Dilophosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Dilophosaurus'' ( ) is a

In the summer of 1942, the paleontologist Charles L. Camp led a field party from the

In the summer of 1942, the paleontologist Charles L. Camp led a field party from the

In 1984, Welles suggested that the 1964 specimen (UCMP 77270) did not belong to ''Dilophosaurus'', but to a new genus, based on differences in the skull, vertebrae, and femora. He maintained that both genera bore crests, but that the exact shape of these was unknown in ''Dilophosaurus''. Welles died in 1997, before he could name this supposed new dinosaur, and the idea that the two were separate genera has generally been ignored or forgotten since. In 1999, amateur paleontologist Stephan Pickering privately published the new name ''Dilophosaurus'' "breedorum" based on the 1964 specimen, named in honor of Breed, who had assisted in collecting it. This name is considered a''

In 1984, Welles suggested that the 1964 specimen (UCMP 77270) did not belong to ''Dilophosaurus'', but to a new genus, based on differences in the skull, vertebrae, and femora. He maintained that both genera bore crests, but that the exact shape of these was unknown in ''Dilophosaurus''. Welles died in 1997, before he could name this supposed new dinosaur, and the idea that the two were separate genera has generally been ignored or forgotten since. In 1999, amateur paleontologist Stephan Pickering privately published the new name ''Dilophosaurus'' "breedorum" based on the 1964 specimen, named in honor of Breed, who had assisted in collecting it. This name is considered a''

''Dilophosaurus'' was one of the earliest large predatory

''Dilophosaurus'' was one of the earliest large predatory

''Dilophosaurus'' bore a pair of high, thin, and arched (or plate-shaped) crests longitudinally on the skull roof. The crests (termed the nasolacrimal crests) began as low ridges on the premaxillae and were mainly formed by the upwards expanded and . These bones were coossified together (fusion during bone tissue formation), so the sutures between them cannot be determined. The lacrimal bone expanded into a thick, rugose boss, forming an arc at the upper front border of the

''Dilophosaurus'' bore a pair of high, thin, and arched (or plate-shaped) crests longitudinally on the skull roof. The crests (termed the nasolacrimal crests) began as low ridges on the premaxillae and were mainly formed by the upwards expanded and . These bones were coossified together (fusion during bone tissue formation), so the sutures between them cannot be determined. The lacrimal bone expanded into a thick, rugose boss, forming an arc at the upper front border of the  The orbit was oval, and narrow towards the bottom. The

The orbit was oval, and narrow towards the bottom. The

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s that lived in what is now North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

during the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-J ...

, about 193 million years ago. Three skeletons were discovered in northern Arizona

Northern Arizona is an unofficial, colloquially-defined region of the U.S. state of Arizona. Generally consisting of Apache, Coconino, Mohave, Navajo, and Gila counties, the region is geographically dominated by the Colorado Plateau, the sout ...

in 1940, and the two best preserved were collected in 1942. The most complete specimen became the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

of a new species in the genus ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years a ...

'', named ''M. wetherilli'' by Samuel P. Welles in 1954. Welles found a larger skeleton belonging to the same species in 1964. Realizing it bore crests on its skull, he assigned the species to the new genus ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1970, as ''Dilophosaurus wetherilli''. The genus name means "two-crested lizard", and the species name honors John Wetherill, a Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

councilor. Further specimens have since been found, including an infant. Footprints have also been attributed to the animal, including resting traces. Another species, ''Dilophosaurus sinensis'' from China, was named in 1993, but was later found to belong to the genus ''Sinosaurus

''Sinosaurus'' (meaning "Chinese lizard") is an extinct genus of theropod dinosaur which lived during the Early Jurassic Period. It was a bipedal carnivore approximately in length and in body mass. Fossils of the animal were found at the Lufen ...

''.

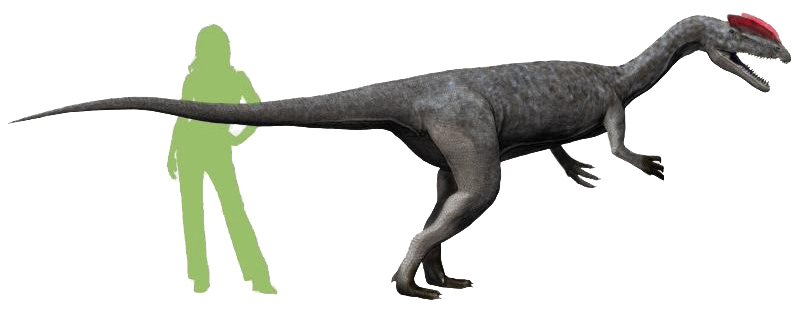

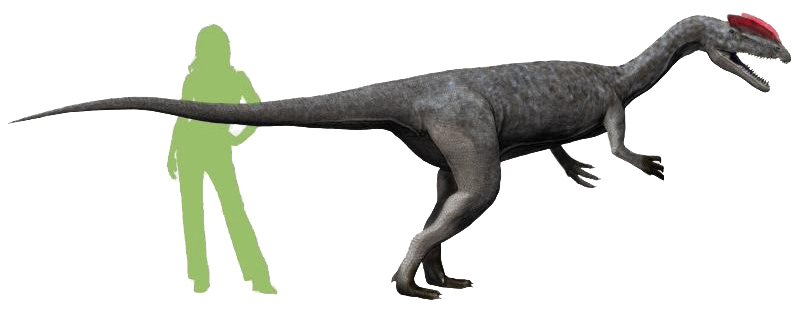

At about in length, with a weight of about , ''Dilophosaurus'' was one of the earliest large predatory dinosaurs and the largest known land-animal in North America at the time. It was slender and lightly built, and the skull was proportionally large, but delicate. The snout was narrow, and the upper jaw had a gap or kink below the nostril. It had a pair of longitudinal, arched crests on its skull; their complete shape is unknown, but they were probably enlarged by keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

. The mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

was slender and delicate at the front, but deep at the back. The teeth were long, curved, thin, and compressed sideways. Those in the lower jaw were much smaller than those of the upper jaw. Most of the teeth had serration

Serration is a saw-like appearance or a row of sharp or tooth-like projections. A serrated cutting edge has many small points of contact with the material being cut. By having less contact area than a smooth blade or other edge, the applied pr ...

s at their front and back edges. The neck was long, and its vertebrae were hollow, and very light. The arms were powerful, with a long and slender upper arm bone. The hands had four fingers; the first was short but strong and bore a large claw, the two following fingers were longer and slenderer with smaller claws; the fourth was vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

. The thigh bone was massive, the feet were stout, and the toes bore large claws.

''Dilophosaurus'' has been considered a member of the family Dilophosauridae along with ''Dracovenator

''Dracovenator'' () is a genus of neotheropod dinosaur that lived approximately 201 to 199 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now South Africa. ''Dracovenator'' was a medium-sized, moderately-built, ground ...

'', a group placed between the Coelophysidae

Coelophysidae is a family of primitive carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. Most species were relatively small in size. The family flourished in the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods, and has been found on numerous continents. Many members of C ...

and later theropods, but some researchers have not found support for this grouping. ''Dilophosaurus'' would have been active and bipedal, and may have hunted large animals; it could also have fed on smaller animals and fish. Due to the limited range of movement and shortness of the forelimbs, the mouth may instead have made first contact with prey. The function of the crests is unknown; they were too weak for battle, but may have been used in visual display

Display behaviour is a set of ritualized behaviours that enable an animal to communicate to other animals (typically of the same species) about specific stimuli. These ritualized behaviours can be visual however many animals depend on a mixture ...

, such as species recognition

Intra-species recognition is the recognition by a member of a species of a conspecific (another member of the same species). In many species, such recognition is necessary for procreation.

Different species may employ different methods, but all ...

and sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of t ...

. It may have grown rapidly, attaining a growth rate of per year early in life. The holotype specimen had multiple paleopathologies

Paleopathology, also spelled palaeopathology, is the study of ancient diseases and injuries in organisms through the examination of fossils, mummified tissue, skeletal remains, and analysis of coprolites. Specific sources in the study of ancie ...

, including healed injuries and signs of a developmental anomaly. ''Dilophosaurus'' is known from the Kayenta Formation

The Kayenta Formation is a geological formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the Colorado Plateau province of the United States, including northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. Traditionally has been suggested ...

, and lived alongside dinosaurs such as ''Scutellosaurus

''Scutellosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of thyreophoran ornithischian dinosaur that lived approximately 196 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Arizona, USA. It is classified in Thyreophora, the armoured di ...

'' and ''Sarahsaurus

''Sarahsaurus'' is a genus of basal sauropodomorph dinosaur which lived during the Early Jurassic period in what is now northeastern Arizona, United States.

Discovery and naming

All specimens of ''Sarahsaurus'' were collected from the Lower Ju ...

''. ''Dilophosaurus'' was featured in the novel ''Jurassic Park

''Jurassic Park'', later also referred to as ''Jurassic World'', is an American science fiction media franchise created by Michael Crichton and centered on a disastrous attempt to create a theme park of cloned dinosaurs. It began in 1990 when ...

'' and its movie adaptation

A film adaptation is the transfer of a work or story, in whole or in part, to a feature film. Although often considered a type of derivative work, film adaptation has been conceptualized recently by academic scholars such as Robert Stam as a dia ...

, wherein it was given the fictional abilities to spit venom and expand a neck frill

A neck frill is the relatively extensive margin seen on the back of the heads of reptiles with either a bony support such as those present on the skulls of dinosaurs of the suborder Marginocephalia or a cartilaginous one as in the frill-necked ...

, as well as being smaller than the real animal. It was designated as the state dinosaur

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* '' State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our ...

of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

based on tracks found there.

History of discovery

In the summer of 1942, the paleontologist Charles L. Camp led a field party from the

In the summer of 1942, the paleontologist Charles L. Camp led a field party from the University of California Museum of Paleontology

The University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) is a paleontology museum located on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley.

The museum is within the Valley Life Sciences Building (VLSB), designed by George W. Kelham and ...

(UCMP) in search of fossil vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

in Navajo County

Navajo County is in the northern part of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, its population was 106,717. The county seat is Holbrook.

Navajo County comprises the Show Low, Arizona Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Navajo County c ...

in northern Arizona

Northern Arizona is an unofficial, colloquially-defined region of the U.S. state of Arizona. Generally consisting of Apache, Coconino, Mohave, Navajo, and Gila counties, the region is geographically dominated by the Colorado Plateau, the sout ...

. Word of this was spread among the Native Americans there, and the Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

Jesse Williams brought three members of the expedition to some fossil bones he had discovered in 1940. The area was part of the Kayenta Formation

The Kayenta Formation is a geological formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the Colorado Plateau province of the United States, including northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. Traditionally has been suggested ...

, about north of Cameron near Tuba City

Tuba City ( nv, ) is an unincorporated town in Coconino County, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation, United States. It is the second-largest community in Coconino County. The population of the census-designated place (CDP) was 8,611 at the 2010 cen ...

in the Navajo Indian Reservation. Three dinosaur skeletons were found in purplish shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especial ...

, arranged in a triangle, about long at one side. The first was nearly complete, lacking only the front of the skull, parts of the pelvis, and some vertebrae. The second was very eroded, included the front of the skull, lower jaws, some vertebrae, limb bones, and an articulated hand. The third was so eroded that it consisted only of vertebral fragments. The first good skeleton was encased in a block of plaster after 10 days of work and loaded onto a truck, the second skeleton was easily collected, as it was almost entirely weathered out of the ground, but the third skeleton was almost gone.

The nearly complete first specimen was cleaned and mounted at the UCMP under supervision of the paleontologist Wann Langston

Wann Langston Jr. (1921 – April 7, 2013) was an American paleontologist and professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

Langston worked on a number of different reptiles and amphibians in his long career, beginning with the 1950 description ...

, a process that took three men two years. The skeleton was wall-mounted in bas relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

, with the tail curved upwards, the neck straightened, and the left leg moved up for visibility, but the rest of the skeleton was kept in its burial position. As the skull was crushed, it was reconstructed based on the back of the skull of the first specimen and the front of the second. The pelvis was reconstructed after that of ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alluding to ...

'', and the feet were also reconstructed. At the time, it was one of the best-preserved skeletons of a theropod dinosaur, though incomplete. In 1954, the paleontologist Samuel P. Welles, who was part of the group who excavated the skeletons, preliminarily described and named this dinosaur as a new species in the existing genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years a ...

'', ''M. wetherilli''. The nearly complete specimen (catalogued as UCMP 37302) was made the holotype of the species, and the second specimen (UCMP 37303) was made the paratype

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype nor a syntype). Of ...

. The specific name honored John Wetherill, a Navajo councilor whom Welles described as an "explorer, friend of scientists, and trusted trader". Wetherill's nephew, Milton, had first informed the expedition of the fossils. Welles placed the new species in ''Megalosaurus'' due to the similar limb proportions of it and ''M. bucklandii'', and because he did not find great differences between them. At the time, ''Megalosaurus'' was used as a "wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the sole purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined ...

", wherein many species of theropods were placed, regardless of their age or locality.

Welles returned to Tuba City in 1964 to determine the age of the Kayenta Formation (it had been suggested to be Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch ...

in age, whereas Welles thought it was Early to Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second epoch of the Jurassic Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relatively rare, but geological formations co ...

), and discovered another skeleton about south of where the 1942 specimens had been found. The nearly complete specimen (catalogued as UCMP 77270) was collected with the help of William J. Breed

William J. "Bill" Breed (August 3, 1928 - January 22, 2013) was an American geologist, paleontologist, naturalist and author in Northern Arizona. He was a renowned expert on the geology of the Grand Canyon.

Personal life

William J. Breed was ...

of the Museum of Northern Arizona

The Museum of Northern Arizona is a museum in Flagstaff, Arizona, United States, that was established as a repository for Indigenous material and natural history specimens from the Colorado Plateau.

The museum was founded in 1928 by zoologist ...

and others. During preparation of this specimen, it became clear that it was a larger individual of ''M. wetherilli'', and that it would have had two crests on the top of its skull. Being a thin plate of bone, one crest was originally thought to be part of the missing left side of the skull, which had been pulled out of its position by a scavenger

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding b ...

. When it became apparent that it was a crest, it was also realized that a corresponding crest would have been on the left side, since the right crest was right of the midline, and was concave along its middle length. This discovery led to re-examination of the holotype specimen, which was found to have bases of two thin, upwards-extended bones, which were crushed together. These also represented crests, but they had formerly been assumed to be part of a misplaced cheek bone. The two 1942 specimens were also found to be juveniles, while the 1964 specimen was an adult, about one-third larger than the others. Welles later recalled that he thought the crests were as unexpected as finding "wings on a worm".

New genus and subsequent discoveries

Welles and an assistant subsequently corrected the wall mount of the holotype specimen based on the new skeleton, by restoring the crests, redoing the pelvis, making the neck ribs longer, and placing them closer together. After studying the skeletons of North American and European theropods, Welles realized that the dinosaur did not belong to ''Megalosaurus'', and needed a new genus name. At that time, no other theropods with large longitudinal crests on their heads were known, and the dinosaur had therefore gained the interest of paleontologists. A mold of the holotype specimen was made, and fiberglass casts of it were distributed to various exhibits; to make labeling these casts easier, Welles decided to name the new genus in a brief note, rather than wait until the publication of a detailed description. In 1970, Welles coined the new genus name ''Dilophosaurus'', from the Greek words ''di'' (''δι'') meaning "two", ''lophos'' (''λόφος'') meaning "crest", and ''sauros'' () meaning "lizard": "two-crested lizard". Welles published a detailedosteological

Osteology () is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, func ...

description of ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1984, but did not include the 1964 specimen, since he thought it belonged to a different genus. ''Dilophosaurus'' was the first well-known theropod from the Early Jurassic, and remains one of the best-preserved examples of that age.

In 2001, the paleontologist Robert J. Gay identified the remains of at least three new ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens (this number is based on the presence of three pubic bone fragments and two differentially sized femora) in the collections of the Museum of Northern Arizona. The specimens were found in 1978 in the Rock Head Quadrangle, away from where the original specimens were found, and had been labeled as a "large theropod". Though most of the material is damaged, it is significant in including elements not preserved in the earlier specimens, including part of the pelvis and several ribs. Some elements in the collection belonged to an infant specimen (MNA P1.3181), the youngest known example of this genus, and one of the earliest known infant theropods from North America, only preceded by some ''Coelophysis

''Coelophysis'' ( traditionally; or , as heard more commonly in recent decades) is an extinct genus of coelophysid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 228 to 201.3 million years ago during the latter part of the Triassic Period from t ...

'' specimens. The juvenile specimen includes a partial humerus, a partial fibula, and a tooth fragment. In 2005, paleontologist Ronald S. Tykoski assigned a specimen (TMM 43646-140) from Gold Spring, Arizona, to ''Dilophosaurus'', but in 2012, paleontologist Matthew T. Carrano and colleagues found it to differ in some details.

In 2020, the paleontologists Adam D. Marsh and Timothy B. Rowe comprehensively redescribed ''Dilophosaurus'' based on the by then known specimens, including specimen UCMP 77270 which had remained undescribed since 1964. They also removed some previously assigned specimens, finding them too fragmentary to identify, and relocated the type quarry with the help of a relative of Jesse Williams. In an interview, Marsh called ''Dilophosaurus'' the "best worst-known dinosaur", since the animal was poorly understood despite having been discovered 80 years earlier. A major problem was that previous studies of the specimens did not make clear which parts were original fossils and which were reconstructed in plaster, yet subsequent researchers only had Welles' 1984 monograph to rely on for subsequent studies, muddling understanding of the dinosaur's anatomy. Marsh spent seven years studying the specimens to clarify the issues surrounding the dinosaur, including two specimens found two decades earlier by Rowe, his Ph.D. advisor.

Formerly assigned species

nomen nudum

In taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published with an adequate descr ...

'', an invalidly published name, and Gay pointed out in 2005 that no significant differences exist between ''D''. "breedorum" and other ''D. wetherilli'' specimens. In 2012, Carrano and colleagues found differences between the 1964 specimen and the holotype specimen, but attributed them to variation between individuals rather than species. Paleontologists Christophe Hendrickx and Octávio Mateus suggested in 2014 that the known specimens might represent two species of ''Dilophosaurus'' based on different skull features and stratigraphic separation, pending thorough description of assigned specimens. Marsh and Rowe concluded in 2020 that there was only one taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

among known ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens, and that differences between them were due to their different degree of maturity and preservation. They did not find considerable stratigraphic separation between the specimens either.

A nearly complete theropod skeleton (KMV 8701) was discovered in the Lufeng Formation

The Lufeng Formation (formerly Lower Lufeng Series) is a Lower Jurassic sedimentary rock formation found in Yunnan, China. It has two units: the lower Dull Purplish Beds/Shawan Member are of Hettangian age, and Dark Red Beds/Zhangjia'ao Member ar ...

, in Yunnan Province

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the C ...

, China, in 1987. It is similar to ''Dilophosaurus'', with a pair of crests and a gap separating the premaxilla from the maxilla, but differs in some details. The paleontologist Shaojin Hu named it as a new species of ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1993, ''D. sinensis'' (from Greek ''Sinai'', referring to China). In 1998, the paleontologist Matthew C. Lamanna and colleagues found ''D. sinensis'' to be identical to '' Sinosaurus triassicus'', a theropod from the same formation, named in 1940. This conclusion was confirmed by paleontologist Lida Xing and colleagues in 2013, and though paleontologist Guo-Fu Wang and colleagues agreed the species belonged in ''Sinosaurus'' in 2017, they suggested it may be a separate species, ''S. sinensis''.

Description

dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

, a medium-sized theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

, though small compared to some of the later theropods. It was also the largest known land-animal of North America during the Early Jurassic. Slender and lightly built, its size was comparable to that of a brown bear

The brown bear (''Ursus arctos'') is a large bear species found across Eurasia and North America. In North America, the populations of brown bears are called grizzly bears, while the subspecies that inhabits the Kodiak Islands of Alaska is kno ...

. The largest known specimen weighed about , measured about in length, and its skull was long. The smaller holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

specimen weighed about , was long, with a hip height of about , and its skull was long. A resting trace of a theropod similar to ''Dilophosaurus'' and '' Liliensternus'' has been interpreted by some researchers as showing impressions of feathers

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premier e ...

around the belly and feet, similar to down. Other researchers instead interpret these impressions as sedimentological

Sedimentology encompasses the study of modern sediments such as sand, silt, and clay, and the processes that result in their formation (erosion and weathering), transport, deposition and diagenesis. Sedimentologists apply their understanding of mo ...

artifacts created as the dinosaur moved, though this interpretation does not rule out that the track-maker could have borne feathers.

Skull

The skull of ''Dilophosaurus'' was large in proportion to the overall skeleton, yet delicate. The snout was narrow in front view, becoming narrower towards the rounded top. Thepremaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

(front bone of the upper jaw) was long and low when seen from the side, bulbous at the front, and its outer surface became less convex from snout to naris (bony nostril). The nostrils were placed further back than in most other theropods. The premaxillae were in close articulation with each other, and while the premaxilla only connected to the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

(the following bone of the upper jaw) at the middle of the palate, with no connection at the side, they formed a strong joint through the robust, interlocking articulation between the hindwards and forwards directed processes of these bones. Hindwards and below, the premaxilla formed a wall for a gap between itself and the maxilla called the subnarial gap (also termed a "kink"). Such a gap is also present in coelophysoids

Coelophysoidea were common dinosaurs of the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. They were widespread geographically, probably living on all continents. Coelophysoids were all slender, carnivorous forms with a superficial similarity to the ...

, as well as other dinosaurs. The subnarial gap resulted in a diastema

A diastema (plural diastemata, from Greek διάστημα, space) is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition ...

, a gap in the tooth row (which has also been called a "notch"). Within the subnarial gap was a deep excavation behind the toothrow of the premaxilla, called the subnarial pit, which was walled by a downwards keel of the premaxilla.

The outer surface of the premaxilla was covered in foramina

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (;Entry "foramen"

in

(openings) of varying sizes. The upper of the two backward-extending processes of the premaxilla was long and low, and formed most of the upper border of the elongated naris. It had a dip towards the font, which made the area by its base concave in profile. The underside of the premaxilla containing the in

alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

(tooth sockets) was oval. The maxilla was shallow, and was depressed around the antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among extant archosaurs, birds ...

(a large opening in front of the eye), forming a recess that was rounded towards the front, and smoother than the rest of the maxilla. A foramen called the preantorbital fenestra opened into this recess at the front bend. Large foramina ran on the side of the maxilla, above the alveoli. A deep nutrient groove ran backward from the subnarial pit along the base of the interdental plates

The interdental plate refers to the bone-filled mesial-distal region between the teeth. The word "''interdental''" is a combination of "''inter''" + "''dental''" (meaning "''between the teeth''") which originated in approximately 1870. In paleobi ...

(or rugosae) of the maxilla.

orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a p ...

(eye socket), and supported the bottom of the back of the crest. Uniquely for this genus, the rim above the orbit continued hindwards and ended in a small, almost triangular process behind the orbit, which curved slightly outwards. Since only a short part of the upper surface of this process is unbroken, the rest of the crest may have risen above the skull over a distance of ~. The preserved part of the crest in UCMP 77270 is tallest around the midpoint of the antorbital fenestra's length. UCMP 77270 preserves the concave shelf between the bases of the crests, and when seen from the front, they projected upwards and to the sides at an ~80° angle. Welles found the crests reminiscent of a double-crested cassowary

Cassowaries ( tpi, muruk, id, kasuari) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'' in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites (flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones) and are native to the tropical forest ...

, while Marsh and Rowe stated they were probably covered in keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

or keratinized skin. They pointed out that by comparison with helmeted guineafowl, the keratin on the crests of ''Dilophosaurus'' could have enlarged them much more than what is indicated by the bone. As only one specimen preserves much of the crests, whether they differed between individuals is unknown. CT scans show that air sacs

Air sacs are spaces within an organism where there is the constant presence of air. Among modern animals, birds possess the most air sacs (9–11), with their extinct dinosaurian relatives showing a great increase in the pneumatization (presence ...

(pockets of air that provide strength for and lighten bones) were present in the bones that surrounded the brain, and were continuous with the sinus

Sinus may refer to:

Anatomy

* Sinus (anatomy), a sac or cavity in any organ or tissue

** Paranasal sinuses, air cavities in the cranial bones, especially those near the nose, including:

*** Maxillary sinus, is the largest of the paranasal sinuses, ...

cavities in the front of the skull. The antorbital fenestra was continuous with the side of the crests, which indicates the crests also had air sacs (a ridge of bone forms a roof over the antorbital fenestrae in most other theropods).

The orbit was oval, and narrow towards the bottom. The

The orbit was oval, and narrow towards the bottom. The jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anato ...

had two upwards pointing processes, the first of which formed part of the lower margin of the antorbital fenestra, and part of the lower margin of the orbit. A projection from the quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms upper ...

into the lateral temporal fenestra (opening behind the eye) gave this a reniform (kidney-shaped) outline. The foramen magnum

The foramen magnum ( la, great hole) is a large, oval-shaped opening in the occipital bone of the skull. It is one of the several oval or circular openings (foramina) in the base of the skull. The spinal cord, an extension of the medulla oblon ...

(the large opening at the back of the braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, or brain-pan is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calvaria or skul ...

) was about half the breadth of the occipital condyle, which was itself cordiform (heart-shaped), and had a short neck and a groove on the side. The mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

was slender and delicate at the front, but the articular region (where it connected with the skull) was massive, and the mandible was deep around the mandibular fenestra

The skull is a bone protective Cranial cavity, cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible ...

(an opening on its side). The mandibular fenestra was small in ''Dilophosaurus'', compared to that of coelophysoids, and reduced from front to back, uniquely for this genus. The dentary bone

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(the front part of the mandible where most of the teeth there were attached) had an up-curved rather than pointed chin. The chin had a large foramen at the tip, and a row of small foramina ran in rough parallel with the upper edge of the dentary. On the inner side, the mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral halves ...

(where the two halves of the lower jaw connected) was flat and smooth, and showed no sign of being fused with its opposite half. A Meckelian foramen The Meckelian groove (or Meckel's groove, Meckelian fossa, or Meckelian foramen, or Meckelian canal) is an opening in the medial (inner) surface of the mandible (lower jaw) which exposes the Meckelian cartilage.retroarticular process of the mandible (a backwards projection) was long.

''Dilophosaurus'' had four teeth in each premaxilla, 12 in each maxilla, and 17 in each dentary. The teeth were generally long, thin, and recurved, with relatively small bases. They were compressed sideways, oval in cross-section at the base, lenticular (lens-shaped) above, and slightly concave on their outer and inner sides. The largest tooth of the maxilla was either in or near the fourth alveolus, and the height of the tooth crowns decreased hindwards. The first tooth of the maxilla pointed slightly forwards from its alveolus because the lower border of the prexamilla process (which projected backward towards the maxilla) was upturned. The teeth of the dentary were much smaller than those of the maxilla. The third or fourth tooth in the dentary of ''Dilophosaurus'' and some coelophysoids was the largest there, and seems to have fit into the subnarial gap of the upper jaw. Most of the teeth had serrations on the front and back edges, which were offset by vertical grooves, and were smaller at the front. About 31 to 41 serrations were on the front edges, and 29 to 33 were on the back. At least the second and third teeth of the premaxilla had serrations, but the fourth tooth did not. The teeth were covered in a thin layer of enamel, thick, which extended far towards their bases. The alveoli were elliptical to almost circular, and all were larger than the bases of the teeth they contained, which may therefore have been loosely held in the jaws. Though the number of alveoli in the dentary would seem to indicate that the teeth were very crowded, they were rather far apart, due to the larger size of their alveoli. The jaws contained replacement teeth at various stages of eruption. The interdental plates between the teeth were very low.

Welles thought ''Dilophosaurus'' a megalosaur in 1954, but revised his opinion in 1970 after discovering that it had crests. By 1974, Welles and the paleontologist Robert A. Long found ''Dilophosaurus'' to be a ceratosauroid. In 1984 Welles found that ''Dilophosaurus'' exhibited features of both

Welles thought ''Dilophosaurus'' a megalosaur in 1954, but revised his opinion in 1970 after discovering that it had crests. By 1974, Welles and the paleontologist Robert A. Long found ''Dilophosaurus'' to be a ceratosauroid. In 1984 Welles found that ''Dilophosaurus'' exhibited features of both  Lamanna and colleagues pointed out in 1998 that since ''Dilophosaurus'' was discovered to have had crests on its skull, other similarly crested theropods have been discovered (including ''Sinosaurus''), and that this feature is, therefore, not unique to the genus, and of limited use for determining interrelationships within their group. Paleontologist Adam M. Yates described the genus ''

Lamanna and colleagues pointed out in 1998 that since ''Dilophosaurus'' was discovered to have had crests on its skull, other similarly crested theropods have been discovered (including ''Sinosaurus''), and that this feature is, therefore, not unique to the genus, and of limited use for determining interrelationships within their group. Paleontologist Adam M. Yates described the genus '' In 2019, paleontologists Marion Zahner and Winand Brinkmann found the members of the Dilophosauridae to be successive basal sister taxa of the Averostra rather than a

In 2019, paleontologists Marion Zahner and Winand Brinkmann found the members of the Dilophosauridae to be successive basal sister taxa of the Averostra rather than a

The paleontologist Robert E. Weems proposed in 2003 that ''Eubrontes'' tracks were not produced by a theropod, but by a

The paleontologist Robert E. Weems proposed in 2003 that ''Eubrontes'' tracks were not produced by a theropod, but by a

Welles found that ''Dilophosaurus'' did not have a powerful bite, due to weakness caused by the subnarial gap. He thought that it used its front premaxillary teeth for plucking and tearing rather than biting, and the maxillary teeth further back for piercing and slicing. He thought that it was probably a scavenger rather than a predator, and that if it did kill large animals, it would have done so with its hands and feet rather than its jaws. Welles did not find evidence of

Welles found that ''Dilophosaurus'' did not have a powerful bite, due to weakness caused by the subnarial gap. He thought that it used its front premaxillary teeth for plucking and tearing rather than biting, and the maxillary teeth further back for piercing and slicing. He thought that it was probably a scavenger rather than a predator, and that if it did kill large animals, it would have done so with its hands and feet rather than its jaws. Welles did not find evidence of  In 2018, Marsh and Rowe reported that the holotype specimen of the sauropodomorph ''

In 2018, Marsh and Rowe reported that the holotype specimen of the sauropodomorph ''

Welles envisioned ''Dilophosaurus'' as an active, clearly bipedal animal, similar to an enlarged

Welles envisioned ''Dilophosaurus'' as an active, clearly bipedal animal, similar to an enlarged  In 2018, Senter and Corwin Sullivan examined the range of motion in the fore limb joints of ''Dilophosaurus'' by manipulating the bones, to test hypothesized functions of the fore limbs. They also took into account that experiments with

In 2018, Senter and Corwin Sullivan examined the range of motion in the fore limb joints of ''Dilophosaurus'' by manipulating the bones, to test hypothesized functions of the fore limbs. They also took into account that experiments with

Welles conceded that suggestions as to the function of the crests of ''Dilophosaurus'' were conjectural, but thought that, though the crests had no grooves to indicate vascularization, they could have been used for

Welles conceded that suggestions as to the function of the crests of ''Dilophosaurus'' were conjectural, but thought that, though the crests had no grooves to indicate vascularization, they could have been used for

Welles originally interpreted the smaller ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens as juveniles, and the larger specimen as an adult, later interpreting them as different species. Paul suggested that the differences between the specimens was perhaps due to sexual dimorphism, as was seemingly also apparent in ''Coelophysis'', which had "robust" and "gracile" forms of the same size, that might otherwise have been regarded as separate species. Following this scheme, the smaller ''Dilophosaurus'' specimen would represent a "gracile" example.

In 2005 Tykoski found that most ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens known were juvenile individuals, with only the largest an adult, based on the level of co-ossification of the bones. In 2005 Gay found no evidence of the sexual dimorphism suggested by Paul (but supposedly present in ''Coelophysis''), and attributed the variation seen between ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens to individual variation and

Welles originally interpreted the smaller ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens as juveniles, and the larger specimen as an adult, later interpreting them as different species. Paul suggested that the differences between the specimens was perhaps due to sexual dimorphism, as was seemingly also apparent in ''Coelophysis'', which had "robust" and "gracile" forms of the same size, that might otherwise have been regarded as separate species. Following this scheme, the smaller ''Dilophosaurus'' specimen would represent a "gracile" example.

In 2005 Tykoski found that most ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens known were juvenile individuals, with only the largest an adult, based on the level of co-ossification of the bones. In 2005 Gay found no evidence of the sexual dimorphism suggested by Paul (but supposedly present in ''Coelophysis''), and attributed the variation seen between ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens to individual variation and

Welles noted various

Welles noted various  The number of traumatic events that led to these features is not certain, and it is possible that they were all caused by a single encounter, for example by crashing into a tree or rock during a fight with another animal, which may have caused puncture wounds with its claws. Since all the injuries had healed, it is certain that the ''Dilophosaurus'' survived for a long time after these events, for months, perhaps years. The use of the forelimbs for prey capture must have been compromised during the healing process. The dinosaur may therefore have endured a long period of fasting or subsisted on prey that was small enough for it to dispatch with the mouth and feet, or with one forelimb.

According to Senter and Juengst, the high degree of pain the dinosaur might have experienced in multiple locations for long durations also shows that it was a hardy animal. They noted that paleopathologies in dinosaurs are underreported, and that even though Welles had thoroughly described the holotype, he had mentioned only one of the pathologies found by them. They suggested that such features may sometimes be omitted because descriptions of species are concerned with their characteristics rather than abnormalities, or because such features are difficult to recognize. Senter and Sullivan found that the pathologies significantly altered the range of motion in the right shoulder and right third finger of the holotype, and that estimates for range of motion may therefore not match those made for a healthy forelimb.

The number of traumatic events that led to these features is not certain, and it is possible that they were all caused by a single encounter, for example by crashing into a tree or rock during a fight with another animal, which may have caused puncture wounds with its claws. Since all the injuries had healed, it is certain that the ''Dilophosaurus'' survived for a long time after these events, for months, perhaps years. The use of the forelimbs for prey capture must have been compromised during the healing process. The dinosaur may therefore have endured a long period of fasting or subsisted on prey that was small enough for it to dispatch with the mouth and feet, or with one forelimb.

According to Senter and Juengst, the high degree of pain the dinosaur might have experienced in multiple locations for long durations also shows that it was a hardy animal. They noted that paleopathologies in dinosaurs are underreported, and that even though Welles had thoroughly described the holotype, he had mentioned only one of the pathologies found by them. They suggested that such features may sometimes be omitted because descriptions of species are concerned with their characteristics rather than abnormalities, or because such features are difficult to recognize. Senter and Sullivan found that the pathologies significantly altered the range of motion in the right shoulder and right third finger of the holotype, and that estimates for range of motion may therefore not match those made for a healthy forelimb.

''Dilophosaurus'' is known from the Kayenta Formation, which dates to the

''Dilophosaurus'' is known from the Kayenta Formation, which dates to the

''Dilophosaurus'' was featured in the 1990 novel ''

''Dilophosaurus'' was featured in the 1990 novel '' The geologist J. Bret Bennington noted in 1996 that though ''Dilophosaurus'' probably did not have a frill and could not spit venom like in the movie, its bite could have been venomous, as has been claimed for the

The geologist J. Bret Bennington noted in 1996 that though ''Dilophosaurus'' probably did not have a frill and could not spit venom like in the movie, its bite could have been venomous, as has been claimed for the

Postcranial skeleton

''Dilophosaurus'' had 10 cervical (neck), 14 dorsal (back), and 45 caudal (tail) vertebrae, and air sacs grew into the vertebrae. It had a long neck, which was probably flexed nearly 90° by the skull and by the shoulder, holding the skull in a horizontal posture. The cervical vertebrae were unusually light; their centra (the "bodies" of the vertebrae) were hollowed out bypleurocoels

Skeletal pneumaticity is the presence of air spaces within bones. It is generally produced during development by excavation of bone by pneumatic diverticula (air sacs) from an air-filled space, such as the lungs or nasal cavity. Pneumatization is h ...

(depressions on the sides) and centrocoels (cavities on the inside). The arches of the cervical vertebrae also had pneumatic

Pneumatics (from Greek ‘wind, breath’) is a branch of engineering that makes use of gas or pressurized air.

Pneumatic systems used in Industrial sector, industry are commonly powered by compressed air or compressed inert gases. A central ...

fossae (or chonoses), conical recesses so large that the bones separating them were sometimes paper-thin. The centra were plano-concave, flat to weakly convex at the front and deeply cupped (or concave) at the back, similar to ''Ceratosaurus

''Ceratosaurus'' (from Ancient Greek, Greek κέρας/κέρατος, ' meaning "horn" and wikt:σαῦρος, σαῦρος ' meaning "lizard") was a carnivorous Theropoda, theropod dinosaur in the Late Jurassic Period (geology), period (Kim ...

''. This indicates that the neck was flexible, though it had long, overlapping cervical ribs, which were fused to the centra. The cervical ribs were slender and may have bent easily.

The atlas bone

In anatomy, the atlas (C1) is the most superior (first) cervical vertebra of the spine and is located in the neck. It is named for Atlas of Greek mythology because, just as Atlas supported the globe, it supports the entire head.

The atlas is ...

(the first cervical vertebra which attaches to the skull) had a small, cubic centrum, and had a concavity at the front where it formed a cup for the occipital condyle

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape, and their anteri ...

(protuberance that connects with the atlas vertebra) at the back of the skull. The axis bone (the second cervical vertebra) had a heavy spine, and its postzygapophyses

The articular processes or zygapophyses (Greek ζυγον = "yoke" (because it links two vertebrae) + απο = "away" + φυσις = "process") of a vertebra are projections of the vertebra that serve the purpose of fitting with an adjacent vertebr ...

(the processes of the vertebrae that articulated with the prezygapophyses of a following vertebrae) were met by long prezygapophyses that curved upwards from the third cervical vertebra. The centra and neural spines of the cervical vertebrae were long and low, and the spines were stepped in side view, forming "shoulders" at the front and back, as well as taller, central "caps" that gave the appearance of a Maltese cross

The Maltese cross is a cross symbol, consisting of four " V" or arrowhead shaped concave quadrilaterals converging at a central vertex at right angles, two tips pointing outward symmetrically.

It is a heraldic cross variant which developed f ...

(cruciform) when seen from above, distinctive features of this dinosaur. The posterior centrodiapophyseal lamina of the cervicals showed serial variation, bifurcating and reuniting down the neck, a unique feature. The neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae were also low and expanded front and back, which formed strong attachments for ligaments

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal li ...

. Uniquely for this genus, additional laminae emanated from the middle trunk vertebrae's anterior centrodiapophyseal laminae and posterior centrodiapophyseal laminae. The sacral vertebrae

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

which occupied the length of the ilium blade did not appear to be fused. The rib of the first sacral vertebra articulated with the preacetabular process of the ilium, a distinct feature. The centra of the caudal vertebrae were very consistent in length, but their diameter became smaller towards the back, and they went from elliptical to circular in cross-section.

The scapulae

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either ...

(shoulder blades) were moderate in length and concave on their inner sides to follow the body's curvature. The scapulae were wide, particularly the upper part, which was rectangular (or squared off), a unique feature. The coracoids were elliptical, and not fused to the scapulae. The lower hind portions of the coracoids had a "horizontal buttress" next to the biceps tuber, unique for this genus. The arms were powerful, and had deep pits and stout processes for attachment of muscles and ligaments. The humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

(upper arm bone) was large and slender, and the ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

(lower arm bone) was stout and straight, with a stout olecranon

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony eminence of the ulna, a long bone in the forearm that projects behind the elbow. It forms the most pointed portion of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit. The olecranon ...

. The hands had four fingers: the first was shorter but stronger than the following two fingers, with a large claw, and the two following fingers were longer and slenderer, with smaller claws. The claws were curved and sharp. The third finger was reduced, and the fourth was vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

(retained, but without function).

The crest

Crest or CREST may refer to:

Buildings

*The Crest (Huntington, New York), a historic house in Suffolk County, New York

*"The Crest", an alternate name for 63 Wall Street, in Manhattan, New York

*Crest Castle (Château Du Crest), Jussy, Switzerla ...

of the ilium was highest over the ilial peduncle (the downwards process of the ilium), and its outer side was concave. The foot of the pubic bone

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing ( ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior ...

was only slightly expanded, whereas the lower end was much more expanded on the ischium

The ischium () form ...

, which also had a very thin shaft. The hind legs were large, with a slighter longer femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

(thigh bone) than tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

(lower leg bone), the opposite of, for example, ''Coelophysis''. The femur was massive; its shaft was sigmoid

Sigmoid means resembling the lower-case Greek letter sigma (uppercase Σ, lowercase σ, lowercase in word-final position ς) or the Latin letter S. Specific uses include:

* Sigmoid function, a mathematical function

* Sigmoid colon, part of the l ...

-shaped (curved like an 'S'), and its greater trochanter

The greater trochanter of the femur is a large, irregular, quadrilateral eminence and a part of the skeletal system.

It is directed lateral and medially and slightly posterior. In the adult it is about 2–4 cm lower than the femoral head.Stan ...

was centered on the shaft. The tibia had a developed tuberosity

In the skeleton of humans and other animals, a tubercle, tuberosity or apophysis is a protrusion or eminence that serves as an attachment for skeletal muscles. The muscles attach by tendons, where the enthesis is the connective tissue between the ...

and was expanded at the lower end. The astragalus bone

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known as the tarsus. The tarsus forms the lower part of the ankle joint. It transmits the entire weight of the body from the ...

(ankle bone) was separated from the tibia and the calcaneum

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is the point of the hock.

St ...

, and formed half of the socket for the fibula. It had long, stout feet with three well-developed toes that bore large claws, which were much less curved than those of the hand. The third toe was the stoutest, and the smaller first toe (the hallux

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being '' digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being '' pl ...

) was kept off the ground.

Classification

Welles thought ''Dilophosaurus'' a megalosaur in 1954, but revised his opinion in 1970 after discovering that it had crests. By 1974, Welles and the paleontologist Robert A. Long found ''Dilophosaurus'' to be a ceratosauroid. In 1984 Welles found that ''Dilophosaurus'' exhibited features of both

Welles thought ''Dilophosaurus'' a megalosaur in 1954, but revised his opinion in 1970 after discovering that it had crests. By 1974, Welles and the paleontologist Robert A. Long found ''Dilophosaurus'' to be a ceratosauroid. In 1984 Welles found that ''Dilophosaurus'' exhibited features of both Coelurosauria

Coelurosauria (; from Greek, meaning "hollow tailed lizards") is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

Coelurosauria is a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that includes compsognathids, tyrann ...

and Carnosauria

Carnosauria is an extinct large group of predatory dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Starting from the 1990s, scientists have discovered some very large carnosaurs in the carcharodontosaurid family, such as ''Gig ...

, the two main groups into which theropods had hitherto been divided, based on body size, and he suggested this division was inaccurate. He found ''Dilophosaurus'' to be closest to those theropods that were usually placed in the family Halticosauridae, particularly ''Liliensternus''.

In 1988, paleontologist Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

classified the halticosaurs as a subfamily of the family Coelophysidae

Coelophysidae is a family of primitive carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. Most species were relatively small in size. The family flourished in the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods, and has been found on numerous continents. Many members of C ...

, and suggested that ''Dilophosaurus'' could have been a direct descendant of ''Coelophysis''. Paul also considered the possibility that spinosaurs were late-surviving dilophosaurs, based on similarity of the kinked snout, nostril position, and slender teeth of ''Baryonyx

''Baryonyx'' () is a genus of theropod dinosaur which lived in the Barremian stage of the Early Cretaceous period, about 130–125 million years ago. The first skeleton was discovered in 1983 in the Smokejack Clay Pit, of Surrey, England, in se ...

''. In 1994, paleontologist Thomas R. Holtz

Thomas Richard Holtz Jr. (born September 13, 1965) is an American vertebrate palaeontologist, author, and principal lecturer at the University of Maryland, College Park, University of Maryland's Department of Geology. He has published extensively ...

placed ''Dilophosaurus'' in the group Coelophysoidea, along with but separate from the Coelophysidae. He placed the Coelophysoidea in the group Ceratosauria. In 2000, paleontologist James H. Madsen and Welles divided Ceratosauria into the families Ceratosauridae

Ceratosauridae is an extinct family of theropod dinosaurs belonging to the infraorder Ceratosauria. The family's type genus, ''Ceratosaurus'', was first found in Jurassic rocks from North America. Ceratosauridae is made up of the genera ''Cer ...

and Dilophosauridae, with ''Dilophosaurus'' as the sole member of the latter family.

Lamanna and colleagues pointed out in 1998 that since ''Dilophosaurus'' was discovered to have had crests on its skull, other similarly crested theropods have been discovered (including ''Sinosaurus''), and that this feature is, therefore, not unique to the genus, and of limited use for determining interrelationships within their group. Paleontologist Adam M. Yates described the genus ''

Lamanna and colleagues pointed out in 1998 that since ''Dilophosaurus'' was discovered to have had crests on its skull, other similarly crested theropods have been discovered (including ''Sinosaurus''), and that this feature is, therefore, not unique to the genus, and of limited use for determining interrelationships within their group. Paleontologist Adam M. Yates described the genus ''Dracovenator

''Dracovenator'' () is a genus of neotheropod dinosaur that lived approximately 201 to 199 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now South Africa. ''Dracovenator'' was a medium-sized, moderately-built, ground ...

'' from South Africa in 2005, and found it closely related to ''Dilophosaurus'' and ''Zupaysaurus

''Zupaysaurus'' (; "ZOO-pay-SAWR-us") is an extinct genus of early theropod dinosaur living during the Norian stage of the Late Triassic in what is now Argentina. Fossils of the dinosaur were found in the Los Colorados Formation of the Ischigu ...

''. His cladistic analysis

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived chara ...

suggested they did not belong in the Coelophysoidea, but rather in the Neotheropoda

Neotheropoda (meaning "new theropods") is a clade that includes coelophysoids and more advanced theropod dinosaurs, and is the only group of theropods that survived the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. All neotheropods became extinct by the ...

, a more derived

Derive may refer to:

* Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguatio ...

(or "advanced") group. He proposed that if ''Dilophosaurus'' was more derived than the Coelophysoidea, the features it shared with this group may have been inherited from basal (or "primitive") theropods, indicating that theropods may have passed through a "coelophysoid stage" in their early evolution.

In 2007, paleontologist Nathan D. Smith and colleagues found the crested theropod ''Cryolophosaurus

''Cryolophosaurus'' ( or ; "CRY-oh-loaf-oh-SAWR-us") is a genus of large theropod dinosaur known from only a single species ''Cryolophosaurus ellioti'', from the early Jurassic of Antarctica. It was one of the largest theropods of the Early Jura ...

'' to be the sister species

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

of ''Dilophosaurus'', and grouped them with ''Dracovenator'' and ''Sinosaurus''. This clade was more derived than the Coelophysoidea, but more basal than the Ceratosauria, thereby placing basal theropods in a ladder-like arrangement. In 2012, Carrano and colleagues found that the group of crested theropods proposed by Smith and colleagues was based on features that relate to the presence of such crests, but that the features of the rest of the skeleton were less consistent. They instead found that ''Dilophosaurus'' was a coelophysoid, with ''Cryolophosaurus'' and ''Sinosaurus'' being more derived, as basal members of the group Tetanurae

Tetanurae (/ˌtɛtəˈnjuːriː/ or "stiff tails") is a clade that includes most theropod dinosaurs, including megalosauroids, allosauroids, tyrannosauroids, ornithomimosaurs, compsognathids and maniraptorans (including birds). Tetanurans ar ...

.

Paleontologist Christophe Hendrickx and colleagues defined the Dilophosauridae to include ''Dilophosaurus'' and ''Dracovenator'' in 2015, and noted that while general uncertainty exists about the placement of this group, it appears to be slightly more derived than the Coelophysoidea, and the sister group to the Averostra

Averostra, or "bird snouts", is a clade that includes most theropod dinosaurs, namely Ceratosauria and Tetanurae, and represent the only group of post-Early Jurassic theropods. Both survived into the Cretaceous period. When the Cretaceous–Pa ...

. The Dilophosauridae share features with the Coelophysoidea such as the subnarial gap and the front teeth of the maxilla pointing forwards, while features shared with Averostra include a fenestra at the front of the maxilla and a reduced number of teeth in the maxilla. They suggested that the cranial crests of ''Cryolophosaurus'' and ''Sinosaurus'' had either evolved convergently, or were a feature inherited from a common ancestor. The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

is based on that published by Hendrickx and colleagues, itself based on earlier studies:

In 2019, paleontologists Marion Zahner and Winand Brinkmann found the members of the Dilophosauridae to be successive basal sister taxa of the Averostra rather than a

In 2019, paleontologists Marion Zahner and Winand Brinkmann found the members of the Dilophosauridae to be successive basal sister taxa of the Averostra rather than a monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

clade (a natural group), but noted that some of their analyses did find the group valid, containing ''Dilophosaurus'', ''Dracovenator'', ''Cryolophosaurus'', and possibly ''Notatesseraeraptor

''Notatesseraeraptor'' ("feature mosaic tile thief"; from the Latin "nota", feature; "tesserae", tiles used to make a mosaic, in reference to the mixture of features normally found on dilophosaurids and coelophysoids; and "raptor", thief) is a g ...

'' as the basal-most member. They therefore provided a diagnosis for the Dilophosauridae, based on features in the lower jaw. In the phylogenetic analysis accompanying their 2020 redescription, Marsh and Rowe found all specimens of ''Dilophosaurus'' to form a monophyletic group, sister to Averostra, and more derived than ''Cryolophosaurus''. Their analysis did not find support for Dilophosauridae, and they suggested cranial crests were a plesiomorphic

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, and ...

(ancestral) trait of Ceratosauria and Tetanurae.

Ichnology

Variousichnotaxa

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxa'' comes from the Greek ίχνος, ''ichnos'' meaning ''track'' and ταξις, ''taxis'' meaning ...

(taxa based on trace fossils

A trace fossil, also known as an ichnofossil (; from el, ἴχνος ''ikhnos'' "trace, track"), is a fossil record of biological activity but not the preserved remains of the plant or animal itself. Trace fossils contrast with body fossils, ...

) have been attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'' or similar theropods. In 1971, Welles reported dinosaur footprints from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona, on two levels and below where the original ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens were found. The lower footprints were tridactyl

In biology, dactyly is the arrangement of digits (fingers and toes) on the hands, feet, or sometimes wings of a tetrapod animal. It comes from the Greek word δακτυλος (''dáktylos'') = "finger".

Sometimes the ending "-dactylia" is use ...

(three-toed), and could have been made by ''Dilophosaurus''; Welles created the new ichnogenus and species ''Dilophosauripus williamsi'' based on them, in honor of Williams, the discoverer of the first ''Dilophosaurus'' skeletons. The type specimen is a cast of a large footprint catalogued as UCMP 79690-4, with casts of three other prints included in the hypodigm. In 1984, Welles conceded that no way had been found to prove or disprove that the footprints belonged to ''Dilophosaurus''. In 1996, the paleontologists Michael Morales and Scott Bulkey reported a trackway

Historic roads (historic trails in USA and Canada) are paths or routes that have historical importance due to their use over a period of time. Examples exist from prehistoric times until the early 20th century. They include ancient trackway ...

of the ichnogenus ''Eubrontes

''Eubrontes'' is the name of fossilised dinosaur footprints dating from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. They have been identified from France, Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Australia (Queensland), USA, India and C ...

'' from the Kayenta Formation made by a very large theropod. They noted it could have been made by a very large ''Dilophosaurus'' individual, but found that unlikely, as they estimated the trackmaker would have been tall at the hips, compared to the of ''Dilophosaurus''.

The paleontologist Gerard Gierliński examined tridactyl footprints from the Holy Cross Mountains

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

in Poland