Edo-period Works on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the

The Edo period or Tokugawa period is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the

The Edo period or Tokugawa period is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu encouraged foreign trade but also was suspicious of outsiders. He wanted to make Edo a major port, but once he learned that the Europeans favored ports in Kyūshū and that China had rejected his plans for official trade, he moved to control existing trade and allowed only certain ports to handle specific kinds of commodities.

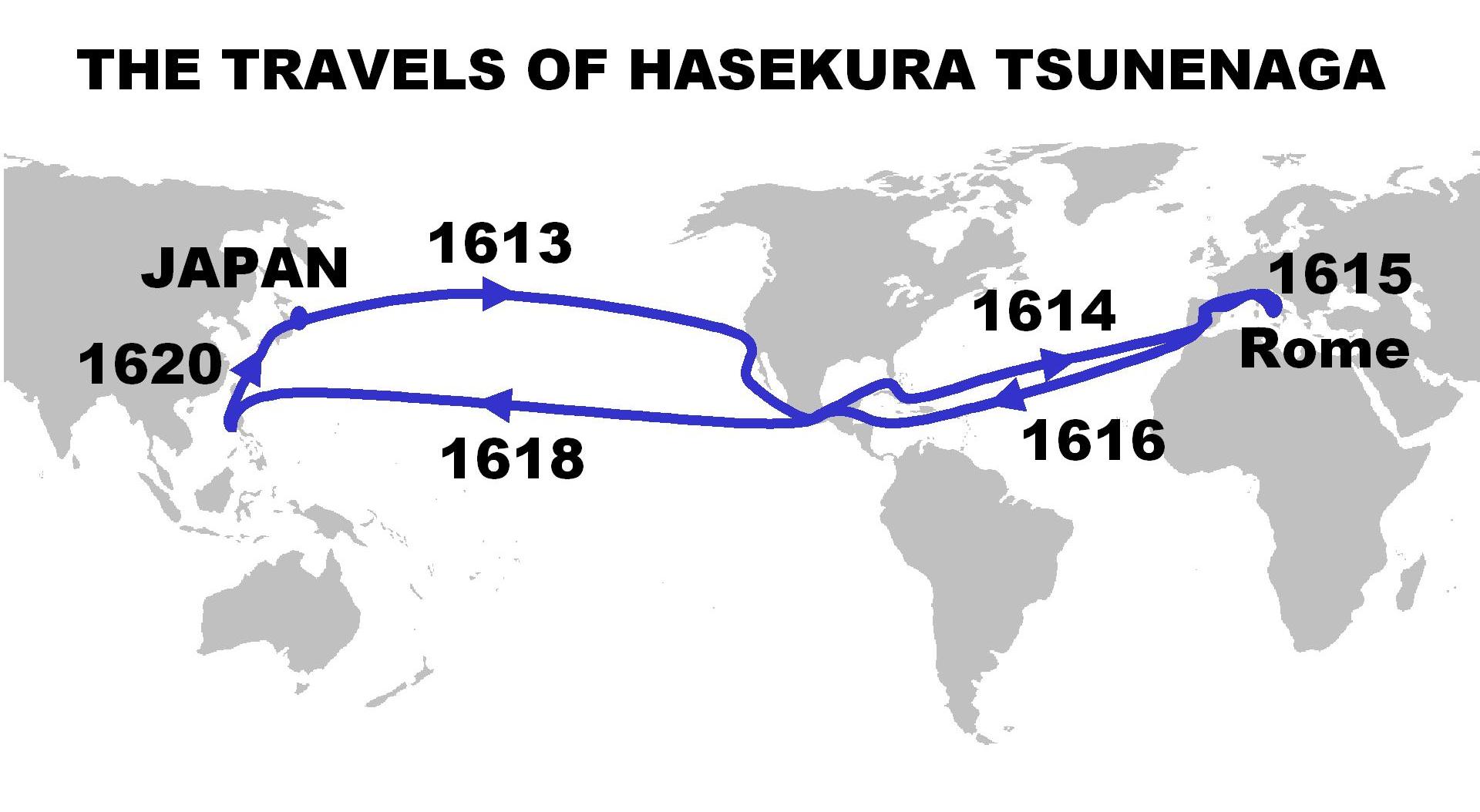

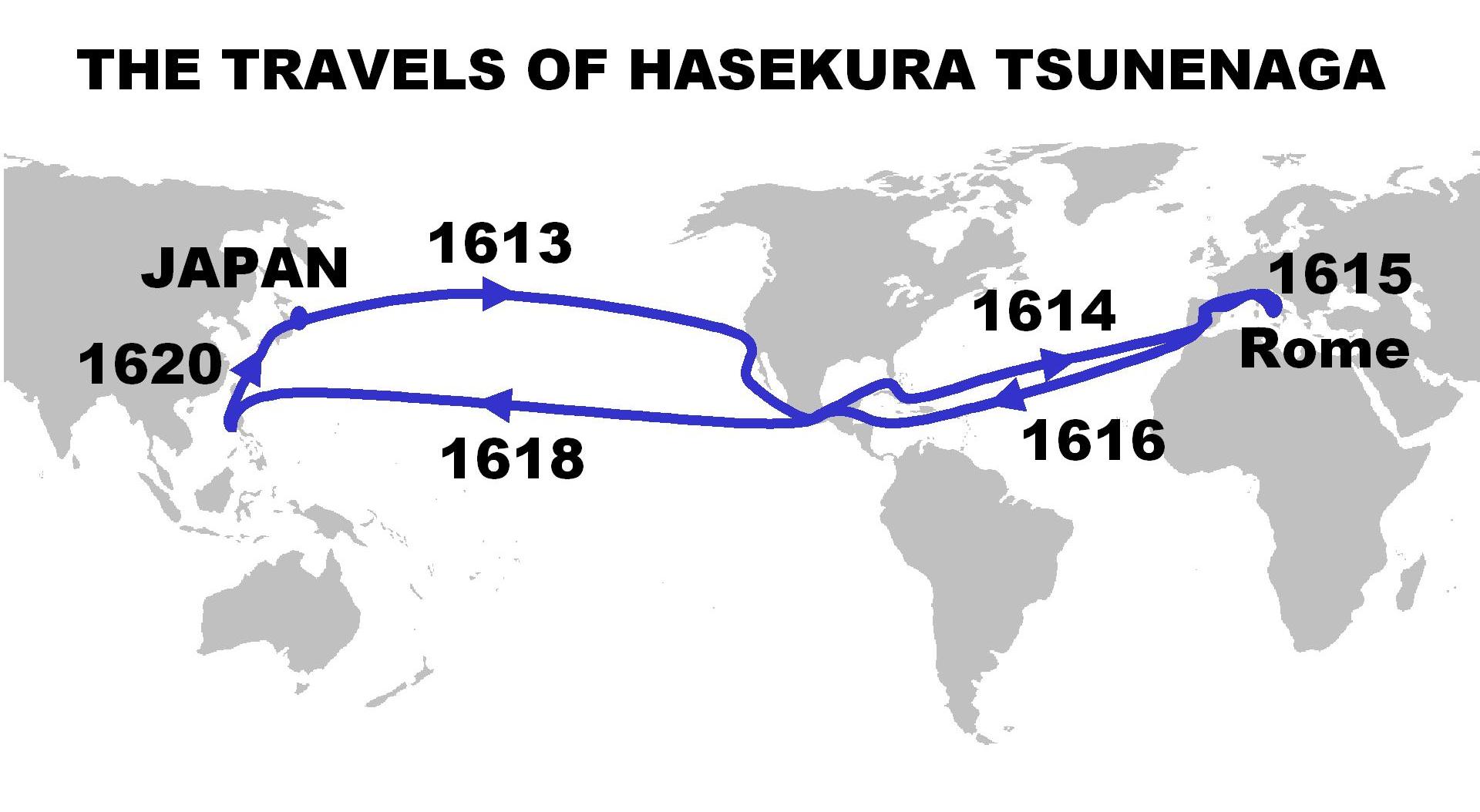

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu encouraged foreign trade but also was suspicious of outsiders. He wanted to make Edo a major port, but once he learned that the Europeans favored ports in Kyūshū and that China had rejected his plans for official trade, he moved to control existing trade and allowed only certain ports to handle specific kinds of commodities. The beginning of the Edo period coincides with the last decades of the Nanban trade period during which intense interaction with European powers, on the economic and religious plane, took place. It is at the beginning of the Edo period that Japan built its first ocean-going warships, such as the ''San Juan Bautista'', a 500- ton galleon-type ship that transported a Japanese embassy headed by Hasekura Tsunenaga to the Americas and then to Europe. Also during that period, the ''bakufu'' commissioned around 720 Red Seal Ships, three-masted and armed trade ships, for intra-Asian commerce. Japanese adventurers, such as Yamada Nagamasa, used those ships throughout Asia.

The beginning of the Edo period coincides with the last decades of the Nanban trade period during which intense interaction with European powers, on the economic and religious plane, took place. It is at the beginning of the Edo period that Japan built its first ocean-going warships, such as the ''San Juan Bautista'', a 500- ton galleon-type ship that transported a Japanese embassy headed by Hasekura Tsunenaga to the Americas and then to Europe. Also during that period, the ''bakufu'' commissioned around 720 Red Seal Ships, three-masted and armed trade ships, for intra-Asian commerce. Japanese adventurers, such as Yamada Nagamasa, used those ships throughout Asia. The "Christian problem" was, in effect, a problem of controlling both the Christian ''daimyo'' in Kyūshū and their trade with the Europeans. By 1612, the ''shōgun''s retainers and residents of Tokugawa lands had been ordered to forswear Christianity. More restrictions came in 1616 (the restriction of foreign trade to Nagasaki and Hirado, an island northwest of Kyūshū), 1622 (the execution of 120 missionaries and converts), 1624 (the expulsion of the Spanish), and 1629 (the execution of thousands of Christians). Finally, the

The "Christian problem" was, in effect, a problem of controlling both the Christian ''daimyo'' in Kyūshū and their trade with the Europeans. By 1612, the ''shōgun''s retainers and residents of Tokugawa lands had been ordered to forswear Christianity. More restrictions came in 1616 (the restriction of foreign trade to Nagasaki and Hirado, an island northwest of Kyūshū), 1622 (the execution of 120 missionaries and converts), 1624 (the expulsion of the Spanish), and 1629 (the execution of thousands of Christians). Finally, the

During the Tokugawa period, the social order, based on inherited position rather than personal merits, was rigid and highly formalized. At the top were the emperor and court nobles ('' kuge''), together with the ''shōgun'' and ''daimyo''. Below them the population was divided into four classes in a system known as ''mibunsei'' (身分制): the samurai on top (about 5% of the population) and the peasants (more than 80% of the population) on the second level. Below the peasants were the craftsmen, and even below them, on the fourth level, were the merchants. Only the peasants lived in the rural areas. Samurai, craftsmen and merchants lived in the

During the Tokugawa period, the social order, based on inherited position rather than personal merits, was rigid and highly formalized. At the top were the emperor and court nobles ('' kuge''), together with the ''shōgun'' and ''daimyo''. Below them the population was divided into four classes in a system known as ''mibunsei'' (身分制): the samurai on top (about 5% of the population) and the peasants (more than 80% of the population) on the second level. Below the peasants were the craftsmen, and even below them, on the fourth level, were the merchants. Only the peasants lived in the rural areas. Samurai, craftsmen and merchants lived in the

The Edo period passed on a vital commercial sector to be in flourishing urban centers, a relatively well-educated elite, a sophisticated government bureaucracy, productive agriculture, a closely unified nation with highly developed financial and marketing systems, and a national infrastructure of roads. Economic development during the Tokugawa period included

The Edo period passed on a vital commercial sector to be in flourishing urban centers, a relatively well-educated elite, a sophisticated government bureaucracy, productive agriculture, a closely unified nation with highly developed financial and marketing systems, and a national infrastructure of roads. Economic development during the Tokugawa period included

The Tokugawa era brought peace, and that brought prosperity to a nation of 31 million, 80% of them rice farmers. Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720.One chō, or chobu, equals 2.45 acres. Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of water to their paddies. The daimyos operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade.

The system of ''sankin kōtai'' meant that daimyos and their families often resided in Edo or travelled back to their domains, giving demand to an enormous consumer market in Edo and trade throughout the country. Samurai and daimyos, after prolonged peace, are accustomed to more elaborate lifestyles. To keep up with growing expenditures, the ''bakufu'' and daimyos often encouraged commercial crops and artifacts within their domains, from textiles to tea. The concentration of wealth also led to the development of financial markets. As the shogunate only allowed ''daimyos'' to sell surplus rice in Edo and Osaka, large-scale rice markets developed there. Each daimyo also had a capital city, located near the one castle they were allowed to maintain. Daimyos would have agents in various commercial centers, selling rice and cash crops, often exchanged for paper credit to be redeemed elsewhere. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, and currency came into common use. In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services.

The Tokugawa era brought peace, and that brought prosperity to a nation of 31 million, 80% of them rice farmers. Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720.One chō, or chobu, equals 2.45 acres. Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of water to their paddies. The daimyos operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade.

The system of ''sankin kōtai'' meant that daimyos and their families often resided in Edo or travelled back to their domains, giving demand to an enormous consumer market in Edo and trade throughout the country. Samurai and daimyos, after prolonged peace, are accustomed to more elaborate lifestyles. To keep up with growing expenditures, the ''bakufu'' and daimyos often encouraged commercial crops and artifacts within their domains, from textiles to tea. The concentration of wealth also led to the development of financial markets. As the shogunate only allowed ''daimyos'' to sell surplus rice in Edo and Osaka, large-scale rice markets developed there. Each daimyo also had a capital city, located near the one castle they were allowed to maintain. Daimyos would have agents in various commercial centers, selling rice and cash crops, often exchanged for paper credit to be redeemed elsewhere. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, and currency came into common use. In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services. The merchants benefited enormously, especially those with official patronage. However, the Neo-Confucian ideology of the shogunate focused the virtues of frugality and hard work; it had a rigid class system, which emphasized agriculture and despised commerce and merchants. A century after the Shogunate's establishment, problems began to emerge. The samurai, forbidden to engage in farming or business but allowed to borrow money, borrowed too much, some taking up side jobs as bodyguards for merchants, debt collectors, or artisans. The ''bakufu'' and ''daimyos'' raised taxes on farmers, but did not tax business, so they too fell into debt, with some merchants specializing in loaning to daimyos. Yet it was inconceivable to systematically tax commerce, as it would make money off "parasitic" activities, raise the prestige of merchants, and lower the status of government. As they paid no regular taxes, the forced financial contributions to the daimyos were seen by some merchants as a cost of doing business. The wealth of merchants gave them a degree of prestige and even power over the daimyos.

By 1750, rising taxes incited peasant unrest and even revolt. The nation had to deal somehow with samurai impoverishment and treasury deficits. The financial troubles of the samurai undermined their loyalties to the system, and the empty treasury threatened the whole system of government. One solution was reactionary—cutting samurai salaries and prohibiting spending for luxuries. Other solutions were modernizing, with the goal of increasing agrarian productivity. The eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (in office 1716–1745) had considerable success, though much of his work had to be done again between 1787 and 1793 by the shogun's chief councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829). Other shoguns debased the coinage to pay debts, which caused inflation. Overall, while commerce (domestic and international) was vibrant and sophisticated financial services had developed in the Edo period, the shogunate remained ideologically focused on honest agricultural work as the basis of society and never sought to develop a mercantile or capitalistic country.

By 1800, the commercialization of the economy grew rapidly, bringing more and more remote villages into the national economy. Rich farmers appeared who switched from rice to high-profit commercial crops and engaged in local money-lending, trade, and small-scale manufacturing. Wealthy merchants were often forced to "lend" money to the shogunate or daimyos (often never returned). They often had to hide their wealth, and some sought higher social status by using money to marry into the samurai class. There is some evidence that as merchants gained greater political influence in the late Edo period, the rigid class division between samurai and merchants began to break down.

A few domains, notably Chōsū and Satsuma, used innovative methods to restore their finances, but most sunk further into debt. The financial crisis provoked a reactionary solution near the end of the "Tempo era" (1830-1843) promulgated by the chief counselor Mizuno Tadakuni. He raised taxes, denounced luxuries and tried to impede the growth of business; he failed and it appeared to many that the continued existence of the entire Tokugawa system was in jeopardy.

The merchants benefited enormously, especially those with official patronage. However, the Neo-Confucian ideology of the shogunate focused the virtues of frugality and hard work; it had a rigid class system, which emphasized agriculture and despised commerce and merchants. A century after the Shogunate's establishment, problems began to emerge. The samurai, forbidden to engage in farming or business but allowed to borrow money, borrowed too much, some taking up side jobs as bodyguards for merchants, debt collectors, or artisans. The ''bakufu'' and ''daimyos'' raised taxes on farmers, but did not tax business, so they too fell into debt, with some merchants specializing in loaning to daimyos. Yet it was inconceivable to systematically tax commerce, as it would make money off "parasitic" activities, raise the prestige of merchants, and lower the status of government. As they paid no regular taxes, the forced financial contributions to the daimyos were seen by some merchants as a cost of doing business. The wealth of merchants gave them a degree of prestige and even power over the daimyos.

By 1750, rising taxes incited peasant unrest and even revolt. The nation had to deal somehow with samurai impoverishment and treasury deficits. The financial troubles of the samurai undermined their loyalties to the system, and the empty treasury threatened the whole system of government. One solution was reactionary—cutting samurai salaries and prohibiting spending for luxuries. Other solutions were modernizing, with the goal of increasing agrarian productivity. The eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (in office 1716–1745) had considerable success, though much of his work had to be done again between 1787 and 1793 by the shogun's chief councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829). Other shoguns debased the coinage to pay debts, which caused inflation. Overall, while commerce (domestic and international) was vibrant and sophisticated financial services had developed in the Edo period, the shogunate remained ideologically focused on honest agricultural work as the basis of society and never sought to develop a mercantile or capitalistic country.

By 1800, the commercialization of the economy grew rapidly, bringing more and more remote villages into the national economy. Rich farmers appeared who switched from rice to high-profit commercial crops and engaged in local money-lending, trade, and small-scale manufacturing. Wealthy merchants were often forced to "lend" money to the shogunate or daimyos (often never returned). They often had to hide their wealth, and some sought higher social status by using money to marry into the samurai class. There is some evidence that as merchants gained greater political influence in the late Edo period, the rigid class division between samurai and merchants began to break down.

A few domains, notably Chōsū and Satsuma, used innovative methods to restore their finances, but most sunk further into debt. The financial crisis provoked a reactionary solution near the end of the "Tempo era" (1830-1843) promulgated by the chief counselor Mizuno Tadakuni. He raised taxes, denounced luxuries and tried to impede the growth of business; he failed and it appeared to many that the continued existence of the entire Tokugawa system was in jeopardy.

The first shogun Ieyasu set up Confucian academies in his ''

The first shogun Ieyasu set up Confucian academies in his ''

National Diet Library.''第6回 和本の楽しみ方4 江戸の草紙'' p.3.

Konosuke Hashiguchi. (2013) Seikei University.

Advanced studies and growing applications of neo-Confucianism contributed to the transition of the social and political order from feudal norms to class- and large-group-oriented practices. The rule of the people or Confucian man was gradually replaced by the rule of law. New laws were developed, and new administrative devices were instituted. A new theory of government and a new vision of society emerged as a means of justifying more comprehensive governance by the bakufu. Each person had a distinct place in society and was expected to work to fulfill his or her mission in life. The people were to be ruled with benevolence by those whose assigned duty it was to rule. Government was all-powerful but responsible and humane. Although the class system was influenced by neo-Confucianism, it was not identical to it. Whereas soldiers and clergy were at the bottom of the hierarchy in the Chinese model, in Japan, some members of these classes constituted the ruling elite.

Members of the samurai class adhered to bushi traditions with a renewed interest in Japanese history and cultivation of the ways of Confucian scholar-administrators. A distinct culture known as ''

Advanced studies and growing applications of neo-Confucianism contributed to the transition of the social and political order from feudal norms to class- and large-group-oriented practices. The rule of the people or Confucian man was gradually replaced by the rule of law. New laws were developed, and new administrative devices were instituted. A new theory of government and a new vision of society emerged as a means of justifying more comprehensive governance by the bakufu. Each person had a distinct place in society and was expected to work to fulfill his or her mission in life. The people were to be ruled with benevolence by those whose assigned duty it was to rule. Government was all-powerful but responsible and humane. Although the class system was influenced by neo-Confucianism, it was not identical to it. Whereas soldiers and clergy were at the bottom of the hierarchy in the Chinese model, in Japan, some members of these classes constituted the ruling elite.

Members of the samurai class adhered to bushi traditions with a renewed interest in Japanese history and cultivation of the ways of Confucian scholar-administrators. A distinct culture known as '' Buddhism and Shinto were both still important in Tokugawa Japan. Buddhism, together with neo-Confucianism, provided standards of social behavior. Although Buddhism was not as politically powerful as it had been in the past, Buddhism continued to be espoused by the upper classes. Proscriptions against Christianity benefited Buddhism in 1640 when the bakufu ordered everyone to register at a temple. The rigid separation of Tokugawa society into han, villages, wards, and households helped reaffirm local Shinto attachments. Shinto provided spiritual support to the political order and was an important tie between the individual and the community. Shinto also helped preserve a sense of national identity.

Shinto eventually assumed an intellectual form as shaped by neo-Confucian rationalism and materialism. The kokugaku movement emerged from the interactions of these two belief systems. Kokugaku contributed to the emperor-centered nationalism of modern Japan and the revival of Shinto as a national creed in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, and Man'yōshū were all studied anew in the search for the Japanese spirit. Some purists in the kokugaku movement, such as Motoori Norinaga, even criticized the Confucian and Buddhist influences—in effect, foreign influences—for contaminating Japan's ancient ways. Japan was the land of the kami and, as such, had a special destiny.

During the period, Japan studied Western sciences and techniques (called '' rangaku'', "Dutch studies") through the information and books received through the Dutch traders in Dejima. The main areas that were studied included geography, medicine, natural sciences, astronomy, art, languages, physical sciences such as the study of electrical phenomena, and mechanical sciences as exemplified by the development of Japanese clockwatches, or

Buddhism and Shinto were both still important in Tokugawa Japan. Buddhism, together with neo-Confucianism, provided standards of social behavior. Although Buddhism was not as politically powerful as it had been in the past, Buddhism continued to be espoused by the upper classes. Proscriptions against Christianity benefited Buddhism in 1640 when the bakufu ordered everyone to register at a temple. The rigid separation of Tokugawa society into han, villages, wards, and households helped reaffirm local Shinto attachments. Shinto provided spiritual support to the political order and was an important tie between the individual and the community. Shinto also helped preserve a sense of national identity.

Shinto eventually assumed an intellectual form as shaped by neo-Confucian rationalism and materialism. The kokugaku movement emerged from the interactions of these two belief systems. Kokugaku contributed to the emperor-centered nationalism of modern Japan and the revival of Shinto as a national creed in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, and Man'yōshū were all studied anew in the search for the Japanese spirit. Some purists in the kokugaku movement, such as Motoori Norinaga, even criticized the Confucian and Buddhist influences—in effect, foreign influences—for contaminating Japan's ancient ways. Japan was the land of the kami and, as such, had a special destiny.

During the period, Japan studied Western sciences and techniques (called '' rangaku'', "Dutch studies") through the information and books received through the Dutch traders in Dejima. The main areas that were studied included geography, medicine, natural sciences, astronomy, art, languages, physical sciences such as the study of electrical phenomena, and mechanical sciences as exemplified by the development of Japanese clockwatches, or

In the field of art, the Rinpa school became popular. The paintings and crafts of the Rinpa school are characterized by highly decorative and showy designs using gold and silver leaves, bold compositions with simplified objects to be drawn, repeated patterns, and a playful spirit. Important figures in the Rinpa school include Hon'ami Kōetsu, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, Ogata Kōrin, Sakai Hōitsu and

In the field of art, the Rinpa school became popular. The paintings and crafts of the Rinpa school are characterized by highly decorative and showy designs using gold and silver leaves, bold compositions with simplified objects to be drawn, repeated patterns, and a playful spirit. Important figures in the Rinpa school include Hon'ami Kōetsu, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, Ogata Kōrin, Sakai Hōitsu and  Due to the end of the period of civil war and the development of the economy, many crafts with high artistic value were produced. Among the samurai class, arms came to be treated like works of art, and Japanese sword mountings and Japanese armour beautifully decorated with lacquer of '' maki-e'' technique and metal carvings became popular. Each '' han'' ( daimyo domain) encouraged the production of crafts to improve their finances, and crafts such as furnishings and '' inro'' beautifully decorated with lacquer, metal or ivory became popular among rich people. The Kaga Domain, which was ruled by the Maeda clan, was especially enthusiastic about promoting crafts, and the area still boasts a reputation that surpasses

Due to the end of the period of civil war and the development of the economy, many crafts with high artistic value were produced. Among the samurai class, arms came to be treated like works of art, and Japanese sword mountings and Japanese armour beautifully decorated with lacquer of '' maki-e'' technique and metal carvings became popular. Each '' han'' ( daimyo domain) encouraged the production of crafts to improve their finances, and crafts such as furnishings and '' inro'' beautifully decorated with lacquer, metal or ivory became popular among rich people. The Kaga Domain, which was ruled by the Maeda clan, was especially enthusiastic about promoting crafts, and the area still boasts a reputation that surpasses  Ukiyo-e is a genre of painting and printmaking that developed in the late 17th century, at first depicting the entertainments of the pleasure districts of Edo, such as courtesans and kabuki actors.

Ukiyo-e is a genre of painting and printmaking that developed in the late 17th century, at first depicting the entertainments of the pleasure districts of Edo, such as courtesans and kabuki actors.

File:Reading Stand with Mount Yoshino.jpg, Reading stand with

Clothing acquired a wide variety of designs and decorative techniques, especially for kimono worn by women. The main consumers of kimono were the samurai who used lavish clothing and other material luxuries to signal their place at the top of the social order. Driven by this

Clothing acquired a wide variety of designs and decorative techniques, especially for kimono worn by women. The main consumers of kimono were the samurai who used lavish clothing and other material luxuries to signal their place at the top of the social order. Driven by this

The end of this period is specifically called the late Tokugawa shogunate. The cause for the end of this period is controversial but is recounted as the forcing of Japan's opening to the world by Commodore Matthew Perry of the

The end of this period is specifically called the late Tokugawa shogunate. The cause for the end of this period is controversial but is recounted as the forcing of Japan's opening to the world by Commodore Matthew Perry of the

When Commodore Matthew C. Perry's four-ship squadron appeared in Edo Bay in July 1853, the bakufu was thrown into turmoil. The chairman of the senior councillors, Abe Masahiro (1819–1857), was responsible for dealing with the Americans. Having no precedent to manage this threat to national security, Abe tried to balance the desires of the senior councillors to compromise with the foreigners, of the emperor who wanted to keep the foreigners out, and of the ''daimyo'' who wanted to go to war. Lacking consensus, Abe decided to compromise by accepting Perry's demands for opening Japan to foreign trade while also making military preparations. In March 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity (or Treaty of Kanagawa) opened two ports to American ships seeking provisions, guaranteed good treatment to shipwrecked American sailors, and allowed a United States consul to take up residence in Shimoda, a seaport on the Izu Peninsula, southwest of Edo. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the U.S. and Japan ( Harris Treaty), opening still more areas to American trade, was forced on the ''bakufu'' five years later.

The resulting damage to the ''bakufu'' was significant. The devalued price for gold in Japan was one immediate, enormous effect. The European and American traders purchased gold for its original price on the world market and then sold it to the Japanese for triple the price. Along with this, cheap goods from these developed nations, like finished cotton, flooded the market forcing many Japanese out of business. Debate over government policy was unusual and had engendered public criticism of the ''bakufu''. In the hope of enlisting the support of new allies, Abe, to the consternation of the ''fudai'', had consulted with the ''shinpan'' and ''tozama daimyo'', further undermining the already weakened ''bakufu''. In the Ansei Reform (1854–1856), Abe then tried to strengthen the regime by ordering Dutch warships and armaments from the Netherlands and building new port defenses. In 1855, a naval training school with Dutch instructors was set up at Nagasaki, and a Western-style military school was established at Edo; by the next year, the government was translating Western books. Opposition to Abe increased within '' fudai'' circles, which opposed opening ''bakufu'' councils to ''tozama daimyo'', and he was replaced in 1855 as chairman of the senior councilors by Hotta Masayoshi (1810–1864).

At the head of the dissident faction was Tokugawa Nariaki, who had long embraced a militant loyalty to the emperor along with anti-foreign sentiments, and who had been put in charge of national defense in 1854. The Mito school—based on neo-Confucian and Shinto principles—had as its goal the restoration of the imperial institution, the turning back of the West, and the founding of a world empire under the divine Yamato dynasty.

In the final years of the Tokugawas, foreign contacts increased as more concessions were granted. The new treaty with the United States in 1859 allowed more ports to be opened to diplomatic representatives, unsupervised trade at four additional ports, and foreign residences in Osaka and Edo. It also embodied the concept of extraterritoriality (foreigners were subject to the laws of their own countries but not to Japanese law). Hotta lost the support of key ''daimyo'', and when Tokugawa Nariaki opposed the new treaty, Hotta sought imperial sanction. The court officials, perceiving the weakness of the ''bakufu'', rejected Hotta's request and thus suddenly embroiled Kyoto and the emperor in Japan's internal politics for the first time in many centuries. When the ''shōgun'' died without an heir, Nariaki appealed to the court for support of his own son, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (or Keiki), for ''shōgun'', a candidate favored by the ''

When Commodore Matthew C. Perry's four-ship squadron appeared in Edo Bay in July 1853, the bakufu was thrown into turmoil. The chairman of the senior councillors, Abe Masahiro (1819–1857), was responsible for dealing with the Americans. Having no precedent to manage this threat to national security, Abe tried to balance the desires of the senior councillors to compromise with the foreigners, of the emperor who wanted to keep the foreigners out, and of the ''daimyo'' who wanted to go to war. Lacking consensus, Abe decided to compromise by accepting Perry's demands for opening Japan to foreign trade while also making military preparations. In March 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity (or Treaty of Kanagawa) opened two ports to American ships seeking provisions, guaranteed good treatment to shipwrecked American sailors, and allowed a United States consul to take up residence in Shimoda, a seaport on the Izu Peninsula, southwest of Edo. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the U.S. and Japan ( Harris Treaty), opening still more areas to American trade, was forced on the ''bakufu'' five years later.

The resulting damage to the ''bakufu'' was significant. The devalued price for gold in Japan was one immediate, enormous effect. The European and American traders purchased gold for its original price on the world market and then sold it to the Japanese for triple the price. Along with this, cheap goods from these developed nations, like finished cotton, flooded the market forcing many Japanese out of business. Debate over government policy was unusual and had engendered public criticism of the ''bakufu''. In the hope of enlisting the support of new allies, Abe, to the consternation of the ''fudai'', had consulted with the ''shinpan'' and ''tozama daimyo'', further undermining the already weakened ''bakufu''. In the Ansei Reform (1854–1856), Abe then tried to strengthen the regime by ordering Dutch warships and armaments from the Netherlands and building new port defenses. In 1855, a naval training school with Dutch instructors was set up at Nagasaki, and a Western-style military school was established at Edo; by the next year, the government was translating Western books. Opposition to Abe increased within '' fudai'' circles, which opposed opening ''bakufu'' councils to ''tozama daimyo'', and he was replaced in 1855 as chairman of the senior councilors by Hotta Masayoshi (1810–1864).

At the head of the dissident faction was Tokugawa Nariaki, who had long embraced a militant loyalty to the emperor along with anti-foreign sentiments, and who had been put in charge of national defense in 1854. The Mito school—based on neo-Confucian and Shinto principles—had as its goal the restoration of the imperial institution, the turning back of the West, and the founding of a world empire under the divine Yamato dynasty.

In the final years of the Tokugawas, foreign contacts increased as more concessions were granted. The new treaty with the United States in 1859 allowed more ports to be opened to diplomatic representatives, unsupervised trade at four additional ports, and foreign residences in Osaka and Edo. It also embodied the concept of extraterritoriality (foreigners were subject to the laws of their own countries but not to Japanese law). Hotta lost the support of key ''daimyo'', and when Tokugawa Nariaki opposed the new treaty, Hotta sought imperial sanction. The court officials, perceiving the weakness of the ''bakufu'', rejected Hotta's request and thus suddenly embroiled Kyoto and the emperor in Japan's internal politics for the first time in many centuries. When the ''shōgun'' died without an heir, Nariaki appealed to the court for support of his own son, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (or Keiki), for ''shōgun'', a candidate favored by the ''

Revering the emperor as a symbol of unity, extremists wrought violence and death against the Bakufu and Han authorities and foreigners. Foreign naval retaliation in the Anglo-Satsuma War led to still another concessionary commercial treaty in 1865, but Yoshitomi was unable to enforce the Western treaties. A ''bakufu'' army was defeated when it was sent to crush dissent in the Satsuma and Chōshū Domains in 1866. Finally, in 1867, Emperor Kōmei died and was succeeded by his underaged son Emperor Meiji.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu reluctantly became head of the Tokugawa house and ''shōgun''. He tried to reorganize the government under the emperor while preserving the ''shōgun''s leadership role. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Chōshū ''daimyo'', other ''daimyo'' called for returning the ''shōgun''s political power to the emperor and a council of ''daimyo'' chaired by the former Tokugawa ''shōgun''. Yoshinobu accepted the plan in late 1867 and resigned, announcing an "imperial restoration". The Satsuma, Chōshū, and other ''han'' leaders and radical courtiers, however, rebelled, seized the imperial palace, and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868.

Following the Boshin War (1868–1869), the ''bakufu'' was abolished, and Yoshinobu was reduced to the ranks of the common ''daimyo''. Resistance continued in the North throughout 1868, and the ''bakufu'' naval forces under Admiral Enomoto Takeaki continued to hold out for another six months in Hokkaidō, where they founded the short-lived Republic of Ezo.

Revering the emperor as a symbol of unity, extremists wrought violence and death against the Bakufu and Han authorities and foreigners. Foreign naval retaliation in the Anglo-Satsuma War led to still another concessionary commercial treaty in 1865, but Yoshitomi was unable to enforce the Western treaties. A ''bakufu'' army was defeated when it was sent to crush dissent in the Satsuma and Chōshū Domains in 1866. Finally, in 1867, Emperor Kōmei died and was succeeded by his underaged son Emperor Meiji.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu reluctantly became head of the Tokugawa house and ''shōgun''. He tried to reorganize the government under the emperor while preserving the ''shōgun''s leadership role. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Chōshū ''daimyo'', other ''daimyo'' called for returning the ''shōgun''s political power to the emperor and a council of ''daimyo'' chaired by the former Tokugawa ''shōgun''. Yoshinobu accepted the plan in late 1867 and resigned, announcing an "imperial restoration". The Satsuma, Chōshū, and other ''han'' leaders and radical courtiers, however, rebelled, seized the imperial palace, and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868.

Following the Boshin War (1868–1869), the ''bakufu'' was abolished, and Yoshinobu was reduced to the ranks of the common ''daimyo''. Resistance continued in the North throughout 1868, and the ''bakufu'' naval forces under Admiral Enomoto Takeaki continued to hold out for another six months in Hokkaidō, where they founded the short-lived Republic of Ezo.

Japan

Japanese Maps of the Tokugawa Era

– A rich selection of rare Japanese maps from the UBC Library Digital Collections

– Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire {{DEFAULTSORT:Edo Period 1603 establishments in Japan 17th century in Japan 1868 disestablishments in Japan 18th century in Japan 19th century in Japan Feudal Japan Japanese eras States and territories disestablished in 1868 States and territories established in 1603

history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in ...

and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period

The was a period in Japanese history of near-constant civil war and social upheaval from 1467 to 1615.

The Sengoku period was initiated by the Ōnin War in 1467 which collapsed the feudal system of Japan under the Ashikaga shogunate. Variou ...

, the Edo period was characterized by economic growth, strict social order, isolationist foreign policies, a stable population, perpetual peace, and popular enjoyment of arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both ...

and culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these grou ...

. The period derives its name from Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

(now Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

), where on March 24, 1603, the shogunate was officially established by Tokugawa Ieyasu. The period came to an end with the Meiji Restoration and the Boshin War, which restored imperial rule to Japan.

Consolidation of the shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in ...

and the country's regional '' daimyo''.

A revolution took place from the time of the Kamakura shogunate

The was the feudal military government of Japan during the Kamakura period from 1185 to 1333. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Kamakura-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 459.

The Kamakura shogunate was established by Minamoto no Yo ...

, which existed with the Tennō

The Emperor of Japan is the monarch and the head of the Imperial Family of Japan. Under the Constitution of Japan, he is defined as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, and his position is derived from "the wi ...

's court, to the Tokugawa, when the ''samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of History of Japan#Medieval Japan (1185–1573/1600), medieval and Edo period, early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retai ...

'' became the unchallenged rulers in what historian Edwin O. Reischauer

Edwin Oldfather Reischauer (; October 15, 1910 – September 1, 1990) was an American diplomat, educator, and professor at Harvard University. Born in Tokyo to American educational missionaries, he became a leading scholar of the history and cul ...

called a "centralized feudal" form of shogunate. Instrumental in the rise of the new bakufu was Tokugawa Ieyasu, the main beneficiary of the achievements of Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Already a powerful '' daimyo'' (feudal lord), Ieyasu profited by his transfer to the rich Kantō area. He maintained two million '' koku'' of land, a new headquarters at Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

, a strategically situated castle town (the future Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

), and also had an additional two million ''koku'' of land and thirty-eight vassals under his control. After Hideyoshi's death, Ieyasu moved quickly to seize control from the Toyotomi clan.

Ieyasu's victory over the western ''daimyo'' at the Battle of Sekigahara (October 21, 1600, or in the Japanese calendar on the 15th day of the ninth month of the fifth year of the Keichō era) gave him control of all Japan. He rapidly abolished numerous enemy ''daimyo'' houses, reduced others, such as that of the Toyotomi, and redistributed the spoils of war to his family and allies. Ieyasu still failed to achieve complete control of the western ''daimyo'', but his assumption of the title of '' shōgun'' helped consolidate the alliance system. After further strengthening his power base, Ieyasu installed his son Hidetada (1579–1632) as ''shōgun'' and himself as retired ''shōgun'' in 1605. The Toyotomi were still a significant threat, and Ieyasu devoted the next decade to their eradication. In 1615, the Tokugawa army destroyed the Toyotomi stronghold at Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of ...

.

The Tokugawa (or Edo) period brought 250 years of stability to Japan. The political system evolved into what historians call ''bakuhan'', a combination of the terms ''bakufu'' and '' han'' (domains) to describe the government and society of the period. In the ''bakuhan'', the ''shōgun'' had national authority and the ''daimyo'' had regional authority. This represented a new unity in the feudal structure, which featured an increasingly large bureaucracy to administer the mixture of centralized and decentralized authorities. The Tokugawa became more powerful during their first century of rule: land redistribution gave them nearly seven million ''koku'', control of the most important cities, and a land assessment system reaping great revenues.

The feudal hierarchy was completed by the various classes of ''daimyo''. Closest to the Tokugawa house were the ''shinpan

was a class of ''daimyō'' in the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan who were certain relatives of the ''Shōgun''.

While all ''shinpan'' were relatives of the ''shōgun'', not all relatives of the shōgun were ''shinpan''; an example of this is the ...

'', or "related houses". They were twenty-three ''daimyo'' on the borders of Tokugawa lands, all directly related to Ieyasu. The shinpan held mostly honorary titles and advisory posts in the bakufu. The second class of the hierarchy were the '' fudai'', or "house ''daimyo''", rewarded with lands close to the Tokugawa holdings for their faithful service. By the 18th century, 145 ''fudai'' controlled much smaller ''han'', the greatest assessed at 250,000 ''koku''. Members of the ''fudai'' class staffed most of the major bakufu offices. Ninety-seven ''han'' formed the third group, the '' tozama'' (outside vassals), former opponents or new allies. The ''tozama'' were located mostly on the peripheries of the archipelago and collectively controlled nearly ten million ''koku'' of productive land. Because the ''tozama'' were least trusted of the ''daimyo'', they were the most cautiously managed and generously treated, although they were excluded from central government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government ...

positions.

The Tokugawa shogunate not only consolidated their control over a reunified Japan, they also had unprecedented power over the emperor, the court, all ''daimyo'' and the religious orders. The emperor was held up as the ultimate source of political sanction for the ''shōgun'', who ostensibly was the vassal of the imperial family. The Tokugawa helped the imperial family recapture its old glory by rebuilding its palaces and granting it new lands. To ensure a close tie between the imperial clan and the Tokugawa family, Ieyasu's granddaughter was made an imperial consort in 1619.

A code of laws was established to regulate the ''daimyo'' houses. The code encompassed private conduct, marriage, dress, types of weapons and numbers of troops allowed; required feudal lords to reside in Edo every other year (the ''sankin-kōtai

''Sankin-kōtai'' ( ja, 参覲交代/参覲交替, now commonly written as ja, 参勤交代/参勤交替, lit=alternate attendance, label=none) was a policy of the Tokugawa shogunate during most of the Edo period of Japanese history.Jansen, M ...

'' system); prohibited the construction of ocean-going ships; proscribed Christianity; restricted castles to one per domain (''han'') and stipulated that bakufu regulations were the national law. Although the ''daimyo'' were not taxed per se, they were regularly levied for contributions for military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distin ...

and logistical support and for such public works projects as castles, roads, bridges and palaces. The various regulations and levies not only strengthened the Tokugawa but also depleted the wealth of the ''daimyo'', thus weakening their threat to the central administration. The ''han'', once military-centered domains, became mere local administrative units. The ''daimyo'' did have full administrative control over their territory and their complex systems of retainers, bureaucrats and commoners. Loyalty was exacted from religious foundations, already greatly weakened by Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, through a variety of control mechanisms.

Foreign trade relations

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu encouraged foreign trade but also was suspicious of outsiders. He wanted to make Edo a major port, but once he learned that the Europeans favored ports in Kyūshū and that China had rejected his plans for official trade, he moved to control existing trade and allowed only certain ports to handle specific kinds of commodities.

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu encouraged foreign trade but also was suspicious of outsiders. He wanted to make Edo a major port, but once he learned that the Europeans favored ports in Kyūshū and that China had rejected his plans for official trade, he moved to control existing trade and allowed only certain ports to handle specific kinds of commodities. The beginning of the Edo period coincides with the last decades of the Nanban trade period during which intense interaction with European powers, on the economic and religious plane, took place. It is at the beginning of the Edo period that Japan built its first ocean-going warships, such as the ''San Juan Bautista'', a 500- ton galleon-type ship that transported a Japanese embassy headed by Hasekura Tsunenaga to the Americas and then to Europe. Also during that period, the ''bakufu'' commissioned around 720 Red Seal Ships, three-masted and armed trade ships, for intra-Asian commerce. Japanese adventurers, such as Yamada Nagamasa, used those ships throughout Asia.

The beginning of the Edo period coincides with the last decades of the Nanban trade period during which intense interaction with European powers, on the economic and religious plane, took place. It is at the beginning of the Edo period that Japan built its first ocean-going warships, such as the ''San Juan Bautista'', a 500- ton galleon-type ship that transported a Japanese embassy headed by Hasekura Tsunenaga to the Americas and then to Europe. Also during that period, the ''bakufu'' commissioned around 720 Red Seal Ships, three-masted and armed trade ships, for intra-Asian commerce. Japanese adventurers, such as Yamada Nagamasa, used those ships throughout Asia. The "Christian problem" was, in effect, a problem of controlling both the Christian ''daimyo'' in Kyūshū and their trade with the Europeans. By 1612, the ''shōgun''s retainers and residents of Tokugawa lands had been ordered to forswear Christianity. More restrictions came in 1616 (the restriction of foreign trade to Nagasaki and Hirado, an island northwest of Kyūshū), 1622 (the execution of 120 missionaries and converts), 1624 (the expulsion of the Spanish), and 1629 (the execution of thousands of Christians). Finally, the

The "Christian problem" was, in effect, a problem of controlling both the Christian ''daimyo'' in Kyūshū and their trade with the Europeans. By 1612, the ''shōgun''s retainers and residents of Tokugawa lands had been ordered to forswear Christianity. More restrictions came in 1616 (the restriction of foreign trade to Nagasaki and Hirado, an island northwest of Kyūshū), 1622 (the execution of 120 missionaries and converts), 1624 (the expulsion of the Spanish), and 1629 (the execution of thousands of Christians). Finally, the Closed Country Edict of 1635

This Sakoku Edict (''Sakoku-rei'', 鎖国令) of 1635 was a Japanese decree intended to eliminate foreign influence, enforced by strict government rules and regulations to impose these ideas. It was the third of a series issued by Tokugawa Iemitsu ...

prohibited any Japanese from traveling outside Japan or, if someone left, from ever returning. In 1636, the Dutch were restricted to Dejima, a small artificial island—and thus, not true Japanese soil—in Nagasaki's harbor.

The shogunate perceived Christianity to be an extremely destabilizing factor, and so decided to target it. The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–1638, in which discontented Catholic samurai and peasants rebelled against the bakufu—and Edo called in Dutch ships to bombard the rebel stronghold—marked the end of the Christian movement. During the Shimabara Rebellion an estimated 37,000 people (mostly Christians) were massacred. In 50 years, the Tokugawa shoguns reduced the amount of Christians to near zero in Japan. However, some Christians survived by going underground, the so-called Kakure Kirishitan

''Kakure kirishitan'' () is a modern term for a member of the Catholic Church in Japan, Catholic Church in Japan that went underground at the start of the Edo period in the early 17th century due to Christianity's repression by the Tokugawa shog ...

. Soon thereafter, the Portuguese were permanently expelled, members of the Portuguese diplomatic mission were executed, all subjects were ordered to register at a Buddhist or Shinto temple, and the Dutch and Chinese were restricted, respectively, to Dejima and to a special quarter in Nagasaki. Besides small trade of some outer ''daimyo'' with Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republi ...

and the Ryukyu Islands, to the southwest of Japan's main islands, by 1641, foreign contacts were limited by the policy of '' sakoku'' to Nagasaki.

The last Jesuit was either killed or reconverted by 1644 and by the 1660s, Christianity was almost completely eradicated, and its external political, economic, and religious influence on Japan became quite limited. Only China, the Dutch East India Company, and for a short period, the English, enjoyed the right to visit Japan during this period, for commercial purposes only, and they were restricted to the Dejima port in Nagasaki. Other Europeans who landed on Japanese shores were put to death without trial.Society

cities

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

that were built around ''daimyo'' castles, each restricted to their own quarter. Edo society had an elaborate social structure, in which every family knew its place and level of prestige.

At the top were the Emperor and the court nobility, invincible in prestige but weak in power. Next came the shōgun, ''daimyo'' and layers of feudal lords whose rank was indicated by their closeness to the Tokugawa. They had power. The ''daimyo'' comprised about 250 local lords of local "han" with annual outputs of 50,000 or more bushels of rice. The upper strata was much given to elaborate and expensive rituals, including elegant architecture, landscaped gardens, Noh drama, patronage of the arts, and the tea ceremony.

Then came the 400,000 warriors, called "samurai", in numerous grades and degrees. A few upper samurai were eligible for high office; most were foot soldiers. Since there was very little fighting, they became civil servants paid by the daimyo, with minor duties. The samurai were affiliated with senior lords in a well-established chain of command. The shogun had 17,000 samurai retainers; the daimyo each had hundreds. Most lived in modest homes near their lord's headquarters, and lived off of hereditary rights and stipends. Together these high status groups comprised Japan's ruling class making up about 6% of the total population.

After a long period of inner conflict, the first goal of the newly established Tokugawa government was to pacify the country. It created a balance of power that remained (fairly) stable for the next 250 years, influenced by Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

principles of social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order ...

. Most samurai lost their direct possession of the land: the ''daimyo'' took over their land. The samurai had a choice: give up their sword and become peasants, or move to the city of their feudal lord and become a paid retainer. Only a few land samurai remained in the border provinces of the north, or as direct vassals of the ''shōgun'', the 5,000 so-called '' hatamoto''. The ''daimyo'' were put under tight control of the shogunate. Their families had to reside in Edo; the ''daimyo'' themselves had to reside in Edo for one year and in their province (''han'') for the next. This system was called ''sankin-kōtai

''Sankin-kōtai'' ( ja, 参覲交代/参覲交替, now commonly written as ja, 参勤交代/参勤交替, lit=alternate attendance, label=none) was a policy of the Tokugawa shogunate during most of the Edo period of Japanese history.Jansen, M ...

''.

Lower orders divided into two main segments—the peasants—80% of the population—whose high prestige as producers was undercut by their burden as the chief source of taxes. They were illiterate and lived in villages controlled by appointed officials who kept the peace and collected taxes.

The family was the smallest legal entity, and the maintenance of family status and privileges was of great importance at all levels of society. The individual had no separate legal rights. The 1711 ''Gotōke reijō'' was compiled from over 600 statutes promulgated between 1597 and 1696.

Outside the four classes were the so-called ''eta

Eta (uppercase , lowercase ; grc, ἦτα ''ē̂ta'' or ell, ήτα ''ita'' ) is the seventh letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the close front unrounded vowel . Originally denoting the voiceless glottal fricative in most dialects, ...

'' and ''hinin'', those whose professions broke the taboos of Buddhism. ''Eta'' were butchers, tanners and undertakers. ''Hinin'' served as town guards, street cleaners, and executioners. Other outsiders included the beggars, entertainers, and prostitutes. The word ''eta'' literally translates to "filthy" and ''hinin'' to "non-humans", a thorough reflection of the attitude held by other classes that the ''eta'' and ''hinin'' were not even people. ''Hinin'' were only allowed inside a special quarter of the city. Other persecution of the hinin included disallowing them from wearing robes longer than knee-length and the wearing of hats. Sometimes ''eta'' villages were not even printed on official maps. A sub-class of hinin who were born into their social class had no option of mobility to a different social class whereas the other class of hinin who had lost their previous class status could be reinstated in Japanese society. In the 19th century the umbrella term ''burakumin'' was coined to name the ''eta'' and ''hinin'' because both classes were forced to live in separate village neighborhoods. The ''eta'', ''hinin'' and ''burakumin'' classes were officially abolished in 1871. However, their cultural and societal impact, including some forms of discrimination, continues into modern times.

Economic development

The Edo period passed on a vital commercial sector to be in flourishing urban centers, a relatively well-educated elite, a sophisticated government bureaucracy, productive agriculture, a closely unified nation with highly developed financial and marketing systems, and a national infrastructure of roads. Economic development during the Tokugawa period included

The Edo period passed on a vital commercial sector to be in flourishing urban centers, a relatively well-educated elite, a sophisticated government bureaucracy, productive agriculture, a closely unified nation with highly developed financial and marketing systems, and a national infrastructure of roads. Economic development during the Tokugawa period included urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly t ...

, increased shipping of commodities, a significant expansion of domestic and, initially, foreign commerce, and a diffusion of trade and handicraft industries. The construction trades flourished, along with banking facilities and merchant associations. Increasingly, ''han'' authorities oversaw the rising agricultural production and the spread of rural handicrafts.

Population

By the mid-18th century, Edo had a population of more than one million, likely the biggest city in the world at the time.Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of ...

and Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ...

each had more than 400,000 inhabitants. Many other castle towns grew as well. Osaka and Kyoto became busy trading and handicraft production centers, while Edo was the center for the supply of food and essential urban consumer goods. Around the year 1700, Japan was perhaps the most urbanized country in the world, at a rate of around 10–12%. Half of that figure would be samurai, while the other half, consisting of merchants and artisans, would be known as ''chōnin''.

In the first part of the Edo period, Japan experienced rapid demographic growth, before leveling off at around 30 million.Hanley, S. B. (1968). Population trends and economic development in Tokugawa Japan: the case of Bizen province in Okayama. ''Daedalus'', 622-635. Between the 1720s and 1820s, Japan had almost zero population growth, often attributed to lower birth rates in response to widespread famine ( Great Tenmei famine 1782-1788), but some historians have presented different theories, such as a high rate of infanticide artificially controlling population. At around 1721, the population of Japan was close to 30 million and the figure was only around 32 million around the Meiji Restoration around 150 years later. From 1721, there were regular national surveys of the population until the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate. In addition, regional surveys, as well as religious records initially compiled to eradicate Christianity, also provide valuable demographic data.

Economy and financial services

The Tokugawa era brought peace, and that brought prosperity to a nation of 31 million, 80% of them rice farmers. Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720.One chō, or chobu, equals 2.45 acres. Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of water to their paddies. The daimyos operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade.

The system of ''sankin kōtai'' meant that daimyos and their families often resided in Edo or travelled back to their domains, giving demand to an enormous consumer market in Edo and trade throughout the country. Samurai and daimyos, after prolonged peace, are accustomed to more elaborate lifestyles. To keep up with growing expenditures, the ''bakufu'' and daimyos often encouraged commercial crops and artifacts within their domains, from textiles to tea. The concentration of wealth also led to the development of financial markets. As the shogunate only allowed ''daimyos'' to sell surplus rice in Edo and Osaka, large-scale rice markets developed there. Each daimyo also had a capital city, located near the one castle they were allowed to maintain. Daimyos would have agents in various commercial centers, selling rice and cash crops, often exchanged for paper credit to be redeemed elsewhere. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, and currency came into common use. In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services.

The Tokugawa era brought peace, and that brought prosperity to a nation of 31 million, 80% of them rice farmers. Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720.One chō, or chobu, equals 2.45 acres. Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of water to their paddies. The daimyos operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade.

The system of ''sankin kōtai'' meant that daimyos and their families often resided in Edo or travelled back to their domains, giving demand to an enormous consumer market in Edo and trade throughout the country. Samurai and daimyos, after prolonged peace, are accustomed to more elaborate lifestyles. To keep up with growing expenditures, the ''bakufu'' and daimyos often encouraged commercial crops and artifacts within their domains, from textiles to tea. The concentration of wealth also led to the development of financial markets. As the shogunate only allowed ''daimyos'' to sell surplus rice in Edo and Osaka, large-scale rice markets developed there. Each daimyo also had a capital city, located near the one castle they were allowed to maintain. Daimyos would have agents in various commercial centers, selling rice and cash crops, often exchanged for paper credit to be redeemed elsewhere. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, and currency came into common use. In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services. The merchants benefited enormously, especially those with official patronage. However, the Neo-Confucian ideology of the shogunate focused the virtues of frugality and hard work; it had a rigid class system, which emphasized agriculture and despised commerce and merchants. A century after the Shogunate's establishment, problems began to emerge. The samurai, forbidden to engage in farming or business but allowed to borrow money, borrowed too much, some taking up side jobs as bodyguards for merchants, debt collectors, or artisans. The ''bakufu'' and ''daimyos'' raised taxes on farmers, but did not tax business, so they too fell into debt, with some merchants specializing in loaning to daimyos. Yet it was inconceivable to systematically tax commerce, as it would make money off "parasitic" activities, raise the prestige of merchants, and lower the status of government. As they paid no regular taxes, the forced financial contributions to the daimyos were seen by some merchants as a cost of doing business. The wealth of merchants gave them a degree of prestige and even power over the daimyos.

By 1750, rising taxes incited peasant unrest and even revolt. The nation had to deal somehow with samurai impoverishment and treasury deficits. The financial troubles of the samurai undermined their loyalties to the system, and the empty treasury threatened the whole system of government. One solution was reactionary—cutting samurai salaries and prohibiting spending for luxuries. Other solutions were modernizing, with the goal of increasing agrarian productivity. The eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (in office 1716–1745) had considerable success, though much of his work had to be done again between 1787 and 1793 by the shogun's chief councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829). Other shoguns debased the coinage to pay debts, which caused inflation. Overall, while commerce (domestic and international) was vibrant and sophisticated financial services had developed in the Edo period, the shogunate remained ideologically focused on honest agricultural work as the basis of society and never sought to develop a mercantile or capitalistic country.

By 1800, the commercialization of the economy grew rapidly, bringing more and more remote villages into the national economy. Rich farmers appeared who switched from rice to high-profit commercial crops and engaged in local money-lending, trade, and small-scale manufacturing. Wealthy merchants were often forced to "lend" money to the shogunate or daimyos (often never returned). They often had to hide their wealth, and some sought higher social status by using money to marry into the samurai class. There is some evidence that as merchants gained greater political influence in the late Edo period, the rigid class division between samurai and merchants began to break down.

A few domains, notably Chōsū and Satsuma, used innovative methods to restore their finances, but most sunk further into debt. The financial crisis provoked a reactionary solution near the end of the "Tempo era" (1830-1843) promulgated by the chief counselor Mizuno Tadakuni. He raised taxes, denounced luxuries and tried to impede the growth of business; he failed and it appeared to many that the continued existence of the entire Tokugawa system was in jeopardy.

The merchants benefited enormously, especially those with official patronage. However, the Neo-Confucian ideology of the shogunate focused the virtues of frugality and hard work; it had a rigid class system, which emphasized agriculture and despised commerce and merchants. A century after the Shogunate's establishment, problems began to emerge. The samurai, forbidden to engage in farming or business but allowed to borrow money, borrowed too much, some taking up side jobs as bodyguards for merchants, debt collectors, or artisans. The ''bakufu'' and ''daimyos'' raised taxes on farmers, but did not tax business, so they too fell into debt, with some merchants specializing in loaning to daimyos. Yet it was inconceivable to systematically tax commerce, as it would make money off "parasitic" activities, raise the prestige of merchants, and lower the status of government. As they paid no regular taxes, the forced financial contributions to the daimyos were seen by some merchants as a cost of doing business. The wealth of merchants gave them a degree of prestige and even power over the daimyos.

By 1750, rising taxes incited peasant unrest and even revolt. The nation had to deal somehow with samurai impoverishment and treasury deficits. The financial troubles of the samurai undermined their loyalties to the system, and the empty treasury threatened the whole system of government. One solution was reactionary—cutting samurai salaries and prohibiting spending for luxuries. Other solutions were modernizing, with the goal of increasing agrarian productivity. The eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (in office 1716–1745) had considerable success, though much of his work had to be done again between 1787 and 1793 by the shogun's chief councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829). Other shoguns debased the coinage to pay debts, which caused inflation. Overall, while commerce (domestic and international) was vibrant and sophisticated financial services had developed in the Edo period, the shogunate remained ideologically focused on honest agricultural work as the basis of society and never sought to develop a mercantile or capitalistic country.

By 1800, the commercialization of the economy grew rapidly, bringing more and more remote villages into the national economy. Rich farmers appeared who switched from rice to high-profit commercial crops and engaged in local money-lending, trade, and small-scale manufacturing. Wealthy merchants were often forced to "lend" money to the shogunate or daimyos (often never returned). They often had to hide their wealth, and some sought higher social status by using money to marry into the samurai class. There is some evidence that as merchants gained greater political influence in the late Edo period, the rigid class division between samurai and merchants began to break down.

A few domains, notably Chōsū and Satsuma, used innovative methods to restore their finances, but most sunk further into debt. The financial crisis provoked a reactionary solution near the end of the "Tempo era" (1830-1843) promulgated by the chief counselor Mizuno Tadakuni. He raised taxes, denounced luxuries and tried to impede the growth of business; he failed and it appeared to many that the continued existence of the entire Tokugawa system was in jeopardy.

Agriculture

Rice was the base of the economy. About 80% of the people were rice farmers. Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable, so prosperity increased. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720. Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of irrigation to their paddies. The ''daimyo'' operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade. Large-scale rice markets developed, centered on Edo and Ōsaka. In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services. The merchants, while low in status, prospered, especially those with official patronage. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, currency came into common use, and the strengthening credit market encouraged entrepreneurship. The ''daimyo'' collected the taxes from the peasants in the form of rice. Taxes were high, often at around 40%-50% of the harvest. The rice was sold at the '' fudasashi'' market in Edo. To raise money, the ''daimyo'' used forward contracts to sell rice that was not even harvested yet. These contracts were similar to modern futures trading. It was during the Edo period that Japan developed an advanced forest management policy. Increased demand for timber resources for construction, shipbuilding and fuel had led to widespread deforestation, which resulted in forest fires, floods and soil erosion. In response the ''shōgun'', beginning around 1666, instituted a policy to reduce logging and increase the planting of trees. The policy mandated that only the ''shōgun'' and ''daimyo'' could authorize the use of wood. By the 18th century, Japan had developed detailed scientific knowledge about silviculture and plantation forestry.Artistic and intellectual development

Education

The first shogun Ieyasu set up Confucian academies in his ''

The first shogun Ieyasu set up Confucian academies in his ''shinpan

was a class of ''daimyō'' in the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan who were certain relatives of the ''Shōgun''.

While all ''shinpan'' were relatives of the ''shōgun'', not all relatives of the shōgun were ''shinpan''; an example of this is the ...

'' domains and other ''daimyos'' followed suit in their own domains, establishing what's known as ''han'' schools (藩校, ''hankō'').Hane, Mikiso. ''Premodern Japan: A historical survey''. Routledge, 2018. Within a generation, almost all samurai were literate, as their careers often required knowledge of literary arts. These academies were staffed mostly with other samurai, along with some buddhist and shinto clergymen who were also learned in Neo-Confucianism and the works of Zhu Xi. Beyond kanji

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese and are still used, along with the subse ...

(Chinese characters), the Confucian classics, calligraphy, basic arithmetics, and etiquette, the samurai also learned various martial arts and military skills in schools.

The '' chōnin'' (urban merchants and artisans) patronized neighborhood schools called '' terakoya'' (寺子屋, "temple schools"). Despite being located in temples, the ''terakoya'' curriculum consisted of basic literacy and arithmetic, instead of literary arts or philosophy. High rates of urban literacy in Edo contributed to the prevalence of novels and other literary forms. In urban areas, children are often taught by masterless samurai, while in rural areas priests from Buddhist temples or Shinto shrines often did the teaching. Unlike in the cities, in rural Japan, only children of prominent farmers would receive education.

In Edo, the shogunate set up several schools under its direct patronage, the most important being the neo-Confucian acting as a de facto elite school for its bureaucracy but also creating a network of alumni from the whole country. Besides Shoheikō, other important directly-run schools at the end of the shogunate included the , specialized in Japanese domestic history and literature, influencing the rise of kokugaku, and the , focusing on Chinese medicine.

One estimate of literacy in Edo suggest that up to a third of males could read, along with a sixth of women. Another estimate states that 40% of men and 10% of women by the end of the Edo period were literate. According to another estimate, around 1800, almost 100% of the samurai class and about 50% to 60% of the '' chōnin'' (craftsmen and merchants) class and ''nōmin'' (peasants) class were literate. Some historians partially credited Japan's relatively high literacy rates for its fast development after the Meiji Restoration.

As the literacy rate was so high that many ordinary people could read books, books in various genres such as cooking, gardening, travel guides, art books, scripts of '' bunraku'' (puppet theatre), '' kibyōshi'' (satirical novels), '' sharebon'' (books on urban culture), '' kokkeibon'' (comical books), '' ninjōbon'' (romance novel), '' yomihon'' and '' kusazōshi'' were published. There were 600 to 800 rental bookstores in Edo, and people borrowed or bought these woodblock print books. The best-selling books in this period were ''Kōshoku Ichidai Otoko'' (''Life of an Amorous Man'') by Ihara Saikaku, '' Nansō Satomi Hakkenden'' by Takizawa Bakin and '' Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige'' by Jippensha Ikku and these books were reprinted many times.Edo Picture Books and the Edo Period.National Diet Library.''第6回 和本の楽しみ方4 江戸の草紙'' p.3.

Konosuke Hashiguchi. (2013) Seikei University.

Philosophy and religion

The flourishing of Neo-Confucianism was the major intellectual development of the Tokugawa period. Confucian studies had long been kept active in Japan byBuddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

clerics, but during the Tokugawa period, Confucianism emerged from Buddhist religious control. This system of thought increased attention to a secular view of man and society. The ethical humanism, rationalism, and historical perspective of neo-Confucian doctrine appealed to the official class. By the mid-17th century, neo-Confucianism was Japan's dominant legal philosophy and contributed directly to the development of the '' kokugaku'' (national learning) school of thought. Advanced studies and growing applications of neo-Confucianism contributed to the transition of the social and political order from feudal norms to class- and large-group-oriented practices. The rule of the people or Confucian man was gradually replaced by the rule of law. New laws were developed, and new administrative devices were instituted. A new theory of government and a new vision of society emerged as a means of justifying more comprehensive governance by the bakufu. Each person had a distinct place in society and was expected to work to fulfill his or her mission in life. The people were to be ruled with benevolence by those whose assigned duty it was to rule. Government was all-powerful but responsible and humane. Although the class system was influenced by neo-Confucianism, it was not identical to it. Whereas soldiers and clergy were at the bottom of the hierarchy in the Chinese model, in Japan, some members of these classes constituted the ruling elite.

Members of the samurai class adhered to bushi traditions with a renewed interest in Japanese history and cultivation of the ways of Confucian scholar-administrators. A distinct culture known as ''