that the treaty signed at Vienna in the previous year. There were further border agreements and exchanges of small areas of territory with the Electorate of Hesse and the Kingdom of Bavaria. The

patents

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

of possession are dated 8 July 1816, but were only published on 11 July. After this consolidation, the Grand Duchy had a population of roughly 630,000.

The neighbouring

Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, was a state in the Holy Roman Empire that was directly subject to the Emperor. The state was created in 1567 when the Lan ...

, which Napoleon had annexed into the

Kingdom of Westphalia

The Kingdom of Westphalia was a kingdom in Germany, with a population of 2.6 million, that existed from 1807 to 1813. It included territory in Hesse and other parts of present-day Germany. While formally independent, it was a vassal state of the ...

, was re-established by the Congress of Vienna as the

Electorate of Hesse

The Electorate of Hesse (german: Kurfürstentum Hessen), also known as Hesse-Kassel or Kurhessen, was a landgraviate whose prince was given the right to elect the Emperor by Napoleon. When the Holy Roman Empire was abolished in 1806, its prin ...

. After Louis I's counterpart in

Hesse-Kessel,

William I, Elector of Hesse

William I, Elector of Hesse (german: link=no, Wilhelm I., Kurfürst von Hessen; 3 June 1743 – 27 February 1821) was the eldest surviving son of Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel) and Princess Mary of Great Britain, the d ...

, began styling himself "Elector of Hesse and Grand Duke of Fulda," Louis sought the additional title "Elector of

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

and Duke of

Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany, a city

**Worms (electoral district)

*Worms, Nebraska, U.S.

*Worms im Veltlintal, the German name for Bormio, Italy

Arts and entertainme ...

" in order to match William I. However, Austria and Prussia refused to grant this. Instead, William gestured to this claimed title by changing the name of the Grand Duchy to the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine (german: Großherzogtum Hessen und bei Rhein), which also helped to distinguish the two Hessian states.

The Constitution of 1820 and legal reforms

Constitution

As a result of these territorial acquisitions, the Grand Duchy was composed of numerous disparate components. A constitution was therefore urgently needed in order to unite the various territories of the new state. Furthermore, article 13 of the

Constitution of the German Confederation

The Constitution of the German Confederation or German Federal Act (german: Deutsche Bundesakte) was the constitution enacted the day before the Congress of Vienna's Final Act, which established the German Confederation of 39 states, created fr ...

required each member state to establish their own "parliamentary constitution" (''Landständische Verfassung''). Louis I balked at this and was quoted as saying that a parliament "in a sovereign state

snot necessary, not useful, and in some respects dangerous." In fact, the process of constitutional reform was mainly undertaken by the civil service rather than the Grand Duke himself. The members of the civil service who led the reforms were:

*

August Friedrich Wilhelm Crome

August Friedrich Wilhelm Crome (8 June 1753 in Sengwarden – 11 June 1833 in Rödelheim) was a German economist and statistician, and Professor of Cameralism at the University of Giessen. He is known particularly for his 1782 product map of Euro ...

(1753–1833)

* (1769–1839)

* (1771–1843)

* (1773–1839)

* (1781–1860)

* (1776–1836)

In 1816, a three-man legal commission was established to craft a constitution and other necessary laws, composed of Floret and

Carl Ludwig Wilhelm Grolman Carl Ludwig Wilhelm Grolman, since 1812 von Grolmann, (* July 23, 1775 in Giessen; † February 14, 1829 in Darmstadt) was Jurist and Grand Duchy of Hesse Minister-President.

1775 births

1829 deaths

People from Giessen

Jurists from Hesse

German u ...

.

The Constitution which was promulgated by Grand Ducal edict in March 1820 provided for a parliament (''Landstände''), but with no authority of its own. Although this led to the first elections in the Grand Duchy, it also caused massive protests,

tax strikes, and even armed rebellions against the government in some parts of the Grand Duchy. The Grand Duke and his administration gave in to the pressure and a new constitution was promulgated on 17 December 1820. The new constitution contained most of what the opponents of the first constitution had wanted, but the Grand Duke saved face since the constitution was formally granted by him. Louis I was honoured as a great lawgiver, with the in Darmstadt honouring him for "his" constitution.

The constitution was followed by a wide range of further reforms in the Grand Duchy.

Legal and administrative reforms

After its territorial augmentation, the Grand Duchy consisted of numerous territories with different administrative systems. To regularise this, it was urgently necessary to integrate the various regions. At the lower levels, the administrative system of these regions was still based on the

Amt

Amt is a type of administrative division governing a group of municipalities, today only in Germany, but formerly also common in other countries of Northern Europe. Its size and functions differ by country and the term is roughly equivalent to ...

system which had become obsolete centuries earlier. As well as being the lowest level administrative subdivision, the Ämter were also the courts of

first instance

A trial court or court of first instance is a court having original jurisdiction, in which trials take place. Appeals from the decisions of trial courts are usually made by higher courts with the power of appellate review (appellate courts). Mos ...

. Preliminary work on reforming this system began by 1816, and from 1821, the court system and the administrative system were separated at the lowest level in Starkenburg and Upper Hesse provinces. In Rheinhessen, this had already been done around twenty years earlier, while the area was under French control.

The tasks that had previously been assigned to the Ämter were transferred to ("local council districts," responsible for administration) and ("local courts," responsible for judicial functions).

[In Darmstadt and Gießen the equivalents of the Landgerichten were called "Stadtgericht" ("city courts").] This process took place over several years, since at first the state could make new rules about administration and justice only where it had unrestricted authority over these matters. The areas in which the Grand Duchy's sovereignty was unrestricted were called ''Dominiallande'', while the areas where the Standesherren and other nobles exercised their own judicial and administrative authority were the ''Souveränitätslanden''. In the latter areas, the state first had to forge agreements with the individual lords, in order to integrate their judicial powers into the state's court system. In some cases this took until the middle of the 1820s. The "Edict concerning Standesherren's Legal Relationships in the Grand Duchy of Hesse" of 27 March 1820 served as the frame of reference for these agreements. According to this edict, the individual Standesherren retained their personnel sovereignty in the and Landgerichten established in the ''Souveränitätslanden'', which meant that the Standesherren chose the local councillors and judges. This remaining power was only removed during the

German revolutions of 1848–1849

The German revolutions of 1848–1849 (), the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated pro ...

.

From the 50+ Ämter that had previously existed 24 Landratsbezirke and 27 Landgerichten were created. The new Landgerichte had their own

judicial districts

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, which covered almost the same areas as the Landratsbezirke did. In general, the old seats of the

Amtsmen remained either the seat of the Landrat or the Landgericht. Five further Landratsbezirke and six more Landgerichten were created over the following years as a result of the negotiations with the Standesherren.

[The however only existed in the period 1822-1826.]

Civic administration

A modern system of civic administration, modelled on the French system, was also introduced in 1821. The outmoded cooperative parish associations were replaced by a system of civic and parish citizenship.

''Bürgermeister'' (mayors) were established for individual settlements and parish associations with at least 400 inhabitants. In 1831 there were 1092 parishes in the Grand Duchy, administered by 732 mayors.

The mayoralties were administered by an elected local board, consisting of the mayor, deputies, and parish councillors. Male residents elected three men and one of them was chosen as mayor:

*In the ''Dominialland'', this decision was made by the state.

*In the ''Souveränitätslanden'', the Standesherren chose them.

This system ensured that, if the authorities did not like a particular candidate, they could prevent them from taking office. Thus, for example, the entrepreneur received the most votes in Darmstadt two times, but the mayoralty was assigned to the second or third place candidates.

In Upper Hesse and Starkenburg, the local council had oversight of the mayors, while in Rhinehessen, where this local district did not exist, the mayors were chosen directly by the provincial governments.

Abolition of serfdom

The state was also interested in replacing the old agricultural

ground rent

As a legal term, ground rent specifically refers to regular payments made by a holder of a leasehold property to the freeholder or a superior leaseholder, as required under a lease. In this sense, a ground rent is created when a freehold piece of ...

, which was often based on the yield of the year's harvest, with a modern system of taxation. There had been plans for this since 1816. A first step in the process was also implemented during the reforms of 1821. However, this was only a limited reform, since only the ground rents paid to the state were removable. The removal of "private" ground rents, including those paid to churches, religious orders, and Standesherren, failed to pass the first chamber of the parliament. Furthermore, in order to remove the ground rent from their land, farmers were initially required to pay a fee which was eighteen times their annual rent and most farmers could not afford this. The process of abolition would drag on into the second half of the 19th century.

Economic reforms

The constitution declared that an economic system based on

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

principles was the state's goal. Achieving

economic freedom

Economic freedom, or economic liberty, is the ability of people of a society to take economic actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as in the philosophy of economics. One approach to economic freedom comes from the l ...

, which also required the abolition of

guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

privileges, proved difficult, as a result of "damage to multiple interests." Even in this area, different conditions applied in different parts of the Grand Duchy. In Rhine-Hesse, the guilds had been abolished during French rule, while in the provinces on the right bank of the Rhine, guild privileges had only been abolished in a few places for a few industries. This abolition was expanded, but guild privileges continued to exist.

Impact of the July Revolution (1830-1848)

The government in Darmstadt only implemented the

Karlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

in a moderate manner, to the displeasure of the

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

s, Prussia and Austria. On the other hand, the government continually persecuted the opposition (although without much long-term success in the courts), since they feared a revolution.

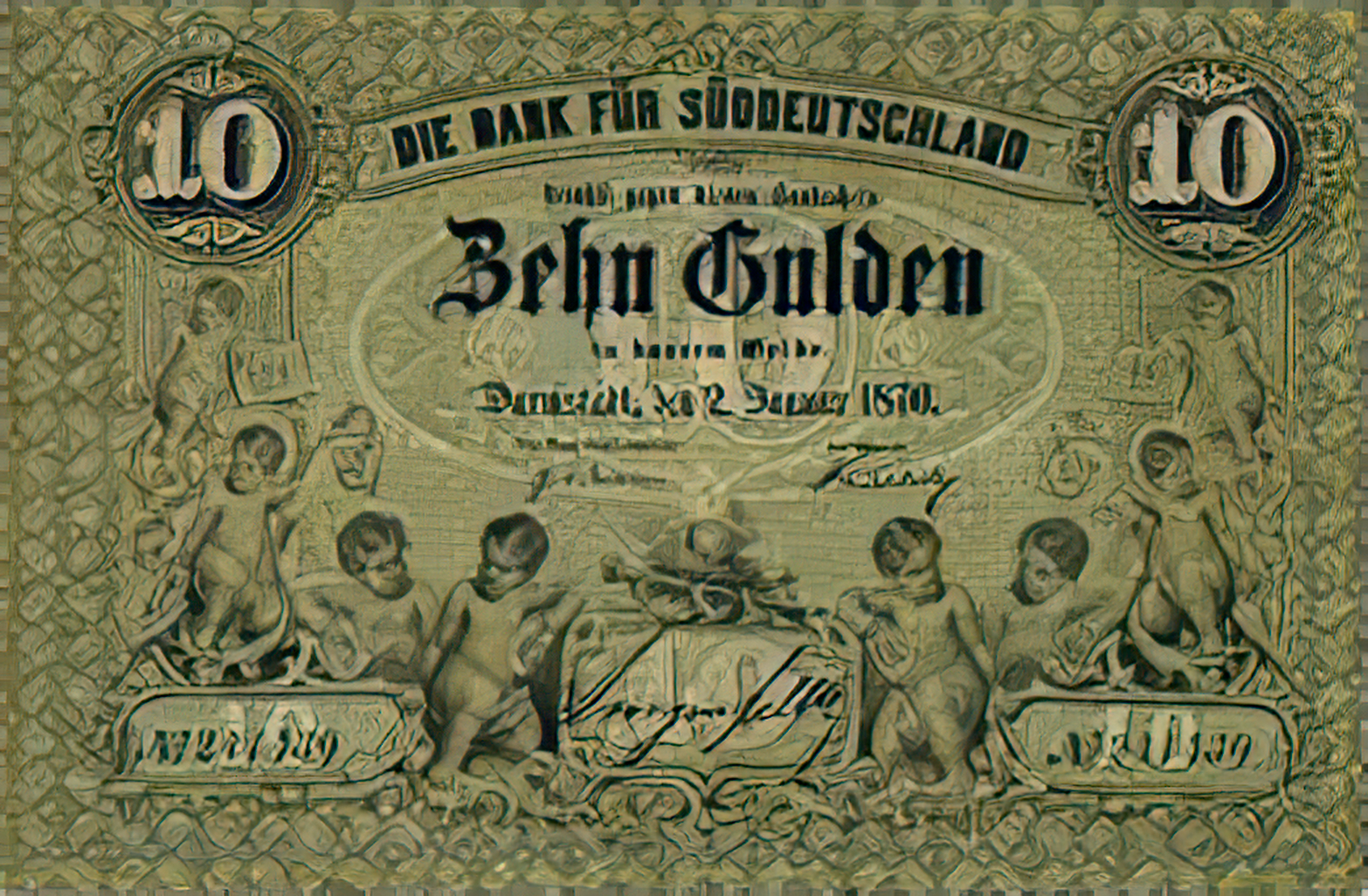

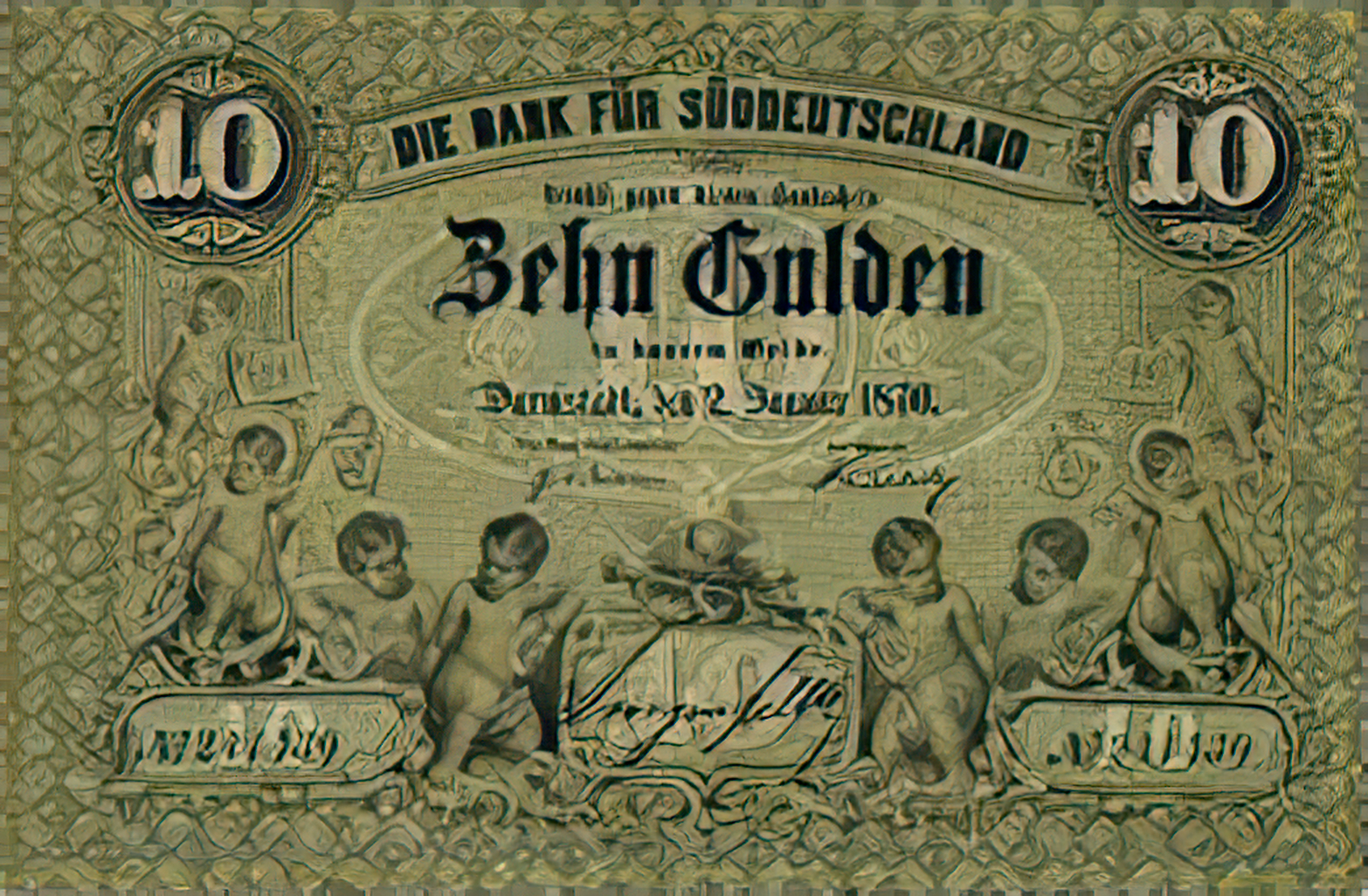

A political crisis was already broiling in Hesse at the time of the July Revolution in 1830: when

Louis II succeeded as Grand Duke after the death of his father in 1830, he had a total debt of two million

guilder

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' "gold penny". This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Roman Empir ...

, which he expected the state to pay for. The liberal opposition in the Landstände considered this outrageous and rejected the proposal with a resounding vote of 41:7.

In Upper Hesse province, a revolt broke out in September 1830, whose members expressed a general dissatisfaction with the state. Characteristically, the territories of the Standesherren were particularly affected:

Büdingen

Büdingen is a town in the Wetteraukreis, in Hesse, Germany. It is mainly known for its well-preserved, heavily fortified medieval town wall and half-timbered houses.

Geography

Location

Büdingen is in the south of the Wetterau below the Vogelsb ...

and

Ortenberg. In these areas, shops were robbed and the local government offices were destroyed. The toll office in

Heldenbergen and the

Nidda courthouse were also affected. The Grand Duke introduced

summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

, which was unanimously approved by the Landstände. Under the command of the Grand Duke's brother,

Prince Emil, the rebellion was suppressed by the army. Part of this suppression was the

Södel Bloodbath, named for the number of dead and wounded.

After the revolution of 1830 was over, the government regained the upper hand and decided that if they could not suppress the rising appetites for reform, they would at least try to control them. The

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

partially switched its focus to cultural activities, which the government then began to monitor warily. Thus, the was allowed to be founded in 1833, but local societies that had originally been planned were not, and the society's charter stated that the society must not occupy itself with "contemporary history and discussion of the political circumstances of more recent times." Above all,

sports club

A sports club or sporting club, sometimes an athletics club or sports society or sports association, is a group of people formed for the purpose of playing sports.

Sports clubs range from organisations whose members play together, unpaid, and ...

s were considered highly suspicious, even though a demonstration of sporting activities was presented in Darmstadt at the dedication of the Ludwig Monument in 1844.

The government initially maintained its relatively open policy towards the press, but reacted harshly to the distribution of ''

The Hessian Courier

''The Hessian Courier'' (German'': Der Hessische Landbote'') is an eight-page pamphlet, written by Georg Büchner in 1834, in which he argues against the social injustices of his time. It was printed and published following editorial revision by ...

'', a pamphlet by

Georg Büchner

Karl Georg Büchner (17 October 1813 – 19 February 1837) was a German dramatist and writer of poetry and prose, considered part of the Young Germany movement. He was also a revolutionary and the brother of physician and philosopher Ludwig Büchn ...

calling for social revolution. The persecution of his fellow contributors continued until 1839.

The March Revolution (1848-1849)

Revolution

In the 1840s, , chief minister from 1821 to 1848, inaugurated the "System du Thil", which entailed the complete suppression of all political discussion. Crop failures and rapidly rising prices for basic foodstuffs created a crisis in the Grand Duchy. Then on 24 February 1848, a revolution in

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

forced King

Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate List of French monarchs#House of Orléans, July Monarchy (1830–1848), monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, h ...

to abdicate. The political tension grew so great that the government no longer waited for citizens' committees and other societies to take banned political actions before persecuting them. Within a few days, the situation had become so dire that, on 5 March 1848, Grand Duke Louis II named his son

Louis III Louis III may refer to:

* Louis the Younger, sometimes III of Germany (835–882)

* Louis III of France (865–882)

* Louis the Blind, Louis III, Holy Roman Emperor, (c. 880–928)

* Louis the Child, sometimes III of Germany (893–911)

* Louis I ...

as his

co-regent

A coregency is the situation where a monarchical position (such as prince, princess, king, queen, emperor or empress), normally held by only a single person, is held by two or more. It is to be distinguished from diarchies or duumvirates such ...

(in fact, Louis III became sole ruler, since Louis II was ill and died a few months later on 16 June 1848). The next day, Karl du Thil was dismissed and replaced as chief minister by

Heinrich von Gagern

Heinrich Wilhelm August Freiherr von Gagern (20 August 179922 May 1880) was a statesman who argued for the unification of Germany.

Early career

The third son of Hans Christoph Ernst, Baron von Gagern, a liberal statesman from Nassau, Heinrich v ...

. Von Gagern proclaimed that the new government would grant all of the "March demands."

However, the rural population's demands that the Standesherren be stripped of their privileges and for serfdom to be abolished without requiring them to pay compensation were not fulfilled. As a result, on 8 March, a massive demonstration gathered before the residences of the Standesherren and stormed some of them. After this, the Standesherren agreed to the abolition of serfdom without compensation. In doing this, however, the farmers exceeded the limits of what the bourgeoise were willing to accept, since they were not willing to countenance interventions in

private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

. Von Gagern brought this protest to a close with military force, but accepted the farmers' demands. This marked the end of the "hot phase" of the revolution in the Grand Duchy, which thus lasted only two weeks.

Reforms

After March 1848, there was a reshuffle of the ministries, since Heinrich von Gagern was elected president of the

Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

and therefore had to resign from his role as a minister in the Grand Duchy. Nevertheless, a series of reforms delivered most of the "March demands".

The new organisation of the administration saw the three provinces and all of the districts abolished and replaced by a single level of local administration midway between them, the

Regierungsbezirk

A ' () means "governmental district" and is a type of administrative division in Germany. Four of sixteen ' ( states of Germany) are split into '. Beneath these are rural and urban districts.

Saxony has ' (directorate districts) with more res ...

("government district"). Each of these had a ''Bezirksrat'' (district council) to represent the people.

A reform of the justice system was also carried out in the areas to the right of the Rhine, including the introduction of

jury courts.

A new electoral law was not passed until 1849. Under this law, all members of both chambers of the Landstände were now to be elected - the lower house by

universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of NBCUniversal

** Universal TV, a ...

equal suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and the upper house by

census suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

. So much "democracy" was novel even for liberal politicians and the interior ministry urged people to act responsibly with their right to vote. Two elections were held under the new electoral system, in 1849 and 1850. Both times, the democrats received a strong majority in the lower chamber, which they used to block the enactment of a state budget.

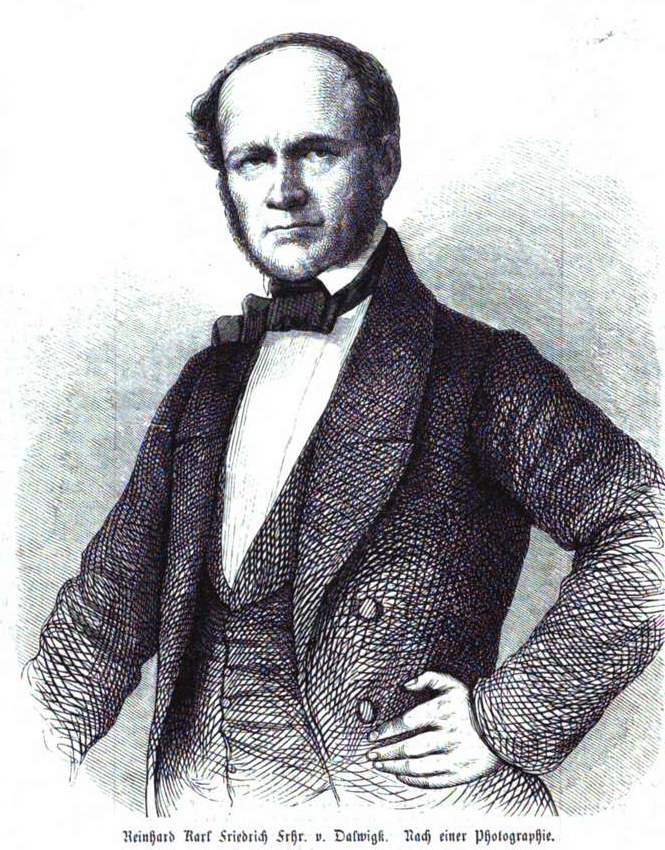

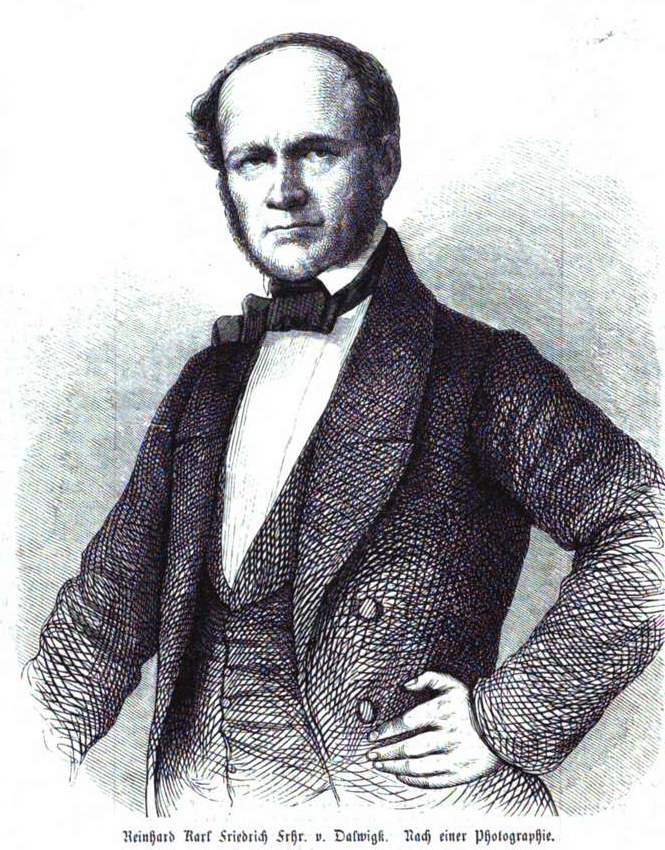

The Dalwigk Era (1850-1866)

Grand Duke Louis III appointed as director of the ministry of the interior on 30 June 1850, transferred him provisionally to the ministry of foreign affairs and the Grand Ducal House on 8 August 1850, and finally named him president of the council of ministers on 25 September 1852. Louis III, who "imitated the image of a paternalistic ruler projected by his grandfather, without achieving his significance,"

[Franz, Fleck, and Kallenberg, ''Großherzogtum Hessen'', p. 827.] and Dalwigk shared a conservative outlook and were both opposed to

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and democracy. For Dalwigk, "the democratic principle

asperilous for the state, since it necessarily leads to

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

.

Internal politics

In this role, Dalwigk organised a coup d'état against the Landstände in autumn 1850. On 7 October 1850, he issued an edict setting aside the existing voting system, removing the sitting Landstände from power, and ordering a return to an electoral law like the one that existed before the March Revolution for "extraordinary" elections to the Landstände. These led to the election of the 14th (extraordinary) Landstände, in which pro-government representatives had a majority, and marked the beginning of comprehensive efforts to dismantle the achievements of the Revolution. Even after the introduction of limited suffrage in October 1850, the Landstände still had many democratic and liberal members and the crisis regarding the

Zollverein

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

in 1852 showed how effective this opposition could still be. However, increased pressure on individual representatives (many of whom gave up and emigrated to the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

) and, especially, the new electoral law of 1856 weakened even this opposition.

Zollverein crisis, 1852

In external politics, Dalwigk and Louis III supported Austria, the

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

, and a

pan-German solution to the German Question.

The first crisis with Prussia arose in 1852 in connection with the

Zollverein

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

, the north German customs union dominated by Prussia. In 1851, the Prussians terminated the existing customs treaty from the end of 1853. Austria then attempted to establish a customs union with the German middle states. Dalwigk signed up for this project, against all economic logic, since the Grand Duchy's exports to Austria were only 3% of its exports to Prussia. Massive protests followed. Even in the Landestände, which was now dominated by pro-Dalwigk conservatives, he found only a minority in favour of this policy. On 14 May 1852, the government went so far as to dissolve the city council of

Friedberg with armed police. All of this did not help Dalwigk at all. In the end, Austria and Prussia came to an agreement between themselves on customs and Austria gave up on the idea of a customs union with the German middle states. The whole affair created an enduring enemy to Dalwigk, however: the Prussian representative in the

Federal Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

,

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

. He advised the Prussian government to refuse to grant a new customs treaty to the Grand Duchy, uness Dalwigk resigned. However, this advice was not followed.

German National Association

The

German National Association

The German National Association, or ''German National Union'' (german: Deutscher Nationalverein) was a liberal political organisation, precursor of a party, in the German Confederation that existed from 1859 to 1867. It was formed by liberals and ...

was founded in 1859. Its goal was to create a liberal

Lesser Germany

{{more citations needed, date=April 2017

The term Lesser Germany (German: ''Kleindeutschland'') or Lesser German solution (German: Kleindeutsche Lösung) denoted essentially exclusion of Austria of the Habsburgs from the planned German unification ...

under Prussian leadership - the opposite goal from Dalwigk. He advised the local councils to prosecute all known members of the Association, using the ban on all political associations as justification. After some prominent Hessians, including , and , were convicted to a symbolic few days imprisonment for this, there was a massive increase in membership of the National Association, which so overwhelmed the prosecutors, that the whole persecution was discontinued in 1861. In summer 1861, the National Association had 937 members in Hesse - the highest number outside Prussia. In 1862, the liberal Hessian Progress Party stood in the Landstände elections and won a landslide victory with 32 of the 50 seats in the lower chamber. Dalwigk's attempt to organise a "Reform Association" to oppose the Progress Party and the National Association was a failure, as was his attempt to get the Federal Convention to ban the National Association.

Dynastic reorientation

The Grand Duchess

Mathilde, a sister of King

Maximilian II of

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, died in 1862. A few weeks later, the crown prince

Louis IV married

Princess Alice of the United Kingdom

Princess Alice (Alice Maud Mary; 25 April 1843 – 14 December 1878) was Grand Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine from 13 June 1877 until her death in 1878 as the wife of Grand Duke Louis IV. She was the third child and second daughter of Queen ...

(1843-1878), the second eldest daughter of

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

at

Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in t ...

on the

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

. This marriage made Louis an in-law of

Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

, crown prince of Prussia, who was married to Alice's sister

Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

. This link changed the political climate in the Grand Duchy. Social questions became topical. In 1863, a workers' education society was established and in 1864 the Building Society for Workers' Housing (''Bauverein für Arbeiterwohnungen'') was established with the support of Louis and Alice. This society was based on

British models

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and erected its first social housing complex, with 64 dwellings, between 1866 and 1868.

Lead-up to the Austro-Prussian War

Von Dalwigk still supported Austria and sought to prevent the creation of a Lesser Germany. In Paris, he sounded out interest in an alliance of

middle power

In international relations, a middle power is a sovereign state that is not a great power nor a superpower, but still has large or moderate influence and international recognition.

The concept of the "middle power" dates back to the origins of ...

s against Prussia (and thus also against Great Britain). This agreement with a foreign initiative, directed against a German power, brought von Dalwigk into even greater disrepute with the Nationalists. In the face of the

Schleswig–Holstein question

The Schleswig–Holstein question (german: Schleswig-Holsteinische Frage; da, Spørgsmålet om Sønderjylland og Holsten) was a complex set of diplomatic and other issues arising in the 19th century from the relations of two duchies, Schleswig ...

, this discredited him significantly. When Austria and Prussia came to an agreement at the

Gastein Convention

The Gastein Convention (german: Gasteiner Konvention), also called the ''Convention of Badgastein'', was a treaty signed at Bad Gastein in Austria on 14 August 1865.Wolfgang Neugebauer (ed.): ''Handbuch der preußischen Geschichte''. Band 2: ''Da ...

, von Dalwigk proved to have chosen the wrong horse once again. He compounded this error in the following year when he took Hesse into the

Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

on the Austrian side.

Austro-Prussian War (1866)

While

Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden is ...

advocated "armed neutrality" in the brewing conflict between Austria and Prussia, von Dalwigk entered the war on the Austrian side immediately after hostilities broke out in June 1866. Initially, the Landstände refused to grant the government the right to issue

war bond

War bonds (sometimes referred to as Victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an unpopular level. They are ...

s, but they backed down in the face of popular opposition, once the government reduced its request from 4 million guilder to 2.5 million.

In anticipation of the Austro-Prussian War, command of the

8th Army of the confederation (around 35,000 men) was entrusted to

Prince Alexander, brother of Grand Duke Louis III. Although he was a

Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

general and an Austrian

lieutenant field marshal

Lieutenant field marshal, also frequently historically field marshal lieutenant (german: Feldmarschall-Leutnant, formerly , historically also and, in official Imperial and Royal Austrian army documents from 1867 always , abbreviated ''FML''), wa ...

, he had no actual military experience. The ultimate military disaster was not attributed to him in the end. Mobilisation in Hesse began on 16 May 1866.

On 14 June 1866, Prussian forces marched into the

Duchy of Holstein

The Duchy of Holstein (german: Herzogtum Holstein, da, Hertugdømmet Holsten) was the northernmost state of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the present German state of Schleswig-Holstein. It originated when King Christian I of Denmark had his ...

and the forces of the German Confederation faced off against Prussia. The Hessian troops were ready to march, but it took more than two weeks to gather the rest of the 8th Army in Frankfurt. Eventually, the army marched through Upper Hesse to the northeast. When the outcome of the war was decided by the Prussian victory at the

Battle of Königgrätz

The Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadowa) was the decisive battle of the Austro-Prussian War in which the Kingdom of Prussia defeated the Austrian Empire. It took place on 3 July 1866, near the Bohemian city of Hradec Králové (German: Königgrä ...

on 3 July 1866, the Hessian forces had still not encountered the enemy. On 6 July 1866, Prince Alexander halted his advance and returned home, but not quickly enough. On 13 July 1866, he was intercepted by Prussian troops at

Aschaffenburg

Aschaffenburg (; South Franconian: ''Aschebersch'') is a town in northwest Bavaria, Germany. The town of Aschaffenburg is not part of the district of Aschaffenburg, but is its administrative seat.

Aschaffenburg belonged to the Archbishopric ...

. In the following

Battle of Frohnhofen

The Battle of Frohnhofen or Battle of Laufach took place on 13 July 1866 as part of the Main Campaign of the Prussian Army in the Austro-Prussian War. In a battle lasting several hours, the Prussian 26th Infantry Brigade repulsed attacks by t ...

, 800 Hessian soldiers were killed or wounded - 15% of all their deployed forces. Their continued retreat southwards led to a second defeat at the

Battle of Tauberbischofsheim

The Battle of Tauberbischofsheim was an engagement of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, on the 24 July at Tauberbischofsheim in the Grand Duchy of Baden between troops of the German Confederation and the Kingdom of Prussia. It was part of the camp ...

on 24 July 1866.

The Hessian general

Karl August von Stockhausen shot himself on 11 December 1866 during investigations into the military disaster. The Hessian minister of war, was replaced on 28 December 1866.

Peace treaty

The crown princes of Hesse and Prussia arranged a cease fire in the middle of July. Dalwigk rejected this in the hope that

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

would enter the war against Prussia. On 31 July, Prussian troops occupied Darmstadt without a battle.

After its defeat in the war, Hesse was forced to concede territory to Prussia in the . Due to the intervention of

Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Fin ...

, the brother-in-law of Grand Duke Louis III, this was a relatively mild treaty. Bismarck had originally intended to annex the whole of Upper Hesse. Instead, Hesse lost only 82 km² and gained nearly 10 km² when Prussia gave the Grand Duchy various enclaves within Hessian territory that had previously belonged to states which Prussia had annexed outright. All of these new territories were located in Upper Hesse, aside from , which was south of the

Main River

Main rivers () are a statutory type of watercourse in England and Wales, usually larger streams and rivers, but also some smaller watercourses. A main river is designated by being marked as such on a main river map, and can include any structure o ...

in Strakenburg province.

Hesse was also required to pay three million guilder in

war indemnities and hand its telegraph network over to the Prussians.

Aftermath

The war did not lead to the dismissal of Dalwigk. Grand Duke Louis III remained committed to him, although his anti-Prussian policy and his very person were now a burden to the country.

One consequence of the peace treaty of 1866 was that the whole area north of the Main River (the Province of Upper Hesse, as well as

Mainz-Kastel

Mainz-Kastel is a district of the city Wiesbaden, which is the capital of the German state Hesse in western Germany.

Kastel is the historical bridgehead of Mainz, the capital of the German state Rhineland-Palatinate and is located on the right si ...

and

Mainz-Kostheim

Mainz-Kostheim is a district administered by the city of Wiesbaden, Germany. Its population is 14,381 (). Mainz-Kostheim was formerly a district of the city of Mainz, until the public administration by the city of Wiesbaden was decided on 10 Aug ...

in the

Mainz district

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Main ...

of Rhine-Hesse Province) became part of the

North German Confederation