Enesek Syllan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an

The islands may correspond to the

The islands may correspond to the

In 995,

In 995,

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

Historic sites on the Isles of Scilly include:

*

Historic sites on the Isles of Scilly include:

*

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if

Two flags are used to represent Scilly, The

Two flags are used to represent Scilly, The

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration na small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration na small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many

Council of the Isles of Scilly

/u> Source 2

Isles of Scilly Council Tax

/u>

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has

*

* Biography of Llewellyn

retrieved 12 October 2017 a British author of literature for children and adults. * Stephen Richard Menheniott (1957–1976), an 18-year-old English man with learning difficulties who was murdered by his father on the Isles of Scilly in 1976. *

Council of the Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly Tourist Information Centre Website

Isles of Scilly Guidebook and detailed maps of Scilly

Isles of Scilly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Website

*

Cornwall Record Office Online Catalogue for Scilly

*

Images of the Isles of Scilly

at the

Geology of the Isles of Scilly

{{DEFAULTSORT:Scilly, Isles of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England Birdwatching sites in England Celtic Sea Dark-sky preserves in the United Kingdom Duchy of Cornwall

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

off the southwestern tip of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, being over further south than the most southerly point of the British mainland

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is d ...

at Lizard Point.

The total population of the islands at the 2011 United Kingdom census

A census of the population of the United Kingdom is taken every ten years. The 2011 census was held in all countries of the UK on 27 March 2011. It was the first UK census which could be completed online via the Internet. The Office for National ...

was 2,203. Scilly forms part of the ceremonial county

The counties and areas for the purposes of the lieutenancies, also referred to as the lieutenancy areas of England and informally known as ceremonial counties, are areas of England to which lords-lieutenant are appointed. Legally, the areas i ...

of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, and some services are combined with those of Cornwall. However, since 1890, the islands have had a separate local authority. Since the passing of the Isles of Scilly Order 1930, this authority has had the status of a county council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Ireland

The county councils created under British rule in 1899 continue to exist in Irela ...

and today is known as the Council of the Isles of Scilly.

The adjective "Scillonian" is sometimes used for people or things related to the archipelago. The Duchy of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall ( kw, Duketh Kernow) is one of two royal duchies in England, the other being the Duchy of Lancaster. The eldest son of the reigning British monarch obtains possession of the duchy and the title of 'Duke of Cornwall' at ...

owns most of the freehold land on the islands. Tourism is a major part of the local economy, along with agriculture—particularly the production of cut flowers

Cut flowers are flowers or flower buds (often with some stem and leaf) that have been cut from the plant bearing it. It is usually removed from the plant for decorative use. Typical uses are in vase displays, wreaths and garlands. Many gardene ...

.

Etymology

Historically, the Isles of Scilly were known inLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

as ''Insulae Sillinae'', ''Silina'' or ''Siluruni'', corresponding to Greek forms Σίλυρες and Σύρινες, possibly derived from native Celtic roots. In the late middle ages they were known to European navigators as ''Sorlingas'' (Spanish, Portuguese) or ''Sorlingues'' (French). Some authors claim that the Latin ''Sillinae'' is derived or related to ''solis insulae'', “the Isles of the Sun”.

History

Early history

The islands may correspond to the

The islands may correspond to the Cassiterides

The Cassiterides ( el, Κασσιτερίδες, meaning "Tin Islands", from κασσίτερος, ''kassíteros'' "tin") are an ancient geographical name used to refer to a group of islands whose precise location is unknown, but which was believ ...

('Tin Isles') believed by some to have been visited by the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns, and mentioned by the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

. However, there is no evidence of substantial tin mining activity on the islands.

The isles were off the coast of the Brittonic Celtic kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

and later its offshoot, Kernow (Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

), and may have been a part of these polities until their conquest by the English in the 10th century AD.

It is likely that until relatively recent times the islands were much larger and perhaps joined into one island named Ennor. Rising sea levels flooded the central plain around 400–500 AD, forming the current 55 islands and islets, if an island is defined as "land surrounded by water at high tide and supporting land vegetation". Originally written by Ernest Lyon Bowley and published in 1945 by W. P. Kennedy. The word ' is a contraction of the Old Cornish ' (', mutated

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitos ...

to '), meaning 'the land' or the 'great island'.

Evidence for the older large island includes:

* A description written during Roman times designates Scilly "" in the singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular homology

* SINGULAR, an open source Computer Algebra System (CAS)

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, ...

, indicating either a single island or an island much bigger than any of the others.

* Remains of a prehistoric farm have been found on Nornour, which is now a small rocky skerry

A skerry is a small rocky island, or islet, usually too small for human habitation. It may simply be a rocky reef. A skerry can also be called a low sea stack.

A skerry may have vegetative life such as moss and small, hardy grasses. They a ...

far too small for farming.; (includes the description of over 250 Roman fibulae found at the site) There once was an Iron Age British community here that extended into Roman times. This community was likely formed by immigrants from Brittany, probably the Veneti who were active in the tin trade that originated in mining activity in Cornwall and Devon.

* At certain low tides the sea becomes shallow enough for people to walk between some of the islands. This is possibly one of the sources for stories of drowned lands, e.g. Lyonesse

Lyonesse is a kingdom which, according to legend, consisted of a long strand of land stretching from Land's End at the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England, to what is now the Isles of Scilly in the Celtic Sea portion of the Atlantic Ocean. I ...

.

* Ancient field walls are visible below the high tide line off some of the islands, such as Samson

Samson (; , '' he, Šīmšōn, label= none'', "man of the sun") was the last of the judges of the ancient Israelites mentioned in the Book of Judges (chapters 13 to 16) and one of the last leaders who "judged" Israel before the institution o ...

.

* Some of the Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or ) , is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. It is a List of revived languages, revived language, having become Extinct language, extinct as a livin ...

place names also appear to reflect past shorelines, and former land areas.

* The whole of southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes G ...

has been steadily sinking in opposition to post-glacial rebound

Post-glacial rebound (also called isostatic rebound or crustal rebound) is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound a ...

in Scotland: this has caused the ria

A ria (; gl, ría) is a coastal inlet formed by the partial submergence of an unglaciated river valley. It is a drowned river valley that remains open to the sea.

Definitions

Typically rias have a Drainage system (geomorphology)#Dendritic dr ...

s (drowned river valleys) on the southern Cornish coast, e.g. River Fal

The River Fal ( kw, Dowr Fala) flows through Cornwall, England, rising at Pentevale on Goss Moor (between St. Columb and Roche) and reaching the English Channel at Falmouth. On or near the banks of the Fal are the castles of Pendennis and ...

and the Tamar Estuary

Tamar may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Tamar'' (album), by Tamar Braxton, 2000

* ''Tamar'' (novel), by Mal Peet, 2005

* ''Tamar'' (poem), an epic poem by Robinson Jeffers

People

* Tamar (name), including a list of people with ...

.

Offshore, midway between Land's End

Land's End ( kw, Penn an Wlas or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

and the Isles of Scilly, is the supposed location of the mythical lost land of Lyonesse

Lyonesse is a kingdom which, according to legend, consisted of a long strand of land stretching from Land's End at the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England, to what is now the Isles of Scilly in the Celtic Sea portion of the Atlantic Ocean. I ...

, referred to in Arthurian

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a Legend, legendary king of Great Britain, Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest tradition ...

literature, of which Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

is said to have been a prince. This may be a folk memory Folk memory, also known as folklore or myths, refers to past events that have been passed orally from generation to generation. The events described by the memories may date back hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of years and often hav ...

of inundated lands, but this legend is also common among the Brythonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

peoples; the legend of Ys is a parallel and cognate legend in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

as is that of in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

.

Scilly has been identified as the place of exile of two heretical 4th century bishops, Instantius and Tiberianus, who were followers of Priscillian

Priscillian (in Latin: ''Priscillianus''; Gallaecia, - Augusta Treverorum, Gallia Belgica, ) was a wealthy nobleman of Roman Hispania who promoted a strict form of Christian asceticism. He became bishop of Ávila in 380. Certain practices of his f ...

.

Norse and Norman period

Olaf Tryggvason

Olaf Tryggvason (960s – 9 September 1000) was King of Norway from 995 to 1000. He was the son of Tryggvi Olafsson, king of Viken (Vingulmark, and Rånrike), and, according to later sagas, the great-grandson of Harald Fairhair, first King of N ...

became King Olaf I of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. Born 960, Olaf had raided various European cities and fought in several wars. In 986 he met a Christian seer

In the United States, the efficiency of air conditioners is often rated by the seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER) which is defined by the Air Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, a trade association, in its 2008 standard AHRI ...

on the Isles of Scilly. He was probably a follower of Priscillian

Priscillian (in Latin: ''Priscillianus''; Gallaecia, - Augusta Treverorum, Gallia Belgica, ) was a wealthy nobleman of Roman Hispania who promoted a strict form of Christian asceticism. He became bishop of Ávila in 380. Certain practices of his f ...

and part of the tiny Christian community that was exiled here from Spain by Emperor Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; cy, Macsen Wledig ; died 8 August 388) was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian in 383 through negotiation with emperor Theodosius I.

He was made emperor in B ...

for Priscillianism

Priscillianism was a Christian sect developed in the Iberian Peninsula under the Roman Empire in the 4th century by Priscillian. It is derived from the Gnostic doctrines taught by Marcus, an Egyptian from Memphis. Priscillianism was later conside ...

. In Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of the ...

's Royal Sagas of Norway, it is stated that this seer told him:

Thou wilt become a renowned king, and do celebrated deeds. Many men wilt thou bring to faith and baptism, and both to thy own and others' good; and that thou mayst have no doubt of the truth of this answer, listen to these tokens. When thou comest to thy ships many of thy people will conspire against thee, and then a battle will follow in which many of thy men will fall, and thou wilt be wounded almost to death, and carried upon a shield to thy ship; yet after seven days thou shalt be well of thy wounds, and immediately thou shalt let thyself be baptised.The legend continues that, as the seer foretold, Olaf was attacked by a group of

mutineers

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among memb ...

upon returning to his ships. As soon as he had recovered from his wounds, he let himself be baptised. He then stopped raiding Christian cities, and lived in England and Ireland. In 995, he used an opportunity to return to Norway. When he arrived, the Haakon Jarl

Haakon Sigurdsson ( non, Hákon Sigurðarson , no, Håkon Sigurdsson; 937–995), known as Haakon Jarl (Old Norse: ''Hákon jarl''), was the ''de facto'' ruler of Norway from about 975 to 995. Sometimes he is styled as Haakon the Powerful ( n ...

was facing a revolt. Olaf Tryggvason persuaded the rebels to accept him as their king, and Jarl Haakon was murdered by his own slave, while he was hiding from the rebels in a pig sty.

With the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

, the Isles of Scilly came more under centralised control. About 20 years later, the Domesday survey

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

was conducted. The islands would have formed part of the "Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

Domesday" circuit, which included Cornwall, Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, Dorset, Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, and Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

.

In the mid-12th century, there was reportedly a Viking attack on the Isles of Scilly, called by the Norse, recorded in the '—Sweyn Asleifsson

Sweyn Asleifsson or Sveinn Ásleifarson ( 1115 – 1171) was a twelfth-century Viking who appears in the '' Orkneyinga Saga''.

Early career

Sweyn was born in Caithness in the early twelfth century, to Olaf Hrolfsson and his wife Åsleik. Accordin ...

"went south, under Ireland, and seized a barge belonging to some monks in Syllingar and plundered it." (Chap LXXIII)

...the three chiefs—Swein, Þorbjörn and Eirik—went out on a plundering expedition. They went first to the Suðreyar ebrides and all along the west to the Syllingar, where they gained a great victory in Maríuhöfn on Columba's-mass June and took much booty. Then they returned to the Orkneys."" literally means "Mary's Harbour/Haven". The name does not make it clear if it referred to a harbour on a larger island than today's St Mary's, or a whole island. It is generally considered that Cornwall, and possibly the Isles of Scilly, came under the dominion of the English Crown late in the reign of

Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first ...

( 924–939). In early times one group of islands was in the possession of a confederacy of hermits. King Henry I (r. 1100–35) gave it to the abbey of Tavistock who established a priory on Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring to ...

, which was abolished at the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

Later Middle Ages and early modern period

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

stat ngthat they hold certain isles in the sea between Cornwall and Ireland, of which the largest is called Scilly, to which ships come passing between France, Normandy, Spain,William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (possibly Spanish). It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking theBayonne Bayonne (; eu, Baiona ; oc, label= Gascon, Baiona ; es, Bayona) is a city in Southwestern France near the Spanish border. It is a commune and one of two subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine re ...,Gascony Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ..., Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Cornwall: and, because they feel that in the event of a war breaking out between the kings of England and France, or between any of the other places mentioned, they would not have enough power to do justice to these sailors, they ask that they might exchange these islands for lands in Devon, saving the churches on the islands appropriated to them.

Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or ) , is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. It is a List of revived languages, revived language, having become Extinct language, extinct as a livin ...

, but the language seems to have gone into decline in Cornwall beginning in the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

; it was still dominant between the islands and Bodmin at the time of the Reformation, but it suffered an accelerated decline thereafter. The islands appear to have lost the old Celtic language before parts of Penwith

Penwith (; kw, Pennwydh) is an area of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, located on the peninsula of the same name. It is also the name of a former Non-metropolitan district, local government district, whose council was based in Penzance. ...

on the mainland, in contrast to the history of Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

or Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

.

During the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, the Parliamentarians captured the isles, only to see their garrison mutiny and return the isles to the Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

. By 1651 the Royalist governor, Sir John Grenville, was using the islands as a base for privateering

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

raids on Commonwealth and Dutch shipping. The Dutch admiral Maarten Tromp

Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp (also written as ''Maerten Tromp''; 23 April 1598 – 31 July 1653) was a Dutch army general and admiral in the Dutch navy.

Son of a ship's captain, Tromp spent much of his childhood at sea, including being captured ...

sailed to the isles and on arriving on 30 May 1651 demanded compensation. In the absence of compensation or a satisfactory reply, he declared war on England in June. It was during this period that the disputed Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years' War

The Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years' War ( nl, Driehonderdvijfendertigjarige Oorlog, kw, Bell a dri hans pymthek warn ugens) was an alleged state of war between the Netherlands and the Isles of Scilly (located off the southwest coast of Gr ...

started between the isles and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

.

In June 1651, Admiral Robert Blake

General at Sea Robert Blake (27 September 1598 – 17 August 1657) was an English naval officer who served as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports from 1656 to 1657. Blake is recognised as the chief founder of England's naval supremacy, a d ...

recaptured the isles for the Parliamentarians. Blake's initial attack on Old Grimsby

Old Grimsby ( kw, Enysgrymm Goth) is a coastal settlement on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly, England.Ordnance Survey mapping It is located on the east side of the island and there is a quay. At the southern end of the harbour bay is t ...

failed, but the next attacks succeeded in taking Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring to ...

and Bryher

Bryher ( kw, Breyer "place of hills") is one of the smallest inhabited islands of the Isles of Scilly, with a population of 84 in 2011, spread across .

History

The name of the island is recorded as ''Brayer'' in 1336 and ''Brear'' in 1500.

Ge ...

. Blake placed a battery on Tresco to fire on St Mary's, but one of the guns exploded, killing its crew and injuring Blake. A second battery proved more successful. Subsequently, Grenville and Blake negotiated terms that permitted the Royalists to surrender honourably. The Parliamentary forces then set to fortifying the islands. They built Cromwell's Castle

Cromwell's Castle is an artillery fort overlooking New Grimsby harbour on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly. It comprises a tall, circular gun tower and an adjacent gun platform, and was designed to prevent enemy naval vessels from e ...

—a gun platform on the west side of Tresco—using materials scavenged from an earlier gun platform further up the hill. Although this poorly sited earlier platform dated back to the 1550s, it is now referred to as King Charles's Castle

King Charles's Castle is a ruined artillery fort overlooking New Grimsby harbour on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly. Built between 1548 and 1551 to protect the islands from French attack, it would have held a battery of guns and a ...

.

The Isles of Scilly served as a place of exile during the English Civil War. Among those exiled there was Unitarian Jon Biddle.

During the night of 22 October 1707, the isles were the scene of one of the worst maritime disasters in British history, when out of a fleet of 21 Royal Navy ships headed from Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, six were driven onto the cliffs. Four of the ships sank or capsized, with at least 1,450 dead, including the commanding admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir Cloudesley Shovell

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Cloudesley Shovell (c. November 1650 – 22 or 23 October 1707) was an English naval officer. As a junior officer he saw action at the Battle of Solebay and then at the Battle of Texel during the Third Anglo-Dutch War. ...

.

There is evidence of inundation by the tsunami caused by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In combination with ...

.

Ancient monuments and historic buildings

Historic sites on the Isles of Scilly include:

*

Historic sites on the Isles of Scilly include:

* Bant's Carn

Bant's Carn is a Bronze Age Scillonian entrance grave, entrance grave located on a steep slope on the island of St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's in the Isles of Scilly, England. The tomb is one of the best examples of a Scillonian entrance ...

, a Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

entrance grave

Entrance grave is a type of Neolithic and early Bronze Age chamber tomb found primarily in Great Britain. The burial monument typically consisted of a circular mound bordered by a stone curb, erected over a rectangular burial chamber and access ...

* Halangy Down Ancient Village

* Porth Hellick Down Burial Chamber

* Innisidgen Lower and Upper Burial Chambers

* The Old Blockhouse

* King Charles's Castle

King Charles's Castle is a ruined artillery fort overlooking New Grimsby harbour on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly. Built between 1548 and 1551 to protect the islands from French attack, it would have held a battery of guns and a ...

* Harry's Walls, an unfinished artillery fort

* Garrison Tower

Garrison Tower is a Grade II listed structure on St Mary's, Isles of Scilly

The tower was built in the 17th century as a windmill. By 1750 it was abandoned and in a ruined condition. The remains were converted to a lookout tower in the 1830s by H ...

* Cromwell's Castle

Cromwell's Castle is an artillery fort overlooking New Grimsby harbour on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly. It comprises a tall, circular gun tower and an adjacent gun platform, and was designed to prevent enemy naval vessels from e ...

Governors of Scilly

An early governor of Scilly wasThomas Godolphin

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, whose son Francis

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

* Rural M ...

received a lease on the Isles in 1568. They were styled ''Governors of Scilly'' and the Godolphins and their Osborne relatives held this position until 1834. In 1834 Augustus John Smith acquired the lease from the Duchy for £20,000. Smith created the title ''Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly'' for himself, and many of his actions were unpopular. The lease remained in his family until it expired for most of the Isles in 1920 when ownership reverted to the Duchy of Cornwall. Today, the Dorrien-Smith estate still holds the lease for the island of Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring to ...

.

* 1568–1608 Sir Francis Godolphin (1540–1608)

* 1608–1613 Sir William Godolphin of Godolphin (1567–1613)

* 1613–1636 William Godolphin (1611–1636)

* 1636–1643 Sidney Godolphin

Sidney Godolphin is the name of:

* Sidney Godolphin (colonel) (1652–1732), Member of Parliament for fifty years

* Sidney Godolphin (poet) (1610–1643), English poet

* Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin (c. 1640–1712), leading British poli ...

(1610–1643)

* 1643–1646 Sir Francis Godolphin of Godolphin (1605–1647)

* 1647–1648 Anthony Buller (Parliamentarian)

* 1649–1651 Sir John Grenville (Royalist)

* 1651–1660 Joseph Hunkin (Parliamentary control)

* 1660–1667 Sir Francis Godolphin of Godolphin (1605–1667) (restored to office)

* 1667–1700 The 1st Earl of Godolphin (1645–1712)

* 1700–1732 Sidney Godolphin

Sidney Godolphin is the name of:

* Sidney Godolphin (colonel) (1652–1732), Member of Parliament for fifty years

* Sidney Godolphin (poet) (1610–1643), English poet

* Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin (c. 1640–1712), leading British poli ...

(1652–1732)

* 1733–1766 The 2nd Earl of Godolphin (1678–1766)

* 1766–1785 The 2nd Baron Godolphin (1706–1785)

* 1785–1799 The 5th Duke of Leeds (1751–1799)

* 1799–1831 The 6th Duke of Leeds (1775–1838)

* 1834–1872 Augustus Smith (1804–1872)

* 1872–1918 Thomas Smith-Dorrien-Smith

Lieutenant Thomas Algernon Smith-Dorrien-Smith (7 February 1846 – 6 August 1918) was Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly from 1872 until his death in 1918.

Family

Thomas Algernon Smith-Dorrien-Smith was born on 7 February 1846 at Berkha ...

(1846–1918)

* 1918–1920 Arthur Dorrien-Smith

Major Arthur Algernon Dorrien-Smith (28 January 1876 – 30 May 1955) was Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly from 1918 to 1920.

Family

Major Arthur Algernon Smith-Dorrien-Smith was born on 28 January 1876, in Oxfordshire, to Thomas Smith ...

(1876–1955)

Geography

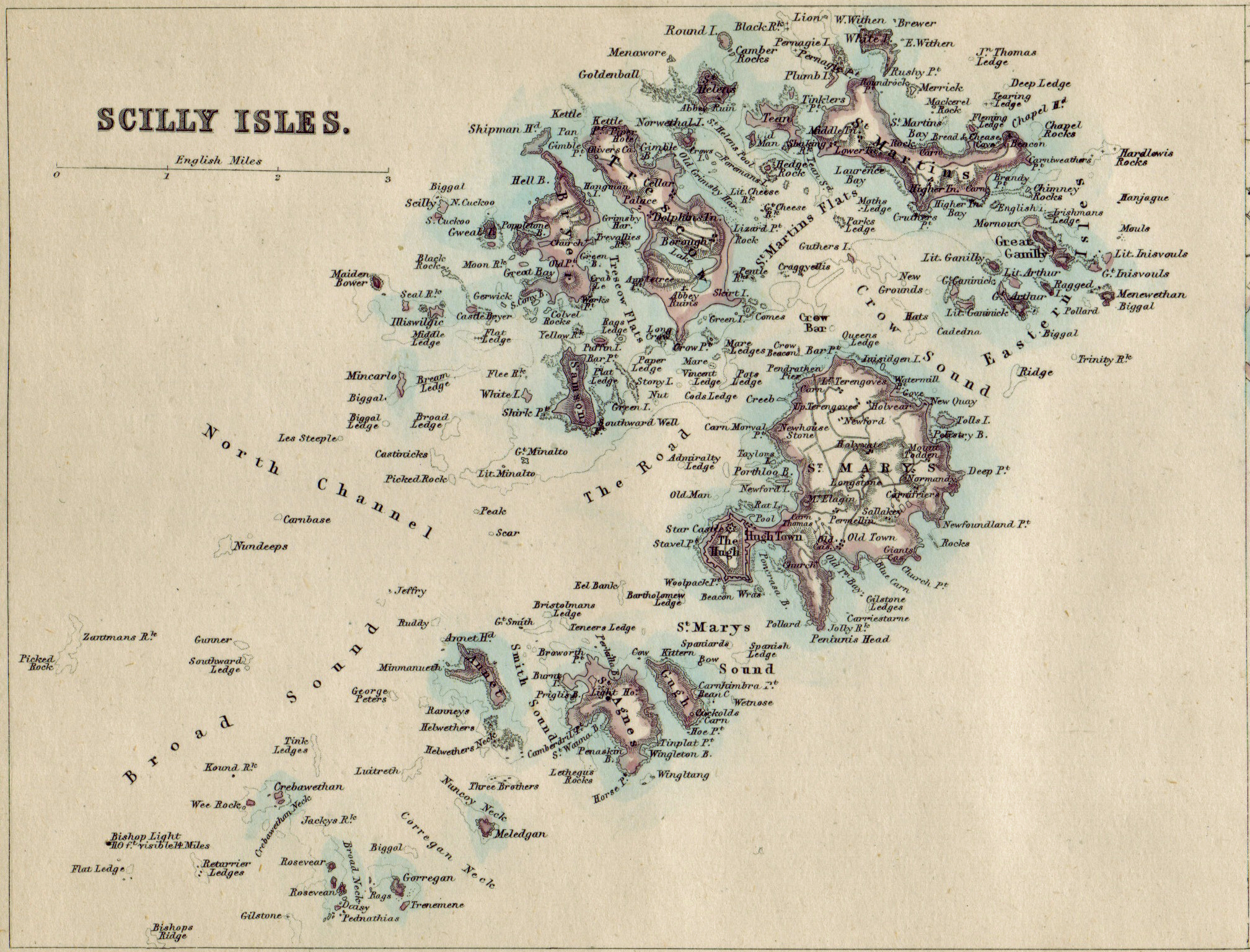

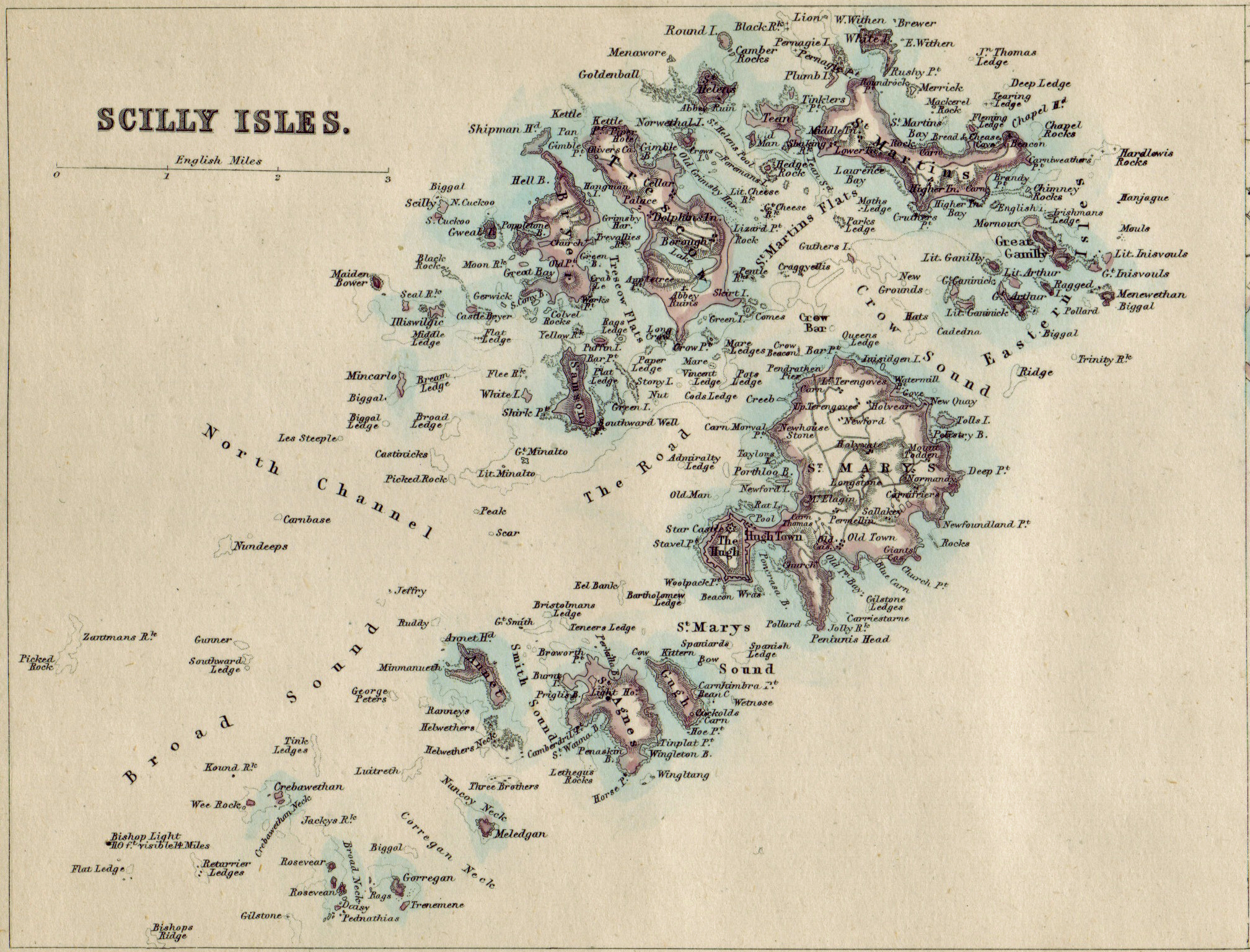

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if Gugh

Gugh (; kw, Keow, meaning "hedge banks") could be described as the sixth inhabited island of the Isles of Scilly, but is usually included with St Agnes with which it is joined by a sandy tombolo known as "The Bar" when exposed at low tide. The ...

is counted separately from St Agnes) and numerous other small rocky islet

An islet is a very small, often unnamed island. Most definitions are not precise, but some suggest that an islet has little or no vegetation and cannot support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/or hard coral; may be permanent ...

s (around 140 in total) lying off Land's End

Land's End ( kw, Penn an Wlas or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

.

The islands' position produces a place of great contrast; the ameliorating effect of the sea, greatly influenced by the North Atlantic Current

The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

The NAC originates from wher ...

, means they rarely have frost or snow, which allows local farmers to grow flowers well ahead of those in mainland Britain. The chief agricultural product is cut flowers, mostly daffodil

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as '' Sternbergia'', ''Is ...

s. Exposure to Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

winds also means that spectacular winter gales lash the islands from time to time. This is reflected in the landscape, most clearly seen on Tresco where the lush Abbey Gardens on the sheltered southern end of the island contrast with the low heather and bare rock sculpted by the wind on the exposed northern end.

Natural England

Natural England is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. It is responsible for ensuring that England's natural environment, including its land, flora and fauna, ...

has designated the Isles of Scilly as National Character Area 158. As part of a 2002 marketing campaign, the plant conservation charity Plantlife

Plantlife is the international conservation membership charity working to secure a world rich in wild plants and fungi. It is the only UK membership charity dedicated to conserving wild plants and fungi in their natural habitats and helping peo ...

chose sea thrift (''Armeria maritima

''Armeria maritima'', the thrift, sea thrift or sea pink, is a species of flowering plant in the family Plumbaginaceae. It is a compact evergreen perennial which grows in low clumps and sends up long stems that support globes of bright pink flow ...

'') as the "county flower

In a number of countries, plants have been chosen as symbols to represent specific geographic areas. Some countries have a country-wide floral emblem; others in addition have symbols representing subdivisions. Different processes have been used to ...

" of the islands.

This table provides an overview of the most important islands:

(1) Inhabited until 1855.

In 1975 the islands were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB; , AHNE) is an area of countryside in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, that has been designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Areas are designated in recognition of thei ...

. The designation covers the entire archipelago, including the uninhabited islands and rocks, and is the smallest such area in the UK. The islands of Annet and Samson have large tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated as a subgroup of the family Laridae which includes gulls and skimmers and consists of e ...

eries and the islands are well populated by seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

. The Isles of Scilly are the only British haunt of the lesser white-toothed shrew

The lesser white-toothed shrew (''Crocidura suaveolens'') is a tiny shrew with a widespread distribution in Africa, Asia and Europe. Its preferred habitat is scrub and gardens and it feeds on insects, arachnids, worms, gastropods, newts and sm ...

(''Crocidura suaveolens''), where it is known locally as a "''teak''" or "''teke''".

The islands are famous among birdwatchers

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device like binoculars or a telescope, by ...

for the large variety of rare and migratory birds that visit the islands. The peak time of year for sightings is generally in the autumn.

Tidal influx

The tidal range at the Isles of Scilly is high for an open sea location; the maximum for St Mary's is . Additionally, the inter-island waters are mostly shallow, which atspring tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables can ...

allows for dry land walking between several of the islands. Many of the northern islands can be reached from Tresco, including Bryher, Samson and St Martin's (requires very low tides). From St Martin's White Island, Little Ganilly and Great Arthur are reachable. Although the sound between St Mary's and Tresco, The Road, is fairly shallow, it never becomes totally dry, but according to some sources it should be possible to wade at extreme low tides. Around St Mary's several minor islands become accessible, including Taylor's Island on the west coast and Tolls Island on the east coast. From Saint Agnes, Gugh becomes accessible at each low tide, via a tombolo

A tombolo is a sandy or shingle isthmus. A tombolo, from the Italian ', meaning 'pillow' or 'cushion', and sometimes translated incorrectly as ''ayre'' (an ayre is a shingle beach of any kind), is a deposition landform by which an island become ...

.

Climate

The Isles of Scilly have atemperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

oceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate, is the humid temperate climate sub-type in Köppen classification ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of continents, generally featuring cool summers and mild winters ( ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

: ''Cfb''), which borders a humid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

(Cf) under the Trewartha climate classification

The Trewartha climate classification (TCC) or the Köppen–Trewartha climate classification (KTC) is a climate classification system first published by American geographer Glenn Thomas Trewartha in 1966. It is a modified version of the Köppen ...

. The average annual temperature is , the warmest place in the British Isles. Winters are, by far, the warmest in the UK due to the moderating effects of the North Atlantic Drift

The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

The NAC originates from wher ...

of the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Current, North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida a ...

. Despite being on exactly the same latitude as Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749,6 ...

in Canada, snow and frost are extremely rare. The maximum snowfall was on 12 January 1987. Summer heat is moderated by the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and summer temperatures are not as warm as on the mainland. However, the Isles are one of the sunniest areas in the southwest with an average of seven hours per day in May. The lowest temperature ever recorded was and the highest was . The isles have never recorded a temperature below freezing in the months from May to November inclusive. Precipitation (the overwhelming majority of which is rain) averages about per year. The wettest months are from October to January, while April and May are the driest months.

Geology

All the islands of Scilly are all composed ofgranite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

rock of Early Permian 01 or '01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* '01 (Richard Müller album), 01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* 01 (Son of Dave album), ''01'' (Son of Dave album), 2000

* 01 (Urban ...

age, an exposed part of the Cornubian batholith

The Cornubian batholith is a large mass of granite rock, formed about 280 million years ago, which lies beneath much of Devon and Cornwall, the south-western peninsula of Great Britain. The main exposed masses of granite are seen at Dartmoor, Bo ...

. The Irish Sea Glacier

The Irish Sea Glacier was a huge glacier during the Pleistocene Ice Age that, probably on more than one occasion, flowed southwards from its source areas in Scotland and Ireland and across the Isle of Man, Anglesey and Pembrokeshire. It probab ...

terminated just to the north of the Isles of Scilly during the last ice age.

Fauna

Government

National government

Politically, the islands are part of England, one of the fourcountries of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK), since 1922, comprises three constituent countries and a region: England, Scotland, and Wales (which collectively make up the region of Great Britain), as well as Nor ...

. They are represented in the UK Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremac ...

as part of the St Ives constituency. As part of the United Kingdom, the islands were

''Were'' and ''wer'' are archaic terms for adult male humans and were often used for alliteration with wife as "were and wife" in Germanic-speaking cultures ( ang, wer, odt, wer, got, waír, ofs, wer, osx, wer, goh, wer, non, verr).

In ...

part of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

and were represented in the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adopts ...

as part of the multi-member South West England constituency.

Local government

Historically, the Isles of Scilly were administered as one of thehundreds of Cornwall

The hundreds of Cornwall ( kw, Keverangow Kernow) were administrative divisions or Shires ( hundreds) into which Cornwall, the present day administrative county of England, in the United Kingdom, was divided between and 1894, when they were re ...

, although the Cornwall quarter sessions

The courts of quarter sessions or quarter sessions were local courts traditionally held at four set times each year in the Kingdom of England from 1388 (extending also to Wales following the Laws in Wales Act 1535). They were also established in ...

had limited jurisdiction there. For judicial purposes, shrievalty

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

purposes, and lieutenancy

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ...

purposes, the Isles of Scilly are "deemed to form part of the county of Cornwall".

The Local Government Act 1888

Local may refer to:

Geography and transportation

* Local (train), a train serving local traffic demand

* Local, Missouri, a community in the United States

* Local government, a form of public administration, usually the lowest tier of administrat ...

allowed the Local Government Board

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 (C. 70) and took over the public health a ...

to establish in the Isles of Scilly "councils and other local authorities separate from those of the county of Cornwall"... "for the application to the islands of any act touching local government." Accordingly, in 1890 the ''Isles of Scilly Rural District Council'' (the RDC) was formed as a ''sui generis

''Sui generis'' ( , ) is a Latin phrase that means "of its/their own kind", "in a class by itself", therefore "unique".

A number of disciplines use the term to refer to unique entities. These include:

* Biology, for species that do not fit in ...

'' unitary authority

A unitary authority is a local authority responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are usually performed by a higher level of sub-national government or the national governmen ...

, outside the administrative county

An administrative county was a first-level administrative division in England and Wales from 1888 to 1974, and in Ireland from 1899 until either 1973 (in Northern Ireland) or 2002 (in the Republic of Ireland). They are now abolished, although mos ...

of Cornwall. Cornwall County Council provided some services to the Isles, for which the RDC made financial contributions. The Isles of Scilly Order 1930 granted the council the "powers, duties and liabilities" of a county council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Ireland

The county councils created under British rule in 1899 continue to exist in Irela ...

. Section 265 of the Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant Acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

allowed for the continued existence of the RDC, but renamed as the ''Council of the Isles of Scilly''. This unusual status also means that much administrative law (for example relating to the functions of local authorities, the health service and other public bodies) that applies in the rest of England applies in modified form in the islands.

With a total population of just over 2,000, the council represents fewer inhabitants than many English parish councils, and is by far the smallest English unitary council. , 130 people are employed full-time

Full-time or Full Time may refer to:

* Full-time job, employment in which a person works a minimum number of hours defined as such by their employer

* Full-time mother, a woman whose work is running or managing her family's home

* Full-time fat ...

by the council to provide local services (including water supply and air traffic control

Air traffic control (ATC) is a service provided by ground-based air traffic controllers who direct aircraft on the ground and through a given section of controlled airspace, and can provide advisory services to aircraft in non-controlled airs ...

). These numbers are significant, in that almost 10% of the adult population of the islands is directly linked to the council, as an employee or a councillor.

The Council consists of 16 elected councillors, 12 of whom are returned by the ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

of St Mary's, and one from each of four "off-island" wards (St Martin's, St Agnes, Bryher, and Tresco). The latest elections took place on 6 May 2021; all 15 councillors elected were independents. One seat, for the island of Bryher, received no nominations and remained vacant until filled by a further independent councillor on 28 May.

The council is headquartered at Town Hall, by The Parade park in Hugh Town

Hugh Town ( kw, Treworenys or ) is the largest settlement on the Isles of Scilly and its administrative centre. The town is situated on the island of St Mary's, the largest and most populous island in the archipelago, and is located on a narrow ...

, and also performs the administrative functions of the AONB

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB; , AHNE) is an area of countryside in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, that has been designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Areas are designated in recognition of thei ...

Partnership and the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority

There are 10 Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authorities (IFCAs) in England. The 10 IFCA Districts cover English coastal waters out to 6 nautical miles from Territorial Baselines.

Although autonomous the 10 IFCAs have a shared 'vision' to "lead, ...

.

Some aspects of local government are shared with Cornwall, including health

Health, according to the World Health Organization, is "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity".World Health Organization. (2006)''Constitution of the World Health Organiza ...

, and the Council of the Isles of Scilly together with Cornwall Council

Cornwall Council ( kw, Konsel Kernow) is the unitary authority for Cornwall in the United Kingdom, not including the Isles of Scilly, which has its own unitary council. The council, and its predecessor Cornwall County Council, has a tradition o ...

form a Local Enterprise Partnership

In England, local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) are voluntary partnerships between local authorities and businesses, set up in 2011 by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to help determine local economic priorities and lead econo ...

. In July 2015 a devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories h ...

deal was announced by the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

under which Cornwall Council and the Council of the Isles of Scilly are to create a plan to bring health and social care services together under local control. The Local Enterprise Partnership is also to be bolstered.

Flags

Scillonian Cross

The Scillonian Cross ( kw, Baner Syllan) is a county flag created in 2002 for the Isles of Scilly, United Kingdom. The flag was designed by the ''Scilly News'', and received positive support from its readers in a popular vote, leading to it be ...

, selected by readers of ''Scilly News'' in a 2002 vote and then registered with the Flag Institute

The Flag Institute is a UK membership organisation headquartered in Kingston upon Hull, England, concerned with researching and promoting the use and design of flags. It documents flags in the UK and internationally, maintains a UK Flag Registr ...

as the flag of the islands, and the flag of the Council of the Isles of Scilly, which incorporates the council's logo and represents the council. An adapted version of the old Board of Ordnance flag has also been used, after it was left behind when munitions were removed from the isles. The "Cornish Ensign" (the Cornish cross with the Union Jack in the canton) has also been used.

Emergency services

The Isles of Scilly form part of theDevon and Cornwall Police

Devon and Cornwall Police is the territorial police force responsible for policing the ceremonial counties of Devon and Cornwall (including the Isles of Scilly) in England. The force serves approximately 1.8 million people over an area of .

Hi ...

force area. There is a police station in Hugh Town

Hugh Town ( kw, Treworenys or ) is the largest settlement on the Isles of Scilly and its administrative centre. The town is situated on the island of St Mary's, the largest and most populous island in the archipelago, and is located on a narrow ...

.

The Cornwall Air Ambulance

The Cornwall Air Ambulance Trust is a charity that provides a dedicated helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS) for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly.

The service also has two critical care cars that operate when the helicopter is unable t ...

helicopter provides cover to the islands.

The islands have their own independent fire brigade – the Isles of Scilly Fire and Rescue Service

The Isles of Scilly Fire and Rescue Service is the statutory local authority fire and rescue service covering the Isles of Scilly off the coast of the South West of England. It is the smallest fire and rescue service in the United Kingdom and t ...

– which is staffed entirely by retained firefighters on all the inhabited islands.

The emergency ambulance service is provided by the South Western Ambulance Service with full-time paramedic

A paramedic is a registered healthcare professional who works autonomously across a range of health and care settings and may specialise in clinical practice, as well as in education, leadership, and research.

Not all ambulance personnel are p ...

s employed to cover the islands working with emergency care attendants.

Education

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands Academy

Five Islands Academy, formerly Five Islands School, is the first federated school in the United Kingdom, providing primary and secondary education for children from 3 to 16 at five sites in the Isles of Scilly. As of May 2022, the headteacher ...

, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's, with secondary students from outside St Mary's living at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week. Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for A-l ...

place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation.

Economy

Historical context

Since the mid-18th century the Scillonian economy has relied on trade with the mainland and beyond as a means of sustaining its population. Over the years the nature of this trade has varied, due to wider economic and political factors that have seen the rise and fall of industries such askelp

Kelps are large brown algae seaweeds that make up the order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genera. Despite its appearance, kelp is not a plant - it is a heterokont, a completely unrelated group of organisms.

Kelp grows in "underwat ...

harvesting, pilotage

Piloting or pilotage is the process of navigating on water or in the air using fixed points of reference on the sea or on land, usually with reference to a nautical chart or aeronautical chart to obtain a fix of the position of the vessel or air ...

, smuggling, fishing, shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

and, latterly flower farming

Floriculture, or flower farming, is a branch of horticulture concerned with the cultivation of flowering and ornamental plants for gardens and for floristry, comprising the floral industry. The development of new varieties by plant breeding is ...

. In a 1987 study of the Scillonian economy, Neate found that many farms on the islands were struggling to remain profitable due to increasing costs and strong competition from overseas producers, with resulting diversification into tourism. Statistics suggest that agriculture on the islands now represents less than 2% of all employment.''Isles of Scilly Integrated Area Plan 2001–2004'', Isles of Scilly Partnership 2001

Tourism

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration na small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration na small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birdwatchers

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device like binoculars or a telescope, by ...

("twitchers") arrive.

Ornithology

Because of its position, Scilly is the first landing for many migrant birds, including extreme rarities from North America andSiberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. Scilly is situated far into the Atlantic Ocean, so many American vagrant birds will make first European landfall in the archipelago.

If an extremely rare bird turns up, the island will see a significant increase in numbers of birdwatchers. This type of birding, chasing after rare birds, is called " twitching".

The islands are home to ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

Will Wagstaff

William Wagstaff, commonly known as Will Wagstaff, is a British ornithologist and naturalist in the Isles of Scilly, and also an author. His popular guided wildlife walks have made him both a well-known and popular figure in the islands. Origi ...

.

Employment

The predominance of tourism means that "tourism is by far the main sector throughout each of the individual islands, in terms of employment... ndthis is much greater than other remote and rural areas in the United Kingdom". Tourism accounts for approximately 63% of all employment. Businesses dependent on tourism, with the exception of a few hotels, tend to be small enterprises typically employing fewer than four people; many of these are family run, suggesting an entrepreneurial culture among the local population. However, much of the work generated by this, with the exception of management, is low skilled and thus poorly paid, especially for those involved in cleaning, catering and retail. Because of the seasonality of tourism, many jobs on the islands are seasonal and part-time, so work cannot be guaranteed throughout the year. Some islanders take up other temporary jobs 'out of season' to compensate for this. Due to a lack of local casual labour at peak holiday times, many of the larger employers accommodate guest workers.Taxation

The islands were not subject toincome tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

until 1954, and there was no motor vehicle excise duty Vehicle Excise Duty (VED; also known as "vehicle tax", "car tax", and more controversially as "road tax", and formerly as a "tax disc") is an annual tax that is levied as an excise duty and which must be paid for most types of powered vehicles which ...

levied until 1971. The Council Tax

Council Tax is a local taxation system used in England, Scotland and Wales. It is a tax on domestic property, which was introduced in 1993 by the Local Government Finance Act 1992, replacing the short-lived Community Charge

The Community C ...

is set by the Local Authority in order to meet their budget requirements. The Valuation Office Agency

The Valuation Office Agency is a government body in England and Wales. It is an executive agency of His Majesty's Revenue and Customs.

The agency values properties for the purpose of Council Tax and for non-domestic rates in England and Wale ...

values properties for the purpose of council tax

Council Tax is a local taxation system used in England, Scotland and Wales. It is a tax on domestic property, which was introduced in 1993 by the Local Government Finance Act 1992, replacing the short-lived Community Charge

The Community C ...

. The amount of council tax you have to pay depends on the band of your property as shown on the graph below. The valuation is based on what the property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

would have been worth in 1991

File:1991 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Boris Yeltsin, elected as Russia's first president, waves the new flag of Russia after the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, orchestrated by Soviet hardliners; Mount Pinatubo erupts in the Phil ...

.

Source 1Council of the Isles of Scilly

/u> Source 2

Isles of Scilly Council Tax

/u>

Transport

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxis

A taxis (; ) is the movement of an organism in response to a stimulus such as light or the presence of food. Taxes are innate behavioural responses. A taxis differs from a tropism (turning response, often growth towards or away from a stimulu ...

and a tour bus

A bus (contracted from omnibus, with variants multibus, motorbus, autobus, etc.) is a road vehicle that carries significantly more passengers than an average car or van. It is most commonly used in public transport, but is also in use for cha ...