Edward Gierek on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Gierek (; 6 January 1913 – 29 July 2001) was a Polish Communist politician and ''de facto'' leader of Poland between 1970 and 1980. Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as First Secretary of the ruling

Gierek, who in 1948 was 35 and had spent 22 years abroad, was directed by the PPR authorities to return to Poland, which he did with his wife and their two sons. Working in the

Gierek, who in 1948 was 35 and had spent 22 years abroad, was directed by the PPR authorities to return to Poland, which he did with his wife and their two sons. Working in the

In March 1957, in addition to his Central Committee duties, Gierek became first secretary of the Katowice Voivodeship PZPR organization, and he kept this job until 1970. He created a personal power base in the Katowice region and became the nationally recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. On the one hand Gierek was regarded as a pragmatic, non-ideological and economic progress-oriented manager, on the other he was known for his servile attitude toward the Soviet leaders, for whom he was a source of information concerning the PZPR and its personalities. Both the industrial supremacy of Gierek's well-run

In March 1957, in addition to his Central Committee duties, Gierek became first secretary of the Katowice Voivodeship PZPR organization, and he kept this job until 1970. He created a personal power base in the Katowice region and became the nationally recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. On the one hand Gierek was regarded as a pragmatic, non-ideological and economic progress-oriented manager, on the other he was known for his servile attitude toward the Soviet leaders, for whom he was a source of information concerning the PZPR and its personalities. Both the industrial supremacy of Gierek's well-run

When the

When the

The period of Gierek's rule is notable for the rise of organized opposition in Poland. Changes in the

The period of Gierek's rule is notable for the rise of organized opposition in Poland. Changes in the  Ordered by Brezhnev not to attempt any further manipulations with prices, Gierek and his government undertook other measures to rescue the market destabilized in the summer of 1976. In August, sugar "merchandise coupons" were introduced to ration the product. The politics of "dynamic development" was over, as evidenced by such

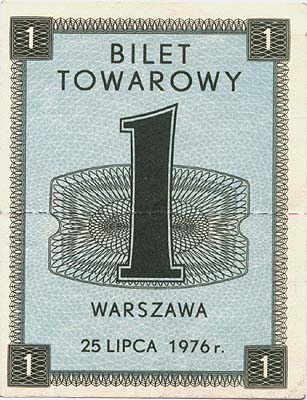

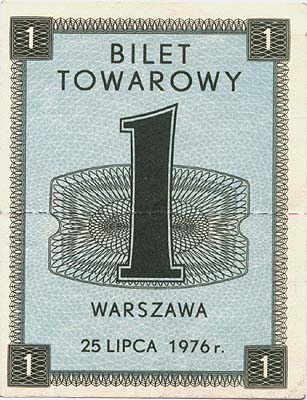

Ordered by Brezhnev not to attempt any further manipulations with prices, Gierek and his government undertook other measures to rescue the market destabilized in the summer of 1976. In August, sugar "merchandise coupons" were introduced to ration the product. The politics of "dynamic development" was over, as evidenced by such

In May 1980, after the

In May 1980, after the  Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, he was replaced by the Central Committee's VI

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, he was replaced by the Central Committee's VI

Edward Gierek, Polish Leader from Decade 1970–1980

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gierek, Edward 1913 births 2001 deaths People from Sosnowiec People from Piotrków Governorate French Communist Party members Polish Workers' Party politicians Members of the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party Members of the Polish Sejm 1952–1956 Members of the Polish Sejm 1957–1961 Members of the Polish Sejm 1961–1965 Members of the Polish Sejm 1965–1969 Members of the Polish Sejm 1969–1972 Members of the Polish Sejm 1972–1976 Members of the Polish Sejm 1976–1980 Members of the Polish Sejm 1980–1985 Recipients of the Order of the Builders of People's Poland Grand Collars of the Order of Prince Henry Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Gold Cross of Merit (Poland) Recipients of the Order of the Banner of Work Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

(PZPR) in the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million ne ...

in 1970. He is known for opening communist Poland to the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

and for his economic policies based on foreign loans. He was removed from power after labour strikes led to the Gdańsk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement (or ''Gdańsk Social Accord(s)'' or ''August Agreement(s)'', pl, Porozumienia sierpniowe) was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland. Workers along the Baltic went on strike in ...

between the communist state and workers of the emerging Solidarity free trade union movement.

Born in Sosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Indus ...

, Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. I ...

, to a devoutly Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

family, Gierek emigrated with his relatives to France at a young age. In 1934, he was deported to Poland for communist advocacy and campaigning, but subsequently moved to Belgium to work as a coal miner in Genk

Genk () is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of Limburg near Hasselt. The municipality only comprises the town of Genk itself. It is one of the most important industrial towns in Flanders, located on the Albert Canal, ...

. As a result, he was proficient in French, which benefited in pursuing his future political career. During the Second World War, Gierek was active in the Belgian Resistance

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the resistance movements opposed to the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Within Belgium, resistance was fragmented between many se ...

against the Germans. He returned to post-war Poland only in 1948 after spending 22 years abroad. In 1954, he became part of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

(PZPR) under Bolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 to 1947, President of Po ...

as a representative of the Silesian region. Known for his openness and public speaking, Gierek gradually emerged as one of the most respected and progressive politicians in the country, whilst becoming a strong opponent to more authoritarian Władysław Gomułka.

Gomułka was removed from office after the 1970 Polish protests

The 1970 Polish protests ( pl, Grudzień 1970, lit=December 1970) occurred in northern Poland during 14–19 December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase in the prices of food and other everyday items. Strikes were put down by t ...

were violently suppressed on his authority. In December 1970, Gierek was appointed the new First Secretary and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic. The first years of his term were marked by industrialization as well as the improvement of living and working conditions. Having spent time in Western Europe, he opened communist Poland to new Western ideas and loosened the censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

, thus turning Poland into the most liberal country of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. The large sums of money lent by foreign creditor

A creditor or lender is a party (e.g., person, organization, company, or government) that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some property ...

s were directed at constructing blocks of flats

A tower block, high-rise, apartment tower, residential tower, apartment block, block of flats, or office tower is a tall building, as opposed to a low-rise building and is defined differently in terms of height depending on the jurisdict ...

and at creating heavy steel and coal industries in his native Silesia. In 1976, Gierek opened the first fully-operational Polish highway from Warsaw to Katowice

Katowice ( , , ; szl, Katowicy; german: Kattowitz, yi, קאַטעוויץ, Kattevitz) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Upper Silesian metropolitan area. It is the 11th most popu ...

, which colloquially bears his name to this day. However, by the end of the 1970s Poland submerged into economic decline. The country was so heavily indebted that rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

was introduced due to shortages as the government was unable to pay off the loans. In 1980, he allowed for the Solidarity trade union

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

to appear in accordance with the Gdańsk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement (or ''Gdańsk Social Accord(s)'' or ''August Agreement(s)'', pl, Porozumienia sierpniowe) was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland. Workers along the Baltic went on strike in ...

, which formed a basis for workers' rights. Seen as a radical move to renounce communism, Gierek was removed from office like his predecessor.

Despite dragging Poland into financial and economic decline, Edward Gierek is fondly remembered for his patriotism and modernization policies; over 1.8 million flats were constructed to house the growing population, and he is also responsible for initiating the production of Fiat 126

The Fiat 126 (Type 126) is a four-passenger, rear-engine, city car manufactured and marketed by Fiat over a twenty-eight year production run from 1972 until 2000, over a single generation. Introduced by Fiat in October 1972 at the Turin Auto Show ...

in Poland and the erection of Warszawa Centralna railway station

Warszawa Centralna, in English known as Warsaw Central Station, is the primary railway station in Warsaw, Poland. Completed in 1975, the station is located on the Warsaw Cross-City Line and features four underground island platforms with eight tr ...

, the most modern European station at the time of its completion in 1975. Numerous aphorisms and sayings were popularized under his term, in particular the ones referring to the food shortages were later promoted by Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

.

Youth and early career

Edward Gierek was born in Porąbka, now part ofSosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Indus ...

, into a coal mining family. He lost his father to a mining accident in a pit at the age of four. His mother remarried and emigrated to northern France, where he lived from the age of 10 and worked in a coal mine from the age of 13. Gierek joined the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European ...

in 1931 and in 1934 was deported to Poland for organizing a strike. After completing compulsory military service in Stryi

Stryi ( uk, Стрий, ; pl, Stryj) is a city located on the left bank of the river Stryi in Lviv Oblast (region) of western Ukraine 65 km to the south of Lviv (in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains). It serves as the administrative cen ...

in southeastern Poland (1934–1936), Gierek married Stanisława Jędrusik, but was unable to find employment. The Giereks went to Belgium, where Edward worked in the coal mines of Waterschei, contracting pneumoconiosis

Pneumoconiosis is the general term for a class of interstitial lung disease where inhalation of dust ( for example, ash dust, lead particles, pollen grains etc) has caused interstitial fibrosis. The three most common types are asbestosis, silico ...

(black lung disease) in the process. In 1939 Gierek joined the Communist Party of Belgium

french: Parti Communiste de Belgique

, abbreviation = KPB-PCB

, colorcode =

, leader1_title = Historical leaders

, leader1_name = Joseph JacquemotteJulien LahautLouis Van Geyt

, founder = Julien Lahaut

, founded =

, dissolved =

, merge ...

. During the German occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 ...

, he participated in communist anti-Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

Belgian resistance activities. After the war Gierek remained politically active among the Polish immigrant community. He was a co-founder of the Belgian branch of the Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 194 ...

(PPR) and a chairman of the National Council of Poles in Belgium.

Polish United Workers' Party activist

Gierek, who in 1948 was 35 and had spent 22 years abroad, was directed by the PPR authorities to return to Poland, which he did with his wife and their two sons. Working in the

Gierek, who in 1948 was 35 and had spent 22 years abroad, was directed by the PPR authorities to return to Poland, which he did with his wife and their two sons. Working in the Katowice

Katowice ( , , ; szl, Katowicy; german: Kattowitz, yi, קאַטעוויץ, Kattevitz) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Upper Silesian metropolitan area. It is the 11th most popu ...

district PPR organization, in December 1948, as a Sosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Indus ...

delegate he participated in the PPR- PPS unification congress, which resulted in the establishment of the Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

(PZPR). In 1949, he was designated for and attended a two-year higher party course in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

, where he was judged to be poorly qualified for intellectual endeavors but highly motivated for party work. In 1951 Roman Zambrowski

Roman Zambrowski (born Rubin Nassbaum; 15 July 1909 – 19 August 1977) was a Polish communist politician.

Career

Zambrowski was born into a Jewish family in Warsaw. He was a member of the Communist Party of Poland (1928–1938) and of the Cen ...

sent Gierek to a striking coal mine, charging him with restoring order. Gierek was able to resolve the situation using persuasion and a use of force was avoided. He was a member of the ''Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

'', Polish parliament, from 1952. During the II Congress of the PZPR (March 1954), he was elected a member of the party's Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party organizations, the ...

. As chief of the Central Committee's Heavy Industry Division, he worked directly under First Secretary Bolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 to 1947, President of Po ...

in Warsaw.

In March 1956, when Edward Ochab

Edward Ochab (; 16 August 1906 – 1 May 1989) was a Polish communist politician and top leader of Poland between March and October 1956.

As a member of the Communist Party of Poland from 1929, he was repeatedly imprisoned for his activities u ...

became the party's first secretary, Gierek became a secretary of the Central Committee, even though he publicly expressed doubts about his own qualifications. On 28 June 1956 he was sent to Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

, where a workers' protest was taking place. Afterwards, delegated by the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

, he headed the commission charged with investigating the causes and course of the Poznań events. They presented their report on 7 July, blaming a hostile anti-socialist foreign inspired conspiracy that took advantage of worker discontent in Poznań enterprises. In July Gierek became a member of the PZPR Politburo, but lasted in that position only until October, when Władysław Gomułka replaced Ochab as first secretary. Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

criticized Gomułka for not retaining Gierek in the Politburo; he remained a Central Committee secretary responsible for economic affairs, however. He would return to the Politburo in March 1959, at the III Congress of the PZPR.

Katowice industrial district leader

In March 1957, in addition to his Central Committee duties, Gierek became first secretary of the Katowice Voivodeship PZPR organization, and he kept this job until 1970. He created a personal power base in the Katowice region and became the nationally recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. On the one hand Gierek was regarded as a pragmatic, non-ideological and economic progress-oriented manager, on the other he was known for his servile attitude toward the Soviet leaders, for whom he was a source of information concerning the PZPR and its personalities. Both the industrial supremacy of Gierek's well-run

In March 1957, in addition to his Central Committee duties, Gierek became first secretary of the Katowice Voivodeship PZPR organization, and he kept this job until 1970. He created a personal power base in the Katowice region and became the nationally recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. On the one hand Gierek was regarded as a pragmatic, non-ideological and economic progress-oriented manager, on the other he was known for his servile attitude toward the Soviet leaders, for whom he was a source of information concerning the PZPR and its personalities. Both the industrial supremacy of Gierek's well-run Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

territory and the special relationship with the Soviets he cultivated made many believe that Gierek was a likely successor to Gomułka.

The Warsaw University law professor Mieczysław Maneli who knew Gierek from 1960 onward wrote about him in 1971: "Edward Gierek is an old‐fashioned Communist, but without fanaticism or zealousness. His Marxism is encumbered by few dogmas. It is almost pragmatic. He believes profoundly in the leading role that history conferred upon Communist parties and lives by the maxim that a government should be strong and rule unshakably...Gierek's party nickname was “Tshombe,” and Silesia was the “Polish Katanga.” There he operated almost as a sovereign prince, a talented organizer with a real gift for finding efficient and loyal henchmen. All professions were represented in his court: engineers, economists, professors, writers, party apparatchiks and security agents".

Gierek may have tried to make his move during the 1968 Polish political crisis

The Polish 1968 political crisis, also known in Poland as March 1968, Students' March, or March events ( pl, Marzec 1968; studencki Marzec; wydarzenia marcowe), was a series of major student, intellectual and other protests against the ruling Pol ...

. Soon after the student rally on 8 March in Warsaw, on 14 March in Katowice he led a mass gathering of 100,000 party members from the entire province. He was the first Politburo member to speak publicly on the issue of the protests then taking place and later claimed that his motivation was to demonstrate support for Gomułka's rule, threatened by Mieczysław Moczar

Mieczysław Moczar (; birth name Mikołaj Diomko, pseudonym ''Mietek'', 23 December 1913 in – 1 November 1986) was a Polish communist politician who played a prominent role in the history of the Polish People's Republic. He is most known for h ...

's intra-party conspiring. Gierek used strong language to condemn the purported "enemies of People's Poland" who were "disturbing the peaceful Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

n water". He showered them with propaganda epithets and alluded to their bones being crushed if they persevered in their attempts to turn the "nation" away from its "chosen course." Gierek was supposedly embarrassed when participants of the party conference in Warsaw on 19 March shouted his name along with that of Gomułka, as an expression of support. The 1968 events strengthened Gierek's position, also in the eyes of his sponsors in Moscow.

First secretary of the PZPR

When the

When the 1970 Polish protests

The 1970 Polish protests ( pl, Grudzień 1970, lit=December 1970) occurred in northern Poland during 14–19 December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase in the prices of food and other everyday items. Strikes were put down by t ...

were violently suppressed, Gierek replaced Gomułka as first secretary of the party and had thus become the most powerful politician in Poland. In late January 1971, he put his new authority on the line and traveled to Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

, to bargain personally with the striking workers. Consumer price increases that triggered the recent revolt were rescinded. Among Gierek's popular moves was the decision to rebuild the Royal Castle in Warsaw

The Royal Castle in Warsaw ( pl, Zamek Królewski w Warszawie) is a state museum and a national historical monument, which formerly served as the official royal residence of several Polish monarchs. The personal offices of the king and the admi ...

, destroyed during World War II and not included in the post-war restoration of the city's Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

. State controlled media stressed his foreign upbringing and his fluency in the French language.

The arrival of the Gierek team meant the final generational replacement of the ruling communist elite, a process begun in 1968 under Gomułka. Many thousands of party activists, including important elder leaders with background in the prewar Communist Party of Poland, were removed from positions of responsibility and replaced with people whose careers formed after World War II. Much of the overhaul was accomplished during and after the VI Congress of the PZPR, convened in December 1971. The resulting governing class was one of the youngest in Europe. The role of the administration was expanded at the expense of the party, according to the maxim "the party leads, the government governs". Throughout the 1970s, the most highly visible member of the top leadership after Gierek was Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz. From May 1971, Gierek's rival party politician Mieczysław Moczar was increasingly marginalized.

According to historian Krzysztof Pomian, early in his term Gierek abandoned the regime's long-standing practice of on-and-off confrontation with the Polish Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, and opted for cooperation. The policy resulted in a privileged position of the Church and its leaders for the duration of the communist rule in Poland. The Church markedly expanded its physical infrastructure and also became a crucial political third force, often involved in mediating conflict between the authorities and opposition activists.

Economic expansion and decline

Since the riots that brought down Gomułka were caused primarily by economic difficulties, Gierek promised economic reform and instituted a program to modernize industry and increase the availability of consumer goods. His "reform" was based primarily on large scale foreign borrowing, not accompanied by major systemic restructuring. The need for deeper reform was obscured by the investment boom the country was enjoying in the first half of the 1970s. The first secretary's good relations with Western leaders, especially France'sValéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

's Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt (; 23 December 1918 – 10 November 2015) was a German politician and member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who served as the chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982.

Before becoming Ch ...

, were a catalyst for his receiving foreign aid and loans. Gierek is widely credited with opening Poland to political and economic influence from the Western Bloc. He himself extensively traveled abroad and received important foreign guests in Poland, including three presidents of the United States. Gierek also was trusted by Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1 ...

, which meant that he was able to pursue his policies (globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

of Poland's economy) without much Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

interference. He had readily granted the Soviets concessions that his predecessor Gomułka would consider contrary to the Polish national interest.

Standard of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

increased markedly in Poland in the first half of the 1970s, and for a time Gierek was hailed as a miracle-worker. Poles, to an unprecedented degree, were able to purchase desired consumer items such as compact cars, travel to the West rather freely, and even a solution to the intractable housing supply problem seemed to be on the horizon. Decades later many remembered the period as the most prosperous in their lives. The economy, however, began to falter during the 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had su ...

, and by 1976 price increases became necessary. The June 1976 protests

The June 1976 protests were a series of protests and demonstrations in the Polish People's Republic that took place after Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz revealed the plan for a sudden increase in the price of many basic commodities,

were brutally suppressed by police, but the planned price increases were canceled. The greatest accumulation of foreign debt occurred in the late 1970s, as the regime struggled to counter the effects of the crisis.

Crisis, protests, organized opposition

The period of Gierek's rule is notable for the rise of organized opposition in Poland. Changes in the

The period of Gierek's rule is notable for the rise of organized opposition in Poland. Changes in the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, proposed by the regime, caused considerable controversy at the turn of 1975 and 1976. The intended amendments included formalizing the "socialist character of the state", the leading role of the PZPR and the Polish-Soviet alliance. The widely opposed alterations resulted in numerous protest letters and other actions, but were supported at the VII Congress of the PZPR in December 1975 and largely implemented by the ''Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

'' in February 1976. Organized opposition circles developed gradually and reached 3000–4000 members by the end of the decade.

Because of the deteriorating economic situation, at the end of 1975 the authorities announced that the 1971 freeze in food prices

Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale. Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing ...

would have to be lifted. Prime Minister Jaroszewicz forced the price rises, in combination with financial compensation favoring upper income brackets; the policy ultimately was adopted despite strong objections voiced by the Soviet leadership. The increase, supported by Gierek, was announced by Jaroszewicz in the ''Sejm'' on 24 June 1976. Strikes broke out the following day, with particularly serious disturbances, brutally suppressed by police, taking place in Radom

Radom is a city in east-central Poland, located approximately south of the capital, Warsaw. It is situated on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been the seat of a separate Radom Voivodeship (1975� ...

, at Warsaw's Ursus Factory

Ursus SA (often stylized URSUS SA) is a Polish agricultural machinery manufacturer, headquartered in Lublin, Poland. The company was founded in Warsaw in 1893, and has strong historic roots regarding Polish tractor production history. It has al ...

and in Płock

Płock (pronounced ) is a city in central Poland, on the Vistula river, in the Masovian Voivodeship. According to the data provided by GUS on 31 December 2021, there were 116,962 inhabitants in the city. Its full ceremonial name, according to th ...

. On 26 June, Gierek engaged in the traditional party crisis-confronting mode of operation, ordering mass public gatherings in Polish cities to demonstrate people's supposed support for the party and condemn the "trouble makers".

Ordered by Brezhnev not to attempt any further manipulations with prices, Gierek and his government undertook other measures to rescue the market destabilized in the summer of 1976. In August, sugar "merchandise coupons" were introduced to ration the product. The politics of "dynamic development" was over, as evidenced by such

Ordered by Brezhnev not to attempt any further manipulations with prices, Gierek and his government undertook other measures to rescue the market destabilized in the summer of 1976. In August, sugar "merchandise coupons" were introduced to ration the product. The politics of "dynamic development" was over, as evidenced by such ration cards

A ration stamp, ration coupon or ration card is a stamp or card issued by a government to allow the holder to obtain food or other commodities that are in short supply during wartime or in other emergency situations when rationing is in for ...

, which would remain a part of Poland's daily reality until July 1989.

In the aftermath of the June 1976 protests, a major opposition group, the Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), commenced its activities in September to help the persecuted worker protest participants. Other opposition organizations were also established in 1977–79, but historically the KOR proved to be of particular importance.

In 1979, Poland's ruling communists reluctantly allowed Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

to make his first papal visit to Poland (2–10 June), despite Soviet advice to the contrary. Gierek, who had previously met Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

at the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

, talked with the Pope on the occasion of his visit.

Downfall

Although Gierek, distressed by the 1976 price increase policy failure, was persuaded by his colleagues not to resign, divisions within his team intensified. One faction, led by Edward Babiuch and Piotr Jaroszewicz, wanted him to remain at the helm, while another, led by Stanisław Kania andWojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party b ...

, was less interested in preserving his leadership.

In May 1980, after the

In May 1980, after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

and the subsequent Western boycott of the Soviet Union, Gierek arranged a meeting between Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

and Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1 ...

in Warsaw. As was the case with Władysław Gomułka a decade earlier, a foreign policy success created an illusion that the Polish party leader was secure in his statesman aura, while the paramount political facts were being determined by the deteriorating economic situation and the resultant labor unrest. In July Gierek went to the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, his usual vacation spot. For the last time he talked there with his friend Brezhnev. He responded to Brezhnev's gloomy assessment of the situation in Poland (including the out-of-control indebtedness) with his own upbeat predictions, possibly not fully cognizant of the country's, and his own, predicament.

High foreign debts, food shortages, and an outmoded industrial base were among the factors that forced a new round of economic reforms. Once again, in the summer of 1980 price increases set off protests across the country, especially in the Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

and Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

shipyards

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

. Unlike on previous occasions, the regime decided not to resort to force to suppress the strikes. In the Gdańsk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement (or ''Gdańsk Social Accord(s)'' or ''August Agreement(s)'', pl, Porozumienia sierpniowe) was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland. Workers along the Baltic went on strike in ...

and other accords reached with Polish workers, Gierek was forced to concede their right to strike, and the Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

labor union was born.

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, he was replaced by the Central Committee's VI

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, he was replaced by the Central Committee's VI Plenum

Plenum may refer to:

* Plenum chamber, a chamber intended to contain air, gas, or liquid at positive pressure

* Plenism, or ''Horror vacui'' (physics) the concept that "nature abhors a vacuum"

* Plenum (meeting), a meeting of a deliberative asse ...

as party first secretary by Stanisław Kania and removed from power. A popular and trusted leader in the early 1970s, Gierek left surrounded by infamy and ridicule, deserted by most of his collaborators. The VII Plenum in December 1980 held Gierek and Jaroszewicz personally liable for the situation in the country and removed them from the Central Committee. The extraordinary IX Congress of the PZPR, in an unprecedented move, voted in July 1981 to expel Gierek and his close associates from the party, as the delegates considered them responsible for the Solidarity-related crisis in Poland, and First Secretary Kania was unable to prevent their action. The next first secretary of the PZPR, General Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party b ...

, introduced martial law in Poland on 13 December 1981. Gierek was interned for a year from December 1981. Unlike the (also-interned) opposition activists, the internment status brought Gierek no social respect. He ended his political career as the era's main pariah.

Edward Gierek died in July 2001 of the miner's lung illness in a hospital in Cieszyn

Cieszyn ( , ; cs, Těšín ; german: Teschen; la, Tessin; szl, Ćeszyn) is a border town in southern Poland on the east bank of the Olza River, and the administrative seat of Cieszyn County, Silesian Voivodeship. The town has 33,500 inhabitan ...

, near the southern mountain resort of Ustroń

Ustroń (german: Ustron) is a health resort town in Cieszyn Silesia, southern Poland. It is situated in the Silesian Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been in Bielsko-Biała Voivodeship (1975–1998). It lies in the Silesian Beskids ...

where he spent his last years. From the perspective of time his rule was now seen in a more positive light and over ten thousand people attended his funeral.

With his lifelong wife, Stanisława ''née'' Jędrusik, Gierek had two sons, one of whom is MEP Adam Gierek.

Legacy

In 1990 two books, based on extended interviews with Gierek by Janusz Rolicki, were published in Poland and became bestsellers. Polish society is divided in its assessment of Gierek. His government is fondly remembered by some for the improved living standards the Poles enjoyed in the 1970s under his rule. Uniquely among the PZPR leaders, the Polish public has shown signs of Gierek nostalgia, discernible especially after the former first secretary's death. Others emphasize that the improvements were only made possible by the unwise and unsustainable policies based on huge foreign loans, which led directly to the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s. Judged by hindsight, the total sum of over 24 billion borrowed (in 1970s dollars) was not well-spent. Upon becoming first secretary in December 1970, Gierek promised himself that under his watch people would not be shot on streets. In 1976 the security forces did intervene in strikes, but only after giving up their firearms. In 1980, they did not use force at all. According to sociologist and left-wing politician Maciej Gdula, the social and cultural transformation that took place in Poland in the 1970s was even more fundamental than the one which occurred in the 1990s, following the political transition. Regarding the politics of alliance of the political and later also money elites with themiddle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

at the expense of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

, he said "the general idea of the relationship of forces in our society has remained the same from the 1970s, and the period of mass solidarity was an exception" ("mass solidarity" being the years 1980–81). Since the time of Gierek, Polish society has been hegemonized by cultural perceptions and norms of the (at that time emerging) middle class. Terms like management, initiative, personality, or the individualistic

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relianc ...

maxim "get educated, work hard and get ahead in life", combined with orderliness, replaced class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

and the socialist egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

concept, as workers were losing their symbolic status, to be eventually separated into a marginalized stratum.

Decorations and awards

;Poland ;Foreign AwardsSee also

* History of Poland (1945–89)References

External links

Edward Gierek, Polish Leader from Decade 1970–1980

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gierek, Edward 1913 births 2001 deaths People from Sosnowiec People from Piotrków Governorate French Communist Party members Polish Workers' Party politicians Members of the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party Members of the Polish Sejm 1952–1956 Members of the Polish Sejm 1957–1961 Members of the Polish Sejm 1961–1965 Members of the Polish Sejm 1965–1969 Members of the Polish Sejm 1969–1972 Members of the Polish Sejm 1972–1976 Members of the Polish Sejm 1976–1980 Members of the Polish Sejm 1980–1985 Recipients of the Order of the Builders of People's Poland Grand Collars of the Order of Prince Henry Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Gold Cross of Merit (Poland) Recipients of the Order of the Banner of Work Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur