Emperor Justinianus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the

''

Justinian achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, particularly through the complete revision of all

Justinian achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, particularly through the complete revision of all

In this war, the contemporary

In this war, the contemporary

As in Africa, dynastic struggles in

As in Africa, dynastic struggles in

Belisarius had been recalled in the face of renewed hostilities by the

Belisarius had been recalled in the face of renewed hostilities by the

Finally, Justinian dispatched a force of approximately 35,000 men (2,000 men were detached and sent to invade southern

Finally, Justinian dispatched a force of approximately 35,000 men (2,000 men were detached and sent to invade southern

In addition to the other conquests, the Empire established a presence in

In addition to the other conquests, the Empire established a presence in

Another prominent church in the capital, the

Another prominent church in the capital, the

As was the case under Justinian's predecessors, the Empire's economic health rested primarily on agriculture. In addition, long-distance trade flourished, reaching as far north as

As was the case under Justinian's predecessors, the Empire's economic health rested primarily on agriculture. In addition, long-distance trade flourished, reaching as far north as  At the start of Justinian I's reign he had inherited a surplus 28,800,000 ''solidi'' (400,000 pounds of gold) in the imperial treasury from Anastasius I and

At the start of Justinian I's reign he had inherited a surplus 28,800,000 ''solidi'' (400,000 pounds of gold) in the imperial treasury from Anastasius I and

During the 530s, it seemed to many that God had abandoned the Christian Roman Empire. There were noxious fumes in the air and the Sun, while still providing daylight, refused to give much heat. The

During the 530s, it seemed to many that God had abandoned the Christian Roman Empire. There were noxious fumes in the air and the Sun, while still providing daylight, refused to give much heat. The

The Anecdota or Secret History

'. Edited by H. B. Dewing. 7 vols.

Procopii Caesariensis opera omnia

'. Edited by J. Haury; revised by G. Wirth. 3 vols. Leipzig:

Chronicle

', translated by Elizabeth Jeffreys, Michael Jeffreys & Roger Scott, 1986. Byzantina Australiensia 4 (Melbourne: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies) *

St Justinian the Emperor

Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion (14 November)

* ttp://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0023/html/lewis_e_244.html Lewis E 244 Infortiatum at OPenn

The ''Buildings'' of Procopius in English translation.

''The Roman Law Library'' by Professor Yves Lassard and Alexandr Koptev

Lecture series covering 12 Byzantine Rulers, including Justinian

– by Lars Brownworth

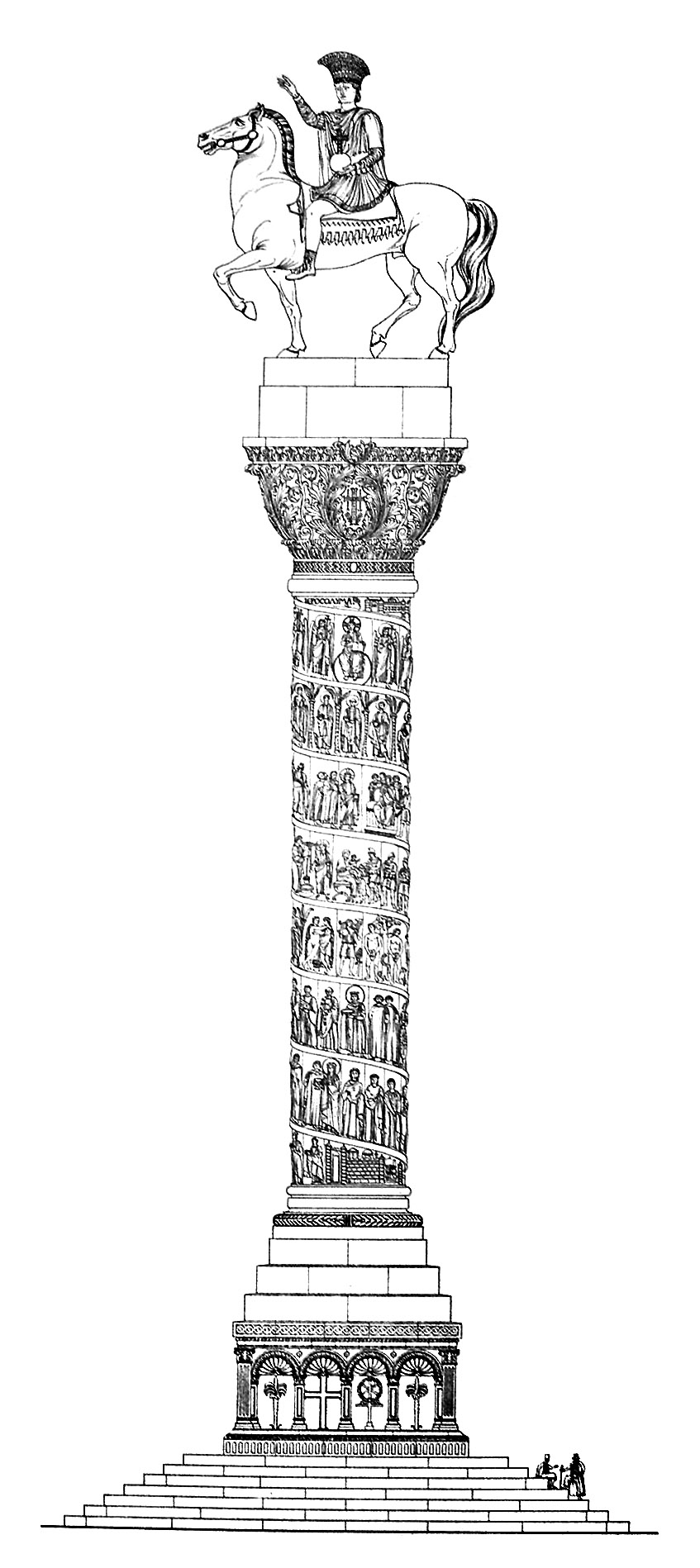

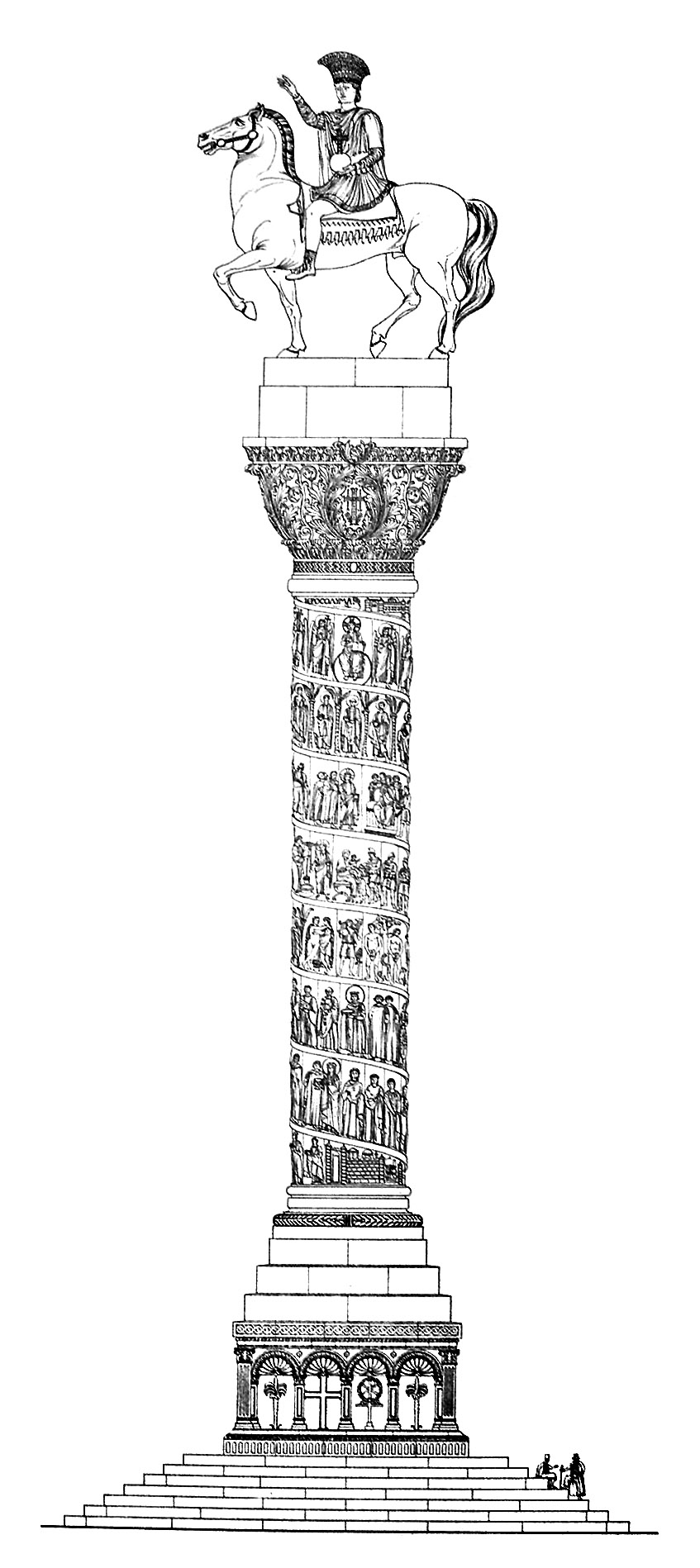

* ttp://www.byzantium1200.com/justinia.html Reconstruction of column of Justinian in Constantinople

Opera Omnia by Migne ''Patrologia Graeca'' with analytical indexes

Annotated Justinian Code (University of Wyoming website)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Justinian 01 480s births 565 deaths 6th-century Christian saints 6th-century Byzantine emperors 6th-century Roman consuls Medieval legislators Burials at the Church of the Holy Apostles Gothicus Maximus Thracian people Illyrian people Justinian dynasty Theocrats Christian royal saints Pre-Reformation saints of the Lutheran liturgical calendar People of the Roman–Sasanian Wars People from Zelenikovo Municipality Military saints Last of the Romans Eastern Orthodox royal saints Roman Catholic royal saints Iberian War Lazic War Illyrian emperors 6th-century Byzantine people

Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii

''Renovatio imperii Romanorum'' ("renewal of the empire of the Romans") was a formula declaring an intention to restore or revive the Roman Empire. The formula (and variations) was used by several emperors of the Carolingian and Ottonian dynasties ...

'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was expressed by the partial recovery of the territories of the defunct Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

. His general, Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

, swiftly conquered the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa. Subsequently, Belisarius, Narses

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

, and other generals conquered the Ostrogothic kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic peoples, Germanic Ostrogoths in Italian peninsula, Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the ...

, restoring Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to the empire after more than half a century of rule by the Ostrogoths. The praetorian prefect Liberius reclaimed the south of the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, establishing the province of Spania

Spania ( la, Provincia Spaniae) was a province of the Eastern Roman Empire from 552 until 624 in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. It was established by the Emperor Justinian I in an effort to restore the western prov ...

. These campaigns re-established Roman control over the western Mediterranean, increasing the Empire's annual revenue by over a million ''solidi''. During his reign, Justinian also subdued the ''Tzani

The Macrones ( ka, მაკრონები) ( grc, Μάκρωνες, ''Makrōnes'') were an ancient Colchian tribe in the east of Pontus, about the Moschici Mountains (modern Yalnizçam Dağlari, Turkey). The name is allegedly derived fro ...

'', a people on the east coast of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

that had never been under Roman rule before. He engaged the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

in the east during Kavad I

Kavad I ( pal, 𐭪𐭥𐭠𐭲 ; 473 – 13 September 531) was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 488 to 531, with a two or three-year interruption. A son of Peroz I (), he was crowned by the nobles to replace his deposed and unpopular un ...

's reign, and later again during Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

's reign; this second conflict was partially initiated due to his ambitions in the west.

A still more resonant aspect of his legacy was the uniform rewriting of Roman law, the ''Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

'', which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. His reign also marked a blossoming of Eastern roman (Byzantine) culture, and his building program yielded works such as the Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

.

Life

Justinian was born inTauresium

Tauresium (Latin; mk, Тауресиум), today as Gradište ( mk, Градиште), is an archaeological site in North Macedonia, approximately southeast of the capital Skopje. Tauresium is the birthplace of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (ca. ...

, Dardania, probably in 482. A native speaker of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

(possibly the last Roman emperor to be one), he came from a peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

family believed to have been of Illyro-Roman

Illyro-Roman is a term used in historiography and anthropological studies for the Romanized Illyrians within the ancient Roman provinces of Illyricum, Moesia, Pannonia and Dardania. The term 'Illyro-Roman' can also be used to describe the Roman ...

or Thraco-Roman The term Thraco-Roman describes the Romanized culture of Thracians under the rule of the Roman Empire.

The Odrysian kingdom of Thrace became a Roman client kingdom c. 20 BC, while the Greek city-states on the Black Sea coast came under Roman contro ...

origin. The name ''Iustinianus'', which he took later, is indicative of adoption by his uncle Justin

Justin may refer to: People

* Justin (name), including a list of persons with the given name Justin

* Justin (historian), a Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire

* Justin I (c. 450–527), or ''Flavius Iustinius Augustus'', Eastern Rom ...

. During his reign, he founded Justiniana Prima

Justiniana Prima (Latin: , sr, Јустинијана Прима, Justinijana Prima) was an Eastern Roman city that existed from 535 to 615, and currently an archaeological site, known as or ''Caričin Grad'' ( sr, Царичин Град), nea ...

not far from his birthplace. His mother was Vigilantia Vigilantia ( el, Βιγλεντία, born 490) was a sister of Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), and mother to his successor Justin II (r. 565–574).

Name

The name "Vigilantia" is Latin for "alertness, wakefulness". Itself deriving ...

, the sister of Justin. Justin, who was commander of one of the imperial guard units (the Excubitors

The Excubitors ( la, excubitores or , , i.e. 'sentinels'; transcribed into Greek as , ) were founded in as an imperial guard unit by the Byzantine emperor Leo I the Thracian. The 300-strong force, originally recruited from among the warlike moun ...

) before he became emperor, adopted Justinian, brought him to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, and ensured the boy's education. As a result, Justinian was well educated in jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, and Roman history. Justinian served as a ''candidatus'', one of 40 men selected from the ''scholae palatinae'' to serve as the emperor's personal bodyguard. The chronicler John Malalas

John Malalas ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Malálas''; – 578) was a Byzantine chronicler from Antioch (now Antakya, Turkey).

Life

Malalas was of Syrian descent, and he was a native speaker of Syriac who learned how to write in Greek later in ...

, who lived during the reign of Justinian, describes his appearance as short, fair-skinned, curly-haired, round-faced, and handsome. Another contemporary historian, Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gener ...

, compares Justinian's appearance to that of tyrannical Emperor Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

, although this is probably slander.''Cambridge Ancient History'' p. 65

When Emperor Anastasius died in 518, Justin was proclaimed the new emperor with significant help from Justinian. Justinian showed a lot of ambition, and several sources claim that he was functioning as virtual regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

long before Justin made him associate emperor, although there is no conclusive evidence of this. As Justin became senile near the end of his reign, Justinian became the ''de facto'' ruler. Following the general Vitalian's assassination in 520 (orchestrated by Justinian and Justin), Justinian was appointed consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

and commander of the army of the east. Justinian remained Justin's close confidant, and in 525 was granted the titles of ''nobilissimus

''Nobilissimus'' (Latin for "most noble"), in Byzantine Greek ''nōbelissimos'' (Greek: νωβελίσσιμος),. was one of the highest imperial titles in the late Roman and Byzantine empires. The feminine form of the title was ''nobilissima' ...

'' and ''caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

'' (heir-apparent). He was crowned co-emperor on 1 April 527,Marcellinus Comes Marcellinus Comes (Greek: Μαρκελλίνος ό Κόμης, died c. 534) was a Latin chronicler of the Eastern Roman Empire. An Illyrian by birth, he spent most of his life at the court of Constantinople. His only surviving work, the ''Chronicl ...

br>527''

Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

'' 527

__NOTOC__

Year 527 ( DXXVII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Mavortius without colleague (or, less frequently, year ...

; Theophanes Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before taking ...

AM 6019. and became sole ruler after Justin's death on 1 August 527.

As a ruler, Justinian showed great energy. He was known as "the emperor who never sleeps" for his work habits. Nevertheless, he seems to have been amiable and easy to approach. Around 525, he married his mistress, Theodora

Theodora is a given name of Greek origin, meaning "God's gift".

Theodora may also refer to:

Historical figures known as Theodora

Byzantine empresses

* Theodora (wife of Justinian I) ( 500 – 548), saint by the Orthodox Church

* Theodora of ...

, in Constantinople. She was by profession an actress and some twenty years his junior. In earlier times, Justinian could not have married her owing to her class, but his uncle, Emperor Justin I, had passed a law lifting restrictions on marriages with ex-actresses. Though the marriage caused a scandal, Theodora would become very influential in the politics of the Empire. Other talented individuals included Tribonian

Tribonian ( Greek: Τριβωνιανός rivonia'nos c. 485?–542) was a notable Byzantine jurist and advisor, who during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I, supervised the revision of the legal code of the Byzantine Empire. He has been descri ...

, his legal adviser; Peter the Patrician

Peter the Patrician ( la, Petrus Patricius, el, , ''Petros ho Patrikios''; –565) was a senior Byzantine official, diplomat, and historian. A well-educated and successful lawyer, he was repeatedly sent as envoy to Ostrogothic Italy in the pr ...

, the diplomat and long-time head of the palace bureaucracy; Justinian's finance ministers John the Cappadocian

John the Cappadocian ( el, Ἰωάννης ὁ Καππαδόκης) ('' fl.'' 530s, living 548) was a praetorian prefect of the East (532–541) in the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). He was also a patrician and the ''c ...

and Peter Barsymes Peter Barsymes ( la, Petrus Barsumes, el, Πέτρος Βαρσύμης, fl. ca. 540 – ca. 565) was a senior Byzantine official, associated chiefly with public finances and administration, under Byzantine emperor Justinian I ().

Aside from cont ...

, who managed to collect taxes more efficiently than any before, thereby funding Justinian's wars; and finally, his prodigiously talented generals, Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

and Narses

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

.

Justinian's rule was not universally popular; early in his reign he nearly lost his throne during the Nika riots

The Nika riots ( el, Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα, translit=Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the ...

, and a conspiracy against the emperor's life by dissatisfied businessmen was discovered as late as 562. Justinian was struck by the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

in the early 540s but recovered. Theodora died in 548 at a relatively young age, possibly of cancer; Justinian outlived her by nearly twenty years. Justinian, who had always had a keen interest in theological matters and actively participated in debates on Christian doctrine, became even more devoted to religion during the later years of his life. He died on 14 November 565, childless. He was succeeded by Justin II

Justin II ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, Ioustînos; died 5 October 578) or Justin the Younger ( la, Iustinus minor) was Eastern Roman Emperor from 565 until 578. He was the nephew of Justinian I and the husband of Sophia, the ...

, who was the son of his sister Vigilantia Vigilantia ( el, Βιγλεντία, born 490) was a sister of Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), and mother to his successor Justin II (r. 565–574).

Name

The name "Vigilantia" is Latin for "alertness, wakefulness". Itself deriving ...

and married to Sophia, the niece of Theodora. Justinian's body was entombed in a specially built mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles

The Church of the Holy Apostles ( el, , ''Agioi Apostoloi''; tr, Havariyyun Kilisesi), also known as the ''Imperial Polyándreion'' (imperial cemetery), was a Byzantine Eastern Orthodox church in Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman E ...

until it was desecrated and robbed during the pillage of the city in 1204 by the Latin States of the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

.

Reign

Legislative activities

Justinian achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, particularly through the complete revision of all

Justinian achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, particularly through the complete revision of all Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

, something that had not previously been attempted. The total of Justinian's legislation is known today as the ''Corpus juris civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

''. It consists of the ''Codex Justinianeus

The Code of Justinian ( la, Codex Justinianus, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Byzantine Empire, Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. ...

'', the ''Digesta'' or ''Pandectae

The ''Digest'', also known as the Pandects ( la, Digesta seu Pandectae, adapted from grc, πανδέκτης , "all-containing"), is a name given to a compendium or digest of juristic writings on Roman law compiled by order of the Byzantine e ...

'', the '' Institutiones'', and the ''Novellae In Roman law, a novel ( la, novella constitutio, "new decree"; gr, νεαρά, neara) is a new decree or edict, in other words a new law. The term was used from the fourth century AD onwards and was specifically used for laws issued after the publi ...

''.

Early in his reign, Justinian had appointed the ''quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

'' Tribonian

Tribonian ( Greek: Τριβωνιανός rivonia'nos c. 485?–542) was a notable Byzantine jurist and advisor, who during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I, supervised the revision of the legal code of the Byzantine Empire. He has been descri ...

to oversee this task. The first draft of the ''Codex Justinianeus

The Code of Justinian ( la, Codex Justinianus, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Byzantine Empire, Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. ...

'', a codification of imperial constitutions from the 2nd century onward, was issued on 7 April 529. (The final version appeared in 534.) It was followed by the ''Digesta'' (or ''Pandectae

The ''Digest'', also known as the Pandects ( la, Digesta seu Pandectae, adapted from grc, πανδέκτης , "all-containing"), is a name given to a compendium or digest of juristic writings on Roman law compiled by order of the Byzantine e ...

''), a compilation of older legal texts, in 533, and by the '' Institutiones'', a textbook explaining the principles of law. The ''Novellae In Roman law, a novel ( la, novella constitutio, "new decree"; gr, νεαρά, neara) is a new decree or edict, in other words a new law. The term was used from the fourth century AD onwards and was specifically used for laws issued after the publi ...

'', a collection of new laws issued during Justinian's reign, supplements the ''Corpus''. As opposed to the rest of the corpus, the ''Novellae'' appeared in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, the common language of the Eastern Empire.

The ''Corpus'' forms the basis of Latin jurisprudence (including ecclesiastical Canon Law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

) and, for historians, provides a valuable insight into the concerns and activities of the later Roman Empire. As a collection it gathers together the many sources in which the ''leges'' (laws) and the other rules were expressed or published: proper laws, senatorial

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the eld ...

consults (''senatusconsulta''), imperial decrees, case law

Case law, also used interchangeably with common law, is law that is based on precedents, that is the judicial decisions from previous cases, rather than law based on constitutions, statutes, or regulations. Case law uses the detailed facts of a l ...

, and jurists' opinions and interpretations (''responsa prudentium'').

Tribonian's code ensured the survival of Roman law. It formed the basis of later Byzantine law, as expressed in the ''Basilika

The ''Basilika'' was a collection of laws completed c. 892 AD in Constantinople by order of the Eastern Roman emperor Leo VI the Wise during the Macedonian dynasty. This was a continuation of the efforts of his father, Basil I, to simplify and ...

'' of Basil I

Basil I, called the Macedonian ( el, Βασίλειος ὁ Μακεδών, ''Basíleios ō Makedṓn'', 811 – 29 August 886), was a Byzantine Emperor who reigned from 867 to 886. Born a lowly peasant in the theme of Macedonia, he rose in the ...

and Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI, called the Wise ( gr, Λέων ὁ Σοφός, Léōn ho Sophós, 19 September 866 – 11 May 912), was Byzantine Emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty (although his parentage is unclear), he was very well r ...

. The only western province where the Justinianic code was introduced was Italy (after the conquest by the so-called Pragmatic Sanction of 554), from where it was to pass to Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

in the 12th century and become the basis of much Continental European law code, which was eventually spread by European empires to the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and beyond in the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

. It eventually passed to Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

where it appeared in Slavic editions, and it also passed on to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. It remains influential to this day.

He passed laws to protect prostitutes from exploitation and women from being forced into prostitution

Forced prostitution, also known as involuntary prostitution or compulsory prostitution, is prostitution or sexual slavery that takes place as a result of coercion by a third party. The terms "forced prostitution" or "enforced prostitution" appea ...

. Rapists were treated severely. Further, by his policies: women charged with major crimes should be guarded by other women to prevent sexual abuse; if a woman was widowed, her dowry should be returned; and a husband could not take on a major debt without his wife giving her consent twice.

Family legislation also revealed a greater concern for the interests of children. This was particularly so with respect to children born out of wedlock. The law under Justinian also reveals a striking interest in child neglect issues. Justinian protected the rights of children whose parents remarried and produced more offspring, or who simply separated and abandoned their offspring, forcing them to beg.

Justinian discontinued the regular appointment of Consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

in 541.

Nika riots

Justinian's habit of choosing efficient but unpopular advisers nearly cost him his throne early in his reign. In January 532, partisans of thechariot racing

Chariot racing ( grc-gre, ἁρματοδρομία, harmatodromia, la, ludi circenses) was one of the most popular ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine sports. In Greece, chariot racing played an essential role in aristocratic funeral games from ...

factions in Constantinople, normally rivals, united against Justinian in a revolt that has become known as the Nika riots

The Nika riots ( el, Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα, translit=Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the ...

. They forced him to dismiss Tribonian

Tribonian ( Greek: Τριβωνιανός rivonia'nos c. 485?–542) was a notable Byzantine jurist and advisor, who during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I, supervised the revision of the legal code of the Byzantine Empire. He has been descri ...

and two of his other ministers, and then attempted to overthrow Justinian himself and replace him with the senator Hypatius, who was a nephew of the late emperor Anastasius. While the crowd was rioting in the streets, Justinian considered fleeing the capital by sea, but eventually decided to stay, apparently on the prompting of his wife Theodora

Theodora is a given name of Greek origin, meaning "God's gift".

Theodora may also refer to:

Historical figures known as Theodora

Byzantine empresses

* Theodora (wife of Justinian I) ( 500 – 548), saint by the Orthodox Church

* Theodora of ...

, who refused to leave. In the next two days, he ordered the brutal suppression of the riots by his generals Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

and Mundus. Procopius relates that 30,000J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', 200 unarmed civilians were killed in the Hippodrome. On Theodora's insistence, and apparently against his own judgment, Justinian had Anastasius' nephews executed.

The destruction that took place during the revolt provided Justinian with an opportunity to tie his name to a series of splendid new buildings, most notably the architectural innovation of the domed Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

.

Military activities

One of the most spectacular features of Justinian's reign was the recovery of large stretches of land around the Western Mediterranean basin that had slipped out of Imperial control in the 5th century. As a Christian Roman emperor, Justinian considered it his divine duty to restore theRoman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

to its ancient boundaries. Although he never personally took part in military campaigns, he boasted of his successes in the prefaces to his laws and had them commemorated in art. The re-conquests were in large part carried out by his general Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

.

War with the Sassanid Empire, 527–532

From his uncle, Justinian inherited ongoing hostilities with theSassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

. In 530 the Persian forces suffered a double defeat at Dara

Dara is a given name used for both males and females, with more than one origin. Dara is found in the Bible's Old Testament Books of Chronicles. Dara �רעwas a descendant of Judah (son of Jacob). (The Bible. 1 Chronicles 2:6). Dara (also known ...

and Satala

Located in Turkey, the settlement of Satala ( xcl, Սատաղ ''Satał'', grc, Σάταλα), according to the ancient geographers, was situated in a valley surrounded by mountains, a little north of the Euphrates, where the road from Trapezu ...

, but the next year saw the defeat of Roman forces under Belisarius near Callinicum. Justinian then tried to make alliance with the Axumites of Ethiopia and the Himyarites

The Himyarite Kingdom ( ar, مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, he, ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar ( ar, حِمْيَر, ''Ḥimyar'', / 𐩹𐩧𐩺𐩵𐩬) (floruit, fl. 110 BCE–520s Common Era, CE), historically referre ...

of Yemen against the Persians, but this failed. When king Kavadh I of Persia

Kavad I ( pal, 𐭪𐭥𐭠𐭲 ; 473 – 13 September 531) was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 488 to 531, with a two or three-year interruption. A son of Peroz I (), he was crowned by the nobles to replace his deposed and unpopular un ...

died (September 531), Justinian concluded an " Eternal Peace" (which cost him 11,000 pounds of gold)J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', p. 195. with his successor Khosrau I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

(532). Having thus secured his eastern frontier, Justinian turned his attention to the West, where Germanic kingdoms had been established in the territories of the former Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

.

Conquest of North Africa, 533–534

The first of the western kingdoms Justinian attacked was that of theVandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. King Hilderic

Hilderic (460s – 533) was the penultimate king of the Vandals and Alans in North Africa in Late Antiquity (523–530). Although dead by the time the Vandal Kingdom was overthrown in 534, he nevertheless played a key role in that event.

Biog ...

, who had maintained good relations with Justinian and the North African Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

clergy, had been overthrown by his cousin Gelimer

Gelimer (original form possibly Geilamir, 480–553), King of the Vandals and Alans (530–534), was the last Germanic ruler of the North African Kingdom of the Vandals. He became ruler on 15 June 530 after deposing his first cousin twice rem ...

in 530 A.D. Imprisoned, the deposed king appealed to Justinian. Justinian protested Gelimer's actions, demanding that Gelimer return the kingdom to Hilderic. Gelimer replied, in effect, that Justinian had no authority to make these demands. Angered at this response, Justinian quickly concluded his ongoing war with the Sassanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

and prepared an expedition against the Vandals in 533.

In 533, Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

sailed to Africa with a fleet of 92 dromon

A dromon (from Greek δρόμων, ''dromōn'', "runner") was a type of galley and the most important warship of the Byzantine navy from the 5th to 12th centuries AD, when they were succeeded by Italian-style galleys. It was developed from the an ...

s, escorting 500 transports carrying an army of about 15,000 men, as well as a number of barbarian troops. They landed at Caput Vada (modern Ras Kaboudia) in modern Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

. They defeated the Vandals, who were caught completely off guard, at Ad Decimum

The Battle of Ad Decimum took place on September 13, 533 between the armies of the Vandals, commanded by King Gelimer, and the Byzantine Empire, under the command of General Belisarius. This event and events in the following year are sometimes ...

on 14 September 533 and Tricamarum in December; Belisarius took Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

. King Gelimer

Gelimer (original form possibly Geilamir, 480–553), King of the Vandals and Alans (530–534), was the last Germanic ruler of the North African Kingdom of the Vandals. He became ruler on 15 June 530 after deposing his first cousin twice rem ...

fled to Mount Pappua in Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

, but surrendered the next spring. He was taken to Constantinople, where he was paraded in a triumph

The Roman triumph (Latin triumphus) was a celebration for a victorious military commander in ancient Rome. For later imitations, in life or in art, see Trionfo. Numerous later uses of the term, up to the present, are derived directly or indirectl ...

. Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

and Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

, and the stronghold Septem Fratres near Mons Calpe

The Rock of Gibraltar (from the Arabic name Jabel-al-Tariq) is a monolithic limestone promontory located in the British territory of Gibraltar, near the southwestern tip of Europe on the Iberian Peninsula, and near the entrance to the Mediterr ...

(later named Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

) were recovered in the same campaign.

In this war, the contemporary

In this war, the contemporary Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gener ...

remarks that Africa was so entirely depopulated that a person might travel several days without meeting a human being, and he adds, "it is no exaggeration to say, that in the course of the war 5,000,000 perished by the sword, and famine, and pestilence."

An African prefecture, centered in Carthage, was established in April 534, but it would teeter on the brink of collapse during the next 15 years, amidst warfare with the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

and military mutinies. The area was not completely pacified until 548, but remained peaceful thereafter and enjoyed a measure of prosperity. The recovery of Africa cost the empire about 100,000 pounds of gold.

War in Italy, first phase, 535–540

As in Africa, dynastic struggles in

As in Africa, dynastic struggles in Ostrogothic Italy

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great killed and replaced Odoacer, ...

provided an opportunity for intervention. The young king Athalaric

Athalaric (; 5162 October 534) was the king of the Ostrogoths in Italy between 526 and 534. He was a son of Eutharic and Amalasuntha, the youngest daughter of Theoderic the Great, whom Athalaric succeeded as king in 526.

As Athalaric was only ...

had died on 2 October 534, and a usurper, Theodahad

Theodahad, also known as Thiudahad ( la, Flavius Theodahatus , Theodahadus, Theodatus; 480 – December 536) was king of the Ostrogoths from 534 to 536.

Early life

Born at in Tauresium, Theodahad was a nephew of Theodoric the Great through ...

, had imprisoned queen Amalasuintha

Amalasuintha (495 – 30 April 534/535) was a ruler of Ostrogothic Kingdom from 526 to 535. She ruled first as regent for her son and thereafter as queen on throne. A regent is "a person who governs a kingdom in the minority, absence, or disabili ...

, Theodoric

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name ...

's daughter and mother of Athalaric, on the island of Martana in Lake Bolsena

Lake Bolsena ( it, Lago di Bolsena) is a lake of volcanic origin in the northern part of the province of Viterbo called ''Alto Lazio'' ("Upper Latium") or ''Tuscia'' in central Italy. It is the largest volcanic lake in Europe. Roman historic ...

, where he had her assassinated in 535. Thereupon Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

, with 7,500 men,J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', 215 invaded Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

(535) and advanced into Italy, sacking Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and capturing Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

on 9 December 536. By that time Theodahad

Theodahad, also known as Thiudahad ( la, Flavius Theodahatus , Theodahadus, Theodatus; 480 – December 536) was king of the Ostrogoths from 534 to 536.

Early life

Born at in Tauresium, Theodahad was a nephew of Theodoric the Great through ...

had been deposed by the Ostrogothic

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

army, who had elected Vitigis

Vitiges or Vitigis or Witiges (died 542) was king of Ostrogothic Italy from 536 to 540.

He succeeded to the throne of Italy in the early stages of the Gothic War of 535–554, as Belisarius had quickly captured Sicily the previous year and ...

as their new king. He gathered a large army and besieged Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

from February 537 to March 538 without being able to retake the city.

Justinian sent another general, Narses

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

, to Italy, but tensions between Narses and Belisarius hampered the progress of the campaign. Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

was taken, but was soon recaptured and razed by the Ostrogoths. Justinian recalled Narses

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

in 539. By then the military situation had turned in favour of the Romans, and in 540 Belisarius reached

''Reached'' is a 2012 young adult dystopian novel by Allyson Braithwaite Condie and is the final novel in the ''Matched Trilogy,'' preceded by '' Matched'' and '' Crossed''. The novel was published on November 13, 2012, by Dutton Juvenile and wa ...

the Ostrogothic capital Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the cap ...

. There he was offered the title of Western Roman Emperor by the Ostrogoths at the same time that envoys of Justinian were arriving to negotiate a peace that would leave the region north of the Po River

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ligurian language (ancient), Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira (river), Mair ...

in Gothic hands. Belisarius feigned acceptance of the offer, entered the city in May 540, and reclaimed it for the Empire. Then, having been recalled by Justinian, Belisarius returned to Constantinople, taking the captured Vitigis

Vitiges or Vitigis or Witiges (died 542) was king of Ostrogothic Italy from 536 to 540.

He succeeded to the throne of Italy in the early stages of the Gothic War of 535–554, as Belisarius had quickly captured Sicily the previous year and ...

and his wife Matasuntha

Mataswintha, also spelled Matasuintha, Matasuentha, Mathesuentha, Matasvintha, or Matasuntha, (fl. 550), was a daughter of Eutharic and Amalasuintha. She was a sister of Athalaric, King of the Ostrogoths. Their maternal grandparents were Theodoric ...

with him.

War with the Sassanid Empire, 540–562

Belisarius had been recalled in the face of renewed hostilities by the

Belisarius had been recalled in the face of renewed hostilities by the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

. Following a revolt against the Empire in Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

in the late 530s and possibly motivated by the pleas of Ostrogothic

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

ambassadors, King Khosrau I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

broke the "Eternal Peace" and invaded Roman territory in the spring of 540. He first sacked Beroea

Beroea (or Berea) was an ancient city of the Hellenistic period and Roman Empire now known as Veria (or Veroia) in Macedonia, Northern Greece. It is a small city on the eastern side of the Vermio Mountains north of Mount Olympus. The town is menti ...

and then Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

(allowing the garrison of 6,000 men to leave the city),J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', 229 besieged Daras

Dara or Daras ( el, Δάρας, syr, ܕܪܐ) was an important East Roman Empire, East Roman fortress city in northern Mesopotamia on the border with the Sassanid Empire. Because of its great strategic importance, it featured prominently in the R ...

, and then went on to attack the Byzantine base in the small but strategically significant satellite kingdom of Lazica

Lazica ( ka, ეგრისი, ; lzz, ლაზიკა, ; grc-gre, Λαζική, ; fa, لازستان, ; hy, Եգեր, ) was the Latin name given to the territory of Colchis during the Roman/Byzantine period, from about the 1st centur ...

near the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

as requested by its discontented king Gubazes, exacting tribute from the towns he passed along his way. He forced Justinian I to pay him 5,000 pounds of gold, plus 500 pounds of gold more each year.

Belisarius arrived in the East in 541, but after some success, was again recalled to Constantinople in 542. The reasons for his withdrawal are not known, but it may have been instigated by rumours of his disloyalty reaching the court.

The outbreak of the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

coupled with a rebellion in Persia brought Khosrow I's offensives to a halt. Exploiting this, Justinian ordered all the forces in the East to invade Persian Armenia, but the 30,000-strong Byzantine force was defeated by a small force at Anglon.J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', 235 The next year, Khosrau unsuccessfully besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

the major city of Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

. Both parties made little headway, and in 545 a truce was agreed upon for the southern part of the Roman-Persian frontier. After that, the Lazic War

The Lazic War, also known as the Colchidian War or in Georgian historiography as the Great War of Egrisi was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Sasanian Empire for control of the ancient Georgian region of Lazica. The Lazic War lasted fo ...

in the North continued for several years: the Lazic king switched to the Byzantine side, and in 549 Justinian sent Dagisthaeus

Dagisthaeus (, ''Dagisthaîos'') was a 6th-century Eastern Roman military commander, probably of Gothic origin, in the service of the emperor Justinian I.

Dagisthaeus was possibly a descendant of the Ostrogothic chieftain Dagistheus.* In 548, Da ...

to recapture Petra, but he faced heavy resistance and the siege was relieved by Sasanian reinforcements. Justinian replaced him with Bessas

Bessas is a commune in the Ardèche department in southern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Ardèche department

The following is a list of the 335 communes of the Ardèche department of France.

The communes cooperate in th ...

, who was under a cloud after the loss of Rome in 546, but he managed to capture and dismantle Petra in 551. The war continued for several years until a second truce in 557, followed by a Fifty Years' Peace in 562. Under its terms, the Persians agreed to abandon Lazica in exchange for an annual tribute of 400 or 500 pounds of gold (30,000 ''solidi'') to be paid by the Romans.

War in Italy, second phase, 541–554

While military efforts were directed to the East, the situation in Italy took a turn for the worse. Under their respective kingsIldibad Ildibad (sometimes rendered Hildebad or Heldebadus) (died 541) was a king of the Ostrogoths in Italy in 540–541.

Biography

Ildibad was a nephew of Theudis, an Ostrogoth king of the Visigoths in Spain. This relationship led Peter Heather to sugges ...

and Eraric Eraric (died 541) was briefly King of the Ostrogoths, elected as the most distinguished among the Rugians in the confederation of the Ostrogoths. The Goths were vexed at the presumption of the Rugians, but nevertheless they recognized Eraric. He sum ...

(both murdered in 541) and especially Totila

Totila, original name Baduila (died 1 July 552), was the penultimate King of the Ostrogoths, reigning from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of the Gothic War, recovering by 543 almost all the t ...

, the Ostrogoths made quick gains. After a victory

The term victory (from Latin ''victoria'') originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal Duel, combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitu ...

at Faenza

Faenza (, , ; rgn, Fènza or ; la, Faventia) is an Italian city and comune of 59,063 inhabitants in the province of Ravenna, Emilia-Romagna, situated southeast of Bologna.

Faenza is home to a historical manufacture of majolica-ware glazed eart ...

in 542, they reconquered the major cities of Southern Italy and soon held almost the entire Italian peninsula. Belisarius was sent back to Italy late in 544 but lacked sufficient troops and supplies. Making no headway, he was relieved of his command in 548. Belisarius succeeded in defeating a Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

fleet of 200 ships. During this period the city of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

changed hands three more times, first taken and depopulated by the Ostrogoths in December 546, then reconquered by the Byzantines in 547, and then again by the Goths in January 550. Totila also plundered Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and attacked Greek coastlines.

Finally, Justinian dispatched a force of approximately 35,000 men (2,000 men were detached and sent to invade southern

Finally, Justinian dispatched a force of approximately 35,000 men (2,000 men were detached and sent to invade southern Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

) under the command of Narses

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

.J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', 251 The army reached Ravenna in June 552 and defeated the Ostrogoths decisively within a month at the battle of Busta Gallorum

At the Battle of Taginae (also known as the Battle of Busta Gallorum) in June/July 552, the forces of the Byzantine Empire under Narses broke the power of the Ostrogoths in Italy, and paved the way for the temporary Byzantine reconquest of the It ...

in the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

, where Totila was slain. After a second battle at Mons Lactarius in October that year, the resistance of the Ostrogoths was finally broken. In 554, a large-scale Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

invasion was defeated at Casilinum Casilinum was an ancient city of Campania, Italy, situated some 3 miles north-west of the ancient Capua. The position of Casilinum at the junction of the Via Appia and Via Latina, at their crossing of the river Volturnus by a still-existing three-ar ...

, and Italy was secured for the Empire, though it would take Narses several years to reduce the remaining Gothic strongholds. At the end of the war, Italy was garrisoned with an army of 16,000 men.J. Norwich, ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', 233 The recovery of Italy cost the empire about 300,000 pounds of gold. Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gener ...

estimated 15,000,000 Goths died.

Other campaigns

In addition to the other conquests, the Empire established a presence in

In addition to the other conquests, the Empire established a presence in Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

, when the usurper Athanagild

Athanagild ( 517 – December 567) was Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania. He had rebelled against his predecessor, Agila I, in 551. The armies of Agila and Athanagild met at Seville, where Agila met a second defeat. Following the death of ...

requested assistance in his rebellion against King Agila I

Agila, sometimes Agila I or Achila I (died March 554), was Visigoths, Visigothic Visigothic Kingdom, King of Hispania and Septimania (549 – March 554). Peter Heather notes that Agila's reign was during a period of civil war following the death of ...

. In 552, Justinian dispatched a force of 2,000 men; according to the historian Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Goths, Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history (''Romana ...

, this army was led by the octogenarian Liberius. The Byzantines took Cartagena and other cities on the southeastern coast and founded the new province of Spania

Spania ( la, Provincia Spaniae) was a province of the Eastern Roman Empire from 552 until 624 in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. It was established by the Emperor Justinian I in an effort to restore the western prov ...

before being checked by their former ally Athanagild, who had by now become king. This campaign marked the apogee of Byzantine expansion.

During Justinian's reign, the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

suffered from several incursions by the Turkic and Slavic peoples

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic language, Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout ...

who lived north of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. Here, Justinian resorted mainly to a combination of diplomacy and a system of defensive works. In 559 a particularly dangerous invasion of Sklavinoi and Kutrigurs

Kutrigurs were Turkic Eurasian nomads, nomadic equestrians who flourished on the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the 6th century AD. To their east were the similar Utigurs and both possibly were closely related to the Bulgars. They warred with the Byza ...

under their khan

Khan may refer to:

*Khan (inn), from Persian, a caravanserai or resting-place for a travelling caravan

*Khan (surname), including a list of people with the name

*Khan (title), a royal title for a ruler in Mongol and Turkic languages and used by ...

Zabergan Zabergan ( grc-x-medieval, Ζαβεργάν) was the chieftain of the Kutrigur Bulgar Huns, a nomadic people of the Pontic–Caspian steppe, after Sinnion. His name is Iranian, meaning full moon. Either under pressure from incoming Avars,; or in r ...

threatened Constantinople, but they were repulsed by the aged general Belisarius.

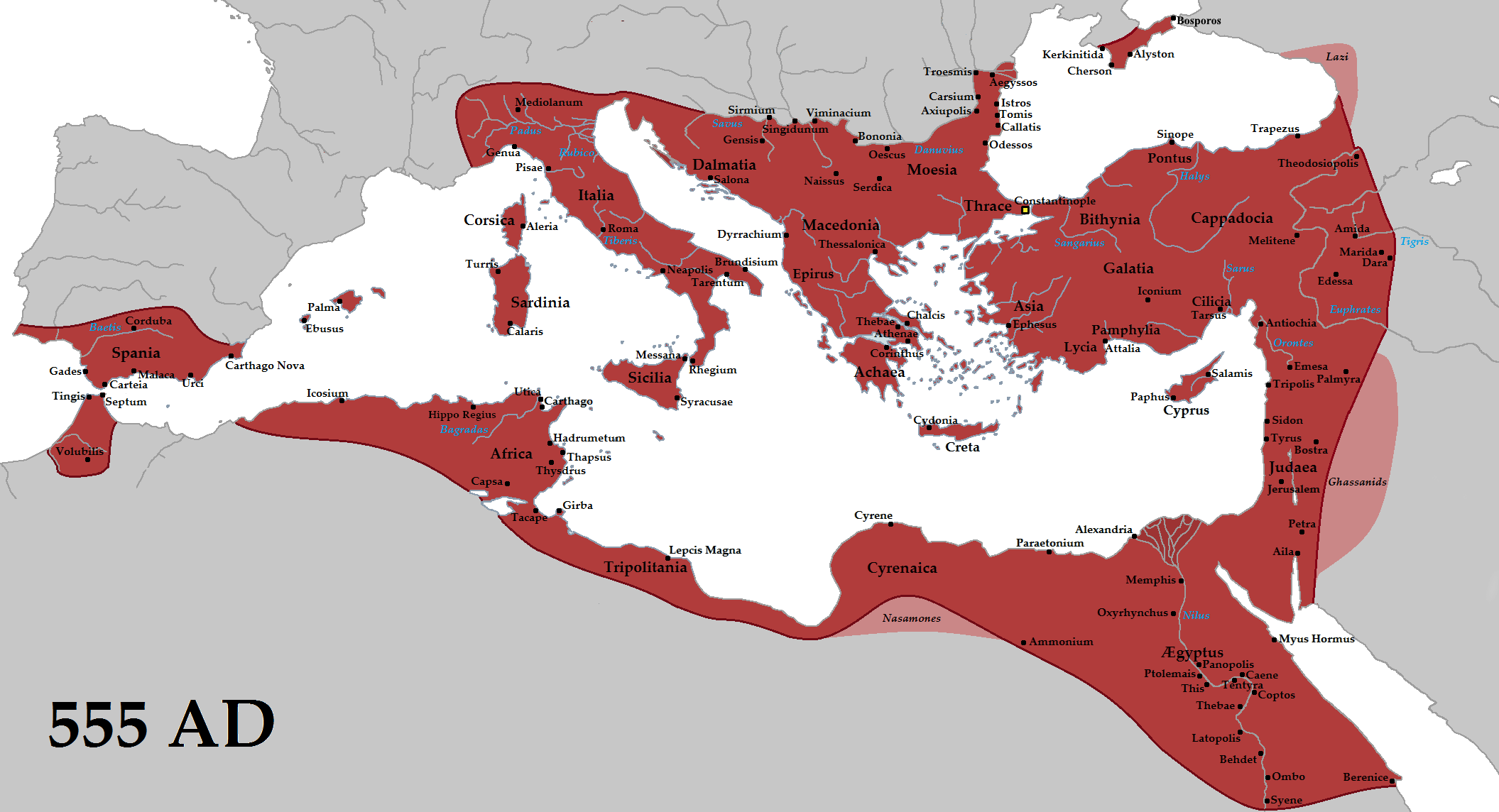

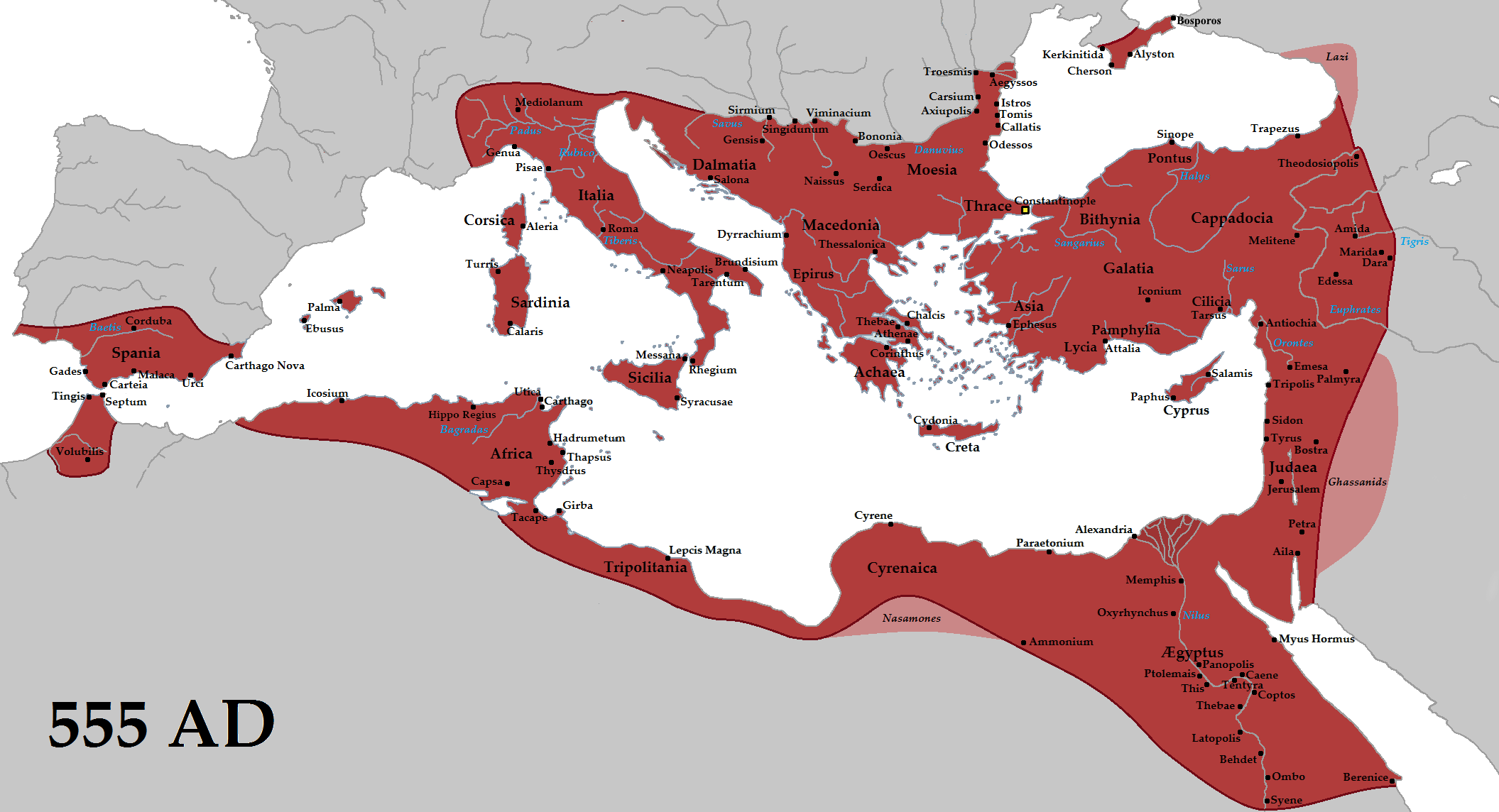

Results

Justinian's ambition to restore the Roman Empire to its former glory was only partly realized. In the West, the brilliant early military successes of the 530s were followed by years of stagnation. The dragging war with the Goths was a disaster for Italy, even though its long-lasting effects may have been less severe than is sometimes thought. The heavy taxes that the administration imposed upon Italian population were deeply resented. The final victory in Italy and the conquest of Africa and the coast of southernHispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

significantly enlarged the area of Byzantine influence and eliminated all naval threats to the empire, which in 555 reached its territorial zenith. Despite losing much of Italy soon after Justinian's death, the empire retained several important cities, including Rome, Naples, and Ravenna, leaving the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

as a regional threat. The newly founded province of Spania kept the Visigoths as a threat to Hispania alone and not to the western Mediterranean and Africa.

Events of the later years of his reign showed that Constantinople itself was not safe from barbarian incursions from the north, and even the relatively benevolent historian Menander Protector

Menander Protector (Menander the Guardsman, Menander the Byzantian; el, Μένανδρος Προτήκτωρ or Προτέκτωρ), Byzantine historian, was born in Constantinople in the middle of the 6th century AD. The little that is known of ...

felt the need to attribute the Emperor's failure to protect the capital to the weakness of his body in his old age. In his efforts to renew the Roman Empire, Justinian dangerously stretched its resources while failing to take into account the changed realities of 6th-century Europe.

Religious activities

Justinian saw the orthodoxy of his empire threatened by diverging religious currents, especiallyMonophysitism

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means "nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the incarn ...

, which had many adherents in the eastern provinces of Syria and Egypt. Monophysite doctrine, which maintains that Jesus Christ had one divine nature rather than a synthesis of divine and human nature, had been condemned as a heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

by the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

in 451, and the tolerant policies towards Monophysitism of Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

and Anastasius I had been a source of tension in the relationship with the bishops of Rome. Justin reversed this trend and confirmed the Chalcedonian doctrine, openly condemning the Monophysites. Justinian, who continued this policy, tried to impose religious unity on his subjects by forcing them to accept doctrinal compromises that might appeal to all parties, a policy that proved unsuccessful as he satisfied none of them.

Near the end of his life, Justinian became ever more inclined towards the Monophysite doctrine, especially in the form of Aphthartodocetism, but he died before being able to issue any legislation. The empress Theodora sympathized with the Monophysites and is said to have been a constant source of pro-Monophysite intrigues at the court in Constantinople in the earlier years. In the course of his reign, Justinian, who had a genuine interest in matters of theology, authored a small number of theological treatises.

Religious policy

As in his secular administration,despotism

Despotism ( el, Δεσποτισμός, ''despotismós'') is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot; but (as in an autocracy) societies which limit respect and ...

appeared also in the Emperor's ecclesiastical policy. He regulated everything, both in religion and in law. At the very beginning of his reign, he deemed it proper to promulgate by law the Church's belief in the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

and the Incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It refers to the conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or the appearance of a god as a human. If capitalized, it is the union of divinit ...

, and to threaten all heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

with the appropriate penalties, whereas he subsequently declared that he intended to deprive all disturbers of orthodoxy of the opportunity for such offense by due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

of law. He made the Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan creed the sole symbol of the Church and accorded legal force to the canons of the four ecumenical

Ecumenism (), also spelled oecumenism, is the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships among their churches and promote Christian unity. The adjec ...

councils. The bishops in attendance at the Council of Constantinople (536) The Council of Constantinople was a conference of the endemic synod held in Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, in May–June 536. It confirmed the deposition of the Patriarch Anthimus I of Constantinople and condemned three pro ...

recognized that nothing could be done in the Church contrary to the emperor's will and command, while, on his side, the emperor, in the case of the Patriarch Anthimus, reinforced the ban of the Church with temporal proscription. Justinian protected the purity of the church by suppressing heretics. He neglected no opportunity to secure the rights of the Church and clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, and to protect and extend monasticism

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role ...

. He granted the monks the right to inherit property from private citizens and the right to receive ''solemnia'', or annual gifts, from the Imperial treasury or from the taxes of certain provinces and he prohibited lay confiscation of monastic estates.

Although the despotic character of his measures is contrary to modern sensibilities, he was indeed a "nursing father" of the Church. Both the ''Codex'' and the ''Novellae'' contain many enactments regarding donations, foundations, and the administration of ecclesiastical property; election and rights of bishops, priests and abbots; monastic life, residential obligations of the clergy, conduct of divine service, episcopal jurisdiction, etc. Justinian also rebuilt the Church of Hagia Sophia