Erythrophore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are

The term ''chromatophore'' was adopted (following Sangiovanni's ''chromoforo'') as the name for pigment-bearing cells derived from the neural crest of cold-blooded

The term ''chromatophore'' was adopted (following Sangiovanni's ''chromoforo'') as the name for pigment-bearing cells derived from the neural crest of cold-blooded

Iridophores, sometimes also called guanophores, are chromatophores that reflect light using plates of crystalline chemochromes made from

Iridophores, sometimes also called guanophores, are chromatophores that reflect light using plates of crystalline chemochromes made from

Melanophores contain

Melanophores contain

Many species are able to translocate the pigment inside their chromatophores, resulting in an apparent change in body colour. This process, known as ''

Many species are able to translocate the pigment inside their chromatophores, resulting in an apparent change in body colour. This process, known as '' The control and mechanics of rapid pigment translocation has been well studied in a number of different species, in particular amphibians and

The control and mechanics of rapid pigment translocation has been well studied in a number of different species, in particular amphibians and

Most fish, reptiles and amphibians undergo a limited physiological colour change in response to a change in environment. This type of camouflage, known as ''background adaptation'', most commonly appears as a slight darkening or lightening of skin tone to approximately

Most fish, reptiles and amphibians undergo a limited physiological colour change in response to a change in environment. This type of camouflage, known as ''background adaptation'', most commonly appears as a slight darkening or lightening of skin tone to approximately

During vertebrate

During vertebrate

Nanotubes for noisy signal processing

''PhD Thesis''. 2005;

Video footage of octopus background adaptationTree of Life Web Project: Cephalopod Chromatophores

{{Cephalopod anatomy Cells Cephalopod zootomy Pigment cells Articles containing video clips

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compo ...

-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s, fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

, reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians ( ...

s, crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda (Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head ...

s. Mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s, in contrast, have a class of cells called melanocyte

Melanocytes are melanin-producing neural crest-derived cells located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin's epidermis, the middle layer of the eye (the uvea),

the inner ear,

vaginal epithelium, meninges,

bones,

and heart.

...

s for coloration.

Chromatophores are largely responsible for generating skin and eye colour

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

in ectotherm

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life a ...

ic animals and are generated in the neural crest

Neural crest cells are a temporary group of cells unique to vertebrates that arise from the embryonic ectoderm germ layer, and in turn give rise to a diverse cell lineage—including melanocytes, craniofacial cartilage and bone, smooth muscle, per ...

during embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

. Mature chromatophores are grouped into subclasses based on their colour (more properly "hue

In color theory, hue is one of the main properties (called color appearance parameters) of a color, defined technically in the CIECAM02 model as "the degree to which a stimulus can be described as similar to or different from stimuli that ...

") under white light: xanthophores (yellow), erythrophores (red), iridophores (reflective

Reflection is the change in direction of a wavefront at an interface between two different media so that the wavefront returns into the medium from which it originated. Common examples include the reflection of light, sound and water waves. The ' ...

/ iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to gradually change color as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, feathers, butterfl ...

), leucophores (white), melanophores (black/brown), and cyanophores (blue). While most chromatophores contain pigments that absorb specific wavelengths of light, the color of leucophores and iridophores is produced by their respective scattering and optical interference properties.

Some species can rapidly change colour through mechanisms that translocate pigment and reorient reflective plates within chromatophores. This process, often used as a type of camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the ...

, is called physiological colour change or metachrosis. Cephalopods, such as the octopus

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttle ...

, have complex chromatophore organs controlled by muscles to achieve this; whereas vertebrates such as chameleon

Chameleons or chamaeleons (family Chamaeleonidae) are a distinctive and highly specialized clade of Old World lizards with 202 species described as of June 2015. The members of this family are best known for their distinct range of colors, bein ...

s generate a similar effect by cell signalling. Such signals can be hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required ...

s or neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, any main body part or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neuro ...

s and may be initiated by changes in mood, temperature, stress or visible changes in the local environment. Chromatophores are studied by scientists to understand human disease and as a tool in drug discovery

In the fields of medicine, biotechnology and pharmacology, drug discovery is the process by which new candidate medications are discovered.

Historically, drugs were discovered by identifying the active ingredient from traditional remedies or by ...

.

Human discovery

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

mentioned the ability of the octopus

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttle ...

to change colour for both camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the ...

and signalling in his ''Historia animalium

''History of Animals'' ( grc-gre, Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν, ''Ton peri ta zoia historion'', "Inquiries on Animals"; la, Historia Animalium, "History of Animals") is one of the major texts on biology by the ancient Gr ...

'' (ca 400 BC):

Giosuè Sangiovanni

Giosuè Edoard Sangiovanni (15 January 1775 – 17 May 1849) was an Italian zoologist, the first professor of comparative anatomy in Italy and an early exponent of evolution.

Born at Laurino in the kingdom of Naples, he followed his education in p ...

was the first to describe invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

pigment-bearing cells as ' in an Italian science journal in 1819.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

described the colour-changing abilities of the cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

in ''The Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

'' (1860):

Classification of chromatophore

The term ''chromatophore'' was adopted (following Sangiovanni's ''chromoforo'') as the name for pigment-bearing cells derived from the neural crest of cold-blooded

The term ''chromatophore'' was adopted (following Sangiovanni's ''chromoforo'') as the name for pigment-bearing cells derived from the neural crest of cold-blooded vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s and cephalopods. The word itself comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words ' () meaning "colour," and ' () meaning "bearing". In contrast, the word ''chromatocyte'' (' () meaning "cell") was adopted for the cells responsible for colour found in birds and mammals. Only one such cell type, the melanocyte

Melanocytes are melanin-producing neural crest-derived cells located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin's epidermis, the middle layer of the eye (the uvea),

the inner ear,

vaginal epithelium, meninges,

bones,

and heart.

...

, has been identified in these animals.

It was only in the 1960s that chromatophores were well enough understood to enable them to be classified based on their appearance. This classification system persists to this day, even though the biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

of the pigments may be more useful to a scientific understanding of how the cells function.

Colour-producing molecules fall into two distinct classes: biochromes and structural colours or "schemochromes".Fox, DL. ''Animal Biochromes and Structural Colors: Physical, Chemical, Distributional & Physiological Features of Colored Bodies in the Animal World.'' University of California Press, Berkeley, 1976. The biochromes include true pigments, such as carotenoids and pteridine

Pteridine is an aromatic chemical compound composed of fused pyrimidine and pyrazine rings. A pteridine is also a group of heterocyclic compounds containing a wide variety of substitutions on this structure. Pterins and flavins are classes of s ...

s. These pigments selectively absorb parts of the visible light spectrum

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called ''visible light'' or simply light. A typical human eye will respond to wav ...

that makes up white light while permitting other wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tro ...

s to reach the eye of the observer. Structural colours are produced by various combinations of diffraction, reflection or scattering of light from structures with a scale around a quarter of the wavelength of light. Many such structures interfere with some wavelengths (colours) of light and transmit others, simply because of their scale, so they often produce iridescence

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to gradually change color as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, feathers, butterfl ...

by creating different colours when seen from different directions.

Whereas all chromatophores contain pigments or reflecting structures (except when there has been a mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

, as in albinism

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

), not all pigment-containing cells are chromatophores. Haem

Heme, or haem (pronounced /Help:IPA/English, hi:m/ ), is a precursor (chemistry), precursor to hemoglobin, which is necessary to bind oxygen in the bloodstream. Heme is biosynthesized in both the bone marrow and the liver.

In biochemical terms, ...

, for example, is a biochrome responsible for the red appearance of blood. It is found primarily in red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s (erythrocytes), which are generated in bone marrow throughout the life of an organism, rather than being formed during embryological development. Therefore, erythrocytes are not classified as chromatophores.

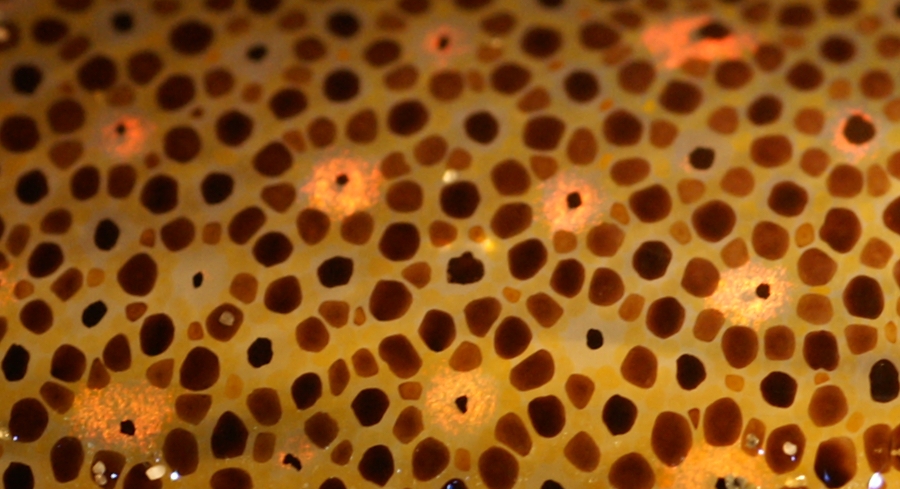

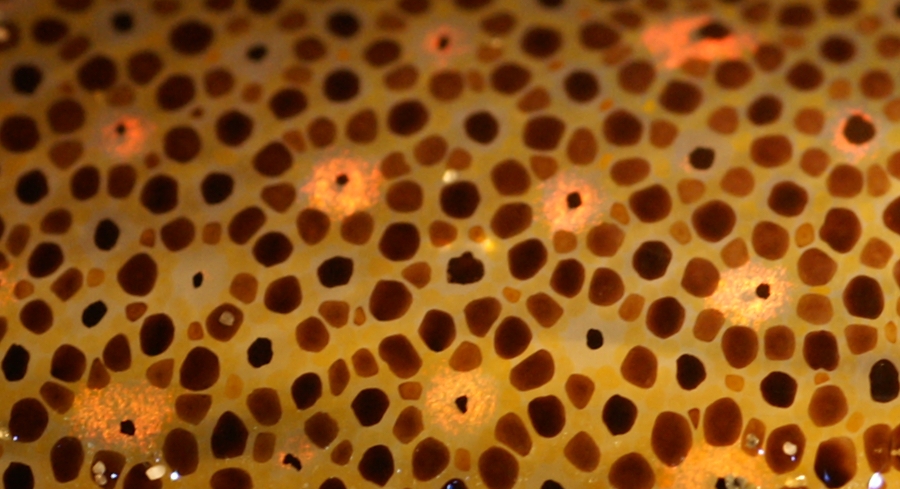

Xanthophores and erythrophores

Chromatophores that contain large amounts ofyellow

Yellow is the color between green and orange on the spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a dominant wavelength of roughly 575585 nm. It is a primary color in subtractive color systems, used in painting or color printing. In the R ...

pteridine pigments are named xanthophores; those with mainly red

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–740 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondar ...

/orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

*Orange (colour), from the color of an orange, occurs between red and yellow in the visible spectrum

* ...

carotenoids are termed erythrophores. However, vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

containing pteridine and carotenoids are sometimes found in the same cell, in which case the overall colour depends on the ratio of red and yellow pigments. Therefore, the distinction between these chromatophore types is not always clear.

Most chromatophores can generate pteridines from guanosine triphosphate

Guanosine-5'-triphosphate (GTP) is a purine nucleoside triphosphate. It is one of the building blocks needed for the synthesis of RNA during the transcription process. Its structure is similar to that of the guanosine nucleoside, the only diffe ...

, but xanthophores appear to have supplemental biochemical pathways enabling them to accumulate yellow pigment. In contrast, carotenoids are metabolised and transported to erythrophores. This was first demonstrated by rearing normally green frogs on a diet of carotene-restricted cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

s. The absence of carotene in the frogs' diet meant that the red/orange carotenoid colour 'filter' was not present in their erythrophores. This made the frogs appear blue instead of green.Bagnara JT. Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Pigment Cells in Nonmammalian Tissues. In: ''The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1998.

Iridophores and leucophores

guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is called ...

. When illuminated they generate iridescent colours because of the constructive interference of light. Fish iridophores are typically stacked guanine plates separated by layers of cytoplasm to form microscopic, one-dimensional, Bragg mirrors. Both the orientation and the optical thickness of the chemochrome determines the nature of the colour observed. By using biochromes as coloured filters, iridophores create an optical effect known as Tyndall

Tyndall (the original spelling, also Tyndale, "Tindol", Tyndal, Tindoll, Tindall, Tindal, Tindale, Tindle, Tindell, Tindill, and Tindel) is the name of an English family taken from the land they held as tenants in chief of the Kings of Engla ...

or Rayleigh scattering

Rayleigh scattering ( ), named after the 19th-century British physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt), is the predominantly elastic scattering of light or other electromagnetic radiation by particles much smaller than the wavelength of the ...

, producing bright-blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when obs ...

or -green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

colours.

A related type of chromatophore, the leucophore, is found in some fish, in particular in the tapetum lucidum

The ''tapetum lucidum'' ( ; ; ) is a layer of tissue in the eye of many vertebrates and some other animals. Lying immediately behind the retina, it is a retroreflector. It reflects visible light back through the retina, increasing the light a ...

. Like iridophores, they utilize crystalline purine

Purine is a heterocyclic compound, heterocyclic aromatic organic compound that consists of two rings (pyrimidine and imidazole) fused together. It is water-soluble. Purine also gives its name to the wider class of molecules, purines, which includ ...

s (often guanine) to reflect light. Unlike iridophores, leucophores have more organized crystals that reduce diffraction. Given a source of white light, they produce a white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

shine. As with xanthophores and erythrophores, in fish the distinction between iridophores and leucophores is not always obvious, but, in general, iridophores are considered to generate iridescent or metallic colour

A metallic color is a color that appears to be that of a polished metal. The visual sensation usually associated with metals is its metallic shine. This cannot be reproduced by a simple solid color, because the shiny effect is due to the mater ...

s, whereas leucophores produce reflective white hues.

Melanophores

Melanophores contain

Melanophores contain eumelanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amin ...

, a type of melanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

, that appears black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

or dark-brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model us ...

because of its light absorbing qualities. It is packaged in vesicles called melanosomes and distributed throughout the cell. Eumelanin is generated from tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the Gr ...

in a series of catalysed chemical reactions. It is a complex chemical containing units of dihydroxyindole and dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxylic ...

with some pyrrole

Pyrrole is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound, a five-membered ring with the formula C4 H4 NH. It is a colorless volatile liquid that darkens readily upon exposure to air. Substituted derivatives are also called pyrroles, e.g., ''N''-meth ...

rings. The key enzyme in melanin synthesis is tyrosinase

Tyrosinase is an oxidase that is the rate-limiting enzyme for controlling the production of melanin. The enzyme is mainly involved in two distinct reactions of melanin synthesis otherwise known as the Raper Mason pathway. Firstly, the hydroxylat ...

. When this protein is defective, no melanin can be generated resulting in certain types of albinism. In some amphibian species there are other pigments packaged alongside eumelanin. For example, a novel deep (wine) red-colour pigment was identified in the melanophores of phyllomedusine frogs. Some species of anole lizards, such as the ''Anolis grahami

''Anolis grahami'', commonly known as the Jamaican turquoise anole or the Graham’s anole, is a species of lizard native to the island of Jamaica, and has now also been introduced to the territory of Bermuda. It is one of many different species ...

'', use melanocytes in response to certain signals and hormonal changes, and is capable of becoming colors ranging from bright blue, brown, and black. This was subsequently identified as pterorhodin, a pteridine dimer

Dimer may refer to:

* Dimer (chemistry), a chemical structure formed from two similar sub-units

** Protein dimer, a protein quaternary structure

** d-dimer

* Dimer model, an item in statistical mechanics, based on ''domino tiling''

* Julius Dimer ...

that accumulates around eumelanin core, and it is also present in a variety of tree frog

A tree frog (or treefrog) is any species of frog that spends a major portion of its lifespan in trees, known as an arboreal state. Several lineages of frogs among the Neobatrachia have given rise to treefrogs, although they are not closely rela ...

species from Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

. While it is likely that other lesser-studied species have complex melanophore pigments, it is nevertheless true that the majority of melanophores studied to date do contain eumelanin exclusively.

Humans have only one class of pigment cell, the mammalian equivalent of melanophores, to generate skin, hair, and eye colour. For this reason, and because the large number and contrasting colour of the cells usually make them very easy to visualise, melanophores are by far the most widely studied chromatophore. However, there are differences between the biology of melanophores and that of melanocyte

Melanocytes are melanin-producing neural crest-derived cells located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin's epidermis, the middle layer of the eye (the uvea),

the inner ear,

vaginal epithelium, meninges,

bones,

and heart.

...

s. In addition to eumelanin, melanocytes can generate a yellow/red pigment called phaeomelanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

.

Cyanophores

Nearly all the vibrant blues in animals and plants are created bystructural coloration

Structural coloration in animals, and a few plants, is the production of colour by microscopically structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with visible light instead of pigments, although some structural coloration occurs in combination wi ...

rather than by pigments. However, some types of ''Synchiropus splendidus

''Synchiropus splendidus'', the mandarinfish or mandarin dragonet, is a small, brightly colored member of the dragonet family, which is popular in the saltwater aquarium trade. The mandarinfish is native to the Pacific, ranging approximately from ...

'' do possess vesicles of a cyan

Cyan () is the color between green and blue on the visible spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a predominant wavelength between 490 and 520 nm, between the wavelengths of green and blue.

In the subtractive color system, or CMYK color ...

biochrome of unknown chemical structure in cells named cyanophores. Although they appear unusual in their limited taxonomic range, there may be cyanophores (as well as further unusual chromatophore types) in other fish and amphibians. For example, brightly coloured chromatophores with undefined pigments are found in both poison dart frog

Poison dart frog (also known as dart-poison frog, poison frog or formerly known as poison arrow frog) is the common name of a group of frogs in the family Dendrobatidae which are native to tropical Central and South America. These species are ...

s and glass frog

The glass frogs belong to the amphibian family Centrolenidae ( order Anura). While the general background coloration of most glass frogs is primarily lime green, the abdominal skin of some members of this family is transparent and translucent ...

s, and atypical dichromatic chromatophores, named ''erythro-iridophores'' have been described in '' Pseudochromis diadema''.

Pigment translocation

physiological

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

colour change'', is most widely studied in melanophores, since melanin is the darkest and most visible pigment. In most species with a relatively thin dermis

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. It is divided i ...

, the dermal melanophores tend to be flat and cover a large surface area. However, in animals with thick dermal layers, such as adult reptiles, dermal melanophores often form three-dimensional units with other chromatophores. These dermal chromatophore units (DCU) consist of an uppermost xanthophore or erythrophore layer, then an iridophore layer, and finally a basket-like melanophore layer with processes covering the iridophores.

Both types of melanophore are important in physiological colour change. Flat dermal melanophores often overlay other chromatophores, so when the pigment is dispersed throughout the cell the skin appears dark. When the pigment is aggregated toward the centre of the cell, the pigments in other chromatophores are exposed to light and the skin takes on their hue. Likewise, after melanin aggregation in DCUs, the skin appears green through xanthophore (yellow) filtering of scattered light from the iridophore layer. On the dispersion of melanin, the light is no longer scattered and the skin appears dark. As the other biochromatic chromatophores are also capable of pigment translocation, animals with multiple chromatophore types can generate a spectacular array of skin colours by making good use of the divisional effect.

The control and mechanics of rapid pigment translocation has been well studied in a number of different species, in particular amphibians and

The control and mechanics of rapid pigment translocation has been well studied in a number of different species, in particular amphibians and teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tel ...

fish. It has been demonstrated that the process can be under hormonal

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required fo ...

or neuronal

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. No ...

control or both and for many species of bony fishes it is known that chromatophores can respond directly to environmental stimuli like visible light, UV-radiation, temperature, pH, chemicals, etc. Neurochemicals that are known to translocate pigment include noradrenaline

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad'', ...

, through its receptor

Receptor may refer to:

* Sensory receptor, in physiology, any structure which, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and responds to a ...

on the surface on melanophores. The primary hormones involved in regulating translocation appear to be the melanocortin

The melanocortins are a family of neuropeptide hormones which are the ligands of the melanocortin receptorsEricson, M.D., et al., ''Bench-top to clinical therapies: A review of melanocortin ligands from 1954 to 2016.'' Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basi ...

s, melatonin, and melanin-concentrating hormone

Melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), also known as pro-melanin stimulating hormone (PMCH), is a cyclic 19-amino acid orexigenic hypothalamic peptide originally isolated from the pituitary gland of teleost fish, where it controls skin pigmentation ...

(MCH), that are produced mainly in the pituitary, pineal gland, and hypothalamus, respectively. These hormones may also be generated in a paracrine Paracrine signaling is a form of cell signaling, a type of cellular communication in which a cell produces a signal to induce changes in nearby cells, altering the behaviour of those cells. Signaling molecules known as paracrine factors diffuse ove ...

fashion by cells in the skin. At the surface of the melanophore, the hormones have been shown to activate specific G-protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily-related p ...

s that, in turn, transduce the signal into the cell. Melanocortins result in the dispersion of pigment, while melatonin and MCH results in aggregation.

Numerous melanocortin, MCH and melatonin receptors have been identified in fish and frogs, including a homologue of ''MC1R

The melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), also known as melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor (MSHR), melanin-activating peptide receptor, or melanotropin receptor, is a G protein–coupled receptor that binds to a class of pituitary peptide hormones ...

'', a melanocortin receptor known to regulate skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other cuticle, animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have diffe ...

and hair colour in humans. It has been demonstrated that ''MC1R'' is required in zebrafish for dispersion of melanin. Inside the cell, cyclic adenosine monophosphate

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP, cyclic AMP, or 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate) is a second messenger important in many biological processes. cAMP is a derivative of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and used for intracellular signal transd ...

(cAMP) has been shown to be an important second messenger

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form or cell signaling, encompassing both first me ...

of pigment translocation. Through a mechanism not yet fully understood, cAMP influences other proteins such as protein kinase A

In cell biology, protein kinase A (PKA) is a family of enzymes whose activity is dependent on cellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP). PKA is also known as cAMP-dependent protein kinase (). PKA has several functions in the cell, including regulatio ...

to drive molecular motors

Molecular motors are natural (biological) or artificial molecular machines that are the essential agents of movement in living organisms. In general terms, a motor is a device that consumes energy in one form and converts it into motion or mech ...

carrying pigment containing vesicles along both microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 11 an ...

s and microfilament

Microfilaments, also called actin filaments, are protein filaments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that form part of the cytoskeleton. They are primarily composed of polymers of actin, but are modified by and interact with numerous other pr ...

s.

Background adaptation

Most fish, reptiles and amphibians undergo a limited physiological colour change in response to a change in environment. This type of camouflage, known as ''background adaptation'', most commonly appears as a slight darkening or lightening of skin tone to approximately

Most fish, reptiles and amphibians undergo a limited physiological colour change in response to a change in environment. This type of camouflage, known as ''background adaptation'', most commonly appears as a slight darkening or lightening of skin tone to approximately mimic

MIMIC, known in capitalized form only, is a former simulation computer language developed 1964 by H. E. Petersen, F. J. Sansom and L. M. Warshawsky of Systems Engineering Group within the Air Force Materiel Command at the Wright-Patterson AFB in ...

the hue of the immediate environment. It has been demonstrated that the background adaptation process is vision-dependent (it appears the animal needs to be able to see the environment to adapt to it), and that melanin translocation in melanophores is the major factor in colour change. Some animals, such as chameleons and anoles, have a highly developed background adaptation response capable of generating a number of different colours very rapidly. They have adapted the capability to change colour in response to temperature, mood, stress levels, and social cues, rather than to simply mimic their environment.

Development

embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

, chromatophores are one of a number of cell types generated in the neural crest

Neural crest cells are a temporary group of cells unique to vertebrates that arise from the embryonic ectoderm germ layer, and in turn give rise to a diverse cell lineage—including melanocytes, craniofacial cartilage and bone, smooth muscle, per ...

, a paired strip of cells arising at the margins of the neural tube

In the developing chordate (including vertebrates), the neural tube is the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system, which is made up of the brain and spinal cord. The neural groove gradually deepens as the neural fold become elevated, a ...

. These cells have the ability to migrate long distances, allowing chromatophores to populate many organs of the body, including the skin, eye, ear, and brain. Fish melanophores and iridophores have been found to contain the smooth muscle regulatory proteins alponinand caldesmon

Caldesmon is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''CALD1'' gene.

Caldesmon is a calmodulin binding protein. Like calponin, caldesmon tonically inhibits the ATPase activity of myosin in smooth muscle.

This gene encodes a calmodulin- and ac ...

. Leaving the neural crest in waves, chromatophores take either a dorsolateral route through the dermis, entering the ectoderm

The ectoderm is one of the three primary germ layers formed in early embryonic development. It is the outermost layer, and is superficial to the mesoderm (the middle layer) and endoderm (the innermost layer). It emerges and originates from t ...

through small holes in the basal lamina

The basal lamina is a layer of extracellular matrix secreted by the epithelial cells, on which the epithelium sits. It is often incorrectly referred to as the basement membrane, though it does constitute a portion of the basement membrane. The ba ...

, or a ventromedial route between the somites

The somites (outdated term: primitive segments) are a set of bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form in the embryonic stage of somitogenesis, along the head-to-tail axis in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites subdivide i ...

and the neural tube. The exception to this is the melanophores of the retinal pigmented epithelium of the eye. These are not derived from the neural crest. Instead, an outpouching of the neural tube generates the optic cup, which, in turn, forms the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

.

When and how multipotent Pluripotency: These are the cells that can generate into any of the three Germ layers which imply Endodermal, Mesodermal, and Ectodermal cells except tissues like the placenta.

According to Latin terms, Pluripotentia means the ability for many thin ...

chromatophore precursor cells (called ''chromatoblasts'') develop into their daughter subtypes is an area of ongoing research. It is known in zebrafish embryos, for example, that by 3 days after fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

each of the cell classes found in the adult fish—melanophores, xanthophores and iridophores—are already present. Studies using mutant fish have demonstrated that transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

s such as ''kit'', ''sox10

Transcription factor SOX-10 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''SOX10'' gene.

Function

This gene encodes a member of the SOX gene family, SOX (Testis-determining factor, SRY-related HMG-box) family of transcription factors involved ...

'', and ''mitf

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor also known as class E basic helix-loop-helix protein 32 or bHLHe32 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''MITF'' gene.

MITF is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor ...

'' are important in controlling chromatophore differentiation. If these proteins are defective, chromatophores may be regionally or entirely absent, resulting in a leucistic

Leucism () is a wide variety of conditions that result in the partial loss of pigmentation in an animal—causing white, pale, or patchy coloration of the skin, hair, feathers, scales, or cuticles, but not the eyes. It is occasionally spelled ' ...

disorder.

Practical applications

Chromatophores are sometimes used in applied research. For example, zebrafish larvae are used to study how chromatophores organise and communicate to accurately generate the regular horizontal striped pattern as seen in adult fish. This is seen as a usefulmodel

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

system for understanding patterning in the evolutionary developmental biology field. Chromatophore biology has also been used to model human condition or disease, including melanoma

Melanoma, also redundantly known as malignant melanoma, is a type of skin cancer that develops from the pigment-producing cells known as melanocytes. Melanomas typically occur in the skin, but may rarely occur in the mouth, intestines, or eye ( ...

and albinism. Recently, the gene responsible for the melanophore-specific ''golden'' zebrafish strain, ''Slc24a5

SLC may refer to:

Places

* Salt Lake City, Utah

* Salt Lake City International Airport, IATA Airport Code

Education

* Sarah Lawrence College, NY

* School Leaving Certificate (Nepal)

* St. Lawrence College, Ontario, Canada

* Small Learning Comm ...

'', was shown to have a human equivalent that strongly correlates with skin colour

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents and or individ ...

.

Chromatophores are also used as a biomarker

In biomedical contexts, a biomarker, or biological marker, is a measurable indicator of some biological state or condition. Biomarkers are often measured and evaluated using blood, urine, or soft tissues to examine normal biological processes, ...

of blindness in cold-blooded species, as animals with certain visual defects fail to background adapt to light environments. Human homologues of receptors that mediate pigment translocation in melanophores are thought to be involved in processes such as appetite

Appetite is the desire to eat food items, usually due to hunger. Appealing foods can stimulate appetite even when hunger is absent, although appetite can be greatly reduced by satiety. Appetite exists in all higher life-forms, and serves to regu ...

suppression and tanning

Tanning may refer to:

*Tanning (leather), treating animal skins to produce leather

*Sun tanning, using the sun to darken pale skin

**Indoor tanning, the use of artificial light in place of the sun

**Sunless tanning, application of a stain or dye t ...

, making them attractive targets for drugs

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhalat ...

. Therefore, pharmaceutical companies have developed a biological assay

An assay is an investigative (analytic) procedure in laboratory medicine, mining, pharmacology, environmental biology and molecular biology for qualitatively assessing or quantitatively measuring the presence, amount, or functional activity of a ...

for rapidly identifying potential bioactive compounds using melanophores from the African clawed frog

The African clawed frog (''Xenopus laevis'', also known as the xenopus, African clawed toad, African claw-toed frog or the ''platanna'') is a species of African aquatic frog of the family Pipidae. Its name is derived from the three short claws o ...

. Other scientists have developed techniques for using melanophores as biosensor

A biosensor is an analytical device, used for the detection of a chemical substance, that combines a biological component with a physicochemical detector.

The ''sensitive biological element'', e.g. tissue, microorganisms, organelles, cell rece ...

s, and for rapid disease detection (based on the discovery that pertussis toxin

Pertussis toxin (PT) is a protein-based AB5-type exotoxin produced by the bacterium ''Bordetella pertussis'', which causes whooping cough. PT is involved in the colonization of the respiratory tract and the establishment of infection. Res ...

blocks pigment aggregation in fish melanophores). Potential military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

applications of chromatophore-mediated colour changes have been proposed, mainly as a type of active camouflage

Active camouflage or adaptive camouflage is camouflage that adapts, often rapidly, to the surroundings of an object such as an animal or military vehicle. In theory, active camouflage could provide perfect concealment from visual detection.

Activ ...

, which could as in cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

make objects nearly invisible.Lee INanotubes for noisy signal processing

''PhD Thesis''. 2005;

University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

.

Cephalopod chromatophores

Coleoid

Subclass Coleoidea,

or Dibranchiata, is the grouping of cephalopods containing all the various taxa popularly thought of as "soft-bodied" or "shell-less" (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish). Unlike its extant sister group, Nautiloidea, whose ...

cephalopods (including octopuses, squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

s and cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

) have complex multicellular organs that they use to change colour rapidly, producing a wide variety of bright colours and patterns. Each chromatophore unit is composed of a single chromatophore cell and numerous muscle, nerve, glial, and sheath cells. Inside the chromatophore cell, pigment granules are enclosed in an elastic sac, called the cytoelastic sacculus. To change colour the animal distorts the sacculus form or size by muscular contraction, changing its translucency

In the field of optics, transparency (also called pellucidity or diaphaneity) is the physical property of allowing light to pass through the material without appreciable scattering of light. On a macroscopic scale (one in which the dimensions a ...

, reflectivity, or opacity. This differs from the mechanism used in fish, amphibians, and reptiles in that the shape of the sacculus is changed, rather than translocating pigment vesicles within the cell. However, a similar effect is achieved.

Octopuses and most cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

can operate chromatophores in complex, undulating chromatic displays, resulting in a variety of rapidly changing colour schemata. The nerves that operate the chromatophores are thought to be positioned in the brain in a pattern isomorphic to that of the chromatophores they each control. This means the pattern of colour change functionally matches the pattern of neuronal activation. This may explain why, as the neurons are activated in iterative signal cascade, one may observe waves of colour changing. Like chameleons, cephalopods use physiological colour change for social interaction. They are also among the most skilled at camouflage, having the ability to match both the colour distribution and the texture

Texture may refer to:

Science and technology

* Surface texture, the texture means smoothness, roughness, or bumpiness of the surface of an object

* Texture (roads), road surface characteristics with waves shorter than road roughness

* Texture ...

of their local environment with remarkable accuracy.

See also

* Animal coloration * Chromophore *Thylakoid

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a thylakoid membrane surrounding a thylakoid lumen. Chloroplast thyl ...

Notes

External links

*Video footage of octopus background adaptation

{{Cephalopod anatomy Cells Cephalopod zootomy Pigment cells Articles containing video clips