Grimoire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient

One such Arabic grimoire devoted to astral magic, the 10th-century ''Ghâyat al-Hakîm'', was later translated into Latin and circulated in Europe during the 13th century under the name of the ''

One such Arabic grimoire devoted to astral magic, the 10th-century ''Ghâyat al-Hakîm'', was later translated into Latin and circulated in Europe during the 13th century under the name of the ''

The advent of printing in Europe meant that books could be mass-produced for the first time and could reach an ever-growing literate audience. Among the earliest books to be printed were magical texts. The ''nóminas'' were one example, consisting of prayers to the saints used as talismans. It was particularly in Protestant countries, such as Switzerland and the German states, which were not under the domination of the Roman Catholic Church, where such grimoires were published.

Despite the advent of print, however, handwritten grimoires remained highly valued, as they were believed to contain inherent magical powers, and they continued to be produced. With increasing availability, people lower down the social scale and women began to have access to books on magic; this was often incorporated into the popular

The advent of printing in Europe meant that books could be mass-produced for the first time and could reach an ever-growing literate audience. Among the earliest books to be printed were magical texts. The ''nóminas'' were one example, consisting of prayers to the saints used as talismans. It was particularly in Protestant countries, such as Switzerland and the German states, which were not under the domination of the Roman Catholic Church, where such grimoires were published.

Despite the advent of print, however, handwritten grimoires remained highly valued, as they were believed to contain inherent magical powers, and they continued to be produced. With increasing availability, people lower down the social scale and women began to have access to books on magic; this was often incorporated into the popular

In Germany, with the increased interest in

In Germany, with the increased interest in

Internet Sacred Text Archives: Grimoires

*

Scandinavian folklore

{{Fantasy fiction Fiction about magic Magic (supernatural) Magic items Non-fiction genres Religious objects Western esotericism

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a

A grimoire ( ) (also known as a "book of spells" or a "spellbook") is a textbook

A textbook is a book containing a comprehensive compilation of content in a branch of study with the intention of explaining it. Textbooks are produced to meet the needs of educators, usually at educational institutions. Schoolbooks are textboo ...

of magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed perm ...

and amulets

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects ...

, how to perform magical spell

Spell(s) or The Spell(s) may refer to:

Processes

* Spell (paranormal), an incantation

* Spell (ritual), a magical ritual

* Spelling, the writing of words

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Spell'' (1977 film), an American t ...

s, charms

Charm may refer to:

Social science

* Charisma, a person or thing's pronounced ability to attract others

* Superficial charm, flattery, telling people what they want to hear

Science and technology

* Charm quark, a type of elementary particle

* Cha ...

and divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

, and how to summon

Evocation is the act of evoking, calling upon, or summoning a spirit, demon, deity or other supernatural agents, in the Western mystery tradition. Comparable practices exist in many religions and magical traditions and may employ the use of m ...

or invoke supernatural entities such as angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles include ...

s, spirits

Spirit or spirits may refer to:

Liquor and other volatile liquids

* Spirits, a.k.a. liquor, distilled alcoholic drinks

* Spirit or tincture, an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol

* Volatile (especially flammable) liquids, ...

, deities

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

, and demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, ani ...

s.Davies (2009:1) In many cases, the books themselves are believed to be imbued with magical powers, although in many cultures, other sacred texts that are not grimoires (such as the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

) have been believed to have supernatural properties intrinsically. The only contents found in a grimoire would be information on spells, rituals

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, ...

, the preparation of magical tools, and lists of ingredients and their magical correspondences

A table of magical correspondences is a list of magical correspondences between items belonging to different categories, such as correspondences between certain deities, heavenly bodies, plants, perfumes, precious stones, etc. Such lists were co ...

. In this manner, while all ''books on magic'' could be thought of as grimoires, not all ''magical books'' should be thought of as grimoires.

While the term ''grimoire'' is originally European—and many Europeans throughout history, particularly ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic (ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories to aid the practitioner. It can be seen as an ex ...

ians and cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services a ...

, have used grimoires—the historian Owen Davies has noted that similar books can be found all around the world, ranging from Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

to Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

. He also noted that in this sense, the world's first grimoires were created in Europe and the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

.

Etymology

It is most commonly believed that the term ''grimoire'' originated from theOld French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

word ''grammaire'', which had initially been used to refer to all books written in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. By the 18th century, the term had gained its now common usage in France, and had begun to be used to refer purely to books of magic. Owen Davies presumed this was because "many of them continued to circulate in Latin manuscripts".

However, the term ''grimoire'' later developed into a figure of speech

A figure of speech or rhetorical figure is a word or phrase that intentionally deviates from ordinary language use in order to produce a rhetorical effect. Figures of speech are traditionally classified into '' schemes,'' which vary the ordinary ...

amongst the French indicating something which was hard to understand. In the 19th century, with the increasing interest in occultism

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism an ...

amongst the British following the publication of Francis Barrett's '' The Magus'' (1801), the term entered the English language in reference to books of magic.

History

Ancient period

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

(modern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

), where they have been found inscribed on cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

clay tablets that archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

excavated from the city of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Harm ...

and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. The ancient Egyptians also employed magical incantations, which have been found inscribed on amulets and other items. The Egyptian magical system, known as heka Heka may refer to:

* Heka (god), the deification of magic in Egyptian mythology

* Lambda Orionis, a star in the constellation of Orion, also known by the traditional names "Meissa" and "Heka"

* Phenom II

Phenom II is a family of AMD's multi-core ...

, was greatly altered and expanded after the Macedonians, led by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, invaded Egypt in 332 BC.Davies (2009:8–9)

Under the next three centuries of Hellenistic Egypt, the Coptic

Coptic may refer to:

Afro-Asia

* Copts, an ethnoreligious group mainly in the area of modern Egypt but also in Sudan and Libya

* Coptic language, a Northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century

* Coptic alphabet ...

writing system evolved, and the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

was opened. This likely had an influence upon books of magic, with the trend on known incantations switching from simple health and protection charms to more specific things, such as financial success and sexual fulfillment. Around this time the legendary figure of Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from grc, Wiktionary:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς ὁ Τρισμέγιστος, "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest"; Classical Latin: la, label=none, Mercurius ter Maximus) is a legendary Hellenistic figure that originated as a Syn ...

developed as a conflation of the Egyptian god Thoth

Thoth (; from grc-koi, Θώθ ''Thṓth'', borrowed from cop, Ⲑⲱⲟⲩⲧ ''Thōout'', Egyptian: ', the reflex of " eis like the Ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or a ...

and the Greek Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

; this figure was associated with writing and magic and, therefore, of books on magic.Davies (2009:10)

The ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cultu ...

and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

believed that books on magic were invented by the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

. The 1st-century AD writer Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

stated that magic had been first discovered by the ancient philosopher Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label=New Persian, Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastria ...

around the year 647 BC but that it was only written down in the 5th century BC by the magician Osthanes

Ostanes (from Ancient Greek, Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persians, Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudepigraphy, pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic ...

. His claims are not, however, supported by modern historians.Davies (2009:7)

The ancient Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

people were often viewed as being knowledgeable in magic, which, according to legend, they had learned from Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

, who had learned it in Egypt. Among many ancient writers, Moses was seen as an Egyptian rather than a Jew. Two manuscripts likely dating to the 4th century, both of which purport to be the legendary eighth Book of Moses (the first five being the initial books in the Biblical Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

), present him as a polytheist

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the b ...

who explained how to conjure gods and subdue demons.

Meanwhile, there is definite evidence of grimoires being used by certain—particularly Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

—sects of early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

. In the '' Book of Enoch'' found within the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

, for instance, there is information on astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of Celestial o ...

and the angels. In possible connection with the ''Book of Enoch'', the idea of Enoch

Enoch () ''Henṓkh''; ar, أَخْنُوخ ', Qur'ān.html"_;"title="ommonly_in_Qur'ān">ommonly_in_Qur'ānic_literature__'_is_a_biblical_figure_and_Patriarchs_(Bible).html" "title="Qur'ānic_literature.html" ;"title="Qur'ān.html" ;"title="o ...

and his great-grandson Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5– ...

having some involvement with books of magic given to them by angels continued through to the medieval period.

Israelite King Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

was a Biblical figure associated with magic and sorcery in the ancient world. The 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

mentioned a book circulating under the name of Solomon that contained incantations for summoning demons and described how a Jew called Eleazar used it to cure cases of possession. The book may have been the ''Testament of Solomon

The Testament of Solomon is a pseudepigraphical composite text ascribed to King Solomon but not regarded as canonical scripture by Jews or Christian groups. It was written in the Greek language, based on precedents dating back to the early 1st mil ...

'' but was more probably a different work. The pseudepigraphic

Pseudepigrapha (also anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past.Bauckham, Richard; "Pseu ...

''Testament of Solomon'' is one of the oldest magical texts. It is a Greek manuscript attributed to Solomon and was likely written in either Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

or Egypt sometime in the first five centuries AD; over 1,000 years after Solomon's death.

The work tells of the building of The Temple and relates that construction was hampered by demons until the archangel

Archangels () are the second lowest rank of angel in the hierarchy of angels. The word ''archangel'' itself is usually associated with the Abrahamic religions, but beings that are very similar to archangels are found in a number of other relig ...

Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

gave the King a magical ring. The ring, engraved with the Seal of Solomon

The Seal of Solomon or Ring of Solomon ( he, חותם שלמה, '; ar, خاتم سليمان, ') is the legendary signet ring attributed to the Israelite king Solomon in medieval mystical traditions, from which it developed in parallel within ...

, had the power to bind demons from doing harm. Solomon used it to lock demons in jars and commanded others to do his bidding, although eventually, according to the ''Testament'', he was tempted into worshiping "false gods", such as Moloch

Moloch (; ''Mōleḵ'' or הַמֹּלֶךְ ''hamMōleḵ''; grc, Μόλοχ, la, Moloch; also Molech or Molek) is a name or a term which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the book of Leviticus. The Bible strongly co ...

, Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during Ancient Near East, antiquity. From its use among people, it cam ...

, and Rapha. Subsequently, after losing favour with God, King Solomon wrote the work as a warning and a guide to the reader.

When Christianity became the dominant faith of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, the early Church frowned upon the propagation of books on magic, connecting it with paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christianity, early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions ot ...

, and burned books of magic. The New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

records that after the unsuccessful exorcism

Exorcism () is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons, jinns, or other malevolent spiritual entities from a person, or an area, that is believed to be possessed. Depending on the spiritual beliefs of the exorcist, this may be ...

by the seven sons of Sceva Sceva ( grc-gre, Σκευᾶς, Skeuas) was a Jew called a " chief priest" in , although whether he was a chief priest is disputed by some writers. Although there was no high priest in Jerusalem by this name, some scholars note that it was not unco ...

became known, many converts decided to burn their own magic and pagan books in the city of Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

; this advice was adopted on a large scale after the Christian ascent to power.

Medieval period

In theMedieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

period, the production of grimoires continued in Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

, as well as amongst Jews and the followers of the newly founded Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic faith. As the historian Owen Davies noted, "while the hristianChurch was ultimately successful in defeating pagan worship it never managed to demarcate clearly and maintain a line of practice between religious devotion and magic." The use of such books on magic continued. In Christianised Europe, the Church divided books of magic into two kinds: those that dealt with "natural magic

Natural magic in the context of Renaissance magic is that part of the occult which deals with natural forces directly, as opposed to ceremonial magic which deals with the summoning of spirits. Natural magic sometimes makes use of physical substanc ...

" and those that dealt in "demonic magic".Davies (2009:22)

The former was acceptable because it was viewed as merely taking note of the powers in nature that were created by God; for instance, the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

leechbooks, which contained simple spells for medicinal purposes, were tolerated. Demonic magic was not acceptable, because it was believed that such magic did not come from God, but from the Devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of t ...

and his demons. These grimoires dealt in such topics as necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of magic or black magic involving communication with the dead by summoning their spirits as apparitions or visions, or by resurrection for the purpose of divination; imparting the means to foretell future events; ...

, divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout histor ...

and demonology

Demonology is the study of demons within religious belief and myth. Depending on context, it can refer to studies within theology, religious doctrine, or pseudoscience. In many faiths, it concerns the study of a hierarchy of demons. Demons may b ...

. Despite this, "there is ample evidence that the mediaeval clergy were the main practitioners of magic and therefore the owners, transcribers, and circulators of grimoires," while several grimoires were attributed to Popes

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

.

One such Arabic grimoire devoted to astral magic, the 10th-century ''Ghâyat al-Hakîm'', was later translated into Latin and circulated in Europe during the 13th century under the name of the ''

One such Arabic grimoire devoted to astral magic, the 10th-century ''Ghâyat al-Hakîm'', was later translated into Latin and circulated in Europe during the 13th century under the name of the ''Picatrix

''Picatrix'' is the Latin name used today for a 400-page book of magic and astrology originally written in Arabic under the title ''Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm'' ( ar, غاية الحكيم), which most scholars assume was originally written in the midd ...

''. However, not all such grimoires of this era were based upon Arabic sources. The 13th-century ''Sworn Book of Honorius'', for instance, was (like the ancient ''Testament of Solomon'' before it) largely based on the supposed teachings of the Biblical king Solomon and included ideas such as prayers and a ritual circle

A magic circle is a circle of space marked out by practitioners of some branches of ritual magic, which they generally believe will contain energy and form a sacred space, or will provide them a form of magical protection, or both. It may be marke ...

, with the mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

purpose of having visions of God, Hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell ...

, and Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

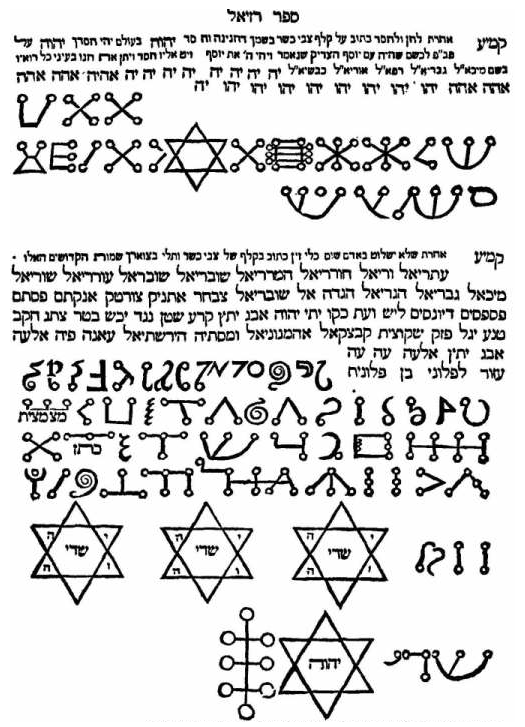

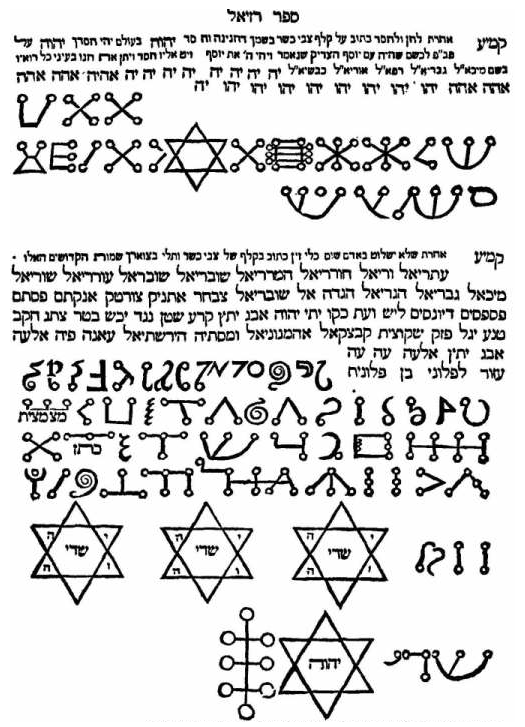

and gaining much wisdom and knowledge as a result. Another was the Hebrew '' Sefer Raziel Ha-Malakh'', translated in Europe as the ''Liber Razielis Archangeli''.

A later book also claiming to have been written by Solomon was originally written in Greek during the 15th century, where it was known as the ''Magical Treatise of Solomon

The ''Magical Treatise of Solomon'', sometimes known as ''Hygromanteia'' ( grc-gre, Ὑγρομαντεία) or ''Hygromancy of Solomon'', the ''Solomonikê''Rankine, pp. 98–100 in Lycourinos. (Σολομωνική), or even ''Little Key of the W ...

'' or the ''Little Key of the Whole Art of Hygromancy, Found by Several Craftsmen and by the Holy Prophet Solomon''. In the 16th century, this work had been translated into Latin and Italian, being renamed the ''Clavicula Salomonis'', or the ''Key of Solomon

The ''Key of Solomon'' ( la, Clavicula Salomonis; he, מפתח שלמה []) (Also known as "The Greater Key of Solomon") is a pseudepigraphical grimoire (also known as a book of spells) attributed to Solomon, King Solomon. It probably dates ba ...

''.

In Christendom during the medieval age, grimoires were written that were attributed to other ancient figures, thereby supposedly giving them a sense of authenticity because of their antiquity. The German abbot and occultist Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius (; 1 February 1462 – 13 December 1516), born Johann Heidenberg, was a German Benedictine abbot and a polymath who was active in the German Renaissance as a lexicographer, chronicler, cryptographer, and occultist. He is consi ...

(1462–1516) supposedly had a ''Book of Simon the Magician'', based upon the New Testament figure of Simon Magus

Simon Magus (Greek Σίμων ὁ μάγος, Latin: Simon Magus), also known as Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, was a religious figure whose confrontation with Peter is recorded in Acts . The act of simony, or paying for position, is ...

. Simon Magus had been a contemporary of Jesus Christ's and—like the Biblical Jesus

The life of Jesus in the New Testament is primarily outlined in the four canonical gospels, which includes his genealogy and Nativity of Jesus, nativity, Ministry of Jesus, public ministry, Passion of Jesus, passion, prophecy, Resurrection of ...

—had supposedly performed miracles, but had been demonized by the Medieval Church as a devil worshiper and evil individual.

Similarly, it was commonly believed by medieval people that other ancient figures, such as the poet Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, astronomer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, and philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, had been involved in magic, and grimoires claiming to have been written by them were circulated. However, there were those who did not believe this; for instance, the Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ol ...

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

(c. 1214–94) stated that books falsely claiming to be by ancient authors "ought to be prohibited by law."

Early modern period

As the early modern period commenced in the late 15th century, many changes began to shock Europe that would have an effect on the production of grimoires. Historian Owen Davies classed the most important of these as theProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, and subsequent Catholic Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

; The Witch-hunts, and the advent of printing. The Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

saw the continuation of interest in magic that had been found in the Medieval period, and in this period, there was an increased interest in Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

among occultists and ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic (ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories to aid the practitioner. It can be seen as an ex ...

ians in Europe, largely fueled by the 1471 translation of the ancient ''Corpus hermeticum'' into Latin by Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of ...

(1433–99).

Alongside this, there was a rise in interest in the Jewish mysticism

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941), distinguishes between different forms of mysticism across different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbalah, which emerged in 1 ...

known as the Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and Jewish theology, school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "rece ...

, which was spread across the continent by Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (24 February 1463 – 17 November 1494) was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, philosophy, ...

and Johannes Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin (; sometimes called Johannes; 29 January 1455 – 30 June 1522) was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew, whose work also took him to modern-day Austria, Switzerland, and Italy and France. Most of Reuchlin's ...

. The most important magician of the Renaissance was Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' published in 1533 drew ...

(1486–1535), who widely studied occult topics and earlier grimoires and eventually published his own, the ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy

''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' (''De Occulta Philosophia libri III'') is Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's study of occult philosophy, acknowledged as a significant contribution to the Renaissance philosophical discussion concerning the power ...

'', in 1533. A similar figure was the Swiss magician known as Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

He w ...

(1493–1541), who published '' Of the Supreme Mysteries of Nature'', in which he emphasised the distinction between good and bad magic. A third such individual was Johann Georg Faust

Johann Georg Faust (; c. 1480 or 1466 – c. 1541), also known in English as John Faustus , was a German itinerant alchemist, astrologer, and magician of the German Renaissance.

''Doctor Faust'' became the subject of folk legend in the de ...

, upon whom several pieces of later literature were written, such as Christopher Marlow

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

e's '' Doctor Faustus'', that portrayed him as consulting with demons.

The idea of demonology had remained strong in the Renaissance, and several demonological grimoires were published, including ''The Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy'', which falsely claimed to having been authored by Cornelius Agrippa, and the ''Pseudomonarchia Daemonum

''Pseudomonarchia Daemonum'', or ''False Monarchy of Demons'', first appears as an Appendix to ''De praestigiis daemonum'' (1577) by Johann Weyer.Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (Liber officiorum spirituum); Johann Weyer, ed. Joseph Peterson; 2000. Avai ...

'', which listed 69 demons. To counter this, the Roman Catholic Church authorised the production of many works of exorcism, the rituals of which were often very similar to those of demonic conjuration. Alongside these demonological works, grimoires on natural magic continued to be produced, including ''Magia Naturalis

' (in English, ''Natural Magic'') is a work of popular science by Giambattista della Porta first published in Naples in 1558. Its popularity ensured it was republished in five Latin editions within ten years, with translations into Italian (1560 ...

'', written by Giambattista Della Porta

Giambattista della Porta (; 1535 – 4 February 1615), also known as Giovanni Battista Della Porta, was an Italian scholar, polymath and playwright who lived in Naples at the time of the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution and Reformation.

Giamba ...

(1535–1615).

Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

held magical traditions in regional work as well, most remarkably the Galdrabók

The (, ''Book of Magic'') is an Icelandic grimoire dated to ca. 1600. It is a small manuscript containing a collection of 47 spells and sigils/staves.

The grimoire was compiled by four people, possibly starting in the late 16th century and going ...

, where numerous symbols of mystic origin are dedicated to the practitioner. These pieces give a perfect fusion of Germanic pagan

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germ ...

and Christian influence, seeking splendid help from the Norse gods

Norse is a demonym for Norsemen, a medieval North Germanic ethnolinguistic group ancestral to modern Scandinavians, defined as speakers of Old Norse from about the 9th to the 13th centuries.

Norse may also refer to:

Culture and religion

* Nors ...

and referring to the titles of demons.

The advent of printing in Europe meant that books could be mass-produced for the first time and could reach an ever-growing literate audience. Among the earliest books to be printed were magical texts. The ''nóminas'' were one example, consisting of prayers to the saints used as talismans. It was particularly in Protestant countries, such as Switzerland and the German states, which were not under the domination of the Roman Catholic Church, where such grimoires were published.

Despite the advent of print, however, handwritten grimoires remained highly valued, as they were believed to contain inherent magical powers, and they continued to be produced. With increasing availability, people lower down the social scale and women began to have access to books on magic; this was often incorporated into the popular

The advent of printing in Europe meant that books could be mass-produced for the first time and could reach an ever-growing literate audience. Among the earliest books to be printed were magical texts. The ''nóminas'' were one example, consisting of prayers to the saints used as talismans. It was particularly in Protestant countries, such as Switzerland and the German states, which were not under the domination of the Roman Catholic Church, where such grimoires were published.

Despite the advent of print, however, handwritten grimoires remained highly valued, as they were believed to contain inherent magical powers, and they continued to be produced. With increasing availability, people lower down the social scale and women began to have access to books on magic; this was often incorporated into the popular folk magic

In religious studies and folkloristics, folk religion, popular religion, traditional religion or vernacular religion comprises various forms and expressions of religion that are distinct from the official doctrines and practices of organized rel ...

of the average people and, in particular, that of the cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services a ...

, who were professionally involved in folk magic. These works left Europe and were imported to the parts of Latin America controlled by the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

and Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

empires and the parts of North America controlled by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

empires.

Throughout this period, the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

, a Roman Catholic organisation, had organised the mass suppression of peoples and beliefs that they considered heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. In many cases, grimoires were found in the heretics' possessions and destroyed. In 1599, the church published the ''Indexes of Prohibited Books'', in which many grimoires were listed as forbidden, including several mediaeval ones, such as the ''Key of Solomon'', which were still popular.

In Christendom, there also began to develop a widespread fear of witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

, which was believed to be Satanic in nature. The subsequent hysteria, known as The Witch-hunts, caused the death of around 40,000 people, most of whom were women. Sometimes, those found with grimoires—particularly demonological ones—were prosecuted and dealt with as witches but, in most cases, those accused had no access to such books. Iceland—which had a relatively high literacy rate—proved an exception to this, with a third of the 134 witch trials held involving people who had owned grimoires. By the end of the Early Modern period, and the beginning of the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, many European governments brought in laws prohibiting many superstitious beliefs in an attempt to bring an end to the Witch Hunts; this would invariably affect the release of grimoires.

Meanwhile, Hermeticism and the Kabbalah would influence the creation of a mystical philosophy known as Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts purported to announce the existence of a hitherto unknown esoteric order to the world and made seeking its ...

, which first appeared in the early 17th century, when two pamphlets detailing the existence of the mysterious Rosicrucian group were published in Germany. These claimed that Rosicrucianism had originated with a Medieval figure known as Christian Rosenkreuz

Christian Rosenkreuz (also spelled Rosenkreutz, Rosencreutz, Christiani Rosencreütz and Christian Rose Cross) is the legendary, possibly allegorical, founder of the Rosicrucian Order (Order of the Rose Cross). He is presented in three manifest ...

, who had founded the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross; however, there was no evidence for the existence of Rosenkreuz or the Brotherhood.

18th and 19th centuries

The 18th century saw the rise of theEnlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, a movement devoted to science and rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

, predominantly amongst the ruling classes. However, amongst much of Europe, belief in magic and witchcraft persisted, as did the witch trials in certain areas. Governments tried to crack down on magicians and fortune tellers

Fortune telling is the practice of predicting information about a person's life. Melton, J. Gordon. (2008). ''The Encyclopedia of Religious Phenomena''. Visible Ink Press. pp. 115-116. The scope of fortune telling is in principle identical wi ...

, particularly in France, where the police viewed them as social pests who took money from the gullible, often in a search for treasure. In doing so, they confiscated many grimoires.

Beginning in the 17th century, a new, ephemeral form of printed literature developed in France; the ''Bibliothèque bleue

' ("blue library" in French) is a type of ephemera and popular literature published in Early Modern France (between and ), comparable to the English chapbook and the German '. As was the case in England and Germany, that literary format appealed ...

''. Many grimoires published through this circulated among a growing percentage of the populace; in particular, the ''Grand Albert

The ''Grand Albert'' is a grimoire that has often been attributed to Albertus Magnus. Begun perhaps around 1245, it received its definitive form in Latin around 1493, a French translation in 1500, and its most expansive and well-known French ed ...

'', the ''Petit Albert

''Petit Albert'' (English: ''Lesser Albert'') is an 18th-century grimoire of natural and cabalistic magic. The ''Petit Albert'' is possibly inspired by the writings of Albertus Parvus Lucius (the Lesser Albert). Brought down to the smallest ha ...

'' (1782), the ''Grimoire du Pape Honorius'', and the '' Enchiridion Leonis Papae''. The ''Petit Albert'' contained a wide variety of magic; for instance, dealing in simple charms for ailments, along with more complex things, such as the instructions for making a Hand of Glory.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, following the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

of 1789, a hugely influential grimoire was published under the title of the ''Grand Grimoire

''The Grand Grimoire'' is a black magic grimoire. Different editions date the book to 1521, 1522 or 1421, but it was probably written during the early 19th century. Owen Davies suggests 1702 is when the first edition may have been created and a ...

'', which was considered particularly powerful, because it involved conjuring and making a pact with the devil's chief minister, Lucifugé Rofocale, to gain wealth from him. A new version of this grimoire was later published under the title of the ''Dragon rouge'' and was available for sale in many Parisian bookstores. Similar books published in France at this time included the '' Black Pullet'' and the ''Grimoirium Verum

The ''Grimorium Verum'' (Latin for ''True Grimoire'') is an 18th-century grimoire attributed to one "Alibeck the Egyptian" of Memphis, who purportedly wrote in 1517. Like many grimoires, it claims a tradition originating with King Solomon.

The gr ...

''. The ''Black Pullet'', probably authored in late-18th-century Rome or France, differs from the typical grimoires in that it does not claim to be a manuscript from antiquity, but told by a man who was a member of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's armed expeditionary forces in Egypt.

The widespread availability of printed grimoires in France—despite the opposition of both the rationalists and the church—soon spread to neighbouring countries, such as Spain and Germany. In Switzerland, Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

was commonly associated with the occult at the time, particularly by Catholics, because it had been a stronghold of Protestantism. Many of those interested in the esoteric traveled from Roman Catholic nations to Switzerland to purchase grimoires or to study with occultists. Soon, grimoires appeared that involved Catholic saints

This is an incomplete list of people and angels whom the Catholic Church has Canonization, canonized as saints. According to Catholic theology, all saints enjoy the beatific vision. Many of the Calendar of saints, saints listed here are to be f ...

; one example that appeared during the 19th century, and became relatively popular—particularly in Spain—was the ''Libro de San Cipriano'', or ''The Book of St. Ciprian'', which falsely claimed to date from c. 1000. As with most grimoires of this period, it dealt with (among other things) how to discover treasure.

In Germany, with the increased interest in

In Germany, with the increased interest in folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

during the 19th century, many historians took an interest in magic and in grimoires. Several published extracts of such grimoires in their own books on the history of magic, thereby helping to further propagate them. Perhaps the most notable of these was the Protestant pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

Georg Conrad Horst (1779–1832) who, from 1821 to 1826, published a six-volume collection of magical texts in which he studied grimoires as a peculiarity of the Medieval mindset.

Another scholar of the time interested in grimoires, the antiquarian bookseller Johann Scheible first published the ''Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses

The ''Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses'' is an 18th- or 19th-century magical text allegedly written by Moses, and passed down as hidden (or lost) books of the Hebrew Bible. Self-described as "the wonderful arts of the old Hebrews, taken fro ...

''; two influential magical texts that claimed to have been written by the ancient Jewish figure Moses. ''The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses'' were among the works which later spread to the countries of Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

, where—in Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish ance ...

and Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

—grimoires were known as black books

''Black Books'' is a British sitcom created by Dylan Moran and Graham Linehan, and written by Moran, Kevin Cecil, Andy Riley, Linehan and Arthur Mathews. It was broadcast on Channel 4, running for three series from 2000 to 2004. Starring Moran ...

and were commonly found among members of the army.

In Britain, new grimoires continued to be produced throughout the 18th century, such as Ebenezer Sibly

Ebenezer Sibly (1751 – 1799) was an English physician, astrologer and writer on the occult.

Life

He was the son of Edmund Sibly and Mary Larkholm, born in the parish of Cripplegate ward, London. He was the brother of Manoah Sibly. Early ...

's ''A New and Complete Illustration of the Celestial Science of Astrology''. In the last decades of that century, London experienced a revival of interest in the occult which was further propagated by Francis Barrett's publication of '' The Magus'' in 1801. ''The Magus'' contained many things taken from older grimoires—particularly those of Cornelius Agrippa—and, while not achieving initial popularity upon release, it gradually became an influential text.

One of Barrett's pupils, John Parkin, created his own handwritten grimoire ''The Grand Oracle of Heaven, or, The Art of Divine Magic'', although it was never published, largely because Britain was at war with France, and grimoires were commonly associated with the French. The only writer to publish British grimoires widely in the early 19th century was Robert Cross Smith, who released ''The Philosophical Merlin'' (1822) and ''The Astrologer of the Nineteenth Century'' (1825), but neither sold well.

In the late 19th century, several of these texts (including ''The Book of Abramelin

''The Book of Abramelin'' tells the story of an Egyptian mage named Abraham, or Abra-Melin, who taught a system of magic to Abraham of Worms, a Jew in Worms, Germany, presumed to have lived from –. The system of magic from this book regained ...

'' and the ''Key of Solomon'') were reclaimed by para-Masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to Fraternity, fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of Stonemasonry, stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their inte ...

magical organisations, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn ( la, Ordo Hermeticus Aurorae Aureae), more commonly the Golden Dawn (), was a secret society devoted to the study and practice of occult Hermeticism and metaphysics during the late 19th and early 20th ce ...

and the Ordo Templi Orientis

Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.; ) is an occult Initiation, initiatory organization founded at the beginning of the 20th century. The origins of the O.T.O. can be traced back to the German-speaking occultists Carl Kellner (mystic), Carl Kellner, He ...

.

20th and 21st centuries

'' The Secret Grimoire of Turiel'' claims to have been written in the 16th century, but no copy older than 1927 has been produced. A modern grimoire, the ''Simon Necronomicon

The ''Simon Necronomicon'' is a grimoire allegedly written by Peter Levenda (aka "Simon" from the introduction in the book). Materials presented in the book are a blend of ancient Middle Eastern elements, with allusions to the writings of H. P. ...

'', takes its name from a fictional book of magic in the stories of H. P. Lovecraft which was inspired by Babylonian mythology

Babylonian religion is the religious practice of Babylonia. Babylonian mythology was greatly influenced by their Sumerian counterparts and was written on clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script derived from Sumerian cuneiform. The myth ...

and the ''Ars Goetia

''The Lesser Key of Solomon'', also known as ''Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis'' or simply ''Lemegeton'', is an anonymous grimoire on demonology. It was compiled in the mid-17th century, mostly from materials a couple of centuries older.''Lemegeto ...

''—one of the five books that make up ''The'' ''Lesser Key of Solomon''—concerning the summoning of demons. '' The Azoëtia'' of Andrew D. Chumbley

Andrew D. Chumbley (15 September 1967 – 15 September 2004) was an English practitioner and theorist of magic, and a writer, poet and artist. He was Magister of the UK-based magical group Cultus Sabbati.

Career

Chumbley published several limited ...

has been described by Gavin Semple as a modern grimoire.Semple, Gavin (1994) 'The Azoëtia – reviewed by Gavin Semple', ''Starfire'' Vol. I, No. 2, 1994, p. 194.

The neopagan

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Afric ...

religion of Wicca

Wicca () is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and was ...

publicly appeared in the 1940s, and Gerald Gardner

Gerald Brosseau Gardner (13 June 1884 – 12 February 1964), also known by the craft name Scire, was an English Wiccan, as well as an author and an amateur anthropologist and archaeologist. He was instrumental in bringing the Contemporary Pag ...

introduced the ''Book of Shadows

A Book of Shadows is a book containing religious text and instructions for magical rituals found within the Neopagan religion of Wicca. Since its conception in the 1970s, it has made its way into many pagan practices and paths. The most famous ...

'' as a Wiccan grimoire.

The term grimoire commonly serves as an alternative name for a spell book or tome of magical knowledge in fantasy fiction

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy literature and drama. ...

and role-playing games

A role-playing game (sometimes spelled roleplaying game, RPG) is a game in which players assume the roles of characters in a fictional setting. Players take responsibility for acting out these roles within a narrative, either through literal ac ...

. The most famous fictional grimoire is the ''Necronomicon

The ', also referred to as the ''Book of the Dead'', or under a purported original Arabic title of ', is a fictional grimoire (textbook of magic) appearing in stories by the horror writer H. P. Lovecraft and his followers. It was first menti ...

'', a creation of H. P. Lovecraft.

See also

*Table of magical correspondences

A table of magical correspondences is a list of magical correspondences between items belonging to different categories, such as correspondences between certain deities, heavenly bodies, plants, perfumes, precious stones, etc. Such lists were co ...

, a type of reference work used in ceremonial magic

References

Bibliography

*External links

*Internet Sacred Text Archives: Grimoires

*

Scandinavian folklore

{{Fantasy fiction Fiction about magic Magic (supernatural) Magic items Non-fiction genres Religious objects Western esotericism