Evolution is change in the

heritable

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inf ...

characteristics of biological

population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using ...

s over successive generations. These characteristics are the

expressions of

gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s, which are passed on from parent to offspring during

reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – " offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual o ...

.

Variation

Variation or Variations may refer to:

Science and mathematics

* Variation (astronomy), any perturbation of the mean motion or orbit of a planet or satellite, particularly of the moon

* Genetic variation, the difference in DNA among individual ...

tends to exist within any given population as a result of genetic

mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, m ...

and

recombination.

Evolution occurs when evolutionary processes such as

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

(including

sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex (in ...

) and

genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

act on this variation, resulting in certain characteristics becoming more common or more rare within a population.

The

evolutionary pressure

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

s that determine whether a characteristic is common or rare within a population constantly change, resulting in a change in heritable characteristics arising over successive generations. It is this process of evolution that has given rise to

biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity' ...

at every level of

biological organisation

Biological organisation is the hierarchy of complex biological structures and systems that define life using a reductionistic approach. The traditional hierarchy, as detailed below, extends from atoms to biospheres. The higher levels of this ...

, including the levels of

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

, individual

organism

In biology, an organism () is any life, living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy (biology), taxonomy into groups such as Multicellular o ...

s, and

molecules

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioc ...

.

The

theory

A theory is a rational type of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the results of such thinking. The process of contemplative and rational thinking is often associated with such processes as observational study or research. Theories may ...

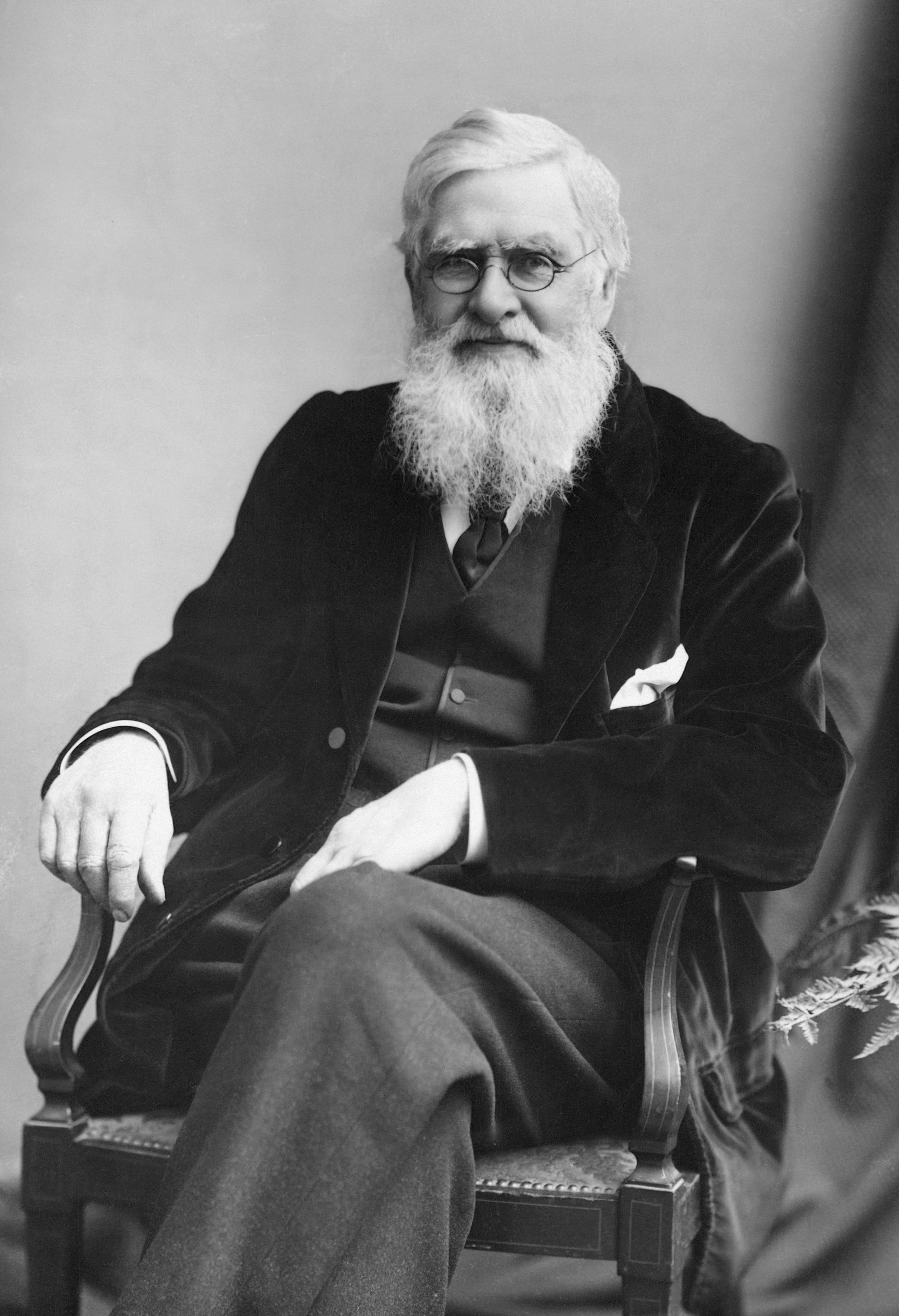

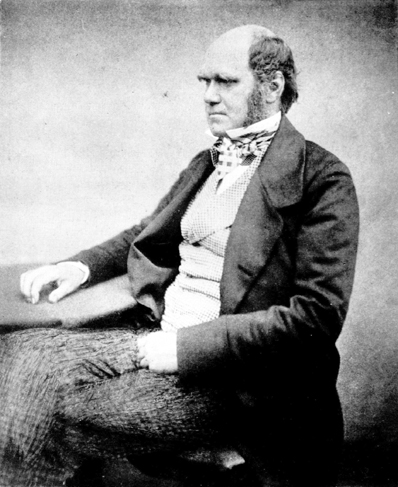

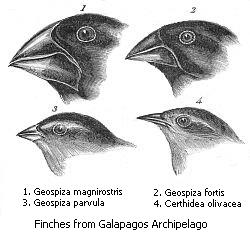

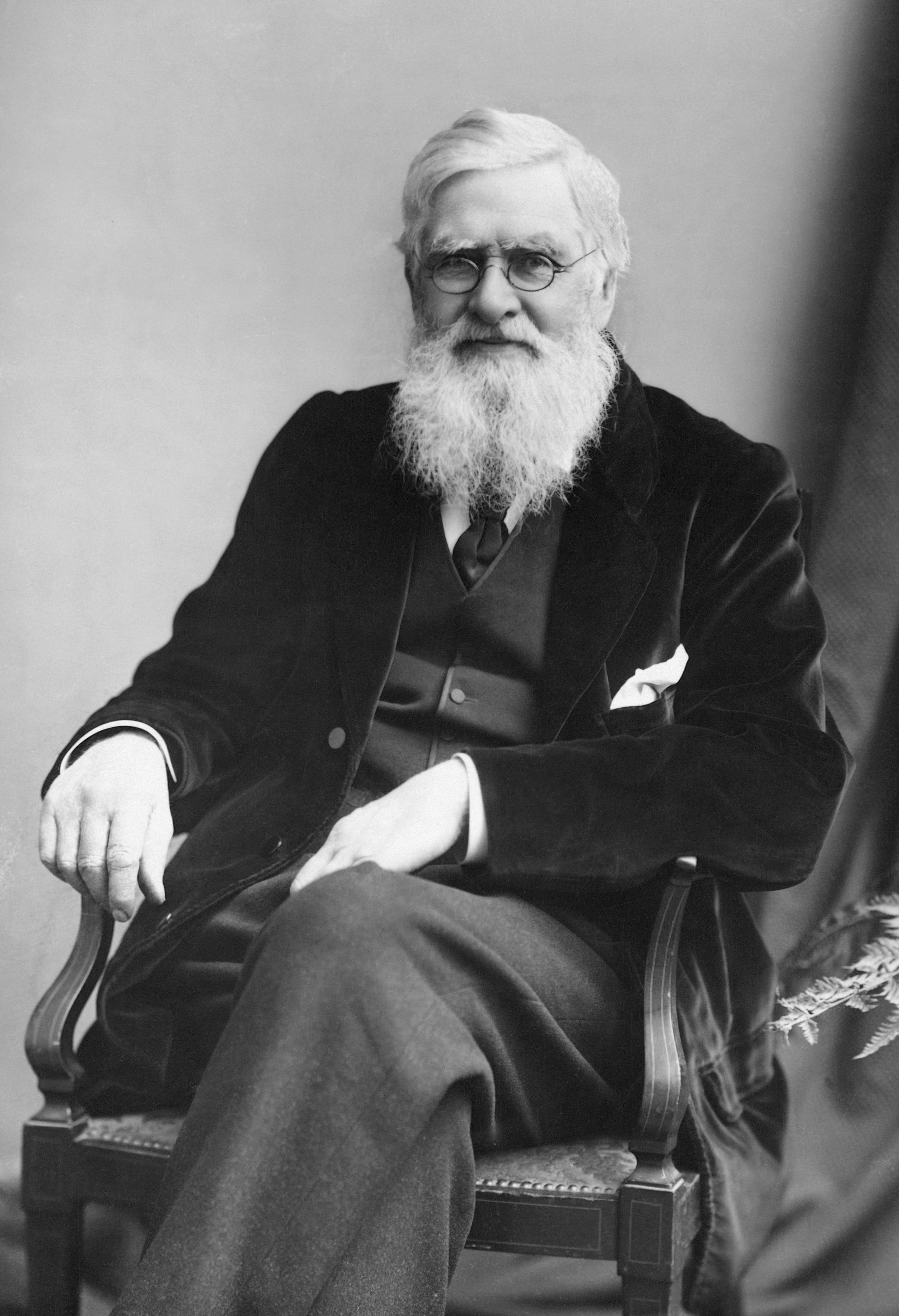

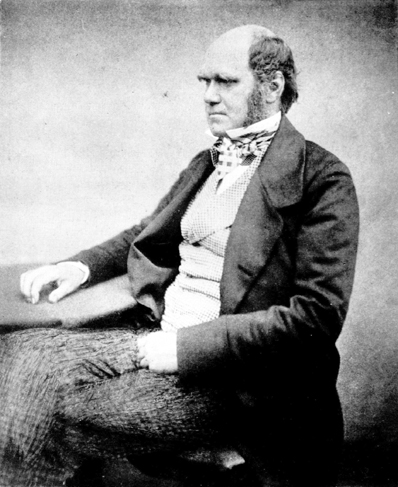

of evolution by natural selection was conceived independently by

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

and

Alfred Russel Wallace in the mid-19th century and was set out in detail in Darwin's book ''

On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''. Evolution by natural selection is established by observable facts about living organisms: (1) more offspring are often produced than can possibly survive (2) traits vary among individuals with respect to their

morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

,

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

, and behaviour (

phenotypic variation

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological prop ...

); (3) different traits confer different rates of survival and reproduction (differential

fitness); and (4) traits can be passed from generation to generation (

heritability of fitness).

In successive generations, members of a population are therefore more likely to be replaced by the

offspring

In biology, offspring are the young creation of living organisms, produced either by a single organism or, in the case of sexual reproduction, two organisms. Collective offspring may be known as a brood or progeny in a more general way. This ca ...

of parents with favourable characteristics. In the early 20th century, other

competing ideas of evolution such as

mutationism

Mutationism is one of several alternatives to evolution by natural selection that have existed both before and after the publication of Charles Darwin's 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species''. In the theory, mutation was the source of novelty, cr ...

and

orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some go ...

were

refuted as the

modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

concluded

Darwinian evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

acts on

Mendelian

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later populari ...

genetic variation.

All

life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

on Earth shares a

last universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; ...

(LUCA),

which lived approximately 3.5–3.8 billion years ago.

The

fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

includes a progression from early

biogenic

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on la ...

to

microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet of microorganisms, mainly bacteria and archaea, or bacteria alone. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few survive in desert ...

fossils

to fossilised

multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially un ...

s. Existing patterns of biodiversity have been shaped by repeated formations of new species (

speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution withi ...

), changes within species (

anagenesis

Anagenesis is the gradual evolution of a species that continues to exist as an interbreeding population. This contrasts with cladogenesis, which occurs when there is branching or splitting, leading to two or more lineages and resulting in separat ...

), and loss of species (

extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds ( taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed ...

) throughout the

evolutionary history of life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for '' gigaannum'') and evid ...

on Earth.

and

biochemical

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology ...

traits are more similar among species that share a more

recent common ancestor, and these traits can be used to reconstruct

phylogenetic trees.

Evolutionary biologists

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life form ...

have continued to study various aspects of evolution by forming and testing

hypotheses

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obser ...

as well as constructing theories based on

evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports this proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the supported proposition is true. What role evidence plays and how it is conceived varies from field to field.

In epistemology, eviden ...

from the field or laboratory and on data generated by the methods of

mathematical and theoretical biology

Mathematical and theoretical biology, or biomathematics, is a branch of biology which employs theoretical analysis, mathematical models and abstractions of the living organisms to investigate the principles that govern the structure, development a ...

. Their discoveries have influenced not just the development of

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

but numerous other scientific and industrial fields, including

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peop ...

,

medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

, and

computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to practical disciplines (includin ...

.

Heredity

Evolution in organisms occurs through changes in heritable traits—the inherited characteristics of an organism. In humans, for example,

eye colour is an inherited characteristic and an individual might inherit the "brown-eye trait" from one of their parents. Inherited traits are controlled by genes and the complete set of genes within an organism's

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

(genetic material) is called its genotype.

The complete set of observable traits that make up the structure and behaviour of an organism is called its phenotype. These traits come from the interaction of its genotype with the environment. As a result, many aspects of an organism's phenotype are not inherited. For example,

suntanned

Sun tanning or tanning is the process whereby Human skin color, skin color is darkened or tanned. It is most often a result of exposure to ultraviolet radiation, ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight or from artificial sources, such as a ta ...

skin comes from the interaction between a person's genotype and sunlight; thus, suntans are not passed on to people's children. However, some people tan more easily than others, due to differences in genotypic variation; a striking example are people with the inherited trait of

albinism

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

, who do not tan at all and are very sensitive to

sunburn

Sunburn is a form of radiation burn that affects living tissue, such as skin, that results from an overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, usually from the Sun. Common symptoms in humans and animals include: red or reddish skin that i ...

.

Heritable traits are passed from one generation to the next via DNA, a

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

that encodes genetic information.

DNA is a long

biopolymer

Biopolymers are natural polymers produced by the cells of living organisms. Like other polymers, biopolymers consist of monomeric units that are covalently bonded in chains to form larger molecules. There are three main classes of biopolymers ...

composed of four types of bases. The sequence of bases along a particular DNA molecule specifies the genetic information, in a manner similar to a sequence of letters spelling out a sentence. Before a cell divides, the DNA is copied, so that each of the resulting two cells will inherit the DNA sequence. Portions of a DNA molecule that specify a single functional unit are called genes; different genes have different sequences of bases. Within cells, the long strands of DNA form condensed structures called

chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

s. The specific location of a DNA sequence within a chromosome is known as a

locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award ...

. If the DNA sequence at a locus varies between individuals, the different forms of this sequence are called alleles. DNA sequences can change through mutations, producing new alleles. If a mutation occurs within a gene, the new allele may affect the trait that the gene controls, altering the phenotype of the organism.

However, while this simple correspondence between an allele and a trait works in some cases, most traits are more complex and are controlled by

quantitative trait loci

A quantitative trait locus (QTL) is a locus (section of DNA) that correlates with variation of a quantitative trait in the phenotype of a population of organisms. QTLs are mapped by identifying which molecular markers (such as SNPs or AFLPs) ...

(multiple interacting genes).

Some heritable changes cannot be explained by changes to the sequence of

nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecul ...

s in the DNA. These phenomena are classed as epigenetic inheritance systems.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a biological process by which methyl groups are added to the DNA molecule. Methylation can change the activity of a DNA segment without changing the sequence. When located in a gene promoter, DNA methylation typically acts ...

marking

chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important ...

, self-sustaining metabolic loops, gene silencing by

RNA interference

RNA interference (RNAi) is a biological process in which RNA molecules are involved in sequence-specific suppression of gene expression by double-stranded RNA, through translational or transcriptional repression. Historically, RNAi was known by o ...

and the three-dimensional

conformation of

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s (such as

prion

Prions are misfolded proteins that have the ability to transmit their misfolded shape onto normal variants of the same protein. They characterize several fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative diseases in humans and many other animals. It ...

s) are areas where epigenetic inheritance systems have been discovered at the organismic level.

Developmental biologists suggest that complex interactions in

genetic networks and communication among cells can lead to heritable variations that may underlay some of the mechanics in

developmental plasticity

Developmental plasticity is a general term referring to changes in neural connections during development as a result of environmental interactions as well as neural changes induced by learning. Much like neuroplasticity or brain plasticity, develo ...

and

canalisation.

Heritability may also occur at even larger scales. For example, ecological inheritance through the process of

niche construction

Niche construction is the process by which an organism alters its own (or another species') local environment. These alterations can be a physical change to the organism’s environment or encompass when an organism actively moves from one habita ...

is defined by the regular and repeated activities of organisms in their environment. This generates a legacy of effects that modify and feed back into the selection regime of subsequent generations. Descendants inherit genes plus environmental characteristics generated by the ecological actions of ancestors.

Other examples of heritability in evolution that are not under the direct control of genes include the inheritance of cultural traits and

symbiogenesis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory,) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and pos ...

.

Sources of variation

Evolution can occur if there is

genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources of genetic variation, b ...

within a population. Variation comes from mutations in the genome, reshuffling of genes through

sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote th ...

and migration between populations (

gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalen ...

). Despite the constant introduction of new variation through mutation and gene flow, most of the genome of a species is identical in all individuals of that species. However, even relatively small differences in genotype can lead to dramatic differences in phenotype: for example, chimpanzees and humans differ in only about 5% of their genomes.

An individual organism's phenotype results from both its genotype and the influence of the environment it has lived in. A substantial part of the phenotypic variation in a population is caused by genotypic variation.

The modern evolutionary synthesis defines evolution as the change over time in this genetic variation. The frequency of one particular allele will become more or less prevalent relative to other forms of that gene. Variation disappears when a new allele reaches the point of

fixation—when it either disappears from the population or replaces the ancestral allele entirely.

Before the discovery of Mendelian genetics, one common hypothesis was

blending inheritance

Blending may refer to:

* The process of mixing in process engineering

* Mixing paints to achieve a greater range of colors

* Blending (alcohol production), a technique to produce alcoholic beverages by mixing different brews

* Blending (linguis ...

. But with blending inheritance, genetic variation would be rapidly lost, making evolution by natural selection implausible. The

Hardy–Weinberg principle

In population genetics, the Hardy–Weinberg principle, also known as the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, model, theorem, or law, states that allele and genotype frequencies in a population will remain constant from generation to generation in t ...

provides the solution to how variation is maintained in a population with Mendelian inheritance. The frequencies of alleles (variations in a gene) will remain constant in the absence of selection, mutation, migration and genetic drift.

Mutation

Mutations are changes in the DNA sequence of a cell's genome and are the ultimate source of genetic variation in all organisms.

When mutations occur, they may alter the

product of a gene, or prevent the gene from functioning, or have no effect. Based on studies in the fly ''

Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the " vinegar fly" or " pomace fly". Starting with ...

'', it has been suggested that if a mutation changes a protein produced by a gene, this will probably be harmful, with about 70% of these mutations having damaging effects, and the remainder being either neutral or weakly beneficial.

Mutations can involve large sections of a chromosome becoming

duplicated (usually by

genetic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukary ...

), which can introduce extra copies of a gene into a genome. Extra copies of genes are a major source of the raw material needed for new genes to evolve. This is important because most new genes evolve within

gene families

A gene family is a set of several similar genes, formed by duplication of a single original gene, and generally with similar biochemical functions. One such family are the genes for human hemoglobin subunits; the ten genes are in two clusters on ...

from pre-existing genes that share common ancestors. For example, the human

eye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

uses four genes to make structures that sense light: three for

colour vision

Color vision, a feature of visual perception, is an ability to perceive differences between light composed of different wavelengths (i.e., different spectral power distributions) independently of light intensity. Color perception is a part of t ...

and one for

night vision

Night vision is the ability to see in low-light conditions, either naturally with scotopic vision or through a night-vision device. Night vision requires both sufficient spectral range and sufficient intensity range. Humans have poor night ...

; all four are descended from a single ancestral gene.

New genes can be generated from an ancestral gene when a duplicate copy mutates and acquires a new function. This process is easier once a gene has been duplicated because it increases the

redundancy of the system; one gene in the pair can acquire a new function while the other copy continues to perform its original function. Other types of mutations can even generate entirely new genes from previously noncoding DNA, a phenomenon termed

de novo gene birth

''De novo'' gene birth is the process by which new genes evolve from DNA sequences that were ancestrally non-genic. '' De novo'' genes represent a subset of novel genes, and may be protein-coding or instead act as RNA genes. The processes tha ...

.

The generation of new genes can also involve small parts of several genes being duplicated, with these fragments then recombining to form new combinations with new functions (

exon shuffling). When new genes are assembled from shuffling pre-existing parts,

domains act as modules with simple independent functions, which can be mixed together to produce new combinations with new and complex functions. For example,

polyketide synthase

Polyketides are a class of natural products derived from a precursor molecule consisting of a chain of alternating ketone (or reduced forms of a ketone) and methylene groups: (-CO-CH2-). First studied in the early 20th century, discovery, biosynth ...

s are large

enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecule ...

s that make

antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

; they contain up to one hundred independent domains that each catalyse one step in the overall process, like a step in an assembly line.

One example of mutation is

wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is ...

piglets. They are camouflage colored and show a characteristic pattern of dark and light longitudinal stripes. However, mutations in ''

melanocortin 1 receptor

The melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), also known as melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor (MSHR), melanin-activating peptide receptor, or melanotropin receptor, is a G protein–coupled receptor that binds to a class of pituitary peptide hormones ...

'' (''MC1R'') disrupt the pattern. The majority of pig breeds carry ''MC1R'' mutations disrupting wild-type color and different mutations causing dominant black color of the pigs.

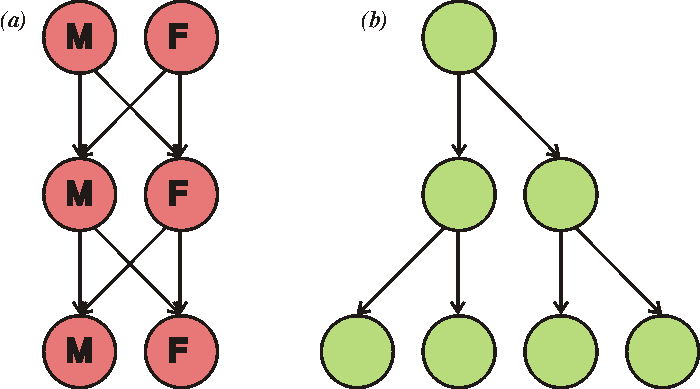

Sex and recombination

In

asexual organisms, genes are inherited together, or ''linked'', as they cannot mix with genes of other organisms during reproduction. In contrast, the offspring of

sex

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones ( ova, of ...

ual organisms contain random mixtures of their parents' chromosomes that are produced through independent assortment. In a related process called

homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may be ...

, sexual organisms exchange DNA between two matching chromosomes. Recombination and reassortment do not alter allele frequencies, but instead change which alleles are associated with each other, producing offspring with new combinations of alleles.

Sex usually increases genetic variation and may increase the rate of evolution.

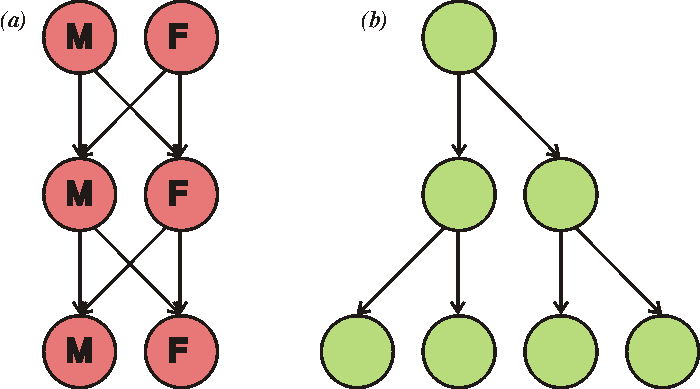

The two-fold cost of sex was first described by

John Maynard Smith

John Maynard Smith (6 January 1920 – 19 April 2004) was a British theoretical and mathematical evolutionary biologist and geneticist. Originally an aeronautical engineer during the Second World War, he took a second degree in genetics ...

.

The first cost is that in sexually dimorphic species only one of the two sexes can bear young. This cost does not apply to hermaphroditic species, like most plants and many

invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s. The second cost is that any individual who reproduces sexually can only pass on 50% of its genes to any individual offspring, with even less passed on as each new generation passes.

Yet sexual reproduction is the more common means of reproduction among eukaryotes and multicellular organisms. The

Red Queen hypothesis

The Red Queen hypothesis is a hypothesis in evolutionary biology proposed in 1973, that species must constantly adapt, evolve, and proliferate in order to survive while pitted against ever-evolving opposing species. The hypothesis was intended ...

has been used to explain the significance of sexual reproduction as a means to enable continual evolution and adaptation in response to

coevolution

In biology, coevolution occurs when two or more species reciprocally affect each other's evolution through the process of natural selection. The term sometimes is used for two traits in the same species affecting each other's evolution, as well ...

with other species in an ever-changing environment.

Another hypothesis is that sexual reproduction is primarily an adaptation for promoting accurate recombinational repair of damage in germline DNA, and that increased diversity is a byproduct of this process that may sometimes be adaptively beneficial.

Gene flow

Gene flow is the exchange of genes between populations and between species.

It can therefore be a source of variation that is new to a population or to a species. Gene flow can be caused by the movement of individuals between separate populations of organisms, as might be caused by the movement of mice between inland and coastal populations, or the movement of

pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by seed plants. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm cells). Pollen grains have a hard coat made of sporopollenin that protects the gametop ...

between heavy-metal-tolerant and heavy-metal-sensitive populations of grasses.

Gene transfer between species includes the formation of

hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two diff ...

organisms and

horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

. Horizontal gene transfer is the transfer of genetic material from one organism to another organism that is not its offspring; this is most common among

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

. In medicine, this contributes to the spread of

antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistanc ...

, as when one bacteria acquires resistance genes it can rapidly transfer them to other species.

Horizontal transfer of genes from bacteria to eukaryotes such as the yeast ''

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungus microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have been o ...

'' and the adzuki bean weevil ''

Callosobruchus chinensis'' has occurred. An example of larger-scale transfers are the eukaryotic

bdelloid rotifers, which have received a range of genes from bacteria,

fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

and plants.

Virus

A virus is a wikt:submicroscopic, submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and ...

es can also carry DNA between organisms, allowing transfer of genes even across

biological domains.

Large-scale gene transfer has also occurred between the ancestors of

eukaryotic cells

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

and bacteria, during the acquisition of

chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

s and

mitochondria. It is possible that eukaryotes themselves originated from horizontal gene transfers between bacteria and

archaea.

Evolutionary processes

From a

neo-Darwinian perspective, evolution occurs when there are changes in the frequencies of alleles within a population of interbreeding organisms,

for example, the allele for black colour in a population of moths becoming more common. Mechanisms that can lead to changes in allele frequencies include natural selection, genetic drift, gene flow and mutation bias.

Natural selection

Evolution by natural selection is the process by which traits that enhance survival and reproduction become more common in successive generations of a population. It embodies three principles:

* Variation exists within populations of organisms with respect to morphology, physiology and behaviour (phenotypic variation).

* Different traits confer different rates of survival and reproduction (differential fitness).

* These traits can be passed from generation to generation (heritability of fitness).

More offspring are produced than can possibly survive, and these conditions produce competition between organisms for survival and reproduction. Consequently, organisms with traits that give them an advantage over their competitors are more likely to pass on their traits to the next generation than those with traits that do not confer an advantage.

This

teleonomy

Teleonomy is the quality of apparent purposefulness and of goal-directedness of structures and functions in living organisms brought about by natural processes like natural selection. The term derives from the Greek "τελεονομία", compoun ...

is the quality whereby the process of natural selection creates and preserves traits that are

seemingly fitted for the

functional

Functional may refer to:

* Movements in architecture:

** Functionalism (architecture)

** Form follows function

* Functional group, combination of atoms within molecules

* Medical conditions without currently visible organic basis:

** Functional s ...

roles they perform. Consequences of selection include

nonrandom mating and

genetic hitchhiking

Genetic may refer to:

*Genetics, in biology, the science of genes, heredity, and the variation of organisms

**Genetic, used as an adjective, refers to genes

***Genetic disorder, any disorder caused by a genetic mutation, whether inherited or de nov ...

.

The central concept of natural selection is the

evolutionary fitness

Fitness (often denoted w or ω in population genetics models) is the quantitative representation of individual reproductive success. It is also equal to the average contribution to the gene pool of the next generation, made by the same individual ...

of an organism.

Fitness is measured by an organism's ability to survive and reproduce, which determines the size of its genetic contribution to the next generation.

However, fitness is not the same as the total number of offspring: instead fitness is indicated by the proportion of subsequent generations that carry an organism's genes.

For example, if an organism could survive well and reproduce rapidly, but its offspring were all too small and weak to survive, this organism would make little genetic contribution to future generations and would thus have low fitness.

If an allele increases fitness more than the other alleles of that gene, then with each generation this allele will become more common within the population. These traits are said to be "selected ''for''." Examples of traits that can increase fitness are enhanced survival and increased

fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the natural capability to pr ...

. Conversely, the lower fitness caused by having a less beneficial or deleterious allele results in this allele becoming rarer—they are "selected ''against''."

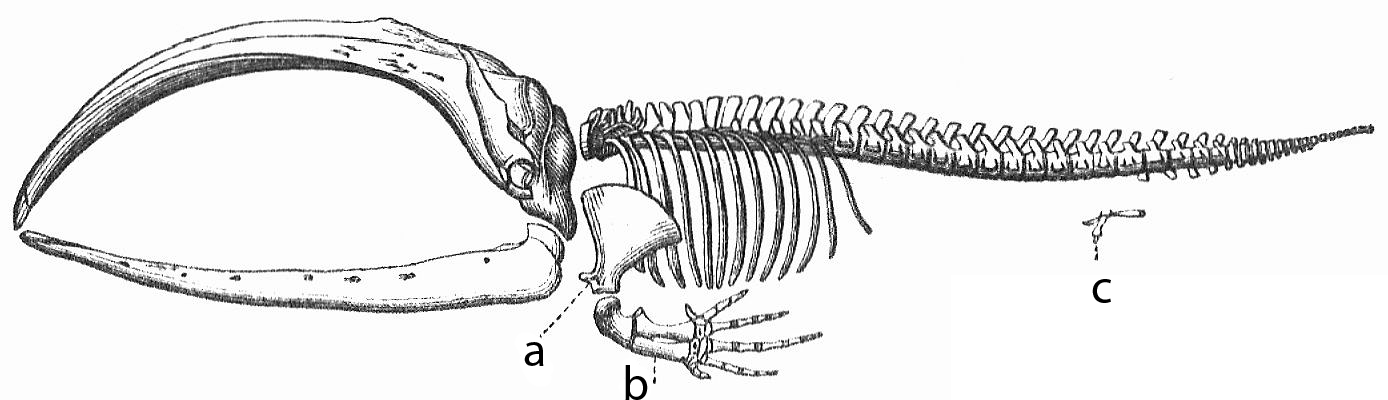

Importantly, the fitness of an allele is not a fixed characteristic; if the environment changes, previously neutral or harmful traits may become beneficial and previously beneficial traits become harmful.

However, even if the direction of selection does reverse in this way, traits that were lost in the past may not re-evolve in an identical form (see

Dollo's law

Dollo's law of irreversibility (also known as Dollo's law and Dollo's principle), proposed in 1893 by Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo states that, "an organism never returns exactly to a former state, even if it finds itself placed in condit ...

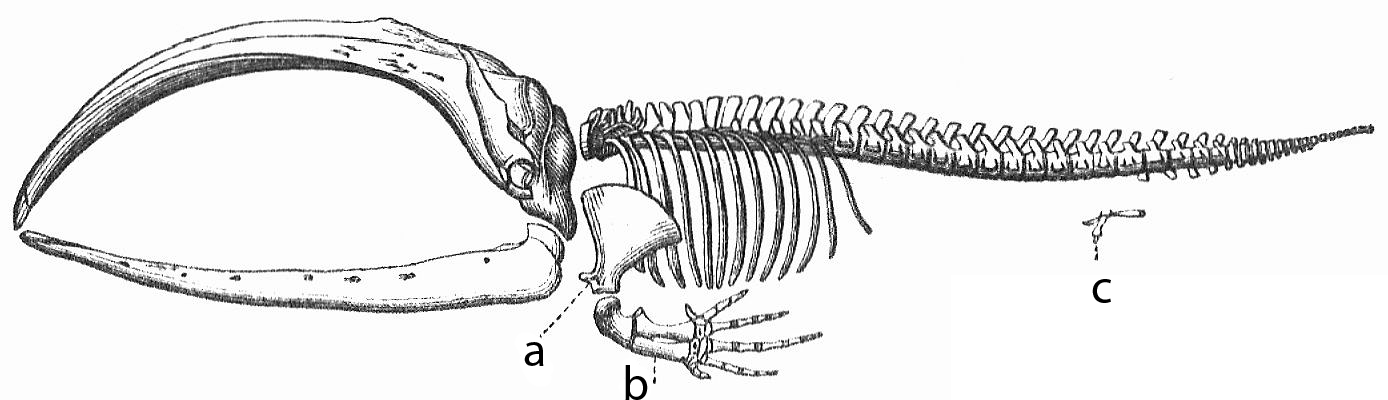

). However, a re-activation of dormant genes, as long as they have not been eliminated from the genome and were only suppressed perhaps for hundreds of generations, can lead to the re-occurrence of traits thought to be lost like hindlegs in

dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (t ...

s, teeth in

chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domestication, domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey junglefowl, grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster ...

s, wings in wingless stick

insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s, tails and additional nipples in humans etc. "Throwbacks" such as these are known as

atavism

In biology, an atavism is a modification of a biological structure whereby an ancestral genetic trait reappears after having been lost through evolutionary change in previous generations. Atavisms can occur in several ways; one of which is when ...

s.

Natural selection within a population for a trait that can vary across a range of values, such as height, can be categorised into three different types. The first is

directional selection

In population genetics, directional selection, is a mode of negative natural selection in which an extreme phenotype is favored over other phenotypes, causing the allele frequency to shift over time in the direction of that phenotype. Under ...

, which is a shift in the average value of a trait over time—for example, organisms slowly getting taller. Secondly,

disruptive selection

Disruptive selection, also called diversifying selection, describes changes in population genetics in which extreme values for a trait are favored over intermediate values. In this case, the variance of the trait increases and the population ...

is selection for extreme trait values and often results in

two different values becoming most common, with selection against the average value. This would be when either short or tall organisms had an advantage, but not those of medium height. Finally, in

stabilising selection there is selection against extreme trait values on both ends, which causes a decrease in

variance

In probability theory and statistics, variance is the expectation of the squared deviation of a random variable from its population mean or sample mean. Variance is a measure of dispersion, meaning it is a measure of how far a set of number ...

around the average value and less diversity.

This would, for example, cause organisms to eventually have a similar height.

Natural selection most generally makes nature the measure against which individuals and individual traits, are more or less likely to survive. "Nature" in this sense refers to an

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

, that is, a system in which organisms interact with every other element,

physical

Physical may refer to:

*Physical examination

In a physical examination, medical examination, or clinical examination, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a medical condition. It generally cons ...

as well as

biological

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

, in their local environment.

Eugene Odum

Eugene Pleasants Odum (September 17, 1913 – August 10, 2002) was an American biologist at the University of Georgia known for his pioneering work on ecosystem ecology. He and his brother Howard T. Odum wrote the popular ecology textbook, ''Fund ...

, a founder of

ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

, defined an ecosystem as: "Any unit that includes all of the organisms...in a given area interacting with the physical environment so that a flow of energy leads to clearly defined trophic structure, biotic diversity, and material cycles (i.e., exchange of materials between living and nonliving parts) within the system...."

Each population within an ecosystem occupies a distinct

niche, or position, with distinct relationships to other parts of the system. These relationships involve the life history of the organism, its position in the

food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), d ...

and its geographic range. This broad understanding of nature enables scientists to delineate specific forces which, together, comprise natural selection.

Natural selection can act at

different levels of organisation, such as genes, cells, individual organisms, groups of organisms and species.

Selection can act at multiple levels simultaneously. An example of selection occurring below the level of the individual organism are genes called

transposons

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Trans ...

, which can replicate and spread throughout a genome. Selection at a level above the individual, such as

group selection

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Early authors such as V. C. Wynne-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz argued that the behav ...

, may allow the evolution of cooperation.

Genetic hitchhiking

Recombination allows alleles on the same strand of DNA to become separated. However, the rate of recombination is low (approximately two events per chromosome per generation). As a result, genes close together on a chromosome may not always be shuffled away from each other and genes that are close together tend to be inherited together, a phenomenon known as

linkage

Linkage may refer to:

* ''Linkage'' (album), by J-pop singer Mami Kawada, released in 2010

*Linkage (graph theory), the maximum min-degree of any of its subgraphs

*Linkage (horse), an American Thoroughbred racehorse

* Linkage (hierarchical cluster ...

. This tendency is measured by finding how often two alleles occur together on a single chromosome compared to

expectations, which is called their

linkage disequilibrium

In population genetics, linkage disequilibrium (LD) is the non-random association of alleles at different loci in a given population. Loci are said to be in linkage disequilibrium when the frequency of association of their different alleles is h ...

. A set of alleles that is usually inherited in a group is called a

haplotype

A haplotype ( haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material ( DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA or ...

. This can be important when one allele in a particular haplotype is strongly beneficial: natural selection can drive a

selective sweep

In genetics, a selective sweep is the process through which a new beneficial mutation that increases its frequency and becomes fixed (i.e., reaches a frequency of 1) in the population leads to the reduction or elimination of genetic variation amon ...

that will also cause the other alleles in the haplotype to become more common in the population; this effect is called genetic hitchhiking or genetic draft. Genetic draft caused by the fact that some neutral genes are genetically linked to others that are under selection can be partially captured by an appropriate effective population size.

Sexual selection

A special case of natural selection is sexual selection, which is selection for any trait that increases mating success by increasing the attractiveness of an organism to potential mates. Traits that evolved through sexual selection are particularly prominent among males of several animal species. Although sexually favoured, traits such as cumbersome antlers, mating calls, large body size and bright colours often attract predation, which compromises the survival of individual males.

This survival disadvantage is balanced by higher reproductive success in males that show these

hard-to-fake, sexually selected traits.

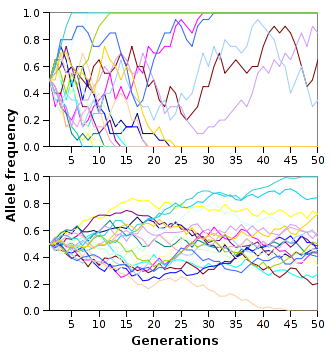

Genetic drift

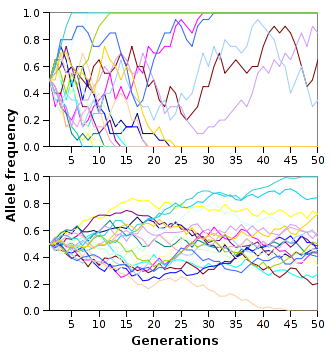

Genetic drift is the random fluctuation of

allele frequencies

Allele frequency, or gene frequency, is the relative frequency of an allele (variant of a gene) at a particular locus in a population, expressed as a fraction or percentage. Specifically, it is the fraction of all chromosomes in the population tha ...

within a population from one generation to the next.

When selective forces are absent or relatively weak, allele frequencies are equally likely to ''drift'' upward or downward in each successive generation because the alleles are subject to

sampling error

In statistics, sampling errors are incurred when the statistical characteristics of a population are estimated from a subset, or sample, of that population. Since the sample does not include all members of the population, statistics of the sample ...

.

This drift halts when an allele eventually becomes fixed, either by disappearing from the population or by replacing the other alleles entirely. Genetic drift may therefore eliminate some alleles from a population due to chance alone. Even in the absence of selective forces, genetic drift can cause two separate populations that begin with the same genetic structure to drift apart into two divergent populations with different sets of alleles.

According to the now largely abandoned

neutral theory of molecular evolution

The neutral theory of molecular evolution holds that most evolutionary changes occur at the molecular level, and most of the variation within and between species are due to random genetic drift of mutant alleles that are selectively neutral. Th ...

most evolutionary changes are the result of the fixation of

neutral mutation Neutral mutations are changes in DNA sequence that are neither beneficial nor detrimental to the ability of an organism to survive and reproduce. In population genetics, mutations in which natural selection does not affect the spread of the mutatio ...

s by genetic drift.

In this model, most genetic changes in a population are thus the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift. This form of the neutral theory is now largely abandoned since it does not seem to fit the genetic variation seen in nature. A better-supported version of this model is the

nearly neutral theory, according to which a mutation that would be effectively neutral in a small population is not necessarily neutral in a large population.

Other theories propose that genetic drift is dwarfed by other

stochastic

Stochastic (, ) refers to the property of being well described by a random probability distribution. Although stochasticity and randomness are distinct in that the former refers to a modeling approach and the latter refers to phenomena themselve ...

forces in evolution, such as genetic hitchhiking, also known as genetic draft.

Another concept is

constructive neutral evolution Constructive neutral evolution (CNE) is a theory that seeks to explain how complex systems can evolve through neutral transitions and spread through a population by chance fixation (genetic drift). Constructive neutral evolution is a competitor for ...

(CNE), which explains that complex systems can emerge and spread into a population through neutral transitions due to the principles of excess capacity, presuppression, and ratcheting, and it has been applied in areas ranging from the origins of the

spliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs ( snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to sp ...

to the complex interdependence of

microbial communities.

The time it takes a neutral allele to become fixed by genetic drift depends on population size; fixation is more rapid in smaller populations. The number of individuals in a population is not critical, but instead a measure known as the effective population size.

The effective population is usually smaller than the total population since it takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding and the stage of the lifecycle in which the population is the smallest.

The effective population size may not be the same for every gene in the same population.

It is usually difficult to measure the relative importance of selection and neutral processes, including drift. The comparative importance of adaptive and non-adaptive forces in driving evolutionary change is an area of

current research

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (s ...

.

Gene flow

Gene flow involves the exchange of genes between populations and between species.

The presence or absence of gene flow fundamentally changes the course of evolution. Due to the complexity of organisms, any two completely isolated populations will eventually evolve genetic incompatibilities through neutral processes, as in the

Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller model, even if both populations remain essentially identical in terms of their adaptation to the environment.

If genetic differentiation between populations develops, gene flow between populations can introduce traits or alleles which are disadvantageous in the local population and this may lead to organisms within these populations evolving mechanisms that prevent mating with genetically distant populations, eventually resulting in the appearance of new species. Thus, exchange of genetic information between individuals is fundamentally important for the development of the

''Biological Species Concept''.

During the development of the modern synthesis, Sewall Wright developed his

shifting balance theory

The shifting balance theory is a theory of evolution proposed in 1932 by Sewall Wright, suggesting that adaptive evolution may proceed most quickly when a population divides into subpopulations with restricted gene flow. The name of the theory i ...

, which regarded gene flow between partially isolated populations as an important aspect of adaptive evolution. However, recently there has been substantial criticism of the importance of the shifting balance theory.

Mutation bias

Mutation bias is usually conceived as a difference in expected rates for two different kinds of mutation, e.g., transition-transversion bias, GC-AT bias, deletion-insertion bias. This is related to the idea of

developmental bias. Haldane

and Fisher

argued that, because mutation is a weak pressure easily overcome by selection, tendencies of mutation would be ineffectual except under conditions of neutral evolution or extraordinarily high mutation rates. This opposing-pressures argument was long used to dismiss the possibility of internal tendencies in evolution,

until the molecular era prompted renewed interest in neutral evolution.

Noboru Sueoka

and

Ernst Freese proposed that systematic biases in mutation might be responsible for systematic differences in genomic GC composition between species. The identification of a GC-biased ''E. coli'' mutator strain in 1967,

along with the proposal of the

neutral theory, established the plausibility of mutational explanations for molecular patterns, which are now common in the molecular evolution literature.

For instance, mutation biases are frequently invoked in models of codon usage.

Such models also include effects of selection, following the mutation-selection-drift model,

which allows both for mutation biases and differential selection based on effects on translation. Hypotheses of mutation bias have played an important role in the development of thinking about the evolution of genome composition, including isochores.

Different insertion vs. deletion biases in different

taxa

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

can lead to the evolution of different genome sizes. The hypothesis of Lynch regarding genome size relies on mutational biases toward increase or decrease in genome size.

However, mutational hypotheses for the evolution of composition suffered a reduction in scope when it was discovered that (1) GC-biased gene conversion makes an important contribution to composition in diploid organisms such as mammals

and (2) bacterial genomes frequently have AT-biased mutation.

Contemporary thinking about the role of mutation biases reflects a different theory from that of Haldane and Fisher. More recent work

showed that the original "pressures" theory assumes that evolution is based on standing variation: when evolution depends on the introduction of new alleles, mutational and developmental biases in the introduction can impose biases on evolution ''without requiring neutral evolution or high mutation rates''.

Several studies report that the mutations implicated in adaptation reflect common mutation biases

though others dispute this interpretation.

Applications

Concepts and models used in evolutionary biology, such as natural selection, have many applications.

Artificial selection is the intentional selection of traits in a population of organisms. This has been used for thousands of years in the

domestication

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a significant degree of control over the reproduction and care of another group of organisms to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that group. A ...

of plants and animals. More recently, such selection has become a vital part of

genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including ...

, with

selectable marker A selectable marker is a gene introduced into a cell, especially a bacterium or to cells in culture, that confers a trait suitable for artificial selection. They are a type of reporter gene used in laboratory microbiology, molecular biology, and g ...

s such as antibiotic resistance genes being used to manipulate DNA. Proteins with valuable properties have evolved by repeated rounds of mutation and selection (for example modified enzymes and new

antibodies) in a process called

directed evolution

Directed evolution (DE) is a method used in protein engineering that mimics the process of natural selection to steer proteins or nucleic acids toward a user-defined goal. It consists of subjecting a gene to iterative rounds of mutagenesis (cre ...

.

Understanding the changes that have occurred during an organism's evolution can reveal the genes needed to construct parts of the body, genes which may be involved in human

genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosomal abnormality. Although polygenic disorde ...

s. For example, the

Mexican tetra is an

albino

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

cavefish that lost its eyesight during evolution. Breeding together different populations of this blind fish produced some offspring with functional eyes, since different mutations had occurred in the isolated populations that had evolved in different caves. This helped identify genes required for vision and pigmentation.

Evolutionary theory has many

applications in medicine. Many human diseases are not static phenomena, but capable of evolution. Viruses, bacteria, fungi and

cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bl ...

s evolve to be resistant to host immune defences, as well as to

pharmaceutical drug

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and ...

s. These same problems occur in agriculture with pesticide and

herbicide resistance. It is possible that we are facing the end of the effective life of most of available antibiotics and predicting the evolution and evolvability of our pathogens and devising strategies to slow or circumvent it is requiring deeper knowledge of the complex forces driving evolution at the molecular level.

In

computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to practical disciplines (includin ...

, simulations of evolution using

evolutionary algorithm

In computational intelligence (CI), an evolutionary algorithm (EA) is a subset of evolutionary computation, a generic population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithm. An EA uses mechanisms inspired by biological evolution, such as rep ...

s and

artificial life

Artificial life (often abbreviated ALife or A-Life) is a field of study wherein researchers examine systems related to natural life, its processes, and its evolution, through the use of simulations with computer models, robotics, and biochemist ...

started in the 1960s and were extended with simulation of artificial selection. Artificial evolution became a widely recognised optimisation method as a result of the work of

Ingo Rechenberg

Ingo Rechenberg (November 20, 1934 - September 25, 2021) was a German researcher and professor in the field of bionics. Rechenberg was a pioneer of the fields of evolutionary computation and artificial evolution. In the 1960s and 1970s he invent ...

in the 1960s. He used

evolution strategies

In computer science, an evolution strategy (ES) is an optimization technique based on ideas of evolution. It belongs to the general class of evolutionary computation or artificial evolution methodologies.

History

The 'evolution strategy' optimizat ...

to solve complex engineering problems.

Genetic algorithm

In computer science and operations research, a genetic algorithm (GA) is a metaheuristic inspired by the process of natural selection that belongs to the larger class of evolutionary algorithms (EA). Genetic algorithms are commonly used to gen ...

s in particular became popular through the writing of

John Henry Holland

John Henry Holland (February 2, 1929 – August 9, 2015) was an American scientist and Professor of psychology and Professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He was a pioneer in what became ...

. Practical applications also include

automatic evolution of computer programmes. Evolutionary algorithms are now used to solve multi-dimensional problems more efficiently than software produced by human designers and also to optimise the design of systems.

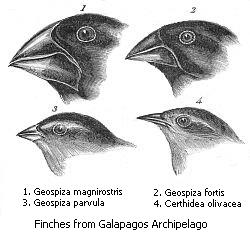

Natural outcomes

Evolution influences every aspect of the form and behaviour of organisms. Most prominent are the specific behavioural and physical adaptations that are the outcome of natural selection. These adaptations increase fitness by aiding activities such as finding food, avoiding

predators

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

or attracting mates. Organisms can also respond to selection by

cooperating with each other, usually by aiding their relatives or engaging in mutually beneficial

symbiosis. In the longer term, evolution produces new species through splitting ancestral populations of organisms into new groups that cannot or will not interbreed. These outcomes of evolution are distinguished based on time scale as

macroevolution

Macroevolution usually means the evolution of large-scale structures and traits that go significantly beyond the intraspecific variation found in microevolution (including speciation). In other words, macroevolution is the evolution of taxa abov ...

versus microevolution. Macroevolution refers to evolution that occurs at or above the level of species, in particular speciation and extinction; whereas microevolution refers to smaller evolutionary changes within a species or population, in particular shifts in allele frequency and adaptation.

Macroevolution the outcome of long periods of microevolution. Thus, the distinction between micro- and macroevolution is not a fundamental one—the difference is simply the time involved. However, in macroevolution, the traits of the entire species may be important. For instance, a large amount of variation among individuals allows a species to rapidly adapt to new

habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s, lessening the chance of it going extinct, while a wide geographic range increases the chance of speciation, by making it more likely that part of the population will become isolated. In this sense, microevolution and macroevolution might involve selection at different levels—with microevolution acting on genes and organisms, versus macroevolutionary processes such as

species selection

A unit of selection is a biological entity within the hierarchy of biological organization (for example, an entity such as: a self-replicating molecule, a gene, a cell, an organism, a group, or a species) that is subject to natural selection. ...

acting on entire species and affecting their rates of speciation and extinction.

A common misconception is that evolution has goals, long-term plans, or an innate tendency for "progress", as expressed in beliefs such as orthogenesis and evolutionism; realistically however, evolution has no long-term goal and does not necessarily produce greater complexity.

Although

complex species have evolved, they occur as a side effect of the overall number of organisms increasing and simple forms of life still remain more common in the biosphere.

For example, the overwhelming majority of species are microscopic

prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

s, which form about half the world's

biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms biom ...

despite their small size, and constitute the vast majority of Earth's biodiversity.

Simple organisms have therefore been the dominant form of life on Earth throughout its history and continue to be the main form of life up to the present day, with complex life only appearing more diverse because it is

more noticeable. Indeed, the evolution of microorganisms is particularly important to evolutionary research, since their rapid reproduction allows the study of

experimental evolution and the observation of evolution and adaptation in real time.

Adaptation

Adaptation is the process that makes organisms better suited to their habitat. Also, the term adaptation may refer to a trait that is important for an organism's survival. For example, the adaptation of

horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million ...

s' teeth to the grinding of grass. By using the term ''adaptation'' for the evolutionary process and ''adaptive trait'' for the product (the bodily part or function), the two senses of the word may be distinguished. Adaptations are produced by natural selection. The following definitions are due to Theodosius Dobzhansky:

# ''Adaptation'' is the evolutionary process whereby an organism becomes better able to live in its habitat or habitats.

# ''Adaptedness'' is the state of being adapted: the degree to which an organism is able to live and reproduce in a given set of habitats.

# An ''adaptive trait'' is an aspect of the developmental pattern of the organism which enables or enhances the probability of that organism surviving and reproducing.

Adaptation may cause either the gain of a new feature, or the loss of an ancestral feature. An example that shows both types of change is bacterial adaptation to antibiotic selection, with genetic changes causing antibiotic resistance by both modifying the target of the drug, or increasing the activity of transporters that pump the drug out of the cell. Other striking examples are the bacteria ''

Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Esc ...

'' evolving the ability to use

citric acid

Citric acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula HOC(CO2H)(CH2CO2H)2. It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in t ...

as a nutrient in a

long-term laboratory experiment, ''

Flavobacterium

''Flavobacterium'' is a genus of Gram-negative, nonmotile and motile, rod-shaped bacteria that consists of 130 recognized species. Flavobacteria are found in soil and fresh water in a variety of environments. Several species are known to cause ...

'' evolving a novel enzyme that allows these bacteria to grow on the by-products of

nylon

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers composed of polyamides ( repeating units linked by amide links).The polyamides may be aliphatic or semi-aromatic.

Nylon is a silk-like thermoplastic, generally made from pet ...

manufacturing, and the soil bacterium ''

Sphingobium'' evolving an entirely new

metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell. The reactants, products, and intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are modified by a sequence of chemical ...

that degrades the synthetic

pesticide pentachlorophenol

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) is an organochlorine compound used as a pesticide and a disinfectant. First produced in the 1930s, it is marketed under many trade names. It can be found as pure PCP, or as the sodium salt of PCP, the latter of which dis ...

. An interesting but still controversial idea is that some adaptations might increase the ability of organisms to generate genetic diversity and adapt by natural selection (increasing organisms' evolvability).

Adaptation occurs through the gradual modification of existing structures. Consequently, structures with similar internal organisation may have different functions in related organisms. This is the result of a single ancestral structure being adapted to function in different ways. The bones within

bat wings, for example, are very similar to those in