Der Ring Des Nibelung on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language

The plot revolves around a magic ring that grants the power to rule the world, forged by the

The plot revolves around a magic ring that grants the power to rule the world, forged by the

On King Ludwig's insistence, and over Wagner's objections, "special previews" of ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Walküre'' were given at the National Theatre in Munich, before the rest of the ''Ring''. Thus, ''Das Rheingold'' premiered on 22 September 1869, and ''Die Walküre'' on 26 June 1870. Wagner subsequently delayed announcing his completion of ''

On King Ludwig's insistence, and over Wagner's objections, "special previews" of ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Walküre'' were given at the National Theatre in Munich, before the rest of the ''Ring''. Thus, ''Das Rheingold'' premiered on 22 September 1869, and ''Die Walküre'' on 26 June 1870. Wagner subsequently delayed announcing his completion of ''

Perhaps the most famous modern production was the centennial production of 1976, the ''

Perhaps the most famous modern production was the centennial production of 1976, the ''

The

The

The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung

'. Penguin UK, . * Spotts, Frederick, (1999)

Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival

'. Yale University Press .

epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film with heroic elements

Epic or EPIC may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

music drama

is a German word that means a unity of prose and music. Initially coined by Theodor Mundt in 1833, it was most notably used by Richard Wagner, along with Gesamtkunstwerk, to define his operas.

Usage

Mundt formulated his definition explicitly ...

s composed by Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend

Germanic heroic legend (german: germanische Heldensage) is the heroic literary tradition of the Germanic-speaking peoples, most of which originates or is set in the Migration Period (4th-6th centuries AD). Stories from this time period, to whic ...

, namely Norse legendary saga

A legendary saga or ''fornaldarsaga'' (literally, "story/history of the ancient era") is a Norse saga that, unlike the Icelanders' sagas, takes place before the settlement of Iceland.The article ''Fornaldarsagor'' in ''Nationalencyklopedin'' (1991) ...

s and the ''Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poetry, epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition ...

''. The composer termed the cycle a "Bühnenfestspiel" (stage festival play), structured in three days preceded by a ("preliminary evening"). It is often referred to as the ''Ring'' cycle, Wagner's ''Ring'', or simply ''The Ring''.

Wagner wrote the libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

and music over the course of about twenty-six years, from 1848 to 1874. The four parts that constitute the ''Ring'' cycle are, in sequence:

* ''Das Rheingold

''Das Rheingold'' (; ''The Rhinegold''), WWV 86A, is the first of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National ...

'' (''The Rhinegold'')

* ''Die Walküre

(; ''The Valkyrie''), WWV 86B, is the second of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National Theatre Munich on ...

'' (''The Valkyrie'')

* ''Siegfried

Siegfried is a German-language male given name, composed from the Germanic elements ''sig'' "victory" and ''frithu'' "protection, peace".

The German name has the Old Norse cognate ''Sigfriðr, Sigfrøðr'', which gives rise to Swedish ''Sigfrid' ...

''

* ''Götterdämmerung

' (; ''Twilight of the Gods''), WWV 86D, is the last in Richard Wagner's cycle of four music dramas titled (''The Ring of the Nibelung'', or ''The Ring Cycle'' or ''The Ring'' for short). It received its premiere at the on 17 August 1876, as p ...

'' (''Twilight of the Gods'')

Individual works of the sequence are often performed separately, and indeed the operas contain dialogues that mention events in the previous operas, so that a viewer could watch any of them without having watched the previous parts and still understand the plot. However, Wagner intended them to be performed in series. The first performance as a cycle opened the first Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

in 1876, beginning with ''Das Rheingold'' on 13 August and ending with ''Götterdämmerung'' on 17 August. Opera stage director Anthony Freud stated that ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' "marks the high-water mark of our art form, the most massive challenge any opera company can undertake."

Title

Wagner's title is most literally rendered in English as ''The Ring of the Nibelung''. TheNibelung

The term Nibelung (German) or Niflungr (Old Norse) is a personal or clan name with several competing and contradictory uses in Germanic heroic legend. It has an unclear etymology, but is often connected to the root ''nebel'', meaning mist. The te ...

of the title is the dwarf

Dwarf or dwarves may refer to:

Common uses

*Dwarf (folklore), a being from Germanic mythology and folklore

* Dwarf, a person or animal with dwarfism

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Dwarf (''Dungeons & Dragons''), a humanoid ...

Alberich, and the ring in question is the one he fashions from the Rhine Gold. The title therefore denotes "Alberich's Ring".

Content

The cycle is a work of extraordinary scale. A full performance of the cycle takes place over four nights at the opera, with a total playing time of about 15 hours, depending on the conductor's pacing. The first and shortest work, ''Das Rheingold'', has no interval and is one continuous piece of music typically lasting around two and a half hours, while the final and longest, ''Götterdämmerung'', takes up to five hours, excluding intervals. The cycle is modelled after ancient Greek dramas that were presented as three tragedies and onesatyr play

The satyr play is a form of Attic theatre performance related to both comedy and tragedy. It preserves theatrical elements of dialogue, actors speaking verse, a chorus that dances and sings, masks and costumes. Its relationship to tragedy is stro ...

. The ''Ring'' proper begins with ''Die Walküre'' and ends with ''Götterdämmerung'', with ''Rheingold'' as a prelude. Wagner called ''Das Rheingold'' a ''Vorabend'' or "Preliminary Evening", and ''Die Walküre'', ''Siegfried'' and ''Götterdämmerung'' were subtitled First Day, Second Day and Third Day, respectively, of the trilogy proper.

The scale and scope of the story is epic. It follows the struggles of gods

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater ...

, hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or Physical strength, strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ...

es, and several mythical creatures over the eponymous magic ring that grants domination over the entire world. The drama and intrigue continue through three generations of protagonists, until the final cataclysm at the end of ''Götterdämmerung''.

The music of the cycle is thick and richly textured, and grows in complexity as the cycle proceeds. Wagner wrote for an orchestra of gargantuan proportions, including a greatly enlarged brass section with new instruments such as the Wagner tuba

The Wagner tuba is a four-valve brass instrument named after and commissioned by Richard Wagner. It combines technical features of both standard tubas and French horns, though despite its name, the Wagner tuba is more similar to the latter, and ...

, bass trumpet

The bass trumpet is a type of low trumpet which was first developed during the 1820s in Germany. It is usually pitched in 8' C or 9' B today, but is sometimes built in E and is treated as a transposing instrument sounding either an octave, a sixt ...

and contrabass trombone

The contrabass trombone (german: Kontrabassposaune, it, trombone contrabbasso) is the lowest instrument in the trombone family of brass instruments. First appearing built in 18′ B♭ an octave below the tenor trombone, since the late 20th cen ...

. Remarkably, he uses a chorus only relatively briefly, in acts 2 and 3 of ''Götterdämmerung'', and then mostly of men with just a few women. He eventually had a purpose-built theatre constructed, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus

The ''Bayreuth Festspielhaus'' or Bayreuth Festival Theatre (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspielhaus, ) is an opera house north of Bayreuth, Germany, built by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner and dedicated solely to the performa ...

, in which to perform this work. The theatre has a special stage that blends the huge orchestra with the singers' voices, allowing them to sing at a natural volume. The result was that the singers did not have to strain themselves vocally during the long performances.

List of characters

Story

The plot revolves around a magic ring that grants the power to rule the world, forged by the

The plot revolves around a magic ring that grants the power to rule the world, forged by the Nibelung

The term Nibelung (German) or Niflungr (Old Norse) is a personal or clan name with several competing and contradictory uses in Germanic heroic legend. It has an unclear etymology, but is often connected to the root ''nebel'', meaning mist. The te ...

dwarf

Dwarf or dwarves may refer to:

Common uses

*Dwarf (folklore), a being from Germanic mythology and folklore

* Dwarf, a person or animal with dwarfism

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Dwarf (''Dungeons & Dragons''), a humanoid ...

Alberich from gold he stole from the Rhine maidens in the river Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

. With the assistance of the god Loge, Wotan – the chief of the gods

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater ...

– steals the ring from Alberich, but is forced to hand it over to the giant

In folklore, giants (from Ancient Greek: '' gigas'', cognate giga-) are beings of human-like appearance, but are at times prodigious in size and strength or bear an otherwise notable appearance. The word ''giant'' is first attested in 1297 fr ...

s Fafner and Fasolt in payment for building the home of the gods, Valhalla

In Norse mythology Valhalla (;) is the anglicised name for non, Valhǫll ("hall of the slain").Orchard (1997:171–172) It is described as a majestic hall located in Asgard and presided over by the god Odin. Half of those who die in combat e ...

, or they will take Freia, who provides the gods with the golden apples that keep them young. Wotan's schemes to regain the ring, spanning generations, drive much of the action in the story. His grandson, the mortal

Mortal means susceptible to death; the opposite of immortality, immortal.

Mortal may also refer to:

* Mortal (band), a Christian industrial band

* The Mortal, Sakurai Atsushi's project band

* Mortal (novel), ''Mortal'' (novel), a science fiction ...

Siegfried, wins the ring by slaying Fafner (who slew Fasolt for the ring) – as Wotan intended – but is eventually betrayed and slain as a result of the intrigues of Alberich's son Hagen, who wants the ring for himself. Finally, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde – Siegfried's lover and Wotan's daughter who lost her immortality for defying her father in an attempt to save Siegfried's father Sigmund – returns the ring to the Rhine maidens as she commits suicide on Siegfried's funeral pyre. Hagen is drowned as he attempts to recover the ring. In the process, the gods and Valhalla are destroyed.

Details of the storylines can be found in the articles on each music drama.

Wagner created the story of the ''Ring'' by fusing elements from many German and Scandinavian myths and folk-tales. The Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

''Edda

"Edda" (; Old Norse ''Edda'', plural ''Eddur'') is an Old Norse term that has been attributed by modern scholars to the collective of two Medieval Icelandic literary works: what is now known as the ''Prose Edda'' and an older collection of poem ...

'' supplied much of the material for ''Das Rheingold'', while ''Die Walküre'' was largely based on the ''Völsunga saga

The ''Völsunga saga'' (often referred to in English as the ''Volsunga Saga'' or ''Saga of the Völsungs'') is a legendary saga, a late 13th-century poetic rendition in Old Norse of the origin and decline of the Völsung clan (including the stor ...

''. ''Siegfried'' contains elements from the Eddur, the ''Völsunga saga'' and '' Thidrekssaga''. The final ''Götterdämmerung'' draws from the 12th-century German poem, the ''Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poetry, epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition ...

'', which appears to have been the original inspiration for the ''Ring''.

''The Ring'' has been the subject of myriad interpretations. For example, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, in '' The Perfect Wagnerite'', argues for a view of ''The Ring'' as an essentially socialist critique of industrial society

In sociology, industrial society is a society driven by the use of technology and machinery to enable mass production, supporting a large population with a high capacity for division of labour. Such a structure developed in the Western world i ...

and its abuses. Robert Donington

Robert Donington (4 May 1907 – 20 January 1990) was a British musicologist and instrumentalist influential in the early music movement and in Wagner studies.

He was educated at St Paul's School, London, and studied at the University of Oxfor ...

in ''Wagner's Ring And Its Symbols'' interprets it in terms of Jungian psychology

Analytical psychology ( de , Analytische Psychologie, sometimes translated as analytic psychology and referred to as Jungian analysis) is a term coined by Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, to describe research into his new "empirical science" ...

, as an account of the development of unconscious

Unconscious may refer to:

Physiology

* Unconsciousness, the lack of consciousness or responsiveness to people and other environmental stimuli

Psychology

* Unconscious mind, the mind operating well outside the attention of the conscious mind a ...

archetype

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that ot ...

s in the mind, leading towards individuation

The principle of individuation, or ', describes the manner in which a thing is identified as distinct from other things.

The concept appears in numerous fields and is encountered in works of Leibniz, Carl Gustav Jung, Gunther Anders, Gilbert Sim ...

.

Concept

In his earlier operas (up to and including ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in Germany, German Arthurian literature. The son of Percival, Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which fi ...

'') Wagner's style had been based, rather than on the Italian style of opera, on the German style as developed by Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria Friedrich Ernst von Weber (18 or 19 November 17865 June 1826) was a German composer, conductor, virtuoso pianist, guitarist, and critic who was one of the first significant composers of the Romantic era. Best known for his opera ...

, with elements of the grand opera

Grand opera is a genre of 19th-century opera generally in four or five acts, characterized by large-scale casts and orchestras, and (in their original productions) lavish and spectacular design and stage effects, normally with plots based on o ...

style of Giacomo Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera ''Robert le di ...

. However he came to be dissatisfied with such a format as a means of artistic expression. He expressed this clearly in his essay 'A Communication to My Friends "Eine Mitteilung an meine Freunde", usually referred to in English by its translated title (from German language, German) of "A Communication to My Friends", is an extensive autobiography, autobiographical work by Richard Wagner, published in 1851, ...

', (1851) in which he condemned the majority of modern artists, in painting and in music, as "feminine ... the world of art close fenced from Life, in which Art plays with herself.' Where however the impressions of Life produce an overwhelming 'poetic force', we find the 'masculine, the generative path of Art'.

Wagner unfortunately found that his audiences were not willing to follow where he led them:

Finally Wagner announces:

This is his first public announcement of the form of what would become the ''Ring'' cycle.

In accordance with the ideas expressed in his essays of the period 1849–51 (including the "Communication" but also "Opera and Drama

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a libretti ...

" and "The Artwork of the Future

"The Artwork of the Future" (german: Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft) is a long essay written by Richard Wagner, first published in 1849 in Leipzig, in which he sets out some of his ideals on the topics of art in general and music drama in particular.

...

"), the four parts of the ''Ring'' were originally conceived by Wagner to be free of the traditional operatic concepts of aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

and operatic chorus

Chorus may refer to:

Music

* Chorus (song) or refrain, line or lines that are repeated in music or in verse

* Chorus effect, the perception of similar sounds from multiple sources as a single, richer sound

* Chorus form, song in which all verse ...

. The Wagner scholar Curt von Westernhagen identified three important problems discussed in "Opera and Drama" which were particularly relevant to the ''Ring'' cycle: the problem of unifying verse stress with melody; the disjunctions caused by formal arias in dramatic structure, and the way in which opera music could be organised on a different basis of organic growth and modulation

In electronics and telecommunications, modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform, called the ''carrier signal'', with a separate signal called the ''modulation signal'' that typically contains informatio ...

; and the function of musical motifs in linking elements of the plot whose connections might otherwise be inexplicit. This became known as the leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglici ...

technique (see below), although Wagner himself did not use this word.

However, Wagner relaxed some aspects of his self-imposed restrictions somewhat as the work progressed. As George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

sardonically (and slightly unfairly) noted of the last opera ''Götterdämmerung'':

Music

Leitmotifs

As a significant element in the ''Ring'' and his subsequent works, Wagner adopted the use ofleitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglici ...

s, which are recurring themes or harmonic

A harmonic is a wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'', the frequency of the original periodic signal, such as a sinusoidal wave. The original signal is also called the ''1st harmonic'', the ...

progressions. They musically denote an action, object, emotion, character, or other subject mentioned in the text or presented onstage. Wagner referred to them in "Opera and Drama" as "guides-to-feeling", describing how they could be used to inform the listener of a musical or dramatic subtext to the action onstage in the same way as a Greek chorus

A Greek chorus, or simply chorus ( grc-gre, χορός, chorós), in the context of ancient Greek tragedy, comedy, satyr plays, and modern works inspired by them, is a homogeneous, non-individualised group of performers, who comment with a collect ...

did for the theatre of ancient Greece

Ancient Greek theatre was a theatrical culture that flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. The city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, was its centre, where the theatre was ...

.

Instrumentation

Wagner made significant innovations inorchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orc ...

in this work. He wrote for a very large orchestra, using the whole range of instruments used singly or in combination to express the great range of emotion and events of the drama. Wagner even commissioned the production of new instruments, including the Wagner tuba

The Wagner tuba is a four-valve brass instrument named after and commissioned by Richard Wagner. It combines technical features of both standard tubas and French horns, though despite its name, the Wagner tuba is more similar to the latter, and ...

, invented to fill a gap he found between the tone qualities of the horn

Horn most often refers to:

*Horn (acoustic), a conical or bell shaped aperture used to guide sound

** Horn (instrument), collective name for tube-shaped wind musical instruments

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various ...

and the trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the Standing wave, air column ...

, as well as variations of existing instruments, such as the bass trumpet

The bass trumpet is a type of low trumpet which was first developed during the 1820s in Germany. It is usually pitched in 8' C or 9' B today, but is sometimes built in E and is treated as a transposing instrument sounding either an octave, a sixt ...

and a contrabass trombone

The contrabass trombone (german: Kontrabassposaune, it, trombone contrabbasso) is the lowest instrument in the trombone family of brass instruments. First appearing built in 18′ B♭ an octave below the tenor trombone, since the late 20th cen ...

with a double slide. He also developed the "Wagner bell", enabling the bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuo ...

to reach the low A-natural, whereas normally B-flat is the instrument's lowest note. If such a bell is not to be used, then a contrabassoon

The contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon, is a larger version of the bassoon, sounding an octave lower. Its technique is similar to its smaller cousin, with a few notable differences.

Differences from the bassoon

The reed is consi ...

should be employed.

All four parts have a very similar instrumentation. The core ensemble of instruments are one piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the so ...

, three flutes

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

(third doubling second piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the so ...

), three oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

s, cor anglais

The cor anglais (, or original ; plural: ''cors anglais''), or English horn in North America, is a double-reed woodwind instrument in the oboe family. It is approximately one and a half times the length of an oboe, making it essentially an alto ...

(doubling fourth oboe), three soprano clarinet

A soprano clarinet is a clarinet that is higher in register than the basset horn or alto clarinet. The unmodified word ''clarinet'' usually refers to the B clarinet, which is by far the most common type. The term ''soprano'' also applies to th ...

s, one bass clarinet

The bass clarinet is a musical instrument of the clarinet family. Like the more common soprano B clarinet, it is usually pitched in B (meaning it is a transposing instrument on which a written C sounds as B), but it plays notes an octave bel ...

, three bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuo ...

s; eight horns Horns or The Horns may refer to:

* Plural of Horn (instrument), a group of musical instruments all with a horn-shaped bells

* The Horns (Colorado), a summit on Cheyenne Mountain

* ''Horns'' (novel), a dark fantasy novel written in 2010 by Joe Hill ...

(fifth through eight doubling Wagner tuba

The Wagner tuba is a four-valve brass instrument named after and commissioned by Richard Wagner. It combines technical features of both standard tubas and French horns, though despite its name, the Wagner tuba is more similar to the latter, and ...

s), three trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s, one bass trumpet, three tenor trombone

A tenor is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The low extreme for tenors is widel ...

s, one contrabass trombone

The contrabass trombone (german: Kontrabassposaune, it, trombone contrabbasso) is the lowest instrument in the trombone family of brass instruments. First appearing built in 18′ B♭ an octave below the tenor trombone, since the late 20th cen ...

(doubling bass trombone

The bass trombone (german: Bassposaune, it, trombone basso) is the bass instrument in the trombone family of brass instruments. Modern instruments are pitched in the same B♭ as the tenor trombone but with a larger bore, bell and mouthpiece to ...

), one contrabass tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th century, making it one of the ne ...

; a percussion section with 4 timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

(requiring two players), triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three Edge (geometry), edges and three Vertex (geometry), vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, an ...

, cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s, glockenspiel

The glockenspiel ( or , : bells and : set) or bells is a percussion instrument consisting of pitched aluminum or steel bars arranged in a keyboard layout. This makes the glockenspiel a type of metallophone, similar to the vibraphone.

The glo ...

, tam-tam

A gongFrom Indonesian and ms, gong; jv, ꦒꦺꦴꦁ ; zh, c=鑼, p=luó; ja, , dora; km, គង ; th, ฆ้อง ; vi, cồng chiêng; as, কাঁহ is a percussion instrument originating in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Gongs ...

; six harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

s and a string section consisting of 16 first and 16 second violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

s, 12 viola

The viola ( , also , ) is a string instrument that is bow (music), bowed, plucked, or played with varying techniques. Slightly larger than a violin, it has a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of ...

s, 12 cello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a Bow (music), bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), t ...

s, and 8 double bass

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or #Terminology, by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched Bow (music), bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox addit ...

es.

''Das Rheingold'' requires one bass drum

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter much greater than the drum's depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. Th ...

, one onstage harp and 18 onstage anvil

An anvil is a metalworking tool consisting of a large block of metal (usually forged or cast steel), with a flattened top surface, upon which another object is struck (or "worked").

Anvils are as massive as practical, because the higher th ...

s. ''Die Walküre'' requires one snare drum

The snare (or side drum) is a percussion instrument that produces a sharp staccato sound when the head is struck with a drum stick, due to the use of a series of stiff wires held under tension against the lower skin. Snare drums are often used ...

, one D clarinet

The E-flat (E) clarinet is a member of the clarinet family, smaller than the more common B clarinet and pitched a perfect fourth higher. It is typically considered the sopranino or piccolo member of the clarinet family and is a transposing inst ...

(played by the third clarinettist), and an on-stage steerhorn

The steerhorn (German: ''stierhorn'', also known in English as a cowhorn or bullhorn) is an extremely long medieval bugle horn. The instrument could be as much as 3 feet long. It was used from "antiquity" into the middle ages. The instrument ha ...

. ''Siegfried'' requires one onstage cor anglais and one onstage horn. ''Götterdämmerung'' requires a tenor drum A tenor drum is a membranophone without a snare. There are several types of tenor drums.

Early music

Early music tenor drums, or long drums, are cylindrical membranophone without snare used in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque music. They consi ...

, as well as five onstage horns and four onstage steerhorns, one of them to be blown by Hagen.

Tonality

Much of the ''Ring'', especially from ''Siegfried'' act 3 onwards, cannot be said to be in traditional, clearly definedkeys

Key or The Key may refer to:

Common meanings

* Key (cryptography), a piece of information that controls the operation of a cryptography algorithm

* Key (lock), device used to control access to places or facilities restricted by a lock

* Key (map ...

for long stretches, but rather in 'key regions', each of which flows smoothly into the following. This fluidity avoided the musical equivalent of clearly defined musical paragraphs, and assisted Wagner in building the work's huge structures. Tonal indeterminacy was heightened by the increased freedom with which he used dissonance and chromaticism

Chromaticism is a compositional technique interspersing the primary diatonic scale, diatonic pitch (music), pitches and chord (music), chords with other pitches of the chromatic scale. In simple terms, within each octave, diatonic music uses o ...

. Chromatically altered chords

Chord may refer to:

* Chord (music), an aggregate of musical pitches sounded simultaneously

** Guitar chord a chord played on a guitar, which has a particular tuning

* Chord (geometry), a line segment joining two points on a curve

* Chord (as ...

are used very liberally in the ''Ring'', and this feature, which is also prominent in ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was compose ...

'', is often cited as a milestone on the way to Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

's revolutionary break with the traditional concept of key and his dissolution of consonance as the basis of an organising principle in music.

Composition

The text

In summer 1848 Wagner wrote ''The Nibelung Myth as Sketch for a Drama'', combining the medieval sources previously mentioned into a single narrative, very similar to the plot of the eventual ''Ring'' cycle, but nevertheless with substantial differences. Later that year he began writing a libretto entitled ''Siegfrieds Tod'' ("Siegfried's Death"). He was possibly stimulated by a series of articles in the ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik

'Die'' (; en, " heNew Journal of Music") is a music magazine, co-founded in Leipzig by Robert Schumann, his teacher and future father-in law Friedrich Wieck, and his close friend Ludwig Schuncke. Its first issue appeared on 3 April 1834.

Histo ...

'', inviting composers to write a 'national opera' based on the Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poetry, epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition ...

, a 12th-century High German poem which, since its rediscovery in 1755, had been hailed by the German Romantics as the "German national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with as ...

". ''Siegfrieds Tod'' dealt with the death of Siegfried, the central heroic figure of the Nibelungenlied. The idea had occurred to others – the correspondence of Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sy ...

in 1840/41 reveals that they were both outlining scenarios on the subject: Fanny wrote 'The hunt with Siegfried's death provides a splendid finale to the second act'.

By 1850, Wagner had completed a musical sketch (which he abandoned) for ''Siegfrieds Tod''. He now felt that he needed a preliminary opera, ''Der junge Siegfried'' ("The Young Siegfried", later renamed to "Siegfried"), to explain the events in ''Siegfrieds Tod'', and his verse draft of this was completed in May 1851. By October, he had made the momentous decision to embark on a cycle of four operas, to be played over four nights: ''Das Rheingold'', ''Die Walküre'', ''Der Junge Siegfried'' and ''Siegfrieds Tod''; the text for all four parts was completed in December 1852, and privately published in February 1853.

The music

In November 1853, Wagner began the composition draft of ''Das Rheingold''. Unlike the verses, which were written as it were in reverse order, the music would be composed in the same order as the narrative. Composition proceeded until 1857, when the final score up to the end of act 2 of ''Siegfried'' was completed. Wagner then laid the work aside for twelve years, during which he wrote ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was compose ...

'' and ''Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

(; "The Master-Singers of Nuremberg"), WWV 96, is a music drama, or opera, in three acts, by Richard Wagner. It is the longest opera commonly performed, taking nearly four and a half hours, not counting two breaks between acts, and is traditio ...

''.

By 1869, Wagner was living at Tribschen

Tribschen (also seen as ''Triebschen'') is a district of the city of Lucerne, in the Canton of Lucerne in central Switzerland.

Tribschen is best known today as the home of the German composer Richard Wagner from 30 March 1866 to 22 April 1872. W ...

on Lake Lucerne

__NOTOC__

Lake Lucerne (german: Vierwaldstättersee, literally "Lake of the four forested settlements" (in English usually translated as ''forest cantons''), french: lac des Quatre-Cantons, it, lago dei Quattro Cantoni) is a lake in central ...

, sponsored by King Ludwig II of Bavaria

Ludwig II (Ludwig Otto Friedrich Wilhelm; 25 August 1845 – 13 June 1886) was King of Bavaria from 1864 until his death in 1886. He is sometimes called the Swan King or ('the Fairy Tale King'). He also held the titles of Count Palatine of the ...

. He returned to ''Siegfried'', and, remarkably, was able to pick up where he left off. In October, he completed the final work in the cycle. He chose the title ''Götterdämmerung'' instead of ''Siegfrieds Tod''. In the completed work the gods are destroyed in accordance with the new pessimistic thrust of the cycle, not redeemed as in the more optimistic originally planned ending. Wagner also decided to show onstage the events of ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Walküre'', which had hitherto only been presented as back-narration in the other two parts. These changes resulted in some discrepancies in the cycle, but these do not diminish the value of the work.

Performances

First productions

On King Ludwig's insistence, and over Wagner's objections, "special previews" of ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Walküre'' were given at the National Theatre in Munich, before the rest of the ''Ring''. Thus, ''Das Rheingold'' premiered on 22 September 1869, and ''Die Walküre'' on 26 June 1870. Wagner subsequently delayed announcing his completion of ''

On King Ludwig's insistence, and over Wagner's objections, "special previews" of ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Walküre'' were given at the National Theatre in Munich, before the rest of the ''Ring''. Thus, ''Das Rheingold'' premiered on 22 September 1869, and ''Die Walküre'' on 26 June 1870. Wagner subsequently delayed announcing his completion of ''Siegfried

Siegfried is a German-language male given name, composed from the Germanic elements ''sig'' "victory" and ''frithu'' "protection, peace".

The German name has the Old Norse cognate ''Sigfriðr, Sigfrøðr'', which gives rise to Swedish ''Sigfrid' ...

'' to prevent this work also being premiered against his wishes.

Wagner had long desired to have a special festival opera house, designed by himself, for the performance of the ''Ring''. In 1871, he decided on a location in the Bavarian town of Bayreuth

Bayreuth (, ; bar, Bareid) is a town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtelgebirge Mountains. The town's roots date back to 1194. In the 21st century, it is the capital of U ...

. In 1872, he moved to Bayreuth, and the foundation stone was laid. Wagner would spend the next two years attempting to raise capital for the construction, with scant success; King Ludwig finally rescued the project in 1874 by donating the needed funds. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus

The ''Bayreuth Festspielhaus'' or Bayreuth Festival Theatre (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspielhaus, ) is an opera house north of Bayreuth, Germany, built by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner and dedicated solely to the performa ...

opened in 1876 with the first complete performance of the ''Ring'', which took place from 13 to 17 August.

In 1882, London impresario

An impresario (from the Italian ''impresa'', "an enterprise or undertaking") is a person who organizes and often finances concerts, plays, or operas, performing a role in stage arts that is similar to that of a film or television producer.

Hist ...

Alfred Schulz-Curtius organized the first staging in the United Kingdom of the ''Ring'' cycle, conducted by Anton Seidl

Anton Seidl (7 May 185028 March 1898) was a famous Hungarian Wagner conductor, best known for his association with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City and the New York Philharmonic.

Biography

He was born in Pest, Austria-Hungary, where he ...

and directed by Angelo Neumann

Josef Angelo Neumann (18 August 1838 – 20 December 1910) was a German operatic baritone and theater director. First a baritone at major opera houses in Europe, including the Vienna Imperial Opera, he was the managing director of the Leipzig O ...

.

The first production of the ''Ring'' in Italy was in Venice (the place where Wagner died), just two months after his 1883 death, at La Fenice

Teatro La Fenice (, "The Phoenix") is an opera house in Venice, Italy. It is one of "the most famous and renowned landmarks in the history of Italian theatre" and in the history of opera as a whole. Especially in the 19th century, La Fenice beca ...

.

The first Australasian ''Ring'' (and '' The Mastersingers of Nuremberg'') was presented by the Thomas Quinlan company Melbourne and Sydney in 1913.

Modern productions

The ''Ring'' is a major undertaking for any opera company: staging four interlinked operas requires a huge commitment both artistically and financially; hence, in most opera houses, production of a new ''Ring'' cycle will happen over a number of years, with one or two operas in the cycle being added each year. TheBayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

, where the complete cycle is performed most years, is unusual in that a new cycle is almost always created within a single year.

Early productions of the ''Ring'' cycle stayed close to Wagner's original Bayreuth staging. Trends set at Bayreuth have continued to be influential. Following the closure of the Festspielhaus during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the 1950s saw productions by Wagner's grandsons Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner

Wolfgang Wagner (30 August 191921 March 2010) was a German opera director. He is best known as the director (Festspielleiter) of the Bayreuth Festival, a position he initially assumed alongside his brother Wieland in 1951 until the latter's ...

(known as the 'New Bayreuth' style), which emphasised the human aspects of the drama in a more abstract setting.

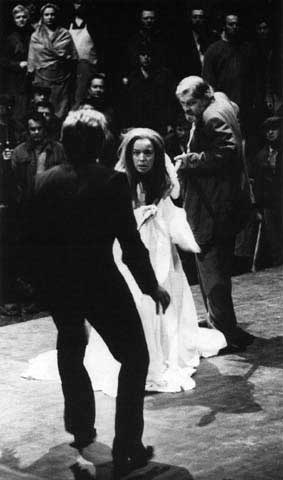

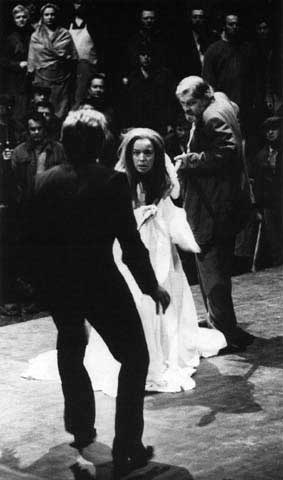

Perhaps the most famous modern production was the centennial production of 1976, the ''

Perhaps the most famous modern production was the centennial production of 1976, the ''Jahrhundertring

The ''Jahrhundertring'' (''Centenary Ring'') was the production of Richard Wagner's ''Ring Cycle'', ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'', at the Bayreuth Festival in 1976, celebrating the centenary of both the festival and the first performance of the comp ...

'', directed by Patrice Chéreau

Patrice Chéreau (; 2 November 1944 – 7 October 2013) was a French opera and theatre director, filmmaker, actor and producer. In France he is best known for his work for the theatre, internationally for his films '' La Reine Margot'' and ...

and conducted by Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

. Set in the industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, it replaced the depths of the Rhine with a hydroelectric power dam and featured grimy sets populated by men and gods in 19th and 20th century business suits. This drew heavily on the reading of the ''Ring'' as a revolutionary drama and critique of the modern world, famously expounded by George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

in ''The Perfect Wagnerite''. Early performances were booed but the audience of 1980 gave it a 45-minute ovation in its final year.

Seattle Opera

Seattle Opera is an opera company based in Seattle, Washington. It was founded in 1963 by Glynn Ross, who served as its first general director until 1983. The company's season runs from August through late May, comprising five or six operas of ...

has created three different productions of the tetralogy: ''Ring 1'', 1975 to 1984: Originally directed by George London, with designs by John Naccarato following the famous illustrations by Arthur Rackham

Arthur Rackham (19 September 1867 – 6 September 1939) was an English book illustrator. He is recognised as one of the leading figures during the Golden Age of British book illustration. His work is noted for its robust pen and ink drawings, ...

. It was performed twice each summer, once in German, once in Andrew Porter's English adaptation. Henry Holt conducted all performances. ''Ring 2'', 1985–1995: Directed by Francois Rochaix, with sets and costumes designed by Robert Israel, lighting by Joan Sullivan, and supertitles (the first ever created for the ''Ring'') by Sonya Friedman. The production set the action in a world of nineteenth-century theatricality; it was initially controversial in 1985, it sold out its final performances in 1995. Conductors included Armin Jordan

Armin Jordan (9 April 1932 – 20 September 2006) was a Swiss conductor known for his interpretations of French music, Mozart and Wagner.

Armin Jordan was born in Lucerne, Switzerland. "Mr. Jordan was a large man, with a slab of a face and a ful ...

(''Die Walküre'' in 1985), Manuel Rosenthal

Manuel Rosenthal (18 June 1904 – 5 June 2003) was a French composer and conductor who held leading positions with musical organizations in France and America. He was friends with many contemporary composers, and despite a considerable list of c ...

(1986), and Hermann Michael (1987, 1991, and 1995). ''Ring 3'', 2000–2013: the production, which became known as the "Green" ''Ring'', was in part inspired by the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

. Directed by Stephen Wadsworth, set designer Thomas Lynch, costume designer Martin Pakledinaz

Martin Pakledinaz (September 1, 1953 – July 8, 2012) was an American costume designer for stage and film.

He won his Tony Awards for designing the costumes for ''Thoroughly Modern Millie'' and the 2000 revival of ''Kiss Me, Kate'', which a ...

, lighting designer Peter Kaczorowski

Peter Kaczorowski (born 1956) is an American theatrical lighting designer.

Kaczorowski was born in Buffalo, New York. He is credited with lighting designs for Broadway and off-Broadway shows, as well extensive work in opera. He has been nominated ...

; Armin Jordan conducted in 2000, Franz Vote in 2001, and Robert Spano

Robert Spano ( ; born 7 May 1961, Conneaut, Ohio) is an American conductorDavidson, Justin. "CLASSICAL MUSIC: Looking for Magic: Mixing visuals and language into a performance is just part of conductor Robert Spano's pursuit of orchestral risk" ...

in 2005 and 2009. The 2013 performances, conducted by Asher Fisch

Asher Fisch (Hebrew: אשר פיש) (born May 19, 1958, Jerusalem, Israel) is an Israeli conductor and pianist.

Fisch began his career as an assistant of Daniel Barenboim and an associate conductor of the Berlin State Opera. He made his United ...

, were released as a commercial recording on compact disc and on iTunes.

In 2003 the first production of the cycle in Russia in modern times was conducted by Valery Gergiev

Valery Abisalovich Gergiev (russian: Вале́рий Абиса́лович Ге́ргиев, ; os, Гергиты Абисалы фырт Валери, Gergity Abisaly fyrt Valeri; born 2 May 1953) is a Russian conductor and opera company d ...

at the Mariinsky Opera

The Mariinsky Theatre ( rus, Мариинский театр, Mariinskiy teatr, also transcribed as Maryinsky or Mariyinsky) is a historic theatre of opera and ballet in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Opened in 1860, it became the preeminent music th ...

, Saint Petersburg, designed by George Tsypin

George Tsypin is an American stage designer, sculptor and architect.

He was an artistic director, production designer and coauthor of the script for the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games in Sochi in 2014.

Early life and education

Tsypin was ...

. The production drew parallels with Ossetia

Ossetia ( , ; os, Ирыстон or , or ; russian: Осетия, Osetiya; ka, ოსეთი, translit. ''Oseti'') is an ethnolinguistic region located on both sides of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, largely inhabited by the Ossetians. ...

n mythology.

The Royal Danish Opera

The Royal Danish Theatre (RDT, Danish: ') is both the national Danish performing arts institution and a name used to refer to its old purpose-built venue from 1874 located on Kongens Nytorv in Copenhagen. The theatre was founded in 1748, first ser ...

performed a complete ''Ring'' cycle in May 2006 in its new waterfront home, the Copenhagen Opera House

The Copenhagen Opera House (in Danish usually called Operaen, literally ''The opera'') is the national opera house of Denmark, and among the most modern opera houses in the world. It is also one of the most expensive opera houses ever built at a ...

. This version of the ''Ring'' tells the story from the viewpoint of Brünnhilde and has a distinct feminist angle. For example, in a key scene in ''Die Walküre'', it is Sieglinde and not Siegmund who manages to pull the sword Nothung out of a tree. At the end of the cycle, Brünnhilde does not die, but instead gives birth to Siegfried's child.

San Francisco Opera

San Francisco Opera (SFO) is an American opera company founded in 1923 by Gaetano Merola (1881–1953) based in San Francisco, California.

History

Gaetano Merola (1923–1953)

Merola's road to prominence in the Bay Area began in 1906 when he ...

and Washington National Opera

The Washington National Opera (WNO) is an American opera company in Washington, D.C. Formerly the Opera Society of Washington and the Washington Opera, the company received Congressional designation as the National Opera Company in 2000. Performa ...

began a co-production of a new cycle in 2006 directed by Francesca Zambello

Francesca Zambello (born August 24, 1956) is an American opera and theatre director. She serves as director of Glimmerglass Festival and the Washington National Opera.

Early life and education

Born in New York City, Zambello lived in Europe when ...

. The production uses imagery from various eras of American history and has a feminist and environmentalist viewpoint. Recent performances of this production took place at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (formally known as the John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts, and commonly referred to as the Kennedy Center) is the United States National Cultural Center, located on the Potom ...

in Washington D.C. in April/May 2016, featuring Catherine Foster and Nina Stemme

Nina Maria Stemme (born Nina Maria Thöldte on 11 May 1963) is a Swedish dramatic soprano opera singer.

Stemme "is regarded by today's opera fans as our era's greatest Wagnerian soprano". In 2010, Michael Kimmelman wrote of one of Stemme's perf ...

as Brünnhilde, Daniel Brenna as Siegfried, and Alan Held as Wotan.

Los Angeles Opera

The Los Angeles Opera is an American opera company in Los Angeles, California. It is the fourth-largest opera company in the United States. The company's home base is the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, part of the Los Angeles Music Center.

Leadersh ...

presented its first ''Ring'' cycle in 2010 directed by Achim Freyer

Achim Freyer (; born 30 March 1934) is a German stage director, set designer and painter. A protégé of Bertolt Brecht, Freyer has become one of the world's leading opera directors, working throughout Europe and, since 2002, in the United State ...

. Freyer staged an abstract production that was praised by many critics but criticized by some of its own stars. The production featured a raked stage, flying props, screen projections and special effects.

The

The Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

began a new ''Ring'' cycle directed by French-Canadian theater director Robert Lepage

Robert Lepage (born December 12, 1957) is a Canadian playwright, actor, film director, and stage director.

Early life

Lepage was raised in Quebec City. At age five, he was diagnosed with a rare form of alopecia, which caused complete hair lo ...

in 2010. Premiering with ''Das Rheingold'' on opening night of the 2010/2011 Season conducted by James Levine

James Lawrence Levine (; June 23, 1943 – March 9, 2021) was an American conductor and pianist. He was music director of the Metropolitan Opera from 1976 to 2016. He was terminated from all his positions and affiliations with the Met on March 1 ...

with Bryn Terfel

Sir Bryn Terfel Jones, (; born 9 November 1965) (known professionally as Bryn Terfel) is a Welsh bass-baritone opera and concert singer. Terfel was initially associated with the roles of Mozart, particularly '' Figaro'', ''Leporello'' and ''D ...

as Wotan. This was followed by ''Die Walküre'' in April 2011 starring Deborah Voigt

Deborah Voigt (born August 4, 1960) is an American dramatic soprano who has sung roles in operas by Wagner and Richard Strauss.

Biography and career

Early life and education

Debbie Joy Voigt was born into a religious Southern Baptist family ...

. The 2011/12 season introduced ''Siegfried'' and ''Götterdämmerung'' with Voigt, Terfel, and Jay Hunter Morris

Jay Hunter Morris (born July 3, 1963) is an American operatic tenor. He is best known internationally for the role of Siegfried in the Metropolitan Opera's 2011–12 series of Wagner's '' Ring Cycle'', performances of which were cinecast and radio ...

before the entire cycle was given in the Spring of 2012 conducted by Fabio Luisi

Fabio Luisi (born 17 January 1959) is an Italian conductor. He is currently principal conductor of the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, music director of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and chief conductor of the NHK Symphony Orchestra.

Biog ...

(who stepped in for Levine due to health issues). Lepage's staging was dominated by a 90,000 pound (40 tonne) structure which consisted of 24 identical aluminium planks able to rotate independently on a horizontal axis across the stage, providing level, sloping, angled or moving surfaces facing the audience. Bubbles, falling stones and fire were projected on to these surfaces, linked by computer with the music and movement of the characters. The subsequent HD recordings in 2013 won the Met's orchestra and chorus the Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording

The Grammy Award

The Grammy Awards (stylized as GRAMMY), or simply known as the Grammys, are awards presented by the Recording Academy of the United States to recognize "outstanding" achievements in the music industry. They are regarded by man ...

for their performance. In 2019, the Metropolitan Opera revived the Lepage staging for the first time since 2013 with Philippe Jordan

Philippe Jordan (born 18 October 1974) is a Swiss conductor and pianist.

Biography

Born in Zürich, the son of conductor Armin Jordan, he began to study piano at the age of six. At age eight, he joined the Zürcher Sängerknaben. He has ackno ...

conducting, Greer Grimsley

Greer Grimsley (born May 30, 1956) is an American bass-baritone who has had an active international opera career for the last three decades. He has sung leading roles with all of America's leading opera companies, including the Metropolitan Opera ...

and Michael Volle

Michael Volle (; born 1960) is a German operatic baritone. After engagements at several German and Swiss opera houses, he has worked freelance since 2011. While he first appeared in Mozart roles such as Guglielmo, Papageno and Don Giovanni, he m ...

rotating as Wotan, and Andreas Schager

Andreas Schager is an Austrian operatic tenor. He began his career as a tenor for operettas, but has developed into singing Heldentenor parts by Richard Wagner including Tristan, Siegmund, Siegfried and Parsifal. A member of the Staatsoper Berlin, ...

rotating as Siegfried, and Met homegrown Christine Goerke

Christine Goerke (born 1969) is an American dramatic soprano.

Early life and education

The daughter of Richard Goerke and Marguerite Goerke, Goerke was born in 1969 in New York State. She grew up in Medford, New York, where she attended Tremont ...

as Brünnhilde. Lepage's "Machine", as it affectionately became known, underwent major reconfiguration for the revival in order to dampen the creaking that it had produced in the past (to the annoyance of audience members and critics) and to improve its reliability, as it had been known to break down during earlier runs including on the opening night of ''Rheingold''.

Opera Australia

Opera Australia is the principal opera company in Australia. Based in Sydney, its performance season at the Sydney Opera House accompanied by the Opera Australia Orchestra runs for approximately eight months of the year, with the remainder of ...

presented the ''Ring'' cycle at the State Theatre in Melbourne, Australia, in November 2013, directed by Neil Armfield

Neil Geoffrey Armfield (born 22 April 1955) is an Australian director of theatre, film and opera.

Biography

Born in Sydney, Armfield is the third and youngest son of Len, a factory worker at the nearby Arnott's Biscuits factory and Nita Armf ...

and conducted by Pietari Inkinen

Pietari Inkinen (born 29 April 1980, Kouvola, Finland) is a Finnish violinist and conductor.

Biography

Inkinen began violin and piano studies at age 4. As a youth, he also performed in a rock band. He attended the Sibelius Academy and gradu ...

. ''Classical Voice America'' heralded the production as "one of the best Rings anywhere in a long time." The production was presented again in Melbourne from 21 November to 16 December 2016 starring Lise Lindstrom

Lise Lindstrom is an American operatic soprano. She is best known for the title role of Puccini's ''Turandot'' and also highly recognized in the dramatic repertory of Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner.

Early life

Lindstrom, whose grandfathe ...

, Stefan Vinke, Amber Wagner and Jacqueline Dark

Jacqueline Lisa Dark (also Jacqueline Moran) is an Australian operatic mezzo-soprano. She was born in Ballarat and attended the University of Ballarat from 1986 to 1988, receiving a Bachelor of Science (Physics) and a Graduate Diploma of Educati ...

.

It is possible to perform ''The Ring'' with fewer resources than usual. In 1990, the City of Birmingham Touring Opera (now Birmingham Opera Company

Birmingham Opera Company is a professional opera company based in Birmingham, England, that specialises in innovative and avant-garde productions of the operatic repertoire, often in unusual venues.

History

The company was founded by leading in ...

), presented a two-evening adaptation (by Jonathan Dove

Jonathan Dove (born 18 July 1959) is an English composer of opera, choral works, plays, films, and orchestral and chamber music. He has arranged a number of operas for English Touring Opera and the City of Birmingham Touring Opera (now Birmin ...

) for a limited number of solo singers, each doubling several roles, and 18 orchestral players. This version was subsequently given productions in the USA. A heavily cut-down version (7 hours plus intervals) was performed at the Teatro Colón

The Teatro Colón (Spanish: ''Columbus Theatre'') is the main opera house in Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is considered one of the ten best opera houses in the world by National Geographic. According to a survey carried out by the acousti ...

in Buenos Aires on 26 November 2012 to mark the 200th anniversary of Wagner's birth.

In a different approach, ''Der Ring in Minden

''Der Ring in Minden'' was a project to stage Richard Wagner's cycle ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' at the Stadttheater Minden, beginning in 2015 with ''Das Rheingold'', followed by the other parts in the succeeding years, and culminating with the com ...

'' staged the cycle on the small stage of the Stadttheater Minden

Stadttheater Minden is a municipal theatre in Minden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. The theatre has no ensemble, but stages some productions of its own. It became known for a Wagner project culminating in ''Der Ring in Minden''.

History

The ...

, beginning in 2015 with ''Das Rheingold

''Das Rheingold'' (; ''The Rhinegold''), WWV 86A, is the first of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National ...

'', followed by the other parts in the succeeding years, and culminating with the complete cycle performed twice in 2019. The stage director was Gerd Heinz

Gerd Heinz (born 21 September 1940) is a German stage, film and television actor and a stage director. He was also active as an academic teacher and theatre manager (Intendant). From 1989, he turned more towards opera. He staged a drama by Thomas ...

, and Frank Beermann

Frank Beermann (born 13 March 1965) is a German conductor. He was Generalmusikdirektor (GMD) at the Chemnitz Opera for several years, and has worked freelance at international opera houses from 2012. He has conducted premieres and recordings of ...

conducted the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie

The Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie (North West German Philharmonic) is a German orchestra, symphony orchestra based in Herford. It was founded in 1950 and, along with Philharmonie Südwestfalen and Landesjugendorchester NRW, is one of the 'official ...

, playing at the back of the stage. The singers acted in front of the orchestra, making an intimate approach to the dramatic situations possible. The project received international recognition.

Recordings of the ''Ring'' cycle

Other treatments of the ''Ring'' cycle

Orchestral versions of the ''Ring'' cycle, summarizing the work in a single movement of an hour or so, have been made byLeopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appeara ...

, Lorin Maazel

Lorin Varencove Maazel (, March 6, 1930 – July 13, 2014) was an American conductor, violinist and composer. He began conducting at the age of eight and by 1953 had decided to pursue a career in music. He had established a reputation in th ...

(''Der Ring ohne Worte'') (1988) and Henk de Vlieger

Henk de Vlieger (born 1953 in Schiedam) is a Dutch percussionist, composer and arranger.

Since 1984 he has been a permanent member of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra as percussionist. In May 2011 he was appointed artistic advisor t ...

(''The Ring: an Orchestral Adventure''), (1991).

English-Canadian comedian and singer Anna Russell

Anna Russell (born Anna Claudia Russell-Brown; 27 December 191118 October 2006) was an English–Canadian singer and comedian. She gave many concerts in which she sang and played comic musical sketches on the piano. Among her best-known works a ...

recorded a twenty-two-minute version of the ''Ring'' for her album ''Anna Russell Sings! Again?'' in 1953, characterized by camp humour and sharp wit.

Produced by the Ridiculous Theatrical Company

Theatre of the Ridiculous is a theatrical genre that began in New York City in the 1960s.Bottoms, Stephen J. Chapter 11: "The Play-House of the Ridiculous: Beyond Absurdity". ''Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960s Off-Off-Broadway M ...

, Charles Ludlam

Charles Braun Ludlam (April 12, 1943 – May 28, 1987) was an American actor, director, and playwright.

Biography

Early life

Ludlam was born in Floral Park, New York, the son of Marjorie (née Braun) and Joseph William Ludlam. He was raise ...

's 1977 play ''Der Ring Gott Farblonjet'' was a spoof of Wagner's operas. The show received a well-reviewed 1990 revival in New York at the Lucille Lortel Theatre

The Lucille Lortel Theatre is an off-Broadway playhouse at 121 Christopher Street in Manhattan's West Village. It was built in 1926 as a 590-seat movie theater called the New Hudson, later known as Hudson Playhouse. The interior is largely unch ...

.

In 1991, Seattle Opera

Seattle Opera is an opera company based in Seattle, Washington. It was founded in 1963 by Glynn Ross, who served as its first general director until 1983. The company's season runs from August through late May, comprising five or six operas of ...

premiered a musical comedy parody of the Ring Cycle called Das Barbecü, with book and lyrics by Jim Luigs and music by Scott Warrender. It follows the outline of the cycle's plot but shifts the setting to Texas ranch country. It was later produced off-broadway and elsewhere around the world.

The German two-part television movie '' Dark Kingdom: The Dragon King'' (2004, also known as ''Ring of the Nibelungs'', ''Die Nibelungen'', ''Curse of the Ring'' and ''Sword of Xanten''), is based in some of the same material Richard Wagner used for his music drama

is a German word that means a unity of prose and music. Initially coined by Theodor Mundt in 1833, it was most notably used by Richard Wagner, along with Gesamtkunstwerk, to define his operas.

Usage

Mundt formulated his definition explicitly ...

s ''Siegfried

Siegfried is a German-language male given name, composed from the Germanic elements ''sig'' "victory" and ''frithu'' "protection, peace".

The German name has the Old Norse cognate ''Sigfriðr, Sigfrøðr'', which gives rise to Swedish ''Sigfrid' ...

'' and ''Götterdämmerung

' (; ''Twilight of the Gods''), WWV 86D, is the last in Richard Wagner's cycle of four music dramas titled (''The Ring of the Nibelung'', or ''The Ring Cycle'' or ''The Ring'' for short). It received its premiere at the on 17 August 1876, as p ...

''.

An adaptation of Wagner's storyline was published as a graphic novel

A graphic novel is a long-form, fictional work of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comic scholars and industry ...

in 2018 by P. Craig Russell

Philip Craig Russell (born October 30, 1951) is an American comics artist, writer, and illustrator. His work has won multiple Harvey and Eisner Awards. Russell was the first mainstream comic book creator to come out as openly gay.

Biography ...

.

References and notes

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* Besack, Michael, ''The Esoteric Wagner – an introduction to Der Ring des Nibelungen'', Berkeley: Regent Press, 2004 . * Di Gaetani, John Louis, ''Penetrating Wagner's Ring: An Anthology''. New York: Da Capo Press, 1978. . * Gregor-Dellin, Martin, (1983) ''Richard Wagner: His Life, His Work, His Century.'' Harcourt, . * Holman, J. K. ''Wagner's Ring: A Listener's Companion and Concordance''. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 2001. * Lee, M. Owen, (1994) ''Wagner's Ring: Turning the Sky Round.'' Amadeus Press, . * Magee, Bryan, (1988) ''Aspects of Wagner.'' Oxford University Press, . * May, Thomas, (2004) ''Decoding Wagner.'' Amadeus Press, . * Millington, Barry (editor) (2001) ''The Wagner Compendium.'' Thames & Hudson, . * Sabor, Rudolph, (1997) ''Richard Wagner: Der Ring des Nibelungen: a companion volume''. Phaidon Press, . * Scruton, Sir Roger, (2016)The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung

'. Penguin UK, . * Spotts, Frederick, (1999)

Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival

'. Yale University Press .

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ring Des Nibelungen, Der 1876 operas Operas Libretti by Richard Wagner