Ede Teller on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

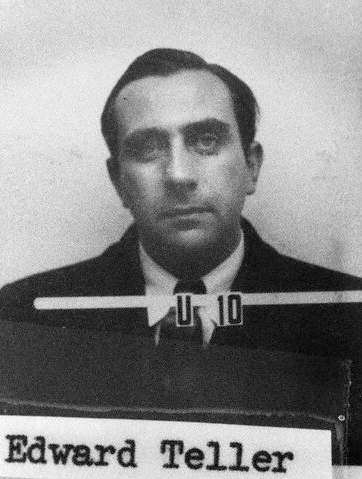

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory '' numerus clausus'' rule under Miklós Horthy's regime. The political climate and revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering animosity for both Communism and Fascism in Teller.

From 1926 to 1928, Teller studied mathematics and chemistry at the

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory '' numerus clausus'' rule under Miklós Horthy's regime. The political climate and revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering animosity for both Communism and Fascism in Teller.

From 1926 to 1928, Teller studied mathematics and chemistry at the

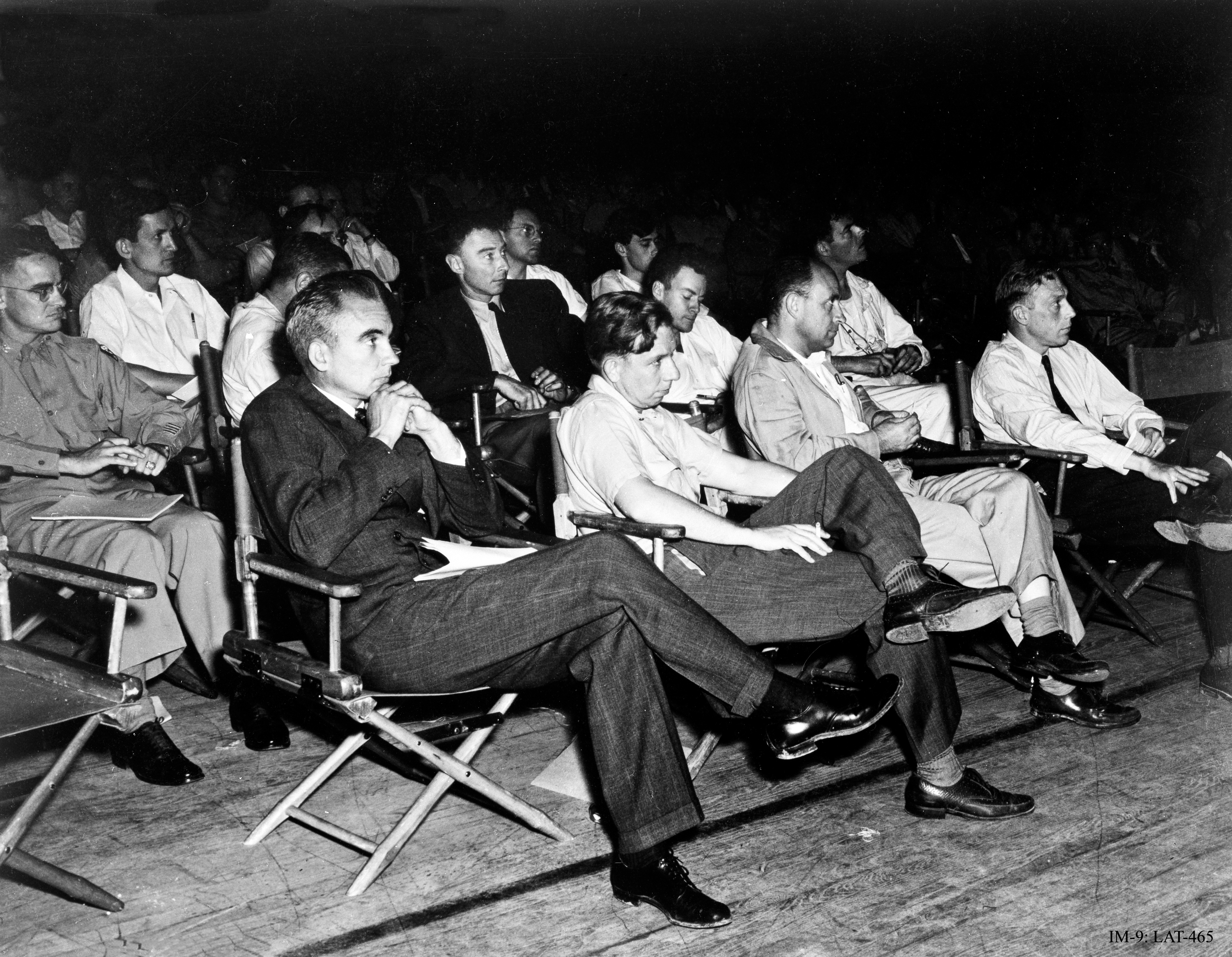

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium and the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed. It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium and the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed. It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during  By 1949, Soviet-backed governments had already begun seizing control throughout Eastern Europe, forming such puppet states as the Hungarian People's Republic in Teller's homeland of Hungary, where much of his family still lived, on August 20, 1949. Following the Soviet Union's first test detonation of an atomic bomb on August 29, 1949, President Harry Truman announced a crash development program for a

By 1949, Soviet-backed governments had already begun seizing control throughout Eastern Europe, forming such puppet states as the Hungarian People's Republic in Teller's homeland of Hungary, where much of his family still lived, on August 20, 1949. Following the Soviet Union's first test detonation of an atomic bomb on August 29, 1949, President Harry Truman announced a crash development program for a  Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory, which had been created largely through his urging. After the detonation of Ivy Mike, the first thermonuclear weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration, on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds—and instead saw its results on a

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory, which had been created largely through his urging. After the detonation of Ivy Mike, the first thermonuclear weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration, on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds—and instead saw its results on a

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney Roger Robb whether he was planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States", Teller replied that:

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney Roger Robb whether he was planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States", Teller replied that:

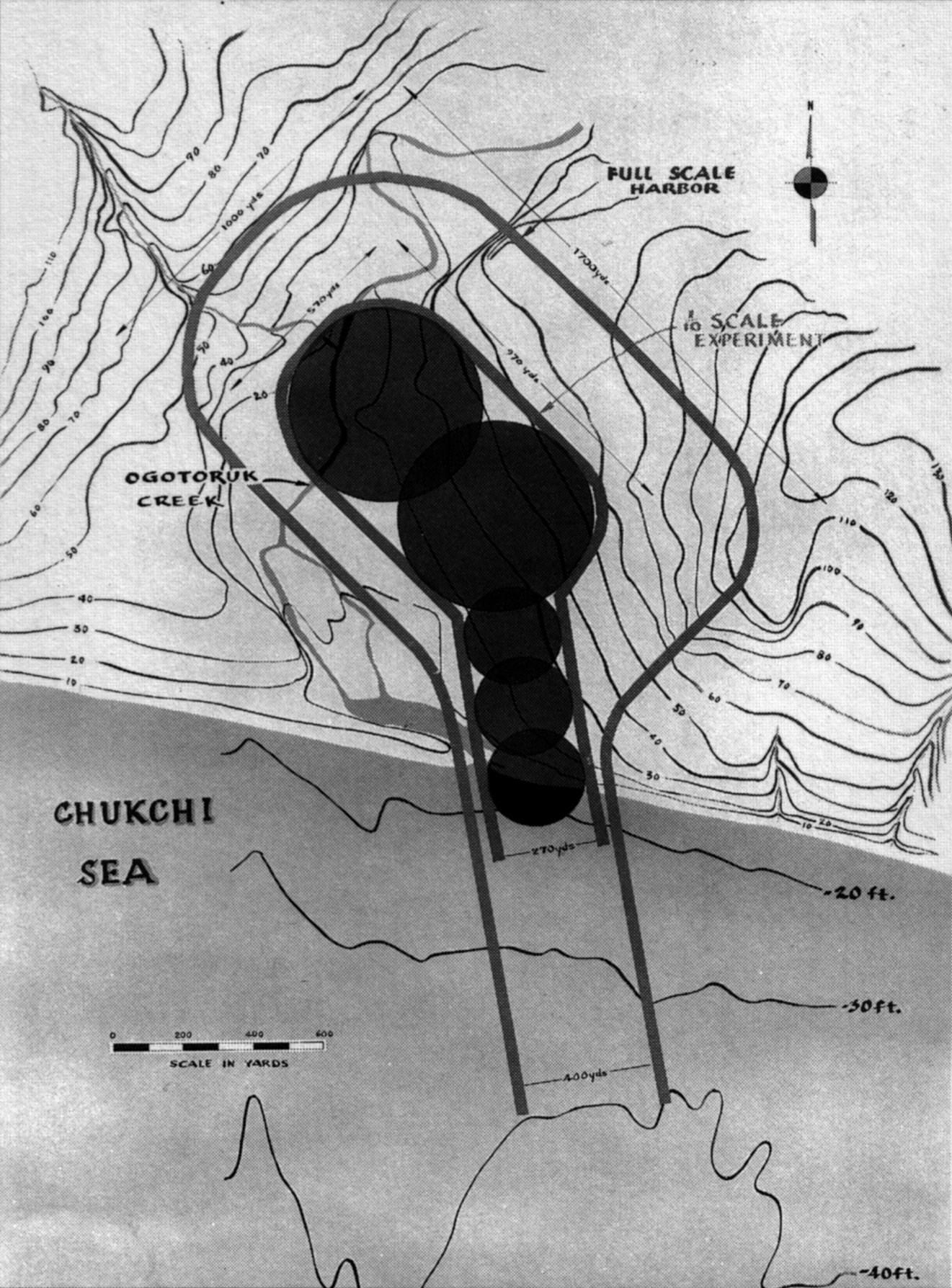

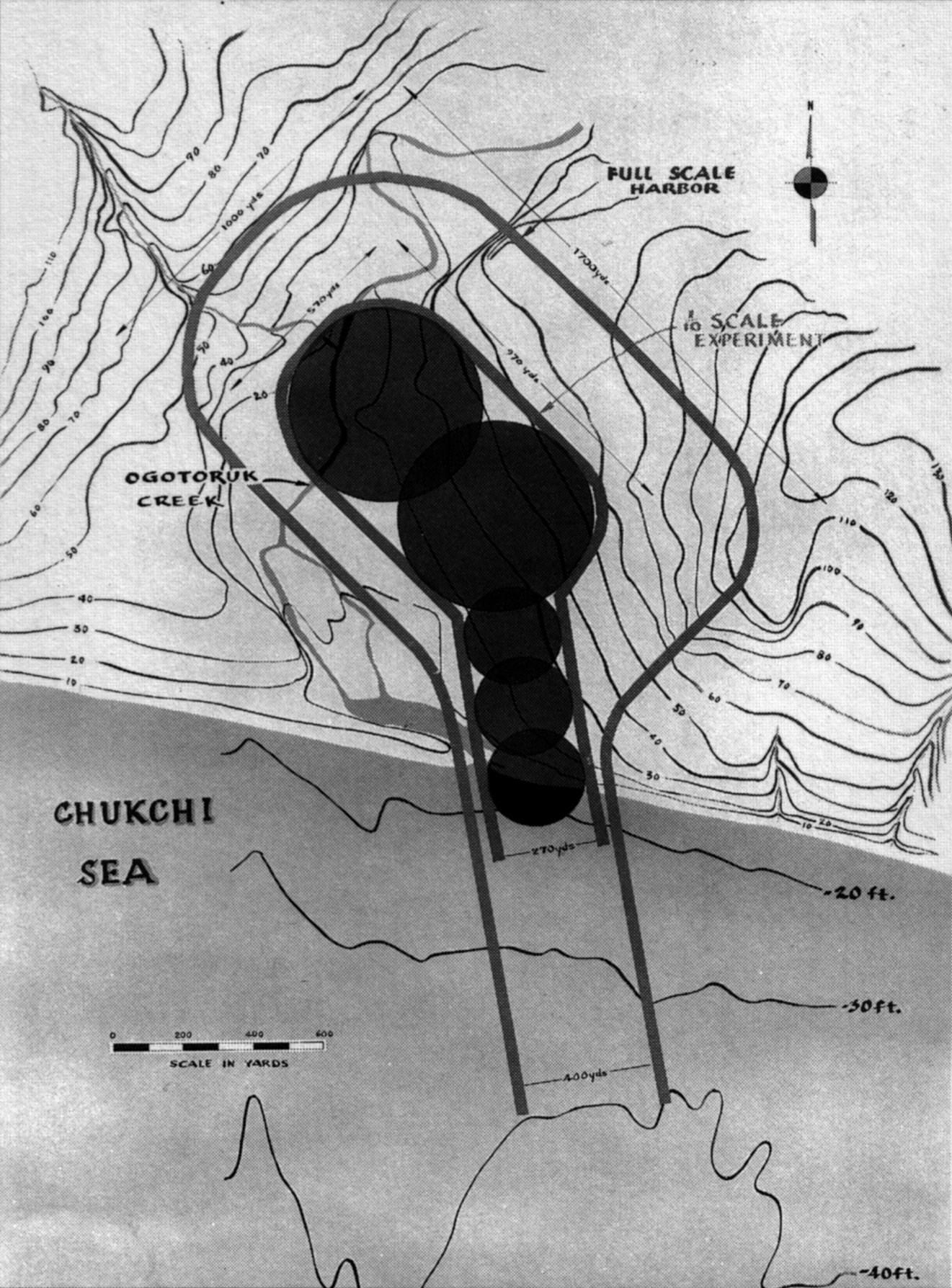

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare. One of the most controversial projects he proposed was a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through Point Hope, Alaska. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project Chariot. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site, and having withdrawn the land from the public domain, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders that the plan was financially viable.

Other scientists criticized the project as being potentially unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living near the designated area, who were not officially told of the plan until March 1960. Additionally, it turned out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility of the project and the concerns over radiation-related health issues, the project was abandoned in 1962.

A related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands in northern Alberta with nuclear explosions, titled Project Oilsands. The plan actually received the endorsement of the Alberta government, but was rejected by the Government of Canada under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who was opposed to having any nuclear weapons in Canada. After Diefenbaker was out of office, Canada went on to have nuclear weapons, from a US nuclear sharing agreement, from 1963 to 1984.

Teller also proposed the use of nuclear bombs to prevent damage from powerful hurricanes. He argued that when conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are right for the formation of hurricanes, the heat generated by well-placed nuclear explosions could trigger several small hurricanes, rather than waiting for nature to build one large one.

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare. One of the most controversial projects he proposed was a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through Point Hope, Alaska. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project Chariot. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site, and having withdrawn the land from the public domain, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders that the plan was financially viable.

Other scientists criticized the project as being potentially unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living near the designated area, who were not officially told of the plan until March 1960. Additionally, it turned out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility of the project and the concerns over radiation-related health issues, the project was abandoned in 1962.

A related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands in northern Alberta with nuclear explosions, titled Project Oilsands. The plan actually received the endorsement of the Alberta government, but was rejected by the Government of Canada under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who was opposed to having any nuclear weapons in Canada. After Diefenbaker was out of office, Canada went on to have nuclear weapons, from a US nuclear sharing agreement, from 1963 to 1984.

Teller also proposed the use of nuclear bombs to prevent damage from powerful hurricanes. He argued that when conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are right for the formation of hurricanes, the heat generated by well-placed nuclear explosions could trigger several small hurricanes, rather than waiting for nature to build one large one.

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the

/ref> In order to safeguard the earth, the theoretical 1 Gt device would weigh about 25–30 tons—light enough to be lifted on the Russian

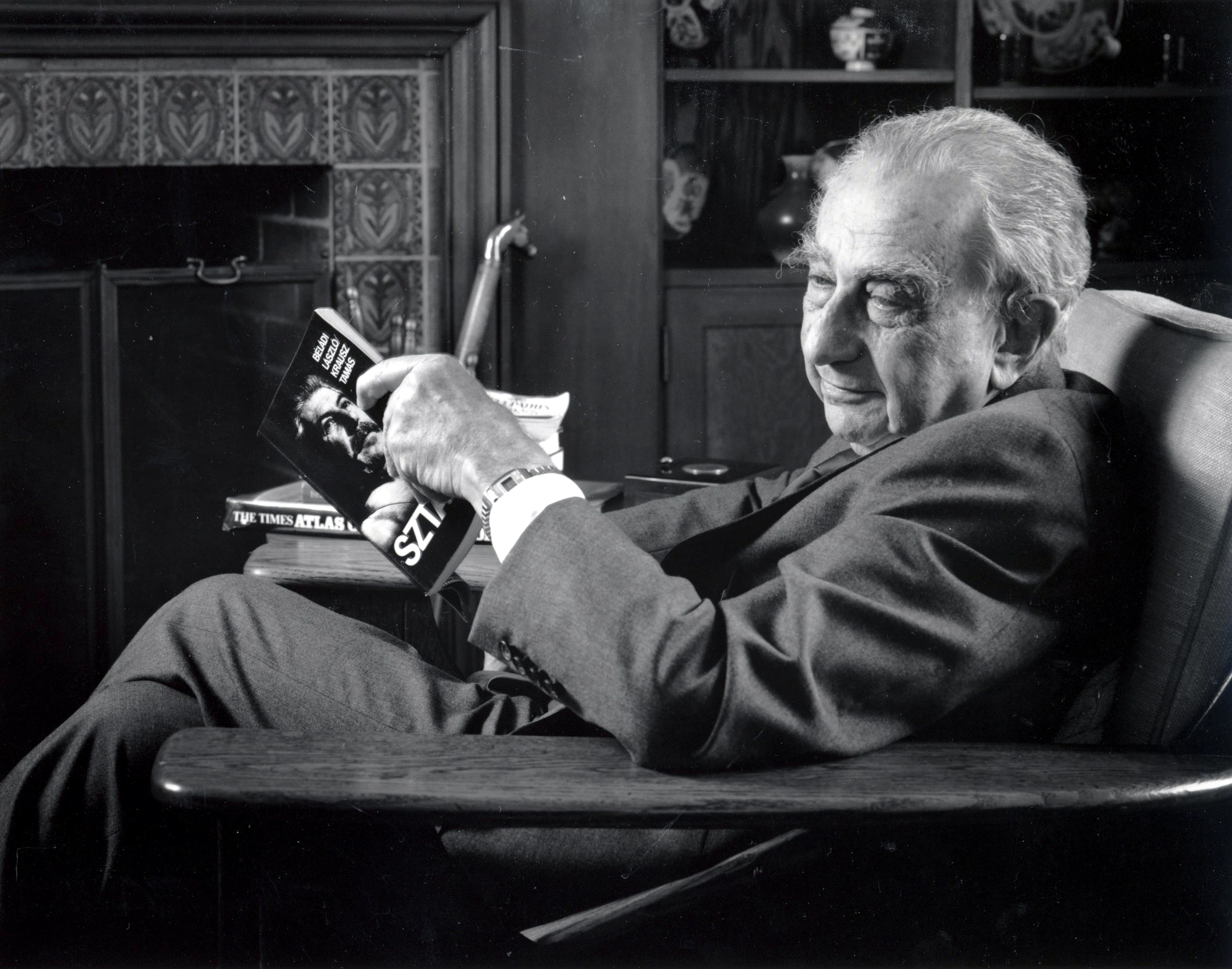

Teller died in Stanford, California, on September 9, 2003, at the age of 95. He had suffered a

Teller died in Stanford, California, on September 9, 2003, at the age of 95. He had suffered a

The Constructive Uses of Nuclear Explosions

' (1968) * ''Energy from Heaven and Earth'' (1979) * ''The Pursuit of Simplicity'' (1980) * ''Better a Shield Than a Sword: Perspectives on Defense and Technology'' (1987) * ''Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics'' (1991), with Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley * ''Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics'' (2001), with Judith Shoolery

Russian text (free download)

* * * * * * * * * * *

Science and Technology Review

' contains 10 articles written primarily by Stephen B. Libby in 2007, about Edward Teller's life and contributions to science, to commemorate the 2008 centennial of his birth. * ''Heisenberg Sabotaged the Atomic Bomb'' (''Heisenberg hat die Atombombe sabotiert'') an interview in German with Edward Teller in: Michael Schaaf: ''Heisenberg, Hitler und die Bombe. Gespräche mit Zeitzeugen'' Berlin 2001, . * * Szilard, Leo. (1987) ''Toward a Livable World: Leo Szilard and the Crusade for Nuclear Arms Control''. Cambridge: MIT Press.

1986 Audio Interview with Edward Teller by S. L. Sanger

Voices of the Manhattan Project

Annotated Bibliography for Edward Teller from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

interview with Richard Rhodes

Edward Teller Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

A radio interview with Edward Teller

Aired on the

The Paternity of the H-Bombs: Soviet-American Perspectives

Edward Teller tells his life story at Web of Stories

(video) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Teller, Edward 1908 births 2003 deaths American agnostics American amputees American nuclear physicists American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent Enrico Fermi Award recipients Fasori Gimnázium alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Fellows of the American Physical Society Founding members of the World Cultural Council George Washington University faculty Hungarian agnostics Hungarian amputees Hungarian emigrants to the United States Hungarian Jews 20th-century Hungarian physicists Members of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science Israeli nuclear development Jewish agnostics Jewish American scientists Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States Jewish physicists Karlsruhe Institute of Technology alumni Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory staff Leipzig University alumni Manhattan Project people Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Medal of Science laureates Nuclear proliferation Scientists from Budapest Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Theoretical physicists University of California, Berkeley faculty University of Chicago faculty University of Göttingen faculty Zionists Time Person of the Year

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for the title, considering it to be in poor taste. Throughout his life, Teller was known both for his scientific ability and for his difficult interpersonal relations and volatile personality.

Born in Hungary in 1908, Teller emigrated to the United States in the 1930s, one of the many so-called "Martians", a group of prominent Hungarian scientist émigrés. He made numerous contributions to nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

and molecular physics, spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter wa ...

(in particular the Jahn–Teller and Renner–Teller effects), and surface physics

Surface science is the study of physical and chemical phenomena that occur at the interface of two phases, including solid– liquid interfaces, solid–gas interfaces, solid–vacuum interfaces, and liquid–gas interfaces. It includes the f ...

. His extension of Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

's theory of beta decay, in the form of Gamow–Teller transitions, provided an important stepping stone in its application, while the Jahn–Teller effect and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory have retained their original formulation and are still mainstays in physics and chemistry.

Teller also made contributions to Thomas–Fermi theory, the precursor of density functional theory, a standard modern tool in the quantum mechanical treatment of complex molecules. In 1953, along with Nicholas Metropolis, Arianna Rosenbluth, Marshall Rosenbluth

Marshall Nicholas Rosenbluth (5 February 1927 – 28 September 2003) was an American plasma physicist and member of the National Academy of Sciences, and member of the American Philosophical Society. In 1997 he was awarded the National Medal of ...

, and his wife Augusta Teller, Teller co-authored a paper that is a standard starting point for the applications of the Monte Carlo method to statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic be ...

and the Markov chain Monte Carlo literature in Bayesian statistics. Teller was an early member of the Manhattan Project, charged with developing the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. He made a serious push to develop the first fusion-based weapons as well, but these were deferred until after World War II. He co-founded the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

, and was both its director and associate director for many years. After his controversial negative testimony in the Oppenheimer security hearing convened against his former Los Alamos Laboratory superior, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Teller was ostracized by much of the scientific community.

Teller continued to find support from the U.S. government and military research establishment, particularly for his advocacy for nuclear energy

Nuclear energy may refer to:

*Nuclear power, the use of sustained nuclear fission or nuclear fusion to generate heat and electricity

* Nuclear binding energy, the energy needed to fuse or split a nucleus of an atom

*Nuclear potential energy

...

development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

program. In his later years, he became especially known for his advocacy of controversial technological solutions to both military and civilian problems, including a plan to excavate an artificial harbor in Alaska using thermonuclear explosive in what was called Project Chariot, and Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

's Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derisively nicknamed the "''Star Wars'' program", was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic strategic nuclear weapons (intercontinental ballistic ...

. Teller was a recipient of numerous awards, including the Enrico Fermi Award and Albert Einstein Award

The Albert Einstein Award (sometimes mistakenly called the ''Albert Einstein Medal'' because it was accompanied with a gold medal) was an award in theoretical physics, given periodically from 1951 to 1979, that was established to recognize high ac ...

. He died on September 9, 2003, in Stanford, California, at 95.

Early life and work

Ede Teller was born on January 15, 1908, in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, into a Jewish family. His parents were Ilona (née Deutsch), a pianist, and Max Teller, an attorney. He attended the Fasori Lutheran Gymnasium, then in the Lutheran Minta (Model) Gymnasium in Budapest. Of Jewish origin, later in life Teller became an agnostic Jew. "Religion was not an issue in my family", he later wrote, "indeed, it was never discussed. My only religious training came because the Minta required that all students take classes in their respective religions. My family celebrated one holiday, the Day of Atonement, when we all fasted. Yet my father said prayers for his parents on Saturdays and on all the Jewish holidays. The idea of God that I absorbed was that it would be wonderful if He existed: We needed Him desperately but had not seen Him in many thousands of years." Teller was a late talker and developed the ability to speak later than most children, but became very interested in numbers, and would calculate large numbers in his head for fun. Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory '' numerus clausus'' rule under Miklós Horthy's regime. The political climate and revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering animosity for both Communism and Fascism in Teller.

From 1926 to 1928, Teller studied mathematics and chemistry at the

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory '' numerus clausus'' rule under Miklós Horthy's regime. The political climate and revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering animosity for both Communism and Fascism in Teller.

From 1926 to 1928, Teller studied mathematics and chemistry at the University of Karlsruhe

The Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT; german: Karlsruher Institut für Technologie) is a public research university in Karlsruhe, Germany. The institute is a national research center of the Helmholtz Association.

KIT was created in 2009 w ...

, where he graduated with a bachelor of science in chemical engineering. He once stated that the person who was responsible for his becoming a physicist was Herman Mark

Herman Francis Mark (May 3, 1895, Vienna – April 6, 1992, Austin, Texas) was an Austrian-American chemist regarded for his contributions to the development of polymer science. Mark's x-ray diffraction work on the molecular structure of fibers ...

, who was a visiting professor, after hearing lectures on molecular spectroscopy where Mark made it clear to him that it was new ideas in physics that were radically changing the frontier of chemistry. Mark was an expert in polymer chemistry, a field which is essential to understanding biochemistry, and Mark taught him about the leading breakthroughs in quantum physics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, qua ...

made by Louis de Broglie, among others. It was this exposure which he had gotten from Mark's lectures which motivated Teller to switch to physics. After informing his father of his intent to switch, his father was so concerned that he traveled to visit him and speak with his professors at the school. While a degree in chemical engineering was a sure path to a well-paying job at chemical companies, there was not such a clear-cut route for a career with a degree in physics. He was not privy to the discussions his father had with his professors, but the result was that he got his father's permission to become a physicist.

Teller then attended the University of Munich where he studied physics under Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld, (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in atomic and quantum physics, and also educated and mentored many students for the new era of theoretica ...

. On July 14, 1928, while still a young student in Munich, he was taking a streetcar to catch a train for a hike in the nearby Alps and decided to jump off while it was still moving. He fell, and the wheel severed most of his right foot. For the rest of his life, he walked with a permanent limp, and on occasion he wore a prosthetic foot. The painkillers he was taking were interfering with his thinking, so he decided to stop taking them, instead using his willpower to deal with the pain, including use of the placebo effect where he would convince himself that he had taken painkillers while drinking only water. Werner Heisenberg said that it was the hardiness of Teller's spirit, rather than stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

, that allowed him to cope so well with the accident.

In 1929, Teller transferred to the University of Leipzig where in 1930, he received his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

in physics under Heisenberg. Teller's dissertation dealt with one of the first accurate quantum mechanical treatments of the hydrogen molecular ion. That year, he befriended Russian physicists George Gamow and Lev Landau. Teller's lifelong friendship with a Czech physicist, George Placzek

George Placzek (; September 26, 1905 – October 9, 1955) was a Moravian physicist.

Biography

Placzek was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Brünn, Moravia (now Brno, Czech Republic), the grandson of Chief Rabbi Baruch Placzek.PDF He studied ...

, was also very important for his scientific and philosophical development. It was Placzek who arranged a summer stay in Rome with Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

in 1932, thus orienting Teller's scientific career in nuclear physics. Also in 1930, Teller moved to the University of Göttingen, then one of the world's great centers of physics due to the presence of Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German physicist and mathematician who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics and supervised the work of a n ...

and James Franck, but after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

in January 1933, Germany became unsafe for Jewish people, and he left through the aid of the International Rescue Committee

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) is a global humanitarian aid, relief, and development nongovernmental organization. Founded in 1933 as the International Relief Association, at the request of Albert Einstein, and changing its name in 19 ...

. He went briefly to England, and moved for a year to Copenhagen, where he worked under Niels Bohr. In February 1934 he married his long-time girlfriend Augusta Maria "Mici" (pronounced "Mitzi") Harkanyi, who was the sister of a friend. Since Mici was a Calvinist Christian, Edward and her were married in a Calvinist church. He returned to England in September 1934.

Mici had been a student in Pittsburgh, and wanted to return to the United States. Her chance came in 1935, when, thanks to George Gamow, Teller was invited to the United States to become a professor of physics at George Washington University, where he worked with Gamow until 1941. At George Washington University in 1937, Teller predicted the Jahn–Teller effect

The Jahn–Teller effect (JT effect or JTE) is an important mechanism of spontaneous symmetry breaking in molecular and solid-state systems which has far-reaching consequences in different fields, and is responsible for a variety of phenomena in sp ...

, which distorts molecules in certain situations; this affects the chemical reactions of metals, and in particular the coloration of certain metallic dyes. Teller and Hermann Arthur Jahn

Hermann Arthur Jahn (born 31 May 1907, Colchester, England; d. 24 October 1979 Southampton) was a British scientist of German descent. With Edward Teller, he identified the Jahn–Teller effect.

Early life

He was the son of Friedrich Wilhelm Herm ...

analyzed it as a piece of purely mathematical physics. In collaboration with Stephen Brunauer Stephen Brunauer (February 12, 1903 – July 6, 1986) was an American research chemist, government scientist, and university teacher. He resigned from his position with the U.S. Navy during the McCarthy era, when he found it impossible to refute ano ...

and Paul Hugh Emmett

Paul Hugh Emmett (September 22, 1900 – April 22, 1985) was an American chemist best known for his pioneering work in the field of catalysis and for his work on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He spearheaded the research to separate is ...

, Teller also made an important contribution to surface physics and chemistry: the so-called Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) isotherm. Teller and Mici became naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

citizens of the United States on March 6, 1941.

When World War II began, Teller wanted to contribute to the war effort. On the advice of the well-known Caltech aerodynamicist and fellow Hungarian émigré Theodore von Kármán, Teller collaborated with his friend Hans Bethe in developing a theory of shock-wave propagation. In later years, their explanation of the behavior of the gas behind such a wave proved valuable to scientists who were studying missile re-entry.

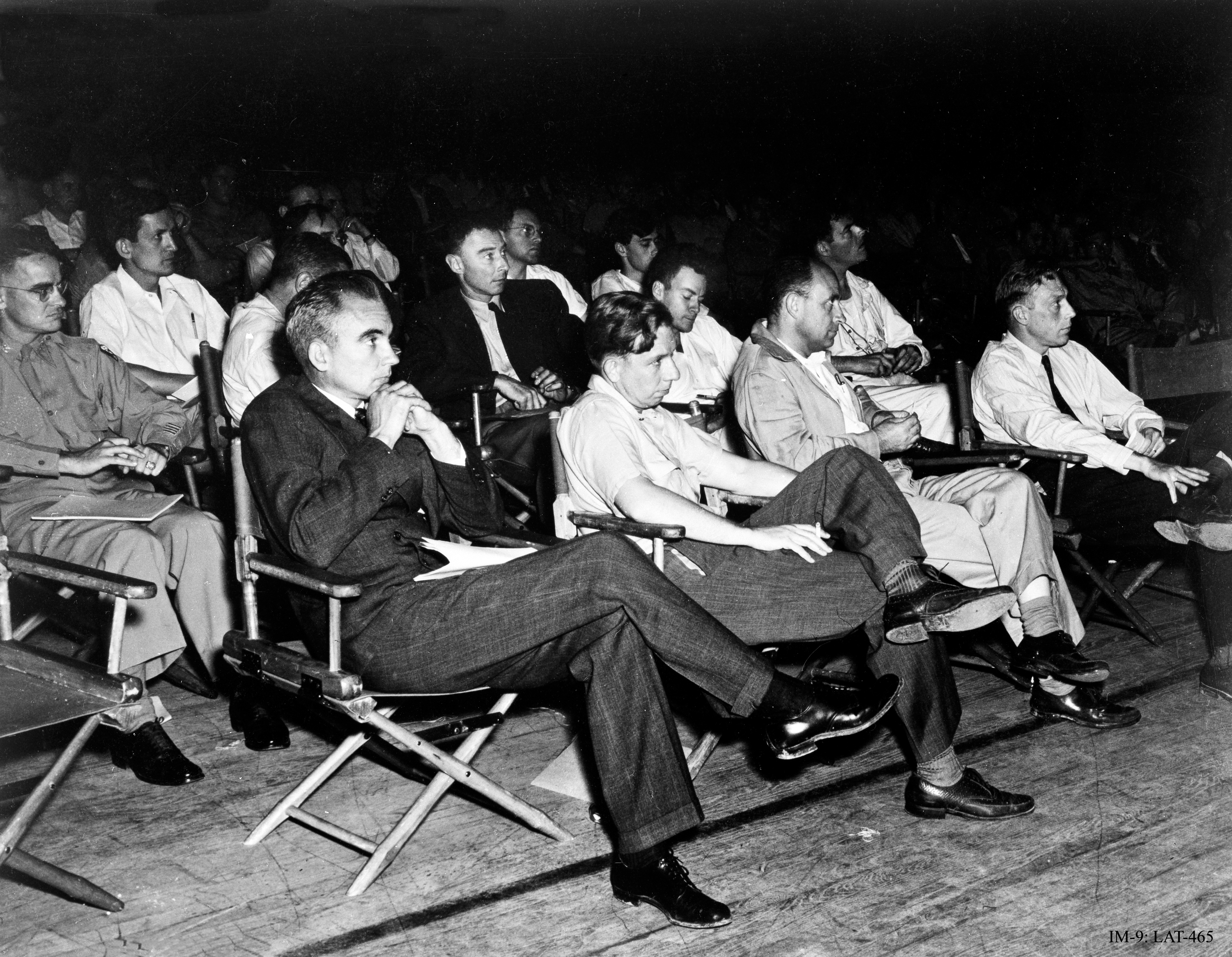

Manhattan Project

Los Alamos Laboratory

In 1942, Teller was invited to be part of Robert Oppenheimer's summer planning seminar, at the University of California, Berkeley for the origins of the Manhattan Project, theAllied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

effort to develop the first nuclear weapons. A few weeks earlier, Teller had been meeting with his friend and colleague Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

about the prospects of atomic warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear wa ...

, and Fermi had nonchalantly suggested that perhaps a weapon based on nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

could be used to set off an even larger nuclear fusion reaction. Even though he initially explained to Fermi why he thought the idea would not work, Teller was fascinated by the possibility and was quickly bored with the idea of "just" an atomic bomb even though this was not yet anywhere near completion. At the Berkeley session, Teller diverted discussion from the fission weapon to the possibility of a fusion weapon—what he called the "Super", an early concept of what was later to be known as a hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

.

Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

, the chairman of the University of Chicago physics department, coordinated the uranium research of Columbia University, Princeton University, the University of Chicago, and the University of California, Berkeley. To remove disagreement and duplication, Compton transferred the scientists to the Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

at Chicago. Teller was left behind at first, because while he and Mici were now American citizens, they still had relatives in enemy countries. In early 1943, the Los Alamos Laboratory was established in Los Alamos, New Mexico to design an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

, with Oppenheimer as its director. Teller moved there in March 1943. Apparently, Teller managed to annoy his neighbors there by playing the piano late in the night.

Teller became part of the Theoretical (T) Division. He was given a secret identity of Ed Tilden. He was irked at being passed over as its head; the job was instead given to Hans Bethe. Oppenheimer had him investigate unusual approaches to building fission weapons, such as autocatalysis, in which the efficiency of the bomb would increase as the nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

progressed, but proved to be impractical. He also investigated using uranium hydride instead of uranium metal, but its efficiency turned out to be "negligible or less". He continued to push his ideas for a fusion weapon even though it had been put on a low priority during the war (as the creation of a fission weapon proved to be difficult enough). On a visit to New York, he asked Maria Goeppert-Mayer to carry out calculations on the Super for him. She confirmed Teller's own results: the Super was not going to work.

A special group was established under Teller in March 1944 to investigate the mathematics of an implosion-type nuclear weapon. It too ran into difficulties. Because of his interest in the Super, Teller did not work as hard on the implosion calculations as Bethe wanted. These too were originally low-priority tasks, but the discovery of spontaneous fission in plutonium by Emilio Segrè's group gave the implosion bomb increased importance. In June 1944, at Bethe's request, Oppenheimer moved Teller out of T Division, and placed him in charge of a special group responsible for the Super, reporting directly to Oppenheimer. He was replaced by Rudolf Peierls from the British Mission, who in turn brought in Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly aft ...

, who was later revealed to be a Soviet spy. Teller's Super group became part of Fermi's F Division when he joined the Los Alamos Laboratory in September 1944. It included Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

, Jane Roberg, Geoffrey Chew

Geoffrey Foucar Chew (; June 5, 1924 – April 12, 2019) was an American theoretical physicist. He is known for his bootstrap theory of strong interactions.

Life

Chew worked as a professor of physics at the UC Berkeley since 1957 and was an e ...

, Harold and Mary Argo, and Maria Goeppert-Mayer.

Teller made valuable contributions to bomb research, especially in the elucidation of the implosion mechanism. He was the first to propose the solid pit design that was eventually successful. This design became known as a " Christy pit", after the physicist Robert F. Christy

Robert Frederick Christy (May 14, 1916 – October 3, 2012) was a Canadian-American theoretical physicist and later astrophysicist who was one of the last surviving people to have worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He briefly ...

who made the pit a reality. Teller was one of the few scientists to actually watch (with eye protection) the Trinity nuclear test in July 1945, rather than follow orders to lie on the ground with backs turned. He later said that the atomic flash "was as if I had pulled open the curtain in a dark room and broad daylight streamed in".

Decision to drop the bombs

In the days before and after the first demonstration of a nuclear weapon, the Trinity test in July 1945, his fellow Hungarian Leo Szilard circulated the Szilard petition, which argued that a demonstration to the Japanese of the new weapon should occur prior to actual use on Japan, and with that hopefully the weapons would never be used on people. In response to Szilard's petition, Teller consulted his friend Robert Oppenheimer. Teller believed that Oppenheimer was a natural leader and could help him with such a formidable political problem. Oppenheimer reassured Teller that the nation's fate should be left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Bolstered by Oppenheimer's influence, he decided to not sign the petition. Teller therefore penned a letter in response to Szilard that read: On reflection on this letter years later when he was writing his memoirs, Teller wrote: Unknown to Teller at the time, four of his colleagues were solicited by the then secret May to June 1945Interim Committee

The Interim Committee was a secret high-level group created in May 1945 by United States Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson at the urging of leaders of the Manhattan Project and with the approval of President Harry S. Truman to advise on m ...

. It is this organization which ultimately decided on how the new weapons should initially be used. The committee's four-member ''Scientific Panel'' was led by Oppenheimer, and concluded immediate military use on Japan was the best option:

Teller later learned of Oppenheimer's solicitation and his role in the Interim Committee's decision to drop the bombs, having secretly endorsed an immediate military use of the new weapons. This was contrary to the impression that Teller had received when he had personally asked Oppenheimer about the Szilard petition: that the nation's fate should be left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Following Teller's discovery of this, his relationship with his advisor began to deteriorate.

In 1990, the historian Barton Bernstein

Barton J. Bernstein (born 1936) is Professor emeritus of History at Stanford University and Co-Chair of the International Relations Program and the International Policy Studies Program. He has published about early Cold War history, as well as abo ...

argued that it is an "unconvincing claim" by Teller that he was a "covert dissenter" to the use of the bomb. In his 2001 ''Memoirs'', Teller claims that he did lobby Oppenheimer, but that Oppenheimer had convinced him that he should take no action and that the scientists should leave military questions in the hands of the military; Teller claims he was not aware that Oppenheimer and other scientists were being consulted as to the actual use of the weapon and implies that Oppenheimer was being hypocritical.

Hydrogen bomb

Despite an offer from Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Oppenheimer as the director of Los Alamos in November 1945, to become the head of the Theoretical (T) Division, Teller left Los Alamos on February 1, 1946, to return to the University of Chicago as a professor and close associate of Fermi and Goeppert-Mayer. Mayer's work on the internal structure of the elements would earn her the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963. On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium and the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed. It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium and the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed. It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during deuterium burning

Deuterium fusion, also called deuterium burning, is a nuclear fusion reaction that occurs in stars and some substellar objects, in which a deuterium nucleus and a proton combine to form a helium-3 nucleus. It occurs as the second stage of the p ...

, would shed doubt on its workability. Addition of expensive tritium to the thermonuclear mixture would likely lower its ignition temperature, but even so, nobody knew at that time how much tritium would be needed, and whether even tritium addition would encourage heat propagation.

At the end of the conference, in spite of opposition by some members such as Robert Serber, Teller submitted an optimistic report in which he said that a hydrogen bomb was feasible, and that further work should be encouraged on its development. Fuchs also participated in this conference, and transmitted this information to Moscow. With John von Neumann, he contributed an idea of using implosion to ignite the Super. The model of Teller's "classical Super" was so uncertain that Oppenheimer would later say that he wished the Russians were building their own hydrogen bomb based on that design, so that it would almost certainly retard their progress on it.

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

.

Teller returned to Los Alamos in 1950 to work on the project. He insisted on involving more theorists, but many of Teller's prominent colleagues, like Fermi and Oppenheimer, were sure that the project of the H-bomb was technically infeasible and politically undesirable. None of the available designs were yet workable. However Soviet scientists who had worked on their own hydrogen bomb have claimed that they developed it independently.

In 1950, calculations by the Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

and his collaborator Cornelius Everett, along with confirmations by Fermi, had shown that not only was Teller's earlier estimate of the quantity of tritium needed for the H-bomb a low one, but that even with higher amounts of tritium, the energy loss in the fusion process would be too great to enable the fusion reaction to propagate. However, in 1951 Teller and Ulam made a breakthrough, and invented a new design, proposed in a classified March 1951 paper, ''On Heterocatalytic Detonations I: Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors'', for a practical megaton-range H-bomb. The exact contribution provided respectively from Ulam and Teller to what became known as the Teller–Ulam design is not definitively known in the public domain, and the exact contributions of each and how the final idea was arrived upon has been a point of dispute in both public and classified discussions since the early 1950s.

In an interview with '' Scientific American'' from 1999, Teller told the reporter:

The issue is controversial. Bethe considered Teller's contribution to the invention of the H-bomb a true innovation as early as 1952, and referred to his work as a "stroke of genius" in 1954. In both cases, however, Bethe emphasized Teller's role as a way of stressing that the development of the H-bomb could not have been hastened by additional support or funding, and Teller greatly disagreed with Bethe's assessment. Other scientists (antagonistic to Teller, such as J. Carson Mark

Jordan Carson Mark (July 6, 1913 – March 2, 1997) was a Canadian-American mathematician best known for his work on developing nuclear weapons for the United States at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Mark joined the Manhattan Project in 1945 ...

) have claimed that Teller would have never gotten any closer without the assistance of Ulam and others. Ulam himself claimed that Teller only produced a "more generalized" version of Ulam's original design.

The breakthrough—the details of which are still classified—was apparently the separation of the fission and fusion components of the weapons, and to use the X-rays produced by the fission bomb to first compress the fusion fuel (by process known as "radiation implosion") before igniting it. Ulam's idea seems to have been to use mechanical shock from the primary to encourage fusion in the secondary, while Teller quickly realized that X-rays from the primary would do the job much more symmetrically. Some members of the laboratory (J. Carson Mark in particular) later expressed the opinion that the idea to use the X-rays would have eventually occurred to anyone working on the physical processes involved, and that the obvious reason why Teller thought of it right away was because he was already working on the "Greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of Transparent ceramics, transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic condit ...

" tests for the spring of 1951, in which the effect of X-rays from a fission bomb on a mixture of deuterium and tritium was going to be investigated.

Whatever the actual components of the so-called Teller–Ulam design and the respective contributions of those who worked on it, after it was proposed it was immediately seen by the scientists working on the project as the answer which had been so long sought. Those who previously had doubted whether a fission-fusion bomb would be feasible at all were converted into believing that it was only a matter of time before both the US and the USSR had developed multi-megaton weapons. Even Oppenheimer, who was originally opposed to the project, called the idea "technically sweet".

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory, which had been created largely through his urging. After the detonation of Ivy Mike, the first thermonuclear weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration, on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds—and instead saw its results on a

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory, which had been created largely through his urging. After the detonation of Ivy Mike, the first thermonuclear weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration, on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds—and instead saw its results on a seismograph

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The output ...

in the basement of a hall in Berkeley.

There was an opinion that by analyzing the fallout from this test, the Soviets (led in their H-bomb work by Andrei Sakharov) could have deciphered the new American design. However, this was later denied by the Soviet bomb researchers. Because of official secrecy, little information about the bomb's development was released by the government, and press reports often attributed the entire weapon's design and development to Teller and his new Livermore Laboratory (when it was actually developed by Los Alamos).

Many of Teller's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a part in, and in response, with encouragement from Enrico Fermi, Teller authored an article titled "The Work of Many People", which appeared in '' Science'' magazine in February 1955, emphasizing that he was not alone in the weapon's development. He would later write in his memoirs that he had told a "white lie" in the 1955 article in order to "soothe ruffled feelings", and claimed full credit for the invention.

Teller was known for getting engrossed in projects which were theoretically interesting but practically unfeasible (the classic "Super" was one such project.) About his work on the hydrogen bomb, Bethe said:

During the Manhattan Project, Teller advocated the development of a bomb using uranium hydride, which many of his fellow theorists said would be unlikely to work. At Livermore, Teller continued work on the hydride bomb, and the result was a dud. Ulam once wrote to a colleague about an idea he had shared with Teller: "Edward is full of enthusiasm about these possibilities; this is perhaps an indication they will not work." Fermi once said that Teller was the only monomaniac he knew who had several mania

Mania, also known as manic syndrome, is a mental and behavioral disorder defined as a state of abnormally elevated arousal, affect, and energy level, or "a state of heightened overall activation with enhanced affective expression together wit ...

s.

Carey Sublette of Nuclear Weapon Archive argues that Ulam came up with the radiation implosion compression design of thermonuclear weapons, but that on the other hand Teller has gotten little credit for being the first to propose fusion boosting

A boosted fission weapon usually refers to a type of nuclear bomb that uses a small amount of fusion fuel to increase the rate, and thus yield, of a fission reaction. The neutrons released by the fusion reactions add to the neutrons released d ...

in 1945, which is essential for miniaturization and reliability and is used in all of today's nuclear weapons.

Oppenheimer controversy

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney Roger Robb whether he was planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States", Teller replied that:

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney Roger Robb whether he was planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States", Teller replied that:I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and a very complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof to the opposite.He was immediately asked whether he believed that Oppenheimer was a "security risk", to which he testified: Teller also testified that Oppenheimer's opinion about the thermonuclear program seemed to be based more on the scientific feasibility of the weapon than anything else. He additionally testified that Oppenheimer's direction of Los Alamos was "a very outstanding achievement" both as a scientist and an administrator, lauding his "very quick mind" and that he made "just a most wonderful and excellent director". After this, however, he detailed ways in which he felt that Oppenheimer had hindered his efforts towards an active thermonuclear development program, and at length criticized Oppenheimer's decisions not to invest more work onto the question at different points in his career, saying: "If it is a question of wisdom and judgment, as demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one would be wiser not to grant clearance." By recasting a difference of judgment over the merits of the early work on the hydrogen bomb project into a matter of a security risk, Teller effectively damned Oppenheimer in a field where security was necessarily of paramount concern. Teller's testimony thereby rendered Oppenheimer vulnerable to charges by a Congressional aide that he was a Soviet spy, which resulted in the destruction of Oppenheimer's career. Oppenheimer's security clearance was revoked after the hearings. Most of Teller's former colleagues disapproved of his testimony and he was ostracized by much of the scientific community. After the fact, Teller consistently denied that he was intending to damn Oppenheimer, and even claimed that he was attempting to exonerate him. However, documentary evidence has suggested that this was likely not the case. Six days before the testimony, Teller met with an AEC liaison officer and suggested "deepening the charges" in his testimony. Teller always insisted that his testimony had not significantly harmed Oppenheimer. In 2002, Teller contended that Oppenheimer was "not destroyed" by the security hearing but "no longer asked to assist in policy matters". He claimed his words were an overreaction, because he had only just learned of Oppenheimer's failure to immediately report an approach by Haakon Chevalier, who had approached Oppenheimer to help the Russians. Teller said that, in hindsight, he would have responded differently. Historian Richard Rhodes said that in his opinion it was already a foregone conclusion that Oppenheimer would have his security clearance revoked by then AEC chairman Lewis Strauss, regardless of Teller's testimony. However, as Teller's testimony was the most damning, he was singled out and blamed for the hearing's ruling, losing friends due to it, such as

Robert Christy

Robert Frederick Christy (May 14, 1916 – October 3, 2012) was a Canadian-American theoretical physicist and later astrophysicist who was one of the last surviving people to have worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He briefly ...

, who refused to shake his hand in one infamous incident. This was emblematic of his later treatment which resulted in him being forced into the role of an outcast of the physics community, thus leaving him little choice but to align himself with industrialists.

US government work and political advocacy

After the Oppenheimer controversy, Teller became ostracized by much of the scientific community, but was still quite welcome in the government and military science circles. Along with his traditional advocacy for nuclear energy development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing program, he had helped to develop nuclear reactor safety standards as the chair of the Reactor Safeguard Committee of the AEC in the late 1940s, and in the late 1950s headed an effort at General Atomics which designed research reactors in which a nuclear meltdown would be impossible. The TRIGA (''Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomic'') has been built and used in hundreds of hospitals and universities worldwide formedical isotope

A medical isotope is an isotope used in medicine.

The first uses of isotopes in medicine were in radiopharmaceuticals, and this is still the most common use. However more recently, separated stable isotopes have also come into use.

Examples of ...

production and research.

Teller promoted increased defense spending to counter the perceived Soviet missile threat. He was a signatory to the 1958 report by the military sub-panel of the Rockefeller Brothers funded Special Studies Project The Special Studies Project was a study funded by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and conceived by its then president, Nelson Rockefeller, to 'define the major problems and opportunities facing the U.S. and clarify national purposes and objectives, a ...

, which called for a $3 billion annual increase in America's military budget.

In 1956 he attended the Project Nobska

Project Nobska was a 1956 summer study on anti-submarine warfare (ASW) for the United States Navy ordered by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke. It is also referred to as the Nobska Study, named for its location on Nobska Point near ...

anti-submarine warfare conference, where discussion ranged from oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamic ...

to nuclear weapons. In the course of discussing a small nuclear warhead for the Mark 45 torpedo

The Mark 45 anti-submarine torpedo, a.k.a. ASTOR, was a submarine-launched wire-guided nuclear torpedo designed by the United States Navy for use against high-speed, deep-diving, enemy submarines. This was one of several weapons recommended for ...

, he started a discussion on the possibility of developing a physically small one-megaton nuclear warhead for the Polaris missile

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy was involved in the Jupiter missile ...

. His counterpart in the discussion, J. Carson Mark

Jordan Carson Mark (July 6, 1913 – March 2, 1997) was a Canadian-American mathematician best known for his work on developing nuclear weapons for the United States at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Mark joined the Manhattan Project in 1945 ...

from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, at first insisted it could not be done. However, Dr. Mark eventually stated that a half-megaton warhead of small enough size could be developed. This yield, roughly thirty times that of the Hiroshima bomb

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

, was enough for Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

Admiral Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenne ...

, who was present in person, and Navy strategic missile development shifted from Jupiter to Polaris by the end of the year.

He was Director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

, which he helped to found with Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation f ...

, from 1958 to 1960, and after that he continued as an Associate Director. He chaired the committee that founded the Space Sciences Laboratory at Berkeley. He also served concurrently as a Professor of Physics at the University of California, Berkeley. He was a tireless advocate of a strong nuclear program and argued for continued testing and development—in fact, he stepped down from the directorship of Livermore so that he could better lobby

Lobby may refer to:

* Lobby (room), an entranceway or foyer in a building

* Lobbying, the action or the group used to influence a viewpoint to politicians

:* Lobbying in the United States, specific to the United States

* Lobby (food), a thick stew ...

against the proposed test ban. He testified against the test ban both before Congress as well as on television.

Teller established the Department of Applied Science at the University of California, Davis and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

in 1963, which holds the Edward Teller endowed professorship in his honor. In 1975 he retired from both the lab and Berkeley, and was named Director Emeritus of the Livermore Laboratory and appointed Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution. After the end of communism in Hungary in 1989, he made several visits to his country of origin, and paid careful attention to the political changes there.

Global climate change

Teller was one of the first prominent people to raise the danger of climate change, driven by the burning offossil fuels

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels ...

. At an address to the membership of the American Chemical Society in December 1957, Teller warned that the large amount of carbon-based fuel that had been burnt since the mid-19th century was increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which would "act in the same way as a greenhouse and will raise the temperature at the surface", and that he had calculated that if the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased by 10% "an appreciable part of the polar ice might melt".

In 1959, at a symposium organised by the American Petroleum Institute and the Columbia Graduate School of Business for the centennial of the American oil industry, Edward Teller warned that:

Non-military uses of nuclear explosions

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare. One of the most controversial projects he proposed was a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through Point Hope, Alaska. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project Chariot. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site, and having withdrawn the land from the public domain, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders that the plan was financially viable.

Other scientists criticized the project as being potentially unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living near the designated area, who were not officially told of the plan until March 1960. Additionally, it turned out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility of the project and the concerns over radiation-related health issues, the project was abandoned in 1962.

A related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands in northern Alberta with nuclear explosions, titled Project Oilsands. The plan actually received the endorsement of the Alberta government, but was rejected by the Government of Canada under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who was opposed to having any nuclear weapons in Canada. After Diefenbaker was out of office, Canada went on to have nuclear weapons, from a US nuclear sharing agreement, from 1963 to 1984.

Teller also proposed the use of nuclear bombs to prevent damage from powerful hurricanes. He argued that when conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are right for the formation of hurricanes, the heat generated by well-placed nuclear explosions could trigger several small hurricanes, rather than waiting for nature to build one large one.

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare. One of the most controversial projects he proposed was a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through Point Hope, Alaska. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project Chariot. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site, and having withdrawn the land from the public domain, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders that the plan was financially viable.

Other scientists criticized the project as being potentially unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living near the designated area, who were not officially told of the plan until March 1960. Additionally, it turned out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility of the project and the concerns over radiation-related health issues, the project was abandoned in 1962.

A related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands in northern Alberta with nuclear explosions, titled Project Oilsands. The plan actually received the endorsement of the Alberta government, but was rejected by the Government of Canada under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who was opposed to having any nuclear weapons in Canada. After Diefenbaker was out of office, Canada went on to have nuclear weapons, from a US nuclear sharing agreement, from 1963 to 1984.

Teller also proposed the use of nuclear bombs to prevent damage from powerful hurricanes. He argued that when conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are right for the formation of hurricanes, the heat generated by well-placed nuclear explosions could trigger several small hurricanes, rather than waiting for nature to build one large one.

Nuclear technology and Israel

For some twenty years, Teller advised Israel on nuclear matters in general, and on the building of a hydrogen bomb in particular. In 1952, Teller and Oppenheimer had a long meeting with David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv, telling him that the best way to accumulate plutonium was to burn natural uranium in a nuclear reactor. Starting in 1964, a connection between Teller and Israel was made by the physicist Yuval Ne'eman, who had similar political views. Between 1964 and 1967, Teller visited Israel six times, lecturing at Tel Aviv University, and advising the chiefs of Israel's scientific-security circle as well as prime ministers and cabinet members. In 1967 when the Israeli nuclear program was nearing completion, Teller informed Neeman that he was going to tell theCIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

that Israel had built nuclear weapons, and explain that it was justified by the background of the Six-Day War. After Neeman cleared it with Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, Teller briefed the head of the CIA's Office of Science and Technology, Carl Duckett. It took a year for Teller to convince the CIA that Israel had obtained nuclear capability

Eight sovereign states have publicly announced successful detonation of nuclear weapons. Five are considered to be nuclear-weapon states (NWS) under the terms of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). In order of acquisit ...

; the information then went through CIA Director Richard Helms to the president at that time, Lyndon B. Johnson. Teller also persuaded them to end the American attempts to inspect the Negev Nuclear Research Center

The Shimon Peres Negev Nuclear Research Center ( he, קריה למחקר גרעיני – נגב ע"ש שמעון פרס, formerly the ''Negev Nuclear Research Center'', unofficially sometimes referred to as the ''Dimona reactor'') is an Israe ...

in Dimona. In 1976 Duckett testified in Congress before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is an independent agency of the United States government tasked with protecting public health and safety related to nuclear energy. Established by the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, the NRC began operat ...

, that after receiving information from an "American scientist", he drafted a National Intelligence Estimate

National Intelligence Estimates (NIEs) are United States federal government documents that are the authoritative assessment of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) on intelligence related to a particular national security issue. NIEs are pr ...

on Israel's nuclear capability.

In the 1980s, Teller again visited Israel to advise the Israeli government

The Cabinet of Israel (officially: he, ממשלת ישראל ''Memshelet Yisrael'') exercises executive authority in the State of Israel. It consists of ministers who are chosen and led by the prime minister. The composition of the governmen ...

on building a nuclear reactor. Three decades later, Teller confirmed that it was during his visits that he concluded that Israel was in possession of nuclear weapons. After conveying the matter to the U.S. government, Teller reportedly said: "They srael have it, and they were clever enough to trust their research and not to test, they know that to test would get them into trouble."

Three Mile Island

Teller suffered a heart attack in 1979, and blamed it onJane Fonda

Jane Seymour Fonda (born December 21, 1937) is an American actress, activist, and former fashion model. Recognized as a film icon, Fonda is the recipient of various accolades including two Academy Awards, two British Academy Film Awards, sev ...

, who had starred in ''The China Syndrome

''The China Syndrome'' is a 1979 American disaster thriller film directed by James Bridges and written by Bridges, Mike Gray, and T. S. Cook. The film stars Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon, Michael Douglas (who also produced), Scott Brady, James Ham ...

'', which depicted a fictional reactor accident and was released less than two weeks before the Three Mile Island accident. She spoke out against nuclear power while promoting the film. After the accident, Teller acted quickly to lobby in defence of nuclear energy, testifying to its safety and reliability, and soon after one flurry of activity suffered the attack. He signed a two-page-spread ad in the July 31, 1979, issue of '' The Washington Post'' with the headline "I was the only victim of Three-Mile Island". It opened with:

Strategic Defense Initiative

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derisively nicknamed the "''Star Wars'' program", was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic strategic nuclear weapons (intercontinental ballistic ...

(SDI), derided by critics as "Star Wars", the concept of using ground and satellite-based lasers, particle beams and missiles to destroy incoming Soviet ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

s. Teller lobbied with government agencies—and got the approval of President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

—for a plan to develop a system using elaborate satellites which used atomic weapons to fire X-ray lasers at incoming missiles—as part of a broader scientific research program into defenses against nuclear weapons.

Scandal erupted when Teller (and his associate Lowell Wood

Lowell Lincoln Wood Jr. (born 1941) is an American astrophysicist who has been involved with the Strategic Defense Initiative and with geoengineering studies. He has been affiliated with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the Hoover In ...

) were accused of deliberately overselling the program and perhaps encouraging the dismissal of a laboratory director (Roy Woodruff) who had attempted to correct the error. His claims led to a joke which circulated in the scientific community, that a new unit of unfounded optimism was designated as the teller; one teller was so large that most events had to be measured in nanotellers or picotellers.

Many prominent scientists argued that the system was futile. Hans Bethe, along with IBM physicist Richard Garwin and Cornell University colleague Kurt Gottfried, wrote an article in '' Scientific American'' which analyzed the system and concluded that any putative enemy could disable such a system by the use of suitable decoys that would cost a very small fraction of the SDI program.

In 1987 Teller published a book entitled ''Better a Shield than a Sword'', which supported civil defense

Civil defense ( en, region=gb, civil defence) or civil protection is an effort to protect the citizens of a state (generally non-combatants) from man-made and natural disasters. It uses the principles of emergency operations: prevention, miti ...

and active protection systems

An active protection system is a system designed to actively prevent certain anti-tank weapons from destroying a vehicle.

Countermeasures that either conceal the vehicle from, or disrupt the guidance of an incoming guided missile threat are design ...

. His views on the role of lasers in SDI were published, and are available, in two 1986–87 laser conference proceedings.

Asteroid impact avoidance

Following the 1994 Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet impacts with Jupiter, Teller proposed to a collective of U.S. and Russian ex-Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

weapons designers in a 1995 planetary defense workshop at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

, that they collaborate to design a 1 gigaton nuclear explosive device, which would be equivalent to the kinetic energy of a 1 km diameter asteroid.Planetary defense workshop LLNL 1995/ref> In order to safeguard the earth, the theoretical 1 Gt device would weigh about 25–30 tons—light enough to be lifted on the Russian

Energia

Energia or Energiya may refer to:

* Energia (corporation), or S. P. Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia, a Russian design bureau and manufacturer

** Energia (rocket), a Soviet rocket designed by the company

*Energia (company), a company th ...

rocket—and could be used to instantaneously vaporize a 1 km asteroid, or divert the paths of extinction event class asteroids (greater than 10 km in diameter) with a few months' notice; with 1-year notice, at an interception location no closer than Jupiter, it would also be capable of dealing with the even rarer short period comets

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena a ...

which can come out of the Kuiper belt

The Kuiper belt () is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units (AU) to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. It is similar to the asteroid belt, but is far larger—20 times ...

and transit past Earth orbit within 2 years. For comets of this class, with a maximum estimated 100 km diameter, Charon