Genomic Integration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dimensional structural configuration. In contrast to genetics, which refers to the study of ''individual'' genes and their roles in inheritance, genomics aims at the collective characterization and quantification of ''all'' of an organism's genes, their interrelations and influence on the organism. Genes may direct the production of

Most of the microorganisms whose genomes have been completely sequenced are problematic pathogens, such as '' Haemophilus influenzae'', which has resulted in a pronounced bias in their phylogenetic distribution compared to the breadth of microbial diversity. Of the other sequenced species, most were chosen because they were well-studied model organisms or promised to become good models. Yeast ('' Saccharomyces cerevisiae'') has long been an important

Most of the microorganisms whose genomes have been completely sequenced are problematic pathogens, such as '' Haemophilus influenzae'', which has resulted in a pronounced bias in their phylogenetic distribution compared to the breadth of microbial diversity. Of the other sequenced species, most were chosen because they were well-studied model organisms or promised to become good models. Yeast ('' Saccharomyces cerevisiae'') has long been an important

The

The

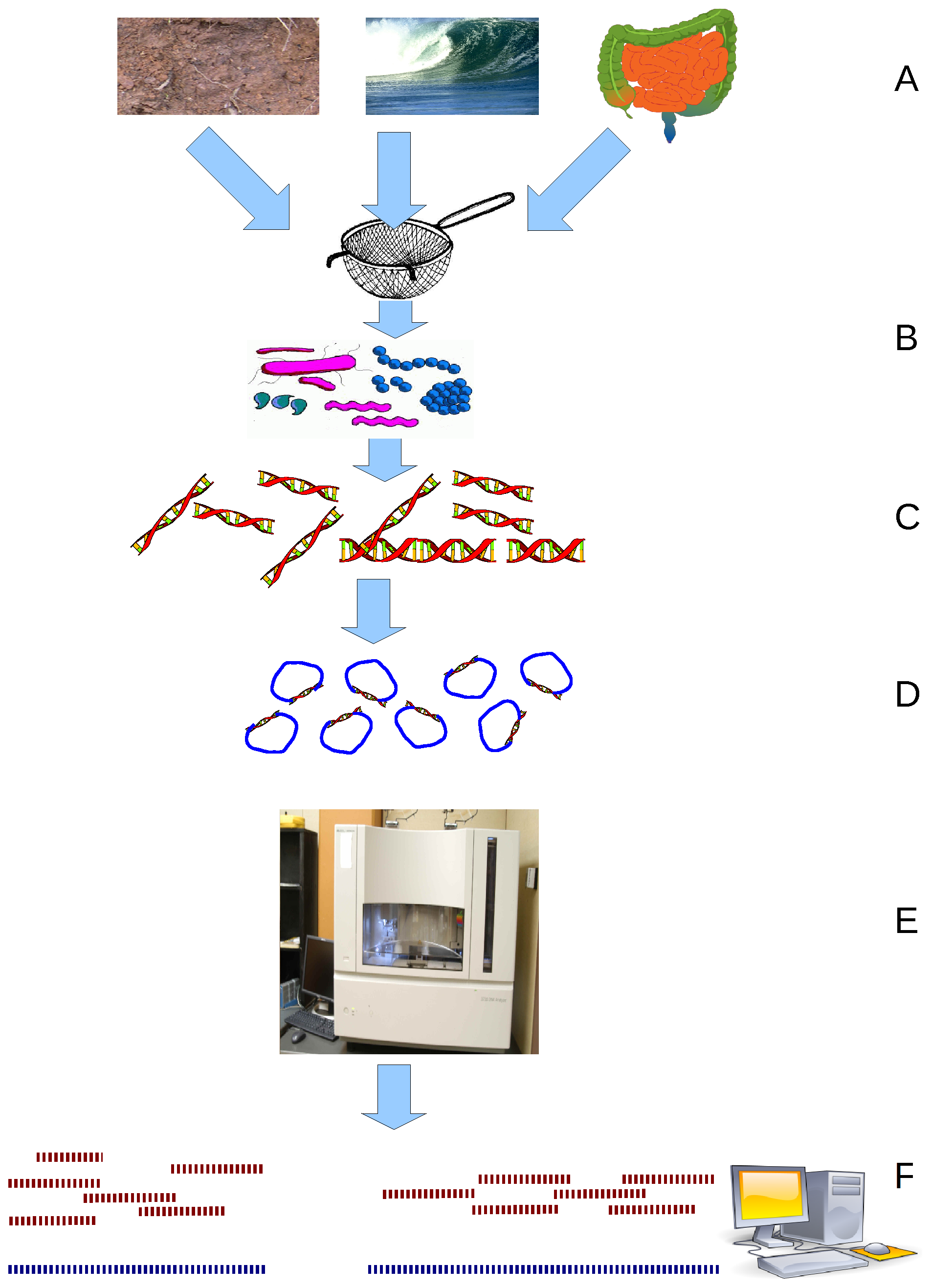

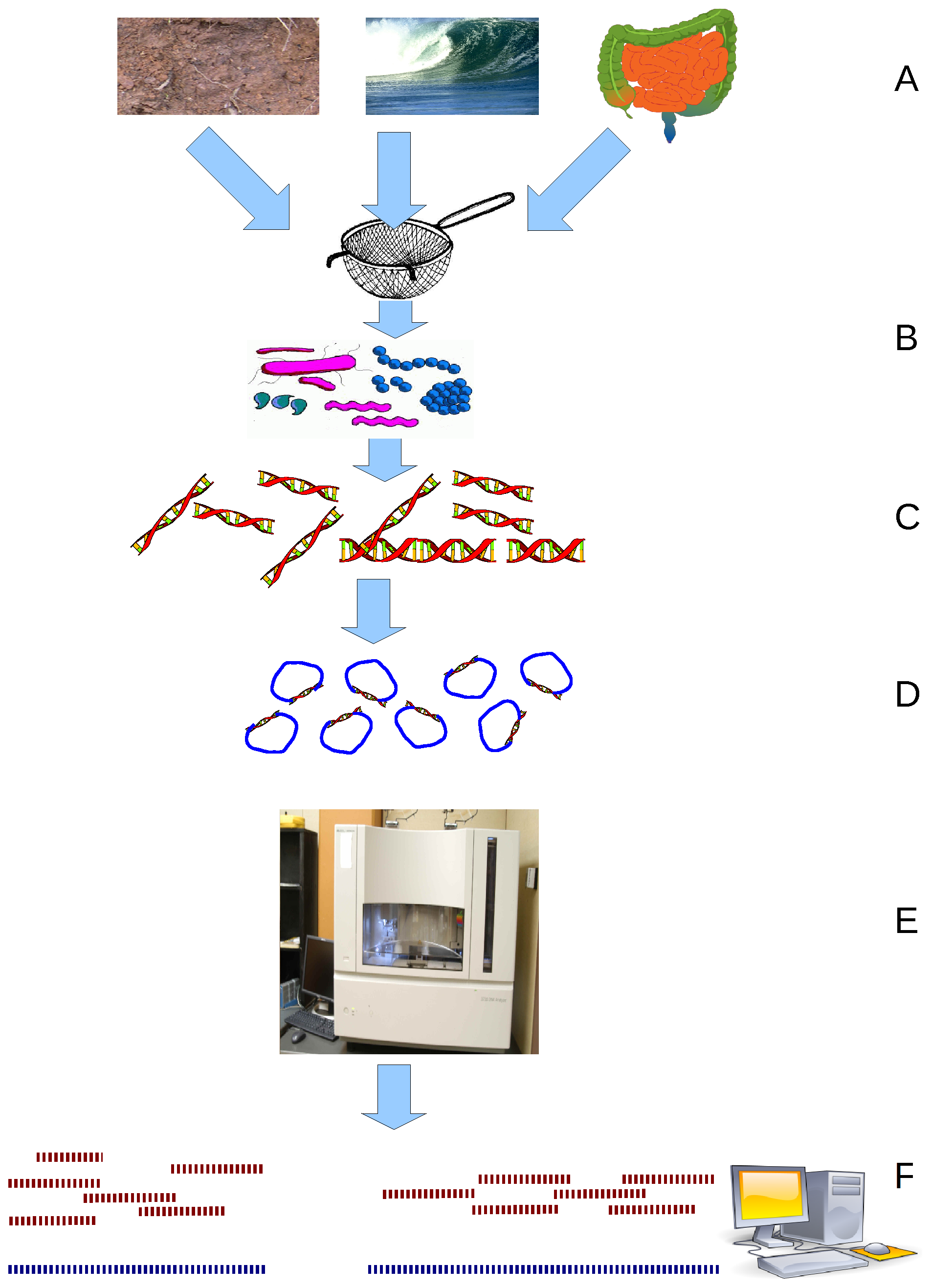

Metagenomics is the study of ''metagenomes'', genetic material recovered directly from

Metagenomics is the study of ''metagenomes'', genetic material recovered directly from

Genomics has provided applications in many fields, including medicine, biotechnology, anthropology and other social sciences.

Genomics has provided applications in many fields, including medicine, biotechnology, anthropology and other social sciences.

Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics

BMC Genomics

A BMC journal on Genomics

Genomics journal

Genomics.org

An openfree genomics portal.

NHGRI

US government's genome institute

JCVI Comprehensive Microbial Resource

KoreaGenome.org

The first Korean Genome published and the sequence is available freely.

GenomicsNetwork

Looks at the development and use of the science and technologies of genomics.

Institute for Genome Sciences

Genomics research.

MIT OpenCourseWare HST.512 Genomic Medicine

A free, self-study course in genomic medicine. Resources include audio lectures and selected lecture notes.

ENCODE threads explorer

Machine learning approaches to genomics. Nature (journal)

Global map of genomics laboratories

Genomics: Scitable by nature education

Learn All About Genetics Online

{{Authority control

proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

with the assistance of enzymes and messenger molecules. In turn, proteins make up body structures such as organs and tissues as well as control chemical reactions and carry signals between cells. Genomics also involves the sequencing and analysis of genomes through uses of high throughput DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

and bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combi ...

to assemble and analyze the function and structure of entire genomes. Advances in genomics have triggered a revolution in discovery-based research and systems biology

Systems biology is the computational modeling, computational and mathematical analysis and modeling of complex biological systems. It is a biology-based interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on complex interactions within biological syst ...

to facilitate understanding of even the most complex biological systems such as the brain.

The field also includes studies of intragenomic (within the genome) phenomena such as epistasis

Epistasis is a phenomenon in genetics in which the effect of a gene mutation is dependent on the presence or absence of mutations in one or more other genes, respectively termed modifier genes. In other words, the effect of the mutation is dep ...

(effect of one gene on another), pleiotropy

Pleiotropy (from Greek , 'more', and , 'way') occurs when one gene influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Such a gene that exhibits multiple phenotypic expression is called a pleiotropic gene. Mutation in a pleiotropic g ...

(one gene affecting more than one trait), heterosis (hybrid vigour), and other interactions between loci and alleles within the genome.

History

Etymology

From the Greek ΓΕΝ ''gen'', "gene" (gamma, epsilon, nu, epsilon) meaning "become, create, creation, birth", and subsequent variants: genealogy, genesis, genetics, genic, genomere, genotype, genus etc. While the word ''genome'' (from theGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

''Genom'', attributed to Hans Winkler

Hans Karl Albert Winkler (23 April 1877 – 22 November 1945) was a German botanist. He was Professor of Botany at the University of Hamburg, and a director of that university's Institute of Botany. Winkler coined the term 'heteroploidy' in 191 ...

) was in use in English as early as 1926, the term ''genomics'' was coined by Tom Roderick, a geneticist at the Jackson Laboratory

The Jackson Laboratory (often abbreviated as JAX) is an independent, non-profit biomedical research institution which was founded by a eugenicist. It employs more than 3,000 employees in Bar Harbor, Maine; Sacramento, California; Farmington, Con ...

(Bar Harbor, Maine

Bar Harbor is a resort town on Mount Desert Island in Hancock County, Maine, United States. As of the 2020 census, its population is 5,089. During the summer and fall seasons, it is a popular tourist destination and, until a catastrophic fire i ...

), over beers with Jim Womack, Tom Shows and Stephen O’Brien at a meeting held in Maryland on the mapping of the human genome in 1986. First as the name for a new journal and then as a whole new science discipline.

Early sequencing efforts

FollowingRosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, co ...

's confirmation of the helical structure of DNA, James D. Watson and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

's publication of the structure of DNA in 1953 and Fred Sanger's publication of the Amino acid sequence of insulin in 1955, nucleic acid sequencing became a major target of early molecular biologists

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

. In 1964, Robert W. Holley

Robert William Holley (January 28, 1922 – February 11, 1993) was an American biochemist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1968 (with Har Gobind Khorana and Marshall Warren Nirenberg) for describing the structure of alani ...

and colleagues published the first nucleic acid sequence ever determined, the ribonucleotide

In biochemistry, a ribonucleotide is a nucleotide containing ribose as its pentose component. It is considered a molecular precursor of nucleic acids. Nucleotides are the basic building blocks of DNA and RNA. Ribonucleotides themselves are basic m ...

sequence of alanine transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

. Extending this work, Marshall Nirenberg and Philip Leder revealed the triplet nature of the genetic code and were able to determine the sequences of 54 out of 64 codons

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

in their experiments. In 1972, Walter Fiers and his team at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of the University of Ghent ( Ghent, Belgium) were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: the gene for Bacteriophage MS2

Bacteriophage MS2 (''Emesvirus zinderi''), commonly called MS2, is an icosahedral, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that infects the bacterium ''Escherichia coli'' and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae. MS2 is a member of a family ...

coat protein. Fiers' group expanded on their MS2 coat protein work, determining the complete nucleotide-sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA (whose genome encodes just four genes in 3569 base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s [bp]) and Simian virus 40

SV40 is an abbreviation for simian vacuolating virus 40 or simian virus 40, a polyomavirus that is found in both monkeys and humans. Like other polyomaviruses, SV40 is a DNA virus that has the potential to cause tumors in animals, but most often ...

in 1976 and 1978, respectively.

DNA-sequencing technology developed

In addition to his seminal work on the amino acid sequence of insulin,Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other p ...

and his colleagues played a key role in the development of DNA sequencing techniques that enabled the establishment of comprehensive genome sequencing projects. In 1975, he and Alan Coulson published a sequencing procedure using DNA polymerase with radiolabelled nucleotides that he called the ''Plus and Minus technique''. This involved two closely related methods that generated short oligonucleotides with defined 3' termini. These could be fractionated by electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric fie ...

on a polyacrylamide gel (called polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and visualised using autoradiography. The procedure could sequence up to 80 nucleotides in one go and was a big improvement, but was still very laborious. Nevertheless, in 1977 his group was able to sequence most of the 5,386 nucleotides of the single-stranded bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

φX174, completing the first fully sequenced DNA-based genome. The refinement of the ''Plus and Minus'' method resulted in the chain-termination, or Sanger method

Sanger sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing that involves electrophoresis and is based on the random incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication. After first being developed by Frederi ...

(see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

), which formed the basis of the techniques of DNA sequencing, genome mapping, data storage, and bioinformatic analysis most widely used in the following quarter-century of research. In the same year Walter Gilbert and Allan Maxam

Allan Maxam (born October 28, 1942) is one of the pioneers of molecular genetics. He was one of the contributors to develop a DNA sequencing method at Harvard University, while working as a student in the laboratory of Walter Gilbert.

Walter Gi ...

of Harvard University independently developed the Maxam-Gilbert method (also known as the ''chemical method'') of DNA sequencing, involving the preferential cleavage of DNA at known bases, a less efficient method. For their groundbreaking work in the sequencing of nucleic acids, Gilbert and Sanger shared half the 1980 Nobel Prize in chemistry with Paul Berg ( recombinant DNA).

Complete genomes

The advent of these technologies resulted in a rapid intensification in the scope and speed of completion of genome sequencing projects. The first complete genome sequence of aeukaryotic organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

, the human mitochondrion

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used ...

(16,568 bp, about 16.6 kb [kilobase]), was reported in 1981, and the first chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

genomes followed in 1986. In 1992, the first eukaryotic chromosome, chromosome III of brewer's yeast '' Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' (315 kb) was sequenced. The first free-living organism to be sequenced was that of '' Haemophilus influenzae'' (1.8 Mb [megabase]) in 1995. The following year a consortium of researchers from laboratories across North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, Europe, and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

announced the completion of the first complete genome sequence of a eukaryote, ''S. cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungus microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have bee ...

'' (12.1 Mb), and since then genomes have continued being sequenced at an exponentially growing pace. , the complete sequences are available for: 2,719 viruses, 1,115 archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

and bacteria, and 36 eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s, of which about half are fungi.

model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

for the eukaryotic cell, while the fruit fly '' Drosophila melanogaster'' has been a very important tool (notably in early pre-molecular genetics). The worm ''Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''rhabditis'' (ro ...

'' is an often used simple model for multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- ...

s. The zebrafish ''Brachydanio rerio

The zebrafish (''Danio rerio'') is a freshwater fish belonging to the minnow family ( Cyprinidae) of the order Cypriniformes. Native to South Asia, it is a popular aquarium fish, frequently sold under the trade name zebra danio (and thus often ...

'' is used for many developmental studies on the molecular level, and the plant ''Arabidopsis thaliana

''Arabidopsis thaliana'', the thale cress, mouse-ear cress or arabidopsis, is a small flowering plant native to Eurasia and Africa. ''A. thaliana'' is considered a weed; it is found along the shoulders of roads and in disturbed land.

A winter a ...

'' is a model organism for flowering plants. The Japanese pufferfish ('' Takifugu rubripes'') and the spotted green pufferfish

A green spotted puffer may be one of several different species of Asian fresh or brackish water pufferfish in the genus ''Dichotomyctere'' (formerly ''Tetraodon''), including:

*''Dichotomyctere fluviatilis'', sometimes called the green, Ceylon, or ...

(''Tetraodon nigroviridis

''Dichotomyctere nigroviridis'' ( syn. ''Tetraodon nigroviridis'') is one of the pufferfish known as the green spotted puffer. It is found across South and Southeast Asia in coastal freshwater,but survives the longest in brackish to saltwater, a ...

'') are interesting because of their small and compact genomes, which contain very little noncoding DNA compared to most species. The mammals dog ('' Canis familiaris''), brown rat ('' Rattus norvegicus''), mouse ('' Mus musculus''), and chimpanzee ('' Pan troglodytes'') are all important model animals in medical research.

A rough draft of the human genome was completed by the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

in early 2001, creating much fanfare. This project, completed in 2003, sequenced the entire genome for one specific person, and by 2007 this sequence was declared "finished" (less than one error in 20,000 bases and all chromosomes assembled). In the years since then, the genomes of many other individuals have been sequenced, partly under the auspices of the 1000 Genomes Project

The 1000 Genomes Project (abbreviated as 1KGP), launched in January 2008, was an international research effort to establish by far the most detailed catalogue of human genetic variation. Scientists planned to sequence the genomes of at least one th ...

, which announced the sequencing of 1,092 genomes in October 2012. Completion of this project was made possible by the development of dramatically more efficient sequencing technologies and required the commitment of significant bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combi ...

resources from a large international collaboration. The continued analysis of human genomic data has profound political and social repercussions for human societies.

The "omics" revolution

The English-language neologism omics informally refers to a field of study in biology ending in ''-omics'', such as genomics,proteomics

Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins. Proteins are vital parts of living organisms, with many functions such as the formation of structural fibers of muscle tissue, enzymatic digestion of food, or synthesis and replication of DNA. In ...

or metabolomics. The related suffix -ome is used to address the objects of study of such fields, such as the genome, proteome or metabolome respectively. The suffix ''-ome'' as used in molecular biology refers to a ''totality'' of some sort; similarly omics has come to refer generally to the study of large, comprehensive biological data sets. While the growth in the use of the term has led some scientists ( Jonathan Eisen, among others) to claim that it has been oversold, it reflects the change in orientation towards the quantitative analysis of complete or near-complete assortment of all the constituents of a system. In the study of symbioses

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

, for example, researchers which were once limited to the study of a single gene product can now simultaneously compare the total complement of several types of biological molecules.

Genome analysis

After an organism has been selected, genome projects involve three components: the sequencing of DNA, the assembly of that sequence to create a representation of the original chromosome, and the annotation and analysis of that representation.Sequencing

Historically, sequencing was done in ''sequencing centers'', centralized facilities (ranging from large independent institutions such as Joint Genome Institute which sequence dozens of terabases a year, to local molecular biology core facilities) which contain research laboratories with the costly instrumentation and technical support necessary. As sequencing technology continues to improve, however, a new generation of effective fast turnaround benchtop sequencers has come within reach of the average academic laboratory. On the whole, genome sequencing approaches fall into two broad categories, ''shotgun'' and ''high-throughput'' (or ''next-generation'') sequencing.Shotgun sequencing

Shotgun sequencing is a sequencing method designed for analysis of DNA sequences longer than 1000 base pairs, up to and including entire chromosomes. It is named by analogy with the rapidly expanding, quasi-random firing pattern of ashotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge (firearms), cartridge known as a shotshell, which usually discharges numerous small p ...

. Since gel electrophoresis sequencing can only be used for fairly short sequences (100 to 1000 base pairs), longer DNA sequences must be broken into random small segments which are then sequenced to obtain ''reads''. Multiple overlapping reads for the target DNA are obtained by performing several rounds of this fragmentation and sequencing. Computer programs then use the overlapping ends of different reads to assemble them into a continuous sequence. Shotgun sequencing is a random sampling process, requiring over-sampling to ensure a given nucleotide is represented in the reconstructed sequence; the average number of reads by which a genome is over-sampled is referred to as coverage

Coverage may refer to:

Filmmaking

* Coverage (lens), the size of the image a lens can produce

* Camera coverage, the amount of footage shot and different camera setups used in filming a scene

* Script coverage, a short summary of a script, wri ...

.

For much of its history, the technology underlying shotgun sequencing was the classical chain-termination method or 'Sanger method

Sanger sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing that involves electrophoresis and is based on the random incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication. After first being developed by Frederi ...

', which is based on the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotide

Dideoxynucleotides are chain-elongating inhibitors of DNA polymerase, used in the Sanger method for DNA sequencing. They are also known as 2',3' because both the 2' and 3' positions on the ribose lack hydroxyl groups, and are abbreviated as '' ...

s by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication. Recently, shotgun sequencing has been supplanted by high-throughput sequencing methods, especially for large-scale, automated genome analyses. However, the Sanger method remains in wide use, primarily for smaller-scale projects and for obtaining especially long contiguous DNA sequence reads (>500 nucleotides). Chain-termination methods require a single-stranded DNA template, a DNA primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

, a DNA polymerase, normal deoxynucleosidetriphosphates (dNTPs), and modified nucleotides (dideoxyNTPs) that terminate DNA strand elongation. These chain-terminating nucleotides lack a 3'- OH group required for the formation of a phosphodiester bond between two nucleotides, causing DNA polymerase to cease extension of DNA when a ddNTP is incorporated. The ddNTPs may be radioactively or fluorescently labelled for detection in DNA sequencers. Typically, these machines can sequence up to 96 DNA samples in a single batch (run) in up to 48 runs a day.

High-throughput sequencing

The high demand for low-cost sequencing has driven the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies that parallelize the sequencing process, producing thousands or millions of sequences at once. High-throughput sequencing is intended to lower the cost of DNA sequencing beyond what is possible with standard dye-terminator methods. In ultra-high-throughput sequencing, as many as 500,000 sequencing-by-synthesis operations may be run in parallel. The

The Illumina dye sequencing Illumina dye sequencing is a technique used to determine the series of base pairs in DNA, also known as DNA sequencing. The reversible terminated chemistry concept was invented by Bruno Canard and Simon Sarfati at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. I ...

method is based on reversible dye-terminators and was developed in 1996 at the Geneva Biomedical Research Institute, by Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli. In this method, DNA molecules and primers are first attached on a slide and amplified with polymerase

A polymerase is an enzyme ( EC 2.7.7.6/7/19/48/49) that synthesizes long chains of polymers or nucleic acids. DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase are used to assemble DNA and RNA molecules, respectively, by copying a DNA template strand using base- ...

so that local clonal colonies, initially coined "DNA colonies", are formed. To determine the sequence, four types of reversible terminator bases (RT-bases) are added and non-incorporated nucleotides are washed away. Unlike pyrosequencing, the DNA chains are extended one nucleotide at a time and image acquisition can be performed at a delayed moment, allowing for very large arrays of DNA colonies to be captured by sequential images taken from a single camera. Decoupling the enzymatic reaction and the image capture allows for optimal throughput and theoretically unlimited sequencing capacity; with an optimal configuration, the ultimate throughput of the instrument depends only on the A/D conversion

In electronics, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC, A/D, or A-to-D) is a system that converts an analog signal, such as a sound picked up by a microphone or light entering a digital camera, into a digital signal. An ADC may also provide ...

rate of the camera. The camera takes images of the fluorescently labeled nucleotides, then the dye along with the terminal 3' blocker is chemically removed from the DNA, allowing the next cycle.

An alternative approach, ion semiconductor sequencing Ion semiconductor sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing based on the detection of hydrogen ions that are released during the polymerization of DNA. This is a method of "sequencing by synthesis", during which a complementary strand is built based ...

, is based on standard DNA replication chemistry. This technology measures the release of a hydrogen ion each time a base is incorporated. A microwell containing template DNA is flooded with a single nucleotide, if the nucleotide is complementary to the template strand it will be incorporated and a hydrogen ion will be released. This release triggers an ISFET ion sensor. If a homopolymer is present in the template sequence multiple nucleotides will be incorporated in a single flood cycle, and the detected electrical signal will be proportionally higher.

Assembly

Sequence assembly refers to aligning and merging fragments of a much longer DNA sequence in order to reconstruct the original sequence. This is needed as currentDNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

technology cannot read whole genomes as a continuous sequence, but rather reads small pieces of between 20 and 1000 bases, depending on the technology used. Third generation sequencing technologies such as PacBio or Oxford Nanopore routinely generate sequencing reads >10 kb in length; however, they have a high error rate at approximately 15 percent. Typically the short fragments, called reads, result from shotgun sequencing genomic

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dim ...

DNA, or gene transcripts ( ESTs).

Assembly approaches

Assembly can be broadly categorized into two approaches: ''de novo'' assembly, for genomes which are not similar to any sequenced in the past, and comparative assembly, which uses the existing sequence of a closely related organism as a reference during assembly. Relative to comparative assembly, ''de novo'' assembly is computationally difficult (NP-hard

In computational complexity theory, NP-hardness ( non-deterministic polynomial-time hardness) is the defining property of a class of problems that are informally "at least as hard as the hardest problems in NP". A simple example of an NP-hard pr ...

), making it less favourable for short-read NGS technologies. Within the ''de novo'' assembly paradigm there are two primary strategies for assembly, Eulerian path strategies, and overlap-layout-consensus (OLC) strategies. OLC strategies ultimately try to create a Hamiltonian path through an overlap graph which is an NP-hard problem. Eulerian path strategies are computationally more tractable because they try to find a Eulerian path through a deBruijn graph.

Finishing

Finished genomes are defined as having a single contiguous sequence with no ambiguities representing each replicon.Annotation

The DNA sequence assembly alone is of little value without additional analysis.Genome annotation

DNA annotation or genome annotation is the process of identifying the locations of genes and all of the coding regions in a genome and determining what those genes do. An annotation (irrespective of the context) is a note added by way of explanati ...

is the process of attaching biological information to sequences, and consists of three main steps:

# identifying portions of the genome that do not code for proteins

# identifying elements on the genome, a process called gene prediction, and

# attaching biological information to these elements.

Automatic annotation tools try to perform these steps ''in silico

In biology and other experimental sciences, an ''in silico'' experiment is one performed on computer or via computer simulation. The phrase is pseudo-Latin for 'in silicon' (correct la, in silicio), referring to silicon in computer chips. It ...

'', as opposed to manual annotation (a.k.a. curation) which involves human expertise and potential experimental verification. Ideally, these approaches co-exist and complement each other in the same annotation pipeline

Pipeline may refer to:

Electronics, computers and computing

* Pipeline (computing), a chain of data-processing stages or a CPU optimization found on

** Instruction pipelining, a technique for implementing instruction-level parallelism within a s ...

(also see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

).

Traditionally, the basic level of annotation is using BLAST for finding similarities, and then annotating genomes based on homologues. More recently, additional information is added to the annotation platform. The additional information allows manual annotators to deconvolute discrepancies between genes that are given the same annotation. Some databases use genome context information, similarity scores, experimental data, and integrations of other resources to provide genome annotations through their Subsystems approach. Other databases (e.g. Ensembl) rely on both curated data sources as well as a range of software tools in their automated genome annotation pipeline. ''Structural annotation'' consists of the identification of genomic elements, primarily ORFs

ORFS stands for ''Output RF Spectrum'', where 'RF' stands for Radio Frequency.

The acronym ORFS is used in the context of mobile communication systems, e.g., GSM. It stands for the relationship between (a) the frequency offset from the carrier a ...

and their localisation, or gene structure. ''Functional annotation'' consists of attaching biological information to genomic elements.

Sequencing pipelines and databases

The need for reproducibility and efficient management of the large amount of data associated with genome projects mean that computational pipelines have important applications in genomics.Research areas

Functional genomics

Functional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to make use of the vast wealth of data produced by genomic projects (such as genome sequencing projects) to describe gene (and protein) functions and interactions. Functional genomics focuses on the dynamic aspects such as genetranscription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

, translation, and protein–protein interactions, as opposed to the static aspects of the genomic information such as DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

or structures. Functional genomics attempts to answer questions about the function of DNA at the levels of genes, RNA transcripts, and protein products. A key characteristic of functional genomics studies is their genome-wide approach to these questions, generally involving high-throughput methods rather than a more traditional “gene-by-gene” approach.

A major branch of genomics is still concerned with sequencing

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which succ ...

the genomes of various organisms, but the knowledge of full genomes has created the possibility for the field of functional genomics, mainly concerned with patterns of gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

during various conditions. The most important tools here are microarray

A microarray is a multiplex lab-on-a-chip. Its purpose is to simultaneously detect the expression of thousands of genes from a sample (e.g. from a tissue). It is a two-dimensional array on a solid substrate—usually a glass slide or silicon t ...

s and bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combi ...

.

Structural genomics

Structural genomics seeks to describe the 3-dimensional structure of every protein encoded by a given genome. This genome-based approach allows for a high-throughput method of structure determination by a combination of experimental and modeling approaches. The principal difference between structural genomics and traditional structural prediction is that structural genomics attempts to determine the structure of every protein encoded by the genome, rather than focusing on one particular protein. With full-genome sequences available, structure prediction can be done more quickly through a combination of experimental and modeling approaches, especially because the availability of large numbers of sequenced genomes and previously solved protein structures allow scientists to model protein structure on the structures of previously solved homologs. Structural genomics involves taking a large number of approaches to structure determination, including experimental methods using genomic sequences or modeling-based approaches based on sequence or structural homology to a protein of known structure or based on chemical and physical principles for a protein with no homology to any known structure. As opposed to traditional structural biology, the determination of a protein structure through a structural genomics effort often (but not always) comes before anything is known regarding the protein function. This raises new challenges instructural bioinformatics

Structural bioinformatics is the branch of bioinformatics that is related to the analysis and prediction of the three-dimensional structure of biological macromolecules such as proteins, RNA, and DNA. It deals with generalizations about macromol ...

, i.e. determining protein function from its 3D structure.

Epigenomics

Epigenomics is the study of the complete set ofepigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "o ...

modifications on the genetic material of a cell, known as the epigenome. Epigenetic modifications are reversible modifications on a cell's DNA or histones that affect gene expression without altering the DNA sequence (Russell 2010 p. 475). Two of the most characterized epigenetic modifications are DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a biological process by which methyl groups are added to the DNA molecule. Methylation can change the activity of a DNA segment without changing the sequence. When located in a gene promoter, DNA methylation typically acts t ...

and histone modification

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn ar ...

. Epigenetic modifications play an important role in gene expression and regulation, and are involved in numerous cellular processes such as in differentiation/development and tumorigenesis. The study of epigenetics on a global level has been made possible only recently through the adaptation of genomic high-throughput assays.

Metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of ''metagenomes'', genetic material recovered directly from

Metagenomics is the study of ''metagenomes'', genetic material recovered directly from environmental

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

samples. The broad field may also be referred to as environmental genomics, ecogenomics or community genomics. While traditional microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

and microbial genome sequencing rely upon cultivated clonal cultures, early environmental gene sequencing cloned specific genes (often the 16S rRNA 16S rRNA may refer to:

* 16S ribosomal RNA

16 S ribosomal RNA (or 16 S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome ( SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The g ...

gene) to produce a profile of diversity in a natural sample. Such work revealed that the vast majority of microbial biodiversity had been missed by cultivation-based methods. Recent studies use "shotgun" Sanger sequencing or massively parallel pyrosequencing

Pyrosequencing is a method of DNA sequencing (determining the order of nucleotides in DNA) based on the "sequencing by synthesis" principle, in which the sequencing is performed by detecting the nucleotide incorporated by a DNA polymerase. Pyrosequ ...

to get largely unbiased samples of all genes from all the members of the sampled communities. Because of its power to reveal the previously hidden diversity of microscopic life, metagenomics offers a powerful lens for viewing the microbial world that has the potential to revolutionize understanding of the entire living world.

Model systems

Viruses and bacteriophages

Bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

s have played and continue to play a key role in bacterial genetics and molecular biology. Historically, they were used to define gene structure and gene regulation. Also the first genome to be sequenced was a bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

. However, bacteriophage research did not lead the genomics revolution, which is clearly dominated by bacterial genomics. Only very recently has the study of bacteriophage genomes become prominent, thereby enabling researchers to understand the mechanisms underlying phage evolution. Bacteriophage genome sequences can be obtained through direct sequencing of isolated bacteriophages, but can also be derived as part of microbial genomes. Analysis of bacterial genomes has shown that a substantial amount of microbial DNA consists of prophage A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell. Integration of prophages into the bacterial host is the c ...

sequences and prophage-like elements. A detailed database mining of these sequences offers insights into the role of prophages in shaping the bacterial genome: Overall, this method verified many known bacteriophage groups, making this a useful tool for predicting the relationships of prophages from bacterial genomes.

Cyanobacteria

At present there are 24cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

for which a total genome sequence is available. 15 of these cyanobacteria come from the marine environment. These are six '' Prochlorococcus'' strains, seven marine '' Synechococcus'' strains, ''Trichodesmium erythraeum

''Trichodesmium erythraeum'' is a species of cyanobacteria that are unique in being visible to the naked eye. This species is also known as " sea sawdust". It was originally discovered in 1770 by Captain Cook off the coast of Australia.

Anatomy ...

'' IMS101 and ''Crocosphaera watsonii

''Crocosphaera watsonii'' (strain WH8501) is an isolate of a species of unicellular (2.5-6 µm diameter), diazotrophic marine cyanobacteria which represent less than 0.1% of the marine microbial population. They thrive in offshore, open-ocea ...

'' WH8501. Several studies have demonstrated how these sequences could be used very successfully to infer important ecological and physiological characteristics of marine cyanobacteria. However, there are many more genome projects currently in progress, amongst those there are further '' Prochlorococcus'' and marine '' Synechococcus'' isolates, ''Acaryochloris

''Acaryochloris marina'' is a symbiotic species of the phylum Cyanobacteria that produces chlorophyll d, allowing it to use far-red light, at 770 nm wavelength.

Description

It was first discovered in 1993 from coastal isolates of coral in ...

'' and '' Prochloron'', the N2-fixing filamentous cyanobacteria ''Nodularia

''Nodularia'' is a genus of filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae. They occur mainly in brackish or salinic waters, such as the hypersaline Makgadikgadi Pans, the Peel-Harvey Estuary in Western Australia or the Baltic Sea ...

spumigena'', ''Lyngbya aestuarii

''Lyngbya'' is a genus of cyanobacteria, unicellular autotrophs that form the basis of the oceanic food chain.

As a result of recent genetic analyses, several new genera were erected from this genus: ''e.g.'', ''Moorea'', '' Limnoraphis'', '' Ok ...

'' and ''Lyngbya majuscula

''Lyngbya majuscula'' is a species of filamentous cyanobacteria in the genus ''Lyngbya''. It is named after the Dane Hans Christian Lyngbye.

As a result of recent genetic analyses, several new genera were erected from the genus ''Lyngbya'': '' ...

'', as well as bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

s infecting marine cyanobaceria. Thus, the growing body of genome information can also be tapped in a more general way to address global problems by applying a comparative approach. Some new and exciting examples of progress in this field are the identification of genes for regulatory RNAs, insights into the evolutionary origin of photosynthesis, or estimation of the contribution of horizontal gene transfer to the genomes that have been analyzed.

Applications

Genomics has provided applications in many fields, including medicine, biotechnology, anthropology and other social sciences.

Genomics has provided applications in many fields, including medicine, biotechnology, anthropology and other social sciences.

Genomic medicine

Next-generation genomic technologies allow clinicians and biomedical researchers to drastically increase the amount of genomic data collected on large study populations. When combined with new informatics approaches that integrate many kinds of data with genomic data in disease research, this allows researchers to better understand the genetic bases of drug response and disease. Early efforts to apply the genome to medicine included those by a Stanford team led byEuan Ashley

Euan Angus Ashley is a Scottish physician, scientist, author, and founder based at Stanford University in California where he is Associate Dean in the School of Medicine and holds the Roger and Joelle Burnell Chair of Genomics and Precision He ...

who developed the first tools for the medical interpretation of a human genome. The Genomes2People research program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) is the second largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School and the largest hospital in the Longwood Medical Area in Boston, Massachusetts. Along with Massachusetts General Hospital, it is one of the two f ...

, Broad Institute and Harvard Medical School was established in 2012 to conduct empirical research in translating genomics into health. Brigham and Women's Hospital

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) is the second largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School and the largest hospital in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area, Longwood Medical Area in Boston, Massachusetts. Along with Massachusetts Gener ...

opened a Preventive Genomics Clinic in August 2019, with Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General or MGH) is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School located in the West End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. It is the third oldest general hospital in the United Stat ...

following a month later. The ''All of Us'' research program aims to collect genome sequence data from 1 million participants to become a critical component of the precision medicine research platform.

Synthetic biology and bioengineering

The growth of genomic knowledge has enabled increasingly sophisticated applications of synthetic biology. In 2010 researchers at theJ. Craig Venter Institute

The J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) is a non-profit genomics research institute founded by J. Craig Venter, Ph.D. in October 2006. The institute was the result of consolidating four organizations: the Center for the Advancement of G ...

announced the creation of a partially synthetic species of bacterium, '' Mycoplasma laboratorium'', derived from the genome of '' Mycoplasma genitalium''.

Population and conservation genomics

Population genomics has developed as a popular field of research, where genomic sequencing methods are used to conduct large-scale comparisons of DNA sequences among populations - beyond the limits of genetic markers such as short-rangePCR PCR or pcr may refer to:

Science

* Phosphocreatine, a phosphorylated creatine molecule

* Principal component regression, a statistical technique

Medicine

* Polymerase chain reaction

** COVID-19 testing, often performed using the polymerase chain r ...

products or microsatellites traditionally used in population genetics. Population genomics studies genome-wide effects to improve our understanding of microevolution so that we may learn the phylogenetic history and demography of a population. Population genomic methods are used for many different fields including evolutionary biology, ecology, biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

, conservation biology

Conservation biology is the study of the conservation of nature and of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction and the erosion of biotic interactions. It is an int ...

and fisheries management. Similarly, landscape genomics Landscape genomics is one of many strategies used to identify relationships between environmental factors and the genetic adaptation of organisms in response to these factors. Landscape genomics combines aspects of landscape ecology, population gene ...

has developed from landscape genetics

Landscape genetics is the scientific discipline that combines population genetics and landscape ecology. It broadly encompasses any study that analyses plant or animal population genetic data in conjunction with data on the landscape features and ...

to use genomic methods to identify relationships between patterns of environmental and genetic variation.

Conservationists can use the information gathered by genomic sequencing in order to better evaluate genetic factors key to species conservation, such as the genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

of a population or whether an individual is heterozygous for a recessive inherited genetic disorder. By using genomic data to evaluate the effects of evolutionary processes and to detect patterns in variation throughout a given population, conservationists can formulate plans to aid a given species without as many variables left unknown as those unaddressed by standard genetic approaches.

See also

* Cognitive genomics * Computational genomics * Epigenomics * Functional genomics * GeneCalling, an mRNA profiling technology *Genomics of domestication

Domesticated species and the human populations that domesticate them are typified by a mutualistic relationship of interdependence, in which humans have over thousands of years modified the genomics of domesticated species. Genomics is the study o ...

* Genetics in fiction

* Glycomics

* Immunomics

Immunomics is the study of immune system regulation and response to pathogens using genome-wide approaches. With the rise of genomic and proteomic technologies, scientists have been able to visualize biological networks and infer interrelationshi ...

* Metagenomics

* Pathogenomics Pathogenomics is a field which uses high-throughput screening technology and bioinformatics to study encoded microbe resistance, as well as virulence factors (VFs), which enable a microorganism to infect a host and possibly cause disease. This inclu ...

* Personal genomics

* Proteomics

Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins. Proteins are vital parts of living organisms, with many functions such as the formation of structural fibers of muscle tissue, enzymatic digestion of food, or synthesis and replication of DNA. In ...

* Transcriptomics

* Venomics

* Psychogenomics

Behavioural genetics, also referred to as behaviour genetics, is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behaviour. While the name "behavioural genetics" co ...

* Whole genome sequencing

*Thomas Roderick

Thomas Huston Roderick, Ph.D., (1930–2013) was an American geneticist who coined the term “genomics".

Dr. Roderick earned degrees from the University of Michigan in philosophy in 1952 and zoology in 1953 and went on receive a Ph.D. from the Un ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * electronic-book electronic-External links

Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics

BMC Genomics

A BMC journal on Genomics

Genomics journal

Genomics.org

An openfree genomics portal.

NHGRI

US government's genome institute

JCVI Comprehensive Microbial Resource

KoreaGenome.org

The first Korean Genome published and the sequence is available freely.

GenomicsNetwork

Looks at the development and use of the science and technologies of genomics.

Institute for Genome Sciences

Genomics research.

MIT OpenCourseWare HST.512 Genomic Medicine

A free, self-study course in genomic medicine. Resources include audio lectures and selected lecture notes.

ENCODE threads explorer

Machine learning approaches to genomics. Nature (journal)

Global map of genomics laboratories

Genomics: Scitable by nature education

Learn All About Genetics Online

{{Authority control