George Lansbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

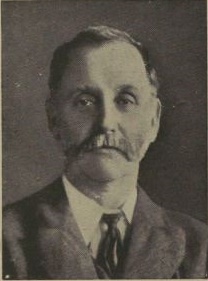

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and

George Lansbury was born in

George Lansbury was born in

In 1881, the first of Lansbury's twelve children, Bessie, was born; another daughter, Annie, followed in 1882. Seeking to improve his family's prospects, Lansbury decided that their best hopes of prosperity lay in emigrating to Australia. The London agent-general for

In 1881, the first of Lansbury's twelve children, Bessie, was born; another daughter, Annie, followed in 1882. Seeking to improve his family's prospects, Lansbury decided that their best hopes of prosperity lay in emigrating to Australia. The London agent-general for

In 1888 Lansbury agreed to act as election agent for

In 1888 Lansbury agreed to act as election agent for

Lansbury's choice of the SDF, from several socialist organisations, reflected his admiration for Hyndman, whom he considered "one of the truly great ones". Lansbury quickly became the federation's most tireless propagandist, travelling throughout Britain to address meetings or to demonstrate solidarity with workers involved in industrial disputes. Around this time, Lansbury temporarily set aside his Christian beliefs and became a member of the East London

Lansbury's choice of the SDF, from several socialist organisations, reflected his admiration for Hyndman, whom he considered "one of the truly great ones". Lansbury quickly became the federation's most tireless propagandist, travelling throughout Britain to address meetings or to demonstrate solidarity with workers involved in industrial disputes. Around this time, Lansbury temporarily set aside his Christian beliefs and became a member of the East London

In the general election of January 1906 Lansbury stood as an independent socialist candidate in

In the general election of January 1906 Lansbury stood as an independent socialist candidate in

The ''Daily Herald'' began as a temporary bulletin during the London printers' strike of 1910–11. After the strike ended, Lansbury and others raised sufficient funds for the ''Herald'' to be relaunched in April 1912 as a socialist daily newspaper. The paper attracted contributions from distinguished writers such as

The ''Daily Herald'' began as a temporary bulletin during the London printers' strike of 1910–11. After the strike ended, Lansbury and others raised sufficient funds for the ''Herald'' to be relaunched in April 1912 as a socialist daily newspaper. The paper attracted contributions from distinguished writers such as

social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

, he spent his political life campaigning against established authority and vested interests, his main causes being the promotion of social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fu ...

, women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

, and world disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, such as n ...

.

Originally a radical Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

, Lansbury became a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

in the early 1890s, and thereafter served his local community in the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

in numerous elective offices. His activities were underpinned by his Christian beliefs which, except for a short period of doubt, sustained him through his life. Elected to the UK Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremac ...

in 1910, he resigned his seat in 1912 to campaign for women's suffrage, and was briefly imprisoned after publicly supporting militant action.

In 1912, Lansbury helped to establish the '' Daily Herald'' newspaper, and became its editor. Throughout the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the paper maintained a strongly pacifist stance, and supported the October 1917 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

. These positions contributed to Lansbury's failure to be elected to Parliament in 1918. He devoted himself to local politics in his home borough of Poplar, and went to prison with 30 fellow-councillors for his part in the Poplar Rates Rebellion

The Poplar Rates Rebellion, or Poplar Rates Revolt, was a tax protest that took place in Poplar, London, England, in 1921. It was led by George Lansbury, the previous year's Labour Mayor of Poplar, with the support of the Poplar Borough Council, ...

of 1921.

After his return to Parliament in 1922, Lansbury was denied office in the brief Labour government of 1924, although he served as First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequent to 1922, within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irel ...

in the Labour government of 1929–31. After the political and economic crisis of August 1931, Lansbury did not follow his leader, Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

, into the National Government, but remained with the Labour Party. As the most senior of the small contingent of Labour MPs that survived the 1931 UK general election

Events

January

* January 2 – South Dakota native Ernest Lawrence invents the cyclotron, used to accelerate particles to study nuclear physics.

* January 4 – German pilot Elly Beinhorn begins her flight to Africa.

* January 22 – Sir I ...

, Lansbury became the Leader of the Labour Party. His pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

and his opposition to rearmament in the face of rising European fascism

Fascism in Europe was the set of various fascist ideologies which were practised by governments and political organisations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, influen ...

put him at odds with his party, and when his position was rejected at the 1935 Labour Party conference, he resigned the leadership. He spent his final years travelling through the United States and Europe in the cause of peace and disarmament.

Early life

East End upbringing

George Lansbury was born in

George Lansbury was born in Halesworth

Halesworth is a market town, civil parish and electoral ward in north-eastern Suffolk, England. The population stood at 4,726 in the 2011 Census. It lies south-west of Lowestoft, on a tributary of the River Blyth, upstream from Southwold. T ...

in the county of Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

on 22 February 1859. He was the third of nine children born to a railway worker, also named George Lansbury, and Anne Lansbury (née Ferris). George senior's job involved the supervision of railway construction gangs; the family was often on the move, and living conditions were primitive. Through his progressive-minded mother and grandmother, young George became familiar with the names of great contemporary reformers—Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty.

As a young ...

and John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn Laws ...

—and began to read the radical '' Reynolds's Newspaper''. By the end of 1868, the family had moved into the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

, the district in which Lansbury would live and work for almost all his life.

The essayist Ronald Blythe

Ronald George Blythe (born 6 November 1922)"Dr Ronald Blythe ...

has described the East End of the 1860s and 1870s as "stridently English ... The smoke-blackened streets were packed with illiterate multitudes hostayed alive through sheer birdlike ebullience".Blythe, p. 272 Interspersed with spells of work, Lansbury attended schools in Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in the East End of London northeast of Charing Cross. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the common land, Green, much of which survives today as Bethnal Green Gardens, beside Cambridge Heat ...

and Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

. He then held a succession of manual jobs, including work as a coaling contractor in partnership with his elder brother, James, loading and unloading coal wagons. This was heavy and dangerous work, and led to at least one near-fatal accident.Shepherd 2002, pp. 8–9

During his adolescence and early adulthood, Lansbury was a regular attender at the public gallery at the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, where he heard and remembered many of Gladstone's speeches on the main foreign policy issue of the day, the " Eastern Question". He was present at the riots which erupted outside Gladstone's house on 24 February 1878 after a peace meeting in Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

. Shepherd writes that Gladstone's Liberalism, proclaiming liberty, freedom and community interests was "a heady mix that left an indelible mark" on the youthful Lansbury.Shepherd 2002, pp. 10–11

George Lansbury senior died in 1875. That year young George met fourteen-year-old Elizabeth Brine, whose father Isaac Brine owned a local sawmill. The couple eventually married in 1880, at Whitechapel parish church, where the vicar, J. Franklin Kitto, had been Lansbury's spiritual guide and counsellor. Apart from a period of doubt in the 1890s when he temporarily rejected the Church, Lansbury remained a staunch Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

until his death.Postgate, pp. 13–20

Australia

In 1881, the first of Lansbury's twelve children, Bessie, was born; another daughter, Annie, followed in 1882. Seeking to improve his family's prospects, Lansbury decided that their best hopes of prosperity lay in emigrating to Australia. The London agent-general for

In 1881, the first of Lansbury's twelve children, Bessie, was born; another daughter, Annie, followed in 1882. Seeking to improve his family's prospects, Lansbury decided that their best hopes of prosperity lay in emigrating to Australia. The London agent-general for Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

depicted a land of boundless opportunities, with work for all; seduced by this appealing prospect, Lansbury and Bessie raised the necessary passage money, and in May 1884 set sail with their children for Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

.Postgate, pp. 22–23

On the outward passage, the family experienced illness, discomfort and danger; on one occasion the ship came close to foundering during a monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

. On arrival at Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

in July 1884, Lansbury found that, contrary to the London agent's promises, there was a superfluity of labour and work was hard to come by. His first job, breaking stone, proved to be too physically punishing; he moved to a better-paid position as a van driver, but was sacked when, for religious reasons, he refused to work on Sundays.Postgate, pp. 24–29 He then contracted to work on a farm some 80 miles inland, to find upon arrival that his employer had misled him about living conditions and terms of employment.Shepherd 2002, pp. 13–15

For several months, the Lansbury family lived in extreme squalor before Lansbury secured release from the contract. Back in Brisbane, he worked for a while at the newly built Brisbane cricket ground. As a keen follower of the game he hoped to see the visiting English touring team play but, as Lansbury's biographer Raymond Postgate

Raymond William Postgate (6 November 1896 – 29 March 1971) was an English socialist, writer, journalist and editor, social historian, mystery novelist, and gourmet who founded the '' Good Food Guide''. He was a member of the Postgate fa ...

records, "he learned that cricket watching was not a pleasure for workmen".

Throughout his tenure in Australia, Lansbury sent letters home, revealing the truth about conditions facing immigrants. To a friend he wrote in March 1885: "Mechanics are ''not'' wanted. Farm labourers are ''not'' wanted ... Hundreds of men and women are not able to get work ... The streets are foul day and night, and if I had a sister I would ''shoot her dead'' rather than see her brought out to this little hell on earth". In May 1885, having received from his father-in-law Isaac Brine sufficient funds for a passage home, the Lansbury family left Australia for good and returned to London.

Radical Liberal

First campaigns

On his return to London, Lansbury took a job in Brine's timber business. In his spare time he campaigned against the false prospectuses offered by colonial emigration agents. His speech at an emigration conference at King's College in London in April 1886 impressed delegates; shortly afterwards, the government established an Emigration Information Bureau under theColonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of col ...

. This body was required to provide accurate information on the state of labour markets in all the government's overseas possessions.

Having joined the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

shortly after his return from Australia, Lansbury became first a ward secretary and then general secretary for the Bow and Bromley Liberal and Radical Association. His effective campaigning skills had been noted by leading Liberals, including Samuel Montagu

Samuel Montagu, 1st Baron Swaythling (21 December 1832 – 12 January 1911), was a British banker who founded the bank of Samuel Montagu & Co. He was a philanthropist and Liberal politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1885 to 1900, a ...

, the Liberal MP for Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

, who persuaded the young activist to be his agent in the 1885 general election.Shepherd 2002, pp. 19–20 Lansbury's handling of this election campaign prompted Montagu to urge him to stand for parliament himself. Lansbury declined this, partly on practical grounds (MPs were then unpaid and he had to provide for his family), and partly on principle; he was becoming increasingly convinced that his future lay not as a radical Liberal but as a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. He continued to serve the Liberals, as an agent and local secretary, while expressing his socialism in a short-lived monthly radical journal, ''Coming Times'', which he founded and co-edited with a fellow-dissident, William Hoffman.

London County Council elections, 1889

In 1888 Lansbury agreed to act as election agent for

In 1888 Lansbury agreed to act as election agent for Jane Cobden

Emma Jane Catherine Cobden (28 April 1851 – 7 July 1947), known as Jane Cobden, was a British Liberal politician who was active in many radical causes. A daughter of the Victorian reformer and statesman Richard Cobden, she was an early ...

, who was contesting the first elections for the newly formed London County Council

London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today kno ...

(LCC) as Liberal candidate for the Bow and Bromley division. Cobden, an early supporter of women's suffrage, was the fourth child of the Victorian radical statesman Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti-Corn Law League and the Cobden–Chevalier Treaty.

As a young ...

. The Society for Promoting Women as County Councillors (SPWCC), a new women's rights group, had proposed Cobden as the candidate for Bow and Bromley and Margaret Sandhurst

Margaret Mansfield, Baroness Sandhurst (née Fellowes, ca. 1828 - 7 January 1892) was a noted suffragist who was one of the first women elected to a city council in the United Kingdom. She was also a prominent spiritualist.

Personal life

Sandhur ...

for Brixton. Lansbury counselled Cobden in the issues of greatest concern to the East End electorate: housing for the poor, ending of sweated labour, rights of public assembly, and control of the police. Specific questions of women's rights were largely avoided during the campaign. On 19 January 1889 both women were elected; these triumphs were, however, short-lived. Sandhurst's qualification to serve as a county councillor was successfully challenged in the courts by her Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

opponents on the grounds of her sex, and her subsequent appeal was dismissed. Cobden was not immediately challenged, but in April 1891, after a series of legal actions, she was effectively neutered as a councillor by being prevented from voting on pain of severe financial penalties. Lansbury urged her, during the hearings, to "go to prison and let the Council back you up by refusing to declare your seat vacant". Cobden did not follow this path. A Bill introduced in the House of Commons in May 1891 permitting women to serve as county councillors found little support among MPs of any party; women were not granted this right until 1907.

Lansbury was offended by his party's lukewarm support for women's rights. In a letter published in the ''Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'' he made an open call to Bow and Bromley's Liberals to "shake themselves free of party feeling and throw the energy and ability they are now wasting on minor questions into ... securing the full rights of citizenship to every woman in the land". He was further disillusioned by his party's failure to endorse the eight-hour maximum working day. Lansbury had formed the view, expressed some years later, that "Liberalism would progress just as far as the great money bags of capitalism would allow it to progress". By 1892 the Liberals no longer felt like Lansbury's political home; most of his current associates were avowed socialists: William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, Eleanor Marx

Jenny Julia Eleanor Marx (16 January 1855 – 31 March 1898), sometimes called Eleanor Aveling and known to her family as Tussy, was the English-born youngest daughter of Karl Marx. She was herself a socialist activist who sometimes worked as a ...

, John Burns

John Elliot Burns (20 October 1858 – 24 January 1943) was an English trade unionist and politician, particularly associated with London politics and Battersea. He was a socialist and then a Liberal Member of Parliament and Minister. He was ...

and Henry Hyndman

Henry Mayers Hyndman (; 7 March 1842 – 20 November 1921) was an English writer, politician and socialist.

Originally a conservative, he was converted to socialism by Karl Marx's ''Communist Manifesto'' and launched Britain's first left-wing p ...

, founder of the Social Democratic Federation

The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) was established as Britain's first organised socialist political party by H. M. Hyndman, and had its first meeting on 7 June 1881. Those joining the SDF included William Morris, George Lansbury, James Con ...

(SDF). Nevertheless, Lansbury did not resign from the Liberals until he had fulfilled a commitment to act as election agent for John Murray MacDonald, the prospective Liberal candidate for Bow and Bromley. He saw his candidate victorious in the July 1892 general election; as soon as the result was declared, Lansbury resigned from the Liberal Party and joined the SDF.

Socialist reformer

Social Democratic Federation

Lansbury's choice of the SDF, from several socialist organisations, reflected his admiration for Hyndman, whom he considered "one of the truly great ones". Lansbury quickly became the federation's most tireless propagandist, travelling throughout Britain to address meetings or to demonstrate solidarity with workers involved in industrial disputes. Around this time, Lansbury temporarily set aside his Christian beliefs and became a member of the East London

Lansbury's choice of the SDF, from several socialist organisations, reflected his admiration for Hyndman, whom he considered "one of the truly great ones". Lansbury quickly became the federation's most tireless propagandist, travelling throughout Britain to address meetings or to demonstrate solidarity with workers involved in industrial disputes. Around this time, Lansbury temporarily set aside his Christian beliefs and became a member of the East London Ethical Society

The Ethical movement, also referred to as the Ethical Culture movement, Ethical Humanism or simply Ethical Culture, is an ethical, educational, and religion, religious movement that is usually traced back to Felix Adler (professor), Felix Adler ...

. One factor in his disillusion with the Church was the local clergy's unsympathetic approach to poor relief, and their opposition to collective political action.

In 1895 Lansbury fought two parliamentary elections for the SDF in Walworth

Walworth () is a district of south London, England, within the London Borough of Southwark. It adjoins Camberwell to the south and Elephant and Castle to the north, and is south-east of Charing Cross.

Major streets in Walworth include the Old ...

, first a by-election on 14 May, then the 1895 general election two months later. Despite his energetic campaigning he was heavily defeated on each occasion, with tiny proportions of the vote. After these dismal results, Lansbury was persuaded by Hyndman to give up his job at the sawmill and become the SDF's full-time salaried national organiser. He preached a straightforward revolutionary doctrine: "The time has arrived", he informed an audience at Todmorden

Todmorden ( ; ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Upper Calder Valley in Calderdale, West Yorkshire, England. It is north-east of Manchester, south-east of Burnley and west of Halifax, West Yorkshire, Hal ...

in Lancashire, "for the working classes to seize political power and use it to overthrow the competitive system and establish in its place state cooperation". Lansbury's time as SDF national organiser did not last long; in 1896, when Isaac Brine died suddenly, Lansbury thought that his family duty required him to take charge of the sawmill, and he returned home to Bow.

In the general election of 1900 a pact with the Liberals in the Bow and Bromley constituency gave Lansbury, the SDF candidate, a straight fight against the Conservative incumbent, Walter Murray Guthrie. Lansbury's cause was hindered by his public opposition to the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

at a time when war fever was strong, while Guthrie, a former soldier, stressed his military credentials. Lansbury lost the election, though his total of 2,258 votes against Guthrie's 4,403 was considered creditable by the press. This campaign was Lansbury's last major effort on behalf of the SDF. He became disenchanted by Hyndman's inability to work with other socialist groups, and in about 1903 resigned from the SDF to join the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP). At around this time, Lansbury rediscovered his Christian faith and rejoined the Anglican Church.

Poor Law guardian

In April 1893 Lansbury achieved his first elective office when he became aPoor Law guardian

Boards of guardians were ''ad hoc'' authorities that administered Poor Law in the United Kingdom from 1835 to 1930.

England and Wales

Boards of guardians were created by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, replacing the parish overseers of the poor ...

for the district of Poplar. In place of the traditionally harsh workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

regime that was the norm, Lansbury proposed a programme of reform, whereby the workhouse became "an agency of help instead of a place of despair", and the stigma of poverty was removed.Shepherd 2002, pp. 54–56 Lansbury was one of a minority socialist bloc which was often able, through its energy and commitment, to win support for its plans.

Education for the poor was one of Lansbury's major concerns. He helped to transform the Forest Gate District School, previously a punitive establishment run on quasi-military lines, into a proper place of education that became the Poplar Training School, and was still in existence more than half a century later. At the 1897 annual Poor Law Conference Lansbury summarised his views on poor relief in his first published paper: "The Principles of the English Poor Law". His analysis offered a Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

critique of capitalism: only the reorganisation of industry on collectivist lines would solve contemporary problems.

Lansbury added to his public duties when, in 1903, he was elected to Poplar Borough Council. In the summer of that year he met Joseph Fels

Joseph Fels (16 December 1853–22 February 1914) was an American soap manufacturer, millionaire, Georgist and philanthropist.

Biography

Born of German Jewish immigrants in Halifax County, Virginia, Fels moved with his family to Baltimore i ...

, a rich American soap manufacturer with a penchant for social projects. Lansbury persuaded Fels, in 1904, to purchase a 100-acre farm at Laindon

Laindon is a commuter town in Essex, between Basildon and West Horndon. It was an ancient parish in Essex, England, that was abolished for civil purposes in 1937. It was based on the (probably smaller) manor of the same name and now lies mostly ...

, in Essex, which was converted into a labour colony that provided regular work for Poplar's unemployed and destitute. Fels also agreed to finance a much larger colony at Hollesley Bay in Suffolk, to be operated as a government scheme under the Local Government Board

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 (C. 70) and took over the public health a ...

. Both projects were initially successful, but were undermined after the election of a Liberal government in 1906. The new Local Government minister was John Burns, a former SDF stalwart now ensconced in the Liberal Party who had become a firm opponent of socialism. Burns encouraged a campaign of propaganda to discredit the principle of labour colonies, which were presented as money-wasting ventures that pampered idlers and scroungers. A formal enquiry revealed irregularities in the operation of the scheme, though it exonerated Lansbury. He retained the confidence of his electorate and was easily re-elected to the Board of Guardians in 1907.Postgate, pp. 79–87

In 1905 Lansbury was appointed to a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws, which deliberated for four years. Lansbury, together with Beatrice Webb

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield, (née Potter; 22 January 1858 – 30 April 1943) was an English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer. It was Webb who coined the term ''collective bargaining''. She ...

of the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

, argued for the complete abolition of the Poor Laws and their replacement by a system that incorporated old age pensions, a minimum wage, and national and local public works projects. These proposals were embodied at the commission's conclusion in a minority report signed by Lansbury and Webb; the majority report was, according to Postgate, "an ill-considered jumble of suggestions ... so preposterously inadequate that no attempts were ever made to implement it." Most of the minority's recommendations in time became national policy; the Poor Laws were finally abolished by the Local Government Act 1929

The Local Government Act 1929 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that made changes to the Poor Law and local government in England and Wales.

The Act abolished the system of poor law unions in England and Wales and their board ...

.

National prominence

Campaigner for women's suffrage

In the general election of January 1906 Lansbury stood as an independent socialist candidate in

In the general election of January 1906 Lansbury stood as an independent socialist candidate in Middlesbrough

Middlesbrough ( ) is a town on the southern bank of the River Tees in North Yorkshire, England. It is near the North York Moors national park. It is the namesake and main town of its local borough council area.

Until the early 1800s, the a ...

, on a strong "votes for women" platform. This was his first campaign based on women's rights since the LCC election of 1889. He had been recommended to the constituency by Joseph Fels, who agreed to meet his expenses. The local ILP leadership was committed by an electoral pact to support the Liberal candidate, and could not endorse Lansbury, who secured less than 9 per cent of the vote.Shepherd 2002, pp. 83–88 The campaign had been managed by Marion Coates Hansen

Marion Coates Hansen (''née'' Coates; 3 June 1870 – 2 January 1947) was an English feminist and women's suffrage campaigner, an early member of the militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and a founder member of the Women's Freedom ...

, a prominent local suffragist. Under Hansen's influence Lansbury took up the cause of "votes for women"; he allied himself with the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU), the more militant of the main suffragist organisations, and became a close associate of Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

and her family.Schneer 1990, p. 95

The Liberal government elected in 1906 with a large majority showed little interest in the issue of women's suffrage; when they lost their parliamentary majority in the general election of January 1910 they were dependent on the votes of the 40-odd Labour members. To Lansbury's dismay, Labour did not use this leverage to promote votes for women, instead giving the government virtually unqualified support to keep the Conservatives out of power. Lansbury had failed to win election as Labour's candidate at Bow and Bromley in January 1910; however, the continuing political crisis which developed from David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

's controversial 1909 "People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was bloc ...

" led to another general election in December 1910. Lansbury again fought Bow and Bromley, and this time was successful.

Lansbury found little support in his fight for women's suffrage from his parliamentary Labour colleagues, whom he dismissed as "a weak, flabby lot". In parliament, he denounced the prime minister, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, for the cruelties being inflicted on imprisoned suffragists: "You are beneath contempt ... you ought to be driven from public life". He was temporarily suspended from the House for "disorderly conduct". In October 1912, aware of the unbridgeable gap between his own position and that of his Labour colleagues, Lansbury resigned his seat to fight a by-election in Bow and Bromley on the specific issue of women's suffrage. The suffragettes sent Grace Roe

Eleanor Grace Watney Roe (1885–1979) was Head of Suffragette operations for the Women's Social and Political Union. She was released from prison after the outbreak of World War I due to an amnesty for suffragettes negotiated with the governme ...

to help with the campaign. He lost to his Conservative opponent, who campaigned on the slogan "No Petticoat Government". Commenting on the result, the Labour MP Will Thorne

William James Thorne CBE (4 October 1857 – 2 January 1946) was a British trade unionist, activist and one of the first Labour Members of Parliament.

Early years

Thorne was born in Hockley, Birmingham, on 8 October 1857. His father and othe ...

opined that no constituency could ever be won on the single question of votes for women.

Out of parliament, on 26 April 1913 Lansbury addressed a WSPU rally at the Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no governm ...

, and openly defended violent methods: "Let them burn and destroy property and do anything they will, and for every leader that is taken away, let a dozen step forward in their place". For this, Lansbury was charged with incitement, convicted and, after the dismissal of an appeal, sentenced to three months' imprisonment. He immediately went on hunger strike, and was released after four days; although liable to rearrest under the so-called "Cat and Mouse Act", he was thereafter left at liberty. In the autumn of 1913, at the invitation of Fels, Lansbury and his wife travelled to America and Canada for an extended holiday. On his return, he devoted his main efforts to the recently founded newspaper, the '' Daily Herald''.

War, ''Daily Herald'' and Bolshevism

The ''Daily Herald'' began as a temporary bulletin during the London printers' strike of 1910–11. After the strike ended, Lansbury and others raised sufficient funds for the ''Herald'' to be relaunched in April 1912 as a socialist daily newspaper. The paper attracted contributions from distinguished writers such as

The ''Daily Herald'' began as a temporary bulletin during the London printers' strike of 1910–11. After the strike ended, Lansbury and others raised sufficient funds for the ''Herald'' to be relaunched in April 1912 as a socialist daily newspaper. The paper attracted contributions from distinguished writers such as H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. '' Lansbury used the pages of the ''Daily Herald'' to welcome the February 1917 revolution in Russia as "a new star of hope ... arisen over Europe". At an Albert Hall rally on 18 March 1918 he hailed the spirit and enthusiasm of "this Russian movement", and urged his audience to "be ready to die, if necessary, for our faith". When the war ended in November 1918, Lloyd George called an immediate general election, correctly calculating that victory euphoria would keep his coalition in power. In this triumphalist climate, candidates such as Lansbury who had opposed the war found themselves unpopular, and he failed to retake his Bow and Bromley seat.Postgate, p. 183

The ''Herald'' re-emerged as a daily paper in March 1919. Under Lansbury's direction it maintained a strong and ultimately successful campaign against British intervention in the

Lansbury used the pages of the ''Daily Herald'' to welcome the February 1917 revolution in Russia as "a new star of hope ... arisen over Europe". At an Albert Hall rally on 18 March 1918 he hailed the spirit and enthusiasm of "this Russian movement", and urged his audience to "be ready to die, if necessary, for our faith". When the war ended in November 1918, Lloyd George called an immediate general election, correctly calculating that victory euphoria would keep his coalition in power. In this triumphalist climate, candidates such as Lansbury who had opposed the war found themselves unpopular, and he failed to retake his Bow and Bromley seat.Postgate, p. 183

The ''Herald'' re-emerged as a daily paper in March 1919. Under Lansbury's direction it maintained a strong and ultimately successful campaign against British intervention in the

Throughout his national campaigns, Lansbury remained a Poplar borough councillor and Poor Law guardian, and between 1910 and 1913 served a three-year term as a London County Councillor. In 1919 he became the first Labour mayor of Poplar. Under the then-existing financial system for local government, boroughs were individually responsible for poor relief within their boundaries. This discriminated heavily against poorer councils such as Poplar, where

Throughout his national campaigns, Lansbury remained a Poplar borough councillor and Poor Law guardian, and between 1910 and 1913 served a three-year term as a London County Councillor. In 1919 he became the first Labour mayor of Poplar. Under the then-existing financial system for local government, boroughs were individually responsible for poor relief within their boundaries. This discriminated heavily against poorer councils such as Poplar, where

MacDonald's administration lasted less than a year before, in November 1924, the Liberals withdrew their support; Blythe comments that the first Labour government had been "neither exhilarating nor competent". According to Shepherd, MacDonald's chief priority was to show that Labour was "fit to govern", and he had thus acted with conservative caution. The December general election returned the Conservatives to power; Lansbury maintained that Labour's cause "marches forward irrespective of electoral results". After the defeat Lansbury was briefly touted as an alternative party leader to MacDonald, a proposition he rejected. In 1925, free from the ''Daily Herald'', he founded and edited ''Lansbury's Labour Weekly'', which became a mouthpiece for his personal creed of socialism, democracy and pacifism until it merged with the ''

MacDonald's administration lasted less than a year before, in November 1924, the Liberals withdrew their support; Blythe comments that the first Labour government had been "neither exhilarating nor competent". According to Shepherd, MacDonald's chief priority was to show that Labour was "fit to govern", and he had thus acted with conservative caution. The December general election returned the Conservatives to power; Lansbury maintained that Labour's cause "marches forward irrespective of electoral results". After the defeat Lansbury was briefly touted as an alternative party leader to MacDonald, a proposition he rejected. In 1925, free from the ''Daily Herald'', he founded and edited ''Lansbury's Labour Weekly'', which became a mouthpiece for his personal creed of socialism, democracy and pacifism until it merged with the ''

In the 1929 general election Labour emerged as the largest party, with 287 seats—but without an overall majority. Once again, MacDonald formed a government dependent on Liberal support. Lansbury joined the new cabinet as

In the 1929 general election Labour emerged as the largest party, with 287 seats—but without an overall majority. Once again, MacDonald formed a government dependent on Liberal support. Lansbury joined the new cabinet as  During August, in an atmosphere of financial panic and a run on the pound, the government debated the report. MacDonald and Snowden were prepared to implement it, but Lansbury and nine other cabinet ministers rejected the cut in unemployment benefit. Thus divided, the government could not continue; MacDonald, however, did not resign as prime minister. After discussions with the opposition leaders and the king he formed a national all-party coalition, with a "doctor's mandate" to tackle the economic crisis. The great majority of Labour MPs, including Lansbury, were opposed to this action; MacDonald and the few who followed him were expelled from the party, and

During August, in an atmosphere of financial panic and a run on the pound, the government debated the report. MacDonald and Snowden were prepared to implement it, but Lansbury and nine other cabinet ministers rejected the cut in unemployment benefit. Thus divided, the government could not continue; MacDonald, however, did not resign as prime minister. After discussions with the opposition leaders and the king he formed a national all-party coalition, with a "doctor's mandate" to tackle the economic crisis. The great majority of Labour MPs, including Lansbury, were opposed to this action; MacDonald and the few who followed him were expelled from the party, and

At home, Lansbury served a second term as Mayor of Poplar, in 1936–37. He argued against direct confrontation with Mosley's

At home, Lansbury served a second term as Mayor of Poplar, in 1936–37. He argued against direct confrontation with Mosley's

Historian

Historian

UK: Leader of the Opposition, George Lansbury pleads for peace at League of Nations

Clip from a Paramount Newsreel, circa 1935

Catalogue of the Lansbury papers

at th

of the

Movietone footage of George Lansbury speaking about conditions in slums

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lansbury, George 1859 births 1940 deaths Anglican pacifists Anglican socialists Chairs of the Labour Party (UK) Councillors in Greater London Deaths from cancer in England Deaths from stomach cancer English Christian pacifists English Christian socialists English feminists English reformers English republicans English socialist feminists European democratic socialists Independent Labour Party National Administrative Committee members Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Lansbury family Leaders of the Labour Party (UK) Leaders of the Opposition (United Kingdom) Male feminists Members of London County Council Members of Poplar Metropolitan Borough Council Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People from Halesworth Social Democratic Federation members Transport and General Workers' Union-sponsored MPs UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 UK MPs 1931–1935 UK MPs 1935–1945

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

, G. K. Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, some of whom, Blythe notes, "weren't socialists at all but simply used he paperas a platform for their personal literary anarchy."Blythe, pp. 276–77 Lansbury contributed regularly in support of his various causes, in particular the militant suffrage campaign, and early in 1914 assumed the paper's editorship.

Before the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, the ''Herald'' took a strong anti-war line. Addressing a large demonstration in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commemo ...

on 2 August 1914, Lansbury blamed the coming conflict on capitalism: "The workers of all countries have no quarrel. They are ... exploited in times of peace and sent out to be massacred in times of war". Lansbury's position was at odds with that of most of the Labour movement, which allied itself with the wartime coalition governments of Asquith and, from 1916, Lloyd George. In the prevailing jingoistic mood, numerous readers looked to the ''Herald''—reduced by wartime economies to a weekly format—to present a balanced news perspective, untainted by war fever and chauvinism. During the winter of 1914–15, Lansbury visited the Western Front trenches. He sent eye-witness accounts to the paper, which supported calls for a negotiated peace with Germany in line with President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's later "peace note" of January 1917. The paper also gave sympathetic coverage to conscientious objectors, and to Irish and Indian nationalists.

Lansbury used the pages of the ''Daily Herald'' to welcome the February 1917 revolution in Russia as "a new star of hope ... arisen over Europe". At an Albert Hall rally on 18 March 1918 he hailed the spirit and enthusiasm of "this Russian movement", and urged his audience to "be ready to die, if necessary, for our faith". When the war ended in November 1918, Lloyd George called an immediate general election, correctly calculating that victory euphoria would keep his coalition in power. In this triumphalist climate, candidates such as Lansbury who had opposed the war found themselves unpopular, and he failed to retake his Bow and Bromley seat.Postgate, p. 183

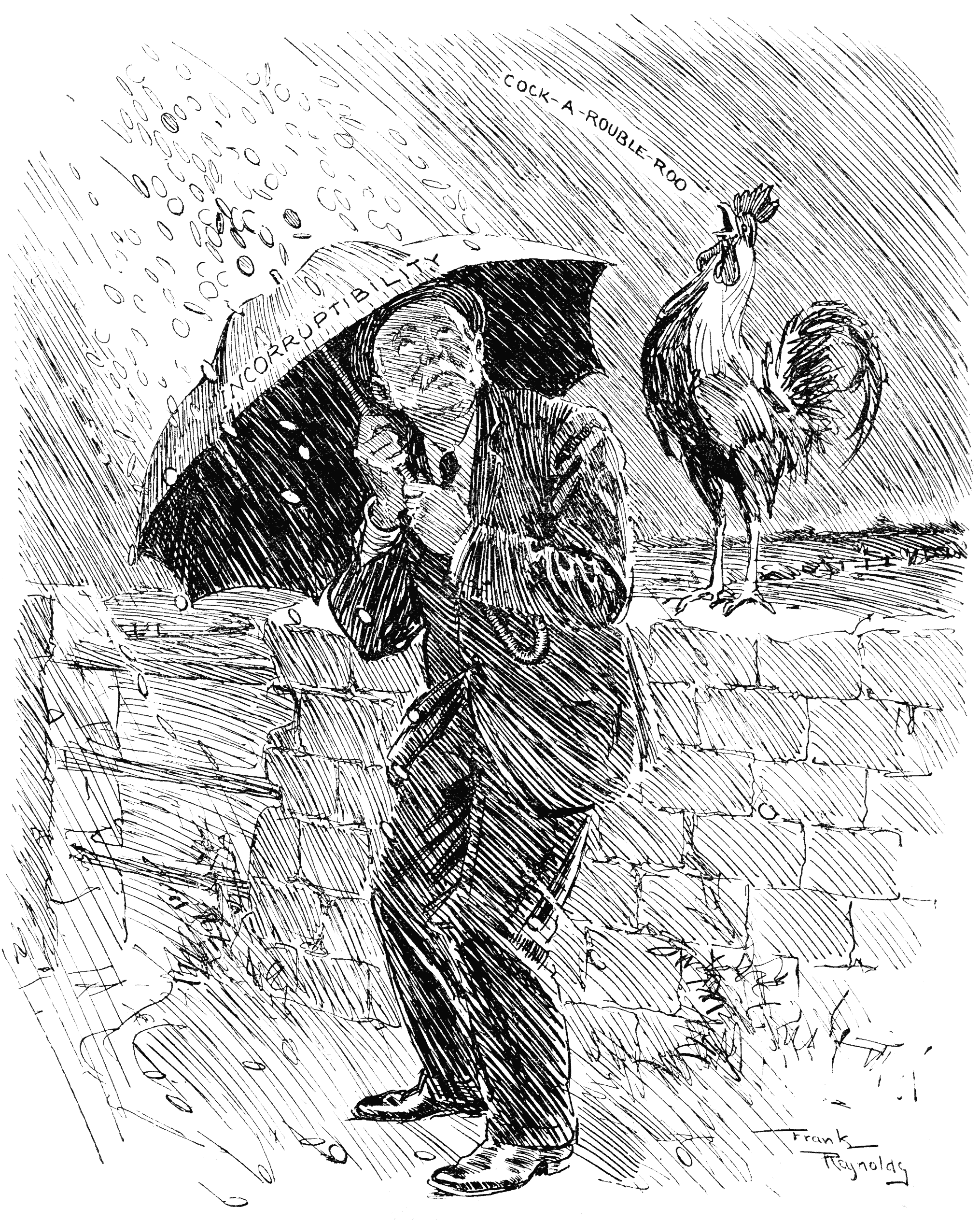

The ''Herald'' re-emerged as a daily paper in March 1919. Under Lansbury's direction it maintained a strong and ultimately successful campaign against British intervention in the

Lansbury used the pages of the ''Daily Herald'' to welcome the February 1917 revolution in Russia as "a new star of hope ... arisen over Europe". At an Albert Hall rally on 18 March 1918 he hailed the spirit and enthusiasm of "this Russian movement", and urged his audience to "be ready to die, if necessary, for our faith". When the war ended in November 1918, Lloyd George called an immediate general election, correctly calculating that victory euphoria would keep his coalition in power. In this triumphalist climate, candidates such as Lansbury who had opposed the war found themselves unpopular, and he failed to retake his Bow and Bromley seat.Postgate, p. 183

The ''Herald'' re-emerged as a daily paper in March 1919. Under Lansbury's direction it maintained a strong and ultimately successful campaign against British intervention in the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. In February 1920 Lansbury travelled to Russia where he met Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

and other Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

leaders. He published an account: ''What I Saw in Russia'', but the impact of the visit was overshadowed by accusations that the ''Herald'' was being financed from Bolshevist sources, a charge vehemently denied by Lansbury: "We have received no Bolshevist money, no Bolshevist paper, no Bolshevist bonds". Unknown to Lansbury, the allegations had some truth which, when exposed, caused him and the paper considerable embarrassment. By 1922 the ''Herald''s financial problems had become such that it could no longer continue as a private venture financed by donations. Lansbury resigned the editorship and made the paper over to the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre

A national trade union center (or national center or central) is a federation or confederation of trade unions in a country. Nearly every country in the world has a national tra ...

(TUC), although he continued to write for it and remained its titular general manager until 3 January 1925.

"Poplarism": the 1921 rates revolt

Throughout his national campaigns, Lansbury remained a Poplar borough councillor and Poor Law guardian, and between 1910 and 1913 served a three-year term as a London County Councillor. In 1919 he became the first Labour mayor of Poplar. Under the then-existing financial system for local government, boroughs were individually responsible for poor relief within their boundaries. This discriminated heavily against poorer councils such as Poplar, where

Throughout his national campaigns, Lansbury remained a Poplar borough councillor and Poor Law guardian, and between 1910 and 1913 served a three-year term as a London County Councillor. In 1919 he became the first Labour mayor of Poplar. Under the then-existing financial system for local government, boroughs were individually responsible for poor relief within their boundaries. This discriminated heavily against poorer councils such as Poplar, where rates

Rate or rates may refer to:

Finance

* Rates (tax), a type of taxation system in the United Kingdom used to fund local government

* Exchange rate, rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another

Mathematics and science

* Rate (mathema ...

revenues were low and poverty and unemployment, always severe, were exacerbated in times of economic recession. Under this system, Postgate argues, "The wealthy West End boroughs were evading responsibility, as though the desolate and silent docks were the results of a failure by the Poplar Borough Council".Postgate, pp. 216–220 In addition to meeting the costs of its own obligations, the council was required to levy precepts

A precept (from the la, præcipere, to teach) is a commandment, instruction, or order intended as an authoritative rule of action.

Religious law

In religion, precepts are usually commands respecting moral conduct.

Christianity

The term is enco ...

to pay for services provided by bodies such as the London County Council and the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

.Shepherd 2002, p. 194 Lansbury had long argued that a degree of rates equalisation across London was necessary, to share costs more fairly.

At its meeting on 22 March 1921 the Poplar Council resolved not to make its precepts and to apply these revenues to the costs of local poor relief. This illegal action created a sensation, and led to legal proceedings against the council. On 29 July the thirty councillors involved marched in procession from Bow to the High Court, headed by a brass band. Informed by the judge that they must apply the precepts, the councillors would not budge; early in September, Lansbury and 29 fellow-councillors were imprisoned for contempt of court. Among those sentenced were his son Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, rev ...

and Edgar's wife, Minnie.

The defiance of the Poplar councillors generated widespread interest and sympathy, and the publicity embarrassed the government. Several other Labour-controlled councils (including Stepney whose mayor was the future Labour leader Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

) threatened similar policies.Shepherd 2002, pp. 200–01 After six weeks' incarceration the councillors were released, and a government conference was convened to resolve the matter. This conference brought a significant personal victory for Lansbury: the passage of the Local Authorities (Financial Provisions) Act, which equalised the poor relief burden across all the London boroughs. As a result, the rates in Poplar fell by a third, and additional revenues of £400,000 was gained by the borough. Lansbury was hailed as a hero; in the 1922 general election he won the parliamentary seat of Bow and Bromley with a majority of nearly 7,000, and would hold it for the rest of his life. The term "Poplarism", always identified closely with Lansbury, became part of the political lexicon, applied generally to campaigns where local government stood against central government on behalf of the poor and least privileged of society.

Parliament and national office

Labour backbencher

In May 1923 the Conservative prime minister,Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a ...

, resigned for health reasons. In December his successor, Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, called another election in which the Conservatives lost their majority, with Labour in a strong second place. King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

advised Baldwin, as leader of the largest party, not to resign his office until defeated by a vote in the House of Commons.

Defeat duly occurred on 21 January 1924, when the Liberals decided to throw in their lot with Labour. The king then asked Labour's leader, Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

, to form a government.Blythe, pp. 278–79 Lansbury caused royal offence by publicly implying that the king had colluded with other parties to keep Labour out, and by his references to the fate of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. Despite his seniority, Lansbury was offered only a junior non-cabinet post in the new government, which he declined.Postgate, pp. 224–25 He believed that his exclusion from the cabinet followed pressure from the king. At the 1923 Labour Party conference, while declaring himself a republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, Lansbury opposed two motions calling for the abolition of the monarchy, deeming the issue a "distraction". Social revolution, he said, would one day remove the monarchy.

MacDonald's administration lasted less than a year before, in November 1924, the Liberals withdrew their support; Blythe comments that the first Labour government had been "neither exhilarating nor competent". According to Shepherd, MacDonald's chief priority was to show that Labour was "fit to govern", and he had thus acted with conservative caution. The December general election returned the Conservatives to power; Lansbury maintained that Labour's cause "marches forward irrespective of electoral results". After the defeat Lansbury was briefly touted as an alternative party leader to MacDonald, a proposition he rejected. In 1925, free from the ''Daily Herald'', he founded and edited ''Lansbury's Labour Weekly'', which became a mouthpiece for his personal creed of socialism, democracy and pacifism until it merged with the ''

MacDonald's administration lasted less than a year before, in November 1924, the Liberals withdrew their support; Blythe comments that the first Labour government had been "neither exhilarating nor competent". According to Shepherd, MacDonald's chief priority was to show that Labour was "fit to govern", and he had thus acted with conservative caution. The December general election returned the Conservatives to power; Lansbury maintained that Labour's cause "marches forward irrespective of electoral results". After the defeat Lansbury was briefly touted as an alternative party leader to MacDonald, a proposition he rejected. In 1925, free from the ''Daily Herald'', he founded and edited ''Lansbury's Labour Weekly'', which became a mouthpiece for his personal creed of socialism, democracy and pacifism until it merged with the ''New Leader

''The New Leader'' (1924–2010) was an American political and cultural magazine.

History

''The New Leader'' began in 1924 under a group of figures associated with the Socialist Party of America, such as Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas. It was p ...

'' in 1927 . Before the General Strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

of May 1926, Lansbury used the ''Weekly'' to instruct the Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre

A national trade union center (or national center or central) is a federation or confederation of trade unions in a country. Nearly every country in the world has a national tra ...

(TUC) on preparations for the coming struggle. However, when the strike came the TUC did not want his assistance; among the reasons for their distrust was Lansbury's continuing advocacy for the right of communist organisations to affiliate to the Labour Party—he privately opined that British communists on their own "couldn't run a whelk-stall".

Lansbury continued his private campaigns in parliament, saying "I intend on every occasion to ... hinder the progress of business". In April 1926 he and 12 other opposition MPs prevented a vote in the House of Commons by obstructing the voting lobbies; they were temporarily suspended by the Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** I ...

. During frequent clashes in the House with Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

, the Minister of Health A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental health.

Coun ...

responsible for Poor Law administration and reform, Lansbury referred to the "Ministry of Death", and called the minister a "pinchbeck Napoleon". However, within the Labour Party itself, Lansbury's status and popularity led to his election as the party's chairman (a largely titular office) in 1927–28. Lansbury also became president of the International League Against Imperialism, where among his fellow executive members were Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

, Mme. Sun Yat-sen and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

. In 1928, short of money following the failure of the family business, Lansbury published his autobiography, ''My Life'', for which he received what he termed "a fairly generous cheque" from the publishers, Constable & Co.

Cabinet minister, 1929–31

In the 1929 general election Labour emerged as the largest party, with 287 seats—but without an overall majority. Once again, MacDonald formed a government dependent on Liberal support. Lansbury joined the new cabinet as

In the 1929 general election Labour emerged as the largest party, with 287 seats—but without an overall majority. Once again, MacDonald formed a government dependent on Liberal support. Lansbury joined the new cabinet as First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequent to 1922, within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irel ...

, with responsibilities for historic buildings and monuments and for the royal parks. This position was widely regarded as a sinecure

A sinecure ( or ; from the Latin , 'without', and , 'care') is an office, carrying a salary or otherwise generating income, that requires or involves little or no responsibility, labour, or active service. The term originated in the medieval chu ...

; nevertheless, Lansbury proved an active minister who did much to improve public recreation facilities. His most notable achievement was the Lido on the Serpentine in Hyde Park; according to the historian A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

"the only thing which keeps the memory of the second Labour government alive". A circular memorial plaque to Lansbury can be seen on the exterior wall of the Lido Bar and Cafe. Lansbury's duties brought him into frequent contact with the King, who as Ranger of the royal parks insisted on regular consultation. Contrary to the expectations of some the two formed a cordial relationship.

The years of MacDonald's second government were dominated by the economic depression that followed the Wall Street Crash

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

of October 1929. Lansbury was appointed to a committee, chaired by J.H. Thomas

James Henry Thomas (3 October 1874 – 21 January 1949), sometimes known as Jimmy Thomas or Jim Thomas, was a Welsh people, Welsh Labour union, trade unionist and Labour Party (UK), Labour (later National Labour Organisation, National Labour) ...

and including Sir Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

, charged with finding a solution to unemployment. Mosley produced a memorandum which called for a large-scale programme of public works; this was rejected by the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, Philip Snowden

Philip Snowden, 1st Viscount Snowden, PC (; 18 July 1864 – 15 May 1937) was a British politician. A strong speaker, he became popular in trade union circles for his denunciation of capitalism as unethical and his promise of a socialist utop ...

, on grounds of cost.Taylor, pp. 404–406 At the end of July 1931 the May Committee, appointed in February to investigate government spending, prescribed heavy cuts, including a massive reduction in unemployment benefit.Taylor, pp. 362–63

During August, in an atmosphere of financial panic and a run on the pound, the government debated the report. MacDonald and Snowden were prepared to implement it, but Lansbury and nine other cabinet ministers rejected the cut in unemployment benefit. Thus divided, the government could not continue; MacDonald, however, did not resign as prime minister. After discussions with the opposition leaders and the king he formed a national all-party coalition, with a "doctor's mandate" to tackle the economic crisis. The great majority of Labour MPs, including Lansbury, were opposed to this action; MacDonald and the few who followed him were expelled from the party, and

During August, in an atmosphere of financial panic and a run on the pound, the government debated the report. MacDonald and Snowden were prepared to implement it, but Lansbury and nine other cabinet ministers rejected the cut in unemployment benefit. Thus divided, the government could not continue; MacDonald, however, did not resign as prime minister. After discussions with the opposition leaders and the king he formed a national all-party coalition, with a "doctor's mandate" to tackle the economic crisis. The great majority of Labour MPs, including Lansbury, were opposed to this action; MacDonald and the few who followed him were expelled from the party, and Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

became leader. MacDonald's move was broadly welcomed in the country, however, and in the general election held in October 1931 the national government was returned with an enormous majority. Labour was reduced to 46 members; Lansbury was the only senior member of the Labour leadership to retain his seat.

Party leader

Although defeated in the election, Henderson remained the party leader while Lansbury headed the Labour group in parliament—theParliamentary Labour Party

In UK politics, the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) is the parliamentary group of the Labour Party in Parliament, i.e. Labour MPs as a collective body. Commentators on the British Constitution sometimes draw a distinction between the Labour P ...

(PLP). In October 1932 Henderson resigned and Lansbury succeeded him.Shepherd 2002, p. 282 In most historians' reckonings, Lansbury led his small parliamentary force with skill and flair. He was also, says Shepherd, an inspiration to the dispirited Labour rank and file.Shepherd 2002, p. 286 As leader he began the process of reforming the party's organisation and machinery, efforts which resulted in considerable by-election and municipal election successes—including control of the LCC under Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

in 1934. According to Blythe, Lansbury "represented political hope and decency to the three million unemployed." During this period Lansbury published his political credo, ''My England'' (1934), which envisioned a future socialist state achieved by a mixture of revolutionary and evolutionary methods.

The small Labour group in parliament had little influence over economic policy; Lansbury's term as leader was dominated by foreign affairs and disarmament, and by policy disagreements within the Labour movement. The official party position was based on collective security through the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

and on multilateral disarmament. Lansbury, supported by many in the PLP, adopted a position of Christian pacifism, unilateral disarmament and the dismantling of the British Empire.Vickers, pp. 107–08 Under his influence the party's 1933 conference passed resolutions calling for the "total disarmament of all nations", and pledged to take no part in war. Pacifism became temporarily popular in the country; on 9 February 1933 the Oxford Union

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to simply as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford England, whose membership is drawn primarily from the University of Oxford. Founded in 1823, it is one of Britain's oldest ...