Great Library Of Alexandria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great Library of Alexandria in

The Library was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world, but details about it are a mixture of history and legend. The earliest known surviving source of information on the founding of the Library of Alexandria is the

The Library was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world, but details about it are a mixture of history and legend. The earliest known surviving source of information on the founding of the Library of Alexandria is the

The Ptolemaic rulers intended the Library to be a collection of all knowledge and they worked to expand the Library's collections through an aggressive and well-funded policy of book purchasing. They dispatched royal agents with large amounts of money and ordered them to purchase and collect as many texts as they possibly could, about any subject and by any author. Older copies of texts were favored over newer ones, since it was assumed that older copies had undergone less copying and that they were therefore more likely to more closely resemble what the original author had written. This program involved trips to the book fairs of

The Ptolemaic rulers intended the Library to be a collection of all knowledge and they worked to expand the Library's collections through an aggressive and well-funded policy of book purchasing. They dispatched royal agents with large amounts of money and ordered them to purchase and collect as many texts as they possibly could, about any subject and by any author. Older copies of texts were favored over newer ones, since it was assumed that older copies had undergone less copying and that they were therefore more likely to more closely resemble what the original author had written. This program involved trips to the book fairs of

p. 606

The original texts were kept in the library, and the copies delivered to the owners. The Library particularly focused on acquiring manuscripts of the Homeric poems, which were the foundation of Greek education and revered above all other poems. The Library therefore acquired many different manuscripts of these poems, tagging each copy with a label to indicate where it had come from. In addition to collecting works from the past, the Mouseion which housed the Library also served as home to a host of international scholars, poets, philosophers, and researchers, who, according to the first-century BC Greek geographer Strabo, were provided with a large salary, free food and lodging, and exemption from taxes.Kennedy, George. ''The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: Classical Criticism,'' New York: University of Cambridge Press, 1999. They had a large, circular dining hall with a high domed ceiling in which they ate meals communally. There were also numerous classrooms, where the scholars were expected to at least occasionally teach students. Ptolemy II Philadelphus is said to have had a keen interest in zoology, so it has been speculated that the Mouseion may have even had a zoo for exotic animals. According to classical scholar Lionel Casson, the idea was that if the scholars were completely freed from all the burdens of everyday life they would be able to devote more time to research and intellectual pursuits. Strabo called the group of scholars who lived at the Mouseion a σύνοδος (, "community"). As early as 283 BC, they may have numbered between thirty and fifty learned men.

After Zenodotus either died or retired, Ptolemy II Philadelphus appointed

After Zenodotus either died or retired, Ptolemy II Philadelphus appointed

p. 607

/ref> Ptolemy III had expensive copies of the plays made on the highest quality papyrus and sent the Athenians the copies, keeping the original manuscripts for the library and telling the Athenians they could keep the talents. This story may also be construed erroneously to show the power of Alexandria over Athens during the Ptolemaic dynasty. This detail arises from the fact that Alexandria was a man-made bidirectional port between the mainland and the

Aristophanes of Byzantium (lived 257– 180 BC) became the fourth head librarian sometime around 200 BC. According to a legend recorded by the Roman writer

Aristophanes of Byzantium (lived 257– 180 BC) became the fourth head librarian sometime around 200 BC. According to a legend recorded by the Roman writer

In 48 BC, during

In 48 BC, during

book 7 chapter 17

This fire purportedly spread to the parts of the city nearest to the docks, causing considerable devastation. The first-century AD Roman playwright and Stoic philosopher

49.6

The Roman historian

Very little is known about the Library of Alexandria during the time of the Roman

Very little is known about the Library of Alexandria during the time of the Roman

The '' Suda'', a tenth-century

The '' Suda'', a tenth-century

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muse

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the ...

s, the nine goddesses of the arts.Murray, S. A., (2009). The library: An illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, p.17 The idea of a universal library in Alexandria may have been proposed by Demetrius of Phalerum

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; grc-gre, Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophra ...

, an exiled Athenian statesman living in Alexandria, to Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedon ...

, who may have established plans for the Library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

, but the Library itself was probably not built until the reign of his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The Library quickly acquired many papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

scrolls, owing largely to the Ptolemaic kings' aggressive and well-funded policies for procuring texts. It is unknown precisely how many such scrolls were housed at any given time, but estimates range from 40,000 to 400,000 at its height.

Alexandria came to be regarded as the capital of knowledge and learning, in part because of the Great Library. Many important and influential scholars worked at the Library during the third and second centuries BC, including, among many others: Zenodotus of Ephesus, who worked towards standardizing the texts of the Homeric poems; Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variet ...

, who wrote the '' Pinakes'', sometimes considered to be the world's first library catalogue; Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and t ...

, who composed the epic poem the ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jas ...

''; Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who calculated the circumference of the earth within a few hundred kilometers of accuracy; Aristophanes of Byzantium, who invented the system of Greek diacritics

Greek orthography has used a variety of diacritics starting in the Hellenistic period. The more complex polytonic orthography ( el, πολυτονικό σύστημα γραφής, translit=polytonikó sýstīma grafī́s), which includes f ...

and was the first to divide poetic texts into lines; and Aristarchus of Samothrace, who produced the definitive texts of the Homeric poems as well as extensive commentaries on them. During the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, a daughter library was established in the Serapeum, a temple to the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis.

Despite the widespread modern belief that the Library of Alexandria was burned once and cataclysmically destroyed, the Library actually declined gradually over the course of several centuries. This decline began with the purging of intellectuals from Alexandria in 145 BC during the reign of Ptolemy VIII Physcon, which resulted in Aristarchus of Samothrace, the head librarian, resigning from his position and exiling himself to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

. Many other scholars, including Dionysius Thrax and Apollodorus of Athens

Apollodorus of Athens ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος, ''Apollodoros ho Athenaios''; c. 180 BC – after 120 BC) son of Asclepiades Pharmacion, Asclepiades, was a Greeks, Greek scholar, historian, and grammarian. He was a pup ...

, fled to other cities, where they continued teaching and conducting scholarship. The Library, or part of its collection, was accidentally burned by Julius Caesar during his civil war in 48 BC, but it is unclear how much was actually destroyed and it seems to have either survived or been rebuilt shortly thereafter; the geographer Strabo mentions having visited the Mouseion in around 20 BC and the prodigious scholarly output of Didymus Chalcenterus in Alexandria from this period indicates that he had access to at least some of the Library's resources.

The Library dwindled during the Roman period, from a lack of funding and support. Its membership appears to have ceased by the 260s AD. Between 270 and 275 AD, the city of Alexandria saw a Palmyrene invasion and an imperial counterattack that probably destroyed whatever remained of the Library, if it still existed at that time. The daughter library in the Serapeum may have survived after the main Library's destruction. The Serapeum was vandalized and demolished in 391 AD under a decree issued by Coptic Christian Pope Theophilus of Alexandria, but it does not seem to have housed books at the time and was mainly used as a gathering place for Neoplatonist philosophers following the teachings of Iamblichus.

Historical background

The Library of Alexandria was not the first library of its kind. A long tradition of libraries existed in both Greece and in theancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran (Ela ...

. The earliest recorded archive of written materials comes from the ancient Sumerian city-state of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.H ...

in around 3400 BC, when writing had only just begun to develop. Scholarly curation of literary texts began in around 2500 BC. The later kingdoms and empires of the ancient Near East had long traditions of book collecting. The ancient Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

and Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

ns had massive archives containing records written in many different languages. The most famous library of the ancient Near East was the Library of Ashurbanipal

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BC, including texts in va ...

in Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern b ...

, founded in the seventh century BC by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (ruled 668– 627 BC). A large library also existed in Babylon during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II ( 605– 562 BC). In Greece, the Athenian tyrant Peisistratos was said to have founded the first major public library in the sixth century BC. It was out of this mixed heritage of both Greek and Near Eastern book collections that the idea for the Library of Alexandria was born.

Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., there was a power grab for his empire among his top-ranking officers. The empire was divided into three: the Antigonids dynasty controlled Greece; the Seleucids, who had their capitals at Antioch and Seleucia, controlled large areas of Asia Minor, Syria, and Mesopotamia; and the Ptolemies controlled Egypt with Alexandria as its capital. The Macedonian kings who succeeded Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

as rulers of the Near East wanted to promote Hellenistic culture and learning throughout the known world. Historian Roy MacLeod calls this "a programme of cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism (sometimes referred to as cultural colonialism) comprises the cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" often describes practices in which a social entity engages culture (including language, traditions, ri ...

." These rulers, therefore, had a vested interest in collecting and compiling information from both the Greeks and the far more ancient kingdoms of the Near East. Libraries enhanced a city's prestige, attracted scholars, and provided practical assistance in ruling and governing the kingdom. Eventually, for these reasons, every major Hellenistic urban center would have a royal library. The Library of Alexandria, however, was unprecedented because of the scope and scale of the Ptolemies' ambitions; unlike their predecessors and contemporaries, the Ptolemies wanted to produce a repository of all knowledge. To support this endeavor, they were well positioned as Egypt was the ideal habitat for the papyrus plant, which provided a monopoly on materials needed to amass their knowledge repository.

Under Ptolemaic patronage

Founding

The Library was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world, but details about it are a mixture of history and legend. The earliest known surviving source of information on the founding of the Library of Alexandria is the

The Library was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world, but details about it are a mixture of history and legend. The earliest known surviving source of information on the founding of the Library of Alexandria is the pseudepigraphic

Pseudepigrapha (also :wikt:anglicized, anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are false attribution, falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure ...

'' Letter of Aristeas'', which was composed between 180 and 145 BC. It claims the Library was founded during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedon ...

( 323– 283 BC) and that it was initially organized by Demetrius of Phalerum

Demetrius of Phalerum (also Demetrius of Phaleron or Demetrius Phalereus; grc-gre, Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς; c. 350 – c. 280 BC) was an Athenian orator originally from Phalerum, an ancient port of Athens. A student of Theophra ...

, a student of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

who had been exiled from Athens and taken refuge in Alexandria within the Ptolemaic court. Nonetheless, the ''Letter of Aristeas'' is very late and contains information that is now known to be inaccurate. According to Diogenes Laertius, Demetrius was a student of Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

, a student of Aristotle. Other sources claim that the Library was instead created under the reign of Ptolemy I's son Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 BC).

Modern scholars agree that, while it is possible that Ptolemy I, who was a historian and author of an account of Alexander's campaign, may have laid the groundwork for the Library, it probably did not come into being as a physical institution until the reign of Ptolemy II. By that time, Demetrius of Phalerum had fallen out of favor with the Ptolemaic court. He could not, therefore, have had any role in establishing the Library as an institution. Stephen V. Tracy, however, argues that it is highly probable that Demetrius played an important role in collecting at least some of the earliest texts that would later become part of the Library's collection. In around 295 BC, Demetrius may have acquired early texts of the writings of Aristotle and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

, which he would have been uniquely positioned to do since he was a distinguished member of the Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Arist ...

.

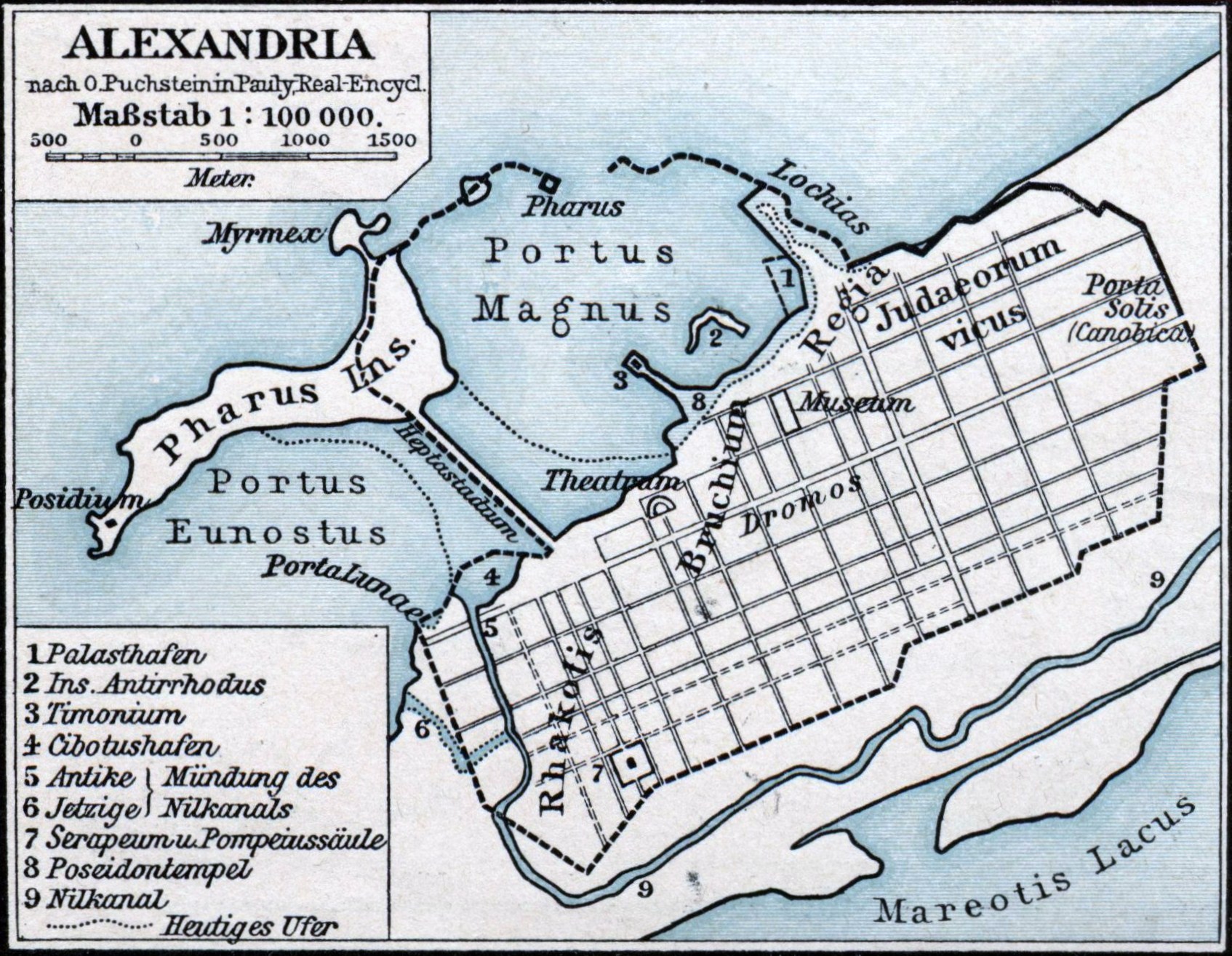

The Library was built in the Brucheion (Royal Quarter) as part of the Mouseion. Its main purpose was to show off the wealth of Egypt, with research as a lesser goal, but its contents were used to aid the ruler of Egypt. The exact layout of the library is not known, but ancient sources describe the Library of Alexandria as comprising a collection of scrolls, Greek columns, a walk, a room for shared dining, a reading room, meeting rooms, gardens, and lecture halls, creating a model for the modern university campus. A hall contained shelves for the collections of papyrus scrolls known as ''bibliothekai'' (''βιβλιοθῆκαι''). According to popular description, an inscription above the shelves read: "The place of the cure of the soul."Manguel, Alberto (2008).''The Library at Night''. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 26.

Early expansion and organization

Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

and Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

. According to the Greek medical writer Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

, under the decree of Ptolemy II, any books found on ships that came into port were taken to the library, where they were copied by official scribes.Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

, xvii.ap. 606

The original texts were kept in the library, and the copies delivered to the owners. The Library particularly focused on acquiring manuscripts of the Homeric poems, which were the foundation of Greek education and revered above all other poems. The Library therefore acquired many different manuscripts of these poems, tagging each copy with a label to indicate where it had come from. In addition to collecting works from the past, the Mouseion which housed the Library also served as home to a host of international scholars, poets, philosophers, and researchers, who, according to the first-century BC Greek geographer Strabo, were provided with a large salary, free food and lodging, and exemption from taxes.Kennedy, George. ''The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: Classical Criticism,'' New York: University of Cambridge Press, 1999. They had a large, circular dining hall with a high domed ceiling in which they ate meals communally. There were also numerous classrooms, where the scholars were expected to at least occasionally teach students. Ptolemy II Philadelphus is said to have had a keen interest in zoology, so it has been speculated that the Mouseion may have even had a zoo for exotic animals. According to classical scholar Lionel Casson, the idea was that if the scholars were completely freed from all the burdens of everyday life they would be able to devote more time to research and intellectual pursuits. Strabo called the group of scholars who lived at the Mouseion a σύνοδος (, "community"). As early as 283 BC, they may have numbered between thirty and fifty learned men.

Early scholarship

The Library of Alexandria was not affiliated with any particular philosophical school; consequently, scholars who studied there had considerable academic freedom. They were, however, subject to the authority of the king. One likely apocryphal story is told of a poet named Sotades who wrote an obscene epigram making fun of Ptolemy II for marrying his sister Arsinoe II. Ptolemy II is said to have jailed him and, after he escaped, sealed him in a lead jar and dropped him into the sea. As a religious center, the Mouseion was directed by a priest of the Muses known as an ''epistates'', who was appointed by the king in the same manner as the priests who managed the various Egyptian temples. The Library itself was directed by a scholar who served as head librarian, as well as tutor to the king's son. The first recorded head librarian was Zenodotus of Ephesus (lived 325– 270 BC). Zenodotus' main work was devoted to the establishment of canonical texts for the Homeric poems and the early Greek lyric poets. Most of what is known about him comes from later commentaries that mention his preferred readings of particular passages. Zenodotus is known to have written a glossary of rare and unusual words, which was organized in alphabetical order, making him the first person known to have employed alphabetical order as a method of organization. Since the collection at the Library of Alexandria seems to have been organized in alphabetical order by the first letter of the author's name from very early, Casson concludes that it is highly probable that Zenodotus was the one who organized it in this way. Zenodotus' system of alphabetization, however, only used the first letter of the word and it was not until the second century AD that anyone is known to have applied the same method of alphabetization to the remaining letters of the word. Meanwhile, the scholar and poetCallimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variet ...

compiled the '' Pinakes'', a 120-book catalogue of various authors and all their known works. The ''Pinakes'' has not survived, but enough references to it and fragments of it have survived to allow scholars to reconstruct its basic structure. The ''Pinakes'' was divided into multiple sections, each containing entries for writers of a particular genre of literature. The most basic division was between writers of poetry and prose, with each section divided into smaller subsections. Each section listed authors in alphabetical order. Each entry included the author's name, father's name, place of birth, and other brief biographical information, sometimes including nicknames by which that author was known, followed by a complete list of all that author's known works. The entries for prolific authors such as Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

, Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

, Sophocles, and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

must have been extremely long, spanning multiple columns of text. Although Callimachus did his most famous work at the Library of Alexandria, he never held the position of head librarian there. Callimachus' pupil Hermippus of Smyrna wrote biographies, Philostephanus of Cyrene

Philostephanus of Cyrene (Philostephanus Cyrenaeus) ( grc, Φιλοστέφανος) was a Hellenistic writer from North Africa, who was a pupil of the poet Callimachus in Alexandria and doubtless worked there during the 3rd century BC.

His histo ...

studied geography, and Istros (who may have also been from Cyrene) studied Attic antiquities. In addition to the Great Library, many other smaller libraries also began to spring up all around the city of Alexandria.

After Zenodotus either died or retired, Ptolemy II Philadelphus appointed

After Zenodotus either died or retired, Ptolemy II Philadelphus appointed Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and t ...

(lived 295– 215 BC), a native of Alexandria and a student of Callimachus, as the second head librarian of the Library of Alexandria. Philadelphus also appointed Apollonius of Rhodes as the tutor to his son, the future Ptolemy III Euergetes. Apollonius of Rhodes is best known as the author of the ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jas ...

'', an epic poem about the voyages of Jason

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek mythology, mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was marri ...

and the Argonauts

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo ...

, which has survived to the present in its complete form. The ''Argonautica'' displays Apollonius' vast knowledge of history and literature and makes allusions to a vast array of events and texts while simultaneously imitating the style of the Homeric poems. Some fragments of his scholarly writings have also survived, but he is generally more famous today as a poet than as a scholar.

According to legend, during the librarianship of Apollonius, the mathematician and inventor Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scienti ...

(lived 287 – 212 BC) came to visit the Library of Alexandria. During his time in Egypt, Archimedes is said to have observed the rise and fall of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

, leading him to invent the Archimedes' screw, which can be used to transport water from low-lying bodies into irrigation ditches. Archimedes later returned to Syracuse, where he continued making new inventions.

According to two late and largely unreliable biographies, Apollonius was forced to resign from his position as head librarian and moved to the island of Rhodes (after which he takes his name) on account of the hostile reception he received in Alexandria to the first draft of his ''Argonautica''. It is more likely that Apollonius' resignation was on account of Ptolemy III Euergetes' ascension to the throne in 246 BC.

Later scholarship and expansion

The third head librarian, Eratosthenes of Cyrene (lived 280– 194 BC), is best known today for his scientific works, but he was also a literary scholar. Eratosthenes' most important work was his treatise ''Geographika'', which was originally in three volumes. The work itself has not survived, but many fragments of it are preserved through quotation in the writings of the later geographer Strabo. Eratosthenes was the first scholar to apply mathematics to geography and map-making and, in his treatise ''Concerning the Measurement of the Earth'', he calculated the circumference of the earth and was only off by less than a few hundred kilometers. Eratosthenes also produced a map of the entire known world, which incorporated information taken from sources held in the Library, including accounts of Alexander the Great's campaigns in India and reports written by members of Ptolemaic elephant-hunting expeditions along the coast ofEast Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the histori ...

.

Eratosthenes was the first person to advance geography towards becoming a scientific discipline. Eratosthenes believed that the setting of the Homeric poems was purely imaginary and argued that the purpose of poetry was "to capture the soul", rather than to give a historically accurate account of actual events. Strabo quotes him as having sarcastically commented, "a man might find the places of Odysseus' wanderings if the day were to come when he would find the leatherworker who stitched the goatskin of the winds." Meanwhile, other scholars at the Library of Alexandria also displayed interest in scientific subjects. Bacchius of Tanagra, a contemporary of Eratosthenes, edited and commented on the medical writings of the Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Text corpus ...

. The doctors Herophilus (lived 335– 280 BC) and Erasistratus ( 304– 250 BC) studied human anatomy, but their studies were hindered by protests against the dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause ...

of human corpses, which was seen as immoral.

According to Galen, around this time, Ptolemy III requested permission from the Athenians to borrow the original manuscripts of Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

, Sophocles, and Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

, for which the Athenians demanded the enormous amount of fifteen talents () of a precious metal as guarantee that he would return them.Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

, xvii.ap. 607

/ref> Ptolemy III had expensive copies of the plays made on the highest quality papyrus and sent the Athenians the copies, keeping the original manuscripts for the library and telling the Athenians they could keep the talents. This story may also be construed erroneously to show the power of Alexandria over Athens during the Ptolemaic dynasty. This detail arises from the fact that Alexandria was a man-made bidirectional port between the mainland and the

Pharos

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria (; Ancient Greek: ὁ Φάρος τῆς Ἀλεξανδρείας, contemporary Koine ), was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, during the re ...

island, welcoming trade from the East and West, and soon found itself to be an international hub for trade, the leading producer of papyrus and, soon enough, books. As the Library expanded, it ran out of space to house the scrolls in its collection, so, during the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, it opened a satellite collection in the Serapeum of Alexandria, a temple to the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis located near the royal palace.

Peak of literary criticism

Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

, Aristophanes was one of seven judges appointed for a poetry competition hosted by Ptolemy III Euergetes. All six of the other judges favored one competitor, but Aristophanes favored the one whom the audience had liked the least. Aristophanes declared that all of the poets except for the one he had chosen had committed plagiarism and were therefore disqualified. The king demanded that he prove this, so he retrieved the texts that the authors had plagiarized from the Library, locating them by memory. On account of his impressive memory and diligence, Ptolemy III appointed him as head librarian.

The librarianship of Aristophanes of Byzantium is widely considered to have opened a more mature phase of the Library of Alexandria's history. During this phase of the Library's history, literary criticism reached its peak and came to dominate the Library's scholarly output. Aristophanes of Byzantium edited poetic texts and introduced the division of poems into separate lines on the page, since they had previously been written out just like prose. He also invented the system of Greek diacritics

Greek orthography has used a variety of diacritics starting in the Hellenistic period. The more complex polytonic orthography ( el, πολυτονικό σύστημα γραφής, translit=polytonikó sýstīma grafī́s), which includes f ...

, wrote important works on lexicography

Lexicography is the study of lexicons, and is divided into two separate academic disciplines. It is the art of compiling dictionaries.

* Practical lexicography is the art or craft of compiling, writing and editing dictionaries.

* Theoret ...

, and introduced a series of signs for textual criticism. He wrote introductions to many plays, some of which have survived in partially rewritten forms.

The fifth head librarian was an obscure individual named Apollonius, who is known by the epithet grc-gre, ὁ εἰδογράφος ("the classifier of forms"). One late lexicographical source explains this epithet as referring to the classification of poetry on the basis of musical forms.

During the early second century BC, several scholars at the Library of Alexandria studied works on medicine. Zeuxis the Empiricist is credited with having written commentaries on the Hippocratic Corpus and he actively worked to procure medical writings for the Library's collection. A scholar named Ptolemy Epithetes wrote a treatise on wounds in the Homeric poems, a subject straddling the line between traditional philology and medicine. However, it was also during the early second century BC that the political power of Ptolemaic Egypt began to decline. After the Battle of Raphia in 217 BC, Ptolemaic power became increasingly unstable. There were uprisings among segments of the Egyptian population and, in the first half of the second century BC, connection with Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend wikt:downriver, upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south. ...

became largely disrupted. Ptolemaic rulers also began to emphasize the Egyptian aspect of their nation over the Greek aspect. Consequently, many Greek scholars began to leave Alexandria for safer countries with more generous patronages.

Aristarchus of Samothrace (lived 216– 145 BC) was the sixth head librarian. He earned a reputation as the greatest of all ancient scholars and produced not only texts of classic poems and works of prose, but full '' hypomnemata'', or long, free-standing commentaries, on them. These commentaries would typically cite a passage of a classical text, explain its meaning, define any unusual words used in it, and comment on whether the words in the passage were really those used by the original author or if they were later interpolations added by scribes. He made many contributions to a variety of studies, but particularly the study of the Homeric poems, and his editorial opinions are widely quoted by ancient authors as authoritative. A portion of one of Aristarchus' commentaries on the ''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

'' of Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known for ...

has survived in a papyrus fragment. In 145 BC, however, Aristarchus became caught up in a dynastic struggle in which he supported Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator as the ruler of Egypt. Ptolemy VII was murdered and succeeded by Ptolemy VIII Physcon, who immediately set about punishing all those who had supported his predecessor, forcing Aristarchus to flee Egypt and take refuge on the island of Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, where he died shortly thereafter. Ptolemy VIII expelled all foreign scholars from Alexandria, forcing them to disperse across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Decline

After Ptolemy VIII's expulsions

Ptolemy VIII Physcon's expulsion of the scholars from Alexandria brought about a shift in the history of Hellenistic scholarship. The scholars who had studied at the Library of Alexandria and their students continued to conduct research and write treatises, but most of them no longer did so in association with the Library. Adiaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews afte ...

of Alexandrian scholarship occurred, in which scholars dispersed first throughout the eastern Mediterranean and later throughout the western Mediterranean as well. Aristarchus' student Dionysius Thrax ( 170– 90 BC) established a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax wrote the first book on Greek grammar, a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively. This book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century AD. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it, and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today. Another one of Aristarchus' pupils, Apollodorus of Athens

Apollodorus of Athens ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος, ''Apollodoros ho Athenaios''; c. 180 BC – after 120 BC) son of Asclepiades Pharmacion, Asclepiades, was a Greeks, Greek scholar, historian, and grammarian. He was a pup ...

( 180– 110 BC), went to Alexandria's greatest rival, Pergamum, where he taught and conducted research. This diaspora prompted the historian Menecles of Barce to sarcastically comment that Alexandria had become the teacher of all Greeks and barbarians alike.

Meanwhile, in Alexandria, from the middle of the second century BC onwards, Ptolemaic rule in Egypt grew less stable than it had been previously. Confronted with growing social unrest and other major political and economic problems, the later Ptolemies did not devote as much attention towards the Library and the Mouseion as their predecessors had. The status of both the Library and the head librarian diminished. Several of the later Ptolemies used the position of head librarian as a mere political plum to reward their most devoted supporters. Ptolemy VIII appointed a man named Cydas, one of his palace guards, as head librarian and Ptolemy IX Soter II

Ptolemy IX Soter II Ptolemy IX also took the same title 'Soter' as Ptolemy I. In older references and in more recent references by the German historian Huss, Ptolemy IX may be numbered VIII. ( el, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτ� ...

(ruled 88–81 BC) is said to have given the position to a political supporter. Eventually, the position of head librarian lost so much of its former prestige that even contemporary authors ceased to take interest in recording the terms of office for individual head librarians.

A shift in Greek scholarship at large occurred around the beginning of the first century BC. By this time, all major classical poetic texts had finally been standardized and extensive commentaries had already been produced on the writings of all the major literary authors of the Greek Classical Era. Consequently, there was little original work left for scholars to do with these texts. Many scholars began producing syntheses and reworkings of the commentaries of the Alexandrian scholars of previous centuries, at the expense of their own originalities. Other scholars branched out and began writing commentaries on the poetic works of postclassical authors, including Alexandrian poets such as Callimachus and Apollonius of Rhodes. Meanwhile, Alexandrian scholarship was probably introduced to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in the first century BC by Tyrannion of Amisus ( 100– 25 BC), a student of Dionysius Thrax.

Burning by Julius Caesar

In 48 BC, during

In 48 BC, during Caesar's Civil War

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was one of the last politico-military conflicts of the Roman Republic before its reorganization into the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations between Gaius Julius Caesar ...

, Julius Caesar was besieged at Alexandria. His soldiers set fire to some of the Egyptian ships docked in the Alexandrian port while trying to clear the wharves to block the fleet belonging to Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler. ...

's brother Ptolemy XIV.Aulus Gellius. Attic Nightbook 7 chapter 17

This fire purportedly spread to the parts of the city nearest to the docks, causing considerable devastation. The first-century AD Roman playwright and Stoic philosopher

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was ...

quotes Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

's '' Ab Urbe Condita Libri'', which was written between 63 and 14 BC, as saying that the fire started by Caesar destroyed 40,000 scrolls from the Library of Alexandria. The Greek Middle Platonist

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplaton ...

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

( 46–120 AD) writes in his ''Life of Caesar'' that, " en the enemy endeavored to cut off his communication by sea, he was forced to divert that danger by setting fire to his own ships, which, after burning the docks, thence spread on and destroyed the great library."Plutarch, ''Life of Caesar''49.6

The Roman historian

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

( 155 – 235 AD), however, writes: "Many places were set on fire, with the result that, along with other buildings, the dockyards and storehouses of grain and books, said to be great in number and of the finest, were burned." However, Florus and Lucan only mention that the flames burned the fleet itself and some "houses near the sea".

Scholars have interpreted Cassius Dio's wording to indicate that the fire did not actually destroy the entire Library itself, but rather only a warehouse located near the docks being used by the Library to house scrolls. Whatever devastation Caesar's fire may have caused, the Library was evidently not completely destroyed. The geographer Strabo ( 63 BC– 24 AD) mentions visiting the Mouseion, the larger research institution to which the Library was attached, in around 20 BC, several decades after Caesar's fire, indicating that it either survived the fire or was rebuilt soon afterwards. Nonetheless, Strabo's manner of talking about the Mouseion shows that it was nowhere near as prestigious as it had been a few centuries prior. Despite mentioning the Mouseion, Strabo does not mention the Library separately, perhaps indicating that it had been so drastically reduced in stature and significance that Strabo felt it did not warrant separate mention. It is unclear what happened to the Mouseion after Strabo's mention of it.

Furthermore, Plutarch records in his ''Life of Marc Antony'' that, in the years leading up to the Battle of Actium in 33 BC, Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the ...

was rumored to have given Cleopatra all 200,000 scrolls in the Library of Pergamum. Plutarch himself notes that his source for this anecdote was sometimes unreliable and it is possible that the story may be nothing more than propaganda intended to show that Mark Antony was loyal to Cleopatra and Egypt rather than to Rome. Casson, however, argues that, even if the story was made up, it would not have been believable unless the Library still existed. Edward J. Watts argues that Mark Antony's gift may have been intended to replenish the Library's collection after the damage to it caused by Caesar's fire roughly a decade and a half prior.

Further evidence for the Library's survival after 48 BC comes from the fact that the most notable producer of composite commentaries during the late first century BC and early first century AD was a scholar who worked in Alexandria named Didymus Chalcenterus, whose epithet () means "bronze guts". Didymus is said to have produced somewhere between 3,500 and 4,000 books, making him the most prolific known writer in all of antiquity. He was also given the nickname (), meaning "book-forgetter" because it was said that even he could not remember all the books he had written. Parts of some of Didymus' commentaries have been preserved in the forms of later extracts and these remains are modern scholars' most important sources of information about the critical works of the earlier scholars at the Library of Alexandria. Lionel Casson states that Didymus' prodigious output "would have been impossible without at least a good part of the resources of the library at his disposal."

Roman Period and destruction

Very little is known about the Library of Alexandria during the time of the Roman

Very little is known about the Library of Alexandria during the time of the Roman Principate

The Principate is the name sometimes given to the first period of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the so-called Dominate ...

(27 BC – 284 AD). The emperor Claudius (ruled 41–54 AD) is recorded to have built an addition onto the Library, but it seems that the Library of Alexandria's general fortunes followed those of the city of Alexandria itself. After Alexandria came under Roman rule, the city's status and, consequently that of its famous Library, gradually diminished. While the Mouseion still existed, membership was granted not on the basis of scholarly achievement, but rather on the basis of distinction in government, the military, or even in athletics.

The same was evidently the case even for the position of head librarian; the only known head librarian from the Roman Period was a man named Tiberius Claudius Balbilus, who lived in the middle of the first century AD and was a politician, administrator, and military officer with no record of substantial scholarly achievements. Members of the Mouseion were no longer required to teach, conduct research, or even live in Alexandria. The Greek writer Philostratus

Philostratus or Lucius Flavius Philostratus (; grc-gre, Φιλόστρατος ; c. 170 – 247/250 AD), called "the Athenian", was a Greek sophist of the Roman imperial period. His father was a minor sophist of the same name. He was born prob ...

records that the emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispan ...

(ruled 117–138 AD) appointed the ethnographer Dionysius of Miletus and the sophist Polemon of Laodicea

Marcus Antonius Polemon ( el, Μάρκος Ἀντώνιος Πολέμων; c. 90 – 144 AD) or Antonius Polemon, also known as Polemon of Smyrna or Polemon of Laodicea ( el, Πολέμων ὁ Λαοδικεύς), was a sophist who lived in the ...

as members of the Mouseion, even though neither of these men is known to have ever spent any significant amount of time in Alexandria.

Meanwhile, as the reputation of Alexandrian scholarship declined, the reputations of other libraries across the Mediterranean world improved, diminishing the Library of Alexandria's former status as the most prominent. Other libraries also sprang up within the city of Alexandria itself and the scrolls from the Great Library may have been used to stock some of these smaller libraries. The Caesareum and the Claudianum in Alexandria are both known to have had major libraries by the end of the first century AD. The Serapeum, originally the "daughter library" of the Great Library, probably expanded during this period as well, according to classical historian Edward J. Watts.

By the second century AD, the Roman Empire grew less dependent on grain from Alexandria and the city's prominence declined further. The Romans during this period also had less interest in Alexandrian scholarship, causing the Library's reputation to continue to decline as well. The scholars who worked and studied at the Library of Alexandria during the time of the Roman Empire were less well known than the ones who had studied there during the Ptolemaic Period. Eventually, the word "Alexandrian" itself came to be synonymous with the editing of texts, correction of textual errors, and writing of commentaries synthesized from those of earlier scholars—in other words, taking on connotations of pedantry, monotony, and lack of originality. Mention of both the Great Library of Alexandria and the Mouseion that housed it disappear after the middle of the third century AD. The last known references to scholars being members of the Mouseion date to the 260s.

In 272 AD, the emperor Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited ...

fought to recapture the city of Alexandria from the forces of the Palmyrene queen Zenobia. During the course of the fighting, Aurelian's forces destroyed the Broucheion quarter of the city in which the main library was located. If the Mouseion and Library still existed at this time, they were almost certainly destroyed during the attack as well. If they did survive the attack, then whatever was left of them would have been destroyed during the emperor Diocletian's siege of Alexandria in 297.

Arabic sources on Muslim invasion

In 642 AD, Alexandria was captured by the Muslim army of Amr ibn al-As. Several later Arabic sources describe the library's destruction by the order of Caliph Omar.Bar-Hebraeus

Gregory Bar Hebraeus ( syc, ܓܪܝܓܘܪܝܘܣ ܒܪ ܥܒܪܝܐ, b. 1226 - d. 30 July 1286), known by his Syriac ancestral surname as Bar Ebraya or Bar Ebroyo, and also by a Latinized name Abulpharagius, was an Aramean Maphrian (regional prim ...

, writing in the thirteenth century, quotes Omar as saying to Yaḥyā al-Naḥwī: "If those books are in agreement with the Quran, we have no need of them; and if these are opposed to the Quran, destroy them." Later scholars—beginning with Father Eusèbe Renaudot's remark in 1713 in his translation of the ''History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria

The ''History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria'' is a major historical work of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. It is written in Arabic, but draws extensively on Greek and Coptic sources.

The compilation was based on earlier biographical ...

'' that the tale "had something untrustworthy about it"—are skeptical of these stories, given the range of time that had passed before they were written down and the political motivations of the various writers. According to Diana Delia, "Omar's rejection of pagan and Christian wisdom may have been devised and exploited by conservative authorities as a moral exemplum for Muslims to follow in later, uncertain times, when the devotion of the faithful was once again tested by proximity to nonbelievers".

Successors to the Mouseion

Serapeum

The Serapeum is often called the "daughter library" of Alexandria. For much of the late fourth century AD it was probably the largest collection of books in the city of Alexandria. In the 370s and 380s, the Serapeum was still a major pilgrimage site for pagans. It remained a fully functioning temple, and had classrooms for philosophers to teach in. It naturally tended to attract followers of IamblicheanNeoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonism, Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and Hellenistic religion, religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of ...

. Most of these philosophers were primarily interested in theurgy, the study of cultic rituals and esoteric religious practices. The Neoplatonist philosopher Damascius

Damascius (; grc-gre, Δαμάσκιος, 458 – after 538), known as "the last of the Athenian Neoplatonists," was the last scholarch of the neoplatonic Athenian school. He was one of the neoplatonic philosophers who left Athens after law ...

(lived 458–after 538) records that a man named Olympus came from Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian language, Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from th ...

to teach at the Serapeum, where he enthusiastically taught his students the rules of traditional divine worship and ancient religious practices. He enjoined his students to worship the old gods in traditional ways, and he may have even taught them theurgy.

Scattered references indicate that, sometime in the fourth century, an institution known as the "Mouseion" may have been reestablished at a different location somewhere in Alexandria. Nothing, however, is known about the characteristics of this organization. It may have possessed some bibliographic resources, but whatever they may have been, they were clearly not comparable to those of its predecessor.

Under the Christian rule of Roman emperor Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

, pagans were persecuted, pagan rituals were outlawed, and pagan temples were destroyed. In 391 AD, the bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, ordered the destruction of the Serapeum and its conversion into a church. During the destruction a group of Christian workmen uncovered the remains of an old Mithraeum. They gave some of the cult objects to Theophilus, who had them paraded through the streets so that they could be mocked and ridiculed. The pagans of Alexandria were incensed by this act of desecration, especially the teachers of Neoplatonic philosophy and theurgy at the Serapeum. The teachers at the Serapeum took up arms and led their students and other followers in a guerrilla attack on the Christian population of Alexandria, killing many of them before being forced to retreat. In retaliation, the Christians vandalized and demolished the Serapeum, although some parts of the colonnade were still standing as late as the twelfth century. However, none of the accounts of the Serapeum's destruction mention anything about it containing a library, and sources written before its destruction speak of its collection of books in the past tense, indicating that it probably did not have any significant collection of scrolls in it at the time of its destruction.

School of Theon and Hypatia

The '' Suda'', a tenth-century

The '' Suda'', a tenth-century Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

encyclopedia, calls the mathematician Theon of Alexandria ( AD 335– 405) a "man of the Mouseion". According to classical historian Edward J. Watts, however, Theon was probably the head of a school called the "Mouseion", which was named in emulation of the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

Mouseion that had once included the Library of Alexandria, but which had little other connection to it. Theon's school was exclusive, highly prestigious, and doctrinally conservative. Theon does not seem to have had any connections to the militant Iamblichean Neoplatonists who taught in the Serapeum. Instead, he seems to have rejected the teachings of Iamblichus and may have taken pride in teaching a pure, Plotinian Neoplatonism. In around 400 AD, Theon's daughter Hypatia (born c. 350–370; died 415 AD) succeeded him as the head of his school. Like her father, she rejected the teachings of Iamblichus and instead embraced the original Neoplatonism formulated by Plotinus.

Theophilus, the bishop involved in the destruction of the Serapeum, tolerated Hypatia's school and even encouraged two of her students to become bishops in territory under his authority. Hypatia was extremely popular with the people of Alexandria and exerted profound political influence. Theophilus respected Alexandria's political structures and raised no objection to the close ties Hypatia established with Roman prefects. Hypatia was later implicated in a political feud between Orestes, the Roman prefect of Alexandria, and Cyril of Alexandria, Theophilus' successor as bishop. Rumors spread accusing her of preventing Orestes from reconciling with Cyril and, in March of 415 AD, she was murdered by a mob of Christians, led by a lector named Peter. She had no successor and her school collapsed after her death.

Later schools and libraries in Alexandria

Nonetheless, Hypatia was not the last pagan in Alexandria, nor was she the last Neoplatonist philosopher. Neoplatonism and paganism both survived in Alexandria and throughout the eastern Mediterranean for centuries after her death. British Egyptologist Charlotte Booth notes that many new academic lecture halls were built in Alexandria at Kom el-Dikka shortly after Hypatia's death, indicating that philosophy was clearly still taught in Alexandrian schools. The late fifth-century writers Zacharias Scholasticus and Aeneas of Gaza both speak of the "Mouseion" as occupying some kind of a physical space. Archaeologists have identified lecture halls dating to around this time period, located near, but not on, the site of the Ptolemaic Mouseion, which may be the "Mouseion" to which these writers refer.Collection

It is not possible to determine the collection's size in any era with certainty.Papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

scrolls constituted the collection, and although codices

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, ...

were used after 300 BC, the Alexandrian Library is never documented as having switched to parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins o ...

, perhaps because of its strong links to the papyrus trade. The Library of Alexandria in fact was indirectly causal in the creation of writing on parchment, as the Egyptians refused to export papyrus to their competitor in the Library of Pergamum. Consequently, the Library of Pergamum developed parchment as its own writing material.

A single piece of writing might occupy several scrolls, and this division into self-contained "books" was a major aspect of editorial work. King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 BC) is said to have set 500,000 scrolls as an objective for the library. The library's index, Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variet ...

' '' Pinakes'', has only survived in the form of a few fragments, and it is not possible to know with certainty how large and how diverse the collection may have been. At its height, the library was said to possess nearly half a million scrolls, and, although historians debate the precise number, the highest estimates claim 400,000 scrolls while the most conservative estimates are as low as 40,000, which is still an enormous collection that required vast storage space.

As a research institution, the library filled its stacks with new works in mathematics, astronomy, physics, natural sciences and other subjects. Its empirical standards were applied in one of the first and certainly strongest homes for serious textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts or of printed books. Such texts may range in ...

. As the same text often existed in several different versions, comparative textual criticism was crucial for ensuring their veracity. Once ascertained, canonical copies would then be made for scholars, royalty, and wealthy bibliophiles the world over, this commerce bringing income to the library.

Legacy

In antiquity

The Library of Alexandria was one of the largest and most prestigious libraries of the ancient world, but it was far from the only one. By the end of the Hellenistic Period, almost every city in the Eastern Mediterranean had a public library and so did many medium-sized towns. During the Roman Period, the number of libraries only proliferated. By the fourth century AD, there were at least two dozen public libraries in the city of Rome itself alone. In late antiquity, as the Roman Empire became Christianized, Christian libraries modeled directly on the Library of Alexandria and other great libraries of earlier pagan times began to be founded all across the Greek-speaking eastern part of the empire. Among the largest and most prominent of these libraries were the Theological Library of Caesarea Maritima, the Library of Jerusalem, and a Christian library in Alexandria. These libraries held both pagan and Christian writings side-by-side and Christian scholars applied to the Christian scriptures the same philological techniques that the scholars of the Library of Alexandria had used for analyzing the Greek classics. Nonetheless, the study of pagan authors remained secondary to the study of the Christian scriptures until theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

.

Ironically, the survival of ancient texts owes nothing to the great libraries of antiquity and instead owes everything to the fact that they were exhaustingly copied and recopied, at first by professional scribes during the Roman Period onto papyrus and later by monks during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

onto parchment. Shibli Nomani published a research work in 1892 about this library named ''Kutubkhana-i-lskandriyya

Shibli Nomani ( ur, – ; 3 June 1857 – 18 November 1914) was an Islamic scholar from the Indian subcontinent during the British Raj. He was born at Bindwal in Azamgarh district of present-day Uttar Pradesh.University of Alexandria. In May 1986, Egypt requested the Executive Board of

Jochum, Uwe. "The Alexandrian Library and Its Aftermath"

from ''Library History'' vol, pp. 5–12. * * Olesen-Bagneux, O. B. (2014). The Memory Library: How the library in Hellenistic Alexandria worked. ''Knowledge Organization, 41''(1), 3–13. * Parsons, Edward. ''The Alexandrian Library''. London, 1952

* Stille, Alexander: ''The Future of the Past'' (chapter: "The Return of the Vanished Library"). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. pp. 246–273.

* * Papyrus fragment (P.Oxy.1241)

* The BBC Radio 4 program ''In Our Time''br>discussed The Library of Alexandria 12 March 2009

The Burning of the Library of Alexandria

* Hart, David B.br>"The Perniciously Persistent Myths of Hypatia and the Great Library"

'' First Things'', 4 June 2010 * {{Authority control 3rd-century BC establishments in Egypt Ancient libraries Archaeological sites in Egypt Buildings and structures completed in the 3rd century BC Demolished buildings and structures in Egypt Education in Alexandria Former buildings and structures in Egypt Hellenistic architecture History of museums

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

to allow the international organization to conduct a feasibility study for the project. This marked the beginning of UNESCO and the international community's involvement in trying to bring the project to fruition. Starting in 1988, UNESCO and the UNDP

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)french: Programme des Nations unies pour le développement, PNUD is a United Nations agency tasked with helping countries eliminate poverty and achieve sustainable economic growth and human de ...

worked to support the international architectural competition to design the Library. Egypt devoted four hectares of land for the building of the Library and established the National High Commission for the Library of Alexandria. Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak, (; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011.

Before he entered politics, Mubarak was a career officer in ...

took a personal interest in the project, which greatly contributed to its advancement. An international architectural competition took place in 1989 with Norwegian architectural firm Snohetta winning the competition. Completed in 2002, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina now functions as a modern library and cultural center, commemorating the original Library of Alexandria. In line with the mission of the Great Library of Alexandria, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina also houses the International School of Information Science, a school for students preparing for highly specialized post-graduate degrees, whose goal is to train professional staff for libraries in Egypt and across the Middle East.

See also

* Imperial Library of ConstantinopleExplanatory notes

References

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *Jochum, Uwe. "The Alexandrian Library and Its Aftermath"

from ''Library History'' vol, pp. 5–12. * * Olesen-Bagneux, O. B. (2014). The Memory Library: How the library in Hellenistic Alexandria worked. ''Knowledge Organization, 41''(1), 3–13. * Parsons, Edward. ''The Alexandrian Library''. London, 1952

* Stille, Alexander: ''The Future of the Past'' (chapter: "The Return of the Vanished Library"). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. pp. 246–273.

External links

* James Hannam* * Papyrus fragment (P.Oxy.1241)

* The BBC Radio 4 program ''In Our Time''br>discussed The Library of Alexandria 12 March 2009

The Burning of the Library of Alexandria

* Hart, David B.br>"The Perniciously Persistent Myths of Hypatia and the Great Library"

'' First Things'', 4 June 2010 * {{Authority control 3rd-century BC establishments in Egypt Ancient libraries Archaeological sites in Egypt Buildings and structures completed in the 3rd century BC Demolished buildings and structures in Egypt Education in Alexandria Former buildings and structures in Egypt Hellenistic architecture History of museums

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

Ptolemaic Alexandria