Florence Nightengale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820 into a wealthy and well-connected British family at the ''Villa Colombaia'', in

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820 into a wealthy and well-connected British family at the ''Villa Colombaia'', in  In 1838, her father took the family on a tour in Europe where she was introduced to the English-born Parisian hostess Mary Clarke, with whom Florence bonded. She recorded that "Clarkey" was a stimulating hostess who did not care for her appearance, and while her ideas did not always agree with those of her guests, "she was incapable of boring anyone." Her behaviour was said to be exasperating and eccentric and she had little respect for upper-class British women, whom she regarded generally as inconsequential. She said that if given the choice between being a woman or a galley slave, then she would choose the freedom of the galleys. She generally rejected female company and spent her time with male intellectuals. Clarke made an exception, however, in the case of the Nightingale family and Florence in particular. She and Florence were to remain close friends for 40 years despite their 27-year age difference. Clarke demonstrated that women could be equals to men, an idea that Florence had not learnt from her mother.

Nightingale underwent the first of several experiences that she believed were calls from God in February 1837 while at

In 1838, her father took the family on a tour in Europe where she was introduced to the English-born Parisian hostess Mary Clarke, with whom Florence bonded. She recorded that "Clarkey" was a stimulating hostess who did not care for her appearance, and while her ideas did not always agree with those of her guests, "she was incapable of boring anyone." Her behaviour was said to be exasperating and eccentric and she had little respect for upper-class British women, whom she regarded generally as inconsequential. She said that if given the choice between being a woman or a galley slave, then she would choose the freedom of the galleys. She generally rejected female company and spent her time with male intellectuals. Clarke made an exception, however, in the case of the Nightingale family and Florence in particular. She and Florence were to remain close friends for 40 years despite their 27-year age difference. Clarke demonstrated that women could be equals to men, an idea that Florence had not learnt from her mother.

Nightingale underwent the first of several experiences that she believed were calls from God in February 1837 while at  As a young woman, Nightingale was described as attractive, slender, and graceful. While her demeanour was often severe, she was said to be very charming and to possess a radiant smile. Her most persistent suitor was the politician and poet

As a young woman, Nightingale was described as attractive, slender, and graceful. While her demeanour was often severe, she was said to be very charming and to possess a radiant smile. Her most persistent suitor was the politician and poet  Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and

Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the  Nightingale arrived at

Nightingale arrived at  During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as

During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as  According to some secondary sources, Nightingale had a frosty relationship with her fellow nurse Mary Seacole, who ran a hotel/hospital for officers. Seacole's own memoir, ''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'', records only one, friendly, meeting with her, when she asked her for a bed for the night, and got it; Seacole was in Scutari en route to the Crimea to join her business partner and start their business. However, Seacole pointed out that when she tried to join Nightingale's group, one of Nightingale's colleagues rebuffed her, and Seacole inferred that racism was at the root of that rebuttal. Nightingale told her brother-in-law, in a private letter, that she was worried about contact between her work and Seacole's business, claiming that while “she was very kind to the men and, what is more, to the Officers – and did some good (she) made many drunk”. Nightingale reportedly wrote, "I had the greatest difficulty in repelling Mrs. Seacole's advances, and in preventing association between her and my nurses (absolutely out of the question!)...Anyone who employs Mrs. Seacole will introduce much kindness – also much drunkenness and improper conduct". On the other hand, Seacole told the French chef

According to some secondary sources, Nightingale had a frosty relationship with her fellow nurse Mary Seacole, who ran a hotel/hospital for officers. Seacole's own memoir, ''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'', records only one, friendly, meeting with her, when she asked her for a bed for the night, and got it; Seacole was in Scutari en route to the Crimea to join her business partner and start their business. However, Seacole pointed out that when she tried to join Nightingale's group, one of Nightingale's colleagues rebuffed her, and Seacole inferred that racism was at the root of that rebuttal. Nightingale told her brother-in-law, in a private letter, that she was worried about contact between her work and Seacole's business, claiming that while “she was very kind to the men and, what is more, to the Officers – and did some good (she) made many drunk”. Nightingale reportedly wrote, "I had the greatest difficulty in repelling Mrs. Seacole's advances, and in preventing association between her and my nurses (absolutely out of the question!)...Anyone who employs Mrs. Seacole will introduce much kindness – also much drunkenness and improper conduct". On the other hand, Seacole told the French chef

''Beyond Nightingale: Nursing on the Crimean War Battlefields''

, Manchester University Press (2020) – Google Books

During the

During the

Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the first nursing school, the Nightingale Training School, at

Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the first nursing school, the Nightingale Training School, at  As

As  In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored

In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored

Although much of Nightingale's work improved the lot of women everywhere, Nightingale believed that women craved

Although much of Nightingale's work improved the lot of women everywhere, Nightingale believed that women craved

Florence Nightingale died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10

Florence Nightingale died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10

Florence Nightingale's autobiographical notes: A critical edition of BL Add. 45844 (England)

'' (M.A. thesis) Wilfrid Laurier University A memorial monument to Nightingale was created in

online article – see documents link at left

Indeed, Nightingale is described as "a true pioneer in the graphical representation of statistics", and is especially well-known for her usage of a Her attention turned to the health of the British Army in

Her attention turned to the health of the British Army in

Nightingale's lasting contribution has been her role in founding the modern nursing profession. She set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. The first official nurses' training programme, her

Nightingale's lasting contribution has been her role in founding the modern nursing profession. She set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. The first official nurses' training programme, her  The Nightingale Pledge is a modified version of the

The Nightingale Pledge is a modified version of the

A statue of Florence Nightingale by the 20th-century war memorialist Arthur George Walker stands in Waterloo Place,

A statue of Florence Nightingale by the 20th-century war memorialist Arthur George Walker stands in Waterloo Place,  A bronze plaque, attached to the plinth of the Crimean Memorial in the

A bronze plaque, attached to the plinth of the Crimean Memorial in the

In 2002, Nightingale was ranked number 52 in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote. In 2006, the Japanese public ranked Nightingale number 17 in The Top 100 Historical Persons in Japan.

Several churches in the Anglican Communion commemorate Nightingale with a feast day on their liturgical calendars. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates her as a Renewer of Society with Clara Maass on 13 August.

Washington National Cathedral celebrates Nightingale's accomplishments with a double-lancet stained glass window featuring six scenes from her life, designed by artist Joseph G. Reynolds and installed in 1983.

The United States Navy, US Navy ship the was commissioned in 1942. Beginning in 1968, the United States Air Force, US Air Force operated a fleet of 20 McDonnell Douglas C-9, C-9A "Nightingale" Medical evacuation, aeromedical evacuation aircraft, based on the McDonnell Douglas DC-9 platform. The last of these planes was retired from service in 2005.

In 1981, the asteroid 3122 Florence was named after her. A Dutch KLM McDonnell-Douglas MD-11 (registration PH-KCD) was also named in her honour; it served the airline for 20 years, from 1994 to 2014. Nightingale has appeared on international postage stamps, including, the UK, List of postage stamps of Alderney, Alderney, Australia, Belgium, Dominica, Hungary (showing the Florence Nightingale medal awarded by the International Red Cross), and Germany.

Florence Nightingale is Calendar of saints (Church of England), remembered in the

In 2002, Nightingale was ranked number 52 in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote. In 2006, the Japanese public ranked Nightingale number 17 in The Top 100 Historical Persons in Japan.

Several churches in the Anglican Communion commemorate Nightingale with a feast day on their liturgical calendars. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates her as a Renewer of Society with Clara Maass on 13 August.

Washington National Cathedral celebrates Nightingale's accomplishments with a double-lancet stained glass window featuring six scenes from her life, designed by artist Joseph G. Reynolds and installed in 1983.

The United States Navy, US Navy ship the was commissioned in 1942. Beginning in 1968, the United States Air Force, US Air Force operated a fleet of 20 McDonnell Douglas C-9, C-9A "Nightingale" Medical evacuation, aeromedical evacuation aircraft, based on the McDonnell Douglas DC-9 platform. The last of these planes was retired from service in 2005.

In 1981, the asteroid 3122 Florence was named after her. A Dutch KLM McDonnell-Douglas MD-11 (registration PH-KCD) was also named in her honour; it served the airline for 20 years, from 1994 to 2014. Nightingale has appeared on international postage stamps, including, the UK, List of postage stamps of Alderney, Alderney, Australia, Belgium, Dominica, Hungary (showing the Florence Nightingale medal awarded by the International Red Cross), and Germany.

Florence Nightingale is Calendar of saints (Church of England), remembered in the

File:Balaklava sick 2.jpg, A tinted lithograph by William Simpson (artist), William Simpson illustrating evacuation of the sick and injured from

''A Calendar of the Letters of Florence Nightingale''

Oxford: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1983. * McDonald, Lynn, ed.

''Collected Works of Florence Nightingale''

Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 16 volumes.

"Nightingale, Florence (1820–1910)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online ed., January 2011. * Mark Bostridge, Bostridge, Mark (2008), ''Florence Nightingale: The Woman and Her Legend''. Viking (2008), Penguin (2009). US title ''Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon''. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2008). * Vern Bullough, Bullough, Vern L.; Bonnie Bullough, Bullough, Bonnie; and Stanton, Marieta P., ''Florence Nightingale and Her Era: A Collection of New Scholarship'', New York, Garland, 1990. * Edward Chaney, Chaney, Edward (2006), "Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution," in ''Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines'', eds. Ascari, Maurizio, and Corrado, Adriana. Rodopi BV, Amsterdam and New York, 39–74. * Zachary Cope, Cope, Zachary, ''Florence Nightingale and the Doctors'', London: Museum Press, 1958; Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1958. * * Gillian Gill, Gill, Gillian (2004). ''Nightingales: The Extraordinary Upbringing and Curious Life of Miss Florence Nightingale''. Ballantine Books. * Magnello, M. Eileen. "Victorian statistical graphics and the iconography of Florence Nightingale's polar area graph," ''BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the British Society for the History of Mathematics'' (2012) 27#1 pp 13–37 * Nelson, Sioban, and Anne Marie Rafferty, Rafferty, Anne Marie, eds. ''Notes on Nightingale: The Influence and Legacy of a Nursing Icon'' (Cornell University Press; 2010) 184 pages. Essays on Nightingale's work in the Crimea and Britain's colonies, her links to the evolving science of statistics, and debates over her legacy and historical reputation and persona. * James Parton, Parton, James (1868). "Florence Nightingale," in ''Eminent Women of the Age; Being Narratives of the Lives and Deeds of the Most Prominent Women of the Present Generation'', Hartford, Conn.: S. M. Betts & Company. * Martin Pugh (author), Pugh, Martin, ''The March of the Women: A Revisionist Analysis of the Campaign for Women's Suffrage, 1866–1914'', Oxford (2000), at 55. * Joan Rees, Rees, Joan. ''Women on the Nile: Writings of Harriet Martineau, Florence Nightingale, and Amelia Edwards''. London: Rubicon Press (1995, 2008). * * * Sokoloff, Nancy Boyd, ''Three Victorian Women Who Changed their World: Josephine Butler, Octavia Hill, Florence Nightingale'', London: MacMillan (1982). * – available online a

Florence Nightingale: Part I. Strachey, Lytton. 1918. Eminent Victorians

* Webb, Val, ''The Making of a Radical Theologician'', Chalice Press (2002). * Cecil Woodham-Smith, Woodham-Smith, Cecil, ''Florence Nightingale'', Penguin (1951), rev. 1955.

1890 audio recording of Florence Nightingale speaking

Victorians.co.uk: Florence Nightingale

by Lytton Strachey *

University of Guelph: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale project

*

Florence Nightingale FoundationFlorence Nightingale Correspondence from the Historic Psychiatry Collection, Menninger Archives, Kansas Historical Society

Florence Nightingale Letters Collection

– A collection of letters written by and to Florence Nightingale from the UBC Library Digital Collections

Florence Nightingale Letters Collection

– correspondence in the University of Illinois at Chicago digital collections

Florence Nightingale Collection

at Wayne State University Library consists primarily of letters written by Florence Nightingale throughout her life. Major topics of the letters include medical care for the soldiers and the poor, the role of nursing, and sanitation and public works in colonized India.

Florence Nightingale Declaration Campaign for Global Health

established by the Nightingale Initiative for Global Health (NIGH) *

Papers of Florence Nightingale, 1820–1910

Episode 6: Florence Nightingale

fro

Babes of Science

podcasts

Texas Woman's University Special Collections

has a large collection of Florence Nightingale artefacts, letters, and primary sources. {{DEFAULTSORT:Nightingale, Florence Florence Nightingale, 1820 births 1910 deaths 19th-century English people 19th-century nurses 19th-century Christian universalists Anglican saints British women activists British people of the Crimean War British reformers English Christian theologians Dames of Grace of the Order of St John English Christian universalists Nurses from London English statisticians Fellows of the Royal Statistical Society Female wartime nurses Ladies of Grace of the Order of St John Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Royal Red Cross Nightingale family, Florence Nursing education Nursing researchers Nursing theorists People associated with King's College London History of the London Borough of Lambeth People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar People from Dethick, Lea and Holloway Women statisticians Nursing in the United Kingdom People from Test Valley British statisticians People from Florence

social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

, statistician and the founder of modern nursing

Nursing is a profession within the health care sector focused on the care of individuals, families, and communities so they may attain, maintain, or recover optimal health and quality of life. Nurses may be differentiated from other health ...

. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, in which she organised care for wounded soldiers at Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. She significantly reduced death rates by improving hygiene and living standards. Nightingale gave nursing a favourable reputation and became an icon of Victorian culture

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardi ...

, especially in the persona of "The Lady with the Lamp" making rounds of wounded soldiers at night.

Recent commentators have asserted that Nightingale's Crimean War achievements were exaggerated by the media at the time, but critics agree on the importance of her later work in professionalising nursing roles for women. In 1860, she laid the foundation of professional nursing with the establishment of her nursing school at St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS ...

in London. It was the first secular nursing school in the world and is now part of King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

. In recognition of her pioneering work in nursing, the Nightingale Pledge taken by new nurses, and the Florence Nightingale Medal

The Florence Nightingale Medal is an international award presented to those distinguished in nursing and named after British nurse Florence Nightingale. The medal was established in 1912 by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), f ...

, the highest international distinction a nurse can achieve, were named in her honour, and the annual International Nurses Day is celebrated on her birthday. Her social reforms included improving healthcare for all sections of British society, advocating better hunger relief in India, helping to abolish prostitution laws that were harsh for women, and expanding the acceptable forms of female participation in the workforce.

Nightingale was a pioneer in statistics; she represented her analysis in graphical forms to ease drawing conclusions and actionables from data. She is famous for usage of the polar area diagram

A pie chart (or a circle chart) is a circular statistical graphic, which is divided into slices to illustrate numerical proportion. In a pie chart, the arc length of each slice (and consequently its central angle and area) is proportional t ...

, also called the Nightingale rose diagram, equivalent to a modern circular histogram

A histogram is an approximate representation of the frequency distribution, distribution of numerical data. The term was first introduced by Karl Pearson. To construct a histogram, the first step is to "Data binning, bin" (or "Data binning, buck ...

. This diagram is still regularly used in data visualisation

Data and information visualization (data viz or info viz) is an interdisciplinary field that deals with the graphic representation of data and information. It is a particularly efficient way of communicating when the data or information is nu ...

.

Nightingale was a prodigious and versatile writer. In her lifetime, much of her published work was concerned with spreading medical knowledge. Some of her tracts were written in simple English so that they could easily be understood by those with poor literary skills. She was also a pioneer in data visualization with the use of infographic

Infographics (a clipped compound of "information" and "graphics") are graphic visual representations of information, data, or knowledge intended to present information quickly and clearly.Doug Newsom and Jim Haynes (2004). ''Public Relations Wr ...

s, using graphical presentations of statistical data in an effective way. Much of her writing, including her extensive work on religion and mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ...

, has only been published posthumously.

Early life

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820 into a wealthy and well-connected British family at the ''Villa Colombaia'', in

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820 into a wealthy and well-connected British family at the ''Villa Colombaia'', in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, Tuscany, Italy, and was named after the city of her birth. Florence's older sister Frances Parthenope had similarly been named after her place of birth, '' Parthenope'', a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

settlement now part of the city of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

. The family moved back to England in 1821, with Nightingale being brought up in the family's homes at Embley, Hampshire

Embley is a small village in the Test Valley district of Hampshire, England in the United Kingdom. Its nearest town is Romsey, which lies approximately 3.5 miles (4.8 km) east from the village. It is in the civil parish of Wellow.

A famous ...

, and Lea Hurst, Derbyshire.

Florence inherited a liberal-humanitarian outlook from both sides of her family. Her parents were William Edward Nightingale, born William Edward Shore (1794–1874) and Frances ("Fanny") Nightingale ( Smith; 1788–1880). William's mother Mary ( Evans) was the niece of Peter Nightingale, under the terms of whose will William inherited his estate at Lea Hurst, and assumed the name and arms of Nightingale. Fanny's father (Florence's maternal grandfather) was the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and Unitarian William Smith. Nightingale's father educated her.

A BBC documentary reported that "Florence and her older sister Parthenope benefited from their father's advanced ideas about women's education. They studied history, mathematics, Italian, classical literature, and philosophy, and from an early age Florence, who was the more academic of the two girls, displayed an extraordinary ability for collecting and analysing data which she would use to great effect in later life."

In 1838, her father took the family on a tour in Europe where she was introduced to the English-born Parisian hostess Mary Clarke, with whom Florence bonded. She recorded that "Clarkey" was a stimulating hostess who did not care for her appearance, and while her ideas did not always agree with those of her guests, "she was incapable of boring anyone." Her behaviour was said to be exasperating and eccentric and she had little respect for upper-class British women, whom she regarded generally as inconsequential. She said that if given the choice between being a woman or a galley slave, then she would choose the freedom of the galleys. She generally rejected female company and spent her time with male intellectuals. Clarke made an exception, however, in the case of the Nightingale family and Florence in particular. She and Florence were to remain close friends for 40 years despite their 27-year age difference. Clarke demonstrated that women could be equals to men, an idea that Florence had not learnt from her mother.

Nightingale underwent the first of several experiences that she believed were calls from God in February 1837 while at

In 1838, her father took the family on a tour in Europe where she was introduced to the English-born Parisian hostess Mary Clarke, with whom Florence bonded. She recorded that "Clarkey" was a stimulating hostess who did not care for her appearance, and while her ideas did not always agree with those of her guests, "she was incapable of boring anyone." Her behaviour was said to be exasperating and eccentric and she had little respect for upper-class British women, whom she regarded generally as inconsequential. She said that if given the choice between being a woman or a galley slave, then she would choose the freedom of the galleys. She generally rejected female company and spent her time with male intellectuals. Clarke made an exception, however, in the case of the Nightingale family and Florence in particular. She and Florence were to remain close friends for 40 years despite their 27-year age difference. Clarke demonstrated that women could be equals to men, an idea that Florence had not learnt from her mother.

Nightingale underwent the first of several experiences that she believed were calls from God in February 1837 while at Embley Park

Embley Park, in Wellow (near Romsey, Hampshire), was the family home of Florence Nightingale from 1825 until her death in 1910. It is also where Florence Nightingale claimed she had received her divine calling from God. It is now the location of ...

, prompting a strong desire to devote her life to the service of others. In her youth she was respectful of her family's opposition to her working as a nurse, only announcing her decision to enter the field in 1844. Despite the anger and distress of her mother and sister, she rejected the expected role for a woman of her status to become a wife and mother. Nightingale worked hard to educate herself in the art and science of nursing, in the face of opposition from her family and the restrictive social code for affluent young English women.

As a young woman, Nightingale was described as attractive, slender, and graceful. While her demeanour was often severe, she was said to be very charming and to possess a radiant smile. Her most persistent suitor was the politician and poet

As a young woman, Nightingale was described as attractive, slender, and graceful. While her demeanour was often severe, she was said to be very charming and to possess a radiant smile. Her most persistent suitor was the politician and poet Richard Monckton Milnes

Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, FRS (19 June 1809 – 11 August 1885) was an English poet, patron of literature and a politician who strongly supported social justice.

Background and education

Milnes was born in London, the son o ...

, but after a nine-year courtship, she rejected him, convinced that marriage would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing.

In Rome in 1847, she met Sidney Herbert, a politician who had been Secretary at War

The Secretary at War was a political position in the English and later British government, with some responsibility over the administration and organization of the Army, but not over military policy. The Secretary at War ran the War Office. Afte ...

(1845–1846) who was on his honeymoon. He and Nightingale became lifelong close friends. Herbert would be Secretary of War again during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

when he and his wife would be instrumental in facilitating Nightingale's nursing work in Crimea. She became Herbert's key adviser throughout his political career, though she was accused by some of having hastened Herbert's death from Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied ...

in 1861 because of the pressure her programme of reform placed on him. Nightingale also much later had strong relations with academic Benjamin Jowett

Benjamin Jowett (, modern variant ; 15 April 1817 – 1 October 1893) was an English tutor and administrative reformer in the University of Oxford, a theologian, an Anglican cleric, and a translator of Plato and Thucydides. He was Master of B ...

, who may have wanted to marry her.

Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and

Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and Selina Bracebridge

Selina Bracebridge (née Mills; 1800 – 1874) was a British artist, medical reformer, and travel writer.

Selina Bracebridge studied art under the celebrated artist Samuel Prout, and travelled widely as part of her art education.

She marri ...

) as far as Greece and Egypt. While in Athens, Greece, Nightingale rescued a juvenile little owl

The little owl (''Athene noctua''), also known as the owl of Athena or owl of Minerva, is a bird that inhabits much of the temperate and warmer parts of Europe, the Palearctic east to Korea, and North Africa. It was introduced into Britain at ...

from a group of children who were tormenting it, and she named the owl Athena. Nightingale often carried the owl in her pocket, until the pet died (soon before Nightingale left for Crimea).

Her writings on Egypt, in particular, are testimony to her learning, literary skill, and philosophy of life. Sailing up the Nile as far as Abu Simbel in January 1850, she wrote of the Abu Simbel temples

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel ( ar, أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is situated on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about s ...

, "Sublime in the highest style of intellectual beauty, intellect without effort, without suffering ... not a feature is correct — but the whole effect is more expressive of spiritual grandeur than anything I could have imagined. It makes the impression upon one that thousands of voices do, uniting in one unanimous simultaneous feeling of enthusiasm or emotion, which is said to overcome the strongest man."

At Thebes, she wrote of being "called to God", while a week later near Cairo she wrote in her diary (as distinct from her far longer letters that her elder sister Parthenope was to print after her return): "God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation." Later in 1850, she visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein in Germany, where she observed Pastor Theodor Fliedner

Theodor Fliedner (21 January 18004 October 1864) was a German Lutheran minister and founder of Lutheran deaconess training. In 1836, he founded Kaiserswerther Diakonie, a hospital and deaconess training center. Together with his wives Friederik ...

and the deaconesses working for the sick and the deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life, and issued her findings anonymously in 1851; ''The Institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, for the Practical Training of Deaconesses, etc.'' was her first published work. She also received four months of medical training at the institute, which formed the basis for her later care.

On 22 August 1853, Nightingale took the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street

Harley Street is a street in Marylebone, Central London, which has, since the 19th century housed a large number of private specialists in medicine and surgery. It was named after Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.

, London, a position she held until October 1854. (commercial website) Her father had given her an annual income of £500 (roughly £40,000/US$65,000 in present terms), which allowed her to live comfortably and to pursue her career.

Crimean War

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, which became her central focus when reports got back to Britain about the horrific conditions for the wounded at the military hospital on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

, opposite Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, at Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar

Üsküdar () is a large and densely populated district of Istanbul, Turkey, on the Anatolian shore of the Bosphorus. It is bordered to the north by Beykoz, to the east by Ümraniye, to the southeast by Ataşehir and to the south by Kadıköy; ...

in Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

). Britain and France entered the war against Russia on the side of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. On 21 October 1854, she and the staff of 38 women volunteer nurses including her head nurse Eliza Roberts and her aunt Mai Smith, and 15 Catholic nuns (mobilised by Henry Edward Manning

Henry Edward Manning (15 July 1808 – 14 January 1892) was an English prelate of the Catholic church, and the second Archbishop of Westminster from 1865 until his death in 1892. He was ordained in the Church of England as a young man, but conv ...

) were sent (under the authorisation of Sidney Herbert) to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. On the way, Nightingale was assisted in Paris by her friend Mary Clarke. The volunteer nurses worked about away from the main British camp across the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

at Balaklava

Balaklava ( uk, Балаклáва, russian: Балаклáва, crh, Balıqlava, ) is a settlement on the Crimean Peninsula and part of the city of Sevastopol. It is an administrative center of Balaklava Raion that used to be part of the Cri ...

, in the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

.

Nightingale arrived at

Nightingale arrived at Selimiye Barracks

Selimiye Barracks ( tr, Selimiye Kışlası), also known as Scutari Barracks, is a Turkish Army barracks located in the Üsküdar district on the Asian side of Istanbul, Turkey. It was originally built in 1800 by Sultan Selim III for the sol ...

in Scutari early in November 1854. Her team found that poor care for wounded soldiers was being delivered by overworked medical staff in the face of official indifference. Medicines were in short supply, hygiene

Hygiene is a series of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

was being neglected, and mass infections were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients.

After Nightingale sent a plea to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' for a government solution to the poor condition of the facilities, the British Government commissioned Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

to design a prefabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. The term ...

hospital that could be built in England and shipped to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. The result was Renkioi Hospital

Renkioi Hospital was a pioneering prefabricated building made of wood, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel as a British Army military hospital for use during the Crimean War.

Background

During 1854 Britain entered into the Crimean War, and th ...

, a civilian facility that, under the management of Edmund Alexander Parkes

Edmund Alexander Parkes (29 December 1819 – 15 March 1876) was an English physician, known as a hygienist, particularly in the military context.

Early life

Parkes was born at Bloxham in Oxfordshire, the son of William Parkes, of the Marble-yar ...

, had a death rate less than one tenth of that of Scutari.

Stephen Paget

Stephen Paget (17 July 1855 – 8 May 1926) was an English surgeon and pro-vivisection campaigner.Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' asserted that Nightingale reduced the death rate from 42% to 2%, either by making improvements in hygiene herself, or by calling for the Sanitary Commission. For example, Nightingale implemented handwashing

Hand washing (or handwashing), also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/ bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the hand ...

and other hygiene practices in the war hospital in which she worked.

During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as

During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

, typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

, and dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

than from battle wounds. With overcrowding, defective sewers and lack of ventilation, the Sanitary Commission had to be sent out by the British government to Scutari in March 1855, almost six months after Nightingale had arrived. The commission flushed out the sewers and improved ventilation. Death rates were sharply reduced, but she never claimed credit for helping to reduce the death rate. Head Nurse Eliza Roberts nursed Nightingale through her critical illness of May 1855.

In 2001 and 2008 the BBC released documentaries that were critical of Nightingale's performance in the Crimean War, as were some follow-up articles published in ''The Guardian'' and the ''Sunday Times''. Nightingale scholar Lynn McDonald has dismissed these criticisms as "often preposterous", arguing they are not supported by the primary sources.

Nightingale still believed that the death rates were due to poor nutrition, lack of supplies, stale air, and overworking of the soldiers. After she returned to Britain and began collecting evidence before the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army, she came to believe that most of the soldiers at the hospital were killed by poor living conditions. This experience influenced her later career when she advocated sanitary living conditions as of great importance. Consequently, she reduced peacetime deaths in the army and turned her attention to the sanitary design of hospitals and the introduction of sanitation in working-class homes (see Statistics and Sanitary Reform, below).

According to some secondary sources, Nightingale had a frosty relationship with her fellow nurse Mary Seacole, who ran a hotel/hospital for officers. Seacole's own memoir, ''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'', records only one, friendly, meeting with her, when she asked her for a bed for the night, and got it; Seacole was in Scutari en route to the Crimea to join her business partner and start their business. However, Seacole pointed out that when she tried to join Nightingale's group, one of Nightingale's colleagues rebuffed her, and Seacole inferred that racism was at the root of that rebuttal. Nightingale told her brother-in-law, in a private letter, that she was worried about contact between her work and Seacole's business, claiming that while “she was very kind to the men and, what is more, to the Officers – and did some good (she) made many drunk”. Nightingale reportedly wrote, "I had the greatest difficulty in repelling Mrs. Seacole's advances, and in preventing association between her and my nurses (absolutely out of the question!)...Anyone who employs Mrs. Seacole will introduce much kindness – also much drunkenness and improper conduct". On the other hand, Seacole told the French chef

According to some secondary sources, Nightingale had a frosty relationship with her fellow nurse Mary Seacole, who ran a hotel/hospital for officers. Seacole's own memoir, ''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'', records only one, friendly, meeting with her, when she asked her for a bed for the night, and got it; Seacole was in Scutari en route to the Crimea to join her business partner and start their business. However, Seacole pointed out that when she tried to join Nightingale's group, one of Nightingale's colleagues rebuffed her, and Seacole inferred that racism was at the root of that rebuttal. Nightingale told her brother-in-law, in a private letter, that she was worried about contact between her work and Seacole's business, claiming that while “she was very kind to the men and, what is more, to the Officers – and did some good (she) made many drunk”. Nightingale reportedly wrote, "I had the greatest difficulty in repelling Mrs. Seacole's advances, and in preventing association between her and my nurses (absolutely out of the question!)...Anyone who employs Mrs. Seacole will introduce much kindness – also much drunkenness and improper conduct". On the other hand, Seacole told the French chef Alexis Soyer

Alexis Benoît Soyer (4 February 18105 August 1858) was a French chef who became the most celebrated cook in Victorian England. He also tried to alleviate suffering of the Irish poor in the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), and contributed a p ...

that "You must know, M Soyer, that Miss Nightingale is very fond of me. When I passed through Scutari, she very kindly gave me board and lodging."

The arrival of two waves of Irish nuns, the Sisters of Mercy

The Sisters of Mercy is a religious institute of Catholic women founded in 1831 in Dublin, Ireland, by Catherine McAuley. As of 2019, the institute had about 6200 sisters worldwide, organized into a number of independent congregations. They a ...

to assist with nursing duties at Scutari met with different responses from Nightingale. Mary Clare Moore

Mother Mary Clare Moore (20 March 1814 – 13 December 1874) was an Irish Sister of Mercy, a Crimean War nurse and a teacher. She was one of the ten original members of the Sisters of Mercy, and was the founding sister superior of the order's fi ...

headed the first wave and placed herself and her Sisters under the authority of Nightingale. The two were to remain friends for the rest of their lives. The second wave, headed by Mary Francis Bridgeman met with a cooler reception as Bridgeman refused to give up her authority over her Sisters to Nightingale while at the same time not trusting Nightingale, whom she regarded as ambitious.Carol Helmstadter''Beyond Nightingale: Nursing on the Crimean War Battlefields''

, Manchester University Press (2020) – Google Books

The Lady with the Lamp

During the

During the Crimean war

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, Nightingale gained the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp" from a phrase in a report in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'':

The phrase was further popularised by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

's 1857 poem "Santa Filomena":

Lo! in that house of misery A lady with a lamp I see Pass through the glimmering gloom, And flit from room to room.

Later career

In theCrimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

on 29 November 1855, the Nightingale Fund was established for the training of nurses during a public meeting to recognise Nightingale for her work in the war. There was an outpouring of generous donations. Sidney Herbert served as honorary secretary of the fund and the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

was chairman. In her 1856 letters she described spas in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, detailing the health conditions, physical descriptions, dietary information, and other vital details of patients whom she directed there. She noted that the treatment there was significantly less expensive than in Switzerland.

Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the first nursing school, the Nightingale Training School, at

Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the first nursing school, the Nightingale Training School, at St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS ...

on 9 July 1860. The first trained Nightingale nurses began work on 16 May 1865 at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary. Now called the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery

The Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care is an academic faculty within King's College London. The faculty is the world's first nursing school to be continuously connected to a fully serving hospital and medic ...

, the school is part of King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

. In 1866 she said the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital

The Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital (colloquially called the Royal Bucks) is a private hospital in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. It is a Grade II listed building.

History

The hospital was established, by adding new wings to an 18th-century country ...

in Aylesbury

Aylesbury ( ) is the county town of Buckinghamshire, South East England. It is home to the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery, David Tugwell`s house on Watermead and the Waterside Theatre. It is in central Buckinghamshire, midway between High Wy ...

near her sister's home Claydon House

Claydon House is a country house in the Aylesbury Vale, Buckinghamshire, England, near the village of Middle Claydon. It was built between 1757 and 1771 and is now owned by the National Trust.

The house is a listed Grade I on the National Heri ...

would be "the most beautiful hospital in England", and in 1868 called it "an excellent model to follow".

Nightingale wrote '' Notes on Nursing'' (1859). The book served as the cornerstone of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools, though it was written specifically for the education of those nursing at home. Nightingale wrote, "Every day sanitary knowledge, or the knowledge of nursing, or in other words, of how to put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease, takes a higher place. It is recognised as the knowledge which every one ought to have – distinct from medical knowledge, which only a profession can have".

''Notes on Nursing'' also sold well to the general reading public and is considered a classic introduction to nursing. Nightingale spent the rest of her life promoting and organising the nursing profession. In the introduction to the 1974 edition, Joan Quixley of the Nightingale School of Nursing wrote: "The book was the first of its kind ever to be written. It appeared at a time when the simple rules of health were only beginning to be known, when its topics were of vital importance not only for the well-being and recovery of patients, when hospitals were riddled with infection, when nurses were still mainly regarded as ignorant, uneducated persons. The book has, inevitably, its place in the history of nursing, for it was written by the founder of modern nursing".

As

As Mark Bostridge

Mark Bostridge is a British writer and critic, known for his historical biographies.

He was educated at Westminster School and read Modern History at St Anne's College, Oxford, from 1979 to 1984. At Oxford, he was awarded the Gladstone Memorial P ...

has demonstrated, one of Nightingale's signal achievements was the introduction of trained nurses into the workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

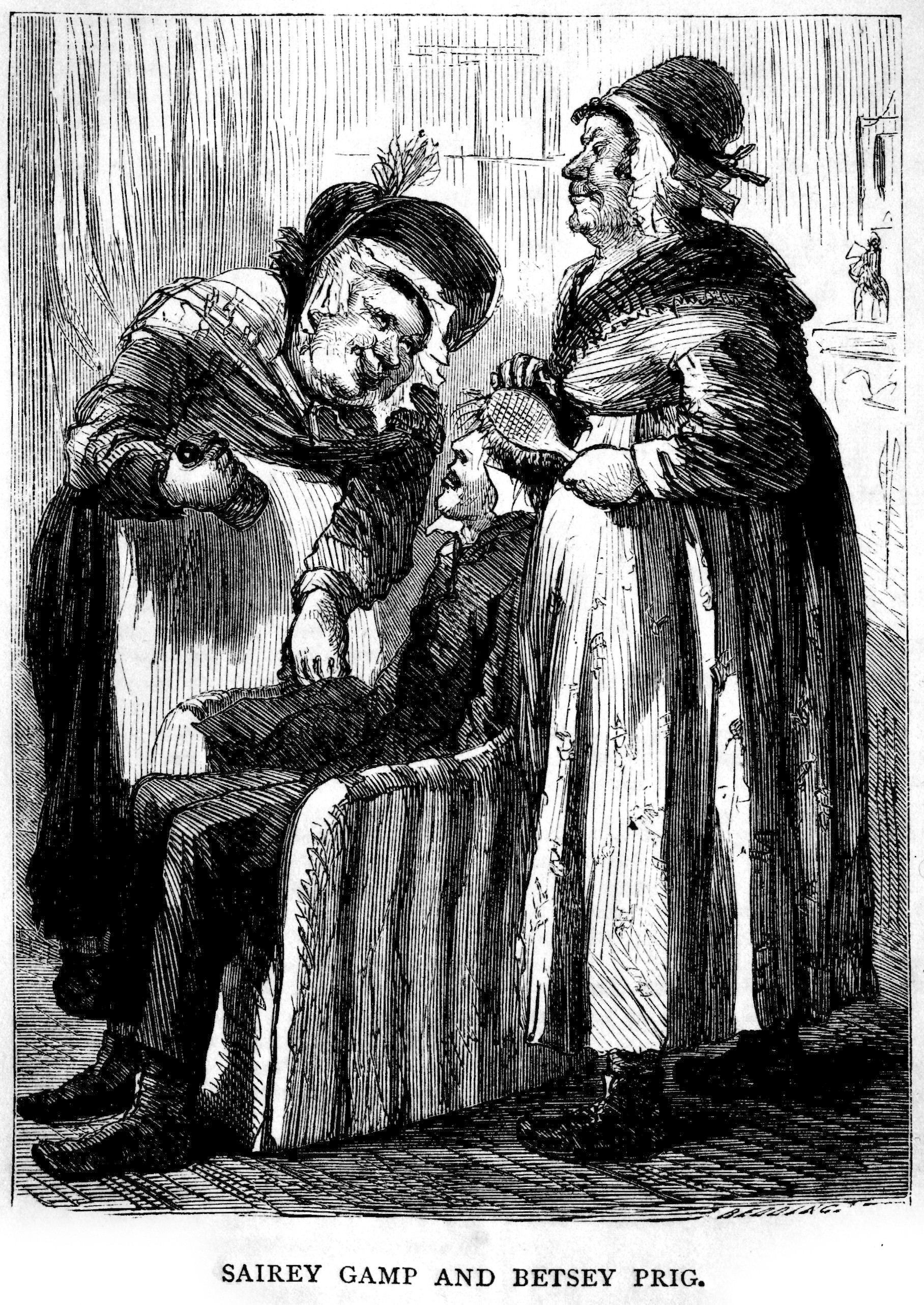

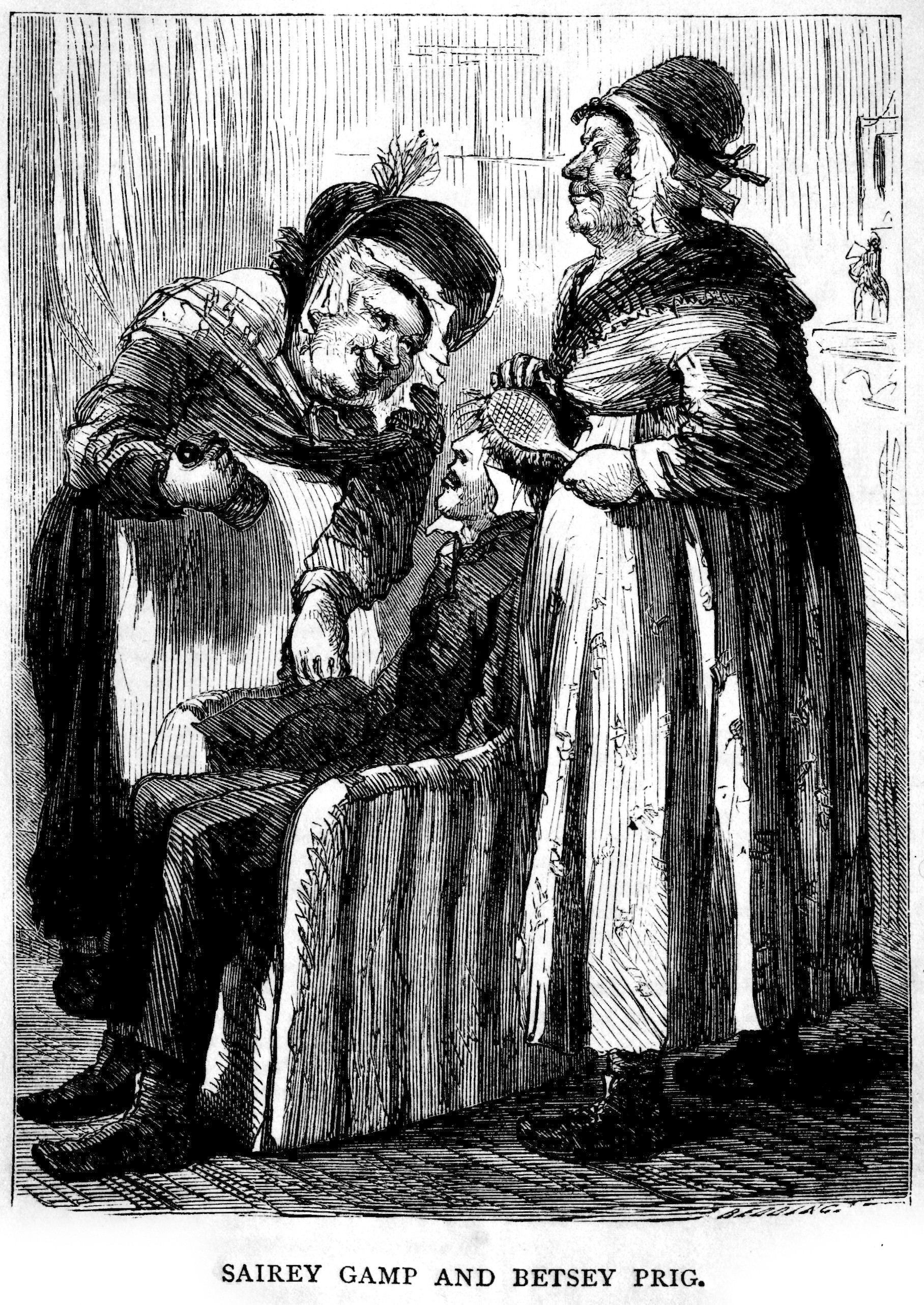

system in Britain from the 1860s onwards. This meant that sick paupers were no longer being cared for by other, able-bodied paupers, but by properly trained nursing staff. In the first half of the 19th century, nurses were usually former servants or widows who found no other job and therefore were forced to earn their living by this work. Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

caricatured the standard of care in his 1842–1843 published novel ''Martin Chuzzlewit

''The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit'' (commonly known as ''Martin Chuzzlewit'') is a novel by Charles Dickens, considered the last of his picaresque novels. It was originally serialised between 1842 and 1844. While he was writing it ...

'' in the figure of Sarah Gamp

Sarah or Sairey Gamp, Mrs. Gamp as she is more commonly known, is a nurse in the novel ''Martin Chuzzlewit'' by Charles Dickens, first published as a serial in 1843–1844.

Mrs. Gamp is dissolute, sloppy and generally drunk. She became a noto ...

as being incompetent, negligent, alcoholic and corrupt. According to Caroline Worthington, director of the Florence Nightingale Museum, "When she ightingalestarted out there was no such thing as nursing. The Dickens character Sarah Gamp, who was more interested in drinking gin than looking after her patients, was only a mild exaggeration. Hospitals were places of last resort where the floors were laid with straw to soak up the blood. Florence transformed nursing when she got back rom Crimea

Rom, or ROM may refer to:

Biomechanics and medicine

* Risk of mortality, a medical classification to estimate the likelihood of death for a patient

* Rupture of membranes, a term used during pregnancy to describe a rupture of the amniotic sac

* ...

She had access to people in high places and she used it to get things done. Florence was stubborn, opinionated, and forthright but she had to be those things in order to achieve all that she did."

Though Nightingale is sometimes said to have denied the theory of infection for her entire life, a 2008 biography disagrees,''Florence Nightingale, the Woman and her Legend'', by Mark Bostridge (Viking, 2008) saying that she was simply opposed to a precursor of germ theory known as contagionism. This theory held that diseases could only be transmitted by touch. Before the experiments of the mid-1860s by Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named after ...

and Lister, hardly anyone took germ theory seriously; even afterwards, many medical practitioners were unconvinced. Bostridge points out that in the early 1880s Nightingale wrote an article for a textbook in which she advocated strict precautions designed, she said, to kill germs. Nightingale's work served as an inspiration for nurses in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. The Union government approached her for advice in organising field medicine. Her ideas inspired the volunteer body of the United States Sanitary Commission

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the United States Army (Federal / Northern / Union Army) during the American Civil ...

.

In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored

In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored Linda Richards

Linda Richards (July 27, 1841 – April 16, 1930) was the first professionally trained American nurse. She established nursing training programs in the United States and Japan, and created the first system for keeping individual medical recor ...

, "America's first trained nurse", and enabled her to return to the United States with adequate training and knowledge to establish high-quality nursing schools. Richards went on to become a nursing pioneer in the US and Japan.

By 1882, several Nightingale nurses had become matrons at several leading hospitals, including, in London ( St Mary's Hospital, Westminster Hospital, St Marylebone Workhouse Infirmary and the Hospital for Incurables at Putney

Putney () is a district of southwest London, England, in the London Borough of Wandsworth, southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

History

Putney is an ancient paris ...

) and throughout Britain ( Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley

Netley, officially referred to as Netley Abbey, is a village on the south coast of Hampshire, England. It is situated to the south-east of the city of Southampton, and flanked on one side by the ruins of Netley Abbey and on the other by the R ...

; Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

; Cumberland Infirmary and Liverpool Royal Infirmary), as well as at Sydney Hospital

Sydney Hospital is a major hospital in Australia, located on Macquarie Street in the Sydney central business district. It is the oldest hospital in Australia, dating back to 1788, and has been at its current location since 1811. It first rece ...

in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Australia.

In 1883, Nightingale became the first recipient of the Royal Red Cross

The Royal Red Cross (RRC) is a military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth for exceptional services in military nursing.

Foundation

The award was established on 27 April 1883 by Queen Victoria, with a single class of Mem ...

. In 1904, she was appointed a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John (LGStJ).

In 1907, she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by ...

. In the following year she was given the Honorary Freedom of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

. Her birthday is now celebrated as International CFS CFS is an acronym for:

Organizations

* Canadian Federation of Students

* Canadian Forest Service

* Center for Financial Studies, a research institute affiliated with Goethe University Frankfurt

* Center for Subjectivity Research, a research insti ...

Awareness Day.

From 1857 onwards, Nightingale was intermittently bedridden and suffered from depression. A recent biography cites brucellosis

Brucellosis is a highly contagious zoonosis caused by ingestion of unpasteurized milk or undercooked meat from infected animals, or close contact with their secretions. It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.

The ...

and associated spondylitis

Spondylitis is an inflammation of the vertebrae. It is a form of spondylopathy. In many cases, spondylitis involves one or more vertebral joints, as well, which itself is called spondylarthritis.

__TOC__

Types

Pott disease is a tuberculous dis ...

as the cause. Most authorities today accept that Nightingale suffered from a particularly extreme form of brucellosis, the effects of which only began to lift in the early 1880s. Despite her symptoms, she remained phenomenally productive in social reform. During her bedridden years, she also did pioneering work in the field of hospital planning, and her work propagated quickly across Britain and the world. Nightingale's output slowed down considerably in her last decade. She wrote very little during that period due to blindness and declining mental abilities, though she still retained an interest in current affairs.

Relationships

Although much of Nightingale's work improved the lot of women everywhere, Nightingale believed that women craved

Although much of Nightingale's work improved the lot of women everywhere, Nightingale believed that women craved sympathy

Sympathy is the perception of, understanding of, and reaction to the distress or need of another life form. According to David Hume, this sympathetic concern is driven by a switch in viewpoint from a personal perspective to the perspective of an ...

and were not as capable as men. She criticised early women's rights activists for decrying an alleged lack of careers for women at the same time that lucrative medical positions, under the supervision of Nightingale and others, went perpetually unfilled. She preferred the friendship of powerful men, insisting they had done more than women to help her attain her goals, writing: "I have never found one woman who has altered her life by one iota for me or my opinions." She often referred to herself in the masculine, as for example "a man of action" and "a man of business".

However, she did have several important and long-lasting friendships with women. Later in life, she kept up a prolonged correspondence with Irish nun Sister Mary Clare Moore, with whom she had worked in Crimea. Her most beloved confidante was Mary Clarke, an Englishwoman she met in Paris in 1837 and kept in touch with throughout her life.

Some scholars of Nightingale's life believe that she remained chaste for her entire life, perhaps because she felt a religious calling to her career.

Death

Florence Nightingale died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10

Florence Nightingale died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10 South Street, Mayfair

South Street is a street in Mayfair, London, England. It runs west to east from Park Lane before merging into Farm Street.

Notable buildings include the private house, Aberconway House, listed for sale in 2007 by the developer and estate agent ...

, London, on 13 August 1910, at the age of 90. The offer of burial in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

was declined by her relatives and she is buried in the churchyard of St Margaret's Church in East Wellow

Wellow is a village and civil parish in Hampshire, England that falls within the Test Valley district. The village lies just outside the New Forest, across the main A36 road which runs from the M27 motorway to Salisbury. The nearest town is ...

, Hampshire, near Embley Park with a memorial with just her initials and dates of birth and death. She left a large body of work, including several hundred notes that were previously unpublished.Kelly, Heather (1998). Florence Nightingale's autobiographical notes: A critical edition of BL Add. 45844 (England)

'' (M.A. thesis) Wilfrid Laurier University A memorial monument to Nightingale was created in

Carrara marble

Carrara marble, Luna marble to the Romans, is a type of white or blue-grey marble popular for use in sculpture and building decor. It has been quarried since Roman times in the mountains just outside the city of Carrara in the province of Massa ...

by Francis William Sargant in 1913 and placed in the cloister of the Basilica of Santa Croce

The (Italian for 'Basilica of the Holy Cross') is the principal Franciscan church in Florence, Italy, and a minor basilica of the Roman Catholic Church. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 meters south-east of the Duomo. The ...

, in Florence, Italy.

Contributions

Statistics and sanitary reform

Florence Nightingale exhibited a gift for mathematics from an early age and excelled in the subject under the tutelage of her father. Later, Nightingale became a pioneer in the visual presentation of information andstatistical graphics

Statistical graphics, also known as statistical graphical techniques, are graphics used in the field of statistics for data visualization.

Overview

Whereas statistics and data analysis procedures generally yield their output in numeric or tabul ...

. She used methods such as the pie chart

A pie chart (or a circle chart) is a circular Statistical graphics, statistical graphic, which is divided into slices to illustrate numerical proportion. In a pie chart, the arc length of each slice (and consequently its central angle and are ...

, which had first been developed by William Playfair

William Playfair (22 September 1759 – 11 February 1823), a Scottish engineer and political economist, served as a secret agent on behalf of Great Britain during its war with France. The founder of graphical methods of statistics, Playfai ...

in 1801. While taken for granted now, it was at the time a relatively novel method of presenting data. (alternative pagination depending on country of sale: 98–107, bibliography on p. 114online article – see documents link at left

Indeed, Nightingale is described as "a true pioneer in the graphical representation of statistics", and is especially well-known for her usage of a

polar area diagram

A pie chart (or a circle chart) is a circular statistical graphic, which is divided into slices to illustrate numerical proportion. In a pie chart, the arc length of each slice (and consequently its central angle and area) is proportional t ...

, or occasionally the ''Nightingale rose diagram'', equivalent to a modern circular histogram

A histogram is an approximate representation of the frequency distribution, distribution of numerical data. The term was first introduced by Karl Pearson. To construct a histogram, the first step is to "Data binning, bin" (or "Data binning, buck ...

, to illustrate seasonal sources of patient mortality in the military field hospital she managed. While frequently credited as the creator of the polar area diagram, it is known to have been used by André-Michel Guerry in 1829 and Léon Louis Lalanne by 1830. Nightingale called a compilation of such diagrams a "coxcomb", but later that term would frequently be used for the individual diagrams. She made extensive use of coxcombs to present reports on the nature and magnitude of the conditions of medical care in the Crimean War to Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

and civil servants who would have been unlikely to read or understand traditional statistical reports. In 1859, Nightingale was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society

The Royal Statistical Society (RSS) is an established statistical society. It has three main roles: a British learned society for statistics, a professional body for statisticians and a charity which promotes statistics for the public good.

...

. In 1874 she became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association

The American Statistical Association (ASA) is the main professional organization for statisticians and related professionals in the United States. It was founded in Boston, Massachusetts on November 27, 1839, and is the second oldest continuousl ...

.

Her attention turned to the health of the British Army in

Her attention turned to the health of the British Army in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and she demonstrated that bad drainage, contaminated water, overcrowding, and poor ventilation were causing the high death rate. Following the report ''The Royal Commission on India'' (1858–1863), which included drawings done by her cousin, artist Hilary Bonham Carter, with whom Nightingale had lived, Nightingale concluded that the health of the army and the people of India had to go hand in hand and so campaigned to improve the sanitary conditions of the country as a whole.

Nightingale made a comprehensive statistical study of sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

in Indian rural life and was the leading figure in the introduction of improved medical care and public health service in India. In 1858 and 1859, she successfully lobbied for the establishment of a Royal Commission into the Indian situation. Two years later, she provided a report to the commission, which completed its own study in 1863. "After 10 years of sanitary reform, in 1873, Nightingale reported that mortality among the soldiers in India had declined from 69 to 18 per 1,000".

The Royal Sanitary Commission of 1868–1869 presented Nightingale with an opportunity to press for compulsory sanitation in private houses. She lobbied the minister responsible, James Stansfeld

Sir James Stansfeld, (; 5 March 182017 February 1898) was a British Radical and Liberal politician and social reformer who served as Under-Secretary of State for India (1866), Financial Secretary to the Treasury (1869–71) and President of ...

, to strengthen the proposed Public Health Bill to require owners of existing properties to pay for connection to mains drainage. The strengthened legislation was enacted in the Public Health Acts of 1874 and 1875. At the same time, she combined with the retired sanitary reformer Edwin Chadwick

Sir Edwin Chadwick KCB (24 January 18006 July 1890) was an English social reformer who is noted for his leadership in reforming the Poor Laws in England and instituting major reforms in urban sanitation and public health. A disciple of Uti ...

to persuade Stansfeld to devolve powers to enforce the law to Local Authorities, eliminating central control by medical technocrats. Her Crimean War statistics had convinced her that non-medical approaches were more effective given the state of knowledge at the time. Historians now believe that both drainage and devolved enforcement played a crucial role in increasing average national life expectancy by 20 years between 1871 and the mid-1930s during which time medical science made no impact on the most fatal epidemic diseases.

Literature and the women's movement

Historian of scienceI. Bernard Cohen

I. Bernard Cohen (1 March 1914 – 20 June 2003) was the Victor S. Thomas Professor of the history of science at Harvard University and the author of many books on the history of science and, in particular, Isaac Newton and Benjamin Franklin.

C ...

argues:

Lytton Strachey

Giles Lytton Strachey (; 1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was an English writer and critic. A founding member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of ''Eminent Victorians'', he established a new form of biography in which psychological insight ...

was famous for his book debunking 19th-century heroes, ''Eminent Victorians

''Eminent Victorians'' is a book by Lytton Strachey (one of the older members of the Bloomsbury Group), first published in 1918, and consisting of biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era. Its fame rests on the irreverence and ...

'' (1918). Nightingale gets a full chapter, but instead of debunking her, Strachey praised her in a way that raised her national reputation and made her an icon for English feminists of the 1920s and 1930s.

While better known for her contributions in the nursing and mathematical fields, Nightingale is also an important link in the study of English feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

. She wrote some 200 books, pamphlets and articles throughout her life. During 1850 and 1852, she was struggling with her self-definition and the expectations of an upper-class marriage from her family. As she sorted out her thoughts, she wrote ''Suggestions for Thought to Searchers after Religious Truth''. This was an 829-page, three-volume work, which Nightingale had printed privately in 1860, but which until recently was never published in its entirety. An effort to correct this was made with a 2008 publication by Wilfrid Laurier University

Wilfrid Laurier University (commonly referred to as WLU or simply Laurier) is a public university in Ontario, Canada, with campuses in Waterloo, Brantford and Milton. The newer Brantford and Milton campuses are not considered satellite campuses ...

, as volume 11 Privately printed by Nightingale in 1860. of a 16 volume project, the ''Collected Works of Florence Nightingale''. The best known of these essays, called "Cassandra", was previously published by Ray Strachey

Ray Strachey (born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe; 4 June 188716 July 1940) was a British feminist politician, artist and writer.

Early life

Her father was Irish barrister Benjamin "Frank" Conn Costelloe, and her mother was art historian Mary ...

in 1928. Strachey included it in ''The Cause'', a history of the women's movement. Apparently, the writing served its original purpose of sorting out thoughts; Nightingale left soon after to train at the Institute for deaconesses at Kaiserswerth

Kaiserswerth is one of the oldest quarters of the City of Düsseldorf, part of Borough 5. It is in the north of the city and next to the river Rhine. It houses the where Florence Nightingale worked.