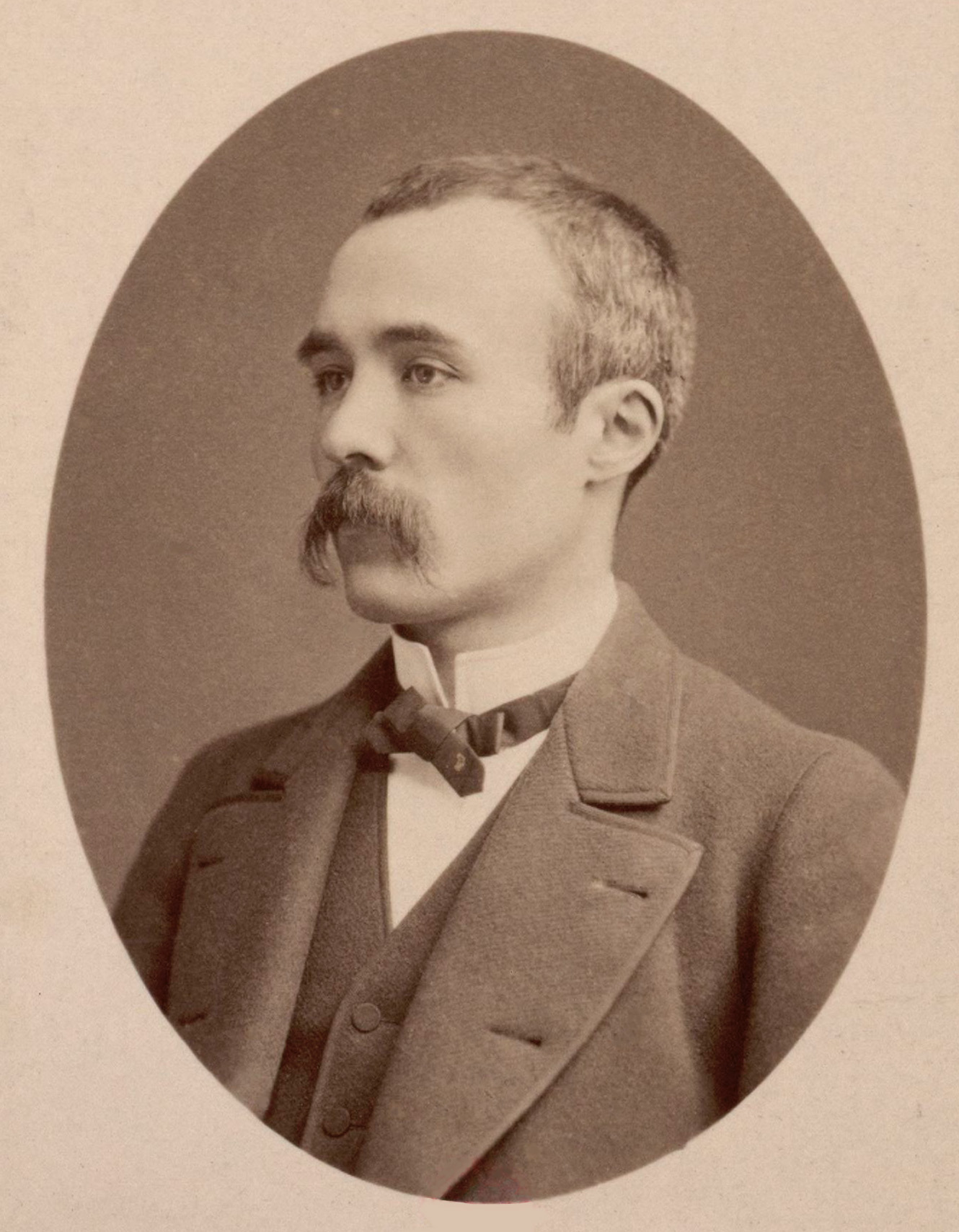

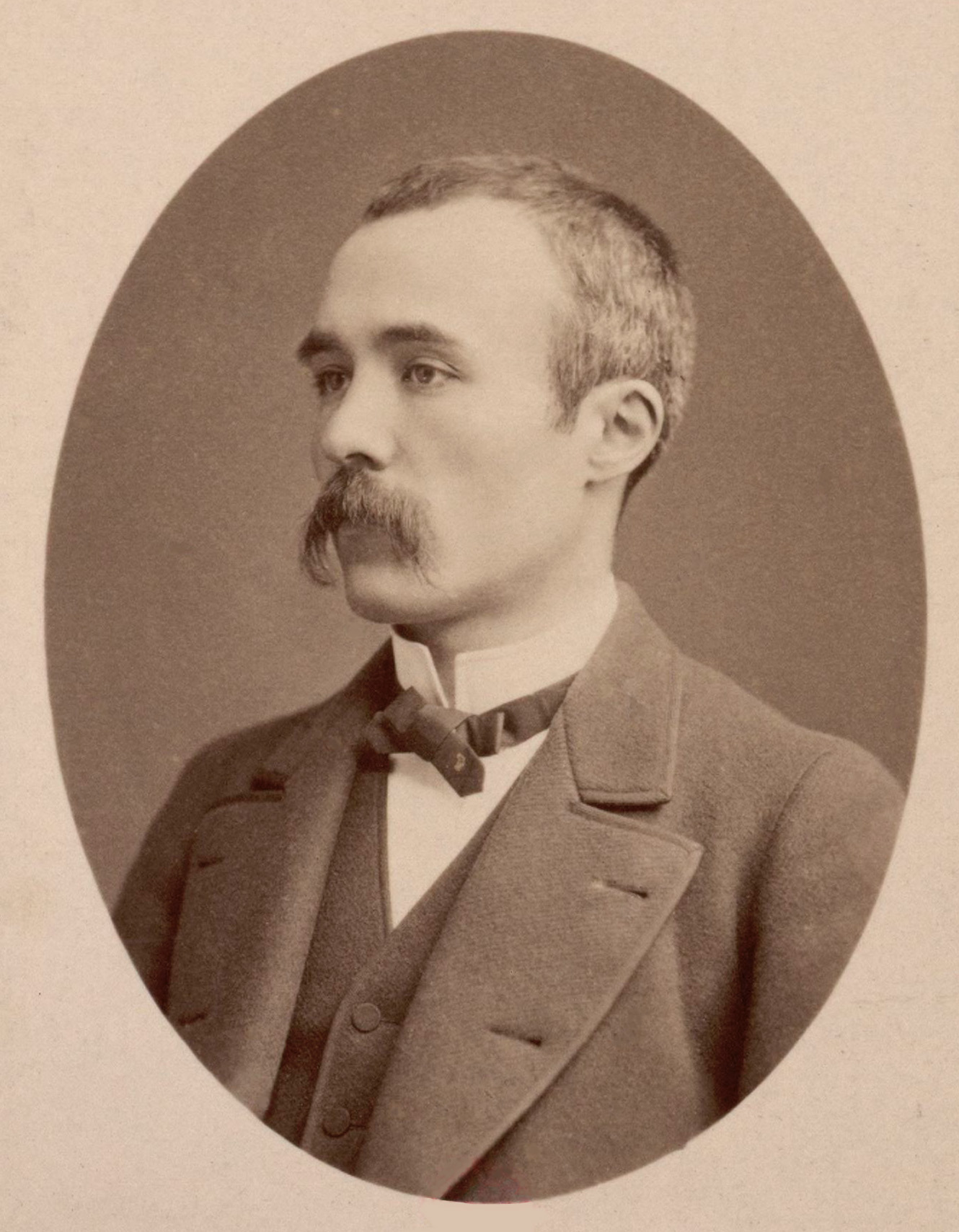

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (,

also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as

Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the

Independent Radicals, he was a strong advocate of

separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

, amnesty of the

Communards

The Communards () were members and supporters of the short-lived 1871 Paris Commune formed in the wake of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

After the suppression of the Commune by the French Army in May 1871, 43,000 Communards w ...

exiled to

New Caledonia, as well as opposition to

colonisation

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

. Clemenceau, a physician turned journalist, played a central role in the politics of the

Third Republic, most notably successfully leading France through the end of the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

After about 1,400,000 French soldiers were killed between the

German invasion German invasion may refer to:

Pre-1900s

* German invasion of Hungary (1063)

World War I

* German invasion of Belgium (1914)

* German invasion of Luxembourg (1914)

World War II

* Invasion of Poland

* German invasion of Belgium (1940)

* G ...

and

Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

, he demanded a total victory over the

German Empire. Clemenceau stood for reparations, a transfer of colonies, strict rules to prevent a rearming process, as well as the restitution of

Alsace–Lorraine, which had been annexed to Germany in 1871. He achieved these goals through the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

signed at the

Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920). Nicknamed ''Père la Victoire'' ("Father of Victory") or ''Le Tigre'' ("The Tiger"), he continued his harsh position against Germany in the 1920s, although not quite so much as President

Raymond Poincaré or former Supreme Allied Commander

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Ar ...

, who thought the treaty was too lenient on Germany, famously stating: "This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years." Clemenceau obtained mutual defence treaties with the United Kingdom and the United States, to unite against a possible future German aggression, but these never took effect.

Early years

Clemenceau was a native of

Vendée

Vendée (; br, Vande) is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442. , born in

Mouilleron-en-Pareds. During the period of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, Vendée had been a

hotbed of monarchist sympathies. The department was remote from Paris, rural, and poor. His mother, Sophie Eucharie Gautreau (1817–1903), was of

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

descent. His father, Benjamin Clemenceau (1810–1897), came from a long line of physicians, but lived off his lands and investments and did not practice medicine. Benjamin was a political activist; he was arrested and briefly held in 1851 and again in 1858. He instilled in his son a love of learning, devotion to

radical politics

Radical politics denotes the intent to transform or replace the principles of a society or political system, often through social change, structural change, revolution or radical reform. The process of adopting radical views is termed radica ...

, and a hatred of

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The lawyer

Albert Clemenceau (1861–1955) was his brother. His mother was a devout Protestant; his father was an

atheist and insisted that his children should have no religious education. Clemenceau was interested in religious issues. He was a lifelong

atheist with a sound knowledge of the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

. He became a leader of anti-clerical or "Radical" forces that battled against the Catholic Church in France and the Catholics in politics. He stopped short of the more extreme attacks. His position was that if church and state were kept rigidly separated, he would not support oppressive measures designed to further weaken the Catholic Church.

After his studies in the Lycée in

Nantes, Clemenceau received his French

baccalaureate Baccalaureate may refer to:

* ''Baccalauréat'', a French national academic qualification

* Bachelor's degree, or baccalaureate, an undergraduate academic degree

* English Baccalaureate, a performance measure to assess secondary schools in England ...

of letters in 1858. He went to Paris to study medicine and eventually graduated with the completion of his thesis "''De la génération des éléments anatomiques''" in 1865.

Political activism and American experience

In Paris, the young Clemenceau became a political activist and writer. In December 1861, he and some friends co-founded a weekly newsletter, ''Le Travail''. On 23 February 1862, he was arrested by the imperial police for having placed posters summoning a demonstration. He spent 77 days in the

Mazas Prison

The Mazas Prison (French: ''Prison de Mazas'') was a prison in Paris, France.

Designed by architects Émile Gilbert and Jean-François-Joseph Lecointe, it was inaugurated in 1850 and located near the Gare de Lyon

The Gare de Lyon, official ...

. Around the same time, Clemenceau also visited the old French revolutionary

Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui (; 8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Biography Early life, political activity and first imprisonment (1805–1848)

Bl ...

and another Republican activist,

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner (11 February 1833 in Mulhouse (Haut Rhin) – 19 September 1899 in Bagnères-de-Luchon (Haute Garonne)) was a chemist, industrialist, a Protestant and an Alsatian politician. He was the uncle by marriage of the wife ...

, in jail, further deepening his hatred of the

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

regime and advancing his fervent

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

.

He was graduated as a doctor of medicine on 13 May 1865, founded several literary magazines, and wrote many articles, most of which attacked the imperial regime of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

. After a failed love affair, Clemenceau left France for the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

as the imperial agents began cracking down on dissidents and sending most of them to the ''bagne de Cayennes'' (

Devil's Island Penal System) in

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas. ...

.

Clemenceau worked in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

during the years 1865–1869, following the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. He maintained a medical practice, but spent much of his time on political journalism for a Parisian newspaper, ''Le Temps''. He taught French in

Great Barrington, Massachusetts

Great Barrington is a town in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 7,172 at the 2020 census. Both a summer resort and home to Ski Butternut, ...

, and also taught and rode horseback at a private girls' school in

Stamford, Connecticut, where he would meet his future wife. During this time, he joined French exile clubs in New York that were opposing the imperial regime.

As part of his journalistic activity, Clemenceau covered the country's recovery following the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, the workings of American democracy, and the racial questions related to the end of

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. From his time in America, he retained a strong faith in American democratic ideals as opposed to France's imperial regime, as well as a sense of political compromise that later would become a hallmark of his political career.

Marriage and family

On 23 June 1869, he married

Mary Eliza Plummer (1849–1922), in New York City. She had attended the school where he taught horseback riding and was one of his students. She was the daughter of Harriet A. Taylor and William Kelly Plummer.

Following their marriage, the Clemenceaus moved to France. They had three children together, Madeleine (born in 1870), Thérèse (1872) and Michel (1873).

Although Clemenceau had many mistresses, when his wife took a tutor of their children as her lover, Clemenceau had her put in jail for two weeks and then sent her back to the United States on a steamer in third class. The marriage ended in a contentious divorce in 1891. He obtained custody of their children. He then had his wife stripped of French nationality.

Beginning of the Third Republic

Clemenceau had returned to Paris after the French defeat at the

Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and its allies, ...

in 1870 during the

Franco-Prussian War and the fall of the

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930 ...

. After returning to medical practice as a physician in Vendée, he was appointed mayor of the

18th arrondissement of Paris, including

Montmartre

Montmartre ( , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Right Bank. The historic district established by the City of Paris in 1995 is bordered by Rue Ca ...

, and he also was elected to the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

for the 18th arrondissement. When the

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

seized power in March 1871, he tried unsuccessfully to find a compromise between the more radical leaders of the Commune and the more conservative French government. The Commune declared that he had no legal authority to be mayor and seized the city hall of the 18th arrondissement. He ran for election to the Paris Commune council, but received fewer than eight hundred votes and took no part in its governance. He was in

Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefect ...

when the commune was suppressed by the French Army in May 1871.

After the fall of the commune, he was elected to the Paris municipal council on 23 July 1871 for the Clignancourt quarter and retained his seat until 1876. He first held the offices of secretary and vice-president, then he became president in 1875.

Chamber of Deputies

In 1876, Clemenceau stood for the

Chamber of Deputies (which replaced the National Assembly in 1875) and was elected for the 18th arrondissement. He joined the far left and his energy and mordant eloquence speedily made him the leader of the radical section. In 1877, after the

Crisis of 16 May 1877, he was one of the republican majority who denounced the ministry of the

Duc de Broglie

The House of Broglie (, also ; french: Maison de Broglie, or ) is a French noble family, originally Piedmontese, who migrated to France in the year 1643.

History

() was the name of an old Piedmontese noble family, from which were descended t ...

. Clemenceau led resistance to the anti-republican policy of which the incident of 16 May was a manifestation. In 1879, his demand for the indictment of the Broglie ministry brought him prominence.

[Watson, ''Georges Clemenceau: A Political Biography'' (1976).]

From 1876 to 1880, Clemenceau was one of the main defenders of the general amnesty of thousands of Communards, members of the revolutionary government of the 1871

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

who had been deported to

New Caledonia. Along with other radicals and figures such as poet and then-Senator

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, as well as a growing number of republicans, he supported several unsuccessful proposals. Finally a general amnesty was adopted on 11 July 1880. The "reconciliation" envisaged by Clemenceau could begin, as the remaining deported Communards returned to France, including his friend

Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French a ...

.

In 1880, Clemenceau started his newspaper, ''La Justice'', which became the principal organ of

Parisian Radicalism. From this time, throughout the presidency of

Jules Grévy

François Judith Paul Grévy (15 August 1807 – 9 September 1891), known as Jules Grévy (), was a French lawyer and politician who served as President of France from 1879 to 1887. He was a leader of the Moderate Republicans, and given that hi ...

(1879–1887), he became widely known as a political critic and destroyer of ministries (''le Tombeur de ministères'') who avoided taking office himself. Leading the far left in the Chamber of Deputies, he was an active opponent of the

colonial policy of Prime Minister

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

, which he opposed on moral grounds and also as a form of diversion from the more important goal of "

Revenge against Germany" for the annexation of

Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

and

Lorraine

Lorraine , also , , ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; german: Lothringen ; lb, Loutrengen; nl, Lotharingen is a cultural and historical region in Northeastern France, now located in the administrative region of Gra ...

after the

Franco-Prussian War. In 1885, his criticism of the conduct of the

Sino-French War contributed strongly to the fall of the Ferry cabinet that year.

During the

French legislative elections of 1885, he advocated a strong radical programme and was returned both for his old seat in Paris and for the

Var

Var or VAR may refer to:

Places

* Var (department), a department of France

* Var (river), France

* Vār, Iran, village in West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Var, Iran (disambiguation), other places in Iran

* Vár, a village in Obreja commune, Ca ...

, district of

Draguignan

Draguignan (; oc, Draguinhan) is a commune in the Var department in the administrative region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (formerly Provence), southeastern France.

It is a sub-prefecture of the department and self-proclaimed "capital of ...

. He chose to represent the latter in the Chamber of Deputies. Refusing to form a ministry to replace the one he had overthrown, he supported the right in keeping Prime Minister

Charles de Freycinet

Charles Louis de Saulces de Freycinet (; 14 November 1828 – 14 May 1923) was a French statesman and four times Prime Minister during the Third Republic. He also served an important term as Minister of War (1888–1893). He belonged to the Opp ...

in power in 1886 and was responsible for the inclusion of

Georges Ernest Boulanger

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Repub ...

in the Freycinet cabinet as war minister. When General Boulanger revealed himself as an ambitious pretender, Clemenceau withdrew his support and became a vigorous opponent of the heterogeneous Boulangist movement, although the radical press continued to patronize the general.

By his exposure of the

Wilson scandal, and by his personal plain speaking, Clemenceau contributed largely to the resignation of

Jules Grévy

François Judith Paul Grévy (15 August 1807 – 9 September 1891), known as Jules Grévy (), was a French lawyer and politician who served as President of France from 1879 to 1887. He was a leader of the Moderate Republicans, and given that hi ...

from the presidency of France in 1887. He had declined Grévy's request to form a cabinet upon the downfall of the cabinet of

Maurice Rouvier

Maurice Rouvier (; 17 April 1842 – 7 June 1911) was a French statesman of the "Opportunist" faction, who served as the Prime Minister of France. He is best known for his financial policies and his unpopular policies designed to avoid a ruptur ...

by advising his followers not to vote for

Charles Floquet

Charles Thomas Floquet (; 2 October 1828 – 18 January 1896) was a French lawyer and statesman.

Biography

He was born at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port ( Basses-Pyrénées). Charles Floquet is the son of Pierre Charlemagne Floquet and Marie Léocadie ...

, Jules Ferry, nor Charles de Freycinet, Clemenceau was primarily responsible for the election of an "outsider",

Marie François Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot (; 11 August 1837 – 25 June 1894) was a French statesman, who served as the President of France from 1887 until his assassination in 1894.

Early life

Marie François Sadi Carnot was the son of the statesman Hippo ...

, as president.

The split in the Radical Party over

Boulangism

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Repub ...

weakened his hand and its collapse meant that moderate republicans did not need his help. A further misfortune occurred in the

Panama affair, as Clemenceau's relations with the businessman and politician

Cornelius Herz led to his being included in the general suspicion. In response to accusations of corruption levelled by the nationalist politician

Paul Déroulède

Paul Déroulède (2 September 1846 – 30 January 1914) was a French author and politician, one of the founders of the nationalist League of Patriots.

Early life

Déroulède was born in Paris. He was published first as a poet in the magazine '' ...

, Clemenceau fought a duel with him on 23 December 1892. Six shots were discharged, but neither participant was injured.

Clemenceau remained the leading spokesman for French radicalism, but his hostility to the

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (french: Alliance Franco-Russe, russian: Франко-Русский Альянс, translit=Franko-Russkiy Al'yans), or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Russo-Français'', Русско-Французско� ...

so increased his unpopularity that in the

French legislative elections of 1893, he was defeated for his seat in the Chamber of Deputies after having held it continuously since 1876.

Dreyfus Affair

For nearly a decade after his 1893 defeat, Clemenceau confined his political activities to journalism. His career was further clouded by the long-drawn-out

Dreyfus case

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

, in which he took an active part as a supporter of

Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

and an opponent of the anti-Semitic and nationalist campaigns. In all, during the affair Clemenceau published 665 articles defending Dreyfus.

On 13 January 1898, Clemenceau published Émile Zola's ''

J'Accuse...!'' on the front page of the Paris daily newspaper, ''

L'Aurore

''L’Aurore'' (; ) was a literary, liberal, and socialist newspaper published in Paris, France, from 1897 to 1914. Its most famous headline was Émile Zola's '' J'Accuse...!'' leading into his article on the Dreyfus Affair.

The newspaper was ...

'', of which he was owner and editor. He decided to run the controversial article that would become a famous part of the

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

in the form of an open letter to

Félix Faure

Félix François Faure (; 30 January 1841 – 16 February 1899) was the President of France from 1895 until his death in 1899. A native of Paris, he worked as a tanner in his younger years. Faure became a member of the Chamber of Deputies for ...

, the president of France.

In 1900, he withdrew from ''La Justice'' to found a weekly review, ''Le Bloc'', to which he practically was the sole contributor. The publication of ''Le Bloc'' lasted until 15 March 1902. On 6 April 1902, he was elected senator for the Var district of

Draguignan

Draguignan (; oc, Draguinhan) is a commune in the Var department in the administrative region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (formerly Provence), southeastern France.

It is a sub-prefecture of the department and self-proclaimed "capital of ...

, although he had previously called for the suppression of the French

Senate, as he considered it a strong-house of conservatism. He served as the senator for Draguignan until 1920.

Clemenceau sat with the

Independent Radicals in the Senate and moderated his positions, although he still vigorously supported the

Radical-Socialist

The Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party (french: Parti républicain, radical et radical-socialiste) is a liberal and formerly social-liberal political party in France. It is also often referred to simply as the Radical Party (frenc ...

ministry of Prime Minister

Émile Combes

Émile Justin Louis Combes (; 6 September 183525 May 1921) was a French statesman and freemason who led the Bloc des gauches's cabinet from June 1902 to January 1905.

Career

Émile Combes was born in Roquecourbe, Tarn. He studied for the pri ...

, who spearheaded the

anti-clericalist republican struggle. In June 1903, he undertook the direction of ''L'Aurore'', the journal that he had founded. In it, he led the campaign to revisit the Dreyfus affair and to create a

separation of church and state in France. The latter was implemented by the

.

Cabinet and office of Prime Minister

In March 1906, the ministry of

Maurice Rouvier

Maurice Rouvier (; 17 April 1842 – 7 June 1911) was a French statesman of the "Opportunist" faction, who served as the Prime Minister of France. He is best known for his financial policies and his unpopular policies designed to avoid a ruptur ...

fell as a result of civil disturbances provoked by the implementation of the law on the separation of church and state and the victory of radicals in the

French legislative elections of 1906. The new government of

Ferdinand Sarrien

Jean Marie Ferdinand Sarrien (; (15 October 1840 – 28 November 1915) was a French politician of the Third Republic. He was born in Bourbon-Lancy, Saône-et-Loire and died in Paris. He headed a cabinet supported by the ''Bloc des gauches'' (L ...

appointed Clemenceau as minister of the interior in the cabinet. On a domestic level, Clemenceau reformed the

French police

Law enforcement in France has a long history dating back to AD 570 when night watch systems were commonplace.Dammer, H. R. and Albanese, J. S. (2014). ''Comparative Criminal Justice Systems'' (5th ed.). Wadesworth Cengage learning: Belmont, ...

forces and ordered repressive policies toward the workers movement. He supported the formation of scientific police by

Alphonse Bertillon and founded the ''Brigades mobiles'' (French for "mobile squads") led by

Célestin Hennion

Célestin Hennion CVO (8 September 1862 – 14 March 1915) was a French police officer who rose to head the Prefecture of Police (french: Préfecture de Police). He was responsible for the reorganisation of the Préfecture and the introductio ...

. These squads were nicknamed ''Brigades du Tigre'' ("The Tiger's Brigades") after Clemenceau, who was nicknamed "The Tiger".

The miners strike in the

Pas de Calais

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait (french: Pas de Calais - ''Strait of Calais''), is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, separating Great Britain from continent ...

after the

Courrières mine disaster

The Courrières mine disaster, Europe's worst mining accident, caused the death of 1,099 miners in Northern France on 10 March 1906. This disaster was surpassed only by the Benxihu Colliery accident in China on 26 April 1942, which killed 1,5 ...

, which resulted in the death of more than one thousand persons, threatened widespread disorder on 1 May 1906. Clemenceau ordered the military against the strikers and repressed the wine growers strike in the

Languedoc-Roussillon

Languedoc-Roussillon (; oc, Lengadòc-Rosselhon ; ca, Llenguadoc-Rosselló) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, it joined with the region of Midi-Pyrénées to become Occitania. It comprised five departments, and b ...

. His actions alienated the

French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) socialist party, from which he definitively broke in his notable reply in the Chamber of Deputies to

Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

, leader of the SFIO, in June 1906. Clemenceau's speech positioned him as the strong man of the day in French politics; when the Sarrien ministry resigned in October, Clemenceau became premier.

After a proposal by the deputy

Paul Dussaussoy

Paul Dussaussoy (6 January 1860 – 15 March 1909) was a French lawyer and politician. Born in Dunkirk, Nord, he was a deputy to the national assembly from 1893 to 1902 and again from 1906 until his premature death in 1909.

He introduced the fir ...

for limited women's suffrage in local elections, Clemenceau published a pamphlet in 1907 in which he declared that if women were given the vote France would return to the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

As the

revolt of the Languedoc winegrowers developed Clemenceau at first dismissed the complaints, then sent in troops to keep the peace in June 1907.

During 1907 and 1908, he led the development of a new ''

Entente cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

'' with Britain, which gave France a successful role in European politics. Difficulties with Germany and criticism by the Socialist party in connection with the handling of the

First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis or the Tangier Crisis was an international crisis between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. Germany wanted to challenge France's growing control over Morocco, aggravating France and Great Britain. The ...

in 1905–06 were settled at the

Algeciras Conference.

Clemenceau was defeated on 20 July 1909 in a discussion in the Chamber of Deputies on the state of the navy, in which bitter words he exchanged with

Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé (1 March 185222 February 1923) was a French politician who served as foreign minister from 1898 to 1905. He is best known for his hatred of Germany and efforts to secure alliances with Russia and Great Britain that became t ...

, the former president of the Council whose downfall Clemenceau had aided. Refusing to respond to Delcassé's technical questions, Clemenceau resigned after his proposal for the order of the day vote was rejected. He was succeeded as premier by

Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

, with a reconstructed cabinet.

Between 1909 and 1912, Clemenceau dedicated his time to travel, conferences, and the treatment of his illness. He went to South America in 1910, traveling to

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

,

Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

(where he went as far as

Santa Ana (Tucuman) in northwest Argentina). There, he was amazed by the influence of French culture and of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

on local elites.

He published the first issue of the ''Journal du Var'' on 10 April 1910. Three years later, on 6 May 1913, he founded ''L'Homme libre'' ("The Free Man") newspaper in Paris, for which he wrote a daily editorial. In these media, Clemenceau focused increasingly on foreign policy and condemned the

anti-militarism

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (especia ...

of the Socialists.

First World War

At the outbreak of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

in August 1914, Clemenceau's newspaper was one of the first to be

censored

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

by the government. It was suspended from 29 September 1914 to 7 October. In response, Clemenceau changed the newspaper's name to ''L'Homme enchaîné'' ("The Chained Man") and criticized the government for its lack of transparency and its ineffectiveness, while defending the patriotic ''

union sacrée The Sacred Union (french: Union Sacrée, ) was a political truce in France in which the left-wing agreed, during World War I, not to oppose the government or call any strikes. Made in the name of patriotism, it stood in opposition to the pledge mad ...

'' against the

German Empire.

In spite of the censorship imposed by the French government on Clemenceau's journalism at the beginning of World War I, he still wielded considerable political influence. As soon as the war started, Clemenceau advised Interior Minister

Malvy to invoke Carnet B, a list of known and suspected subversives who were supposed to be arrested upon mobilisation, in order to prevent the collapse of popular support for a war effort. The

Prefect of Police gave the same advice, but the government did not follow it. In the end, 80% of the 2,501 people listed on Carnet B as subversives volunteered for service. In autumn 1914, Clemenceau declined to join the

government of national unity

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other nati ...

as justice minister.

He suggested transportation of

T. G. Masaryk's Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion (Czech language, Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak language, Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces composed predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Allies of World ...

from Russia to France s. c. "North trip" (by North sea) as first (the first realization 15 October 1917 from Archangelsk).

He was a vehement critic of the wartime French government, asserting that it was not doing enough to win the war. His stance was driven by a will to regain the province of Alsace-Lorraine, a view shared by public opinion. The autumn of 1917 saw the disastrous Italian defeat at the

Battle of Caporetto

The Battle of Caporetto (also known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, the Battle of Kobarid or the Battle of Karfreit) was a battle on the Italian front of World War I.

The battle was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Central ...

, the

Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia, and rumours that former Prime Minister

Joseph Caillaux

Joseph-Marie–Auguste Caillaux (; 30 March 1863 Le Mans – 22 November 1944 Mamers) was a French politician of the Third Republic. He was a leader of the French Radical Party and Minister of Finance, but his progressive views in opposition ...

and Interior Minister

Louis Malvy

Louis-Jean Malvy (1 December 1875 – 10 June 1949) was the Interior Minister of France in 1914.

Biography

Louis-Jean Malvy was born on 1 December 1875 in Figeac.

Career

Malvy was a member of the Radical Party and served in the Chamber of Depu ...

might have engaged in treason. Prime Minister

Paul Painlevé

Paul Painlevé (; 5 December 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French mathematician and statesman. He served twice as Prime Minister of the Third Republic: 12 September – 13 November 1917 and 17 April – 22 November 1925. His entry into politic ...

was inclined to open negotiations with Germany. Clemenceau argued that even German restitution of Alsace-Lorraine and the liberation of Belgium would not be enough to justify France abandoning her allies. This forced

Alexandre Ribot

Alexandre-Félix-Joseph Ribot (; 7 February 184213 January 1923) was a French politician, four times Prime Minister.

Early career

Ribot was born in Saint-Omer, Pas-de-Calais. After a brilliant academic career at the University of Paris, where h ...

and Aristide Briand (both the previous two prime ministers, of whom the latter was by far the more powerful politician who had been approached by a German diplomat) to agree in public that there would be no separate peace. For many years, Clemenceau was blamed for having blocked a possible compromise peace, but it is now clear from examination of German documents that Germany had no serious intention of handing over Alsace-Lorraine. The prominence of his opposition made him the best known critic and the last man standing when the others had failed. ''"Messieurs, les Allemands sont toujours à

Noyon

Noyon (; pcd, Noéyon; la, Noviomagus Veromanduorum, Noviomagus of the Veromandui, then ) is a commune in the Oise department, northern France.

Geography

Noyon lies on the river Oise, about northeast of Paris. The Oise Canal and the Cana ...

"'' (Gentlemen, the Germans are still at Noyon) wrote Clemenceau's paper endlessly.

Second term as prime minister

In November 1917, at one of the darkest hours for the French war effort in World War I, Clemenceau was appointed to the prime ministership. Unlike his predecessors, he discouraged internal disagreement and called for peace among the senior politicians.

1917: return to power

Clemenceau governed from the Ministry of War on

Rue Saint-Dominique. Almost his first act as prime minister was to relieve General

Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated th ...

from his command of the

Salonika front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of German ...

. This was the main topic of discussion at the first meeting of the war committee on 6 December, at which Clemenceau stated, "Sarrail cannot remain there". The reason for Sarrail's dismissal was his links with the socialist politicians Joseph Caillaux and Louis Malvy (at that time suspected of treasonable contacts with the Germans)

Churchill later wrote that Clemenceau "looked like a wild animal pacing to and fro behind bars" in front of "an assembly which would have done anything to avoid putting him there, but, having put him there, felt they must obey".

When Clemenceau became prime minister in 1917 victory seemed to be elusive. There was little activity on the

western front because it was believed that there should be limited attacks until the American support arrived. At this time, Italy was on the defensive, Russia virtually had stopped fighting – and it was believed (correctly –

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

) that they would be making a separate peace with Germany. At home, the government had to deal with increasing demonstrations against the war, a scarcity of resources, and air raids that were causing huge physical damage to Paris as well as undermining the morale of its citizens. It also was believed that many politicians secretly wanted peace. It was a challenging situation for Clemenceau; after years of criticizing other men during the war, he suddenly found himself in a position of supreme power. He was isolated politically, however. He did not have close links with any parliamentary leaders (especially after he had antagonized them so relentlessly during the course of the war) and so, had to rely on himself and his own circle of friends.

Clemenceau's assumption of power meant little to the men in the trenches at first. They thought of him as "just another politician", and the monthly assessment of troop morale found that only a minority found comfort in his appointment. Slowly, however, as time passed, the confidence he inspired in a few, began to grow throughout all the fighting men. They were encouraged by his many visits to the trenches. This confidence began to spread from the trenches to the home front and it was said, "We believed in Clemenceau rather in the way that our ancestors believed in Joan of Arc." After years of criticism against the French army for its conservatism and Catholicism, Clemenceau would need help to get along with the military leaders to achieve a sound strategic plan. He nominated General

Henri Mordacq

Jean Jules Henri Mordacq (12 January 1868 – 14 April 1943) was a French general. During his early years as a captain he was the sabre champion of the French Army's officer corps. In World War I, he was a frontline commander of initially the , ...

to be his military chief of staff. Mordacq helped to inspire trust and mutual respect from the army to the government which proved essential to the final victory.

Clemenceau also was well received by the media, because they felt that France was in need of strong leadership. It was widely recognized that throughout the war he was never discouraged and never stopped believing that France could achieve total victory. There were skeptics, however, who believed that Clemenceau, like other war-time leaders, would have a short time in office. It was said, "Like everyone else ... Clemenceau will not last long—only long enough to clean up

he war

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

"

1918: crackdown

As the military situation worsened in early 1918, Clemenceau continued to support the policy of total war – "We present ourselves before you with the single thought of total war" – and the policy of "la guerre jusqu'au bout" (war until the end). His speech of 8 March advocating this policy was so effective that it left a vivid impression on

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, who would make similar speeches upon becoming British prime minister in 1940. Clemenceau's war policy encompassed the promise of victory with justice, loyalty to the fighting men, and immediate and severe punishment of crimes against France.

Joseph Caillaux

Joseph-Marie–Auguste Caillaux (; 30 March 1863 Le Mans – 22 November 1944 Mamers) was a French politician of the Third Republic. He was a leader of the French Radical Party and Minister of Finance, but his progressive views in opposition ...

, a former French prime minister, disagreed with Clemenceau's policies. He wanted to surrender to Germany and negotiate a peace, thus Clemenceau viewed Caillaux as a threat to national security. Unlike previous ministers, Clemenceau moved against Caillaux publicly. As a result, a parliamentary committee decided that Caillaux would be arrested and imprisoned for three years. Clemenceau believed, in the words of

Jean Ybarnégaray

Michel Albert Jean Joseph Ybarnégaray (; 16 October 1883 – 25 April 1956) was a French Basque politician and founder of the International Federation of Basque Pelota.

Jean Ybarnegaray was born in Uhart-Cize, Department of Pyrénées-Atlan ...

, that Caillaux's crime "was not to have believed in victory

ndto have gambled on his nation's defeat".

The arrest of Caillaux and others raised the issue of Clemenceau's harshness, who in turn argued that the only powers he assumed were those necessary for winning the war. The many trials and arrests aroused great public excitement. These trials, far from making the public fear the government, inspired confidence, as the public felt that for the first time in the war, action was being taken and they were being firmly governed. The claims that Clemenceau's "firm government" was a dictatorship found little support. Clemenceau was still held accountable to the people and media. He relaxed censorship on political views as he believed that newspapers had the right to criticize political figures: "The right to insult members of the government is inviolable."

In 1918, Clemenceau thought that France should adopt

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's

Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

, mainly because of its point that called for the return of

Alsace-Lorraine to France. This meant that victory would fulfil the war aim that was crucial for the French public. Clemenceau was sceptical about some other points, however, including those concerning the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, as he believed that the latter could succeed only in a utopian society.

As war minister, Clemenceau was also in close contact with his generals, but he did not always make the most effective decisions concerning military issues (although he did heed the advice of the more experienced generals). As well as talking strategy with the generals, he also went to the trenches to see the

poilus, the French infantrymen. He would speak to them and assure them that their government was looking after them. The poilus had great respect for Clemenceau and his disregard for danger, as he often visited soldiers only yards away from German front lines. The government was worried about the visits of Clemenceau to the front lines, as most of the time he was risking his own life by insulting and threatening the German soldiers in person directly from the trenches. These visits, his speech, and his verbal threats directly to the enemy impressed the soldiers and contributed to Clemenceau's title "Père la Victoire" (Father of Victory).

1918: German spring offensive

On 21 March 1918, the Germans began their great

spring offensive. The allies were caught off guard and a gap was created in the British and French lines that risked handing over access to Paris to the Germans. This defeat cemented Clemenceau's belief, and that of the other allies, that a coordinated, unified command was the best option. It was decided that

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Ar ...

would be appointed as "

generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

".

The German line continued to advance and Clemenceau believed that the fall of Paris could not be ruled out. Public opinions arose that if "the Tiger", as well as, Foch and

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

stayed in power for even another week, France would be lost and that a government headed by

Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

would be beneficial to France, because he would make peace with Germany on advantageous terms. Clemenceau adamantly opposed these opinions and he gave an inspirational speech in the Chamber of Deputies; the chamber subsequently voted their confidence in him by 377 votes to 110.

1918: allied counter-offensive and armistice

As the

allied counter-offensives began to push the Germans back, it became clear that the Germans could no longer win the war. Although they still occupied vast amounts of French territory, they did not have sufficient resources and manpower to continue their attack. As countries allied to Germany began to ask for an armistice, it was obvious that Germany would soon follow. On 11 November 1918, an armistice with Germany was signed. Clemenceau was embraced in the streets and attracted many admiring crowds. He was viewed by the French public as a strong, energetic, positive leader who was key to the allied victory of 1918.

Paris Peace Conference

To settle the international political issues left over from the conclusion of World War I, it was decided that a peace conference would be held in Paris, France. Famously, the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

between Germany and the Allied Powers to conclude the conflict was signed in the

Palace of Versailles, but the deliberations on which it was based were conducted in Paris, hence the name given to the meeting of the victorious heads of state that produced the treaties signed with the defeated powers: the

Paris Peace Conference of 1919. On 13 December 1918, United States president

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

received an enthusiastic welcome in France. His

Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

and the concept of a

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

had made a big impact on the war-weary French. At their first meeting, Clemenceau realized that Wilson was a man of principle and conscience.

The powers agreed that since the conference was being held in France, Clemenceau would be the most appropriate president. Also, he spoke both English and French, the official languages of the conference. Clemenceau had an unassailable position of full control of the French delegation. Parliament gave him a vote of confidence on 30 December 1918, by a vote of 398 to 93. The rules of the conference allowed France five

plenipotentiaries

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word ' ...

. They became Clemenceau and four others who were his pawns. He excluded all military men, especially Foch. He excluded the president of France, Raymond Poincaré, keeping him in the dark on the progress of negotiations. He excluded all parliamentary deputies, saying he would negotiate the treaty and it would be parliament's duty to vote it up or down, after it was finished.

The progress at the conference was much slower than anticipated and decisions were being tabled constantly. It was this slow pace that induced Clemenceau to give an interview showing his irritation to an American journalist. He said he believed that Germany had won the war industrially and commercially as its factories were intact and soon its debts would be overcome through "manipulation". In a short time, he believed, the German economy would once again be much stronger than the French.

France's leverage was jeopardized repeatedly by Clemenceau's mistrust of Wilson and

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

, as well as his intense dislike of President Poincaré. When negotiations reached a stalemate, Clemenceau had a habit of shouting at the other heads of state and storming out of the room rather than participating in further discussion.

Attempted assassination

On 19 February 1919, as Clemenceau was leaving his apartment, a man fired several shots at the car. Clemenceau's assailant, anarchist

Émile Cottin, was nearly lynched. Clemenceau's assistant found him pale, but conscious. "They shot me in the back", Clemenceau told him. "They didn't even dare to attack me from the front." One bullet hit Clemenceau between the ribs, just missing his vital organs. Too dangerous to remove, the bullet remained with him for the rest of his life.

Clemenceau often joked about the "assassin's" bad marksmanship – "We have just won the most terrible war in history, yet here is a Frenchman who misses his target six out of seven times at point-blank range. Of course this fellow must be punished for the careless use of a dangerous weapon and for poor marksmanship. I suggest that he be locked up for eight years, with intensive training in a shooting gallery."

Rhineland and the Saar

When Clemenceau returned to the Council of Ten on 1 March, he found that little had changed. One issue that had not changed at all was the long-running dispute over France's eastern frontier and control of the German

Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

. Clemenceau believed that Germany's possession of this territory left France without a natural frontier in the east and thus, was vulnerable to invasion. The British ambassador reported in December 1918 on Clemenceau's views on the future of the Rhineland: "He said that the Rhine was a natural boundary of Gaul and Germany and that it ought to be made the German boundary now, the territory between the Rhine and the French frontier being made into an Independent State whose neutrality should be guaranteed by the great powers."

Finally, the issue was resolved when Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson guaranteed immediate military assistance if Germany attacked without provocation. It also was decided that the allies would occupy the territory for fifteen years, and that Germany could never rearm the area. Lloyd George insisted on a clause allowing for the early withdrawal of allied troops if the Germans fulfilled the treaty; Clemenceau inserted Article 429 into the treaty that permitted allied occupation beyond the fifteen years if adequate guarantees for allied security against unprovoked aggression were not met. This was in case the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the

Treaty of Guarantee, thereby making null and void the British guarantee as well, since that was dependent on the Americans being part of it. This is, in fact, what did occur. Article 429 ensured that a refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify the treaties of guarantee would not weaken them.

President Poincaré and Marshal

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Ar ...

both pressed repeatedly for an autonomous Rhineland state. Foch thought the Treaty of Versailles was too lenient on Germany, stating "This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years." At a cabinet meeting on 25 April Foch spoke against the deal Clemenceau had brokered and pushed for a separate Rhineland. On 28 April Poincaré sent Clemenceau a long letter detailing why he thought allied occupation should continue until Germany had paid all her reparations. Clemenceau replied that the alliance with America and Britain was of more value than an isolated France that held onto the Rhineland: "In fifteen years I will be dead, but if you do me the honour of visiting my tomb, you will be able to say that the Germans have not fulfilled all the clauses of the treaty, and that we are still on the Rhine." Clemenceau said to Lloyd George in June, "We need a barrier behind which, in the years to come, our people can work in security to rebuild its ruins. The barrier is the Rhine. I must take national feelings into account. That does not mean that I am afraid of losing office. I am quite indifferent on that point. But I will not, by giving up the occupation, do something which will break the willpower of our people." Later, he said to Jean Martel, "The policy of Foch and Poincaré was bad in principle. It was a policy no Frenchman, no republican Frenchman could accept for a moment, except in the hope of obtaining other guarantees, other advantages. We leave that sort of thing to

Bismarck."

There was increasing discontent among Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Woodrow Wilson about slow progress and information leaks surrounding the Council of Ten. They began to meet in a smaller group, called the Council of Four,

Vittorio Orlando

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (19 May 1860 – 1 December 1952) was an Italian statesman, who served as the Prime Minister of Italy from October 1917 to June 1919. Orlando is best known for representing Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with h ...

of Italy being the fourth, although less weighty, member. This offered greater privacy and security and increased the efficiency of the decision-making process. Another major issue that the Council of Four discussed was the future of the German

Saar

Saar or SAAR has several meanings:

People Given name

*Saar Boubacar (born 1951), Senegalese professional football player

* Saar Ganor, Israeli archaeologist

*Saar Klein (born 1967), American film editor

Surname

* Ain Saar (born 1968), Est ...

region. Clemenceau believed that France was entitled to the region and its coal mines after Germany deliberately damaged the coal mines in northern France. Wilson, however, resisted the French claim so firmly that Clemenceau accused him of being "pro-German". Lloyd George came to a compromise; the coal mines were given to France and the territory placed under French administration for 15 years, after which a vote would determine whether the region would rejoin Germany.

Although Clemenceau had little knowledge of the defunct Austrian-Hungarian empire, he supported the causes of its smaller ethnic groups and his adamant stance led to the stringent terms in the

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

that dismantled Hungary. Rather than recognizing territories of the Austrian-Hungarian empire solely within the principles of self-determination, Clemenceau sought to weaken Hungary, just as Germany was, and to remove the threat of such a large power within Central Europe. The entire Czechoslovakian state was seen a potential buffer from Communism and this encompassed majority Hungarian territories.

Reparations

Clemenceau was not experienced in the fields of economics or finance, and as

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

pointed out, "he did not trouble his head to understand either the Indemnity or

rance'soverwhelming financial difficulties", but he was under strong public and parliamentary pressure to make Germany's

reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

bill as large as possible. Generally, it was agreed that Germany should not pay more than it could afford, but the estimates of what it could afford varied greatly. Figures ranged between £2,000 million and £20,000 million. Clemenceau realised that any compromise would anger both the French and British citizens and that the only option was to establish a reparations commission that would examine Germany's capacity for reparations. This meant that the French government was not directly involved in the issue of reparations.

Defence of the treaty

The

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

was signed on 28 June 1919. Clemenceau now had to defend the treaty against critics who viewed the compromises he had negotiated as inadequate for French national interests. The French Parliament debated the treaty and

Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the introduction (in Jul ...

on 24 September claimed that the

U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

would not vote for the Treaty of Guarantee or the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

and therefore, it would have been wiser to have the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

as a frontier. Clemenceau replied that he was sure the Senate would ratify both and that he had inserted Article 429 into the treaty, providing for "new arrangements concerning the Rhine". This interpretation of Article 429 was disputed by Barthou.

Clemenceau's main speech on the treaty was delivered on 25 September. He said that he knew the treaty was not perfect, but that the war had been fought by a coalition and therefore, the treaty would express the lowest common denominator of those involved. He claimed criticisms of the details of the treaty were misleading; that critics should look at the treaty as a whole and see how they could benefit from it:

The treaty, with all its complex clauses, will only be worth what you are worth; it will be what you make it ... What you are going to vote to-day is not even a beginning, it is a beginning of a beginning. The ideas it contains will grow and bear fruit. You have won the power to impose them on a defeated Germany. We are told that she will revive. All the more reason not to show her that we fear her ... M. Marin went to the heart of the question, when he turned to us and said in despairing tones, "You have reduced us to a policy of vigilance." Yes, M. Marin, do you think that one could make a treaty which would do away with the need for vigilance among the nations of Europe who only yesterday were pouring out their blood in battle? Life is a perpetual struggle in war, as in peace ... That struggle cannot be avoided. Yes, we must have vigilance, we must have a great deal of vigilance. I cannot say for how many years, perhaps I should say for how many centuries, the crisis which has begun will continue. Yes, this treaty will bring us burdens, troubles, miseries, difficulties, and that will continue for long years.

The Chamber of Deputies ratified the treaty by 372 votes to 53, with the Senate voting unanimously for its ratification. On 11 October Clemenceau gave his last parliamentary speech, addressed to the Senate. He said that any attempt to partition Germany would be self-defeating and that France must find a way of living with sixty million Germans. He also said that the bourgeoisie, like the aristocracy before them in the ''ancien régime'', had failed as a ruling class. It was now the turn of the working class to rule. He advocated national unity and a demographic revolution: "The treaty does not state that France will have many children, but it is the first thing that should have been written there. For if France does not have large families, it will be in vain that you put all the finest clauses in the treaty, that you take away all the Germans guns, France will be lost because there will be no more French".

Domestic policies

Clemenceau's final tenure as prime minister witnessed the implementation of various reforms aimed at regulating the hours of labour. A general

eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

law passed in April 1919 amending the French Labour Code, and in June that year, existing legislation concerning the duration of the working day in the mining industry was amended by extending the eight-hour day to all classes of workers, "whether employed underground or on the surface". Under a previous law of December 1913, the eight-hour limit had only applied to workers employed underground. In August 1919, a similar limit was introduced for all those employed in French vessels. Another law passed in 1919 (which came into operation in October 1920) prohibited employment in bakeries between the hours of 10 P.M. and 4 A.M. A decree of May 1919 introduced the eight-hour day for workers on trams, railways, and in inland waterways, and a second of June 1919 extended this provision to the state railways. In April 1919, an enabling act was approved for an eight-hour day and a six-day work week, although farm workers were excluded from the act.

Presidential bid

In 1919, France adopted a new electoral system and the

legislative election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

gave the

National Bloc (a coalition of right-wing parties) a majority. Clemenceau only intervened once in the election campaign, delivering a speech on 4 November at Strasbourg, praising the manifesto and men of the National Bloc and he urged that the victory in the war needed to be safeguarded by vigilance. In private he was concerned at this huge swing to the right.

His friend,

Georges Mandel

Georges Mandel (5 June 1885 – 7 July 1944) was a French journalist, politician, and French Resistance leader.

Early life

Born Louis George Rothschild in Chatou, Yvelines, he was the son of a tailor and his wife. His family was Jewish, originally ...

, urged Clemenceau to stand for the presidency in the upcoming election and on 15 January 1920 he let Mandel announce that he would be prepared to serve if elected. However, Clemenceau did not intend to campaign for the post, instead he wished to be chosen by acclaim as a national symbol. The preliminary meeting of the republican caucus (a forerunner to the vote in the National Assembly) chose

Paul Deschanel

Paul Eugène Louis Deschanel (; 13 February 1855, in Schaerbeek28 April 1922) was a French politician. He served as President of France from 18 February to 21 September 1920.

Biography

Paul Deschanel, the son of Émile Deschanel (1819–190 ...

instead of Clemenceau by a vote of 408 to 389. In response, Clemenceau refused to be put forward for the vote in the National Assembly because he did not want to win by a small majority, but by a near-unanimous vote. Only then, he claimed, could he negotiate with confidence with the allies.

In his last speech to the cabinet on 18 January he said, "We must show the world the extent of our victory, and we must take up the mentality and habits of a victorious people, which once more takes its place at the head of Europe. But all that will now be placed in jeopardy ... It will take less time and less thought to destroy the edifice so patiently and painfully erected than it took to complete it. Poor France. The mistakes have begun already."

[Watson, p. 387.]

Last years

Clemenceau resigned as prime minister as soon as the presidential election was held (17 January 1920) and took no further part in politics. In private, he condemned the unilateral occupation by French troops of the German city of

Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

in 1920 and said if he had been in power, he would have persuaded the British to join it.

He took a holiday in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and the

Sudan from February to April 1920, then embarked for the Far East in September, returning to France in March 1921. In June, he visited England and received an honorary degree from the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

. He met

Lloyd George and said to him that after the armistice he had become the enemy of France. Lloyd George replied, "Well, was not that always our traditional policy?" He was joking, but after reflection, Clemenceau took it seriously. After Lloyd George's fall from power in 1922 Clemenceau remarked, "As for France, it is a real enemy who disappears. Lloyd George did not hide it: at my last visit to London he cynically admitted it".

In late 1922, Clemenceau gave a lecture tour in the major cities of the American northeast. He defended the policy of France, including war debts and reparations, and condemned

American isolationism. He was well received and attracted large audiences, but America's policy remained unchanged. On 9 August 1926, he wrote an open letter to the American President

Calvin Coolidge that argued against France paying all its war debts: "France is not for sale, even to her friends". This appeal went unheard.

He condemned Poincaré's