Forensic Scientists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of

In 16th-century Europe, medical practitioners in army and university settings began to gather information on the cause and

In 16th-century Europe, medical practitioners in army and university settings began to gather information on the cause and  In

In

In 1877 at Hooghly (near Kolkata), Herschel instituted the use of fingerprints on contracts and deeds, and he registered government pensioners' fingerprints to prevent the collection of money by relatives after a pensioner's death.

In 1880, Dr.

In 1877 at Hooghly (near Kolkata), Herschel instituted the use of fingerprints on contracts and deeds, and he registered government pensioners' fingerprints to prevent the collection of money by relatives after a pensioner's death.

In 1880, Dr.  Juan Vucetich, an Argentine chief police officer, created the first method of recording the fingerprints of individuals on file. In 1892, after studying Galton's pattern types, Vucetich set up the world's first fingerprint bureau. In that same year, Francisca Rojas of

Juan Vucetich, an Argentine chief police officer, created the first method of recording the fingerprints of individuals on file. In 1892, after studying Galton's pattern types, Vucetich set up the world's first fingerprint bureau. In that same year, Francisca Rojas of

By the turn of the 20th century, the science of forensics had become largely established in the sphere of criminal investigation. Scientific and surgical investigation was widely employed by the

By the turn of the 20th century, the science of forensics had become largely established in the sphere of criminal investigation. Scientific and surgical investigation was widely employed by the  ''Handbook for Coroners, police officials, military policemen'' was written by the

''Handbook for Coroners, police officials, military policemen'' was written by the

Hans Gross applied scientific methods to crime scenes and was responsible for the birth of criminalistics.

Hans Gross applied scientific methods to crime scenes and was responsible for the birth of criminalistics.

Later in the 20th century several British pathologists, Mikey Rochman, Francis Camps,

Later in the 20th century several British pathologists, Mikey Rochman, Francis Camps,

" DNA Evidence Can Be Fabricated, Scientists Show"

. ''The New York Times''.

"How Accurate are Crime Shows on TV? Debunking 7 Common Myths,"

7 February 2017, ''Blog,'' School of Justice Studies, Rasmussen College, Inc., Oak Brook, IL, retrieved 31 May 2017Stanton, Dawn (quoting Robert Shaler, Ph.D., prof. of biochemistry and molecular biology, dir., forensic science program, Pennsylvania State University, Penn. State Univ. formerly at Pittsburgh Crime Laboratory, New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner, and Lifecodes Corp (nation's first forensic DNA laboratory))

"Probing Question: Is forensic science on TV accurate?,"

10 November 2009, Eberly College of Science, Pennsylvania State University, Penn. State Univ., retrieved 31 May 2017 Some claim these modern TV shows have changed individuals' expectations of forensic science, sometimes unrealisticallyŌĆöan influence termed the "CSI effect".Alldredge, Joh

"The 'CSI Effect' and Its Potential Impact on Juror Decisions,"

(2015) ''Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science'': Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 6., retrieved 31 May 2017 Further, research has suggested that public misperceptions about criminal forensics can create, in the mind of a juror, unrealistic expectations of forensic evidenceŌĆöwhich they expect to see before convictingŌĆöimplicitly biasing the juror towards the defendant. Citing the "CSI effect," at least one researcher has suggested screening jurors for their level of influence from such TV programs.

Anil Aggrawal's Internet Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology

* ''Forensic Magazine'' ŌĆ

Forensicmag.com

an open access journal of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, FBI.

Forensic sciences international

ŌĆō An international journal dedicated to the applications of medicine and science in the administration of justice ŌĆō ŌĆō Elsevier

International Journal of Digital Crime and Forensics

"The Real CSI"

PBS Frontline (U.S. TV series), Frontline documentary, 17 April 2012. * Baden, Michael; Roach, Marion. ''Dead Reckoning: The New Science of Catching Killers'', Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Bartos, Leah

"No Forensic Background? No Problem"

''ProPublica'', 17 April 2012. * Guatelli-Steinberg, Debbie; Mitchell, John C

Structure Magazine no. 40, "RepliSet: High Resolution Impressions of the Teeth of Human Ancestors"

* * Holt, Cynthia

''Guide to Information Sources in the Forensic Sciences''

Libraries Unlimited, 2006. . * Jamieson, Allan; Moenssens, Andre (eds).

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2009.

Online version

* Kind, Stuart; Overman, Michael. ''Science Against Crime'' Doubleday, 1972. . * Lewis, Peter Rhys; Gagg Colin; Reynolds, Ken. ''Forensic Materials Engineering: Case Studies'' CRC Press, 2004. * Nickell, Joe; Fischer, John F. ''Crime Science: Methods of Forensic Detection'', University Press of Kentucky, 1999. . * Owen, D. (2000). ''Hidden Evidence: The Story of Forensic Science and how it Helped to Solve 40 of the World's Toughest Crimes'' Quintet Publishing, London. . * Quinche, Nicolas, and Margot, Pierre, "Coulier, Paul-Jean (1824ŌĆō1890): A precursor in the history of fingermark detection and their potential use for identifying their source (1863)", ''Journal of forensic identification'' (Californie), 60 (2), MarchŌĆōApril 2010, pp. 129ŌĆō134. * Silverman, Mike; Thompson, Tony. ''Written in Blood: A History of Forensic Science''. 2014. * *

Forensic educational resources

* {{Authority control Forensic science, Applied sciences Criminology Heuristics Medical aspects of death Chromatography

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

to criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Can ...

and civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation

Criminal investigation is an applied science that involves the study of facts that are then used to inform criminal trials. A complete criminal investigation can include searching, interviews, interrogations, evidence collection and preservatio ...

, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal procedure

Criminal procedure is the adjudication process of the criminal law. While criminal procedure differs dramatically by jurisdiction, the process generally begins with a formal criminal charge with the person on trial either being free on bail or ...

. Forensic science is a broad field that includes; DNA analysis, fingerprint analysis, blood stain pattern analysis, firearms examination and ballistics, tool mark analysis, serology, toxicology, hair and fiber analysis, entomology, questioned documents, anthropology, odontology, pathology, epidemiology, footwear and tire tread analysis, drug chemistry, paint and glass analysis, digital audio video and photo analysis.

Forensic scientists collect, preserve, and analyze scientific evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports this proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the supported proposition is true. What role evidence plays and how it is conceived varies from field to field.

In epistemology, evidenc ...

during the course of an investigation. While some forensic scientists travel to the scene of the crime to collect the evidence themselves, others occupy a laboratory role, performing analysis on objects brought to them by other individuals. Still others are involved in analysis of financial, banking, or other numerical data for use in financial crime investigation, and can be employed as consultants from private firms, academia, or as government employees.

In addition to their laboratory role, forensic scientists testify as expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

es in both criminal and civil cases and can work for either the prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal trial ...

or the defense. While any field could technically be ''forensic'', certain sections have developed over time to encompass the majority of forensically related cases.

Etymology

The word ''forensic'' comes from the Latin term ', meaning "of or before the forum". The history of the term originates in Roman times, when a criminal charge meant presenting the case before a group of public individuals in theforum

Forum or The Forum (plural forums or fora) may refer to:

Common uses

* Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

*Internet ...

. Both the person accused of the crime and the accuser would give speeches based on their sides of the story. The case would be decided in favor of the individual with the best argument and delivery. This origin is the source of the two modern usages of the word ''forensic''ŌĆöas a form of legal evidence; and as a category of public presentation.

In modern use, the term ''forensics'' is often used in place of "forensic science."

The word "science", is derived from the Latin word for 'knowledge' and is today closely tied to the scientific method, a systematic way of acquiring knowledge. Taken together, forensic science means the use of the scientific methods and processes for crime solving.

History

Origins of forensic science and early methods

Theancient world

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

lacked standardized forensic practices, which enabled criminals to escape punishment. Criminal investigations and trials relied heavily on forced confessions and witness testimony

In law and in religion, testimony is a solemn attestation as to the truth of a matter.

Etymology

The words "testimony" and "testify" both derive from the Latin word ''testis'', referring to the notion of a disinterested third-party witness.

La ...

. However, ancient sources do contain several accounts of techniques that foreshadow concepts in forensic science developed centuries later.

The first written account of using medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

and entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

to solve criminal cases is attributed to the book of ''Xi Yuan Lu'' (translated as ''Washing Away of Wrongs''), written in China in 1248 by Song Ci

Song Ci (; 1186ŌĆō1249) was a Chinese physician, judge, forensic medical scientist, anthropologist, and writer of the Southern Song dynasty. He is most well known for being the world's first forensic entomologist, having recorded his experienc ...

(Õ«ŗµģł, 1186ŌĆō1249), a director of justice, jail and supervision, during the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960ŌĆō1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

.

Song Ci introduced regulations concerning autopsy reports to court, how to protect the evidence in the examining process, and explained why forensic workers must demonstrate impartiality to the public. He devised methods for making antiseptic and for promoting the reappearance of hidden injuries to dead bodies and bones (using sunlight and vinegar under a red-oil umbrella); for calculating the time of death (allowing for weather and insect activity); described how to wash and examine the dead body to ascertain the reason for death. At that time the book had described methods for distinguishing between suicide and faked suicide.

In one of Song Ci's accounts (''Washing Away of Wrongs''), the case of a person murdered with a sickle was solved by an investigator who instructed each suspect to bring his sickle to one location. (He realized it was a sickle by testing various blades on an animal carcass and comparing the wounds.) Flies, attracted by the smell of blood, eventually gathered on a single sickle. In light of this, the owner of that sickle confessed to the murder. The book also described how to distinguish between a drowning

Drowning is a type of suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where others present are either unaware of the victim's situation or unable to offer a ...

(water in the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of th ...

) and strangulation

Strangling is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain. Fatal strangling typically occurs in cases of violence, accidents, and is one of two main ways that hanging ...

(broken neck cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck an ...

), and described evidence from examining corpses to determine if a death was caused by murder, suicide or accident.

Methods from around the world involved saliva and examination of the mouth and tongue to determine innocence or guilt, as a precursor to the Polygraph test

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a person is asked an ...

. In ancient India, some suspects were made to fill their mouths with dried rice and spit it back out. Similarly, in ancient China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, those accused of a crime would have rice powder placed in their mouths. In ancient middle-eastern

The Middle East ( ar, ž¦┘äž┤ž▒┘é ž¦┘䞯┘łž│žĘ, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europea ...

cultures, the accused were made to lick hot metal rods briefly. It is thought that these tests had some validity since a guilty person would produce less saliva and thus have a drier mouth; the accused would be considered guilty if rice was sticking to their mouths in abundance or if their tongues were severely burned due to lack of shielding from saliva.

Development of forensic science

In 16th-century Europe, medical practitioners in army and university settings began to gather information on the cause and

In 16th-century Europe, medical practitioners in army and university settings began to gather information on the cause and manner of death

In many legal jurisdictions, the manner of death is a determination, typically made by the coroner, medical examiner, police, or similar officials, and recorded as a vital statistic. Within the United States and the United Kingdom, a distinc ...

. Ambroise Par├®

Ambroise Par├® (c. 1510 ŌĆō 20 December 1590) was a French barber surgeon who served in that role for kings Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. He is considered one of the fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology and a p ...

, a French army surgeon

In modern medicine, a surgeon is a medical professional who performs surgery. Although there are different traditions in different times and places, a modern surgeon usually is also a licensed physician or received the same medical training as ...

, systematically studied the effects of violent death on internal organs. Two Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

surgeons, Fortunato Fidelis and Paolo Zacchia, laid the foundation of modern pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

by studying changes that occurred in the structure of the body as the result of disease. In the late 18th century, writings on these topics began to appear. These included ''A Treatise on Forensic Medicine and Public Health'' by the French physician Francois Immanuele Fod├®r├® and ''The Complete System of Police Medicine'' by the German medical expert Johann Peter Frank.

As the rational values of the Enlightenment era

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufkl├żrung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, O┼øwiecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustraci├│n, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

increasingly permeated society in the 18th century, criminal investigation became a more evidence-based, rational procedure ŌłÆ the use of torture to force confessions was curtailed, and belief in witchcraft and other powers of the occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

largely ceased to influence the court's decisions. Two examples of English forensic science in individual legal proceedings demonstrate the increasing use of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

and procedure in criminal investigations at the time. In 1784, in Lancaster, John Toms was tried and convicted for murdering Edward Culshaw with a pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, an ...

. When the dead body of Culshaw was examined, a pistol wad (crushed paper used to secure powder and balls in the muzzle) found in his head wound matched perfectly with a torn newspaper found in Toms's pocket, leading to the conviction.

In

In Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

1816, a farm laborer was tried and convicted of the murder of a young maidservant. She had been drowned in a shallow pool and bore the marks of violent assault. The police found footprints and an impression from corduroy cloth with a sewn patch in the damp earth near the pool. There were also scattered grains of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

and chaff. The breeches of a farm labourer who had been threshing wheat nearby were examined and corresponded exactly to the impression in the earth near the pool.

An article appearing in Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it i ...

in 1885 describes the use of microscopy to distinguish between the blood of two persons in a criminal case in Chicago.

Toxicology

A method for detecting arsenious oxide, simplearsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, but ...

, in corpses was devised in 1773 by the Swedish chemist, Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 ŌĆō 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hydrog ...

. His work was expanded upon, in 1806, by German chemist Valentin Ross, who learned to detect the poison in the walls of a victim's stomach.

James Marsh was the first to apply this new science to the art of forensics. He was called by the prosecution in a murder trial to give evidence as a chemist in 1832. The defendant, John Bodle, was accused of poisoning his grandfather with arsenic-laced coffee. Marsh performed the standard test by mixing a suspected sample with hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The unde ...

and hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

. While he was able to detect arsenic as yellow arsenic trisulfide

Arsenic trisulfide is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a dark yellow solid that is insoluble in water. It also occurs as the mineral orpiment (Latin: auripigmentum), which has been used as a pigment called King's yellow. It is produ ...

, when it was shown to the jury it had deteriorated, allowing the suspect to be acquitted due to reasonable doubt.

Annoyed by that, Marsh developed a much better test. He combined a sample containing arsenic with sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

and arsenic-free zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

, resulting in arsine

Arsine (IUPAC name: arsane) is an inorganic compound with the formula As H3. This flammable, pyrophoric, and highly toxic pnictogen hydride gas is one of the simplest compounds of arsenic. Despite its lethality, it finds some applications in ...

gas. The gas was ignited, and it decomposed to pure metallic arsenic, which, when passed to a cold surface, would appear as a silvery-black deposit. So sensitive was the test, known formally as the Marsh test

The Marsh test is a highly sensitive method in the detection of arsenic, especially useful in the field of forensic toxicology when arsenic was used as a poison. It was developed by the chemist James Marsh and first published in 1836. The metho ...

, that it could detect as little as one-fiftieth of a milligram of arsenic. He first described this test in ''The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal'' in 1836.

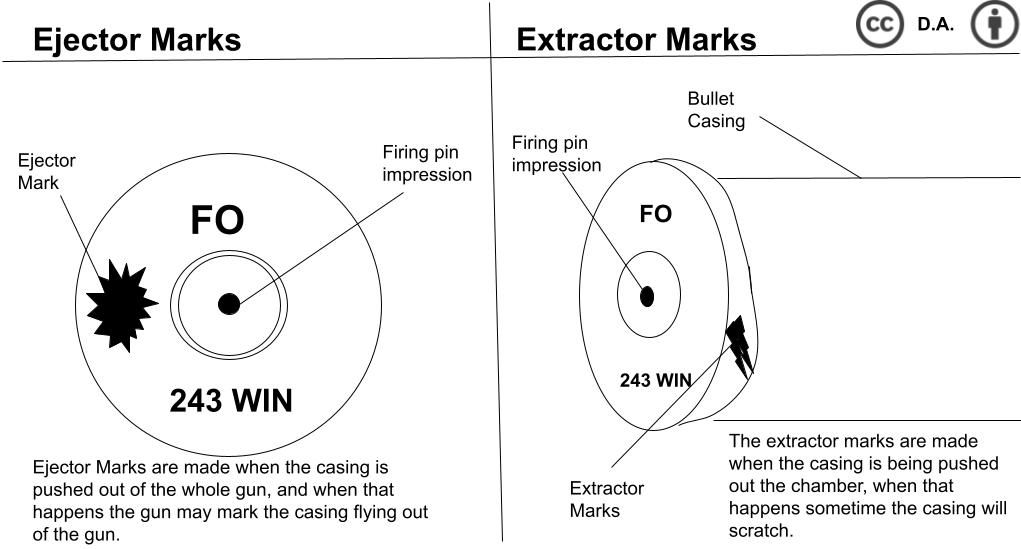

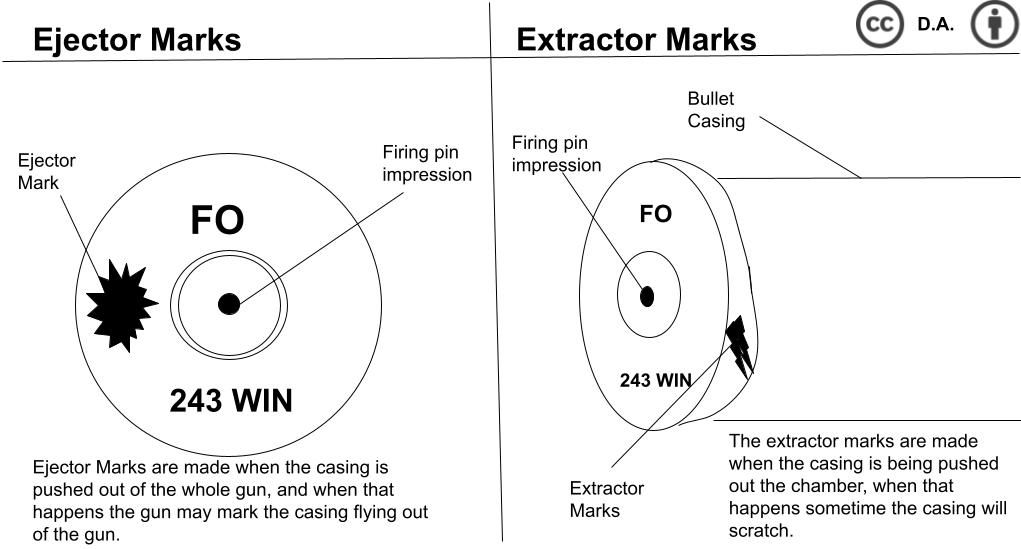

Ballistics

Henry Goddard atScotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

pioneered the use of bullet comparison in 1835. He noticed a flaw in the bullet that killed the victim and was able to trace this back to the mold that was used in the manufacturing process.

Anthropometry

The French police officerAlphonse Bertillon

Alphonse Bertillon (; 22 April 1853 ŌĆō 13 February 1914) was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement creating an identification system based on physical me ...

was the first to apply the anthropological technique of anthropometry

Anthropometry () refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthropology and in various atte ...

to law enforcement, thereby creating an identification system based on physical measurements. Before that time, criminals could be identified only by name or photograph.Kirsten Moana Thompson, ''Crime Films: Investigating the Scene''. London: Wallflower Press (2007): 10 Dissatisfied with the ''ad hoc'' methods used to identify captured criminals in France in the 1870s, he began his work on developing a reliable system of anthropometrics for human classification.

Bertillon created many other forensics

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and crimina ...

techniques, including forensic document examination

In forensic science, questioned document examination (QDE) is the examination of documents potentially disputed in a court of law. Its primary purpose is to provide evidence about a suspicious or questionable document using scientific processes a ...

, the use of galvanoplastic

Electrotyping (also galvanoplasty) is a chemical method for forming metal parts that exactly reproduce a model. The method was invented by Moritz von Jacobi in Russia in 1838, and was immediately adopted for applications in printing and several o ...

compounds to preserve footprint

Footprints are the impressions or images left behind by a person walking or running. Hoofprints and pawprints are those left by animals with hooves or paws rather than feet, while "shoeprints" is the specific term for prints made by shoes. The ...

s, ballistics

Ballistics is the field of mechanics concerned with the launching, flight behaviour and impact effects of projectiles, especially ranged weapon munitions such as bullets, unguided bombs, rockets or the like; the science or art of designing and a ...

, and the dynamometer

A dynamometer or "dyno" for short, is a device for simultaneously measuring the torque and rotational speed (RPM) of an engine, motor or other rotating prime mover so that its instantaneous power may be calculated, and usually displayed by the ...

, used to determine the degree of force used in breaking and entering

Burglary, also called breaking and entering and sometimes housebreaking, is the act of entering a building or other areas without permission, with the intention of committing a criminal offence. Usually that offence is theft, robbery or murder ...

. Although his central methods were soon to be supplanted by fingerprinting

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfac ...

, "his other contributions like the mug shot

A mug shot or mugshot (an informal term for police photograph or booking photograph) is a photographic portrait of a person from the shoulders up, typically taken after a person is arrested. The original purpose of the mug shot was to allow law e ...

and the systematization of crime-scene photography remain in place to this day."

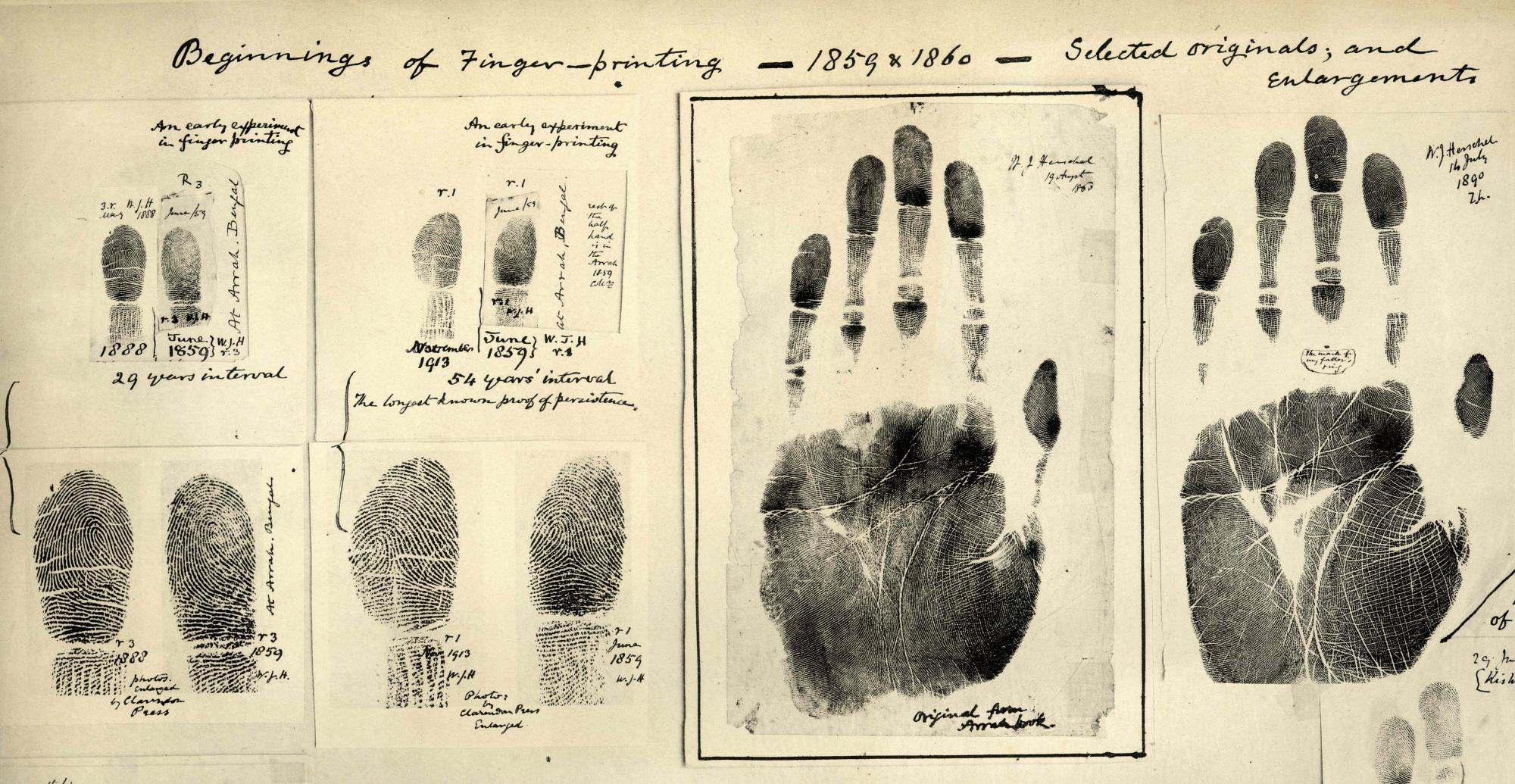

Fingerprints

SirWilliam Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 ŌĆō 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline H ...

was one of the first to advocate the use of fingerprinting in the identification of criminal suspects. While working for the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million ...

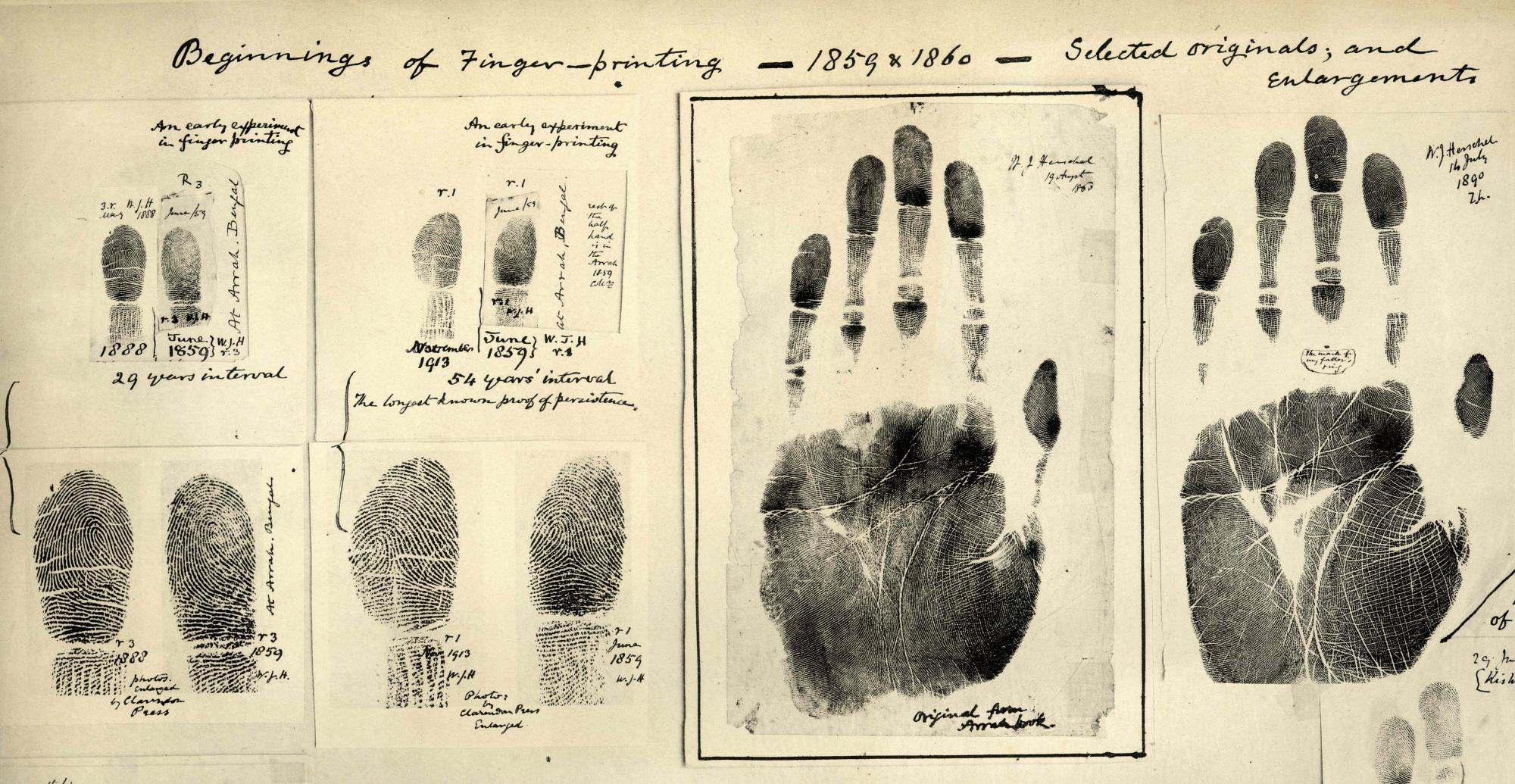

, he began to use thumbprints on documents as a security measure to prevent the then-rampant repudiation of signatures in 1858.

In 1877 at Hooghly (near Kolkata), Herschel instituted the use of fingerprints on contracts and deeds, and he registered government pensioners' fingerprints to prevent the collection of money by relatives after a pensioner's death.

In 1880, Dr.

In 1877 at Hooghly (near Kolkata), Herschel instituted the use of fingerprints on contracts and deeds, and he registered government pensioners' fingerprints to prevent the collection of money by relatives after a pensioner's death.

In 1880, Dr. Henry Faulds

Henry Faulds (1 June 1843 ŌĆō 24 March 1930) was a Scottish doctor, missionary and scientist who is noted for the development of fingerprinting.

Early life

Faulds was born in Beith, North Ayrshire, into a family of modest means. Aged 13, he wa ...

, a Scottish surgeon in a Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, µØ▒õ║¼, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, µØ▒õ║¼ķāĮ, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

hospital, published his first paper on the subject in the scientific journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'', discussing the usefulness of fingerprints for identification and proposing a method to record them with printing ink. He established their first classification and was also the first to identify fingerprints left on a vial. Returning to the UK in 1886, he offered the concept to the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

in London, but it was dismissed at that time. See also this on-line article on Henry Faulds:

Faulds wrote to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 ŌĆō 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

with a description of his method, but, too old and ill to work on it, Darwin gave the information to his cousin, Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 ŌĆō 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

, who was interested in anthropology. Having been thus inspired to study fingerprints for ten years, Galton published a detailed statistical model of fingerprint analysis and identification and encouraged its use in forensic science in his book ''Finger Prints''. He had calculated that the chance of a "false positive" (two different individuals having the same fingerprints) was about 1 in 64 billion.

Juan Vucetich, an Argentine chief police officer, created the first method of recording the fingerprints of individuals on file. In 1892, after studying Galton's pattern types, Vucetich set up the world's first fingerprint bureau. In that same year, Francisca Rojas of

Juan Vucetich, an Argentine chief police officer, created the first method of recording the fingerprints of individuals on file. In 1892, after studying Galton's pattern types, Vucetich set up the world's first fingerprint bureau. In that same year, Francisca Rojas of Necochea

Necochea is a port and beach city in the southwest of Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. The city is located on the Atlantic coast, along the mouth of the Quequ├®n Grande River, from Buenos Aires and southwest of Mar del Plata. The city proper ...

was found in a house with neck injuries whilst her two sons were found dead with their throats cut. Rojas accused a neighbour, but despite brutal interrogation, this neighbour would not confess to the crimes. Inspector Alvarez, a colleague of Vucetich, went to the scene and found a bloody thumb mark on a door. When it was compared with Rojas' prints, it was found to be identical with her right thumb. She then confessed to the murder of her sons.

A Fingerprint Bureau was established in Calcutta (Kolkata

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comme ...

), India, in 1897, after the Council of the Governor General approved a committee report that fingerprints should be used for the classification of criminal records. Working in the Calcutta Anthropometric Bureau, before it became the Fingerprint Bureau, were Azizul Haque and Hem Chandra Bose

Rai Bahadur Hem Chandra Bose ( bn, Ó”╣Ó¦ćÓ”«Ó”ÜÓ”©Ó¦ŹÓ””Ó¦ŹÓ”░ Ó”¼Ó”ĖÓ¦ü) was an Indian police officer and mathematician at the Calcutta Anthropometric Bureau (later the Fingerprint Bureau). Supervised by Edward Henry, he and Azizul Haque devel ...

. Haque and Bose were Indian fingerprint experts who have been credited with the primary development of a fingerprint classification system eventually named after their supervisor, Sir Edward Richard Henry. The Henry Classification System, co-devised by Haque and Bose, was accepted in England and Wales when the first United Kingdom Fingerprint Bureau was founded in Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

, the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

headquarters, London, in 1901. Sir Edward Richard Henry subsequently achieved improvements in dactyloscopy.

In the United States, Dr. Henry P. DeForrest used fingerprinting in the New York Civil Service in 1902, and by December 1905, New York City Police Department

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

Deputy Commissioner Joseph A. Faurot, an expert in the Bertillon Bertillon is a French surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alphonse Bertillon (1853ŌĆō1914), French police officer and biometrics researcher

* Jacques Bertillon

Jacques Bertillon (11 November 1851 – 4 July 1922) was a French ...

system and a fingerprint advocate at Police Headquarters, introduced the fingerprinting of criminals to the United States.

Uhlenhuth test

TheUhlenhuth test The Uhlenhuth test, also referred to as the antigenŌĆōantibody precipitin test for species, is a test which can determine the species of a blood sample. It was invented by Paul Uhlenhuth in 1901, based on the discovery that the blood of different sp ...

, or the antigenŌĆōantibody precipitin

A precipitin is an antibody which can precipitate out of a solution upon antigen binding.

Precipitin reaction

The precipitin reaction provided the first quantitative assay for antibody. The precipitin reaction is based upon the interaction of an ...

test for species, was invented by Paul Uhlenhuth

Paul Theodor Uhlenhuth (7 January 1870 in Hanover – 13 December 1957 in Freiburg im Breisgau) was a German bacteriologist and immunologist, and Professor at the University of Strasbourg (1911ŌĆō1918), at the University of Marburg (1918ŌĆō192 ...

in 1901 and could distinguish human blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

from animal blood, based on the discovery that the blood of different species had one or more characteristic proteins. The test represented a major breakthrough and came to have tremendous importance in forensic science. The test was further refined for forensic use by the Swiss chemist Maurice M├╝ller in the year 1960s.

DNA

Forensic DNA analysis was first used in 1984. It was developed by SirAlec Jeffreys

Sir Alec John Jeffreys, (born 9 January 1950) is a British geneticist known for developing techniques for genetic fingerprinting and DNA profiling which are now used worldwide in forensic science to assist police detective work and to resolv ...

, who realized that variation in the genetic sequence could be used to identify individuals and to tell individuals apart from one another. The first application of DNA profiles was used by Jefferys in a double murder mystery in the small English town of Narborough, Leicestershire

Narborough is a large village and civil parish in the Blaby district of Leicestershire, England, around southwest of Leicester. The population of the civil parish (including Littlethorpe) was 8,498.

The name is derived from the Old English ...

, in 1985. A 15-year-old school girl by the name of Lynda Mann was raped and murdered in Carlton Hayes psychiatric hospital. The police did not find a suspect but were able to obtain a semen sample.

In 1986, Dawn Ashworth, 15 years old, was also raped and strangled in the nearby village of Enderby. Forensic evidence showed that both killers had the same blood type. Richard Buckland became the suspect because he worked at Carlton Hayes psychiatric hospital, had been spotted near Dawn Ashworth's murder scene and knew unreleased details about the body. He later confessed to Dawn's murder but not Lynda's. Jefferys was brought into the case to analyze the semen samples. He concluded that there was no match between the samples and Buckland, who became the first person to be exonerated using DNA. Jefferys confirmed that the DNA profiles were identical for the two murder semen samples. To find the perpetrator, DNA samples from the entire male population, more than 4,000 aged from 17 to 34, of the town were collected. They all were compared to semen samples from the crime. A friend of Colin Pitchfork

Colin Pitchfork (born March 23, 1960) is a British double child-murderer and rapist. He was the first person convicted of rape and murder using DNA profiling after he murdered two girls in neighbouring Leicestershire villages, the first in Nar ...

was heard saying that he had given his sample to the police claiming to be Colin. Colin Pitchfork was arrested in 1987 and it was found that his DNA profile matched the semen samples from the murder.

Because of this case, DNA databases were developed. There is the national (FBI) and international databases as well as the European countries (ENFSI : European Network of Forensic Science Institutes). These searchable databases are used to match crime scene DNA profiles to those already in a database.

Maturation

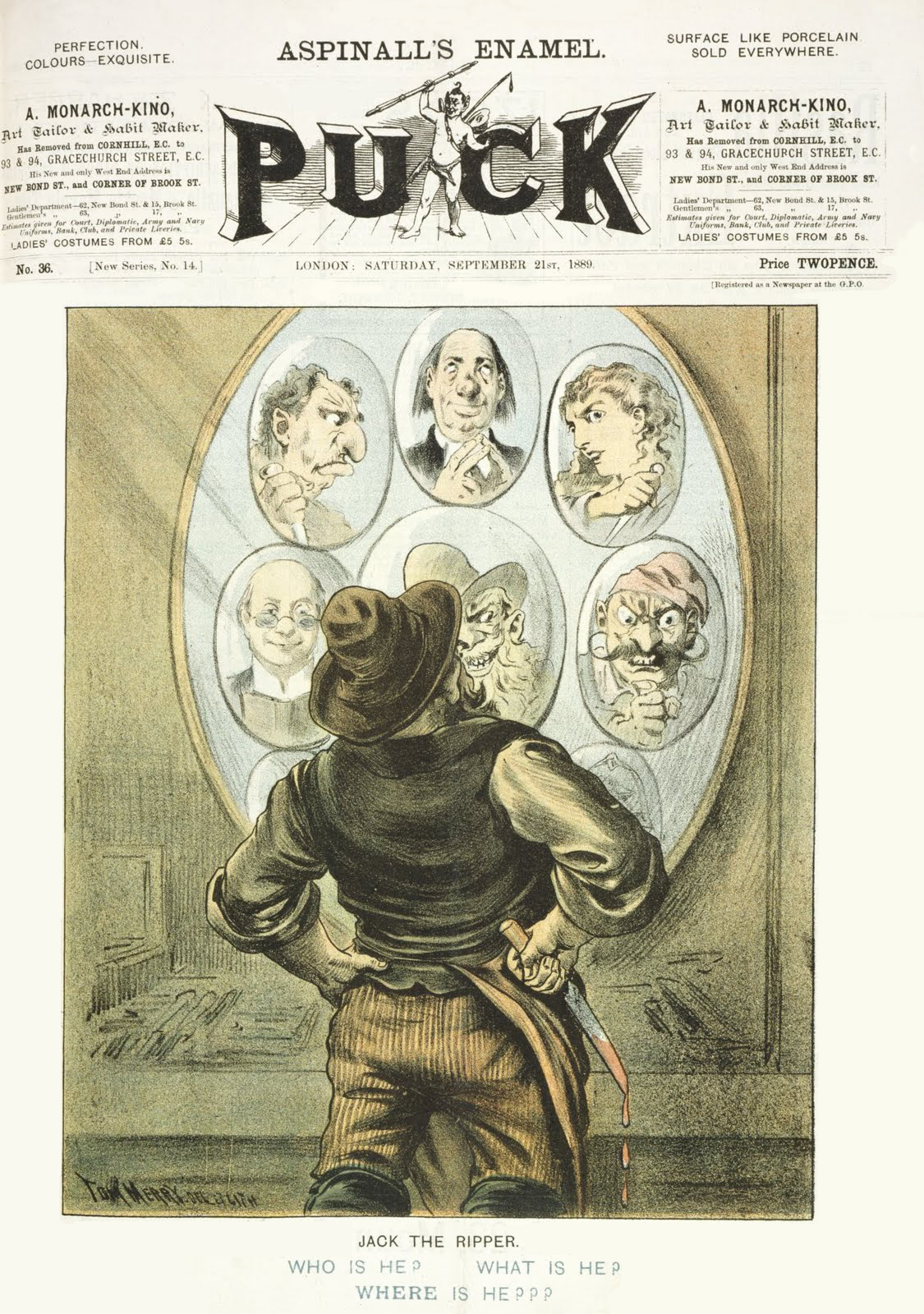

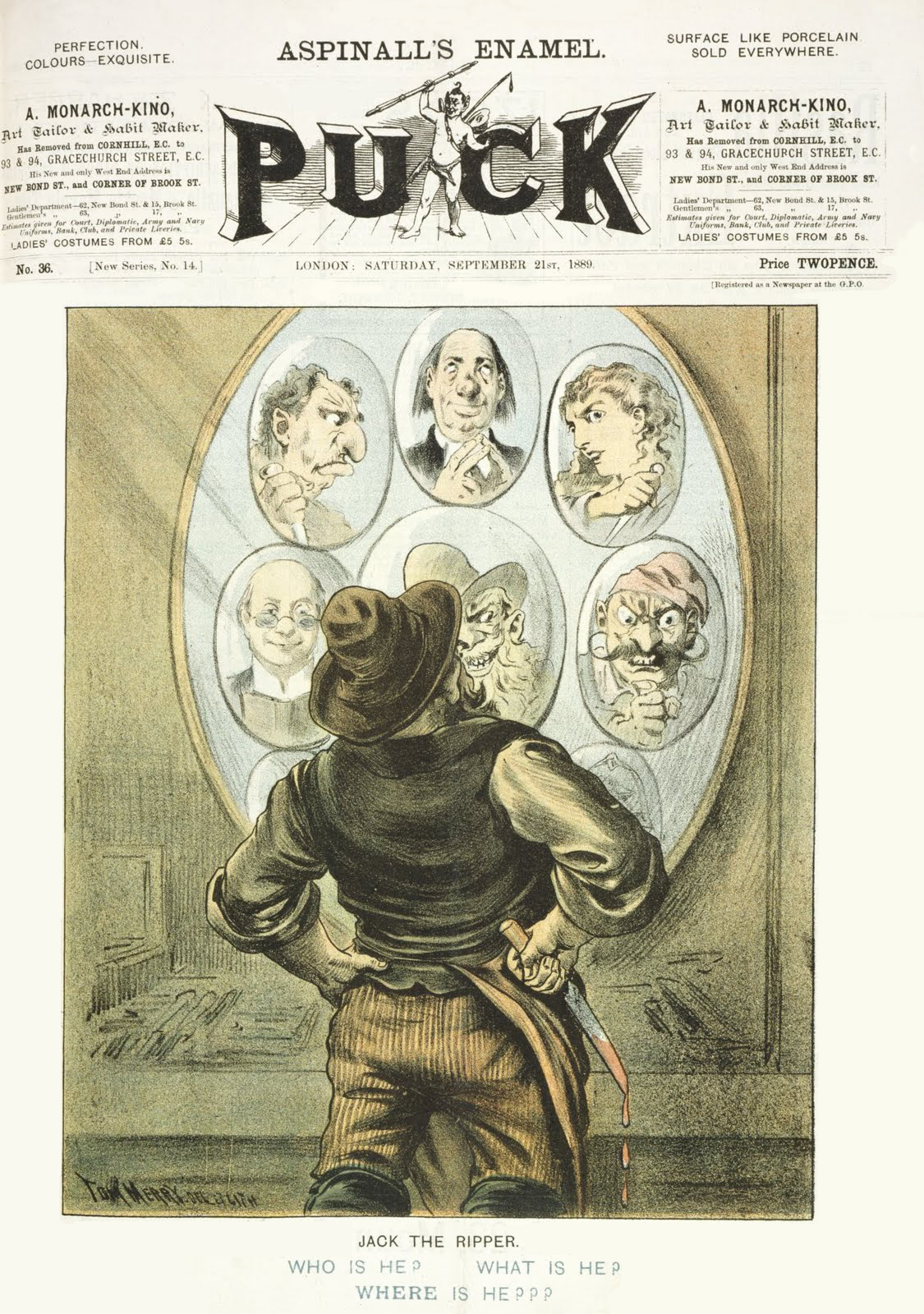

By the turn of the 20th century, the science of forensics had become largely established in the sphere of criminal investigation. Scientific and surgical investigation was widely employed by the

By the turn of the 20th century, the science of forensics had become largely established in the sphere of criminal investigation. Scientific and surgical investigation was widely employed by the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

during their pursuit of the mysterious Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

, who had killed a number of women in the 1880s. This case is a watershed in the application of forensic science. Large teams of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries throughout Whitechapel. Forensic material was collected and examined. Suspects were identified, traced and either examined more closely or eliminated from the inquiry. Police work follows the same pattern today. Canter, David (1994), ''Criminal Shadows: Inside the Mind of the Serial Killer'', London: HarperCollins, pp. 12ŌĆō13, Over 2000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained.

The investigation was initially conducted by the Criminal Investigation Department

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) is the branch of a police force to which most plainclothes detectives belong in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth nations. A force's CID is distinct from its Special Branch (though officers of b ...

(CID), headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid

Detective Inspector Edmund John James Reid (21 March 1846 – 5 December 1917) was the head of the CID in the Metropolitan Police's H Division at the time of the Whitechapel murders of Jack the Ripper in 1888. He was also an early aeronaut.' ...

. Later, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline (8 January 1843 ŌĆō 10 December 1929) was a British chief inspector for the London Metropolitan Police. He is best known for being a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper serial killer ...

, Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 ŌĆō 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

to assist. Initially, butchers, surgeons and physicians were suspected because of the manner of the mutilations. The alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry. Some contemporary figures thought the pattern of the murders indicated that the culprit was a butcher or cattle drover on one of the cattle boats that plied between London and mainland Europe. Whitechapel was close to the London Docks

London Docklands is the riverfront and former docks in London. It is located in inner east and southeast London, in the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Lewisham, Newham, and Greenwich. The docks were formerly part of the Port of L ...

, and usually such boats docked on Thursday or Friday and departed on Saturday or Sunday. The cattle boats were examined, but the dates of the murders did not coincide with a single boat's movements, and the transfer of a crewman between boats was also ruled out.

At the end of October, Robert Anderson asked police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer's surgical skill and knowledge. The opinion offered by Bond on the character of the "Whitechapel murderer" is the earliest surviving offender profile.Canter, pp. 5ŌĆō6 Bond's assessment was based on his own examination of the most extensively mutilated victim and the post mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

notes from the four previous canonical murders.Letter from Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner, ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook'', pp. 360ŌĆō362 and Rumbelow, pp. 145ŌĆō147 In his opinion the killer must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to "periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania

Mania, also known as manic syndrome, is a mental and behavioral disorder defined as a state of abnormally elevated arousal, affect, and energy level, or "a state of heightened overall activation with enhanced affective expression together wit ...

", with the character of the mutilations possibly indicating "satyriasis

Hypersexuality is extremely frequent or suddenly increased libido. It is controversial whether it should be included as a clinical diagnosis used by mental healthcare professionals. Nymphomania and satyriasis were terms previously used for the c ...

". Bond also stated that "the homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of the mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease but I do not think either hypothesis is likely".

''Handbook for Coroners, police officials, military policemen'' was written by the

''Handbook for Coroners, police officials, military policemen'' was written by the Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

criminal jurist Hans Gross

Hans Gustav Adolf Gross or Gro├¤ (26 December 1847 ŌĆō 9 December 1915) was an Austrian criminal jurist and criminologist, the "Founding Father" of criminal profiling. A criminal jurist, Gross made a mark as the creator of the field of criminal ...

in 1893, and is generally acknowledged as the birth of the field of criminalistics. The work combined in one system fields of knowledge that had not been previously integrated, such as psychology and physical science, and which could be successfully used against crime. Gross adapted some fields to the needs of criminal investigation, such as crime scene photography

Forensic photography may refer to the visual documentation of different aspects that can be found at a crime scene. It may include the documentation of the crime scene, or physical evidence that is either found at a crime scene or already proce ...

. He went on to found the Institute of Criminalistics in 1912, as part of the University of Graz' Law School. This Institute was followed by many similar institutes all over the world.

In 1909, Archibald Reiss

Rodolphe Archibald Reiss (8 July 1875 ŌĆō 7 August 1929) was a GermanŌĆōSwiss criminology-pioneer, forensic scientist, professor and writer.

Early life and studies

The Reiss family was in agriculture and winemaking. Archibald was the eighth o ...

founded the ''Institut de police scientifique'' of the University of Lausanne (UNIL), the first school of forensic science in the world. Dr. Edmond Locard

Dr. Edmond Locard (13 December 1877 ŌĆō 4 May 1966) was a French criminologist, the pioneer in forensic science who became known as the "Sherlock Holmes of France". He formulated the basic principle of forensic science: "Every contact leaves a ...

, became known as the "Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

". He formulated the basic principle of forensic science: "Every contact leaves a trace", which became known as Locard's exchange principle

In forensic science, Locard's principle holds that the perpetrator of a crime will bring something into the crime scene and leave with something from it, and that both can be used as forensic evidence. Dr. Edmond Locard (1877ŌĆō1966) was a pione ...

. In 1910, he founded what may have been the first criminal laboratory in the world, after persuading the Police Department of Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lion├®s'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rh├┤ne and Sa├┤ne, to the northwest of t ...

(France) to give him two attic rooms and two assistants.

Symbolic of the newfound prestige of forensics and the use of reasoning in detective work was the popularity of the fictional character Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

, written by Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 ŌĆō 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

in the late 19th century. He remains a great inspiration for forensic science, especially for the way his acute study of a crime scene yielded small clues as to the precise sequence of events. He made great use of trace evidence

Trace evidence is created when objects make contact. The material is often transferred by heat or induced by contact friction.

The importance of trace evidence in criminal investigations was shown by Dr. Edmond Locard in the early 20th century. ...

such as shoe and tire impressions, as well as fingerprints, ballistics

Ballistics is the field of mechanics concerned with the launching, flight behaviour and impact effects of projectiles, especially ranged weapon munitions such as bullets, unguided bombs, rockets or the like; the science or art of designing and a ...

and handwriting analysis

Graphology is the analysis of handwriting with attempt to determine someone's personality traits. No scientific evidence exists to support graphology, and it is generally considered a pseudoscience or scientifically questionable practice. Howe ...

, now known as questioned document examination. Such evidence is used to test theories conceived by the police, for example, or by the investigator himself. All of the techniques advocated by Holmes later became reality, but were generally in their infancy at the time Conan Doyle was writing. In many of his reported cases, Holmes frequently complains of the way the crime scene has been contaminated by others, especially by the police, emphasising the critical importance of maintaining its integrity, a now well-known feature of crime scene examination. He used analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry studies and uses instruments and methods to separate, identify, and quantify matter. In practice, separation, identification or quantification may constitute the entire analysis or be combined with another method. Separati ...

for blood residue

Blood residue are the wet and dry remnants of blood, as well the discoloration of surfaces on which blood has been shed. In forensic science, blood residue can help investigators identify weapons, reconstruct a criminal action, and link suspects t ...

analysis as well as toxicology

Toxicology is a scientific discipline, overlapping with biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and medicine, that involves the study of the adverse effects of chemical substances on living organisms and the practice of diagnosing and treating expo ...

examination and determination for poisons. He used ballistics

Ballistics is the field of mechanics concerned with the launching, flight behaviour and impact effects of projectiles, especially ranged weapon munitions such as bullets, unguided bombs, rockets or the like; the science or art of designing and a ...

by measuring bullet calibres and matching them with a suspected murder weapon.

Late 19th ŌĆō early 20th century figures

Hans Gross applied scientific methods to crime scenes and was responsible for the birth of criminalistics.

Hans Gross applied scientific methods to crime scenes and was responsible for the birth of criminalistics.

Edmond Locard

Dr. Edmond Locard (13 December 1877 ŌĆō 4 May 1966) was a French criminologist, the pioneer in forensic science who became known as the "Sherlock Holmes of France". He formulated the basic principle of forensic science: "Every contact leaves a ...

expanded on Gross' work with Locard's Exchange Principle which stated "whenever two objects come into contact with one another, materials are exchanged between them". This means that every contact by a criminal leaves a trace.

Alexander Lacassagne, who taught Locard, produced autopsy standards on actual forensic cases.

Alphonse Bertillon was a French criminologist and founder of Anthropometry (scientific study of measurements and proportions of the human body). He used anthropometry for identification, stating that, since each individual is unique, by measuring aspects of physical difference there could be a personal identification system. He created the Bertillon System around 1879, a way of identifying criminals and citizens by measuring 20 parts of the body. In 1884, over 240 repeat offenders were caught using the Bertillon system, but the system was largely superseded by fingerprinting.

Frances Glessner Lee, known as "the mother of forensic science", was instrumental in the development of forensic science in the US. She lobbied to have coroners replaced by medical professionals, endowed the Harvard Associates in Police Science, and conducted many seminars to educate homicide investigators. She also created the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, intricate crime scene dioramas used to train investigators, which are still in use today.

20th century

Later in the 20th century several British pathologists, Mikey Rochman, Francis Camps,

Later in the 20th century several British pathologists, Mikey Rochman, Francis Camps, Sydney Smith

Sydney Smith (3 June 1771 ŌĆō 22 February 1845) was an English wit, writer, and Anglican cleric.

Early life and education

Born in Woodford, Essex, England, Smith was the son of merchant Robert Smith (1739ŌĆō1827) and Maria Olier (1750ŌĆō1801) ...

and Keith Simpson pioneered new forensic science methods. Alec Jeffreys

Sir Alec John Jeffreys, (born 9 January 1950) is a British geneticist known for developing techniques for genetic fingerprinting and DNA profiling which are now used worldwide in forensic science to assist police detective work and to resolv ...

pioneered the use of DNA profiling

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's DNA characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is called DNA barcoding.

DNA profiling is a forensic tec ...

in forensic science in 1984. He realized the scope of DNA fingerprinting, which uses variations in the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

to identify individuals. The method has since become important in forensic science to assist police detective work, and it has also proved useful in resolving paternity and immigration disputes. DNA fingerprinting was first used as a police forensic test to identify the rapist and killer of two teenagers, Lynda Mann and Dawn Ashworth, who were both murdered in Narborough, Leicestershire

Narborough is a large village and civil parish in the Blaby district of Leicestershire, England, around southwest of Leicester. The population of the civil parish (including Littlethorpe) was 8,498.

The name is derived from the Old English ...

, in 1983 and 1986 respectively. Colin Pitchfork

Colin Pitchfork (born March 23, 1960) is a British double child-murderer and rapist. He was the first person convicted of rape and murder using DNA profiling after he murdered two girls in neighbouring Leicestershire villages, the first in Nar ...

was identified and convicted of murder after samples taken from him matched semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Semen i ...

samples taken from the two dead girls.

Forensic science has been fostered by a number of national and international forensic science learned bodies including the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences Chartered may refer to:

* Charter, a legal document conferring rights or privileges

** University charter

** Chartered company

* Chartered (professional), a professional credential

* Charter (shipping)

* Charter (airlines)

* Charter (typeface)

* Ch ...

, (founded 1959), then known as the Forensic Science Society, publisher of ''Science & Justice

''Science & Justice'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal of forensics published by Elsevier on behalf of the Forensic Science Society and the International Society for Forensic Genetics. The journal was established in 1960 as the ''Journal o ...

''; American Academy of Forensic Sciences

The American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS) is a society for forensic science professionals, and was founded in 1948. The society is based in Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA. The AAFS is a multi-disciplinary professional organization that p ...

(founded 1948), publishers of the ''Journal of Forensic Sciences

The ''Journal of Forensic Sciences'' (''JFS'') is a bimonthly peer-reviewed scientific journal is the official publication of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, published by Wiley-Blackwell. It covers all aspects of forensic science. The mi ...

''; the Canadian Society of Forensic Science (founded 1953), publishers of the '' Journal of the Canadian Society of Forensic Science''; the British Academy of Forensic Sciences (founded 1960), publishers of '' Medicine, Science and the Law''; the Australian Academy of Forensic Sciences

The Australian Academy of Forensic Sciences is a multi-disciplinary learned society founded in 1967 modelled on the British Academy of Forensic Sciences. The Academy conducts regular conferences, undertakes liaison with other Australian professi ...

(founded 1967), publishers of the ''Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences''; and the European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (founded 1995).

21st century

In the past decade, documenting forensics scenes has become more efficient. Forensic scientists have started using laser scanners, drones and photogrammetry to obtain 3D point clouds of accidents or crime scenes. Reconstruction of an accident scene on a highway using drones involves data acquisition time of only 10ŌĆō20 minutes and can be performed without shutting down traffic. The results are not just accurate, in centimeters, for measurement to be presented in court but also easy to digitally preserve in the long term. Now, in the 21st century, much of forensic science's future is up for discussion. TheNational Institute of Standards and Technology

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

(NIST) has offered the community some guidelines upon which the science should build. NIST recommends that forensic science rethinks its system. If local laboratories abide by these guidelines, 21st century forensics will be dramatically different from what it has been up to now. One of the more recent additions by NIST is a document called NISTIR-7941, titled "Forensic Science Laboratories: Handbook for Facility Planning, Design, Construction, and Relocation". The handbook provides a clear blueprint for approaching forensic science. The details even include what type of staff should be hired for certain positions.

Subdivisions

*Art forensics

Art forgery is the creating and selling of works of art which are falsely credited to other, usually more famous artists. Art forgery can be extremely lucrative, but modern dating and analysis techniques have made the identification of forged art ...

concerns the art authentication cases to help research the work's authenticity. Art authentication methods are used to detect and identify forgery, faking and copying of art works, e.g. paintings.

* Bloodstain pattern analysis

Bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA) is the field of forensic science that consists of the study and analysis of bloodstains at a known or suspected crime scene with the purpose of drawing conclusions about the nature, timing and other details of the ...

is the scientific examination of blood spatter patterns found at a crime scene to reconstruct the events of the crime.

* Comparative forensics is the application of visual comparison techniques to verify similarity of physical evidence. This includes fingerprint analysis, toolmark analysis, and ballistic analysis.

* Computational forensics Computational criminology is an interdisciplinary field which uses computing science methods to formally define criminology concepts, improve our understanding of complex phenomena, and generate solutions for related problems.

Methods

Computing sci ...

concerns the development of algorithms and software to assist forensic examination.

* Criminalistics

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and crimina ...

is the application of various sciences to answer questions relating to examination and comparison of biological evidence, trace evidence

Trace evidence is created when objects make contact. The material is often transferred by heat or induced by contact friction.

The importance of trace evidence in criminal investigations was shown by Dr. Edmond Locard in the early 20th century. ...

, impression evidence (such as fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfac ...

s, footwear impressions, and tire tracks), controlled substance

A controlled substance is generally a drug or chemical whose manufacture, possession and use is regulated by a government, such as illicitly used drugs or prescription medications that are designated by law. Some treaties, notably the Single ...

s, ballistics, firearm and toolmark examination, and other evidence in criminal investigations. In typical circumstances, evidence is processed in a crime lab.

* Digital forensics

Digital forensics (sometimes known as digital forensic science) is a branch of forensic science encompassing the recovery, investigation, examination and analysis of material found in digital devices, often in relation to mobile devices and co ...

is the application of proven scientific methods and techniques in order to recover data from electronic / digital media. Digital Forensic specialists work in the field as well as in the lab.

* Ear print analysis Ear print analysis is used as a means of forensic identification intended as an identification tool similar to fingerprinting. An ear print is a two-dimensional reproduction of the parts of the outer ear that have touched a specific surface (most co ...

is used as a means of forensic identification intended as an identification tool similar to fingerprinting. An earprint is a two-dimensional reproduction of the parts of the outer ear that have touched a specific surface (most commonly the helix, antihelix, tragus and antitragus).

* Election forensics

Election forensics are methods used to determine if election results are statistically normal or statistically abnormal, which can indicate electoral fraud. It uses statistical tools to determine if observed election results differ from normally ...

is the use of statistics to determine if election results are normal or abnormal. It is also used to look into and detect the cases concerning gerrymandering.

* Forensic accounting

Forensic accounting, forensic accountancy or financial forensics is the specialty practice area of accounting that investigates whether firms engage in financial reporting misconduct. Forensic accountants apply a range of skills and methods to d ...

is the study and interpretation of accounting evidence, financial statement namely: Balance sheet, Income statement, Cash flow statement.

* Forensic aerial photography is the study and interpretation of aerial photographic evidence.

* Forensic anthropology

Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification o ...

is the application of physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct Hominini, hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly ...

in a legal setting, usually for the recovery and identification of skeletonized human remains.

* Forensic archaeology

Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification o ...

is the application of a combination of archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

techniques and forensic science, typically in law enforcement.

* Forensic astronomy

Forensic astronomy is the use of astronomy, the scientific study of celestial objects, to determine the appearance of the sky at specific times in the past. This has been used, if relatively rarely, in forensic science (that is, for solving problem ...

uses methods from astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

to determine past celestial constellations for forensic purposes.

* Forensic botany is the study of plant life in order to gain information regarding possible crimes.

* Forensic chemistry

Forensic chemistry is the application of chemistry and its subfield, forensic toxicology, in a legal setting. A forensic chemist can assist in the identification of unknown materials found at a crime scene. Specialists in this field have a wid ...

is the study of detection and identification of illicit drugs

The prohibition of drugs through sumptuary legislation or religious law is a common means of attempting to prevent the recreational use of certain intoxicating substances.

While some drugs are illegal to possess, many governments regulate the ...

, accelerants used in arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

cases, explosive and gunshot residue

Gunshot residue (GSR), also known as cartridge discharge residue (CDR), gunfire residue (GFR), or firearm discharge residue (FDR), consists of all of the particles that are expelled from the muzzle of a gun following the discharge of a bullet. It ...

.

* Forensic dactyloscopy is the study of fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfac ...

s.

* Forensic document examination or questioned document examination answers questions about a disputed document using a variety of scientific processes and methods. Many examinations involve a comparison of the questioned document, or components of the document, with a set of known standards. The most common type of examination involves handwriting, whereby the examiner tries to address concerns about potential authorship.

* Forensic DNA analysis

DNA profiling is the determination of a DNA profile for legal and investigative purposes. DNA analysis methods have changed numerous times over the years as technology improves and allows for more information to be determined with less startin ...

takes advantage of the uniqueness of an individual's DNA to answer forensic questions such as paternity/maternity testing and placing a suspect at a crime scene, e.g. in a rape investigation

Rape investigation is the procedure to gather facts about a suspected rape, including forensic identification of a perpetrator, type of rape and other details.

The vast majority of rapes are committed by persons known to the victim: only betw ...

.

* Forensic engineering

Forensic engineering has been defined as ''"the investigation of failures - ranging from serviceability to catastrophic - which may lead to legal activity, including both civil and criminal".'' It includes the investigation of materials, product ...

is the scientific examination and analysis of structures and products relating to their failure or cause of damage.

* Forensic entomology

Forensic entomology is the scientific study of the colonization of a dead body by arthropods. This includes the study of insect types commonly associated with cadavers, their respective life cycles, their ecological presences in a given environme ...

deals with the examination of insects

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of j ...

in, on and around human remains to assist in determination of time or location of death. It is also possible to determine if the body was moved after death using entomology.

* Forensic geology

Forensic geology is the study of evidence relating to minerals, oil, petroleum, and other materials found in the Earth, used to answer questions raised by the legal system.

In 1975, Ray Murray and fellow Rutgers University professor John Tedrow ...

deals with trace evidence

Trace evidence is created when objects make contact. The material is often transferred by heat or induced by contact friction.

The importance of trace evidence in criminal investigations was shown by Dr. Edmond Locard in the early 20th century. ...

in the form of soils, minerals and petroleum.

* Forensic geomorphology is the study of the ground surface to look for potential location(s) of buried object(s).

* Forensic geophysics

Forensic geophysics is a branch of forensic science and is the study, the search, the localization and the mapping of buried objects or elements beneath the soil or the water, using geophysics tools for legal purposes. There are various geophysic ...

is the application of geophysical techniques such as radar for detecting objects hidden underground or underwater.

* Forensic intelligence

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to Criminal law, criminal and Civil law (legal system), civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standard ...

process starts with the collection of data and ends with the integration of results within into the analysis of crimes under investigation.

* Forensic interviews

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and crimina ...

are conducted using the science of professionally using expertise to conduct a variety of investigative interviews with victims, witnesses, suspects or other sources to determine the facts regarding suspicions, allegations or specific incidents in either public or private sector settings.

* Forensic histopathology is the application of histological techniques and examination to forensic pathology practice.

* Forensic limnology is the analysis of evidence collected from crime scenes in or around fresh-water sources. Examination of biological organisms, in particular diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, ╬┤╬╣╬¼Žä╬┐╬╝╬┐Žé, di├Ītomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, ╬┤╬╣╬▒Žä╬Ł╬╝╬ĮŽē, diat├®mno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising sev ...

s, can be useful in connecting suspects with victims.

* Forensic linguistics

Forensic linguistics, legal linguistics, or language and the law, is the application of linguistic knowledge, methods, and insights to the forensic context of law, language, crime investigation, trial, and judicial procedure. It is a branch of ap ...

deals with issues in the legal system that requires linguistic expertise.

* Forensic meteorology Forensic meteorology is meteorology, the scientific study of weather, applied to the process of reconstructing weather events for a certain time and location. This is done by acquiring and analyzing local weather reports such as surface observations ...

is a site-specific analysis of past weather conditions for a point of loss.

* Forensic microbiology

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to Criminal law, criminal and Civil law (legal system), civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standard ...

is the study of the necrobiome

The necrobiome has been defined as the community of species associated with decaying corpse remains. The process of decomposition is complex. Microbes decompose cadavers, but other organisms including fungi, nematodes, insects, and larger scavenger ...

.