In

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, a

real-valued function

In mathematics, a real-valued function is a function whose values are real numbers. In other words, it is a function that assigns a real number to each member of its domain.

Real-valued functions of a real variable (commonly called ''real ...

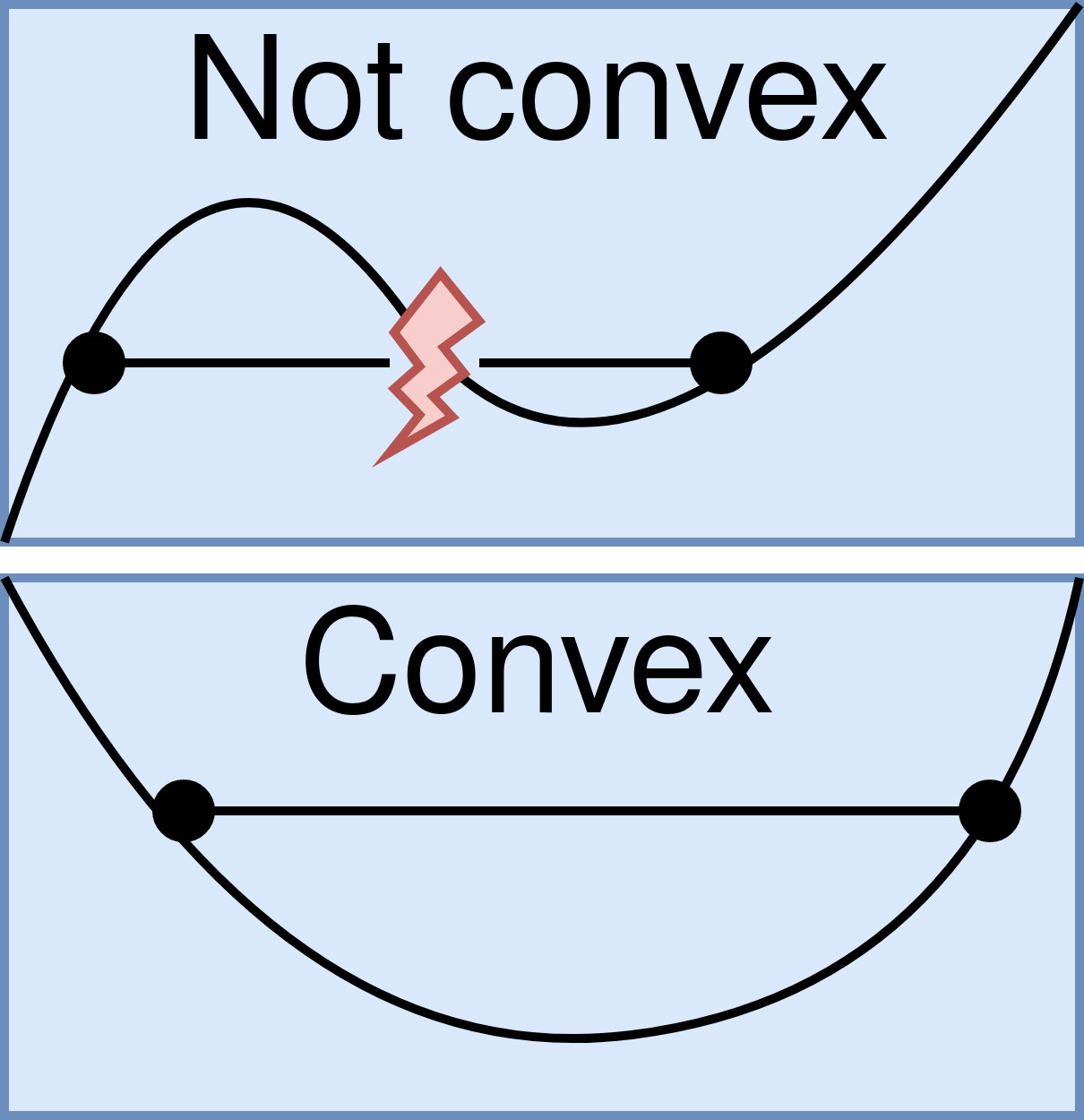

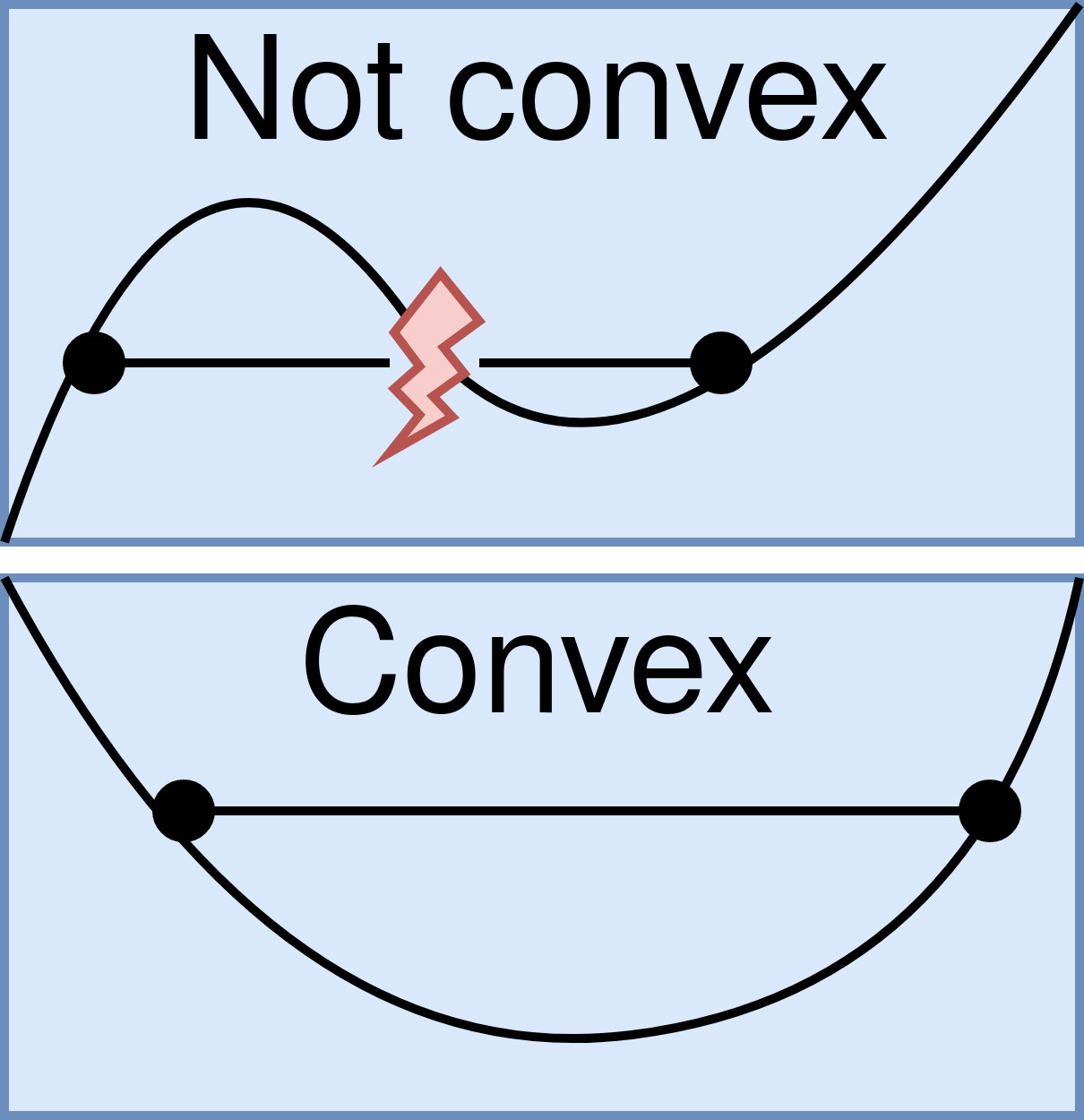

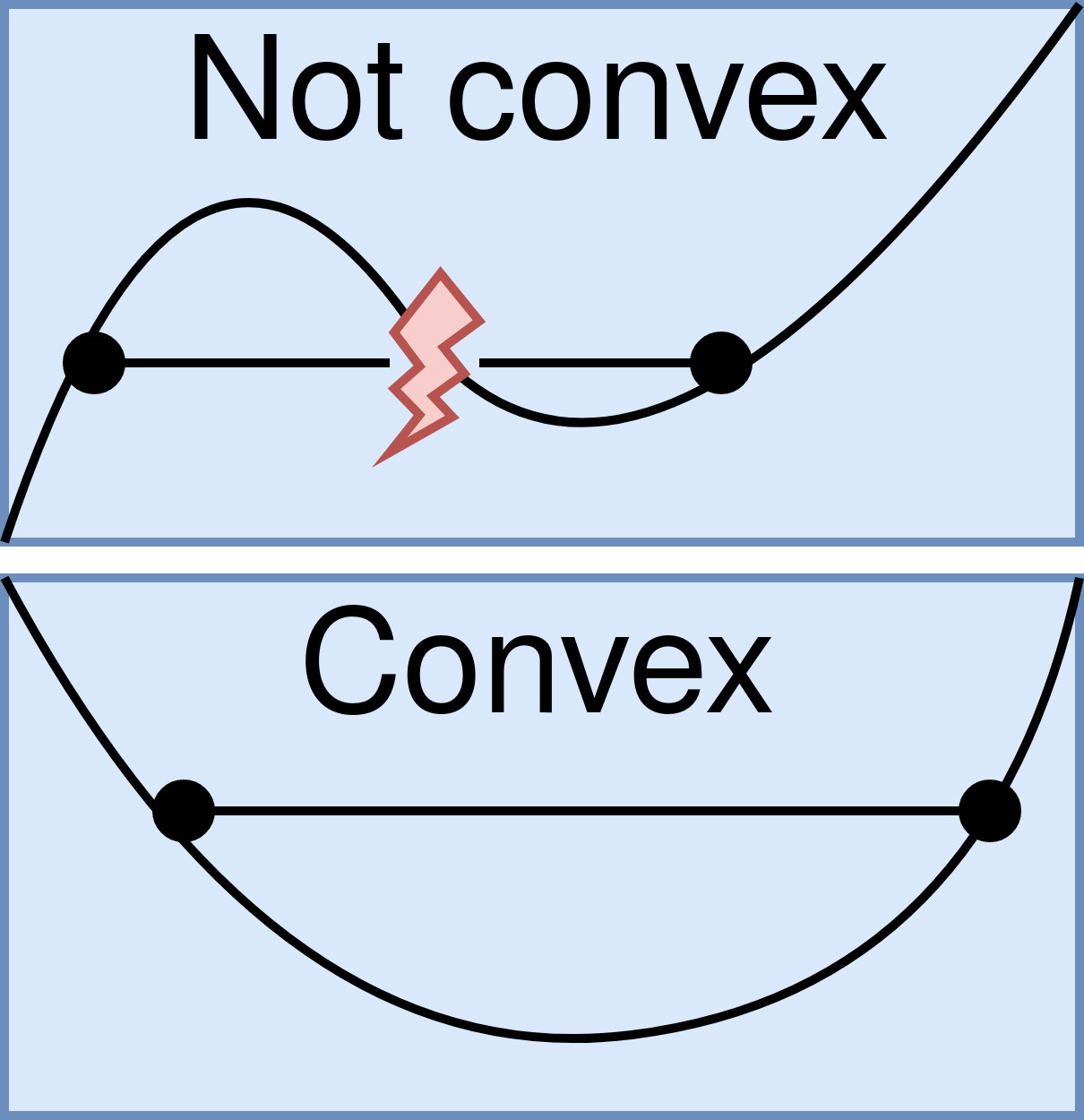

is called convex if the

line segment

In geometry, a line segment is a part of a line (mathematics), straight line that is bounded by two distinct endpoints (its extreme points), and contains every Point (geometry), point on the line that is between its endpoints. It is a special c ...

between any two distinct points on the

graph of the function lies above or on the graph between the two points. Equivalently, a function is convex if its

''epigraph'' (the set of points on or above the graph of the function) is a

convex set

In geometry, a set of points is convex if it contains every line segment between two points in the set.

For example, a solid cube (geometry), cube is a convex set, but anything that is hollow or has an indent, for example, a crescent shape, is n ...

.

In simple terms, a convex function graph is shaped like a cup

(or a straight line like a linear function), while a

concave function

In mathematics, a concave function is one for which the function value at any convex combination of elements in the domain is greater than or equal to that convex combination of those domain elements. Equivalently, a concave function is any funct ...

's graph is shaped like a cap

.

A twice-

differentiable

In mathematics, a differentiable function of one real variable is a function whose derivative exists at each point in its domain. In other words, the graph of a differentiable function has a non- vertical tangent line at each interior point in ...

function of a single variable is convex

if and only if

In logic and related fields such as mathematics and philosophy, "if and only if" (often shortened as "iff") is paraphrased by the biconditional, a logical connective between statements. The biconditional is true in two cases, where either bo ...

its

second derivative

In calculus, the second derivative, or the second-order derivative, of a function is the derivative of the derivative of . Informally, the second derivative can be phrased as "the rate of change of the rate of change"; for example, the secon ...

is nonnegative on its entire

domain. Well-known examples of convex functions of a single variable include a

linear function

In mathematics, the term linear function refers to two distinct but related notions:

* In calculus and related areas, a linear function is a function whose graph is a straight line, that is, a polynomial function of degree zero or one. For di ...

(where

is a

real number

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measure a continuous one- dimensional quantity such as a duration or temperature. Here, ''continuous'' means that pairs of values can have arbitrarily small differences. Every re ...

), a

quadratic function

In mathematics, a quadratic function of a single variable (mathematics), variable is a function (mathematics), function of the form

:f(x)=ax^2+bx+c,\quad a \ne 0,

where is its variable, and , , and are coefficients. The mathematical expression, e ...

(

as a nonnegative real number) and an

exponential function (

as a nonnegative real number).

Convex functions play an important role in many areas of mathematics. They are especially important in the study of

optimization

Mathematical optimization (alternatively spelled ''optimisation'') or mathematical programming is the selection of a best element, with regard to some criteria, from some set of available alternatives. It is generally divided into two subfiel ...

problems where they are distinguished by a number of convenient properties. For instance, a strictly convex function on an

open set

In mathematics, an open set is a generalization of an Interval (mathematics)#Definitions_and_terminology, open interval in the real line.

In a metric space (a Set (mathematics), set with a metric (mathematics), distance defined between every two ...

has no more than one

minimum

In mathematical analysis, the maximum and minimum of a function are, respectively, the greatest and least value taken by the function. Known generically as extremum, they may be defined either within a given range (the ''local'' or ''relative ...

. Even in infinite-dimensional spaces, under suitable additional hypotheses, convex functions continue to satisfy such properties and as a result, they are the most well-understood functionals in the

calculus of variations

The calculus of variations (or variational calculus) is a field of mathematical analysis that uses variations, which are small changes in Function (mathematics), functions

and functional (mathematics), functionals, to find maxima and minima of f ...

. In

probability theory

Probability theory or probability calculus is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expre ...

, a convex function applied to the

expected value

In probability theory, the expected value (also called expectation, expectancy, expectation operator, mathematical expectation, mean, expectation value, or first Moment (mathematics), moment) is a generalization of the weighted average. Informa ...

of a

random variable

A random variable (also called random quantity, aleatory variable, or stochastic variable) is a Mathematics, mathematical formalization of a quantity or object which depends on randomness, random events. The term 'random variable' in its mathema ...

is always bounded above by the expected value of the convex function of the random variable. This result, known as

Jensen's inequality

In mathematics, Jensen's inequality, named after the Danish mathematician Johan Jensen, relates the value of a convex function of an integral to the integral of the convex function. It was proved by Jensen in 1906, building on an earlier p ...

, can be used to deduce

inequalities such as the

arithmetic–geometric mean inequality and

Hölder's inequality

In mathematical analysis, Hölder's inequality, named after Otto Hölder, is a fundamental inequality (mathematics), inequality between Lebesgue integration, integrals and an indispensable tool for the study of Lp space, spaces.

The numbers an ...

.

Definition

Let

be a

convex subset

In geometry, a set of points is convex if it contains every line segment between two points in the set.

For example, a solid cube (geometry), cube is a convex set, but anything that is hollow or has an indent, for example, a crescent shape, is n ...

of a real

vector space

In mathematics and physics, a vector space (also called a linear space) is a set (mathematics), set whose elements, often called vector (mathematics and physics), ''vectors'', can be added together and multiplied ("scaled") by numbers called sc ...

and let

be a function.

Then

is called if and only if any of the following equivalent conditions hold:

- For all and all :

The right hand side represents the straight line between and in the graph of as a function of increasing from to or decreasing from to sweeps this line. Similarly, the argument of the function in the left hand side represents the straight line between and in or the -axis of the graph of So, this condition requires that the straight line between any pair of points on the curve of be above or just meeting the graph.

- For all and all such that :

The difference of this second condition with respect to the first condition above is that this condition does not include the intersection points (for example, and ) between the straight line passing through a pair of points on the curve of (the straight line is represented by the right hand side of this condition) and the curve of the first condition includes the intersection points as it becomes or at or or In fact, the intersection points do not need to be considered in a condition of convex using because and are always true (so not useful to be a part of a condition).

The second statement characterizing convex functions that are valued in the real line

is also the statement used to define that are valued in the

extended real number line

In mathematics, the extended real number system is obtained from the real number system \R by adding two elements denoted +\infty and -\infty that are respectively greater and lower than every real number. This allows for treating the potential ...

where such a function

is allowed to take

as a value. The first statement is not used because it permits

to take

or

as a value, in which case, if

or

respectively, then

would be undefined (because the multiplications

and

are undefined). The sum

is also undefined so a convex extended real-valued function is typically only allowed to take exactly one of

and

as a value.

The second statement can also be modified to get the definition of , where the latter is obtained by replacing

with the strict inequality

Explicitly, the map

is called if and only if for all real

and all

such that

:

A strictly convex function

is a function that the straight line between any pair of points on the curve

is above the curve

except for the intersection points between the straight line and the curve. An example of a function which is convex but not strictly convex is

. This function is not strictly convex because any two points sharing an x coordinate will have a straight line between them, while any two points NOT sharing an x coordinate will have a greater value of the function than the points between them.

The function

is said to be (resp. ) if

(

multiplied by −1) is convex (resp. strictly convex).

Alternative naming

The term ''convex'' is often referred to as ''convex down'' or ''concave upward'', and the term

concave

Concave or concavity may refer to:

Science and technology

* Concave lens

* Concave mirror

Mathematics

* Concave function, the negative of a convex function

* Concave polygon

A simple polygon that is not convex is called concave, non-convex or ...

is often referred as ''concave down'' or ''convex upward''. If the term "convex" is used without an "up" or "down" keyword, then it refers strictly to a cup shaped graph

. As an example,

Jensen's inequality

In mathematics, Jensen's inequality, named after the Danish mathematician Johan Jensen, relates the value of a convex function of an integral to the integral of the convex function. It was proved by Jensen in 1906, building on an earlier p ...

refers to an inequality involving a convex or convex-(down), function.

Properties

Many properties of convex functions have the same simple formulation for functions of many variables as for functions of one variable. See below the properties for the case of many variables, as some of them are not listed for functions of one variable.

Functions of one variable

* Suppose

is a function of one

real variable defined on an interval, and let

(note that

is the slope of the purple line in the first drawing; the function

is

symmetric

Symmetry () in everyday life refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, the term has a more precise definition and is usually used to refer to an object that is invariant under some transformations ...

in

means that

does not change by exchanging

and

).

is convex if and only if

is

monotonically non-decreasing in

for every fixed

(or vice versa). This characterization of convexity is quite useful to prove the following results.

* A convex function

of one real variable defined on some

open interval

In mathematics, a real interval is the set (mathematics), set of all real numbers lying between two fixed endpoints with no "gaps". Each endpoint is either a real number or positive or negative infinity, indicating the interval extends without ...

is

continuous

Continuity or continuous may refer to:

Mathematics

* Continuity (mathematics), the opposing concept to discreteness; common examples include

** Continuous probability distribution or random variable in probability and statistics

** Continuous ...

on

. Moreover,

admits

left and right derivatives, and these are

monotonically non-decreasing. In addition, the left derivative is left-continuous and the right-derivative is right-continuous. As a consequence,

is

differentiable

In mathematics, a differentiable function of one real variable is a function whose derivative exists at each point in its domain. In other words, the graph of a differentiable function has a non- vertical tangent line at each interior point in ...

at all but at most

countably many points, the set on which

is not differentiable can however still be dense. If

is closed, then

may fail to be continuous at the endpoints of

(an example is shown in the

examples section).

* A

differentiable

In mathematics, a differentiable function of one real variable is a function whose derivative exists at each point in its domain. In other words, the graph of a differentiable function has a non- vertical tangent line at each interior point in ...

function of one variable is convex on an interval if and only if its

derivative

In mathematics, the derivative is a fundamental tool that quantifies the sensitivity to change of a function's output with respect to its input. The derivative of a function of a single variable at a chosen input value, when it exists, is t ...

is

monotonically non-decreasing on that interval. If a function is differentiable and convex then it is also

continuously differentiable

In mathematics, a differentiable function of one Real number, real variable is a Function (mathematics), function whose derivative exists at each point in its Domain of a function, domain. In other words, the Graph of a function, graph of a differ ...

.

* A differentiable function of one variable is convex on an interval if and only if its graph lies above all of its

tangent

In geometry, the tangent line (or simply tangent) to a plane curve at a given point is, intuitively, the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. Leibniz defined it as the line through a pair of infinitely close points o ...

s:

for all

and

in the interval.

* A twice differentiable function of one variable is convex on an interval if and only if its

second derivative

In calculus, the second derivative, or the second-order derivative, of a function is the derivative of the derivative of . Informally, the second derivative can be phrased as "the rate of change of the rate of change"; for example, the secon ...

is non-negative there; this gives a practical test for convexity. Visually, a twice differentiable convex function "curves up", without any bends the other way (

inflection point

In differential calculus and differential geometry, an inflection point, point of inflection, flex, or inflection (rarely inflexion) is a point on a smooth plane curve at which the curvature changes sign. In particular, in the case of the graph ...

s). If its second derivative is positive at all points then the function is strictly convex, but the

converse does not hold. For example, the second derivative of

is

, which is zero for

but

is strictly convex.

**This property and the above property in terms of "...its derivative is monotonically non-decreasing..." are not equal since if

is non-negative on an interval

then

is monotonically non-decreasing on

while its converse is not true, for example,

is monotonically non-decreasing on

while its derivative

is not defined at some points on

.

* If

is a convex function of one real variable, and

, then

is

superadditive

In mathematics, a function f is superadditive if

f(x+y) \geq f(x) + f(y)

for all x and y in the domain of f.

Similarly, a sequence a_1, a_2, \ldots is called superadditive if it satisfies the inequality

a_ \geq a_n + a_m

for all m and n.

The ...

on the

positive reals

Positive is a property of positivity and may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Positive formula, a logical formula not containing negation

* Positive number, a number that is greater than 0

* Plus sign, the sign "+" used to indicate a posit ...

, that is

for positive real numbers

and

.

* A function

is midpoint convex on an interval

if for all

This condition is only slightly weaker than convexity. For example, a real-valued

Lebesgue measurable function

In mathematics, and in particular measure theory, a measurable function is a function between the underlying sets of two measurable spaces that preserves the structure of the spaces: the preimage of any measurable set is measurable. This is in d ...

that is midpoint-convex is convex: this is a theorem of

Sierpiński. In particular, a continuous function that is midpoint convex will be convex.

Functions of several variables

* A function that is marginally convex in each individual variable is not necessarily (jointly) convex. For example, the function

is

marginally linear, and thus marginally convex, in each variable, but not (jointly) convex.

* A function

In

In  In

In