Galloway Tubes, Section (Heat Engines, 1913) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

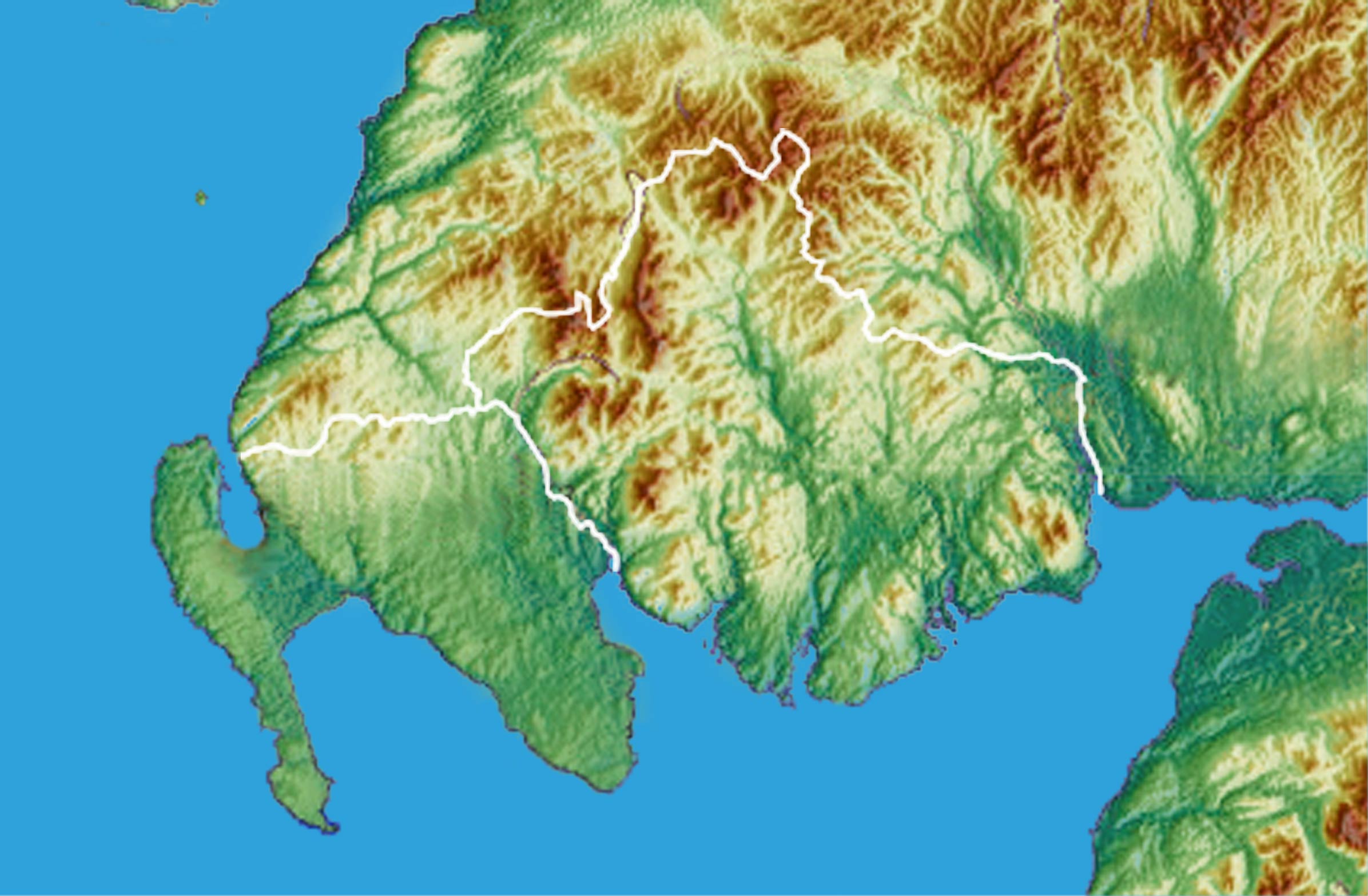

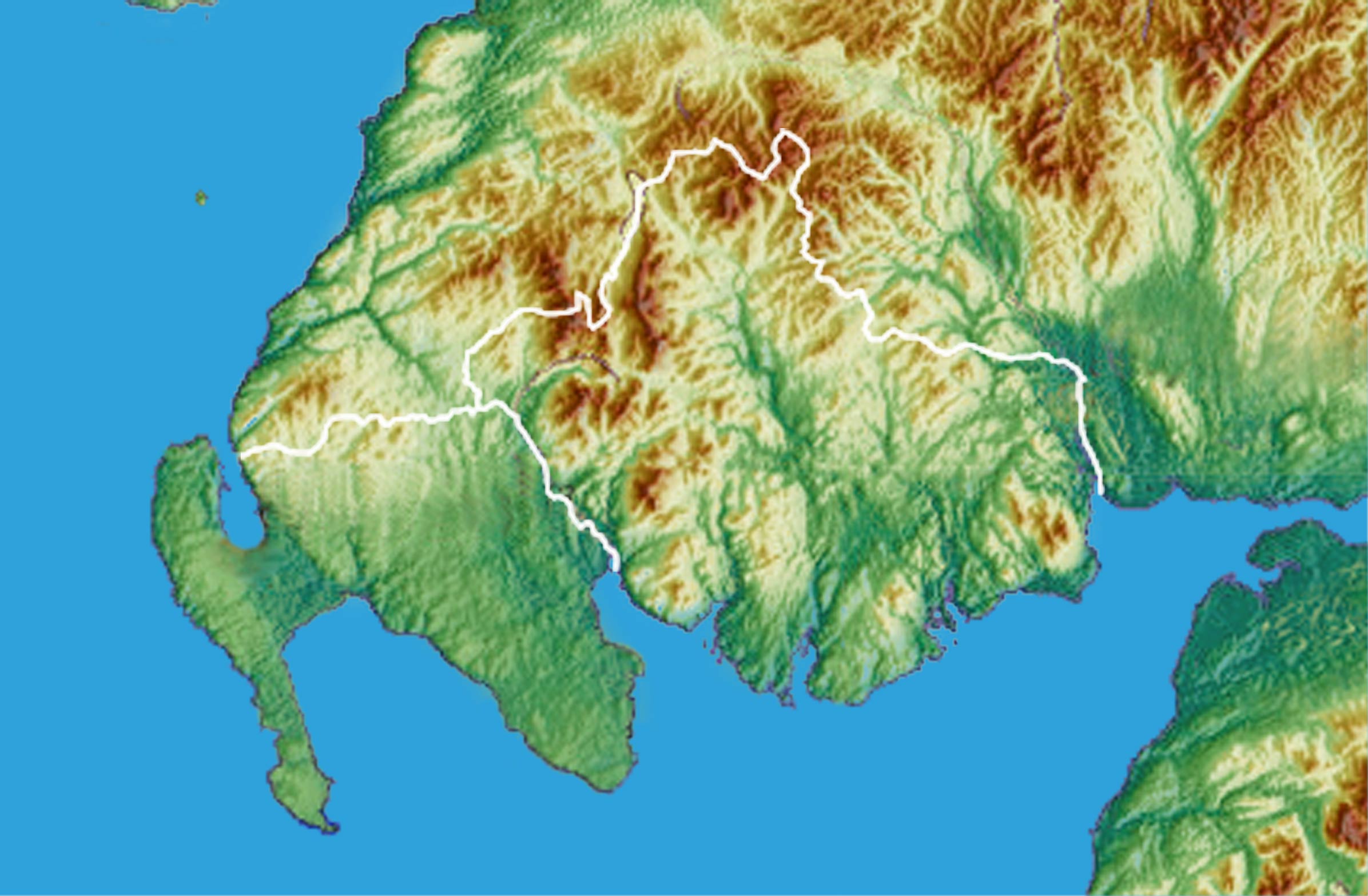

Galloway ( ; ; ) is a region in southwestern

Galloway comprises the part of Scotland lying southwards from the Southern Upland

Galloway comprises the part of Scotland lying southwards from the Southern Upland

It is thought that aspects of the Barsalloch Fort site in Galloway date to the

It is thought that aspects of the Barsalloch Fort site in Galloway date to the

In the 2nd century, the Alexandrian geographer

In the 2nd century, the Alexandrian geographer

Galloway Dialect

at Scots Language Centre {{coord, 55, 03, N, 4, 08, W, source:kolossus-nowiki, display=title Geography of Dumfries and Galloway

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire

Wigtownshire or the County of Wigtown (, ) is one of the Counties of Scotland, historic counties of Scotland, covering an area in the south-west of the country. Until 1975, Wigtownshire was an counties of Scotland, administrative county used for ...

and Kirkcudbrightshire

Kirkcudbrightshire ( ) or the County of Kirkcudbright or the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright is one of the Counties of Scotland, historic counties of Scotland, covering an area in the south-west of the country. Until 1975, Kirkcudbrightshire was an ...

. It is administered as part of the council area {{Unreferenced, date=May 2019, bot=noref (GreenC bot)

A council area is one of the areas defined in Schedule 1 of the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 and is under the control of one of the local authorities in Scotland created by that Ac ...

of Dumfries and Galloway

Dumfries and Galloway (; ) is one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland, located in the western part of the Southern Uplands. It is bordered by East Ayrshire, South Ayrshire, and South Lanarkshire to the north; Scottish Borders to the no ...

.

Galloway is bounded by sea to the west and south, the Galloway Hills

The Galloway Hills are part of the Southern Uplands of Scotland, and form the northern boundary of western Galloway. They lie within the bounds of the Galloway Forest Park, an area of some of largely uninhabited wild land, managed by Forestry an ...

to the north, and the River Nith

The River Nith (; Common Brittonic: ''Nowios'') is a river in south-west Scotland. The Nith rises in the Carsphairn hills of East Ayrshire, between Prickeny Hill and Enoch Hill, east of Dalmellington. For the majority of its course it flows ...

to the east; the border between Kirkcudbrightshire and Wigtownshire is marked by the River Cree

The River Cree is a river in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland which runs through Newton Stewart and into the Solway Firth. It forms part of the boundary between the counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire.

The tributaries of the Cree are ...

. The definition has, however, fluctuated greatly in size over history.

A native or inhabitant of Galloway is called a Gallovidian. The region takes its name from the ''Gall-Gàidheil'', or "stranger Gaels", a people of mixed Gaelic and Norse descent who seem to have settled here in the 10th century. Galloway remained a Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The ter ...

area for much longer than other regions of the Scottish Lowlands

The Lowlands ( or , ; , ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland.

The region is characterised by its relatively flat or gently rolling terrain as opposed to the mountainous landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. This area includes ci ...

and a distinct local dialect of the Scottish Gaelic language

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

survived into at least the 18th century.

A hardy breed of black, hornless cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

named Galloway cattle

The Galloway is a Scottish breed of beef cattle, named after the Galloway region of Scotland, where it originated during the seventeenth century.

It is usually black, is of average size, is naturally polled and has a thick coat suitable for ...

is native to the region, in addition to the more distinctive Belted Galloway

The Belted Galloway is a traditional Scottish breed of beef cattle. It derives from the Galloway (cattle), Galloway stock of the Galloway region of south-western Scotland, and was established as a separate breed in 1921. It is adapted to liv ...

or "Beltie".

Geography and landforms

Galloway comprises the part of Scotland lying southwards from the Southern Upland

Galloway comprises the part of Scotland lying southwards from the Southern Upland watershed

Watershed may refer to:

Hydrology

* Drainage divide, the line that separates neighbouring drainage basins

* Drainage basin, an area of land where surface water converges (North American usage)

Music

* Watershed Music Festival, an annual country ...

and westward from the River Nith

The River Nith (; Common Brittonic: ''Nowios'') is a river in south-west Scotland. The Nith rises in the Carsphairn hills of East Ayrshire, between Prickeny Hill and Enoch Hill, east of Dalmellington. For the majority of its course it flows ...

. Traditionally it has been described as stretching from "the braes of Glenapp to the Nith". The valleys of three rivers, the Urr Water

Urr Water or River Urr (''Archaism, arc. River Orr'') is a river which flows through the counties of Dumfriesshire and Kirkcudbrightshire in southwest Scotland.

Course

Entirely within Dumfries and Galloway, the Urr Water originates at Loch Urr an ...

, the Water of Ken

The Water of Ken is a river in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire in Galloway, south-west Scotland.It rises on Blacklorg Hill, north-east of Cairnsmore of Carsphairn in the Carsphairn hills, and flows south-westward into The Glenkens, ...

and River Dee, and the Cree, all running north–south, provide much of the good arable land

Arable land (from the , "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the purposes of a ...

, although there is also some arable land on the coast. Generally however the landscape is rugged and much of the soil is shallow. The generally south slope and southern coast make for mild and wet climate, and there is a great deal of good pasture.

The northern part of Galloway is exceedingly rugged and forms the largest remaining wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plurale tantum, plural) are Earth, Earth's natural environments that have not been significantly modified by human impact on the environment, human activity, or any urbanization, nonurbanized land not u ...

in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

south of the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Africa

* Highlands, Johannesburg, South Africa

* Highlands, Harare, Zimbab ...

. This area is known as the Galloway Hills

The Galloway Hills are part of the Southern Uplands of Scotland, and form the northern boundary of western Galloway. They lie within the bounds of the Galloway Forest Park, an area of some of largely uninhabited wild land, managed by Forestry an ...

.

Land use

Historically Galloway has been known both forhorse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

s and for cattle rearing, and milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

and beef

Beef is the culinary name for meat from cattle (''Bos taurus''). Beef can be prepared in various ways; Cut of beef, cuts are often used for steak, which can be cooked to varying degrees of doneness, while trimmings are often Ground beef, grou ...

production are both still major industries. There is also substantial timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into uniform and useful sizes (dimensional lumber), including beams and planks or boards. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, window frames). ...

production and some fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a., fishing grounds). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farm ...

. The combination of hills and high rainfall make Galloway ideal for hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other Renewable energ ...

power production, and the Galloway Hydro Power scheme was begun in 1929. Since then, electricity generation

Electricity generation is the process of generating electric power from sources of primary energy. For electric utility, utilities in the electric power industry, it is the stage prior to its Electricity delivery, delivery (Electric power transm ...

has been a significant industry. More recently wind turbine

A wind turbine is a device that wind power, converts the kinetic energy of wind into electrical energy. , hundreds of thousands of list of most powerful wind turbines, large turbines, in installations known as wind farms, were generating over ...

s have been installed at a number of locations on the watershed, and a large offshore wind-power plant is planned, increasing Galloway's 'green energy' production.

History

Mesolithic and Neolithic

It is thought that aspects of the Barsalloch Fort site in Galloway date to the

It is thought that aspects of the Barsalloch Fort site in Galloway date to the Mesolithic period

The Mesolithic ( Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonym ...

. A number of sites date to the Neolithic; these include the Drumtroddan standing stones

The Drumtroddan standing stones () are a small Neolithic or Bronze Age stone alignment in the parish of Mochrum, Wigtownshire, Dumfries and Galloway. The monument comprises three stones, only one of which is now standing, aligned northeast-southw ...

, the Torhousekie stone circle, and the Cairnholy

Cairnholy (or Cairn Holy) is the site of two Neolithic chambered tombs of the Clyde type. It is located 4 kilometres east of the village of Carsluith in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. The tombs are scheduled monuments in the care of Historic ...

chambered cairn. There is also evidence of one of the earliest pit-fall traps in Europe which was discovered near Glenluce

Glenluce () is a small village in the parish of Old Luce in Wigtownshire, Scotland.

It contains a village shop, a caravan park and a town hall, as well as the parish church.

Location

Glenluce on the A75 road between Stranraer () and Newton S ...

, Wigtownshire

Wigtownshire or the County of Wigtown (, ) is one of the Counties of Scotland, historic counties of Scotland, covering an area in the south-west of the country. Until 1975, Wigtownshire was an counties of Scotland, administrative county used for ...

.

Iron Age

TheIron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

is where prehistoric archaeological remains and recorded history overlap for Galloway. Galloway's Iron Age sites are similar to the rest of Scotland. Its distinctive type sites consist of crannog

A crannog (; ; ) is typically a partially or entirely artificial island, usually constructed in lakes, bogs and estuary, estuarine waters of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Unlike the prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, which were built ...

s, promontory forts, and duns

Duns may refer to:

* Duns, Scottish Borders, a town in Berwickshire, Scotland

** Duns railway station

** Duns F.C., a football club

** Duns RFC, a rugby football club

** Battle of Duns, an engagement fought in 1372

* Duns Scotus ( 1265/66– ...

.

Galloway has a preponderance of crannog-type sites compared to certain other regions of Scotland. This is due largely to the region's geography favouring lochs (or now-former lochs), as well as a bias toward higher survival rates of undisturbed sites available for archaeological investigation due to loch-draining taking place later in Galloway than in other regions, with the discovery of such sites eliciting antiquarian interest. For example, the Black Loch of Myrton site (which likely dates to around the 5th century BC) was discovered due to loch-draining activities in the area of the Maxwell family estate during the 19th century. The site received the attention of a local antiquarian, Sir Herbert Maxwell

Sir Herbert Eustace Maxwell, 7th Baronet, (8 January 1845 – 30 October 1937) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, artist, antiquarian, horticulturalist, prominent salmon angler and author of books on angling and Conservative politician who ...

, who conducted a basic excavation. Initially thought to be a crannog, the Black Loch of Myrton site was later recharacterized as a "lochside village".

Promontory forts are highly topographically-defined sites, which in Galloway generally occupy coastal promontories overlooking the Solway Firth. Investigation of one such site at Carghidown revealed a "sporadically occupied refuge" according to Toolis, who also notes that "hardly any promontory forts occupy strongly defensive locations or have immediate access to the sea." While many surviving sites represent sporadically-occupied locations or individual households, there are also examples of multiple-household settlements. One of these is the Rispain Camp site near Whithorn, which contained a form of bread wheat unique amongst Iron Age sites in Galloway. This is a possible indication that Rispain Camp had different agricultural practices than elsewhere in Galloway, especially given the relatively low occurrence of rotary querns

A quern-stone is a stone tool for hand-grinding a wide variety of materials, especially for various types of grains.

They are used in pairs. The lower stationary stone of early examples is called a ''saddle quern'', while the upper mobile st ...

at sites in the area. Roughly contemporary with the Rispain Camp site, a cluster of roundhouses at Dunragit (dating to the early centuries AD) was revealed to contain examples of native (i.e. non-Roman) pottery.

Certain households in Galloway seem to have taken social prominence later in the Iron Age. Lead items appear; isotope analysis of goods at a number of Iron Age and Roman period sites indicate the Scottish Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands () are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas (the others being the Central Lowlands and the Highlands). The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to col ...

as a possible ore source for the lead material, though it is unclear how early extraction of lead could have taken place in Galloway specifically. Metallurgical testing done on three lead beads recovered from the Carghidown site (dated to ) indicated a closer affinity to the Southern Uplands than to a sample from the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

. The area around Whithorn, containing both the Carghidown and Rispain Camp sites, appears to have become a local power centre. The Carghidown site is located only a short distance to the east along the coast from St Ninian's Cave

St Ninian's Cave is a cave in Physgill Glen, Whithorn, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. It features in the climax of the 1973 horror film ''The Wicker Man''. It is a place of Roman Catholic pilgrimage by way of its association with the Scottish s ...

, while the Rispain Camp site is several miles inland.

Following the start of the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain was the Roman Empire's conquest of most of the island of Great Britain, Britain, which was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the ...

, the Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (; 13 June 40 – 23 August 93) was a Roman general and politician responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Born to a political family of senatorial rank, Agricola began his military career as a military tribu ...

campaigned northward, reaching Scotland around AD 79. A possible comment about "trackless wastes" may have referred to Galloway, but this is unclear. The source of this comment is the version of Tacitus' ''Agricola

Agricola, the Latin word for farmer, may also refer to:

People Cognomen or given name

:''In chronological order''

* Gnaeus Julius Agricola (40–93), Roman governor of Britannia (AD 77–85)

* Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, Roman governor of the m ...

'' which is contained in the ''Codex Aesinas

The Codex Aesinas (''Codex Aesinas Latinus 8'') is a 15th-century composite manuscript. It was discovered by chance in 1902 at the former private estate of the Count Baldeschi Balleani family located in Jesi, in the province of Ancona, Italy. Th ...

''. The ''Codex Aesinas'' is a composite work produced in the 15th century, which is based on a now-lost 9th century work, the '' Codex Hersfeldensis'', which contained portions of the ''Agricola''. The interpretation of "trackless wastes" is based on material thought to derive from the 9th century codex, with an original Latin ("first crossing into the trackless wastes") having been corrupted into , which is grammatically incorrect in Latin. The interpretation that this passage refers to Galloway is based on contextual information, as the work later refers to "the part of Britain that faces Ireland", which is seen as referring to southwestern Scotland.

In the 2nd century, the Alexandrian geographer

In the 2nd century, the Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

produced his ''Geographia

The ''Geography'' (, , "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, compiling the geographical knowledge of the 2nd-century Roman Empire. Originally wri ...

'', which was written . This work included Britain. No surviving copies of the ''Geographia'' exist which are older than the 13th century, creating the possibility that details may have been lost or distorted. Ptolemy credited much of his work to a now-lost atlas by Marinus of Tyre

Marinus of Tyre (, ''Marînos ho Týrios''; 70–130) was a List of Graeco-Roman geographers, geographer, Cartography, cartographer and mathematician, who founded mathematical geography and provided the underpinnings of Claudius Ptolemy's i ...

, a previous geographer whose work is thought to have been created around AD 114. Though it would have been written within the century after Agricola's campaign, Ptolemy's work is a Roman perspective on Britain following the conquest, and not necessarily a reflection of pre-Roman social or ethnic groups. Ptolemy listed two peoples as inhabitants of the area around Galloway: the Novantae

The Novantae were people of the Iron age, as recorded in Ptolemy's ''Geography'' (written c. 150AD). The Novantae are thought to have lived in what is now Galloway and Carrick, in southwesternmost Scotland.

While the Novantae are assumed to be ...

in the west (associated with Wigtownshire, Kirkcudbrightshire, and southern Ayrshire) and the Selgovae

The Selgovae (Common Brittonic: *''Selgowī'') were a Celtic tribe of the late 2nd century AD who lived in what is now Kirkcudbrightshire and Dumfriesshire, on the southern coast of Scotland. They are mentioned briefly in Ptolemy's ''Geography'' ...

in the east (primarily associated with modern-day Dumfriesshire). It is thought that the Iron Age inhabitants of the Barsalloch Fort site were the Novantae people. The Rispain Camp site is also associated with the Novantae.

In the west, the city of (literally 'very royal place'), shown on Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's map of the world, is a strong contender for the site of , referred to in the Welsh Triads

The Welsh Triads (, "Triads of the Island of Britain") are a group of related texts in medieval manuscripts which preserve fragments of Welsh folklore, mythology and traditional history in groups of three. The triad is a rhetorical form whereby o ...

as one of the 'three thrones of Britain' associated with the legendary King Arthur

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Great Britain, Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Wales, Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a le ...

, and may also have been the ' of the sub-Roman

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

Brython

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', , ), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, ...

ic kingdom of . 's exact position is uncertain except that it was 'on Loch Ryan

Loch Ryan (, ) is a Scottish sea loch that acts as an important natural harbour for shipping, providing calm waters for ferries operating between Scotland and Northern Ireland. The town of Stranraer is the largest settlement on its shores, wi ...

', close to modern day Stranraer

Stranraer ( , in Scotland also ; ), also known as The Toon or The Cleyhole, is a town in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, on Loch Ryan and the northern side of the isthmus joining the Rhins of Galloway to the mainland. Stranraer is Dumfries ...

; it is possible that it is the modern settlement of Dunragit

Dunragit () is a village on the A75 road, A75, between Stranraer and Glenluce in Dumfries and Galloway, south-west Scotland. Dunragit is within the parish of Old Luce, in the traditional county of Wigtownshire. The modern village grew up around ...

().

According to tradition, before the end of Roman rule in Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caesa ...

, St. Ninian established a church or monastery at Whithorn

Whithorn (; ), is a royal burgh in the historic county of Wigtownshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, about south of Wigtown. The town was the location of the first recorded Christian church in Scotland, "White/Shining House", built by ...

, Wigtownshire

Wigtownshire or the County of Wigtown (, ) is one of the Counties of Scotland, historic counties of Scotland, covering an area in the south-west of the country. Until 1975, Wigtownshire was an counties of Scotland, administrative county used for ...

, which remained an important place of pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

until the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

.

Middle Ages

A Brythonic speaking kingdom dominated Galloway until the late 7th century when it was absorbed by theEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia () was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was approximately equivalent to the modern English cou ...

.

English prevalence was supplanted by Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

and Norse-Gaelic () peoples between the 9th and the 11th century. This can be seen in the context of both the vacuum left by Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

being filled by the resurgent Cumbric Britons and the influx of the Norse into the Irish Sea, including settlement in the Isle of Man and in the now English region of western Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial county in North West England. It borders the Scottish council areas of Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders to the north, Northumberland and County Durham to the east, North Yorkshire to the south-east, Lancash ...

immediately south of Galloway.

If it had not been for Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway (died 12 May 1161) was a twelfth-century Lord of Galloway. Although his familial origins are unknown, it is possible that he was of Norse-Gaelic ancestry. Fergus first appears on record in 1136, when he witnessed a charter o ...

who established himself in Galloway in the mid-twelfth century, the region would rapidly have been absorbed by Scotland. This did not happen because Fergus, his sons, grandsons and great-grandson Alan, Lord of Galloway

Alan of Galloway (before 1199 – 1234) was a leading thirteenth-century Scottish magnate. As the hereditary Lord of Galloway and Constable of Scotland, he was one of the most influential men in the Kingdom of Scotland and Irish Sea zone.

Ala ...

, shifted their allegiance between Scottish and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

kings. During a period of Scottish allegiance, a Galloway contingent followed David, King of Scots, in his invasion of England and led the attack in his defeat at the Battle of the Standard

The Battle of the Standard, sometimes called the Battle of Northallerton, took place on 22 August 1138 on Cowton Moor near Northallerton in Yorkshire, England. English forces under William of Aumale repelled a Scottish army led by King Davi ...

(1138).

Alan died in 1234, leaving three daughters and an illegitimate son, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

(). Alexander II of Scotland

Alexander II ( Medieval Gaelic: '; Modern Gaelic: '; nicknamed "the Peaceful" by modern historians; 24 August 1198 – 6 July 1249) was King of Alba (Scotland) from 1214 until his death. He concluded the Treaty of York (1237) which defined t ...

, Galloway's suzerain, planned to divide Galloway between Alan's three daughters and their husbands (all Norman noblemen) and to exclude Thomas under Norman feudal law. However, Thomas considered himself Alan's heir under the Gaelic system of tanistry

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist (; ; ) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ireland, Scotland and Mann, to succeed to ...

. In the ensuing Galloway revolt of 1234–1235

The Galloway revolt of 1234–1235 was an uprising in Galloway during 1234–1235, led by Tomás mac Ailein and Gille Ruadh. The uprising was in response to the succession of Alan of Galloway, whereby King Alexander II of Scotland ordered Gal ...

, an army of Galwegian rebels ambushed Alexander's royal army and nearly inflicted a defeat before relief forces arrived to support the king. The rebels retreated to Ireland, and Alexander left Walter Comyn, Lord of Badenoch

Walter Comyn, Lord of Badenoch (died 1258) was the son of William Comyn, Justiciar of Scotia and Mormaer or Earl of Buchan by right of his second wife.

Life

Walter makes his first appearance in royal charters as early as 1211–1214. In 122 ...

to subdue Galloway; Comyn sacked its abbeys before fleeing when faced with the return of the rebels. The rebellion was eventually ended with the return of royal forces. The result was a partition of Galloway, serving to fragment it administratively, though some ecclesiastical (the bishopric) and judicial (the office of Justiciar of Galloway

The Justiciar of Galloway was an important legal office in the High Medieval Kingdom of Scotland.

The Justiciars of Galloway were responsible for the administration of royal justice in the province of Galloway. The other Justiciar positions wer ...

) offices survived further into the High Medieval period and beyond.

Alan's eldest daughter, (Latinized as Dervorguilla), married John de Balliol

John Balliol or John de Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as Toom Tabard (meaning 'empty coat'), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

, and their son (also John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

) became one of the candidates for the Scottish Crown. Consequently, Scotland's Wars of Independence

Wars of national liberation, also called wars of independence or wars of liberation, are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) ...

were disproportionately fought in Galloway.

There were a large number of new Gaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

placenames being coined post 1320 (e.g. Balmaclellan

Balmaclellan (Scottish Gaelic: ''Baile Mac-a-ghille-dhiolan'', meaning town of the MacLellans) is a small hillside village of stone houses with slate roofs in a fold of the Galloway hills in south-west Scotland. To the west, across the Ken River ...

), because Galloway retained a substantial Gaelic speaking population for several centuries more. Following the Wars of Independence, Galloway became the fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

of Archibald the Grim

Archibald Douglas, Earl of Douglas and Wigtown, Lord of Galloway, Douglas and Bothwell (c. 1330 – c. 24 December 1400), called Archibald the Grim or Black Archibald, was a late medieval Scottish nobleman. Archibald was the illegitimate son o ...

, Earl of Douglas

This page is concerned with the holders of the forfeit title Earl of Douglas and the preceding Scottish feudal barony, feudal barons of Douglas, South Lanarkshire. The title was created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1358 for William Douglas, 1 ...

. In 1369, he received the part of Galloway east of the River Cree

The River Cree is a river in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland which runs through Newton Stewart and into the Solway Firth. It forms part of the boundary between the counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire.

The tributaries of the Cree are ...

, where he appointed a steward to administer the area, which became known as the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright

Kirkcudbrightshire ( ) or the County of Kirkcudbright or the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright is one of the historic counties of Scotland, covering an area in the south-west of the country. Until 1975, Kirkcudbrightshire was an administrative county ...

. The following year, he acquired the part of Galloway west of the Cree, which continued to be administered by the king's sheriff, and so became known as the Shire of Wigtown. The two parts of Galloway thereafter were administered separately, becoming separate counties

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

.

The High Medieval period saw a gradual incorporation of Galloway into Scotland. Scotland's legal system was administered as a system of three provinces, each with a justiciar (high official). The Justiciar of Galloway

The Justiciar of Galloway was an important legal office in the High Medieval Kingdom of Scotland.

The Justiciars of Galloway were responsible for the administration of royal justice in the province of Galloway. The other Justiciar positions wer ...

was one of these, along with justiciars for Lothian and "Scotia" (lands north of the Forth and Clyde). Additionally, Whithorn remained an important cultural centre; medieval kings of Scots made pilgrimages there.

Reformation and Covenanters

Folklore holds that a copy of theWycliffe Bible

Wycliffe's Bible (also known as the Middle English Bible ''MEB Wycliffite Bibles, or Wycliffian Bibles) is a sequence of orthodox Middle English Bible translations from the Latin Vulgate which appeared over a period from approximately 1382 to ...

was circulating in Galloway around 1520, and secret groups (proto-conventicles) gathered to hear a man named Alexander Gordon preach from it. With the end of the monasteries, the large ecclesiastical landholdings created under the medieval Lordship of Galloway were broken up amongst hundreds of small landowners. In the case of Dundrennan Abbey

Dundrennan Abbey, in Dundrennan, Scotland, near to Kirkcudbright, was a Cistercian monastery in the Romanesque architectural style, established in 1142 by Fergus of Galloway, King David I of Scotland (1124–53), and monks from Rievaulx Abbe ...

, much of the abbey's lands came into the hands of the family of its last abbot, Edward Maxwell. Following the death of the pre-Reformation Bishop of Galloway

The Bishop of Galloway, also called the Bishop of Whithorn, is the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Galloway, said to have been founded by Saint Ninian in the mid-5th century. The subsequent Anglo-Saxon bishopric was founded in the late 7 ...

in 1575, there were disputes over who would be bishop, and the see was vacant for a considerable period of time in the late 16th century due to opposition to episcopal polity

An episcopal polity is a hierarchical form of church governance in which the chief local authorities are called bishops. The word "bishop" here is derived via the British Latin and Vulgar Latin term ''*ebiscopus''/''*biscopus'', . It is the ...

by the Presbyterian faction within the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

.

The Anglo-Scottish Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

took place in 1603, leading to the supremacy of the Stuart dynasty

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been hel ...

in Britain and Ireland. James

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

, the Stuart monarch of both Scotland and England, heavily policed the activities of the riding clans of the nearby Scottish Borders

The Scottish Borders is one of 32 council areas of Scotland. It is bordered by West Lothian, Edinburgh, Midlothian, and East Lothian to the north, the North Sea to the east, Dumfries and Galloway to the south-west, South Lanarkshire to the we ...

, leading to a large number of Borderers emigrating or being transported to Ireland or to the American colonies. The Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster (; Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster Scots: ) was the organised Settler colonialism, colonisation (''Plantation (settlement or colony), plantation'') of Ulstera Provinces of Ireland, province of Irelandby people from Great ...

began around this time.

Attempts beginning under James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

to enforce Caesaropapism

Caesaropapism is the idea of combining the social and political power of secular government with religious power, or of making secular authority superior to the spiritual authority of the Church, especially concerning the connection of the Chu ...

, episcopal polity

An episcopal polity is a hierarchical form of church governance in which the chief local authorities are called bishops. The word "bishop" here is derived via the British Latin and Vulgar Latin term ''*ebiscopus''/''*biscopus'', . It is the ...

, high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

Anglicanism

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

, and Laudianism

Laudianism, also called Old High Churchmanship, or Orthodox Anglicanism as they styled themselves when debating the Tractarians, was an early seventeenth-century reform movement within the Church of England that tried to avoid the extremes of Rom ...

within the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

, ultimately triggered the Presbyterian backlash of the 17th-century Bishops' Wars

The Bishops' Wars were two separate conflicts fought in 1639 and 1640 between Scotland and England, with Scottish Royalists allied to England. They were the first of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which also include the First and Second En ...

, which saw the appearance of the Covenanters

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son ...

as a religious, political, and military force. The Covenanters began as participants in conventicles

A conventicle originally meant "an assembly" and was frequently used by ancient writers to mean "a church." At a semantic level, ''conventicle'' is a Latinized synonym of the Greek word for ''church'', and references Jesus' promise in Matthew 18: ...

, which, similarly to the use of Mass stones by the equally illegal Catholic Church in Scotland

The Catholic Church in Scotland, overseen by the Scottish Bishops' Conference, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church headed by the Pope. Christianity first arrived in Roman Britain and was strengthened by the conversion of the Picts thr ...

, were unsanctioned secret religious services that took place outdoors, in barns, or in granaries. The Covenanter movement was particularly popular in the southwest of Scotland. Covenanters had skirmishes with government troops in Galloway, some of which featured the "Galloway flail", a variant of the agriculturally-derived melee weapon.

Cattle trade

Galloway's agricultural economy was indirectly affected by the 17th-century Plantation of Ulster. Peasants in Galloway had, dating back to the Middle Ages, traditionally practiced a mixture of dairy-focused pastoraltranshumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or Nomad, nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and low ...

and intensive agriculture, with pockets of arable land

Arable land (from the , "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the purposes of a ...

being intensively cultivated by some peasants, while others migrated between upland and lowland pastures with their herds. Landowners such as Sir John Murray, the earl of Annandale, received large land grants in Ulster which were only suitable for pasture. In order for their tenants in Ireland to pay rent, an export market had to be created, which was soon sanctioned by the Scottish Privy Council, for Irish cattle to be exported to England via Galloway. Some landowners used the cattle trade in the 17th century as a way to grow their landholdings, as the system of a large number of small landholders began to consolidate into larger estates. The Irish cattle trade increased until up to 10,000 head of cattle per year were being exported through this route in the year 1667. It was in this year that the importation of Irish cattle to England was banned. However, the importation of Scottish cattle was not banned; this created a new opportunity for Galloway landowners to profit from illicit Irish cattle. By this time, a number of prominent individuals associated with the Stuart monarchy held lands in both Galloway and in Ulster, facilitating the illicit trade, which "may have been tolerated for political reasons". Many of these landowners were also Episcopalian

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protes ...

s.

Galwegian Gaelic

Galwegian Gaelic (also known as Gallovidian Gaelic, Gallowegian Gaelic, or Galloway Gaelic) is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the early mo ...

seems to have lasted longer than Gaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

in other parts of Lowland Scotland

The Lowlands ( or , ; , ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland.

The region is characterised by its relatively flat or gently rolling terrain as opposed to the mountainous landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. This area includes ci ...

, and Margaret McMurray

Margaret McMurray (died 1760) appears to have been one of the last native speakers of a Lowland dialect of Scottish Gaelic in the Galloway variety.

In ''The Scotsman'' of 18 November 1951 appeared the following letter, which had originally been ...

(d. 1760) of Carrick (outside modern Galloway) appears to have been the last recorded speaker.

Modern history

In modern times,Stranraer

Stranraer ( , in Scotland also ; ), also known as The Toon or The Cleyhole, is a town in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, on Loch Ryan and the northern side of the isthmus joining the Rhins of Galloway to the mainland. Stranraer is Dumfries ...

was a major ferry port, but the company have now moved to Cairnryan

Cairnryan (;

or ) is a village in the historical county of < ...

.

or ) is a village in the historical county of < ...

Galloway in literature

Galloway has been the setting of a number of novels, includingWalter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

's ''Guy Mannering

''Guy Mannering; or, The Astrologer'' is the second of the Waverley novels by Walter Scott, published anonymously in 1815. According to an introduction that Scott wrote in 1829, he had originally intended to write a story of the supernatural, ...

''.

Other novels include the historical fiction trilogy by Liz Curtis Higgs, ''Thorn in My Heart'', ''Fair is the Rose'', and ''Whence Came a Prince''. Richard Hannay

Major-General Sir Richard Hannay, KCB, OBE, DSO, is a fictional character created by Scottish novelist John Buchan and further made popular by the 1935 Alfred Hitchcock film '' The 39 Steps'' (and other later film adaptations), very loosely b ...

flees London to lie low in Galloway in John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, British Army officer, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

As a ...

's novel ''The Thirty-nine Steps

''The Thirty-Nine Steps'' is a 1915 adventure novel by the Scottish literature, Scottish author John Buchan, first published by William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh. It was Serial (literature), serialized in ''Argosy (magazine)#The All-Story, ...

''. ''Five Red Herrings

''The Five Red Herrings'' (also ''The 5 Red Herrings'') is a 1931 novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her sixth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. In the United States it was published in the same year under the title ''Suspicious Characters''.

Plot

The n ...

'', a whodunit

A ''whodunit'' (less commonly spelled as ''whodunnit''; a colloquial elision of "Who asdone it?") is a complex plot-driven variety of detective fiction

Detective fiction is a subgenre of crime fiction and mystery fiction in which an criminal ...

by Dorothy L. Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers ( ; 13 June 1893 – 17 December 1957) was an English crime novelist, playwright, translator and critic.

Born in Oxford, Sayers was brought up in rural East Anglia and educated at Godolphin School in Salisbury and Somerv ...

, initially published in the US as ''Suspicious Characters'', sees Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A amateur, dilettante who solves myst ...

, on holiday in Kirkcudbright

Kirkcudbright ( ; ) is a town at the mouth of the River Dee, Galloway, River Dee in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, southwest of Castle Douglas and Dalbeattie. A former royal burgh, it is the traditional county town of Kirkcudbrightshire.

His ...

, investigating the death of an artist living at Gatehouse of Fleet

Gatehouse of Fleet ( ) is a town, half in the civil parish of Girthon, and half in the parish of Anwoth, divided by the river Water of Fleet, Fleet, Kirkcudbrightshire, within the council administrative area of Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland.

...

; the book contains some remarkable descriptions of the countryside. S R Crockett, a bestselling writer of historical romances active before the First World War, set several novels in the region including '' The Raiders'' and ''Silver Sand Silver sand is a fine white sand used in gardening. It consists largely of quartz particles that are not coated with iron oxides. Iron oxides colour sand from yellows to rich brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but i ...

''.

Galloway is also the setting of several memoirs, including Devorgilla Days written by Wigtownshire

Wigtownshire or the County of Wigtown (, ) is one of the Counties of Scotland, historic counties of Scotland, covering an area in the south-west of the country. Until 1975, Wigtownshire was an counties of Scotland, administrative county used for ...

author Kathleen Hart, an account of life in Wigtown

Wigtown ( (both used locally); ) is a town and former royal burgh in Wigtownshire, of which it is the county town, within the Dumfries and Galloway region in Scotland. It lies east of Stranraer and south of Newton Stewart. It is known as "Scotl ...

, Scotland's national book town.

With regard to Scottish Gaelic literature

Scottish Gaelic literature refers to literary works composed in the Scottish Gaelic language, which is, like Irish and Manx, a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages. Gaelic literature was also composed in Gàidhealtachd communities ...

, the only text known to survive in Galwegian Gaelic

Galwegian Gaelic (also known as Gallovidian Gaelic, Gallowegian Gaelic, or Galloway Gaelic) is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the early mo ...

is a song called ''Òran Bagraidh'', which was collected from a North Uist

North Uist (; ) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Etymology

In Donald Munro's ''A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides'' of 1549, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist are described as one isla ...

seanchaidh by Celticist

Celtic studies or Celtology is the academic discipline occupied with the study of any sort of cultural output relating to the Celtic-speaking peoples (i.e. speakers of Celtic languages). This ranges from linguistics, literature and art history ...

Donald MacRury.

In Canadian literature

Canadian literature is written in several languages including Canadian English, English, Canadian French, French, and various Indigenous Canadian languages. It is often divided into French- and English-language literatures, which are rooted in th ...

, poet and playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes play (theatre), plays, which are a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between Character (arts), characters and is intended for Theatre, theatrical performance rather than just

Readin ...

Watson Kirkconnell

Watson Kirkconnell, (16 May 1895 – 26 February 1977) was a Canadian literary scholar, poet, playwright, linguist, satirist, and translator.

Kirkconnell was born in Port Hope, Ontario into a proudly Scottish-Canadian family descended from Uni ...

's visit to his ancestral village in the region inspired his original poem ''"Kirkconnell, Galloway, A.D. 600. Visited A.D. 1953"''. The poet pondered how much the culture of the region and the celebration of Christmas Day

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A liturgical feast central to Christianity, Chri ...

had changed since Kirkconnel

Kirkconnel ( Gaelic: ''Cille Chonbhaill'') is a small parish in Dumfries and Galloway, southwestern Scotland. It is located on the A76 near the head of Nithsdale. Principally it has been a sporting community. The name comes from The Church of ...

l Abbey was founded by St. Conal, a Culdee

The Culdees (; ) were members of ascetic Christian monastic and eremitical communities of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England in the Middle Ages. Appearing first in Ireland and then in Scotland, subsequently attached to cathedral or collegiate ...

monk from Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

and missionary of the Celtic Church

Celtic Christianity is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. The term Celtic Church is deprecated by many historians as it implies a unified and identifiab ...

. The landscape, he commented, remained largely unchanged and called upon his readers to embrace the awe that their ancestors had once felt before the incarnation and birth of Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

.Watson Kirkconnell (1966), ''Centennial Tales and Selected Poems'', University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calendar. Its first s ...

, for Acadia University

Acadia University is a public, predominantly Undergraduate education, undergraduate university located in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada, with some Postgraduate education, graduate programs at the master's level and one at the Doctorate, doctor ...

. Pages 132-133.

See also

* Galloway Association of Glasgow * Galloway ponyReferences

* Brooke, D: ''Wild Men and Holy Places''. Edinburgh: Canongate Press, 1994 * Oram, Richard, ''The Lordship of Galloway''. University of St Andrews, 1988 *External links

Galloway Dialect

at Scots Language Centre {{coord, 55, 03, N, 4, 08, W, source:kolossus-nowiki, display=title Geography of Dumfries and Galloway