Eurofederalist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States of Europe (USE), the European State, the European Federation and Federal Europe, is the hypothetical scenario of the

– The Guardian, 7 December 2017 He proposed that this constitution should be written by "a convention that includes civil society and the people" and that any state that declined to accept this proposed constitution should have to leave the bloc. The Guardian's view was that his proposal was "likely to be met with some resistance from Angela Merkel and other EU leaders". On that day he also stated that he would like to see a "United States of Europe" by 2025.SPD's Martin Schulz wants United States of Europe by 2025

– Politico, 7 December 2017

In 1992, Dutch businessman

In 1992, Dutch businessman

According to Eurobarometer (2013), 69% of citizens of the EU were in favour of

According to Eurobarometer (2013), 69% of citizens of the EU were in favour of

Political speeches

by

''Towards a United States of Europe''

by

European integration

European integration is the process of industrial, economic integration, economic, political, legal, social integration, social, and cultural Regional integration, integration of states wholly or partially in Europe or nearby. European integrat ...

leading to formation of a sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

superstate

A superstate is defined as "a large and powerful state formed when several smaller countries unite", or "A large and powerful state formed from a federation or union of nations", or "a hybrid form of polity that combines features of

ancient emp ...

(similar to the United States of America), organised as a federation of the member countries of the European Union (EU), as contemplated by political scientists, politicians, geographers, historians, futurologists and fiction writers. At present, while the EU is not a federation, various academic observers regard it as having some of the characteristics of a federal system. in

History

Various versions of the concept have developed over the centuries, many of which are mutually incompatible (inclusion or exclusion of the United Kingdom, secular or religious union, etc.). Such proposals include those from Bohemian King George of Poděbrady in 1464; Duc de Sully of France in the seventeenth century; and the plan of William Penn, theQuaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

founder of Pennsylvania, for the establishment of a "European Dyet, Parliament or Estates". George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

also allegedly voiced support for a "United States of Europe", although the authenticity of this statement has been questioned.

19th century

Felix Markham

Felix Maurice Hippisley Markham (1908 in Brighton – 1992) was a British historian, known for his biography of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Markham studied at the University of Oxford and taught there for 40 years. He was Fellow and History Tutor at ...

notes how during a conversation on St. Helena, Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

remarked: "Europe thus divided into nationalities freely formed and free internally, peace between States would have become easier: the United States of Europe would become a possibility". "United States of Europe" was also the name of the concept presented by Wojciech Jastrzębowski in ''About eternal peace between the nations'', published 31 May 1831. The project consisted of 77 articles. The envisioned United States of Europe was to be an international organisation rather than a superstate. Giuseppe Mazzini, an early advocate of a "United States of Europe" regarded European unification as a logical continuation of the unification of Italy. Mazzini created the Young Europe movement.

The term "United States of Europe" (french: États-Unis d'Europe) was used by Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, including during a speech at the International Peace Congress held in Paris in 1849. Hugo favoured the creation of "a supreme, sovereign senate, which will be to Europe what parliament is to England" and said: "A day will come when all nations on our continent will form a European brotherhood ... A day will come when we shall see ... the United States of America and the United States of Europe face to face, reaching out for each other across the seas". During his exile from France, Hugo planted a tree in the grounds of his residence on the Island of Guernsey

Guernsey (; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; french: Guernesey) is an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy that is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency.

It is the second largest of the Channel Islands ...

and was noted in saying that when this tree matured the United States of Europe would have come into being. This tree to this day is still growing in the gardens of Maison de Hauteville, St. Peter Port, Guernsey.

In 1867, Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

and John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

joined Victor Hugo at the first congress of the League of Peace and Freedom

The Ligue internationale de la paix (League of Peace and Freedom) was created after a public opinion campaign against a war between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia over Luxembourg. The Luxembourg crisis was peacefully resolv ...

in Geneva. Here the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin stated: "That in order to achieve the triumph of liberty, justice and peace in the international relations of Europe, and to render civil war impossible among the various peoples who make up the European family, only a single course lies open: to constitute the United States of Europe". The French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

also called for a United States of Europe on 1 March 1871.

Early 20th century

Before the communist revolution in Russia, Leon Trotsky foresaw a "Federated Republic of Europe — the United States of Europe", created by theproletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

. Following the First World War, some thinkers and visionaries again began to float the idea of a politically unified Europe. A Pan-European movement gained some momentum from the 1920s with the creation of the Paneuropean Union, based on Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi's 1923 manifesto ''Paneuropa

The International Paneuropean Union, also referred to as the Pan-European Movement and the Pan-Europa Movement, is the oldest European unification movement.

It began with the publishing of Count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi's manifesto ''P ...

'', which presented the idea of a unified European State. This movement, led by Coudenhove-Kalergi and subsequently by Otto von Habsburg, is the oldest European unification movement.In 1923, the Austrian Count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi founded the Pan-Europa Movement and hosted the First Paneuropean Congress, held in Vienna in 1926. The aim was for a Europe based on the principles of liberalism, Christianity and social responsibility.

His ideas influenced Aristide Briand, French Prime Minister, who gave on 8 September 1929 a speech before the Assembly of the League of Nations in which he proposed the idea of a federation of European nations based on solidarity and in the pursuit of economic prosperity and political and social co-operation. At the League's request, Briand presented in 1930 his "Memorandum on the Organization of a Regime of European Federal Union" for the Government of France. In 1931, French politician Édouard Herriot and British civil servant Arthur Salter both penned books titled ''The United States of Europe''.

After the First World War, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

had seen continental Europe as a source of threats and sought to avoid the United Kingdom's involvement in European conflicts. On 15 February 1930, Churchill commented in the American journal '' The Saturday Evening Post'' that a "European Union" was possible between continental states, but without the United Kingdom's involvement:

During the 1930s, Churchill was influenced by and became an advocate of the ideas of Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi and his Paneuropean Union, though Churchill did not advocate the United Kingdom's membership of such a union. (Churchill revisited the idea in 1946).

During the World War II victories of Nazi Germany in 1940, Wilhelm II stated that "the hand of God is creating a new world & working miracles. ... We are becoming the United States of Europe under German leadership, a united European Continent".

In 1941, the Italian anti-fascists Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi Ernesto Rossi may refer to:

* Ernesto Rossi (actor) (1827–1896), Italian actor

* Ernesto Rossi (politician) (1897–1967), Italian politician and anti-fascist activist

* Ernesto Rossi (gangster) (1903–1931), Italian-American gangster

{{hndis, ...

finished writing the Ventotene Manifesto, encouraging a federation of European states.

The European Confederation European Confederation may refer to:

* European Confederation (1943), a proposal by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in March 1943

* European Confederation (1989), a proposal by French President François Mitterrand in December 19 ...

(german: Europäischer Staatenbund) was a proposed political institution of European unity, which was to be part of a wider restructuring (). Proposed by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

in March 1943, the concept was rejected by Reichsführer Adolf Hitler.

Post World War II

Churchill used the term "United States of Europe" in a speech delivered on 19 September 1946 at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. In this speech given after the end of the Second World War, Churchill concluded: While Churchill advocated a united Europe, he saw Britain and its Commonwealth, along with the United States of America, and Soviet Russia as "the friends and sponsors of the new Europe", separate to a United States of Europe led by France and Germany. As early as 21 October 1942, in a minute to his Foreign Secretary, Prime Minister Churchill had written, "I look forward to a United States of Europe in which the barriers between the nations will be greatly minimised and unrestricted travel will be possible". Churchill's was a more cautious approach ("the unionist position") to European integration than was the continental approach that was known as "the federalist position". The Federalists advocated full integration with a constitution, while the Unionist United Europe Movement advocated a consultative body; the Federalists prevailed at the Congress of Europe. The primary accomplishment of the Congress of Europe was the European Court of Human Rights, which predates the European Union. The Union Movement was a British party founded by Oswald Mosley after the dissolution of hisBritish Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

. Mosley first presented his idea of " Europe a Nation" in his book ''The Alternative'' in 1947.

He argued that the traditional vision of nationalism that had been followed by the various shades of pre-war fascism had been too narrow in scope and that the post-war era required a new paradigm in which Europe would come together as a single state. In October 1948 when Mosley called for elections to a European Assembly as the first step towards his vision.Harris, Geoffrey, ''The Dark Side of Europe: The Extreme Right Today'', Edinburgh University Press, 1994, p. 31 '' Nation Europa'' was a German magazine inspired by Mosley's ideas, founded in 1951 by former SS commander Arthur Ehrhardt

Arthur Ehrhardt (21 March 1896 – 16 May 1971) was a Waffen-SS commander who served as a Nazi security warfare expert during World War II. After the war, he became a leading figure in the neo-Nazi movement.

Early years

Ehrhardt was born Mengers ...

and Herbert Boehme with the support of Carl-Ehrenfried Carlberg

Carl-Ehrenfried Carlberg (24 February 1889 – 22 January 1962) was a Swedish gymnast who competed in the 1912 Summer Olympics.

Early life and Olympics

Carlberg was born in Stockholm and served in the Royal Guards Regiment Göta of the Swedis ...

.

By the 1950s and 1960s, Europe saw the emergence of two different projects, the European Free Trade Association

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is a regional trade organization and free trade area consisting of four List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Europe, European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerlan ...

and the much more political European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

.

Early 21st century

Individuals such as the former German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer have said (in 2000) that he believes that in the end, the EU, must become a single federation, with its political leader chosen by direct elections among all of its citizens. However, claims that the then-proposed Treaty of Nice aimed to create a "European superstate" were rejected by former United KingdomEuropean Commissioner

A European Commissioner is a member of the 27-member European Commission. Each member within the Commission holds a specific portfolio. The commission is led by the President of the European Commission. In simple terms they are the equivalent ...

Chris Patten

Christopher Francis Patten, Baron Patten of Barnes, (; born 12 May 1944) is a British politician who was the 28th and last Governor of Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997 and Chairman of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1992. He was made a life pe ...

and by many member-state governments. (, the post "President of the European Union

The official title President of the European Union (or President of Europe) does not exist, but there are a number of presidents of European Union institutions, including:

* the President of the European Council (since 1 December 2019, Charle ...

" does not exist, nor are there any plans that it should do so.)

Proposals for closer union

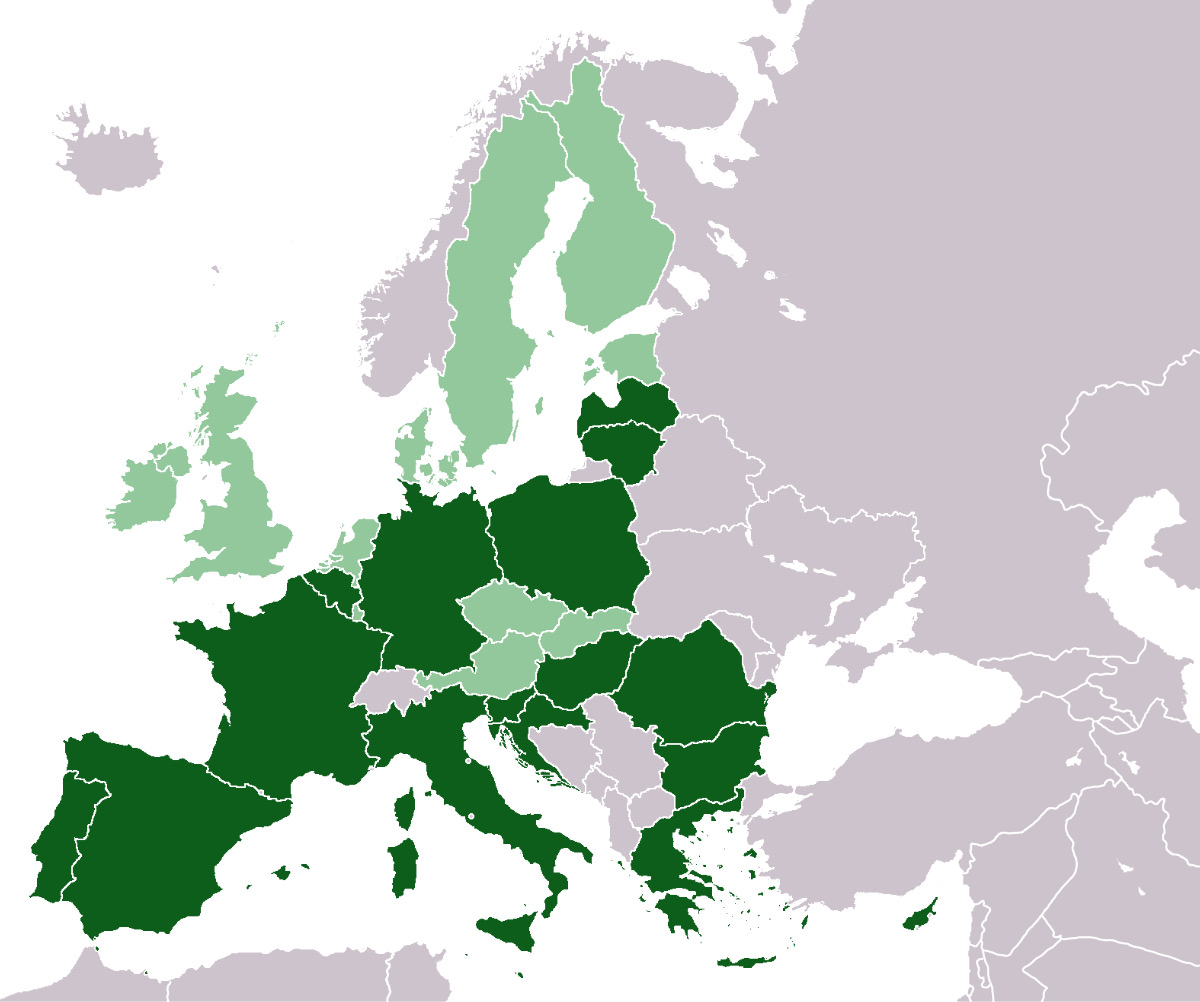

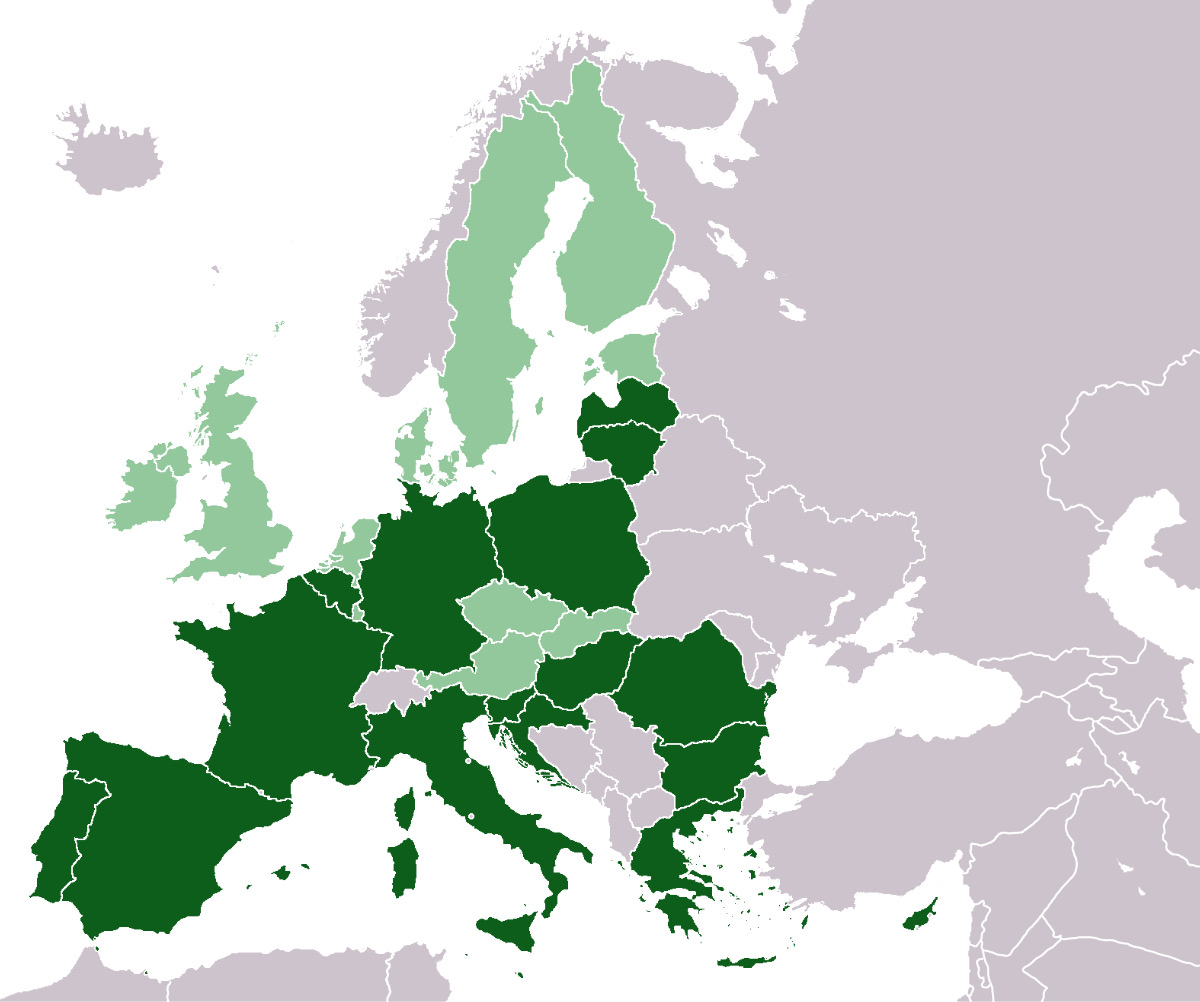

The member states of the European Union do have many common policies within the EU and on behalf of the EU that are sometimes suggestive of a single state. It has a common executive (the European Commission), a single High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy, a common European Security and Defence Policy, a supreme court (European Court of Justice

The European Court of Justice (ECJ, french: Cour de Justice européenne), formally just the Court of Justice, is the supreme court of the European Union in matters of European Union law. As a part of the Court of Justice of the European Un ...

but only in matters of European Union law

European Union law is a system of rules operating within the member states of the European Union (EU). Since the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community following World War II, the EU has developed the aim to "promote peace, its valu ...

) and an intergovernmental research organisation (the EIROforum with members like CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN (; ; ), is an intergovernmental organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, it is based in a northwestern suburb of Gene ...

). The euro is often referred to as the "single European currency", which has been officially adopted by nineteen EU countries while three other member countries of the European Union have linked their currencies to the euro in ERM II

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as ...

. Then non-EU member states of Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City concluded monetary agreements with the EU on the usage of the euro. The non-EU member states of Kosovo and Montenegro adopted the euro unilaterally.

Several pan-European institutions exist separate from the EU. The European Space Agency

, owners =

, headquarters = Paris, Île-de-France, France

, coordinates =

, spaceport = Guiana Space Centre

, seal = File:ESA emblem seal.png

, seal_size = 130px

, image = Views in the Main Control Room (1205 ...

counts almost all EU member states in its membership, but it is independent of the EU and its membership includes nations that are not EU members, notably Switzerland, Norway and as a result of Brexit, the United Kingdom. The European Court of Human Rights (not to be confused with the European Court of Justice) is also independent of the EU. It is an element of the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold European Convention on Human Rights, human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. ...

, which like ESA counts EU members and non-members alike in its membership.

At present, the European Union is a free association of sovereign states (a de facto, but not de jure, confederation) designed to further their shared aims. Other than the vague aim of "ever closer union" in the Solemn Declaration on European Union

The Solemn Declaration on European Union was signed by the then 10 heads of state and government on Sunday 19 June 1983, at the Stuttgart European Council held in Stuttgart.

In November 1981, the German and Italian Governments submitted to the M ...

, the EU (meaning its member governments) has no current policy to form a federal union. However, in the past Jean Monnet

Jean Omer Marie Gabriel Monnet (; 9 November 1888 – 16 March 1979) was a French civil servant, entrepreneur, diplomat, financier, administrator, and political visionary. An influential supporter of European unity, he is considered one of the ...

, a person associated with the EU and its predecessor the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

, did make such proposals. A wide range of other terms are in use to describe the possible future political structure of Europe as a whole and/or the EU. Some of them, such as "United Europe", are used often and in such varied contexts, but they have no definite constitutional status.

In the United States of America, the concept enters serious discussions of whether a unified Europe is feasible and what impact increased European unity would have on the United States of America's relative political and economic power. Glyn Morgan, a Harvard University associate professor of government and social studies, uses it unapologetically in the title of his book ''The Idea of a European Superstate: Public Justification and European Integration.'' While Morgan's text focuses on the security implications of a unified Europe, a number of other recent texts focus on the economic implications of such an entity. Important recent texts here include T. R. Reid's ''The United States of Europe'' and Jeremy Rifkin's ''The European Dream.'' Neither the '' National Review'' nor the '' Chronicle of Higher Education'' doubt the appropriateness of the term in their reviews.

European federalist organisations

Various federalist organisations have been created over time supporting the idea of a federal Europe. These include the Union of European Federalists, the European Movement International, the (former)European Federalist Party

The European Federalist Party (abbreviated as PFE in French, EFP in English) is a European political party founded on 6 November 2011 in Paris. The EFP is one of the first European-oriented political parties that openly defends European federal ...

, Stand Up For Europe and Volt Europa.

Union of European Federalists

The Union of European Federalists (UEF) is a European non-governmental organisation campaigning for a Federal Europe. It consists of 20 constituent organisations and it has been active at the European, national and local levels for more than 50 years. A young branch called the Young European Federalists also exists in 30 countries of Europe.European Movement International

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.European Federalist Party

TheEuropean Federalist Party

The European Federalist Party (abbreviated as PFE in French, EFP in English) is a European political party founded on 6 November 2011 in Paris. The EFP is one of the first European-oriented political parties that openly defends European federal ...

was a pro-European, pan-European and federalist political party from 2011 to 2016 which advocated further integration of the European Union.

Stand Up for Europe

As the successor movement of theEuropean Federalist Party

The European Federalist Party (abbreviated as PFE in French, EFP in English) is a European political party founded on 6 November 2011 in Paris. The EFP is one of the first European-oriented political parties that openly defends European federal ...

, Stand Up For Europe is a pan-European NGO that advocates the foundation of a European Federation. Contrary to movements like the UEF or the former EFP, Stand Up for Europe does not command any national levels anymore, but only consists of regional city teams and the European level.

Volt Europa

Volt Europa describes itself a pan-European, progressive movement that stands for a new and inclusive way of doing politics and that wants to bring change for European citizens. The party claims that a new pan-European approach is needed to overcome current and future challenges, such as – among others – climate change, economic inequality, migration, international conflict, terrorism, and the impact of the technological revolution on jobs. Volt says that national parties are powerless in front of these challenges, because they go beyond national borders and need to be tackled by Europeans, as one people. As a transnational party, it believes it can help the European people unite, create a shared vision and understanding, exchange good practices across the continent, and come up with working policies. Volt Europa is the first European federalist movement to have elected members in two national parliaments, namely in the Netherlands and Bulgaria as well as having elected one MEP from Germany.Politicians

Guy Verhofstadt

Following the negative referendums about the European Constitution in France and the Netherlands, the former Belgian prime ministerGuy Verhofstadt

Guy Maurice Marie Louise Verhofstadt (; ; born 11 April 1953) is a Belgian politician who was the leader of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe from 2009 to 2019, and has been a member of the European Parliament (MEP) from Belgium ...

released in November 2005 his book, written in Dutch, ''Verenigde Staten van Europa'' ("United States of Europe") in which he claims – based on the results of a Eurobarometer questionnaire – that the average European citizen wants more Europe. He thinks a federal Europe should be created between those states that wish to have a federal Europe (as a form of enhanced cooperation). In other words, a core federal Europe would exist within the current EU. He also states that these core states should federalise the following five policy areas: a European social-economic policy, technology cooperation, a common justice and security policy, a common diplomacy and a European army. Following the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon (December 2009) by all member states of the EU, the outline of a common diplomatic service, known as the External Action Service of the European Union (EEAS), was set in place. On 20 February 2009, the European Parliament also voted in favour of the creation of Synchronised Armed Forces Europe (SAFE) as a first step towards a forming a true European military force.

Verhofstadt's book was awarded the first Europe Book Prize

The European Book Prize (french: Le Prix du Livre Européen) is a European Union literary award established in 2007. It is organized by the association Esprit d'Europe in Paris. It seeks to promote European values, and to contribute to European ...

, which is organised by the association Esprit d'Europe and supported by former President of the European Commission

The president of the European Commission is the head of the European Commission, the executive branch of the European Union (EU). The President of the Commission leads a Cabinet of Commissioners, referred to as the College, collectively account ...

Jacques Delors. The prize money was €20,000. The prize was declared at the European Parliament in Brussels on 5 December 2007. Swedish crime fiction writer Henning Mankell was the president of the jury of European journalists for choosing the first recipient.

While receiving the reward, Verhofstadt said: "When I wrote this book, I in fact meant it as a provocation against all those who didn't want the European Constitution. Fortunately, in the end a solution was found with the treaty, that was approved".

Viviane Reding

In 2012, Viviane Reding, the Luxembourgish Vice-president of the European Commission called in a speech inPassau

Passau (; bar, label=Central Bavarian, Båssa) is a city in Lower Bavaria, Germany, also known as the Dreiflüssestadt ("City of Three Rivers") as the river Danube is joined by the Inn from the south and the Ilz from the north.

Passau's popu ...

Germany and in a series of articles and interviews for the establishment of the United States of Europe as a way to strengthen the unity of Europe.

Matteo Renzi

The Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said in 2014 that under his leadership Italy would use its six-month-long presidency of the European Union to push for the establishment of a United States of Europe.Martin Schulz

In December 2017, Martin Schulz, who was then the new leader of the German Social Democratic Party, called for a new constitutional treaty for a "United States of Europe". Martin Schulz wants 'United States of Europe' within five years– The Guardian, 7 December 2017 He proposed that this constitution should be written by "a convention that includes civil society and the people" and that any state that declined to accept this proposed constitution should have to leave the bloc. The Guardian's view was that his proposal was "likely to be met with some resistance from Angela Merkel and other EU leaders". On that day he also stated that he would like to see a "United States of Europe" by 2025.SPD's Martin Schulz wants United States of Europe by 2025

– Politico, 7 December 2017

Notable individuals

Freddy Heineken

In 1992, Dutch businessman

In 1992, Dutch businessman Freddy Heineken

Alfred Henry "Freddy" Heineken (4 November 1923 – 3 January 2002) was a Dutch businessman for Heineken International, the brewing company bought in 1864 by his grandfather Gerard Adriaan Heineken in Amsterdam. He served as chairman of the boar ...

, after consulting with historians of the University of Leiden, Henk Wesseling and Willem van den Doel

Willem () is a Dutch and West FrisianRienk de Haan, ''Fryske Foarnammen'', Leeuwarden, 2002 (Friese Pers Boekerij), , p. 158. masculine given name. The name is Germanic, and can be seen as the Dutch equivalent of the name William in English, Gui ...

published a brochure " United States of Europe, Eurotopia?". In his work he put forward the idea of creating the United States of Europe as a confederation of 75 states that would be formed according to an ethnic and linguistic principle with a population of 5 to 10 million people.

Predictions

Future superpower

Some people, such as T.R. Reid, Andrew Reding and Mark Leonard, have argued that the power of a hypothetical United States of Europe could potentially rival that of the United States of America in the twenty-first century. Leonard cites several factors: Europe's large population, the scale of the combined Europe's economy, Europe's low inflation rates, Europe's central geographic location in the world, and certain European countries' relatively highly developedsocial organisation

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and social groups.

Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, s ...

and quality of life (when measured in terms such as hours worked per week and income distribution). Some experts claim that Europe has developed a sphere of influence called the " Eurosphere".

Assumptions about a potential full or near superpower status of a perceived Supra-national Euro state are hypothetical in nature and on the other hand contrary notions and arguments exist across a wide spectrum among analysts, experts and pundits.

Skepticisms

Some people think that the European Union is unlikely to evolve into a unified federal superstate, due to political opposition of some members. Norwegian foreign policy scholar and commentator Asle Toje has argued that the power and reach of the European Union more closely resembles a small power. In his book ''The EU As a Small Power'', he argues that the EU is a response to and function of Europe's unique historical experience in that the EU contains the remnants of not one but five past European orders. Although the 1990s and early 2000s have shown that there is policy space for greater EU engagement in European security, the EU has been unable to meet these expectations. Asle Toje expresses particular concerns over the EU's security and defence dimensionCommon Security and Defence Policy

The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) is the European Union's (EU) course of action in the fields of defence and crisis management, and a main component of the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP).

The CSDP involves the deplo ...

, where attempts at pooling resources and forming a political consensus have failed to generate the results expected. These trends, combined with shifts in global power patterns, are seen to have been accompanied by a shift in EU strategic thinking whereby great power ambitions have been scaled down and replaced by a tendency towards hedging ''vis-à-vis'' the great powers. The author uses the case of the EUFOR intervention in Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju, ...

and Chad

Chad (; ar, تشاد , ; french: Tchad, ), officially the Republic of Chad, '; ) is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic ...

to illustrate that the EU's effectiveness is hampered by a consensus–expectations gap

A consensus–expectations gap is a gap between what a group of decision-makers are expected to agree on, and what they are actually able to agree on. The expression was first used by Asle Toje in the book ''The European Union as a small power: a ...

, owing primarily to the lack of an effective decision-making mechanism. In his view, the sum of these developments is that the EU – in the current situation – will not be a great power and is taking the place of a small power in the emerging multi-polar international order.

Polls

According to Eurobarometer (2013), 69% of citizens of the EU were in favour of

According to Eurobarometer (2013), 69% of citizens of the EU were in favour of direct election

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...

s of the President of the European Commission

The president of the European Commission is the head of the European Commission, the executive branch of the European Union (EU). The President of the Commission leads a Cabinet of Commissioners, referred to as the College, collectively account ...

and 46% support the creation of a united EU army.

Two thirds of respondents think that the EU (instead of a national government alone) should make decisions on foreign policy and more than half of respondents think that the EU should also make decisions on defense.

44% of respondents support the future development of the European Union as a federation of nation states, 35% are opposed. The Nordic countries were the most negative towards a united Europe in this study, as 73% of the Nordics opposed the idea. A large majority of the people for whom the EU conjures up a positive image support the further development of the EU into a federation of nation states (56% versus 27%).

Fiction

In ''The Old Earth

''Trylogia Księżycowa'' (''The Lunar Trilogy'' or ''The Moon Trilogy'') is a trilogy of science fiction novels by the Polish writer Jerzy Żuławski, written between 1901 and 1911. It has been translated into Russian, Czech, German, English and ...

'', the third volume (1911) of Jerzy Żuławski's '' The Lunar Trilogy'', the USE is a communist state.

In the fictional universe

A fictional universe, or fictional world, is a self-consistent setting with events, and often other elements, that differ from the real world. It may also be called an imagined, constructed, or fictional realm (or world). Fictional universes may ...

of Eric Flint's best selling alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

''1632'' series, a United States of Europe is formed out of the Confederation of Principalities of Europe, which was composed of several German political units of the 1630s.

Science fiction has made particular use of the idea: '' Incompetence'', a dystopian

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

novel by ''Red Dwarf

''Red Dwarf'' is a British science fiction comedy franchise created by Rob Grant and Doug Naylor, which primarily consists of a television sitcom that aired on BBC Two between 1988 and 1999, and on Dave since 2009, gaining a cult following. T ...

'' creator Rob Grant, is a murder mystery

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

political thriller set in a federated Europe of the near future, where stupidity is a constitutionally protected right. References to a European Alliance or European Hegemony have also existed in episodes of '' Star Trek: The Next Generation'' (1987–1994). In the '' Spy High'' series of books for young adults, written by A. J. Butcher

Andrew James Butcher, better known as A.J. Butcher, is an English people, English writer best known for the futuristic teen spy series, Spy High. Butcher taught English at both Poole Grammar School and Parkstone Grammar School, in Poole, Dorset, ...

and set around the 2060s, a united Europe exists in the form of "Europa", and Andrew Roberts's 1995 book '' The Aachen Memorandum'' details a United States of Europe formed from a fraudulent referendum entitled the Aachen Referendum.Roberts, Andrew (1995). ''The Aachen Memorandum''. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Since the 2000s a number of computer strategy game

Strategy is a major Video game genres, video game genre that emphasizes thinking and planning over direct instant action in order to achieve victory. Although many types of Video game, video games can contain strategic elements, as a genre, strate ...

s set in the future have presented a unified European faction alongside other established military powers such as the United States and Russia. These include ''Euro Force'' (a 2006 expansion pack to ''Battlefield 2

''Battlefield 2'' is a first-person shooter video game, developed by DICE (company), DICE and published by Electronic Arts for Microsoft Windows in June 2005 as the third game in the Battlefield (video game series), ''Battlefield'' franchise.

P ...

'') and ''Battlefield 2142

''Battlefield 2142'' is a 2006 first-person shooter video game developed by DICE and published by Electronic Arts. It is the fourth game in the ''Battlefield'' series. ''Battlefield 2142'' is set in 2142, depicting a war known as "The Cold War ...

'' (also released in 2006, with a 2007 expansion pack). In ''Battlefield 2142'' a united Europe is shown as one of the two great superpowers on Earth, the other being Asia, despite being mostly frozen in a new ice age. The disaster theme continues with '' Tom Clancy's EndWar'' (2009), in which a nuclear war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, destroying the Middle Eastern oil supply, prompts the EU to integrate further as the "European Federation" in 2018. One game not to make bold claims of full integration is ''Shattered Union

''Shattered Union'' is a turn-based tactics video game developed by PopTop Software and published by 2K Games in October 2005.

Plot

In 2008, David Jefferson Adams becomes the 44th President of the United States following a disputed election and ...

'' (2005), set in a future civil war in the United States, with the EU portrayed as a peacekeeping force. The video game series ''Wipeout'' instead makes a clear federal reference without a military element: one of the core teams that has appeared in every game is FEISAR. This acronym stands for Federal European Industrial Science and Research. In the video game series '' Mass Effect'' set in the 22nd century, the European Union is a sovereign state.

In the backstory of the ''Fallout'' series, several European nations joined after the end of the Second World War, becoming known as the European Commonwealth. Heavily dependent on oil imports from the Middle East, the Commonwealth began a military invasion of the region in April 2052 once oil supplies began to run dry. This marked the beginning of the Resource Wars. After the oil dried up completely in 2060 and both sides were left in ruins, the Commonwealth collapsed into civil war as member states fought over whatever resources remained. It is not specified whether the European Commonwealth is a single federated nation or just an economic bloc similar to the EU.

In the anime series '' Code Geass,'' the EU (short for Euro Universe or Europia United), also known as the United Republic of Europia, is one of the three superpowers that dominate the Earth militarily, politically, culturally and economically. The political worldbuilding of the series partially resembles that of George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

's ''Nineteen-Eighty-Four

''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (also stylised as ''1984'') is a dystopian social science fiction novel and cautionary tale written by the English writer George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and final ...

'', with three superstates in roughly the same geographic positions controlling the world. Gundam 00

is a Japanese anime television series, the eleventh installment in Sunrise studio's long-running ''Gundam'' franchise comprising two seasons. The series is set on a futuristic Earth and is centered on the exploits of the fictional paramilita ...

anime series featured the Advanced European Union (AEU) as one of the major power blocs while in Gundam SEED the Eurasian Union includes both European Union and post-soviet territories.

See also

*American Committee on United Europe

The American Committee on United Europe (ACUE), founded in 1948, was a private American organization that sought to counter communism in Europe by promoting European federalism. Its first chairman was former head of the Office of Strategic Services ...

* Brand EU

* Captain Euro

Captain Euro is a fictional comic book-style superhero character, created in 1999 as a way to promote the European Union, and specifically the Euro, the single European currency that arrived in 2002. The character has been featured on a website ...

* Constituent state

* Decentralization

* Devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories h ...

* Europe a Nation

* European Civil War

* European NAvigator

* Eurocentrism

* Euroscepticism

* Fourth Reich

* Institutions of the European Union

The institutions of the European Union are the seven principal decision-making bodies of the European Union and the Euratom. They are, as listed in Article 13 of the Treaty on European Union:

* the European Parliament,

* the European Counci ...

* International Paneuropean Union

* Multi-speed Europe

Multi-speed Europe or two-speed Europe (called also "variable geometry Europe" or "Core Europe" depending on the form it would take in practice) is the idea that different parts of the European Union should integrate at different levels and pa ...

* New England Confederation

* Pan-European identity

* Pan-European nationalism

* Pan-nationalism

Pan-nationalism (from gr, πᾶν, "all", and french: nationalisme, "nationalism") is a specific term, used mainly in social sciences as a designation for those forms of nationalism that aim to transcend (overcome, expand) traditional boundari ...

* Potential Superpower (European Union)

* Pro-Europeanism

* Subsidiarity (European Union)

In the European Union, the principle of subsidiarity is the principle that decisions are retained by Member States if the intervention of the European Union is not necessary. The European Union should take action collectively only when Member St ...

* United States of Africa

* United States of Latin Africa

* World government

Notes

References

Bibliography

* (later editions available)External links

Political speeches

by

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

: ''My Revenge is Fraternity!'', in which he used the term United States of Europe.''Towards a United States of Europe''

by

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas (, ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt School, Habermas's wor ...

, at SignAndSight.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:United States Of Europe

Council of Europe

Eurofederalism

Fictional governments

Internationalism

Politics of the European Union

Proposed political unions