Daughters Of Jacob Bridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Daughters of Jacob Bridge ( he, גשר בנות יעקב, ''Gesher Bnot Ya'akov''; ar, جسر بنات يعقوب, ''Jisr Benat Ya'kub''). is a bridge that spans the last natural ford of the Jordan at the southern end of the Hula Basin between the Korazim Plateau and the

165

ff Located southwest of the bridge are the remains of a Crusader castle known as ''Chastellet'' and east of the bridge are the remains of a

261

/ref>

In the late

In the late

182−183

/ref> Edward Robinson noted that during the 14th century, travellers crossed the river Jordan below the

Another

Another

Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between d ...

. It has been a crossing point for thousands of years.

The Crusaders called the site ''Jacob's Ford''. The medieval bridge was replaced in 1934 by a modern bridge further south during the draining of Lake Hula by the Palestine Land Development Company.Sufian, 2008, pp165

ff Located southwest of the bridge are the remains of a Crusader castle known as ''Chastellet'' and east of the bridge are the remains of a

Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

khan (caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was a roadside inn where travelers ( caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey. Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes coverin ...

).

The bridge is now part of Highway 91 and straddles the border between the Galilee and the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between d ...

(which was annexed by Israel in 1981). It is of strategic military significance as it is one of the few fixed crossing points over the upper Jordan River that enable access from the Golan Heights to the Upper Galilee

The Upper Galilee ( he, הגליל העליון, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; ar, الجليل الأعلى, ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical-political term in use since the end of the Second Temple period. It originally referred to a mountai ...

.

The caravan route from China to Morocco via Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

and Egypt used this crossing. It was part of the ancient highway recently dubbed "Via Maris

Via Maris is one modern name for an ancient trade route, dating from the early Bronze Age, linking Egypt with the northern empires of Syria, Anatolia and Mesopotamia — along the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Egypt, Israel, Turkey and S ...

", which was strategically important to the Ancient Egyptians, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

ns, Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

, Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

, Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

(early Muslims), Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, Ayyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

, Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

, Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, and modern inhabitants and armies who crossed the river at this place. The Crusaders built a castle overlooking the ford which threatened Damascus which was destroyed by Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

in 1179 in the Battle of Jacob's Ford. The old arched stone bridge marked the northern limit of Napoleon's advance in 1799.Preston, 1921, p261

/ref>

Etymology

The place was first associated with thebiblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

forefather of the Jews, Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam ...

/Israel, due to a confusion. The Crusader-era nunnery of Saint James (Saint Jacques in French) from Safed received part of the customs paid at the ford, and since James/Jacques is derived from Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam ...

, this led to the name Jacob's Ford.

History and archaeology of the ford site

Prehistory

Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

excavations at the prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov site have revealed evidence of human habitation in the area, from as early as 750,000 years ago. Archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem claim that the site provides evidence of "advanced human behavior" half a million years earlier than has previously been estimated as possible. Their report describes a layer at the site belonging to the Acheulian (a culture dating to the Lower Palaeolithic, at the very beginning of the Stone Age), where numerous stone tools, animal bones and plant remains have been found. According to the archaeologists Paul Pettitt and Mark White, the site has produced the earliest widely accepted evidence for the use of fire, dated approximately 790,000 years ago. A Tel-Aviv University

Tel Aviv University (TAU) ( he, אוּנִיבֶרְסִיטַת תֵּל אָבִיב, ''Universitat Tel Aviv'') is a public research university in Tel Aviv, Israel. With over 30,000 students, it is the largest university in the country. Loc ...

study found remains of a huge carp

Carp are various species of oily freshwater fish from the family Cyprinidae, a very large group of fish native to Europe and Asia. While carp is consumed in many parts of the world, they are generally considered an invasive species in parts of ...

fish cooked with the use of fire at the site 780,000 years ago.

Crusader and Ayyubid period

Jacob's Ford was a key river crossing point and major trade route betweenAcre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

and Damascus. It was utilized by Christian Palestine and Seljuk Syria as a major intersection between the two civilizations, making it strategically important. When Humphrey II of Toron was besieged in the city of Banyas in 1157, King Baldwin III of Jerusalem

Baldwin III (1130 – 10 February 1163) was King of Jerusalem from 1143 to 1163. He was the eldest son of Melisende and Fulk of Jerusalem. He became king while still a child, and was at first overshadowed by his mother Melisende, whom he event ...

was able to break the siege, only to be ambushed at Jacob's Ford in June of that year.

Later in the twelfth century, Baldwin IV of Jerusalem and Saladin continually contested the area around Jacob's Ford. Baldwin allowed the Templars

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

to build Chastelet castle overlooking Jacob's Ford known to the Arabs as ''Qasr al-'Ata'' commanding the road from Quneitra

Quneitra (also Al Qunaytirah, Qunaitira, or Kuneitra; ar, ٱلْقُنَيْطِرَة or ٱلْقُنَيطْرَة, ''al-Qunayṭrah'' or ''al-Qunayṭirah'' ) is the largely destroyed and abandoned capital of the Quneitra Governorate in sou ...

to Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

. On 23 August 1179, Saladin successfully conducted the siege of Jacob's Ford, destroying the unfinished fortification, known as the castle of Vadum Iacob or Chastellet.

Mamluk and Ottoman bridge

In the late

In the late Mamluk period

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16th ...

, Sefad

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an eleva ...

became a principal town and Baibars' postal road from Cairo to Damascus was extended with a branch that went through the north of Palestine. To accomplish this, the bridge was built over the Crusaders' Vadum Jacob (Jacob's ford). The bridge had the Mamluk characteristic dual-slope pathway like the Yibna Bridge. Al-Dimashqi (1256–1327) noted that "the Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

traverses the district of ''Al Khaitah'' and comes to the ''Jisr Ya'kub'' (''lit.'' "Jacob's Bridge"), under ''Kasr Ya'kub'' (''lit.'' "Jacob's Castle"), and reaching the Sea of Tiberias, falls into it."

Before 1444, a merchant constructed a khan (caravanserai) on the eastern side of the bridge, one of a series of such khans built at the time.Petersen, 1991, pp182−183

/ref> Edward Robinson noted that during the 14th century, travellers crossed the river Jordan below the

Lake of Tiberias

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest f ...

, while the first crossing in the area of ''Jisr Benat Yakob'' was noted in 1450 CE. The khan, at the eastern end of the bridge, and the bridge itself, were both probably built before 1450, according to Robinson.

For the year 1555−1556 CE ( AH 963) the toll post at the bridge collected 25,000 akçe, and in 1577 (985 H) a firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman com ...

commanded that the place had post horses ready.

On June 4th 1771, a combined force of Zahir al Umar's men and mamluk commander Abu al-Dhahab

Muḥammad Bey Abū aḏ-Ḏahab (1735–1775), also just called Abū Ḏahab (meaning "father of gold", a name apparently given to him on account of his generosity and wealth), was a Mamluk emir and regent of Ottoman Egypt.

Born in the North ...

met the Damascene Pasha in battle, The result was a victory for the Zayadina coalition and established control of Irbid

Irbid ( ar, إِربِد), known in ancient times as Arabella or Arbela (Άρβηλα in Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek), is the capital and largest city of the Irbid Governorate. It also has the second largest metropolitan population in ...

and Quneitra

Quneitra (also Al Qunaytirah, Qunaitira, or Kuneitra; ar, ٱلْقُنَيْطِرَة or ٱلْقُنَيطْرَة, ''al-Qunayṭrah'' or ''al-Qunayṭirah'' ) is the largely destroyed and abandoned capital of the Quneitra Governorate in sou ...

to Zahir al Umar. This also set in motion the later Final Invasion of Damascus Eyalet & Siege of Damascus by Abu al-Dhahab

The bridge was maintained through the Ottoman period, with a caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was a roadside inn where travelers ( caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey. Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes coverin ...

on one end of the bridge, as shown in the 1799 Jacotin map. During the Egyptian campaign of 1799, Napoleon sent his cavalry commander, general Murat, to defend the bridge, as a measure of preempting reinforcement from Damascus being sent to Akko

Acre ( ), known locally as Akko ( he, עַכּוֹ, ''ʻAkō'') or Akka ( ar, عكّا, ''ʻAkkā''), is a city in the coastal plain region of the Northern District of Israel.

The city occupies an important location, sitting in a natural harb ...

during the siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

laid by the French. Murat occupied nearby Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevat ...

and Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

, as well as the bridge and, by relying on the superior quality of French troops, managed to defeat Turkish units far outnumbering him. Jacotin's map marks the west side of the bridge with the name of General Murat and the date of 2 April 1799.

In 1881, the PEF PEF, PeF, or Pef may stand for the following abbreviations:

* Palestine Exploration Fund

* Peak expiratory flow

* PEF Private University of Management Vienna

* Pentax raw file (see Raw image format)

* Perpetual Education Fund

* Perpetual Emigratio ...

's ''Survey of Western Palestine'' (SWP) also noted about ''Jisr Benat Yakub'': "The bridge itself appears to be of later date than the Crusader period."

20th century

Another

Another battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

was fought there on 27 September 1918 during the Palestine Campaign of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, at the beginning of the pursuit by the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

of the retreating remnants of the Ottoman Yildirim Army Group towards Damascus. The central arch of the bridge was destroyed by the Turkish forces. The bridge was shortly repaired by ANZAC

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comm ...

sappers, flattening the original dual-slope pathway, making it useful for modern vehicles.

In 1934, during the draining of Lake Hula as part of a Zionist land reclamation

Land reclamation, usually known as reclamation, and also known as land fill (not to be confused with a waste landfill), is the process of creating new land from oceans, seas, riverbeds or lake beds. The land reclaimed is known as reclam ...

project, the old bridge was replaced by a modern one further south.

On the " Night of the Bridges" between 16 and 17 June 1946, the bridge was again destroyed by the Jewish Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the Is ...

. The Syrians captured the bridge on June 11, 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

, but later withdrew as a result of the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,National Water Carrier project, but after US pressure the intake was moved downstream to the

77

ff. * Jacob's Well, site associated with biblical Jacob in Samaritan and Christian tradition * Jubb Yussef (Joseph's Well), site associated with biblical Joseph in Muslim tradition

341

��344) * * *Murray, Alan V. editor. (2006), ''The Crusades: An Encyclopaedia'', * * * * * * * * * * * * *

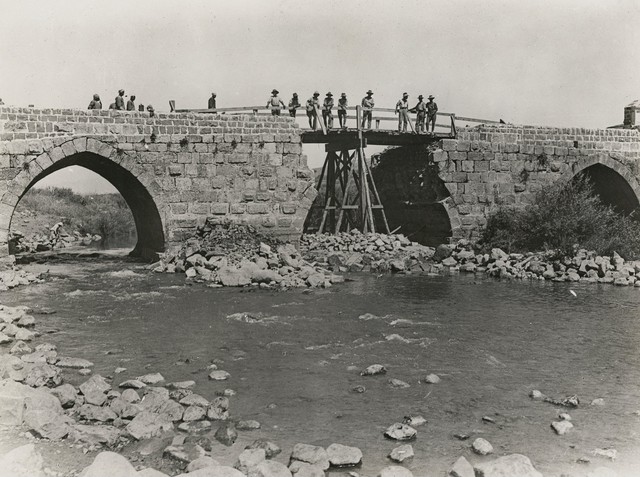

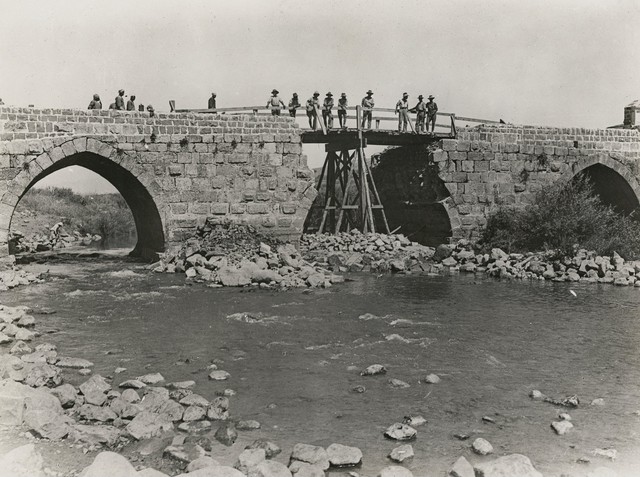

IAAWikimedia commonsBridge at Jisr Banat Ya'qub

12th-century bridge pictured early 20th century.

80th Brigade's Battles in the Six-Day War

Paratroopers Brigade website.

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov Acheulian Site Project

{{Coord, 33, 0, 37.02, N, 35, 37, 41.83, E, display=title Battles of the Crusades Battles involving the Ayyubids Bridges over the Jordan River Crusade places Hula Valley

Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest f ...

at Eshed Kinrot,Sosland, 2007, p. 70 which later became known as the Sapir Pumping Station at Tel Kinrot/Tell el-'Oreimeh.

During the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

, an Israeli paratrooper

A paratrooper is a military parachutist—someone trained to parachute into a military operation, and usually functioning as part of an airborne force. Military parachutists (troops) and parachutes were first used on a large scale during Wor ...

brigade captured the area and after the war the Israeli Combat Engineering Corps constructed a Bailey bridge

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, pre-fabricated, truss bridge. It was developed in 1940–1941 by the British for military use during the Second World War and saw extensive use by British, Canadian and American military engineering units. ...

. In the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Eg ...

, Syrian forces approached the vicinity of the bridge and as a precaution Israeli sappers placed explosives on the bridge but did not detonate them as the Syrians did not attempt to cross it.

21st century

In 2007, one of the two Bailey bridges at the site (one for traffic from east to west and the other handling traffic in the opposite direction) was replaced with a modern concrete span, while the other Bailey bridge was left intact for emergency use.See also

*Archaeology of Israel

The archaeology of Israel is the study of the archaeology of the present-day Israel, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. The ancient Land of Israel was a geographical bridge between the political and cultu ...

and Levantine archaeology

* Barid, Muslim postal network renewed during Mamluk period (roads, bridges, khans)

**Jisr al-Ghajar

Ghajar ( ar, غجر, he, ע'ג'ר or ) is an Alawite-Arab village on the Hasbani River, on the border between Lebanon and the Israeli-occupied portion of Syria's Golan Heights. In , it had a population of .

History

Early history

Control ...

, stone bridge south of Ghajar

**Al-Sinnabra

Al-Sinnabra or Sinn en-Nabra, is the Arabic place name for a historic site on the southern shore of the Sea of Galilee in modern-day Israel. The ancient site lay on a spur from the hills that close the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, next t ...

Crusader bridge, with nearby Jisr Umm el-Qanatir/Jisr Semakh and Jisr es-Sidd further downstream

** Jisr al-Majami bridge over the Jordan, with Mamluk khan

** Jisr Jindas bridge over the Ayalon near Lydda and Ramla

** Yibna Bridge or "Nahr Rubin Bridge"

** Isdud Bridge (Mamluk, 13th century) outside Ashdod/Isdud

** Jisr ed-Damiye, bridges over the Jordan (Roman, Mamluk, modern)

* Bir Ma'in, Arab village near Ramle, connected by a foundation legend to Jacob/Ya'kub and Daughters of Jacob Bridge/Jisr Benat Ya'kub.Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, vol 2, pp77

ff. * Jacob's Well, site associated with biblical Jacob in Samaritan and Christian tradition * Jubb Yussef (Joseph's Well), site associated with biblical Joseph in Muslim tradition

References

Bibliography

* * * * (pp341

��344) * * *Murray, Alan V. editor. (2006), ''The Crusades: An Encyclopaedia'', * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

*Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4IAA

12th-century bridge pictured early 20th century.

80th Brigade's Battles in the Six-Day War

Paratroopers Brigade website.

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov Acheulian Site Project

{{Coord, 33, 0, 37.02, N, 35, 37, 41.83, E, display=title Battles of the Crusades Battles involving the Ayyubids Bridges over the Jordan River Crusade places Hula Valley