Diocletian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

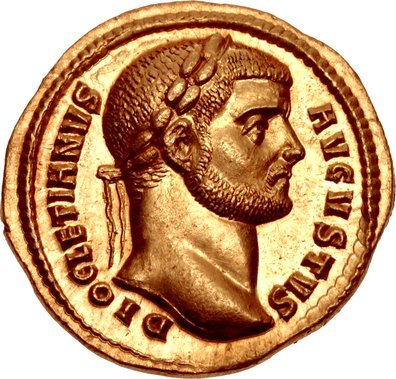

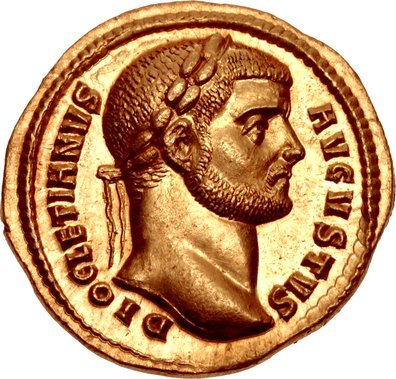

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles to a family of low status in the

Diocletian was born in Dalmatia, probably at or near the town of

Diocletian was born in Dalmatia, probably at or near the town of

After his accession, Diocletian and Lucius Caesonius Bassus were named as consuls and assumed the ''

After his accession, Diocletian and Lucius Caesonius Bassus were named as consuls and assumed the ''

Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the

Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the  Nevertheless, if Diocletian ever did enter Rome shortly after his accession, he did not stay long; he is attested back in the Balkans by 2 November 285, on campaign against the

Nevertheless, if Diocletian ever did enter Rome shortly after his accession, he did not stay long; he is attested back in the Balkans by 2 November 285, on campaign against the

The assassinations of Aurelian and Probus demonstrated that sole rulership was dangerous to the stability of the empire. Conflict boiled in every province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at

The assassinations of Aurelian and Probus demonstrated that sole rulership was dangerous to the stability of the empire. Conflict boiled in every province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at

Maximian realized that he could not immediately suppress the rogue commander, so in 287 he campaigned solely against tribes beyond the

Maximian realized that he could not immediately suppress the rogue commander, so in 287 he campaigned solely against tribes beyond the

Some time after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against

Some time after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 travelling with Galerius from Sirmium (

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 travelling with Galerius from Sirmium (

In 294,

In 294,  Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent collected from the empire's Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. It is unclear if Diocletian was present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria. Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius's force, to Narseh's disadvantage; the rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius continued moving down the Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman territory along the Euphrates.

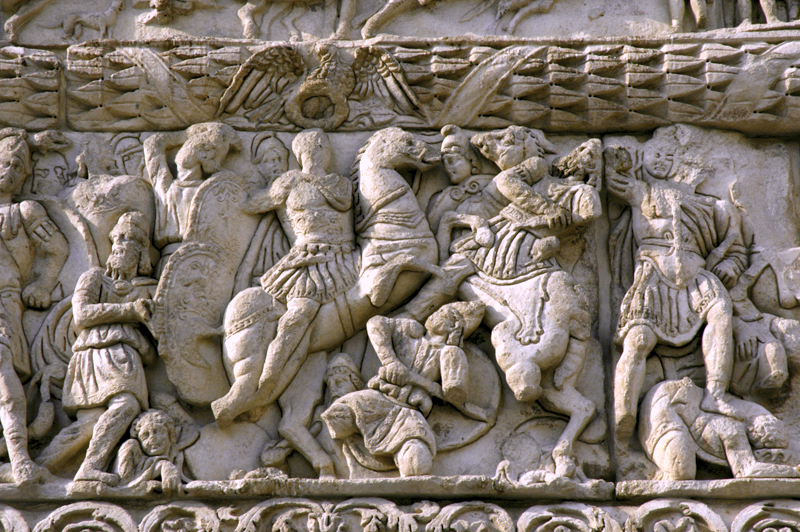

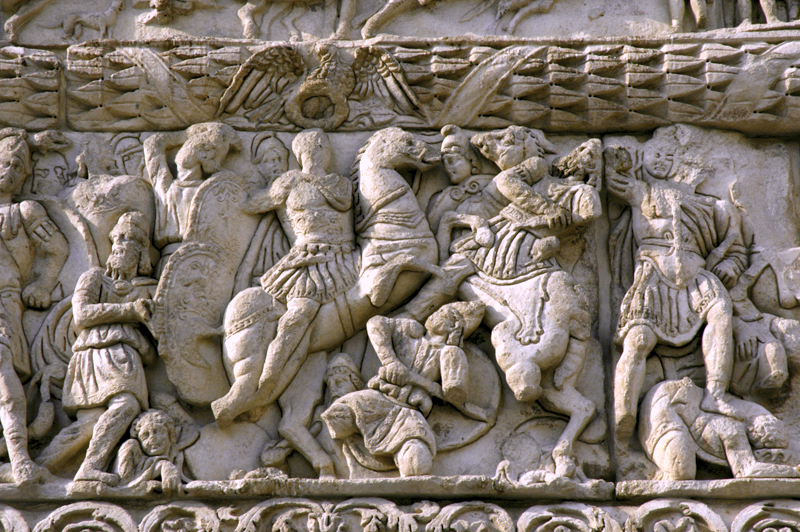

Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent collected from the empire's Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. It is unclear if Diocletian was present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria. Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius's force, to Narseh's disadvantage; the rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius continued moving down the Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman territory along the Euphrates.

Diocletian retired to his homeland, Dalmatia. He moved into the expansive

Diocletian retired to his homeland, Dalmatia. He moved into the expansive

As with most emperors, much of Diocletian's daily routine rotated around legal affairs – responding to appeals and petitions, and delivering decisions on disputed matters. Rescripts, authoritative interpretations issued by the emperor in response to demands from disputants in both public and private cases, were a common duty of second- and third-century emperors. In the "nomadic" imperial courts of the later Empire, one can track the progress of the imperial retinue through the locations from whence particular rescripts were issued – the presence of the Emperor was what allowed the system to function. Whenever the imperial court would settle in one of the capitals, there was a glut in petitions, as in late 294 in Nicomedia, where Diocletian kept winter quarters.

Admittedly, Diocletian's praetorian prefects – Afranius Hannibalianus, Julius Asclepiodotus, and

As with most emperors, much of Diocletian's daily routine rotated around legal affairs – responding to appeals and petitions, and delivering decisions on disputed matters. Rescripts, authoritative interpretations issued by the emperor in response to demands from disputants in both public and private cases, were a common duty of second- and third-century emperors. In the "nomadic" imperial courts of the later Empire, one can track the progress of the imperial retinue through the locations from whence particular rescripts were issued – the presence of the Emperor was what allowed the system to function. Whenever the imperial court would settle in one of the capitals, there was a glut in petitions, as in late 294 in Nicomedia, where Diocletian kept winter quarters.

Admittedly, Diocletian's praetorian prefects – Afranius Hannibalianus, Julius Asclepiodotus, and

Aurelian's attempt to reform the currency had failed; the denarius was dead. Diocletian restored the three-metal coinage and issued better quality pieces. The new system consisted of five coins: the ''aureus''/''

Aurelian's attempt to reform the currency had failed; the denarius was dead. Diocletian restored the three-metal coinage and issued better quality pieces. The new system consisted of five coins: the ''aureus''/''

The historian

The historian "The Legends of King Diocletian" (in Hebrew)

Rabbi Meir Ba'al Ha'nes Synagogue, Tel Aviv.

translation

*

* *

from the ''

12 Byzantine Rulers

, by

02. The Crisis of the Third Century and the Diocletianic Reforms

Professor Freedman on Yalecourses

Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia

By Robert Adam, 1764. Plates made available by the

Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of Dalmatia. Diocles rose through the ranks of the military early in his career, eventually becoming a cavalry commander for the army of Emperor Carus. After the deaths of Carus and his son Numerian on a campaign in Persia, Diocles was proclaimed emperor by the troops, taking the name Diocletianus. The title was also claimed by Carus's surviving son, Carinus, but Diocletian defeated him in the Battle of the Margus

The Battle of the Margus or Battle of Margum was fought in July 285 for control of the Roman Empire between the armies of Diocletian and Carinus in the valley of the Margus River (today Great Morava) in Moesia (present day Serbia), probably near ...

.

Diocletian's reign stabilized the empire and ended the Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensio ...

. He appointed fellow officer Maximian as ''Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

'', co-emperor, in 286. Diocletian reigned in the Eastern Empire, and Maximian reigned in the Western Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

. Diocletian delegated further on 1 March 293, appointing Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

and Constantius as junior colleagues (each with the title ''Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

''), under himself and Maximian respectively. Under the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

, or "rule of four", each tetrach would rule over a quarter-division of the empire. Diocletian secured the empire's borders and purged it of all threats to his power. He defeated the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

and Carpi

Carpi may refer to:

Places

* Carpi, Emilia-Romagna, a large town in the province of Modena, central Italy

* Carpi (Africa), a city and former diocese of Roman Africa, now a Latin Catholic titular bishopric

People

* Carpi (people), an ancie ...

during several campaigns between 285 and 299, the Alamanni in 288, and usurpers in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

between 297 and 298. Galerius, aided by Diocletian, campaigned successfully against Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

, the empire's traditional enemy. In 299, he sacked their capital, Ctesiphon. Diocletian led the subsequent negotiations and achieved a lasting and favorable peace.

Diocletian separated and enlarged the empire's civil and military services and reorganized the empire's provincial divisions, establishing the largest and most bureaucratic

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

government in the history of the empire. He established new administrative centres in Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; el, Νικομήδεια, ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocleti ...

, Mediolanum

Mediolanum, the ancient city where Milan now stands, was originally an Insubrian city, but afterwards became an important Roman city in northern Italy. The city was settled by the Insubres around 600 BC, conquered by the Romans in 222 BC, and ...

, Sirmium

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous provice of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyrian ...

, and Trevorum, closer to the empire's frontiers than the traditional capital at Rome. Building on third-century trends towards absolutism, he styled himself an autocrat, elevating himself above the empire's masses with imposing forms of court ceremonies and architecture. Bureaucratic and military growth, constant campaigning, and construction projects increased the state's expenditures and necessitated a comprehensive tax reform. From at least 297 on, imperial taxation was standardized, made more equitable, and levied at generally higher rates.

Not all of Diocletian's plans were successful: the Edict on Maximum Prices

The Edict on Maximum Prices (Latin: ''Edictum de Pretiis Rerum Venalium'', "Edict Concerning the Sale Price of Goods"; also known as the Edict on Prices or the Edict of Diocletian) was issued in 301 AD by Diocletian. The document denounces mon ...

(301), his attempt to curb inflation via price controls, was counterproductive and quickly ignored. Although effective while he ruled, Diocletian's tetrarchic system collapsed after his abdication under the competing dynastic claims of Maxentius and Constantine, sons of Maximian and Constantius respectively. The Diocletianic Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rig ...

(303–312), the empire's last, largest, and bloodiest official persecution of Christianity, failed to eliminate Christianity in the empire. After 324, Christianity became the empire's preferred religion under Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

. Despite these failures and challenges, Diocletian's reforms fundamentally changed the structure of Roman imperial government and helped stabilize the empire economically and militarily, enabling the empire to remain essentially intact for another 150 years despite being near the brink of collapse in Diocletian's youth. Weakened by illness, Diocletian left the imperial office on 1 May 305, becoming the first Roman emperor to abdicate the position voluntarily. He lived out his retirement in his palace on the Dalmatian coast, tending to his vegetable gardens. His palace eventually became the core of the modern-day city of Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertai ...

in Croatia.

Early life

Diocletian was born in Dalmatia, probably at or near the town of

Diocletian was born in Dalmatia, probably at or near the town of Salona

Salona ( grc, Σάλωνα) was an ancient city and the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia. Salona is located in the modern town of Solin, next to Split, in Croatia.

Salona was founded in the 3rd century BC and was mostly destroyed in ...

(modern Solin

Solin (Latin and it, Salona; grc, Σαλώνα ) is a town in Dalmatia, Croatia. It is situated right northeast of Split, on the Adriatic Sea and the river Jadro.

Solin developed on the location of ancient city of ''Salona'', which was the ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

), to which he retired later in life. His name at birth was Diocles (in full, Gaius Valerius Diocles), possibly derived from Dioclea, the name of both his mother and her supposed place of birth

The place of birth (POB) or birthplace is the place where a person was born. This place is often used in legal documents, together with name and date of birth, to uniquely identify a person. Practice regarding whether this place should be a co ...

. Diocletian's official birthday was recorded at 22 December, and his year of birth has been estimated at between 242 and 245 based on a statement that he was aged 68 at death. His parents were of low status; Eutropius records "that he is said by most writers to have been the son of a scribe, but by some to have been a freedman of a senator called Anulinus." The first forty years of his life are mostly obscure. Diocletian was considered an Illyricianus ('' Illyrian emperor'') who had been schooled and promoted by Aurelian. The Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

chronicler Joannes Zonaras states that he was ''Dux

''Dux'' (; plural: ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, '' ...

Moesiae'', a commander of forces on the lower Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

. The often-unreliable ''Historia Augusta

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the sim ...

'' states that he served in Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, but this account is not corroborated by other sources and is ignored by modern historians of the period. The first time Diocletian's whereabouts are accurately established was in 282 when the Emperor Carus made him commander of the ''Protectores domestici

The origins of the word ''domesticus'' can be traced to the late 3rd century of the Late Roman army. They often held high ranks in various fields, whether it was the servants of a noble house on the civilian side, or a high-ranking military po ...

'', the elite cavalry force directly attached to the Imperial household. This post earned him the honor of a consulship in 283. As such, he took part in Carus's subsequent Persian campaign.

Death of Numerian

Carus's death, amid a successful war with Persia and in mysterious circumstances – he was believed to have been struck by lightning or killed by Persian soldiers – left his sons Numerian and Carinus as the new ''Augusti''. Carinus quickly made his way to Rome from his post in Gaul as imperial commissioner and arrived there by January 284, becoming legitimate Emperor in the West. Numerian lingered in the East. The Roman withdrawal from Persia was orderly and unopposed. TheSassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

king Bahram II

Bahram II (also spelled Wahram II or Warahran II; pal, 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭) was the fifth Sasanian King of Kings (''shahanshah'') of Iran, from 274 to 293. He was the son and successor of Bahram I (). Bahram II, while still in his teens, ...

could not field an army against them as he was still struggling to establish his authority. By March 284, Numerian had only reached Emesa (Homs) in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

; by November, only Asia Minor. In Emesa he was apparently still alive and in good health: he issued the only extant rescript

In legal terminology, a rescript is a document that is issued not on the initiative of the author, but in response (it literally means 'written back') to a specific demand made by its addressee. It does not apply to more general legislation.

Over ...

in his name there, but after he left the city, his staff, including the prefect (Numerian's father-in-law, and as such the dominant influence in the Emperor's entourage) Aper Aper may refer to:

People

* Aper (grammarian), 1st century Greek grammarian

* Marcus Aper, 1st century Roman orator

* Trosius Aper, 2nd century Roman grammarian and Latin tutor to Marcus Aurelius

* Gaius Septimius Severus Aper (ca. 175–211/2 ...

, reported that he suffered from an inflammation of the eyes. He traveled in a closed coach from then on. When the army reached Bithynia

Bithynia (; Koine Greek: , ''Bithynía'') was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Pa ...

, some of the soldiers smelled an odor emanating from the coach. They opened its curtains and inside they found Numerian dead. Both Eutropius and Aurelius Victor

Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. 320 – c. 390) was a historian and politician of the Roman Empire. Victor was the author of a short history of imperial Rome, entitled ''De Caesaribus'' and covering the period from Augustus to Constantius II. The work w ...

describe Numerian's death as an assassination.

Aper officially broke the news in Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; el, Νικομήδεια, ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocleti ...

(İzmit

İzmit () is a district and the central district of Kocaeli province, Turkey. It is located at the Gulf of İzmit in the Sea of Marmara, about east of Istanbul, on the northwestern part of Anatolia.

As of the last 31/12/2019 estimation, the c ...

) in November. Numerianus' generals and tribunes called a council for the succession, and chose Diocles as Emperor, in spite of Aper's attempts to garner support. On 20 November 284, the army of the east gathered on a hill outside Nicomedia. The army unanimously saluted Diocles as their new ''Augustus'', and he accepted the purple imperial vestments. He raised his sword to the light of the sun and swore an oath disclaiming responsibility for Numerian's death. He asserted that Aper had killed Numerian and concealed it. In full view of the army, Diocles drew his sword and killed Aper. According to the ''Historia Augusta'', he quoted from Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

while doing so. Soon after Aper's death, Diocles changed his name to the more Latinate "Diocletianus" – in full, Gaius Valerius Diocletianus.

Conflict with Carinus

fasces

Fasces ( ; ; a ''plurale tantum'', from the Latin word ''fascis'', meaning "bundle"; it, fascio littorio) is a bound bundle of wooden rods, sometimes including an axe (occasionally two axes) with its blade emerging. The fasces is an Italian symbo ...

'' in place of Carinus and Numerianus. Bassus was a member of a senatorial

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

family from Campania

Campania (, also , , , ) is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islands and the i ...

, a former consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

and proconsul of Africa, chosen by Probus for signal distinction. He was skilled in areas of government where Diocletian presumably had no experience. Diocletian's elevation of Bassus as consul symbolized his rejection of Carinus' government in Rome, his refusal to accept second-tier status to any other emperor, and his willingness to continue the long-standing collaboration between the empire's senatorial and military aristocracies. It also tied his success to that of the Senate, whose support he would need in his advance on Rome.

Diocletian was not the only challenger to Carinus' rule; the usurper Julianus, Carinus' ''corrector Venetiae'', took control of northern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

after Diocletian's accession. Julianus minted coins from the mint at Siscia (Sisak

Sisak (; hu, Sziszek ; also known by other alternative names) is a city in central Croatia, spanning the confluence of the Kupa, Sava and Odra rivers, southeast of the Croatian capital Zagreb, and is usually considered to be where the Posavin ...

, Croatia) declaring himself emperor and promising freedom. It was all good publicity for Diocletian, and it aided in his portrayal of Carinus as a cruel and oppressive tyrant. Julianus' forces were weak, however, and were handily dispersed when Carinus' armies moved from Britain to northern Italy. As leader of the united East, Diocletian was clearly the greater threat. Over the winter of 284–85, Diocletian advanced west across the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. In the spring, some time before the end of May, his armies met Carinus' across the river Margus (Great Morava

The Great Morava ( sr, Велика Морава, Velika Morava, ) is the final section of the Morava ( sr-Cyrl, Морава), a major river system in Serbia.

Etymology

According to Predrag Komatina from the Institute for Byzantine Studies ...

) in Moesia. In modern accounts, the site has been located between the Mons Aureus (Seone, west of Smederevo

Smederevo ( sr-Cyrl, Смедерево, ) is a city and the administrative center of the Podunavlje District in eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube, about downstream of the Serbian capital, Belgrade.

According to ...

) and Viminacium

Viminacium () or ''Viminatium'', was a major city (provincial capital) and military camp of the Roman province of Moesia (today's Serbia), and the capital of '' Moesia Superior'' (hence once a metropolitan archbishopric, now a Latin titular see) ...

, near modern Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

, Serbia.

Despite having the stronger, more powerful army, Carinus held the weaker position. His rule was unpopular, and it was later alleged that he had mistreated the Senate and seduced his officers' wives. It is possible that Flavius Constantius, the governor of Dalmatia and Diocletian's associate in the household guard, had already defected to Diocletian in the early spring. When the Battle of the Margus

The Battle of the Margus or Battle of Margum was fought in July 285 for control of the Roman Empire between the armies of Diocletian and Carinus in the valley of the Margus River (today Great Morava) in Moesia (present day Serbia), probably near ...

began, Carinus' prefect Aristobulus Aristobulus or Aristoboulos may refer to:

*Aristobulus I (died 103 BC), king of the Hebrew Hasmonean Dynasty, 104–103 BC

*Aristobulus II (died 49 BC), king of Judea from the Hasmonean Dynasty, 67–63 BC

*Aristobulus III of Judea (53 BC–36 BC), ...

also defected. In the course of the battle, Carinus was killed by his own men. Following Diocletian's victory, both the western and the eastern armies acclaimed him as Emperor. Diocletian exacted an oath of allegiance from the defeated army and departed for Italy.

Early rule

Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the

Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the Quadi

The Quadi were a Germanic

*

*

*

people who lived approximately in the area of modern Moravia in the time of the Roman Empire. The only surviving contemporary reports about the Germanic tribe are those of the Romans, whose empire had its bord ...

and Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

Origin

...

immediately after the Battle of the Margus. He eventually made his way to northern Italy and made an imperial government, but it is not known whether he visited the city of Rome at this time. There is a contemporary issue of coins suggestive of an imperial '' adventus'' (arrival) for the city, but some modern historians state that Diocletian avoided the city, and that he did so on principle, as the city and its Senate were no longer politically relevant to the affairs of the empire and needed to be taught as much. Diocletian dated his reign from his elevation by the army, not the date of his ratification by the Senate, following the practice established by Carus, who had declared the Senate's ratification a useless formality. However, Diocletian was to offer proof of his deference towards the Senate by retaining Aristobulus as ordinary consul and colleague for 285 (one of the few instances during the Late Empire in which an emperor admitted a ''privatus

In Roman law, the Latin adjective ''privatus'' makes a legal distinction between that which is "private" and that which is ''publicus'', "public" in the sense of pertaining to the Roman people (''populus Romanus'').

Used as a substantive, the ...

'' as his colleague) and by creating senior senators Vettius Aquilinus and Junius Maximus ordinary consuls for the following year – for Maximus, it was his second consulship.

Nevertheless, if Diocletian ever did enter Rome shortly after his accession, he did not stay long; he is attested back in the Balkans by 2 November 285, on campaign against the

Nevertheless, if Diocletian ever did enter Rome shortly after his accession, he did not stay long; he is attested back in the Balkans by 2 November 285, on campaign against the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

.

Diocletian replaced the prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

of Rome with his consular colleague Bassus. Most officials who had served under Carinus, however, retained their offices under Diocletian. In an act of ''clementia'' denoted by the epitomator of Aurelius Victor

Sextus Aurelius Victor (c. 320 – c. 390) was a historian and politician of the Roman Empire. Victor was the author of a short history of imperial Rome, entitled ''De Caesaribus'' and covering the period from Augustus to Constantius II. The work w ...

as unusual, Diocletian did not kill or depose Carinus's traitorous praetorian prefect and consul Aristobulus Aristobulus or Aristoboulos may refer to:

*Aristobulus I (died 103 BC), king of the Hebrew Hasmonean Dynasty, 104–103 BC

*Aristobulus II (died 49 BC), king of Judea from the Hasmonean Dynasty, 67–63 BC

*Aristobulus III of Judea (53 BC–36 BC), ...

, but confirmed him in both roles. He later gave him the proconsulate of Africa and the post of urban prefect for 295. The other figures who retained their offices might have also betrayed Carinus.

Maximian made Caesar

Mediolanum

Mediolanum, the ancient city where Milan now stands, was originally an Insubrian city, but afterwards became an important Roman city in northern Italy. The city was settled by the Insubres around 600 BC, conquered by the Romans in 222 BC, and ...

(Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

), Diocletian raised his fellow-officer Maximian to the office of ''Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

'', making him his effective co-ruler.

The concept of dual rulership was not new to the Roman Empire. Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, the first emperor, had nominally shared power with his colleagues, and a formal office of co-emperor (co-''Augustus'') had existed from Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

onward. Most recently, Emperor Carus and his sons had ruled together, albeit unsuccessfully. Diocletian was in a less comfortable position than most of his predecessors, as he had a daughter, Valeria, but no sons. His co-ruler had to be from outside his family, raising the question of trust. Some historians state that Diocletian adopted Maximian as his ''filius Augusti'', his "Augustan son", upon his appointment to the throne, following the precedent of some previous Emperors. This argument has not been universally accepted. Diocletian and Maximian added each other '' nomina'' (their family name

In some cultures, a surname, family name, or last name is the portion of one's personal name that indicates one's family, tribe or community.

Practices vary by culture. The family name may be placed at either the start of a person's full name ...

, "Valerius" and "Aurelius", respectively) to their own, thus creating an artificial family link and becoming part of the "Aurelius Valerius" family.

The relationship between Diocletian and Maximian was quickly couched in religious terms. Around 287 Diocletian assumed the title ''Iovius'', and Maximian assumed the title ''Herculius''. The titles were probably meant to convey certain characteristics of their associated leaders. Diocletian, in Jovian

Jovian is the adjectival form of Jupiter and may refer to:

* Jovian (emperor) (Flavius Iovianus Augustus), Roman emperor (363–364 AD)

* Jovians and Herculians, Roman imperial guard corps

* Jovian (lemur), a Coquerel's sifaka known for ''Zoboomafo ...

style, would take on the dominating roles of planning and commanding; Maximian, in Herculian mode, would act as Jupiter's hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or Physical strength, strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ...

ic subordinate. For all their religious connotations, the emperors were not "gods" in the tradition of the Imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may ...

– although they may have been hailed as such in Imperial panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

s. Instead, they were seen as the gods' representatives, effecting their will on earth. The shift from military acclamation to divine sanctification took the power to appoint emperors away from the army. Religious legitimization elevated Diocletian and Maximian above potential rivals in a way military power and dynastic claims could not.

Conflict with Sarmatia and Persia

After his acclamation, Maximian was dispatched to fight the rebel Bagaudae, insurgent peasants of Gaul. Diocletian returned to the East, progressing slowly. By 2 November, he had only reached Civitas Iovia (Botivo, nearPtuj

Ptuj (; german: Pettau, ; la, Poetovium/Poetovio) is a town in northeastern Slovenia that is the seat of the Municipality of Ptuj. Ptuj, the oldest recorded city in Slovenia, has been inhabited since the late Stone Age and developed from a Roman ...

, Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

). In the Balkans during the autumn of 285, he encountered a tribe of Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

who demanded assistance. The Sarmatians requested that Diocletian either help them recover their lost lands or grant them pasturage rights within the empire. Diocletian refused and fought a battle with them, but was unable to secure a complete victory. The nomadic pressures of the European Plain

The European Plain or Great European Plain is a plain in Europe and is a major feature of one of four major topographical units of Europe - the ''Central and Interior Lowlands''.

remained and could not be solved by a single war; soon the Sarmatians would have to be fought again.

Diocletian wintered in Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; el, Νικομήδεια, ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocleti ...

. There may have been a revolt in the eastern provinces at this time, as he brought settlers from Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

to populate emptied farmlands in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

. He visited Syria Palaestina

Syria Palaestina (literally, "Palestinian Syria";Trevor Bryce, 2009, ''The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia''Roland de Vaux, 1978, ''The Early History of Israel'', Page 2: "After the revolt of Bar Cochba in 135 ...

the following spring, His stay in the East saw diplomatic success in the conflict with Persia: in 287, Bahram II

Bahram II (also spelled Wahram II or Warahran II; pal, 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭) was the fifth Sasanian King of Kings (''shahanshah'') of Iran, from 274 to 293. He was the son and successor of Bahram I (). Bahram II, while still in his teens, ...

granted him precious gifts, declared open friendship with the Empire, and invited Diocletian to visit him. Roman sources insist that the act was entirely voluntary.

Around the same time, perhaps in 287, Persia relinquished claims on Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

and recognized Roman authority over territory to the west and south of the Tigris. The western portion of Armenia was incorporated into the empire and made a province. Tiridates III, the Arsacid

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conqueri ...

claimant to the Armenian throne and a Roman client, had been disinherited and forced to take refuge in the empire after the Persian conquest of 252–53. In 287, he returned to lay claim to the eastern half of his ancestral domain and encountered no opposition. Bahram II's gifts were widely recognized as symbolic of a victory in the ongoing conflict with Persia, and Diocletian was hailed as the "founder of eternal peace". The events might have represented a formal end to Carus's eastern campaign, which probably ended without an acknowledged peace. At the conclusion of discussions with the Persians, Diocletian re-organized the Mesopotamian frontier and fortified the city of Circesium

Circesium ( syc, ܩܪܩܣܝܢ ', grc, Κιρκήσιον), known in Arabic as al-Qarqisiya, was a Roman fortress city near the junction of the Euphrates and Khabur rivers, located at the empire's eastern frontier with the Sasanian Empire. It wa ...

(Buseire, Syria) on the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

.

Maximian made Augustus

Maximian's campaigns were not proceeding as smoothly. The Bagaudae had been easily suppressed, butCarausius

Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius (died 293) was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. He was a Menapian from Belgic Gaul, who usurped power in 286, during the Carausian Revolt, declaring himself emperor in Britain and no ...

, the man he had put in charge of operations against Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

and Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

pirates

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

on the Saxon Shore

The Saxon Shore ( la, litus Saxonicum) was a military command of the late Roman Empire, consisting of a series of fortifications on both sides of the Channel. It was established in the late 3rd century and was led by the "Count of the Saxon Shor ...

, had, according to literary sources, begun keeping the goods seized from the pirates for himself. Maximian issued a death warrant for his larcenous subordinate. Carausius fled the Continent, proclaimed himself emperor, and agitated Britain and northwestern Gaul into open revolt against Maximian and Diocletian.

Far more probable, according to the archaeological evidence available, is that Carausius probably had held some important military post in Britain and had already a firm basis of power in both Britain and Northern Gaul (a coin hoard found in Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of ...

proves that he was in control of that mainland area at the beginning of his rebellion) and that he profited from the lack of legitimacy of the central government. Carausius strove to have his legitimacy as a junior emperor acknowledged by Diocletian: in his coinage (of far better quality than the official one, especially his silver pieces) he extolled the "concord" between him and the central power (PAX AVGGG, "the Peace of the three Augusti", read one bronze piece from 290, displaying, on the other side, Carausius together with Diocletian and Maximian, with the caption CARAVSIVS ET FRATRES SVI, "Carausius & his brothers"). However, Diocletian could not allow elbow room to a breakaway regional usurper following in Postumus

Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus was a Roman commander of Batavian origin, who ruled as Emperor of the splinter state of the Roman Empire known to modern historians as the Gallic Empire. The Roman army in Gaul threw off its allegiance to G ...

's footprints; he could not allow such a usurper to enter, solely of his own accord, the imperial college. So, Carausius had to go.

Spurred by the crisis, on 1 April 286, Maximian took up the title of ''Augustus'' (emperor). His appointment is unusual in that it was impossible for Diocletian to have been present to witness the event. It has even been suggested that Maximian usurped the title and was only later recognized by Diocletian in hopes of avoiding civil war. This suggestion is unpopular, as it is clear that Diocletian meant for Maximian to act with a certain amount of independence. It may be posited, however, that Diocletian felt the need to bind Maximian closer to him, by making him his empowered associate, in order to avoid the possibility of having him striking some sort of deal with Carausius.

Maximian realized that he could not immediately suppress the rogue commander, so in 287 he campaigned solely against tribes beyond the

Maximian realized that he could not immediately suppress the rogue commander, so in 287 he campaigned solely against tribes beyond the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

instead. As Carausius was allied to the Franks, Maximian's campaigns could be seen as an effort to deny the separatist emperor in Britain a basis of support on the mainland. The following spring, as Maximian prepared a fleet for an expedition against Carausius, Diocletian returned from the East to meet Maximian. The two emperors agreed on a joint campaign against the Alamanni. Diocletian invaded Germania through Raetia while Maximian progressed from Mainz. Each emperor burned crops and food supplies as he went, destroying the Germans' means of sustenance. The two men added territory to the empire and allowed Maximian to continue preparations against Carausius without further disturbance. On his return to the East, Diocletian managed what was probably another rapid campaign against the resurgent Sarmatians. No details survive, but surviving inscriptions indicate that Diocletian took the title ''Sarmaticus Maximus'' after 289.

In the East, Diocletian engaged in diplomacy with desert tribes in the regions between Rome and Persia. He might have been attempting to persuade them to ally themselves with Rome, thus reviving the old, Rome-friendly, Palmyrene sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

, or simply attempting to reduce the frequency of their incursions. No details survive for these events.Some of the princes of these states were Persian client kings, a disturbing fact in light of increasing tensions with the Sassanids. In the West, Maximian lost the fleet built in 288 and 289, probably in the early spring of 290. The panegyrist

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of grc, ...

who refers to the loss suggests that its cause was a storm, but this might simply have been an attempt to conceal an embarrassing military defeat. Diocletian broke off his tour of the Eastern provinces soon thereafter. He returned with haste to the West, reaching Emesa by 10 May 290, and Sirmium on the Danube by 1 July 290.

Diocletian met Maximian in Milan in the winter of 290–91, either in late December 290 or January 291. The meeting was undertaken with a sense of solemn pageantry. The emperors spent most of their time in public appearances. It has been surmised that the ceremonies were arranged to demonstrate Diocletian's continuing support for his faltering colleague. A deputation from the Roman Senate met with the emperors, renewing its infrequent contact with the Imperial office. The choice of Milan over Rome further snubbed the capital's pride. But then it was already a long established practice that Rome itself was only a ceremonial capital, as the actual seat of the Imperial administration was determined by the needs of defense. Long before Diocletian, Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; c. 218 – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empi ...

(r. 253–68) had chosen Milan as the seat of his headquarters. If the panegyric detailing the ceremony implied that the true center of the empire was not Rome, but where the emperor sat ("...the capital of the empire appeared to be there, where the two emperors met"), it simply echoed what had already been stated by the historian Herodian

Herodian or Herodianus ( el, Ἡρωδιανός) of Syria, sometimes referred to as "Herodian of Antioch" (c. 170 – c. 240), was a minor Roman civil servant who wrote a colourful history in Greek titled ''History of the Empire from the Death o ...

in the early third century: "Rome is where the emperor is". During the meeting, decisions on matters of politics and war were probably made in secret. The Augusti would not meet again until 303.

Tetrarchy

Foundation of the Tetrarchy

Some time after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against

Some time after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of the war against Carausius from Maximian to Flavius Constantius, a former Governor of Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to Aurelian's campaigns against Zenobia

Septimia Zenobia (Palmyrene Aramaic: , , vocalized as ; AD 240 – c. 274) was a third-century queen of the Palmyrene Empire in Syria. Many legends surround her ancestry; she was probably not a commoner and she married the ruler of the city, ...

(272–73). He was Maximian's praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

in Gaul, and the husband to Maximian's daughter, Theodora

Theodora is a given name of Greek origin, meaning "God's gift".

Theodora may also refer to:

Historical figures known as Theodora

Byzantine empresses

* Theodora (wife of Justinian I) ( 500 – 548), saint by the Orthodox Church

* Theodora o ...

. On 1 March 293 at Milan, Maximian gave Constantius the office of caesar. On 1 March 293, in either Philippopolis (Plovdiv

Plovdiv ( bg, Пловдив, ), is the second-largest city in Bulgaria, standing on the banks of the Maritsa river in the historical region of Thrace. It has a population of 346,893 and 675,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Plovdiv is the c ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

) or Sirmium, Diocletian would do the same for Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

, husband to Diocletian's daughter Valeria, and perhaps Diocletian's praetorian prefect. Constantius was assigned Gaul and Britain. Galerius was initially assigned Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and responsibility for the eastern borderlands.

This arrangement is called the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

, from a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

term meaning "rulership by four". The Tetrarchs were more or less sovereign in their own lands, and they travelled with their own imperial courts, administrators, secretaries, and armies. They were joined by blood and marriage; Diocletian and Maximian now styled themselves as brothers. The senior co-emperors formally adopted Galerius and Constantius as sons in 293. These relationships implied a line of succession. Galerius and Constantius would become ''Augusti'' after the departure of Diocletian and Maximian. Maximian's son Maxentius and Constantius's son Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

would then become Caesars. In preparation for their future roles, Constantine and Maxentius were taken to Diocletian's court in Nicomedia.

Demise of Carausius's breakaway Roman Empire

Just before his creation as Caesar, Constantius proceeded to cut Carausius from his base of support in Gaul, recovering Boulogne after a hotly fought siege, a success that would result in Carausius being murdered and replaced by his aideAllectus

Allectus (died 296) was a Britannic Empire, Roman-Britannic Roman usurper, usurper-Roman emperors, emperor in Roman Britain, Britain and northern Gaul from 293 to 296.

History

Allectus was treasurer to Carausius, a Menapii, Menapian officer in the ...

, who would hold out in his Britain stronghold for a further three years until a two-pronged naval invasion resulted in Allectus's defeat and death at the hands of Constantius's praetorian prefect Julius Asclepiodotus Julius Asclepiodotus was a Roman Empire, Roman praetorian prefect who, according to the ''Historia Augusta'', served under the Roman emperor, emperors Aurelian, Marcus Aurelius Probus, Probus and Diocletian, and was List of late imperial Roman consu ...

, during a land battle somewhere near Farnham

Farnham ( /ˈfɑːnəm/) is a market town and civil parish in Surrey, England, around southwest of London. It is in the Borough of Waverley, close to the county border with Hampshire. The town is on the north branch of the River Wey, a trib ...

. Constantius himself, after disembarking in the south east, delivered London from a looting party of Frankish deserters in Allectus's pay, something that allowed him to assume the role of liberator of Britain. A famous commemorative medallion depicts a personification of London supplying the victorious Constantius on horseback in which he describes himself as ''redditor lucis aeternae'', 'restorer of the eternal light (''viz.'', of Rome).' The suppression of this threat to the Tetrarchs' legitimacy allowed both Constantius and Maximian to concentrate on outside threats: by 297 Constantius was back on the Rhine and Maximian engaged in a full-scale African campaign against Frankish pirates and nomads, eventually making a triumphal entry into Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

on 10 March 298. However, Maximian's failure to deal with Carausius and Allectus on his own had jeopardized the position of Maxentius as putative heir to his father's post as Augustus of the West, with Constantius's son Constantine appearing as a rival claimant.

Conflict in the Balkans and Egypt

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 travelling with Galerius from Sirmium (

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 travelling with Galerius from Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica

Sremska Mitrovica (; sr-Cyrl, Сремска Митровица, hu, Szávaszentdemeter, la, Sirmium) is a city and the administrative center of the Srem District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. It is situated on the left bank ...

, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

) to Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

(Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

). Diocletian then returned to Sirmium, where he would remain for the following winter and spring. He campaigned against the Sarmatians again in 294, probably in the autumn, and won a victory against them. The Sarmatians' defeat kept them from the Danube provinces for a long time. Meanwhile, Diocletian built forts north of the Danube, at Aquincum

Aquincum (, ) was an ancient city, situated on the northeastern borders of the province of Pannonia within the Roman Empire. The ruins of the city can be found today in Budapest, the capital city of Hungary. It is believed that Marcus Aurelius w ...

(Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

), Bononia (Vidin

Vidin ( bg, Видин, ; Old Romanian: Diiu) is a port city on the southern bank of the Danube in north-western Bulgaria. It is close to the borders with Romania and Serbia, and is also the administrative centre of Vidin Province, as well as o ...

, Bulgaria), Ulcisia Vetera, Castra Florentium, Intercisa (Dunaújváros

Dunaújváros (; also known by other alternative names) is an industrial city in Fejér County, Central Hungary. It is a city with county rights. Situated 70 kilometres (43 miles) south of Budapest on the Danube, the city is best known for its ...

, Hungary), and Onagrinum (Begeč

Begeč ( sr-cyr, Бегеч) is a suburban settlement of the city of Novi Sad in Serbia. It is situated on the river Danube, approximately west of Novi Sad, on the Bačka Palanka-Novi Sad road. According to the 2011 census, the village had a Serb ...

, Serbia). The new forts became part of a new defensive line called the ''Ripa Sarmatica''. In 295 and 296 Diocletian campaigned in the region again, and won a victory over the Carpi in the summer of 296. Later during both 299 and 302, as Diocletian was then residing in the East, it was Galerius's turn to campaign victoriously on the Danube. By the end of his reign, Diocletian had secured the entire length of the Danube, provided it with forts, bridgeheads, highways, and walled towns, and sent fifteen or more legions to patrol the region; an inscription at Sexaginta Prista

Ruse (also transliterated as Rousse, Russe; bg, Русе ) is the fifth largest city in Bulgaria. Ruse is in the northeastern part of the country, on the right bank of the Danube, opposite the Romanian city of Giurgiu, approximately south of ...

on the Lower Danube extolled restored tranquility to the region. The defense came at a heavy cost, but was a significant achievement in an area difficult to defend.

Galerius, meanwhile, was engaged during 291–293 in disputes in Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient ...

, where he suppressed a regional uprising. He would return to Syria in 295 to fight the revanchist Persian empire. Diocletian's attempts to bring the Egyptian tax system in line with Imperial standards stirred discontent, and a revolt swept the region after Galerius's departure. The usurper Domitius Domitianus

Lucius Domitius Domitianus or, rarely, Domitian III, was a Roman usurper against Diocletian, who seized power for a short time in Egypt.

History

Nothing is known of the background and family of Domitianus. He may have served as prefect of Egyp ...

declared himself ''Augustus'' in July or August 297. Much of Egypt, including Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, recognized his rule. Diocletian moved into Egypt to suppress him, first putting down rebels in the Thebaid

The Thebaid or Thebais ( grc-gre, Θηβαΐς, ''Thēbaïs'') was a region in ancient Egypt, comprising the 13 southernmost nomes of Upper Egypt, from Abydos to Aswan.

Pharaonic history

The Thebaid acquired its name from its proximity to ...

in the autumn of 297, then moving on to besiege Alexandria. Domitianus died in December 297, by which time Diocletian had secured control of the Egyptian countryside. Alexandria, however, whose defense was organized under Domitianus's former ''corrector

A corrector (English plural ''correctors'', Latin plural ''correctores'') is a person or object practicing correction, usually by removing or rectifying errors.

The word is originally a Roman title, ''corrector'', derived from the Latin verb ''c ...

'' Aurelius Achilleus

Aurelius Achilleus ( 297–298 AD) was a rebel against the Roman emperor Diocletian in Egypt in 297 AD.

All literary sources name Achilleus as an imperial pretender and the leader of the rebellion, but numismatic and papyrological evidence attrib ...

, was to hold out until a later date, probably March 298.

Bureaucratic affairs were completed during Diocletian's stay: a census took place, and Alexandria, in punishment for its rebellion, lost the ability to mint independently. Diocletian's reforms in the region, combined with those of Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

, brought Egyptian administrative practices much closer to Roman standards. Diocletian travelled south along the Nile the following summer, where he visited Oxyrhynchus

Oxyrhynchus (; grc-gre, Ὀξύρρυγχος, Oxýrrhynchos, sharp-nosed; ancient Egyptian ''Pr-Medjed''; cop, or , ''Pemdje''; ar, البهنسا, ''Al-Bahnasa'') is a city in Middle Egypt located about 160 km south-southwest of Cairo ...

and Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; arz, جزيرة الفنتين; el, Ἐλεφαντίνη ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological sites on the island were inscribed on the UNESCO ...

. In Nubia, he made peace with the Nobatae

Nobatia or Nobadia (; Greek: Νοβαδία, ''Nobadia''; Old Nubian: ⲙⲓⲅⲛ̅ ''Migin'' or ⲙⲓⲅⲓⲧⲛ︦ ⲅⲟⲩⲗ, ''Migitin Goul'' lit. "''of Nobadia's land''") was a late antique kingdom in Lower Nubia. Together with the tw ...

and Blemmyes

The Blemmyes ( grc, Βλέμμυες, Latin: ''Blemmyae'') were an Eastern Desert people who appeared in written sources from the 7th century BC until the 8th century AD.. By the late 4th century, they had occupied Lower Nubia and established a k ...

tribes. Under the terms of the peace treaty Rome's borders moved north to Philae

; ar, فيلة; cop, ⲡⲓⲗⲁⲕ

, alternate_name =

, image = File:File, Asuán, Egipto, 2022-04-01, DD 93.jpg

, alt =

, caption = The temple of Isis from Philae at its current location on Agilkia Island in Lake Nasse ...

and the two tribes received an annual gold stipend. Diocletian left Africa quickly after the treaty, moving from Upper Egypt in September 298 to Syria in February 299. He met with Galerius in Mesopotamia.

War with Persia

Invasion, counterinvasion

In 294,

In 294, Narseh

Narseh (also spelled Narses or Narseus; pal, 𐭭𐭥𐭮𐭧𐭩, New Persian: , ''Narsē'') was the seventh Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 293 to 303.

The youngest son of Shapur I (), Narseh served as the governor of Sakastan, Hind and T ...

, a son of Shapur who had been passed over for the Sassanid succession, came to power in Persia. Narseh eliminated Bahram III, a young man installed in the wake of Bahram II's death in 293. In early 294, Narseh sent Diocletian the customary package of gifts between the empires, and Diocletian responded with an exchange of ambassadors. Within Persia, however, Narseh was destroying every trace of his immediate predecessors from public monuments. He sought to identify himself with the warlike kings Ardashir Ardeshir or Ardashir ( Persian: اردشیر; also spelled as Ardasher) is a Persian name popular in Iran and other Persian-speaking countries. Ardashir is the New Persian form of the Middle Persian name , which is ultimately from Old Iranian ''*Ar ...

(r. 226–41) and Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, Šābuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardas ...

(r. 241–72), who had defeated and imprisoned Emperor Valerian (r. 253–260) following his failed invasion of the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

.

Narseh declared war on Rome in 295 or 296. He appears to have first invaded western Armenia, where he seized the lands delivered to Tiridates in the peace of 287. Narseh moved south into Roman Mesopotamia in 297, where he inflicted a severe defeat on Galerius in the region between Carrhae (Harran

Harran (), historically known as Carrhae ( el, Kάρραι, Kárrhai), is a rural town and district of the Şanlıurfa Province in southeastern Turkey, approximately 40 kilometres (25 miles) southeast of Urfa and 20 kilometers from the border cr ...

, Turkey) and Callinicum (Raqqa

Raqqa ( ar, ٱلرَّقَّة, ar-Raqqah, also and ) (Kurdish languages, Kurdish: Reqa/ ڕەقە) is a city in Syria on the northeast bank of the Euphrates River, about east of Aleppo. It is located east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. T ...

, Syria). The historian Fergus Millar

Sir Fergus Graham Burtholme Millar, (; 5 July 1935 – 15 July 2019) was a British ancient historian and academic. He was Camden Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxford between 1984 and 2002. He numbers among the most influ ...

notes, probably somewhere on the Balikh River

The Balikh River ( ar, نهر البليخ) is a perennial river that originates in the spring of Ain al-Arous near Tell Abyad in the Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests ecoregion. It flows due south and joins the Euphra ...

). Diocletian may or may not have been present at the battle, but he quickly divested himself of all responsibility. In a public ceremony at Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, the official version of events was clear: Galerius was responsible for the defeat; Diocletian was not. Diocletian publicly humiliated Galerius, forcing him to walk for a mile at the head of the Imperial caravan, still clad in the purple robes of the Emperor.

Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent collected from the empire's Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. It is unclear if Diocletian was present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria. Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius's force, to Narseh's disadvantage; the rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius continued moving down the Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman territory along the Euphrates.

Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent collected from the empire's Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. It is unclear if Diocletian was present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria. Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius's force, to Narseh's disadvantage; the rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius continued moving down the Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman territory along the Euphrates.

Peace negotiations

Narseh sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives and children in the course of the war, but Galerius dismissed him. Serious peace negotiations began in the spring of 299. The ''magister memoriae'' (secretary) of Diocletian and Galerius, Sicorius Probus, was sent to Narseh to present terms. The conditions of the resulting Peace of Nisibis were heavy: Armenia returned to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border;Caucasian Iberia

In Greco-Roman geography, Iberia (Ancient Greek: ''Iberia''; la, Hiberia) was an exonym for the Georgian kingdom of Kartli ( ka, ქართლი), known after its core province, which during Classical Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages ...

would pay allegiance to Rome under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia: Ingilene

Angeghtun () or Ingilene ( grc, Ἰγγηληνή; ) was a district of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia centered on the city and fortress of Anggh (), which gave its name to the district. Anggh is often identified with the modern city of Eğil in Tu ...

, Sophanene (Sophene

Sophene ( hy, Ծոփք, translit=Tsopkʻ, grc, Σωφηνή, translit=Sōphēnē or hy, Չորրորդ Հայք, lit=Fourth Armenia) was a province of the ancient kingdom of Armenia, located in the south-west of the kingdom, and of the Ro ...

), Arzanene (Aghdznik

Arzanene ( el, Ἀρζανηνή) or Aghdznik () was a historical region in the southwest of the ancient kingdom of Armenia. It was ruled by one of the four ''bdeashkhs'' (''bidakhsh'', ''vitaxa'') of Armenia, the highest ranking nobles below t ...

), Corduene

Corduene hy, Կորճայք, translit=Korchayk; ; romanized: ''Kartigini'') was an ancient historical region, located south of Lake Van, present-day eastern Turkey.

Many believe that the Kardouchoi—mentioned in Xenophon’s Anabasis as havin ...

(Carduene), and Zabdicene (near modern Hakkâri, Turkey). These regions included the passage of the Tigris through the Anti-Taurus

The Anti-Taurus (Greek: Αντίταυρος, Latin: Anti-Taurus (ANTITAVRVS), its western part is called today by the Turks ''Aladağlar'') is the central chain of the mountain ranges of the Armenian Highlands, which runs from west to east acro ...

range; the Bitlis

Bitlis ( hy, Բաղեշ '; ku, Bidlîs; ota, بتليس) is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Bitlis Province. The city is located at an elevation of 1,545 metres, 15 km from Lake Van, in the steep-sided valley of the Bitlis R ...

pass, the quickest southerly route into Persian Armenia; and access to the Tur Abdin

Tur Abdin ( syr, ܛܽܘܪ ܥܰܒ݂ܕܺܝܢ or ܛܘܼܪ ܥܲܒ݂ܕܝܼܢ, Ṭūr ʿAḇdīn) is a hilly region situated in southeast Turkey, including the eastern half of the Mardin Province, and Şırnak Province west of the Tigris, on the borde ...

plateau.

A stretch of land containing the later strategic strongholds of Amida (Diyarbakır

Diyarbakır (; ; ; ) is the largest Kurdish-majority city in Turkey. It is the administrative center of Diyarbakır Province.

Situated around a high plateau by the banks of the Tigris river on which stands the historic Diyarbakır Fortress, ...

, Turkey) and Bezabde

Bezabde or Bazabde was a fortress city on the eastern Roman frontier. Located in Zabdicene, it played a role in the Roman-Persian Wars of the 4th century. It was besieged two times in 360, narrated in detail by Ammianus Marcellinus. The Sasanians ...