Edward Elgar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

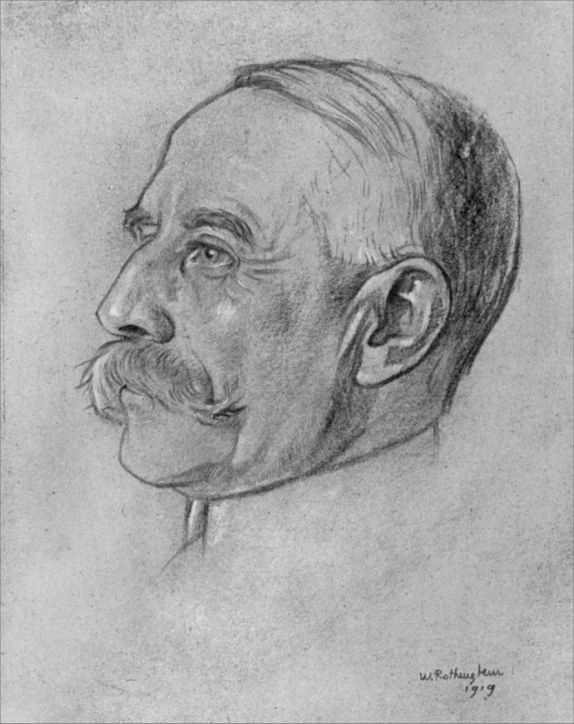

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the ''

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the ''

"Elgar, Edward".

'Grove Music Online''. Retrieved 20 April 2010 Edward was the fourth of their seven children. Ann Elgar had converted to Roman Catholicism shortly before Edward's birth, and he was baptised and brought up as a Roman Catholic, to the disapproval of his father. William Elgar was a violinist of professional standard and held the post of organist of St George's Roman Catholic Church, Worcester, from 1846 to 1885. At his instigation, masses by Cherubini and Hummel were first heard at the Elgar's mother was interested in the arts and encouraged his musical development. He inherited from her a discerning taste for literature and a passionate love of the countryside. His friend and biographer W. H. "Billy" Reed wrote that Elgar's early surroundings had an influence that "permeated all his work and gave to his whole life that subtle but none the less true and sturdy English quality". He began composing at an early age; for a play written and acted by the Elgar children when he was about ten, he wrote music that forty years later he rearranged with only minor changes and orchestrated as the suites titled ''

Elgar's mother was interested in the arts and encouraged his musical development. He inherited from her a discerning taste for literature and a passionate love of the countryside. His friend and biographer W. H. "Billy" Reed wrote that Elgar's early surroundings had an influence that "permeated all his work and gave to his whole life that subtle but none the less true and sturdy English quality". He began composing at an early age; for a play written and acted by the Elgar children when he was about ten, he wrote music that forty years later he rearranged with only minor changes and orchestrated as the suites titled ''

"Elgar, Sir Edward William"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' archive, Oxford University Press, 1949. Retrieved 20 April 2010 . Elgar regularly played the bassoon in a wind quintet, alongside his brother Frank, an oboist (and conductor who ran his own wind band). Elgar arranged numerous pieces by In his first trips abroad, Elgar visited Paris in 1880 and Leipzig in 1882. He heard Saint-Saëns play the organ at the Madeleine and attended concerts by first-rate orchestras. In 1882 he wrote, "I got pretty well dosed with

In his first trips abroad, Elgar visited Paris in 1880 and Leipzig in 1882. He heard Saint-Saëns play the organ at the Madeleine and attended concerts by first-rate orchestras. In 1882 he wrote, "I got pretty well dosed with

When Elgar was 29, he took on a new pupil, Caroline Alice Roberts, known as Alice, daughter of the late

When Elgar was 29, he took on a new pupil, Caroline Alice Roberts, known as Alice, daughter of the late

In 1899, that prediction suddenly came true. At the age of forty-two, Elgar produced the ''

In 1899, that prediction suddenly came true. At the age of forty-two, Elgar produced the ''

Elgar's biographer Basil Maine commented, "When Sir Arthur Sullivan died in 1900 it became apparent to many that Elgar, although a composer of another build, was his true successor as first musician of the land." Elgar's next major work was eagerly awaited. For the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival of 1900, he set Cardinal

Elgar's biographer Basil Maine commented, "When Sir Arthur Sullivan died in 1900 it became apparent to many that Elgar, although a composer of another build, was his true successor as first musician of the land." Elgar's next major work was eagerly awaited. For the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival of 1900, he set Cardinal  Elgar is probably best known for the first of the five ''

Elgar is probably best known for the first of the five ''

, The Elgar Society. Retrieved 5 June 2010. In March 1904 a three-day festival of Elgar's works was presented at Covent Garden, an honour never before given to any English composer. '' Elgar was

Elgar was  The

The

In June 1911, as part of the celebrations surrounding the

In June 1911, as part of the celebrations surrounding the  Elgar's other compositions during the war included

Elgar's other compositions during the war included

"How I fell in love with E E's darling"

, ''

Although in the 1920s Elgar's music was no longer in fashion, his admirers continued to present his works when possible. Reed singles out a performance of the Second Symphony in March 1920 conducted by "a young man almost unknown to the public", Adrian Boult, for bringing "the grandeur and nobility of the work" to a wider public. Also in 1920, Landon Ronald presented an all-Elgar concert at the

Although in the 1920s Elgar's music was no longer in fashion, his admirers continued to present his works when possible. Reed singles out a performance of the Second Symphony in March 1920 conducted by "a young man almost unknown to the public", Adrian Boult, for bringing "the grandeur and nobility of the work" to a wider public. Also in 1920, Landon Ronald presented an all-Elgar concert at the

"Beyond the Malverns: Elgar in the Amazon"

, ''The Guardian'', 25 March 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010 After Alice's death, Elgar sold the Hampstead house, and after living for a short time in a flat in In his final years, Elgar experienced a musical revival. The BBC organised a festival of his works to celebrate his seventy-fifth birthday, in 1932. He flew to Paris in 1933 to conduct the Violin Concerto for Menuhin. While in France, he visited his fellow composer

In his final years, Elgar experienced a musical revival. The BBC organised a festival of his works to celebrate his seventy-fifth birthday, in 1932. He flew to Paris in 1933 to conduct the Violin Concerto for Menuhin. While in France, he visited his fellow composer

Elgar's best-known works were composed within the twenty-one years between 1899 and 1920. Most of them are orchestral. Reed wrote, "Elgar's genius rose to its greatest height in his orchestral works" and quoted the composer as saying that, even in his oratorios, the orchestral part is the most important. The ''Enigma Variations'' made Elgar's name nationally. The variation form was ideal for him at this stage of his career, when his comprehensive mastery of orchestration was still in contrast to his tendency to write his melodies in short, sometimes rigid, phrases. His next orchestral works, ''

Elgar's best-known works were composed within the twenty-one years between 1899 and 1920. Most of them are orchestral. Reed wrote, "Elgar's genius rose to its greatest height in his orchestral works" and quoted the composer as saying that, even in his oratorios, the orchestral part is the most important. The ''Enigma Variations'' made Elgar's name nationally. The variation form was ideal for him at this stage of his career, when his comprehensive mastery of orchestration was still in contrast to his tendency to write his melodies in short, sometimes rigid, phrases. His next orchestral works, '' Elgar's Violin Concerto and

Elgar's Violin Concerto and

Views of Elgar's stature have varied in the decades since his music came to prominence at the beginning of the twentieth century. Richard Strauss, as noted, hailed Elgar as a progressive composer; even the hostile reviewer in ''The Observer'', unimpressed by the thematic material of the First Symphony in 1908, called the orchestration "magnificently modern". Hans Richter rated Elgar as "the greatest modern composer" in any country, and Richter's colleague Arthur Nikisch considered the First Symphony "a masterpiece of the first order" to be "justly ranked with the great symphonic models – Beethoven and Brahms." By contrast, the critic

Views of Elgar's stature have varied in the decades since his music came to prominence at the beginning of the twentieth century. Richard Strauss, as noted, hailed Elgar as a progressive composer; even the hostile reviewer in ''The Observer'', unimpressed by the thematic material of the First Symphony in 1908, called the orchestration "magnificently modern". Hans Richter rated Elgar as "the greatest modern composer" in any country, and Richter's colleague Arthur Nikisch considered the First Symphony "a masterpiece of the first order" to be "justly ranked with the great symphonic models – Beethoven and Brahms." By contrast, the critic  In 1967 the critic and analyst David Cox considered the question of the supposed Englishness of Elgar's music. Cox noted that Elgar disliked folk-songs and never used them in his works, opting for an idiom that was essentially German, leavened by a lightness derived from French composers including Berlioz and Gounod. How then, asked Cox, could Elgar be "the most English of composers"? Cox found the answer in Elgar's own personality, which "could use the alien idioms in such a way as to make of them a vital form of expression that was his and his alone. And the personality that comes through in the music is English." This point about Elgar's transmuting his influences had been touched on before. In 1930 ''The Times'' wrote, "When Elgar's first symphony came out, someone attempted to prove that its main tune on which all depends was like the Grail theme in Parsifal. ... but the attempt fell flat because everyone else, including those who disliked the tune, had instantly recognized it as typically 'Elgarian', while the Grail theme is as typically Wagnerian." As for Elgar's "Englishness", his fellow-composers recognised it: Richard Strauss and

In 1967 the critic and analyst David Cox considered the question of the supposed Englishness of Elgar's music. Cox noted that Elgar disliked folk-songs and never used them in his works, opting for an idiom that was essentially German, leavened by a lightness derived from French composers including Berlioz and Gounod. How then, asked Cox, could Elgar be "the most English of composers"? Cox found the answer in Elgar's own personality, which "could use the alien idioms in such a way as to make of them a vital form of expression that was his and his alone. And the personality that comes through in the music is English." This point about Elgar's transmuting his influences had been touched on before. In 1930 ''The Times'' wrote, "When Elgar's first symphony came out, someone attempted to prove that its main tune on which all depends was like the Grail theme in Parsifal. ... but the attempt fell flat because everyone else, including those who disliked the tune, had instantly recognized it as typically 'Elgarian', while the Grail theme is as typically Wagnerian." As for Elgar's "Englishness", his fellow-composers recognised it: Richard Strauss and

Elgar was knighted in 1904, and in 1911 he was appointed a member of the

Elgar was knighted in 1904, and in 1911 he was appointed a member of the

''Elgar and the Bridge''

BBC Hereford and Worcester. Retrieved 2 June 2010. Elgar had three locomotives named in his honour. Elgar's life and music have inspired works of literature including the novel ''Gerontius'' and several plays. ''Elgar's Rondo'', a 1993 stage play by

Elgar's life and music have inspired works of literature including the novel ''Gerontius'' and several plays. ''Elgar's Rondo'', a 1993 stage play by

The Elgar Society

official site.

The Elgar Foundation and Birthplace Museum

official site.

"Elgar, Sir Edward William"

at

"The Growing Significance of Elgar"

lecture by Simon Mundy,

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the ''

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the ''Enigma Variations

Edward Elgar composed his ''Variations on an Original Theme'', Op. 36, popularly known as the ''Enigma Variations'', between October 1898 and February 1899. It is an orchestral work comprising fourteen variations on an original theme.

Elgar ...

'', the ''Pomp and Circumstance Marches

The ''Pomp and Circumstance Marches'' (full title ''Pomp and Circumstance Military Marches''), Op. 39, are a series of five (or six) marches for orchestra composed by Sir Edward Elgar. The first four were published between 1901 and 1907 ...

'', concertos for violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

and cello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a Bow (music), bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), t ...

, and two symphonies

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, most often for orchestra. Although the term has had many meanings from its origins in the ancient Greek era, by the late 18th century the word had taken on the meaning com ...

. He also composed choral works, including ''The Dream of Gerontius

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment b ...

'', chamber music and songs. He was appointed Master of the King's Musick

Master of the King's Music (or Master of the Queen's Music, or earlier Master of the King's Musick) is a post in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. The holder of the post originally served the monarch of England, directing the court orche ...

in 1924.

Although Elgar is often regarded as a typically English composer, most of his musical influences were not from England but from continental Europe. He felt himself to be an outsider, not only musically, but socially. In musical circles dominated by academics, he was a self-taught composer; in Protestant Britain, his Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

ism was regarded with suspicion in some quarters; and in the class-conscious society of Victorian and Edwardian

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

Britain, he was acutely sensitive about his humble origins even after he achieved recognition. He nevertheless married the daughter of a senior British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer. She inspired him both musically and socially, but he struggled to achieve success until his forties, when after a series of moderately successful works his ''Enigma Variations'' (1899) became immediately popular in Britain and overseas. He followed the Variations with a choral work, ''The Dream of Gerontius'' (1900), based on a Roman Catholic text that caused some disquiet in the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

establishment in Britain, but it became, and has remained, a core repertory work in Britain and elsewhere. His later full-length religious choral works were well received but have not entered the regular repertory.

In his fifties, Elgar composed a symphony and a violin concerto that were immensely successful. His second symphony and his cello concerto did not gain immediate public popularity and took many years to achieve a regular place in the concert repertory of British orchestras. Elgar's music came, in his later years, to be seen as appealing chiefly to British audiences. His stock remained low for a generation after his death. It began to revive significantly in the 1960s, helped by new recordings of his works. Some of his works have, in recent years, been taken up again internationally, but the music continues to be played more in Britain than elsewhere.

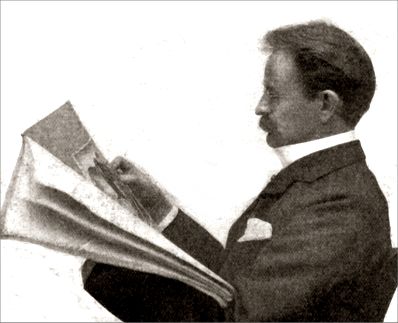

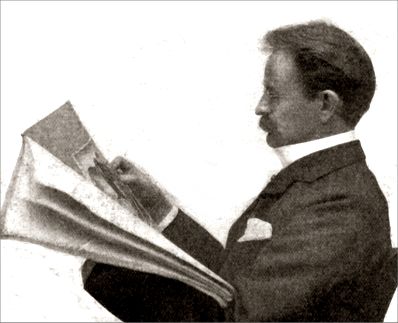

Elgar has been described as the first composer to take the gramophone

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

seriously. Between 1914 and 1925, he conducted a series of acoustic recording

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English), or simply a record, is an analog signal, analog sound Recording medium, storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove ...

s of his works. The introduction of the moving-coil microphone in 1923 made far more accurate sound reproduction possible, and Elgar made new recordings of most of his major orchestral works and excerpts from ''The Dream of Gerontius''.

Biography

Early years

Edward Elgar was born in the small village of Lower Broadheath, outsideWorcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Englan ...

, England, on 2 June 1857. His father, William Henry Elgar (1821–1906), was raised in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

and had been apprenticed to a London music publisher. In 1841 William moved to Worcester, where he worked as a piano tuner

Piano tuning is the act of adjusting the tension of the strings of an acoustic piano so that the musical intervals between strings are in tune. The meaning of the term 'in tune', in the context of piano tuning, is not simply a particular fixed ...

and set up a shop selling sheet music and musical instruments. In 1848 he married Ann Greening (1822–1902), daughter of a farm worker.McVeagh, Diana"Elgar, Edward".

'Grove Music Online''. Retrieved 20 April 2010 Edward was the fourth of their seven children. Ann Elgar had converted to Roman Catholicism shortly before Edward's birth, and he was baptised and brought up as a Roman Catholic, to the disapproval of his father. William Elgar was a violinist of professional standard and held the post of organist of St George's Roman Catholic Church, Worcester, from 1846 to 1885. At his instigation, masses by Cherubini and Hummel were first heard at the

Three Choirs Festival

200px, Worcester cathedral

200px, Gloucester cathedral

The Three Choirs Festival is a music festival held annually at the end of July, rotating among the cathedrals of the Three Counties (Hereford, Gloucester and Worcester) and originally featu ...

by the orchestra in which he played the violin."Edward Elgar", ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'', 1 October 1900, pp. 641–48

All the Elgar children received a musical upbringing. By the age of eight, Elgar was taking piano and violin lessons, and his father, who tuned the pianos at many grand houses in Worcestershire, would sometimes take him along, giving him the chance to display his skill to important local figures.

Elgar's mother was interested in the arts and encouraged his musical development. He inherited from her a discerning taste for literature and a passionate love of the countryside. His friend and biographer W. H. "Billy" Reed wrote that Elgar's early surroundings had an influence that "permeated all his work and gave to his whole life that subtle but none the less true and sturdy English quality". He began composing at an early age; for a play written and acted by the Elgar children when he was about ten, he wrote music that forty years later he rearranged with only minor changes and orchestrated as the suites titled ''

Elgar's mother was interested in the arts and encouraged his musical development. He inherited from her a discerning taste for literature and a passionate love of the countryside. His friend and biographer W. H. "Billy" Reed wrote that Elgar's early surroundings had an influence that "permeated all his work and gave to his whole life that subtle but none the less true and sturdy English quality". He began composing at an early age; for a play written and acted by the Elgar children when he was about ten, he wrote music that forty years later he rearranged with only minor changes and orchestrated as the suites titled ''The Wand of Youth

''The Wand of Youth'' Suites No. 1 and No. 2 are works for full orchestra by the English composer Edward Elgar. The titles given them by Elgar were, in full: ''The Wand of Youth'' (Music to a Child's Play) First Suite, Op. 1a (1869–1907) and ...

''.

Until he was fifteen, Elgar received a general education at Littleton (now Lyttleton) House school, near Worcester. His only formal musical training beyond piano and violin lessons from local teachers consisted of more advanced violin studies with Adolf Pollitzer, during brief visits to London in 1877–78. Elgar said, "my first music was learnt in the Cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denomination ...

... from books borrowed from the music library, when I was eight, nine or ten."''Quoted'' by Kennedy (ODNB) He worked through manuals of instruction on organ playing and read every book he could find on the theory of music. He later said that he had been most helped by Hubert Parry

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry, 1st Baronet (27 February 18487 October 1918) was an English composer, teacher and historian of music. Born in Richmond Hill in Bournemouth, Parry's first major works appeared in 1880. As a composer he is b ...

's articles in the ''Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language ''Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and theo ...

''.

Elgar began to learn German, in the hope of going to the Leipzig Conservatory

The University of Music and Theatre "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig (german: Hochschule für Musik und Theater "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig) is a public university in Leipzig (Saxony, Germany). Founded in 1843 by Felix Mendelssohn ...

for further musical studies, but his father could not afford to send him. Years later, a profile in ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'' considered that his failure to get to Leipzig was fortunate for Elgar's musical development: "Thus the budding composer escaped the dogmatism of the schools." However, it was a disappointment to Elgar that on leaving school in 1872 he went not to Leipzig but to the office of a local solicitor as a clerk. He did not find an office career congenial, and for fulfilment he turned not only to music but to literature, becoming a voracious reader. Around this time, he made his first public appearances as a violinist and organist.

After a few months, Elgar left the solicitor to embark on a musical career, giving piano and violin lessons and working occasionally in his father's shop. He was an active member of the Worcester Glee club

A glee club in the United States is a musical group or choir group, historically of male voices but also of female or mixed voices, which traditionally specializes in the singing of short songs by trios or quartets. In the late 19th century it w ...

, along with his father, and he accompanied singers, played the violin, composed and arranged works, and conducted for the first time. Pollitzer believed that, as a violinist, Elgar had the potential to be one of the leading soloists in the country, but Elgar himself, having heard leading virtuosi at London concerts, felt his own violin playing lacked a full enough tone, and he abandoned his ambitions to be a soloist. At twenty-two he took up the post of conductor of the attendants' band at the Worcester and County Lunatic Asylum in Powick

Powick is a village and civil parish in the Malvern Hills district of Worcestershire, England, located two miles south of the city of Worcester and four miles north of Great Malvern. The parish includes the village of Callow End and the hamlets ...

, from Worcester. The band consisted of: piccolo, flute, clarinet, two cornets, euphonium, three or four first and a similar number of second violins, occasional viola, cello, double bass and piano. Elgar coached the players and wrote and arranged their music, including quadrille

The quadrille is a dance that was fashionable in late 18th- and 19th-century Europe and its colonies. The quadrille consists of a chain of four to six '' contredanses''. Latterly the quadrille was frequently danced to a medley of opera melodie ...

s and polkas, for the unusual combination of instruments. ''The Musical Times'' wrote, "This practical experience proved to be of the greatest value to the young musician. ... He acquired a practical knowledge of the capabilities of these different instruments. ... He thereby got to know intimately the tone colour, the ins and outs of these and many other instruments." He held the post for five years, from 1879, travelling to Powick once a week. Another post he held in his early days was professor of the violin at the Worcester College for the Blind Sons of Gentlemen.

Although rather solitary and introspective by nature, Elgar thrived in Worcester's musical circles. He played in the violins at the Worcester and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

Festivals, and one great experience was to play Dvořák's Symphony No. 6 and ''Stabat Mater

The Stabat Mater is a 13th-century Christian hymn to Mary, which portrays her suffering as Jesus Christ's mother during his crucifixion. Its author may be either the Franciscan friar Jacopone da Todi or Pope Innocent III.Sabatier, Paul ''Life o ...

'' under the composer's baton.Maine, Basil"Elgar, Sir Edward William"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' archive, Oxford University Press, 1949. Retrieved 20 April 2010 . Elgar regularly played the bassoon in a wind quintet, alongside his brother Frank, an oboist (and conductor who ran his own wind band). Elgar arranged numerous pieces by

Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

, Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

, and others for the quintet, honing his arranging and compositional skills.

In his first trips abroad, Elgar visited Paris in 1880 and Leipzig in 1882. He heard Saint-Saëns play the organ at the Madeleine and attended concerts by first-rate orchestras. In 1882 he wrote, "I got pretty well dosed with

In his first trips abroad, Elgar visited Paris in 1880 and Leipzig in 1882. He heard Saint-Saëns play the organ at the Madeleine and attended concerts by first-rate orchestras. In 1882 he wrote, "I got pretty well dosed with Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

(my ideal!), Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

, Rubinstein Rubinstein is a surname of German and Yiddish origin, mostly found among Ashkenazi Jews; it denotes "ruby-stone". Notable persons named Rubinstein include:

A–E

* Akiba Rubinstein (1880–1961), Polish chess grandmaster

* Amnon Rubinstein (born ...

& Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, so had no cause to complain." In Leipzig he visited a friend, Helen Weaver, who was a student at the Conservatoire. They became engaged in the summer of 1883, but for unknown reasons the engagement was broken off the next year. Elgar was greatly distressed, and some of his later cryptic dedications of romantic music may have alluded to Helen and his feelings for her. Throughout his life, Elgar was often inspired by close women friends; Helen Weaver was succeeded by Mary Lygon, Dora Penny

The Dorabella Cipher is an enciphered letter written by composer Edward Elgar to Dora Penny, which was accompanied by another dated July 14, 1897. Penny never deciphered it and its meaning remains unknown.

The cipher, consisting of 87 characters s ...

, Julia Worthington, Alice Stuart Wortley and finally Vera Hockman, who enlivened his old age.

In 1882, seeking more professional orchestral experience, Elgar was employed as a violinist in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

in William Stockley's Orchestra

William Stockley's Orchestra was a symphony orchestra based in Birmingham, England from 1856 to 1899. It was the first permanent orchestra formed of local musicians to be established in the town, in contrast to the earlier Birmingham Festival Orch ...

, for whom he played every concert for the next seven years and where he later said he "learned all the music I know". On 13 December 1883 he took part with Stockley in a performance at Birmingham Town Hall

Birmingham Town Hall is a concert hall and venue for popular assemblies opened in 1834 and situated in Victoria Square, Birmingham, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

The hall underwent a major renovation between 2002 and 2007. It no ...

of one of his first works for full orchestra, the ''Sérénade mauresque'' – the first time one of his compositions had been performed by a professional orchestra. Stockley had invited him to conduct the piece but later recalled "he declined, and, further, insisted upon playing in his place in the orchestra. The consequence was that he had to appear, fiddle in hand, to acknowledge the genuine and hearty applause of the audience." Elgar often went to London in an attempt to get his works published, but this period in his life found him frequently despondent and low on money. He wrote to a friend in April 1884, "My prospects are about as hopeless as ever ... I am not wanting in energy I think, so sometimes I conclude that 'tis want of ability. ... I have no money – not a cent."

Marriage

When Elgar was 29, he took on a new pupil, Caroline Alice Roberts, known as Alice, daughter of the late

When Elgar was 29, he took on a new pupil, Caroline Alice Roberts, known as Alice, daughter of the late Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Sir Henry Roberts, and published author of verse and prose fiction. Eight years older than Elgar, Alice became his wife three years later. Elgar's biographer Michael Kennedy writes, "Alice's family was horrified by her intention to marry an unknown musician who worked in a shop and was a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

. She was disinherited." They were married on 8 May 1889, at Brompton Oratory

Brompton Oratory is a large neo-classical Roman Catholic church in the Knightsbridge area of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London. Its full name is the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, or as named in its Grade II* archite ...

. From then until her death, she acted as his business manager and social secretary, dealt with his mood swings, and was a perceptive musical critic. She did her best to gain him the attention of influential society, though with limited success. In time, he would learn to accept the honours given him, realising that they mattered more to her and her social class and recognising what she had given up to further his career. In her diary, she wrote, "The care of a genius is enough of a life work for any woman." As an engagement present, Elgar dedicated his short violin-and-piano piece ''Salut d'Amour

''Salut d'Amour'' (''Liebesgruß''), Op. 12, is a musical work composed by Edward Elgar in 1888, originally written for violin and piano.

History

Elgar finished the piece in July 1888, when he was romantically involved with Caroline Alice Elg ...

'' to her. With Alice's encouragement, the Elgars moved to London to be closer to the centre of British musical life, and Elgar started devoting his time to composition. Their only child, Carice Irene, was born at their home in West Kensington

West Kensington, formerly North End, is an area in the ancient parish of Fulham, in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, England, 3.4 miles (5.5 km) west of Charing Cross. It covers most of the London postal area of W14, includin ...

on 14 August 1890. Her name, revealed in Elgar's dedication of ''Salut d'Amour'', was a contraction of her mother's names Caroline and Alice.

Elgar took full advantage of the opportunity to hear unfamiliar music. In the days before miniature scores and recordings were available, it was not easy for young composers to get to know new music. Elgar took every chance to do so at the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

concerts. He and Alice attended day after day, hearing music by a wide range of composers. Among these were masters of orchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orc ...

from whom he learned much, such as Berlioz and Richard Wagner. His own compositions made little impact on London's musical scene. August Manns

Sir August Friedrich Manns (12 March 1825 – 1 March 1907) was a German-born British conductor who made his career in England. After serving as a military bandmaster in Germany, he moved to England and soon became director of music at London' ...

conducted Elgar's orchestral version of ''Salut d'amour'' and the Suite in D at the Crystal Palace, and two publishers accepted some of Elgar's violin pieces, organ voluntaries, and part song

A part song, part-song or partsong is a form of choral music that consists of a song to a secular or non-liturgical sacred text, written or arranged for several vocal parts. Part songs are commonly sung by an SATB choir, but sometimes for an all ...

s.Reed, p. 23 Some tantalising opportunities seemed to be within reach but vanished unexpectedly. For example, an offer from the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Op ...

, Covent Garden, to run through some of his works was withdrawn at the last second when Sir Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinafore'', ''The Pirates of Penzance' ...

arrived unannounced to rehearse some of his own music. Sullivan was horrified when Elgar later told him what had happened. Elgar's only important commission while in London came from his home city: the Worcester Festival Committee invited him to compose a short orchestral work for the 1890 Three Choirs Festival. The result is described by Diana McVeagh

Diana McVeagh (born 6 September 1926, Ipoh) is a British author on classical music. She has written a biography of Gerald Finzi and several books on Edward Elgar. McVeagh studied at the Royal College of Music in the 1940s and was assistant editor ...

in the ''Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', as "his first major work, the assured and uninhibited ''Froissart

Jean Froissart (Old and Middle French: ''Jehan'', – ) (also John Froissart) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meliador'', a long Arthurian ...

''." Elgar conducted the first performance in Worcester in September 1890. For lack of other work, he was obliged to leave London in 1891 and return with his wife and child to Worcestershire, where he could earn a living conducting local musical ensembles and teaching. They settled in Alice's former home town, Great Malvern

Great Malvern is an area of the spa town of Malvern, Worcestershire, England. It lies at the foot of the Malvern Hills, a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, on the eastern flanks of the Worcestershire Beacon and North Hill, and is ...

.

Growing reputation

During the 1890s, Elgar gradually built up a reputation as a composer, chiefly of works for the great choral festivals of theEnglish Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

. '' The Black Knight'' (1892) and '' King Olaf'' (1896), both inspired by Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely transl ...

, ''The Light of Life'' (1896) and ''Caractacus'' (1898) were all modestly successful, and he obtained a long-standing publisher in Novello and Co.''The Musical Times'', obituary of Elgar, April 1934, pp. 314–18 Other works of this decade included the '' Serenade for Strings'' (1892) and ''Three Bavarian Dances

Three Bavarian Dances, Op. 27, is an orchestral work by Edward Elgar.

It is an arrangement for orchestra of three of the set of six songs titled '' From the Bavarian Highlands''. The original song lyrics were written by the composer’s wife A ...

'' (1897). Elgar was of enough consequence locally to recommend the young composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (15 August 18751 September 1912) was a British composer and conductor.

Of mixed-race birth, Coleridge-Taylor achieved such success that he was referred to by white New York musicians as the "African Mahler" when ...

to the Three Choirs Festival for a concert piece, which helped establish the younger man's career. Elgar was catching the attention of prominent critics, but their reviews were polite rather than enthusiastic. Although he was in demand as a festival composer, he was only just getting by financially and felt unappreciated. In 1898, he said he was "very sick at heart over music" and hoped to find a way to succeed with a larger work. His friend August Jaeger

August Johannes Jaeger (18 March 1860 – 18 May 1909) was an Anglo-German music publisher, who developed a close friendship with the English composer Edward Elgar. He offered advice and help to Elgar and is immortalised in the ''Enigma Va ...

tried to lift his spirits: "A day's attack of the blues ... will not drive away your desire, your necessity, which is to exercise those creative faculties which a kind providence has given you. Your time of universal recognition will come."

In 1899, that prediction suddenly came true. At the age of forty-two, Elgar produced the ''

In 1899, that prediction suddenly came true. At the age of forty-two, Elgar produced the ''Enigma Variations

Edward Elgar composed his ''Variations on an Original Theme'', Op. 36, popularly known as the ''Enigma Variations'', between October 1898 and February 1899. It is an orchestral work comprising fourteen variations on an original theme.

Elgar ...

'', which were premiered in London under the baton of the eminent German conductor Hans Richter. In Elgar's own words, "I have sketched a set of Variations on an original theme. The Variations have amused me because I've labelled them with the nicknames of my particular friends ... that is to say I've written the variations each one to represent the mood of the 'party' (the person) ... and have written what I think they would have written – if they were asses enough to compose". He dedicated the work "To my friends pictured within". Probably the best known variation is "Nimrod", depicting Jaeger. Purely musical considerations led Elgar to omit variations depicting Arthur Sullivan and Hubert Parry, whose styles he tried but failed to incorporate in the variations. The large-scale work was received with general acclaim for its originality, charm and craftsmanship, and it established Elgar as the pre-eminent British composer of his generation.

The work is formally titled ''Variations on an Original Theme''; the word "Enigma" appears over the first six bars of music, which led to the familiar version of the title. The enigma is that, although there are fourteen variations on the "original theme", there is another overarching theme, never identified by Elgar, which he said "runs through and over the whole set" but is never heard. Later commentators have observed that although Elgar is today regarded as a characteristically English composer, his orchestral music and this work in particular share much with the Central European tradition typified at the time by the work of Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

. The ''Enigma Variations'' were well received in Germany and Italy, and remain to the present day a worldwide concert staple.

National and international fame

Elgar's biographer Basil Maine commented, "When Sir Arthur Sullivan died in 1900 it became apparent to many that Elgar, although a composer of another build, was his true successor as first musician of the land." Elgar's next major work was eagerly awaited. For the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival of 1900, he set Cardinal

Elgar's biographer Basil Maine commented, "When Sir Arthur Sullivan died in 1900 it became apparent to many that Elgar, although a composer of another build, was his true successor as first musician of the land." Elgar's next major work was eagerly awaited. For the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival of 1900, he set Cardinal John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

's poem ''The Dream of Gerontius

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment b ...

'' for soloists, chorus and orchestra. Richter conducted the premiere, which was marred by a poorly prepared chorus, which sang badly. Critics recognised the mastery of the piece despite the defects in performance. It was performed in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

, Germany, in 1901 and again in 1902, conducted by Julius Buths

Julius Buths (7 May 185112 March 1920) was a German pianist, conductor and minor composer. He was particularly notable in his early championing of the works of Edward Elgar in Germany. He conducted the continental European premieres of both the ...

, who also conducted the European premiere of the ''Enigma Variations'' in 1901. The German press was enthusiastic. ''The Cologne Gazette'' said, "In both parts we meet with beauties of imperishable value. ... Elgar stands on the shoulders of Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

, from whose influences he has freed himself until he has become an important individuality. He is one of the leaders of musical art of modern times." ''The Düsseldorfer Volksblatt'' wrote, "A memorable and epoch-making first performance! Since the days of Liszt nothing has been produced in the way of oratorio ... which reaches the greatness and importance of this sacred cantata." Richard Strauss, then widely viewed as the leading composer of his day,Reed, p. 61 was so impressed that in Elgar's presence he proposed a toast to the success of "the first English progressive musician, Meister Elgar." Performances in Vienna, Paris and New York followed, and ''The Dream of Gerontius'' soon became equally admired in Britain. According to Kennedy, "It is unquestionably the greatest British work in the oratorio form ... topened a new chapter in the English choral tradition and liberated it from its Handelian preoccupation." Elgar, as a Roman Catholic, was much moved by Newman's poem about the death and redemption of a sinner, but some influential members of the Anglican establishment disagreed. His colleague, Charles Villiers Stanford

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Romantic music, Romantic era. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was ed ...

complained that the work "stinks of incense". The Dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

banned ''Gerontius'' from his cathedral in 1901, and at Worcester the following year, the Dean insisted on expurgations before allowing a performance.

Elgar is probably best known for the first of the five ''

Elgar is probably best known for the first of the five ''Pomp and Circumstance Marches

The ''Pomp and Circumstance Marches'' (full title ''Pomp and Circumstance Military Marches''), Op. 39, are a series of five (or six) marches for orchestra composed by Sir Edward Elgar. The first four were published between 1901 and 1907 ...

'', which were composed between 1901 and 1930.Kennedy (1970), pp. 38–39 It is familiar to millions of television viewers all over the world every year who watch the Last Night of the Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert H ...

, where it is traditionally performed. When the theme of the slower middle section (technically called the " trio") of the first march came into his head, he told his friend Dora Penny, "I've got a tune that will knock 'em – will knock 'em flat". When the first march was played in 1901 at a London Promenade Concert, it was conducted by Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introducing hund ...

, who later wrote that the audience "rose and yelled ... the one and only time in the history of the Promenade concerts that an orchestral item was accorded a double encore." To mark the coronation of Edward VII, Elgar was commissioned to set A. C. Benson's ''Coronation Ode'' for a gala concert at the Royal Opera House on 30 June 1902. The approval of the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

was confirmed, and Elgar began work. The contralto

A contralto () is a type of classical female singing voice whose vocal range is the lowest female voice type.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare; similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to that of a countertenor, typically b ...

Clara Butt

Dame Clara Ellen Butt, (1 February 1872 – 23 January 1936) was an English contralto and one of the most popular singers from the 1890s through to the 1920s. She had an exceptionally fine contralto voice and an agile singing technique, and imp ...

had persuaded him that the trio of the first ''Pomp and Circumstance'' march could have words fitted to it, and Elgar invited Benson to do so. Elgar incorporated the new vocal version into the Ode. The publishers of the score recognised the potential of the vocal piece, "Land of Hope and Glory

"Land of Hope and Glory" is a British patriotic song, with music by Edward Elgar written in 1901 and lyrics by A. C. Benson later added in 1902.

Composition

The music to which the words of the refrain 'Land of Hope and Glory, &c' below ar ...

", and asked Benson and Elgar to make a further revision for publication as a separate song. It was immensely popular and is now considered an unofficial British national anthem. In the United States, the trio, known simply as "Pomp and Circumstance" or "The Graduation March", has been adopted since 1905 for virtually all high school and university graduations."Why Americans graduate to Elgar", The Elgar Society. Retrieved 5 June 2010. In March 1904 a three-day festival of Elgar's works was presented at Covent Garden, an honour never before given to any English composer. ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' commented, "Four or five years ago if any one had predicted that the Opera-house would be full from floor to ceiling for the performance of an oratorio by an English composer he would probably have been supposed to be out of his mind.""Concerts", ''The Times'', 15 March 1904, p. 8 The king and queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

attended the first concert, at which Richter conducted ''The Dream of Gerontius'', and returned the next evening for the second, the London premiere of '' The Apostles'' (first heard the previous year at the Birmingham Festival). The final concert of the festival, conducted by Elgar, was primarily orchestral, apart for an excerpt from ''Caractacus'' and the complete ''Sea Pictures

''Sea Pictures, Op. 37'' is a song cycle by Sir Edward Elgar consisting of five songs written by various poets. It was set for contralto and orchestra, though a distinct version for piano was often performed by Elgar. Many mezzo-sopranos have su ...

'' (sung by Clara Butt). The orchestral items were ''Froissart'', the ''Enigma Variations'', ''Cockaigne

Cockaigne or Cockayne () is a land of plenty in medieval myth, an imaginary place of extreme luxury and ease where physical comforts and pleasures are always immediately at hand and where the harshness of medieval peasant life does not exist. ...

'', the first two (at that time the only two) ''Pomp and Circumstance'' marches, and the premiere of a new orchestral work, '' In the South'', inspired by a holiday in Italy.

Elgar was

Elgar was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

at Buckingham Palace on 5 July 1904. The following month, he and his family moved to Plâs Gwyn, a large house on the outskirts of Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

, overlooking the River Wye

The River Wye (; cy, Afon Gwy ) is the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, fourth-longest river in the UK, stretching some from its source on Plynlimon in mid Wales to the Severn estuary. For much of its length the river forms part of Wal ...

, where they lived until 1911. Between 1902 and 1914, Elgar was, in Kennedy's words, at the zenith of popularity. He made four visits to the US, including one conducting tour, and earned considerable fees from the performance of his music. Between 1905 and 1908, he held the post of Peyton Professor of Music at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

. He had accepted the post reluctantly, feeling that a composer should not head a school of music. He was not at ease in the role, and his lectures caused controversy, with his attacks on the critics and on English music in general: "Vulgarity in the course of time may be refined. Vulgarity often goes with inventiveness ... but the commonplace mind can never be anything but commonplace. An Englishman will take you into a large room, beautifully proportioned, and will point out to you that it is white – all over white – and somebody will say, 'What exquisite taste'. You know in your own mind, in your own soul, that it is not taste at all, that it is the want of taste, that is mere evasion. English music is white, and evades everything." He regretted the controversy and was glad to hand on the post to his friend Granville Bantock

Sir Granville Ransome Bantock (7 August 186816 October 1946) was a British composer of classical music.

Biography

Granville Ransome Bantock was born in London. His father was an eminent Scottish surgeon.Hadden, J. Cuthbert, 1913, ''Modern Music ...

in 1908. His new life as a celebrity was a mixed blessing to the highly strung Elgar, as it interrupted his privacy, and he often was in ill-health. He complained to Jaeger in 1903, "My life is one continual giving up of little things which I love." Both W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas. The most f ...

and Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

sought to collaborate with Elgar in this decade. Elgar refused, but would have collaborated with Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

had Shaw been willing.

Elgar paid three visits to the USA between 1905 and 1911. His first was to conduct his music and to accept a doctorate from Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

. His principal composition in 1905 was the '' Introduction and Allegro for Strings'', dedicated to Samuel Sanford

Samuel Simons Sanford (15 March 18496 January 1910) was an American pianist and educator.

Early life

He was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Education

He studied piano in New York with William Mason (son of Lowell Mason and student of Franz Lis ...

. It was well received but did not catch the public imagination as ''The Dream of Gerontius'' had done and continued to do. Among keen Elgarians, however, ''The Kingdom'' was sometimes preferred to the earlier work: Elgar's friend Frank Schuster told the young Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

: "compared with ''The Kingdom'', ''Gerontius'' is the work of a raw amateur." As Elgar approached his fiftieth birthday, he began work on his first symphony, a project that had been in his mind in various forms for nearly ten years. His First Symphony (1908) was a national and international triumph. Within weeks of the premiere it was performed in New York under Walter Damrosch

Walter Johannes Damrosch (January 30, 1862December 22, 1950) was a German-born American conductor and composer. He was the director of the New York Symphony Orchestra and conducted the world premiere performances of various works, including Ge ...

, Vienna under Ferdinand Löwe

Ferdinand Löwe (19 February 1865 – 6 January 1925) was an Austrian conductor.

Biography

Löwe was born in Vienna, Austria where along with Munich, Germany his career was primarily centered. From 1896 Löwe conducted the Kaim Orchestra, tod ...

, St Petersburg under Alexander Siloti

Alexander Ilyich Siloti (also Ziloti, russian: Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Зило́ти, ''Aleksandr Iljič Ziloti'', uk, Олександр Ілліч Зілоті; 9 October 1863 – 8 December 1945) was a Russian virtuoso pianist, ...

, and Leipzig under Arthur Nikisch

Arthur Nikisch (12 October 185523 January 1922) was a Hungarian conductor who performed internationally, holding posts in Boston, London, Leipzig and—most importantly—Berlin. He was considered an outstanding interpreter of the music of Br ...

. There were performances in Rome, Chicago, Boston, Toronto and fifteen British towns and cities. In just over a year, it received a hundred performances in Britain, America and continental Europe."Elgar's Symphony", ''The Musical Times'', 1 February 1909, p. 102

The

The Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

(1910) was commissioned by Fritz Kreisler

Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisler (February 2, 1875 – January 29, 1962) was an Austrian-born American violinist and composer. One of the most noted violin masters of his day, and regarded as one of the greatest violinists of all time, he was known ...

, one of the leading international violinists of the time. Elgar wrote it during the summer of 1910, with occasional help from W. H. Reed, the leader of the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

, who helped the composer with advice on technical points. Elgar and Reed formed a firm friendship, which lasted for the rest of Elgar's life. Reed's biography, ''Elgar As I Knew Him'' (1936), records many details of Elgar's methods of composition. The work was presented by the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

, with Kreisler and the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer. Reed recalled, "the Concerto proved to be a complete triumph, the concert a brilliant and unforgettable occasion."Reed, p. 103 So great was the impact of the concerto that Kreisler's rival Eugène Ysaÿe

Eugène-Auguste Ysaÿe (; 16 July 185812 May 1931) was a Belgian virtuoso violinist, composer, and conductor. He was regarded as "The King of the Violin", or, as Nathan Milstein put it, the "tsar".

Legend of the Ysaÿe violin

Eugène Ysaÿe ...

spent much time with Elgar going through the work. There was great disappointment when contractual difficulties prevented Ysaÿe from playing it in London.

The Violin Concerto was Elgar's last popular triumph. The following year he presented his Second Symphony in London, but was disappointed at its reception. Unlike the First Symphony, it ends not in a blaze of orchestral splendour but quietly and contemplatively. Reed, who played at the premiere, later wrote that Elgar was recalled to the platform several times to acknowledge the applause, "but missed that unmistakable note perceived when an audience, even an English audience, is thoroughly roused or worked up, as it was after the Violin Concerto or the First Symphony."Reed, p. 105 Elgar asked Reed, "What is the matter with them, Billy? They sit there like a lot of stuffed pigs." The work was, by normal standards, a success, with twenty-seven performances within three years of its premiere, but it did not achieve the international ''furore'' of the First Symphony.

Last major works

In June 1911, as part of the celebrations surrounding the

In June 1911, as part of the celebrations surrounding the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

, Elgar was appointed to the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

, an honour limited to twenty-four holders at any time. The following year, the Elgars moved back to London, to a large house in Netherhall Gardens, Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

, designed by Norman Shaw

Richard Norman Shaw RA (7 May 1831 – 17 November 1912), also known as Norman Shaw, was a British architect who worked from the 1870s to the 1900s, known for his country houses and for commercial buildings. He is considered to be among the g ...

. There Elgar composed his last two large-scale works of the pre-war era, the choral ode, ''The Music Makers'' (for the Birmingham Festival, 1912) and the symphonic study ''Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays '' Henry IV, Part 1'' and '' Part 2'', w ...

'' (for the Leeds Festival, 1913). Both were received politely but without enthusiasm. Even the dedicatee of ''Falstaff'', the conductor Landon Ronald

Sir Landon Ronald (born Landon Ronald Russell) (7 June 1873 – 14 August 1938) was an English conductor, composer, pianist, teacher and administrator.

In his early career he gained work as an accompanist and ''répétiteur'', but struggled ...

, confessed privately that he could not "make head or tail of the piece," while the musical scholar Percy Scholes

Percy Alfred Scholes PhD OBE (24 July 1877 – 31 July 1958) (pronounced ''skolz'') was an English musician, journalist and prolific writer, whose best-known achievement was his compilation of the first edition of ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' ...

wrote of ''Falstaff'' that it was a "great work" but, "so far as public appreciation goes, a comparative failure."

When World War I broke out, Elgar was horrified at the prospect of the carnage, but his patriotic feelings were nonetheless aroused. He composed "A Song for Soldiers", which he later withdrew. He signed up as a special constable in the local police and later joined the Hampstead Volunteer Reserve of the army. He composed patriotic works, ''Carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a keyboard and consists of at least 23 cast-bronze bells. The bells are hung in fixed suspension and tuned in chromatic order so that they can be sounded harmoniou ...

'', a recitation for speaker and orchestra in honour of Belgium, and '' Polonia'', an orchestral piece in honour of Poland. "Land of Hope and Glory", already popular, became still more so, and Elgar wished in vain to have new, less nationalistic, words sung to the tune.

Elgar's other compositions during the war included

Elgar's other compositions during the war included incidental music

Incidental music is music in a play, television program, radio program, video game, or some other presentation form that is not primarily musical. The term is less frequently applied to film music, with such music being referred to instead as t ...

for a children's play, ''The Starlight Express

''The Starlight Express'' is a children's play by Violet Pearn, based on the imaginative novel ''A Prisoner in Fairyland'' by Algernon Blackwood, with songs and incidental music written by the English composer Sir Edward Elgar in 1915.

Produc ...

'' (1915); a ballet, ''The Sanguine Fan

''The Sanguine Fan'', Op. 81, is a single-act ballet written by Sir Edward Elgar in 1917. It was one of the pieces he composed to raise money for wartime charities, having been asked to write it by his close friend and confidante Lady Alice Stua ...

'' (1917); and ''The Spirit of England

''The Spirit of England'', Op. 80, is a work for chorus, orchestra, and soprano/tenor soloist in three movements composed by Edward Elgar between 1915 and 1917, setting text from Laurence Binyon's 1914 anthology of poems '' The Winnowing Fan''. ...

'' (1915–17, to poems by Laurence Binyon

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869 – 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. Born in Lancaster, England, his parents were Frederick Binyon, a clergyman, and Mary Dockray. He studied at St Paul's School, London ...

), three choral settings very different in character from the romantic patriotism of his earlier years. His last large-scale composition of the war years was ''The Fringes of the Fleet

''The Fringes of the Fleet'' is a booklet written in 1915 by Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936). The booklet contains essays and poems about nautical subjects in World War I.

It is also the title of a song-cycle written in 1917 with music by the En ...

'', settings of verses by Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

, performed with great popular success around the country, until Kipling for unexplained reasons objected to their performance in theatres. Elgar conducted a recording of the work for the Gramophone Company

The Gramophone Company Limited (The Gramophone Co. Ltd.), based in the United Kingdom and founded by Emil Berliner, was one of the early recording companies, the parent organisation for the ''His Master's Voice (HMV)'' label, and the European ...

.

Towards the end of the war, Elgar was in poor health. His wife thought it best for him to move to the countryside, and she rented "Brinkwells", a house near Fittleworth

Fittleworth is a village and civil parish in the District of Chichester in West Sussex, England located seven kilometres (3 miles) west from Pulborough on the A283 road and three miles (5 km) south east from Petworth. The village has ...

in Sussex, from the painter Rex Vicat Cole

Reginald ("Rex") George Vicat Cole (1870–1940) was an English landscape painter.

Life

Vicat Cole was the son of the artist George Vicat Cole and Mary Ann Chignell. He was educated at Eton and began to exhibit in London in 1890. In 1900 he was ...

. There Elgar recovered his strength and, in 1918 and 1919, he produced four large-scale works. The first three of these were chamber pieces: the Violin Sonata in E minor, the Piano Quintet in A minor, and the String Quartet in E minor. On hearing the work in progress, Alice Elgar wrote in her diary, "E. writing wonderful new music".Oliver, Michael, Review, ''Gramophone

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

'', June 1986, p. 73 All three works were well received. ''The Times'' wrote, "Elgar's sonata contains much that we have heard before in other forms, but as we do not at all want him to change and be somebody else, that is as it should be." The quartet and quintet were premiered at the Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall is a concert hall located at 36 Wigmore Street, London. Originally called Bechstein Hall, it specialises in performances of chamber music, early music, vocal music and song recitals. It is widely regarded as one of the world's leadin ...

on 21 May 1919. ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' wrote, "This quartet, with its tremendous climaxes, curious refinements of dance-rhythms, and its perfect symmetry, and the quintet, more lyrical and passionate, are as perfect examples of chamber music as the great oratorios were of their type."

By contrast, the remaining work, the Cello Concerto in E minor, had a disastrous premiere, at the opening concert of the London Symphony Orchestra's 1919–20 season in October 1919. Apart from the Elgar work, which the composer conducted, the rest of the programme was conducted by Albert Coates, who overran his rehearsal time at the expense of Elgar's. Lady Elgar wrote, "that brutal selfish ill-mannered bounder ... that brute Coates went on rehearsing."Lloyd-Webber, Julian"How I fell in love with E E's darling"

, ''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'', 17 May 2007. The critic of ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'', Ernest Newman

Ernest Newman (30 November 1868 – 7 July 1959) was an English music critic and musicologist. ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' describes him as "the most celebrated British music critic in the first half of the 20th century." His ...

, wrote, "There have been rumours about during the week of inadequate rehearsal. Whatever the explanation, the sad fact remains that never, in all probability, has so great an orchestra made so lamentable an exhibition of itself. ... The work itself is lovely stuff, very simple – that pregnant simplicity that has come upon Elgar's music in the last couple of years – but with a profound wisdom and beauty underlying its simplicity." Elgar attached no blame to his soloist, Felix Salmond

Felix Adrian Norman Salmond (19 November 188820 February 1952) was an English cellist and cello teacher who achieved success in the UK and the US.

Early life and career

Salmond was born to a family of professional musicians. His father Norman Sa ...

, who played the work for him again later.Reed, p. 131 In contrast with the First Symphony and its hundred performances in just over a year, the Cello Concerto did not have a second performance in London for more than a year.

Last years

Although in the 1920s Elgar's music was no longer in fashion, his admirers continued to present his works when possible. Reed singles out a performance of the Second Symphony in March 1920 conducted by "a young man almost unknown to the public", Adrian Boult, for bringing "the grandeur and nobility of the work" to a wider public. Also in 1920, Landon Ronald presented an all-Elgar concert at the

Although in the 1920s Elgar's music was no longer in fashion, his admirers continued to present his works when possible. Reed singles out a performance of the Second Symphony in March 1920 conducted by "a young man almost unknown to the public", Adrian Boult, for bringing "the grandeur and nobility of the work" to a wider public. Also in 1920, Landon Ronald presented an all-Elgar concert at the Queen's Hall