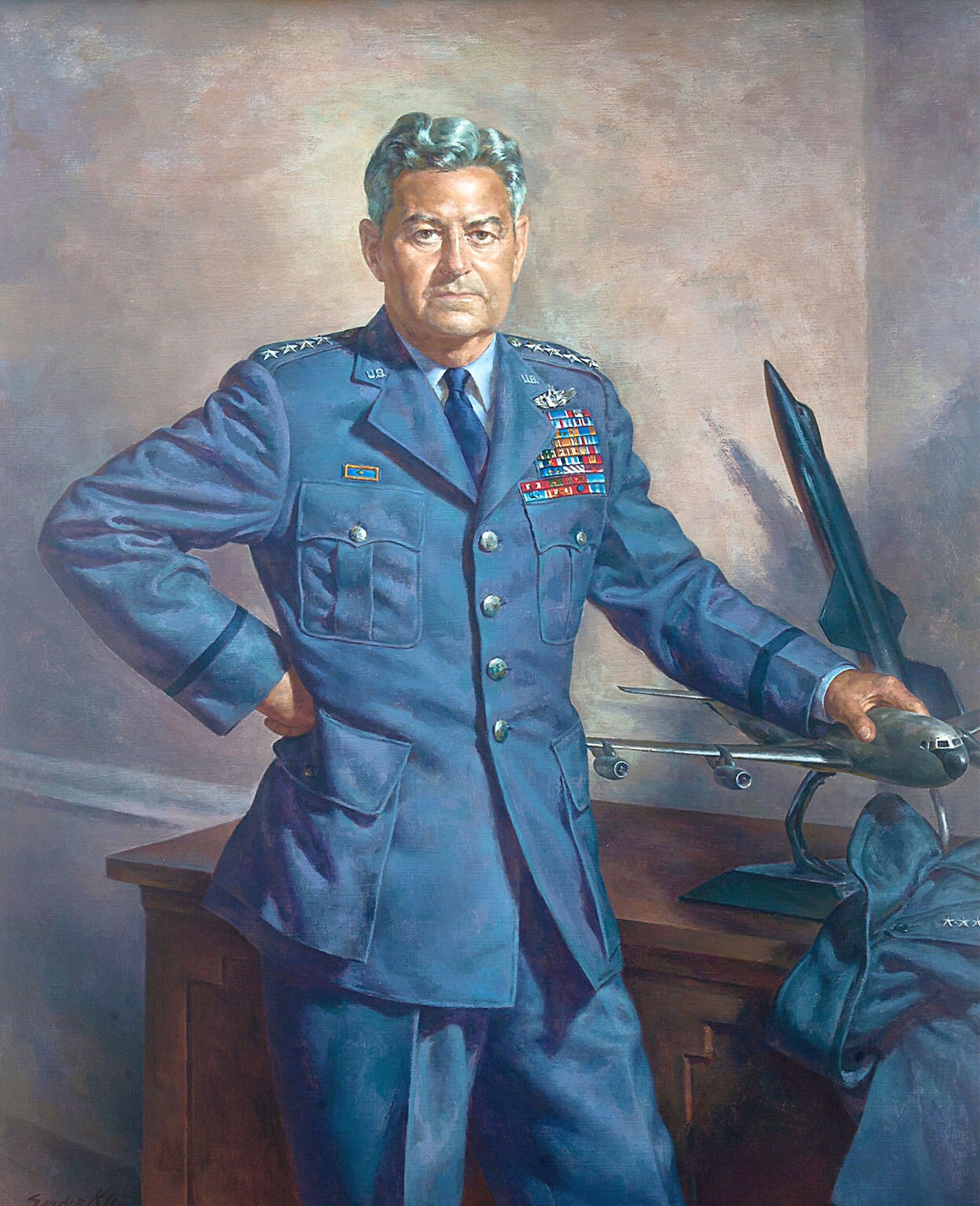

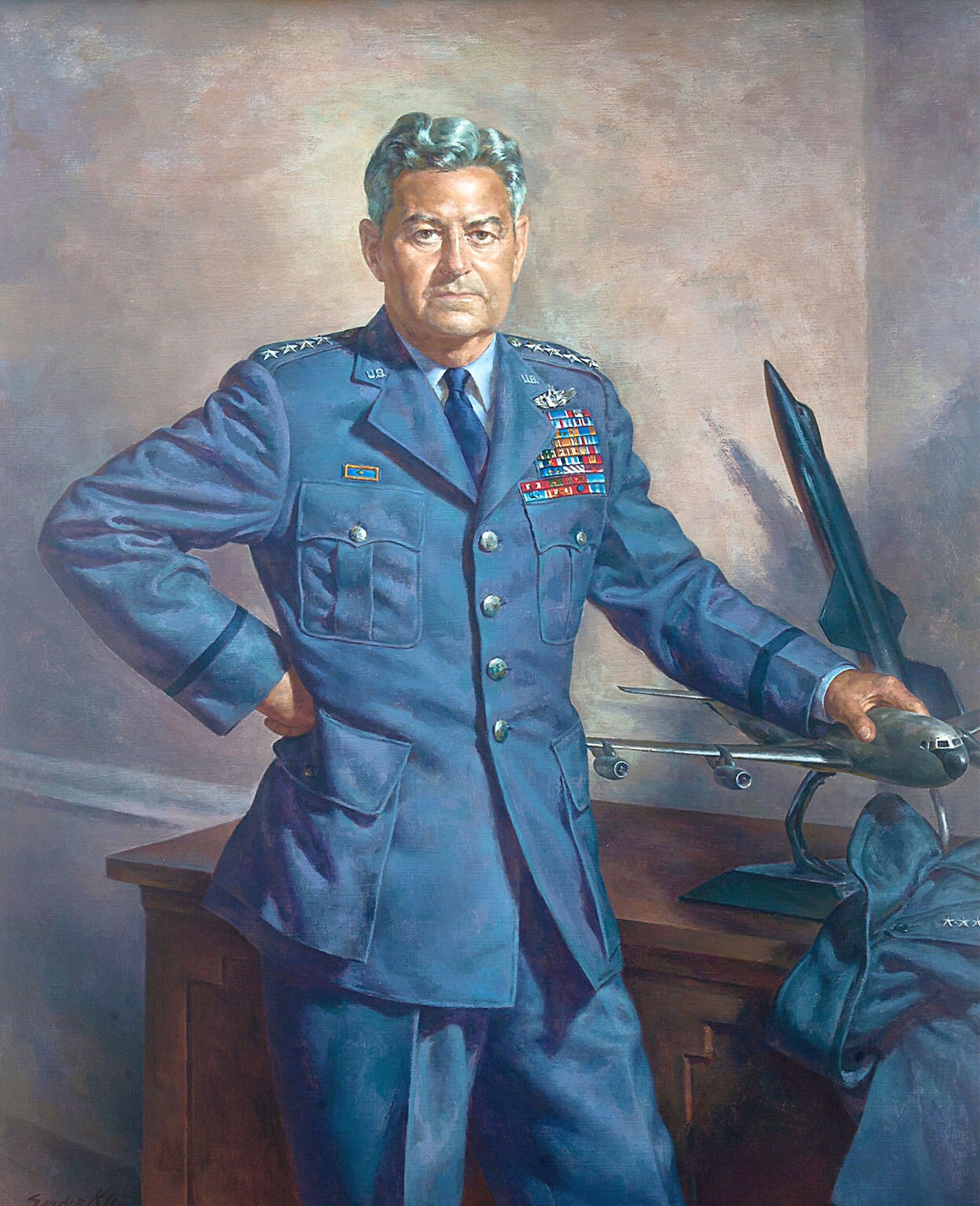

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was an American

Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

who implemented a controversial

strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

campaign in the

Pacific theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. He later served as

Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, from 1961 to 1965.

LeMay joined the

U.S. Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

, the precursor to the U.S. Air Force, in 1929 while studying

civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewage ...

at

Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best publ ...

. He had risen to the rank of

major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

by the time of Japan's

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

in December 1941 and the United States's subsequent entry into World War II. He commanded the

305th Operations Group

The 305th Operations Group is a United States Air Force unit assigned to the 305th Air Mobility Wing. It is stationed at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, New Jersey.

During World War II, the group's predecessor unit, the 305th Bombardment Grou ...

from October 1942 until September 1943, and the

3rd Air Division

The 3rd Air Division (3d AD) is an inactive United States Air Force organization. Its last assignment was with Strategic Air Command, assigned to Fifteenth Air Force, being stationed at Hickam AFB, Hawaii. It was inactivated on 1 April 1992.

...

in the

European theatre of World War II

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main Theater (warfare), theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Nazi Germany, Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 Sept ...

until August 1944, when he was transferred to the

China Burma India Theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was officia ...

. He was then placed in command of strategic bombing operations against Japan, planning and executing a

massive fire bombing campaign against Japanese cities and

Operation Starvation

Operation Starvation was a naval mining operation conducted in World War II by the United States Army Air Forces to disrupt Japanese shipping.

Operation

The mission was initiated at the insistence of Admiral Chester Nimitz who wanted his naval ...

, a crippling minelaying campaign in Japan's internal waterways.

After the war, he was assigned to command

USAF Europe and coordinated the

Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road ...

. He served as commander of the

Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

(SAC) from 1948 to 1957, where he presided over the transition to an all-

jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, je ...

force that had a strong emphasis on the delivery of

nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

in the event of war. As Chief of Staff of the Air Force, he called for the bombing of Cuban missile sites during the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

and sought a sustained bombing campaign against

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

during the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

After retiring from the Air Force in 1965, LeMay agreed to serve as Governor

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and ...

's running mate on the

American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in ...

ticket in the

1968 United States presidential election

The 1968 United States presidential election was the 46th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 5, 1968. The Republican nominee, former vice president Richard Nixon, defeated the Democratic nominee, incumbent vice presiden ...

. The ticket won 13.5% of the popular vote, a strong tally for a

third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a Veh ...

campaign, but the

Wallace campaign came to see LeMay as a liability. After the election, LeMay retired to his home in

Newport Beach, California

Newport Beach is a coastal city in South Orange County, California. Newport Beach is known for swimming and sandy beaches. Newport Harbor once supported maritime industries however today, it is used mostly for recreation. Balboa Island, Newport ...

, and died in 1990 at age 83.

Early life

LeMay was born in

Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

, on November 15, 1906. LeMay was of

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and distant

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

heritage. His father, Erving Edwin LeMay, was at times an ironworker and general handyman, but he never held a job longer than a few months. His mother, Arizona Dove (

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Carpenter) LeMay, did her best to hold her family together. With very limited income, his family moved around the country as his father looked for work, going as far as

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

and

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. Eventually they returned to his native city of Columbus. LeMay attended Columbus public schools, graduating from Columbus South High School, and studied

civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewage ...

at The

Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best publ ...

. Working his way through college, he graduated with a

bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

in

civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewage ...

. While at Ohio State he was a member of the

National Society of Pershing Rifles and the Professional Engineering Fraternity

Theta Tau

Theta Tau () is a professional engineering fraternity. The fraternity has programs to promote the social, academic, and professional development of its members. Today, Theta Tau is the oldest and largest professional engineering fraternity and h ...

.

Career

LeMay was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Air Corps Reserve in October 1929. He received a regular commission in the

United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical r ...

in January 1930. While finishing at Ohio State, he took flight training at

Norton Field

Norton Field was an aviation landing field, located in Columbus, Ohio, that operated from 1923 until the early 1950s. It was the first airport established in Central Ohio, and was named for World War I pilot and star Ohio State University athlete ...

in Columbus, in 1931–32. On June 9, 1934, he married Helen Maitland.

LeMay became a

pursuit pilot with his first duty station at

Selfridge Field

Selfridge Air National Guard Base or Selfridge ANGB is an Air National Guard installation located in Harrison Township, Michigan, near Mount Clemens. Selfridge Field was one of thirty-two Air Service training camps established after the Unit ...

with the

27th Pursuit Squadron. After having served in various assignments in fighter operations, LeMay transferred to bomber aircraft in 1937.

While stationed in

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, he became one of the first members of the Air Corps to receive specialized training in aerial navigation. In August 1937, as navigator under pilot and commander

Caleb V. Haynes

Caleb Vance Haynes (March 15, 1895 – April 5, 1966) was a United States Air Force (USAF) major general. The grandson of Chang Bunker, a famous Siamese Twin, he served in the Air Force as an organizer, able to create air units from scratch. ...

on a

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

, he helped locate the battleship ''

Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

'' despite being given the wrong coordinates by Navy personnel, in exercises held in misty conditions off California, after which the group of B-17s bombed it with water bombs. In March 1938, LeMay as a member of the

2nd Bombardment Group

The 2d Operations Group (2 OG) is the flying component of the United States Air Force 2d Bomb Wing, assigned to the Air Force Global Strike Command Eighth Air Force. The group is stationed at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana.

2 OG is one of t ...

participated in a good will flight to Buenos Aires. For this flight, the 2nd Bombardment Group was awarded the

Mackay Trophy

The Mackay Trophy is awarded yearly by the United States Air Force for the "most meritorious flight of the year" by an Air Force person, persons, or organization. The trophy is housed in the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museu ...

in 1939.

[ For Haynes again, in May 1938 he navigated three B-17s over the Atlantic Ocean to intercept the Italian liner ''SS Rex'' to illustrate the ability of land-based airpower to defend the American coasts. In 1940 he was navigator for Haynes on the prototype ]Boeing XB-15

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product ...

heavy bomber, flying a survey from Panama over the Galapagos islands. By the end of 1940, he was stationed at Westover Air Reserve Base

Westover Air Reserve Base is an Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) installation located in the Massachusetts communities of Chicopee and Ludlow, near the city of Springfield, Massachusetts. Established at the outset of World War II, today Westov ...

, as the operations officer of the 34th Bombardment Group.[Coffey, ''Iron Eagle''] War brought rapid promotion and increased responsibility.

When his crews were not flying missions, they were subjected to relentless training, as LeMay believed that training was the key to saving their lives. "You fight as you train" was one of his cardinal rules. It expressed his belief that, in the chaos, stress, and confusion of combat (aerial or otherwise), troops or airmen would perform successfully only if their individual acts were second nature, performed nearly instinctively due to repetitive training. Throughout his career, LeMay was widely and fondly known among his troops as "Old Iron Pants", and the "Big Cigar".

World War II

When the U.S. entered

When the U.S. entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in December 1941 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

, LeMay was a major in the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(he had been a first lieutenant as recently as 1940), and the commander of a newly created B-17 Flying Fortress unit, the 305th Bomb Group. He took this unit to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in October 1942 as part of the Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Force ...

, and led it in combat until May 1943, notably helping to develop the combat box

The combat box was a tactical formation used by heavy (strategic) bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II. The combat box was also referred to as a "staggered formation". Its defensive purpose was in massing the firepower of the bo ...

formation.[Tillman, ''LeMay''] In September 1943, he became the first commander of the newly formed 3rd Air Division

The 3rd Air Division (3d AD) is an inactive United States Air Force organization. Its last assignment was with Strategic Air Command, assigned to Fifteenth Air Force, being stationed at Hickam AFB, Hawaii. It was inactivated on 1 April 1992.

...

. He personally led several dangerous missions, including the Regensburg section of the Schweinfurt–Regensburg mission

The Schweinfurt–Regensburg mission was a strategic bombing mission during World War II carried out by Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces on August 17, 1943. The mission was an ambitious plan to cripple the ...

of August 17, 1943. In that mission, he led 146 B-17s to Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, beyond the range of escorting fighters, and, after bombing, continued on to bases in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, losing 24 bombers

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an aircraf ...

in the process.European theater

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

of the P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in April 1940 by a team headed by James ...

in January 1944, the Eighth Air Force gained an escort fighter with range to match the bombers.

In a discussion of a report into high abort rates in bomber missions during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, which Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

suspected was because of pilot cowardice, McNamara described LeMay's character:

In August 1944, LeMay transferred to the

In August 1944, LeMay transferred to the China-Burma-India theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was officia ...

and directed first the XX Bomber Command

The XX Bomber Command was a United States Army Air Forces bomber formation. Its last assignment was with Twentieth Air Force, based on Okinawa. It was inactivated on 16 July 1945.

History

The idea of basing Boeing B-29 Superfortresses in C ...

in China and then the XXI Bomber Command

The XXI Bomber Command was a unit of the Twentieth Air Force in the Mariana Islands for strategic bombing during World War II.

The command was established at Smoky Hill Army Air Field, Kansas on 1 March 1944. After a period of organization an ...

in the Pacific. LeMay was later placed in charge of all strategic air operations against the Japanese home islands.Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

bombers flying from China were dropping their bombs near their targets only 5% of the time. Operational losses of aircraft and crews were unacceptably high owing to Japanese daylight air defenses and continuing mechanical problems with the B-29. In January 1945, LeMay was transferred from China to relieve Brigadier General Haywood S. Hansell

Haywood Shepherd Hansell Jr. (September 28, 1903 – November 14, 1988) was a general officer in the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) during World War II, and later the United States Air Force. He became an advocate of the doctrine o ...

as commander of the XXI Bomber Command in the Marianas

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

. He became convinced that high-altitude

He became convinced that high-altitude precision bombing

Precision bombing refers to the attempted aerial bombing of a target with some degree of accuracy, with the aim of maximising target damage or limiting collateral damage. An example would be destroying a single building in a built up area causing ...

would be ineffective, given the usually cloudy weather over Japan. Furthermore, bombs dropped from the B-29s at high altitude (above ) were often blown off of their trajectories by a consistently powerful jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering thermal wind, air currents in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are west ...

over the Japanese home islands, which dramatically reduced the effectiveness of the high-altitude raids. Because Japanese air defenses made daytime bombing below jet stream-affected altitudes too perilous, LeMay finally switched to low-altitude nighttime incendiary attacks on Japanese targets, a tactic senior commanders had been advocating for some time.area bombing

In military aviation, area bombardment (or area bombing) is a type of aerial bombardment in which bombs are dropped over the general area of a target. The term "area bombing" came into prominence during World War II.

Area bombing is a form of str ...

.

LeMay commanded subsequent B-29 Superfortress combat operations against Japan, including massive incendiary attacks on 67 Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

ese cities and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

. This included the firebombing of Tokyo

The was a series of firebombing air raids by the United States Army Air Force during the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Operation Meetinghouse, which was conducted on the night of 9–10 March 1945, is the single most destructive bombing ...

known in official documents as the "Operation Meetinghouse" air raid on the night of March 9–10, 1945 which proved to be the single most destructive bombing raid of the war.[United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Summary Report (Pacific War). Washington DC, July 1, 1946.] For this first attack, LeMay ordered the defensive guns removed from 325 B-29s, loaded each plane with Model M-47 incendiary clusters, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ta ...

bombs, white phosphorus

Elemental phosphorus can exist in several allotropes, the most common of which are white and red solids. Solid violet and black allotropes are also known. Gaseous phosphorus exists as diphosphorus and atomic phosphorus.

White phosphorus

White ...

bombs, and napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated al ...

, and ordered the bombers to fly in streams at over Tokyo.Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

in August 1945, may have killed more than 500,000 Japanese civilians and left five million homeless. Official estimates from the United States Strategic Bombing Survey

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) was a written report created by a board of experts assembled to produce an impartial assessment of the effects of the Anglo-American strategic bombing of Nazi Germany during the European theatre o ...

put the figures at 220,000 people killed. LeMay was aware of the implication of his orders. ''

LeMay was aware of the implication of his orders. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' reported at the time, "Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, commander of the B-29s of the entire Marianas area, declared that if the war is shortened by a single day, the attack will have served its purpose".Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

in the 2003 documentary ''The Fog of War

''The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara'' is a 2003 American documentary film about the life and times of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, illustrating his observations of the nature of modern warfa ...

'', although after the war the Allies did not prosecute any German or Japanese military personnel for bombing civilian targets.

Presidents

Presidents Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

and Truman supported LeMay's strategy, referring to an estimate of one million Allied casualties if Japan had to be invaded. Japan had intentionally decentralized

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those regarding planning and decision making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group.

Conce ...

90% of its war-related production into small subcontractor

A subcontractor is an individual or (in many cases) a business that signs a contract to perform part or all of the obligations of another's contract.

Put simply the role of a subcontractor is to execute the job they are hired by the contractor f ...

workshops in civilian districts, making remaining Japanese war industry largely immune to conventional precision bombing with high explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

. As the firebombing campaign took effect, Japanese war planners were forced to expend significant resources to relocate vital war industries to remote caves and mountain bunkers, reducing production of war material. As a lieutenant colonel who served under LeMay, Robert McNamara was in charge of evaluating the effectiveness of American bombing missions. Later, McNamara, as United States Secretary of Defense

The United States secretary of defense (SecDef) is the head of the United States Department of Defense, the executive department of the U.S. Armed Forces, and is a high ranking member of the federal cabinet. DoDD 5100.1: Enclosure 2: a The s ...

under Presidents John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, often clashed with LeMay.

LeMay also oversaw Operation Starvation

Operation Starvation was a naval mining operation conducted in World War II by the United States Army Air Forces to disrupt Japanese shipping.

Operation

The mission was initiated at the insistence of Admiral Chester Nimitz who wanted his naval ...

, an aerial mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

operation against Japanese waterways and ports that disrupted Japanese shipping and logistics

Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics manages the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of ...

. Although his superiors were unsupportive of this naval objective, LeMay gave it a high priority by assigning the entire 313th Bombardment Wing (four groups, about 160 airplanes) to the task. Aerial mining supplemented a tight Allied submarine blockade of the home islands, drastically reducing Japan's ability to supply its overseas forces to the point that postwar analysis concluded that it could have defeated Japan on its own had it begun earlier.

Japan–Washington flight

LeMay piloted one of three specially modified B-29s flying from Japan to the U.S. in September 1945, in the process breaking several aviation records, including the greatest USAAF takeoff weight, the longest USAAF non-stop flight, and the first ever non-stop Japan–Chicago flight. One of the pilots was of higher rank: Lieutenant General Barney M. Giles

Barney McKinney Giles (September 13, 1892 – May 6, 1984) was an American military officer who helped develop strategic bombing theory and practice. Giles stepped outside established bomber doctrine during World War II to develop long-range cap ...

. The other two aircraft used up more fuel than LeMay's in fighting headwinds, and they could not fly to Washington, D.C., the original goal.

Cold War

Berlin Airlift

After World War II, LeMay was briefly transferred to

After World War II, LeMay was briefly transferred to The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

as deputy chief of Air Staff for Research & Development. In 1947, he returned to Europe as commander of USAF Europe, heading operations for the Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road ...

in 1948 in the face of a blockade by the Soviet Union and its satellite states that threatened to starve the civilian population of the Western occupation zones of Berlin. Under LeMay's direction, Douglas C-54 Skymaster

The Douglas C-54 Skymaster is a four-engined transport aircraft used by the United States Army Air Forces in World War II and the Korean War. Like the Douglas C-47 Skytrain derived from the DC-3, the C-54 Skymaster was derived from a civilian a ...

s that could each carry 10 tons of cargo began supplying the city on July 1. By the fall, the airlift was bringing in an average of 5,000 tons of supplies a day with 500 daily flights. The airlift continued for 11 months, with 213,000 flights operated by six countries bringing in 1.7 million tons of food and fuel to Berlin. Faced with the failure of its blockade, the Soviet Union relented and reopened land corridors to the West. Though LeMay is sometimes publicly credited with the success of the Berlin Airlift, it was, in fact, instigated by General Lucius D. Clay

General Lucius Dubignon Clay (April 23, 1898 – April 16, 1978) was a senior officer of the United States Army who was known for his administration of occupied Germany after World War II. He served as the deputy to General of the Army Dwight D ...

when General Clay called LeMay about the problem. LeMay initially started flying supplies into Berlin, but then decided that it was a job for a logistics expert and he found that person in Lt. General William H. Tunner

William Henry Tunner (July 14, 1906 – April 6, 1983) was a general officer in the United States Air Force and its predecessor, the United States Army Air Forces. Tunner was known for his expertise in the command of large-scale military airlif ...

, who took over the operational end of the Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road ...

.

Strategic Air Command

In 1948, he returned to the U.S. to head the

In 1948, he returned to the U.S. to head the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

(SAC) at Offutt Air Force Base

Offutt Air Force Base is a U.S. Air Force base south of Omaha, adjacent to Bellevue in Sarpy County, Nebraska. It is the headquarters of the U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the 557th Weather Wing, and the 55th Wing (55 WG) of the Air ...

, replacing Gen George Kenney

George Churchill Kenney (August 6, 1889 – August 9, 1977) was a United States Army general during World War II. He is best known as the commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), a position he held between Augu ...

. When LeMay took over command of SAC, it consisted of little more than a few understaffed B-29 bombardment groups left over from World War II. Less than half of the available aircraft were operational, and the crews were undertrained. Base and aircraft security standards were minimal. Upon inspecting a SAC hangar full of US nuclear strategic bombers, LeMay found a single Air Force sentry on duty, unarmed. After ordering a mock bombing exercise on Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater Day ...

, LeMay was shocked to learn that most of the strategic bombers assigned to the mission missed their targets by one mile or more. "We didn't have one crew, not one crew, in the entire command who could do a professional job", noted LeMay.

A meeting in November 1948, with Air Force Chief of Staff Hoyt Vandenberg

Hoyt Sanford Vandenberg (January 24, 1899 – April 2, 1954) was a United States Air Force general. He served as the second Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and the second Director of Central Intelligence.

During World War II, Vandenberg was t ...

, found the two men agreeing the primary mission of SAC should be the capability of delivering 80% of the nation's atomic bombs in one mission. At the Dualism Conference in December 1948, the Air Force high command rallied behind LeMay's position that the service's highest priority was to deliver the SAC atomic offensive "in one fell swoop telescoping mass and time". "To LeMay, demolishing everything was how you win a war." Towards this aim, LeMay delivered the first SAC Emergency War Plan in March 1949 which called for dropping 133 atomic bombs on 70 cities in the USSR within 30 days. LeMay predicted that World War III

World War III or the Third World War, often abbreviated as WWIII or WW3, are names given to a hypothetical World war, worldwide large-scale military conflict subsequent to World War I and World War II. The term has been in use ...

would last no longer than 30 days. Air power strategists called this type of pre-emptive strike "killing a nation".[Rhodes, 1995] However, the Harmon committee released their unanimous report two months later stating such an attack would not end a war with the Soviets and their industry would quickly recover. This committee had been specifically created by the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

to study the effects of a massive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, within weeks, an ad hoc Joint Chiefs committee recommended tripling America's nuclear arsenal, and Chief of Staff Vandenberg called for enough bombs to attack 220 targets, up from the previous 70.

Upon receiving his fourth star in 1951 at age 44, LeMay became the youngest American four-star general since Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. He would also become the longest serving person in that rank in American military history.MiG-17

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 (russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-17; NATO reporting name: Fresco) is a high-subsonic fighter aircraft produced in the Soviet Union from 1952 and was operated by air forces internationally. The MiG-17 w ...

while on a reconnaissance mission over the Soviet Union, "Well, maybe if we do this overflight right, we can get World War III started". Hal Austin assumed that LeMay was joking, but years later, after LeMay retired, Austin saw him again and "brought up the subject of the mission we had flown. And he remembered it like it was yesterday. We chatted about it a little bit. His comment again was, 'Well, we'd have been a hell of a lot better off if we'd got World War III started in those days.'"

In 1956 and 1957 LeMay implemented tests of 24-hour bomber and tanker alerts, keeping some bomber forces ready at all times. LeMay headed SAC until 1957, overseeing its transformation into a modern, efficient, all-jet force. LeMay's tenure was the longest over an American military command in nearly 100 years.

The "Airpower Battle"

USAF airpower development and LeMay's style

LeMay was instrumental in SAC's acquisition of a large fleet of new strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unlike tactical bombers, ...

s, establishment of a vast aerial refueling

Aerial refueling, also referred to as air refueling, in-flight refueling (IFR), air-to-air refueling (AAR), and tanking, is the process of transferring aviation fuel from one aircraft (the tanker) to another (the receiver) while both aircraft a ...

system, the formation of many new units and bases, development of a strategic ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within the ...

force, and establishment of a strict command and control

Command and control (abbr. C2) is a "set of organizational and technical attributes and processes ... hatemploys human, physical, and information resources to solve problems and accomplish missions" to achieve the goals of an organization or en ...

system with an unprecedented readiness capability. All of this was protected by a greatly enhanced and modernized security force, the Strategic Air Command Elite Guard

The SAC Elite Guard was a United States Air Force Security Police unit established in December 1956 to provide security at the headquarters of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) of the U.S. Air Force, as well as personal protection for the Commander ...

. LeMay insisted on rigorous training and very high standards of performance for all SAC personnel, be they officers, enlisted men, aircrews, mechanics, or administrative staff, and reportedly commented, "I have neither the time nor the inclination to differentiate between the incompetent and the merely unfortunate".

A famous legend

A legend is a Folklore genre, genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human valu ...

often used by SAC flight crews to illustrate LeMay's command style concerned his famous ever-present cigar. In the first known published account of the story, ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine reporter Ernest Havemann related that LeMay once took the co-pilot's seat of a SAC bomber to observe the mission, complete with lit cigar.[Havemann, p. 136] When asked by the pilot to put the cigar out, LeMay demanded to know why. When the pilot explained that fumes inside the fuselage could ignite the airplane, LeMay reportedly growled, "It wouldn't dare".Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

''. In his highly controversial and factually disputed memoir ''War's End'', Major General Charles Sweeney

Charles William Sweeney (December 27, 1919 – July 16, 2004) was an officer in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II and the pilot who flew '' Bockscar'' carrying the Fat Man atomic bomb to the Japanese city of Nagasaki on Augu ...

related an alleged 1944 incident that may have been the basis for the "It wouldn't dare" comment.

Despite his uncompromising attitude regarding performance of duty, LeMay was also known for his concern for the physical well-being and comfort of his men. LeMay found ways to encourage morale, individual performance, and the reenlistment rate through a number of means: encouraging off-duty group recreational activities, instituting spot promotions based on performance, and authorizing special uniforms, training, equipment, and allowances for ground personnel as well as flight crews.

On LeMay's departure, SAC was composed of 224,000 airmen, close to 2,000 heavy bombers, and nearly 800 tanker aircraft.

LeMay was appointed Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force in July 1957, serving until 1961.

Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, 1961–1965

Following service as USAF Vice Chief of Staff (1957–1961), LeMay was made the fifth

Following service as USAF Vice Chief of Staff (1957–1961), LeMay was made the fifth Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force

The chief of staff of the Air Force (acronym: CSAF, or AF/CC) is a statutory office () held by a general in the United States Air Force, and as such is the principal military advisor to the secretary of the Air Force on matter pertaining to th ...

on the retirement of Gen Thomas White. His belief in the efficacy of strategic air campaigns over tactical strikes and ground support operations became Air Force policy during his tenure as chief of staff.

As Chief of Staff, LeMay clashed repeatedly with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Air Force Secretary Eugene Zuckert

Eugene Martin Zuckert (November 9, 1911 – June 5, 2000) was the seventh United States Secretary of the Air Force from January 23, 1961 to September 30, 1965. During his service as secretary, he witnessed the shifting of decision-making powers fro ...

, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Army General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Maxwell Taylor

Maxwell Davenport Taylor (August 26, 1901 – April 19, 1987) was a senior United States Army officer and diplomat of the mid-20th century. He served with distinction in World War II, most notably as commander of the 101st Airborne Division, ni ...

. At the time, budget constraints and successive nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear w ...

fighting strategies had left the armed forces in a state of flux. Each of the armed forces had gradually jettisoned realistic appraisals of future conflicts in favor of developing its own separate nuclear and nonnuclear capabilities. At the height of this struggle, the U.S. Army had even reorganized its combat divisions to fight land wars on irradiated nuclear battlefields, developing short-range atomic cannon and mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a village i ...

in order to win appropriations. The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

in turn proposed delivering strategic nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s from supercarrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a n ...

s intended to sail into range of the Soviet air defense forces. Of all these various schemes, only LeMay's command structure of SAC survived complete reorganization in the changing reality of Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

-era conflicts.

LeMay was not an enthusiast of the ICBM program, considering ballistic missiles to be little more than toys and no substitute for the strategic nuclear bomber force.

Though LeMay lost significant appropriation battles for the Skybolt ALBM and the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress replacement, the North American XB-70 Valkyrie, he was largely successful at expanding Air Force budgets. Despite LeMay's disdain for missiles, he did strongly support the use of military space programs to perform satellite reconnaissance and gather electronic intelligence. For comparison, the US Army and Navy frequently suffered budgetary cutbacks and program cancellations by Congress and Secretary McNamara.

Cuban Missile Crisis

During the

During the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

in 1962, LeMay clashed again with U.S. President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

and Defense Secretary McNamara, arguing that he should be allowed to bomb nuclear missile sites in Cuba. He opposed the naval blockade and, after the end of the crisis, suggested that Cuba be invaded anyway, even after the Soviets agreed to withdraw their missiles. Kennedy refused LeMay's requests, and the naval blockade was successful.[

]

Strategic philosophy

The memorandum from LeMay, Chief of Staff, USAF, to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, January 4, 1964, illustrates LeMay's reasons for keeping bomber forces alongside ballistic missiles: "It is important to recognize, however, that ballistic missile forces represent both the U.S. and Soviet potential for strategic nuclear warfare at the highest, most indiscriminate level, and at a level least susceptible to control. The employment of these weapons in lower level conflict would be likely to escalate the situation, uncontrollably, to an intensity which could be vastly disproportionate to the original aggravation. The use of ICBMs and SLBMs is not, therefore, a rational or credible response to provocations which, although serious, are still less than an immediate threat to national survival. For this reason, among others, I consider that the national security will continue to require the flexibility, responsiveness, and discrimination of manned strategic weapon systems throughout the range of cold, limited, and general war".

Vietnam War

LeMay's dislike for tactical aircraft and training backfired in the low-intensity conflict of Vietnam War, Vietnam, where existing Air Force fighter aircraft and standard attack profiles proved incapable of carrying out sustained tactical bombing campaigns in the face of hostile North Vietnamese antiaircraft defenses. LeMay said, "Flying fighters is fun. Flying bombers is important". Aircraft losses on tactical attack missions soared, and Air Force commanders soon realized that their large, missile-armed jet fighters were exceedingly vulnerable not only to antiaircraft shells and missiles but also to cannon-armed, maneuverable Soviet fighters.

LeMay advocated a sustained strategic bombing campaign against North Vietnamese cities, harbors, ports, shipping, and other strategic targets. His advice was ignored. Instead, an incremental policy was implemented that focused on limited interdiction bombing of fluid enemy supply corridors in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. This limited campaign failed to destroy significant quantities of enemy war supplies or diminish enemy ambitions. Bombing limitations were imposed by President Lyndon Johnson for geopolitical reasons, as he surmised that bombing Soviet and Chinese ships in port and killing Soviet advisers would bring the Soviets and Chinese more directly into the war.

In his 1965 autobiography (co-written with MacKinlay Kantor), LeMay is quoted as saying his response to North Vietnam would be to demand that "they've got to draw in their horns and stop their aggression, or we're going to bomb them back into the Stone Age. And we would shove them back into the Stone Age with Air power or Naval power—not with ground forces".[LeMay, Gen. Curtis Emerson, with MacKinley Kantor, ''Mission With LeMay: My Story'', (Doubleday, 1965) p.565, as quoted (quote #127) in ''Respectfully Quoted A Dictionary of Quotations'' by James H. Billington, Library of Congress, as reproduced online b]

Google Books (click here for quote)

and as reproduced online b

LeMay subsequently rejected misquotes of the famous "Stone Age" quote.[Cullather, Nick (professor of history, Indiana University)]

"Bomb them Back to the Stone Age: An Etymology"

''History News Network'', October 6, 2006 Later, in a ''Washington Post'' interview LeMay said that "I never said we should bomb them back to the Stone Age. I said we had the capability to do it. I want to save lives on both sides".[LeMay, Gen. Curtis Emerson, in ''Washington Post'' interview published October 4, 1968, as quoted (quote #127) in ''Respectfully Quoted A Dictionary of Quotations'' by James H. Billington, Library of Congress, as reproduced online b]

Google Books (click here for quote)

and as reproduced online b

Etymologyst Barry Popik cites multiple sources (including interviews with LeMay) for various versions of both quotes from LeMay.[Popik, Barry (etymologist; contributor, ''Oxford English Dictionary'')]

"'Bomb into the Stone Age' (total destruction)"

''The Big Apple'' blog. Nevertheless, the "should" quote remained part of the LeMay legend, and remains widely attributed to him ever after.[Turner, Robert F.]

Chapter 10: "How Political Warfare Caused America to Snatch Defeat from the Jaws of Victory in Vietnam"

, from John Norton Moore and Robert F. Turner, editors, ''The ''Real'' Lessons of the Vietnam War: Reflections Twenty-Five Years After the Fall of Saigon'', 2002, Carolina Academic Press, Durham, N.Car.

Some military historians have argued that LeMay's theories were eventually proven correct. Near the war's end in December 1972, President Richard Nixon ordered Operation Linebacker II, a high-intensity Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps aerial bombing campaign, which included hundreds of B-52 bombers that struck previously untouched North Vietnamese strategic targets, including heavy populated areas in Hanoi and Haiphong. Linebacker II was followed by renewed negotiations that led to the Paris Peace Accords, Paris Peace Agreement, appearing to support the claim. However, consideration must be given to significant differences in terms of both military objectives and geopolitical realities between 1968 and 1972, including the impact of Nixon's recognition and exploitation of the Sino-Soviet split to gain a "free hand" in Vietnam and the shift of Communist opposition from an organic insurgency (the Viet Cong) to a conventional mechanized offensive that was by its nature more reliant on industrial output and traditional logistics. In effect, Johnson and Nixon were waging two different wars.

Post-military career

Early political life and developments

Because of his unrelenting opposition to the Johnson administration's Vietnam policy and what was widely perceived as his hostility to Robert McNamara, LeMay was essentially forced into retirement in February 1965. Moving to California, he was approached by conservatives to challenge moderate Republican Party (United States), Republican Thomas Kuchel for his seat in the United States Senate in 1968, but he declined.

Because of his unrelenting opposition to the Johnson administration's Vietnam policy and what was widely perceived as his hostility to Robert McNamara, LeMay was essentially forced into retirement in February 1965. Moving to California, he was approached by conservatives to challenge moderate Republican Party (United States), Republican Thomas Kuchel for his seat in the United States Senate in 1968, but he declined.

Vice presidential candidacy, 1968

For the 1968 United States presidential election, 1968 presidential election, LeMay originally supported former Republican Vice President Richard Nixon; he turned down two requests by former Alabama Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and ...

to join his newly formed American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in ...

, that year, on the grounds that a third-party candidacy might hurt Nixon's chances at the polls. (By coincidence, Wallace had served as a Sergeant (United States), sergeant in a unit commanded by LeMay during World War II before LeMay had Wallace transferred to the 477th Bombardment Group.)

In 1968 LeMay threw his support to Wallace and became his vice-presidential running mate on the American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in ...

ticket. The campaign saw Wallace's record on racial segregation heavily scrutinized.

Honors

LeMay was honored by several countries for his military service. His U.S. military decorations included the Distinguished Service Cross (United States), Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army), Distinguished Service Medal with two oak leaf clusters, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States), Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters, and the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters. He was also a recipient of the French Légion d'honneur and on December 7, 1964 the Japanese government conferred on him the First Order of Merit with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun. He was elected to the Alfalfa Club in 1957 and served as a general officer for 21 years.

In 1977, LeMay was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.

Personal life

On June 9, 1934, LeMay married Helen Estelle Maitland (died 1992), with whom he had one child, Patricia Jane LeMay Lodge, known as Janie.

Death

LeMay resided in Newport Beach, California

Newport Beach is a coastal city in South Orange County, California. Newport Beach is known for swimming and sandy beaches. Newport Harbor once supported maritime industries however today, it is used mostly for recreation. Balboa Island, Newport ...

starting in 1969. In 1989, he moved to Air Force Village West, a retirement community for former Air Force officers near March Air Force Base in Riverside, California, Riverside. He died on October 1, 1990, of complications from a heart attack in the 22nd Strategic Hospital on the grounds of March AFB.[ He is buried in the United States Air Force Academy Cemetery at Colorado Springs, Colorado, Colorado Springs, Colorado.

]

Miscellaneous

Amateur radio operator

LeMay was a Heathkit customerCalifornia

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. K0GRL is still the call sign of the Strategic Air Command Memorial Amateur Radio Club. He was famous for being on the air on amateur bands while flying on board SAC bombers. LeMay became aware that the new single sideband single-sideband modulation, (SSB) technology offered a big advantage over amplitude modulation Amplitude Modulation, (AM) for SAC aircraft operating long distances from their bases. In conjunction with Heath engineers and Arthur A. Collins, Art Collins (W0CXX) of Collins Radio, he established SSB as the radio standard for SAC bombers in 1957.

LeMay and sports car racing

LeMay was also a sports car owner and enthusiast (he owned an Allard Motor Company, Allard J2); as the "SAC era" began to wind down, LeMay loaned out facilities of SAC bases for use by the Sports Car Club of America,[ as the era of early street racing, street races began to die out. He was awarded the Woolf Barnato Award, SCCA's highest award, for contributions to the Club, in 1954.][ In November 2006, it was announced that LeMay would be one of the inductees into the SCCA Hall of Fame in 2007.]

Air Force Academy exemplar

On March 13, 2010, LeMay was named the USAFA Class exemplar, class exemplar for the United States Air Force Academy class of 2013.

Executive Jet Aviation pioneer

In 1964, LeMay became one of the founding board members of Executive Jet Aviation (EJA) (now called NetJets), along with fellow USAF generals Paul Tibbets and Olbert Lassiter, Washington lawyer and former military pilot Bruce Sundlun, and entertainers James Stewart and Arthur Godfrey.

It was the first private business jet charter and aircraft management company in the world.

Judo

Judo's resurgence after the war was due primarily to two individuals, Kyuzo Mifune and Curtis LeMay. The pre-war death of Kanō Jigorō, Jigorō Kanō ("the father of judo"), wartime demands on the Japanese, their surrender, postwar occupation, and the martial-arts ban all contributed to a time of uncertainty for judo. As assistant to General Douglas MacArthur during the occupation of Japan, LeMay made practicing judo a routine part of Air Force tours of duty in Japan. Many Americans brought home stories of a "tiny old man" (Mifune) throwing down healthy, young men without any apparent effort. LeMay became a promoter of judo training and provided political support for judo in the early years after the war. For this, he was awarded the license of ''Shihan''. In addition, LeMay promoted judo within the armed forces of the United States.

Rank history

;Training and cadet ranks

LeMay held the following ranks over the course of his Air Force career. LeMay's first contact with military service occurred in September 1924 when he enrolled as a student in the Army ROTC program at Ohio State University. By his senior year, LeMay was listed on the ROTC rolls as a "cadet lieutenant colonel". On June 14, 1928, the summer before the start of his senior year, LeMay accepted a commission as a second lieutenant in the Field Artillery Reserve of the U.S. Army. In September 1928, LeMay was approached by the Ohio National Guard and asked to accept a state commission, also as a second lieutenant, which LeMay accepted.

On September 29, 1928, LeMay enlisted in the Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet. For the next 13 months, he was on the enlisted rolls of the Regular Army (United States), Regular Army as a cadet and he held commissions in the National Guard and Army Reserve. His status changed on October 2, 1929, when LeMay's Guard and Reserve commissions were terminated. These commissions were revoked after an Army personnel officer, realizing that LeMay was holding officer and enlisted status simultaneously, called him to discuss the matter and LeMay verbally resigned these commissioned ranks over the telephone.

All officer commissions were terminated on October 2, 1929, pending completion of flight training and commissioning as an officer in the Army Air Corps.

;Commissioned ranks

On October 12, 1929, LeMay finished his flight training and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Air Corps Reserve. This was the third time he had been appointed a second lieutenant in just under two years. He held this reserve commission until June 1930, when he was appointed as a Regular Army officer in the Army Air Corps.

LeMay experienced slow advancement throughout the 1930s, as did most officers of the seniority-driven Regular Army. At the start of 1940 he was promoted to captain after serving nearly eleven years in the lieutenant grades. Beginning in 1941, LeMay began to receive temporary advancements in grade in the expanding Army Air Forces and advanced from captain to brigadier general in less than four years; by 1944, he was a major general in the Army Air Forces. When World War II ended, he was appointed to the permanent rank of brigadier general in the Regular Army and then promoted to permanent major general rank (two star) when the Air Force became its own separate branch of service. LeMay was simultaneously appointed to temporary three star general rank in the Air Force and promoted to the full rank of general, permanent in the Air Force, in 1951. LeMay held this rank until his retirement in 1965.

Curtis LeMay retired from the United States Air Force on February 1, 1965 with the rank of full (four star) general.

Further promotions

According to letters in LeMay's service record, while he was in command of SAC during the 1950s several petitions were made by Air Force service members to have LeMay promoted to the rank of General of the Air Force (United States), General of the Air Force (five stars). The Air Force leadership, however, felt that such a promotion would lessen the prestige of this rank, which was seen as a wartime rank to be held only in times of extreme national emergency.

Per the Chief of the Air Force General Officers Branch, in a letter dated February 28, 1962:

It is clear that a grateful nation, recognizing the tremendous contributions of the key military and naval leaders in World War II, created these supreme grades as an attempt to accord to these leaders the prestige, the clear-cut leadership, and the emolument of office befitting their service to their country in war. It is the conviction of the Department of the Air Force that this recognition was and is appropriate. Moreover, appointments to this grade during periods other than war would carry the unavoidable connotation of downgrading of those officers so honored in World War II.

Thus, no serious effort was ever made to promote LeMay to the rank of General of the Air Force, and the matter was eventually dropped after his retirement from active service in 1965.

Awards and decorations

LeMay received recognition for his work from thirteen countries, receiving two badges and thirty-two different medals and List of military decorations, decorations.

;United States

*USAF aeronautical rating#Pilot ratings, Command pilot

*Distinguished Service Cross (United States), Distinguished Service Cross

*Army Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Service Medal plus 2 oak leaf clusters

*Silver Star

*Distinguished Flying Cross (United States), Distinguished Flying Cross plus 2 oak leaf clusters

*Air Medal plus 4 oak leaf clusters

*Presidential Unit Citation (United States), Presidential Unit Citation plus oak leaf cluster

*American Defense Service Medal

*American Campaign Medal

*European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal plus 3 bronze campaign stars

*Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal plus 4 bronze campaign stars

*World War II Victory Medal

*Army of Occupation Medal with Berlin Airlift Device

*Medal for Humane Action

*National Defense Service Medal with one service star

*Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

*Vietnam Service Medal

*Air Force Longevity Service Award, 8 oak leaf clusters

;Other countries

*Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom), United Kingdom Distinguished Flying Cross

*Soviet Union, U.S.S.R – Order of the Patriotic War – 1st Degree

*Legion of Honour, Legion of Honour (Commandeur) (France)

*Croix de guerre 1939-1945 (France), French Croix de Guerre with silver Palm

*Belgium, Belgian War Cross (Belgium), Croix de Guerre, with silver Palm

*Ecuador – Order of Aeronautical Merit (Knight Commander)

*Brazilian Order of Aeronautical Merit (Brazil), Order of Aeronautical Merit, Commander

*Morocco, Moroccan Order of Ouissam Alaouite, Commander

*Argentina – Order of May, Order of May of Aeronautical Merit – Grades of Grand Cross and Grand Commander

*Brazilian Order of the Southern Cross, Grand Cross

*

LeMay received recognition for his work from thirteen countries, receiving two badges and thirty-two different medals and List of military decorations, decorations.

;United States

*USAF aeronautical rating#Pilot ratings, Command pilot

*Distinguished Service Cross (United States), Distinguished Service Cross

*Army Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Service Medal plus 2 oak leaf clusters

*Silver Star

*Distinguished Flying Cross (United States), Distinguished Flying Cross plus 2 oak leaf clusters

*Air Medal plus 4 oak leaf clusters

*Presidential Unit Citation (United States), Presidential Unit Citation plus oak leaf cluster

*American Defense Service Medal

*American Campaign Medal

*European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal plus 3 bronze campaign stars

*Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal plus 4 bronze campaign stars

*World War II Victory Medal

*Army of Occupation Medal with Berlin Airlift Device

*Medal for Humane Action

*National Defense Service Medal with one service star

*Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

*Vietnam Service Medal

*Air Force Longevity Service Award, 8 oak leaf clusters

;Other countries

*Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom), United Kingdom Distinguished Flying Cross

*Soviet Union, U.S.S.R – Order of the Patriotic War – 1st Degree

*Legion of Honour, Legion of Honour (Commandeur) (France)

*Croix de guerre 1939-1945 (France), French Croix de Guerre with silver Palm

*Belgium, Belgian War Cross (Belgium), Croix de Guerre, with silver Palm

*Ecuador – Order of Aeronautical Merit (Knight Commander)

*Brazilian Order of Aeronautical Merit (Brazil), Order of Aeronautical Merit, Commander

*Morocco, Moroccan Order of Ouissam Alaouite, Commander

*Argentina – Order of May, Order of May of Aeronautical Merit – Grades of Grand Cross and Grand Commander

*Brazilian Order of the Southern Cross, Grand Cross

*Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

ese Order of the Rising Sun, Grand Cordon

*Sweden, Swedish Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword, Royal Order of the Sword

*Chile – Order of the Merit of Chile, Order of Merit ''(degree unknown)''

*Chile – Medalla Militar de Primera Clase

*Uruguay – Aviador Militar Honoris Causa (Piloto Comandante)

Works

Books

* .

* .

* .

Film and television appearances

*''The Last Bomb'' (documentary, 1945)

*''In the Year of the Pig'' (documentary, 1968)

*''The World at War'' (documentary TV series, 1974)

*''Reaching for the Skies'' (documentary TV series, 1988)

*''Race for the Superbomb'' (documentary, 1999)

*''JFK (film), JFK'' (film, 1991; featured in archival footage)

*''Roots of the Cuban Missile Crisis'' (documentary, 2001)

*''The Fog of War, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara'' (documentary, 2003)

*''DC3:ans Sista Resa'' (Swedish documentary, 2004)

Cultural legacy

According to Michael S. Sherry, "Few American military officers of this century have been more feared, reviled, and ridiculed than Curtis E. LeMay." According to Fred Kaplan (journalist), Fred Kaplan:''Dr. Strangelove'', Stanley Kubrick's 1964 film about nuclear-war plans run amok, is widely heralded as one of the greatest satires in American political or movie history. ... It was no secret—it would have been obvious to many viewers in 1964—that General Ripper looked a lot like Curtis LeMay, the cigar-chomping, gruff-talking general."

University of Notre Dame Professor Dan Lindley points out parallels between LeMay and the characters of Buck Turgidson and Jack Ripper in Stanley Kubrick's ''Dr. Strangelove'', including close paraphrasing of statements by LeMay.

Public buildings

* The headquarters building of United States Strategic Command, U.S. Strategic Command at Offutt Air Force Base, Offutt AFB in Nebraska is named for the general. It was erected in the late 1950s and was the headquarters of the

* The headquarters building of United States Strategic Command, U.S. Strategic Command at Offutt Air Force Base, Offutt AFB in Nebraska is named for the general. It was erected in the late 1950s and was the headquarters of the Strategic Air Command