Erastes (Ancient Greece) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged romantic relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the ''

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged romantic relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the ''

Since the publication in 1978 of

Since the publication in 1978 of

The ''erastês-erômenos'' relationship played a role in the

The ''erastês-erômenos'' relationship played a role in the

The

The  The 5th century BC poet

The 5th century BC poet

The nature of Spartan pederasty is in dispute among ancient sources and modern historians. Some think Spartan views on pederasty and homoeroticism were more chaste than those of other parts of Greece, while others find no significant difference between them.

According to

The nature of Spartan pederasty is in dispute among ancient sources and modern historians. Some think Spartan views on pederasty and homoeroticism were more chaste than those of other parts of Greece, while others find no significant difference between them.

According to

Project Gutenberg text

* Ferrari, Gloria. ''FIgures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece''. University of Chicago Press, 2002. * Hubbard, Thomas K. ''Homosexuality in Greece and Rome''. University of California Press, 200

Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a sourcebook of basic documents in translation

* Johnson, Marguerite, and Ryan, Terry. ''Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook''. Routledge, 2005. * Lear, Andrew, and

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged romantic relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the ''

Pederasty in ancient Greece was a socially acknowledged romantic relationship between an older male (the ''erastes'') and a younger male (the ''eromenos

In ancient Greece, an ''eromenos'' was the younger and passive (or 'receptive') partner in a male homosexual relationship. The partner of an ''eromenos'' was the ''erastes'', the older and active partner. The ''eromenos'' was often depicted as a ...

'') usually in his teens. It was characteristic of the Archaic

Archaic is a period of time preceding a designated classical period, or something from an older period of time that is also not found or used currently:

*List of archaeological periods

**Archaic Sumerian language, spoken between 31st - 26th cent ...

and Classical periods. The influence of pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

on Greek culture of these periods was so pervasive that it has been called "the principal cultural model for free relationships between citizens."

Some scholars locate its origin in initiation ritual, particularly rites of passage on Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

, where it was associated with entrance into military life and the religion of Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

. It has no formal existence in the Homeric epics

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, and seems to have developed in the late 7th century BC as an aspect of Greek homosocial culture, which was characterized also by athletic

Athletic may refer to:

* An athlete, a sportsperson

* Athletic director, a position at many American universities and schools

* Athletic type, a physical/psychological type in the classification of Ernst Kretschmer

* Athletic of Philadelphia, a ...

and artistic nudity

Depictions of nudity include all of the representations or portrayals of the unclothed human body in visual media. In a picture-making civilization, pictorial conventions continually reaffirm what is natural in human appearance, which is part of ...

, delayed marriage for aristocrats, symposia

''Symposia'' is a genus of South American araneomorph spiders in the family Cybaeidae, and was first described by Eugène Simon in 1898.

Species

it contains six species in Venezuela and Colombia:

*''Symposia bifurca'' Roth, 1967 – Venezuela ...

, and the social seclusion of women.

Pederasty was both idealized and criticized in ancient literature

Ancient literature comprises religious and scientific documents, tales, poetry and plays, royal edicts and declarations, and other forms of writing that were recorded on a variety of media, including stone, stone tablets, papyri, palm leaves, and ...

and philosophy. The argument has recently been made that idealization was universal in the Archaic period; criticism began in Athens as part of the general Classical Athenian reassessment of Archaic culture.

Scholars have debated the role or extent of pederasty, which is likely to have varied according to local custom and individual inclination. The English word "pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

" in present-day usage might imply the abuse

Abuse is the improper usage or treatment of a thing, often to unfairly or improperly gain benefit. Abuse can come in many forms, such as: physical or verbal maltreatment, injury, assault, violation, rape, unjust practices, crimes, or other t ...

of minors in certain jurisdictions, but Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

law, for instance, recognized both consent

Consent occurs when one person voluntarily agrees to the proposal or desires of another. It is a term of common speech, with specific definitions as used in such fields as the law, medicine, research, and sexual relationships. Consent as und ...

and age

Age or AGE may refer to:

Time and its effects

* Age, the amount of time someone or something has been alive or has existed

** East Asian age reckoning, an Asian system of marking age starting at 1

* Ageing or aging, the process of becoming olde ...

as factors in regulating sexual behavior.

Terminology

Since the publication in 1978 of

Since the publication in 1978 of Kenneth Dover

Sir Kenneth James Dover, (11 March 1920 – 7 March 2010) was a distinguished British classical scholar and academic. He was president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, from 1976 to 1986. In addition, he was president of the British Academy fro ...

's work '' Greek Homosexuality'', the terms ''erastês'' and ''erômenos'' have been standard for the two pederastic roles. Both words derive from the Greek verb ''erô'', ''erân'', "to love"; see also eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the e ...

. In Dover's strict dichotomy, the ''erastês'' (, plural ''erastai'') is the older sexual actor, seen as the active or dominant participant, with the suffix ''-tês'' (-) denoting agency

Agency may refer to:

Organizations

* Institution, governmental or others

** Advertising agency or marketing agency, a service business dedicated to creating, planning and handling advertising for its clients

** Employment agency, a business that ...

. ''Erastês'' should be distinguished from Greek ''paiderastês'', which meant "lover of boys" usually with a negative connotation. The Greek word ''paiderastia'' () is an abstract noun

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, ...

. It is formed from ''paiderastês'', which in turn is a compound of ''pais'' ("child", plural ''paides'') and ''erastês'' (see below). Although the word ''pais'' can refer to a child of either sex, ''paiderastia'' is defined by Liddell and Scott's ''Greek-English Lexicon'' as "the love of boys", and the verb ''paiderasteuein'' as "to be a lover of boys". The ''erastês'' himself might only be in his early twenties, and thus the age difference between the two males who engage in sexual activity might be negligible.

The word ''erômenos'', or "beloved" (ἐρώμενος, plural ''eromenoi''), is the masculine form of the present passive participle from ''erô'', viewed by Dover as the passive or subordinate sexual participant. An ''erômenos'' can also be called ''pais'', "child".Dover, ''Greek Homosexuality'', p. 16. The ''pais'' was regarded as a future citizen, not an "inferior object of sexual gratification", and was portrayed with respect in art. The word can be understood as an endearment such as a parent might use, found also in the poetry of Sappho

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied ...

and a designation of only relative age. Both art and other literary references show that the ''erômenos'' was at least a teen, with modern age estimates ranging from 13 to 20, or in some cases up to 30. Most evidence indicates that to be an eligible ''erômenos'', a youth would be of an age when an aristocrat began his formal military training, that is, from fifteen to seventeen. As an indication of physical maturity, the ''erômenos'' was sometimes as tall as or taller than the older ''erastês'', and may have his first facial hair. Another word used by the Greeks for the younger sexual participant was ''paidika'', a neuter

Neuter is a Latin adjective meaning "neither", and can refer to:

* Neuter gender, a grammatical gender, a linguistic class of nouns triggering specific types of inflections in associated words

*Neuter pronoun

*Neutering, the sterilization of an ...

plural adjective

In linguistics, an adjective ( abbreviated ) is a word that generally modifies a noun or noun phrase or describes its referent. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives were considered one of the ...

("things having to do with children") treated syntactically

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituency) ...

as masculine singular.

In poetry and philosophical literature, the ''erômenos'' is often an embodiment of idealized youth; a related ideal depiction of youth in Archaic culture was the ''kouros

kouros ( grc, κοῦρος, , plural kouroi) is the modern term given to free-standing Ancient Greek sculptures that depict nude male youths. They first appear in the Archaic period in Greece and are prominent in Attica and Boeotia, with a les ...

'', the long-haired male statuary nude

Nudity is the state of being in which a human is without clothing.

The loss of body hair was one of the physical characteristics that marked the biological evolution of modern humans from their hominin ancestors. Adaptations related to h ...

. In ''The Fragility of Goodness

''The Fragility of Goodness'' is a 1986 philosophical book by Martha Nussbaum, which deals with philosophical topics such as the meaning of life by seeking the dialogue with ancient philosophers, such as Aristotle, to whom Nussbaum pays much attent ...

'', Martha Nussbaum

Martha Craven Nussbaum (; born May 6, 1947) is an American philosopher and the current Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago, where she is jointly appointed in the law school and the philoso ...

, following Dover, defines the ideal ''erômenos'' as

a beautiful creature without pressing needs of his own. He is aware of his attractiveness, but self-absorbed in his relationship with those who desire him. He will smile sweetly at the admiring lover; he will show appreciation for the other's friendship, advice, and assistance. He will allow the lover to greet him by touching, affectionately, his genitals and his face, while he looks, himself, demurely at the ground. … The inner experience of an ''erômenos'' would be characterized, we may imagine, by a feeling of proud self-sufficiency. Though the object of importunate solicitation, he is himself not in need of anything beyond himself. He is unwilling to let himself be explored by the other's needy curiosity, and he has, himself, little curiosity about the other. He is something like a god, or the statue of a god.Dover insisted that the active role of the ''erastês'' and the passivity of the ''erômenos'' is a distinction "of the highest importance", but subsequent scholars have tried to present a more varied picture of the behaviors and values associated with ''paiderastia''. Although ancient Greek writers use ''erastês'' and ''erômenos'' in a pederastic context, the words are not technical terms for social roles, and can refer to the "lover" and "beloved" in other hetero- and homosexual couples.

Origins

The Greek practice of pederasty came suddenly into prominence at the end of the Archaic period of Greek history. There is a brass plaque fromCrete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

, about 650–625 BC, which is the oldest surviving representation of pederastic custom. Such representations appear from all over Greece in the next century; literary sources show it as being established custom in many cities by the 5th century BC.

Cretan pederasty as a social institution seems to have been grounded in an initiation which involved abduction

Abduction may refer to:

Media

Film and television

* "Abduction" (''The Outer Limits''), a 2001 television episode

* " Abduction" (''Death Note'') a Japanese animation television series

* " Abductions" (''Totally Spies!''), a 2002 episode of an ...

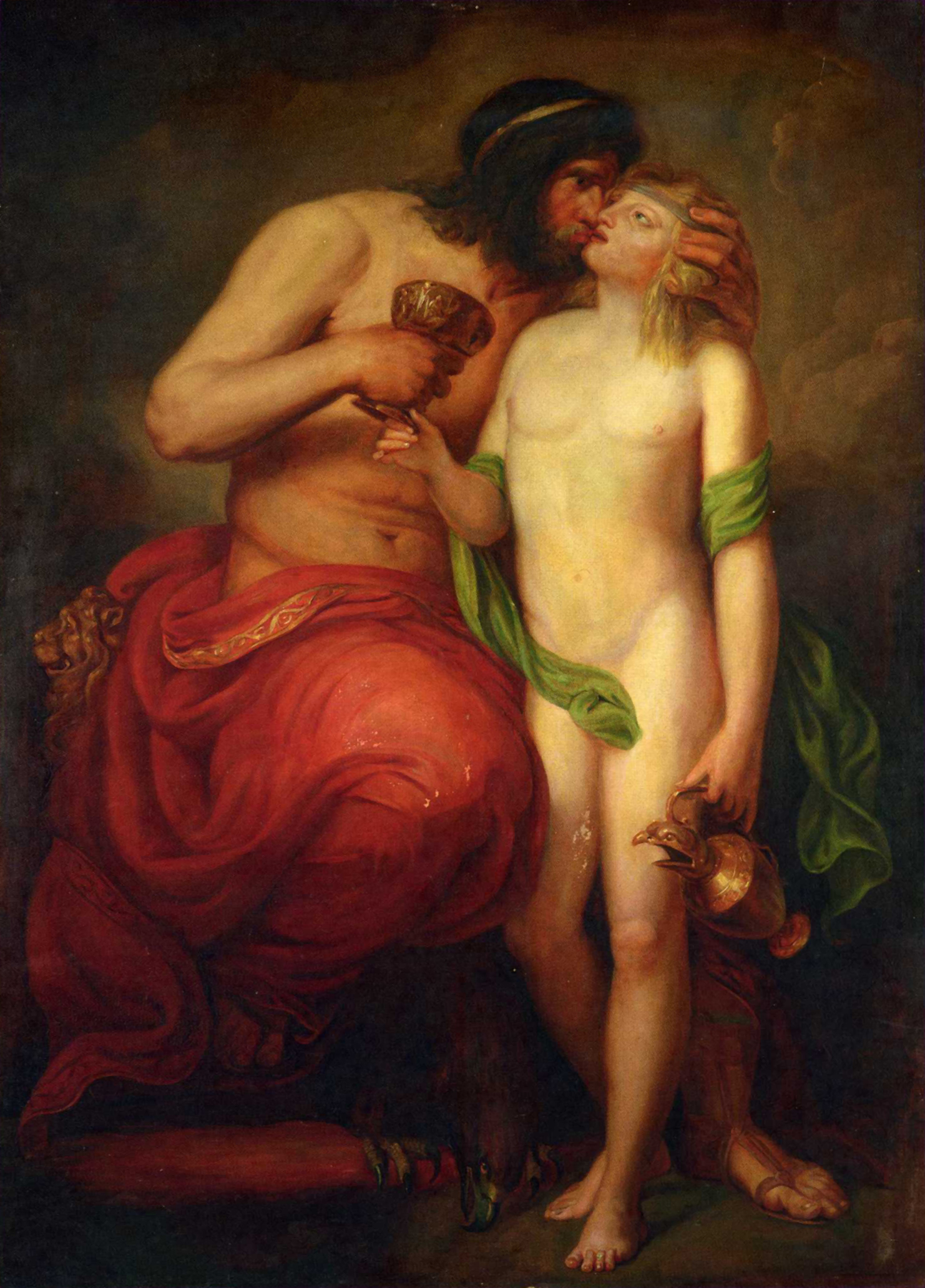

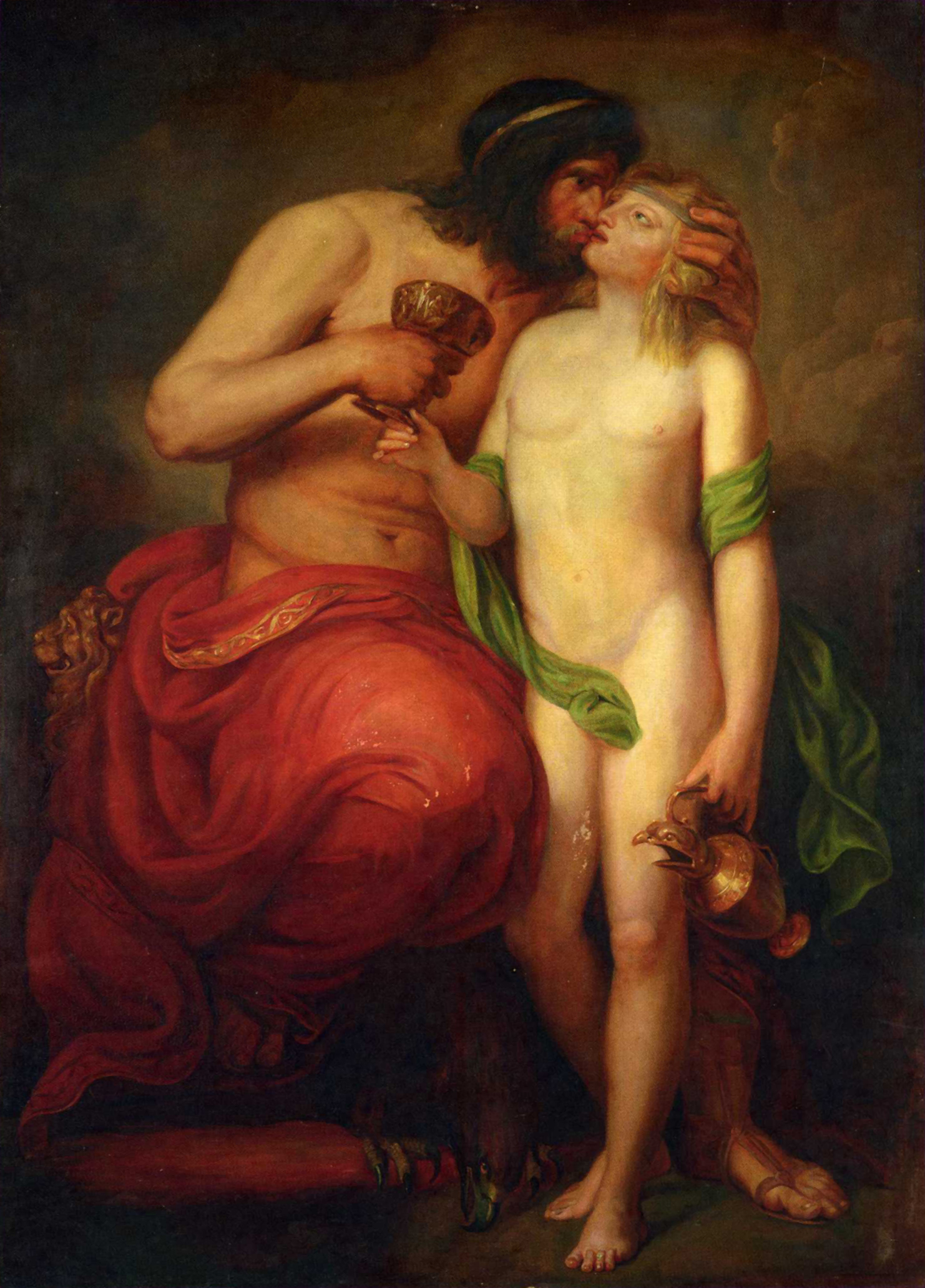

. A man ( grc, φιλήτωρ – ''philetor'', "lover") selected a youth, enlisted the chosen one's friends to help him, and carried off the object of his affections to his ''andreion'', a sort of men's club or meeting hall. The youth received gifts, and the ''philetor'' along with the friends went away with him for two months into the countryside, where they hunted and feasted. At the end of this time, the ''philetor'' presented the youth with three contractually required gifts: military attire, an ox, and a drinking cup. Other costly gifts followed. Upon their return to the city, the youth sacrificed the ox to Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

, and his friends joined him at the feast. He received special clothing that in adult life marked him as ''kleinos'', "famous, renowned". The initiate was called a ''parastatheis'', "he who stands beside", perhaps because, like Ganymede the cup-bearer of Zeus, he stood at the side of the ''philetor'' during meals in the ''andreion'' and served him from the cup that had been ceremonially presented. In this interpretation, the formal custom reflects myth and ritual

Myth and ritual are two central components of religious practice. Although myth and ritual are commonly united as parts of religion, the exact relationship between them has been a matter of controversy among scholars. One of the approaches to thi ...

.

Social aspects

The ''erastês-erômenos'' relationship played a role in the

The ''erastês-erômenos'' relationship played a role in the Classical Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

social and educational system, had its own complex social-sexual etiquette and was an important social institution among the upper classes. Pederasty has been understood as educative, and Greek authors from Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his fo ...

to Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

felt it naturally present in the context of aristocratic education (''paideia

''Paideia'' (also spelled ''paedeia'') ( /paɪˈdeɪə/; Greek: παιδεία, ''paideía'') referred to the rearing and education of the ideal member of the ancient Greek polis or state. These educational ideals later spread to the Greco-Rom ...

''). In general, pederasty as described in the Greek literary sources is an institution reserved for free citizens, perhaps to be regarded as a dyadic

Dyadic describes the interaction between two things, and may refer to:

*Dyad (sociology), interaction between a pair of individuals

**The dyadic variation of Democratic peace theory

*Dyadic counterpoint, the voice-against-voice conception of polyp ...

mentorship. According to historian Sarah Iles Johnston

Sarah Iles Johnston (born 25 October 1957) is an American academic working at Ohio State University. She is primarily known for her research into ancient Greek myths and religion, focusing on how myths helped to create and sustain belief in t ...

, "pederasty was widely accepted in Greece as part of a male's coming-of-age, even if its function is still widely debated". The scene of Xenophon's ''Symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

'', and also that of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

's ''Protagoras

Protagoras (; el, Πρωταγόρας; )Guthrie, p. 262–263. was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and rhetorical theorist. He is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue '' Protagoras'', Plato credits him with inventing t ...

'', is set at Callias III

Callias ( el, Kαλλίας) was an ancient Athenian aristocrat and political figure. He was the son of Hipponicus and an unnamed woman (she later married Pericles), an Alcmaeonid and the third member of one of the most distinguished Athenian ...

's house during a banquet hosted by him for his beloved Autolykos in honour of a victory gained by the handsome young man in the pentathlon

A pentathlon is a contest featuring five events. The name is derived from Greek: combining the words ''pente'' (five) and -''athlon'' (competition) ( gr, πένταθλον). The first pentathlon was documented in Ancient Greece and was part of t ...

at the Panathenaic Games

The Panathenaic Games ( grc, Παναθήναια) were held every four years in Athens in Ancient Greece from 566 BC to the 3rd century AD. These Games incorporated religious festival, ceremony (including prize-giving), athletic competitions, a ...

.

In Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

, in order for the suitor to carry out the ritual abduction, the father had to approve him as worthy of the honor. Among the Athenians, as Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

claims in Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

's ''Symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

,'' "Nothing f what concerns the boy

F, or f, is the sixth Letter (alphabet), letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is English alphabet#Let ...

is kept hidden from the father, by an ideal

Ideal may refer to:

Philosophy

* Ideal (ethics), values that one actively pursues as goals

* Platonic ideal, a philosophical idea of trueness of form, associated with Plato

Mathematics

* Ideal (ring theory), special subsets of a ring considere ...

lover". In order to protect their sons from inappropriate attempts at seduction, fathers appointed slaves called ''pedagogues'' to watch over their sons. However, according to Aeschines

Aeschines (; Greek: , ''Aischínēs''; 389314 BC) was a Greek statesman and one of the ten Attic orators.

Biography

Although it is known he was born in Athens, the records regarding his parentage and early life are conflicting; but it seems p ...

, Athenian fathers would pray that their sons would be handsome and attractive, with the full knowledge that they would then attract the attention of men and "be the objects of fights because of erotic passions".

The age-range when boys entered into such relationships was consonant with that of Greek girls given in marriage, often to adult husbands many years their senior. Boys, however, usually had to be courted and were free to choose their mate, while marriages for girls were arranged for economic and political advantage at the discretion of father and suitor. These connections were also an advantage for a youth and his family, as the relationship with an influential older man resulted in an expanded social network. Thus, some considered it desirable to have had many admirers or mentors, if not necessarily lovers ''per se'', in one's younger years. Typically, after their sexual relationship had ended and the young man had married, the older man and his protégé would remain on close terms throughout their life.

In parts of Greece, pederasty was an acceptable form of homoeroticism

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homose ...

that had other, less socially accepted manifestations, such as the sexual use of slaves or being a '' pornos'' ( prostitute) or ''hetairos'' (the male equivalent of a hetaira

Hetaira (plural hetairai (), also hetaera (plural hetaerae ), ( grc, ἑταίρα, "companion", pl. , la, hetaera, pl. ) was a type of prostitute in ancient Greece, who served as an artist, entertainer and conversationalist in addition to pro ...

). Male prostitution was treated as a perfectly routine matter and visiting prostitutes of either sex were considered completely acceptable for a male citizen. However, adolescent citizens of free status who prostituted themselves were sometimes ridiculed, and were permanently prohibited by Attic law from performing some seven official functions because it was believed that since they had sold their own body "for the pleasure of others" (, ''eph' hybrei''), they would not hesitate to sell the interests of the community as a whole. If they, or an adult citizen of free status who had prostituted himself, performed any of the official functions prohibited to them by law (in later life), they were liable to prosecution and punishment. However, if they did not perform those specific functions, did not present themselves for the allocation of those functions and declared themselves ineligible if they were somehow mistakenly elected to perform those specific functions, they were safe from prosecution and punishment. As non-citizens visiting or residing in a city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

could not perform official functions in any case whatsoever, they could prostitute themselves as much as they wanted.

Political expression

Transgressions of the customs pertaining to the proper expression of homosexuality within the bounds of ''pederaistia'' could be used to damage the reputation of a public figure. In his speech "Against Timarchus "Against Timarchus" ( el, Κατὰ Τιμάρχου) was a speech by Aeschines accusing Timarchus of being unfit to involve himself in public life. The case was brought about in 346–5 BC, in response to Timarchus, along with Demosthenes, bringing ...

" in 346 BC, the Athenian politician Aeschines

Aeschines (; Greek: , ''Aischínēs''; 389314 BC) was a Greek statesman and one of the ten Attic orators.

Biography

Although it is known he was born in Athens, the records regarding his parentage and early life are conflicting; but it seems p ...

argues against further allowing Timarchus

Timarchus or Timarch was a Greek noble and a satrap of the Seleucid Empire during the reign of his ally King Antiochus IV Epiphanes. After Antiochus IV's death, he styled himself an independent ruler in his domain in the Persian east of the Em ...

, an experienced middle-aged politician, certain political rights, as Attic law prohibited anyone who had prostituted himself from exercising those rights and Timarchus was known to have spent his adolescence as the sexual partner of a series of wealthy men in order to obtain money. Such a law existed because it was believed that anyone who had sold their own body would not hesitate to sell the interests of the city-state. Aeschines won his case, and Timarchus was sentenced to ''atimia

Atimia (Ατιμία) was a form of disenfranchisement used under classical Athenian democracy.

Under democracy in ancient Greece, only free adult Greek males were enfranchised as full citizens. Women, foreigners, children and slaves were not ful ...

'' (disenfranchisement and civic disempowerment). Aeschines acknowledges his own dalliances with beautiful boys, the erotic poems he dedicated to these youths, and the scrapes he has gotten into as a result of his affairs, but he emphasizes that none of these were mediated by money. A financial motive thus was viewed as threatening a man's status as free.

By contrast, as expressed in Pausanias' speech in Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

's ''Symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

,'' pederastic love was said to be favorable to democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

and feared by tyrants, because the bond between the ''erastês'' and ''erômenos'' was stronger than that of obedience to a despotic ruler. Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of t ...

states that "Hieronymus the Aristotelian says that love with boys was fashionable because several tyrannies had been overturned by young men in their prime, joined together as comrades in mutual sympathy". He gives as examples of such pederastic couples the Athenians Harmodius and Aristogeiton

Harmodius (Greek: Ἁρμόδιος, ''Harmódios'') and Aristogeiton (Ἀριστογείτων, ''Aristogeíton''; both died 514 BC) were two lovers in Classical Athens who became known as the Tyrannicides (τυραννόκτονοι, ''tyranno ...

, who were credited (perhaps symbolically) with the overthrow of the tyrant Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; el, Ἱππίας ὁ Ἠλεῖος; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, ...

and the establishment of democracy, and also Chariton and Melanippus. Others, such as Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, claimed that the Cretan lawgivers encouraged pederasty as a means of population control

Population control is the practice of artificially maintaining the size of any population. It simply refers to the act of limiting the size of an animal population so that it remains manageable, as opposed to the act of protecting a species from ...

, by directing love and sexual desire into non-procreative channels:

and the lawgiver has devised many wise measures to secure the benefit of moderation at table, and the segregation of the women in order that they may not bear many children, for which purpose he instituted association with the male sex.

Philosophical expression

Phaedrus in Plato's ''Symposium'' remarks:For I know not any greater blessing to a young man who is beginning in life than a virtuous lover, or to a lover than a beloved youth. For the principle, I say, neither kindred, nor honor, nor wealth, nor any motive is able to implant so well as love. Of what am I speaking? Of the sense of honor and dishonor, without which neither states nor individuals ever do any good or great work… And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonor and emulating one another in honor; and it is scarcely an exaggeration to say that when fighting at each other’s side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.In ''

Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

'', Plato takes a much more austere stance to homosexuality than in previous works, stating:

... one certainly should not fail to observe that when male unites with female for procreation the pleasure experienced is held to be due to nature, but contrary to nature when male mates with male or female with female, and that those first guilty of such enormitiesPlato states here that "we all", possibly referring to society as a whole or simply his social group, believe the story of Ganymede's homosexuality to have been fabricated by the Cretans to justify immoral behaviours. The Athenian stranger in Plato's ''Laws'' blames pederasty for promoting civil strife and driving many to their wits' end, and recommends the prohibition of sexual intercourse with youths, laying out a path whereby this may be accomplished.he Cretans He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...were impelled by their slavery to pleasure. And we all accuse the Cretans of concocting the story about Ganymede.

In myth and religion

The

The myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrati ...

of Ganymede's abduction by Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

was invoked as a precedent for the pederastic relationship, as Theognis

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, f ...

asserts to a friend:

There is some pleasure in loving a boy (''paidophilein''), since once in fact even the son of CronusThe myth of Ganymede's abduction, however, was not taken seriously by some in Athenian society, and deemed to be a Cretan fabrication designed to justifyhat is, Zeus A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...king of immortals, fell in love with Ganymede, seized him, carried him off to Olympus, and made him divine, keeping the lovely bloom of boyhood (''paideia''). So, don't be astonished,Simonides Simonides of Ceos (; grc-gre, Σιμωνίδης ὁ Κεῖος; c. 556–468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets estee ..., that I too have been revealed as captivated by love for a handsome boy.

homoeroticism

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homose ...

.

The scholar Joseph Pequigney states:

NeitherHomer Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the '' Iliad'' and the '' Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of ...norHesiod Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...ever explicitly ascribes homosexual experiences to the gods or to heroes.

The 5th century BC poet

The 5th century BC poet Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

constructed the story of a sexual pederastic relationship between Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

and Pelops

In Greek mythology, Pelops (; ) was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region (, lit. "Pelops' Island"). He was the son of Tantalus and the father of Atreus.

He was venerated at Olympia, where his cult developed into the founding myth of the ...

, intended to replace an earlier story of cannibalism that Pindar deemed an unsavoury representation of the Gods. The story tells of Poseidon's love for a mortal boy, Pelops, who wins a chariot race with help from his admirer Poseidon.

Though examples of such a custom exist in earlier Greek works, myths providing examples of young men who were the lovers of gods began to emerge in Classical literature

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

, around the 6th century BC. In these later tales, pederastic love is ascribed to Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

(with Ganymede), Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

(with Pelops

In Greek mythology, Pelops (; ) was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region (, lit. "Pelops' Island"). He was the son of Tantalus and the father of Atreus.

He was venerated at Olympia, where his cult developed into the founding myth of the ...

), Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

(with Cyparissus

In Greek mythology, Cyparissus or Kyparissos (Ancient Greek: Κυπάρισσος, "cypress") was a boy beloved by Apollo or in some versions by other deities. In the best-known version of the story, the favorite companion of Cyparissus was a tam ...

, Hyacinthus

''Hyacinthus'' is a small genus of bulbous, spring-blooming perennials. They are fragrant flowering plants in the family Asparagaceae, subfamily Scilloideae and are commonly called hyacinths (). The genus is native to the area of the eastern Me ...

and Admetus

In Greek mythology, Admetus (; Ancient Greek: ''Admetos'' means 'untamed, untameable') was a king of Pherae in Thessaly.

Biography

Admetus succeeded his father Pheres after whom the city was named. His mother was identified as Periclymen ...

), Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracians, Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned Ancient Greek poetry, poet and, according to ...

, Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adopt ...

, Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

, Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

, and Pan. All the Olympian gods

upright=1.8, Fragment of a relief (1st century BC1st century AD) depicting the twelve Olympians carrying their attributes in procession; from left to right: Hestia (scepter), Hermes (winged cap and staff), Aphrodite (veiled), Ares (helmet and s ...

except Ares

Ares (; grc, Ἄρης, ''Árēs'' ) is the Greek god of war and courage. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. The Greeks were ambivalent towards him. He embodies the physical valor necessary for success in war ...

are purported to have had these relationships, which some scholars argue demonstrates that the specific customs of ''paiderastia'' originated in initiatory rituals.

Myths attributed to the homosexuality of Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

are very late and often post-pagan additions. The tale of Dionysus and Ampelos

Ampelos ( grc-gre, Ἂμπελος, lit." Vine") or Ampelus ( Latin) was a personification of the grapevine and lover of Dionysus in Greek and Roman mythology. He was a satyr that either turned into a Constellation or the grape vine, due to Di ...

was written by the Egyptian poet Nonnus

Nonnus of Panopolis ( grc-gre, Νόννος ὁ Πανοπολίτης, ''Nónnos ho Panopolítēs'', 5th century CE) was the most notable Greek epic poet of the Imperial Roman era. He was a native of Panopolis (Akhmim) in the Egyptian Theb ...

sometime between the 4th and 5th centuries CE, making it unreliable. Likewise, the tale of Dionysus and Polymnus Prosymnus ( Ancient Greek: Πρόσυμνος) (also known as Polymnus (Πόλυμνος) and Hypolipnus) was, in Greek mythology, a shepherd living near the reputedly bottomless Alcyonian Lake, hazardous to swimmers, which lay in the Argolid, on ...

, which tells that the former anally masturbated with a fig branch over the latter's grave, was written by Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

, whose aim was to discredit pagan mythology.

Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

, however, believed that these myths are only literary versions expressing or explaining the "overt" homosexuality of Greek Archaic culture, the distinctiveness of which he contrasted to attitudes in other ancient societies such as Egypt and Israel.

Creative expression

Visual arts

Greek vase painting

Ancient Greek pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it (over 100,000 painted vases are recorded in the Corpus vasorum antiquorum), it has e ...

is a major source for scholars seeking to understand attitudes and practices associated with ''paiderastia''. Hundreds of pederastic scenes are depicted on Attic black-figure vases. In the early 20th century, John Beazley

Sir John Davidson Beazley, (; 13 September 1885 – 6 May 1970) was a British classical archaeologist and art historian, known for his classification of Attic vases by artistic style. He was Professor of Classical Archaeology and Art at the ...

classified pederastic vases into three types:

* The ''erastês'' and ''erômenos'' stand facing each other; the ''erastês'', knees bent, reaches with one hand for the beloved's chin and with the other for his genitals.

* The ''erastês'' presents the ''erômenos'' with a small gift, sometimes an animal.

* The standing lovers engage in intercrural sex

Intercrural sex, which is also known as coitus interfemoris, thigh sex (or thighing) and interfemoral sex, is a type of non-penetrative sex in which the penis is placed between the receiving partner's thighs and friction is generated via thrus ...

.

Certain gifts traditionally given by the ''erômenos'' became symbols that contributed to interpreting a given scene as pederastic. Animal gifts—most commonly hares and roosters, but also deer and felines—point toward hunting as an aristocratic pastime and as a metaphor for sexual pursuit.

These animal gifts were commonly given to boys, whereas women often received money as a gift for sex. This difference in gifts furthered the closeness of pederastic relations. Women received money as a product of the sexual exchange and boys were given culturally significant gifts. Gifts given to boys are commonly depicted in ancient Greek art

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic d ...

, but money given to women for sex is not.

The explicit nature of some images has led in particular to discussions of whether the ''erômenos'' took active pleasure in the sex act. The youthful beloved is never pictured with an erection; his penis "remains flaccid even in circumstances to which one would expect the penis of any healthy adolescent to respond willy-nilly". Fondling the youth's genitals was one of the most common images of pederastic courtship on vases, a gesture indicated also in Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his fo ...

' comedy ''Birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

'' (line 142). Some vases do show the younger partner as sexually responsive, prompting one scholar to wonder, "What can the point of this act have been unless lovers in fact derived some pleasure from feeling and watching the boy's developing organ wake up and respond to their manual stimulation?"

Chronological study of the vase paintings also reveals a changing aesthetic in the depiction of the ''erômenos''. In the 6th century BC, he is a young beardless man with long hair, of adult height and physique, usually nude. As the 5th century begins, he has become smaller and slighter, "barely pubescent", and often draped as a girl would be. No inferences about social customs should be based on this element of the courtship scene alone.

Poetry

There are many pederastic references among the works of theMegara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

n poet Theognis

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, f ...

addressed to Cyrnus (Greek ''Kyrnos''). Some portions of the Theognidean corpus are probably not by the individual from Megara, but rather represent "several generations of wisdom poetry

Literary scholars have identified at least two historical types of poetry as wisdom poetry. The first kind of wisdom poetry was written in ancient Mesopotamia, including the Sumerian '' Hymn to Enlil, the All-Beneficent'' Scholars of medieval lit ...

". The poems are "social, political, or ethical precepts transmitted to Cyrnus as part of his formation into an adult Megarian aristocrat in Theognis' own image".

The relationship between Theognis and Kyrnos eludes categorization. Although it was assumed in antiquity that Kyrnos was the poet's ''erômenos'', the poems that are most explicitly erotic are not addressed to himthe poetry on "the joys and sorrows" of pederasty seem more apt for sharing with a fellow ''erastês'', perhaps in the setting of the symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

"the relationship, in any case, is left vague". In general, Theognis (and the tradition that appears under his name) treats the pederastic relationship as heavily pedagogical.

The poetic traditions of Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

and Aeolia featured poets such as Anacreon

Anacreon (; grc-gre, Ἀνακρέων ὁ Τήϊος; BC) was a Greek lyric poet, notable for his drinking songs and erotic poems. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets. Anacreon wrote all of his poetry in the ...

, Mimnermus

Mimnermus ( grc-gre, Μίμνερμος ''Mímnermos'') was a Greek elegiac poet from either Colophon or Smyrna in Ionia, who flourished about 632–629 BC (i.e. in the 37th Olympiad, according to Suda). He was strongly influenced by the exampl ...

and Alcaeus, who composed many of the sympotic skolia

A skolion (from grc, σκόλιον) (pl. skolia), also scolion (pl. scolia), was a song sung by invited guests at banquets in ancient Greece. Often extolling the virtues of the gods or heroic men, skolia were improvised to suit the occasion and ...

that were to become later part of the mainland tradition. Ibycus

Ibycus (; grc-gre, Ἴβυκος; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet, a citizen of Rhegium in Magna Graecia, probably active at Samos during the reign of the tyrant Polycrates and numbered by the scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria in the canon ...

came from Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popu ...

in the Greek west and entertained the court of Polycrates

Polycrates (; grc-gre, Πολυκράτης), son of Aeaces, was the tyrant of Samos from the 540s BC to 522 BC. He had a reputation as both a fierce warrior and an enlightened tyrant.

Sources

The main source for Polycrates' life and activi ...

in Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a sepa ...

with pederastic verses. By contrast with Theognis, these poets portray a version of pederasty that is non-pedagogical, focused exclusively on love and seduction. Theocritus

Theocritus (; grc-gre, Θεόκριτος, ''Theokritos''; born c. 300 BC, died after 260 BC) was a Greek poet from Sicily and the creator of Ancient Greek pastoral poetry.

Life

Little is known of Theocritus beyond what can be inferred from h ...

, a Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

poet, describes a kissing contest for youths that took place at the tomb of a certain Diocles of Megara

Diocles of Megara ( el, Διοκλῆς ὁ Μεγαρεύς) was an ancient Greek warrior from Athens who died a hero in Megara.

Diocles was known for his love for boys. He was exiled from Athens for an unknown reason and took refuge in Megara, ...

, a warrior renowned for his love of boys; he notes that invoking Ganymede was proper to the occasion.

Sexual practices

Vase paintings and references to the ''erômenos''anal sex

Anal sex or anal intercourse is generally the insertion and thrusting of the erect penis into a person's anus, or anus and rectum, for sexual pleasure.Sepages 270–271for anal sex information, anpage 118for information about the clitoris. O ...

between pederastic couples. Some vase paintings, which historian William Percy considers a fourth type of pederastic scene in addition to Beazley

Beazley is a surname, and may refer to

* Charles Raymond Beazley, British historian

* Christopher Beazley, British politician

* David M. Beazley, American software engineer

* John Beazley, British classical scholar

* Kim Beazley, current Austr ...

's three, show the ''erastês'' seated with an erection and the ''erômenos'' either approaching or climbing into his lap. The composition of these scenes is the same as that for depictions of women mounting men who are seated and aroused for intercourse. As a cultural norm considered apart from personal preference, anal penetration was most often seen as dishonorable to the one penetrated, or shameful, because of "its potential appearance of being turned into a woman" and because it was feared that it may distract the ''erômenos'' from playing the active, penetrative role later in life. A fable attributed to Aesop

Aesop ( or ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales cre ...

tells how Aeschyne (Shame) consented to enter the human body from behind only as long as Eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the e ...

did not follow the same path, and would fly away at once if he did. A man who acted as the receiver during anal intercourse may have been the recipient of the insult "''kinaidos''", meaning effeminate. No shame was associated with intercrural penetration or any other act that did not involve anal penetration. This interpretation is largely based on the thesis presented by Kenneth Dover

Sir Kenneth James Dover, (11 March 1920 – 7 March 2010) was a distinguished British classical scholar and academic. He was president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, from 1976 to 1986. In addition, he was president of the British Academy fro ...

in 1979. Oral sex is likewise not depicted, or directly suggested; anal and oral penetration seem to have been reserved for prostitutes or slaves.

Dover maintained that the ''erômenos'' was ideally not supposed to feel "unmanly" desire for the ''erastês''. Nussbaum argues that the depiction of the ''erômenos'' as deriving no sexual pleasure from sex with the ''erastês'' "may well be a cultural norm that conceals a more complicated reality", as the ''erômenos'' is known to have frequently felt intense affection for his ''erastês'' and there is evidence that he experienced sexual arousal with him as well. In Plato's ''Phaedrus Phaedrus may refer to:

People

* Phaedrus (Athenian) (c. 444 BC – 393 BC), an Athenian aristocrat depicted in Plato's dialogues

* Phaedrus (fabulist) (c. 15 BC – c. AD 50), a Roman fabulist

* Phaedrus the Epicurean (138 BC – c. 70 BC), an Epic ...

'', it is related that, with time, the ''erômenos'' develops a "passionate longing" for his ''erastês'' and a "reciprocal love" (''anteros

In Greek mythology, Anteros (; Ancient Greek: Ἀντέρως ''Antérōs'') was the god of requited love (literally "love returned" or "counter-love") and also the punisher of those who scorn love and the advances of others, or the avenger of u ...

'') for him that is a replica of the ''erastês''’ love. The ''erômenos'' is also said to have a desire "similar to the erastes', albeit weaker, to see, to touch, to kiss and to lie with him".

Regional characteristics

Athens

Many of the practices described above concern Athens, whileAttic pottery

Ancient Greek pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it (over 100,000 painted vases are recorded in the Corpus vasorum antiquorum), it has ex ...

is a major source for modern scholars attempting to understand the institution of pederasty. In Athens, as elsewhere, ''pederastia'' appears to have been characteristic of the aristocracy. The age of youth depicted has been estimated variously from 12 to 18. A number of Athenian laws addressed the pederastic relationship.

The Greek East

Unlike theDorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionians) ...

, where an older male would usually have only one ''erômenos'' (younger boy), in the east a man might have several ''erômenoi'' over the course of his life. Poems of Alcaeus indicate that the older male would customarily invite his ''erômenos'' to dine with him.

Crete

Greek pederasty was seemingly already institutionalized inCrete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

at the time of Thaletas

Thaletas or Thales of Crete (Greek: Θαλῆς or Θαλήτας) was an early Greek musician and lyric poet.

Biography

Historicity

The position of Thaletas is one of the most interesting, and at the same time most difficult points, in that ...

, which included a "Dance of Naked Youths".Percy, William A. ''Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece'', University of Illinois Press, 1996, p79 It has been suggested both Crete and Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

influenced Athenian pederasty.

Sparta

The nature of Spartan pederasty is in dispute among ancient sources and modern historians. Some think Spartan views on pederasty and homoeroticism were more chaste than those of other parts of Greece, while others find no significant difference between them.

According to

The nature of Spartan pederasty is in dispute among ancient sources and modern historians. Some think Spartan views on pederasty and homoeroticism were more chaste than those of other parts of Greece, while others find no significant difference between them.

According to Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

, a relationship ("association") between a man and a boy could be tolerated, but only if it was based around friendship and love and not solely around physical, sexual attraction, in which case it was considered "an abomination" tantamount to incest. Conversely, Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

states that, when Spartan boys reached puberty, they became available for sexual relationships with older males. Aelian Aelian or Aelianus may refer to:

* Aelianus Tacticus, Greek military writer of the 2nd century, who lived in Rome

* Casperius Aelianus, Praetorian Prefect, executed by Trajan

* Claudius Aelianus, Roman writer, teacher and historian of the 3rd centu ...

talks about the responsibilities of an older Spartan citizen to younger less sexually experienced males.

Historian Thomas F. Scanlon argues Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

, during its Dorian

Dorian may refer to:

Ancient Greece

* Dorians, one of the main ethnic divisions of ancient Greeks

* Doric Greek, or Dorian, the dialect spoken by the Dorians

Art and entertainment Films

* ''Dorian'' (film), the Canadian title of the 2004 film ' ...

polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

time, was the first city to practice athletic nudity

Nude recreation refers to recreational activities which some people engage in while nude. Historically, the ancient Olympics were nude events. There remain some societies in Africa, Oceania, and South America that continue to engage in everyday p ...

, and one of the first to formalize pederasty. Sparta also imported Thaletas' songs from Crete.

In Sparta, the ''erastês'' was regarded as a guardian of the ''erômenos'' and was held responsible for any wrongdoings of the latter.I. Sykoutris, ''Introduction to Symposium'', 43 Researchers of the Spartan civilization, such as Paul Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge (born 24 March 1947)"CARTLEDGE, Prof. Paul Anthony", ''Who's Who 2010'', A & C Black, 2010online edition/ref> is a British ancient historian and academic. From 2008 to 2014 he was the A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek C ...

, remain uncertain about the sexual aspect of the institution. Cartledge underscores that the terms "εισπνήλας" ("eispnílas") and "αΐτας" ("aḯtas") have a moralistic and pedagogic content, indicating a relationship with a paternalistic character, but argues that sexual relations were possible in some or most cases. The nature of these possible sexual relations remains, however, disputed and lost to history.

Megara

Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

cultivated good relations with Sparta, and may have been culturally attracted to emulate Spartan practices in the 7th century, when pederasty is postulated to have first been formalized in Dorian cities. One of the first cities after Sparta to be associated with the custom of athletic nudity

Nude recreation refers to recreational activities which some people engage in while nude. Historically, the ancient Olympics were nude events. There remain some societies in Africa, Oceania, and South America that continue to engage in everyday p ...

, Megara

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

was home to the runner Orsippus Orsippus ( grc-gre, Ὄρσιππος) was a Greek runner from Megara who was famed as the first to run the footrace naked at the Olympic Games and "first of all Greeks to be crowned victor naked."Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may r ...

who was famed as the first to run the footrace naked at the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a multi ...

and "first of all Greeks to be crowned victor naked". In one poem, the Megaran poet Theognis

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, f ...

saw athletic nudity as a prelude to pederasty, writing, "Happy is the lover who works out naked / And then goes home to sleep all day with a beautiful boy."

Boeotia

In Thebes, the mainpolis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

in Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, wikt:Βοιωτία, Βοιωτία; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is pa ...

, renowned for its practice of pederasty, the tradition was enshrined in the founding myth

An origin myth is a myth that describes the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the creation or cosmogonic myth, a story that describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have sto ...

of the city. The story was meant to teach by counterexample. It depicts Laius

In Greek mythology, King Laius (pronounced ), or Laios ( el, Λάϊος) of Thebes was a key personage in the Theban founding myth.

Family

Laius was the son of Labdacus. He was the father, by Jocasta, of Oedipus, who killed him.

Mythol ...

, one of the mythical ancestors of the Thebans, in the role of a lover who betrays the father and rapes the son. Other Boeotian pederastic myths are the stories of Narcissus

Narcissus may refer to:

Biology

* ''Narcissus'' (plant), a genus containing daffodils and others

People

* Narcissus (mythology), Greek mythological character

* Narcissus (wrestler) (2nd century), assassin of the Roman emperor Commodus

* Tiberius ...

and of Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adopt ...

and Iolaus

In Greek mythology, Iolaus (; Ancient Greek: Ἰόλαος ''Iólaos'') was a Theban divine hero. He was famed for being Heracles' nephew and for helping with some of his Labors, and also for being one of the Argonauts.

Family

Iolaus was t ...

.

The legislator Philolaus of Corinth Philolaus of Corinth ( el, Φιλόλαος ὁ Κορίνθιος) was an ancient Greek lawmaker at Thebes.

Philolaus belonged by birth to the Bacchiadae family of Corinth who arose as Nomothete (lawmaker) at Thebes. He became the lover of D ...

, lover of the stadion race winner Diocles of Corinth Diocles of Corinth ( el, Διοκλῆς ὁ Κορίνθιος) was an ancient Greek athlete from Corinth who won the stadion race of the 13th Ancient Olympic Games in 728 BCE at Olympia. The stadion race (about 180 meters) was the only competiti ...

at the Ancient Olympic Games of 728 BC, crafted laws for the Thebans in the 8th century BC that gave special support to male unions, contributing to the development of Theban pederasty in which, unlike other places in ancient Greece, it favored the continuity of the union of male couples even after the younger man reached adulthood, as was the case with him and Diocles, who lived together in Thebes until the end of their lives.

According to Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

, Theban pederasty was instituted as an educational device for boys in order to "soften, while they were young, their natural fierceness", and to "temper the manners and characters of the youth". According to tradition, the Sacred Band of Thebes

The Sacred Band of Thebes (Ancient Greek: , ''Hierós Lókhos'') was a troop of select soldiers, consisting of 150 pairs of male lovers which formed the elite force of the Theban army in the 4th century BC, ending Spartan domination. Its pr ...

comprised pederastic couples.

Boeotian pottery, in contrast to that of Athens, does not exhibit the three types of pederastic scenes identified by Beazley. The limited survival and cataloguing of pottery that can be proven to have been made in Boeotia diminishes the value of this evidence in distinguishing a specifically local tradition of ''paiderastia''.

Modern scholarship

The ethical views held in ancient societies, such asAthens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

, Thebes, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

, Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

, Elis

Elis or Ilia ( el, Ηλεία, ''Ileia'') is a historic region in the western part of the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece. It is administered as a regional unit of the modern region of Western Greece. Its capital is Pyrgos. Until 2011 it was ...

and others, on the practice of pederasty have been explored by scholars only since the end of the 19th century. One of the first to do so was John Addington Symonds

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although m ...

, who wrote his seminal work ''A Problem in Greek Ethics'' in 1873, but after a private edition of 10 copies (1883), only in 1901 was the work published in revised form. Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rights Warren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for ...

expanded the scope of the study, with his 1914 work, ''Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk''. The text examines homoerotic practices of all types, not only pederastic ones, and ranges over cultures spanning the globe. In Germany the study was continued by classicist Paul Brandt writing under the pseudonym Hans Licht, who published ''Sexual Life in Ancient Greece'' in 1932.

Kenneth J. Dover

Sir Kenneth James Dover, (11 March 1920 – 7 March 2010) was a distinguished British classical scholar and academic. He was president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, from 1976 to 1986. In addition, he was president of the British Academy fro ...

's seminal '' Greek Homosexuality'' (1978) triggered a number of debates which still continue. 20th-century sociologist Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (, ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and ho ...

declared that pederasty was "problematized" in Greek culture, that it was "the object of a special—and especially intense—moral preoccupation", which was "subjected to an interplay of positive and negative interplays so complex as to make the ethics that governed it difficult to decipher". A modern line of thought leading from Dover to Foucault to David M. Halperin

David M. Halperin (born April 2, 1952) is an American theorist in the fields of gender studies, queer theory, critical theory, material culture and visual culture. He is the cofounder of '' GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies'', and author ...

holds that the ''erômenos'' did not reciprocate the love and desire of the ''erastês'', and that the relationship was factored on a sexual domination of the younger by the older, a politics of penetration held to be true of all adult male Athenians' relations with their social inferiors—boys, women and slaves. This theory was also propounded by Eva Keuls.

Similarly, Enid Bloch argues that many Greek boys in these relationships may have been traumatized

Psychological trauma, mental trauma or psychotrauma is an emotional response to a distressing event or series of events, such as accidents, rape, or natural disasters. Reactions such as psychological shock and psychological denial are typical ...

by knowing that they were violating social customs, since the "most shameful thing that could happen to any Greek male was penetration by another male". She further argues that vases showing "a boy standing perfectly still as a man reaches out for his genitals" indicate the boy may have been "psychologically immobilized, unable to move or run away". From this and the previous perspectives, the relationships are characterized and factored on a power differential between the participants, and as essentially asymmetrical.

Other scholars point to more artwork on vases, poetry and philosophical works such as the Platonic

Plato's influence on Western culture was so profound that several different concepts are linked by being called Platonic or Platonist, for accepting some assumptions of Platonism, but which do not imply acceptance of that philosophy as a whole. It ...

discussion of ''anteros

In Greek mythology, Anteros (; Ancient Greek: Ἀντέρως ''Antérōs'') was the god of requited love (literally "love returned" or "counter-love") and also the punisher of those who scorn love and the advances of others, or the avenger of u ...

'', "love returned", all of which show tenderness and desire and love on the part of the ''erômenos'' matching and responding to that of the ''erastês''. Critics of the posture defended by Dover, Bloch and their followers also point out that they ignore all material which argued against their "overly theoretical" interpretation of a human and emotional relationship and counter that "clearly, a mutual, consensual bond was formed", and that it is "a modern fairy tale that the younger ''erômenos'' was never aroused".

Halperin's position has been criticized by Thomas K. Hubbard as a "persistently negative and judgmental rhetoric implying exploitation and domination as the fundamental characteristics of pre-modern sexual models", challenging it as a polemic of "mainstream assimilationist gay apologists" and an attempt to "demonize and purge from the movement" all non-orthodox male sexualities, especially those involving adults and adolescents.

As classical historian Robin Osborne

Robin Grimsey Osborne, (born 11 March 1957) is an English historian of classical antiquity, who is particularly interested in Ancient Greece.

Early life

He grew up in Little Bromley, attending Little Bromley County Primary School and then Colche ...

has pointed out, historical discussion of ''paiderastia'' is complicated by 21st-century moral standards:It is the historian's job to draw attention to the personal, social, political and indeed moral issues behind the literary and artistic representations of the Greek world. The historian's job is to present pederasty and all, to make sure that … we come face to face with the way the glory that was Greece was part of a world in which many of our owncore values Core or cores may refer to: Science and technology * Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages * Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding * Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber * Core, the centra ...find themselves challenged rather than reinforced.Robin Osborne Robin Grimsey Osborne, (born 11 March 1957) is an English historian of classical antiquity, who is particularly interested in Ancient Greece. Early life He grew up in Little Bromley, attending Little Bromley County Primary School and then Colche ..., ''Greek History'' (Routledge, 2004), pp. 1

online

and 21.

See also

*Age disparity in sexual relationships

Concepts of age disparity in sexual relationships, including what defines an age disparity, have developed over time and vary among societies. Differences in age preferences for mates can stem from partner availability, gender roles, and evoluti ...

*Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

*Autolycus of Athens

Autolycus ( grc-gre, Αὐτόλυκος; fl. 5th century BC), son of Lykon, was a young Athenian athlete of singular beauty and the lover of Callias. It is in honour of a victory gained by him in the pentathlon at the Panathenaic Games that Cal ...