Equus curvidens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

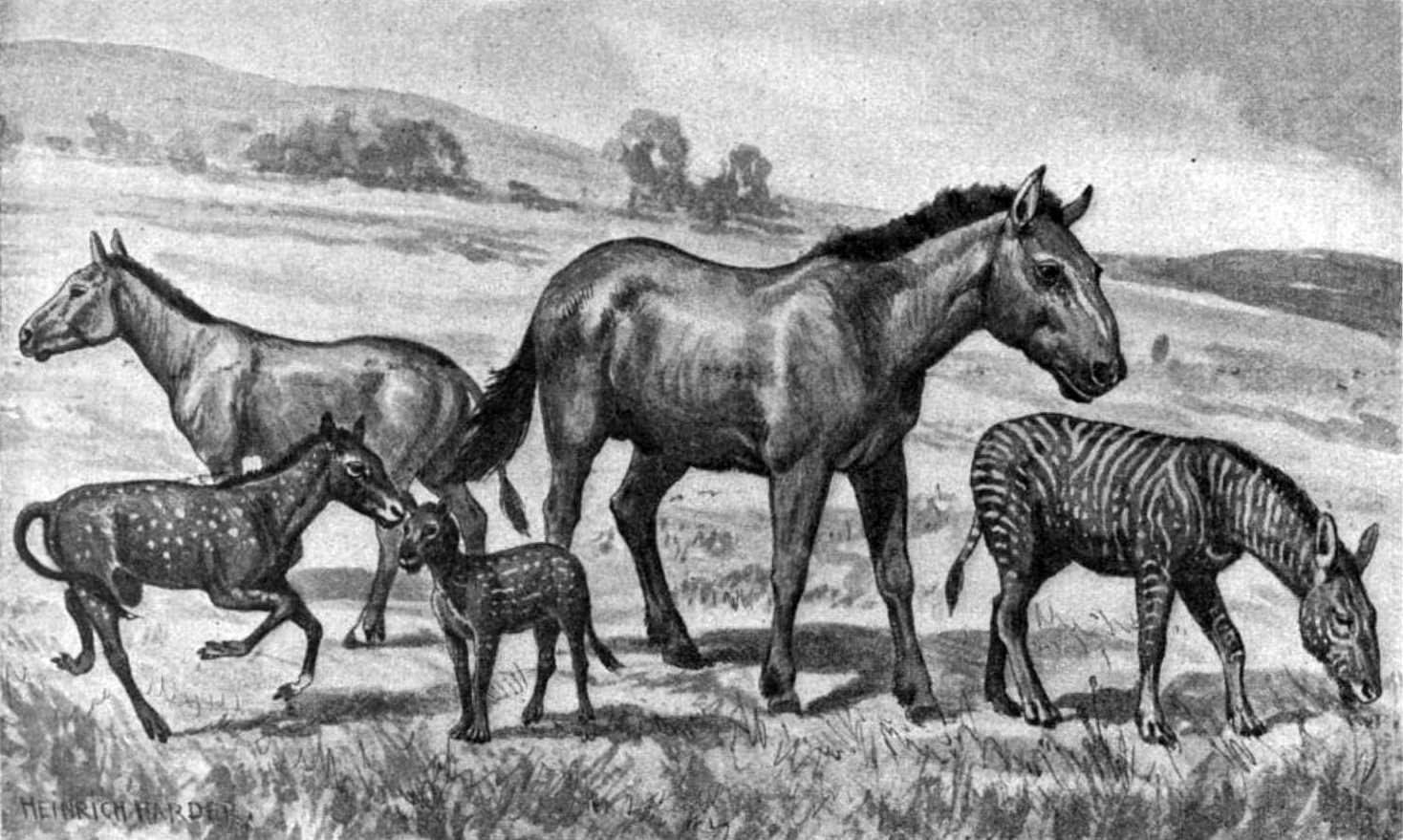

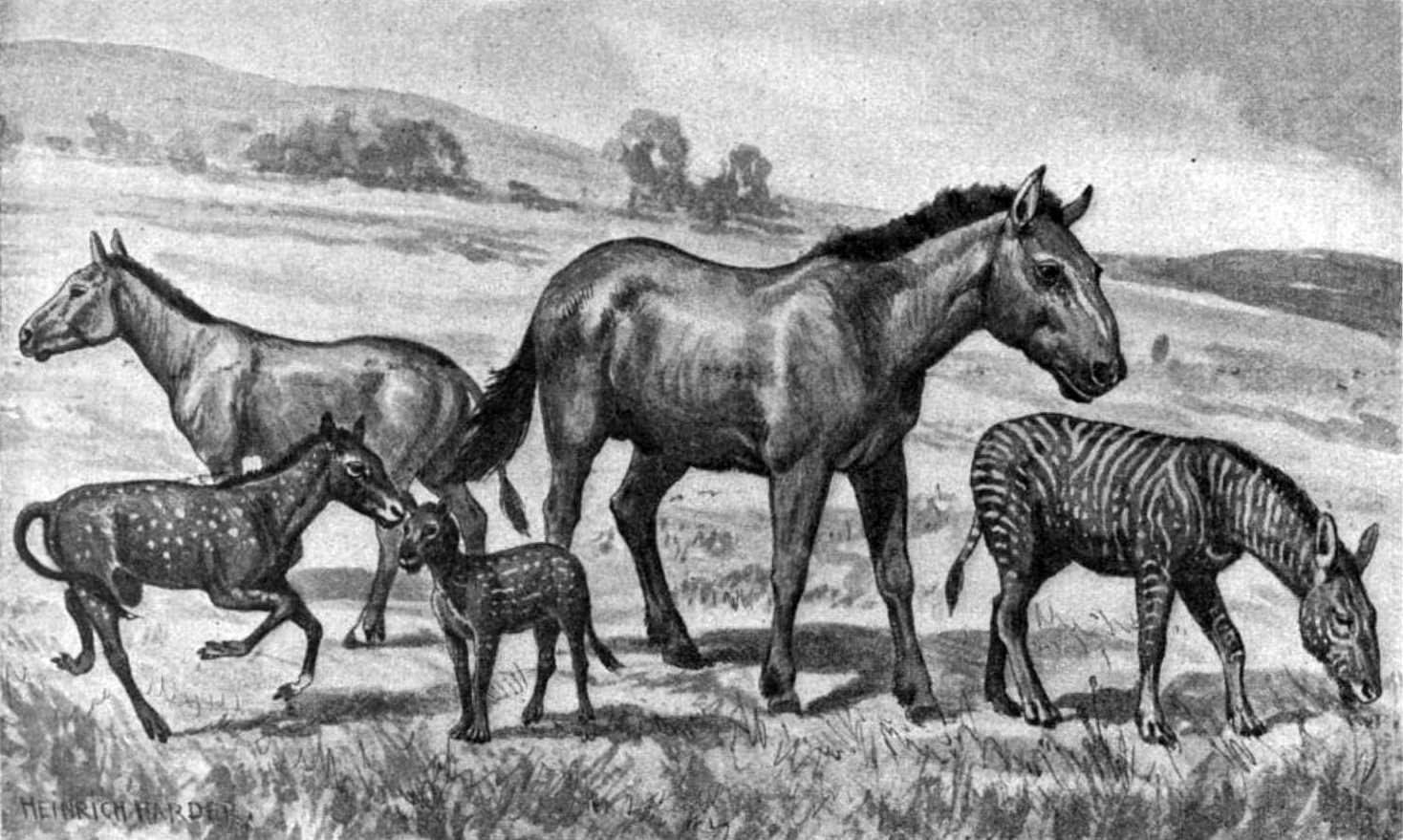

The evolution of the horse, a

The evolution of the horse, a

The original sequence of species believed to have evolved into the horse was based on fossils discovered in North America in 1879 by paleontologist

The original sequence of species believed to have evolved into the horse was based on fossils discovered in North America in 1879 by paleontologist

Its limbs were long relative to its body, already showing the beginnings of adaptations for running. However, all of the major leg bones were unfused, leaving the legs flexible and rotatable. Its wrist and hock joints were low to the ground. The forelimbs had developed five toes, of which four were equipped with small proto-hooves; the large fifth "toe-thumb" was off the ground. The hind limbs had small hooves on three out of the five toes, whereas the

Its limbs were long relative to its body, already showing the beginnings of adaptations for running. However, all of the major leg bones were unfused, leaving the legs flexible and rotatable. Its wrist and hock joints were low to the ground. The forelimbs had developed five toes, of which four were equipped with small proto-hooves; the large fifth "toe-thumb" was off the ground. The hind limbs had small hooves on three out of the five toes, whereas the

In response to the changing environment, the then-living species of Equidae also began to change. In the late Eocene, they began developing tougher teeth and becoming slightly larger and leggier, allowing for faster running speeds in open areas, and thus for evading predators in nonwooded areas. About 40 mya, ''

In response to the changing environment, the then-living species of Equidae also began to change. In the late Eocene, they began developing tougher teeth and becoming slightly larger and leggier, allowing for faster running speeds in open areas, and thus for evading predators in nonwooded areas. About 40 mya, ''

The forest-suited form was ''Kalobatippus'' (or ''Miohippus intermedius'', depending on whether it was a new genus or species), whose second and fourth front toes were long, well-suited to travel on the soft forest floors. ''Kalobatippus'' probably gave rise to ''

The forest-suited form was ''Kalobatippus'' (or ''Miohippus intermedius'', depending on whether it was a new genus or species), whose second and fourth front toes were long, well-suited to travel on the soft forest floors. ''Kalobatippus'' probably gave rise to ''

In the middle of the Miocene epoch, the grazer ''

In the middle of the Miocene epoch, the grazer ''

Three lineages within Equidae are believed to be descended from the numerous varieties of ''Merychippus'': ''

Three lineages within Equidae are believed to be descended from the numerous varieties of ''Merychippus'': ''

''

''

mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

of the family Equidae

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus'', ...

, occurred over a geologic time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochrono ...

of 50 million years, transforming the small, dog-sized, forest-dwelling ''Eohippus

''Eohippus'' is an extinct genus of small equid ungulates. The only species is ''E. angustidens'', which was long considered a species of ''Hyracotherium''. Its remains have been identified in North America and date to the Early Eocene (Ypresian ...

'' into the modern horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million y ...

. Paleozoologists have been able to piece together a more complete outline

Outline or outlining may refer to:

* Outline (list), a document summary, in hierarchical list format

* Code folding, a method of hiding or collapsing code or text to see content in outline form

* Outline drawing, a sketch depicting the outer edge ...

of the evolutionary lineage

Lineage may refer to:

Science

* Lineage (anthropology), a group that can demonstrate its common descent from an apical ancestor or a direct line of descent from an ancestor

* Lineage (evolution), a temporal sequence of individuals, populati ...

of the modern horse than of any other animal. Much of this evolution took place in North America, where horses originated but became extinct about 10,000 years ago.

The horse belongs to the order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulate

Odd-toed ungulates, mammals which constitute the taxonomic order Perissodactyla (, ), are animals—ungulates—who have reduced the weight-bearing toes to three (rhinoceroses and tapirs, with tapirs still using four toes on the front legs) ...

s), the members of which all share hooved feet and an odd number of toes on each foot, as well as mobile upper lip

The lips are the visible body part at the mouth of many animals, including humans. Lips are soft, movable, and serve as the opening for food intake and in the articulation of sound and speech. Human lips are a tactile sensory organ, and can be ...

s and a similar tooth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

structure. This means that horses share a common ancestry

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal com ...

with tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inhabit ...

s and rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct species o ...

es. The perissodactyls arose in the late Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), E ...

, less than 10 million years after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

. This group of animals appears to have been originally specialized for life in tropical forest

Tropical forests (a.k.a. jungle) are forested landscapes in tropical regions: ''i.e.'' land areas approximately bounded by the tropic of Cancer and Capricorn, but possibly affected by other factors such as prevailing winds.

Some tropical fores ...

s, but whereas tapirs and, to some extent, rhinoceroses, retained their jungle specializations, modern horses are adapted to life in the climatic conditions of the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslands, ...

s, which are drier and much harsher than forests or jungles. Other species of ''Equus'' are adapted to a variety of intermediate conditions.

The early ancestors of the modern horse walked on several spread-out toes, an accommodation to life spent walking on the soft, moist ground of primeval forests. As grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

species began to appear and flourish, the equid

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus'', w ...

s' diets shifted from foliage to silicate-rich grasses; the increased wear on teeth selected for increases in the size and durability of teeth. At the same time, as the steppes began to appear, selection favored increase in speed to outrun predators . This ability was attained by lengthening of limbs and the lifting of some toes from the ground in such a way that the weight of the body was gradually placed on one of the longest toes, the third.

History of research

Wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the endangered Przewalski's horse (''Equus ferus przewalskii''). The Europea ...

s have been known since prehistory from central Asia to Europe, with domestic horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a Domestication, domesticated, odd-toed ungulate, one-toed, ungulate, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two Extant taxon, extant subspecies of wild horse, ''Equus fer ...

s and other equids being distributed more widely in the Old World, but no horses or equids of any type were found in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

when European explorers reached the Americas. When the Spanish colonists brought domestic horses from Europe, beginning in 1493, escaped horses quickly established large feral herds. In the 1760s, the early naturalist Buffon suggested this was an indication of inferiority of the New World fauna, but later reconsidered this idea. William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

's 1807 expedition to Big Bone Lick

Big Bone Lick State Park is located at Big Bone in Boone County, Kentucky. The name of the park comes from the Pleistocene megafauna fossils found there. Mammoths are believed to have been drawn to this location by a salt lick deposited around t ...

found "leg and foot bones of the Horses", which were included with other fossils sent to Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and evaluated by the anatomist Caspar Wistar Caspar Wistar may refer to:

* Caspar Wistar (glassmaker) (1696–1752), Pennsylvania glassmaker and landowner

* Caspar Wistar (physician)

Caspar Wistar (September 13, 1761January 22, 1818) was an American physician and anatomist. He is sometim ...

, but neither commented on the significance of this find.

The first Old World equid fossil was found in the gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and drywall. ...

quarries in Montmartre

Montmartre ( , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Right Bank. The historic district established by the City of Paris in 1995 is bordered by Rue Ca ...

, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, in the 1820s. The tooth was sent to the Paris Conservatory

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

, where it was identified by Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

, who identified it as a browsing

Browsing is a kind of orienting strategy. It is supposed to identify something of relevance for the browsing organism. When used about human beings it is a metaphor taken from the animal kingdom. It is used, for example, about people browsing o ...

equine related to the tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inhabit ...

. His sketch of the entire animal matched later skeletons found at the site.

During the ''Beagle'' survey expedition, the young naturalist Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

had remarkable success with fossil hunting in Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

. On 10 October 1833, at Santa Fe, Argentina

Santa Fe de la Vera Cruz (; usually called just Santa Fe) is the capital city of the provinces of Argentina, province of Santa Fe Province, Santa Fe, Argentina. It is situated in north-eastern Argentina, near the junction of the Paraná River, ...

, he was "filled with astonishment" when he found a horse's tooth in the same stratum

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as ei ...

as fossil giant armadillo

Armadillos (meaning "little armored ones" in Spanish) are New World placental mammals in the order Cingulata. The Chlamyphoridae and Dasypodidae are the only surviving families in the order, which is part of the superorder Xenarthra, along wi ...

s, and wondered if it might have been washed down from a later layer, but concluded this was "not very probable". After the expedition returned in 1836, the anatomist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

confirmed the tooth was from an extinct species, which he subsequently named '' Equus curvidens'', and remarked, "This evidence of the former existence of a genus, which, as regards South America, had become extinct, and has a second time been introduced into that Continent, is not one of the least interesting fruits of Mr. Darwin's palæontological discoveries."

In 1848, a study ''On the fossil horses of America'' by Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later was a professor of natural history at Swarthmore ...

systematically examined Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

horse fossils from various collections, including that of the Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading natura ...

, and concluded at least two ancient horse species had existed in North America: ''Equus curvidens'' and another, which he named ''Equus americanus''. A decade later, however, he found the latter name had already been taken and renamed it '' Equus complicatus''. In the same year, he visited Europe and was introduced by Owen to Darwin.

The original sequence of species believed to have evolved into the horse was based on fossils discovered in North America in 1879 by paleontologist

The original sequence of species believed to have evolved into the horse was based on fossils discovered in North America in 1879 by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

. The sequence, from ''Eohippus'' to the modern horse (''Equus''), was popularized by Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

and became one of the most widely known examples of a clear evolutionary progression. The horse's evolutionary lineage became a common feature of biology textbooks, and the sequence of transitional fossil

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross a ...

s was assembled by the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

into an exhibit that emphasized the gradual, "straight-line" evolution of the horse.

Since then, as the number of equid fossils has increased, the actual evolutionary progression from ''Eohippus'' to ''Equus'' has been discovered to be much more complex and multibranched than was initially supposed. The straight, direct progression from the former to the latter has been replaced by a more elaborate model with numerous branches in different directions, of which the modern horse is only one of many. George Gaylord Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson (June 16, 1902 – October 6, 1984) was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the Modern synthesis (20th century), modern ...

in 1951 first recognized that the modern horse was not the "goal" of the entire lineage of equids, but is simply the only genus of the many horse lineages to survive.

Detailed fossil information on the distribution and rate of change of new equid species has also revealed that the progression between species was not as smooth and consistent as was once believed. Although some transitions, such as that of ''Dinohippus

''Dinohippus'' (Greek: "Terrible horse") is an extinct equid which was endemic to North America from the late Hemphillian stage of the Miocene through the Zanclean stage of the Pliocene (10.3—3.6 mya) and in existence for approximately . Foss ...

'' to ''Equus'', were indeed gradual progressions, a number of others, such as that of ''Epihippus

''Epihippus'' is an extinct genus of the modern horse family Equidae that lived in the Eocene, from 46 to 38 million years ago.

''Epihippus'' is believed to have evolved from '' Orohippus'', which continued the evolutionary trend of increasin ...

'' to ''Mesohippus

''Mesohippus'' (Greek: / meaning "middle" and / meaning "horse") is an extinct genus of early horse. It lived 37 to 32 million years ago in the Early Oligocene. Like many fossil horses, ''Mesohippus'' was common in North America. Its shoulder hei ...

'', were relatively abrupt in geologic time, taking place over only a few million years. Both anagenesis

Anagenesis is the gradual evolution of a species that continues to exist as an interbreeding population. This contrasts with cladogenesis, which occurs when there is branching or splitting, leading to two or more lineages and resulting in separate ...

(gradual change in an entire population's gene frequency) and cladogenesis

Cladogenesis is an evolutionary splitting of a parent species into two distinct species, forming a clade.

This event usually occurs when a few organisms end up in new, often distant areas or when environmental changes cause several extinctions, ...

(a population "splitting" into two distinct evolutionary branches) occurred, and many species coexisted with "ancestor" species at various times. The change in equids' traits was also not always a "straight line" from ''Eohippus'' to ''Equus'': some traits reversed themselves at various points in the evolution of new equid species, such as size and the presence of facial '' fossae'', and only in retrospect can certain evolutionary trends be recognized.

Before odd-toed ungulates

Phenacodontidae

Phenacodontidae

Phenacodontidae is an extinct family (biology), family of large herbivorous mammals traditionally placed in the “wastebasket taxon” Condylarthra, which may instead represent early-stage Perissodactyla, perissodactyls. They lived in the Paleo ...

is the most recent family in the order Condylarthra

Condylarthra is an informal group – previously considered an order – of extinct placental mammals, known primarily from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. They are considered early, primitive ungulates. It is now largely considered to be a wast ...

believed to be the ancestral to the odd-toed ungulates

Odd-toed ungulates, mammals which constitute the taxonomic order Perissodactyla (, ), are animals—ungulates—who have reduced the weight-bearing toes to three (rhinoceroses and tapirs, with tapirs still using four toes on the front legs) ...

. It contains the genera ''Almogaver

''Almogaver'' is an extinct possible odd-toed ungulate genus in the family Phenacodontidae. It was a ground-dwelling herbivore. It is known from the Tremp Basin in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat ...

'', ''Copecion

''Copecion'' was a genus of early herbivorous mammals that was part of the family Phenacodontidae

Phenacodontidae is an extinct family of large herbivorous mammals traditionally placed in the “wastebasket taxon” Condylarthra, which may ins ...

'', ''Ectocion

''Ectocion'' (sometimes ''Ectocyon'') is an extinct genus of placental mammals of the family Phenacodontidae. The genus was earlier classified as ''Gidleyina'' (Simpson 1935) and ''Prosthecion'' (Patterson and West 1973). Retrieved May 2013.

Pa ...

'', '' Eodesmatodon'', '' Meniscotherium'', '' Ordathspidotherium'', ''Phenacodus

''Phenacodus'' (Greek: "deception" (phenax), "tooth' (odus)) is an extinct genus of mammals from the late Paleocene through middle Eocene, about 55 million years ago. It is one of the earliest and most primitive of the ungulates, typifying the fa ...

'' and ''Pleuraspidotherium

''Pleuraspidotherium'' is an extinct genus of condylarth of the family Pleuraspidotheriidae, whose fossils have been found in the Late Paleocene Marnes de Montchenot of France and the Tremp Formation of modern Spain

, image_flag ...

''. The family lived from the Early Paleocene

The Danian is the oldest age or lowest stage of the Paleocene Epoch or Series, of the Paleogene Period or System, and of the Cenozoic Era or Erathem. The beginning of the Danian (and the end of the preceding Maastrichtian) is at the Cretaceo ...

to the Middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', "dawn ...

in Europe and were about the size of a sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

, with tail

The tail is the section at the rear end of certain kinds of animals’ bodies; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage to the torso. It is the part of the body that corresponds roughly to the sacrum and coccyx in mammals, r ...

s making slightly less than half of the length of their bodies and unlike their ancestors, good running skills.

Eocene and Oligocene: early equids

''Eohippus''

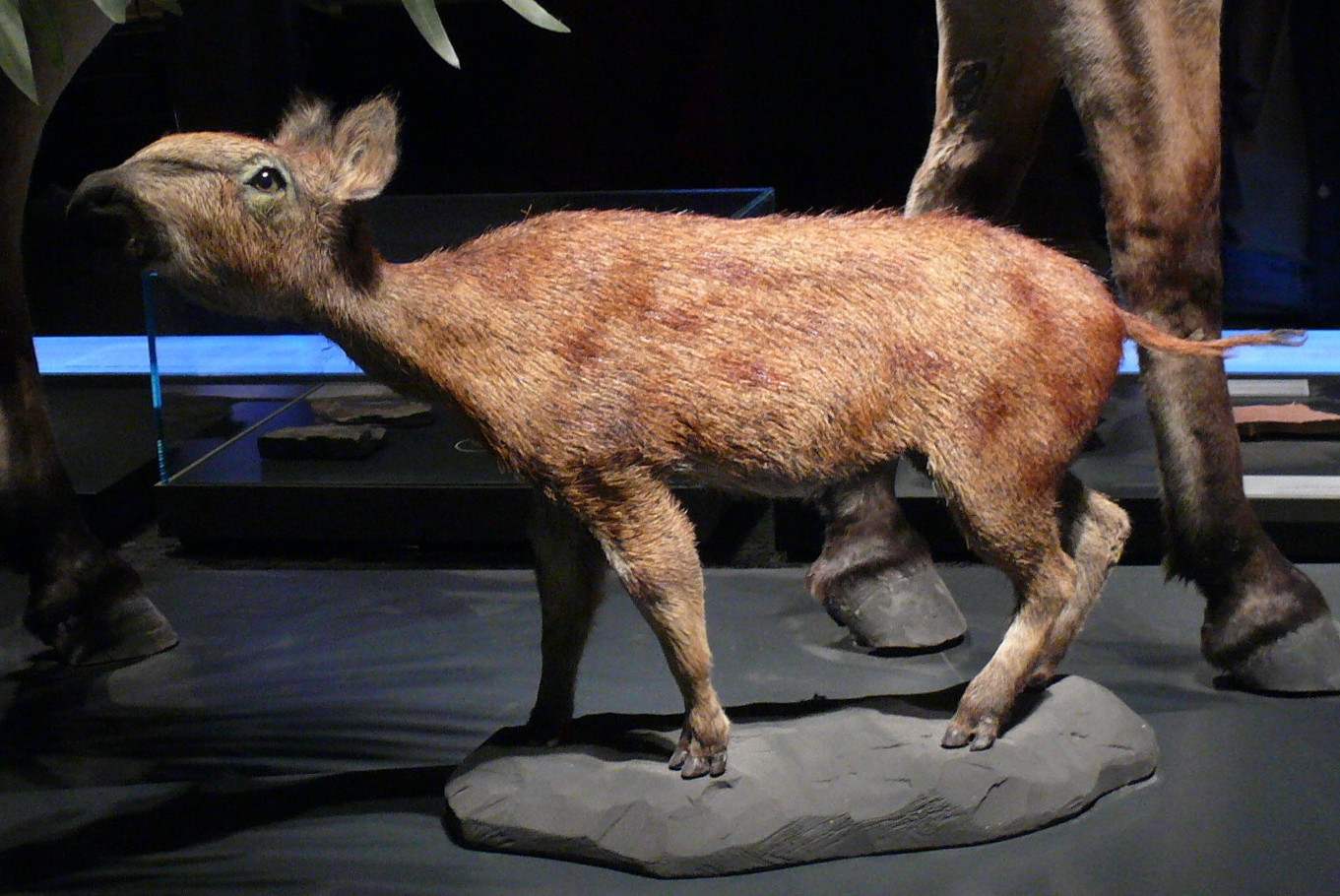

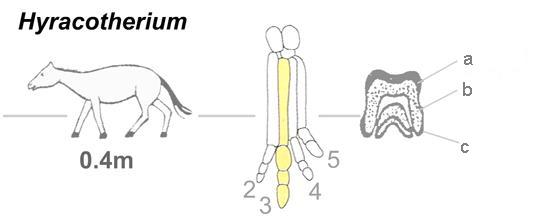

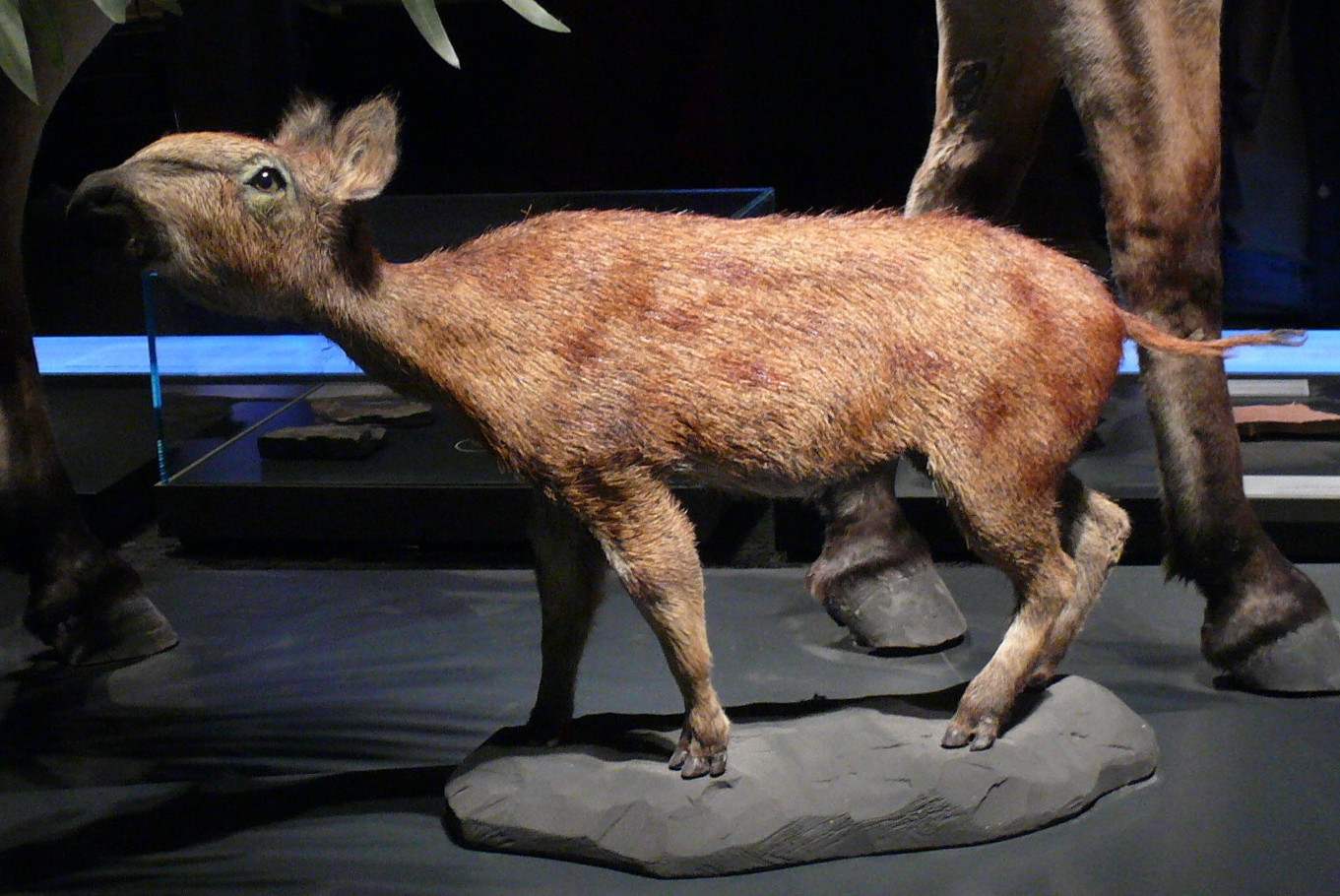

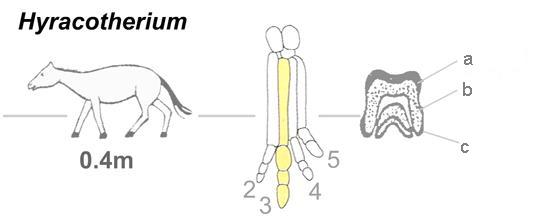

''Eohippus'' appeared in theYpresian

In the geologic timescale the Ypresian is the oldest age (geology), age or lowest stage (stratigraphy), stratigraphic stage of the Eocene. It spans the time between , is preceded by the Thanetian Age (part of the Paleocene) and is followed by th ...

(early Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

), about 52 mya (million years ago). It was an animal approximately the size of a fox (250–450 mm in height), with a relatively short head and neck and a springy, arched back. It had 44 low-crowned teeth, in the typical arrangement of an omnivorous, browsing mammal: three incisors, one canine, four premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

s, and three molars on each side of the jaw. Its molars were uneven, dull, and bumpy, and used primarily for grinding foliage. The cusps of the molars were slightly connected in low crests. ''Eohippus'' browsed on soft foliage and fruit, probably scampering between thickets in the mode of a modern muntjac

Muntjacs ( ), also known as the barking deer or rib-faced deer, (URL is Google Books) are small deer of the genus ''Muntiacus'' native to South Asia and Southeast Asia. Muntjacs are thought to have begun appearing 15–35 million years ago, ...

. It had a small brain, and possessed especially small frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove betwe ...

s.

Its limbs were long relative to its body, already showing the beginnings of adaptations for running. However, all of the major leg bones were unfused, leaving the legs flexible and rotatable. Its wrist and hock joints were low to the ground. The forelimbs had developed five toes, of which four were equipped with small proto-hooves; the large fifth "toe-thumb" was off the ground. The hind limbs had small hooves on three out of the five toes, whereas the

Its limbs were long relative to its body, already showing the beginnings of adaptations for running. However, all of the major leg bones were unfused, leaving the legs flexible and rotatable. Its wrist and hock joints were low to the ground. The forelimbs had developed five toes, of which four were equipped with small proto-hooves; the large fifth "toe-thumb" was off the ground. The hind limbs had small hooves on three out of the five toes, whereas the vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

first and fifth toes did not touch the ground. Its feet were padded, much like a dog's, but with the small hooves in place of claws.

For a span of about 20 million years, ''Eohippus'' thrived with few significant evolutionary changes. The most significant change was in the teeth, which began to adapt to its changing diet, as these early Equidae

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus'', ...

shifted from a mixed diet of fruits and foliage to one focused increasingly on browsing foods. During the Eocene, an ''Eohippus'' species (most likely ''Eohippus angustidens'') branched out into various new types of Equidae. Thousands of complete, fossilized skeletons of these animals have been found in the Eocene layers of North American strata, mainly in the Wind River basin in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. Similar fossils have also been discovered in Europe, such as ''Propalaeotherium

''Propalaeotherium'' was an early genus of perissodactyl endemic to Europe and Asia during the early Eocene. There are currently six recognised species within the genus, with ''P. isselanum'' as the type species (named by Georges Cuvier in 1824 ...

'' (which is not considered ancestral to the modern horse).

''Orohippus''

Approximately 50 million years ago, in the early-to-middleEocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

, ''Eohippus'' smoothly transitioned into ''Orohippus'' through a gradual series of changes. Although its name means "mountain horse", ''Orohippus'' was not a true horse and did not live in the mountains. It resembled ''Eohippus'' in size, but had a slimmer body, an elongated head, slimmer forelimbs, and longer hind legs, all of which are characteristics of a good jumper. Although ''Orohippus'' was still pad-footed, the vestigial outer toes of ''Eohippus'' were not present in ''Orohippus''; there were four toes on each fore leg, and three on each hind leg.

The most dramatic change between ''Eohippus'' and ''Orohippus'' was in the teeth: the first of the premolar teeth was dwarfed, the last premolar shifted in shape and function into a molar, and the crests on the teeth became more pronounced. Both of these factors increased the grinding ability of the teeth of ''Orohippus''; the change suggest selection imposed by increased toughness of ''Orohippus'' plant diet.

''Epihippus''

In the mid-Eocene, about 47 million years ago, ''Epihippus'', a genus which continued the evolutionary trend of increasingly efficient grinding teeth, evolved from ''Orohippus''. ''Epihippus'' had five grinding, low-crowned cheek teeth with well-formed crests. A late species of ''Epihippus'', sometimes referred to as '' Duchesnehippus intermedius'', had teeth similar toOligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

equids, although slightly less developed. Whether ''Duchesnehippus'' was a subgenus of ''Epihippus'' or a distinct genus is disputed. ''Epihippus'' was only 2 feet tall.

''Mesohippus''

In the late Eocene and the early stages of theOligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

epoch (32–24 mya), the climate of North America became drier, and the earliest grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

es began to evolve. The forests were yielding to flatlands, home to grasses and various kinds of brush. In a few areas, these plains were covered in sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class of s ...

, creating the type of environment resembling the present-day prairie

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

s. In response to the changing environment, the then-living species of Equidae also began to change. In the late Eocene, they began developing tougher teeth and becoming slightly larger and leggier, allowing for faster running speeds in open areas, and thus for evading predators in nonwooded areas. About 40 mya, ''

In response to the changing environment, the then-living species of Equidae also began to change. In the late Eocene, they began developing tougher teeth and becoming slightly larger and leggier, allowing for faster running speeds in open areas, and thus for evading predators in nonwooded areas. About 40 mya, ''Mesohippus

''Mesohippus'' (Greek: / meaning "middle" and / meaning "horse") is an extinct genus of early horse. It lived 37 to 32 million years ago in the Early Oligocene. Like many fossil horses, ''Mesohippus'' was common in North America. Its shoulder hei ...

'' ("middle horse") suddenly developed in response to strong new selective pressures to adapt, beginning with the species ''Mesohippus celer'' and soon followed by ''Mesohippus westoni''.

In the early Oligocene, ''Mesohippus'' was one of the more widespread mammals in North America. It walked on three toes on each of its front and hind feet (the first and fifth toes remained, but were small and not used in walking). The third toe was stronger than the outer ones, and thus more weighted; the fourth front toe was diminished to a vestigial nub. Judging by its longer and slimmer limbs, ''Mesohippus'' was an agile animal.

''Mesohippus'' was slightly larger than ''Epihippus'', about 610 mm (24 in) at the shoulder. Its back was less arched, and its face, snout, and neck were somewhat longer. It had significantly larger cerebral hemisphere

The vertebrate cerebrum (brain) is formed by two cerebral hemispheres that are separated by a groove, the longitudinal fissure. The brain can thus be described as being divided into left and right cerebral hemispheres. Each of these hemispheres ...

s, and had a small, shallow depression on its skull called a fossa, which in modern horses is quite detailed. The fossa serves as a useful marker for identifying an equine fossil's species. ''Mesohippus'' had six grinding "cheek teeth", with a single premolar in front—a trait all descendant Equidae would retain. ''Mesohippus'' also had the sharp tooth crests of ''Epihippus'', improving its ability to grind down tough vegetation.

''Miohippus''

Around 36 million years ago, soon after the development of ''Mesohippus'', ''Miohippus

''Miohippus'' (meaning "small horse") was a genus of prehistoric horse existing longer than most Equidae. ''Miohippus'' lived in what is now North America from 32 to 25 million years ago, during the late Eocene to late Oligocene. ''Miohippus'' ...

'' ("lesser horse") emerged, the earliest species being ''Miohippus assiniboiensis''. As with ''Mesohippus'', the appearance of ''Miohippus'' was relatively abrupt, though a few transitional fossils linking the two genera have been found. ''Mesohippus'' was once believed to have anagenetically evolved into ''Miohippus'' by a gradual series of progressions, but new evidence has shown its evolution was cladogenetic: a ''Miohippus'' population split off from the main genus ''Mesohippus'', coexisted with ''Mesohippus'' for around four million years, and then over time came to replace ''Mesohippus''.

''Miohippus'' was significantly larger than its predecessors, and its ankle joints had subtly changed. Its facial fossa was larger and deeper, and it also began to show a variable extra crest in its upper cheek teeth, a trait that became a characteristic feature of equine teeth.

''Miohippus'' ushered in a major new period of diversification in Equidae.''Fossil Horses In Cyberspace''Florida Museum of Natural History

The Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH) is Florida's official state-sponsored and chartered natural-history museum. Its main facilities are located at 3215 Hull Road on the campus of the University of Florida in Gainesville.

The main pub ...

and the National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National I ...

.

Miocene and Pliocene: true equines

''Kalobatippus''

The forest-suited form was ''Kalobatippus'' (or ''Miohippus intermedius'', depending on whether it was a new genus or species), whose second and fourth front toes were long, well-suited to travel on the soft forest floors. ''Kalobatippus'' probably gave rise to ''

The forest-suited form was ''Kalobatippus'' (or ''Miohippus intermedius'', depending on whether it was a new genus or species), whose second and fourth front toes were long, well-suited to travel on the soft forest floors. ''Kalobatippus'' probably gave rise to ''Anchitherium

''Anchitherium'' (meaning ''near beast'') was a fossil horse with a three- toed hoof.

''Anchitherium'' was a browsing (leaf eating) horse that originated in the early Miocene of North America and subsequently dispersed to Europe and Asia,(in C ...

'', which travelled to Asia via the Bering Strait land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and Colonisation (biology), colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regre ...

, and from there to Europe. In both North America and Eurasia, larger-bodied genera evolved from ''Anchitherium'': ''Sinohippus

''Sinohippus'' ("Chinese horse") is an extinct equid genus belonging to the subfamily Anchitheriinae

The Anchitheriinae are an extinct subfamily of the Perissodactyla family Equidae, the same family which includes modern horses, zebras and ...

'' in Eurasia and ''Hypohippus

''Hypohippus'' (Greek: "under" (hypos), "horse" (hippos)) is an extinct genus of three-toed horse, which lived 17–11 million years ago. It was the largest anchitherine equid about the size of a modern domestic horse, at and long. It was a lo ...

'' and ''Megahippus

''Megahippus'' (Greek: "great" (mega), "horse" (hippos)) is an extinct equid genus belonging to the subfamily Anchitheriinae. As with other members of this subfamily, ''Megahippus'' is more primitive than the living horses. It was very large memb ...

'' in North America. ''Hypohippus'' became extinct by the late Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

.

''Parahippus''

The ''Miohippus'' population that remained on the steppes is believed to be ancestral to ''Parahippus

''Parahippus'' ("near to horse"), is an extinct equid, a relative of modern horses, Donkey, asses and zebras. It lived from 24 to 17 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch. It was very similar to ''Miohippus'', but slightly larger, at around ...

'', a North American animal about the size of a small pony

A pony is a type of small horse ('' Equus ferus caballus''). Depending on the context, a pony may be a horse that is under an approximate or exact height at the withers, or a small horse with a specific conformation and temperament. Compared ...

, with a prolonged skull and a facial structure resembling the horses of today. Its third toe was stronger and larger, and carried the main weight of the body. Its four premolars resembled the molar teeth; the first were small and almost nonexistent. The incisor teeth, like those of its predecessors, had a crown (like human incisors); however, the top incisors had a trace of a shallow crease marking the beginning of the core/cup.

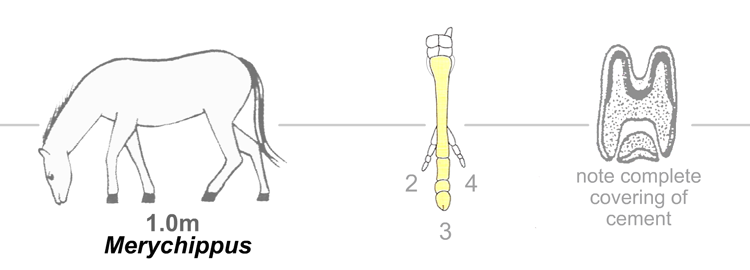

''Merychippus''

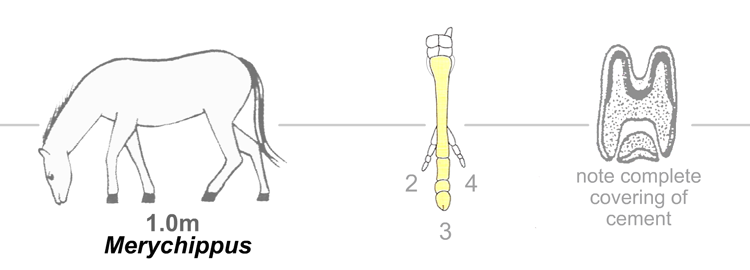

In the middle of the Miocene epoch, the grazer ''

In the middle of the Miocene epoch, the grazer ''Merychippus

''Merychippus'' is an extinct proto-horse of the family Equidae that was endemic to North America during the Miocene, 15.97–5.33 million years ago. It had three toes on each foot and is the first horse known to have grazed.

Discovery and nami ...

'' flourished. It had wider molars than its predecessors, which are believed to have been used for crunching the hard grasses of the steppes. The hind legs, which were relatively short, had side toes equipped with small hooves, but they probably only touched the ground when running. ''Merychippus'' radiated into at least 19 additional grassland species.

''Hipparion''

Three lineages within Equidae are believed to be descended from the numerous varieties of ''Merychippus'': ''

Three lineages within Equidae are believed to be descended from the numerous varieties of ''Merychippus'': ''Hipparion

''Hipparion'' (Greek, "pony") is an extinct genus of horse that lived in North America, Asia, Europe, and Africa during the Miocene through Pleistocene ~23 Mya—781,000 years ago. It lived in non-forested, grassy plains, shortgrass prairie or ...

'', ''Protohippus

''Protohippus'' is an extinct three-toed genus of horse. It was roughly the size of a modern donkey. Fossil evidence suggests that it lived during the Late Miocene (Clarendonian to Hemphillian), from about 13.6 Ma to 5.3 Ma.

Analysis of ''Proto ...

'' and ''Pliohippus

''Pliohippus'' (Greek (, "more") and (, "horse")) is an extinction, extinct genus of Equidae, the "horse family". ''Pliohippus'' arose in the middle Miocene, around 15 million years ago. The long and slim limbs of ''Pliohippus'' reveal a quick- ...

''. The most different from ''Merychippus'' was ''Hipparion'', mainly in the structure of tooth enamel

Tooth enamel is one of the four major Tissue (biology), tissues that make up the tooth in humans and many other animals, including some species of fish. It makes up the normally visible part of the tooth, covering the Crown (tooth), crown. The ...

: in comparison with other Equidae, the inside, or tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ (anatomy), organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive system, digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surfa ...

side, had a completely isolated parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). Whe ...

. A complete and well-preserved skeleton of the North American ''Hipparion'' shows an animal the size of a small pony. They were very slim, rather like antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mammals ...

s, and were adapted to life on dry prairies. On its slim legs, ''Hipparion'' had three toes equipped with small hooves, but the side toes did not touch the ground.

In North America, ''Hipparion'' and its relatives (''Cormohipparion

''Cormohipparion'' is an extinct genus of horse belonging to the tribe Hipparionini that lived in North America during the late Miocene to Pliocene ( Hemphillian to Blancan in the NALMA classification). This ancient species of horse grew up to l ...

'', ''Nannippus

''Nannippus'' is an extinct genus of three-toed horse endemic to North America during the Miocene through Pleistoceneabout 13.3—1.8 million years ago (Mya), living around 11.5 million years. This ancient species of three-toed horse grew up to 3 ...

'', ''Neohipparion

''Neohipparion'' (Greek: "new" (neos), "pony" (hipparion)) is an extinct genus of equid, from the Neogene (Miocene to Pliocene) of North America and Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Ameri ...

'', and ''Pseudhipparion

''Pseudhipparion'' is an extinct genus of three-toed horse endemic to North America during the Miocene. They were herding animals whose diet consisted of C3 plants. Fossils found in Georgia and Florida

Florida is a state located in the ...

''), proliferated into many kinds of equid

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus'', w ...

s, at least one of which managed to migrate to Asia and Europe during the Miocene epoch. (European ''Hipparion'' differs from American ''Hipparion'' in its smaller body size – the best-known discovery of these fossils was near Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

.)

''Pliohippus''

''

''Pliohippus

''Pliohippus'' (Greek (, "more") and (, "horse")) is an extinction, extinct genus of Equidae, the "horse family". ''Pliohippus'' arose in the middle Miocene, around 15 million years ago. The long and slim limbs of ''Pliohippus'' reveal a quick- ...

'' arose from ''Callippus'' in the middle Miocene, around 12 mya. It was very similar in appearance to '' Equus'', though it had two long extra toes on both sides of the hoof, externally barely visible as callused stubs. The long and slim limbs of ''Pliohippus'' reveal a quick-footed steppe animal.

Until recently, ''Pliohippus'' was believed to be the ancestor of present-day horses because of its many anatomical similarities. However, though ''Pliohippus'' was clearly a close relative of ''Equus'', its skull had deep facial fossae, whereas ''Equus'' had no fossae at all. Additionally, its teeth were strongly curved, unlike the very straight teeth of modern horses. Consequently, it is unlikely to be the ancestor of the modern horse; instead, it is a likely candidate for the ancestor of ''Astrohippus

''Astrohippus'' ("Star horse") is an extinct member of the Equidae Tribe (biology), tribe Equini, the same tribe that contains the only living equid genus, ''Equus (genus), Equus''. Fossil remains have been found in the central United States, Flo ...

''.

''Dinohippus''

''Dinohippus

''Dinohippus'' (Greek: "Terrible horse") is an extinct equid which was endemic to North America from the late Hemphillian stage of the Miocene through the Zanclean stage of the Pliocene (10.3—3.6 mya) and in existence for approximately . Foss ...

'' was the most common species of Equidae in North America during the late Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58

''

The genus ''Equus'', which includes all extant equines, is believed to have evolved from ''

The genus ''Equus'', which includes all extant equines, is believed to have evolved from ''

The ancestral coat color of ''E. ferus'' was possibly a uniform

The ancestral coat color of ''E. ferus'' was possibly a uniform

Plesippus

''Plesippus'' is a genus of extinct horse from the Pleistocene of North America. Although commonly seen as a subgenus of ''Equus'' recent cladistic analysis considers it a distinct genus.

Species

Two species are recognized by Barron et al. (201 ...

'' is often considered an intermediate stage between ''Dinohippus'' and the extant genus, ''Equus''.

The famous fossils found near Hagerman, Idaho were originally thought to be a part of the genus ''Plesippus''. Hagerman Fossil Beds (Idaho) is a Pliocene site, dating to about 3.5 mya. The fossilized remains were originally called ''Plesippus shoshonensis'', but further study by paleontologists determined the fossils represented the oldest remains of the genus ''Equus''. Their estimated average weight was 425 kg, roughly the size of an Arabian horse

The Arabian or Arab horse ( ar, الحصان العربي , DIN 31635, DMG ''ḥiṣān ʿarabī'') is a horse breed, breed of horse that originated on the Arabian Peninsula. With a distinctive head shape and high tail carriage, the Arabian is ...

.

At the end of the Pliocene, the climate in North America began to cool significantly and most of the animals were forced to move south. One population of ''Plesippus'' moved across the Bering land bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of ...

into Eurasia around 2.5 mya.

Modern horses

''Equus''

Dinohippus

''Dinohippus'' (Greek: "Terrible horse") is an extinct equid which was endemic to North America from the late Hemphillian stage of the Miocene through the Zanclean stage of the Pliocene (10.3—3.6 mya) and in existence for approximately . Foss ...

'', via the intermediate form ''Plesippus

''Plesippus'' is a genus of extinct horse from the Pleistocene of North America. Although commonly seen as a subgenus of ''Equus'' recent cladistic analysis considers it a distinct genus.

Species

Two species are recognized by Barron et al. (201 ...

''. One of the oldest species is ''Equus simplicidens

The Hagerman horse (''Equus simplicidens''), also called the Hagerman zebra or the American zebra, was a North American species of equid from the Pliocene epoch and the Pleistocene epoch. It was one of the oldest horses of the genus ''Equus'' and ...

'', described as zebra-like with a donkey-shaped head. The oldest fossil to date is ~3.5 million years old, discovered in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

. The genus appears to have spread quickly into the Old World, with the similarly aged '' Equus livenzovensis'' documented from western Europe and Russia.

Molecular phylogenies indicate the most recent common ancestor of all modern equids (members of the genus ''Equus'') lived ~5.6 (3.9–7.8) mya. Direct paleogenomic sequencing of a 700,000-year-old middle Pleistocene horse metapodial bone from Canada implies a more recent 4.07 Myr before present date for the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) within the range of 4.0 to 4.5 Myr BP. The oldest divergencies are the Asian hemiones (subgenus ''E. (Asinus

''Asinus'' is a subgenus of '' Equus'' (single-toed (hooved) grazing animal) that encompasses several subspecies of the Equidae commonly known as wild asses, characterized by long ears, a lean, straight-backed build, lack of a true withers, a ...

)'', including the kulan, onager

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

, and kiang

The kiang (''Equus kiang'') is the largest of the '' Asinus'' subgenus. It is native to the Tibetan Plateau, where it inhabits montane and alpine grasslands. Its current range is restricted to the plains of the Tibetan plateau; Ladakh; and nort ...

), followed by the African zebras (subgenera ''E. ( Dolichohippus)'', and ''E. (Hippotigris

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: the Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. zeb ...

)''). All other modern forms including the domesticated horse (and many fossil Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

forms) belong to the subgenus ''E. ( Equus)'' which diverged ~4.8 (3.2–6.5) million years ago.

Pleistocene horse fossils have been assigned to a multitude of species, with over 50 species of equines described from the Pleistocene of North America alone, although the taxonomic validity of most of these has been called into question. Recent genetic work on fossils has found evidence for only three genetically divergent equid lineages in Pleistocene North and South America. These results suggest all North American fossils of caballine-type horses (which also include the domesticated horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

and Przewalski's horse

Przewalski's horse (, , (Пржевальский ), ) (''Equus ferus przewalskii'' or ''Equus przewalskii''), also called the takhi, Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered horse originally native to the steppes of Ce ...

of Europe and Asia), as well as South American fossils traditionally placed in the subgenus ''E. (Amerhippus)'' belong to the same species: '' E. ferus''. Remains attributed to a variety of species and lumped as New World stilt-legged horses (including Haringtonhippus

''Haringtonhippus'' is an extinct genus of stilt-legged equine from the Pleistocene of North America The genus is monospecific, consisting of the species ''H. francisci'', initially described in 1915 by Oliver Perry Hay as ''Equus francisci''. Pr ...

, ''E. tau'', ''E. quinni'' and potentially North American Pleistocene fossils previously attributed to ''E. cf. hemiones'', and ''E. (Asinus)'' cf. ''kiang'') probably all belong to a second species endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

to North America, which despite a superficial resemblance to species in the subgenus ''E. (Asinus)'' (and hence occasionally referred to as North American ass) is closely related to ''E. ferus''. Surprisingly, the third species, endemic to South America and traditionally referred to as ''Hippidion

''Hippidion'' (meaning ''little horse'') is an extinct genus of equine that lived in South America from the Late Pliocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene ( Lujanian), between two million and 11,000 years ago. They were one of two lineages of e ...

'', originally believed to be descended from ''Pliohippus'', was shown to be a third species in the genus ''Equus'', closely related to the New World stilt-legged horse. The temporal and regional variation in body size and morphological features within each lineage indicates extraordinary intraspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organ ...

plasticity. Such environment-driven adaptative changes would explain why the taxonomic diversity of Pleistocene equids has been overestimated on morphoanatomical grounds.

According to these results, it appears the genus ''Equus'' evolved from a ''Dinohippus''-like ancestor ~4–7 mya. It rapidly spread into the Old World and there diversified into the various species of asses and zebras. A North American lineage of the subgenus ''E. (Equus)'' evolved into the New World stilt-legged horse (NWSLH). Subsequently, populations of this species entered South America as part of the Great American Interchange

The Great American Biotic Interchange (commonly abbreviated as GABI), also known as the Great American Interchange and the Great American Faunal Interchange, was an important late Cenozoic paleozoogeographic biotic interchange event in which lan ...

shortly after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

, and evolved into the form currently referred to as ''Hippidion'' ~2.5 million years ago. ''Hippidion'' is thus only distantly related to the morphologically similar ''Pliohippus

''Pliohippus'' (Greek (, "more") and (, "horse")) is an extinction, extinct genus of Equidae, the "horse family". ''Pliohippus'' arose in the middle Miocene, around 15 million years ago. The long and slim limbs of ''Pliohippus'' reveal a quick- ...

'', which presumably became extinct during the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

. Both the NWSLH and ''Hippidium'' show adaptations to dry, barren ground, whereas the shortened legs of ''Hippidion'' may have been a response to sloped terrain. In contrast, the geographic origin of the closely related modern ''E. ferus'' is not resolved. However, genetic results on extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

and fossil material of Pleistocene age indicate two clades, potentially subspecies, one of which had a holarctic

The Holarctic realm is a biogeographic realm that comprises the majority of habitats found throughout the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. It corresponds to the floristic Boreal Kingdom. It includes both the Nearctic zoogeographical region ...

distribution spanning from Europe through Asia and across North America and would become the founding stock of the modern domesticated horse. The other population appears to have been restricted to North America. However, one or more North American populations of ''E. ferus'' entered South America ~1.0–1.5 million years ago, leading to the forms currently known as ''E. (Amerhippus)'', which represent an extinct geographic variant or race of ''E. ferus''.

Genome sequencing

Early sequencing studies of DNA revealed several genetic characteristics of Przewalski's horse that differ from what is seen in modern domestic horses, indicating neither is ancestor of the other, and supporting the status of Przewalski horses as a remnant wild population not derived from domestic horses. The evolutionarydivergence

In vector calculus, divergence is a vector operator that operates on a vector field, producing a scalar field giving the quantity of the vector field's source at each point. More technically, the divergence represents the volume density of the ...

of the two populations was estimated to have occurred about 45,000 YBP

Before Present (BP) years, or "years before present", is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Becau ...

, while the archaeological record places the first horse domestication about 5,500 YBP by the ancient central-Asian Botai culture

The Botai culture is an archaeological culture (c. 3700–3100 BC) of prehistoric northern Central Asia. It was named after the settlement of Botai in today's northern Kazakhstan. The Botai culture has two other large sites: Krasnyi ...

. The two lineages thus split well before domestication, probably due to climate, topography, or other environmental changes.

Several subsequent DNA studies produced partially contradictory results. A 2009 molecular analysis using ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient specimens. Due to degradation processes (including cross-linking, deamination and fragmentation) ancient DNA is more degraded in comparison with contemporary genetic material. Even under the bes ...

recovered from archaeological sites placed Przewalski's horse in the middle of the domesticated horses, but a 2011 mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

analysis suggested that Przewalski's and modern domestic horses diverged some 160,000 years ago.O A Ryder, A R Fisher, B Schultz, S Kosakovsky Pond, A Nekrutenko, K D Makova. "A massively parallel sequencing approach uncovers ancient origins and high genetic variability of endangered Przewalski's horses". Genome Biology and Evolution. 2011 An analysis based on whole genome sequencing and calibration with DNA from old horse bones gave a divergence date of 38–72 thousand years ago.

In June 2013, a group of researchers announced that they had sequenced the DNA of a 560–780 thousand year old horse, using material extracted from a leg bone found buried in permafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

in Canada's Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

territory. Before this publication, the oldest nuclear genome that had been successfully sequenced was dated at 110–130 thousand years ago. For comparison, the researchers also sequenced

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which suc ...

the genomes of a 43,000-year-old Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

horse, a Przewalski's horse

Przewalski's horse (, , (Пржевальский ), ) (''Equus ferus przewalskii'' or ''Equus przewalskii''), also called the takhi, Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered horse originally native to the steppes of Ce ...

, five modern horse breeds, and a donkey. Analysis of differences between these genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s indicated that the last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

of modern horses, donkeys, and zebras existed 4 to 4.5 million years ago. The results also indicated that Przewalski's horse diverged from other modern types of horse about 43,000 years ago, and had never in its evolutionary history been domesticated.

A new analysis in 2018 involved genomic sequencing of ancient DNA from mid-fourth-millennium B.C.E. Botai domestic horses, as well as domestic horses from more recent archaeological sites, and comparison of these genomes with those of modern domestic and Przewalski's horses. The study revealed that Przewalski's horses not only belong to the same genetic lineage as those from the Botai culture, but were the feral

A feral () animal or plant is one that lives in the wild but is descended from domesticated individuals. As with an introduced species, the introduction of feral animals or plants to non-native regions may disrupt ecosystems and has, in some ...

descendants of these ancient domestic animals, rather than representing a surviving population of never-domesticated horses. The Botai horses were found to have made only negligible genetic contribution to any of the other ancient or modern domestic horses studied, which must then have arisen from an independent domestication involving a different wild horse population.

The karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of metaphase chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is disce ...

of Przewalski's horse differs from that of the domestic horse by an extra chromosome pair because of the fission of domestic horse chromosome 5 to produce the Przewalski's horse chromosomes 23 and 24. In comparison, the chromosomal differences between domestic horses and zebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: the Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. zeb ...

s include numerous translocations

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes balanced and unbalanced translocation, with two main types: reciprocal-, and Robertsonian translocation. Reciprocal translo ...

, fusions, inversions and centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers a ...

repositioning. This gives Przewalski's horse the highest diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

chromosome number among all equine species. They can interbreed with the domestic horse and produce fertile offspring (65 chromosomes).

Pleistocene extinctions

Digs in western Canada have unearthed clear evidence horses existed in North America until about 12,000 years ago. However, all Equidae in North America ultimately became extinct. The causes of this extinction (simultaneous with the extinctions of a variety of other Americanmegafauna

In terrestrial zoology, the megafauna (from Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and New Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") comprises the large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant. The most common threshold ...

) have been a matter of debate. Given the suddenness of the event and because these mammals had been flourishing for millions of years previously, something quite unusual must have happened. The first main hypothesis attributes extinction to climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

. For example, in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

, beginning approximately 12,500 years ago, the grasses characteristic of a steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslands, ...

ecosystem gave way to shrub tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

, which was covered with unpalatable plants. The other hypothesis suggests extinction was linked to overexploitation

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term app ...

by newly arrived humans of naive prey that were not habituated to their hunting methods. The extinctions were roughly simultaneous with the end of the most recent glacial advance and the appearance of the big game-hunting Clovis culture

The Clovis culture is a prehistoric Paleoamerican culture, named for distinct stone and bone tools found in close association with Pleistocene fauna, particularly two mammoths, at Blackwater Locality No. 1 near Clovis, New Mexico, in 1936 ...

. Several studies have indicated humans probably arrived in Alaska at the same time or shortly before the local extinction of horses. However, a 2021 study describing archaeological evidence suggesting humans arrived much earlier raises new questions about this theory. Additionally, it has been proposed that the steppe-tundra vegetation transition in Beringia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip ...

may have been a consequence, rather than a cause, of the extinction of megafaunal grazers.

In Eurasia, horse fossils began occurring frequently again in archaeological sites in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

and the southern Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

about 6,000 years ago. From then on, domesticated horses, as well as the knowledge of capturing, taming, and rearing horses, probably spread relatively quickly, with wild mares from several wild populations being incorporated en route.

Return to the Americas

Horses only returned to the Americas withChristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

in 1493. These were Iberian horse

The Iberian horse is a designation given to a number of horse breeds native to the Iberian peninsula. At present, some breeds are officially recognized by the FAO,

s first brought to Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

and later to Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, and, in 1538, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

. The first horses to return to the main continent were 16 specifically identified horses brought by Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

. Subsequent explorers, such as Coronado Coronado may refer to:

People

* Coronado (surname)

* Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1510–1554), Spanish explorer often referred to simply as "Coronado"

* Coronado Chávez (1807–1881), President of Honduras from 1845 to 1847

Places United ...

and De Soto De Soto commonly refers to

* Hernando de Soto (c. 1495 – 1542), Spanish explorer

* DeSoto (automobile), an American automobile brand from 1928 to 1961

De Soto, DeSoto, Desoto, or de Soto may also refer to:

Places in the United States of Ameri ...

, brought ever-larger numbers, some from Spain and others from breeding establishments set up by the Spanish in the Caribbean. Later, as Spanish missions were founded on the mainland, horses would eventually be lost or stolen, and proliferated into large herds of feral horse

A feral horse is a free-roaming horse of domesticated stock. As such, a feral horse is not a wild animal in the sense of an animal without domesticated ancestors. However, some populations of feral horses are managed as wildlife, and these ...

s that became known as mustang