Cultural Judaism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jewish culture is the culture of the

Jewish culture is the culture of the

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in  Between the

Between the

In the

In the

The early Jewish activity in science can be found in the

The early Jewish activity in science can be found in the

The

The

More remarkable contributors include

More remarkable contributors include

Literary and theatrical expressions of secular Jewish culture may be in specifically Jewish languages such as

Literary and theatrical expressions of secular Jewish culture may be in specifically Jewish languages such as  In ''Modern Judaism: An Oxford Guide'', Yaakov Malkin, Professor of Aesthetics and Rhetoric at

In ''Modern Judaism: An Oxford Guide'', Yaakov Malkin, Professor of Aesthetics and Rhetoric at

The

The

From their

From their

The earliest known Hebrew language drama was written around 1550 by a History of the Jews in Italy, Jewish-Italian writer from Mantua. A few works were written by rabbis and Kabbalah, Kabbalists in 17th-century Amsterdam, where Jews were relatively free from persecution and had both flourishing religious and secular Jewish cultures. All of these early Hebrew plays were about Biblical or mystical subjects, often in the form of

The earliest known Hebrew language drama was written around 1550 by a History of the Jews in Italy, Jewish-Italian writer from Mantua. A few works were written by rabbis and Kabbalah, Kabbalists in 17th-century Amsterdam, where Jews were relatively free from persecution and had both flourishing religious and secular Jewish cultures. All of these early Hebrew plays were about Biblical or mystical subjects, often in the form of

Before

Before

Deriving from Biblical traditions, Jewish dance has long been used by Jews as a medium for the expression of joy and other communal emotions. Each Jewish diaspora, Jewish diasporic community developed its own dance traditions for wedding celebrations and other distinguished events. For

Deriving from Biblical traditions, Jewish dance has long been used by Jews as a medium for the expression of joy and other communal emotions. Each Jewish diaspora, Jewish diasporic community developed its own dance traditions for wedding celebrations and other distinguished events. For

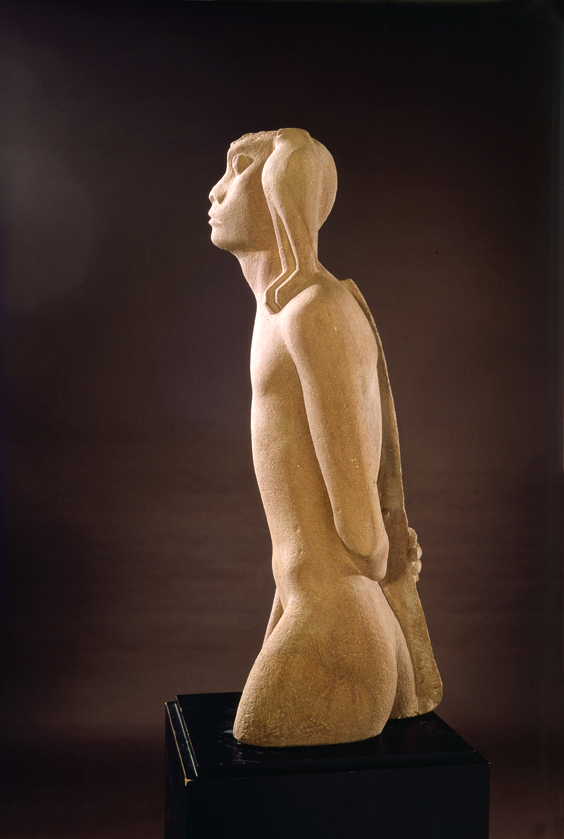

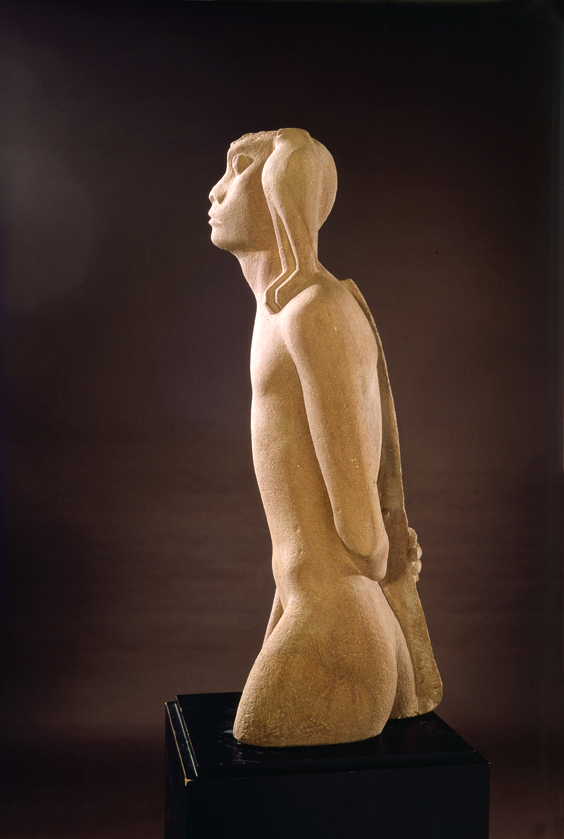

Compared to music or theater, there is less of a specifically Jewish tradition in the visual arts. The most likely and accepted reason is that, as has been previously shown with Jewish music and literature, before

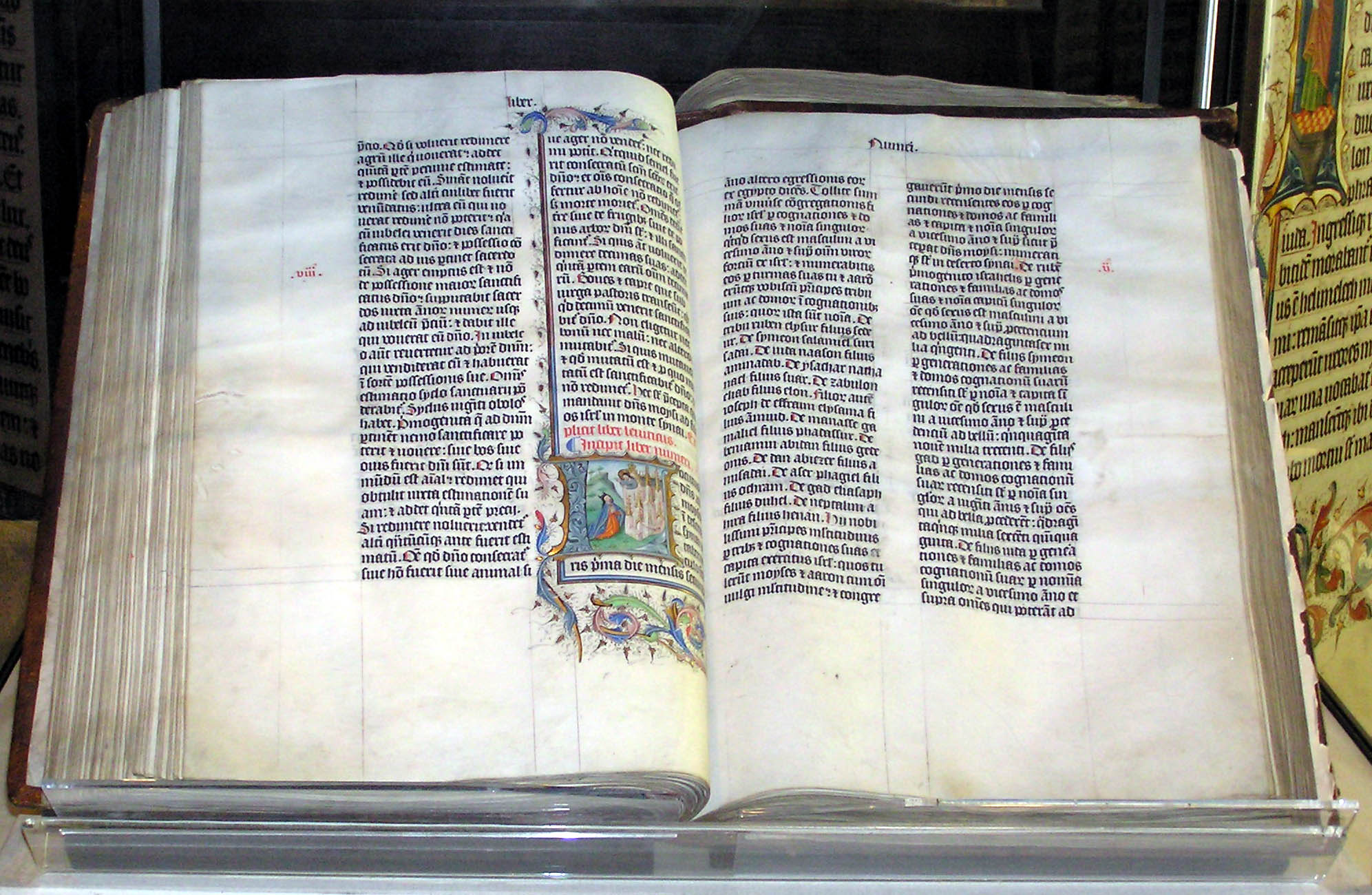

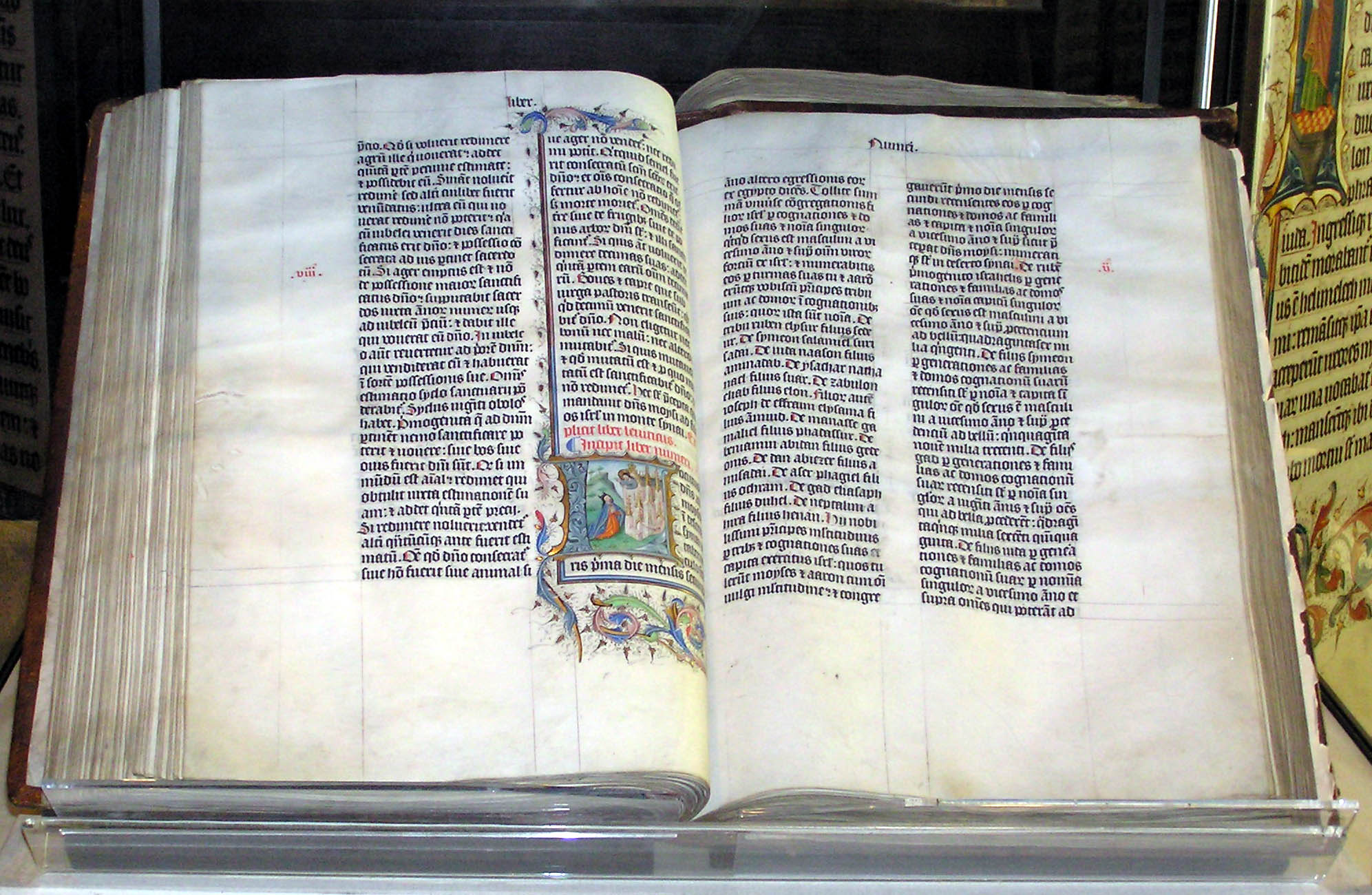

Compared to music or theater, there is less of a specifically Jewish tradition in the visual arts. The most likely and accepted reason is that, as has been previously shown with Jewish music and literature, before  A Jewish tradition of illuminated manuscripts in at least Late Antiquity has left no survivors, but can be deduced from borrowings in Early Medieval Christian art. A number of luxury pieces of gold glass from the later Roman period have Jewish motifs. Several Hellenistic-style floor mosaics have also been excavated in synagogues from Late Antiquity in Israel and Palestine, especially of the signs of the Zodiac, which was apparently acceptable in a low-status position on the floor. Some, such as that at Naaran, show evidence of a reaction against images of living creatures around 600 CE. The decoration of sarcophagi and walls at the cave cemetery at Beit She'arim National Park, Beit She'arim shows a mixture of Jewish and Hellenistic motifs. However, for a period of several centuries between about 700 and 1100 CE there are scarcely any survivals of identifiably Jewish art.

Jews in the Middle Ages, Middle Age Rabbinical literature, Rabbinical and Kabbalah, Kabbalistic literature also contain textual and graphic art, most famously illuminated haggadahs such as the Sarajevo Haggadah, and other manuscripts like the Nuremberg Mahzor. Some of these were illustrated by Jewish artists and some by Christians; equally some Jewish artists and craftsmen in various media worked on Christian commissions. Outside of Europe, Yemeni silver, Yemenite Jewish silversmiths developed a distinctive style of finely wrought silver that is admired for its artistry. Johnson again summarizes this sudden change from a limited participation by Jews in visual art (as in many other arts) to a large movement by them into this branch of European cultural life:

A Jewish tradition of illuminated manuscripts in at least Late Antiquity has left no survivors, but can be deduced from borrowings in Early Medieval Christian art. A number of luxury pieces of gold glass from the later Roman period have Jewish motifs. Several Hellenistic-style floor mosaics have also been excavated in synagogues from Late Antiquity in Israel and Palestine, especially of the signs of the Zodiac, which was apparently acceptable in a low-status position on the floor. Some, such as that at Naaran, show evidence of a reaction against images of living creatures around 600 CE. The decoration of sarcophagi and walls at the cave cemetery at Beit She'arim National Park, Beit She'arim shows a mixture of Jewish and Hellenistic motifs. However, for a period of several centuries between about 700 and 1100 CE there are scarcely any survivals of identifiably Jewish art.

Jews in the Middle Ages, Middle Age Rabbinical literature, Rabbinical and Kabbalah, Kabbalistic literature also contain textual and graphic art, most famously illuminated haggadahs such as the Sarajevo Haggadah, and other manuscripts like the Nuremberg Mahzor. Some of these were illustrated by Jewish artists and some by Christians; equally some Jewish artists and craftsmen in various media worked on Christian commissions. Outside of Europe, Yemeni silver, Yemenite Jewish silversmiths developed a distinctive style of finely wrought silver that is admired for its artistry. Johnson again summarizes this sudden change from a limited participation by Jews in visual art (as in many other arts) to a large movement by them into this branch of European cultural life:

There were few Jewish ''secular'' artists in Europe prior to the

There were few Jewish ''secular'' artists in Europe prior to the  During the early 20th century Jews figured particularly prominently in the Montparnasse movement, and after World War II among the abstract expressionism, abstract expressionists: Alexander Bogen, Helen Frankenthaler, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Al Held, Lee Krasner, Barnett Newman, Milton Resnick, Jack Tworkov, Mark Rothko, and Louis Schanker as well as among List of contemporary artists, Contemporary artists, List of modern artists, Modernists and Postmodern art, Postmodernists. Many History of the Jews in Russia, Russian Jews were prominent in the art of scenic design, particularly the aforementioned Chagall and Aronson, as well as the revolutionary Léon Bakst, who like the other two also painted. One List of Mexican Jews, Mexican Jewish artist was Pedro Friedeberg; historians disagree as to whether Frida Kahlo's father was Jewish or Lutheran. Gustav Klimt was not Jewish, but nearly all of his patrons and several of his models were. Among major artists Chagall may be the most specifically Jewish in his themes. But as art fades into graphic design, Jewish names and themes become more prominent: Leonard Baskin, Al Hirschfeld, Peter Max,

During the early 20th century Jews figured particularly prominently in the Montparnasse movement, and after World War II among the abstract expressionism, abstract expressionists: Alexander Bogen, Helen Frankenthaler, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Al Held, Lee Krasner, Barnett Newman, Milton Resnick, Jack Tworkov, Mark Rothko, and Louis Schanker as well as among List of contemporary artists, Contemporary artists, List of modern artists, Modernists and Postmodern art, Postmodernists. Many History of the Jews in Russia, Russian Jews were prominent in the art of scenic design, particularly the aforementioned Chagall and Aronson, as well as the revolutionary Léon Bakst, who like the other two also painted. One List of Mexican Jews, Mexican Jewish artist was Pedro Friedeberg; historians disagree as to whether Frida Kahlo's father was Jewish or Lutheran. Gustav Klimt was not Jewish, but nearly all of his patrons and several of his models were. Among major artists Chagall may be the most specifically Jewish in his themes. But as art fades into graphic design, Jewish names and themes become more prominent: Leonard Baskin, Al Hirschfeld, Peter Max,

In 1952, William Gaines and Harvey Kurtzman founded ''Mad (magazine), Mad'', an American humor magazine. It was widely imitated and influential, affecting satire, satirical media as well as the cultural landscape of the 20th century, with editor Al Feldstein increasing readership to more than two million during its 1970s circulation peak. Other known cartoonists are Lee Falk creator of ''The Phantom'' and ''Mandrake the Magician''; The Hebrew comics of Michael Netzer creator of Uri-On and Uri Fink creator of Zbeng!; William Steig, creator of ''Shrek!''; Daniel Clowes, creator of ''Eightball (comics), Eightball''; Art Spiegelman creator of graphic novel ''Maus'' and ''Raw (magazine), Raw'' (with Françoise Mouly).

In animation, Jewish animators role is expressed by many: Genndy Tartakovsky is the creator of several animation TV series such as ''Dexter's Laboratory'' and ''Samurai Jack''; Matt Stone co-creator of ''South Park''; David Hilberman who helped animate ''Bambi'' and ''Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937 film), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs''; Friz Freleng, ''Looney Tunes'';C. H. Greenblatt,''Chowder (TV series), Chowder''; and ''Harvey Beaks''; Ralph Bakshi, ''Fritz the Cat (film), Fritz the Cat, Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, Wizards (film), Wizards, The Lord of the Rings (1978 film), The Lord of the Rings, Heavy Traffic, Coonskin (film), Coonskin, Hey Good Lookin' (film), Hey Good Lookin', Fire and Ice (1983 film), Fire and Ice'', and ''Cool World''; Alex Hirsch, creator of ''Gravity Falls''; Dave Fleischer and Lou Fleischer, founders of ''Fleischer Studios''; Max Fleischer, animation of ''Betty Boop'', ''Popeye'' and ''Superman''; Rebecca Sugar, creator of Steven Universe. Several companies producing animation were founded by Jews, such as ''DreamWorks Pictures, DreamWorks'', which its products include ''Shrek, Madagascar (franchise), Madagascar, Kung Fu Panda (film), Kung Fu Panda'' and ''The Prince of Egypt''; ''Warner Bros.'', whose Warner Bros. Animation, animation division is known for cartoons such as ''Looney Tunes, Tiny Toon Adventures, Animaniacs, Pinky and the Brain'' and ''Freakazoid!'' .

In 1952, William Gaines and Harvey Kurtzman founded ''Mad (magazine), Mad'', an American humor magazine. It was widely imitated and influential, affecting satire, satirical media as well as the cultural landscape of the 20th century, with editor Al Feldstein increasing readership to more than two million during its 1970s circulation peak. Other known cartoonists are Lee Falk creator of ''The Phantom'' and ''Mandrake the Magician''; The Hebrew comics of Michael Netzer creator of Uri-On and Uri Fink creator of Zbeng!; William Steig, creator of ''Shrek!''; Daniel Clowes, creator of ''Eightball (comics), Eightball''; Art Spiegelman creator of graphic novel ''Maus'' and ''Raw (magazine), Raw'' (with Françoise Mouly).

In animation, Jewish animators role is expressed by many: Genndy Tartakovsky is the creator of several animation TV series such as ''Dexter's Laboratory'' and ''Samurai Jack''; Matt Stone co-creator of ''South Park''; David Hilberman who helped animate ''Bambi'' and ''Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937 film), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs''; Friz Freleng, ''Looney Tunes'';C. H. Greenblatt,''Chowder (TV series), Chowder''; and ''Harvey Beaks''; Ralph Bakshi, ''Fritz the Cat (film), Fritz the Cat, Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, Wizards (film), Wizards, The Lord of the Rings (1978 film), The Lord of the Rings, Heavy Traffic, Coonskin (film), Coonskin, Hey Good Lookin' (film), Hey Good Lookin', Fire and Ice (1983 film), Fire and Ice'', and ''Cool World''; Alex Hirsch, creator of ''Gravity Falls''; Dave Fleischer and Lou Fleischer, founders of ''Fleischer Studios''; Max Fleischer, animation of ''Betty Boop'', ''Popeye'' and ''Superman''; Rebecca Sugar, creator of Steven Universe. Several companies producing animation were founded by Jews, such as ''DreamWorks Pictures, DreamWorks'', which its products include ''Shrek, Madagascar (franchise), Madagascar, Kung Fu Panda (film), Kung Fu Panda'' and ''The Prince of Egypt''; ''Warner Bros.'', whose Warner Bros. Animation, animation division is known for cartoons such as ''Looney Tunes, Tiny Toon Adventures, Animaniacs, Pinky and the Brain'' and ''Freakazoid!'' .

Jewish cooking combines the food of many cultures in which Jews have settled, including Middle Eastern cuisine, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, Spanish cuisine, Spanish, German cuisine, German and Eastern European cuisine, Eastern European styles of cooking, all influenced by the need for food to be kosher. Thus, "Jewish" foods like bagels,Roden, Claudia (1996). "The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York”

Jewish cooking combines the food of many cultures in which Jews have settled, including Middle Eastern cuisine, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, Spanish cuisine, Spanish, German cuisine, German and Eastern European cuisine, Eastern European styles of cooking, all influenced by the need for food to be kosher. Thus, "Jewish" foods like bagels,Roden, Claudia (1996). "The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York”

Excerpt

retrieved April 7, 2015, from My Jewish Learning hummus, stuffed cabbage, and blintzes all come from various other cultures. The amalgam of these foods, plus uniquely Jewish contributions like tzimmis, cholent, gefilte fish and matzah balls, make up Jewish cuisine.

Why South Koreans are in love with Judaism

. ''The Jewish Chronicle''. May 12, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2014. and China.Nagler-Cohen, Liron.

. ''Ynetnews''. April 23, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2014. In general, Jews are positively stereotyped as intelligent, business savvy and committed to family values and responsibility, while in the Western world, the first of the two aforementioned stereotypes more often have the negatively interpreted equivalents of guile and greed. In South Korean primary schools the

The center for Jewish Art Collection

The City Congregation for Humanistic Judaism

Congress of Secular Jewish Organizations

Global Directory of Jewish Museums

News and reviews about Jewish literature and books

The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art

Heeb – an online magazine about Jewish culture

Gesher Galicia

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jewish Culture Jewish culture, Secular Jewish culture, Haskalah

Jewish culture is the culture of the

Jewish culture is the culture of the Jewish people

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

, from its formation in ancient times until the current age. Judaism itself is not a faith-based religion, but an orthoprax and ethnoreligion

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a s ...

, pertaining to deed, practice, and identity. Jewish culture covers many aspects, including religion and worldviews, literature, media, and cinema, art and architecture, cuisine and traditional dress, attitudes to gender, marriage, and family, social customs and lifestyles, music and dance. Some elements of Jewish culture come from within Judaism, others from the interaction of Jews with host populations, and others still from the inner social and cultural dynamics of the community. Before the 18th century, religion dominated virtually all aspects of Jewish life, and infused culture. Since the advent of secularization

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

, wholly secular Jewish culture emerged likewise.

History

There has not been a political unity of Jewish society since theunited monarchy

The United Monarchy () in the Hebrew Bible refers to Israel and Judah under the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon. It is traditionally dated to have lasted between and . According to the biblical account, on the succession of Solomon's son Re ...

. Since then Israelite

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

populations were always geographically dispersed (see Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( he, תְּפוּצָה, təfūṣā) or exile (Hebrew: ; Yiddish: ) is the dispersion of Israelites or Jews out of their ancient ancestral homeland (the Land of Israel) and their subsequent settlement in other parts of th ...

), so that by the 19th century the Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

were mainly located in Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Central Europe; the Sephardi Jews

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

were largely spread among various communities which lived in the Mediterranean region

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

; Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews ( he, יהודי המִזְרָח), also known as ''Mizrahim'' () or ''Mizrachi'' () and alternatively referred to as Oriental Jews or ''Edot HaMizrach'' (, ), are a grouping of Jewish communities comprising those who remained ...

were primarily spread throughout Western Asia; and other populations of Jews lived in Central Asia, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

, and India. (See Jewish ethnic divisions.)

Although there was a high degree of communication and traffic between these Jewish communities – many Sephardic exiles blended into the Ashkenazi communities which existed in Central Europe following the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

; many Ashkenazim migrated to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, giving rise to the characteristic Syrian-Jewish family name "Ashkenazi"; Iraqi-Jewish traders formed a distinct Jewish community

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

in India; to some degree, many of these Jewish populations were cut off from the cultures which surrounded them by ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

ization, Muslim laws of ''dhimma

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

'', and the traditional discouragement of contact between Jews and members of polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

populations by their religious leaders.

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

Jewish communities in Eastern Europe continued to display distinct cultural traits over the centuries. Despite the universalist leanings of the Enlightenment (and its echo within Judaism in the Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

movement), many Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

-speaking Jews in Eastern Europe continued to see themselves as forming a distinct national group — ''" 'am yehudi"'', from the Biblical Hebrew – but, adapting this idea to Enlightenment values, they assimilated the concept as that of an ethnic group whose identity did not depend on religion, which under Enlightenment thinking fell under a separate category.

Constantin Măciucă writes of the existence of "a differentiated but not isolated Jewish spirit" permeating the culture of Yiddish-speaking Jews. This was only intensified as the rise of Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

amplified the sense of national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity ...

across Europe generally. Thus, for example, members of the General Jewish Labour Bund in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were generally non-religious, and one of the historical leaders of the Bund was the child of converts to Christianity, though not a practicing or believing Christian himself.

The Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

combined with the Jewish Emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It in ...

movement under way in Central and Western Europe to create an opportunity for Jews to enter secular society. At the same time, pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s in Eastern Europe provoked a surge of migration, in large part to the United States, where some 2 million Jewish immigrants resettled between 1880 and 1920.

By 1931, shortly before The Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, 92% of the World's Jewish population was Ashkenazi in origin. Secularism originated in Europe as series of movements that militated for a new, heretofore unheard-of concept called "secular Judaism". For these reasons, much of what is thought of by English-speakers and, to a lesser extent, by non-English-speaking Europeans as "secular Jewish culture" is, in essence, the Jewish cultural movement that evolved in Central and Eastern Europe, and subsequently brought to North America by immigrants.

During the 1940s, the Holocaust uprooted and destroyed most of the Jewish communities living in much of Europe. This, in combination with the creation of the State of Israel

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executive ...

and the consequent Jewish exodus from Arab lands, resulted in a further geographic shift.

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses ...

.) Gary Tobin, head of the Institute for Jewish and Community Research, said of traditional Jewish culture:

The dichotomy between religion and culture doesn't really exist. Every religious attribute is filled with culture; every cultural act filled with religiosity. Synagogues themselves are great centers of Jewish culture. After all, what is life really about? Food, relationships, enrichment … So is Jewish life. So many of our traditions inherently contain aspects of culture. Look at the Passover Seder — it's essentially great theater. Jewish education and religiosity bereft of culture is not as interesting.Yaakov Malkin, Professor of Aesthetics and Rhetoric at

Tel Aviv University

Tel Aviv University (TAU) ( he, אוּנִיבֶרְסִיטַת תֵּל אָבִיב, ''Universitat Tel Aviv'') is a public research university in Tel Aviv, Israel. With over 30,000 students, it is the largest university in the country. Locate ...

and the founder and academic director of Meitar College for Judaism as Culture in Jerusalem, writes:

Today very many secular Jews take part in Jewish cultural activities, such as celebrating Jewish holidays as historical and nature festivals, imbued with new content and form, or marking life-cycle events such as birth, bar/bat mitzvah, marriage, and mourning in a secular fashion. They come together to study topics pertaining to Jewish culture and its relation to other cultures, in ''havurot'', cultural associations, and secular synagogues, and they participate in public and political action coordinated by secular Jewish movements, such as the former movement to free Soviet Jews, and movements to combat pogroms, discrimination, and religious coercion. Jewish secular humanistic education inculcates universal moral values through classic Jewish and world literature and through organizations for social change that aspire to ideals of justice and charity.Malkin, Y. "Humanistic and secular Judaisms." ''Modern Judaism An Oxford Guide'', p. 107.In North America, the secular and cultural Jewish movements are divided into three umbrella organizations: the

Society for Humanistic Judaism

The Society for Humanistic Judaism (SHJ), founded by Rabbi Sherwin Wine in 1969, is an American 501(c)(3) organization and the central body of Humanistic Judaism, a philosophy that combines a non-theistic and humanistic outlook with the celebrat ...

(SHJ), the Congress of Secular Jewish Organizations (CSJO), and Workmen's Circle

The Workers Circle or Der Arbeter Ring ( yi, דער אַרבעטער־רינג), formerly The Workmen's Circle, is an American Jewish nonprofit organization that promotes social and economic justice, Jewish community and education, including Yiddi ...

.

Philosophy

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, and their nation, religion, and culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions, and cultures. Although Judaism as a religion first appears in Greek records during the Hellenisti ...

, including the ancient and biblical era, medieval era and modern era (see Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

).

The ancient Jewish philosophy is expressed in the bible. According to Prof. Israel Efros the principles of the Jewish philosophy start in the bible, where the foundations of the Jewish monotheistic beliefs can be found, such as the belief in one god

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford ...

, the separation of god and the world and nature (as opposed to Pantheism

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ...

) and the creation of the world. Other biblical writings that associated with philosophy are Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

that contains invitations to admire the wisdom of God through his works; from this, some scholars suggest, Judaism harbors a Philosophical under-current and Ecclesiastes that is often considered to be the only genuine philosophical work in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Deuterocanonical books The deuterocanonical books (from the Greek meaning "belonging to the second canon") are books and passages considered by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Assyrian Church of the East to be ...

such as '' Deuterocanonical books The deuterocanonical books (from the Greek meaning "belonging to the second canon") are books and passages considered by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Assyrian Church of the East to be ...

Sirach

The Book of Sirach () or Ecclesiasticus (; abbreviated Ecclus.) is a Jewish work, originally in Hebrew, of ethical teachings, from approximately 200 to 175 BC, written by the Judahite scribe Ben Sira of Jerusalem, on the inspiration of his fa ...

and Book of Wisdom

The Book of Wisdom, or the Wisdom of Solomon, is a Jewish work written in Greek and most likely composed in Alexandria, Egypt. Generally dated to the mid-first century BCE, the central theme of the work is "wisdom" itself, appearing under two ...

.

During the Hellenistic era

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

, Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellenistic Judaism wer ...

aspired to combine Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture and philosophy. The philosopher Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

used philosophical allegory to attempt to fuse and harmonize Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empi ...

with Jewish philosophy. His work attempts to combine Plato and Moses into one philosophical system. He developed an allegoric approach of interpreting holy scriptures (the bible), in contrast to (old-fashioned) literally interpretation approaches. His allegorical exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

was important for several Christian Church Fathers and some scholars hold that his concept of the Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Ari ...

as God's creative principle influenced early Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

. Other scholars, however, deny direct influence but say both Philo and Early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewis ...

borrow from a common source.

Between the

Between the Ancient era

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

and the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

most of the Jewish philosophy concentrated around the Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writ ...

that is expressed in the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

and Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

. In the 9th century ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

Saadia Gaon

Saʻadiah ben Yosef Gaon ( ar, سعيد بن يوسف الفيومي ''Saʻīd bin Yūsuf al-Fayyūmi''; he, סַעֲדְיָה בֶּן יוֹסֵף אַלְפַיּוּמִי גָּאוֹן ''Saʿăḏyāh ben Yōsēf al-Fayyūmī Gāʾōn''; ...

wrote the text Emunoth ve-Deoth

''The Book of Beliefs and Opinions'' ( ar, كتاب الأمانات والاعتقادات, translit=Kitāb al-Amānāt wa l-Iʿtiqādāt) is a book written by Saadia Gaon (completed 933) which is the first systematic presentation and philosophi ...

which is the first systematic presentation and philosophic foundation of the dogmas

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam o ...

of Judaism. The Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain

The golden age of Jewish culture in Spain, which coincided with the Middle Ages in Europe, was a period of Muslim rule during which, intermittently, Jews were generally accepted in society and Jewish religious, cultural, and economic life flou ...

included many influential Jewish philosophers such as Moses ibn Ezra

Rabbi Moses ben Jacob ibn Ezra, known as Ha-Sallaḥ ("writer of penitential prayers") ( ar, أَبُو هَارُون مُوسَى بِن يَعْقُوب اِبْن عَزْرَا, ''Abu Harun Musa bin Ya'qub ibn 'Azra'', he, מֹשֶׁה ב ...

, Abraham ibn Ezra, Solomon ibn Gabirol, Yehuda Halevi

Judah Halevi (also Yehuda Halevi or ha-Levi; he, יהודה הלוי and Judah ben Shmuel Halevi ; ar, يهوذا اللاوي ''Yahuḏa al-Lāwī''; 1075 – 1141) was a Spanish Jewish physician, poet and philosopher. He was born in Spain, ...

, Isaac Abravanel

Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel ( he, יצחק בן יהודה אברבנאל; 1437–1508), commonly referred to as Abarbanel (), also spelled Abravanel, Avravanel, or Abrabanel, was a Portuguese Jewish statesman, philosopher, Bible commentator ...

, Nahmanides

Moses ben Nachman ( he, מֹשֶׁה בֶּן־נָחְמָן ''Mōše ben-Nāḥmān'', "Moses son of Nachman"; 1194–1270), commonly known as Nachmanides (; el, Ναχμανίδης ''Nakhmanídēs''), and also referred to by the acronym Ra ...

, Joseph Albo

Joseph Albo ( he, יוסף אלבו; c. 1380–1444) was a Jewish philosopher and rabbi who lived in Spain during the fifteenth century, known chiefly as the author of '' Sefer ha-Ikkarim'' ("Book of Principles"), the classic work on the fundament ...

, Abraham ibn Daud

Abraham ibn Daud ( he, אַבְרָהָם בֵּן דָּוִד הַלֵּוִי אִבְּן דָּאוּד; ar, ابراهيم بن داود) was a Spanish-Jewish astronomer, historian, and philosopher; born at Córdoba, Spain about 1110; die ...

, Nissim of Gerona

Nissim ben Reuven (1320 – 9th of Shevat, 1376, he, נִסִּים בֶּן רְאוּבֵן) of Girona, Catalonia was an influential talmudist and authority on Jewish law. He was one of the last of the great Spanish medieval Talmudic scholars. ...

, Bahya ibn Paquda, Abraham bar Hiyya

Abraham bar Ḥiyya ha-Nasi (;

– 1136 or 1145), also known as Abraham Savasorda, Abraham Albargeloni, and Abraham Judaeus, was a Catalan Jewish mathematician, astronomer and philosopher who resided in Barcelona.

Bar Ḥiyya was active in tra ...

, Joseph ibn Tzaddik

Rabbi Joseph ben Jacob ibn Tzaddik (died 1149) was a Spanish rabbi, poet, and philosopher. A Talmudist of high repute, he was appointed in 1138 dayyan at Córdoba, Spain, Cordova, which office he held conjointly with Maimon, father of Maimonides, ...

, Hasdai Crescas

Hasdai ben Abraham Crescas (; he, חסדאי קרשקש; c. 1340 in Barcelona – 1410/11 in Zaragoza) was a Spanish-Jewish philosopher and a renowned halakhist (teacher of Jewish law). Along with Maimonides ("Rambam"), Gersonides ("Ralbag"), ...

and Isaac ben Moses Arama. The most notable is Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

who is considered, beside the Jewish world, to be a prominent philosopher and polymath in the Islamic and Western worlds. Outside of Spain, other philosophers are Natan'el al-Fayyumi

Natan'el al-Fayyumi (also known as Nathanel ben Fayyumi), born about 1090 – died about 1165, of Yemen was the twelfth-century author of ''Bustan al-Uqul'' (Hebrew: ''Gan HaSikhlim''; Garden of the Intellects), a Jewish version of Ismaili Shi'i do ...

, Elia del Medigo, Jedaiah ben Abraham Bedersi Jedaiah ben Abraham Bedersi (c. 1270 – c. 1340) ( he, ) was a Jewish poet, physician, and philosopher; born at Béziers (hence his surname Bedersi). His Occitan name was En Bonet, which probably corresponds to the Hebrew name Tobiah;compare ...

and Gersonides

Levi ben Gershon (1288 – 20 April 1344), better known by his Graecized name as Gersonides, or by his Latinized name Magister Leo Hebraeus, or in Hebrew by the abbreviation of first letters as ''RaLBaG'', was a medieval French Jewish philosoph ...

.

Philosophy by Jews in Modern era was expressed by philosophers, mainly in Europe, such as Baruch Spinoza founder of Spinozism

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

, whose work included modern Rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

and Biblical criticism and laying the groundwork for the 18th-century Enlightenment. His work has earned him recognition as one of Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

's most important thinkers; Others are Isaac Orobio de Castro, Tzvi Ashkenazi

Tzvi Hirsch ben Yaakov Ashkenazi ( he, צבי אשכנזי; 1656 – May 2, 1718), known as the Chacham Tzvi after his responsa by the same title, served for some time as rabbi of Amsterdam. He was a resolute opponent of the followers of the fal ...

, David Nieto

David Nieto (1654 – 10 January 1728) was the Haham of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community in London, later succeeded in this capacity by his son, Isaac Nieto.

Nieto was born in Venice. He first practised as a physician and officiated ...

, Isaac Cardoso, Jacob Abendana

Jacob Abendana (1630 – 12 September 1685) was ''hakham'' of London from 1680 until his death.

Biography

Jacob was the eldest son of Joseph Abendana and brother to Isaac Abendana. Though his family originally lived in Hamburg, Jacob and his br ...

, Uriel da Costa, Francisco Sanches and Moses Almosnino. A new era began in the 18th century with the thought of Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or ' ...

. Mendelssohn has been described as the "'third Moses,' with whom begins a new era in Judaism," just as new eras began with Moses the prophet and with Moses Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah s ...

. Mendelssohn was a German Jewish philosopher to whose ideas the renaissance of European Jews, Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

(the Jewish Enlightenment) is indebted. He has been referred to as the father of Reform Judaism, though Reform spokesmen have been "resistant to claim him as their spiritual father". Mendelssohn came to be regarded as a leading cultural figure of his time by both Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

and Jews. The Jewish Enlightenment philosophy included Menachem Mendel Lefin Menachem Mendel Lefin (also Menahem Mendel Levin) (1749–1826) was an early leader of the Haskalah movement.

Biography

He was born in Satanov, Podolia, where he had a traditional Jewish education supplemented by studies in science, mathematics, a ...

, Salomon Maimon

Salomon Maimon (; ; lt, Salomonas Maimonas; he, שלמה בן יהושע מימון; 1753 – 22 November 1800) was a philosopher born of Lithuanian Jewish parentage in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, present-day Belarus. Some of his work w ...

and Isaac Satanow Isaac Satanow (born at Satanow, Poland (currently in Ukraine), 1732; died in Berlin, Germany, 25 December 1804) was a Polish-Jewish ''maskil'', scholar, and poet.

Life

Born to a Jewish family in Satanow, in early manhood he left his native countr ...

. The next 19th century comprised both secular and religious philosophy and included philosophers such as Elijah Benamozegh

Elijah Benamozegh, sometimes Elia or Eliyahu, (born 1823; died 6 February 1900) was an Italian Sephardic Orthodox rabbi and renowned Kabbalist, highly respected in his day as one of Italy's most eminent Jewish scholars. He served for half a cen ...

, Hermann Cohen

Hermann Cohen (4 July 1842 – 4 April 1918) was a German Jewish philosopher, one of the founders of the Marburg school of neo-Kantianism, and he is often held to be "probably the most important Jewish philosopher of the nineteenth century ...

, Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His socialist theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zi ...

, Samson Raphael Hirsch

Samson Raphael Hirsch (; June 20, 1808 – December 31, 1888) was a German Orthodox rabbi best known as the intellectual founder of the '' Torah im Derech Eretz'' school of contemporary Orthodox Judaism. Occasionally termed ''neo-Orthodoxy'', hi ...

, Samuel Hirsch

Samuel Hirsch, (June 8, 1815 – May 14, 1889) was a major Reform Judaism philosopher and rabbi who mainly worked and resided in present-day Germany in his earlier years. He promoted the radical German Reform Judaism movement and published several ...

, Nachman Krochmal

Nachman HaKohen Krochmal ( he, נחמן קְרוֹכְמַל; born in Brody, Galicia, on 17 February 1785; died at Ternopil on 31 July 1840) was a Jewish Galician philosopher, theologian, and historian.

Biography

He began the study of the Talmud ...

, Samuel David Luzzatto

Samuel David Luzzatto ( he, שמואל דוד לוצאטו, ; 22 August 1800 – 30 September 1865), also known by the Hebrew acronym Shadal (), was an Italian Jewish scholar, poet, and a member of the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement.

Early ...

, and Nachman of Breslov

Nachman of Breslov ( he, רַבִּי נַחְמָן מִבְּרֶסְלֶב ''Rabbī'' ''Naḥmān mīBreslev''), also known as Reb Nachman of Bratslav, Reb Nachman Breslover ( yi, רבי נחמן ברעסלאווער ''Rebe Nakhmen Breslover'' ...

founder of Breslov. The 20th century included the notable philosophers Jacques Derrida, Karl Popper, Emmanuel Levinas

Emmanuel Levinas (; ; 12 January 1906 – 25 December 1995) was a French philosopher of Lithuanian Jewish ancestry who is known for his work within Jewish philosophy, existentialism, and phenomenology, focusing on the relationship of ethics t ...

, Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss (, ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair of Social An ...

, Hilary Putnam, Alfred Tarski

Alfred Tarski (, born Alfred Teitelbaum;School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews ''School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews''. January 14, 1901 – October 26, 1983) was a Polish-American logician a ...

, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He is con ...

, A. J. Ayer, Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin (; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German Jewish philosopher, cultural critic and essayist.

An eclectic thinker, combining elements of German idealism, Romanticism, Western Marxism, and Jewish ...

, Raymond Aron

Raymond Claude Ferdinand Aron (; 14 March 1905 – 17 October 1983) was a French philosopher, sociologist, political scientist, historian and journalist, one of France's most prominent thinkers of the 20th century.

Aron is best known for his 19 ...

, Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno ( , ; born Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund; 11 September 1903 – 6 August 1969) was a German philosopher, sociologist, psychologist, musicologist, and composer.

He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of criti ...

, Isaiah Berlin and Henri Bergson.

Education and politics

A range of moral and political views is evident early in the history of Judaism, that serves to partially explain the diversity that is apparent among secular Jews who are often influenced by moral beliefs that can be found in Jewish scripture, and traditions. In recent centuries, secular Jews in Europe and the Americas have tended towards the liberalpolitical left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

, and played key roles in the birth of the 19th century's labor movement and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

. While Diaspora Jews have also been represented in the conservative side of the political spectrum, even politically conservative Jews have tended to support pluralism more consistently than many other elements of the political right

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, auth ...

. Some scholars attribute this to the fact that Jews are not expected to proselytize

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

, derived from Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

. This lack of a universalizing religion is combined with the fact that most Jews live as minorities in diaspora countries, and that no central Jewish religious authority has existed since 363 CE. Jews value education, and the value of education is strongly embedded in Jewish culture.

Economic activity

In the

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, European laws prevented Jews from owning land and gave them powerful incentive to go into other professions that non-Jewish Europeans were not willing to follow. During the medieval period, there was a very strong social stigma against lending money and charging interest among the Christian majority. In most of Europe until the late 18th century, and in some places to an even later date, Jews were prohibited by Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

governments (and others) from owning land. On the other hand, the Church, because of a number of Bible verses (e.g., Leviticus 25:36) forbidding usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is c ...

, declared that charging any interest was against the divine law, and this prevented any mercantile use of capital by pious Christians. As the Canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

did not apply to Jews, they were not liable to the ecclesiastical punishments which were placed upon usurers by the popes. Christian rulers gradually saw the advantage of having a class of men like the Jews who could supply capital for their use without being liable to excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

, and so the money trade of western Europe by this means fell into the hands of the Jews.

However, in almost every instance where large amounts were acquired by Jews through banking transactions the property thus acquired fell either during their life or upon their death into the hands of the king. This happened to Aaron of Lincoln in England, Ezmel de Ablitas Ezmel de Ablitas (died 1342), "the rich Jew of Ablitas", had business relations with the King of Navarre and Aragon. He was the son of Don Juceph; and was born in the village of Ablitas, near Tudela, Navarre, Tudela, from which place he derived his ...

in Navarre, Heliot de Vesoul in Provence, Benveniste de Porta in Aragon, etc. It was often for this reason that kings supported the Jews, and even objected to them becoming Christians (because in that case they could not be forced to give up money won by usury). Thus, both in England and in France the kings demanded to be compensated for every Jew converted. This type of royal trickery was one factor in creating the stereotypical Jewish role of banker and/or merchant.

As a modern system of capital began to develop, loans became necessary for commerce and industry. Jews were able to gain a foothold in the new field of finance by providing these services: as non-Catholics, they were not bound by the ecclesiastical prohibition against "usury"; and in terms of Judaism itself, Hillel had long ago re-interpreted the Torah's ban on charging interest, allowing interest when it's needed to make a living.

Science and technology

The strong Jewish tradition of religious scholarship often left Jews well prepared for secular scholarship. In some times and places, this was countered by banning Jews from studying at universities, or admitting them only in limited numbers (seeJewish quota

A Jewish quota was a discriminatory racial quota designed to limit or deny access for Jews to various institutions. Such quotas were widespread in the 19th and 20th centuries in developed countries and frequently present in higher education, o ...

). Over the centuries, Jews have been poorly represented among land-holding classes, but far better represented in academia, professions, finance, commerce and many scientific fields. The strong representation of Jews in science and academia is evidenced by the fact that 193 persons known to be Jews or of Jewish ancestry have been awarded the Nobel Prize, accounting for 22% of all individual recipients worldwide between 1901 and 2014. Of whom, 26% in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, 22% in chemistry and 27% in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according ...

. In the fields of mathematics and computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to practical disciplines (includi ...

, 31% of Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in comput ...

recipients and 27% of Fields Medal in mathematics were or are Jewish.

The early Jewish activity in science can be found in the

The early Jewish activity in science can be found in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' physical world The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acco ...

. '' physical world The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acco ...

Biblical cosmology

Biblical cosmology is the biblical writers' conception of the cosmos as an organised, structured entity, including its origin, order, meaning and destiny. The Bible was formed over many centuries, involving many authors, and reflects shift ...

provides sporadic glimpses that may be stitched together to form a Biblical impression of the physical universe. There have been comparisons between the Bible, with passages such as from the Genesis creation narrative, and the astronomy of classical antiquity more generally. The Old Testament also contains various cleansing rituals. One suggested ritual, for example, deals with the proper procedure for cleansing a leper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

(). It is a fairly elaborate process, which is to be performed after a leper was already healed of leprosy (), involving extensive cleansing and personal hygiene, but also includes sacrificing a bird and lambs with the addition of using their blood to symbolize that the afflicted has been cleansed.

The Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

proscribes Intercropping

Intercropping is a multiple cropping practice that involves growing two or more crops in proximity. In other words, intercropping is the cultivation of two or more crops simultaneously on the same field. The most common goal of intercropping is ...

(Lev. 19:19, Deut 22:9), a practice often associated with sustainable agriculture and organic farming in modern agricultural science. The Mosaic code has provisions concerning the conservation of natural resources, such as trees () and birds ().

During Medieval era astronomy was a primary field among Jewish scholars and was widely studied and practiced. Prominent astronomers included Abraham Zacuto who published in 1478 his Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

book ''Ha-hibbur ha-gadol''"Zacuto, Abraham" in Glick, T., S.J. Livesy and F. Williams, editors, (2005) ''Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia'', New York Routledge. where he wrote about the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

, charting the positions of the Sun, Moon and five planets. His work served Portugal's exploration journeys and was used by Vasco da Gama and also by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

. The lunar crater

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wor ...

'' Zagut'' is named after Zacuto's name. The mathematician and astronomer Abraham bar Hiyya

Abraham bar Ḥiyya ha-Nasi (;

– 1136 or 1145), also known as Abraham Savasorda, Abraham Albargeloni, and Abraham Judaeus, was a Catalan Jewish mathematician, astronomer and philosopher who resided in Barcelona.

Bar Ḥiyya was active in tra ...

Ha-Nasi authored the first European book to include the full solution to the quadratic equation x2 – ax + b = 0, and influenced the work of Leonardo Fibonacci

Fibonacci (; also , ; – ), also known as Leonardo Bonacci, Leonardo of Pisa, or Leonardo Bigollo Pisano ('Leonardo the Traveller from Pisa'), was an Italian mathematician from the Republic of Pisa, considered to be "the most talented Western ...

. Bar Hiyya proved by the method of indivisibles

In geometry, Cavalieri's principle, a modern implementation of the method of indivisibles, named after Bonaventura Cavalieri, is as follows:

* 2-dimensional case: Suppose two regions in a plane are included between two parallel lines in that p ...

the following equation for any circle: S = LxR/2, where S is the surface area, L is the circumference length and R is radius.

Garcia de Orta

Garcia de Orta (or Garcia d'Orta) (1501 – 1568) was a Sephardic Jewish physician, herbalist and naturalist of the Portuguese Renaissance, who worked primarily in the former Portuguese capital of Goa and the Bombay territory (Chaul, Bassein & D ...

, Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

Jewish physician, was a pioneer of Tropical medicine. He published his work Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India in 1563, which deals with a series of substances, many of them unknown or the subject of confusion and misinformation in Europe at this period. He was the first European to describe Asiatic tropical diseases, notably cholera; he performed an autopsy on a cholera victim, the first recorded autopsy in India. Bonet de Lattes known chiefly as the inventor of an astronomical ring-dial by means of which solar and stellar altitudes can be measured and the time determined with great precision by night as well as by day. Other related personalities are Abraham ibn Ezra, whose the Moon crater '' Abenezra'' named after, David Gans

David Gans ( he, דָּוִד בֶּן שְׁלֹמֹה גנז; 1541–1613), also known as Rabbi Dovid Solomon Ganz, was a Jewish chronicler, mathematician, historian, astronomer and astrologer. He is the author of "Tzemach David" (1592 ...

, Judah ibn Verga, Mashallah ibn Athari an astronomer, The crater '' Messala'' on the Moon is named after him.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

was a German-born theoretical physicist and is considered one of the most prominent scientists in history, often regarded as the "father of modern physics". His revolutionary work on the relativity theory

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical phenomena in ...

transformed theoretical physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

during the 20th century. When first published, relativity superseded a 200-year-old theory of mechanics created primarily by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

. In the field of physics, relativity improved the science of elementary particles

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. Particles currently thought to be elementary include electrons, the fundamental fermions (quarks, leptons, anti ...

and their fundamental interactions, along with ushering in the nuclear age

The Atomic Age, also known as the Atomic Era, is the period of history following the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, The Gadget at the ''Trinity'' test in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, during World War II. Although nuclear chain reacti ...

. With relativity, cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

and astrophysics predicted extraordinary astronomical phenomena such as neutron stars

A neutron star is the collapsed core of a massive supergiant star, which had a total mass of between 10 and 25 solar masses, possibly more if the star was especially metal-rich. Except for black holes and some hypothetical objects (e.g. white ...

, black holes, and gravitational waves

Gravitational waves are waves of the intensity of gravity generated by the accelerated masses of an orbital binary system that propagate as waves outward from their source at the speed of light. They were first proposed by Oliver Heaviside in 1 ...

.

Einstein formulated the well-known Mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame, where the two quantities differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physici ...

, ''E = mc2'', and explained the photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons when electromagnetic radiation, such as light, hits a material. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physics, and solid sta ...

. His work also effected and influenced a large variety of fields of physics including the Big Bang theory (Einstein's General relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

influenced Georges Lemaître

Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître ( ; ; 17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain. He was the first to t ...

), Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistr ...

and nuclear energy.

The

The Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

was a research and development project that produced the first atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

and many Jewish scientists had a significant role in the project. The theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experime ...

Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

, often considered the "father of the atomic bomb", was chosen to direct the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

in 1942. The physicist Leó Szilárd

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

, that conceived the nuclear chain reaction; Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, ''"the father of the hydrogen bomb''" and Stanislaw Ulam; Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his co ...

contributed to theory of Atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron ...

and Elementary particle

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. Particles currently thought to be elementary include electrons, the fundamental fermions ( quarks, leptons, a ...

; Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

whose work included Stellar nucleosynthesis and was head of the Theoretical Division at the secret Los Alamos laboratory; Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superfl ...

, Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

, Victor Weisskopf

Victor Frederick "Viki" Weisskopf (also spelled Viktor; September 19, 1908 – April 22, 2002) was an Austrian-born American theoretical physicist. He did postdoctoral work with Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Wolfgang Pauli, and Niels Boh ...

and Joseph Rotblat

Sir Joseph Rotblat (4 November 1908 – 31 August 2005) was a Polish and British physicist. During World War II he worked on Tube Alloys and the Manhattan Project, but left the Los Alamos Laboratory on grounds of conscience after it became ...

.

The mathematician and physicist Alexander Friedmann

Alexander Alexandrovich Friedmann (also spelled Friedman or Fridman ; russian: Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Фри́дман) (June 16 .S. 4 1888 – September 16, 1925) was a Russian and Soviet physicist and mathematician ...

pioneered the theory that universe was expanding governed by a set of equations he developed now known as the Friedmann equations