Custer CCW-5 N5855V (rear) MAAM Reading PA 27 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

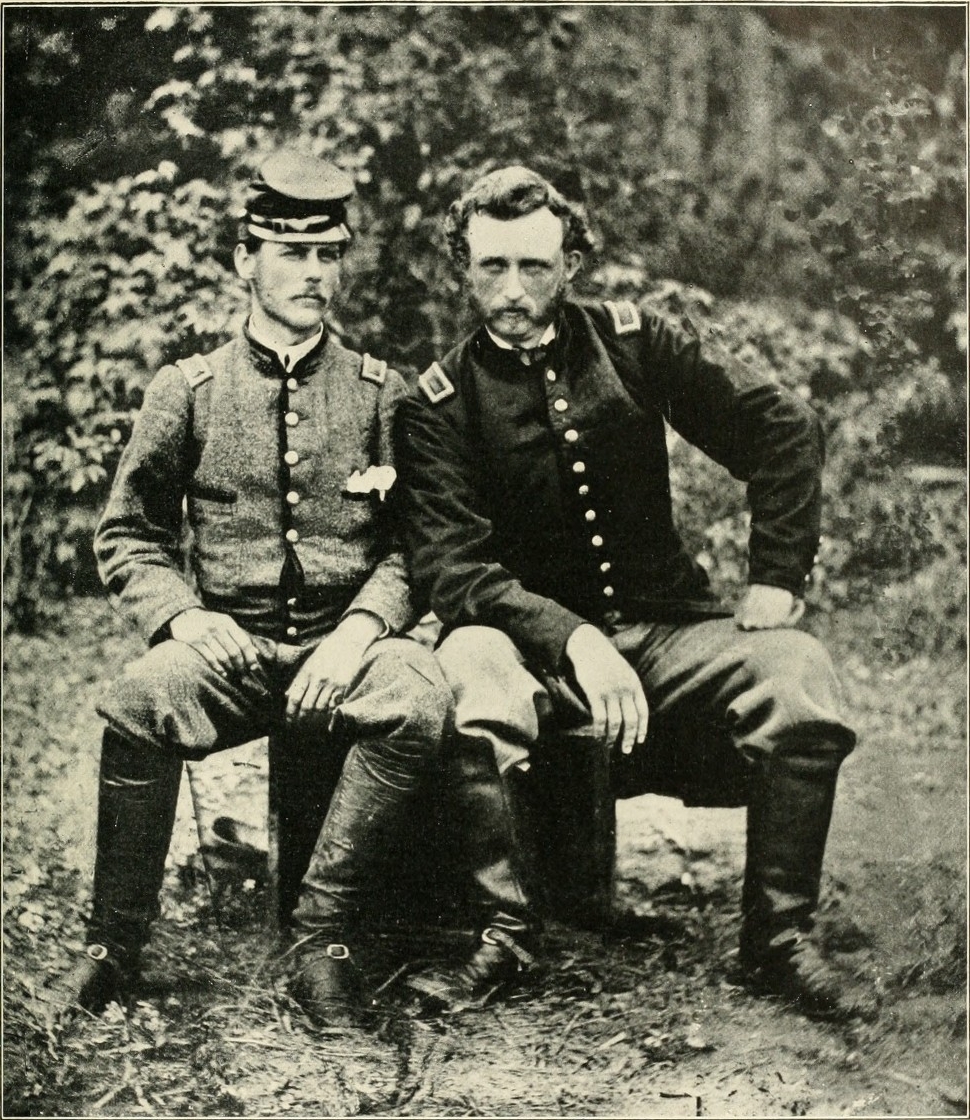

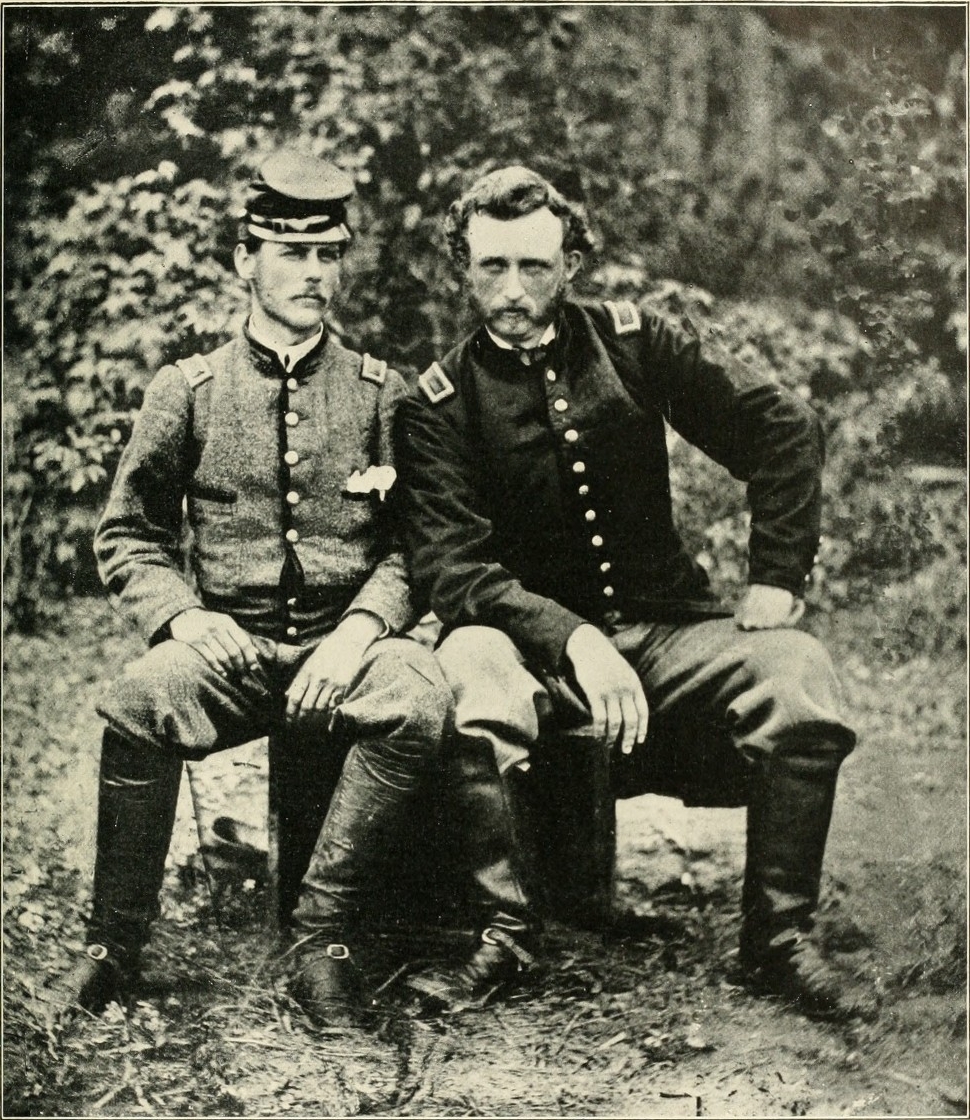

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a

In order to attend school, Custer lived with an older half-sister and her husband in

In order to attend school, Custer lived with an older half-sister and her husband in

Like the other graduates, Custer was commissioned as a

Like the other graduates, Custer was commissioned as a  On June 9, 1863, he became aide to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel

On June 9, 1863, he became aide to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel

Pleasonton was promoted on June 22, 1863, to major general of U.S. Volunteers. On June 29, after consulting with the new commander of the Army of the Potomac,

Pleasonton was promoted on June 22, 1863, to major general of U.S. Volunteers. On June 29, after consulting with the new commander of the Army of the Potomac,

On February 1, 1866, Major General Custer mustered out of the U.S. volunteer service and took an extended leave of absence and awaited orders until September 24. He explored options in New York City,Utley 2001, p. 38. where he considered careers in railroads and mining.Utley 2001, p. 39. Offered a position (and $10,000 in gold) as adjutant general of the army of

On February 1, 1866, Major General Custer mustered out of the U.S. volunteer service and took an extended leave of absence and awaited orders until September 24. He explored options in New York City,Utley 2001, p. 38. where he considered careers in railroads and mining.Utley 2001, p. 39. Offered a position (and $10,000 in gold) as adjutant general of the army of

In 1875, the Grant administration attempted to buy the Black Hills region from the Sioux. When the Sioux refused to sell, they were ordered to report to reservations by the end of January, 1876. Mid-winter conditions made it impossible for them to comply. The administration labeled them "hostiles" and tasked the Army with bringing them in. Custer was to command an expedition planned for the spring, part of a three-pronged campaign. While Custer's expedition marched west from

In 1875, the Grant administration attempted to buy the Black Hills region from the Sioux. When the Sioux refused to sell, they were ordered to report to reservations by the end of January, 1876. Mid-winter conditions made it impossible for them to comply. The administration labeled them "hostiles" and tasked the Army with bringing them in. Custer was to command an expedition planned for the spring, part of a three-pronged campaign. While Custer's expedition marched west from

By the time of Custer's

By the time of Custer's

On February 9, 1864, Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933), whom he had first seen when he was ten years old. He had been socially introduced to her in November 1862, when home in Monroe on leave. She was not initially impressed with him, and her father, Judge Daniel Bacon, disapproved of Custer as a match because he was the son of a blacksmith. It was not until well after Custer had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general that he gained the approval of Judge Bacon. He married Elizabeth Bacon fourteen months after they formally met.

In November 1868, following the

On February 9, 1864, Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933), whom he had first seen when he was ten years old. He had been socially introduced to her in November 1862, when home in Monroe on leave. She was not initially impressed with him, and her father, Judge Daniel Bacon, disapproved of Custer as a match because he was the son of a blacksmith. It was not until well after Custer had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general that he gained the approval of Judge Bacon. He married Elizabeth Bacon fourteen months after they formally met.

In November 1868, following the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

officer and cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

commander in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

.

Custer graduated from West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

in 1861 at the bottom of his class, but as the Civil War was just starting, trained officers were in immediate demand. He worked closely with General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

and the future General Alfred Pleasonton

Alfred Pleasonton (June 7, 1824 – February 17, 1897) was a United States Army officer and major general of volunteers in the Union cavalry during the American Civil War. He commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac during the Gett ...

, both of whom recognized his qualities as a cavalry leader, and he was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers at age 23. Only a few days after his promotion, he fought at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, where he commanded the Michigan Cavalry Brigade The Michigan Brigade, sometimes called the Wolverines, the Michigan Cavalry Brigade or Custer's Brigade, was a brigade of cavalry in the volunteer Union Army during the latter half of the American Civil War. Composed primarily of the 1st Michigan C ...

and despite being outnumbered, defeated J. E. B. Stuart's attack at what is now known as the East Cavalry Field. In 1864, he served in the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

and in Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

's army in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

, defeating Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his U.S. Army commissio ...

at Cedar Creek. His division blocked the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

's final retreat and received the first flag of truce from the Confederates. He was present at Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

After the war, he was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in the Regular Army and was sent west to fight in the Indian Wars. On June 25, 1876, while leading the 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Ireland, Irish air "Garryowen (air), Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated i ...

at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

in Montana Territory against a coalition of Native American tribes, he was killed along with every soldier of the five companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

he led after splitting the regiment into three battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

s. This action became known as "Custer's Last Stand

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nort ...

".

His dramatic end was as controversial as the rest of his career, and reaction to his life and career remains deeply divided. His legend was partly of his own fabrication through his extensive journalism, and perhaps more through the energetic lobbying of his wife Elizabeth Bacon "Libbie" Custer throughout her long widowhood.

Family and ancestry

Custer's paternal ancestors, Paulus and Gertrude Küster, came to the North American English colonies around 1693 from theRhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

in Germany, probably among thousands of Palatines

Palatines (german: Pfälzer), also known as the Palatine Dutch, are the people and princes of Palatinates ( Holy Roman principalities) of the Holy Roman Empire. The Palatine diaspora includes the Pennsylvania Dutch and New York Dutch.

In 1709 ...

whose passage was arranged by the English government to gain settlers in New York and Pennsylvania.

According to family letters, Custer was named after George Armstrong, a minister, in his devout mother's hope that her son might join the clergy.

Birth, siblings, and childhood

Custer was born inNew Rumley, Ohio

New Rumley is an unincorporated community in central Rumley Township, Harrison County, Ohio, United States. It is famous for being the birthplace of George Armstrong Custer.

The Custer Memorial by Erwin Frey is located along State Route 646 ...

, to Emanuel Henry Custer (1806–1892), a farmer and blacksmith, and his second wife, Marie Ward Kirkpatrick (1807–1882), who was of English and Scots-Irish descent. He had two younger brothers, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. His other full siblings were the family's youngest child, Margaret Custer, and Nevin Custer, who suffered from asthma and rheumatism. Custer also had three older half-siblings. Custer and his brothers acquired a life-long love of practical jokes, which they played out among the close family members.

Emanuel Custer was an outspoken Jacksonian Democrat

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andr ...

who taught his children politics and toughness at an early age. In a February 3, 1887, letter to his son's widow Libby, Emanuel related an incident from when George Custer (known as Autie) was about four years old:

"He had to have a tooth drawn, and he was very much afraid of blood. When I took him to the doctor to have the tooth pulled, it was in the night and I told him if it bled well it would get well right away, and he must be a good soldier. When he got to the doctor he took his seat, and the pulling began. The forceps slipped off and he had to make a second trial. He pulled it out, and Autie never even scrunched. Going home, I led him by the arm. He jumped and skipped, and said 'Father you and me can whip all the Whigs in Michigan.' I thought that was saying a good deal but I did not contradict him."

Education

In order to attend school, Custer lived with an older half-sister and her husband in

In order to attend school, Custer lived with an older half-sister and her husband in Monroe, Michigan

Monroe is the largest city and county seat of Monroe County in the U.S. state of Michigan. Monroe had a population of 20,462 in the 2020 census. The city is bordered on the south by Monroe Charter Township, but the two are administered autonomo ...

. Before entering the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

, Custer attended the McNeely Normal School, later known as Hopedale Normal College, in Hopedale, Ohio

Hopedale is a village in Harrison County, Ohio, United States. The population was 920 at the 2020 census.

History

Hopedale was platted in 1849. A post office has been in operation at Hopedale since 1850.

Geography

According to the United State ...

. It was to train teachers for elementary schools. While attending Hopedale, Custer and classmate William Enos Emery were known to have carried coal to help pay for their room and board. After graduating from McNeely Normal School in 1856, Custer taught school in Cadiz, Ohio

Cadiz ( ) is a village in Cadiz Township, Harrison County, Ohio, United States located about 20 miles from Steubenville. The population was 3,353 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Harrison County.

History

Cadiz was founded in 1803 a ...

. His first sweetheart was Mary Jane Holland.

Custer entered West Point as a cadet on July 1, 1857, as a member of the class of 1862. His class numbered seventy-nine cadets embarking on a five-year course of study. With the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

in 1861, the course was shortened to four years, and Custer and his class graduated on June 24, 1861. He was 34th in a class of 34 graduates: 23 classmates had dropped out for academic reasons while 22 classmates had already resigned to join the Confederacy.

Throughout his life, Custer tested boundaries and rules. In his four years at West Point, he amassed a record total of 726 demerits, one of the worst conduct records in the history of the academy. The local minister remembered Custer as "the instigator of devilish plots both during the service and in Sunday school. On the surface he appeared attentive and respectful, but underneath the mind boiled with disruptive ideas." A fellow cadet recalled Custer as declaring there were only two places in a class, the head and the foot, and since he had no desire to be the head, he aspired to be the foot. A roommate noted, "It was alright with George Custer, whether he knew his lesson or not; he simply did not allow it to trouble him." Under ordinary conditions, Custer's low class rank would result in an obscure posting, the first step in a dead-end career, but Custer had the fortune to graduate as the Civil War broke out, and as a result the Union Army had a sudden need for many junior officers.

Civil War

McClellan and Pleasanton

Like the other graduates, Custer was commissioned as a

Like the other graduates, Custer was commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

; he was assigned to the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment and tasked with drilling volunteers in Washington, D.C. On July 21, 1861, he was with his regiment at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

during the Manassas Campaign

The Manassas campaign was a series of military engagements in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.

Background

Military and political situation

The Confederate forces in northern Virginia were organized into two field armies. Br ...

, where Army commander Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

detailed him to carry messages to Major General Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command o ...

. After the battle, he continued participating in the defense of Washington D.C. until October, when he became ill. He was absent from his unit until February 1862. In March, he participated with the 2nd Cavalry in the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia until April 4.

On April 5, Custer served in the 5th Cavalry Regiment

The 5th Cavalry Regiment ("Black Knights") is a historical unit of the United States Army that began its service on August 3, 1861, when an act of Congress enacted "that the two regiments of dragoons, the regiment of mounted riflemen, and the t ...

and participated in the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virgi ...

from April 5 to May 4 and was aide to Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

. McClellan was in command of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

during the Peninsula Campaign. On May 24, 1862, during the pursuit of Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

General Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia seceded ...

up the Peninsula, when General McClellan and his staff were reconnoitering a potential crossing point on the Chickahominy River

The Chickahominy is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 river in the eastern portion of the U.S. state of Virginia. The river, which serves as the eastern bo ...

, they stopped, and Custer overheard General John G. Barnard

John Gross Barnard (May 19, 1815 – May 14, 1882) was a career engineer officer in the United States Army, U.S. Army, serving in the Mexican–American War, as the superintendent of the United States Military Academy and as a general in the Unio ...

mutter, "I wish I knew how deep it is." Custer dashed forward on his horse out to the middle of the river, turned to the astonished officers, and shouted triumphantly, "McClellan, that's how deep it is, General!"

Custer was allowed to lead an attack with four companies of the 4th Michigan Infantry across the Chickahominy River

The Chickahominy is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 river in the eastern portion of the U.S. state of Virginia. The river, which serves as the eastern bo ...

above New Bridge. The attack was successful, resulting in the capture of 50 Confederate soldiers and the seizing of the first Confederate battle flag of the war. McClellan termed it a "very gallant affair" and congratulated Custer personally. In his role as aide-de-camp to McClellan, he began his life-long pursuit of publicity.Tagg, Larry. (1988). ''The Generals Of Gettysburg: Appraisal Of The Leaders Of America's Greatest Battle''. Savas Publishing Company, , p. 184. He was promoted to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on June 5, 1862. On July 17, he was demoted to the rank of first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

. He participated in the Maryland Campaign in September to October, the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

on September 14, the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

on September 17, and the March to Warrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, of which it is the seat of government. The population was 9,611 at the 2010 census, up from 6,670 at the 2000 census. The estimated population in 2019 was 10,027. It is at the junction of U.S. R ...

, in October.

On June 9, 1863, he became aide to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel

On June 9, 1863, he became aide to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Pleasonton

Alfred Pleasonton (June 7, 1824 – February 17, 1897) was a United States Army officer and major general of volunteers in the Union cavalry during the American Civil War. He commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac during the Gett ...

, who was commanding the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac. Recalling his service under Pleasonton, he was quoted as saying that "I do not believe a father could love his son more than General Pleasonton loves me." Pleasonton's first assignment was to locate the army of Robert E. Lee, moving north through the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

in the beginning of what was to become the Gettysburg Campaign.

Brigade command

Pleasonton was promoted on June 22, 1863, to major general of U.S. Volunteers. On June 29, after consulting with the new commander of the Army of the Potomac,

Pleasonton was promoted on June 22, 1863, to major general of U.S. Volunteers. On June 29, after consulting with the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate States Army, Confederate Full General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee at the Battle ...

, Pleasanton began replacing political generals with "commanders who were prepared to fight, to personally lead mounted attacks". He found just the kind of aggressive fighters he wanted in three of his aides: Wesley Merritt

Wesley Merritt (June 16, 1836December 3, 1910) was an American major general who served in the cavalry of the United States Army during the American Civil War, American Indian Wars, and Spanish–American War. Following the latter war, he became ...

, Elon J. Farnsworth

Elon John Farnsworth (July 30, 1837 – July 3, 1863) was a Union Army captain in the American Civil War. He commanded Brigade 1, Division 3 of the Cavalry Corps (Union Army) from June 28, 1863 to July 3, 1863, when he was mortally wounded and die ...

(both of whom had command experience), and Custer. All received immediate promotions, Custer to brigadier general of volunteers, commanding the Michigan Cavalry Brigade The Michigan Brigade, sometimes called the Wolverines, the Michigan Cavalry Brigade or Custer's Brigade, was a brigade of cavalry in the volunteer Union Army during the latter half of the American Civil War. Composed primarily of the 1st Michigan C ...

("Wolverines"), part of the division of Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (January 14, 1836 – December 4, 1881) was an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War, achieving the rank of brevet major general. He was later the United States Minister to Chile and an unsuccessful cand ...

. Despite having no direct command experience, he became one of the youngest generals in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

at age 23. He immediately shaped his brigade to reflect his aggressive character.

Now a general officer, he had great latitude in choosing his uniform. Though often criticized as gaudy, it was more than personal vanity. Historian Tom Carhart observed that "A showy uniform for Custer was one of command presence on the battlefield: he wanted to be readily distinguishable at first glance from all other soldiers. He intended to lead from the front, and to him it was a crucial issue of unit morale that his men be able to look up in the middle of a charge, or at any other time on the battlefield, and instantly see him leading the way into danger."

Hanover and Abbottstown

On June 30, 1863, Custer and the First and Seventh Michigan Cavalry had just passed throughHanover, Pennsylvania

Hanover is a borough in York County, Pennsylvania, southwest of York and north-northwest of Baltimore, Maryland and is north of the Mason-Dixon line. The town is situated in a productive agricultural region. The population was 16,429 at the ...

, while the Fifth and Sixth Michigan Cavalry followed about seven miles behind. Hearing gunfire, he turned and started to the sound of the guns. A courier reported that Farnsworth's Brigade had been attacked by rebel cavalry from side streets in the town. Reassembling his command, he received orders from Kilpatrick to engage the enemy northeast of town near the railway station. Custer deployed his troops and began to advance. After a brief firefight, the rebels withdrew to the northeast. This seemed odd, since it was supposed that Lee and his army were somewhere to the west. Though seemingly of little consequence, this skirmish further delayed Stuart from joining Lee. Further, as Captain James H. Kidd, commander of F troop, Sixth Michigan Cavalry, later wrote: "Under uster'sskillful hand the four regiments were soon welded into a cohesive unit...."

Next morning, July 1, they passed through Abbottstown, Pennsylvania, still searching for Stuart's cavalry. Late in the morning they heard sounds of gunfire from the direction of Gettysburg. At Heidlersburg, Pennsylvania, that night they learned that General John Buford

John Buford, Jr. (March 4, 1826 – December 16, 1863) was a United States Army cavalry officer. He fought for the Union as a brigadier general during the American Civil War. Buford is best known for having played a major role in the first day o ...

's cavalry had found Lee's army at Gettysburg. The next morning, July 2, orders came to hurry north to disrupt General Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell (February 8, 1817 – January 25, 1872) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. L ...

's communications and relieve the pressure on the Union forces. By mid afternoon, as they approached Hunterstown, Pennsylvania

Hunterstown is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in Straban Township, Adams County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 506.

Hunterstown is located along Pennsylvania Route 394, (Shrive ...

, they encountered Stuart's cavalry. Custer rode alone ahead to investigate and found that the rebels were unaware of the arrival of his troops. Returning to his men, he carefully positioned them along both sides of the road where they would be hidden from the rebels. Further along the road, behind a low rise, he positioned the First and Fifth Michigan Cavalry and his artillery, under the command of Lieutenant Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington Jr.

Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington Jr. (January 8, 1838 – November 30, 1917) was an artillery officer and brigadier general in the United States Army and a veteran of both the American Civil War and Spanish–American War.

Early life and ...

To bait his trap, he gathered A Troop, Sixth Michigan Cavalry, called out, "Come on boys, I'll lead you this time!" and galloped directly at the unsuspecting rebels. As he had expected, the rebels, "more than two hundred horsemen, came racing down the country road" after Custer and his men. He lost half of his men in the deadly rebel fire and his horse went down, leaving him on foot. He was rescued by Private Norvell Francis Churchill of the 1st Michigan Cavalry

The 1st Michigan Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was a part of the famed Michigan Brigade, commanded for a time by Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer.

Service

The 1st ...

, who galloped up, shot Custer's nearest assailant, and pulled Custer up behind him. Custer and his remaining men reached safety, while the pursuing rebels were cut down by slashing rifle fire, then canister from six cannons. The rebels broke off their attack, and both sides withdrew.

After spending most of the night in the saddle, Custer's brigade arrived at Two Taverns, Pennsylvania

Two Taverns is an Unincorporated area, unincorporated community on Pennsylvania Route 97 (Adams County), Pennsylvania Route 97 (Baltimore Pike) between Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Gettysburg and Littlestown, Pennsylvania, Littletown in Adams County ...

, roughly five miles southeast of Gettysburg around 3 a.m. July 3. There he was joined by Farnsworth's brigade. By daybreak they received orders to protect Meade's flanks. He was about to experience perhaps his finest hours during the war.

Gettysburg

Lee's battle plan, shared with less than a handful of subordinates, was to defeat Meade through a combined assault by all of his resources. GeneralJames Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

would attack Cemetery Hill

Cemetery Hill is a landform on the Gettysburg Battlefield that was the scene of fighting each day of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863). The northernmost part of the Army of the Potomac defensive " fish-hook" line, the hill is gently ...

from the west, Stuart would attack Culp's Hill

Culp's Hill,. The modern U.S. Geographic Names System refers to "Culps Hill". which is about south of the center of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, played a prominent role in the Battle of Gettysburg. It consists of two rounded peaks, separated by a ...

from the southeast and Ewell

Ewell ( , ) is a suburban area with a village centre in the borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey, approximately south of central London and northeast of Epsom.

In the 2011 Census, the settlement had a population of 34,872, a majority of wh ...

would attack Culp's Hill from the north. Once the Union forces holding Culp's Hill had collapsed, the rebels would "roll up" the remaining Union defenses on Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge is a geographic feature in Gettysburg National Military Park, south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that figured prominently in the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1 to July 3, 1863. It formed a primary defensive position for the ...

. To accomplish this, he sent Stuart with six thousand cavalrymen and mounted infantry on a long flanking maneuver.

By mid-morning on July 3, Custer had arrived at the intersection of Old Dutch Road and Hanover Road, two miles east of Gettysburg. He was later joined by Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg

David McMurtrie Gregg (April 10, 1833 – August 7, 1916) was an American farmer, diplomat, and a Union cavalry general in the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Gregg was born in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. He was the first cousin of futu ...

, who had him deploy his men at the northeast corner. Custer then sent out scouts to investigate nearby wooded areas. Meanwhile, Gregg had positioned Colonel John Baillie McIntosh

John Baillie McIntosh (June 6, 1829 – June 29, 1888), although born in Florida, served as a Union Army Brigadier general (United States), brigadier general in the American Civil War. His brother, James M. McIntosh, served as a Confederate gen ...

's brigade near the intersection and sent the rest of his command to picket duty two miles to the southwest. After additional deployments, 2,400 cavalry under McIntosh and 1,200 under Custer remained, together with Colonel Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington Jr.

Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington Jr. (January 8, 1838 – November 30, 1917) was an artillery officer and brigadier general in the United States Army and a veteran of both the American Civil War and Spanish–American War.

Early life and ...

's and Captain Alanson Merwin Randol

Alanson Merwin Randol (October 23, 1837 – May 7, 1887) was a career United States Army artillery officer and graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point (Class of 1860) who served in the American Civil War. He was promoted mult ...

's artillery, who had a total of ten three-inch guns.

About noon Custer's men heard cannon fire, Stuart's signal to Lee that he was in position and had not been detected. About the same time Gregg received a message warning that a large body of rebel cavalry had moved out on the York Pike and might be trying to get around the Union right. A second message from Pleasonton ordered Gregg to send Custer to cover the Union far left. Since Gregg had already sent most of his force off to other duties, it was clear to both Gregg and Custer that Custer must remain. They had about 2,700 men facing 6,000 Confederates.

Soon afterward fighting broke out between the skirmish lines. Stuart ordered an attack by his mounted infantry under General Albert G. Jenkins

Albert Gallatin Jenkins (November 10, 1830 – May 21, 1864) was a Virginia attorney, planter, slaveholder, politician and soldier from what would become West Virginia during the American Civil War. He served in the United States Congress and ...

, but the Union line held, with men from the First Michigan cavalry, the First New Jersey Cavalry, and the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry. Stuart ordered Jackson's four gun battery into action. Custer ordered Pennington to answer. After a brief exchange in which two of Jackson's guns were destroyed, there was a lull.

About one o'clock, the massive Confederate artillery barrage in support of the upcoming assault on Cemetery Ridge began. Jenkins's men renewed the attack but soon ran out of ammunition and fell back. Resupplied, they again pressed the attack. Outnumbered, the Union cavalry fell back, firing as they went. Custer sent most of his Fifth Michigan cavalry ahead on foot, forcing Jenkins's men to fall back. Jenkins's men were reinforced by about 150 sharpshooters from General Fitzhugh Lee

Fitzhugh Lee (November 19, 1835 – April 28, 1905) was a Confederate cavalry general in the American Civil War, the 40th Governor of Virginia, diplomat, and United States Army general in the Spanish–American War. He was the son of Sydney Smi ...

's brigade, and shortly after Stuart ordered a mounted charge by the Ninth Virginia Cavalry and the Thirteenth Virginia Cavalry. Now it was Custer's men who were running out of ammunition. The Fifth Michigan was forced back and the battle was reduced to vicious, hand-to-hand combat.

Seeing this, Custer mounted a counterattack, riding ahead of the fewer than 400 new troopers of the Seventh Michigan Cavalry, shouting, "Come on, you Wolverines!" As he swept forward, he formed a line of squadrons five ranks deep – five rows of eighty horsemen side by side – chasing the retreating rebels until their charge was stopped by a wood rail fence. The horses and men became jammed into a solid mass and were soon attacked on their left flank by the dismounted Ninth and Thirteenth Virginia Cavalry and on the right flank by the mounted First Virginia Cavalry. Custer extricated his men and raced south to the protection of Pennington's artillery near Hanover Road. The pursuing Confederates were cut down by canister, then driven back by the remounted Fifth Michigan Cavalry. Both forces withdrew to a safe distance to regroup.

It was then about three o'clock. The artillery barrage to the west had suddenly stopped. Union soldiers were surprised to see Stuart's entire force about a half mile away, coming toward them, not in line of battle, but "formed in close column of squadrons... A grander spectacle than their advance has rarely been beheld". Stuart recognized he now had little time to reach and attack the Union rear along Cemetery Ridge. He must make one last effort to break through the Union cavalry.

Stuart passed by McIntosh's cavalry – the First New Jersey, Third Pennsylvania, and Company A of Purnell's Legion, which had been posted about halfway down the field – with relative ease. As Stuart approached, the Union troops were ordered back into the woods without slowing down Stuart's column, "advancing as if in review, with sabers drawn and glistening like silver in the bright sunlight...."

Stuart's last obstacle was Custer and his 400 veteran troopers of the First Michigan Cavalry directly in the Confererate cavalry's path. Outnumbered but undaunted, Custer rode to the head of the regiment, "drew his saber, threw off his hat so they could see his long yellow hair" and shouted... "Come on, you Wolverines!" Custer formed his men in line of battle and charged. "So sudden was the collision that many of the horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them...." As the Confederate advance stopped, their right flank was struck by troopers of the Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Michigan. McIntosh was able to gather some of his men from the First New Jersey and Third Pennsylvania and charged the rebel left flank. "Seeing that the situation was becoming critical, I aptain Millerturned to ieutenant Brooke-Rawleand said: 'I have been ordered to hold this position, but, if you will back me up in case I am court-martialed for disobedience, I will order a charge.' The rebel column disintegrated, and individual troopers fought with saber and pistol.

Within twenty minutes the combatants heard the sound of the Union artillery opening up on Pickett's men. Stuart knew that whatever chance he had of joining the Confederate assault was gone. He withdrew his men to Cress Ridge.

Custer's brigade lost 257 men at Gettysburg, the highest loss of any Union cavalry brigade. "I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry", Custer wrote in his report. "For Gallant And Meritorious Services", he was awarded a Regular Army brevet promotion to major.

Shenandoah Valley and Appomattox Court House

General Custer participated in Sheridan's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. The civilian population was specifically targeted in what is known as ''the Burning''. In 1864, with the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac reorganized under the command of Major GeneralPhilip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

, Custer (now commanding the 3rd Division) led his "Wolverines" to the Shenandoah Valley where by the year's end they defeated the army of Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his U.S. Army commissio ...

in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. During May and June, Sheridan and Custer (Captain, 5th Cavalry, May 8 and Brevet Lieutenant Colonel, May 11) took part in cavalry actions supporting the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

, including the Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Arm ...

(after which Custer ascended to division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

command), and the Battle of Yellow Tavern

The Battle of Yellow Tavern was fought on May 11, 1864, as part of the Overland Campaign of the American Civil War. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan was detached from Grant’s Army of the Potomac to conduct a raid on Richmond, ...

(where J.E.B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials of ...

was mortally wounded). In the largest all-cavalry engagement of the war, the Battle of Trevilian Station

The Battle of Trevilian Station (also called Trevilians) was fought on June 11–12, 1864, in Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Union cavalry under Maj. ...

, in which Sheridan sought to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railr ...

and the Confederates' western resupply route, Custer captured Hampton's divisional train, but was then cut off and suffered heavy losses (including having his division's trains overrun and his personal baggage captured by the enemy) before being relieved. When Lieutenant General Early was ordered to move down the Shenandoah Valley and threaten Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, Custer's division was again dispatched under Sheridan. In the Valley Campaigns of 1864, they pursued the Confederates at the Third Battle of Winchester

The Third Battle of Winchester, also known as the Battle of Opequon or Battle of Opequon Creek, was an American Civil War battle fought near Winchester, Virginia, on September 19, 1864. Union Army Major General Philip Sheridan defeated Confederate ...

and effectively destroyed Early's army during Sheridan's counterattack at Cedar Creek.

Sheridan and Custer, having defeated Early, returned to the main Union Army lines at the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

, where they spent the winter. In April 1865 the Confederate lines finally broke, and Robert E. Lee began his retreat to Appomattox Court House, pursued by the Union cavalry. Custer distinguished himself by his actions at Waynesboro, Dinwiddie Court House, and Five Forks. His division blocked Lee's retreat on its final day and received the first flag of truce from the Confederate force. After a truce was arranged Custer was escorted through the lines to meet Longstreet, who described Custer as having flaxen locks flowing over his shoulders, and Custer said “in the name of General Sheridan I demand the unconditional surrender of this army.” Longstreet replied that he was not in command of the army, but if he was he would not deal with messages from Sheridan. Custer responded it would be a pity to have more blood upon the field, to which Longstreet suggested the truce be respected, and then added “General Lee has gone to meet General Grant, and it is for them to determine the future of the armies.” Custer was present at the surrender at Appomattox Court House and the table upon which the surrender was signed was presented to him as a gift for his wife by Sheridan, who included a note to her praising Custer's gallantry. She treasured the gift of the historic table, which is now in the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. On April 15, 1865, Custer was promoted to major general in the US Volunteers, making him the youngest major general in the Union army at age 25.

On April 25, after the war officially ended, Custer had his men search for, then illegally seize a large, prize racehorse named "Don Juan" near Clarksville, Virginia, worth then an estimated $10,000 (several hundred thousand today), along with his written pedigree. Custer rode Don Juan in the grand review victory parade in Washington, D.C., on May 23, creating a sensation when the scared thoroughbred bolted. The owner, Richard Gaines, wrote to General Grant, who then ordered Custer to return the horse to Gaines, but he did not, instead hiding the horse and winning a race with it the next year, before the horse died suddenly.

Reconstruction duties in Texas

On June 3, 1865, at Sheridan's behest, Major General Custer accepted command of the 2nd Division of Cavalry, Military Division of the Southwest, to march fromAlexandria, Louisiana

Alexandria is the ninth-largest city in the state of Louisiana and is the parish seat of Rapides Parish, Louisiana, United States. It lies on the south bank of the Red River in almost the exact geographic center of the state. It is the prin ...

, to Hempstead, Texas

Hempstead is a city in and the county seat of Waller County, Texas, United States, part of the metropolitan area.

History

On December 29, 1856, Dr. Richard Rodgers Peebles and James W. McDade organized the Hempstead Town Company to sell lots in ...

, as part of the Union occupation forces. Custer arrived at Alexandria on June 27 and began assembling his units, which took more than a month to gather and remount. On July 17, he assumed command of the Cavalry Division of the Military Division of the Gulf (on August 5, officially named the 2nd Division of Cavalry of the Military Division of the Gulf), and accompanied by his wife, he led the division (five regiments of veteran Western Theater cavalrymen) to Texas on an arduous 18-day march in August. On October 27, the division departed to Austin. On October 29, Custer moved the division from Hempstead to Austin

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the seat and largest city of Travis County, with portions extending into Hays and Williamson counties. Incorporated on December 27, 1839, it is the 11th-most-populous city ...

, arriving on November 4. Major General Custer became Chief of Cavalry of the Department of Texas, from November 13 to February 1, 1866, succeeding Major General Wesley Merritt

Wesley Merritt (June 16, 1836December 3, 1910) was an American major general who served in the cavalry of the United States Army during the American Civil War, American Indian Wars, and Spanish–American War. Following the latter war, he became ...

.

During his entire period of command of the division, Custer encountered considerable friction and near mutiny from the volunteer cavalry regiments who had campaigned along the Gulf coast. They desired to be mustered out of Federal service rather than continue campaigning, resented imposition of discipline (particularly from an Eastern Theater general), and considered Custer nothing more than a vain dandy.

Custer's division was mustered out beginning in November 1865, replaced by the regulars of the U.S. 6th Cavalry Regiment

The 6th Cavalry ("Fighting Sixth'") is a regiment of the United States Army that began as a regiment of cavalry in the American Civil War. It currently is organized into aviation squadrons that are assigned to several different combat aviation ...

. Although their occupation of Austin had apparently been pleasant, many veterans harbored deep resentments against Custer, particularly in the 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry, because of his attempts to maintain discipline. Upon its mustering out, several members planned to ambush Custer, but he was warned the night before and the attempt thwarted.

Post-war options

On February 1, 1866, Major General Custer mustered out of the U.S. volunteer service and took an extended leave of absence and awaited orders until September 24. He explored options in New York City,Utley 2001, p. 38. where he considered careers in railroads and mining.Utley 2001, p. 39. Offered a position (and $10,000 in gold) as adjutant general of the army of

On February 1, 1866, Major General Custer mustered out of the U.S. volunteer service and took an extended leave of absence and awaited orders until September 24. He explored options in New York City,Utley 2001, p. 38. where he considered careers in railroads and mining.Utley 2001, p. 39. Offered a position (and $10,000 in gold) as adjutant general of the army of Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Liberalism in Mexico, Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec peoples, Zapo ...

of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, who was then in a struggle with the Mexican Emperor Maximilian I (a satellite ruler of French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

), Custer applied for a one-year leave of absence from the U.S. Army, which was endorsed by Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

*Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

*Grant, Inyo County, C ...

and Secretary Stanton. Sheridan and Mrs. Custer disapproved, however, and when his request for leave was opposed by U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senate, United States Senat ...

, who was against having an American officer commanding foreign troops, Custer refused the alternative of resignation from the Army to take the lucrative post.

Following the death of his father-in-law in May 1866, Custer returned to Monroe, Michigan, where he considered running for Congress. He took part in public discussion over the treatment of the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

in the aftermath of the Civil War, advocating a policy of moderation. He was named head of the Soldiers and Sailors Union, regarded as a response to the hyper-partisan Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (U.S. Navy), and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Decatur, Il ...

(GAR). Also formed in 1866, it was led by Republican activist John Alexander Logan

John Alexander Logan (February 9, 1826 – December 26, 1886) was an American soldier and politician. He served in the Mexican–American War and was a general in the Union Army in the American Civil War. He served the state of Illinois as a stat ...

.

In September 1866 Custer accompanied President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

on a journey by train known as the " Swing Around the Circle" to build up public support for Johnson's policies towards the South. Custer denied a charge by the newspapers that Johnson had promised him a colonel's commission in return for his support, but Custer had written to Johnson some weeks before seeking such a commission. Custer and his wife stayed with the president during most of the trip. At one point Custer confronted a small group of Ohio men who repeatedly jeered Johnson, saying to them: "I was born two miles and a half from here, but I am ashamed of you."Utley 2001, pp. 39–40.

Indian Wars

On July 28, 1866, Custer was appointed lieutenant colonel of the newly created7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Ireland, Irish air "Garryowen (air), Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated i ...

,Utley 2001, p. 40. which was headquartered at Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Gear ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

.Utley 2001, p. 41. He served on frontier duty at Fort Riley from October 18 to March 26, and scouted in Kansas and Colorado until July 28, 1867. He took part in Major General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

's expedition against the Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

. On June 26, Lt. Lyman Kidder's party, made up of ten troopers and one scout, were massacred

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

while en route to Fort Wallace

Fort Wallace ( 1865–1882) was a US Cavalry fort built in Wallace County, Kansas to help defend settlers against Cheyenne and Sioux raids. All that remains today is the cemetery, but for a period of over a decade Fort Wallace was one of the most ...

. Lt. Kidder was to deliver dispatches to Custer from General Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

, but his party was attacked by Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne. Days later, Custer and a search party found the bodies of Kidder's patrol.

Following the Hancock campaign, Custer was arrested and suspended at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perman ...

, until August 12, 1868, for being AWOL

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or Military base, post without permission (a Pass (military), pass, Shore leave, liberty or Leave (U.S. military), leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with u ...

, after having abandoned his post to see his wife. At the request of Major General Sheridan, who wanted him for his planned winter campaign against the Cheyenne, he was allowed to return to duty before his one year term of suspension had expired and joined his regiment to October 7, 1868. He then went on frontier duty, scouting in Kansas and Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

to October 1869.

Under Sheridan's orders, he took part in establishing Camp Supply

Fort Supply (originally Camp Supply) was a United States Army post established on November 18, 1868, in Indian Territory to protect the Southern Plains. It was located just east of present-day Fort Supply, Oklahoma, in what was then the Cherokee Ou ...

in Indian Territory in early November 1868 as a supply base for the winter campaign. On November 27, 1868, he led the 7th Cavalry Regiment in an attack on the Cheyenne encampment of Chief Black Kettle

Black Kettle (Cheyenne: Mo'ohtavetoo'o) (c. 1803November 27, 1868) was a prominent leader of the Southern Cheyenne during the American Indian Wars. Born to the ''Northern Só'taeo'o / Só'taétaneo'o'' band of the Northern Cheyenne in the Black ...

– the Battle of Washita River

The Battle of Washita River (also called Battle of the Washita or the Washita Massacre) occurred on November 27, 1868, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked Black Kettle's Southern Cheyenne camp on the Washita Rive ...

. He reported killing 103 warriors and some women and children; 53 women and children were taken as prisoners. Estimates by the Cheyenne of their casualties were substantially lower (11 warriors plus 19 women and children). Custer had his men shoot most of the 875 Indian ponies they had captured. The Battle of Washita River was regarded as the first substantial U.S. victory in the Southern Plains War, and it helped force a large portion of the Southern Cheyenne

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

History

The Cheyennes and Arapahos are two distinct tribes with distinct histories. The Cheyenne (Tsi ...

onto a U.S.-assigned reservation.

In 1873, he was sent to the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

to protect a railroad survey party against the Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

. On August 4, 1873, near the Tongue River, the 7th Cavalry Regiment clashed for the first time with the Lakota. One man on each side was killed. In 1874 Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

and announced the discovery of gold on French Creek near present-day Custer, South Dakota

Custer is a city in Custer County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 1,919 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Custer County.

History

Custer is the oldest town established by European Americans in the Black Hills. Gold ...

. Custer's announcement triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush

The Black Hills Gold Rush took place in Dakota Territory in the United States. It began in 1874 following the Custer Expedition and reached a peak in 1876–77.

Rumors and poorly documented reports of gold in the Black Hills go back to the early ...

. Among the towns that immediately sprung up was Deadwood, South Dakota

Deadwood (Lakota: ''Owáyasuta''; "To approve or confirm things") is a city that serves as county seat of Lawrence County, South Dakota, United States. It was named by early settlers after the dead trees found in its gulch. The city had it ...

, notorious for its lawlessness.

Grant, Belknap and politics

In 1875, the Grant administration attempted to buy the Black Hills region from the Sioux. When the Sioux refused to sell, they were ordered to report to reservations by the end of January, 1876. Mid-winter conditions made it impossible for them to comply. The administration labeled them "hostiles" and tasked the Army with bringing them in. Custer was to command an expedition planned for the spring, part of a three-pronged campaign. While Custer's expedition marched west from

In 1875, the Grant administration attempted to buy the Black Hills region from the Sioux. When the Sioux refused to sell, they were ordered to report to reservations by the end of January, 1876. Mid-winter conditions made it impossible for them to comply. The administration labeled them "hostiles" and tasked the Army with bringing them in. Custer was to command an expedition planned for the spring, part of a three-pronged campaign. While Custer's expedition marched west from Fort Abraham Lincoln

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is a North Dakota state park located south of Mandan, North Dakota, United States. The park is home to the replica Mandan On-A-Slant Indian Village and reconstructed military buildings including the Custer House.

...

, near present-day Mandan, North Dakota

Mandan is a city on the eastern border of Morton County and the eighth-largest city in North Dakota. Founded in 1879 on the west side of the upper Missouri River, it was designated in 1881 as the county seat of Morton County. The population was ...

, troops under Colonel John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the fourt ...

were to march east from Fort Ellis

Fort Ellis was a United States Army fort established August 27, 1867, east of present-day Bozeman, Montana. Troops from the fort participated in many major campaigns of the Indian Wars. The fort was closed on August 2, 1886.

History

The fort w ...

, near present-day Bozeman, Montana

Bozeman is a city and the county seat of Gallatin County, Montana, United States. Located in southwest Montana, the 2020 census put Bozeman's population at 53,293, making it the fourth-largest city in Montana. It is the principal city of th ...

, while a force under General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

was to march north from Fort Fetterman

Fort Fetterman was constructed in 1867 by the United States Army on the Great Plains frontier in Dakota Territory, approximately 11 miles northwest of present-day Douglas, Wyoming. Located high on the bluffs south of the North Platte River, it ...

, near present-day Douglas, Wyoming

Douglas is a city in Converse County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 6,120 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Converse County and the home of the Wyoming State Fair.

History

Douglas was platted in 1886 when the Wyoming C ...

.

Custer's 7th Cavalry was originally scheduled to leave Fort Abraham Lincoln

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park is a North Dakota state park located south of Mandan, North Dakota, United States. The park is home to the replica Mandan On-A-Slant Indian Village and reconstructed military buildings including the Custer House.

...

on April 6, 1876, but on March 15 he was summoned to Washington to testify at congressional hearings. Rep. Hiester Clymer

Hiester Clymer (November 3, 1827 – June 12, 1884) was an American political leader from the state of Pennsylvania. Clymer was a member of the Hiester family political dynasty and the Democratic Party. He was the nephew of William Muhlenberg Hi ...

's Committee was investigating alleged corruption involving Secretary of War William W. Belknap

William Worth Belknap (September 22, 1829 – October 12, 1890) was a lawyer, soldier in the Union Army, government administrator in Iowa, and the 30th United States Secretary of War, serving under President Ulysses S. Grant. Belknap was impeach ...

(who had resigned March 2), President Grant's brother Orville and traders granted monopolies at frontier Army posts. It was alleged that Belknap had been selling these lucrative trading post positions where soldiers were required to make their purchases. Custer himself had experienced first hand the high prices being charged at Fort Lincoln.

Concerned that he might miss the coming campaign, Custer did not want to go to Washington. He asked to answer questions in writing, but Clymer insisted. Recognizing that his testimony would be explosive, Custer tried "to follow a moderate and prudent course, avoiding prominence." Despite this, he provided a quantity of unsubstantiated accusations against Belknap. His testimony, given on March 29 and April 4, was a sensation, being loudly praised by the Democratic press and sharply criticized by Republicans. Custer wrote articles published anonymously in ''The New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' that exposed trader post kickback rings and implied that Belknap was behind them. During his testimony, Custer attacked President Grant's brother Orville on unproven grounds of extorting money in exchange for exerting undue influence. Historian Stephen E. Ambrose speculated that around this time Custer was presented with the idea of becoming the Democratic candidate in the upcoming 1876 United States presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentious ...

, adding further motivation for Custer to rejoin his regiment and win further accolades in the Sioux Wars.

After Custer testified, Belknap was impeached and the case sent to the Senate for trial. Custer asked the impeachment managers to release him from further testimony. With the help of a request from his superior, Brigadier General Alfred Terry

Alfred Howe Terry (November 10, 1827 – December 16, 1890) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to vic ...

, Commander of the Department of Dakota

A subdivision of the Division of the Missouri, the Department of Dakota was established by the United States Army on August 11, 1866, to encompass all military activities and forts within Minnesota, Dakota Territory and Montana Territory. The Depar ...

, he was excused. However, President Grant intervened, ordering that another officer fulfill Custer's military duty.

General Terry protested, arguing that he had no available officers of rank qualified to replace Custer. Both Sheridan and Sherman wanted Custer in command but had to support Grant. General Sherman, hoping to resolve the issue, advised Custer to meet personally with Grant before leaving Washington. Three times Custer requested meetings with the president, but each request was refused.

Finally, Custer gave up and took a train to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

on May 2, planning to rejoin his regiment. A furious Grant ordered Sheridan to arrest Custer for leaving Washington without permission. On May 3, a member of Sheridan's staff arrested Custer as he arrived in Chicago. The arrest sparked public outrage. ''The New York Herald'' called Grant the "modern Caesar" and asked, "Are officers... to be dragged from railroad trains and ignominiously ordered to stand aside until the whims of the Chief magistrate ... are satisfied?"

Grant relented but insisted that Terry—not Custer—personally command the expedition. Terry met Custer in St. Paul, Minnesota, on May 6. He later recalled that Custer "with tears in his eyes, begged for my aid. How could I resist it?" Custer and Terry both wrote telegrams to Grant asking that Custer lead his regiment, with Terry in command. Sheridan endorsed the effort.

Grant was already under pressure for his treatment of Custer. His administration worried that if the "Sioux campaign" failed without Custer, then Grant would be blamed for ignoring the recommendations of senior Army officers. On May 8, Custer was told that he would lead the expedition, but only under Terry's direct supervision.

Elated, Custer told General Terry's chief engineer, Captain Ludlow, that he would "cut loose" from Terry and operate independently.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

By the time of Custer's

By the time of Custer's Black Hills expedition

The Black Hills Expedition was a United States Army expedition in 1874 led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer that set out on July 2, 1874 from modern day Bismarck, North Dakota, which was then Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territor ...

in 1874, the level of conflict and tension between the U.S. and many of the Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of N ...

tribes (including the Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

) had become exceedingly high. European-Americans continually broke treaty agreements and advanced further westward, resulting in violence and acts of depredation by both sides. To take possession of the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

(and thus the gold deposits), and to stop Indian attacks, the U.S. decided to corral all remaining free Plains Indians. The Grant government set a deadline of January 31, 1876, for all Lakota and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

wintering in the "unceded territory" to report to their designated agencies (reservations) or be considered "hostile".

At that time the 7th Cavalry's regimental commander, Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis, was on detached duty as the Superintendent of Mounted Recruiting Service and in command of the Cavalry Depot in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, which left Lieutenant Colonel Custer in command of the regiment. Custer and the 7th Cavalry departed from Fort Abraham Lincoln