First Czechoslovak Republic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The First Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, První československá republika, sk, Prvá česko-slovenská republika), often colloquially referred to as the First Republic ( cs, První republika, Slovak: ''Prvá republika''), was the first Czechoslovak state that existed from 1918 to 1938, a union of ethnic Czechs and

The independence of

The independence of

The operation of the new Czechoslovak government was distinguished by stability. Largely responsible for this were the well-organized

The operation of the new Czechoslovak government was distinguished by stability. Largely responsible for this were the well-organized

The Czech lands were far more industrialized than Slovakia. In Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, 39% of the population was employed in industry and 31% in agriculture and forestry. Most light and heavy industry was located in the

The Czech lands were far more industrialized than Slovakia. In Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, 39% of the population was employed in industry and 31% in agriculture and forestry. Most light and heavy industry was located in the

Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

. The country was commonly called Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

( Czech and sk, Československo), a compound of ''Czech'' and ''Slovak''; which gradually became the most widely used name for its successor states. It was composed of former territories of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, inheriting different systems of administration from the formerly Austrian ( Bohemia, Moravia, a small part of Silesia) and Hungarian territories (mostly Upper Hungary and Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

).

After 1933, Czechoslovakia remained the only ''de facto'' functioning democracy in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

, organized as a parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). There are a number ...

. Under pressure from its Sudeten German minority, supported by neighbouring Nazi Germany, Czechoslovakia was forced to cede its Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

region to Germany on 1 October 1938 as part of the Munich Agreement. It also ceded southern parts of Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

and the Zaolzie region in Silesia to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

. This, in effect, ended the First Czechoslovak Republic. It was replaced by the Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, Druhá československá republika, sk, Druhá česko-slovenská republika) existed for 169 days, between 30 September 1938 and 15 March 1939. It was composed of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and ...

, which lasted less than half a year before Germany occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

History

The independence of

The independence of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

was proclaimed on 28 October 1918 by the Czechoslovak National Council in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. Several ethnic groups and territories with different historical, political, and economic traditions were obliged to be blended into a new state structure. The origin of the First Republic lies in Point 10 of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace ter ...

: "The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development."

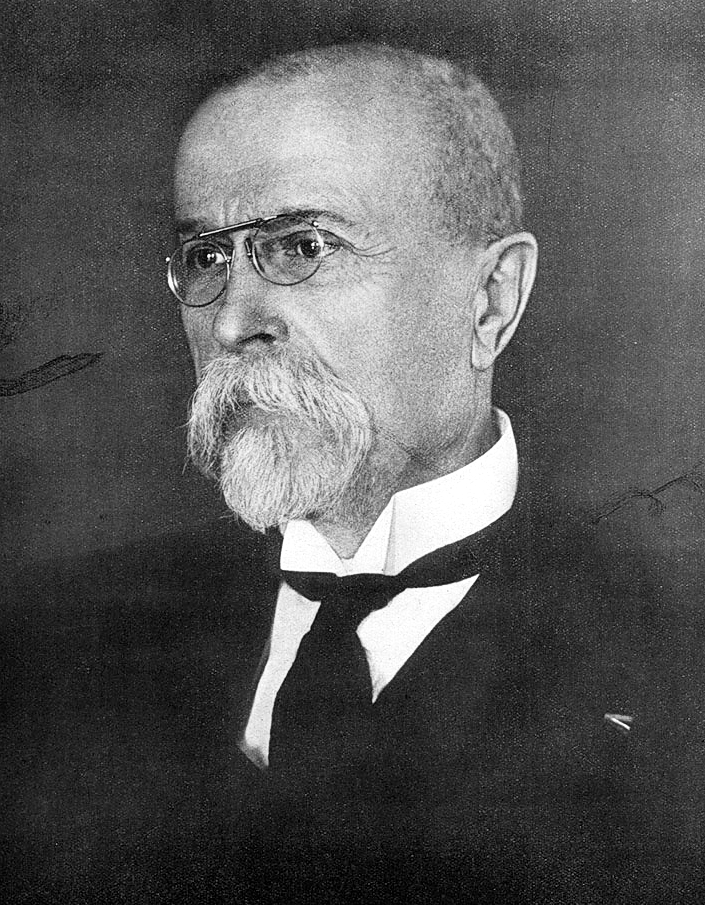

The full boundaries of the country and the organization of its government was finally established in the Czechoslovak Constitution of 1920. Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk had been recognized by World War I Allies

The Allies of World War I, Entente (alliance), Entente Powers, or Allied Powers were a coalition of countries led by French Third Republic, France, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, Russian Empire, Russia, King ...

as the leader of the Provisional Czechoslovak Government, and in 1920 he was elected the country's first president. He was re-elected in 1925 and 1929, serving as President until 14 December 1935 when he resigned due to poor health. He was succeeded by Edvard Beneš.

Following the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the Nazi Germany, German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "Ger ...

'' of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

by Germany in March 1938, the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's next target for annexation was Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. His pretext was the privations suffered by ethnic German populations living in Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

. Their incorporation into Nazi Germany would leave the rest of Czechoslovakia powerless to resist subsequent occupation.

Politics

To a large extent, Czechoslovak democracy was held together by the country's first president, Tomáš Masaryk. As the principal founding father of the republic, Masaryk was regarded similar to the wayGeorge Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the ...

is regarded in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. Such universal respect enabled Masaryk to overcome seemingly irresolvable political problems. Masaryk is still regarded as the symbol of Czechoslovak democracy.

The Constitution of 1920 approved the provisional constitution of 1918 in its basic features. The Czechoslovak state was conceived as a parliamentary democracy, guided primarily by the National Assembly, consisting of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and the Chamber of Deputies, whose members were to be elected on the basis of universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

. The National Assembly was responsible for legislative initiative and was given supervisory control over the executive and judiciary as well. Every seven years it elected the president and confirmed the cabinet appointed by him. Executive power was to be shared by the president and the cabinet; the latter, responsible to the National Assembly, was to prevail. The reality differed somewhat from this ideal, however, during the strong presidencies of Masaryk and his successor, Beneš. The constitution of 1920 provided for the central government to have a high degree of control over local government. From 1928 and 1940, Czechoslovakia was divided into the four "lands" ( cs, "země", sk, "krajiny"); Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia. Although in 1927 assemblies were provided for Bohemia, Slovakia, and Ruthenia, their jurisdiction was limited to adjusting laws and regulations of the central government to local needs. The central government appointed one third of the members of these assemblies. The constitution identified the "Czechoslovak nation" as the creator and principal constituent of the Czechoslovak state and established Czech and Slovak as official languages. The concept of the Czechoslovak nation was necessary in order to justify the establishment of Czechoslovakia towards the world, because otherwise the statistical majority of the Czechs as compared to Germans would have been rather weak, and there were more Germans in the state than Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

. National minorities were assured special protection; in districts where they constituted 20% of the population, members of minority groups were granted full freedom to use their language in everyday life, in schools, and in matters dealing with authorities.

political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

that emerged as the real centers of power. Excluding the period from March 1926 to November 1929, when the coalition did not hold, a coalition of five Czechoslovak parties constituted the backbone of the government: Republican Party of Agricultural and Smallholder People, Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, Czechoslovak National Social Party, Czechoslovak People's Party, and Czechoslovak National Democratic Party. The leaders of these parties became known as the "Pětka The Pětka, or Committee of Five, was an unofficial informal extraparliamentary semi-constitutional political forum that was designed to cope with political difficulties of the First Republic of Czechoslovakia. Founded in September 1920, it was a co ...

" (''pron. pyetka'') (The Five). The Pětka was headed by Antonín Švehla

Antonín Švehla (15 April 1873, in Prague – 12 December 1933 in Prague) was a Czechoslovak politician. He served three terms as the prime minister of Czechoslovakia. He is regarded as one of the most important political figures of the Firs ...

, who held the office of prime minister for most of the 1920s and designed a pattern of coalition politics that survived until 1938. The coalition's policy was expressed in the slogan "We have agreed that we will agree." German parties also participated in the government in the beginning of 1926. Hungarian parties, influenced by irredentist propaganda from Hungary, never joined the Czechoslovak government but were not openly hostile:

* The Republican Party of Agricultural and Smallholder People was formed in 1922 from a merger of the Czech Agrarian Party and the Slovak Agrarian Party. Led by Svehla, the new party became the principal voice for the agrarian population, representing mainly peasants with small and medium-sized farms. Svehla combined support for progressive social legislation with a democratic outlook. His party was the core of all government coalitions between 1922 and 1938.

* The Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party was considerably weakened when the communists seceded in 1921 to form the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, but by 1929 it had begun to regain its strength. A party of moderation, the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party declared in favor of parliamentary democracy in 1930. Antonín Hampl was chairman of the party, and Ivan Dérer was the leader of its Slovak branch.

* The Czechoslovak National Social Party (called the Czech Socialist Party until 1926) was created before World War I when the socialists split from the Social Democratic Party. It rejected class struggle and promoted nationalism. Led by Václav Klofáč, its membership derived primarily from the lower middle class, civil servants, and the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

(including Beneš).

* The Czechoslovak People's Party

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

** First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

** Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

** Fourth Czechoslovak R ...

a fusion of several Catholic parties, groups, and labor unionsdeveloped separately in Bohemia in 1918 and in the more strongly Catholic Moravia in 1919. In 1922 a common executive committee was formed, headed by Jan Šrámek

Jan Šrámek (11 August 1870 – 22 April 1956) was the prime minister of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile from 21 July 1940 to 5 April 1945. He was the first chairman of the Czechoslovak People's Party and was a Monsignor

Monsignor (; it, ...

. The Czechoslovak People's Party espoused Christian moral principles and the social encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII.

* The Czechoslovak National Democratic Party developed from a post–World War I merger of the Young Czech Party with other right wing and center parties. Ideologically, it was characterized by national radicalism and economic liberalism. Led by Kramář and Alois Rašín

Alois Rašín (18 October 1867 in Nechanice, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary – 18 February 1923 in Prague, Bohemia, Czechoslovakia) was a Czech and Czechoslovakian politician, economist, one of the founders of Czechoslovakia and first Ministry for Fin ...

, the Czechoslovak National Democratic Party became the party of big business, banking, and industry. The party declined in influence after 1920, however.

Foreign policy

Edvard Beneš, Czechoslovakforeign minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between coun ...

from 1918 to 1935, created the system of alliances that determined the republic's international stance until 1938. A democratic statesman of Western orientation, Beneš relied heavily on the League of Nations as guarantor of the post war status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. ...

and the security of newly formed states. He negotiated the Little Entente (an alliance with Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

) in 1921 to counter Hungarian revanchism and Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

restoration. He concluded a separate alliance with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

. Beneš's Western policy received a serious blow as early as 1925. The Locarno Pact, which paved the way for Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

's admission to the League of Nations, guaranteed Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

's western border. French troops were thus left immobilized on the Rhine, making French assistance to Czechoslovakia difficult. In addition, the treaty stipulated that Germany's eastern frontier would remain subject to negotiation. When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

came to power in 1933, fear of German aggression became widespread in eastern Central Europe. Beneš ignored the possibility of a stronger Central European alliance system, remaining faithful to his Western policy. He did, however, seek the participation of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

in an alliance to include France. (Beneš's earlier attitude towards the Soviet regime had been one of caution.) In 1935, the Soviet Union signed treaties with France and Czechoslovakia. In essence, the treaties provided that the Soviet Union would come to Czechoslovakia's aid only if French assistance came first.

In 1935, when Beneš succeeded Masaryk as president, the prime minister Milan Hodža took over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

. Hodža's efforts to strengthen alliances in Central Europe came too late. In February 1936, the foreign ministry came under the direction of Kamil Krofta, an adherent of Beneš's line.

The Czechoslovak Republic sold armament to Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

during the Chaco War

The Chaco War ( es, link=no, Guerra del Chaco, gn, Cháko ÑorairõParaguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

and advance Czechoslovak interest in Bolivia.

Economy

The new nation had a population of over 13.5 million. It had inherited 70 to 80% of all the industry of theAustro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

, including the porcelain and glass industries and the sugar refineries; more than 40% of all its distilleries and breweries; the Škoda Works of Pilsen (Plzeň

Plzeň (; German and English: Pilsen, in German ) is a city in the Czech Republic. About west of Prague in western Bohemia, it is the Statutory city (Czech Republic), fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 169,000 inhabita ...

), which produced armaments, locomotives, automobiles, and machinery

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecule ...

; and the chemical industry of northern Bohemia. Seventeen percent of all Hungarian industry that had developed in Slovakia during the late 19th century also fell to the republic. Czechoslovakia was one of the world's 10 most industrialized states.

The Czech lands were far more industrialized than Slovakia. In Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, 39% of the population was employed in industry and 31% in agriculture and forestry. Most light and heavy industry was located in the

The Czech lands were far more industrialized than Slovakia. In Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, 39% of the population was employed in industry and 31% in agriculture and forestry. Most light and heavy industry was located in the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

and was owned by Germans and controlled by German-owned banks. Czechs controlled only 20 to 30% of all industry. In Slovakia, 17.1% of the population was employed in industry, and 60.4% worked in agriculture and forestry. Only 5% of all industry in Slovakia was in Slovak hands. Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

was essentially without industry.

In the agricultural sector, a program of reform introduced soon after the establishment of the republic was intended to rectify the unequal distribution of land. One-third of all agricultural land and forests belonged to a few aristocratic landowners—mostly Germans (or Germanized Czechs – e.g. Kinsky, Czernin or Kaunitz

Wenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg (german: Wenzel Anton Reichsfürst von Kaunitz-Rietberg, cz, Václav Antonín z Kounic a Rietbergu; 2 February 1711 – 27 June 1794) was an Austrian and Czech diplomat and statesman in the Habsburg monarc ...

) and Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Ural ...

—and the Roman Catholic Church. Half of all holdings were under 20,000 m2. The Land Control Act of April 1919 called for the expropriation of all estates exceeding 1.5 square kilometres of arable land or 2.5 square kilometres of land in general (5 square kilometres to be the absolute maximum). Redistribution was to proceed on a gradual basis; owners would continue in possession in the interim, and compensation was offered.

Ethnic groups

1921 ethnonational census National disputes arose due to the fact that the more numerous Czechs dominated the central government and other national institutions, all of which had their seats in the Bohemian capital Prague. The Slovak middle class had been extremely small in 1919 because Hungarians, Germans and Jews had previously filled most administrative, professional and commercial positions in, and as a result, the Czechs had to be posted to the more backward Slovakia to take up the administrative and professional posts. The position of the Jewish community, especially in Slovakia, was ambiguous and, increasingly, a significant part looked towardsZionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

.

Furthermore, most of Czechoslovakia's industry was as well located in Bohemia and Moravia, while most of Slovakia's economy came from agriculture. In Carpatho-Ukraine, the situation was even worse, with basically no industry at all.

Due to Czechoslovakia's centralized political structure, nationalism arose in the non-Czech nationalities, and several parties and movements were formed with the aim of broader political autonomy, like the Sudeten German Party led by Konrad Henlein and the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party ( sk, Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana), also known as the Slovak People's Party (, SĽS) or the Hlinka Party, was a far-right clerico-fascist political party with a strong Catholic fundamentalist and authoritar ...

led by Andrej Hlinka.

The German minority living in Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

demanded autonomy from the Czechoslovak government, claiming they were suppressed and repressed. In the 1935 Parliamentary elections, the newly founded Sudeten German Party, led by Konrad Henlein and mostly financed by Nazi German money, received over two-thirds of the Sudeten German

German Bohemians (german: Deutschböhmen und Deutschmährer, i.e. German Bohemians and German Moravians), later known as Sudeten Germans, were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part ...

vote. As a consequence, diplomatic relations between the Germans and the Czechs deteriorated further.

Administrative divisions

* 1918–1923: Different systems in former Austrian territory ( Bohemia, Moravia, a small part of Silesia) compared to former Hungarian territory (mostly Upper Hungary andCarpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

): three lands (''země'') (also called district units (''kraje''): Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, plus 21 counties (''župy'') in today's Slovakia and three counties in today's Ruthenia; both lands and counties were divided into districts (''okres Okres (Czech and Slovak term meaning "district" in English; from German Kreis - circle (or perimeter)) refers to administrative entities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. It is similar to Landkreis in Germany or "''okrug''" in other Slavic-speaki ...

y'').

* 1923–1927: As above, except that the Slovak and Ruthenian counties were replaced by six (grand) counties (''(veľ)župy'') in Slovakia and one (grand) county in Ruthenia, and the numbers and boundaries of the ''okresy'' were changed in those two territories.

* 1928–1938: Four lands (Czech: ''země'', Slovak: ''krajiny''): Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia and sub Carpathian Ruthenia, divided into districts (''okresy'').

See also

* Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938) * Hungarians in Slovakia * Polish minority in the Czech Republic *Ruthenians and Ukrainians in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sourc ...

* Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918–38)

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party ( sk, Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana), also known as the Slovak People's Party (, SĽS) or the Hlinka Party, was a far-right clerico-fascist political party with a strong Catholic fundamentalist and authorit ...

* Jews in Slovakia

The history of the Jews in Slovakia goes back to the 11th century, when the first Jews settled in the area.

Early history

In the 14th century, about 800 Jews lived in Bratislava, the majority of them engaged in commerce and money lending. ...

References

Bibliography

* Kárník, Zdeněk: Malé dějiny československé (1867–1939), Dokořán (2008), Praha, * Olivová, Věra: Dějiny první republiky, Karolinum Press (2000), Praha, * Peroutka, Ferdinand: Budování státu I.-IV., Academia (2003), Praha, * Gen.František Moravec

František Moravec CBE (23 July 1895 – 26 July 1966) was the chief Czechoslovak military intelligence officer before and during World War II. He moved to the United States after the war.

Biography

In 1915, Moravec was drafted into Austro-Hun ...

: Špión jemuž nevěřili

* Axworthy, Mark W.A. ''Axis Slovakia—Hitler's Slavic Wedge, 1938–1945'', Bayside, N.Y. : Axis Europa Books, 2002,

{{Czechoslovakia timeline

1918

Czechoslovak Republic 01

Czechoslovak Republic 01

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

1910s in Czechoslovakia

.

.

States and territories established in 1918

States and territories disestablished in 1938

*

*

1918 establishments in Europe

1938 disestablishments in Europe

.1918

Power sharing

1918

es:Checoslovaquia#La primera república (1918-1938)