Dickensian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

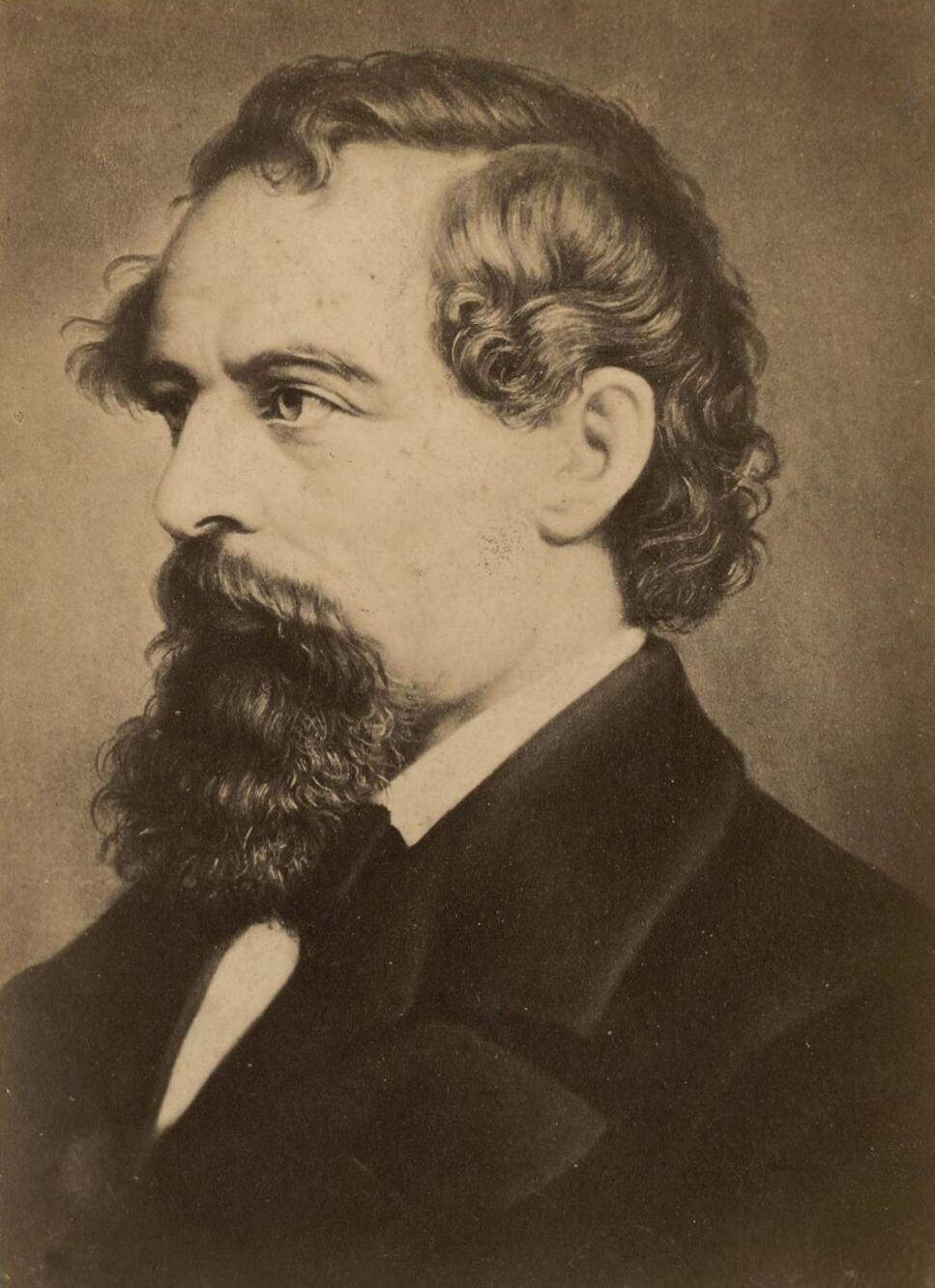

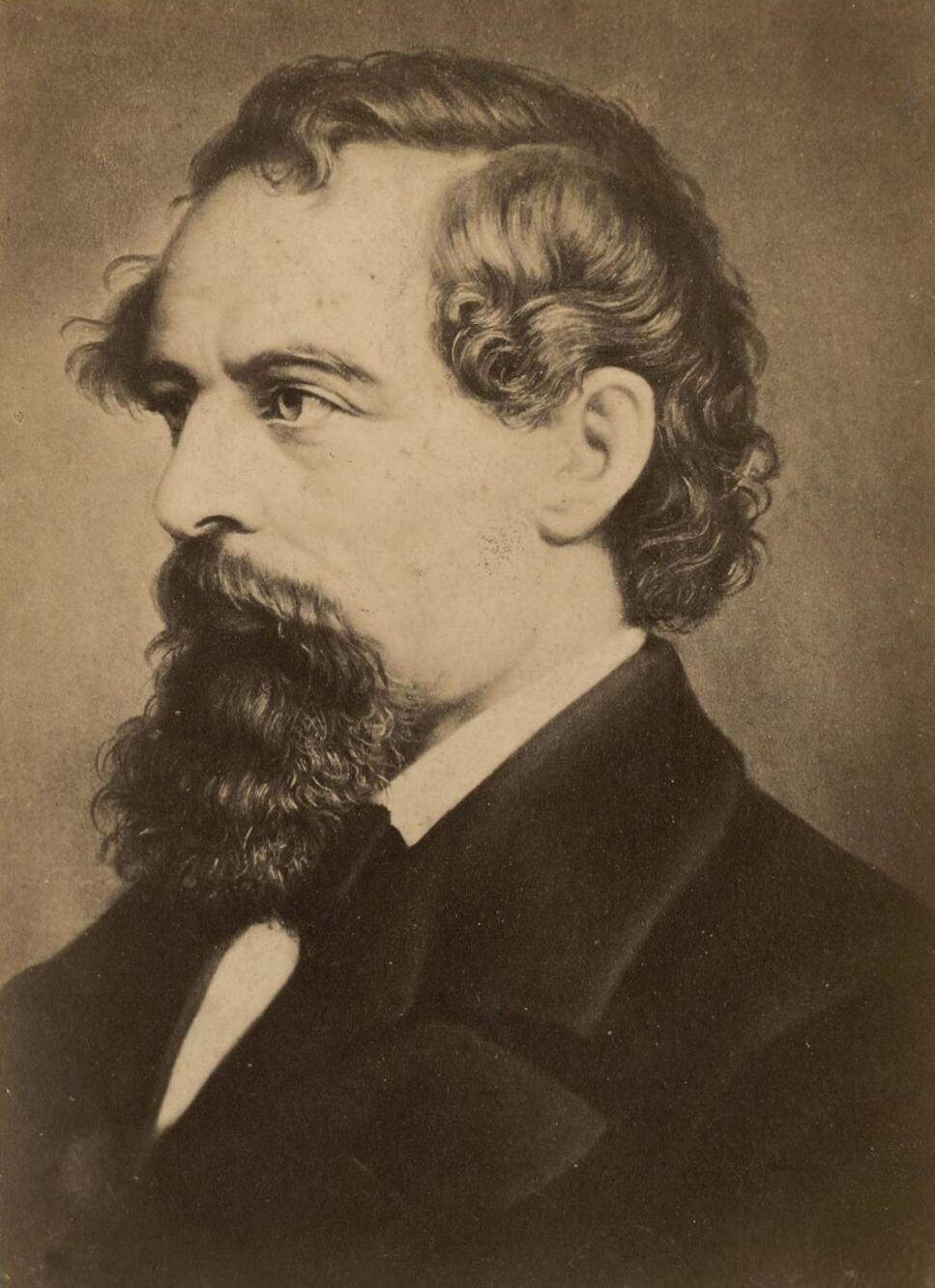

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era.. His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime and, by the 20th century, critics and scholars had recognised him as a literary genius. His novels and short stories are widely read today.

Born in Portsmouth, Dickens left school at the age of 12 to work in a boot-blacking factory when his father was incarcerated in a debtors' prison. After three years he returned to school, before he began his literary career as a journalist. Dickens edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five

Charles Dickens was born on 7 February 1812 at 1 Mile End Terrace (now 393 Commercial Road),

Charles Dickens was born on 7 February 1812 at 1 Mile End Terrace (now 393 Commercial Road),  This period came to an end in June 1822, when John Dickens was recalled to Navy Pay Office headquarters at Somerset House and the family (except for Charles, who stayed behind to finish his final term at school) moved to

This period came to an end in June 1822, when John Dickens was recalled to Navy Pay Office headquarters at Somerset House and the family (except for Charles, who stayed behind to finish his final term at school) moved to  A few months after his imprisonment, John Dickens's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was released from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors and he and his family left the Marshalsea, for the home of Mrs Roylance.

Charles's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, did not immediately support his removal from the boot-blacking warehouse. This influenced Dickens's view that a father should rule the family and a mother find her proper sphere inside the home: "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." His mother's failure to request his return was a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.

Righteous indignation stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, '' David Copperfield'': "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!"

Dickens was eventually sent to the Wellington House Academy in

A few months after his imprisonment, John Dickens's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was released from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors and he and his family left the Marshalsea, for the home of Mrs Roylance.

Charles's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, did not immediately support his removal from the boot-blacking warehouse. This influenced Dickens's view that a father should rule the family and a mother find her proper sphere inside the home: "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." His mother's failure to request his return was a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.

Righteous indignation stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, '' David Copperfield'': "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!"

Dickens was eventually sent to the Wellington House Academy in

In 1832, at the age of 20, Dickens was energetic and increasingly self-confident. He enjoyed mimicry and popular entertainment, lacked a clear, specific sense of what he wanted to become, and yet knew he wanted fame. Drawn to the theatre – he became an early member of the

In 1832, at the age of 20, Dickens was energetic and increasingly self-confident. He enjoyed mimicry and popular entertainment, lacked a clear, specific sense of what he wanted to become, and yet knew he wanted fame. Drawn to the theatre – he became an early member of the  Dickens made rapid progress both professionally and socially. He began a friendship with

Dickens made rapid progress both professionally and socially. He began a friendship with  On 2 April 1836, after a one-year engagement, and between episodes two and three of ''The Pickwick Papers'', Dickens married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1815–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the '' Evening Chronicle''. They were married in St Luke's Church,

On 2 April 1836, after a one-year engagement, and between episodes two and three of ''The Pickwick Papers'', Dickens married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1815–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the '' Evening Chronicle''. They were married in St Luke's Church,  His success as a novelist continued. The young Queen Victoria read both ''Oliver Twist'' and ''The Pickwick Papers'', staying up until midnight to discuss them. '' Nicholas Nickleby'' (1838–39), ''

His success as a novelist continued. The young Queen Victoria read both ''Oliver Twist'' and ''The Pickwick Papers'', staying up until midnight to discuss them. '' Nicholas Nickleby'' (1838–39), ''

He described his impressions in a travelogue, '' American Notes for General Circulation''. In ''Notes'', Dickens includes a powerful condemnation of slavery which he had attacked as early as ''The Pickwick Papers'', correlating the emancipation of the poor in England with the abolition of slavery abroad citing newspaper accounts of runaway slaves disfigured by their masters. In spite of the abolitionist sentiments gleaned from his trip to America, some modern commentators have pointed out inconsistencies in Dickens's views on racial inequality. For instance, he has been criticized for his subsequent acquiescence in Governor Eyre's harsh crackdown during the 1860s Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica and his failure to join other British progressives in condemning it. From Richmond, Virginia, Dickens returned to Washington, D.C., and started a trek westward, with brief pauses in Cincinnati and Louisville, to St. Louis, Missouri. While there, he expressed a desire to see an American prairie before returning east. A group of 13 men then set out with Dickens to visit Looking Glass Prairie, a trip 30 miles into Illinois.

During his American visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures, raising the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his work in America. He persuaded a group of 25 writers, headed by

He described his impressions in a travelogue, '' American Notes for General Circulation''. In ''Notes'', Dickens includes a powerful condemnation of slavery which he had attacked as early as ''The Pickwick Papers'', correlating the emancipation of the poor in England with the abolition of slavery abroad citing newspaper accounts of runaway slaves disfigured by their masters. In spite of the abolitionist sentiments gleaned from his trip to America, some modern commentators have pointed out inconsistencies in Dickens's views on racial inequality. For instance, he has been criticized for his subsequent acquiescence in Governor Eyre's harsh crackdown during the 1860s Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica and his failure to join other British progressives in condemning it. From Richmond, Virginia, Dickens returned to Washington, D.C., and started a trek westward, with brief pauses in Cincinnati and Louisville, to St. Louis, Missouri. While there, he expressed a desire to see an American prairie before returning east. A group of 13 men then set out with Dickens to visit Looking Glass Prairie, a trip 30 miles into Illinois.

During his American visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures, raising the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his work in America. He persuaded a group of 25 writers, headed by  Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his Christmas stories, ''

Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his Christmas stories, ''

Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens in May 1846 about setting up a home for the redemption of fallen women of the working class. Coutts envisioned a home that would replace the punitive regimes of existing institutions with a reformative environment conducive to education and proficiency in domestic household chores. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named

Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens in May 1846 about setting up a home for the redemption of fallen women of the working class. Coutts envisioned a home that would replace the punitive regimes of existing institutions with a reformative environment conducive to education and proficiency in domestic household chores. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named

Dickens honoured the figure of Jesus Christ. He is regarded as a professing Christian. His son, Henry Fielding Dickens, described him as someone who "possessed deep religious convictions". In the early 1840s, he had shown an interest in Unitarian Christianity and Robert Browning remarked that "Mr Dickens is an enlightened Unitarian." Professor Gary Colledge has written that he "never strayed from his attachment to popular lay

Dickens honoured the figure of Jesus Christ. He is regarded as a professing Christian. His son, Henry Fielding Dickens, described him as someone who "possessed deep religious convictions". In the early 1840s, he had shown an interest in Unitarian Christianity and Robert Browning remarked that "Mr Dickens is an enlightened Unitarian." Professor Gary Colledge has written that he "never strayed from his attachment to popular lay

In 1857, Dickens hired professional actresses for the play '' The Frozen Deep'', written by him and his protégé,

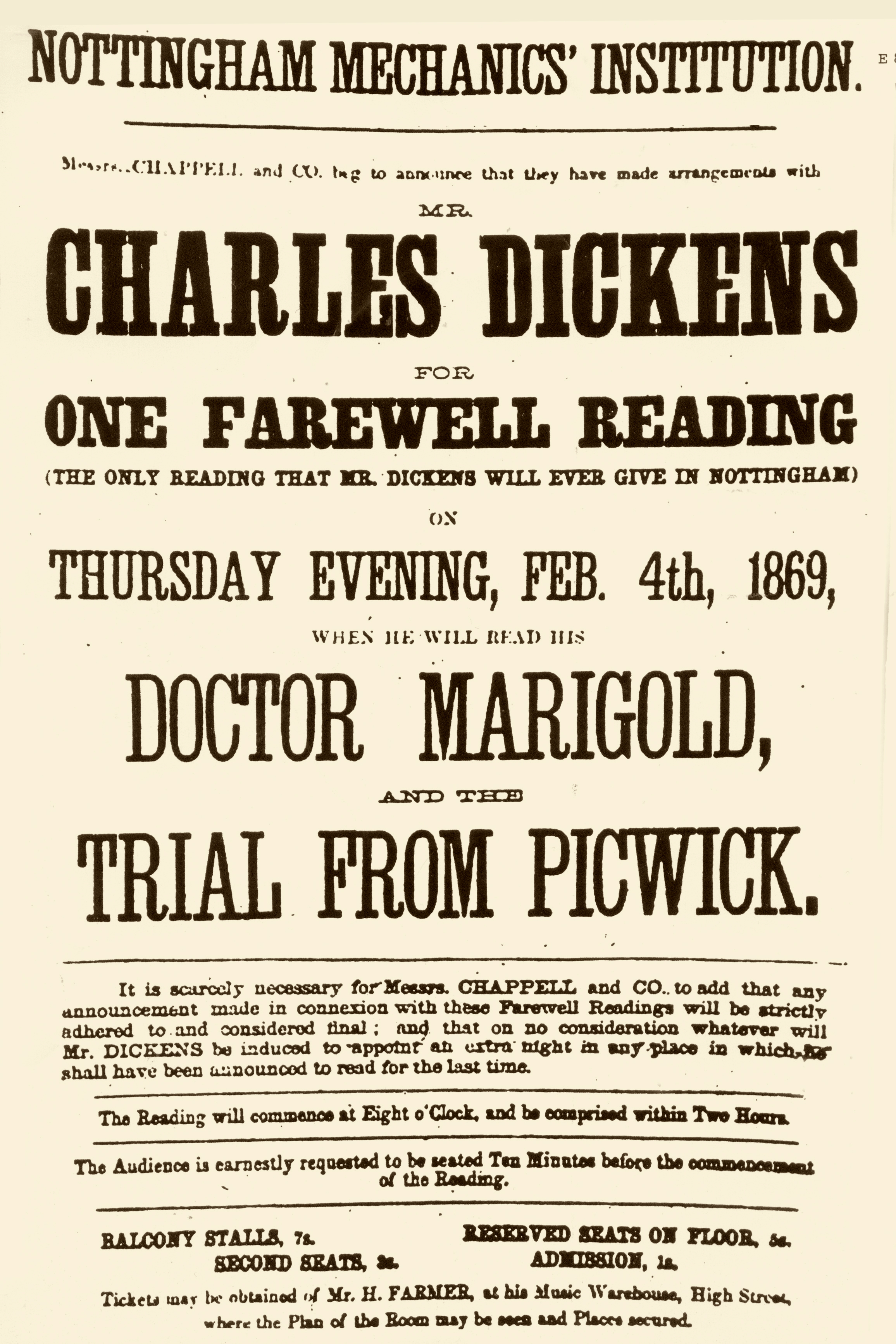

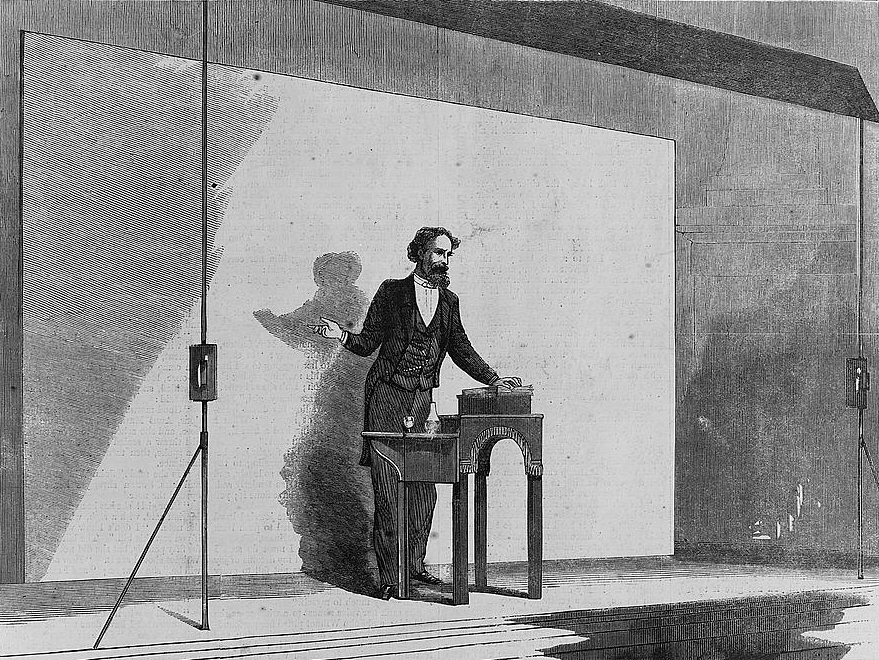

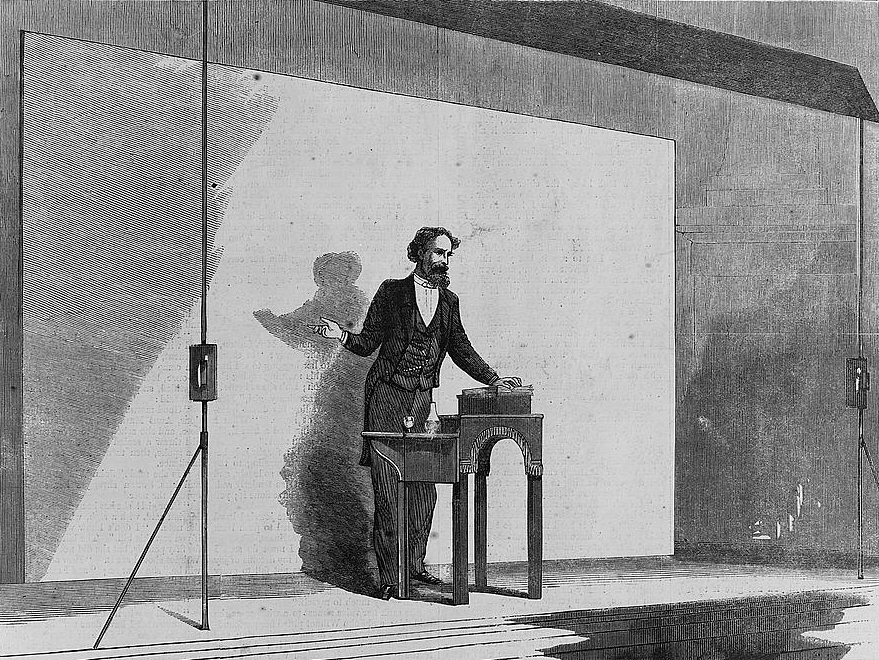

In 1857, Dickens hired professional actresses for the play '' The Frozen Deep'', written by him and his protégé,  After separating from Catherine, Dickens undertook a series of hugely popular and remunerative reading tours which, together with his journalism, were to absorb most of his creative energies for the next decade, in which he was to write only two more novels. His first reading tour, lasting from April 1858 to February 1859, consisted of 129 appearances in 49 towns throughout England, Scotland and Ireland. Dickens's continued fascination with the theatrical world was written into the theatre scenes in ''Nicholas Nickleby'', but more importantly he found an outlet in public readings. In 1866, he undertook a series of public readings in England and Scotland, with more the following year in England and Ireland.

After separating from Catherine, Dickens undertook a series of hugely popular and remunerative reading tours which, together with his journalism, were to absorb most of his creative energies for the next decade, in which he was to write only two more novels. His first reading tour, lasting from April 1858 to February 1859, consisted of 129 appearances in 49 towns throughout England, Scotland and Ireland. Dickens's continued fascination with the theatrical world was written into the theatre scenes in ''Nicholas Nickleby'', but more importantly he found an outlet in public readings. In 1866, he undertook a series of public readings in England and Scotland, with more the following year in England and Ireland.

Other works soon followed, including ''

Other works soon followed, including ''

On 9 June 1865, while returning from Paris with Ellen Ternan, Dickens was involved in the

On 9 June 1865, while returning from Paris with Ellen Ternan, Dickens was involved in the

While he contemplated a second visit to the United States, the outbreak of the

While he contemplated a second visit to the United States, the outbreak of the

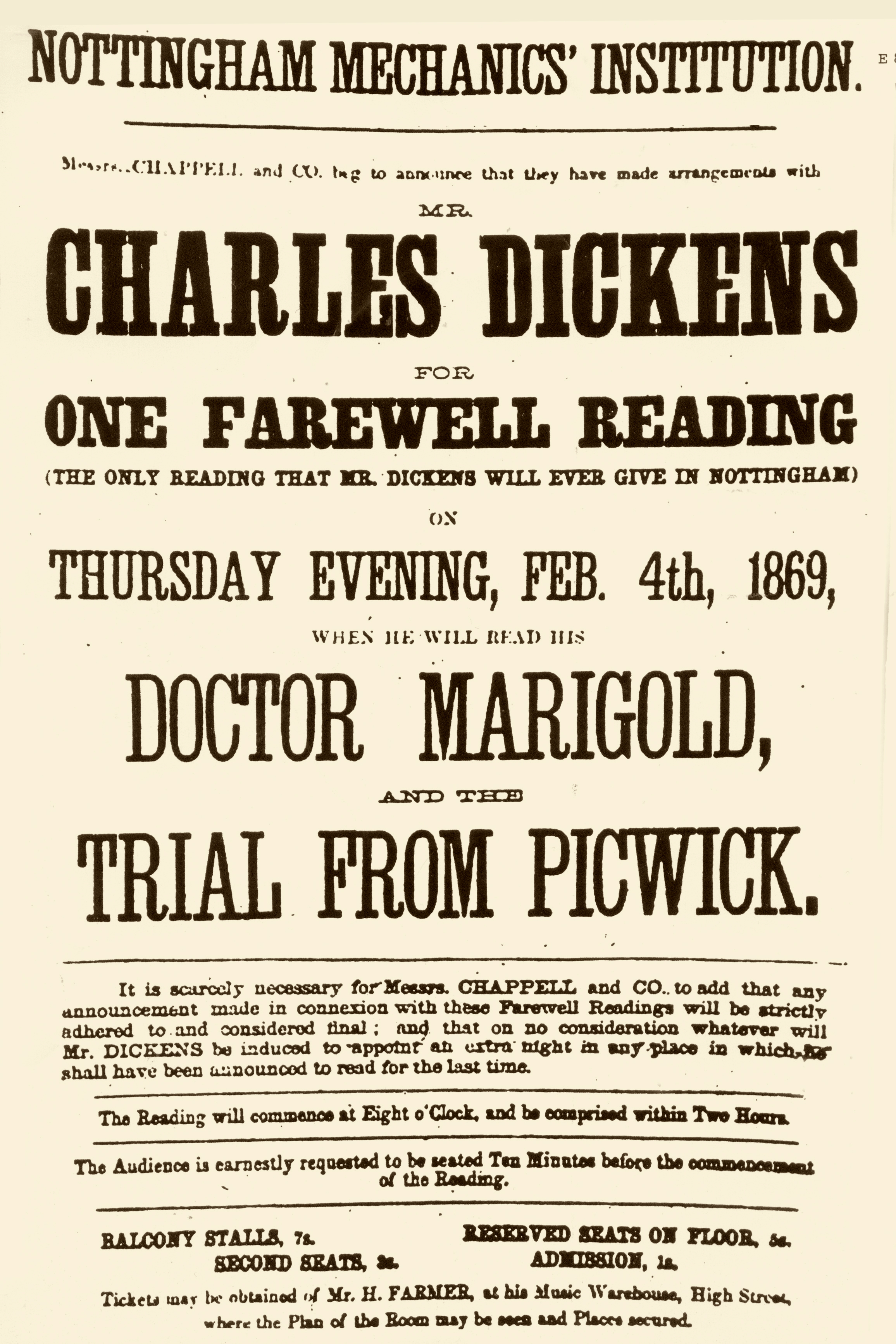

In 1868–69, Dickens gave a series of "farewell readings" in England, Scotland and Ireland, beginning on 6 October. He managed, of a contracted 100 readings, to give 75 in the provinces, with a further 12 in London. As he pressed on he was affected by giddiness and fits of paralysis. He had a stroke on 18 April 1869 in Chester. He collapsed on 22 April 1869, at

In 1868–69, Dickens gave a series of "farewell readings" in England, Scotland and Ireland, beginning on 6 October. He managed, of a contracted 100 readings, to give 75 in the provinces, with a further 12 in London. As he pressed on he was affected by giddiness and fits of paralysis. He had a stroke on 18 April 1869 in Chester. He collapsed on 22 April 1869, at

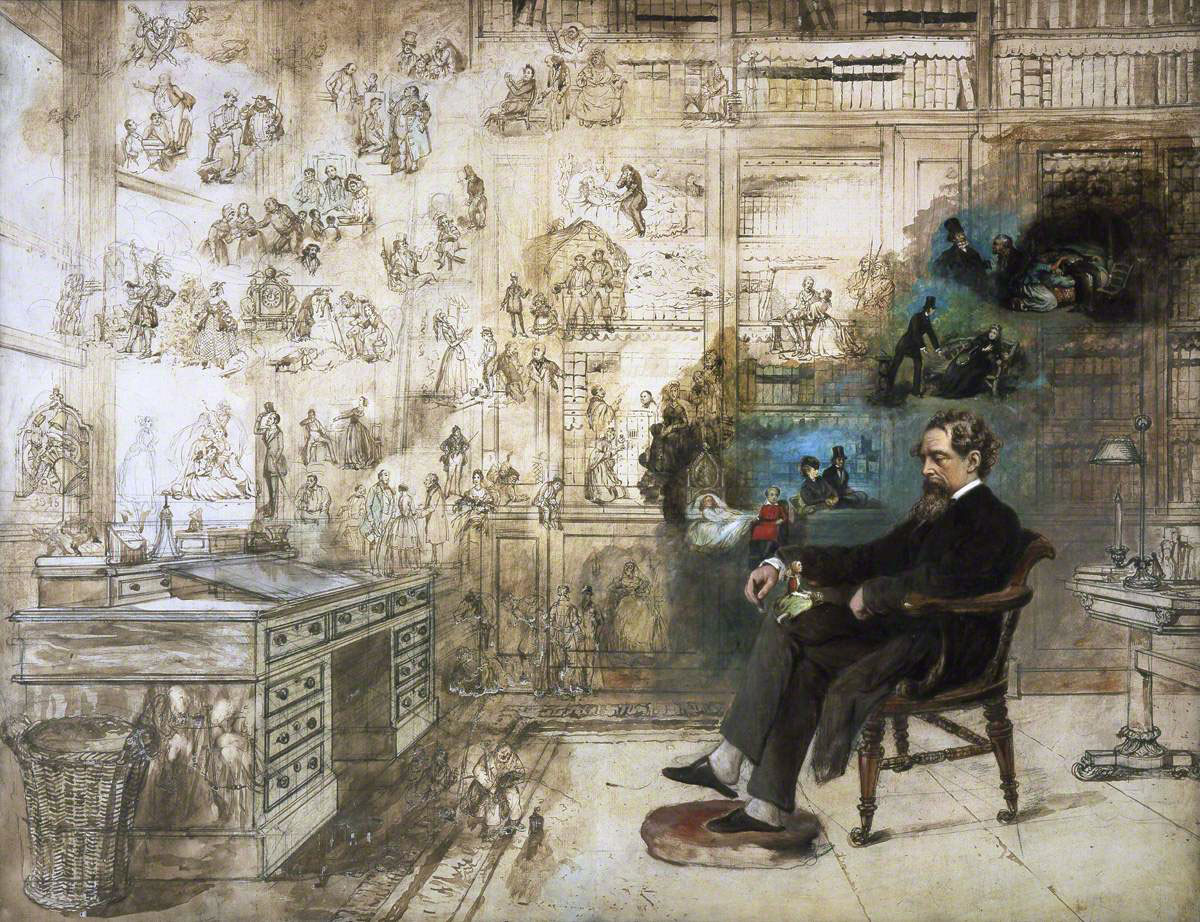

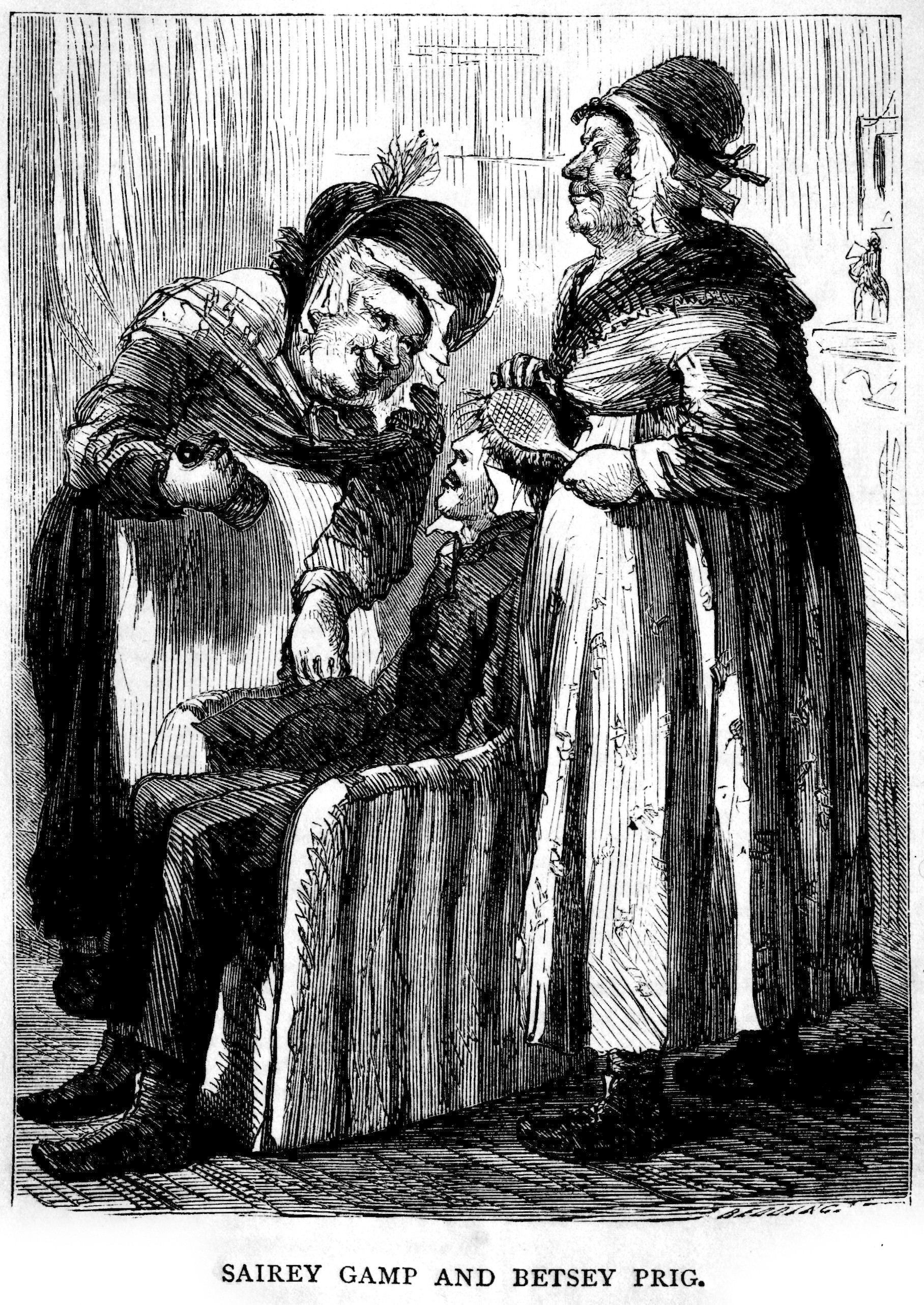

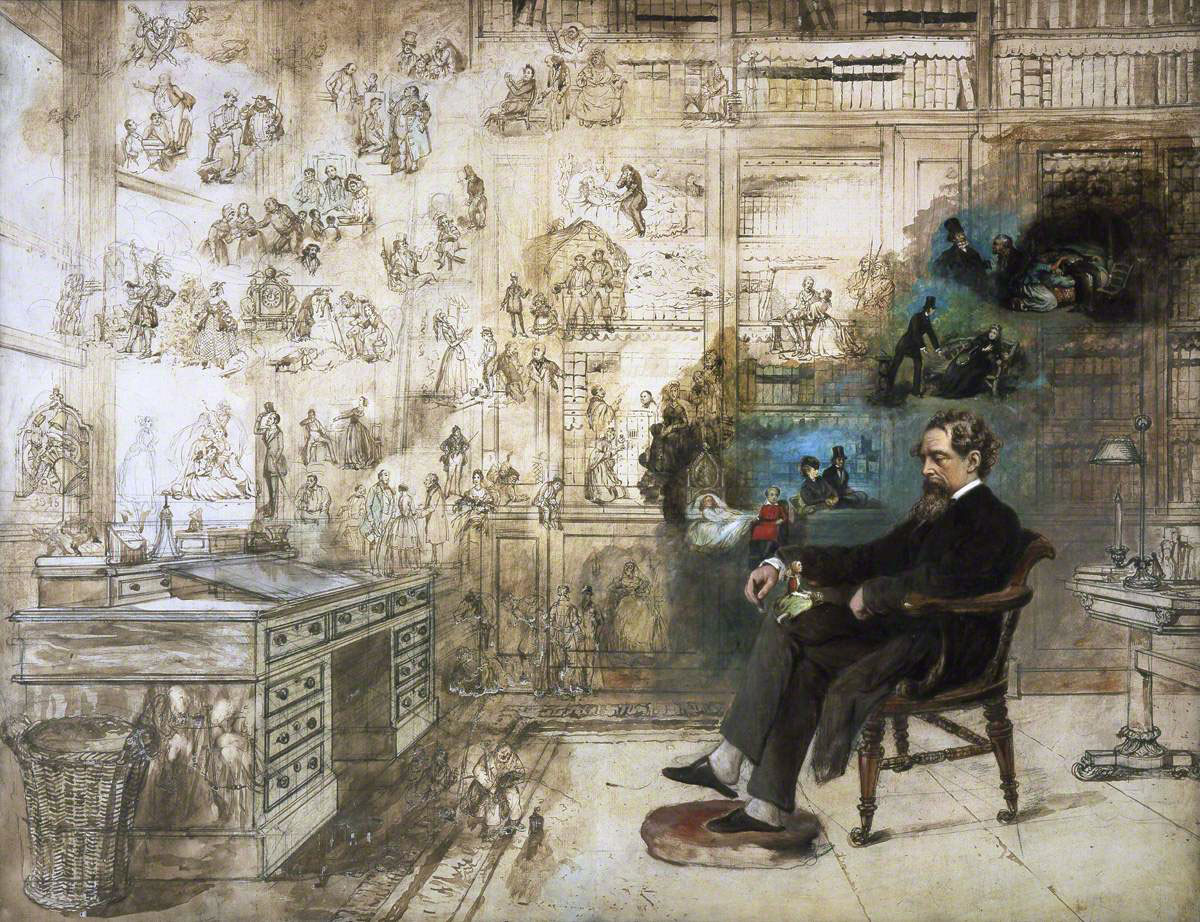

Dickens's writing style is marked by a profuse linguistic creativity.. Satire, flourishing in his gift for caricature, is his forte. An early reviewer compared him to Hogarth for his keen practical sense of the ludicrous side of life, though his acclaimed mastery of varieties of class idiom may in fact mirror the conventions of contemporary popular theatre. Dickens worked intensively on developing arresting names for his characters that would reverberate with associations for his readers and assist the development of motifs in the storyline, giving what one critic calls an "allegorical impetus" to the novels' meanings. To cite one of numerous examples, the name Mr Murdstone in ''David Copperfield'' conjures up twin allusions to murder and stony coldness. His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery – he calls one character the "Noble Refrigerator" – are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens's acclaimed flights of fancy.

The author worked closely with his illustrators, supplying them with a summary of the work at the outset and thus ensuring that his characters and settings were exactly how he envisioned them. He briefed the illustrator on plans for each month's instalment so that work could begin before he wrote them.

Dickens's writing style is marked by a profuse linguistic creativity.. Satire, flourishing in his gift for caricature, is his forte. An early reviewer compared him to Hogarth for his keen practical sense of the ludicrous side of life, though his acclaimed mastery of varieties of class idiom may in fact mirror the conventions of contemporary popular theatre. Dickens worked intensively on developing arresting names for his characters that would reverberate with associations for his readers and assist the development of motifs in the storyline, giving what one critic calls an "allegorical impetus" to the novels' meanings. To cite one of numerous examples, the name Mr Murdstone in ''David Copperfield'' conjures up twin allusions to murder and stony coldness. His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery – he calls one character the "Noble Refrigerator" – are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens's acclaimed flights of fancy.

The author worked closely with his illustrators, supplying them with a summary of the work at the outset and thus ensuring that his characters and settings were exactly how he envisioned them. He briefed the illustrator on plans for each month's instalment so that work could begin before he wrote them.

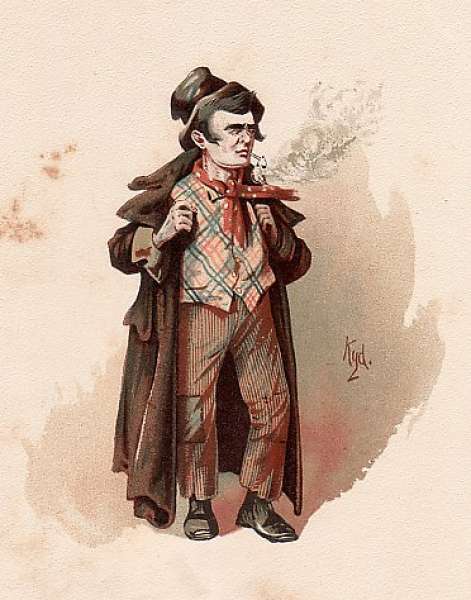

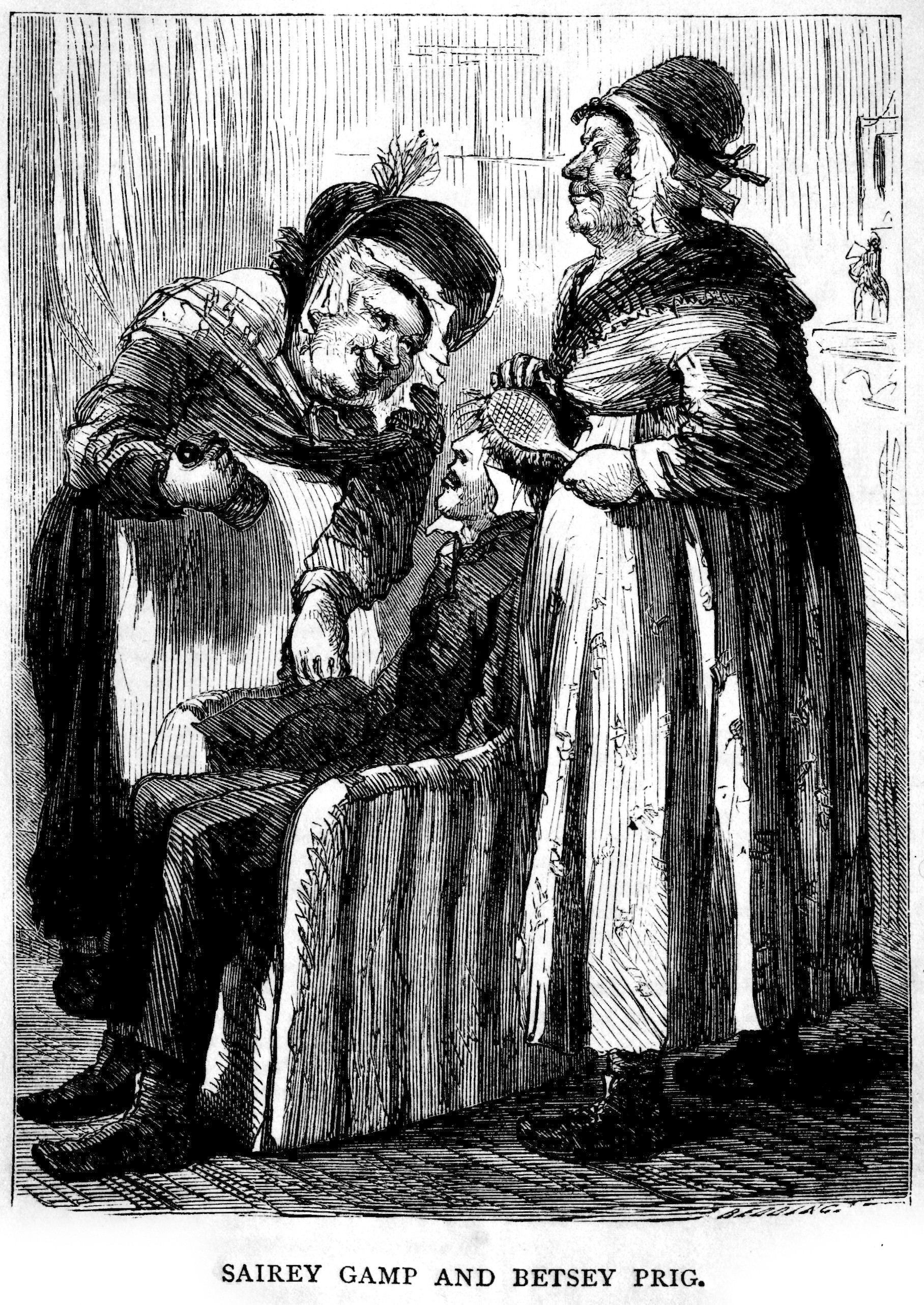

His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. "Gamp" became a slang expression for an umbrella from the character Mrs Gamp, and "Pickwickian", "Pecksniffian" and "Gradgrind" all entered dictionaries due to Dickens's original portraits of such characters who were, respectively, quixotic, hypocritical and vapidly factual. The character that made Dickens famous, Sam Weller became known for his Wellerisms—one-liners that turned proverbs on their heads. Many were drawn from real life: Mrs Nickleby is based on his mother, although she didn't recognise herself in the portrait, just as Mr Micawber is constructed from aspects of his father's 'rhetorical exuberance'; Harold Skimpole in ''Bleak House'' is based on James Henry Leigh Hunt; his wife's dwarfish chiropodist recognised herself in Miss Mowcher in ''David Copperfield''. Perhaps Dickens's impressions on his meeting with Hans Christian Andersen informed the delineation of Uriah Heep (a term synonymous with

His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. "Gamp" became a slang expression for an umbrella from the character Mrs Gamp, and "Pickwickian", "Pecksniffian" and "Gradgrind" all entered dictionaries due to Dickens's original portraits of such characters who were, respectively, quixotic, hypocritical and vapidly factual. The character that made Dickens famous, Sam Weller became known for his Wellerisms—one-liners that turned proverbs on their heads. Many were drawn from real life: Mrs Nickleby is based on his mother, although she didn't recognise herself in the portrait, just as Mr Micawber is constructed from aspects of his father's 'rhetorical exuberance'; Harold Skimpole in ''Bleak House'' is based on James Henry Leigh Hunt; his wife's dwarfish chiropodist recognised herself in Miss Mowcher in ''David Copperfield''. Perhaps Dickens's impressions on his meeting with Hans Christian Andersen informed the delineation of Uriah Heep (a term synonymous with

Authors frequently draw their portraits of characters from people they have known in real life. ''David Copperfield'' is regarded by many as a veiled autobiography of Dickens. The scenes of interminable court cases and legal arguments in ''Bleak House'' reflect Dickens's experiences as a law clerk and court reporter, and in particular his direct experience of the law's procedural delay during 1844 when he sued publishers in Chancery for breach of copyright. Dickens's father was sent to prison for debt and this became a common theme in many of his books, with the detailed depiction of life in the Marshalsea prison in ''Little Dorrit'' resulting from Dickens's own experiences of the institution. Lucy Stroughill, a childhood sweetheart, may have affected several of Dickens's portraits of girls such as Little Em'ly in ''David Copperfield'' and Lucie Manette in ''A Tale of Two Cities.''

Dickens may have drawn on his childhood experiences, but he was also ashamed of them and would not reveal that this was where he gathered his realistic accounts of squalor. Very few knew the details of his early life until six years after his death, when John Forster published a biography on which Dickens had collaborated. Though Skimpole brutally sends up Leigh Hunt, some critics have detected in his portrait features of Dickens's own character, which he sought to exorcise by self-parody.

Authors frequently draw their portraits of characters from people they have known in real life. ''David Copperfield'' is regarded by many as a veiled autobiography of Dickens. The scenes of interminable court cases and legal arguments in ''Bleak House'' reflect Dickens's experiences as a law clerk and court reporter, and in particular his direct experience of the law's procedural delay during 1844 when he sued publishers in Chancery for breach of copyright. Dickens's father was sent to prison for debt and this became a common theme in many of his books, with the detailed depiction of life in the Marshalsea prison in ''Little Dorrit'' resulting from Dickens's own experiences of the institution. Lucy Stroughill, a childhood sweetheart, may have affected several of Dickens's portraits of girls such as Little Em'ly in ''David Copperfield'' and Lucie Manette in ''A Tale of Two Cities.''

Dickens may have drawn on his childhood experiences, but he was also ashamed of them and would not reveal that this was where he gathered his realistic accounts of squalor. Very few knew the details of his early life until six years after his death, when John Forster published a biography on which Dickens had collaborated. Though Skimpole brutally sends up Leigh Hunt, some critics have detected in his portrait features of Dickens's own character, which he sought to exorcise by self-parody.

A pioneer of the serial publication of narrative fiction, Dickens wrote most of his major novels in monthly or weekly instalments in journals such as '' Master Humphrey's Clock'' and ''

A pioneer of the serial publication of narrative fiction, Dickens wrote most of his major novels in monthly or weekly instalments in journals such as '' Master Humphrey's Clock'' and ''

Dickens's novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. Simon Callow states, "From the moment he started to write, he spoke for the people, and the people loved him for it." He was a fierce critic of the poverty and

Dickens's novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. Simon Callow states, "From the moment he started to write, he spoke for the people, and the people loved him for it." He was a fierce critic of the poverty and

Dickens is often described as using idealised characters and highly sentimental scenes to contrast with his

Dickens is often described as using idealised characters and highly sentimental scenes to contrast with his

Dickens was the most popular novelist of his time, and remains one of the best-known and most-read of English authors. His works have never gone out of print, and have been adapted continually for the screen since the invention of cinema, with at least 200 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens's works documented. Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime – early productions included ''The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain'' which was performed in the West End's

Dickens was the most popular novelist of his time, and remains one of the best-known and most-read of English authors. His works have never gone out of print, and have been adapted continually for the screen since the invention of cinema, with at least 200 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens's works documented. Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime – early productions included ''The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain'' which was performed in the West End's  As his career progressed, Dickens's fame and the demand for his public readings were unparalleled. In 1868 '' The Times'' wrote, "Amid all the variety of 'readings', those of Mr Charles Dickens stand alone." A Dickens biographer, Edgar Johnson, wrote in the 1950s: "It was lwaysmore than a reading; it was an extraordinary exhibition of acting that seized upon its auditors with a mesmeric possession." Juliet John backed the claim for Dickens "to be called the first self-made global media star of the age of mass culture." Comparing his reception at public readings to those of a contemporary pop star, ''The Guardian'' states, "People sometimes fainted at his shows. His performances even saw the rise of that modern phenomenon, the 'speculator' or ticket tout (scalpers) – the ones in New York City escaped detection by borrowing respectable-looking hats from the waiters in nearby restaurants."

Among fellow writers, there was a range of opinions on Dickens.

As his career progressed, Dickens's fame and the demand for his public readings were unparalleled. In 1868 '' The Times'' wrote, "Amid all the variety of 'readings', those of Mr Charles Dickens stand alone." A Dickens biographer, Edgar Johnson, wrote in the 1950s: "It was lwaysmore than a reading; it was an extraordinary exhibition of acting that seized upon its auditors with a mesmeric possession." Juliet John backed the claim for Dickens "to be called the first self-made global media star of the age of mass culture." Comparing his reception at public readings to those of a contemporary pop star, ''The Guardian'' states, "People sometimes fainted at his shows. His performances even saw the rise of that modern phenomenon, the 'speculator' or ticket tout (scalpers) – the ones in New York City escaped detection by borrowing respectable-looking hats from the waiters in nearby restaurants."

Among fellow writers, there was a range of opinions on Dickens.

Museums and festivals celebrating Dickens's life and works exist in many places with which Dickens was associated. These include the Charles Dickens Museum in London, the historic home where he wrote '' Oliver Twist'', '' The Pickwick Papers'' and '' Nicholas Nickleby''; and the Charles Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth, the house in which he was born. The original manuscripts of many of his novels, as well as printers' proofs, first editions, and illustrations from the collection of Dickens's friend John Forster are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Dickens's will stipulated that no memorial be erected in his honour; nonetheless, a life-size bronze statue of Dickens entitled '' Dickens and Little Nell'', cast in 1890 by

Museums and festivals celebrating Dickens's life and works exist in many places with which Dickens was associated. These include the Charles Dickens Museum in London, the historic home where he wrote '' Oliver Twist'', '' The Pickwick Papers'' and '' Nicholas Nickleby''; and the Charles Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth, the house in which he was born. The original manuscripts of many of his novels, as well as printers' proofs, first editions, and illustrations from the collection of Dickens's friend John Forster are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Dickens's will stipulated that no memorial be erected in his honour; nonetheless, a life-size bronze statue of Dickens entitled '' Dickens and Little Nell'', cast in 1890 by  ''A Christmas Carol'' is most probably his best-known story, with frequent new adaptations. It is also the most-filmed of Dickens's stories, with many versions dating from the early years of cinema. According to the historian Ronald Hutton, the current state of the observance of Christmas is largely the result of a mid-Victorian revival of the holiday spearheaded by ''A Christmas Carol''. Dickens catalysed the emerging Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the dwindling community-based and church-centred observations, as new middle-class expectations arose. Its archetypal figures (Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Christmas ghosts) entered into Western cultural consciousness. "

''A Christmas Carol'' is most probably his best-known story, with frequent new adaptations. It is also the most-filmed of Dickens's stories, with many versions dating from the early years of cinema. According to the historian Ronald Hutton, the current state of the observance of Christmas is largely the result of a mid-Victorian revival of the holiday spearheaded by ''A Christmas Carol''. Dickens catalysed the emerging Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the dwindling community-based and church-centred observations, as new middle-class expectations arose. Its archetypal figures (Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Christmas ghosts) entered into Western cultural consciousness. "

Becoming Dickens 'The Invention of a Novelist

", London: Harvard University Press, 2011 * * * * * Johnson, Edgar, ''Charles Dickens: his tragedy and triumph'', New York: Simon and Schuster, 1952. In two volumes. * * * * * Manning, Mick & Granström, Brita, ''Charles Dickens: Scenes From An Extraordinary Life'', Frances Lincoln Children's Books, 2011. * * * * * * * * * *

Charles Dickens's works on Bookwise

* * * * * *

Charles Dickens

at the British Library

Charles Dickens on the Archives Hub

*Archival material a

Leeds University Library

The Dickens Fellowship

an international society dedicated to the study of Dickens and his Writings

Correspondence of Charles Dickens, with related papers, ca. 1834–1955

Finding aid to Charles Dickens papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Dickens Museum

Situated in a former Dickens House, 48

Dickens Birthplace Museum

Old Commercial Road, Portsmouth

Victoria and Albert Museum

The V&A's collections relating to Dickens

Charles Dickens's Traveling Kit

From th

at the Library of Congress

Charles Dickens's Walking Stick

From th

at the Library of Congress * Charles Dickens Collection: First editions of Charles Dickens's works included in the Leonard Kebler gift (dispersed in the Division's collection). From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dickens, Charles 1812 births 1870 deaths 19th-century biographers 19th-century British dramatists and playwrights 19th-century British newspaper founders 19th-century British non-fiction writers 19th-century British novelists 19th-century British poets 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights 19th-century English non-fiction writers 19th-century English novelists 19th-century English poets 19th-century essayists 19th-century historians 19th-century journalists 19th-century letter writers 19th-century philanthropists 19th-century pseudonymous writers 19th-century travel writers British Anglicans British biographers British historians British historical novelists British letter writers British male dramatists and playwrights British male essayists British male journalists British male non-fiction writers British male novelists British male poets British male short story writers British newspaper founders British philanthropists British prisoners and detainees British reformers British satirists British social commentators Burials at Westminster Abbey Children's rights activists Christian writers Court reporters Critics of religions Critics of the Catholic Church Cultural critics Educational reformers English Anglicans English biographers English essayists English historians English historical novelists English letter writers English male dramatists and playwrights English male journalists English male non-fiction writers English male novelists English male poets English male short story writers English newspaper founders English philanthropists English prisoners and detainees English reformers English satirists English social commentators English travel writers Ghost story writers Lecturers Literacy and society theorists People from Camden Town People from Chatham, Kent People from Higham, Kent People from Somers Town, London Social critics Social reformers Trope theorists Victorian novelists Writers about activism and social change Writers from London Writers from Portsmouth Writers of Gothic fiction Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period

novellas

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

, hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed readings extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer, and campaigned vigorously for children's rights, for education, and for other social reforms.

Dickens's literary success began with the 1836 serial publication of '' The Pickwick Papers'', a publishing phenomenon—thanks largely to the introduction of the character Sam Weller in the fourth episode—that sparked ''Pickwick'' merchandise and spin-offs. Within a few years Dickens had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire and keen observation of character and society. His novels, most of them published in monthly or weekly installments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication.. Cliffhanger endings in his serial publications kept readers in suspense. The instalment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience's reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback. For example, when his wife's chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in '' David Copperfield'' seemed to reflect her own disabilities, Dickens improved the character with positive features. His plots were carefully constructed and he often wove elements from topical events into his narratives. Masses of the illiterate poor would individually pay a halfpenny to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers.

His 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol

''A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas'', commonly known as ''A Christmas Carol'', is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. ''A Christmas Ca ...

'' remains especially popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every artistic genre. '' Oliver Twist'' and ''Great Expectations

''Great Expectations'' is the thirteenth novel by Charles Dickens and his penultimate completed novel. It depicts the education of an orphan nicknamed Pip (Great Expectations), Pip (the book is a ''bildungsroman''; a coming-of-age story). It ...

'' are also frequently adapted and, like many of his novels, evoke images of early Victorian London. His 1859 novel ''A Tale of Two Cities

''A Tale of Two Cities'' is a historical novel published in 1859 by Charles Dickens, set in London and Paris before and during the French Revolution. The novel tells the story of the French Doctor Manette, his 18-year-long imprisonment in the ...

'' (set in London and Paris) is his best-known work of historical fiction. The most famous celebrity of his era, he undertook, in response to public demand, a series of public reading tours in the later part of his career. The term ''Dickensian'' is used to describe something that is reminiscent of Dickens and his writings, such as poor social or working conditions, or comically repulsive characters.

Early life

Charles Dickens was born on 7 February 1812 at 1 Mile End Terrace (now 393 Commercial Road),

Charles Dickens was born on 7 February 1812 at 1 Mile End Terrace (now 393 Commercial Road), Landport

Landport is a district located on Portsea Island and is considered the city centre of modern-day Portsmouth, England. The district is centred around Commercial Road and encompasses the Guildhall, Civic Centre, Portsmouth and Southsea Statio ...

in Portsea Island

Portsea Island is a flat and low-lying natural island in area, just off the southern coast of Hampshire in England. Portsea Island contains the majority of the city of Portsmouth.

Portsea Island has the third-largest population of all ...

( Portsmouth), Hampshire, the second of eight children of Elizabeth Dickens

Elizabeth Culliford Dickens (née Barrow; 21 December 1789 – 13 September 1863) was the wife of John Dickens and the mother of British novelist Charles Dickens. She was the source for Mrs. Nickleby in her son's novel ''Nicholas Nickleby'' and ...

(née Barrow; 1789–1863) and John Dickens

John Dickens (21 August 1785 – 31 March 1851) was the father of famous English novelist Charles Dickens and was the model for Mr Micawber in his son's semi-autobiographical novel '' David Copperfield''.

Biography

The son of William Dickens ...

(1785–1851). His father was a clerk in the Navy Pay Office and was temporarily stationed in the district. He asked Christopher Huffam, rigger to His Majesty's Navy, gentleman, and head of an established firm, to act as godfather to Charles. Huffam is thought to be the inspiration for Paul Dombey, the owner of a shipping company in Dickens's novel '' Dombey and Son'' (1848).

In January 1815, John Dickens was called back to London and the family moved to Norfolk Street, Fitzrovia. When Charles was four, they relocated to Sheerness

Sheerness () is a town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 11,938, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby town ...

and thence to Chatham, Kent, where he spent his formative years until the age of 11. His early life seems to have been idyllic, though he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy".

Charles spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, including the picaresque novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel '' Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

, as well as '' Robinson Crusoe'' and ''Gil Blas

''Gil Blas'' (french: L'Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane ) is a picaresque novel by Alain-René Lesage published between 1715 and 1735. It was highly popular, and was translated several times into English, most notably as The Adventures of Gi ...

''. He read and reread ''The Arabian Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' and the Collected Farces of Elizabeth Inchbald. At age 7 he first saw Joseph Grimaldi—the father of modern clown

A clown is a person who performs comedy and arts in a state of open-mindedness using physical comedy, typically while wearing distinct makeup or costuming and reversing folkway-norms.

History

The most ancient clowns have been found in ...

ing—perform at the Star Theatre, Rochester. He later imitated Grimaldi's clowning on several occasions, and would also edit the ''Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi

''Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi'' is the 1838 autobiography of the pioneering nineteenth-century clown Joseph Grimaldi. It was edited by Charles Dickens who as a seven-year-old had first seen Grimaldi perform.

References

Notes

* Charles Dickens, ...

''.. He retained poignant memories of childhood, helped by an excellent memory of people and events, which he used in his writing. His father's brief work as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office afforded him a few years of private education, first at a dame school

Dame schools were small, privately run schools for young children that emerged in the British Isles and its colonies during the early modern period. These schools were taught by a “school dame,” a local woman who would educate children f ...

and then at a school run by William Giles, a dissenter, in Chatham.

This period came to an end in June 1822, when John Dickens was recalled to Navy Pay Office headquarters at Somerset House and the family (except for Charles, who stayed behind to finish his final term at school) moved to

This period came to an end in June 1822, when John Dickens was recalled to Navy Pay Office headquarters at Somerset House and the family (except for Charles, who stayed behind to finish his final term at school) moved to Camden Town

Camden Town (), often shortened to Camden, is a district of northwest London, England, north of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Camden, and identified in the London Plan as o ...

in London. The family had left Kent amidst rapidly mounting debts and, living beyond his means, John Dickens was forced by his creditors into the Marshalsea debtors' prison in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, London in 1824. His wife and youngest children joined him there, as was the practice at the time. Charles, then 12 years old, boarded with Elizabeth Roylance, a family friend, at 112 College Place, Camden Town. Mrs Roylance was "a reduced impoverished old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs Pipchin" in ''Dombey and Son''. Later, he lived in a back-attic in the house of an agent for the Insolvent Court, Archibald Russell, "a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman ... with a quiet old wife" and lame son, in Lant Street

Lant Street is a street south of Marshalsea Road in Southwark, south London, England.Lant Street Association

in Southwark. They provided the inspiration for the Garlands in ''The Old Curiosity Shop

''The Old Curiosity Shop'' is one of two novels (the other being ''Barnaby Rudge'') which Charles Dickens published along with short stories in his weekly serial ''Master Humphrey's Clock'', from 1840 to 1841. It was so popular that New York r ...

''.

On Sundays – with his sister Frances

Frances is a French and English given name of Latin origin. In Latin the meaning of the name Frances is 'from France' or 'free one.' The male version of the name in English is Francis. The original Franciscus, meaning "Frenchman", comes from the F ...

, free from her studies at the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke ...

– he spent the day at the Marshalsea. Dickens later used the prison as a setting in '' Little Dorrit''. To pay for his board and to help his family, Dickens was forced to leave school and work ten-hour days at Warren's Blacking Warehouse, on Hungerford Stairs, near the present Charing Cross railway station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashf ...

, where he earned six shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

s a week pasting labels on pots of boot blacking. The strenuous and often harsh working conditions made a lasting impression on Dickens and later influenced his fiction and essays, becoming the foundation of his interest in the reform of socio-economic and labour conditions, the rigours of which he believed were unfairly borne by the poor. He later wrote that he wondered "how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age". As he recalled to John Forster (from ''Life of Charles Dickens''):

When the warehouse was moved to Chandos Street in the smart, busy district of Covent Garden, the boys worked in a room in which the window gave onto the street. Small audiences gathered and watched them at work – in Dickens's biographer Simon Callow's estimation, the public display was "a new refinement added to his misery".

A few months after his imprisonment, John Dickens's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was released from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors and he and his family left the Marshalsea, for the home of Mrs Roylance.

Charles's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, did not immediately support his removal from the boot-blacking warehouse. This influenced Dickens's view that a father should rule the family and a mother find her proper sphere inside the home: "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." His mother's failure to request his return was a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.

Righteous indignation stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, '' David Copperfield'': "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!"

Dickens was eventually sent to the Wellington House Academy in

A few months after his imprisonment, John Dickens's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was released from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors and he and his family left the Marshalsea, for the home of Mrs Roylance.

Charles's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, did not immediately support his removal from the boot-blacking warehouse. This influenced Dickens's view that a father should rule the family and a mother find her proper sphere inside the home: "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." His mother's failure to request his return was a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.

Righteous indignation stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, '' David Copperfield'': "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!"

Dickens was eventually sent to the Wellington House Academy in Camden Town

Camden Town (), often shortened to Camden, is a district of northwest London, England, north of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Camden, and identified in the London Plan as o ...

, where he remained until March 1827, having spent about two years there. He did not consider it to be a good school: "Much of the haphazard, desultory teaching, poor discipline punctuated by the headmaster's sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr Creakle's Establishment in ''David Copperfield''.".

Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, of Holborn Court, Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wal ...

, as a junior clerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include record keeping, filing, staffing service c ...

from May 1827 to November 1828. He was a gifted mimic and impersonated those around him: clients, lawyers and clerks. He went to theatres obsessively: he claimed that for at least three years he went to the theatre every day. His favourite actor was Charles Mathews

Charles Mathews (28 June 1776, London – 28 June 1835, Devonport) was an English theatre manager and comic actor, well known during his time for his gift of impersonation and skill at table entertainment. His play ''At Home'', in which he pla ...

and Dickens learnt his " monopolylogues" (farces in which Mathews played every character) by heart. Then, having learned Gurney

A stretcher, gurney, litter, or pram is an apparatus used for moving patients who require medical care. A basic type (cot or litter) must be carried by two or more people. A wheeled stretcher (known as a gurney, trolley, bed or cart) is often ...

's system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter. A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors' Commons

Doctors' Commons, also called the College of Civilians, was a society of lawyers practising civil (as opposed to common) law in London, namely ecclesiastical and admiralty law. Like the Inns of Court of the common lawyers, the society had buildi ...

and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years. This education was to inform works such as Nicholas Nickleby, ''Dombey and Son'' and especially ''Bleak House'', whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public and served as a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens's own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to "go to law".

In 1830, Dickens met his first love, Maria Beadnell, thought to have been the model for the character Dora in ''David Copperfield''. Maria's parents disapproved of the courtship and ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris.

Career

Journalism and early novels

In 1832, at the age of 20, Dickens was energetic and increasingly self-confident. He enjoyed mimicry and popular entertainment, lacked a clear, specific sense of what he wanted to become, and yet knew he wanted fame. Drawn to the theatre – he became an early member of the

In 1832, at the age of 20, Dickens was energetic and increasingly self-confident. He enjoyed mimicry and popular entertainment, lacked a clear, specific sense of what he wanted to become, and yet knew he wanted fame. Drawn to the theatre – he became an early member of the Garrick Club

The Garrick Club is a gentlemen's club in the heart of London founded in 1831. It is one of the oldest members' clubs in the world and, since its inception, has catered to members such as Charles Kean, Henry Irving, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, A ...

– he landed an acting audition at Covent Garden, where the manager George Bartley and the actor Charles Kemble were to see him. Dickens prepared meticulously and decided to imitate the comedian Charles Mathews, but ultimately he missed the audition because of a cold. Before another opportunity arose, he had set out on his career as a writer.

In 1833, Dickens submitted his first story, "A Dinner at Poplar Walk", to the London periodical '' Monthly Magazine''.. William Barrow, Dickens's uncle on his mother's side, offered him a job on ''The Mirror of Parliament'' and he worked in the House of Commons for the first time early in 1832. He rented rooms at Furnival's Inn and worked as a political journalist, reporting on Parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

debates, and he travelled across Britain to cover election campaigns for the '' Morning Chronicle''. His journalism, in the form of sketches in periodicals, formed his first collection of pieces, published in 1836: ''Sketches by Boz

''Sketches by "Boz," Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People'' (commonly known as ''Sketches by Boz'') is a collection of short pieces Charles Dickens originally published in various newspapers and other periodicals between 1833 and ...

'' – Boz being a family nickname he employed as a pseudonym for some years.. Dickens apparently adopted it from the nickname 'Moses', which he had given to his youngest brother Augustus Dickens

Augustus Newnham Dickens (10 November 1827 – 4 October 1866) was the youngest brother of English novelist Charles Dickens, and the inspiration for Charles's pen name 'Boz'.

Early life

Augustus Dickens was the son of Elizabeth (''née'' Barro ...

, after a character in Oliver Goldsmith's ''The Vicar of Wakefield

''The Vicar of Wakefield'', subtitled ''A Tale, Supposed to be written by Himself'', is a novel by Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith (1728–1774). It was written from 1761 to 1762 and published in 1766. It was one of the ...

''. When pronounced by anyone with a head cold, "Moses" became "Boses" – later shortened to ''Boz''. Dickens's own name was considered "queer" by a contemporary critic, who wrote in 1849: "Mr Dickens, as if in revenge for his own queer name, does bestow still queerer ones upon his fictitious creations." Dickens contributed to and edited journals throughout his literary career. In January 1835, the ''Morning Chronicle'' launched an evening edition, under the editorship of the ''Chronicle''s music critic, George Hogarth. Hogarth invited him to contribute ''Street Sketches'' and Dickens became a regular visitor to his Fulham house – excited by Hogarth's friendship with Walter Scott (whom Dickens greatly admired) and enjoying the company of Hogarth's three daughters: Georgina, Mary and 19-year-old Catherine.

Dickens made rapid progress both professionally and socially. He began a friendship with

Dickens made rapid progress both professionally and socially. He began a friendship with William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 18053 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in ...

, the author of the highwayman novel '' Rookwood'' (1834), whose bachelor salon in Harrow Road

The Harrow Road is an ancient route in North West London which runs from Paddington in a northwesterly direction towards Harrow. It is also the name given to the immediate surrounding area of Queens Park and Kensal Green, straddling the NW10 ...

had become the meeting place for a set that included Daniel Maclise

Daniel Maclise (25 January 180625 April 1870) was an Irish history painter, literary and portrait painter, and illustrator, who worked for most of his life in London, England.

Early life

Maclise was born in Cork, Ireland, the son of Alexan ...

, Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

, Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton, PC (25 May 180318 January 1873) was an English writer and politician. He served as a Whig member of Parliament from 1831 to 1841 and a Conservative from 1851 to 1866. He was Secret ...

and George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank (27 September 1792 – 1 February 1878) was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reached ...

. All these became his friends and collaborators, with the exception of Disraeli, and he met his first publisher, John Macrone, at the house. The success of ''Sketches by Boz'' led to a proposal from publishers Chapman and Hall

Chapman & Hall is an imprint owned by CRC Press, originally founded as a British publishing house in London in the first half of the 19th century by Edward Chapman and William Hall. Chapman & Hall were publishers for Charles Dickens (from 1840 ...

for Dickens to supply text to match Robert Seymour's engraved illustrations in a monthly letterpress. Seymour committed suicide after the second instalment and Dickens, who wanted to write a connected series of sketches, hired " Phiz" to provide the engravings (which were reduced from four to two per instalment) for the story. The resulting story became '' The Pickwick Papers'' and, although the first few episodes were not successful, the introduction of the Cockney character Sam Weller in the fourth episode (the first to be illustrated by Phiz) marked a sharp climb in its popularity. The final instalment sold 40,000 copies. On the impact of the character, '' The Paris Review'' stated, "arguably the most historic bump in English publishing is the Sam Weller Bump." A publishing phenomenon, John Sutherland called ''The Pickwick Papers'' " e most important single novel of the Victorian era". The unprecedented success led to numerous spin-offs and merchandise ranging from ''Pickwick'' cigars, playing cards, china figurines, Sam Weller puzzles, Weller boot polish and joke books.

On the creation of modern mass culture, Nicholas Dames in '' The Atlantic'' writes, "Literature" is not a big enough category for ''Pickwick''. It defined its own, a new one that we have learned to call "entertainment." In November 1836, Dickens accepted the position of editor of ''Bentley's Miscellany

''Bentley's Miscellany'' was an English literary magazine started by Richard Bentley. It was published between 1836 and 1868.

Contributors

Already a successful publisher of novels, Bentley began the journal in 1836 and invited Charles Dickens ...

'', a position he held for three years, until he fell out with the owner. In 1836, as he finished the last instalments of ''The Pickwick Papers'', he began writing the beginning instalments of '' Oliver Twist'' – writing as many as 90 pages a month – while continuing work on ''Bentley's'' and also writing four plays, the production of which he oversaw. ''Oliver Twist'', published in 1838, became one of Dickens's better known stories and was the first Victorian novel with a child protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

..

On 2 April 1836, after a one-year engagement, and between episodes two and three of ''The Pickwick Papers'', Dickens married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1815–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the '' Evening Chronicle''. They were married in St Luke's Church,

On 2 April 1836, after a one-year engagement, and between episodes two and three of ''The Pickwick Papers'', Dickens married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1815–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the '' Evening Chronicle''. They were married in St Luke's Church, Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament const ...

, London. After a brief honeymoon in Chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

in Kent, the couple returned to lodgings at Furnival's Inn. The first of their ten children, Charles, was born in January 1837 and a few months later the family set up home in Bloomsbury at 48 Doughty Street, London (on which Charles had a three-year lease at £80 a year) from 25 March 1837 until December 1839. Dickens's younger brother Frederick and Catherine's 17-year-old sister Mary Hogarth

Mary Scott Hogarth (26 October 1819 – 7 May 1837) was the sister of Catherine Dickens ( Hogarth) and the sister-in-law of Charles Dickens. Hogarth first met Charles Dickens at age 14, and after Dickens married Hogarth's sister Catherine, Ma ...

moved in with them. Dickens became very attached to Mary, and she died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837. Unusually for Dickens, as a consequence of his shock, he stopped working, and he and Catherine stayed at a little farm on Hampstead Heath for a fortnight. Dickens idealised Mary; the character he fashioned after her, Rose Maylie, he found he could not now kill, as he had planned, in his fiction, and, according to Ackroyd, he drew on memories of her for his later descriptions of Little Nell and Florence Dombey. His grief was so great that he was unable to meet the deadline for the June instalment of ''The Pickwick Papers'' and had to cancel the ''Oliver Twist'' instalment that month as well. The time in Hampstead was the occasion for a growing bond between Dickens and John Forster to develop; Forster soon became his unofficial business manager and the first to read his work.

His success as a novelist continued. The young Queen Victoria read both ''Oliver Twist'' and ''The Pickwick Papers'', staying up until midnight to discuss them. '' Nicholas Nickleby'' (1838–39), ''

His success as a novelist continued. The young Queen Victoria read both ''Oliver Twist'' and ''The Pickwick Papers'', staying up until midnight to discuss them. '' Nicholas Nickleby'' (1838–39), ''The Old Curiosity Shop

''The Old Curiosity Shop'' is one of two novels (the other being ''Barnaby Rudge'') which Charles Dickens published along with short stories in his weekly serial ''Master Humphrey's Clock'', from 1840 to 1841. It was so popular that New York r ...

'' (1840–41) and, finally, his first historical novel, '' Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty'', as part of the '' Master Humphrey's Clock'' series (1840–41), were all published in monthly instalments before being made into books.

In the midst of all his activity during this period, there was discontent with his publishers and John Macrone was bought off, while Richard Bentley

Richard Bentley FRS (; 27 January 1662 – 14 July 1742) was an English classical scholar, critic, and theologian. Considered the "founder of historical philology", Bentley is widely credited with establishing the English school of Hellen ...

signed over all his rights in ''Oliver Twist''. Other signs of a certain restlessness and discontent emerged; in Broadstairs

Broadstairs is a coastal town on the Isle of Thanet in the Thanet district of east Kent, England, about east of London. It is part of the civil parish of Broadstairs and St Peter's, which includes St Peter's, and had a population in 2011 of ...

he flirted with Eleanor Picken, the young fiancée of his solicitor's best friend and one night grabbed her and ran with her down to the sea. He declared they were both to drown there in the "sad sea waves". She finally got free, and afterwards kept her distance. In June 1841, he precipitously set out on a two-month tour of Scotland and then, in September 1841, telegraphed Forster that he had decided to go to America. ''Master Humphrey's Clock'' was shut down, though Dickens was still keen on the idea of the weekly magazine, a form he liked, an appreciation that had begun with his childhood reading of the 18th-century magazines ''Tatler

''Tatler'' is a British magazine published by Condé Nast Publications focusing on fashion and lifestyle, as well as coverage of high society and politics. It is targeted towards the British upper-middle class and upper class, and those interes ...

'' and ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''Th ...

''.

Dickens was perturbed by the return to power of the Tories, whom he described as "people whom, politically, I despise and abhor." He had been tempted to stand for the Liberals in Reading, but decided against it due to financial straits. He wrote three anti-Tory verse satires ("The Fine Old English Gentleman", "The Quack Doctor's Proclamation", and "Subjects for Painters") which were published in '' The Examiner''.

First visit to the United States

On 22 January 1842, Dickens and his wife arrived inBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- most p ...

, Massachusetts, aboard the RMS ''Britannia'' during their first trip to the United States and Canada. At this time Georgina Hogarth

Georgina Hogarth (22 January 1827 – 19 April 1917) was the sister-in-law, housekeeper, and adviser of English novelist Charles Dickens and the editor of three volumes of his collected letters after his death.

Biography

'Georgy' Hogarth was o ...

, another sister of Catherine, joined the Dickens household, now living at Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone to care for the young family they had left behind. She remained with them as housekeeper, organiser, adviser and friend until Dickens's death in 1870. Dickens modelled the character of Agnes Wickfield after Georgina and Mary.

He described his impressions in a travelogue, '' American Notes for General Circulation''. In ''Notes'', Dickens includes a powerful condemnation of slavery which he had attacked as early as ''The Pickwick Papers'', correlating the emancipation of the poor in England with the abolition of slavery abroad citing newspaper accounts of runaway slaves disfigured by their masters. In spite of the abolitionist sentiments gleaned from his trip to America, some modern commentators have pointed out inconsistencies in Dickens's views on racial inequality. For instance, he has been criticized for his subsequent acquiescence in Governor Eyre's harsh crackdown during the 1860s Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica and his failure to join other British progressives in condemning it. From Richmond, Virginia, Dickens returned to Washington, D.C., and started a trek westward, with brief pauses in Cincinnati and Louisville, to St. Louis, Missouri. While there, he expressed a desire to see an American prairie before returning east. A group of 13 men then set out with Dickens to visit Looking Glass Prairie, a trip 30 miles into Illinois.

During his American visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures, raising the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his work in America. He persuaded a group of 25 writers, headed by

He described his impressions in a travelogue, '' American Notes for General Circulation''. In ''Notes'', Dickens includes a powerful condemnation of slavery which he had attacked as early as ''The Pickwick Papers'', correlating the emancipation of the poor in England with the abolition of slavery abroad citing newspaper accounts of runaway slaves disfigured by their masters. In spite of the abolitionist sentiments gleaned from his trip to America, some modern commentators have pointed out inconsistencies in Dickens's views on racial inequality. For instance, he has been criticized for his subsequent acquiescence in Governor Eyre's harsh crackdown during the 1860s Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica and his failure to join other British progressives in condemning it. From Richmond, Virginia, Dickens returned to Washington, D.C., and started a trek westward, with brief pauses in Cincinnati and Louisville, to St. Louis, Missouri. While there, he expressed a desire to see an American prairie before returning east. A group of 13 men then set out with Dickens to visit Looking Glass Prairie, a trip 30 miles into Illinois.

During his American visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures, raising the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his work in America. He persuaded a group of 25 writers, headed by Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories " Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legen ...

, to sign a petition for him to take to Congress, but the press were generally hostile to this, saying that he should be grateful for his popularity and that it was mercenary to complain about his work being pirated.

The popularity he gained caused a shift in his self-perception according to critic Kate Flint, who writes that he "found himself a cultural commodity, and its circulation had passed out his control", causing him to become interested in and delve into themes of public and personal personas in the next novels.. She writes that he assumed a role of "influential commentator", publicly and in his fiction, evident in his next few books. His trip to the U.S. ended with a trip to Canada – Niagara Falls, Toronto, Kingston and Montreal – where he appeared on stage in light comedies.

Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his Christmas stories, ''

Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his Christmas stories, ''A Christmas Carol

''A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas'', commonly known as ''A Christmas Carol'', is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. ''A Christmas Ca ...

'', written in 1843, which was followed by ''The Chimes

''The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In'', commonly referred to as ''The Chimes'', is a novella written by Charles Dickens and first published in 1844, one year after ''A Christmas Carol''. It is th ...

'' in 1844 and ''The Cricket on the Hearth

''The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home'' is a novella by Charles Dickens, published by Bradbury and Evans, and released 20 December 1845 with illustrations by Daniel Maclise, John Leech, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield and Edwin ...

'' in 1845. Of these, ''A Christmas Carol'' was most popular and, tapping into an old tradition, did much to promote a renewed enthusiasm for the joys of Christmas in Britain and America. The seeds for the story became planted in Dickens's mind during a trip to Manchester to witness the conditions of the manufacturing workers there. This, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged School, caused Dickens to resolve to "strike a sledge hammer blow" for the poor. As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest, Dickens became engrossed in the book. He later wrote that as the tale unfolded he "wept and laughed, and wept again" as he "walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed".

After living briefly in Italy (1844), Dickens travelled to Switzerland (1846), where he began work on '' Dombey and Son'' (1846–48). This and '' David Copperfield'' (1849–50) mark a significant artistic break in Dickens's career as his novels became more serious in theme and more carefully planned than his early works.

At about this time, he was made aware of a large embezzlement at the firm where his brother, Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, worked (John Chapman & Co). It had been carried out by Thomas Powell, a clerk, who was on friendly terms with Dickens and who had acted as mentor to Augustus when he started work. Powell was also an author and poet and knew many of the famous writers of the day. After further fraudulent activities, Powell fled to New York and published a book called ''The Living Authors of England'' with a chapter on Charles Dickens, who was not amused by what Powell had written. One item that seemed to have annoyed him was the assertion that he had based the character of Paul Dombey ('' Dombey and Son'') on Thomas Chapman, one of the principal partners at John Chapman & Co. Dickens immediately sent a letter to Lewis Gaylord Clark

Lewis Gaylord Clark (October 5, 1808 – November 3, 1873) was an American magazine editor and publisher.

Biography

Clark was born in Otisco, New York in 1808.Miller, Perry. ''The Raven and the Whale: The War of Words and Wits in the Era of Poe ...

, editor of the New York literary magazine '' The Knickerbocker'', saying that Powell was a forger and thief. Clark published the letter in the ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' and several other papers picked up on the story. Powell began proceedings to sue these publications and Clark was arrested. Dickens, realising that he had acted in haste, contacted John Chapman & Co to seek written confirmation of Powell's guilt. Dickens did receive a reply confirming Powell's embezzlement, but once the directors realised this information might have to be produced in court, they refused to make further disclosures. Owing to the difficulties of providing evidence in America to support his accusations, Dickens eventually made a private settlement with Powell out of court.

Philanthropy

Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens in May 1846 about setting up a home for the redemption of fallen women of the working class. Coutts envisioned a home that would replace the punitive regimes of existing institutions with a reformative environment conducive to education and proficiency in domestic household chores. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named

Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens in May 1846 about setting up a home for the redemption of fallen women of the working class. Coutts envisioned a home that would replace the punitive regimes of existing institutions with a reformative environment conducive to education and proficiency in domestic household chores. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named Urania Cottage

Georgiana Morson was a British social reformer. She served as a matron for Urania Cottage, a house for what were then called " fallen women" ( prostitutes) founded by Charles Dickens and Angela Burdett-Coutts

Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts, ...

, in the Lime Grove area of Shepherd's Bush, which he managed for ten years, setting the house rules, reviewing the accounts and interviewing prospective residents. Emigration and marriage were central to Dickens's agenda for the women on leaving Urania Cottage, from which it is estimated that about 100 women graduated between 1847 and 1859.

Religious views

As a young man, Dickens expressed a distaste for certain aspects of organised religion. In 1836, in a pamphlet titled ''Sunday Under Three Heads'', he defended the people's right to pleasure, opposing a plan to prohibit games on Sundays. "Look into your churches – diminished congregations and scanty attendance. People have grown sullen and obstinate, and are becoming disgusted with the faith which condemns them to such a day as this, once in every seven. They display their feeling by staying away rom church Turn into the streets n a Sundayand mark the rigid gloom that reigns over everything around." Dickens honoured the figure of Jesus Christ. He is regarded as a professing Christian. His son, Henry Fielding Dickens, described him as someone who "possessed deep religious convictions". In the early 1840s, he had shown an interest in Unitarian Christianity and Robert Browning remarked that "Mr Dickens is an enlightened Unitarian." Professor Gary Colledge has written that he "never strayed from his attachment to popular lay

Dickens honoured the figure of Jesus Christ. He is regarded as a professing Christian. His son, Henry Fielding Dickens, described him as someone who "possessed deep religious convictions". In the early 1840s, he had shown an interest in Unitarian Christianity and Robert Browning remarked that "Mr Dickens is an enlightened Unitarian." Professor Gary Colledge has written that he "never strayed from his attachment to popular lay Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

". Dickens authored a work called ''The Life of Our Lord

''The Life of Our Lord'' is a book about the life of Jesus of Nazareth written by English novelist Charles Dickens, for his young children, between 1846 and 1849, at about the time that he was writing ''David Copperfield''. ''The Life of Our Lord' ...

'' (1846), a book about the life of Christ, written with the purpose of sharing his faith with his children and family. In a scene from ''David Copperfield'', Dickens echoed Geoffrey Chaucer's use of Luke 23:34 from '' Troilus and Criseyde'' (Dickens held a copy in his library), with G. K. Chesterton writing, "among the great canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean "according to the canon" the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, "canonical exampl ...

English authors, Chaucer and Dickens have the most in common."

Dickens disapproved of Roman Catholicism and 19th-century evangelicalism, seeing both as extremes of Christianity and likely to limit personal expression, and was critical of what he saw as the hypocrisy of religious institutions and philosophies like spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) b ...