finback whale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus''), also known as finback whale or common rorqual and formerly known as herring whale or razorback whale, is a

The fin whale was first described by

The fin whale was first described by

The fin whale is brownish to dark or light gray dorsally and white ventrally. The left side of the head is dark gray, while the right side exhibits a complex pattern of contrasting light and dark markings. On the right lower jaw is a white or light gray "right mandible patch", which sometimes extends out as a light "blaze" laterally and dorsally unto the upper jaw and back to just behind the blowholes. Two narrow dark stripes originate from the eye and ear, the former widening into a large dark area on the shoulderŌĆöthese are separated by a light area called the "interstripe wash". These markings are more prominent on individuals in the North Atlantic than in the North Pacific, where they can appear indistinct. The left side exhibits similar but much fainter markings. Dark, oval-shaped areas of pigment called "flipper shadows" extend below and posterior to the pectoral fins. This type of

The fin whale is brownish to dark or light gray dorsally and white ventrally. The left side of the head is dark gray, while the right side exhibits a complex pattern of contrasting light and dark markings. On the right lower jaw is a white or light gray "right mandible patch", which sometimes extends out as a light "blaze" laterally and dorsally unto the upper jaw and back to just behind the blowholes. Two narrow dark stripes originate from the eye and ear, the former widening into a large dark area on the shoulderŌĆöthese are separated by a light area called the "interstripe wash". These markings are more prominent on individuals in the North Atlantic than in the North Pacific, where they can appear indistinct. The left side exhibits similar but much fainter markings. Dark, oval-shaped areas of pigment called "flipper shadows" extend below and posterior to the pectoral fins. This type of

When feeding, they blow five to seven times in quick succession, but while traveling or resting will blow once every minute or two. On their terminal (last) dive they arch their back high out of the water, but rarely raise their flukes out of the water. They then dive to depths of up to when feeding or a few hundred feet when resting or traveling. The average feeding dive off California and Baja lasts 6 minutes, with a maximum of 17 minutes; when traveling or resting they usually dive for only a few minutes at a time.

When feeding, they blow five to seven times in quick succession, but while traveling or resting will blow once every minute or two. On their terminal (last) dive they arch their back high out of the water, but rarely raise their flukes out of the water. They then dive to depths of up to when feeding or a few hundred feet when resting or traveling. The average feeding dive off California and Baja lasts 6 minutes, with a maximum of 17 minutes; when traveling or resting they usually dive for only a few minutes at a time.

North Atlantic fin whales are defined by the

North Atlantic fin whales are defined by the

Satellite tracking revealed that those found in Pelagos Sanctuary migrate southward to off

Satellite tracking revealed that those found in Pelagos Sanctuary migrate southward to off

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) feeding ground in the coastal waters of Ischia (Archipelago Campano)

(pdf). The European Cetacean Society. Retrieved on 28 March 2017), winter feeding ground of

The total historical

The total historical

The fin whale is a

The fin whale is a

In the 19th century, the fin whale was occasionally hunted by open-boat whalers, but it was relatively safe, because it could easily outrun ships of the time and often sank when killed, making the pursuit a waste of time for whalers. However, the later introduction of steam-powered boats and

In the 19th century, the fin whale was occasionally hunted by open-boat whalers, but it was relatively safe, because it could easily outrun ships of the time and often sank when killed, making the pursuit a waste of time for whalers. However, the later introduction of steam-powered boats and

File:Whale skeleton Monaco.jpeg, An fin whale skeleton at the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco

File:Fin_whale_skeleton.webm, Fin whale skeleton, Museum of Zoology Cambridge

File:Balaenoptera physalus skeleton in the Van Thuy Tu Temple.jpg, Fin whale skeleton at the Van Thuy Tu Temple

Fin whales are regularly encountered on whale-watching excursions worldwide. In the

Fin whales are regularly encountered on whale-watching excursions worldwide. In the

The fin whale is listed on both Appendix I and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).

In addition, the fin whale is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the

The fin whale is listed on both Appendix I and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).

In addition, the fin whale is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the

''Fin whale''. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

. C. Michael Hogan Ed. Content partner: Encyclopedia of Life * ''National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World'', Reeves, Stewart, Clapham and Powell, * ''Whales & Dolphins Guide to the Biology and Behaviour of Cetaceans'', Maurizio Wurtz and Nadia Repetto. * ''Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals'', editors Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen,

* ARKive ŌĆ

images and videos of the fin whale ''(Balaenoptera physalus)''

Finback whale sounds

Photograph of a fin whale underwater

Photographs of a fin whale breaching

World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) ŌĆō species profile for the fin whale

{{Taxonbar, from=Q179020

cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

n belonging to the parvorder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

of baleen whale

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

s. It is the second-longest species of cetacean on Earth after the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

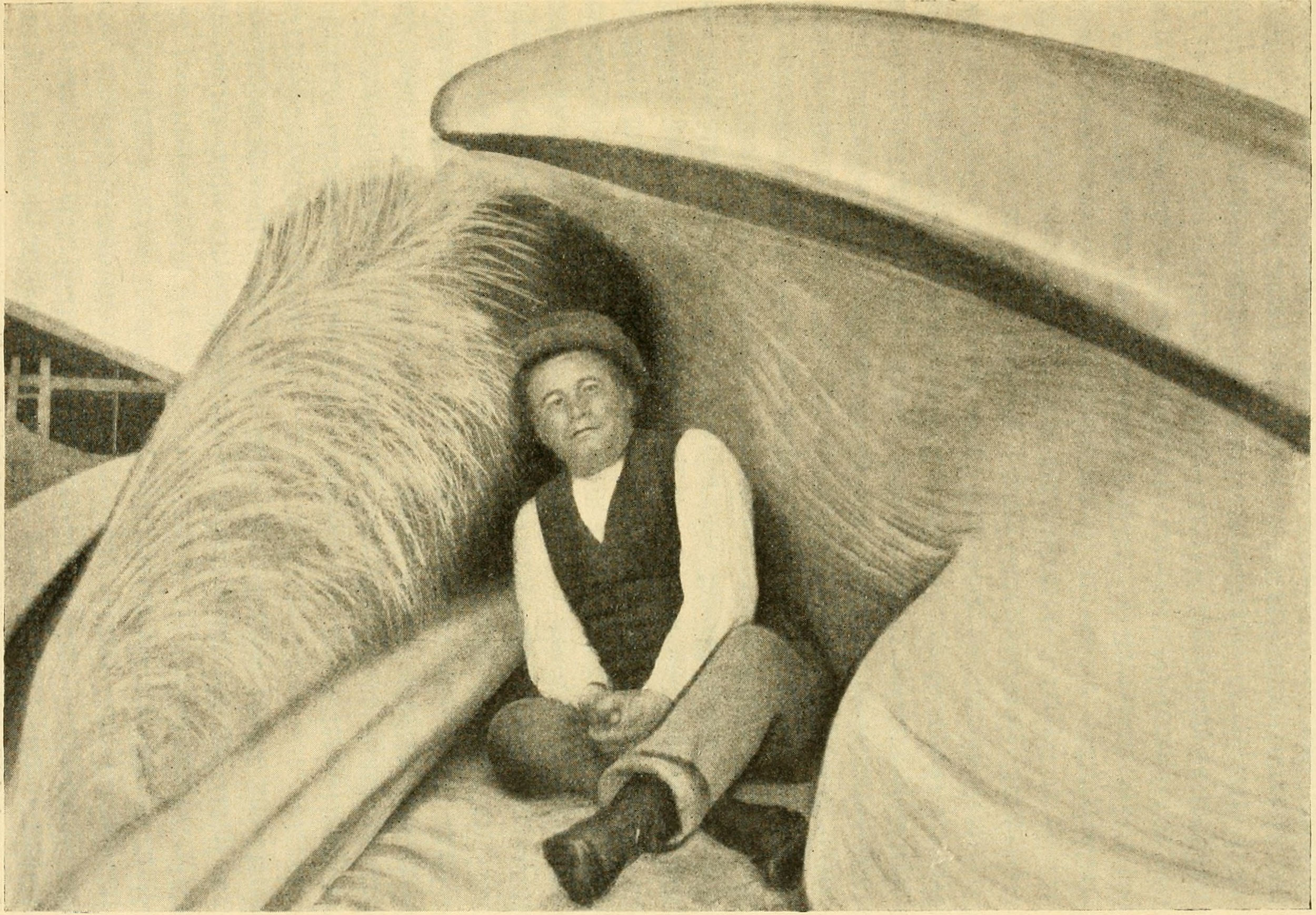

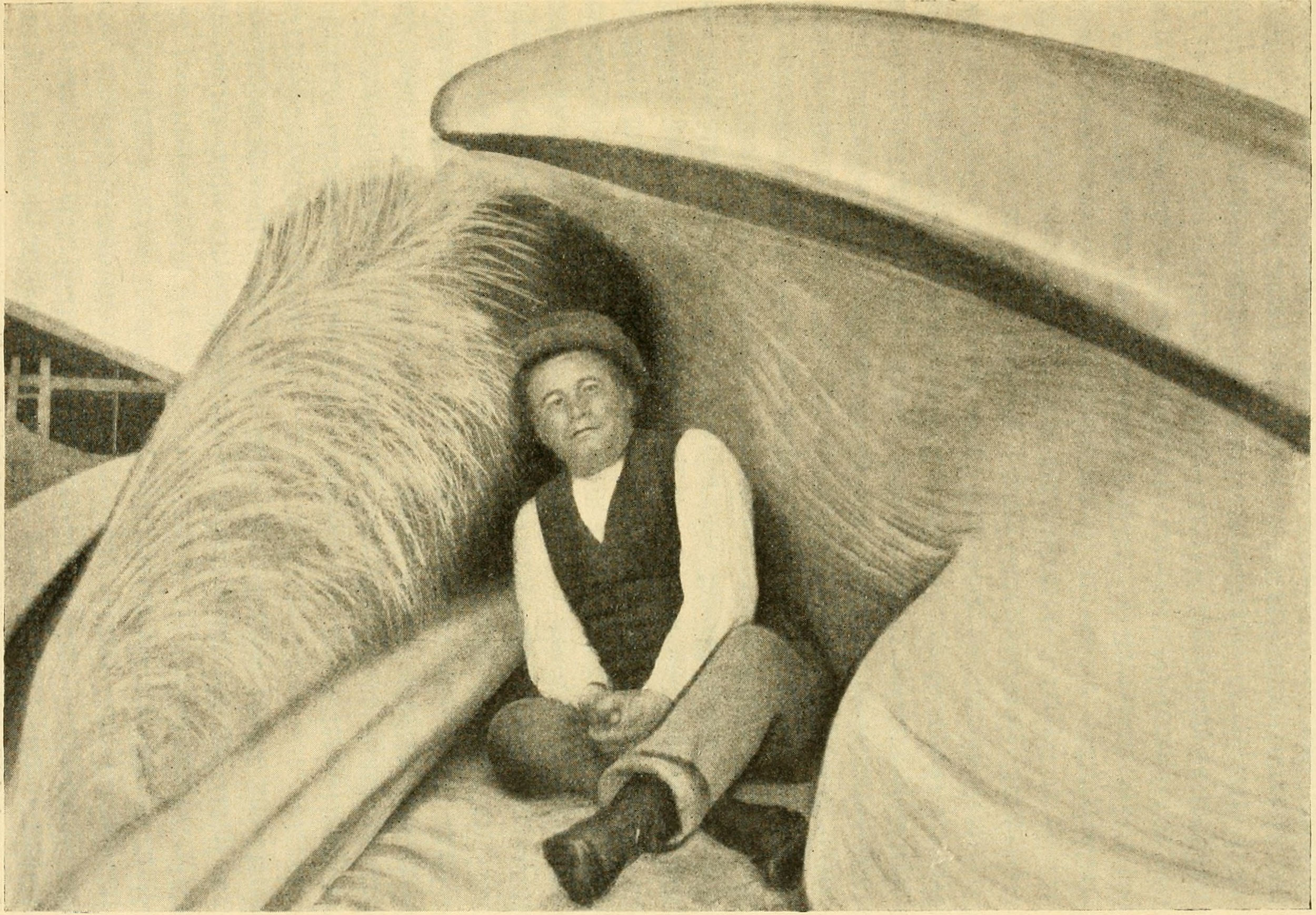

. The largest reportedly grow to long with a maximum confirmed length of , a maximum recorded weight of nearly , and a maximum estimated weight of around . American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884 ŌĆō March 11, 1960) was an American explorer, adventurer and naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politically disturbed C ...

called the fin whale "the greyhound of the sea ... for its beautiful, slender body is built like a racing yacht and the animal can surpass the speed of the fastest ocean steamship."

The fin whale's body is long and slender, coloured brownish-grey with a paler underside. At least two recognized subspecies exist, in the North Atlantic and the Southern Hemisphere. It is found in all the major oceans, from polar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

Polar may refer to:

* Geographical pole, either of two fixed points on the surface of a rotating body or planet, at 90 degrees from the equator, based on the axis around which a body rotates

* Polar climate, the c ...

to tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

waters. It is absent only from waters close to the pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Lepp├żranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fasten ...

at the poles and relatively small areas of water away from the open ocean. The highest population density occurs in temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5┬░ to 66.5┬░ N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

and cool waters. Its food consists of small schooling

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compuls ...

fish, squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

, and crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s including copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthos, benthic (living on the ocean floor) ...

s and krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in n ...

.

Like all other large whales, the fin whale was heavily hunted during the 20th century. As a result, it is an endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

. Over 725,000 fin whales were reportedly taken from the Southern Hemisphere between 1905 and 1976; as of 1997 only 38,000 survived. Recovery of the overall population size of southern subspecies is predicted to be at less than 50% of its pre-whaling state by 2100 due to heavier impacts of whaling and slower recovery rates.

The International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation of ...

(IWC) issued a moratorium on commercial hunting of this whale, although Iceland and Japan have resumed hunting. The species is also hunted by Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Gr├Ėnland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

ers under the IWC's Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling provisions. Global population estimates range from less than 100,000 to roughly 119,000.

Taxonomy

Friderich Martens

Friderich Martens (1635 - 1699)

, Tj├żrn├Č Marine Biological Laboratory, G├Čteborg University ...

in 1675 and by Paul Dudley in 1725. The former description was used as the primary basis of the species ''Balaena physalus'' by , Tj├żrn├Č Marine Biological Laboratory, G├Čteborg University ...

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 ŌĆō 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linn├® Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

in 1758. In 1804, Bernard Germain de Lac├®p├©de

Bernard-Germain-├ētienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, comte de Lac├®p├©de or La C├®p├©de (; 26 December 17566 October 1825) was a French naturalist and an active freemason. He is known for his contribution to the Comte de Buffon's great work, the ...

reclassified the species as ''Balaenoptera rorqual'', based on a specimen that had stranded on Île Sainte-Marguerite

The ├Äle Sainte-Marguerite () is the largest of the L├®rins Islands, about half a mile off shore from the French Riviera town of Cannes. The island is approximately in length (east to west) and across.

The island is most famous for its fort ...

(Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a communes of France, commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions I ...

, France) in 1798. In 1830, Louis Companyo

Louis Companyo (born in C├®ret in 1781 and died in Perpignan in 1871) was a French physician and naturalist.

Louis Companyo was a founder and director of the Mus├®e d'Histoire Naturelle de Perpignanbr>and wrote ''Histoire Naturelle du d├®partem ...

described a specimen that had stranded near Saint-Cyprien, southern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, in 1828 as ''Balaena musculus''. Most later authors followed him in using the specific name ''musculus'', until Frederick W. True

Frederick William True (July 8, 1858 ŌĆō June 25, 1914) was an American biologist, the first head curator of biology (1897ŌĆō1911) at the United States National Museum, now part of the Smithsonian Institution.

Biography

He was born in Middletown, ...

(1898) showed that it referred to the blue whale. In 1846, British taxonomist John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray, FRS (12 February 1800 ŌĆō 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766ŌĆō1828). The same is used for ...

described a specimen from the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

as ''Balaenoptera australis''. In 1865, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

naturalist Hermann Burmeister described a roughly specimen found near Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Aut├│noma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the R├Ło de la Plata, on South ...

about 30 years earlier as ''Balaenoptera patachonicus''. In 1903, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n scientist Emil Racovi╚ø─ā placed all these designations into ''Balaenoptera physalus''. The word ''physalus'' comes from the Greek word ''physa'', meaning "blows", referring to the prominent blow of the species.

Fin whales are rorqual

Rorquals () are the largest group of baleen whales, which comprise the family Balaenopteridae, containing ten extant species in three genera. They include the largest animal that has ever lived, the blue whale, which can reach , and the fin wha ...

s, members of the family Balaenopteridae

Rorquals () are the largest group of baleen whales, which comprise the family Balaenopteridae, containing ten extant species in three genera. They include the largest animal that has ever lived, the blue whale, which can reach , and the fin wha ...

, which also includes the humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hump ...

, the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known to have ever existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

, Bryde's whale

Bryde's whale ( Brooder's), or the Bryde's whale complex, putatively comprises three species of rorqual and maybe four. The "complex" means the number and classification remains unclear because of a lack of definitive information and research ...

, the sei whale

The sei whale ( , ; ''Balaenoptera borealis'') is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale. It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters. It avoids polar and tropical ...

, and the minke whale

The minke whale (), or lesser rorqual, is a species complex of baleen whale. The two species of minke whale are the common (or northern) minke whale and the Antarctic (or southern) minke whale. The minke whale was first described by the Danish n ...

s. The family diverged from the other baleen whale

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

s in the suborder Mysticeti

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

as long ago as the middle Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

.

Recent DNA evidence indicates the fin whale may be more closely related to the humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') and in at least one study the gray whale

The gray whale (''Eschrichtius robustus''), also known as the grey whale,Britannica Micro.: v. IV, p. 693. gray back whale, Pacific gray whale, Korean gray whale, or California gray whale, is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and bree ...

(''Eschrichtius robustus''), two whales in different genera, than it is to members of its own genus, such as the minke whales.

As of 2022, four subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

are named, each with distinct physical features and vocalizations. The northern fin whale

The northern fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus physalus'') is a subspecies of fin whale that lives in the North Atlantic Ocean and North Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It ...

, ''B. p. physalus'' (Linnaeus 1758) inhabits the North Atlantic and the southern fin whale

The southern fin whale (''Balaenoptera physalus quoyi'') is a subspecies of fin whale that lives in the Southern Ocean. At least one other subspecies of fin whale, the northern fin whale (''B. p. physalus''), exists in the northern hemisphere.

...

, ''B. p. quoyi'' (Fischer 1829) occupies the Southern Hemisphere. Most experts consider the fin whales of the North Pacific to be a third subspeciesŌĆöthis was supported by a 2013 study, which found that the Northern Hemisphere ''B. p. physalus'' was not composed of a single subspecies. A 2019 genetic study concluded that the North Pacific fin whales should be considered a subspecies, suggesting the name ''B. p. velifera'' (Scammon 1869). The three groups mix at most rarely.

Clarke (2004) proposed a "pygmy" subspecies (''B. p. patachonica'', Burmeister, 1865) that is purportedly darker in colour and has black baleen. He based this on a single physically mature female caught in the Antarctic in 1947ŌĆō48, the smaller average size (a few feet) of sexually and physically mature fin whales caught by the Japanese around 50┬░S, and smaller, darker sexually immature fin whales caught in the Antarctic which he believed were a "migratory phase" of his proposed subspecies. The subspecies has not been genetically established, and is not recognized by the Society for Marine Mammalogy

The Society for Marine Mammalogy was founded in 1981 and is the largest international association of marine mammal scientists in the world.

Mission

The mission of the Society for Marine Mammalogy (SMM) is to promote the global advancement of mari ...

.

Hybrids

The genetic distance between blue and fin whales has been compared to that between agorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

and human (3.5 million years on the evolutionary tree.) Nevertheless, hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two dif ...

individuals between blue and fin whales with characteristics of both are known to occur with relative frequency in both the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

The DNA profile of a sampling of whale meat

Whale meat, broadly speaking, may include all cetaceans (whales, dolphins, porpoises) and all parts of the animal: muscle (meat), organs (offal), skin (muktuk), and fat (blubber). There is relatively little demand for whale meat, compared to ...

in the Japanese market found evidence of blue/fin hybrids.

Anatomy

Size

In theNorthern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

, the average size of adult males and females is about , respectively, averaging 38.5 and 50.5 tonnes (42.5 and 55.5 tons), while in the Southern Hemisphere, it is ,Evans, Peter G. H. (1987). ''The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins''. Facts on File. weighing 52.5 and 63 tonnes (58 and 69.5 tons).

In the North Atlantic, the longest reported were a 24.4 m (80 ft) male caught off Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

in 1905 and a female caught off Scotland sometime between 1908 and 1914, while the longest reliably measured were three 20.7 m (68 ft) males caught off Iceland in 1973ŌĆō74 and a 22.5 m (74 ft) female also caught off Iceland in 1975. Mediterranean population are generally smaller, reaching just above 20 m (65.5 ft) at maximum, or possibly up to .

In the North Pacific, the longest reported were three 22.9 m (75 ft) males, two caught off California between 1919 and 1926 and the other caught off Alaska in 1925, and a 24.7 m (81 ft) female also caught off California, while the longest reliably measured were a 21 m (69 ft) male caught off British Columbia in 1959 and a 22.9 m (75 ft) female caught off central California between 1959 and 1970.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the longest reported were a 25 m (82 ft) male and a 27.3 m (89.6 ft) female, while the longest measured by Mackintosh and Wheeler (1929) were a 22.65 m (74.3 ft) male and a 24.53 m (80.5 ft) female. Major F. A. Spencer, while whaling inspector of the factory ship ''Southern Princess'' (1936ŌĆō38), confirmed the length of a female caught in the Antarctic, south of the Indian Ocean; scientist David Edward Gaskin also measured a 25.9 m female as whaling inspector of the British factory ship ''Southern Venturer'' in the Southern Ocean in the 1961ŌĆō62 season.Gaskin, D. E. (1968). "The New Zealand Cetacea". ''Fish. Res. Bull.'', N.Z. (n.s.) 1: 1ŌĆō92. Terence Wise, who worked as a winch operator aboard the British factory ship ''Balaena'', claimed that "the biggest fin eever saw" was a specimen caught near Bouvet Island in January 1958.Wise, Terence. 1970. ''To Catch a Whale''. Geoffrey Bles. The largest fin whale ever weighed (piecemeal) was a pregnant female caught by Japanese whalers in the Antarctic in 1948 which weighed , not including 6% for loss of fluids during the flensing process. An individual at the maximum confirmed size of 25.9 m is estimated to weigh around 95 tonnes (104.5 tons), varying from about 76 tonnes (84 tons) to 114 tonnes (125.5 tons) depending on fat condition which varies by about 50% during the year.

A newborn fin whale measures about in length and weighs about .

Colouration and markings

The fin whale is brownish to dark or light gray dorsally and white ventrally. The left side of the head is dark gray, while the right side exhibits a complex pattern of contrasting light and dark markings. On the right lower jaw is a white or light gray "right mandible patch", which sometimes extends out as a light "blaze" laterally and dorsally unto the upper jaw and back to just behind the blowholes. Two narrow dark stripes originate from the eye and ear, the former widening into a large dark area on the shoulderŌĆöthese are separated by a light area called the "interstripe wash". These markings are more prominent on individuals in the North Atlantic than in the North Pacific, where they can appear indistinct. The left side exhibits similar but much fainter markings. Dark, oval-shaped areas of pigment called "flipper shadows" extend below and posterior to the pectoral fins. This type of

The fin whale is brownish to dark or light gray dorsally and white ventrally. The left side of the head is dark gray, while the right side exhibits a complex pattern of contrasting light and dark markings. On the right lower jaw is a white or light gray "right mandible patch", which sometimes extends out as a light "blaze" laterally and dorsally unto the upper jaw and back to just behind the blowholes. Two narrow dark stripes originate from the eye and ear, the former widening into a large dark area on the shoulderŌĆöthese are separated by a light area called the "interstripe wash". These markings are more prominent on individuals in the North Atlantic than in the North Pacific, where they can appear indistinct. The left side exhibits similar but much fainter markings. Dark, oval-shaped areas of pigment called "flipper shadows" extend below and posterior to the pectoral fins. This type of asymmetry

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry (the property of an object being invariant to a transformation, such as reflection). Symmetry is an important property of both physical and abstract systems and it may be displayed in pre ...

is seen in Omura's whale

Omura's whale or the dwarf fin whale (''Balaenoptera omurai'') is a species of rorqual about which very little is known. Before its formal description, it was referred to as a small, dwarf or pygmy form of Bryde's whale by various sources. The c ...

and occasionally in minke whale

The minke whale (), or lesser rorqual, is a species complex of baleen whale. The two species of minke whale are the common (or northern) minke whale and the Antarctic (or southern) minke whale. The minke whale was first described by the Danish n ...

s. It was thought to have evolved because the whale swims on its right side when surface lunging and it sometimes circles to the right while at the surface above a prey patch. However, the whales just as often circle to the left. No accepted hypothesis explains the asymmetry.

It has paired blowholes and a broad, flat, V-shaped rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

. A light V-shaped marking, the chevron

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* ''Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock lay ...

, begins behind the blowholes and extends back and then forward again.

The whale has a series of 56ŌĆō100 pleat

A pleat (plait in older English) is a type of fold formed by doubling fabric back upon itself and securing it in place. It is commonly used in clothing and upholstery to gather a wide piece of fabric to a narrower circumference.

Pleats are cat ...

s or grooves along the bottom of the body that run from the tip of the chin

The chin is the forward pointed part of the anterior mandible (List_of_human_anatomical_regions#Regions, mental region) below the lower lip. A fully developed human skull has a chin of between 0.7 cm and 1.1 cm.

Evolution

The presence of a we ...

to the navel

The navel (clinically known as the umbilicus, commonly known as the belly button or tummy button) is a protruding, flat, or hollowed area on the abdomen at the attachment site of the umbilical cord. All placental mammals have a navel, although ...

that allow the throat area to expand greatly during feeding. It has a curved, prominent dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through conv ...

that ranges in height from (usually ) and averages about , lying about three quarters of the way along the back. Its flippers are small and tapered and its tail is wide, pointed at the tip, and notched in the centre.

When the whale surfaces, the dorsal fin is visible soon after the spout. The spout is vertical and narrow and can reach heights of or more.

Nervous system

The oral cavity of the fin whale has a very stretchy or extensible nerve system which aids them in feeding.Life history

Mating

In biology, mating is the pairing of either opposite-sex or hermaphroditic organisms for the purposes of sexual reproduction. ''Fertilization'' is the fusion of two gametes. ''Copulation'' is the union of the sex organs of two sexually reproduc ...

occurs in temperate, low-latitude seas during the winter, followed by an 11- to 12-month gestation period

In mammals, pregnancy is the period of reproduction during which a female carries one or more live offspring from implantation in the uterus through gestation. It begins when a fertilized zygote implants in the female's uterus, and ends once it ...

. A newborn weans from its mother at 6 or 7 months of age when it is in length, and the accompanies the mother to the summer feeding ground. Females reproduce every 2 or 3 years, with as many as six fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal deve ...

es being reported, but single births are far more common. Females reach sexual maturity between 6 and 12 years of age at lengths of in the Northern Hemisphere and in the Southern Hemisphere. Calves remain with their mothers for about one year.

Full physical maturity is attained between 25 and 30 years. Fin whales have a maximum life span of at least 94 years of age, although specimens have been found aged at an estimated 135ŌĆō140 years.

The fin whale is one of the fastest cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

ns and can sustain speeds between and and bursts up to have been recorded, earning the fin whale the nickname "the greyhound of the sea".

Fin whales are more gregarious than other rorquals, and often live in groups of 6ŌĆō10, although feeding groups may reach up to 100 animals.

Vocalizations

Like other whales, males make long, loud, low-frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

sounds. The vocalizations of blue and fin whales are the lowest-frequency sounds made by any animal. Most sounds are frequency-modulated (FM) down-swept infrasonic

Infrasound, sometimes referred to as low status sound, describes sound waves with a frequency below the lower limit of human audibility (generally 20 Hz). Hearing becomes gradually less sensitive as frequency decreases, so for humans to perce ...

pulses from 16 to 40 hertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is sŌłÆ1, meaning that on ...

frequency (the range of sounds that most humans can hear falls between 20 hertz and 20 kilohertz). Each sound lasts one to two second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day ŌĆō this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

s, and various sound combinations occur in patterned sequences lasting 7 to 15 minutes each. The whale then repeats the sequences in bouts lasting up to many days. The vocal sequences have source levels of up to 184ŌĆō186 decibel

The decibel (symbol: dB) is a relative unit of measurement equal to one tenth of a bel (B). It expresses the ratio of two values of a power or root-power quantity on a logarithmic scale. Two signals whose levels differ by one decibel have a po ...

s relative to 1 micropascal

The pascal (symbol: Pa) is the unit of pressure in the International System of Units (SI), and is also used to quantify internal pressure, stress, Young's modulus, and ultimate tensile strength. The unit, named after Blaise Pascal, is defined a ...

at a reference distance of one metre and can be detected hundreds of miles from their source.W. J. Richardson, C. R. Greene, C. I. Malme and D. H. Thomson, Marine Mammals and Noise (Academic Press, San Diego, 1995).

When fin whale sounds were first recorded by US biologists, they did not realize that these unusually loud, long, pure and regular sounds were being made by whales. They first investigated the possibilities that the sounds were due to equipment malfunction, geophysical phenomena, or even part of a Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

scheme for detecting enemy submarines. Eventually, biologists demonstrated that the sounds were the vocalizations of fin whales.

Direct association of these vocalizations with the reproductive season for the species and that only males make the sounds point to these vocalizations as possible reproductive displays. Over the past 100 years, the dramatic increase in ocean noise from shipping and naval activity may have slowed the recovery of the fin whale population, by impeding communications between males and receptive females.

Fin whale songs can penetrate over 2,500 m (8,200 ft) below the sea floor and seismologists can use those song waves to assist in underwater surveys.

Breathing

When feeding, they blow five to seven times in quick succession, but while traveling or resting will blow once every minute or two. On their terminal (last) dive they arch their back high out of the water, but rarely raise their flukes out of the water. They then dive to depths of up to when feeding or a few hundred feet when resting or traveling. The average feeding dive off California and Baja lasts 6 minutes, with a maximum of 17 minutes; when traveling or resting they usually dive for only a few minutes at a time.

When feeding, they blow five to seven times in quick succession, but while traveling or resting will blow once every minute or two. On their terminal (last) dive they arch their back high out of the water, but rarely raise their flukes out of the water. They then dive to depths of up to when feeding or a few hundred feet when resting or traveling. The average feeding dive off California and Baja lasts 6 minutes, with a maximum of 17 minutes; when traveling or resting they usually dive for only a few minutes at a time.

Ecology

Range and habitat

Like many large rorquals, the fin whale is a cosmopolitan species. It is found in all the world's major oceans and in waters ranging from thepolar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

Polar may refer to:

* Geographical pole, either of two fixed points on the surface of a rotating body or planet, at 90 degrees from the equator, based on the axis around which a body rotates

* Polar climate, the c ...

to the tropical. It is absent only from waters close to the ice pack

An ice pack or gel pack is a portable bag filled with water, refrigerant gel, or liquid, meant to provide cooling. They can be divided into the reusable type, which works as a thermal mass and requires freezing, or the instant type, which cools ...

at both the north and south extremities and relatively small areas of water away from the large oceans, such as the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, ž¦┘äž©žŁž▒ ž¦┘䞯žŁ┘ģž▒ - ž©žŁž▒ ž¦┘ä┘é┘äž▓┘ģ, translit=Modern: al-BaßĖźr al-╩ŠAßĖźmar, Medieval: BaßĖźr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: Ō▓½Ō▓ōŌ▓¤Ō▓Ö Ō▓ø╠ĆŽ®Ō▓üŽ® ''Phiom Enhah'' or Ō▓½Ō▓ōŌ▓¤Ō▓Ö Ō▓ø╠ĆŽŻŌ▓üŌ▓ŻŌ▓ō ''Phiom Ū╣┼Īari''; T ...

, although they can reach into the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53┬░N to 66┬░N latitude and from ...

, a marginal sea

This is a list of seas of the World Ocean, including marginal seas, areas of water, various gulfs, bights, bays, and straits.

Terminology

* Ocean ŌĆō the four to seven largest named bodies of water in the World Ocean, all of which have "Ocean ...

of such conditions. The highest population density occurs in temperate and cool waters. It is less densely populated in the warmest, equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

ial regions.

The North Atlantic fin whale has an extensive distribution, occurring from the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de M├®xico) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

and Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

, northward to Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay ( Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arct ...

and Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norw ...

. In general, fin whales are more common north of approximately 30┬░N latitude, but considerable confusion arises about their occurrence south of 30┬░N latitude because of the difficulty in distinguishing fin whales from Bryde's whale

Bryde's whale ( Brooder's), or the Bryde's whale complex, putatively comprises three species of rorqual and maybe four. The "complex" means the number and classification remains unclear because of a lack of definitive information and research ...

s. Extensive ship surveys have led researchers to conclude that the summer feeding range of fin whales in the western North Atlantic is mainly between 41┬░20'N and 51┬░00'N, from shore seaward to the contour.

Summer distribution of fin whales in the North Pacific is the immediate offshore waters from central Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

to Japan

Japan ( ja, µŚźµ£¼, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and as far north as the Chukchi Sea

Chukchi Sea ( rus, ą¦čāą║ąŠ╠üčéčüą║ąŠąĄ ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ, r=Chukotskoye more, p=t╔Ģ╩Ŗ╦łkotsk╔Öj╔Ö ╦łmor╩▓╔¬), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west b ...

bordering the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. They occur in high densities in the northern Gulf of Alaska and southeastern Bering Sea

The Bering Sea (, ; rus, ąæąĄ╠üčĆąĖąĮą│ąŠą▓ąŠ ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ, r=B├®ringovo m├│re) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Ameri ...

between May and October, with some movement through the Aleutian passes into and out of the Bering Sea. Several whales tagged between November and January off southern California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

were killed in the summer off central California, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, and in the Gulf of Alaska. Fin whales have been observed feeding 250 miles south of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

in mid-May, and several winter sightings have been made there. Some researchers have suggested that the whales migrate into Hawaiian waters primarily in the autumn and winter.

Although fin whales are certainly migratory, moving season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperate and pol ...

ally in and out of high-latitude feeding areas, the overall migration pattern is not well understood. Acoustic readings from passive-listening hydrophone

A hydrophone ( grc, ßĮĢ╬┤ŽēŽü + ŽåŽē╬Į╬«, , water + sound) is a microphone designed to be used underwater for recording or listening to underwater sound. Most hydrophones are based on a piezoelectric transducer that generates an electric potenti ...

arrays indicate a southward migration of the North Atlantic fin whale occurs in the autumn from the Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

-Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

region, south past Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

, and into the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. One or more populations of fin whales are thought to remain year-round in high latitudes, moving offshore, but not southward in late autumn. A study based on resightings of identified fin whales in Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

indicates that calves often learn migratory routes from their mothers and return to their mother's feeding area in subsequent years.

In the Pacific, migration patterns are poorly characterized. Although some fin whales are apparently present year-round in the Gulf of California

The Gulf of California ( es, Golfo de California), also known as the Sea of Cort├®s (''Mar de Cort├®s'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Bermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja Ca ...

, there is a significant increase in their numbers in the winter and spring. Southern fin whales migrate seasonally from relatively high-latitude Antarctic feeding grounds in the summer to low-latitude breeding and calving areas in the winter. The location of winter breeding areas is still unknown, since these whales tend to migrate in the open ocean.

Population and trends

North Atlantic

North Atlantic fin whales are defined by the

North Atlantic fin whales are defined by the International Whaling Commission

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a specialised regional fishery management organisation, established under the terms of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) to "provide for the proper conservation of ...

to exist in one of seven discrete population zones: Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

-New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

-Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

, western Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Gr├Ėnland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

, eastern Greenland-Iceland

Iceland ( is, ├Źsland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjav├Łk, which (along with its s ...

, North Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, West Norway-Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, F├Ėroyar ; da, F├”r├Ėerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

, and Ireland-Spain-United Kingdom-Portugal. Results of mark-and-recapture surveys have indicated that some movement occurs across the boundaries of these zones, suggesting that they are not entirely discrete and that some immigration and emigration does occur. Sigurj├│nsson estimated in 1995 that total pre-exploitation population size in the entire North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe and ...

ranged between 50,000 and 100,000 animals, but his research is criticized for lack of supporting data and an explanation of his reasoning. In 1977, D.E. Sergeant suggested a "primeval" aggregate total of 30,000 to 50,000 throughout the North Atlantic. Of that number, 8,000 to 9,000 would have resided in the Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

areas, with whales summering in U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

waters south of Nova Scotia presumably omitted. J. M. Breiwick estimated that the "exploitable" (above the legal size limit of 50 feet) component of the Nova Scotia population was 1,500 to 1,600 animals in 1964, reduced to only about 325 in 1973. Two aerial surveys in Canadian waters since the early 1970s gave numbers of 79 to 926 whales on the eastern Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

-Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

shelf in August 1980, and a few hundred in the northern and central Gulf of Saint Lawrence in August 1995 ŌĆō 1996. Summer estimates in the waters off western Greenland range between 500 and 2,000, and in 1974, Jonsgard considered the fin whales off Western Norway

Western Norway ( nb, Vestlandet, Vest-Norge; nn, Vest-Noreg) is the region along the Atlantic coast of southern Norway. It consists of the counties Rogaland, Vestland, and M├Ėre og Romsdal. The region has no official or political-administrativ ...

and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, F├Ėroyar ; da, F├”r├Ėerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

to "have been considerably depleted in postwar years, probably by overexploitation

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term app ...

". The population around Iceland

Iceland ( is, ├Źsland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjav├Łk, which (along with its s ...

appears to have fared much better, and in 1981, appeared to have undergone only a minor decline since the early 1960s. Surveys during the summers of 1987 and 1989 estimated of 10,000 to 11,000 between eastern Greenland and Norway. This shows a substantial recovery when compared to a survey in 1976 showing an estimate of 6,900, which was considered to be a "slight" decline since 1948. A Spanish NASS survey in 1989 of the France-Portugal-Spain sub-area estimated a summer population range at 17,355.

A possible resident group was in waters off the Cape Verde Islands in 2000 and 2001.

Mediterranean Sea

Satellite tracking revealed that those found in Pelagos Sanctuary migrate southward to off

Satellite tracking revealed that those found in Pelagos Sanctuary migrate southward to off Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, Pantelleria

Pantelleria (; Sicilian: ''Pantiddirìa'', Maltese: ''Pantellerija'' or ''Qawsra''), the ancient Cossyra or Cossura, is an Italian island and comune in the Strait of Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea, southwest of Sicily and east of the Tunis ...

, and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and also possibly winter off coastal southern Italy, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, within the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Se ...

, Aeolian Islands

The Aeolian Islands ( ; it, Isole Eolie ; scn, ├īsuli Eoli), sometimes referred to as the Lipari Islands or Lipari group ( , ) after their largest island, are a volcanic archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea north of Sicily, said to be named after ...

, and off Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Catalu├▒a ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, Cabrera Archipelago

Cabrera (, , la, Capraria) is an island in the Balearic Islands, Spain, located in the Mediterranean Sea off the southern coast of Majorca. It is a National Park. The highest point is Na Picamosques (172 m).

Cabrera is the largest island of the ...

, Libya

Libya (; ar, ┘ä┘Ŗž©┘Ŗž¦, L─½biy─ü), officially the State of Libya ( ar, ž»┘ł┘äž® ┘ä┘Ŗž©┘Ŗž¦, Dawlat L─½biy─ü), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to EgyptŌĆōLibya bo ...

, Kerkennah Islands

Kerkennah Islands ( aeb, ┘éž▒┘é┘åž® '; Ancient Greek: ''╬Ü╬ŁŽü╬║╬╣╬Į╬Į╬▒ Cercinna''; Spanish:''Querquenes'') are a group of islands lying off the east coast of Tunisia in the Gulf of Gab├©s, at . The Islands are low-lying, being no more than Abo ...

, Tuscan Archipelago, Ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately east to west ...

and adjacent gulfs (e.g. Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, ╬Ø╬Ą╬¼ŽĆ╬┐╬╗╬╣Žé, Ne├Īpolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, ΔικαΠ...

Mussi B.. Miragliuolo A.. Monzini E.. Battaglia M.. 1999Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) feeding ground in the coastal waters of Ischia (Archipelago Campano)

(pdf). The European Cetacean Society. Retrieved on 28 March 2017), winter feeding ground of

Lampedusa

Lampedusa ( , , ; scn, Lampidusa ; grc, ╬ø╬┐ŽĆ╬▒╬┤╬┐ß┐”ŽāŽā╬▒ and ╬ø╬┐ŽĆ╬▒╬┤╬┐ß┐”Žā╬▒ and ╬ø╬┐ŽĆ╬▒╬┤Žģß┐”ŽāŽā╬▒, Lopado├╗ssa; mt, Lampedu┼╝a) is the largest island of the Italian Pelagie Islands in the Mediterranean Sea.

The ''comune'' of L ...

, and whales may recolonize out of the Ligurian Sea

The Ligurian Sea ( it, Mar Ligure; french: Mer Ligurienne; lij, Mâ Ligure) is an arm of the Mediterranean Sea. It lies between the Italian Riviera (Liguria) and the island of Corsica. The sea is thought to have been named after the ancient L ...

to other areas such as in Ionian and in Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. Biology of the species along southern and southeastern parts of the basin such as off Libya

Libya (; ar, ┘ä┘Ŗž©┘Ŗž¦, L─½biy─ü), officially the State of Libya ( ar, ž»┘ł┘äž® ┘ä┘Ŗž©┘Ŗž¦, Dawlat L─½biy─ü), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to EgyptŌĆōLibya bo ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, and northern Egypt

Egypt ( ar, ┘ģžĄž▒ , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, is unclear due to lacks of scientific approaches although whales have been confirmed off the furthermost of the basin such as along in shore waters of Levantine Sea

The Levantine Sea (Arabic: ž©žŁž▒ ž¦┘äž┤ž¦┘ģ, tr, Levanten Denizi, el, ╬ś╬¼╬╗╬▒ŽāŽā╬▒ Žä╬┐Žģ ╬ø╬Ą╬▓╬¼╬ĮŽä╬Ą) is the easternmost part of the Mediterranean Sea.

Geography

The Levantine Sea is bordered by Turkey in the north and north-east co ...

including Israel

Israel (; he, ūÖų┤ū®ų░ūéū©ųĖūÉųĄū£, ; ar, žź┘Éž│┘Æž▒┘Äž¦ž”┘É┘Ŗ┘ä, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, ū×ų░ūōų┤ūÖūĀųĘū¬ ūÖų┤ū®ų░ūéū©ųĖūÉųĄū£, label=none, translit=Med─½nat Y─½sr─ü╩Š─ōl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, ┘ä┘Åž©┘Æ┘å┘Äž¦┘å, translit=lubn─ün, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, K─▒br─▒s (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

. Documented records within Turkish waters have been in very small numbers; one sighting off Antalya

Antalya () is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, fifth-most populous city in Turkey as well as the capital of Antalya Province. Located on Anatolia's southwest coast bordered by the Taurus Mountains, Antalya is the largest Turkish cit ...

in 1994 and five documented strandings as of 2016. and a recent sighting on 9 February 2021 by fishermen off the coast of Adana has been documented with images.

It has been shown that populations of Fin whales within the mediterranean have preferred feeding locations that partially overlap with high concentrations of plastic pollution

Plastic pollution is the accumulation of plastic objects and particles (e.g. plastic bottles, bags and microbeads) in the Earth's environment that adversely affects humans, wildlife and their habitat. Plastics that act as pollutants are catego ...

and microplastic

Microplastics are fragments of any type of plastic less than in length, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the European Chemicals Agency. They cause pollution by entering natural ecosystems from a v ...

debris. High concentrations of microplastics most likely overlap with Fin whales preferred feeding grounds because both microplastic and the whale's food sources are in close proximity to high trophic upwelling

Upwelling is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted surface water. The nutr ...

areas.

North Pacific

The total historical

The total historical North Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

population was estimated at 42,000 to 45,000 before the start of whaling. Of this, the population in the eastern portion of the North Pacific was estimated to be 25,000 to 27,000. By 1975, the estimate had declined to between 8,000 and 16,000. Surveys conducted in 1991, 1993, 1996, and 2001 produced estimates between 1,600 and 3,200 off California and 280 and 380 off Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

. The minimum estimate for the California-Oregon-Washington population, as defined in the ''U.S. Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments: 2005'', is about 2,500. Surveys in coastal waters of British Columbia in summers 2004 and 2005 produced abundance estimates of approximately 500 animals. Surveys near the Pribilof Islands

The Pribilof Islands (formerly the Northern Fur Seal Islands; ale, Amiq, russian: ą×čüčéčĆąŠą▓ą░ ą¤čĆąĖą▒čŗą╗ąŠą▓ą░, Ostrova Pribylova) are a group of four volcanic islands off the coast of mainland Alaska, in the Bering Sea, about north of ...

in the Bering Sea indicated a substantial increase in the local abundance of fin whales between 1975ŌĆō1978 and 1987ŌĆō1989. In 1984, the entire population was estimated to be less than 38% of its historic carrying capacity. Fin whales might have started returning to the coastal waters off British Columbia (a sighting occurred in Johnstone Strait

, image = Pacific Ranges over Johnstone Strait.jpg

, image_size = 250px

, alt =

, caption = Johnstone Strait backdropped by the Vancouver Island Ranges

, image_bathymetry = Carte baie Knight ...

in 2011) and Kodiak Island

Kodiak Island (Alutiiq: ''Qikertaq''), is a large island on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, separated from the Alaska mainland by the Shelikof Strait. The largest island in the Kodiak Archipelago, Kodiak Island is the second larges ...

. Size of the local population migrating to Hawaiian Archipelago

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, N─ü Mokupuni o HawaiŌĆśi) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

is unknown. Historically, several other wintering grounds were scattered in the North Pacific in the past, such as off the Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI; ch, Sankattan Siha Na Islas Mari├źnas; cal, Commonwealth T├®├®l Fal├║w kka Ef├Īng ll├│l Marianas), is an unincorporated territory and commonw ...

, Bonin Islands

The Bonin Islands, also known as the , are an archipelago of over 30 subtropical and tropical islands, some directly south of Tokyo, Japan and northwest of Guam. The name "Bonin Islands" comes from the Japanese word ''bunin'' (an archaic readi ...

, and Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the ┼īsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

. There was a sighting of 3 animals nearby Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and eas ...

and Palawan

Palawan (), officially the Province of Palawan ( cyo, Probinsya i'ang Palawan; tl, Lalawigan ng Palawan), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in ...

in 1999.

For Asian stocks, resident groups may exist in the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea. It is one of four seas named after common colour terms ...

and East China Sea

The East China Sea is an arm of the Western Pacific Ocean, located directly offshore from East China. It covers an area of roughly . The seaŌĆÖs northern extension between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula is the Yellow Sea, separated b ...

, and the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it h ...

(though these populations are critically endangered and the population off China, Korea, and Japan are either near extinction or in very small numbers). Very small increases in sightings have been confirmed off Shiretoko Peninsula

is located on the easternmost portion of the Japanese island of Hokkaid┼Ź, protruding into the Sea of Okhotsk. It is separated from Kunashir Island, which is now occupied by Russia, by the Nemuro Strait. The name Shiretoko is derived from the ...

, Abashiri, Kushiro

is a city in Kushiro Subprefecture on the island of Hokkaido, Japan. It serves as the subprefecture's capital and it is the most populated city in the eastern part of the island.

Geography

Mountains

* Mount Oakan

* Mount Meakan

* Mount Akan ...

, Tsushima, and Sado Island

is a city located on in Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Since 2004, the city has comprised the entire island, although not all of its total area is urbanized. Sado is the sixth largest island of Japan in area following the four main islands and Ok ...

. off Maiduru

is a city in Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 78,644 in 34817 households and a population density of 230 persons per km┬▓. The total area of the city is .

Geography

Maizuru is located in northern Kyoto Prefe ...

Studies of historical catches suggest several resident groups once existed in the North PacificŌĆöthe Baja California group and the Yellow SeaŌĆōEast China Sea (including Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the ┼īsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

and western Kyusyu

is the third-largest island of Japan's Japanese archipelago, five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa Island, Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name ...

) group. Additionally, respective groups in northern Sea of Japan and the group along Pacific coasts of Japan from Hokkaido to Sanriku

, sometimes known as , lies on the northeastern side of the island of Honshu, corresponding to today's Aomori, Iwate and parts of Miyagi Prefecture and has a long history.

The 36 bays of this irregular coastline tend to amplify the destructivenes ...

might have been resident or less migratory, as well. The only modern record among Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the ┼īsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

was of a rotten carcass beached on Ishigaki Island

, also known as ''Ishigakijima'', is a Japanese island south-west of Okinawa Hont┼Ź and the second-largest island of the Yaeyama Island group, behind Iriomote Island. It is located approximately south-west of Okinawa Hont┼Ź. It is within the ...

in 2005. Regarding Yellow Sea, a juvenile was accidentally killed along Boryeong in 2014.

There had been congregation areas among Sea of Japan to Yellow Sea such as in East Korea Bay, along eastern coasts of Korean Peninsula, and Ulleungdo

Ulleungdo (also spelled Ulreungdo; Hangul: , ) is a South Korean island 120 km (75 mi) east of the Korean Peninsula in the Sea of Japan, formerly known as the Dagelet Island or Argonaut Island in Europe.

Volcanic in origin, the rocky s ...

.

Modern sightings around the Commander Islands have been annual but not in great numbers, and whales likely to migrate through the areas rather than summering, and possible mixing of western and eastern populations are expected to occur in this waters.

South Pacific

Very little information has been revealed about the ecology of current migration from Antarctic waters are unknown, but small increases in sighting rates are confirmed off New Zealand, such as off Kaikoura, and wintering grounds may exist in further north such as inPapua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: Óż½Óż╝Óż┐Óż£ÓźĆ, ''Fij─½''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

, and off East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-weste ...

. Confirmations in Rarotonga

Rarotonga is the largest and most populous of the Cook Islands. The island is volcanic, with an area of , and is home to almost 75% of the country's population, with 13,007 of a total population of 17,434. The Cook Islands' Parliament buildings a ...

have been increased recently where interactions with humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hump ...

s occur on occasions. Finbacks are also relatively abundant along the coast of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Per├║.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

(in Chile, most notably off Los Lagos region

Los Lagos Region ( es, Regi├│n de Los Lagos , ''Region of the Lakes'') is one of Chile's 16 regions, which are first order administrative divisions, and comprises four provinces: Chilo├®, Llanquihue, Osorno and Palena. The region contains ...

such as Gulf of Corcovado

Gulf of Corcovado () is a large body of water separating the Chilo├® Island from the mainland of Chile. Geologically, it is a forearc basin that has been carved out by Quaternary glaciers. Most of the islands of Chilo├® Archipelago are located in ...

in Chilo├® National Park

Chilo├® National Park is a national park of Chile, located in the western coast of Chilo├® Island, in Los Lagos Region (region of the lakes). It encompasses an area of divided into two main sectors: the smallest, called Chepu, is in the commune ...

, , port of Mejillones

Mejillones is a Chilean port city and commune in Antofagasta Province in the Antofagasta Region. Its name is the plural form of the Spanish meaning "mussel", referring to a particularly abundant species and preferred staple food of its indigeno ...

, and Caleta Zorra

Caleta Zorra (meaning "Bay of foxes" in Spanish) is an enclosed, half-moon shaped inlet on the Pacific coast of Chilo├® Island in Los Lagos region, southern Chile. Lying north of Punta Pabellion, it is located among Punta Zorra and Punta Barranc ...