Germans Of Jewish Ancestry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish community. The community survived under Charlemagne, but suffered during the Crusades. Accusations of well poisoning during the

Jewish migration from

Jewish migration from

The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany, especially in the Rhineland.Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. University of Pennsylvania. . pp. 50–7. The communities of Trier, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne, were attacked. The Jewish community of Speyer was saved by the bishop, but 800 were slain in Worms. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July 1096. Alleged crimes, like desecration of the host, ritual murder, poisoning of wells, and treason, brought hundreds to the stake and drove thousands into exile.

Jews were alleged to have caused the inroads of the Mongols, though they suffered equally with the Christians. Jews suffered intense persecution during the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298. In 1336 Jews from Alsace were subjected to massacres by the outlaws of

The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany, especially in the Rhineland.Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. University of Pennsylvania. . pp. 50–7. The communities of Trier, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne, were attacked. The Jewish community of Speyer was saved by the bishop, but 800 were slain in Worms. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July 1096. Alleged crimes, like desecration of the host, ritual murder, poisoning of wells, and treason, brought hundreds to the stake and drove thousands into exile.

Jews were alleged to have caused the inroads of the Mongols, though they suffered equally with the Christians. Jews suffered intense persecution during the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298. In 1336 Jews from Alsace were subjected to massacres by the outlaws of

The legal and civic status of the Jews underwent a transformation under the Holy Roman Empire. Jewish people found a certain degree of protection with the

The legal and civic status of the Jews underwent a transformation under the Holy Roman Empire. Jewish people found a certain degree of protection with the  The 15th century did not bring any amelioration. What happened in the time of the Crusades happened again. The war upon the Hussites became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The Jews of Austria,

The 15th century did not bring any amelioration. What happened in the time of the Crusades happened again. The war upon the Hussites became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The Jews of Austria,

Though reading German books was forbidden in the 1700s by Jewish inspectors who had a measure of police power in Germany, Moses Mendelson found his first German book, an edition of Protestant theology, at a well-organized system of Jewish charity for needy Talmud students. Mendelssohn read this book and found proof of the existence of God – his first meeting with a sample of European letters. This was only the beginning to Mendelssohn's inquiries about the knowledge of life. Mendelssohn learned many new languages, and with his whole education consisting of Talmud lessons, he thought in Hebrew and translated for himself every new piece of work he met into this language. The divide between the Jews and the rest of society was caused by a lack of translation between these two languages, and

Though reading German books was forbidden in the 1700s by Jewish inspectors who had a measure of police power in Germany, Moses Mendelson found his first German book, an edition of Protestant theology, at a well-organized system of Jewish charity for needy Talmud students. Mendelssohn read this book and found proof of the existence of God – his first meeting with a sample of European letters. This was only the beginning to Mendelssohn's inquiries about the knowledge of life. Mendelssohn learned many new languages, and with his whole education consisting of Talmud lessons, he thought in Hebrew and translated for himself every new piece of work he met into this language. The divide between the Jews and the rest of society was caused by a lack of translation between these two languages, and  In the late 18th century, a youthful enthusiasm for new ideals of religious equality began to take hold in the western world. Austrian Emperor Joseph II was foremost in espousing these new ideals. As early as 1782, he issued the ''Patent of Toleration for the Jews of Lower Austria'', thereby establishing civic equality for his Jewish subjects.

Before 1806, when general citizenship was largely nonexistent in the Holy Roman Empire, its inhabitants were subject to varying

In the late 18th century, a youthful enthusiasm for new ideals of religious equality began to take hold in the western world. Austrian Emperor Joseph II was foremost in espousing these new ideals. As early as 1782, he issued the ''Patent of Toleration for the Jews of Lower Austria'', thereby establishing civic equality for his Jewish subjects.

Before 1806, when general citizenship was largely nonexistent in the Holy Roman Empire, its inhabitants were subject to varying

Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim were two founders of the conservative movement in modern Judaism who accepted the modern spirit of liberalism. Samson Raphael Hirsch defended traditional customs, denying the modern "spirit". Neither of these beliefs was followed by the faithful Jews.

Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim were two founders of the conservative movement in modern Judaism who accepted the modern spirit of liberalism. Samson Raphael Hirsch defended traditional customs, denying the modern "spirit". Neither of these beliefs was followed by the faithful Jews.

Jews experienced a period of legal equality after 1848. Baden and Württemberg passed the legislation that gave the Jews complete equality before the law in 1861–64. The newly formed

Jews experienced a period of legal equality after 1848. Baden and Württemberg passed the legislation that gave the Jews complete equality before the law in 1861–64. The newly formed

A higher percentage of German Jews fought in World War I than of any other ethnic, religious or political group in Germany; around 12,000 died in the fighting.

Many German Jews supported the war out of patriotism; like many Germans, they viewed Germany's actions as defensive in nature and even

A higher percentage of German Jews fought in World War I than of any other ethnic, religious or political group in Germany; around 12,000 died in the fighting.

Many German Jews supported the war out of patriotism; like many Germans, they viewed Germany's actions as defensive in nature and even  While going to war brought the unsavoury prospect of fighting fellow Jews in Russia, France and Britain, for the majority of Jews this severing of ties with Jewish communities in the

While going to war brought the unsavoury prospect of fighting fellow Jews in Russia, France and Britain, for the majority of Jews this severing of ties with Jewish communities in the  Prominent Jewish industrialists and bankers, such as Walter Rathenau and Max Warburg played major roles in supervising the German war economy.

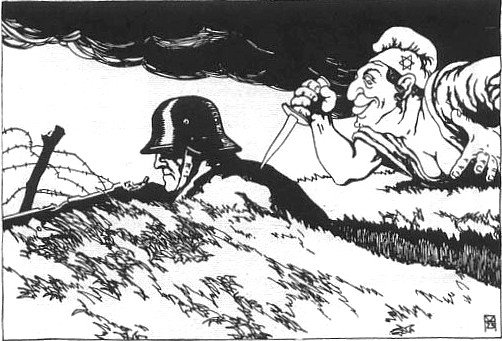

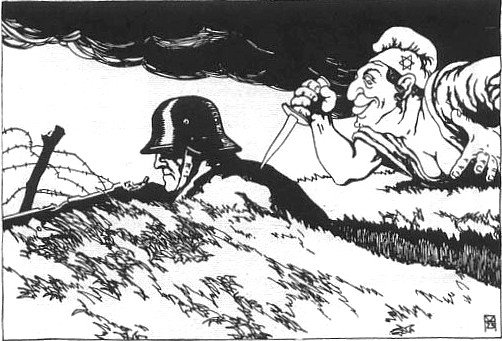

In October 1916, the German Military High Command administered the ''

Prominent Jewish industrialists and bankers, such as Walter Rathenau and Max Warburg played major roles in supervising the German war economy.

In October 1916, the German Military High Command administered the ''

There was sporadic

There was sporadic

Jewish intellectuals and creative professionals were among the leading figures in many areas of Weimar culture. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim,

Jewish intellectuals and creative professionals were among the leading figures in many areas of Weimar culture. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim,

The continuing and exacerbating abuse of Jews in Germany triggered calls throughout March 1933 by Jewish leaders around the world for a boycott of German products. The Nazis responded with further bans and boycotts against Jewish doctors, shops, lawyers and stores. Only six days later, the

The continuing and exacerbating abuse of Jews in Germany triggered calls throughout March 1933 by Jewish leaders around the world for a boycott of German products. The Nazis responded with further bans and boycotts against Jewish doctors, shops, lawyers and stores. Only six days later, the

/ref> On August 2, 1934, President Paul von Hindenburg died. No new president was appointed; with Adolf Hitler as

On August 2, 1934, President Paul von Hindenburg died. No new president was appointed; with Adolf Hitler as  On June 4, 1937, two young German Jews, Helmut Hirsch and Isaac Utting, were both executed for being involved in a plot to bomb the Nazi party headquarters in Nuremberg.

As of March 1, 1938, government contracts could no longer be awarded to Jewish businesses. On September 30, "Aryan" doctors could only treat "Aryan" patients. Provision of medical care to Jews was already hampered by the fact that Jews were banned from being doctors or having any professional jobs.

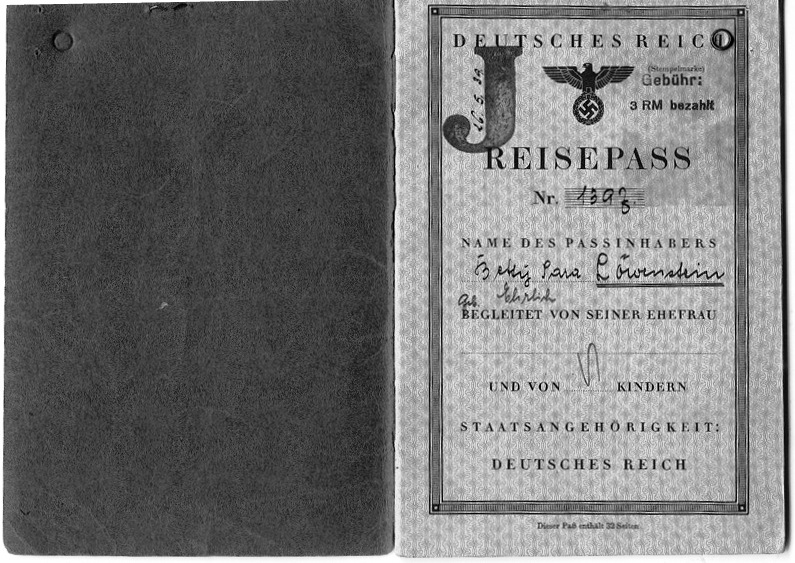

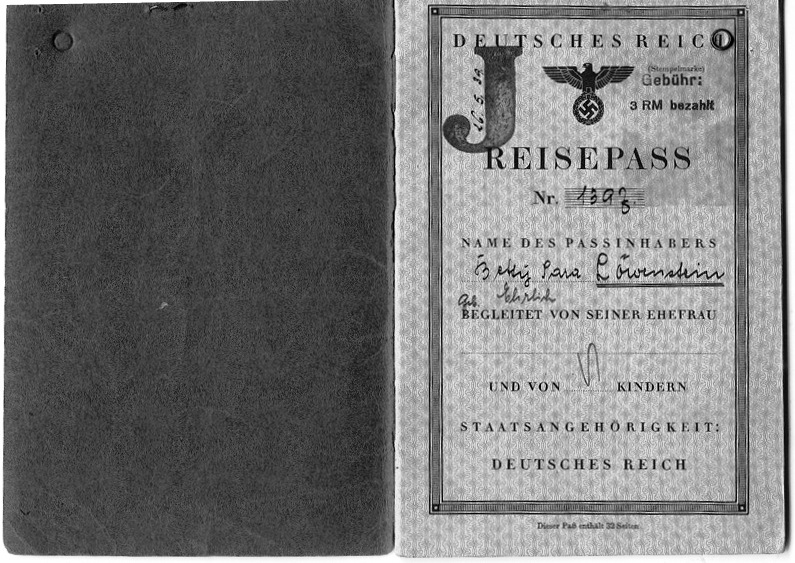

Beginning August 17, 1938, Jews with first names of non-Jewish origin had to add Israel (males) or Sarah (females) to their names, and a large J was to be imprinted on their passports beginning October 5. On November 15 Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been forced to sell out to the Nazi German government. This further reduced Jews' rights as human beings. They were in many ways officially separated from the German population.

On June 4, 1937, two young German Jews, Helmut Hirsch and Isaac Utting, were both executed for being involved in a plot to bomb the Nazi party headquarters in Nuremberg.

As of March 1, 1938, government contracts could no longer be awarded to Jewish businesses. On September 30, "Aryan" doctors could only treat "Aryan" patients. Provision of medical care to Jews was already hampered by the fact that Jews were banned from being doctors or having any professional jobs.

Beginning August 17, 1938, Jews with first names of non-Jewish origin had to add Israel (males) or Sarah (females) to their names, and a large J was to be imprinted on their passports beginning October 5. On November 15 Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been forced to sell out to the Nazi German government. This further reduced Jews' rights as human beings. They were in many ways officially separated from the German population.

The increasingly totalitarian, militaristic regime which was being imposed on Germany by Hitler allowed him to control the actions of the SS and the military. On November 7, 1938, a young Polish Jew, Herschel Grynszpan, attacked and shot two German officials in the Nazi German embassy in Paris. (Grynszpan was angry about the treatment of his parents by the Nazi Germans.) On November 9 the German Attache, Ernst vom Rath, died.

The increasingly totalitarian, militaristic regime which was being imposed on Germany by Hitler allowed him to control the actions of the SS and the military. On November 7, 1938, a young Polish Jew, Herschel Grynszpan, attacked and shot two German officials in the Nazi German embassy in Paris. (Grynszpan was angry about the treatment of his parents by the Nazi Germans.) On November 9 the German Attache, Ernst vom Rath, died.  Increasing antisemitism prompted a wave of Jewish mass emigration from Germany throughout the 1930s. Among the first wave were intellectuals, politically active individuals, and Zionists. However, as Nazi legislation worsened the Jews' situation, more Jews wished to leave Germany, with a panicked rush in the months after Kristallnacht in 1938.

Mandatory Palestine was a popular destination for German Jewish emigration. Soon after the Nazis' rise to power in 1933, they negotiated the Haavara Agreement with Zionist authorities in

Increasing antisemitism prompted a wave of Jewish mass emigration from Germany throughout the 1930s. Among the first wave were intellectuals, politically active individuals, and Zionists. However, as Nazi legislation worsened the Jews' situation, more Jews wished to leave Germany, with a panicked rush in the months after Kristallnacht in 1938.

Mandatory Palestine was a popular destination for German Jewish emigration. Soon after the Nazis' rise to power in 1933, they negotiated the Haavara Agreement with Zionist authorities in

On January 27, 2003, then German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder signed the first-ever agreement on a federal level with the Central Council, so that Judaism was granted the same elevated, semi-established legal status in Germany as the Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church in Germany, at least since the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of 1949.

In Germany it is a criminal act to deny the Holocaust or that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (§ 130 StGB); violations can be punished with up to five years of prison. In 2007, the Interior Minister of Germany, Wolfgang Schäuble, pointed out the official policy of Germany: "We will not tolerate any form of extremism, xenophobia or antisemitism." Although the number of right-wing groups and organisations grew from 141 (2001)Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

On January 27, 2003, then German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder signed the first-ever agreement on a federal level with the Central Council, so that Judaism was granted the same elevated, semi-established legal status in Germany as the Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church in Germany, at least since the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of 1949.

In Germany it is a criminal act to deny the Holocaust or that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (§ 130 StGB); violations can be punished with up to five years of prison. In 2007, the Interior Minister of Germany, Wolfgang Schäuble, pointed out the official policy of Germany: "We will not tolerate any form of extremism, xenophobia or antisemitism." Although the number of right-wing groups and organisations grew from 141 (2001)Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

Verfassungsschutzbericht 2003

. Annual Report. 2003, page 29. to 182 (2006), Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

Verfassungsschutzbericht 2006. Annual Report

. 2006, page 51. especially in the formerly communist East Germany, Germany's measures against right-wing groups and antisemitism are effective: according to the annual reports of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution the overall number of far-right extremists in Germany has dropped in recent years from 49,700 (2001), 45,000 (2002), 41,500 (2003), 40,700 (2004), 39,000 (2005), to 38,600 in 2006. Germany provided several million euros to fund "nationwide programs aimed at fighting far-right extremism, including teams of traveling consultants, and victims' groups". The Associated Press.

Berlin police say 16 arrested during neo-Nazi demonstration.

'' Taiwan News''. October 22, 2006 Despite these facts, Israeli Ambassador A flagship moment for the burgeoning Jewish community in modern Germany occurred on November 9, 2006 (the 68th anniversary of Kristallnacht), when the newly constructed Ohel Jakob synagogue was dedicated in Munich, Germany. This is particularly crucial given the fact that Munich was once at the ideological heart of Nazi Germany.

Jewish life in the capital Berlin is prospering, the Jewish community is growing, the

A flagship moment for the burgeoning Jewish community in modern Germany occurred on November 9, 2006 (the 68th anniversary of Kristallnacht), when the newly constructed Ohel Jakob synagogue was dedicated in Munich, Germany. This is particularly crucial given the fact that Munich was once at the ideological heart of Nazi Germany.

Jewish life in the capital Berlin is prospering, the Jewish community is growing, the

Jewish Virtual LibraryJewish Museum Berlin

Leo Baeck Institute, NY

a research library and archive focused on the history of German-speaking Jews

DigiBaeck

Digital collections at Leo Baeck Institute

Berkley Center: Being Jewish in the New GermanyThe Jews of Germany

The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot {{History of the Jews in Europe Middle Eastern diaspora in Germany The Holocaust in Germany

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

(1346–53) led to mass slaughter of German Jews and they fled in large numbers to Poland. The Jewish communities of the cities of Mainz, Speyer and Worms became the center of Jewish life during medieval times. "This was a golden age as area bishops protected the Jews resulting in increased trade and prosperity."

The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany. Entire communities, like those of Trier, Worms, Mainz and Cologne, were slaughtered. The Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Cat ...

became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The end of the 15th century was a period of religious hatred that ascribed to Jews all possible evils. With Napoleon's fall in 1815, growing nationalism resulted in increasing repression. From August to October 1819, pogroms that came to be known as the Hep-Hep riots took place throughout Germany. During this time, many German states stripped Jews of their civil rights. As a result, many German Jews began to emigrate.

From the time of Moses Mendelssohn until the 20th century, the community gradually achieved emancipation, and then prospered.

In January 1933, some 522,000 Jews lived in Germany. After the Nazis took power and implemented their antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

ideology and policies, the Jewish community was increasingly persecuted. About 60% (numbering around 304,000) emigrated during the first six years of the Nazi dictatorship. In 1933, persecution of the Jews became an official Nazi policy. In 1935 and 1936, the pace of antisemitic persecution increased. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them from participating in education, politics, higher education and industry. On 10 November 1938, the state police and Nazi paramilitary forces orchestrated the Night of Broken Glass ('' Kristallnacht''), in which the storefronts of Jewish shops and offices were smashed and vandalized, and many synagogues were destroyed by fire. Only roughly 214,000 Jews were left in Germany proper (1937 borders) on the eve of World War II.

Beginning in late 1941, the remaining community was subjected to systematic deportations to ghettos and ultimately, to death camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

in Eastern Europe. In May 1943, Germany was declared '' judenrein'' (clean of Jews; also ''judenfrei'': free of Jews). By the end of the war, an estimated 160,000 to 180,000 German Jews had been killed by the Nazi regime and their collaborators. A total of about six million European Jews were murdered under the direction of the Nazis, in the genocide that later came to be known as the Holocaust.

After the war, the Jewish community in Germany started to slowly grow again. Beginning around 1990, a spurt of growth was fueled by immigration from the former Soviet Union, so that at the turn of the 21st century, Germany had the only growing Jewish community in Europe, and the majority of German Jews were Russian-speaking. By 2018, the Jewish population of Germany had leveled off at 116,000, not including non-Jewish members of households; the total estimated enlarged population of Jews living in Germany, including non-Jewish household members, was close to 225,000.

Currently in Germany, denial of the Holocaust

Holocaust denial is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that falsely asserts that the Nazi genocide of Jews, known as the Holocaust, is a myth, fabrication, or exaggeration. Holocaust deniers make one or more of the following false statements:

* ...

or that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (§ 130 StGB) is a criminal act; violations can be punished with up to five years of prison. In 2006, on the occasion of the World Cup held in Germany, the then-Interior Minister of Germany

The Federal Ministry of the Interior and for Community (german: Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, ; '' Heimat'' also translates to "homeland"), abbreviated , is a cabinet-level ministry of the Federal Republic of Germany. Its mai ...

Wolfgang Schäuble, urged vigilance against far-right extremism

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

, saying: "We will not tolerate any form of extremism, xenophobia, or antisemitism." In spite of Germany's measures against these groups and antisemites, a number of incidents have occurred in recent years.

From Rome to the Crusades

Jewish migration from

Jewish migration from Roman Italy

Roman Italy (called in both the Latin and Italian languages referring to the Italian Peninsula) was the homeland of the ancient Romans and of the Roman empire. According to Roman mythology, Italy was the ancestral home promised by Jupiter to A ...

is considered the most likely source of the first Jews on German territory. While the date of the first settlement of Jews in the regions which the Romans called Germania Superior

Germania Superior ("Upper Germania") was an imperial province of the Roman Empire. It comprised an area of today's western Switzerland, the French Jura and Alsace regions, and southwestern Germany. Important cities were Besançon ('' Vesontio' ...

, Germania Inferior, and Magna Germania is not known, the first authentic document relating to a large and well-organized Jewish community in these regions dates from 321 and refers to Cologne on the Rhine (Jewish immigrants began settling in Rome itself as early as 139 BC). It indicates that the legal status of the Jews there was the same as elsewhere in the Roman Empire. They enjoyed some civil liberties, but were restricted regarding the dissemination of their culture, the keeping of non-Jewish slaves, and the holding of office under the government.

Jews were otherwise free to follow any occupation open to indigenous Germans and were engaged in agriculture, trade, industry, and gradually money-lending. These conditions at first continued in the subsequently established Germanic kingdoms under the Burgundians

The Burgundians ( la, Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; on, Burgundar; ang, Burgendas; grc-gre, Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and ...

and Franks, for ecclesiasticism took root slowly. The Merovingian rulers who succeeded to the Burgundian empire were devoid of fanaticism and gave scant support to the efforts of the Church to restrict the civic and social status of the Jews.

Charlemagne (800–814) readily made use of the Roman Catholic Church for the purpose of infusing coherence into the loosely joined parts of his extensive empire, but was not by any means a blind tool of the canonical law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

. He employed Jews for diplomatic purposes, sending, for instance, a Jew as interpreter and guide with his embassy to Harun al-Rashid. Yet, even then, a gradual change occurred in the lives of the Jews. The Church forbade Christians to be usurers

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is ch ...

, so the Jews secured the remunerative

Remuneration is the pay or other financial compensation provided in exchange for an employee's ''services performed'' (not to be confused with giving (away), or donating, or the act of providing to). A number of complementary benefits in addition ...

monopoly of money-lending. This decree caused a mixed reaction of people in general in the Carolingian Empire (including Germany) to the Jews: Jewish people were sought everywhere, as well as avoided. This ambivalence about Jews occurred because their capital was indispensable, while their business was viewed as disreputable. This curious combination of circumstances increased Jewish influence and Jews went about the country freely, settling also in the eastern portions (Old Saxony

"Old Saxony" is the original homeland of the Saxons. It corresponds roughly to the modern German states of Lower Saxony, eastern part of modern North Rhine-Westphalia state (Westphalia), Nordalbingia (Holstein, southern part of Schleswig-Holstein ...

and Duchy of Thuringia). Aside from Cologne, the earliest communities were established in Mainz, Worms, Speyer, and Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

.

The status of the German Jews remained unchanged under Charlemagne's successor, Louis the Pious. Jews were unrestricted in their commerce; however, they paid somewhat higher taxes into the state treasury than did the non-Jews. A special officer, the ''Judenmeister'', was appointed by the government to protect Jewish privileges. The later Carolingians

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

, however, followed the demands of the Church more and more. The bishops continually argued at the synods

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mea ...

for including and enforcing decrees of the canonical law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

, with the consequence that the majority Christian populace mistrusted the Jewish unbelievers. This feeling, among both princes and people, was further stimulated by the attacks on the civic equality of the Jews. Beginning with the 10th century, Holy Week became more and more a period of antisemitic activities, yet the Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

emperors did not treat the Jews badly, exacting from them merely the taxes levied upon all other merchants. Although the Jews in Germany were as ignorant as their contemporaries in secular studies, they could read and understand the Hebrew prayers

Listed below are some Hebrew language, Hebrew Jewish services, prayers and Berakhah, blessings that are part of Judaism that are recited by many Jews. Most prayers and blessings can be found in the Siddur, or prayer book. This article addresses J ...

and the Bible in the original text. Halakhic

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

studies began to flourish about 1000.

At that time, Rav

''Rav'' (or ''Rab,'' Modern Hebrew: ) is the Hebrew generic term for a person who teaches Torah; a Jewish spiritual guide; or a rabbi. For example, Pirkei Avot (1:6) states that:

The term ''rav'' is also Hebrew for ''rabbi''. (For a more nuan ...

Gershom ben Judah was teaching at Metz and Mainz, gathering about him pupils from far and near. He is described in Jewish historiography as a model of wisdom, humility, and piety, and became known to succeeding generations as the "Light of the Exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

". In highlighting his role in the religious development of Jews in the German lands, '' The Jewish Encyclopedia'' (1901–1906) draws a direct connection to the great spiritual fortitude later shown by the Jewish communities in the era of the Crusades:

He first stimulated the German Jews to study the treasures of their religious literature. This continuous study of the Torah and the Talmud produced such a devotion to Judaism that the Jews considered life without their religion not worth living; but they did not realize this clearly until the time of the Crusades, when they were often compelled to choose between life and faith.

Cultural and religious centre of European Jewry

The Jewish communities of the cities of Speyer, Worms, and Mainz formed the league of cities which became the center of Jewish life during Medieval times. These are referred to as the ShUM cities, after the first letters of the Hebrew names:Shin

Shin may refer to:

Biology

* The front part of the human leg below the knee

* Shinbone, the tibia, the larger of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates

Names

* Shin (given name) (Katakana: シン, Hiragana: しん), a Japanese ...

for Speyer (''Shpira''), Waw

Waw or WAW may refer to:

* Waw (letter), a letter in many Semitic abjads

* Waw, the velomobile

* Another spelling for the town Wau, South Sudan

* Waw Township, Burma

*Warsaw Chopin Airport, an international airport serving Warsaw, Poland (IATA ai ...

for Worms (''Varmaisa'') and Mem

Mem (also spelled Meem, Meme, or Mim) is the thirteenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Hebrew mēm , Aramaic Mem , Syriac mīm ܡ, Arabic mīm and Phoenician mēm . Its sound value is .

The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek mu ...

for Mainz (''Magentza''). The '' Takkanot Shum'' ( he, תקנות שו"ם "Enactments of ShUM") were a set of decrees formulated and agreed upon over a period of decades by their Jewish community leaders. The official website for the city of Mainz states:

Historian John Man

John Man (1512–1569) was an English churchman, college head, and a diplomat.

Life

He was born at Lacock or Winterbourne Stoke, in Wiltshire. He was educated at Winchester College from 1523, and New College, Oxford, where he graduated B.A. in ...

describes Mainz as "the capital of European Jewry

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

", noting that Gershom ben Judah "was the first to bring copies of the Talmud to Western Europe" and that his directives "helped Jews adapt to European practices." Gershom's school attracted Jews from all over Europe, including the famous biblical scholar Rashi; and "in the mid-14th century, it had the largest Jewish community in Europe: some 6,000." "In essence," states the City of Mainz web site, "this was a golden age as area bishops protected the Jews resulting in increased trade and prosperity."

A period of massacres (1096–1349)

The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany, especially in the Rhineland.Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. University of Pennsylvania. . pp. 50–7. The communities of Trier, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne, were attacked. The Jewish community of Speyer was saved by the bishop, but 800 were slain in Worms. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July 1096. Alleged crimes, like desecration of the host, ritual murder, poisoning of wells, and treason, brought hundreds to the stake and drove thousands into exile.

Jews were alleged to have caused the inroads of the Mongols, though they suffered equally with the Christians. Jews suffered intense persecution during the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298. In 1336 Jews from Alsace were subjected to massacres by the outlaws of

The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany, especially in the Rhineland.Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. University of Pennsylvania. . pp. 50–7. The communities of Trier, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne, were attacked. The Jewish community of Speyer was saved by the bishop, but 800 were slain in Worms. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July 1096. Alleged crimes, like desecration of the host, ritual murder, poisoning of wells, and treason, brought hundreds to the stake and drove thousands into exile.

Jews were alleged to have caused the inroads of the Mongols, though they suffered equally with the Christians. Jews suffered intense persecution during the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298. In 1336 Jews from Alsace were subjected to massacres by the outlaws of Arnold von Uissigheim

Arnold III von Uissigheim, also ''blessed Arnold'' und "König Armleder", (c.1298-1336) was a medieval German highwayman, bandit, and renegade knight of the Uissigheim family, of the village Uissigheim of the same name. He was the leader of the ...

.

When the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

swept over Europe in 1348–49, some Christian communities accused Jews of poisoning wells. Compared to the south and west of the Holy Roman Empire, the persecutions appear to have brought less drastic effects in the eastern parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Nonetheless, in the Erfurt Massacre of 1349, the members of the entire Jewish community were murdered or expelled from the city, due to superstitions about the Black Death. Many persecutions were clearly favoured by a royal throne crisis and the Wittelsbach- Luxembourg dualism, therefore recent German research proposed the term “Thronkrisenverfolgungen” (throne crisis persecutions).Christophersen, Jörn R. (2021). Krisen, Chancen und Bedrohungen. Harrassowitz . p. 720 (English Summary). Royal policy and public ambivalence towards Jews helped the persecuted Jews fleeing the German-speaking lands to form the foundations of what would become the largest Jewish community in Europe in what is now Poland/Ukraine/Romania/Belarus/Lithuania.

In the Holy Roman Empire

The legal and civic status of the Jews underwent a transformation under the Holy Roman Empire. Jewish people found a certain degree of protection with the

The legal and civic status of the Jews underwent a transformation under the Holy Roman Empire. Jewish people found a certain degree of protection with the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

, who claimed the right of possession and protection of all the Jews of the empire. A justification for this claim was that the Holy Roman Emperor was the successor of the emperor Titus, who was said to have acquired the Jews as his private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ...

. The German emperors apparently claimed this right of possession more for the sake of taxing the Jews than of protecting them.

A variety of such taxes existed. Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Louis IV (german: Ludwig; 1 April 1282 – 11 October 1347), called the Bavarian, of the house of Wittelsbach, was King of the Romans from 1314, King of Italy from 1327, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1328.

Louis' election as king of Germany in ...

, was a prolific creator of new taxes. In 1342, he instituted the "golden sacrificial penny" and decreed that every year all the Jews should pay the emperor one kreutzer out of every florins

The Florentine florin was a gold coin struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time. It had 54 grains (3.499 grams, 0.113 troy ounce) of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a purcha ...

of their property in addition to the taxes they were already paying to both the state and municipal authorities. The emperors of the House of Luxembourg devised other means of taxation. They turned their prerogatives in regard to the Jews to further account by selling at a high price to the princes and free towns of the empire the valuable privilege of taxing and fining the Jews. Charles IV, via the Golden Bull of 1356, granted this privilege to the seven electors of the empire when the empire was reorganized in 1356.

From this time onward, for reasons that also apparently concerned taxes, the Jews of Germany gradually passed in increasing numbers from the authority of the emperor to that of both the lesser sovereigns and the cities. For the sake of sorely needed revenue, the Jews were now invited, with the promise of full protection, to return to those districts and cities from which they had shortly before been expelled. However, as soon as Jewish people acquired some property, they were again plundered and driven away. These episodes thenceforth constituted a large portion of the medieval history of the German Jews. Emperor Wenceslaus was most expert in transferring to his own coffers gold from the pockets of rich Jews. He made compacts with many cities, estates, and princes whereby he annulled all outstanding debts to the Jews in return for a certain sum paid to him. Emperor Wenceslaus declared that anyone helping Jews with the collection of their debts, in spite of this annulment, would be dealt with as a robber and peacebreaker, and be forced to make restitution. This decree, which for years allegedly injured the public credit, is said to have impoverished thousands of Jewish families during the close of the 14th century.

The 15th century did not bring any amelioration. What happened in the time of the Crusades happened again. The war upon the Hussites became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The Jews of Austria,

The 15th century did not bring any amelioration. What happened in the time of the Crusades happened again. The war upon the Hussites became the signal for renewed persecution of Jews. The Jews of Austria, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Moravia, and Silesia passed through all the terrors of death, forced baptism

Forced conversion is the adoption of a different religion or the adoption of irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which ...

, or voluntary self-immolation for the sake of their faith. When the Hussites made peace with the Church, the Pope sent the Franciscan friar John of Capistrano to win the renegades back into the fold and inspire them with loathing for heresy and unbelief; 41 martyrs were burned in Wrocław alone, and all Jews were forever banished from Silesia. The Franciscan friar Bernardine of Feltre brought a similar fate upon the communities in southern and western Germany. As a consequence of the fictitious confessions extracted under torture from the Jews of Trent

Trent may refer to:

Places Italy

* Trento in northern Italy, site of the Council of Trent United Kingdom

* Trent, Dorset, England, United Kingdom Germany

* Trent, Germany, a municipality on the island of Rügen United States

* Trent, California, ...

, the populace of many cities, especially of Regensburg, fell upon the Jews and massacred them.

The end of the 15th century, which brought a new epoch for the Christian world, brought no relief to the Jews. Jews in Germany remained the victims of a religious hatred that ascribed to them all possible evils. When the established Church, threatened in its spiritual power in Germany and elsewhere, prepared for its conflict with the culture of the German Renaissance

The German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, was a cultural and artistic movement that spread among Germany, German thinkers in the 15th and 16th centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Many areas of the arts and ...

, one of its most convenient points of attack was rabbinic literature. At this time, as once before in France, Jewish converts spread false reports in regard to the Talmud, but an advocate of the book arose in the person of Johann Reuchlin, the German humanist, who was the first one in Germany to include the Hebrew language among the humanities. His opinion, though strongly opposed by the Dominicans and their followers, finally prevailed when the humanistic Pope Leo X permitted the Talmud to be printed in Italy.

Moses Mendelssohn

Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

translated the Torah into German, bridging the gap between the two; this book allowed Jews to speak and write in German, preparing them for participation in German culture and secular science. In 1750, Mendelssohn began to serve as a teacher in the house of Isaac Bernhard, the owner of a silk factory, after beginning his publications of philosophical essays in German. Mendelssohn conceived of God as a perfect Being and had faith in "God's wisdom, righteousness, mercy, and goodness." He argued, "the world results from a creative act through which the divine will seeks to realize the highest good," and accepted the existence of miracles and revelation as long as belief in God did not depend on them. He also believed that revelation could not contradict reason. Like the deists, Mendelssohn claimed that reason could discover the reality of God, divine providence, and immortality of the soul. He was the first to speak out against the use of excommunication as a religious threat. At the height of his career, in 1769, Mendelssohn was publicly challenged by a Christian apologist, a Zurich pastor named John Lavater, to defend the superiority of Judaism over Christianity. From then on, he was involved in defending Judaism in print. In 1783, he published ''Jerusalem, or On Religious Power and Judaism''. Speculating that no religious institution should use coercion and emphasized that Judaism does not coerce the mind through dogma, he argued that through reason, all people could discover religious philosophical truths, but what made Judaism unique was its revealed code of legal, ritual, and moral law. He said that Jews must live in civil society, but only in a way that their right to observe religious laws is granted, while also recognizing the needs for respect, and multiplicity of religions. He campaigned for emancipation and instructed Jews to form bonds with the gentile governments, attempting to improve the relationship between Jews and Christians while arguing for tolerance and humanity. He became the symbol of the Jewish Enlightenment, the Haskalah.

Early 19th Century

estate

Estate or The Estate may refer to:

Law

* Estate (law), a term in common law for a person's property, entitlements and obligations

* Estates of the realm, a broad social category in the histories of certain countries.

** The Estates, representat ...

regulations. In different ways from one territory of the empire to another, these regulations classified inhabitants into different groups, such as dynasts, members of the court entourage, other aristocrats, city dwellers ( burghers), Jews, Huguenots (in Prussia a special estate until 1810), free peasant

Free tenants, also known as free peasants, were tenant farmer peasants in medieval England who occupied a unique place in the medieval hierarchy. They were characterized by the low rents which they paid to their manorial lord. They were subj ...

s, serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s, peddlers and Gypsies, with different privileges and burdens attached to each classification. Legal inequality was the principle.

The concept of citizenship was mostly restricted to cities, especially Free Imperial Cities. No general franchise existed, which remained a privilege for the few, who had inherited the status or acquired it when they reached a certain level of taxed income or could afford the expense of the citizen's fee (''Bürgergeld''). Citizenship was often further restricted to city dwellers affiliated to the locally dominant Christian denomination ( Calvinism, Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, or Lutheranism). City dwellers of other denominations or religions and those who lacked the necessary wealth to qualify as citizens were considered to be mere inhabitants who lacked political rights, and were sometimes subject to revocable residence permits.

Most Jews then living in those parts of Germany that allowed them to settle were automatically defined as mere indigenous inhabitants, depending on permits that were typically less generous than those granted to gentile indigenous inhabitants (''Einwohner'', as opposed to ''Bürger'', or citizen). In the 18th century, some Jews and their families (such as Daniel Itzig in Berlin) gained equal status with their Christian fellow city dwellers, but had a different status from noblemen, Huguenots, or serfs. They often did not enjoy the right to freedom of movement across territorial or even municipal boundaries, let alone the same status in any new place as in their previous location.

With the abolition of differences in legal status during the Napoleonic era and its aftermath, citizenship was established as a new franchise generally applying to all former subjects of the monarchs. Prussia conferred citizenship on the Prussian Jews in 1812, though this by no means resulted in full equality with other citizens. Jewish emancipation did not eliminate all forms of discrimination against Jews, who often remained barred from holding official state positions. The German federal edicts of 1815 merely held out the prospect of full equality, but it was not genuinely implemented at that time, and even the promises which had been made were modified. However, such forms of discrimination were no longer the guiding principle for ordering society, but a violation of it. In Austria, many laws restricting the trade and traffic of Jewish subjects remained in force until the middle of the 19th century in spite of the patent of toleration. Some of the crown lands, such as Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered to ...

and Upper Austria, forbade any Jews to settle within their territory; in Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia many cities were closed to them. The Jews were also burdened with heavy taxes and imposts.

In the German Kingdom of Prussia, the government materially modified the promises made in the disastrous year of 1813. The promised uniform regulation of Jewish affairs was time and again postponed. In the period between 1815 and 1847, no less than 21 territorial laws affecting Jews in the older eight provinces of the Prussian state were in effect, each having to be observed by part of the Jewish community. At that time, no official was authorized to speak in the name of all Prussian Jews, or Jewry in most of the other 41 German states, let alone for all German Jews.

Nevertheless, a few men came forward to promote their cause, foremost among them being Gabriel Riesser (d. 1863), a Jewish lawyer from Hamburg, who demanded full civic equality for his people. He won over public opinion to such an extent that this equality was granted in Prussia on April 6, 1848, in Hanover and Nassau

Nassau may refer to:

Places Bahamas

*Nassau, Bahamas, capital city of the Bahamas, on the island of New Providence

Canada

*Nassau District, renamed Home District, regional division in Upper Canada from 1788 to 1792

*Nassau Street (Winnipeg), ...

on September 5 and on December 12, respectively, and also in his home state of Hamburg, then home to the second-largest Jewish community in Germany. In Württemberg, equality was conceded on December 3, 1861; in Baden on October 4, 1862; in Holstein on July 14, 1863; and in Saxony on December 3, 1868. After the establishment of the North German Confederation by the law of July 3, 1869, all remaining statutory restrictions imposed on the followers of different religions were abolished; this decree was extended to all the states of the German empire after the events of 1870.

The Jewish Enlightenment

During the General Enlightenment (the 1600s to late 1700s), many Jewish women began to frequently visit non-Jewish salons and to campaign for emancipation. In Western Europe and the German states, observance of Jewish law, '' Halacha'', started to be neglected. In the 18th century, some traditional German scholars and leaders, such as the doctor and author of '' Ma'aseh Tuviyyah'', Tobias b. Moses Cohn, appreciated the secular culture. The most important feature during this time was the German ''Aufklärung

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

'', which was able to boast of native figures who competed with the finest Western European writers, scholars, and intellectuals. Aside from the externalities of language and dress, the Jews internalized the cultural and intellectual norms of German society. The movement, becoming known as the German or Berlin Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those ...

offered many effects to the challenges of German society. As early as the 1740s, many German Jews and some individual Polish and Lithuanian Jews had a desire for secular education. The German-Jewish Enlightenment of the late 18th century, the '' Haskalah'', marks the political, social, and intellectual transition of European Jewry to modernity. Some of the elite members of Jewish society knew European languages. Absolutist governments in Germany, Austria, and Russia deprived the Jewish community's leadership of its authority and many Jews became 'Court Jews'. Using their connections with Jewish businessmen to serve as military contractors, managers of mints, founders of new industries and providers to the court of precious stones and clothing, they gave economic assistance to the local rulers. Court Jews were protected by the rulers and acted as did everyone else in society in their speech, manners, and awareness of European literature and ideas. Isaac Euchel, for example, represented a new generation of Jews. He maintained a leading role in the German ''Haskalah'', is one of the founding editors of ''Ha-Me/assef''. Euchel was exposed to European languages and culture while living in Prussian centers: Berlin and Koenigsberg. His interests turned towards promoting the educational interests of the Enlightenment with other Jews. Moses Mendelssohn as another enlightenment thinker was the first Jew to bring secular culture to those living an Orthodox Jewish life. He valued reason and felt that anyone could arrive logically at religious truths while arguing that what makes Judaism unique is its divine revelation of a code of law. Mendelssohn's commitment to Judaism leads to tensions even with some of those who subscribed to Enlightenment philosophy. Faithful Christians who were less opposed to his rationalistic ideas than to his adherence to Judaism found it difficult to accept this ''Juif de Berlin.'' In most of Western Europe, the ''Haskalah'' ended with large numbers of Jews assimilating. Many Jews stopped adhering to Jewish law, and the struggle for emancipation in Germany awakened some doubts about the future of Jews in Europe and eventually led to both immigrations to America and Zionism. In Russia, antisemitism ended the'' Haskalah''. Some Jews responded to this antisemitism by campaigning for emancipation, while others joined revolutionary movements and assimilated, and some turned to Jewish nationalism in the form of the Zionist Hibbat Zion movement.

Reorganization of the German Jewish Community

Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim were two founders of the conservative movement in modern Judaism who accepted the modern spirit of liberalism. Samson Raphael Hirsch defended traditional customs, denying the modern "spirit". Neither of these beliefs was followed by the faithful Jews.

Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim were two founders of the conservative movement in modern Judaism who accepted the modern spirit of liberalism. Samson Raphael Hirsch defended traditional customs, denying the modern "spirit". Neither of these beliefs was followed by the faithful Jews. Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

created a moderate reform movement in assurance with German communities. Public worships were reorganized, reduction of medieval additions to the prayer, congregational singing was introduced, and regular sermons required scientifically trained rabbis. Religious schools were enforced by the state due to a want for the addition of religious structure to secular education of Jewish children. Pulpit oratory started to thrive mainly due to German preachers, such as M. Sachs and M. Joel. Synagogal music was accepted with the help of Louis Lewandowski

Louis Lewandowski (April 3, 1821 – February 4, 1894) was a Polish-Jewish and German-Jewish composer of synagogal music.

He contributed greatly to the liturgy of the Synagogue Service. His most famous works were composed during his tenure as ...

. Part of the evolution of the Jewish community was the cultivation of Jewish literature and associations created with teachers, rabbis, and leaders of congregations.

Another vital part of the reorganization of the Jewish-German community was the heavy involvement of Jewish women in the community and their new tendencies to assimilate their families into a different lifestyle. Jewish women were contradicting their view points in the sense that they were modernizing, but they also tried to keep some traditions alive. German Jewish mothers were shifting the way they raised their children in ways such as moving their families out of Jewish neighborhoods, thus changing who Jewish children grew up around and conversed with, all in all shifting the dynamic of the then close-knit Jewish community. Additionally, Jewish mothers wished to integrate themselves and their families into German society in other ways. Because of their mothers, Jewish children participated in walks around the neighborhood, sporting events, and other activities that would mold them into becoming more like their other German peers. For mothers to assimilate into German culture, they took pleasure in reading newspapers and magazines that focused on the fashion styles, as well as other trends that were up and coming for the time and that the Protestant, bourgeois Germans were exhibiting. Similar to this, German-Jewish mothers also urged their children to partake in music lessons, mainly because it was a popular activity among other Germans. Another effort German-Jewish mothers put into assimilating their families was enforcing the importance of manners on their children. It was noted that non-Jewish Germans saw Jews as disrespectful and unable to grasp the concept of time and place. Because of this, Jewish mothers tried to raise their kids having even better manners than the Protestant children in an effort to combat the pre-existing stereotype put on their children. In addition, Jewish mothers put a large emphasis on proper education for their children in hopes that this would help them grow up to be more respected by their communities and eventually lead to prosperous careers. While Jewish mothers worked tirelessly on ensuring the assimilation of their families, they also attempted to keep the familial aspect of Jewish traditions. They began to look at Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical storie ...

and holidays as less of culturally Jewish days, but more as family reunions of sorts. What was once viewed as a more religious event became more of a social gathering of relatives.

Birth of the Reform Movement

The beginning of theReform Movement in Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

was emphasized by David Philipson

David Philipson (August 9, 1862 – June 29, 1949) was an American Reform rabbi, orator, and author.

The son of German-Jewish immigrants, he was a member of the first graduating class of the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. As an adult, he ...

, who was the rabbi at the largest Reform congregation. The increasing political centralization of the late 18th and early 19th centuries undermined the societal structure that perpetuated traditional Jewish life. Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

ideas began to influence many intellectuals, and the resulting political, economic, and social changes were overpowering. Many Jews felt a tension between Jewish tradition and the way they were now leading their lives-religiously- resulting in less tradition. As the insular religious society that reinforced such observance disintegrated, falling away from vigilant observance without deliberately breaking with Judaism was easy. Some tried to reconcile their religious heritage with their new social surroundings; they reformed traditional Judaism to meet their new needs and to express their spiritual desires. A movement was formed with a set of religious beliefs, and practices that were considered expected and tradition. Reform Judaism was the first modern response to the Jew's emancipation, though reform Judaism differing in all countries caused stresses of autonomy on both the congregation and individual. Some of the reforms were in the practices: circumcisions

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topi ...

were abandoned, rabbis wore vests after Protestant ministers, and instrumental accompaniment was used: pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurized air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks ...

s. In addition, the traditional Hebrew prayer book was replaced by German text, and reform synagogues began being called temples which were previously considered the Temple of Jerusalem. Reform communities composed of similar beliefs and Judaism changed at the same pace as the rest of society had. The Jewish people have adapted to religious beliefs and practices to the meet the needs of the Jewish people throughout the generation.

1815–1918

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

emancipated the Jews across Europe, but with Napoleon's fall in 1815, growing nationalism resulted in increasing repression. From August to October 1819, pogroms that came to be known as the Hep-Hep riots took place throughout Germany. Jewish property was destroyed, and many Jews were killed.

During this time, many German states stripped Jews of their civil rights. In the Free City of Frankfurt

For almost five centuries, the German city of Frankfurt was a city-state within two major Germanic entities:

*The Holy Roman Empire as the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt () (until 1806)

*The German Confederation as the Free City of Frankfurt ...

, only 12 Jewish couples were allowed to marry each year, and the 400,000 florins

The Florentine florin was a gold coin struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time. It had 54 grains (3.499 grams, 0.113 troy ounce) of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a purcha ...

the city's Jewish community had paid in 1811 for its emancipation was forfeited. After the Rhineland reverted to Prussian control, Jews lost the rights Napoleon had granted them, were banned from certain professions, and the few who had been appointed to public office before the Napoleonic Wars were dismissed. Throughout numerous German states, Jews had their rights to work, settle, and marry restricted. Without special letters of protection, Jews were banned from many different professions, and often had to resort to jobs considered unrespectable, such as peddling or cattle dealing, to survive. A Jewish man who wanted to marry had to purchase a registration certificate, known as a ''Matrikel'', proving he was in a "respectable" trade or profession. A ''Matrikel'', which could cost up to 1,000 florins, was usually restricted to firstborn sons.Sachar, Howard M.: ''A History of the Jews in America'' – Vintage Books As a result, most Jewish men were unable to legally marry. Throughout Germany, Jews were heavily taxed, and were sometimes discriminated against by gentile craftsmen.

As a result, many German Jews began to emigrate. The emigration was encouraged by German-Jewish newspapers. At first, most emigrants were young, single men from small towns and villages. A smaller number of single women also emigrated. Individual family members would emigrate alone, and then send for family members once they had earned enough money. Emigration eventually swelled, with some German Jewish communities losing up to 70% of their members. At one point, a German-Jewish newspaper reported that all the young Jewish males in the Franconian towns of Hagenbach

Hagenbach () is a town in the district of Germersheim, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is situated near the border with France, on the left bank of the Rhine, approx. 10 km west of Karlsruhe.

Hagenbach is the seat of the ''Verbandsgem ...

, Ottingen

Oettingen in Bayern (Swabian German, Swabian: ''Eadi'') is a Town#Germany, town in the Donau-Ries district, in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany. It is situated northwest of Donauwörth, and northeast of Nördlingen.

Geography

The town is located on th ...

, and Warnbach had emigrated or were about to emigrate. The United States was the primary destination for emigrating German Jews.

The Revolutions of 1848 swung the pendulum back towards freedom for the Jews. A noted reform rabbi of that time was Leopold Zunz

Leopold Zunz ( he, יום טוב צונץ—''Yom Tov Tzuntz'', yi, ליפמן צונץ—''Lipmann Zunz''; 10 August 1794 – 17 March 1886) was the founder of academic Judaic Studies (''Wissenschaft des Judentums''), the critical investigation ...

, a contemporary and friend of Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, writer and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of '' Lied ...

. In 1871, with the unification of Germany by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, came their emancipation, but the growing mood of despair among assimilated Jews was reinforced by the antisemitic penetrations of politics. In the 1870s, antisemitism was fueled by the financial crisis and scandals; in the 1880s by the arrival of masses of ''Ostjuden

The expression 'Eastern European Jewry' has two meanings. Its first meaning refers to the current political spheres of the Eastern European countries and its second meaning refers to the Jewish communities in Russia and Poland. The phrase 'Easte ...

'', fleeing from Russian territories; by the 1890s it was a parliamentary presence, threatening anti-Jewish laws. In 1879 the Hamburg anarchist pamphleteer Wilhelm Marr

Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Marr (November 16, 1819 – July 17, 1904) was a German agitator and journalist, who popularized the term "antisemitism" (1881) hich was invented by Moritz Steinschneider

Life

Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son ...

introduced the term 'antisemitism' into the political vocabulary by founding the Antisemitic League

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Antisemites of the ''völkisch movement

The ''Völkisch'' movement (german: Völkische Bewegung; alternative en, Folkist Movement) was a German ethno-nationalist movement active from the late 19th century through to the Nazi era, with remnants in the Federal Republic of Germany af ...

'' were the first to describe themselves as such, because they viewed Jews as part of a Semitic race that could never be properly assimilated into German society. Such was the ferocity of the anti-Jewish feeling of the völkisch movement that by 1900, ''antisemitic'' had entered German to describe anyone who had anti-Jewish feelings. However, despite massive protests and petitions, the völkisch movement failed to persuade the government to revoke Jewish emancipation, and in the 1912 Reichstag elections, the parties with völkisch-movement sympathies suffered a temporary defeat.

Jews experienced a period of legal equality after 1848. Baden and Württemberg passed the legislation that gave the Jews complete equality before the law in 1861–64. The newly formed

Jews experienced a period of legal equality after 1848. Baden and Württemberg passed the legislation that gave the Jews complete equality before the law in 1861–64. The newly formed German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

did the same in 1871. Historian Fritz Stern concludes that by 1900, what had emerged was a Jewish-German symbiosis, where German Jews had merged elements of German and Jewish culture into a unique new one. Marriages between Jews and non-Jews became somewhat common from the 19th century; for example, the wife of German Chancellor Gustav Stresemann was Jewish. However, opportunity for high appointments in the military, the diplomatic service, judiciary or senior bureaucracy was very small. Some historians believe that with emancipation the Jewish people lost their roots in their culture and began only using German culture. However, other historians including Marion A. Kaplan, argue that it was the opposite and Jewish women were the initiators of balancing both Jewish and German culture during Imperial Germany. Jewish women played a key role in keeping the Jewish communities in tune with the changing society that was evoked by the Jews being emancipated. Jewish women were the catalyst of modernization within the Jewish community. The years 1870–1918 marked the shift in the women's role in society. Their job in the past had been housekeeping and raising children. Now, however, they began to contribute to the home financially. Jewish mothers were the only tool families had to linking Judaism with German culture

The culture of Germany has been shaped by major intellectual and popular currents in Europe, both religious and secular. Historically, Germany has been called ''Das Land der Dichter und Denker'' (the country of poets and thinkers). German cultu ...

. They felt it was their job to raise children that would fit in with bourgeois Germany. Women had to balance enforcing German traditions while also preserving Jewish traditions. Women were in charge of keeping kosher and the Sabbath; as well as, teaching their children German speech and dressing them in German clothing. Jewish women attempted to create an exterior presence of German while maintaining the Jewish lifestyle inside their homes.

During the history of the German Empire, there were various divisions within the German Jewish community over its future; in religious terms, Orthodox Jews

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Jewish theology, Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Torah, Written and Oral Torah, Or ...

sought to keep to Jewish religious tradition, while liberal Jews sought to "modernise" their communities by shifting from liturgical traditions to organ music and German-language prayers.

The Jewish population grew from 512,000 in 1871 to 615,000 in 1910, including 79,000 recent immigrants from Russia, just under one percent of the total. About 15,000 Jews converted to Christianity between 1871 and 1909. The typical attitude of German liberals towards Jews was that they were in Germany to stay and were capable of being assimilated; anthropologist and politician Rudolf Virchow summarised this position, saying "The Jews are simply here. You cannot strike them dead." This position, however, did not tolerate cultural differences between Jews and non-Jews, advocating instead eliminating this difference.

World War I

A higher percentage of German Jews fought in World War I than of any other ethnic, religious or political group in Germany; around 12,000 died in the fighting.

Many German Jews supported the war out of patriotism; like many Germans, they viewed Germany's actions as defensive in nature and even

A higher percentage of German Jews fought in World War I than of any other ethnic, religious or political group in Germany; around 12,000 died in the fighting.

Many German Jews supported the war out of patriotism; like many Germans, they viewed Germany's actions as defensive in nature and even left-liberal

Social liberalism (german: Sozialliberalismus, es, socioliberalismo, nl, Sociaalliberalisme), also known as new liberalism in the United Kingdom, modern liberalism, or simply liberalism in the contemporary United States, left-liberalism ...

Jews believed Germany was responding to the actions of other countries, particularly Russia. For many Jews it was never a question as to whether or not they would stand behind Germany, it was simply a given that they would. The fact that the enemy was Russia also gave an additional reason for German Jews to support the war; Tsarist Russia Tsarist Russia may refer to:

* Grand Duchy of Moscow (1480–1547)

*Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721)

*Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of ...

was regarded as the oppressor in the eyes of German Jews for its pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

and for many German Jews, the war against Russia would become a sort of holy war. While there was partially a desire for vengeance, for many Jews ensuring Russia's Jewish population was saved from a life of servitude was equally important – one German-Jewish publication stated "We are fighting to protect our holy fatherland, to rescue European culture and to liberate our brothers in the east." War fervour was as common amongst Jewish communities as it was amongst ethnic Germans ones. The main Jewish organisation in Germany, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, declared unconditional support for the war and when August 5 was declared by the Kaiser to be a day of patriotic prayer, synagogues across Germany surged with visitors and filled with patriotic prayers and nationalistic speeches.

While going to war brought the unsavoury prospect of fighting fellow Jews in Russia, France and Britain, for the majority of Jews this severing of ties with Jewish communities in the

While going to war brought the unsavoury prospect of fighting fellow Jews in Russia, France and Britain, for the majority of Jews this severing of ties with Jewish communities in the Entente

Entente, meaning a diplomatic "understanding", may refer to a number of agreements:

History

* Entente (alliance), a type of treaty or military alliance where the signatories promise to consult each other or to cooperate with each other in case o ...