Czechoslovakia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–1939

1945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary , image_p1 = , s1 = Czech Republic , flag_s1 = Flag of the Czech Republic.svg , s2 = Slovakia , flag_s2 = Flag of Slovakia.svg , image_flag = Flag of Czechoslovakia.svg , flag = Flag of Czechoslovakia , flag_type = Flag

(1920–1992) , flag_border = Flag of Czechoslovakia , image_coat = Middle coat of arms of Czechoslovakia.svg , symbol_type = Middle coat of arms

(1918–1938 and 1945–1961) , image_map = Czechoslovakia location map.svg , image_map_caption = Czechoslovakia during the

, capital = Prague , largest_city = capital , coordinates = , official_languages = Czechoslovak, after 1948 Czech Slovak , recognised_languages = , demonym = Czechoslovak , government_type =

, title_leader = President , leader1 =

Federal Assembly (1969–1992) , era = , event_start = Proclamation , date_start = 28 October , year_start = 1918 , event1 = Munich Agreement , date_event1 = 30 September 1938 , event2 = Dissolution , date_event2 = 14 March 1939 , event3 = Re-establishment , date_event3 = 10 May 1945 , event4 = Coup d'état , date_event4 = 25 February 1948 , event5 = Soviet occupation , date_event5 = 21 August 1968 , event6 = Velvet Revolution , date_event6 = 17 – 28 November 1989 , event_end = Dissolution , date_end = 31 December , year_end = 1992 , cctld =

The area was part of the

The area was part of the

The Bohemian Kingdom ceased to exist in 1918 when it was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was founded in October 1918, as one of the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I and as part of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It consisted of the present day territories of

The Bohemian Kingdom ceased to exist in 1918 when it was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was founded in October 1918, as one of the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I and as part of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It consisted of the present day territories of

The new country was a multi-ethnic state, with Czechs and Slovaks as ''constituent peoples''. The population consisted of Czechs (51%),

The new country was a multi-ethnic state, with Czechs and Slovaks as ''constituent peoples''. The population consisted of Czechs (51%),

In September 1938, Adolf Hitler demanded control of the

In September 1938, Adolf Hitler demanded control of the

After World War II, pre-war Czechoslovakia was re-established, with the exception of Sub carpathian Ruthenia, which was annexed by the Soviet Union and incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The

After World War II, pre-war Czechoslovakia was re-established, with the exception of Sub carpathian Ruthenia, which was annexed by the Soviet Union and incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The  Carpathian Ruthenia (Podkarpatská Rus) was occupied by (and in June 1945 formally ceded to) the Soviet Union. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was the winner in the Czech lands, and the

Carpathian Ruthenia (Podkarpatská Rus) was occupied by (and in June 1945 formally ceded to) the Soviet Union. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was the winner in the Czech lands, and the  In 1968, when the reformer Alexander Dubček was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, there was a brief period of liberalization known as the

In 1968, when the reformer Alexander Dubček was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, there was a brief period of liberalization known as the

Czechoslovakia had the following constitutions during its history (1918–1992):

*Temporary constitution of 14 November 1918 (democratic): see

Czechoslovakia had the following constitutions during its history (1918–1992):

*Temporary constitution of 14 November 1918 (democratic): see

Czechoslovakia stamp reused by Slovak Republic after 18 January 1939 by overprinting country and value

online edition

*Orzoff, Andrea. ''Battle for the Castle: The Myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe 1914–1948'' (Oxford University Press, 2009)

online review

online *Paul, David. ''Czechoslovakia: Profile of a Socialist Republic at the Crossroads of Europe'' (1990). *Renner, Hans. ''A History of Czechoslovakia since 1945'' (1989). *Seton-Watson, R. W. ''A History of the Czechs and Slovaks'' (1943). *Stone, Norman, and E. Strouhal, eds.''Czechoslovakia: Crossroads and Crises, 1918–88'' (1989). *Wheaton, Bernard; Zdenek Kavav. "The Velvet Revolution: Czechoslovakia, 1988–1991" (1992). *Williams, Kieran, "Civil Resistance in Czechoslovakia: From Soviet Invasion to "Velvet Revolution", 1968–89",

in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), ''Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present'' (Oxford University Press, 2009). *Windsor, Philip, and Adam Roberts, ''Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, Repression and Resistance'' (1969). *Wolchik, Sharon L. ''Czechoslovakia: Politics, Society, and Economics'' (1990).

Online books and articles

*English/Czech

* ttps://www.britannica.com/place/Czechoslovakia Czechoslovakia by Encyclopædia Britannica* Katrin Boeckh

Crumbling of Empires and Emerging States: Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as (Multi)national Countries

in

Maps with Hungarian-language rubrics:

Border changes after the creation of CzechoslovakiaInterwar CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia after Munich Agreement

{{Authority control Eastern Bloc Former republics Former Slavic countries Soviet satellite states Geography of Central Europe History of Central Europe 1918 establishments in Czechoslovakia 1939 disestablishments in Czechoslovakia 1945 establishments in Czechoslovakia 1992 disestablishments in Czechoslovakia States and territories established in 1918 States and territories disestablished in 1939 States and territories established in 1945 States and territories disestablished in 1992 1918 establishments in Europe 1992 disestablishments in Europe Former member states of the United Nations

1945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary , image_p1 = , s1 = Czech Republic , flag_s1 = Flag of the Czech Republic.svg , s2 = Slovakia , flag_s2 = Flag of Slovakia.svg , image_flag = Flag of Czechoslovakia.svg , flag = Flag of Czechoslovakia , flag_type = Flag

(1920–1992) , flag_border = Flag of Czechoslovakia , image_coat = Middle coat of arms of Czechoslovakia.svg , symbol_type = Middle coat of arms

(1918–1938 and 1945–1961) , image_map = Czechoslovakia location map.svg , image_map_caption = Czechoslovakia during the

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

and the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, national_motto =

, anthems = , capital = Prague , largest_city = capital , coordinates = , official_languages = Czechoslovak, after 1948 Czech Slovak , recognised_languages = , demonym = Czechoslovak , government_type =

, title_leader = President , leader1 =

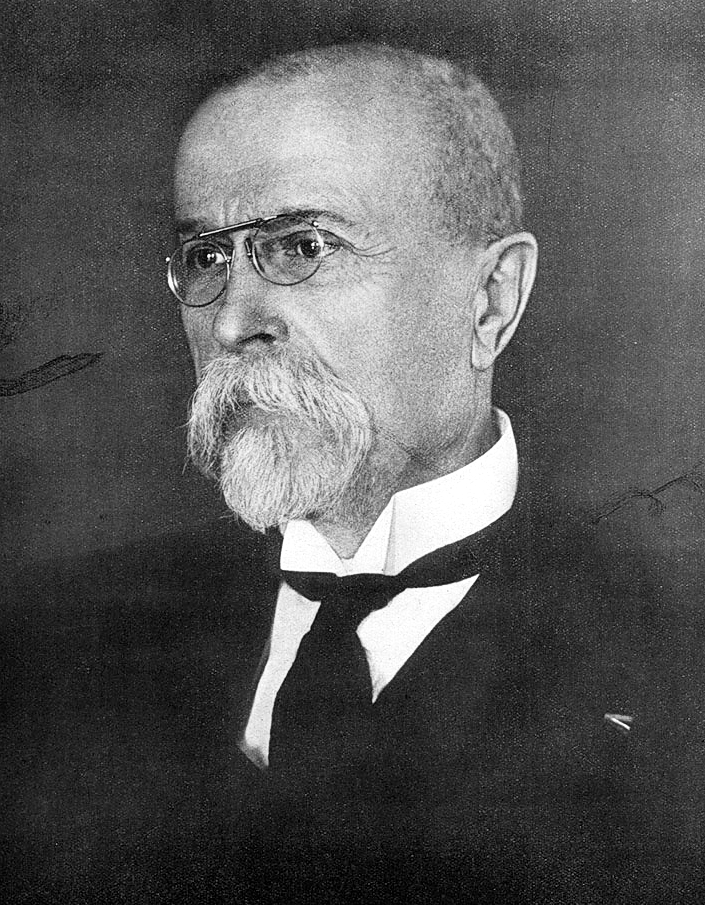

Tomáš G. Masaryk Tomáš () is a Czech and Slovak given name, equivalent to the name Thomas.

It may refer to:

* Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937), first President of Czechoslovakia

* Tomáš Baťa (1876–1932), Czech footwear entrepreneur

* Tomáš Berd ...

, year_leader1 = 1918–1935

, leader2 = Edvard Beneš

, year_leader2 =

, leader3 = Emil Hácha

, year_leader3 = 1938–1939

, leader4 = Klement Gottwald

, year_leader4 = 1948–1953

, leader5 = Antonín Zápotocký

, year_leader5 = 1953–1957

, leader6 = Antonín Novotný

, year_leader6 = 1957–1968

, leader7 = Ludvík Svoboda

, year_leader7 = 1968–1975

, leader8 = Gustáv Husák

, year_leader8 = 1976–1989

, leader9 = Václav Havel

, year_leader9 = 1989–1992

, title_representative = KSČ General Secretary / First Secretary

, representative1 = Klement Gottwald

, year_representative1 = 1948–1953

, representative2 = Antonín Novotný

, year_representative2 = 1953–1968

, representative3 = Alexander Dubček

, year_representative3 = 1968–1969

, representative4 = Gustáv Husák

, year_representative4 = 1969–1987

, representative5 = Miloš Jakeš

, year_representative5 = 1987–1989

, title_deputy = Prime Minister

, deputy1 = Karel Kramář

, year_deputy1 = 1918–1919 (first)

, deputy2 = Jan Stráský

, year_deputy2 = 1992 (last)

, legislature = National Assembly (1948–1969)Federal Assembly (1969–1992) , era = , event_start = Proclamation , date_start = 28 October , year_start = 1918 , event1 = Munich Agreement , date_event1 = 30 September 1938 , event2 = Dissolution , date_event2 = 14 March 1939 , event3 = Re-establishment , date_event3 = 10 May 1945 , event4 = Coup d'état , date_event4 = 25 February 1948 , event5 = Soviet occupation , date_event5 = 21 August 1968 , event6 = Velvet Revolution , date_event6 = 17 – 28 November 1989 , event_end = Dissolution , date_end = 31 December , year_end = 1992 , cctld =

.cs

.cs was for several years the country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Czechoslovakia. However, the country split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993, and the two new countries were soon assigned their own ccTLDs: .cz and .sk respec ...

, calling_code = +42

, HDI = 0.810

, HDI_ref =

, HDI_year = 1992

, currency = Czechoslovak koruna

, drives_on = right

, footnotes = Calling code +42 was withdrawn in the winter of 1997. The number range was divided between the :Czech Republic ( +420) and :Slovak Republic ( +421).

, footnotes2 = Current ISO 3166-3 code is "CSHH".

, today =

Czechoslovakia (; Czech and sk, Československo, ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

became part of Germany, while the country lost further territories to Hungary and Poland. Between 1939 and 1945 the state ceased to exist, as Slovakia proclaimed its independence and the remaining territories in the east became part of Hungary, while in the remainder of the Czech Lands the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed. In 1939, after the outbreak of World War II, former Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš formed a government-in-exile and sought recognition from the Allies.

After World War II, the pre-1938 Czechoslovakia was reestablished, with the exception of Carpathian Ruthenia, which became part of the Ukrainian SSR (a republic of the Soviet Union). From 1948 to 1989, Czechoslovakia was part of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

with a command economy. Its economic status was formalized in membership of Comecon from 1949 and its defense status in the Warsaw Pact of 1955. A period of political liberalization in 1968, the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

, ended violently when the Soviet Union, assisted by other Warsaw Pact countries, invaded Czechoslovakia. In 1989, as Marxist–Leninist governments and communism were ending all over Central and Eastern Europe, Czechoslovaks peacefully deposed their communist government on 17 November 1989 in the Velvet Revolution. On 1 January 1993, Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the two sovereign states of the Czech Republic and Slovakia as the result of national tensions of the Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

.

Characteristics

;Form of state *1918–1938: A democratic republic championed by Tomáš Masaryk. *1938–1939: After the acquisition ofSudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

by Nazi Germany in 1938, the region gradually turned into a state with loosened connections among the Czech, Slovak, and Ruthenian parts. A strip of southern Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia was redeemed by Hungary, and the Zaolzie region was annexed by Poland.

*1939–1945: The remainder of the state was dismembered and became split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

, while the rest of Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied and annexed by Hungary. A government-in-exile continued to exist in London, supported by the United Kingdom, United States and their Allies; after the German invasion of Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, it was also recognized by the Soviet Union. Czechoslovakia adhered to the Declaration by United Nations and was a founding member of the United Nations.

*1946–1948: The country was governed by a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

with communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

ministers, including the prime minister and the minister of interior. Carpathian Ruthenia was ceded to the Soviet Union.

*1948–1989: The country became a Marxist-Leninist state under Soviet domination with a command economy. In 1960, the country officially became a socialist republic, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It was a satellite state of the Soviet Union.

*1989–1990: Czechoslovakia formally became a federal republic

A federal republic is a federation of states with a republican form of government. At its core, the literal meaning of the word republic when used to reference a form of government means: "a country that is governed by elected representatives ...

comprising the Czech Socialist Republic

The Czech Socialist Republic ( cs, Česká socialistická republika, ČSR) was a republic within the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. The name was used from 1 January 1969 to November 1989, when the previously unitary Czechoslovak state changed ...

and the Slovak Socialist Republic. In late 1989, the communist rule came to an end during the Velvet Revolution followed by the re-establishment of a democratic parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). There are a number ...

.

*1990–1992: Shortly after the Velvet Revolution, the state was renamed the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic

After the Velvet Revolution in late-1989, Czechoslovakia adopted the official short-lived country name Czech and Slovak Federative Republic ( cz, Česká a Slovenská Federativní Republika, sk, Česká a Slovenská Federatívna Republika; ''� ...

, consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

(Slovakia) until the peaceful dissolution on 31 December 1992.

;Neighbors

* Austria 1918–1938, 1945–1992

*Germany (both predecessors, West Germany and East Germany, were neighbors between 1949 and 1990)

* Hungary

* Poland

* Romania 1918–1938

* Soviet Union 1945–1991

* Ukraine 1991–1992 ( Soviet Union member until 1991)

;Topography

The country was of generally irregular terrain. The western area was part of the north-central European uplands. The eastern region was composed of the northern reaches of the Carpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretches ...

and lands of the Danube River basin.

;Climate

The weather is mild winters and mild summers. Influenced by the Atlantic Ocean from the west, the Baltic Sea from the north, and Mediterranean Sea from the south. There is no continental weather.

Names

*1918–1938: Czechoslovak Republic (abbreviated ČSR), or Czechoslovakia, before the formalization of the name in 1920, also known as Czecho-Slovakia or the Czecho-Slovak state *1938–1939: Czecho-Slovak Republic, or Czecho-Slovakia *1945–1960: Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR), or Czechoslovakia *1960–1989: Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR), or Czechoslovakia *1990–1992:Czech and Slovak Federative Republic

After the Velvet Revolution in late-1989, Czechoslovakia adopted the official short-lived country name Czech and Slovak Federative Republic ( cz, Česká a Slovenská Federativní Republika, sk, Česká a Slovenská Federatívna Republika; ''� ...

(ČSFR), or Czechoslovakia

History

Origins

The area was part of the

The area was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

until it collapsed at the end of World War I. The new state was founded by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, who served as its first president from 14 November 1918 to 14 December 1935. He was succeeded by his close ally Edvard Beneš (1884–1948).

The roots of Czech nationalism go back to the 19th century, when philologists and educators, influenced by Romanticism, promoted the Czech language and pride in the Czech people

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, c ...

. Nationalism became a mass movement in the second half of the 19th century. Taking advantage of the limited opportunities for participation in political life under Austrian rule, Czech leaders such as historian František Palacký (1798–1876) founded various patriotic, self-help organizations which provided a chance for many of their compatriots to participate in communal life before independence. Palacký supported Austro-Slavism and worked for a reorganized federal Austrian Empire, which would protect the Slavic speaking peoples of Central Europe against Russian and German threats.

An advocate of democratic reform and Czech autonomy within Austria-Hungary, Masaryk was elected twice to the '' Reichsrat'' (Austrian Parliament), from 1891 to 1893 for the Young Czech Party, and from 1907 to 1914 for the Czech Realist Party, which he had founded in 1889 with Karel Kramář and Josef Kaizl.

During World War I a number of Czechs and Slovaks, the Czechoslovak Legions, fought with the Allies in France and Italy, while large numbers deserted to Russia in exchange for its support for the independence of Czechoslovakia from the Austrian Empire. With the outbreak of World War I, Masaryk began working for Czech independence in a union with Slovakia. With Edvard Beneš and Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Masaryk visited several Western countries and won support from influential publicists. The Czechoslovak National Council was the main organization that advanced the claims for a Czechoslovak state.

First Czechoslovak Republic

Formation

The Bohemian Kingdom ceased to exist in 1918 when it was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was founded in October 1918, as one of the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I and as part of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It consisted of the present day territories of

The Bohemian Kingdom ceased to exist in 1918 when it was incorporated into Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was founded in October 1918, as one of the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I and as part of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It consisted of the present day territories of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Moravia, Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia. Its territory included some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. "The land consisted of modern day Czechia, Slovakia, and a region of Ukraine called Carpathian Ruthnia

Ethnicity

Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

(16%), Germans (22%), Hungarians (5%) and Rusyns (4%). Many of the Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians and Poles, '' Prague Post'', 6 July 2005 and some Slovaks, felt oppressed because the political elite did not generally allow political autonomy for minority ethnic groups. This policy led to unrest among the non-Czech population, particularly in German-speaking Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, which initially had proclaimed itself part of the Republic of German-Austria in accordance with the self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

principle.

The state proclaimed the official ideology that there were no separate Czech and Slovak nations, but only one nation of Czechoslovaks (see Czechoslovakism), to the disagreement of Slovaks and other ethnic groups. Once a unified Czechoslovakia was restored after World War II (after the country had been divided during the war), the conflict between the Czechs and the Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

surfaced again. The governments of Czechoslovakia and other Central European nations deported ethnic Germans, reducing the presence of minorities in the nation. Most of the Jews had been killed during the war by the Nazis.

''*Jews identified themselves as Germans or Hungarians (and Jews only by religion not ethnicity), the sum is, therefore, more than 100%.''

Interwar period

During the period between the two world wars Czechoslovakia was a democratic state. The population was generally literate, and contained fewer alienated groups. The influence of these conditions was augmented by the political values of Czechoslovakia's leaders and the policies they adopted. UnderTomas Masaryk Tomas may refer to:

People

* Tomás (given name), a Spanish, Portuguese, and Gaelic given name

* Tomas (given name), a Swedish, Dutch, and Lithuanian given name

* Tomáš, a Czech and Slovak given name

* Tomas (surname), a French and Croatian surna ...

, Czech and Slovak politicians promoted progressive social and economic conditions that served to defuse discontent.

Foreign minister Beneš became the prime architect of the Czechoslovak-Romanian-Yugoslav alliance (the " Little Entente", 1921–38) directed against Hungarian attempts to reclaim lost areas. Beneš worked closely with France. Far more dangerous was the German element, which after 1933 became allied with the Nazis in Germany.

Czech-Slovak relations came to be a central issue in Czechoslovak politics during the 1930s. The increasing feeling of inferiority among the Slovaks, who were hostile to the more numerous Czechs, weakened the country in the late 1930s. Slovakia became autonomous in the fall of 1938, and by mid-1939, Slovakia had become independent, with the First Slovak Republic set up as a satellite state of Nazi Germany and the far-right Slovak People’s Party

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party ( sk, Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana), also known as the Slovak People's Party (, SĽS) or the Hlinka Party, was a far-right clerico-fascist political party with a strong Catholic fundamentalist and authoritar ...

in power .

After 1933, Czechoslovakia remained the only democracy in central and eastern Europe.

Munich Agreement, and Two-Step German Occupation

Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

. On 29 September 1938, Britain and France ceded control in the Appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governm ...

at the Munich Conference; France ignored the military alliance it had with Czechoslovakia. During October 1938, Nazi Germany occupied the Sudetenland border region, effectively crippling Czechoslovak defences.

The First Vienna Award assigned a strip of southern Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia to Hungary. Poland occupied Zaolzie, an area whose population was majority Polish, in October 1938.

On 14 March 1939, the remainder ("rump") of Czechoslovakia was dismembered by the proclamation of the Slovak State, the next day the rest of Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied and annexed by Hungary, while the following day the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed.

The eventual goal of the German state under Nazi leadership was to eradicate Czech nationality through assimilation, deportation, and extermination of the Czech intelligentsia; the intellectual elites and middle class made up a considerable number of the 200,000 people who passed through concentration camps and the 250,000 who died during German occupation. Under Generalplan Ost, it was assumed that around 50% of Czechs would be fit for Germanization. The Czech intellectual elites were to be removed not only from Czech territories but from Europe completely. The authors of Generalplan Ost believed it would be best if they emigrated overseas, as even in Siberia they were considered a threat to German rule. Just like Jews, Poles, Serbs, and several other nations, Czechs were considered to be untermenschen by the Nazi state. In 1940, in a secret Nazi plan for the Germanization of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia it was declared that those considered to be of racially Mongoloid origin and the Czech intelligentsia were not to be Germanized.

The deportation of Jews to concentration camps was organized under the direction of Reinhard Heydrich, and the fortress town of Terezín was made into a ghetto way station for Jewish families. On 4 June 1942 Heydrich died after being wounded by an assassin in Operation Anthropoid. Heydrich's successor, Colonel General Kurt Daluege, ordered mass arrests and executions and the destruction of the villages of Lidice and Ležáky. In 1943 the German war effort was accelerated. Under the authority of Karl Hermann Frank, German minister of state for Bohemia and Moravia, some 350,000 Czech laborers were dispatched to the Reich. Within the protectorate, all non-war-related industry was prohibited. Most of the Czech population obeyed quiescently up until the final months preceding the end of the war, while thousands were involved in the resistance movement.

For the Czechs of the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia, German occupation was a period of brutal oppression. Czech losses resulting from political persecution and deaths in concentration camps totaled between 36,000 and 55,000. The Jewish populations of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and Moravia (118,000 according to the 1930 census) were virtually annihilated. Many Jews emigrated after 1939; more than 70,000 were killed; 8,000 survived at Terezín. Several thousand Jews managed to live in freedom or in hiding throughout the occupation.

Despite the estimated 136,000 deaths at the hands of the Nazi regime, the population in the Reichsprotektorate saw a net increase during the war years of approximately 250,000 in line with an increased birth rate.

On 6 May 1945, the third US Army of General Patton entered Pilsen from the south west. On 9 May 1945, Soviet Red Army troops entered Prague.

Communist Czechoslovakia

Beneš decrees

The Beneš decrees, sk, Dekréty prezidenta republiky) and the Constitutional Decrees of the President of the Republic ( cz, Ústavní dekrety presidenta republiky, sk, Ústavné dekréty prezidenta republiky) were a series of laws drafted by t ...

were promulgated concerning ethnic Germans (see Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

) and ethnic Hungarians. Under the decrees, citizenship was abrogated for people of German and Hungarian ethnic origin who had accepted German or Hungarian citizenship during the occupations. In 1948, this provision was cancelled for the Hungarians, but only partially for the Germans. The government then confiscated the property of the Germans and expelled about 90% of the ethnic German population, over 2 million people. Those who remained were collectively accused of supporting the Nazis after the Munich Agreement, as 97.32% of Sudeten Germans had voted for the NSDAP in the December 1938 elections. Almost every decree explicitly stated that the sanctions did not apply to antifascists. Some 250,000 Germans, many married to Czechs, some antifascists, and also those required for the post-war reconstruction of the country, remained in Czechoslovakia. The Beneš Decrees still cause controversy among nationalist groups in the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria and Hungary.

Following the expulsion of the ethnic German population from Czechoslovakia, parts of the former Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, especially around Krnov and the surrounding villages of the Jesenik mountain region in northeastern Czechoslovakia, were settled in 1949 by Communist refugees from Northern Greece who had left their homeland as a result of the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom ...

. These Greeks made up a large proportion of the town and region's population until the late 1980s/early 1990s. Although defined as "Greeks", the Greek Communist community of Krnov and the Jeseniky region actually consisted of an ethnically diverse population, including Greek Macedonians, Slavo-Macedonians, Vlachs, Pontic Greeks and Turkish speaking Urums or Caucasus Greeks.

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

won in Slovakia. In February 1948 the Communists seized power. Although they would maintain the fiction of political pluralism through the existence of the National Front, except for a short period in the late 1960s (the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

) the country had no liberal democracy. Since citizens lacked significant electoral methods of registering protest against government policies, periodically there were street protests that became violent. For example, there were riots in the town of Plzeň in 1953, reflecting economic discontent. Police and army units put down the rebellion, and hundreds were injured but no one was killed. While its economy remained more advanced than those of its neighbors in Eastern Europe, Czechoslovakia grew increasingly economically weak relative to Western Europe.

The currency reform of 1953 caused dissatisfaction among Czechoslovak laborers. To equalize the wage rate, Czechoslovaks had to turn in their old money for new at a decreased value. The banks also confiscated savings and bank deposits to control the amount of money in circulation. In the 1950s, Czechoslovakia experienced high economic growth (averaging 7% per year), which allowed for a substantial increase in wages and living standards, thus promoting the stability of the regime.

In 1968, when the reformer Alexander Dubček was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, there was a brief period of liberalization known as the

In 1968, when the reformer Alexander Dubček was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, there was a brief period of liberalization known as the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

. In response, after failing to persuade the Czechoslovak leaders to change course, five other members of the Warsaw Pact invaded. Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia on the night of 20–21 August 1968. Soviet Communist Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev viewed this intervention as vital for the preservation of the Soviet, socialist system and vowed to intervene in any state that sought to replace Marxism-Leninism with capitalism.

In the week after the invasion there was a spontaneous campaign of civil resistance

Civil resistance is political action that relies on the use of nonviolent resistance by ordinary people to challenge a particular power, force, policy or regime. Civil resistance operates through appeals to the adversary, pressure and coercion: i ...

against the occupation. This resistance involved a wide range of acts of non-cooperation and defiance: this was followed by a period in which the Czechoslovak Communist Party leadership, having been forced in Moscow to make concessions to the Soviet Union, gradually put the brakes on their earlier liberal policies.

Meanwhile, one plank of the reform program had been carried out: in 1968–69, Czechoslovakia was turned into a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic

The Czech Socialist Republic ( cs, Česká socialistická republika, ČSR) was a republic within the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. The name was used from 1 January 1969 to November 1989, when the previously unitary Czechoslovak state changed ...

and Slovak Socialist Republic. The theory was that under the federation, social and economic inequities between the Czech and Slovak halves of the state would be largely eliminated. A number of ministries, such as education, now became two formally equal bodies in the two formally equal republics. However, the centralized political control by the Czechoslovak Communist Party severely limited the effects of federalization.

The 1970s saw the rise of the dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, represented among others by Václav Havel. The movement sought greater political participation and expression in the face of official disapproval, manifested in limitations on work activities, which went as far as a ban on professional employment, the refusal of higher education for the dissidents' children, police harassment and prison.

After 1989

In 1989, the Velvet Revolution restored democracy. This occurred at around the same time as the fall of communism in Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, East Germany and Poland. The word "socialist" was removed from the country's full name on 29 March 1990 and replaced by "federal". Pope John Paul II made a papal visit to Czechoslovakia on 21 April 1990, hailing it as a symbolic step of reviving Christianity in the newly-formed post-communist state. Czechoslovakia participated in the Gulf War with a small force of 200 troops under the command of the U.S.-led coalition. In 1992, because of growing nationalist tensions in the government, Czechoslovakia was peacefully dissolved by parliament. On 31 December 1992 it formally separated into two independent countries, the Czech Republic and theSlovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

.

Government and politics

After World War II, a political monopoly was held by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). The leader of the KSČ was '' de facto'' the most powerful person in the country during this period. Gustáv Husák was elected first secretary of the KSČ in 1969 (changed to general secretary in 1971) and president of Czechoslovakia in 1975. Other parties and organizations existed but functioned in subordinate roles to the KSČ. All political parties, as well as numerous mass organizations, were grouped under umbrella of the National Front. Human rights activists and religious activists were severely repressed.Constitutional development

History of Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

The First Czechoslovak Republic emerged from the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in October 1918. The new state consisted mostly of territories inhabited by Czechs and Slovaks, but also included areas containing majority populations of o ...

*The 1920 constitution (The Constitutional Document of the Czechoslovak Republic), democratic, in force until 1948, several amendments

*The Communist 1948 Ninth-of-May Constitution

*The Communist 1960 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic with major amendments in 1968 ( Constitutional Law of Federation), 1971, 1975, 1978, and 1989 (at which point the leading role of the Communist Party was abolished). It was amended several more times during 1990–1992 (for example, 1990, name change to Czecho-Slovakia, 1991 incorporation of the human rights charter)

Heads of state and government

* List of presidents of Czechoslovakia * List of prime ministers of CzechoslovakiaForeign policy

International agreements and membership

In the 1930s, the nation formed a military alliance with France, which collapsed in the Munich Agreement of 1938. After World War II, an active participant in Council for Mutual Economic Assistance ( Comecon), Warsaw Pact, United Nations and its specialized agencies; signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.Ladislav Cabada and Sarka Waisova, ''Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic in World Politics'' (Lexington Books; 2012)Administrative divisions

*1918–1923: Different systems in former Austrian territory (Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Moravia, a small part of Silesia) compared to former Hungarian territory (Slovakia and Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

): three lands (''země'') (also called district units (''kraje'')): Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, plus 21 counties (''župy'') in today's Slovakia and three counties in today's Ruthenia; both lands and counties were divided into districts (''okres Okres (Czech and Slovak term meaning "district" in English; from German Kreis - circle (or perimeter)) refers to administrative entities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. It is similar to Landkreis in Germany or "''okrug''" in other Slavic-speaki ...

y'').

*1923–1927: As above, except that the Slovak and Ruthenian counties were replaced by six (grand) counties (''(veľ)župy'') in Slovakia and one (grand) county in Ruthenia, and the numbers and boundaries of the ''okresy'' were changed in those two territories.

*1928–1938: Four lands (Czech: ''země'', Slovak: ''krajiny''): Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia and Sub-Carpathian Ruthenia, divided into districts (''okresy'').

*Late 1938 – March 1939: As above, but Slovakia and Ruthenia gained the status of "autonomous lands". Slovakia was called ''Slovenský štát'', with its own currency and government.

*1945–1948: As in 1928–1938, except that Ruthenia became part of the Soviet Union.

*1949–1960: 19 regions (''kraje'') divided into 270 ''okresy''.

*1960–1992: 10 ''kraje'', Prague, and (from 1970) Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approxim ...

(capital of Slovakia); these were divided into 109–114 okresy; the kraje were abolished temporarily in Slovakia in 1969–1970 and for many purposes from 1991 in Czechoslovakia; in addition, the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic were established in 1969 (without the word ''Socialist'' from 1990).

Population and ethnic groups

Economy

Before World War II, the economy was about the fourth in all industrial countries in Europe. The state was based on strong economy, manufacturing cars ( Škoda, Tatra), trams, aircraft ( Aero,Avia

Avia Motors s.r.o. is a Czech automotive manufacturer. It was founded in 1919 as an aircraft maker, and diversified into trucks after 1945. As an aircraft maker it was notable for producing biplane fighter aircraft, especially the B-534. Avia ...

), ships, ship engines ( Škoda), cannons, shoes ( Baťa), turbines, guns ( Zbrojovka Brno). It was the industrial workshop for the Austro-Hungarian empire. The Slovak lands relied more heavily on agriculture than the Czech lands.

After World War II, the economy was centrally planned, with command links controlled by the communist party, similarly to the Soviet Union. The large metallurgical industry was dependent on imports of iron and non-ferrous ores.

*Industry: Extractive industry

Extractivism is the process of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell on the world market. It exists in an economy that depends primarily on the extraction or removal of natural resources that are considered valuable for exportation w ...

and manufacturing dominated the sector, including machinery, chemicals, food processing, metallurgy, and textiles. The sector was wasteful in its use of energy, materials, and labor and was slow to upgrade technology, but the country was a major supplier of high-quality machinery, instruments, electronics, aircraft, airplane engines and arms to other socialist countries.

*Agriculture: Agriculture was a minor sector, but collectivized farms of large acreage and relatively efficient mode of production enabled the country to be relatively self-sufficient in the food supply. The country depended on imports of grains (mainly for livestock feed) in years of adverse weather. Meat production was constrained by a shortage of feed, but the country still recorded high per capita consumption of meat.

*Foreign Trade: Exports were estimated at US$17.8 billion in 1985. Exports were machinery (55%), fuel and materials (14%), and manufactured consumer goods (16%). Imports stood at an estimated US$17.9 billion in 1985, including fuel and materials (41%), machinery (33%), and agricultural and forestry products (12%). In 1986, about 80% of foreign trade was with other socialist countries.

*Exchange rate: Official, or commercial, the rate was crowns (Kčs) 5.4 per US$1 in 1987. Tourist, or non-commercial, the rate was Kčs 10.5 per US$1. Neither rate reflected purchasing power. The exchange rate on the black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

was around Kčs 30 per US$1, which became the official rate once the currency became convertible in the early 1990s.

*Fiscal year: Calendar year.

*Fiscal policy: The state was the exclusive owner of means of production in most cases. Revenue from state enterprises was the primary source of revenues followed by turnover tax. The government spent heavily on social programs, subsidies, and investment. The budget was usually balanced or left a small surplus.

Resource base

After World War II, the country was short of energy, relying on importedcrude oil

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

and natural gas from the Soviet Union, domestic brown coal, and nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

* Nuclear ...

and hydroelectric energy. Energy constraints were a major factor in the 1980s.

Transport and communications

Slightly after the foundation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, there was a lack of essential infrastructure in many areas – paved roads, railways, bridges, etc. Massive improvement in the following years enabled Czechoslovakia to develop its industry. Prague's civil airport inRuzyně

Ruzyně is a district of Prague city, part of Prague 6. It has been a part of Prague since 1960.

Václav Havel Airport is located in this district. Czech Airlines has its head office on the grounds of the airport. Travel Service Airlines and its ...

became one of the most modern terminals in the world when it was finished in 1937. Tomáš Baťa, a Czech entrepreneur and visionary, outlined his ideas in the publication "Budujme stát pro 40 milionů lidí", where he described the future motorway system. Construction of the first motorways in Czechoslovakia begun in 1939, nevertheless, they were stopped after German occupation during World War II.

Society

Education

Education was free at all levels and compulsory from ages 6 to 15. The vast majority of the population was literate. There was a highly developed system of apprenticeship training and vocational schools supplemented generalsecondary schools

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

and institutions of higher education.

Religion

In 1991, 46% of the population wereRoman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, 5.3% were Evangelical Lutheran, 30% were Atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

, and other religions made up 17% of the country, but there were huge differences in religious practices between the two constituent republics

Administrative division, administrative unit,Article 3(1). country subdivision, administrative region, subnational entity, constituent state, as well as many similar terms, are generic names for geographical areas into which a particular, ind ...

; see Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Health, social welfare and housing

After World War II,free health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized ar ...

was available to all citizens. National health planning emphasized preventive medicine; factory and local health care centres supplemented hospitals and other inpatient institutions. There was a substantial improvement in rural health care during the 1960s and 1970s.

Mass media

During the era between the World Wars, Czechoslovak democracy and liberalism facilitated conditions for free publication. The most significant daily newspapers in these times were Lidové noviny, Národní listy, Český deník and Československá Republika. During Communist rule, the mass media in Czechoslovakia were controlled by the Communist Party. Private ownership of any publication or agency of the mass media was generally forbidden, although churches and other organizations published small periodicals and newspapers. Even with this information monopoly in the hands of organizations under KSČ control, all publications werereviewed

Review is an evaluation of a publication, product, service, company, or other object or idea. An article about or a compilation of reviews may itself be called a review.

Review may also refer to:

Evaluation processes

*Book review, a description ...

by the government's Office for Press and Information.

Sports

The Czechoslovakia national football team was a consistent performer on the international scene, with eight appearances in the FIFA World Cup Finals, finishing in second place in 1934 and 1962. The team also won the European Football Championship in 1976, came in third in 1980 and won the Olympic gold in1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning System time epoch begins at 00:00 UTC.

* January 9 – ...

.

Well-known football players such as Pavel Nedvěd, Antonín Panenka, Milan Baroš, Tomáš Rosický, Vladimír Šmicer or Petr Čech were all born in Czechoslovakia.

The International Olympic Committee code for Czechoslovakia is TCH, which is still used in historical listings of results.

The Czechoslovak national ice hockey team won many medals from the world championships and Olympic Games. Peter Šťastný

Peter Šťastný (; born 18 September 1956), also known colloquially as "Peter the Great" and "Stosh", is a Slovak-Canadian former professional ice hockey player who played in the National Hockey League (NHL) from 1980 to 1995. Šťastný is the ...

, Jaromír Jágr, Dominik Hašek, Peter Bondra, Petr Klíma

Petr Klíma (born December 23, 1964) is a Czech former professional ice hockey forward. He played in the National Hockey League for the Detroit Red Wings, Edmonton Oilers, Tampa Bay Lightning, Los Angeles Kings, and the Pittsburgh Penguins. He ...

, Marián Gáborík, Marián Hossa

Marián Hossa (; born 12 January 1979) is a Slovak former professional ice hockey right winger. Hossa was drafted by the Ottawa Senators in the first round, 12th overall, of the 1997 NHL Entry Draft. After spending his first seven NHL seasons ...

, Miroslav Šatan and Pavol Demitra all come from Czechoslovakia.

Emil Zátopek, winner of four Olympic gold medals in athletics, is considered one of the top athletes in Czechoslovak history.

Věra Čáslavská was an Olympic gold medallist in gymnastics, winning seven gold medals and four silver medals. She represented Czechoslovakia in three consecutive Olympics.

Several accomplished professional tennis players including Jaroslav Drobný, Ivan Lendl, Jan Kodeš, Miloslav Mečíř, Hana Mandlíková

Hana Mandlíková (born 19 February 1962) is a former professional tennis player from Czechoslovakia who later obtained Australian citizenship. During her career she won four Grand Slam singles titles - the 1980 Australian Open, 1981 French Op ...

, Martina Hingis, Martina Navratilova

Martina Navratilova ( cs, Martina Navrátilová ; ; born October 18, 1956) is a Czech–American, former professional tennis player. Widely considered among the greatest tennis players of all time, Navratilova won 18 major singles titles, 31 maj ...

, Jana Novotna, Petra Kvitová and Daniela Hantuchová were born in Czechoslovakia.

Culture

*Czech RepublicSlovakia * List of Czechs List of Slovaks * MDŽ (International Women's Day) * Jazz in dissident CzechoslovakiaPostage stamps

* Postage stamps and postal history of CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia stamp reused by Slovak Republic after 18 January 1939 by overprinting country and value

See also

*Effects on the environment in Czechoslovakia from Soviet influence during the Cold War The involvement of the Soviet Union within Czechoslovakian industry, during the Cold War, has contributed toward environmental, and subsequently social impacts, within Czechoslovakia. The concentration on heavy industry, under the Five-year plans of ...

* Former countries in Europe after 1815

* List of former sovereign states

Notes

References

Sources

*Further reading

*Heimann, Mary. ''Czechoslovakia: The State That Failed'' (2009). *Hermann, A. H. ''A History of the Czechs'' (1975). *Kalvoda, Josef. ''The Genesis of Czechoslovakia'' (1986). *Leff, Carol Skalnick. ''National Conflict in Czechoslovakia: The Making and Remaking of a State, 1918–87'' (1988). *Mantey, Victor. ''A History of the Czechoslovak Republic'' (1973). *Myant, Martin. ''The Czechoslovak Economy, 1948–88'' (1989). *Naimark, Norman, and Leonid Gibianskii, eds. ''The Establishment of Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe, 1944–1949'' (1997online edition

*Orzoff, Andrea. ''Battle for the Castle: The Myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe 1914–1948'' (Oxford University Press, 2009)

online review

online *Paul, David. ''Czechoslovakia: Profile of a Socialist Republic at the Crossroads of Europe'' (1990). *Renner, Hans. ''A History of Czechoslovakia since 1945'' (1989). *Seton-Watson, R. W. ''A History of the Czechs and Slovaks'' (1943). *Stone, Norman, and E. Strouhal, eds.''Czechoslovakia: Crossroads and Crises, 1918–88'' (1989). *Wheaton, Bernard; Zdenek Kavav. "The Velvet Revolution: Czechoslovakia, 1988–1991" (1992). *Williams, Kieran, "Civil Resistance in Czechoslovakia: From Soviet Invasion to "Velvet Revolution", 1968–89",

in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), ''Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present'' (Oxford University Press, 2009). *Windsor, Philip, and Adam Roberts, ''Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, Repression and Resistance'' (1969). *Wolchik, Sharon L. ''Czechoslovakia: Politics, Society, and Economics'' (1990).

External links

Online books and articles

*English/Czech

* ttps://www.britannica.com/place/Czechoslovakia Czechoslovakia by Encyclopædia Britannica* Katrin Boeckh

Crumbling of Empires and Emerging States: Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as (Multi)national Countries

in

Maps with Hungarian-language rubrics:

Border changes after the creation of Czechoslovakia

{{Authority control Eastern Bloc Former republics Former Slavic countries Soviet satellite states Geography of Central Europe History of Central Europe 1918 establishments in Czechoslovakia 1939 disestablishments in Czechoslovakia 1945 establishments in Czechoslovakia 1992 disestablishments in Czechoslovakia States and territories established in 1918 States and territories disestablished in 1939 States and territories established in 1945 States and territories disestablished in 1992 1918 establishments in Europe 1992 disestablishments in Europe Former member states of the United Nations