George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Western Squadron was a new strategy by Britain's naval planners to operate a more effective blockade system of France by stationing the Home Fleet in the Western Approaches, where they could guard both the

The Western Squadron was a new strategy by Britain's naval planners to operate a more effective blockade system of France by stationing the Home Fleet in the Western Approaches, where they could guard both the

From 1765 to 1770, Rodney was governor of Greenwich Hospital, and on the dissolution of parliament in 1768 he successfully contested

From 1765 to 1770, Rodney was governor of Greenwich Hospital, and on the dissolution of parliament in 1768 he successfully contested

After a few months in England, restoring his health and defending himself in Parliament, Sir George returned to his command in February 1782, and a running engagement with the French fleet on 9 April led up to his crowning victory at the

After a few months in England, restoring his health and defending himself in Parliament, Sir George returned to his command in February 1782, and a running engagement with the French fleet on 9 April led up to his crowning victory at the

File:Rodney monument.jpg, Monument of George Brydges Rodney in Memorial in

In February 1783, the government of

Government House ''The Governorship of Newfoundland and Labrador''

*

by Louis Arthur Norton * Chapter III, ''Rodney: The Form'' in , by A. T. Mahan , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Rodney, George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron 1718 births 1792 deaths Burials in Hampshire People educated at Harrow School Peers of Great Britain created by George III Royal Navy personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War Royal Navy admirals Governors of Newfoundland Colony Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Okehampton Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath Royal Navy personnel of the Seven Years' War Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for constituencies in Cornwall British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 British MPs 1761–1768 British MPs 1768–1774 British MPs 1780–1784 History of Îles des Saintes Sea captains George 01 British military personnel of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War Royal Navy personnel of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War People from Walton-on-Thames Military personnel from Surrey

Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney, KB ( bap. 13 February 1718 – 24 May 1792), was a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

officer, politician and colonial administrator. He is best known for his commands in the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, particularly his victory over the French at the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

in 1782. It is often claimed that he was the commander to have pioneered the tactic of breaking the line.

Rodney came from a distinguished but poor background, and went to sea at the age of fourteen. His first major action was the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre

The second battle of Cape Finisterre was a naval battle, naval encounter fought during the War of the Austrian Succession on 25 October 1747 (N.S.). A Royal Navy, British fleet of fourteen ships of the line commanded by Rear admiral (Royal Navy ...

in 1747. He made a large amount of prize

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

money during the 1740s, allowing him to purchase a large country estate and a seat in the House of Commons of Great Britain

The House of Commons of Great Britain was the lower house of the Parliament of Great Britain between 1707 and 1801. In 1707, as a result of the Acts of Union 1707, Acts of Union of that year, it replaced the House of Commons of England and the Pa ...

. During the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, Rodney was involved in a number of amphibious operations such as the raids on Rochefort and Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

and the Siege of Louisbourg. He became well known for his role in the capture of Martinique in 1762. Following the Peace of Paris, Rodney's financial situation stagnated. He spent large sums of money pursuing his political ambitions. By 1774 he had run up large debts and was forced to flee Britain to avoid his creditors. He was in a French jail when war was declared in 1778. Thanks to a French benefactor, Rodney was able to secure his release and return to Britain where he was appointed to a new command.

Rodney successfully relieved Gibraltar during the Great Siege and defeated a Spanish fleet during the 1780 Battle of Cape St. Vincent, known as the "Moonlight Battle" because it took place at night. He then was posted to the Jamaica Station, where he became involved in the controversial 1781 capture of Sint Eustatius. Later that year he briefly returned home suffering from ill health. During his absence the British lost the crucial Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 1 ...

leading to the surrender at Yorktown.

To some, Rodney was a controversial figure, accused of an obsession with prize money. This was brought to a head in the wake of his taking of Saint Eustatius, for which he was heavily criticised in Britain. Orders for his recall had been sent when Rodney won a decisive victory at the Battle of the Saintes in April 1782, ending the French threat to Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

.

Rodney accompanied the future King William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded hi ...

on his visit (April 1783) to Cuba. There the prince conferred with Captain General Luis de Unzaga

Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga (1717–1793), also known as Louis Unzaga y Amezéga le Conciliateur, Luigi de Unzaga Panizza and Lewis de Onzaga, was governor of Spanish Louisiana from late 1769 to mid-1777, as well as a Captain General of Venezuela ...

to reach the preliminaries of peace conditions that would later recognize the birth of the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

. On his return to Britain, Rodney was made a peer and was awarded an annual pension of £2,000. He lived in retirement until his death in 1792.

Early life

George Brydges Rodney was born either inWalton-on-Thames

Walton-on-Thames, known locally as Walton, is a market town on the bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, Thames in northwest Surrey, England. It is in the Borough of Elmbridge, about southwest of central London. Walton forms part ...

or in London, though the family seat was Rodney Stoke, Somerset. He was most likely born sometime in January 1718. He was baptised in St Giles-in-the-Fields on 13 February 1718.Trew, p. 13. He was the third of four surviving children of Henry Rodney and Mary (Newton) Rodney, daughter of Sir Henry Newton. His father had served in Spain under the Earl of Peterborough during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

, and on leaving the army served as captain in a marine corps which was disbanded in 1713. A major investment in the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

ruined Henry Rodney and impoverished the family. In spite of their lack of money, the family was well-connected by marriage. It is sometimes claimed that Henry Rodney had served as commander of the Royal Yacht of George I and it was after him that George was named, but this had been discounted more recently.

George was educated at Harrow School

Harrow School () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English boarding school for boys) in Harrow on the Hill, Greater London, England. The school was founded in 1572 by John Lyon (school founder), John Lyon, a local landowner an ...

, and left as one of the last King's letter boys to join the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, having been appointed, by warrant dated 21 June 1732, a junior officer on board .

Early career

After serving aboard ''Sunderland'', Rodney switched to ''Dreadnought'' where he served from 1734 to 1737 under Captain Henry Medley who acted as a mentor to him. Around this time he spent eighteen months stationed inLisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, a city he would later return to several times. He then changed ships several times, taking part in the navy's annual trip to protect the British fishing fleet off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

in 1738.Trew, p. 14.

He rose swiftly through the ranks of the navy helped by a combination of his own talents and the patronage of the Duke of Chandos

The Dukedom of Chandos was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain, named for a fief in Normandy. The Chandos peerage was first created as a barony by Edward III in 1337; its second creation in 1554 was due to the Brydges family's service to Mar ...

.

While serving on the Mediterranean station

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a military formation, formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vita ...

he was made lieutenant in , his promotion dating 15 February 1739. He then served on ''Namur'', the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the Commander-in-Chief Sir Thomas Mathews.

Captain

TheWar of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession was a European conflict fought between 1740 and 1748, primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italian Peninsula, Italy, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Related conflicts include King Ge ...

had broken out by this point, and in August 1742, Rodney had his first taste of action when he was ordered by Matthews to take a smaller vessel and launch a raid on Ventimiglia

Ventimiglia (; , ; ; ) is a resort town in the province of Imperia, Liguria, northern Italy. It is located west of Genoa, and from the French-Italian border, on the Gulf of Genoa, having a small harbour at the mouth of the Roia river, w ...

, where the Spanish army had stockpiled supplies and stores ready for a planned invasion of Britain's ally the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

, which he successfully accomplished.Trew, p. 15. Shortly after this, he attained the rank of post-captain

Post-captain or post captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of captain in the Royal Navy. The term "post-captain" was descriptive only; it was never used as a title in the form "Post-Captain John Smith".

The term served to dis ...

, having been appointed by Matthews to on 9 November. He picked up several British merchantmen in Lisbon to escort them home, but lost contact with them in heavy storms. Once he reached Britain his promotion was confirmed, making him one of the youngest Captains in the navy.

After serving in home waters learning about convoy protection he was appointed to the newly built ''Ludlow Castle'' which he used to blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

the Scottish coast during the Jacobite Rebellion in 1745. Two of Rodney's midshipman aboard ''Ludlow Castle'' were Samuel Hood, later to become a distinguished sailor, and Rodney's younger brother James Rodney. In 1746 he obtained command of the 60-gun . After some time spent blockading French-occupied Ostend

Ostend ( ; ; ; ) is a coastal city and municipality in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerke, Raversijde, Stene and Zandvoorde, and the city of Ostend proper – the la ...

and cruising around the Western Approaches, where on 24 May he took his first prize a 16-gun Spanish privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

, ''Eagle'' was sent to join the Western Squadron

The Western Squadron was a squadron or formation of the Royal Navy based at Plymouth Dockyard. It operated in waters of the English Channel, the Western Approaches, and the North Atlantic. It defended British trade sea lanes from 1650 to 1814 an ...

.

Battle of Cape Finisterre

The Western Squadron was a new strategy by Britain's naval planners to operate a more effective blockade system of France by stationing the Home Fleet in the Western Approaches, where they could guard both the

The Western Squadron was a new strategy by Britain's naval planners to operate a more effective blockade system of France by stationing the Home Fleet in the Western Approaches, where they could guard both the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

and the French Atlantic coast.

''Eagle'' continued to take prizes while stationed with the Squadron being involved directly, or indirectly, in the capture of sixteen enemy ships. After taking one of the captured prizes to Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork (city), Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a populatio ...

in Ireland, ''Eagle'' was not present at the First Battle of Cape Finisterre when the Western Squadron commanded by Lord Anson won a significant victory over the French. While returning from Ireland, ''Eagle'' fell in with a small squadron under Commodore Thomas Fox which sighted a French merchant convoy heading for the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay ( ) is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Point Penmarc'h to the Spanish border, and along the northern coast of Spain, extending westward ...

. In total around 48 merchantmen were taken by the squadron, although Rodney ignored an order of Fox by pursuing several ships which had broken away from the rest in an attempt to escape managing to capture six of them. Afterwards ''Eagle'' rejoined the Western Squadron now under the command of Edward Hawke.

On 14 October 1747 the ship took part in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre

The second battle of Cape Finisterre was a naval battle, naval encounter fought during the War of the Austrian Succession on 25 October 1747 (N.S.). A Royal Navy, British fleet of fourteen ships of the line commanded by Rear admiral (Royal Navy ...

, a victory off Ushant

Ushant (; , ; , ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and in medieval times, Léon. In lower tiers of government, it is a commune in t ...

over the French fleet. The French were trying to escort an outgoing convoy from France to the West Indies and had eight large ships-of-the-line while the British had fourteen smaller ships. Rodney was at the rear of the British line, and ''Eagle'' was one of the last British ships to come into action engaging the French shortly after noon. Initially ''Eagle'' was engaged with two French ships, but one moved away. Rodney engaged the 70-gun ''Neptune'' for two hours until his steering wheel was struck by a lucky shot, and his ship became unmanageable. Rodney later complained that Thomas Fox in ''Kent'' had failed to support him, and testified at Fox's court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

. The British took six of the eight French ships, but were unable to prevent most of the merchant convoy escaping, although much of it was later taken in the West Indies.

The two Battles of Cape Finisterre had proved a vindication of the Western Squadron strategy. Rodney later often referred to "the good old discipline" of the Western Squadron, using it as an example for his own views on discipline. For the remainder of the war Rodney took part in further cruises, and took several more prizes. Following the Congress of Breda, an agreement was signed at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ending the war. Rodney took his ship back to Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

where it was decommissioned on 13 August 1748. Rodney's total share of prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to ...

during his time with ''Eagle'' was £15,000 giving him financial security for the first time in his life.

Commander

On 9 May 1749 he was appointed governor and commander-in-chief ofNewfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, with the rank of Commodore, it being usual at that time to appoint a naval officer, chiefly on account of the fishery interests. He was given command of and had two smaller ships under his overall command. It was extremely difficult for naval officers to secure commands in peacetime, and Rodney's appointment suggests that he was well regarded by his superiors. Rodney's role as Governor was rather limited. Each summer a large British fishing fleet sailed for Newfoundland, where it took part in the valuable cod

Cod (: cod) is the common name for the demersal fish genus ''Gadus'', belonging to the family (biology), family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gad ...

trade. The fleet then returned home during the winter. Rodney oversaw three such trips to Newfoundland between 1749 and 1751.

Around this time Rodney began to harbour political ambitions and gained the support of the powerful Duke of Bedford

Duke of Bedford (named after Bedford, England) is a title that has been created six times (for five distinct people) in the Peerage of England. The first creation came in 1414 for Henry IV's third son, John, who later served as regent of Fran ...

and Lord Sandwich. He stood unsuccessfully in a 1750 by-election in Launceston. He was elected MP for Saltash, a safe seat controlled by the Admiralty, in 1751. After his third and final trip to Newfoundland in the summer of 1751, Rodney sailed home via Spain and Portugal, escorting some merchantmen. Once home he fell ill, and was then unemployed for around ten months. During this time he oversaw the development of an estate at Old Alresford in Hampshire, which he had bought with the proceeds of his prize money.

From 1753 Rodney commanded a series of Portsmouth guard ships without actually having to go to sea before the onset of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

.

Seven Years' War

The first fighting broke out in North America in 1754, with competing British and French forces clashing in theOhio Country

The Ohio Country (Ohio Territory, Ohio Valley) was a name used for a loosely defined region of colonial North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of Lake Erie.

Control of the territory and the region's fur trade was disputed i ...

. Despite this fighting formal war wasn't declared in Europe until 1756 and opened with a French attack on Minorca, the loss of which was blamed on Admiral John Byng who was court-martialled and executed. He was shot on the quarterdeck of , which until recently had been commanded by Rodney. Rodney excused himself from serving on the court martial by pleading illness. While Rodney disapproved of Byng's conduct, he thought the death sentence excessive and unsuccessfully worked for it to be commuted.

Louisbourg

Rodney had in 1755 and 1756, taken part in preventive cruises under Hawke andEdward Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. He is known principally for his various naval commands during the 18th century and the engagements ...

. In 1757, he took part in the expedition against Rochefort, commanding the 74-gun ship of the line . After an initial success, the expedition made no serious attempt on Rochefort and sailed for home. Next year, in the same ship, he was ordered to serve under Boscawen as part of an attempt to capture the strategic French fortress of Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The harbour had been used by European mariners since at least the 1590s, when it was known as English Port and Havre à l'An ...

in North America. He was given the task of carrying Major General Jeffery Amherst, the expedition's commander to Louisbourg. On the way Rodney captured a French East Indiamen

East Indiamen were merchant ships that operated under charter or licence for European Trading company, trading companies which traded with the East Indies between the 17th and 19th centuries. The term was commonly used to refer to vessels belon ...

, and took it into Vigo

Vigo (, ; ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of province of Pontevedra, Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest ...

. This action saw the beginning of criticism of Rodney that he was obsessed with prize money ahead of strategic importance, with some claiming he spent two weeks or more in Vigo making sure of his prize money instead of carrying Amherst to Louisbourg. This appears to be untrue, as Rodney sailed within four days from Vigo.

Rodney and his ship played a minor role in the taking of Louisburg, which laid the way open for a British campaign up the St Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

the following year, and the fall of Quebec. In August 1758 Rodney sailed for home in charge of six warships and ten transports carrying the captured garrison of Louisbourg who were being taken to Britain as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

.

Le Havre

On 19 May 1759 he became arear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

, and shortly afterwards he was given command of a small squadron.Trew, p. 26. The admiralty had received intelligence that the French had gathered at Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

, at the mouth of the River Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres p ...

, a large number of flat-bottomed boats and stores which were being collected there for an invasion of the British Isles. After drawing up plans for an attack on Le Havre, Lord Anson briefed Rodney in person. The operation was intended to be a secret with it being implied that Rodney's actual destination was Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

. This soon became impossible to maintain as Rodney tried to acquire pilots who knew the Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

coast.

Rodney received his final orders on 26 June, and by 4 July he was off Le Havre. His force included six bomb-vessels which could fire at a very high trajectory. In what become known as the Raid on Le Havre, he bombarded the town for two days and nights, and inflicted great loss of war-material on the enemy. The bomb ships fired continuously for fifty two hours, starting large fires. Rodney then withdrew to Spithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

, leaving several ships to blockade the mouth of the Seine. Although the attack hadn't significantly affected French plans, it proved a morale boost in Britain. In August Rodney was again sent to Le Havre with similar orders but through a combination of weather and improved French defences he was unable to get his bomb-vessels into position, and the Admiralty accepted his judgement that a further attack was impossible. The invasion was ultimately cancelled because of French naval defeats at the Battle of Lagos and Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as the ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' by the French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off ...

.

From 1759 and 1761 Rodney concentrated on his blockade of the French coast, particularly around Le Havre. In July 1760, with another small squadron, he succeeded in taking many more of the enemy's flat-bottomed boats and in blockading the coast as far as Dieppe

Dieppe (; ; or Old Norse ) is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department, Normandy, northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newhaven in England ...

.

Martinique

Rodney was elected MP for Penryn in 1761. Lord Anson then selected him to command the naval element of a planned amphibious attack on the lucrative and strategically important French colony ofMartinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, Kariʼn ...

in the West Indies, promoting him over the heads of a number of more senior officers. A previous British attack on Martinique had failed in 1759. The land forces for the attack on Martinique were to be a combination of troops from various locations including some sent out from Europe and reinforcements from New York City, who were available following the Conquest of Canada which had been completed in 1760. During 1761 Martinique was blockaded by Sir James Douglas to prevent reinforcements or supplies from reaching it. In 1762 he was formally appointed commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands Station.

Within the first three months of 1762, Monckton and he had reduced the important island of Martinique, while both Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. Part of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, it is located north/northeast of the island of Saint Vincent (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), Saint Vincent ...

and Grenada

Grenada is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about north of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and the So ...

had surrendered to his squadron. During the siege of Fort Royal (later Fort de France) his seamen and marines rendered splendid service on shore. Afterwards Rodney's squadron, amounting to eight ships of the line joined the British expedition to Cuba bringing the total number of ships of the line to 15 by the end of April 1762. However he was later criticised for moving his ships to protect Jamaica from attack by a large Franco-Spanish force that had gathered in the area, rather than waiting to support the expedition as he had been ordered.

Following the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Admiral Rodney returned home having been during his absence made Vice-Admiral of the Blue and having received the thanks of both Houses of Parliament. In the peace terms Martinique was returned to France.

Years of peace

From 1765 to 1770, Rodney was governor of Greenwich Hospital, and on the dissolution of parliament in 1768 he successfully contested

From 1765 to 1770, Rodney was governor of Greenwich Hospital, and on the dissolution of parliament in 1768 he successfully contested Northampton

Northampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England. It is the county town of Northamptonshire and the administrative centre of the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of West Northamptonshire. The town is sit ...

and was elected to parliament, but at a ruinous cost. When appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Jamaica Station in 1771, he lost his Greenwich post, but a few months later received the office of Rear-Admiral of Great Britain. Until 1774, he held the Jamaica command, and during a period of quiet, was active in improving the naval yards on his station. Sir George struck his flag with a feeling of disappointment at not obtaining the governorship of Jamaica, and was shortly after forced to settle in Paris. Election expenses and losses at play in fashionable circles had shattered his fortune, and he could not secure payment of the salary as Rear-Admiral of Great Britain. In February 1778, having just been promoted Admiral of the White, he used every possible exertion to obtain a command to free himself from his money difficulties. By May, he had, through the splendid generosity of his Parisian friend Marshal Biron, effected the latter task, and accordingly he returned to London with his children. The debt was repaid out of the arrears due to him on his return. The story that he was offered a French command is fiction.

American War of Independence

In London, he suggested to Lord George Germain thatGeorge Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

could "certainly be bought – honours

Honour (Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself as a code of conduct, and has various elements such as valo ...

will do it".

Moonlight Battle

Rodney was appointed once more commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands Station late in 1779. His orders were to relieve Gibraltar on his way to the West Indies. He captured a Spanish convoy of 22 vessels off Cape Finisterre on 8 January 1780. Eight days later at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent he defeated the Spanish Admiral Don Juan de Lángara, taking or destroying seven ships. He then brought some relief to Gibraltar by delivering reinforcements and supplies.Battle of Martinique

On 17 April he fought an action off Martinique with the French Admiral Guichen which, owing to the carelessness of some of Rodney's captains, was indecisive.Capture of St Eustatius

Following the outbreak of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War between Britain and theDutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

Rodney, acting under orders from London, captured the valuable Dutch island of St Eustatius on 3 February 1781. Rodney had already identified several individuals on the island who were aiding the Americans, such as "... Mr Smith at the House of Jones – they (the Jews of St. Eustatius, Caribbean Antilles) cannot be too soon taken care of – they are notorious in the cause of America and France..." The island was also home to a Jewish community who were mainly merchants with significant international trading and maritime commercial ties. The Jews were estimated to have been at least 10% of the permanent population of St. Eustatius.

Rodney immediately arrested and imprisoned 101 Jews in the warehouses of the lower city. He summarily deported 31 adult Jews to the island of Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially Saint Christopher, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis constitute one ...

. Rodney looted Jewish personal possessions and even tore out the linings of the clothes of his captives in search of hidden valuables; this alone yielded him 8,000 pounds. When Rodney realised that the Jews might be hiding additional treasure, he dug up their local cemetery.

Even large quantities of non-military trading goods belonging to British merchants on the island were arbitrarily confiscated. This resulted in Rodney being entangled in a series of costly lawsuits for the rest of his life. Still, the wealth Rodney acquired on St. Eustatius exceeded his expectations.

Controversy and Yorktown

Rodney wrote to his family with promises of a new London home; to his daughter "the bestharpsichord

A harpsichord is a musical instrument played by means of a musical keyboard, keyboard. Depressing a key raises its back end within the instrument, which in turn raises a mechanism with a small plectrum made from quill or plastic that plucks one ...

money can purchase". He confidently wrote of a marriage settlement for one of his sons and a soon-to-be purchased commission in the Foot Guards for another son. Rodney also wrote of a dowry

A dowry is a payment such as land, property, money, livestock, or a commercial asset that is paid by the bride's (woman's) family to the groom (man) or his family at the time of marriage.

Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price ...

for his daughter to marry the Earl of Oxford

Earl of Oxford is a dormant title in the Peerage of England, first created for Aubrey de Vere, 1st Earl of Oxford, Aubrey de Vere by the Empress Matilda in 1141. De Vere family, His family was to hold the title for more than five and a half cen ...

and noted he would have enough to pay off the young prospective bridegroom's debts.

Other Royal Navy officers scathingly criticised Rodney for his actions. In particular, Viscount Samuel Hood suggested that Rodney should have sailed to intercept a French fleet under Rear Admiral Francois Joseph Paul de Grasse, travelling to Martinique. The French fleet instead turned north and headed for the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

.

Rodney's delay at St. Eustatius was not the first time he had taken the opportunity to capture prizes over the immediate and expeditious fulfillment of his military duties. During the Seven Years' War Rodney had been ordered to Barbados to link up with Admiral Sir George Pocock and the Earl of Albemarle for an attack on Cuba. Instead, Rodney sent valuable ships off in search of prizes. In 1762, Rodney, after the fall of Martinique, quarreled with the army over prize money. During Rodney's command in Jamaica, 1771–1774, the Earl of Sandwich feared that Rodney might provoke a war with Spain to obtain prize money.

Plundering the wealth of St. Eustatius and capturing many prizes over a number of months, Rodney further weakened his fleet by sending two ships-of-the-line to escort his treasure ships to England, though both were in need of major repair. Nevertheless, he is both blamed and defended for the subsequent disaster at Yorktown. His orders as naval commander in chief in the eastern Caribbean were not only to watch de Grasse but also to protect the valuable sugar trade. Rodney had received intelligence earlier that de Grasse would send part of his fleet before the start of the hurricane season to relieve the French squadron at Newport and to co-operate with Washington, returning in the fall to the Caribbean. The other half of de Grasse's fleet, as usual, would escort the French merchantmen back across the Atlantic. Rodney accordingly made his dispositions in the light of this intelligence. Sixteen of his remaining twenty-one warships would go with Hood to reinforce the squadron at New York under Sir Thomas Graves, while Rodney, who was in ill health, returned to England with three other warships as merchant escorts, leaving two others in dock for repair. Hood was well satisfied with these arrangements, informing a colleague that his fleet was "fully equal to defeat any designs of the enemy." What Rodney and Hood could not know was that at the last moment de Grasse decided to take his entire fleet to North America, leaving the French merchantmen to the protection of the Spanish. The result was a decisive French superiority in warships during the subsequent naval campaign, when the combined fleets of Hood and Graves were unable to relieve the British army of Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best known as one of the leading Britis ...

, who was then establishing a base on the York River. This left Cornwallis no option but to surrender, resulting a year later in British recognition of American Independence. Although Rodney's actions at St. Eustatius and afterwards contributed to the British naval inferiority in the Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 1 ...

, the real reason for the disaster at Yorktown was the inability of Britain to match the resources of the other naval powers of Europe.

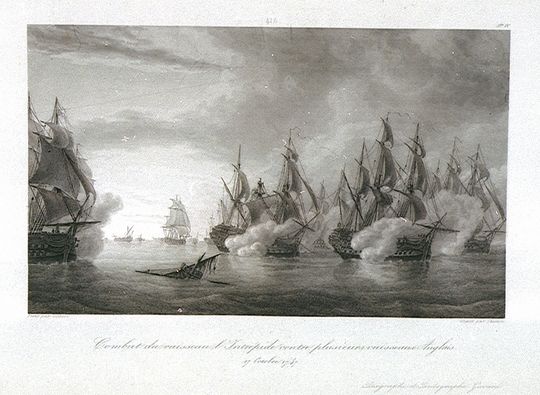

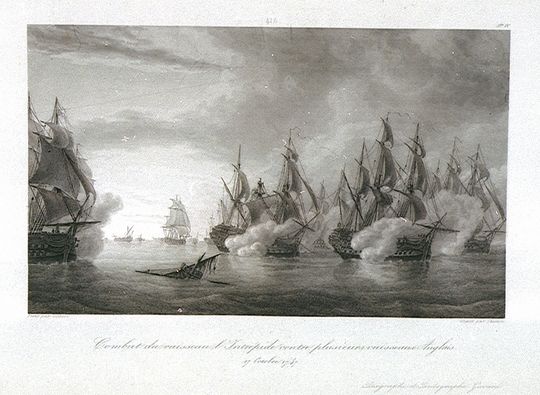

Battle of the Saintes

Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

off Dominica, when on 12 April with thirty-five sail of the line he defeated the Comte de Grasse, who had thirty-three sail. The French inferiority in numbers was more than counterbalanced by the greater size and superior sailing qualities of their ships, yet four French ships of the line were captured (including the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

) as well as one destroyed after eleven hours' fighting.

This important battle saved Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

and ruined French naval prestige, while it enabled Rodney to write: "Within two little years I have taken two Spanish, one French and one Dutch admirals." A long and wearisome controversy exists as to the originator of the manoeuvre of "breaking the line" in this battle, but the merits of the victory have never seriously been affected by any difference of opinion on the question. A shift of wind broke the French line of battle, and the British ships took advantage of this by crossing in two places; many were taken prisoner including the Comte de Grasse.

From 29 April to 10 July he sat with his fleet at Port Royal, Jamaica while his fleet was repaired after the battle.

Recall

In a 15 April letter to Lord George Germain, who unknown to Rodney had recently lost his position, he wrote "Permit me most sincerely to congratulate you on the most important victory I believe ever gained against our perfidious enemies, the French". The news of Rodney's victories reached England on 18 May 1782 via HMS ''Andromache'' and boosted national morale in Britain and strengthened the pro-war party, who wished to carry on the fight. George III observed to the new Prime MinisterLord Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (2 May 17377 May 1805), known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history, was an Anglo-Irish Whig statesman who was the first home secr ...

that he "must see that the great success of Lord Rodney's engagement has so far roused the nation, that the peace which would have been acquiesced in three months ago would now be a matter for complaint".

Rodney was preparing to sail to meet the enemy off Cape Haitien when arrived from England, not only relieving him of duty, but also bringing his replacement: Admiral Hugh Pigot. This bizarre exchange was largely the result of changing politics in Britain: Rodney was a Tory placed in charge of the fleet by a Tory government... but the Whigs were now in power. That said, at 64 years of age, he was perhaps due for retirement. However, Pigot and the command to retire was dispatched on 15 May, three days before the news of the victory at the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

reached the Admiralty. A cutter sent by the Admiralty on 19 May failed to catch the ''Jupiter'' so Rodney's fate was sealed.

Rodney quietly quit his quarters on the ''Formidable'' and returned to England in more modest quarters on .

Later life

Nepotism and self-interest

Rodney was unquestionably a most able officer, but he was also vain, selfish and unscrupulous, both in seeking prize money, and in using his position to push the fortunes of his family, although such nepotism was common (not to say normal) at the time. He made his son a post-captain at fifteen, and his assiduous self-interest alienated his fellow officers and the Board of Admiralty alike. Naval historian Nicholas A. M. Rodger describes Rodney as possessing weaknesses with respect to patronage "which destroyed the basis of trust upon which alone an officer can command." It must be remembered that he was then prematurely old and racked by disease.Retirement

Rodney arrived home in August to receive unbounded honour from his country. He had already been created Baron Rodney of Rodney Stoke, Somerset, by patent of 19 June 1782, and the House of Commons had voted him a pension of £2000 a year. From this time he led a quiet country life until his death in London. He was succeeded as 2nd Baron by his son, George (1753–1802). In 1782 Rodney was presented with the Freedom of the City of Cork, Ireland. TheNational Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the Unit ...

, Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, London, holds the gold presentation box that the City of Cork gave him on 16 September 1782.Personal life

In 1753 Rodney married firstly Jane Compton (1730–1757), one of the sisters of Charles Compton, 7th Earl of Northampton. He had initially been undecided whether to marry Jane or her younger sister Kitty, whom he had met in Lisbon during his visits to the city, where their father Charles Compton was consul. The marriage proved happy, and they had two sons together before she died in January 1757: *George Rodney, later 2nd Baron Rodney (25 December 1753 – 2 January 1802) *Captain the Hon. James Rodney RN, lost at sea in 1776 In 1764, Rodney was created abaronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

, and the same year married secondly Henrietta, daughter of John Clies, a merchant of Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

. With her he had further two sons and three daughters:Patrick Cracroft-Brennan, ed., "Rodney, Baron (GB, 1782)", ''Cracroft's Peerage'' (December 2002, ), online edition

*Captain John Rodney RN (1765–1847), later Chief Secretary to the Government of Ceylon, who married firstly Lady Catherine Nugent, only daughter of Thomas Nugent, 6th Earl of Westmeath, secondly Lady Louisa Martha Stratford, daughter and coheiress of John Stratford, 3rd Earl of Aldborough

John Stratford, 3rd Earl of Aldborough (–1823), was an Irish peer and member of the House of Stratford. He was known as Hon. John Stratford until 1801 when he inherited the Earldom from his brother Edward Stratford, 2nd Earl of Aldborough.

...

, and thirdly Antoinette Reyne, only daughter of Anthony Pierre Reyne, having children by all three wives; his daughter Catherine Henrietta Rodney married Patrick Stuart, later Governor of Malta, and their daughter Jane Frances Stuart married Admiral George Grey.

*Jane Rodney (born c. 1766), who in 1784 married George Chambers

The Hon. George Michael Chambers ORTT (4 October 1928 – 4 November 1997)

; they had nine children;

*Sarah Brydges Rodney (1780–1871), who in 1801 married General Godfrey Basil Meynell Mundy and had children

*Captain Edward Rodney RN (1783–1828), who married Rebecca Geer, with children;

*Margaret Anne Rodney (died 1858)

Rodney died in 1792 and was buried in the church of St Mary the Virgin, Old Alresford, Hampshire, which adjoins his family seat. There is also a memorial to him within St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

.

Legacy

Spanish Town

Spanish Town (Jamaican Patois: Spain) is the capital and the largest town in the Parishes of Jamaica, parish of St. Catherine, Jamaica, St. Catherine in the historic county of Middlesex, Jamaica, Middlesex, Jamaica. It was the Spanish and Briti ...

File:Rodney monument, St Paul's Cathedral.jpg, Memorial in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, London

File:Breiddin02LB.jpg, Rodney's Pillar on Breidden Hill in Wales

File:Admiral Rodney public house, Long Buckby.jpg, Admiral Rodney public house, Long Buckby

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

commissioned John Bacon, a renowned British sculptor, to create a statue of Admiral Lord Rodney, as an expression of their appreciation. The Assembly spent $5,200 on the statue alone and a reputed $31,000 on the entire project. Bacon sourced the finest marble from Italy to create the Neo-classical sculpture of the Admiral, dressed in a Roman robe and breastplate. On its completion, the statue was fronted with cannons taken from the French flagship, Ville de Paris, in the battle. The truly huge monument, known as the Rodney Temple stands in Spanish Town, Jamaica

Spanish Town (Jamaican Patois: Spain) is the capital and the largest town in the Parishes of Jamaica, parish of St. Catherine, Jamaica, St. Catherine in the historic county of Middlesex, Jamaica, Middlesex, Jamaica. It was the Spanish and Briti ...

, next to the Governor's House.

In late 1782 and early 1783 a large number of existing taverns renamed themselves "The Admiral Rodney" in admiration of the victory.

Admiral Rodney's Pillar was constructed on the peak of Breidden Hill to commemorate his victories.

In St. Paul's Cathedral crypt, there is a memorial to Rodney designed by Charles Rossi.

At least four serving warships of the Royal Navy have been named in his honour.

Two British public schools, Churcher's College and Emanuel School

Emanuel School is a private, co-educational day school in Battersea, south-west London. The school was founded in 1594 by Anne Sackville, Lady Dacre and Queen Elizabeth I and today occupies a 12-acre (4.9 ha) site close to Clapham Junction ...

, have houses

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

named after him.

Due to his popularity with citizens of Newfoundland as governor, small round-bottomed wooden boats, propelled by oars and/or sails, are often referred to as a "Rodney" up to the present day in Newfoundland.

In 1793, following Rodney's death, Scotland's Bard, the poet Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

(1759–1796), published a poem "Lines On The Commemoration Of Rodney's Victory" commemorating the Battle of the Saintes

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9–12 April 1782. The Brit ...

. The poem opens with the lines:

:"Instead of a Song, boy's, I'll give you a Toast;

:"Here's to the memory of those on the twelfth that we lost!-

:"That we lost, did I say?-nay, by Heav'n, that we found;

:"For their fame it will last while the world goes round. “

Places named after Rodney

* Rodney Street, Liverpool * Rodney Street, Edinburgh * Rodney Bay,Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. Part of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, it is located north/northeast of the island of Saint Vincent (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), Saint Vincent ...

, the Caribbean

* Rodney County, New Zealand

* Rodney Gardens, Perth, Scotland

* Cape Rodney, North Island

The North Island ( , 'the fish of Māui', historically New Ulster) is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but less populous South Island by Cook Strait. With an area of , it is the List ...

, New Zealand

* Rodney, Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

* Admiral Rodney – Pub, Worcestershire

* Admiral Rodney - Pub, Criggion Lane, Powys

* Admiral Lord Rodney - Pub, Colne, Lancashire

* Admiral Rodney - Hotel, Horncastle, Lincolnshire

* Admiral Rodney - Pub, Sheffield

* Rodney Inn - Pub, Helston, Cornwall

* The Admiral Rodney Inn - Criggion, Powys (in sight of Rodney's Pillar monument on Breidden Hill)

* The Admiral Rodney Inn - Pub, Hartshorne, Swadlincote, Derbyshire.

* The Admiral Rodney - Pub, Prestbury, Cheshire

* The Lord Rodney - Pub, Keighley, West Yorkshire

* The Admiral Rodney - Pub, Calverton, Nottinghamshire

* The Rodney Hotel - Hotel, Clifton, Bristol

* Admiral Rodney - Pub, Wollaton, Nottinghamshire

References

Bibliography

* * ''The Naval Chronicle, Volume 1'' 1799, J. Gold, London. (reissued byCambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, 2010.

*

* Fleming, Thomas. ''The Perils of Peace: America's Struggle for Survival After Yorktown''. First Smithsonian books, 2008.

* Hannay, David. ''Life of Rodney''. Macmillan, 1891.

* Hibbert, Christopher. ''Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution Through British Eyes''. Avon Books, 1990.

* General Mundy, ''Life and Correspondence of Admiral Lord Rodney'' (2 vols, 1830)

* O'Shaunhassey, Andrew Jackson. ''The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of Empire''. Yale University Press, 2013.

* Rodger, N. A. M. ''Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815''. Penguin Books, 2006.

* Spinney, David. ''Rodney'', George Allen & Unwin, 1969.

* Stewart, William. ''Admirals of the World: A Biographical Dictionary 1500 to the Present''. McFarland, 2009.

* Trew, Peter. ''Rodney and the Breaking of the Line''. Pen and Sword, 2006.

* Weintraub, Stanley. ''Iron Tears: Rebellion in America, 1775–1783''. Simon & Schuster, 2005.

* Rodney letters in ''9th Report of Hist. manuscripts Coin.'', pt. iiL; "Memoirs," in ''Naval Chronicle'', i. 353–93; and Charnock, ''Biographia Navalis'', v. 204–28. Lord Rodney published in his lifetime (probably 1789)

* ''Letters to His Majesty's Ministers'', etc., relative to St Eustatius, etc., of which there is a copy in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

. Most of these letters are printed in Mundy's ''Life'', vol. ii., though with many variant readings.

Further reading

* Arbell, Mordechai. ''The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean, The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas'' (2002) Geffen Press, Jerusalem * Bernardini, P. & Fiering, N. (editors). ''The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450–1800'' (2001), Berghan Press * Charnock, John. ''Biographia Navalis'' volume, 5 pg 204–228. 1797, London. * Ezratty, Harry. ''500 Years in the Jewish Caribbean – The Spanish and Portuguese Jews in the West Indies'' (1997) Omni Arts, Baltimore * Macintyre, Donald. ''Admiral Rodney'' (1962) Peter Davies, London. * Middleton, Richard. ''The War of American Independence, 1775–1783''. Pearson. London, 2012 * Mundy, Godfrey Basil. ''Life and Correspondence of Admiral Lord Rodney, Vols 1 and 2'' 1830 * Syrett, David. ''The Rodney Papers: selections from the correspondence of Admiral Lord Rodney'' 2007, Ashgate Publishing Ltd * Hartog, J. ''History of St. Eustatius'' (1976) Central USA Bicentennial Committee of the Netherlands Antilles * Attema, Y. ''A Short History of St. Eustatius and its Monuments'' (1976) Wahlberg PersExternal links

Government House ''The Governorship of Newfoundland and Labrador''

*

by Louis Arthur Norton * Chapter III, ''Rodney: The Form'' in , by A. T. Mahan , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Rodney, George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron 1718 births 1792 deaths Burials in Hampshire People educated at Harrow School Peers of Great Britain created by George III Royal Navy personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession Royal Navy personnel of the American Revolutionary War Royal Navy admirals Governors of Newfoundland Colony Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Okehampton Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath Royal Navy personnel of the Seven Years' War Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for constituencies in Cornwall British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 British MPs 1761–1768 British MPs 1768–1774 British MPs 1780–1784 History of Îles des Saintes Sea captains George 01 British military personnel of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War Royal Navy personnel of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War People from Walton-on-Thames Military personnel from Surrey