Dinophyta on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The dinoflagellates (

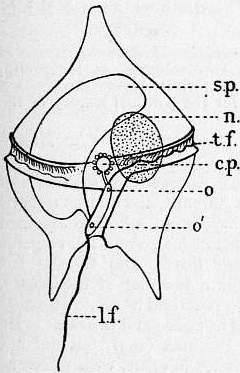

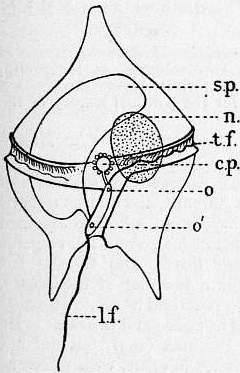

Dinoflagellates are unicellular and possess two dissimilar flagella arising from the ventral cell side (dinokont flagellation). They have a ribbon-like transverse flagellum with multiple waves that beats to the cell's left, and a more conventional one, the longitudinal flagellum, that beats posteriorly. The transverse flagellum is a wavy ribbon in which only the outer edge undulates from base to tip, due to the action of the axoneme which runs along it. The axonemal edge has simple hairs that can be of varying lengths. The flagellar movement produces forward propulsion and also a turning force. The longitudinal flagellum is relatively conventional in appearance, with few or no hairs. It beats with only one or two periods to its wave. The flagella lie in surface grooves: the transverse one in the cingulum and the longitudinal one in the sulcus, although its distal portion projects freely behind the cell. In dinoflagellate species with desmokont flagellation (e.g., ''

Dinoflagellates are unicellular and possess two dissimilar flagella arising from the ventral cell side (dinokont flagellation). They have a ribbon-like transverse flagellum with multiple waves that beats to the cell's left, and a more conventional one, the longitudinal flagellum, that beats posteriorly. The transverse flagellum is a wavy ribbon in which only the outer edge undulates from base to tip, due to the action of the axoneme which runs along it. The axonemal edge has simple hairs that can be of varying lengths. The flagellar movement produces forward propulsion and also a turning force. The longitudinal flagellum is relatively conventional in appearance, with few or no hairs. It beats with only one or two periods to its wave. The flagella lie in surface grooves: the transverse one in the cingulum and the longitudinal one in the sulcus, although its distal portion projects freely behind the cell. In dinoflagellate species with desmokont flagellation (e.g., ''

Dinoflagellates are protists and have been classified using both the

Dinoflagellates are protists and have been classified using both the

A red tide occurs because dinoflagellates are able to reproduce rapidly and copiously as a result of the abundant nutrients in the water. Although the resulting red waves are an interesting visual phenomenon, they contain

A red tide occurs because dinoflagellates are able to reproduce rapidly and copiously as a result of the abundant nutrients in the water. Although the resulting red waves are an interesting visual phenomenon, they contain

At night, water can have an appearance of sparkling light due to the bioluminescence of dinoflagellates. More than 18 genera of dinoflagellates are bioluminescent, and the majority of them emit a blue-green light. These species contain

At night, water can have an appearance of sparkling light due to the bioluminescence of dinoflagellates. More than 18 genera of dinoflagellates are bioluminescent, and the majority of them emit a blue-green light. These species contain

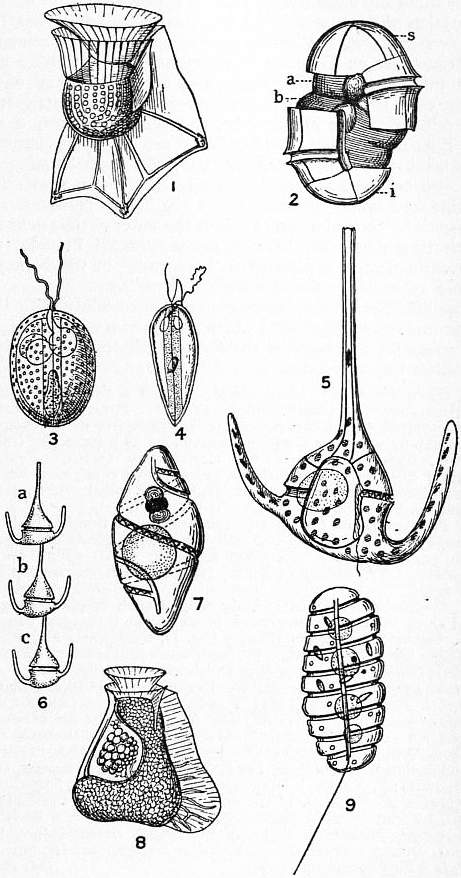

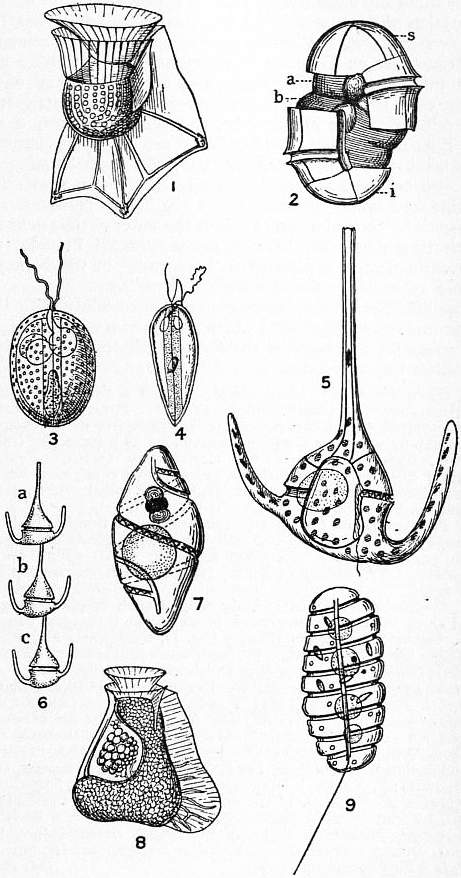

More than 10% of the approximately 2000 known marine dinoflagellate species produce cysts as part of their life cycle (see diagram on the right). These benthic phases play an important role in the ecology of the species, as part of a planktonic-benthic link in which the cysts remain in the sediment layer during conditions unfavorable for vegetative growth and, from there, reinoculate the water column when favorable conditions are restored.

Indeed, during dinoflagellate evolution the need to adapt to fluctuating environments and/or to seasonality is thought to have driven the development of this life cycle stage. Most protists form dormant cysts in order to withstand starvation and UV damage. However, there are enormous differences in the main phenotypic, physiological and resistance properties of each dinoflagellate species cysts. Unlike in higher plants most of this variability, for example in dormancy periods, has not been proven yet to be attributed to latitude adaptation or to depend on other life cycle traits. Thus, despite recent advances in the understanding of the life histories of many dinoflagellate species, including the role of cyst stages, many gaps remain in knowledge about their origin and functionality.

Recognition of the capacity of dinoflagellates to encyst dates back to the early 20th century, in biostratigraphic studies of fossil dinoflagellate cysts. Paul Friedrich Reinsch, Paul Reinsch was the first to identify cysts as the fossilized remains of dinoflagellates. Later, cyst formation from gamete fusion was reported, which led to the conclusion that encystment is associated with sexual reproduction. These observations also gave credence to the idea that microalgal encystment is essentially a process whereby zygotes prepare themselves for a dormant period. Because the resting cysts studied until that time came from sexual processes, dormancy was associated with sexuality, a presumption that was maintained for many years. This attribution was coincident with evolutionary theories about the origin of eukaryotic cell fusion and sexuality, which postulated advantages for species with diploid resting stages, in their ability to withstand nutrient stress and mutational UV radiation through recombinational repair, and for those with haploid vegetative stages, as asexual division doubles the number of cells. Nonetheless, certain environmental conditions may limit the advantages of recombination and sexuality, such that in fungi, for example, complex combinations of haploid and diploid cycles have evolved that include asexual and sexual resting stages.

However, in the general life cycle of cyst-producing dinoflagellates as outlined in the 1960s and 1970s, resting cysts were assumed to be the fate of sexuality, which itself was regarded as a response to stress or unfavorable conditions. Sexuality involves the fusion of haploid gametes from motile planktonic vegetative stages to produce diploid planozygotes that eventually form cysts, or hypnozygotes, whose germination is subject to both endogenous and exogenous controls. Endogenously, a species-specific physiological maturation minimum period (dormancy) is mandatory before germination can occur. Thus, hypnozygotes were also referred to as “resting” or “resistant” cysts, in reference to this physiological trait and their capacity following dormancy to remain viable in the sediments for long periods of time. Exogenously, germination is only possible within a window of favorable environmental conditions.

Yet, with the discovery that planozygotes were also able to divide it became apparent that the complexity of dinoflagellate life cycles was greater than originally thought. Following corroboration of this behavior in several species, the capacity of dinoflagellate sexual phases to restore the vegetative phase, bypassing cyst formation, became well accepted. Further, in 2006 Kremp and Parrow showed the dormant resting cysts of the Baltic cold water dinoflagellates ''Scrippsiella hangoei'' and ''Gymnodinium'' sp. were formed by the direct encystment of haploid vegetative cells, i.e., asexually. In addition, for the zygotic cysts of ''Pfiesteria piscicida'' dormancy was not essential.

More than 10% of the approximately 2000 known marine dinoflagellate species produce cysts as part of their life cycle (see diagram on the right). These benthic phases play an important role in the ecology of the species, as part of a planktonic-benthic link in which the cysts remain in the sediment layer during conditions unfavorable for vegetative growth and, from there, reinoculate the water column when favorable conditions are restored.

Indeed, during dinoflagellate evolution the need to adapt to fluctuating environments and/or to seasonality is thought to have driven the development of this life cycle stage. Most protists form dormant cysts in order to withstand starvation and UV damage. However, there are enormous differences in the main phenotypic, physiological and resistance properties of each dinoflagellate species cysts. Unlike in higher plants most of this variability, for example in dormancy periods, has not been proven yet to be attributed to latitude adaptation or to depend on other life cycle traits. Thus, despite recent advances in the understanding of the life histories of many dinoflagellate species, including the role of cyst stages, many gaps remain in knowledge about their origin and functionality.

Recognition of the capacity of dinoflagellates to encyst dates back to the early 20th century, in biostratigraphic studies of fossil dinoflagellate cysts. Paul Friedrich Reinsch, Paul Reinsch was the first to identify cysts as the fossilized remains of dinoflagellates. Later, cyst formation from gamete fusion was reported, which led to the conclusion that encystment is associated with sexual reproduction. These observations also gave credence to the idea that microalgal encystment is essentially a process whereby zygotes prepare themselves for a dormant period. Because the resting cysts studied until that time came from sexual processes, dormancy was associated with sexuality, a presumption that was maintained for many years. This attribution was coincident with evolutionary theories about the origin of eukaryotic cell fusion and sexuality, which postulated advantages for species with diploid resting stages, in their ability to withstand nutrient stress and mutational UV radiation through recombinational repair, and for those with haploid vegetative stages, as asexual division doubles the number of cells. Nonetheless, certain environmental conditions may limit the advantages of recombination and sexuality, such that in fungi, for example, complex combinations of haploid and diploid cycles have evolved that include asexual and sexual resting stages.

However, in the general life cycle of cyst-producing dinoflagellates as outlined in the 1960s and 1970s, resting cysts were assumed to be the fate of sexuality, which itself was regarded as a response to stress or unfavorable conditions. Sexuality involves the fusion of haploid gametes from motile planktonic vegetative stages to produce diploid planozygotes that eventually form cysts, or hypnozygotes, whose germination is subject to both endogenous and exogenous controls. Endogenously, a species-specific physiological maturation minimum period (dormancy) is mandatory before germination can occur. Thus, hypnozygotes were also referred to as “resting” or “resistant” cysts, in reference to this physiological trait and their capacity following dormancy to remain viable in the sediments for long periods of time. Exogenously, germination is only possible within a window of favorable environmental conditions.

Yet, with the discovery that planozygotes were also able to divide it became apparent that the complexity of dinoflagellate life cycles was greater than originally thought. Following corroboration of this behavior in several species, the capacity of dinoflagellate sexual phases to restore the vegetative phase, bypassing cyst formation, became well accepted. Further, in 2006 Kremp and Parrow showed the dormant resting cysts of the Baltic cold water dinoflagellates ''Scrippsiella hangoei'' and ''Gymnodinium'' sp. were formed by the direct encystment of haploid vegetative cells, i.e., asexually. In addition, for the zygotic cysts of ''Pfiesteria piscicida'' dormancy was not essential.

Image:Oxyrrhis marina.jpg, ''Oxyrrhea, Oxyrrhis marina'' (Oxyrrhea)

Dinophysis acuminata.jpg, ''Dinophysis, Dinophysis acuminata'' (Dinophyceae)

Image:Ceratium sp umitunoobimusi.jpg, ''Ceratium, Ceratium macroceros'' (Dinophyceae)

Image:Ceratium furca.jpg, ''Ceratium, Ceratium furcoides'' (Dinophyceae)

File:Dinoflagellate - SEM MUSE.tif, Unknown dinoflagellate under scanning electron microscope, SEM (Dinophyceae)

Image:Pfiesteria shumwayae.jpg, ''Pfiesteria, Pfiesteria shumwayae'' (Dinophyceae)

File:Symbiodinium.png, ''

International Society for the Study of Harmful AlgaeClassic dinoflagellate monographs

[https://web.archive.org/web/20080930064242/http://www.tafi.org.au/ Tasmanian Aquaculture & Fisheries Institute]

Tree of Life DinoflagellatesCentre of Excellence for Dinophyte Taxonomy CEDiTDinoflagellates

* {{Taxonbar, from1=Q120490, from2=Q21447509, from3=Q9358965 Dinoflagellates, Dinoflagellate biology, Endosymbiotic events Olenekian first appearances Extant Early Triassic first appearances

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

δῖνος ''dinos'' "whirling" and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

''flagellum'' "whip, scourge") are a monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gr ...

group of single-celled eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

s constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cruc ...

, but they also are common in freshwater habitats. Their populations vary with sea surface temperature

Sea surface temperature (SST), or ocean surface temperature, is the ocean temperature close to the surface. The exact meaning of ''surface'' varies according to the measurement method used, but it is between and below the sea surface. Air mas ...

, salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

, and depth. Many dinoflagellates are photosynthetic

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in c ...

, but a large fraction of these are in fact mixotrophic A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comp ...

, combining photosynthesis with ingestion of prey (phagotrophy

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ca ...

and myzocytosis

Myzocytosis (from Greek: myzein, (') meaning "to suck" and kytos (') meaning "container", hence referring to "cell") is a method of feeding found in some heterotrophic organisms. It is also called "cellular vampirism" as the predatory cell pierces ...

).

In terms of number of species, dinoflagellates are one of the largest groups of marine eukaryotes, although substantially smaller than diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising sev ...

s. Some species are endosymbiont

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

s of marine animals and play an important part in the biology of coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

s. Other dinoflagellates are unpigmented predators on other protozoa, and a few forms are parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

(for example, ''Oodinium

''Oodinium'' is a genus of parasitic dinoflagellates. Their hosts are salt- and fresh-water fish, causing a type of fish velvet disease (also called gold dust disease). One species has also been recorded on various cnidarians.

The host typical ...

'' and ''Pfiesteria

''Pfiesteria'' is a genus of heterotrophic dinoflagellates that has been associated with harmful algal blooms and fish kills. ''Pfiesteria'' complex organisms (PCOs) were claimed to be responsible for large fish kills in the 1980s and 1990s on th ...

''). Some dinoflagellates produce resting stages, called dinoflagellate cysts or dinocyst

Dinocysts or dinoflagellate cysts are typically 15 to 100 µm in diameter and produced by around 15–20% of living dinoflagellates as a dormant, zygotic stage of their lifecycle, which can accumulate in the sediments as microfossils. Organic- ...

s, as part of their lifecycles, and are known from 84 of the 350 described freshwater species, and from a little more than 10% of the known marine species. Dinoflagellates are alveolate

The alveolates (meaning "pitted like a honeycomb") are a group of protists, considered a major clade and Biological classification, superphylum within Eukarya. They are currently grouped with the stramenopiles and Rhizaria among the protists with ...

s possessing two flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

, the ancestral condition of bikont

A bikont ("two flagella") is any of the eukaryotic organisms classified in the group Bikonta. Many single-celled members of the group, and the presumed ancestor, have two flagella.

Enzymes

Another shared trait of bikonts is the fusion of two ge ...

s.

About 1,555 species of free-living marine dinoflagellates are currently described. Another estimate suggests about 2,000 living species, of which more than 1,700 are marine (free-living, as well as benthic) and about 220 are from fresh water. The latest estimates suggest a total of 2,294 living dinoflagellate species, which includes marine, freshwater, and parasitic dinoflagellates.

A rapid accumulation of certain dinoflagellates can result in a visible coloration of the water, colloquially known as red tide

A harmful algal bloom (HAB) (or excessive algae growth) is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural phycotoxin, algae-produced toxins, mechanical damage to other organisms, or by other means. HABs are ...

(a harmful algal bloom

A harmful algal bloom (HAB) (or excessive algae growth) is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural algae-produced toxins, mechanical damage to other organisms, or by other means. HABs are sometimes ...

), which can cause shellfish poisoning

Shellfish poisoning includes four syndromes that share some common features and are primarily associated with bivalve molluscs (such as mussels, clams, oysters and scallops.) As filter feeders, these shellfish may accumulate toxins produced by ...

if humans eat contaminated shellfish. Some dinoflagellates also exhibit bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some b ...

—primarily emitting blue-green light. Thus, some parts of the ocean light up at night giving blue-green light.

Etymology

The term "dinoflagellate" is a combination of the Greek ''dinos'' and the Latin ''flagellum''. ''Dinos'' means "whirling" and signifies the distinctive way in which dinoflagellates were observed to swim. ''Flagellum'' means "whip" and this refers to theirflagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

.

History

In 1753, the first modern dinoflagellates were described by Henry Baker as "Animalcules which cause the Sparkling Light in Sea Water", and named byOtto Friedrich Müller

Otto Friedrich Müller, also known as Otto Friedrich Mueller (2 November 1730 – 26 December 1784) was a Danish naturalist and scientific illustrator.

Biography

Müller was born in Copenhagen. He was educated for the church, became tutor to a yo ...

in 1773. The term derives from the Greek word δῖνος (''dînos''), meaning whirling, and Latin ''flagellum'', a diminutive term for a whip or scourge.

In the 1830s, the German microscopist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (19 April 1795 – 27 June 1876) was a German naturalist, zoologist, comparative anatomist, geologist, and microscopist. Ehrenberg was an evangelist and was considered to be of the most famous and productive scie ...

examined many water and plankton samples and proposed several dinoflagellate genera that are still used today including ''Peridinium, Prorocentrum'', and ''Dinophysis''.

These same dinoflagellates were first defined by Otto Bütschli

Johann Adam Otto Bütschli (3 May 1848 – 2 February 1920) was a German zoologist and professor at the University of Heidelberg. He specialized in invertebrates and insect development. Many of the groups of protists were first recognized by him.

...

in 1885 as the flagellate

A flagellate is a cell or organism with one or more whip-like appendages called flagella. The word ''flagellate'' also describes a particular construction (or level of organization) characteristic of many prokaryotes and eukaryotes and their ...

order Dinoflagellida. Botanists treated them as a division of algae, named Pyrrophyta or Pyrrhophyta ("fire algae"; Greek ''pyrr(h)os'', fire) after the bioluminescent forms, or Dinophyta. At various times, the cryptomonad

The cryptomonads (or cryptophytes) are a group of algae, most of which have plastids. They are common in freshwater, and also occur in marine and brackish habitats. Each cell is around 10–50 μm in size and flattened in shape, with an anterio ...

s, ebriid

The Ebridea is a group of phagotrophic flagellate eukaryotes present in marine coastal plankton communities worldwide. ''Ebria tripartita'' is one of two (possibly four) described extant species in the Ebridea.

Members of this group are named fo ...

s, and ellobiopsids have been included here, but only the last are now considered close relatives. Dinoflagellates have a known ability to transform from noncyst to cyst-forming strategies, which makes recreating their evolutionary history extremely difficult.

Morphology

Prorocentrum

The Prorocentrales are a small order of dinoflagellates. They are distinguished by having their two flagella inserted apically, rather than ventrally as in other groups. One flagellum extends forward and the other circles its base, and there are ...

''), the two flagella are differentiated as in dinokonts, but they are not associated with grooves.

Dinoflagellates have a complex cell covering called an amphiesma or cortex, composed of a series of membranes, flattened vesicle

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

s called alveoli (= amphiesmal vesicles) and related structures. In In thecate ("armoured") dinoflagellates, these support overlapping cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

plates to create a sort of armor called the theca or lorica, as opposed to athecate ("nude") dinoflagellates. These occur in various shapes and arrangements, depending on the species and sometimes on the stage of the dinoflagellate. Conventionally, the term tabulation has been used to refer to this arrangement of thecal plates. The plate configuration can be denoted with the plate formula or tabulation formula. Fibrous extrusome Extrusomes are membrane-bound structures in some eukaryotes which, under certain conditions, discharge their contents outside the cell. There are a variety of different types, probably not homologous, and serving various functions.

Notable extru ...

s are also found in many forms.

A transverse groove, the so-called cingulum (or cigulum) runs around the cell, thus dividing it into an anterior (episoma) and posterior (hyposoma). If and only if a theca is present, the parts are called epitheca and hypotheca, respectively. Posteriorly, starting from the transverse groove, there is a longitudinal furrow called the sulcus. The transverse flagellum strikes in the cingulum, the longitudinal flagellum in the sulcus.

Together with various other structural and genetic details, this organization indicates a close relationship between the dinoflagellates, the Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. T ...

, and ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagellum, eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a ...

s, collectively referred to as the alveolate

The alveolates (meaning "pitted like a honeycomb") are a group of protists, considered a major clade and Biological classification, superphylum within Eukarya. They are currently grouped with the stramenopiles and Rhizaria among the protists with ...

s.

Dinoflagellate tabulations can be grouped into six "tabulation types": gymnodinoid

The Gymnodiniales are an order of dinoflagellates, of the class Dinophyceae. Members of the order are known as gymnodinioid or gymnodinoid (terms that can also refer to any organism of similar morphology). They are athecate, or lacking an armore ...

, suessoid, gonyaulacoid– peridinioid, nannoceratopsioid, dinophysioid, and prorocentroid.

The chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s in most photosynthetic dinoflagellates are bound by three membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

s, suggesting they were probably derived from some ingested algae. Most photosynthetic species contain chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to a ...

s ''a'' and c2, the carotenoid beta-carotene, and a group of xanthophyll

Xanthophylls (originally phylloxanthins) are yellow pigments that occur widely in nature and form one of two major divisions of the carotenoid group; the other division is formed by the carotenes. The name is from Greek (, "yellow") and (, "l ...

s that appears to be unique to dinoflagellates, typically peridinin

Peridinin is a light-harvesting apocarotenoid, a pigment associated with chlorophyll and found in the peridinin-chlorophyll-protein (PCP) light-harvesting complex in dinoflagellates, best studied in ''Amphidinium carterae''.

Biological significan ...

, dinoxanthin

Dinoxanthin is a type of xanthophyll found in dinoflagellates. This compound is a potential antioxidant and may help to protect dinoflagellates against reactive oxygen species

In chemistry, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive c ...

, and diadinoxanthin

Diadinoxanthin is a pigment found in phytoplankton. It has the formula C40H54O3. It gives rise to the xanthophylls diatoxanthin and dinoxanthin.

Diadinoxanthin is a plastid pigment. Plastid pigments include chlorophylls a and c, fucoxanthin, hete ...

. These pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compo ...

s give many dinoflagellates their typical golden brown color. However, the dinoflagellates ''Karenia brevis

''Karenia brevis'' is a microscopic, single-celled, photosynthetic organism in the genus '' Karenia''. It is a marine dinoflagellate commonly found in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. It is the organism responsible for the "Florida red tides" t ...

, Karenia mikimotoi,'' and '' Karlodinium micrum'' have acquired other pigments through endosymbiosis, including fucoxanthin

Fucoxanthin is a xanthophyll, with formula C42H58O6. It is found as an accessory pigment in the chloroplasts of brown algae and most other heterokonts, giving them a brown or olive-green color. Fucoxanthin absorbs light primarily in the blue-green ...

.

This suggests their chloroplasts were incorporated by several endosymbiotic event

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek language, G ...

s involving already colored or secondarily colorless forms. The discovery of plastid

The plastid (Greek: πλαστός; plastós: formed, molded – plural plastids) is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. They are considered to be intracellular endosy ...

s in the Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. T ...

has led some to suggest they were inherited from an ancestor common to the two groups, but none of the more basal lines has them.

All the same, the dinoflagellate cell consists of the more common organelles such as rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

, Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ins ...

, mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

, lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

and starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diets ...

grains, and food vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic mo ...

s. Some have even been found with a light-sensitive organelle, the eyespot or stigma, or a larger nucleus containing a prominent nucleolus

The nucleolus (, plural: nucleoli ) is the largest structure in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis, which is the synthesis of ribosomes. The nucleolus also participates in the formation of sig ...

. The dinoflagellate '' Erythropsidium'' has the smallest known eye.

Some athecate species have an internal skeleton consisting of two star-like siliceous

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

elements that has an unknown function, and can be found as microfossils

A microfossil is a fossil that is generally between 0.001 mm and 1 mm in size, the visual study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. A fossil which can be studied with the naked eye or low-powered magnification, ...

. Tappan gave a survey of dinoflagellates with internal skeletons. This included the first detailed description of the pentasters A small number of dinoflagellates contain an internal skeleton. One of the best known species is perhaps ''Actiniscus pentasterias'', in which each cell contains a pair of siliceous five-armed stars surrounding the nucleus. This species was original ...

in '' Actiniscus pentasterias'', based on scanning electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

. They are placed within the order Gymnodiniales

The Gymnodiniales are an order of dinoflagellates, of the class Dinophyceae. Members of the order are known as gymnodinioid or gymnodinoid (terms that can also refer to any organism of similar morphology). They are athecate, or lacking an armore ...

, suborder Actiniscineae.

Theca structure and formation

The formation of thecal plates has been studied in detail through ultrastructural studies.The dinoflagellate nucleus: dinokaryon

'Core dinoflagellates' ( dinokaryotes) have a peculiar form ofnucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

, called a dinokaryon A dinokaryon is a eukaryotic nucleus present in dinoflagellates in which the chromosomes are fibrillar in appearance (i.e. with unmasked DNA fibrils) and are more or less continuously condensed.

The nuclear envelope does not break down during mi ...

, in which the chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s are attached to the nuclear membrane

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the nucleus, which encloses the genetic material.

The nuclear envelope consists of two lipid bilayer membrane ...

. These carry reduced number of histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

s. In place of histones, dinoflagellate nuclei contain a novel, dominant family of nuclear proteins that appear to be of viral origin, thus are called Dinoflagellate viral nucleoproteins (DVNPs) which are highly basic, bind DNA with similar affinity to histones, and occur in multiple posttranslationally modified forms. Dinoflagellate nuclei remain condensed throughout interphase rather than just during mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

, which is closed and involves a uniquely extranuclear mitotic spindle

In cell biology, the spindle apparatus refers to the cytoskeletal structure of eukaryotic cells that forms during cell division to separate sister chromatids between daughter cells. It is referred to as the mitotic spindle during mitosis, a pr ...

. In This sort of nucleus was once considered to be an intermediate between the nucleoid region of prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s and the true nuclei of eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

s, so were termed "mesokaryotic", but now are considered derived rather than primitive traits (i. e. ancestors of dinoflagellates had typical eukaryotic nuclei). In addition to dinokaryotes, DVNPs can be found in a group of basal dinoflagellates (known as Marine Alveolate

The alveolates (meaning "pitted like a honeycomb") are a group of protists, considered a major clade and Biological classification, superphylum within Eukarya. They are currently grouped with the stramenopiles and Rhizaria among the protists with ...

s, "MALVs") that branch as sister to dinokaryotes (Syndiniales

The Syndiniales are an order of early branching dinoflagellates (also known as Marine Alveolates, "MALVs"), found as parasites of crustaceans, fish, algae, cnidarians, and protists (ciliates, radiolarians, other dinoflagellates). The troph ...

).

Classification

Generality

Dinoflagellates are protists and have been classified using both the

Dinoflagellates are protists and have been classified using both the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature

The ''International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants'' (ICN) is the set of rules and recommendations dealing with the formal botanical names that are given to plants, fungi and a few other groups of organisms, all those "trad ...

(ICBN, now renamed as ICN) and the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the ...

(ICZN). About half of living dinoflagellate species are autotrophs possessing chloroplasts and half are nonphotosynthesising heterotrophs.

The peridinin

Peridinin is a light-harvesting apocarotenoid, a pigment associated with chlorophyll and found in the peridinin-chlorophyll-protein (PCP) light-harvesting complex in dinoflagellates, best studied in ''Amphidinium carterae''.

Biological significan ...

dinoflagellates, named after their peridinin plastids, appear to be ancestral for the dinoflagellate lineage. Almost half of all known species have chloroplasts, which are either the original peridinin plastids or new plastids acquired from other lineages of unicellular algae through endosymbiosis. The remaining species have lost their photosynthetic abilities and have adapted to a heterotrophic, parasitic or kleptoplastic lifestyle.

Most (but not all) dinoflagellates have a dinokaryon A dinokaryon is a eukaryotic nucleus present in dinoflagellates in which the chromosomes are fibrillar in appearance (i.e. with unmasked DNA fibrils) and are more or less continuously condensed.

The nuclear envelope does not break down during mi ...

, described below (see: Life cycle

Life cycle, life-cycle, or lifecycle may refer to:

Science and academia

*Biological life cycle, the sequence of life stages that an organism undergoes from birth to reproduction ending with the production of the offspring

*Life-cycle hypothesis, ...

, below). Dinoflagellates with a dinokaryon are classified under Dinokaryota, while dinoflagellates without a dinokaryon are classified under Syndiniales

The Syndiniales are an order of early branching dinoflagellates (also known as Marine Alveolates, "MALVs"), found as parasites of crustaceans, fish, algae, cnidarians, and protists (ciliates, radiolarians, other dinoflagellates). The troph ...

.

Although classified as eukaryotes

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

, the dinoflagellate nuclei are not characteristically eukaryotic, as some of them lack histones

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

and nucleosomes

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a spool. The nucleosome is the fundamen ...

, and maintain continually condensed chromosomes during mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

. The dinoflagellate nucleus was termed ‘mesokaryotic’ by Dodge (1966), due to its possession of intermediate characteristics between the coiled DNA areas of prokaryotic bacteria and the well-defined eukaryotic nucleus. This group, however, does contain typically eukaryotic organelles

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

, such as Golgi bodies, mitochondria, and chloroplasts.

Jakob Schiller (1931–1937) provided a description of all the species, both marine and freshwater, known at that time. Later, Alain Sournia (1973, 1978, 1982, 1990, 1993) listed the new taxonomic entries published after Schiller (1931–1937). Sournia (1986) gave descriptions and illustrations of the marine genera of dinoflagellates, excluding information at the species level. The latest index is written by Gómez.

Identification

English-language taxonomic monographs covering large numbers of species are published for the Gulf of Mexico, the Indian Ocean, the British Isles, the Mediterranean and the North Sea. The main source for identification of freshwater dinoflagellates is the ''Süsswasser Flora''.Calcofluor-white Calcofluor-white or CFW is a fluorescent blue dye used in biology and textiles. It binds to 1-3 beta and 1-4 beta polysaccharides of chitin and cellulose that are present in cell walls on fungi, plants, and algae. In plant cell biology research, it ...

can be used to stain thecal plates in armoured dinoflagellates.

Ecology and physiology

Habitats

Dinoflagellates are found in all aquatic environments: marine, brackish, and fresh water, including in snow or ice. They are also common in benthic environments and sea ice.Endosymbionts

AllZooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae is a colloquial term for single-celled dinoflagellates that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including demosponges, corals, jellyfish, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthellae are in the genus ''Sy ...

are dinoflagellates and most of them are members within Symbiodiniaceae (e.g. the genus ''Symbiodinium

: ''This is about the genus sometimes called Zoox. For the company, see Zoox (company)''

''Symbiodinium'' is a genus of dinoflagellates that encompasses the largest and most prevalent group of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates known. These unicellul ...

''). The association between ''Symbiodinium'' and reef-building coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and sec ...

s is widely known. However, endosymbiontic Zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae is a colloquial term for single-celled dinoflagellates that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including demosponges, corals, jellyfish, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthellae are in the genus ''Sy ...

inhabit a great number of other invertebrates and protists, for example many sea anemones

Sea anemones are a group of predatory marine invertebrates of the order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classified in the phylum Cnidaria, ...

, jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella- ...

, nudibranchs

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs which shed their shells after their larval stage. They are noted for their often extraordinary colours and striking forms, and they have been given colourful nicknames to match, ...

, the giant clam ''Tridacna

''Tridacna'' is a genus of large saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs in the subfamily Tridacninae, the giant clams. They have heavy shells, fluted with 4 to 6 folds. The mantle is brightly coloured. They inhabit shallow waters of coral re ...

'', and several species of radiolarians

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are protozoa of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The el ...

and foraminiferans

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly an ...

. Many extant dinoflagellates are parasites

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted structurally to this way of lif ...

(here defined as organisms that eat their prey from the inside, i.e. endoparasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

, or that remain attached to their prey for longer periods of time, i.e. ectoparasites). They can parasitize animal or protist hosts. ''Protoodinium, Crepidoodinium, Piscinoodinium'', and ''Blastodinium'' retain their plastids while feeding on their zooplanktonic or fish hosts. In most parasitic dinoflagellates, the infective stage resembles a typical motile dinoflagellate cell.

Nutritional strategies

Three nutritional strategies are seen in dinoflagellates:phototroph

Phototrophs () are organisms that carry out photon capture to produce complex organic compounds (e.g. carbohydrates) and acquire energy. They use the energy from light to carry out various cellular metabolic processes. It is a common misconcep ...

y, mixotroph A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comp ...

y, and heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

y. Phototrophs can be photoautotroph Photoautotrophs are organisms that use light energy and inorganic carbon to produce organic materials. Eukaryotic photoautotrophs absorb energy through the chlorophyll molecules in their chloroplasts while prokaryotic photoautotrophs use chlorophyll ...

s or auxotrophs. Mixotrophic dinoflagellates are photosynthetically active, but are also heterotrophic. Facultative mixotrophs, in which autotrophy or heterotrophy is sufficient for nutrition, are classified as amphitrophic. If both forms are required, the organisms are mixotrophic ''sensu stricto''. Some free-living dinoflagellates do not have chloroplasts, but host a phototrophic endosymbiont. A few dinoflagellates may use alien chloroplasts (cleptochloroplasts), obtained from food (kleptoplasty

Kleptoplasty or kleptoplastidy is a symbiosis, symbiotic phenomenon whereby plastids, notably chloroplasts from algae, are sequestered by host organisms. The word is derived from ''Kleptes'' (κλέπτης) which is Greek language, Greek for thie ...

). Some dinoflagellates may feed on other organisms as predators or parasites.

Food inclusions contain bacteria, bluegreen algae, small dinoflagellates, diatoms, ciliates, and other dinoflagellates.

Mechanisms of capture and ingestion in dinoflagellates are quite diverse. Several dinoflagellates, both thecate (e.g. ''Ceratium hirundinella'', ''Peridinium globulus'') and nonthecate (e.g. ''Oxyrrhis marina'', ''Gymnodinium'' sp. and ''Kofoidinium'' spp.), draw prey to the sulcal region of the cell (either via water currents set up by the flagella or via pseudopodial extensions) and ingest the prey through the sulcus. In several ''Protoperidinium'' spp., e.g. ''P. conicum'', a large feeding veil—a pseudopod called the pallium—is extruded to capture prey which is subsequently digested extracellularly (= pallium-feeding). ''Oblea'', ''Zygabikodinium'', and ''Diplopsalis'' are the only other dinoflagellate genera known to use this particular feeding mechanism.

''Katodinium (Gymnodinium) fungiforme'', commonly found as a contaminant in algal or ciliate cultures, feeds by attaching to its prey and ingesting prey cytoplasm through an extensible peduncle. Two related species, polykrikos kofoidii and neatodinium, shoots out a harpoon-like organelle to capture prey.

Some mixotrophic dinoflagellates are able to produce neurotoxins that have anti-grazing effects on larger copepods and enhance the ability of the dinoflagellate to prey upon larger copepods. Toxic strains of ''K. veneficum'' produce karlotoxin that kills predators who ingest them, thus reducing predatory populations and allowing blooms of both toxic and non-toxic strains of ''K. veneficum''. Further, the production of karlotoxin enhances the predatory ability of ''K. veneficum'' by immobilizing its larger prey. ''K. arminger'' are more inclined to prey upon copepods by releasing a potent neurotoxin that immobilizes its prey upon contact. When ''K. arminger'' are present in large enough, they are able to cull whole populations of its copepods prey.

The feeding mechanisms of the oceanic dinoflagellates remain unknown, although pseudopodial extensions were observed in ''Podolampas bipes''.

Blooms

Introduction

Dinoflagellate blooms are generally unpredictable, short, with low species diversity, and with little species succession. The low species diversity can be due to multiple factors. One way a lack of diversity may occur in a bloom is through a reduction in predation and a decreased competition. The first may be achieved by having predators reject the dinoflagellate, by, for example, decreasing the amount of food it can eat. This additionally helps prevent a future increase in predation pressure by cause predators that reject it to lack the energy to breed. A species can then inhibit the growth of its competitors, thus achieving dominance.Harmful algal blooms

Dinoflagellates sometimes bloom in concentrations of more than a million cells per millilitre. Under such circumstances, they can produce toxins (generally calleddinotoxin Dinotoxins are a group of toxins which are produced by flagellate, aquatic, unicellular protists called dinoflagellates. Dinotoxin was coined by Hardy and Wallace in 2012 as a general term for the variety of toxins produced by dinoflagellates. Din ...

s) in quantities capable of killing fish and accumulating in filter feeders such as shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater envir ...

, which in turn may be passed on to people who eat them. This phenomenon is called a red tide

A harmful algal bloom (HAB) (or excessive algae growth) is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural phycotoxin, algae-produced toxins, mechanical damage to other organisms, or by other means. HABs are ...

, from the color the bloom imparts to the water. Some colorless dinoflagellates may also form toxic blooms, such as ''Pfiesteria

''Pfiesteria'' is a genus of heterotrophic dinoflagellates that has been associated with harmful algal blooms and fish kills. ''Pfiesteria'' complex organisms (PCOs) were claimed to be responsible for large fish kills in the 1980s and 1990s on th ...

''. Some dinoflagellate blooms are not dangerous. Bluish flickers visible in ocean water at night often come from blooms of bioluminescent

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorganisms including ...

dinoflagellates, which emit short flashes of light when disturbed.

A red tide occurs because dinoflagellates are able to reproduce rapidly and copiously as a result of the abundant nutrients in the water. Although the resulting red waves are an interesting visual phenomenon, they contain

A red tide occurs because dinoflagellates are able to reproduce rapidly and copiously as a result of the abundant nutrients in the water. Although the resulting red waves are an interesting visual phenomenon, they contain toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

s that not only affect all marine life in the ocean, but the people who consume them, as well. A specific carrier is shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater envir ...

. This can introduce both nonfatal and fatal illnesses. One such poison is saxitoxin

Saxitoxin (STX) is a potent neurotoxin and the best-known paralytic shellfish toxin (PST). Ingestion of saxitoxin by humans, usually by consumption of shellfish contaminated by toxic algal blooms, is responsible for the illness known as paralytic ...

, a powerful paralytic

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function in both developing and mature ner ...

.

Human inputs of phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

further encourage these red tides, so strong interest exists in learning more about dinoflagellates, from both medical and economic perspectives. Dinoflagellates are known to be particularly capable of scavenging dissolved organic phosphorus for P-nutrient, several HAS species have been found to be highly versatile and mechanistically diversified in utilizing different types of DOPs. The ecology of harmful algal bloom

A harmful algal bloom (HAB) (or excessive algae growth) is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural algae-produced toxins, mechanical damage to other organisms, or by other means. HABs are sometimes ...

s is extensively studied.

Bioluminescence

At night, water can have an appearance of sparkling light due to the bioluminescence of dinoflagellates. More than 18 genera of dinoflagellates are bioluminescent, and the majority of them emit a blue-green light. These species contain

At night, water can have an appearance of sparkling light due to the bioluminescence of dinoflagellates. More than 18 genera of dinoflagellates are bioluminescent, and the majority of them emit a blue-green light. These species contain scintillons

Scintillons are small structures in cytoplasm that produce light. Among bioluminescent organisms, only dinoflagellates have scintillons.

Description Dinoflagellate light production

Marine dinoflagellates at night can emit blue light by biolumi ...

, individual cytoplasmic bodies (about 0.5 µm in diameter) distributed mainly in the cortical region of the cell, outpockets of the main cell vacuole. They contain dinoflagellate luciferase

Dinoflagellate luciferase (, ''Gonyaulax luciferase'') is a specific luciferase, an enzyme with systematic name ''dinoflagellate-luciferin:oxygen 132-oxidoreductase''.

Dinoflagellate luciferase reaction.JPG

: ''dinoflagellate'' luciferin + O2 ...

, the main enzyme involved in dinoflagellate bioluminescence, and luciferin

Luciferin (from the Latin ''lucifer'', "light-bearer") is a generic term for the light-emitting compound found in organisms that generate bioluminescence. Luciferins typically undergo an enzyme-catalyzed reaction with molecular oxygen. The result ...

, a chlorophyll-derived tetrapyrrole ring that acts as the substrate to the light-producing reaction. The luminescence occurs as a brief (0.1 sec) blue flash (max 476 nm) when stimulated, usually by mechanical disturbance. Therefore, when mechanically stimulated—by boat, swimming, or waves, for example—a blue sparkling light can be seen emanating from the sea surface.

Dinoflagellate bioluminescence is controlled by a circadian clock and only occurs at night. Luminescent and nonluminescent strains can occur in the same species. The number of scintillons is higher during night than during day, and breaks down during the end of the night, at the time of maximal bioluminescence.

The luciferin-luciferase reaction responsible for the bioluminescence is pH sensitive. When the pH drops, luciferase changes its shape, allowing luciferin, more specifically tetrapyrrole, to bind. Dinoflagellates can use bioluminescence as a defense mechanism. They can startle their predators by their flashing light or they can ward off potential predators by an indirect effect such as the "burglar alarm". The bioluminescence attracts attention to the dinoflagellate and its attacker, making the predator more vulnerable to predation from higher trophic levels.

Bioluminescent dinoflagellate ecosystem bays are among the rarest and most fragile, with the most famous ones being the Bioluminescent Bay in La Parguera, Lajas, Puerto Rico; Mosquito Bay in Vieques, Puerto Rico

Vieques (; ), officially Isla de Vieques, is an island and municipality of Puerto Rico, in the northeastern Caribbean, part of an island grouping sometimes known as the Spanish Virgin Islands. Vieques is part of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, ...

; and Las Cabezas de San Juan Reserva Natural Fajardo, Puerto Rico

Fajardo (, ) is a town and municipality -Fajardo Combined Statistical Area.

Fajardo is the hub of much of the recreational boating in Puerto Rico and a popular launching port to Culebra, Vieques, and the U.S. and British Virgin Islands. It is ...

. Also, a bioluminescent lagoon is near Montego Bay, Jamaica, and bioluminescent harbors surround Castine, Maine. Within the United States, Central Florida is home to the Indian River Lagoon which is abundant with dinoflagellates in the summer and bioluminescent ctenophore in the winter.

Lipid and sterol production

Dinoflagellates produce characteristic lipids and sterols. One of these sterols is typical of dinoflagellates and is called dinosterol.Transport

Dinoflagellate theca can sink rapidly to the seafloor in marine snow.Life cycle

Introduction

Dinoflagellates have a Biological life cycle#Haplontic life cycle, haplontic life cycle, with the possible exception of ''Noctiluca'' and its relatives. The life cycle usually involves asexual reproduction by means of mitosis, either through desmoschisis or eleuteroschisis. More complex life cycles occur, more particularly with parasitic dinoflagellates. Sexual reproduction also occurs, though this mode of reproduction is only known in a small percentage of dinoflagellates. This takes place by fusion of two individuals to form a zygote, which may remain mobile in typical dinoflagellate fashion and is then called a planozygote. This zygote may later form a resting stage or hypnozygote, which is called a dinoflagellate cyst ordinocyst

Dinocysts or dinoflagellate cysts are typically 15 to 100 µm in diameter and produced by around 15–20% of living dinoflagellates as a dormant, zygotic stage of their lifecycle, which can accumulate in the sediments as microfossils. Organic- ...

. After (or before) germination of the cyst, the hatchling undergoes meiosis to produce new haploid cells. Dinoflagellates appear to be capable of carrying out several DNA repair processes that can deal with different types of DNA damage (naturally occurring), DNA damage.

Dinoflagellate cysts

The life cycle of many dinoflagellates includes at least one nonflagellated benthic stage as a Microbial cyst, cyst. Different types of dinoflagellate cysts are mainly defined based on morphological (number and type of layers in the cell wall) and functional (long- or short-term endurance) differences. These characteristics were initially thought to clearly distinguish Pellicle (biology), pellicle (thin-walled) cysts from Resting spore, resting (double-walled) dinoflagellate cysts. The former were considered short-term (temporal) and the latter long-term (resting) cysts. However, during the last two decades further knowledge has highlighted the great intricacy of dinoflagellate life histories. More than 10% of the approximately 2000 known marine dinoflagellate species produce cysts as part of their life cycle (see diagram on the right). These benthic phases play an important role in the ecology of the species, as part of a planktonic-benthic link in which the cysts remain in the sediment layer during conditions unfavorable for vegetative growth and, from there, reinoculate the water column when favorable conditions are restored.

Indeed, during dinoflagellate evolution the need to adapt to fluctuating environments and/or to seasonality is thought to have driven the development of this life cycle stage. Most protists form dormant cysts in order to withstand starvation and UV damage. However, there are enormous differences in the main phenotypic, physiological and resistance properties of each dinoflagellate species cysts. Unlike in higher plants most of this variability, for example in dormancy periods, has not been proven yet to be attributed to latitude adaptation or to depend on other life cycle traits. Thus, despite recent advances in the understanding of the life histories of many dinoflagellate species, including the role of cyst stages, many gaps remain in knowledge about their origin and functionality.

Recognition of the capacity of dinoflagellates to encyst dates back to the early 20th century, in biostratigraphic studies of fossil dinoflagellate cysts. Paul Friedrich Reinsch, Paul Reinsch was the first to identify cysts as the fossilized remains of dinoflagellates. Later, cyst formation from gamete fusion was reported, which led to the conclusion that encystment is associated with sexual reproduction. These observations also gave credence to the idea that microalgal encystment is essentially a process whereby zygotes prepare themselves for a dormant period. Because the resting cysts studied until that time came from sexual processes, dormancy was associated with sexuality, a presumption that was maintained for many years. This attribution was coincident with evolutionary theories about the origin of eukaryotic cell fusion and sexuality, which postulated advantages for species with diploid resting stages, in their ability to withstand nutrient stress and mutational UV radiation through recombinational repair, and for those with haploid vegetative stages, as asexual division doubles the number of cells. Nonetheless, certain environmental conditions may limit the advantages of recombination and sexuality, such that in fungi, for example, complex combinations of haploid and diploid cycles have evolved that include asexual and sexual resting stages.

However, in the general life cycle of cyst-producing dinoflagellates as outlined in the 1960s and 1970s, resting cysts were assumed to be the fate of sexuality, which itself was regarded as a response to stress or unfavorable conditions. Sexuality involves the fusion of haploid gametes from motile planktonic vegetative stages to produce diploid planozygotes that eventually form cysts, or hypnozygotes, whose germination is subject to both endogenous and exogenous controls. Endogenously, a species-specific physiological maturation minimum period (dormancy) is mandatory before germination can occur. Thus, hypnozygotes were also referred to as “resting” or “resistant” cysts, in reference to this physiological trait and their capacity following dormancy to remain viable in the sediments for long periods of time. Exogenously, germination is only possible within a window of favorable environmental conditions.

Yet, with the discovery that planozygotes were also able to divide it became apparent that the complexity of dinoflagellate life cycles was greater than originally thought. Following corroboration of this behavior in several species, the capacity of dinoflagellate sexual phases to restore the vegetative phase, bypassing cyst formation, became well accepted. Further, in 2006 Kremp and Parrow showed the dormant resting cysts of the Baltic cold water dinoflagellates ''Scrippsiella hangoei'' and ''Gymnodinium'' sp. were formed by the direct encystment of haploid vegetative cells, i.e., asexually. In addition, for the zygotic cysts of ''Pfiesteria piscicida'' dormancy was not essential.

More than 10% of the approximately 2000 known marine dinoflagellate species produce cysts as part of their life cycle (see diagram on the right). These benthic phases play an important role in the ecology of the species, as part of a planktonic-benthic link in which the cysts remain in the sediment layer during conditions unfavorable for vegetative growth and, from there, reinoculate the water column when favorable conditions are restored.

Indeed, during dinoflagellate evolution the need to adapt to fluctuating environments and/or to seasonality is thought to have driven the development of this life cycle stage. Most protists form dormant cysts in order to withstand starvation and UV damage. However, there are enormous differences in the main phenotypic, physiological and resistance properties of each dinoflagellate species cysts. Unlike in higher plants most of this variability, for example in dormancy periods, has not been proven yet to be attributed to latitude adaptation or to depend on other life cycle traits. Thus, despite recent advances in the understanding of the life histories of many dinoflagellate species, including the role of cyst stages, many gaps remain in knowledge about their origin and functionality.

Recognition of the capacity of dinoflagellates to encyst dates back to the early 20th century, in biostratigraphic studies of fossil dinoflagellate cysts. Paul Friedrich Reinsch, Paul Reinsch was the first to identify cysts as the fossilized remains of dinoflagellates. Later, cyst formation from gamete fusion was reported, which led to the conclusion that encystment is associated with sexual reproduction. These observations also gave credence to the idea that microalgal encystment is essentially a process whereby zygotes prepare themselves for a dormant period. Because the resting cysts studied until that time came from sexual processes, dormancy was associated with sexuality, a presumption that was maintained for many years. This attribution was coincident with evolutionary theories about the origin of eukaryotic cell fusion and sexuality, which postulated advantages for species with diploid resting stages, in their ability to withstand nutrient stress and mutational UV radiation through recombinational repair, and for those with haploid vegetative stages, as asexual division doubles the number of cells. Nonetheless, certain environmental conditions may limit the advantages of recombination and sexuality, such that in fungi, for example, complex combinations of haploid and diploid cycles have evolved that include asexual and sexual resting stages.

However, in the general life cycle of cyst-producing dinoflagellates as outlined in the 1960s and 1970s, resting cysts were assumed to be the fate of sexuality, which itself was regarded as a response to stress or unfavorable conditions. Sexuality involves the fusion of haploid gametes from motile planktonic vegetative stages to produce diploid planozygotes that eventually form cysts, or hypnozygotes, whose germination is subject to both endogenous and exogenous controls. Endogenously, a species-specific physiological maturation minimum period (dormancy) is mandatory before germination can occur. Thus, hypnozygotes were also referred to as “resting” or “resistant” cysts, in reference to this physiological trait and their capacity following dormancy to remain viable in the sediments for long periods of time. Exogenously, germination is only possible within a window of favorable environmental conditions.

Yet, with the discovery that planozygotes were also able to divide it became apparent that the complexity of dinoflagellate life cycles was greater than originally thought. Following corroboration of this behavior in several species, the capacity of dinoflagellate sexual phases to restore the vegetative phase, bypassing cyst formation, became well accepted. Further, in 2006 Kremp and Parrow showed the dormant resting cysts of the Baltic cold water dinoflagellates ''Scrippsiella hangoei'' and ''Gymnodinium'' sp. were formed by the direct encystment of haploid vegetative cells, i.e., asexually. In addition, for the zygotic cysts of ''Pfiesteria piscicida'' dormancy was not essential.

Genomics

One of the most striking features of dinoflagellates is the large amount of cellular DNA that they contain. Most eukaryotic algae contain on average about 0.54 pg DNA/cell, whereas estimates of dinoflagellate DNA content range from 3–250 pg/cell, corresponding to roughly 3000–215 000 Mb (in comparison, the haploid human genome is 3180 Mb and hexaploid ''Triticum'' wheat is 16 000 Mb). Polyploidy or polyteny may account for this large cellular DNA content, but earlier studies of DNA reassociation kinetics and recent genome analyses do not support this hypothesis. Rather, this has been attributed, hypothetically, to the rampant retroposition found in dinoflagellate genomes. In addition to their disproportionately large genomes, dinoflagellate nuclei are unique in their morphology, regulation, and composition. Their DNA is so tightly packed that exactly how many chromosomes they have is still uncertain. The dinoflagellates share an unusual mitochondrial genome organisation with their relatives, theApicomplexa

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia) are a large phylum of parasitic alveolates. Most of them possess a unique form of organelle that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast, and an apical complex structure. T ...

. Both groups have very reduced mitochondrial genomes (around 6 kilobases (kb) in the Apicomplexa vs ~16kb for human mitochondria). One species, ''Amoebophrya ceratii'', has lost its mitochondrial genome completely, yet still has functional mitochondria. The genes on the dinoflagellate genomes have undergone a number of reorganisations, including massive genome amplification and recombination which have resulted in multiple copies of each gene and gene fragments linked in numerous combinations. Loss of the standard stop codons, trans-splicing of mRNAs for the mRNA of cox3, and extensive RNA editing recoding of most genes has occurred. The reasons for this transformation are unknown. In a small group of dinoflagellates, called ‘dinotoms’ (Durinskia

and Kryptoperidinium), the endosymbionts (diatoms) still have mitochondria, making them the only organisms with two evolutionarily distinct mitochondria.

In most of the species, the plastid genome consist of just 14 genes.

The DNA of the plastid in the peridinin-containing dinoflagellates is contained in a series of small circles called minicircles. Each circle contains one or two polypeptide genes. The genes for these polypeptides are chloroplast-specific because their homologs from other photosynthetic eukaryotes are exclusively encoded in the chloroplast genome. Within each circle is a distinguishable 'core' region. Genes are always in the same orientation with respect to this core region.

In terms of DNA barcoding, ITS sequences can be used to identify species, where a genetic distance of p≥0.04 can be used to delimit species, which has been successfully applied to resolve long-standing taxonomic confusion as in the case of resolving the Alexandrium tamarense complex into five species. A recent study revealed a substantial proportion of dinoflagellate genes encode for unknown functions, and that these genes could be conserved and lineage-specific.

Evolutionary history